Abstract

OBJECTIVES

The purpose of this work was to report the intervention effects of Focus on Youth in the Caribbean (youth HIV intervention), an HIV prevention intervention based on protection motivation theory, through 24 months of follow-up on sexual risk and protection knowledge, perceptions, intentions, and behavior among Bahamian sixth-grade youth.

METHODS

We randomly assigned 1360 sixth-grade youth (and their parents) attending 15 government elementary schools in the Bahamas to 1 of 3 conditions: (1) youth HIV intervention plus a parental monitoring/communication/HIV education intervention; (2) youth HIV intervention plus a parental goal-setting intervention; or (3) an environmental protection intervention plus the parental goal-setting intervention. Baseline and 4 follow-up surveys at 6-month intervals were conducted. Intervention effects were assessed using the mixed model for continuous outcome variables and the generalized linear mixed model for dichotomous outcome variables.

RESULTS

Through 24 months of follow-up, youth HIV intervention, in combination with the parent interventions, significantly increased youths’ HIV/AIDS knowledge, perceptions of their ability to use condoms, perception of the effectiveness of condoms and abstinence, and condom use intention and significantly lowered perceived costs to remaining abstinent. There was a trend for higher condom use among youth in the Focus on Youth in the Caribbean groups at each follow-up interval.

CONCLUSIONS

Focus on Youth in the Caribbean, in combination with 1 of 2 parent interventions administered to preadolescents and their parents in the Bahamas, resulted in and sustained protective changes on HIV/AIDS knowledge, sexual perceptions, and condom use intention. Although rates of sexual experience remained low, the consistent trend at all of the follow-up periods for higher condom use among youth who received youth intervention reached marginal significance at 24 months. Additional follow-up is necessary to determine whether the apparent protective effect is statistically significant as more youth initiate sex and whether it endures over time.

Keywords: protection motivation theory, preadolescent, intervention, HIV/AIDS, condom use, sexual behavior

In the absence of effective vaccines or other biomedical interventions to prevent HIV infection, behavioral prevention remains the cornerstone of global efforts to control the HIV/AIDS epidemic.1 Approximately 40% of newly diagnosed HIV infections occur among persons aged 15 to 24 years,2–4 underscoring the importance of behavioral prevention interventions during early adolescence.

Central to HIV prevention efforts has been the use of theories of behavioral change to direct the design of the prevention program.5–7 Protection motivation theory (PMT), a social cognitive theory, has been used to guide intervention development regarding multiple health threats, including HIV/AIDS.8–14 PMT is based on 2 presumptive cognitive pathways: the threat-appraisal pathway and the coping-appraisal pathway. The threat-appraisal pathway includes 4 constructs and evaluates both the potential rewards from the maladaptive response (intrinsic and extrinsic rewards for engaging in maladaptive behaviors) and the perceived severity and vulnerability to the outcome of the maladaptive behavior. The coping-appraisal pathway (3 constructs) evaluates the individual’s perceptions of his or her ability to avert the threatened danger, including efficacy variables (the response efficacy of the maneuver and the individual’s self-efficacy to perform the maneuver) and the potential response cost (eg, disadvantages or untoward outcomes) of the protective maneuver. Balance between these 2 appraisal pathways determines the intention, or “protection motivation,” to initiate, continue, or inhibit an adaptive response. This intention may result in a protective action.15,16 Studies addressing HIV/AIDS prevention have generally found that PMT serves as a robust model for understanding and altering HIV-related health promotion and risk behaviors.17–22 In the 1990s, we developed and evaluated Focus on Kids (FOK), a prevention intervention based on PMT for children ages 9 through 15 years. Through a series of analyses, we found that the intervention did reduce sexual risk behavior for the short term (through 6 months of follow-up) but not through 12 months of follow-up.23 However, after a booster at 13 months postintervention, there was, again, a protective effect on sexual risk behavior at 18 months.24 Although we were encouraged by these short-term effects of the PMT-based intervention, we wished to identify an intervention approach of which the impact would be more enduring.

Existing research indicates that youth perceptions of parental monitoring and effective parent-child communication are inversely correlated with youth involvement in sexual risk and substance abuse behaviors.25–31 Accordingly, we developed and evaluated a parental monitoring, communication, and HIV education intervention, Informed Parents and Children Together (Im-PACT), to be given in combination with FOK. Through a randomized, controlled trial conducted among adolescents (all of whom received FOK) aged 13 to 16 years at baseline, we found that children whose parents received ImPACT exhibited more protective behaviors over 2 years than those whose parents received a career goal-setting intervention titled Goal for It (GFI). We concluded that a parental monitoring, communication, and HIV education intervention could enhance and sustain an effective prevention program based on PMT targeting midadolescents.24

Once again, however, this work had focused on adolescents rather than preadolescents. In many settings, the onset of sexual risk occurs during early adolescence,32–35 making it important to reach children with prevention messages during their preadolescent years. However, given that abstract thinking typically begins to develop in early adolescence and might be expected to be largely completed by midadolescence,36,37 an intervention based on a social cognitive model such as PMT would not necessarily be appropriate for children in their preadolescent years. That is, PMT requires the understanding of abstract concepts, such as long-term and indirect consequences of active and passive decisions made, perspective taking, individual responsibility, and concepts of probability. Consistent with this developmental perspective, although FOK had been developed for children as young as 9 years of age, the intervention seemed to be stronger among older youth23; and, in our subsequent work with FOK and ImPACT, the median age of the children was 14 years.24,38 Therefore, when researchers and child health specialists from the Bahamas approached us about adapting FOK and ImPACT for use among preadolescents (sixth-grade students), the US and Bahamian teams felt it important to subject the intervention to a longitudinal, randomized, controlled trial.

In a previous publication, we described the process and short-term outcomes of the adaptation of FOK for sixth-grade Bahamian students (mean age at baseline: 10.4 years) and the adaptation of ImPACT for the parents of these preadolescents.39 At 6 months postintervention, the youth intervention, Focus on Youth in the Caribbean (FOYC), had positively impacted knowledge and condom-use skills, as well as several PMT perceptions and intentions to engage in safer behaviors.18 However, risk behaviors overall were very low, and there were no significant differences in behaviors. Accordingly, in the current study, we examined the effects through 24 months of follow-up of the PMT-based youth HIV-prevention intervention in combination with 1 of 2 parent interventions compared with a control condition on HIV/AIDS knowledge and sexual perceptions, intentions, and behaviors.

METHODS

Study Site

The Bahamas has the second highest prevalence rate of HIV in the Caribbean, with an estimated 3.3% of Bahamian adults infected with HIV. AIDS has been the leading cause of death among young adults 15 to 44 years of age in the Bahamas, with heterosexual activity as the predominant mode of transmission. The island of New Providence houses ~65% of the population and 85% of the HIV disease burden of the Bahamas.40

Intervention Description

We have described the development of FOYC and Informed Parents and Children Together in the Caribbean (CImPACT) for use in the Bahamas in great detail previously in the report of 6-month intervention effects.39 Briefly, FOYC and CImPACT were adapted by the Bahamian Ministry of Health and our research team from the intervention programs FOK and ImPACT, which were selected as Best Evidence Programs and are included in the Diffusion of Behavioral Intervention portfolio of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (www.effectiveinterventions.org). These programs were developed for use among adolescents and their parents living in Baltimore, Maryland.38,41 FOYC, derived from FOK, consists of 10 sessions each ~75 minutes in length. FOYC is based on PMT and emphasizes healthy decision-making, goal setting, communication, negotiation, consensual relationships, and information regarding abstinence, safer sex, etc. CImPACT is a 1-hour parent intervention session consisting of a 24-minute video filmed in the Bahamas and focused on parent-preadolescent communication, parental monitoring, and HIV prevention. The video is followed by a condom demonstration and role play emphasizing several concepts of parental monitoring and communication. The alternative parent intervention, GFI, is also a 1-hour session, including a 20-minute video and follow-up discussion designed to provide parents with a framework and skills to develop and reach future educational and career goals. The youth control condition, the Wondrous Wetlands (WW), also consists of 10 sessions, each of which presents information in an interactive and hands-on fashion regarding the protection of the environment, including Bahamas’ wetlands.

A 1-hour booster session was given to youth (both FOYC and WW) after completion of the 12-month assessment. For FOYC youth, the booster focused on a review of HIV facts and application of a decision-making model introduced previously to the youth in the FOYC curriculum, whereas for WW youth, it focused on steps to preserve water, a Bahamian natural resource.

Participants

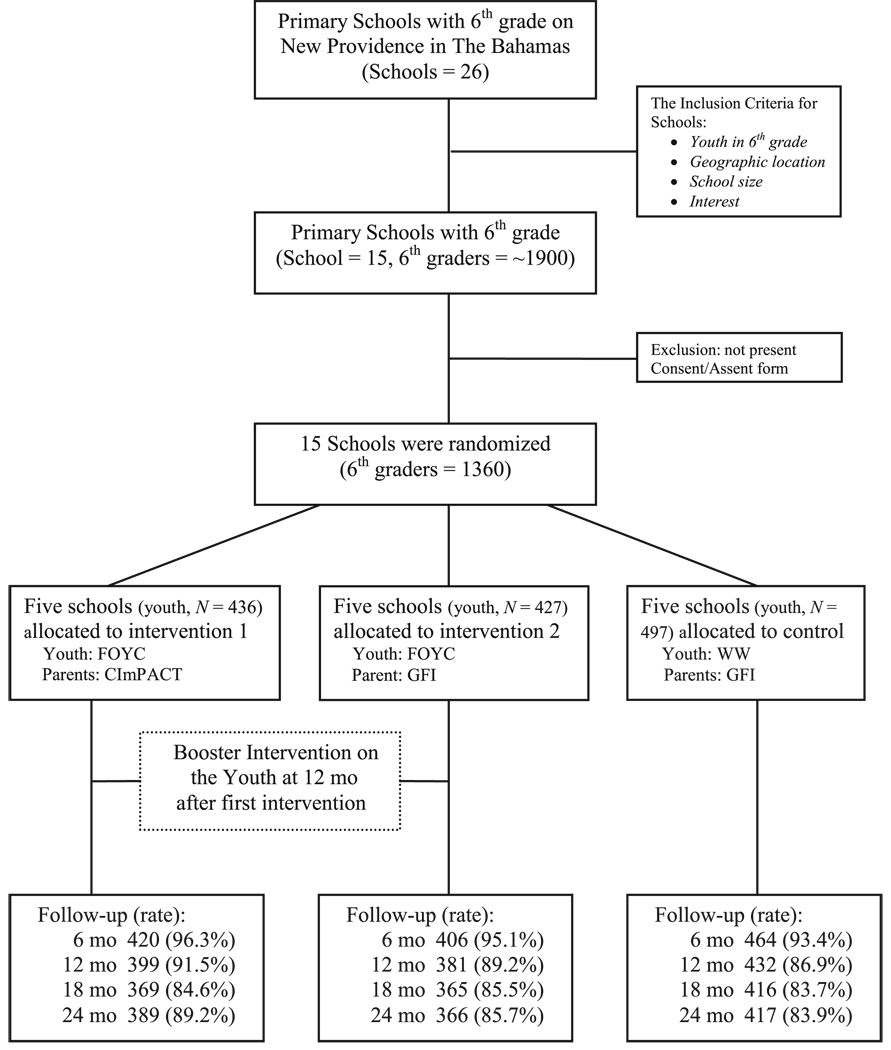

The participants in the study included 1360 sixth-grade students (and 1175 of their parents) who were recruited from 15 of the 26 government elementary schools from New Providence, the most populous island in the Bahamas. The 15 schools were randomly assigned such that 10 schools received FOYC and 5 schools the WW intervention. All of the children attending these schools received the assigned curriculum. In addition, 5 of the 10 FOYC schools were randomly assigned to the parent condition CImPACT and 5 to GFI; the 5 WW schools were all assigned to the parent condition GFI (see Fig 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart for group-randomized, controlled design.

The 15 schools in the study were distributed across the 4 quadrants of the island. Given that the island of New Providence is the most densely populated of the 700 islands, all of the schools serve a primarily urban population. Approximately two thirds of eligible youth from each of the 15 schools participated in the longitudinal evaluation of the intervention, resulting in 427 sixth-grade students from the 5 FOYC/GFI schools, 436 from the 5 FOYC/CImPACT schools, and 497 from the 5 control schools (WW/GFI). The data in the present analyses were obtained from 5 surveys of the youth (a baseline survey and 4 postintervention follow-up surveys with 6-month intervals between visits). The baseline survey was conducted among the 1360 students enrolled in the study, who were aged 10 to 14 years old (mean: 10.4 years; SD: 0.6 years). Of the youth participating in the baseline survey, 94.9% completed the follow-up at 6 months postintervention, 89.1% completed the follow-up at ~12 months postintervention, 84.6% completed the follow-up at ~18 months postintervention, and 86.2% completed the follow-up at ~24 months postintervention (see Fig 1). No significant baseline differences existed between the youth who were present and those who were not present at ≥1 follow-up with respect to intervention assignment, gender, age, PMT perceptions, intentions, or behaviors at the .05 α level, with one exception. “Intention to use a condom” was higher at baseline among the youth who were not present compared with those who were present at the 12-month and 18-month follow-ups (P = .02 and P = .03, respectively). Because our analytical models controlled baseline differences even if the baseline comparability between the intervention and the control was reduced because of this differential attrition, these differences did not impact our results. In addition, there were no significant baseline differences between youth who were present at all of the follow-ups and those who were missing at 6 and 24 months.

Data Collection Procedures

Data used for analysis were collected using the Bahamian Youth Health Risk Behavioral Inventory, adapted from the Youth Health Risk Behavioral Inventory through extensive ethnographic research and pilot testing.42 The paper-and-pencil questionnaires were administrated in the classroom setting by project staff. The questionnaire, which required ~45 minutes to be completed, was read out loud by project staff while the students marked their responses on the questionnaires. Because we have reported previously on the 6-month follow-up results for knowledge, perceptions, and intentions,43 these 6-month follow-up results are not presented here.

Students were informed that participation was voluntary, and their answers were confidential. Teachers were asked to leave the classrooms during the survey. Each student was given a voucher worth $5 Bahamian and each parent a food voucher worth $9 Bahamian at a local store after completing the survey. Parental consent and youth assent were obtained before participation in the trial. The research protocol and questionnaires were approved by the institutional review boards at Wayne State University and Princess Margaret Hospital in Nassau.

Measures

HIV/AIDS Knowledge

HIV/AIDS-related knowledge was assessed using 14 items from 2 subscales: transmission knowledge and prevention knowledge. Transmission knowledge included 6 true/false items assessing knowledge of HIV transmission through questions about touching, eating, or sharing needles with a person infected with HIV and whether HIV infection could occur the first time one engaged in sex, if the individual was only having sex with one person, and/or if a condom broke during sex. Prevention knowledge was measured by 8 true/false items assessing knowledge regarding protection from HIV infection by using a condom during sex, bathing after sex, abstinence, using plastic wrap, keeping in good physical shape, taking a shower after sex, eating a good diet, and getting plenty of sleep. The ratio of correct answers divided by the total number of possible correct responses for each subscale was used to generate the scores for HIV/AIDS transmission and prevention knowledge such that a higher score indicated greater knowledge. The means of the 2 ratios (ranging from 0 to 1) for transmission and prevention subscales were used as the measure of overall AIDS knowledge.

PMT-Related Constructs

PMT perceptions included 2 behavioral domains: abstinence/sexual initiation and condom use. Abstinence/sexual initiation perceptions and condom use perceptions were both assessed by 7 subscales corresponding with the 7 PMT constructs (self-efficacy, response-efficacy, etc, as described in the “Introduction”). The items constituting the abstinence/sexual initiation subscales and the condom use subscales were measured by 5-point Likert scales (see Table 1 for items and subscales). The Cronbach α ranged from .27 to .76 for the abstinence/sexual initiation subscales and .40 to .87 for the condom use subscales among the Bahamian cohort. According to PMT, higher mean values for the self-efficacy, response efficacy, severity, and vulnerability subscales and lower values for intrinsic rewards, extrinsic rewards, and response cost subscales constitute protective responses.

TABLE 1.

Items and Characteristics of PMT Constructs for Abstinence/Sexual Initiation and Condom Use at Baseline, by Intervention Assignment

| Items and Constructs | Intervention | Control: WW/GFI, Mean (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| FOYC/GFI, Mean (SD) |

FOYC/CImPACT, Mean (SD) |

||

| Abstinence/sexual initiation, PMT perception | |||

| Threat appraisal | |||

| Extrinsic reward (Cronbach α =.62) | 1.70 (0.75) | 1.78 (0.79)a | 1.64 (0.74) |

| 1. I want kids my age to think I am having sex. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 1.56 (0.96) | 1.66 (1.11) | 1.57 (1.00) |

| 2. I want kids my age to think I am a virgin. (1 =strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree) | 2.20 (1.44)b | 2.26 (1.44)a | 1.99 (1.32) |

| 3. How many of your close friends have sex? (5 = most, 3 = some, 1 = none) | 1.45 (1.00) | 1.55 (1.16) | 1.43 (1.07) |

| 4. How many of the boys you know have sex? (5 = most, 3 = some, 1 = none) | 1.71 (1.25) | 1.67 (1.22) | 1.65 (1.26) |

| 5. How many of the girls you know have sex? (5 = most, 3 = some, 1 = none) | 1.58 (1.12) | 1.70 (1.24)b | 1.52 (1.12) |

| Intrinsic reward (NA) | 1.61 (1.18) | 1.57 (1.09) | 1.47 (1.05) |

| 1. How do you feel about having sex. (1 = bad, 5 = good) | 1.61 (1.18) | 1.57 (1.09) | 1.47 (1.05) |

| Perceived severity (Cronbach α = .65) | 4.73 (0.60) | 4.62 (0.70) | 4.70 (0.62) |

| 1. How do you feel about getting an HIV infection? (5 = very bad, 1 = very good) | 4.80 (0.65) | 4.73 (0.75) | 4.79 (0.66) |

| 2. How do you feel about getting an STD? (5 = very bad, 1 = very good) | 4.78 (0.66) | 4.70 (0.80) | 4.78 (0.68) |

| 3. How do you feel about getting pregnant or getting a girl pregnant? (5 = very bad, 1 = very good) | 4.61 (0.95) | 4.46 (1.08) | 4.58 (0.96) |

| Vulnerability (Cronbach α = .75) | 1.59 (0.81) | 1.74 (0.91) | 1.67 (0.85) |

| 1. In the next 6 months I will become infected with HIV. (5 = very likely, 1 = very unlikely) | 1.50 (0.91)b | 1.69 (1.09) | 1.62 (0.98) |

| 2. In the next 6 months I will get an STD. (5 = very likely, 1 = very unlikely) | 1.57 (0.92) | 1.63 (1.03) | 1.62 (0.95) |

| 3. In the next 6 months I will get pregnant/get a girl pregnant. (5 = very likely, 1 = very unlikely) | 1.70 (1.07) | 1.89 (1.28) | 1.84 (1.08) |

| Coping Appraisal | |||

| Self-efficacy (Cronbach α = .50) | 3.76 (0.96)b | 3.55 (1.09) | 3.61 (1.03) |

| 1. Even if all my friends were having sex, I would not feel I had to. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 3.23 (1.57) | 2.99 (1.66) | 3.04 (1.65) |

| 2. I can say no to someone I’m going with if I didn’t want to have sex. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 4.06 (1.21) | 3.74 (1.50) | 3.91 (1.31) |

| 3. I could go with a person for a long time and not have sex with them. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 3.98 (1.25) | 3.91 (1.35) | 3.90 (1.35) |

| Response efficacy (Cronbach α = .47) | 4.08 (0.90) | 3.98 (1.04)b | 4.13 (0.88) |

| 1. Not having sex is the best way of protecting yourself from getting pregnant. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 4.11 (1.32) | 3.92 (1.52) | 4.10 (1.34) |

| 2. I want to wait until I’m married before I have sex. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 4.07 (1.32) | 4.17 (1.35) | 4.16 (1.29) |

| 3. A guy and a girl can go together and not have sex. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 4.06 (1.24) | 3.88 (1.42)a | 4.11 (1.24) |

| Response cost (Cronbach α = .27) | 2.48 (0.78) | 2.50 (0.95) | 2.45 (0.87) |

| 1. Kids my age respect a girl who is a virgin. (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree) | 2.61 (1.27) | 2.49 (1.31) | 2.49 (1.28) |

| 2. A guy and a girl can go together and not have sex. (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree) | 1.94 (1.24) | 2.12 (1.42)a | 1.89 (1.24) |

| 3. If a girl says she won’t have sex, a boy would say okay. (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree) | 2.92 (1.42) | 2.92 (1.53) | 2.94 (1.43) |

| Condom use, PMT perception | |||

| Threat appraisal | |||

| Extrinsic reward (NA) | 2.47 (1.49) | 2.71 (1.52) | 2.42 (1.61) |

| 1. Of the boys you know who have sex, how many of them use condoms? (5 = most, 3 = some, 1 = none) | 2.47 (1.49) | 2.71 (1.52) | 2.42 (1.61) |

| Intrinsic reward (NA) | 2.98 (0.93)a | 3.08 (1.04) | 3.17 (1.00) |

| 1. Condoms make sex feel better. (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree) | 2.98 (0.93)a | 3.08 (1.04) | 3.17 (1.00) |

| Perceived severity (Cronbach α = 0.65) | 4.73 (0.60) | 4.62 (0.70) | 4.70 (0.62) |

| 1. How do you feel about getting an HIV infection? (5 = very bad, 1 = very good) | 4.80 (0.65) | 4.73 (0.75) | 4.79 (0.66) |

| 2. How do you feel about getting an STD? (5 = very bad, 1 = very good) | 4.78 (0.66) | 4.70 (0.80) | 4.78 (0.68) |

| 3. How do you feel about getting pregnant or getting a girl pregnant? (5 = very bad, 1 = very good) | 4.61 (0.95) | 4.46 (1.08) | 4.58 (0.96) |

| Vulnerability (Cronbach α = .75) | 1.59 (0.81) | 1.74 (0.92) | 1.67 (0.85) |

| 1. In the next 6 months I will become infected with HIV. (5 = very likely, 1 = very unlikely) | 1.50 (0.91) | 1.69 (1.09) | 1.62 (0.98) |

| 2. In the next 6 months I will get an STD. (5 = very likely, 1 = very unlikely) | 1.57 (0.92) | 1.63 (1.03) | 1.62 (0.95) |

| 3. In the next 6 months I will get pregnant/get a girl pregnant. (5 = very likely, 1 = very unlikely) | 1.70 (1.07) | 1.89 (1.28) | 1.84 (1.08) |

| Coping appraisal | |||

| Self efficacy (Cronbach α = .87) | 2.55 (1.16)b | 2.27 (1.17) | 2.38 (1.17) |

| 1. I could get condoms. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 2.57 (1.61)b | 2.27 (1.56) | 2.36 (1.58) |

| 2. I could put on a condom correctly. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 2.41 (1.45) | 2.19 (1.46) | 2.25 (1.41) |

| 3. I could convince my sexual partner to use a condom. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 2.86 (1.67) | 2.46 (1.64)§ | 2.73 (1.61) |

| 4. I could ask for condoms in a store. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 2.26 (1.44) | 1.99 (1.41) | 2.13 (1.36) |

| 5. I could ask for condoms in a clinic. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 2.23 (1.38) | 1.99 (1.36) | 2.08 (1.29) |

| 6. I could refuse to have sex if my partner will not use a condom. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 3.03 (1.69)b | 2.66 (1.66) | 2.78 (1.64) |

| Response efficacy (Cronbach α = .71) | 3.95 (0.94) | 3.93 (0.96) | 3.87 (0.97) |

| 1. Condoms are an important way to prevent a pregnancy. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 3.97 (1.16) | 3.79 (1.31) | 3.88 (1.23) |

| 2. Condoms are an important way to prevent you from getting an STD. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 3.90 (1.19) | 4.02 (1.17)a | 3.82 (1.20) |

| 3. Condoms are an important way to prevent you from getting AIDS. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 4.01 (1.14) | 3.96 (1.18) | 3.91 (1.17) |

| Response cost (Cronbach α = .39) | 3.33 (0.54)b | 3.29 (0.58) | 3.24 (0.59) |

| 1. If a girl carries condoms people think she is having sex. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 4.09 (1.11) | 4.13 (1.11) | 4.00 (1.19) |

| 2. Condoms make sex hurt for a girl. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 3.07 (0.94) | 3.04 (1.10) | 3.07 (1.03) |

| 3. Condoms take away the feelings that a guy has during sex. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 3.05 (0.94) | 2.97 (1.07) | 3.01 (0.97) |

| 4. When a guy and a girl are in a serious relationship they don’t use condoms. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 3.22 (1.08) | 3.25 (1.21) | 3.10 (1.16) |

| 5. Youth don’t want other youth to think they are using condoms. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 3.15 (1.15) | 2.97 (1.25) | 3.04 (1.21) |

| 6. It would be difficult for a young girl/boy to ask an older man to use a condom. (5 = strongly agree, 1 = strongly disagree) | 3.42 (1.20)b | 3.35 (1.29) | 3.23 (1.19) |

NA indicates not available; STD indicates sexually transmitted disease.

P < .01.

P < .05.

Intention

Intention to engage in sex was measured using the question, “How likely is it that you will have sex in the next six months?” Intention to use a condom was measured using the question, “If you were to have sex in the next six months, how likely is it that you (your partner) would use a condom?” The possible answers for both questions ranged on a 5-point Likert scale from 5, “very likely,” to 1, “very unlikely.”

Abstinence/Sexual Initiation and Condom Use

Abstinence/Sexual Initiation

Abstinence was defined based on both vaginal and anal sex. Subjects who reported never having had vaginal or anal sex throughout the follow-up period were coded as practicing abstinence; if they engaged in either or both forms of sex they were classified as having initiated sex.

Condom Use

Condom use was measured using the item, “How often did you use a condom when you had sex?” with the following choices: (1) “never used a condom,” (2) “used a condom sometimes,” and (3) “always used a condom.” Condom use was only assessed among the youth who reported having initiated sex. For analytic purposes, we were interested in consistent condom use; a selection of the response “always used a condom” represented consistent condom use, whereas all of the other selections represented inconsistent condom use.

Statistical Analysis

We assessed the following sets of intervention effects: (1) the effect of the youth intervention plus the parent career planning intervention (FOYC/GFI versus control); (2) the effect of the youth intervention and the parental monitoring and communication intervention (FOYC/CImPACT versus control); and (3) the effect of the youth intervention regardless of the parent intervention (FOYC [including both FOYC/GFI and FOCY/CImPACT youth] versus control). Before program effect evaluation, baseline equivalence between the 2 youth intervention groups and the control group was assessed using χ2 (for categorical variables) and analysis of variance for continuous variables.

Because subjects were randomly assigned into intervention conditions by schools in this trial, program effect for dichotomous outcome measures (eg, condom use and abstinence/sexual initiation) was assessed using the generalized linear mixed model, and program effect for continuous measures (eg, HIV/AIDS knowledge, PMT constructs, and intentions) was assessed using the mixed model. These 2 methods were used because of their ability to analyze data with repeated measurements and to adjust for the effect of intraclass correlation attributed to the schools-based randomization.43,44 Both the continuous and the dichotomous outcome measures were used as dependent variables. Intervention groups (eg, FOYC/GFI, FOYC/CImPACT, or FOYC [both parent intervention groups] and WW/GFI) were entered as the predictor variables in addition to covariates, including age, gender, and baseline measurements. The compound symmetry was specified as the covariance structure for the mixed modeling to adjust for the correlation of repeated measures. The intraclass correlation was assessed by specifying the random effects at the school level. For program effect assessed at each follow-up point, a β coefficient for an intervention condition at the P < .05 level was used as evidence of significant program effect. We assessed program effect at each follow-up point first and then the effect across the whole 24-month period. For program effect across the whole period from the baseline to 24-month follow-up, a significant interaction between an intervention and time (from type III tests of fixed effects) for an F value at the P < .05 level was used as evidence supporting the existence of program effect. Proc generalized linear mixed model and Proc mixed from the software SAS 9.13 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) were used to conduct the analyses.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics and Follow-up Rates

As shown in Table 2, approximately one third of baseline participants received FOYC/GFI, FOYC/CImPACT, or WW/GFI, respectively. Approximately two thirds of the participants were 10 years of age at baseline; only 4% of participants were sexually experienced, and 16% of the youth with sexual experience always used a condom at baseline.

TABLE 2.

Baseline Characteristics of the Participants in the Bahamas, by Intervention Assignment

| Characteristics | Overall | Intervention | Control: WW/GFI |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOYC/GFI | FOYC/CImPACT | Subtotal FOYC | |||

| Total samples, N (%) | 1360 | 427 | 436 | 863 | 497 |

| Boys | 639 (47.0) | 180 (42.2) | 231 (53.0)a | 411 (47.6) | 228 (45.9) |

| Girls | 721 (53.0) | 247 (57.8) | 205 (47.0) | 452 (52.4) | 269 (54.1) |

| Suspended school, N (%) | 30 (2.3) | 14 (3.3) | 9 (2.1) | 23 (2.7) | 7 (1.4) |

| Played hooky, N (%) | 61 (4.6) | 20 (4.8) | 22 (5.3) | 42 (5.0) | 19 (3.9) |

| Age in years | |||||

| ~10, N (%) | 837 (62.9) | 273 (65.5) | 259 (60.7)b | 532 (63.0)a | 305 (62.8) |

| ~11, N (%) | 386 (29.0) | 116 (27.8) | 115 (26.9) | 231 (27.4) | 155 (31.9) |

| ≥12, N (%) | 107 (8.1) | 28 (6.7) | 53 (12.4) | 81 (9.6) | 26 (5.3) |

| Mean (SD) | 10.5 (0.7) | 10.4 (0.6) | 10.5 (0.8)a | 10.4 (0.7) | 10.4 (0.6) |

| HIV/AIDS knowledge, mean (SD) | |||||

| Overall | 0.71 (0.16) | 0.72 (0.16) | 0.71 (0.16) | 0.72 (0.16) | 0.70 (0.17) |

| Transmission | 0.75 (0.21) | 0.75 (0.21) | 0.76 (0.20) | 0.75 (0.21) | 0.75 (0.21) |

| Prevention | 0.67 (0.22) | 0.69 (0.21)a | 0.66 (0.21) | 0.68 (0.21) | 0.66 (0.23) |

| Abstinence/sexual initiation, PMT perception | |||||

| Threat appraisal, mean (SD) | |||||

| Extrinsic reward | 1.70 (0.76) | 1.70 (0.75) | 1.78 (0.79)b | 1.74 (0.77)a | 1.64 (0.74) |

| Intrinsic reward | 1.55 (1.10) | 1.61 (1.18) | 1.57 (1.09) | 1.59 (1.13) | 1.47 (1.05) |

| Perceived severity | 4.69 (0.64) | 4.73 (0.60) | 4.62 (0.70) | 4.67 (0.66) | 4.70 (0.62) |

| Perceived Vulnerability | 1.67 (0.86) | 1.59 (0.81) | 1.74 (0.91) | 1.67 (0.86) | 1.67 (0.85) |

| Coping appraisal, mean (SD) | |||||

| Self-efficacy | 3.63 (1.03) | 3.76 (0.96)a | 3.55 (1.09) | 3.65 (1.03) | 3.61 (1.03) |

| Response efficacy | 4.07 (0.94) | 4.08 (0.90) | 3.98 (1.04)a | 4.03 (0.97) | 4.13 (0.88) |

| Response cost | 2.48 (.087) | 2.48 (0.78) | 2.50 (0.95) | 2.49 (0.87) | 2.45 (0.87) |

| Condom-use, PMT perception | |||||

| Threat appraisal, mean (SD) | |||||

| Extrinsic reward | 2.54 (1.54) | 2.47 (1.49) | 2.71 (1.52) | 2.60 (1.51) | 2.42 (1.61) |

| Intrinsic reward | 3.08 (1.00) | 2.98 (0.93)b | 3.08 (1.04) | 3.03 (0.99)a | 3.17 (1.00) |

| Perceived severity | 4.69 (0.64) | 4.73 (0.60) | 4.62 (0.70) | 4.67 (0.66) | 4.70 (0.62) |

| Perceived vulnerability | 1.67 (0.86) | 1.59 (0.81) | 1.74 (0.91) | 1.67 (0.86) | 1.67 (0.85) |

| Coping appraisal, mean (SD) | |||||

| Self-efficacy | 2.40 (1.17) | 2.55 (1.16)a | 2.27 (1.17) | 2.41 (1.17) | 2.38 (1.17) |

| Response efficacy | 3.92 (0.96) | 3.95 (0.94) | 3.93 (0.96) | 3.94 (0.95) | 3.87 (0.97) |

| Response cost | 3.28 (0.57) | 3.33 (0.54)a | 3.29 (0.58) | 3.31 (0.56)a | 3.24 (0.59) |

| Intention to engage in sex, mean (SD) | 1.79 (1.18) | 1.76 (1.18) | 1.88 (1.27) | 1.82 (1.23) | 1.74 (1.08) |

| Intention to use a condom, mean (SD) | 2.92 (1.67) | 2.85 (1.70) | 3.14 (1.67)b | 3.00 (1.69)a | 2.80 (1.62) |

| Sexual initiation, N (%) | 1305 (4.0) | 414 (3.0) | 413 (5.3) | 827 (4.2) | 478 (3.8) |

| Always use a condom (among sexually experienced youth), N (%) | 9 (16.4) | 3 (23.1) | 4 (17.4) | 7 (19.4) | 2 (10.5) |

Data are on a scale from 1 to 5, with higher values on the self-efficacy, response efficacy, severity, and vulnerability subscales and lower values on the intrinsic rewards, extrinsic rewards, and response cost subscales indicating a protective effect.

P < .05.

P < .01.

At baseline, the FOYC/CImPACT group had significantly more boys and older youth compared with the control group (WW/GFI). Significant baseline differences also existed in the following subscales: HIV/AIDS prevention knowledge; abstinence-related extrinsic rewards, self-efficacy, and response efficacy; condom-use-related intrinsic rewards, self-efficacy, and response cost; and intention to use a condom. As noted earlier, these baseline differences were controlled in the subsequent analyses to assess program effect.

Intervention Effects; HIV/AIDS Knowledge

Compared with the control group, youth receiving FOYC demonstrated significantly higher levels of HIV/AIDS knowledge, including the overall knowledge score and the transmission score in all of the follow-ups from 12 to 24 months postintervention and the prevention knowledge score in the 18- and the 24-month follow-ups, controlling for age, gender, and baseline knowledge (see Table 3). Interaction between time and intervention through type III tests of fixed effects further demonstrated that increases in HIV/AIDS knowledge over the 24-month period were statistically significant for FOYC/CImPACT (F = 2.68 and P < .05 for transmission knowledge), FOYC/GFI (F = 5.45 and P < .01 for overall knowledge; F = 6.21 and P < .01 for transmission knowledge), and FOYC (F = 5.13 and P < .01 for overall knowledge; F = 69.8 and P < .01 for transmission knowledge; and F = 2.77 and P < .05 for prevention knowledge).

TABLE 3.

Intervention Effect on HIV/AIDS Knowledge at 12-, 18-, and 24-Month Follow-ups

| Constructs, HIV/AIDS Knowledge, Mean (95% CI) |

Intervention | Control: WW/ GFI |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOYC/GFI | FOYC/CImPACT | Subtotal FOYC | ||

| Overall | ||||

| 12 mo | 0.84 (0.80–0.87)a | 0.83 (0.80–0.86)b | 0.83 (0.81–0.85)a | 0.79 (0.76–0.82) |

| 18 mo | 0.88 (0.84–0.91)c | 0.86 (0.83–0.90)a | 0.87 (0.85–0.89)c | 0.80 (0.77–0.83) |

| 24 mo | 0.89 (0.87–0.91)c | 0.88 (0.86–0.91)c | 0.89 (0.87–0.90)c | 0.83 (0.80–0.85) |

| Transmission | ||||

| 12 mo | 0.87 (0.84–0.91)c | 0.86 (0.83–0.89)a | 0.87 (0.84–0.89)c | 0.80 (0.77–0.83) |

| 18 mo | 0.91 (0.87–0.95)a | 0.90 (0.86–0.94)a | 0.90 (0.88–0.93)c | 0.84 (0.80–0.88) |

| 24 mo | 0.92 (0.89–0.94)c | 0.91 (0.89–0.93)c | 0.91 (0.90–0.93)c | 0.86 (0.84–0.88) |

| Prevention | ||||

| 12 mo | 0.80 (0.76–0.83) | 0.79 (0.76–0.83) | 0.80 (0.77–0.82) | 0.77 (0.73–0.80) |

| 18 mo | 0.85 (0.81–0.88)c | 0.83 (0.80–0.87)a | 0.84 (0.82–0.86)c | 0.76 (0.73–0.80) |

| 24 mo | 0.86 (0.83–0.90)c | 0.86 (0.83–0.89)c | 0.86 (0.84–0.88)c | 0.79 (0.76–0.82) |

The effect was adjusted for age, gender, and baseline difference. Data are on a scale from 0 to 1, with higher value indicating greater knowledge.

P < .05.

P < .10.

P < .01.

PMT-Related Constructs

Abstinence/Sexual Initiation Perception

Relevant to the coping appraisal pathway, compared with control youth, FOYC/GFI youth experienced significantly increased self-efficacy and response efficacy to remain abstinent/refuse sex at 12, 18, and 24 months and significantly reduced response cost at 12 and 24 months. FOYC/CImPACT significantly enhanced response efficacy and marginally reduced response cost of abstinence/sexual refusal at 24 months. Relevant to threat appraisal pathway perceptions, marginally increased perceptions of vulnerability to the consequences of sex among FOYC/CImPACT youth were found at 18 and 24 months (see Table 4). Likewise, the mixed-model analyses with time-intervention interactions indicated that increases in response efficacy and declines in response cost over 24 months were statistically significant for FOYC/GFI (F = 3.82 and P < .01 for response efficacy; F = 2.78 and P < .05 for response cost) and FOYC (F = 3.81 and P < .01 for response efficacy; F = 2.92 and P < .05 for response cost).

TABLE 4.

Intervention Effect on PMT Perceptions of Abstinence/Sexual Initiation and Condom Use at 12-, 18-, and 24-Month Follow-ups

| Constructs | Intervention | Control: WW/ GFI |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOYC/GFI | FOYC/CImPACT | Subtotal FOYC | ||

| Abstinence/sexual initiation perception | ||||

| Threat appraisal, mean (95% CI) | ||||

| Extrinsic rewards | ||||

| 12 mo | 1.75 (1.62–1.87) | 1.87 (1.74–1.99) | 1.81 (1.72–1.90) | 1.76 (1.64–1.88) |

| 18 mo | 1.82 (1.72–1.93) | 2.01 (1.90–2.11)a | 1.91 (1.82–2.01) | 1.88 (1.78–1.98) |

| 24 mo | 1.89 (1.76–2.01) | 2.08 (1.96–2.21)a | 1.99 (1.89–2.09) | 1.92 (1.80–2.05) |

| Intrinsic rewards | ||||

| 12 mo | 1.80 (1.64–1.95) | 1.69 (1.54–1.84) | 1.74 (1.64–1.85) | 1.70 (1.55–1.85) |

| 18 mo | 1.95 (1.81–2.08) | 1.90 (1.76–2.03) | 1.92 (1.83–2.01) | 1.84 (1.71–1.97) |

| 24 mo | 1.95 (1.76–2.14) | 2.13 (1.94–2.31) | 2.04 (1.90–2.18) | 1.94 (1.76–2.13) |

| Perceived severity | ||||

| 12 mo | 4.79 (4.72–4.85) | 4.74 (4.68–4.80) | 4.76 (4.72–4.81) | 4.80 (4.73–4.86) |

| 18 mo | 4.76 (4.70–4.82) | 4.72 (4.66–4.78) | 4.74 (4.70–4.78) | 4.76 (4.70–4.82) |

| 24 mo | 4.83 (4.77–4.88) | 4.69 (4.64–4.75)b | 4.76 (4.71–4.81) | 4.80 (4.74–4.85) |

| Perceived vulnerability | ||||

| 12 mo | 1.31 (1.24–1.39) | 1.39 (1.31–1.46) | 1.35 (1.30–1.40) | 1.37 (1.30–1.44) |

| 18 mo | 1.31 (1.21–1.41) | 1.43 (1.33–1.53)a | 1.37 (1.30–1.44) | 1.29 (1.20–1.39) |

| 24 mo | 1.26 (1.16–1.37) | 1.39 (1.29–1.50)a | 1.33 (1.25–1.41) | 1.27 (1.16–1.37) |

| Coping appraisal, mean (95% CI) | ||||

| Self-efficacy | ||||

| 12 mo | 4.03 (3.91–4.15)b | 3.93 (3.81–4.05) | 3.98 (3.89–4.07)a | 3.84 (3.72–3.95) |

| 18 mo | 4.07 (3.97–4.17)a | 3.99 (3.89–4.09) | 4.03 (3.97–4.09)a | 3.94 (3.84–4.03) |

| 24 mo | 4.10 (4.01–4.20)b | 4.09 (4.00–4.19)a | 4.10 (4.04–4.16)b | 3.97 (3.88–4.06) |

| Response efficacy | ||||

| 12 mo | 4.37 (4.23–4.51)b | 4.26 (4.12–4.40) | 4.31 (4.21–4.42)a | 4.14 (4.00–4.28) |

| 18 mo | 4.36 (4.25–4.47)b | 4.20 (4.09–4.31) | 4.28 (4.19–4.37) | 4.20 (4.09–4.30) |

| 24 mo | 4.28 (4.19–4.37)c | 4.22 (4.13–4.32)b | 4.25 (4.19–4.32)c | 4.09 (4.00–4.18) |

| Response cost | ||||

| 12 mo | 2.24 (2.11–2.36)b | 2.33 (2.21–2.46) | 2.29 (2.19–2.38)b | 2.45 (2.33–2.57) |

| 18 mo | 2.27 (2.17–2.37) | 2.42 (2.32–2.52)a | 2.34 (2.26–2.43) | 2.29 (2.20–2.39) |

| 24 mo | 2.29 (2.21–2.38)b | 2.31 (2.23–2.39)a | 2.30 (2.25–2.36)b | 2.42 (2.34–2.50) |

| Condom-use perception | ||||

| Threat appraisal, mean (95% CI) | ||||

| Extrinsic rewards | ||||

| 12 mo | 3.24 (2.80–3.67)a | 2.75 (2.38–3.11) | 2.95 (2.69–3.20) | 2.73 (2.32–3.15) |

| 18 mo | 2.98 (2.59–3.37) | 3.36 (3.03–3.70) | 3.20 (2.97–3.43) | 3.15 (2.77–3.52) |

| 24 mo | 3.31 (2.93–3.70) | 3.14 (2.81–3.46) | 3.21 (2.96–3.47) | 3.17 (2.82–3.53) |

| Intrinsic rewards | ||||

| 12 mo | 3.00 (2.91–3.10) | 2.90 (2.80–3.00) | 2.95 (2.88–3.02) | 3.00 (2.91–3.09) |

| 18 mo | 2.98 (2.89–3.07) | 2.89 (2.80–2.98) | 2.94 (2.87–3.00) | 2.92 (2.83–3.00) |

| 24 mo | 2.98 (2.89–3.07) | 2.92 (2.83–3.01) | 2.95 (2.89–3.02) | 3.01 (2.92–3.10) |

| Perceived severity | ||||

| 12 mo | 4.79 (4.72–4.85) | 4.74 (4.68–4.80) | 4.76 (4.72–4.81) | 4.80 (4.73–4.86) |

| 18 mo | 4.76 (4.70–4.82) | 4.72 (4.66–4.78) | 4.74 (4.70–4.78) | 4.76 (4.70–4.82) |

| 24 mo | 4.83 (4.77–4.88) | 4.69 (4.64–4.75)b | 4.76 (4.71–4.81) | 4.80 (4.74–4.85) |

| Perceived vulnerability | ||||

| 12 mo | 1.31 (1.24–1.39) | 1.39 (1.31–1.46) | 1.35 (1.30–1.40) | 1.37 (1.30–1.44) |

| 18 mo | 1.31 (1.21–1.41) | 1.43 (1.33–1.53)a | 1.37 (1.30–1.44) | 1.29 (1.20–1.39) |

| 24 mo | 1.26 (1.16–1.37) | 1.39 (1.29–1.50)a | 1.33 (1.25–1.41) | 1.27 (1.16–1.37) |

| Coping appraisal, mean (95% CI) | ||||

| Self-efficacy | ||||

| 12 mo | 3.18 (2.99–3.37)b | 3.18 (2.99–3.36)b | 3.18 (3.05–3.30)c | 2.85 (2.66–3.03) |

| 18 mo | 3.55 (3.42–3.69)c | 3.51 (3.37–3.64)c | 3.53 (3.43–3.62)c | 3.04 (2.91–3.17) |

| 24 mo | 3.57 (3.46–3.68)c | 3.59 (3.48–3.70)c | 3.58 (3.51–3.65)c | 3.15 (3.04–3.26) |

| Response efficacy | ||||

| 12 mo | 4.27 (4.12–4.42)b | 4.27 (4.12–4.41)b | 4.27 (4.17–4.37)c | 4.01 (3.86–4.15) |

| 18 mo | 4.31 (4.18–4.44)b | 4.39 (4.26–4.52)c | 4.35 (4.26–4.44)c | 4.10 (3.97–4.23) |

| 24 mo | 4.22 (4.11–4.33)c | 4.31 (4.20–4.41)c | 4.27 (4.19–4.34)c | 3.98 (3.88–4.08) |

| Response cost | ||||

| 12 mo | 3.32 (3.26–3.38) | 3.28 (3.22–3.34) | 3.30 (3.26–3.34) | 3.27 (3.21–3.33) |

| 18 mo | 3.32 (3.25–3.39) | 3.26 (3.19–3.33) | 3.29 (3.24–3.34) | 3.34 (3.27–3.41) |

| 24 mo | 3.25 (3.19–3.30) | 3.27 (3.22–3.33) | 3.26 (3.23–3.30) | 3.28 (3.22–3.33) |

| Intention to engage in sex, mean (95% CI) | ||||

| 12 mo | 1.79 (1.61–1.96) | 1.82 (1.64–1.99) | 1.80 (1.68–1.92) | 1.74 (1.56–1.91) |

| 18 mo | 1.76 (1.54–1.98) | 1.96 (1.73–2.18) | 1.86 (1.70–2.01) | 1.74 (1.53–1.96) |

| 24 mo | 1.84 (1.67–2.02) | 2.04 (1.87–2.21) | 1.94 (1.81–2.07) | 1.88 (1.71–2.04) |

| Intention to use a condom, mean (95% CI) | ||||

| 12 mo | 3.67 (3.22–4.13) | 3.75 (3.30–4.21) | 3.71 (3.41–4.02) | 3.48 (3.03–3.93) |

| 18 mo | 3.75 (3.00–4.50) | 3.82 (3.06–4.57) | 3.78 (3.28–4.29) | 3.09 (2.34–3.84) |

| 24 mo | 4.20 (3.99–4.41)c | 4.18 (3.97–4.39)c | 4.19 (4.05–4.33)c | 3.70 (3.50–3.90) |

The effect was adjusted for age, gender, and baseline difference. Data are on a scale from 1 to 5, with higher values on the self-efficacy, response efficacy, severity, and vulnerability subscales and lower values on the intrinsic rewards, extrinsic rewards, and response cost subscales indicating a protective effect.

P < .10.

P < .05.

P < .01.

Condom Use Perceptions

Relevant to the coping appraisal pathway constructs, condom-use self-efficacy and response efficacy among both FOYC/GFI and FOYC/CImPACT youth were significantly higher than among control youth at 12, 18, and 24 months, respectively (see Table 4). The mixedmodel analyses of the time-intervention interaction over 24 months indicated that self-efficacy and response efficacy were positively associated with the intervention for FOYC/CImPACT (F = 7.49 and P < .01 for self-efficacy; F = 3.04, and P < .05 for response efficacy) and for FOYC (F = 5.59 and P < .01 for self-efficacy; F = 2.96 and P < .05 for response efficacy). Threat appraisal pathway constructs were not significantly different at each follow-up point and over the 24-month period, although marginal protective changes (increased perceived vulnerability) were seen among youth in the FOYC/CImPACT group at 18 and 24 months (see Table 4).

Intention

There were no significant intervention effects on intention to engage in sex at any follow-up period. All of the children receiving the FOYC intervention and the subgroup of youth who received the FOYC intervention whose parents received CImPACT exhibited significantly enhanced condom use intention at 24 months (see Table 4). Type III tests of the fixed effect over the 24-month period indicated that none of the changes on intention to use a condom (F = 0.15–0.74; P > .05 for all) or on intention to have sex (F = 0.25–1.62; P > .05 for all) were significant.

Abstinence/Sexual Initiation and Condom Use Behaviors

As shown in Table 5, rates of sexual initiation did not differ based on intervention status. There was a consistent trend for higher rates of condom use among intervention groups (FOYC/GFI and FOYC/CImPACT) than among control subjects, although only at 24 months did this apparent difference between FOYC and WW achieve marginal significance (29.8% of FOYC youth versus 20.0% of WW/GFI youth used a condom; P = .095). Type III tests of the fixed effect over the 24-month interval indicated no significant intervention effect on abstinence/sexual initiation (F = 0.26–0.29 and P > .05 for all) or condom use (F = 0.13–0.28 and P > .05 for all).

TABLE 5.

Intervention Effect on Condom Use and Sexual Initiation at 12-, 18- and 24-Month Follow-ups: Results From Generalized Mixed Modeling Analysis

| Item | 12- Month Follow- up |

18-Month Follow-up |

24- Month Follow- up |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Adjusted Rate (%) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Rate (%) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Adjusted Rate (%) |

||||

| Sexual initiation | ||||||

| FOYC | 14.7 | 1.04 (0.53–2.06) | 20.5 | 1.28 (0.80–2.04) | 27.3 | 1.17 (0.77–1.77) |

| FOYC/GFI | 13.1 | 0.86 (0.38–1.94) | 19.2 | 1.14 (0.66–2.00) | 24.5 | 0.97 (0.61–1.54) |

| FOYC/CImPACT | 16.2 | 1.24 (0.57–2.69) | 21.7 | 1.40 (0.82–2.40) | 30.1 | 1.38 (0.89–2.14) |

| Control | 14.3 | — | 17.5 | — | 24.5 | — |

| Condom use among the youth with sexual experience | ||||||

| FOYC | 23.9 | 1.94 (0.71–5.30) | 24.4 | 1.50 (0.62–3.67) | 29.8 | 1.72 (0.90–3.30)a |

| FOYC/GFI | 17.8 | 1.40 (0.40–4.92) | 27.0 | 1.70 (0.58–4.96) | 30.4 | 1.77 (0.82–3.83) |

| FOYC/CImPACT | 28.0 | 2.33 (0.79–6.88) | 22.2 | 1.35 (0.48–3.77) | 29.5 | 1.69 (0.83–3.45) |

| Control | 13.1 | — | 17.2 | — | 20.0 | — |

The effect was adjusted for age, gender, and baseline difference.—reference group for comparison.

P < .10.

DISCUSSION

The results in this study indicate significant protective effects of FOYC (including both FOYC/GFI and FOYC/CImPACT) on HIV/AIDS knowledge, self-efficacy, response efficacy, response cost, vulnerability, and condom use intention from 12 months to 24 months postintervention. These effects have been tested through both preanalysis/postanalysis and trend analysis over the 24-month study period. Taken with the short-term (6-month follow-up) protective effects reported earlier,39 these results demonstrate an intervention effect sustained over 2 years among these youth who were preadolescents at the time of intervention delivery. Although not significant, there was an encouraging trend for higher condom use among youth receiving the FOYC intervention compared with control youth through 24 months postintervention.

Similar to findings in the previous literature regarding PMT-based behavioral interventions among older adolescents and adults,45–47 the interventions in the present study demonstrated a strong effect on the coping-appraisal perceptions but a weak effect on threat-appraisal perceptions for both abstinence and condom use. Particularly for self-efficacy and response efficacy, the intervention effects were robust and stable, enduring through 24 months for both condom use and abstinence.

By contrast, among the threat-appraisal constructs, only perceived vulnerability was impacted by the intervention. Consistent with findings from other studies,48–50 our study did not result in an intervention impact on perceived severity, a finding that may result from the widespread recognition of the severity of HIV/AIDS (eg, a ceiling effect).51 Supporting this hypothesis is the fact that, at baseline, the mean severity score was 4.69 (SD: 0.64) of a possible maximum score of 5.00.

The data in the present study suggest that there may be an intervention effect on condom use. These findings are consistent with but not as strong as our experience with FOK alone23,38 and with FOK plus ImPACT among midadolescents and their parents in the United States,23,38 where the differences were statistically significant. In the present study, a trend was present through the follow-up periods, which did reach marginal significance (P = .095) at 24 months among the youth who received the FOYC intervention. It may be that the low prevalence of sexual behaviors among preadolescents may limit our ability to detect significant effects. Alternatively, the addition of the parental monitoring, communication, and HIV intervention may have been less effective among the parents and preadolescent youth in the present study (average age: 10 years old) compared with the ImPACT effect on youth in the US study (average age: 13 years old),38 because the Bahamian parents might not feel comfortable discussing sex and condom use with such young children. In addition, CImPACT was delivered in a group setting to the parents without their children rather than to the individual parent-child dyad, as had been done in the US study.38 The group delivery format may not have enhanced parent-adolescent communication skills regarding sexual risk and protective behaviors in part because many of the parent-youth dyads were not able to practice these skills in the session after the video. There also may be cultural and communication differences in the Bahamas that limit a parental intervention that focuses on discussions about sex between a parent and his or her child. Both parents and children stated during intervention preparation that such conversations are not prevalent in Bahamian society.39 Finally, consistent with the concerns that we discussed in the Introduction regarding the developmental aspects of reasoning,36,37 it may be that the level of abstract reasoning of some of these preadolescents was insufficient to enable full appreciation and, therefore, benefit from the concepts being presented in the FOYC curriculum.

The low rate of sexual activity among the study participants limits our ability to assess with confidence the intervention effects on actual condom use and other behavioral outcomes. In addition, the low Cronbach α values for a few of the PMT subscales may impact stability of measurement over time, such as response cost for abstinence, which was significantly associated with intervention at 12 and 24 months but not at 18 months. The wording of the questions and the actual questions used to form the subscales had been developed among older youth in a different (US) culture,42 which may have contributed to the low Cronbach α values seen in the present study.

CONCLUSIONS

The sexual risk-reduction intervention program FOYC based on the social cognitive theory PMT can positively and persistently impact risk and protective perceptions and intentions of preadolescents living in the Bahamas. These protective effects are similar to those reported for older adolescents.6,38 There was a suggested protective effect on condom use behavior, but this effect was not significant among these preadolescent youth. Additional follow-up as more youth initiate sex is necessary to determine whether the protective effect achieves statistical significance with adequate power and whether this effect endures over time. These results provide support for offering structured, interactive, sexual risk reduction interventions to preadolescents in high-risk settings before the onset of sexual activity.

What’s Known on This Subject

FOYC and CImPACT, the preventive intervention program developed from Focus on Kids and Informed Parents and Children Together and based on protection motivation theory, had demonstrated short-term effects in perception and knowledge at 6 months among preadolescents.

What This Study Adds

The long-term intervention effects through 24 months are addressed in this current article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the National Institute/National of Mental Health (R01MH069229).

We thank the Ministries of Health and Education, Dr Perry Gomez, Director National HIV and AIDS Program; Rosa Mae Bain, Managing Director HIV and AIDS Centre; and school administration, classroom teachers, and nurses for their support in the study. We also thank all of the parents and students who participated in this study.

Abbreviations

- PMT

protection motivation theory

- FOK

Focus on Kids

- ImPACT

Informed Parents and Children Together

- GFI

Goal for It

- FOYC

Focus on Youth in the Caribbean

- CImPACT

Informed Parents and Children Together in the Caribbean

- WW

Wondrous Wetlands

Footnotes

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online: http://www.pediatrics.org/misc/reprints.shtml

REFERENCES

- 1.Singhal A, Rogers EM. Combating AIDS: Communication Strategies in Action. New Delhi, India: Sage Publications Ltd; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdool Karim SS, Abdool Karim Q, Gouws E, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV-AIDS. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007;21(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.01.010. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hessol NA, Byers RH, Lifson AR, et al. Relationship between AIDS latency period and AIDS survival time in homosexual and bisexual men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1990;3(11):1078–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paul-Ebhohimhen VA, Poobalan A, van Teijlingen ER. A systematic review of school-based sexual health interventions to prevent STI/HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenstock IM. Why people use health services. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44(3 suppl):94–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker MH, Maiman LA, Kirscht JP, et al. The Health Belief Model and prediction of dietary compliance: a field experiment. J Health Soc Behav. 1977;18(4):348–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Theory-based behavior change interventions: comments on Hobbis and Sutton. J Health Psychol. 2005;10(1):27–31. doi: 10.1177/1359105305048552. discussion 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ouimet MC, Morton BG, Noelcke EA, et al. Perceived risk and other predictors and correlates of teenagers’ safety belt use during the first year of licensure. Traffic Inj Prev. 2008;9(1):1–10. doi: 10.1080/15389580701638793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood ME. Theoretical framework to study exercise motivation for breast cancer risk reduction. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35(1):89–95. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.89-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lwin MO, Saw SM. Protecting children from myopia: a PMT perspective for improving health marketing communications. J Health Commun. 2007;12(3):251–268. doi: 10.1080/10810730701266299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright AJ, French DP, Weinman J, et al. Can genetic risk information enhance motivation for smoking cessation?: an analogue study. Health Psychol. 2006;25(6):740–752. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.6.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaffer SD, Tian L. Promoting adherence: effects of theory-based asthma education. Clin Nurs Res. 2004;13(1):69–89. doi: 10.1177/1054773803259300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helmes AW. Application of the protection motivation theory to genetic testing for breast cancer risk. Prev Med. 2002;35(5):453–462. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Runge C, Prentice-Dunn S, Scogin F. Protection motivation theory and alcohol use attitudes among older adults. Psychol Rep. 1993;73(1):96–98. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1993.73.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers RW, Deckner CW. Effects of fear appeals and physiological arousal upon emotion, attitudes, and cigarette smoking. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1975;32(2):222–230. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.32.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogers RW, Prentice-Dunn S. Cognitive and physiological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: a revised theory of protection motivation. In: Gochman DS, editor. Handbook of Health Behavior Research: I–Personal and Social Determinants. New York, NY: Plenum; 1983. pp. 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bengel J, Belz-merk M, Farin E. The role of risk perception and efficacy cognitions in the prediction of HIV-related preventive behavior and condom use. Psychol Health. 1996;11(4):505–525. doi: 10.1080/08870449608401986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu S, Marshall S, Cottrell L, et al. Longitudinal predictability of sexual perceptions on subsequent behavioural intentions among Bahamian preadolescents. Sex Health. 2008;5(1):31–39. doi: 10.1071/sh07040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaljee LM, Genberg B, Riel R, et al. Effectiveness of a theory-based risk reduction HIV prevention program for rural Viet-namese adolescents. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17(3):185–199. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.4.185.66534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boer H, Mashamba MT. Psychosocial correlates of HIV protection motivation among black adolescents in Venda, South Africa. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17(6):590–602. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2005.17.6.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boer H, Mashamba MT. Gender power imbalance and differential psychosocial correlates of intended condom use among male and female adolescents from Venda, South Africa. Br J Health Psychol. 2007;2(pt 1):51–63. doi: 10.1348/135910706X102104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bakker AB, Buunk BP, Siero FW. Condom use among heterosexuals: a comparison of the theory of planned behavior, the health belief model and protection motivation theory. Gedrag Gezond. 1993;21(5):238–254. [in Dutch]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanton B, Fang X, Li X, et al. Evolution of risk behaviors over 2 years among a cohort of urban African American adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(4):398–406. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170410072010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stanton B, Cole M, Galbraith J, et al. Randomized trial of a parent intervention: parents can make a difference in long-term adolescent risk behaviors, perceptions, and knowledge. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(10):947–955. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.10.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Stanton B, Feigelman S. Impact of perceived parental monitoring on adolescent risk behavior over 4 years. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanton B, Li X, Pack R, et al. Longitudinal influence of perceptions of peer and parental factors on African American adolescent risk involvement. J Urban Health. 2002;79(4):536–548. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.4.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeVore ER, Ginsburg KR. The protective effects of good parenting on adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2005;17(4):460–465. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000170514.27649.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, et al. HIV/STD-protective benefits of living with mothers in perceived supportive families: a study of high-risk African American female teens. Prev Med. 2001;33(3):175–178. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beck KH, Boyle JR, Boekeloo BO. Parental monitoring and adolescent alcohol risk in a clinic population. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27(2):108–115. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.2.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinberg L, Fletcher A, Darling N. Parental monitoring and peer influences on adolescent substance use. Pediatrics. 1994;3(6 pt 2):1060–1064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dittus PJ, Jaccard J. Adolescents’ perceptions of maternal disapproval of sex: relationship to sexual outcomes. J Adolesc Health. 2000;26(4):268–278. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278(10):823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaestle CE, Halpern CT, Miller WC, et al. Young age at first sexual intercourse and sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(8):774–780. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Velez-Pastrana MC, Gonzalez-Rodriguez RA, Borges-Hernandez A. Family functioning and early onset of sexual intercourse in Latino adolescents. Adolescence. 2005;40(160):777–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brendgen M, Wanner B, Vitaro F. Peer and teacher effects on the early onset of sexual intercourse. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(11):2070–2075. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.101287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haffner DW. Facing Facts: Sexual Health for America’s Adolescents–The Report of the National Commission on Adolescent Sexual Health. Series Report. New York, NY: Sex Information and Education Council of the US, Inc; 1995. pp. 2–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zangerle M, Rathner G. Age dependence of coping strategies in children and adolescents with diabetes mellitus. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 1997;47(7):240–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu Y, Stanton B, Li X, et al. Protection motivation theory and adolescent drug trafficking: relationship between health motivation and longitudinal risk involvement. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30(2):127–137. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deveaux L, Stanton B, Lunn S, et al. Reduction in human immunodeficiency virus risk among youth in developing countries. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(12):1130–1139. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.12.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.UNAIDS. 2006 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic: A UNAIDS 10th Anniversary Special Edition. Geneve, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanton B. Assessment of relevant cultural considerations is essential for the success of a vaccine. J Health Popul Nutr. 2004;22(3):286–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stanton B, Black M, Feigelman S, et al. Development of a culturally, theoretically and developmentally based survey instrument for assessing risk behaviors among African-American early adolescents living in urban low-income neighborhoods. AIDS Educ Prev. 1995;7(2):160–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murray DM. Design and Analysis of Group-Randomized Trials. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 314–319. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen XG, Fang X, Li X, et al. Stay Away from Tobacco: a pilot trial of a school-based adolescent smoking prevention program in Beijing, China. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(2):227–237. doi: 10.1080/14622200600576479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garcia K, Mann T. From ‘I Wish’ to ‘I Will’: social-cognitive predictors of behavioral intentions. J Health Psychol. 2003;8(3):347–360. doi: 10.1177/13591053030083005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hagger MS, Chatzisarantis N, Biddle SJ. The influence of self-efficacy and past behaviour on the physical activity intentions of young people. J Sports Sci. 2001;19(9):711–725. doi: 10.1080/02640410152475847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jemmott JB, Jemmott LW, Spears H, et al. Self-efficacy, hedonistic expectancies, and condom-use intentions among innercity black adolescent women: a social cognitive approach to AIDS risk behavior. J Adolesc Health. 1992;13(6):512–519. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(92)90016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fortenberry JD. Adolescent sex and the rhetoric of risk. In: Romer D, editor. Reducing Adolescent Risk: Toward an Integrated Approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2003. pp. 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harrison JA, Mullen PD, Green LW. A meta-analysis of studies of the Health Belief Model with adults. Health Educ Res. 1992;7(1):107–116. doi: 10.1093/her/7.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: a decade later. Health Educ Q. 1984;11(1):1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Milne S, Orbell S. Prediction and intervention in health-related behavior: a meta-analytic review of protection motivation theory. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;30(1):106–143. [Google Scholar]