Abstract

Background

Treatment of painful internal snapping hip (coxa saltans) via arthroscopic lengthening or release of the iliopsoas tendon is becoming preferred over open techniques because of the benefits of minimal dissection, the ability to address concomitant intraarticular disorders, and a low complication rate. Persistent snapping after release is uncommon, especially when performed arthroscopically. Reported causes include incomplete release, intraarticular disorders, and incorrect diagnosis. Anatomic variants are not discussed in the orthopaedic literature.

Case Description

We report a case of an 18-year-old softball player with internal snapping hip treated with arthroscopic iliopsoas release in the peripheral compartment. Postoperatively, the athlete continued to have painful snapping. Repeat arthroscopy with a larger capsulotomy revealed a bifid iliopsoas tendon causing refractory internal snapping hip, which resolved after revision arthroscopic release.

Literature Review

Bifid iliopsoas tendon as a cause of persistent snapping of the hip has not been reported in the orthopaedic literature. Prior sonographic and anatomic studies suggest the bifid iliopsoas tendon exists but is uncommon.

Purpose and Clinical Relevance

Recognition that a bifid iliopsoas tendon may be the source of painful internal snapping hip is important to prevent clinical failure of surgical management of the internal snapping hip. The differential diagnosis of failed iliopsoas lengthening surgery should include the consideration of an incompletely lengthened tendon attributable to bifid iliopsoas tendon anatomy. Prevention of this complication includes making a large enough capsulotomy to identify the tendon and to ensure it is not bifid.

Introduction

Internal snapping hip, which is caused by the iliopsoas tendon moving over the femoral head, iliofemoral ligament, iliopectineal ridge, or other structures, can be a painless auditory phenomenon, a simple nuisance associated with mild discomfort, or it can be painful. The snapping most often occurs with hip motion from flexion-external rotation to extension or external rotation/abduction to internal rotation/adduction. It usually can be produced voluntarily by the patient, and occasionally may be reproduced passively by the clinician. The snapping is generally audible and, to a lesser extent, palpable. The prevalence of internal snapping hip is approximately 10% in the general population and may be higher in certain populations, such as in ballet dancers. Uncommonly, pain causes patients to seek medical attention [1, 19, 23].

A painful internal snapping hip infrequently requires surgical intervention. Recent onset usually portends excellent response to activity modification, rest, and stretching of the iliopsoas musculotendinous structure. Steroid injection and oral antiinflammatory medications also are commonly used. The natural history of the refractory, painful snapping hip is that of chronic, progressive symptoms, often affecting athletes who cannot, or will not, avoid activities that produce the snapping [1, 19]. Open tendon lengthening and arthroscopic tenotomy procedures have been described. Treatment of painful internal snapping hip via arthroscopic release is becoming preferred over open techniques because of the benefits of minimal dissection, the ability to address concomitant intraarticular disorders, and a low complication rate [5, 8, 9, 12]. Numerous authors have reported excellent results with arthroscopic iliopsoas tenotomy at 1 to 2 years postoperatively, with no refractory cases of snapping, minimal to no weakness, and a high prevalence of associated intraarticular disorders that can be managed arthroscopically at the same time [2, 3, 10, 11, 21].

Several structures behind the iliopsoas at the level of its musculotendinous junction have been identified as causes of internal snapping hip [15, 19]. Most commonly, the femoral head, the iliofemoral ligament, or the iliopectineal ridge is implicated. The iliacus muscle over the superior pubic rami, iliopsoas bursa, exostoses of the lesser trochanter, and hip disorders, such as labral tears, paralabral cysts, and intraarticular loose bodies, can also be involved—the latter considered intraarticular snapping hip [18]. Bifid iliopsoas tendon as a possible cause of snapping hip has been reported in one dynamic sonographic study [4]. Anatomic variation suggestive of bifid iliopsoas tendon also has been described [14, 20]. We report of a rare complication of arthroscopic release of internal snapping hip attributable to a missed bifid iliopsoas tendon. A second arthroscopic operation was required to identify the bifid tendon, and after release of both tendon heads, the patient had immediate resolution of her pain and snapping.

Case Report

An 18-year-old female softball player was referred for right hip pain, deep in the groin and slightly lateral, which was progressive and associated with audible popping. Although the problem began insidiously, she believed the painful snapping began after sliding into base playing softball approximately 2 years before. She could not pinpoint specific activities or motions that reproduced the sound. She recalled a time when this symptom was not consistently painful. However, by the time of presentation, the snapping was routinely painful with flexion-extension of the hip.

On initial examination, she clearly had audible snapping of the right iliopsoas anteriorly, which she could reproduce voluntarily in the office. This was her greatest source of pain. She also had pain with flexion of the affected hip, with forced internal rotation of the adducted and flexed hip (impingement test), and pain with the labral stress test.

Plain radiographs showed a positive crossing sign, a center edge angle of Wiberg [22] of 42°, and no evidence of coxa profunda [6, 13, 16, 17, 22]. No loose bodies or bone spurs were seen and there was no evidence of degenerative arthritis. MRI revealed a labral tear laterally but did not reveal tendinopathy about the iliopsoas insertion. The differential diagnosis included internal snapping hip and femoroacetabular impingement. Although her symptoms were rather long-standing, physical therapy was recommended as first-line treatment, with additional diagnostic tests to follow should she not improve.

The patient began a 6-week course of iliopsoas and general hip girdle stretching and strengthening with formal physical therapy and a home exercise program. At her reevaluation at 6 weeks, she was not significantly better. Image-guided diagnostic injections were used to confirm the source of her pain. Intraarticular injection with steroid and anesthetic provided incomplete relief, whereas injection of the iliopsoas sheath on a different day provided virtually complete relief. The patient elected to proceed with arthroscopic release of her snapping hip with concomitant evaluation and treatment of her labral tear.

Arthroscopic evaluation of her hip showed very mild chondral softening at the peripheral rim and labral fraying direct laterally, but no clear evidence of symptomatic pincer impingement. She had a labral chondral sulcus anteriorly, which was stable to probing and appeared normal with healthy cartilage. There was mild synovitis anteriorly while the rest of the joint was unremarkable, with no evidence of loose bodies.

The traction was released and the peripheral compartment entered via anterolateral and distal anterolateral portals with the hip in 30° flexion to open the space anteriorly over the hip. A 30° arthroscope was introduced into the anterolateral portal aiming caudally and set on the femoral head-neck junction. Under arthroscopic and fluoroscopic guidance, a distal anterolateral portal was identified approximately 3 cm distally to the standard anterolateral portal. The medial synovial fold was identified. Inspection revealed no pathologic changes, except for some mild synovitis. With the arthroscope pointing toward the anterior capsule, an electrocautery device was introduced from the distal anterolateral portal. An 8-mm transverse capsulotomy was made just lateral to the medial synovial fold and just proximal to the zona orbicularis anteriorly, directly under the iliopsoas tendon. Arthroscopic dissection was performed to identify the iliopsoas tendon (Fig. 1). Arthroscopic iliopsoas tendon release was performed from lateral to medial using electrocautery, taking care to avoid the anterior femoral neurovascular bundle. A complete release was confirmed by observation of the iliacus muscle fibers and noting the 10-mm retraction of the cut tendon ends [21].

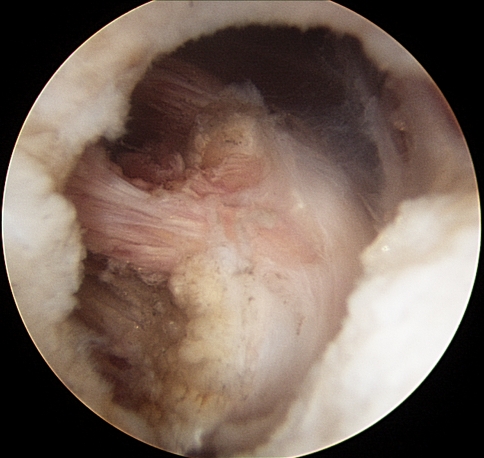

Fig. 1.

An arthroscopic view is shown through a peripheral compartment capsulotomy of the small caliber iliopsoas tendon seen and sectioned at the first arthroscopic iliopsoas release in this patient.

At the time of surgery, the tendon was noted to be smaller than the usual iliopsoas, but otherwise unremarkable. Physical therapy for ROM, stretching, and strengthening as tolerated was begun on Postoperative Day 3, and no weightbearing or motion restrictions were imposed.

On Postoperative Day 12, the patient returned for a scheduled visit and reported random snapping of the right hip, which was painful but not as consistent as before surgical release. Continued physical therapy did not resolve the painful snapping. Three months after her arthroscopic hip surgery, her iliopsoas had returned to full strength; however, her painful snapping hip also had returned to its preoperative state.

After thorough discussion of the risks and benefits of revision arthroscopic surgery to diagnose and correct her internal snapping hip, the patient wished to proceed and underwent revision iliopsoas release 6 months after her first operation. The tendon was approached through a 15-mm capsulotomy just proximal to the zona orbicularis and lateral to the medial synovial fold, again using the technique of Wettstein et al. [21]. This location was the same as that in her index capsulotomy, although larger, and it allowed more extensive observation of the tendon. A bifid iliopsoas tendon with a small upper tendon more anterior and lateral and a bigger tendon posteriorly was identified (Fig. 2). The small tendon was similar in size and location to the tendon sectioned at the first surgery. Thus, the previous capsulotomy and tenotomy had healed. A pencil-tip electrocautery angled at 90° was used to cut both tendons, and dissection allowed for more extensive observation of the tendon. The edges of both tendon heads retracted approximately 15 mm after sectioning (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

An arthroscopic view through a peripheral compartment capsulotomy, just proximal to the zona orbicularis and lateral to the medial synovial fold, shows the bifid iliopsoas tendon at revision, using a larger capsulotomy.

Fig. 3.

An arthroscopic view shows the iliopsoas tendon through the same capsulotomy after sectioning of both tendons of the bifid iliopsoas. The cut and retracted end of the tendon is seen on the right and the iliacus muscle is seen in the left portion through the capsulotomy.

Immediately postoperatively, the patient felt a clear difference and lack of popping in her hip. By 3 months postoperatively, she had not had any snapping of her hip, clinical examination could not reproduce the symptom, and her iliopsoas strength was rapidly returning. At last followup 11 months postoperatively, she continued to report no snapping, popping, or pain in her hip.

Discussion

Bifid iliopsoas as the etiology of coxa saltans was reported by Deslandes et al. [4] after using ultrasound to dynamically evaluate 18 patients with painful internal snapping hips. Two patients were found to have distinct bifid tendons, and in one patient, the anatomic phenomenon was bilateral. Ultrasound showed, in these two cases, snapping was associated with abrupt flipping of the medial tendon head over the lateral tendon proximal to the level of the hip [4].

Traditionally, the iliopsoas tendon is considered to consist of the joining of two muscles—the iliacus and the psoas—into a common tendon with insertion on the lesser trochanter. However, focused anatomic study of 24 cadaver hips by Tatu et al. [20] showed five separate elements combine to make up the iliopsoas tendon. These include the (1) psoas major tendon, (2) medial fibers of the iliacus, which reliably merge with the psoas major tendon, (3) inferior fibers of the iliacus, which also join the main iliopsoas tendon before insertion, (4) lateral fibers of the iliacus, and (5) ilio-infratrochanteric muscular bundle, which together with the lateral fibers attach to the lesser trochanter without tendinous processes. Also, two hips showed complete splitting or a bifid psoas major tendon, which appeared physiologic [20]. Additionally, a recent dynamic sonographic study of 42 hips of healthy volunteers aiming to observe the five components, as described by Tatu et al. [20], also reported one hip with a double or bifid psoas major portion of the iliopsoas tendon [7]. Based on these limited reports, a bifid iliopsoas tendon probably arises from a divide in the psoas major part of the iliopsoas tendon and most likely arises as a constitutional anatomic variant.

The mechanism of bifid iliopsoas tendon causing snapping hip is also ambiguous and may not be solely one mechanism. Although Deslandes et al. [4] implicated the two tendon heads sliding briskly over one another as the cause of snapping, the case we present would suggest otherwise. In our patient, the snapping was palpable directly over the hip, and release of one head did not relieve the snapping. The correlation between release of the second tendon head and resolution of audible, painful snapping was very immediate and convincing in our patient. Direct observation of the bifid tendon through an arthroscope validates its occurrence, however rare.

Review of the literature reveals no cases of persistent snapping after arthroscopic release in the reported 56 cases. This is consistent with the experience of the senior author (MRS) with 12 surgically treated cases, although he is aware of anecdotal cases of persistent snapping after iliopsoas release. As more of these procedures are being performed, it is likely more cases of failed arthroscopic iliopsoas release will be reported.

We report this case of missed bifid tendon to alert the clinician of the possibility of a bifid iliopsoas tendon when treating this entity. For refractory cases of internal snapping hip after surgical intervention, consider this unusual complication. Performing an adequate capsulotomy of at least 10 mm or greater made it possible to see both tendons, and we recommend this length as a minimum capsulotomy when performing an iliopsoas release from the peripheral compartment to ensure the iliopsoas has been appropriately lengthened by sectioning one or both tendons, if two exist.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved or waived approval for the reporting of this case, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Allen WC, Cope R. Coxa saltans: the snapping hip revisited. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3:303–308. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199509000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson SA, Keene JS. Results of arthroscopic iliopsoas tendon release in competitive and recreational athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:2363–2371. doi: 10.1177/0363546508322130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrd JW. Evaluation and management of the snapping iliopsoas tendon. Instr Course Lect. 2006;55:347–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deslandes M, Guillin R, Cardinal E, Hobden R, Bureau NJ. The snapping iliopsoas tendon: new mechanisms using dynamic sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:576–581. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flanum ME, Keene JS, Blankenbaker DG, Desmet AA. Arthroscopic treatment of the painful “internal” snapping hip: results of a new endoscopic technique and imaging protocol. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:770–779. doi: 10.1177/0363546506298580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fredensborg N. The CE angle of normal hips. Acta Orthop Scand. 1976;47:403–405. doi: 10.3109/17453677608988709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guillin R, Cardinal E, Bureau NJ. Sonographic anatomy and dynamic study of the normal iliopsoas musculotendinous junction. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:995–1001. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gruen GS, Scioscia TN, Lowenstein JE. The surgical treatment of internal snapping hip. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:607–613. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300042201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoskins JS, Burd TA, Allen WC. Surgical correction of internal coxa saltans: a 20-year consecutive study. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:998–1001. doi: 10.1177/0363546503260066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ilizaliturri VM, Jr, Chaidez C, Villegas P, Briseno A, Camacho-Galindo J. Prospective randomized study of 2 different techniques for endoscopic iliopsoas tendon release in the treatment of internal snapping hip syndrome. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:159–163. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ilizaliturri VM, Jr, Villalobos FE, Jr, Chaidez PA, Valero FS, Aguilera JM. Internal snapping hip syndrome: treatment by endoscopic release of the iliopsoas tendon. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:1375–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobson T, Allen WC. Surgical correction of the snapping iliopsoas tendon. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18:470–474. doi: 10.1177/036354659001800504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamali AA, Mladenov K, Meyer DC, Martinez A, Beck M, Ganz R, Leunig M. Anteroposterior pelvic radiographs to assess acetabular retroversion: high validity of the “cross-over-sign”. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:758–765. doi: 10.1002/jor.20380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jelev L, Shivarov V, Surchev L. Bilateral variations of the psoas major and the iliacus muscles and presence of an undescribed variant muscle—accessory iliopsoas muscle. Ann Anat. 2005;187:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyons JC, Peterson LF. The snapping iliopsoas tendon. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59:327–329. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61428-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Omeroglu H, Biçimoglu A, Aguş H, Tümer Y. Measurement of center-edge angle in developmental dysplasia of the hip: a comparison of two methods in patients under 20 years of age. Skeletal Radiol. 2002;31:25–29. doi: 10.1007/s002560100402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynolds D, Lucas J, Klaue K. Retroversion of the acetabulum: a cause of hip pain. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:281–288. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.81B2.8291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaberg JE, Harper MC, Allen WC. The snapping hip syndrome. Am J Sports Med. 1984;12:361–365. doi: 10.1177/036354658401200504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah A, Busconi B. Hip, pelvis, and thigh. In: DeLee JC, Drez D Jr, Miller MD, editors. DeLee and Drez’s Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. 3. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tatu L, Parratte B, Vuillier F, Diop M, Monnier G. Descriptive anatomy of the femoral portion of the iliopsoas muscle: anatomical basis of anterior snapping of the hip. Surg Radiol Anat. 2001;23:371–374. doi: 10.1007/s00276-001-0371-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wettstein M, Jung J, Dienst M. Arthroscopic psoas tenotomy. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:907e1–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Wiberg G. Studies on dysplastic acetabula and congenital subluxation of the hip joint: with special reference to the complication of osteo-arthritis. Acta Chir Scand. 1939;83(suppl 58):1–135. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winston P, Awan R, Cassidy JD, Bleakney RK. Clinical examination and ultrasound of self-reported snapping hip syndrome in elite ballet dancers. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:118–126. doi: 10.1177/0363546506293703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]