Abstract

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of a trained district nurse individually prescribing a home based exercise programme to reduce falls and injuries in elderly people and to estimate the cost effectiveness of the programme.

Design

Randomised controlled trial with one year's follow up.

Setting

Community health service at a New Zealand hospital.

Participants

240 women and men aged 75 years and older.

Intervention

121 participants received the exercise programme (exercise group) and 119 received usual care (control group); 90% (211 of 233) completed the trial.

Main outcome measures

Number of falls, number of injuries resulting from falls, costs of implementing the programme, and hospital costs as a result of falls.

Results

Falls were reduced by 46% (incidence rate ratio 0.54, 95% confidence interval 0.32 to 0.90). Five hospital admissions were due to injuries caused by falls in the control group and none in the exercise group. The programme cost $NZ1803 (£523) (at 1998 prices) per fall prevented for delivering the programme and $NZ155 per fall prevented when hospital costs averted were considered.

Conclusion

A home exercise programme, previously shown to be successful when delivered by a physiotherapist, was also effective in reducing falls when delivered by a trained nurse from within a home health service. Serious injuries and hospital admissions due to falls were also reduced. The programme was cost effective in participants aged 80 years and older compared with younger participants.

What is already known on this topic

Falls are the costliest type of injury among elderly people, and the healthcare costs increase with frequency of falls and severity of injuries

An exercise programme delivered by a physiotherapist was successful in reducing falls and moderate injuries in elderly people

What this study adds

An exercise programme to prevent falls in elderly people worked well when delivered by a district nurse from a home health service in the suburbs of a large city

Researchers, public health administrators, and health practitioners can work together to benefit elderly people in the community

Introduction

The frequency, serious consequences, and healthcare costs of falls in elderly people are well documented.1–5 Randomised controlled trials of single and multiple interventions have shown that falls can be reduced.6 The effectiveness of these programmes and their costs in usual healthcare settings have not been reported. Our research group developed a home based programme of strength and balance retraining, which was effective in reducing falls and falls resulting in moderate injuries when delivered by a research physiotherapist to a group of women aged 80 years and older living in the community.7,8

We have now tested in two healthcare settings the effectiveness and efficiency of the programme when delivered by health professionals previously untrained in prescribing exercise. This first paper reports on the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of the exercise programme in both men and women aged 75 years and older when delivered from an established home health service by a trained district nurse.

Participants and methods

Participant recruitment

We identified potential participants aged 75 years and older from computerised registers at 17 general practices (30 doctors) in the West Auckland area, New Zealand. These patients received a letter from their doctor inviting them to take part in the study. The criteria for exclusion were inability to walk around own residence, receiving physiotherapy at the time of recruitment, or not able to understand the requirements of the trial. Recruiting took place over a six month period in 1998.

Trial design

This was a randomised controlled trial with one year's follow up. The sample size calculation was based on the proportion of elderly people who fell once or more in a 12 month prospective community study,9 an expected reduction from 0.50 to 0.30, and 20% allowance for dropouts. Our study was approved by the ethics committee of the Health Funding Authority Northern Division.

Potential participants were informed there was an equal chance they would receive the exercise programme or act as a control. After written informed consent was obtained and baseline assessments (personal characteristics, health, and function) completed at home by an independent assessor, we randomised 240 participants: 121 to the exercise programme (exercise group) and 119 to usual care (control group). A statistician developed the schedule for group allocation using random numbers, and this was held at another centre. Participants were then informed of their group allocation by telephone.

Intervention

A district nurse who had had no previous experience in prescribing exercise attended a one week training course run by the physiotherapist from the research group. A series of site visits and regular telephone calls were made by the supervising physiotherapist to assess and ensure quality control.

The implementation of the exercise programme was run from a home health service based in a geriatric assessment and rehabilitation hospital. The nurse delivered the exercise programme in conjunction with her work as a district nurse. The intervention consisted of a set of muscle strengthening and balance retraining exercises that progressed in difficulty, and a walking plan.7 The programme was individually prescribed during five home visits by the instructor at weeks 1, 2, 4, and 8, with a booster visit after six months. The number of repetitions of the exercise and the number of ankle cuff weights (1, 2, and 3 kg; range 0 to 6 kg) used for muscle strengthening were increased at each visit as appropriate. Participants were expected to exercise at least three times a week (about 30 minutes per session) and to walk at least twice a week for a year. Compliance was monitored with postcard calendars similar to those used to monitor falls. For the months when no home visit was scheduled the nurse telephoned participants to maintain motivation and discuss any problems.

Measurement of falls and injuries and health status

Falls were defined as “unintentionally coming to rest on the ground, floor, or other lower level.”10 Falls were monitored for one year in both groups by asking participants to return preaddressed and prepaid postcard calendars for each month. The independent assessor telephoned participants to record the circumstances of the falls and any injuries or resource use as a result of the falls. She remained blind to group allocation.

Fall events were classified as resulting in “serious” injury if the fall resulted in a fracture, admissions to hospital with an injury, or stitches were required, “moderate” injury if bruising, sprains, cuts, abrasions, or reduction in physical function for at least three days resulted or if the participant sought medical help, and “no” injury. The circumstances of “serious” injuries were confirmed from hospital and general practice records. The investigator classifying fall events remained blind to group allocation. The SF-12 questionnaire was used to estimate self perceived health status at entry to the trial.11

Methods used in economic evaluation

We used cost effectiveness analysis to enable comparisons of programme efficiency with other interventions for preventing falls. We considered costs from the societal perspective because of the broad nature of the problems caused by falls, and we reported them in New Zealand dollars according to 1998 prices, exclusive of government goods and services tax. The control group was used as the comparator for the analysis. We measured cost effectiveness as the incremental cost of introducing the programme per fall event prevented during the trial.

The concept of opportunity costs was kept in mind so that all relevant costs—that is, those resources that could have been employed elsewhere—could be included. We performed one way sensitivity analyses.

Costs of the exercise programme

We focused on the costs of implementing the exercise programme. Although there were costs associated with developing the programme, these costs were incurred before the trial and were not incremental to this programme. We did not include the research costs of evaluating the programme.

Costs for implementing the programme were obtained from trial records and the financial records of the hospital and research group, using actual costs when available. We did not include the costs of recruiting the exercise instructor because existing staff in an organisation may deliver the exercise programme. We did not put a value on the time participants spent exercising or walking as it was assumed these activities were done in their leisure time; the opportunity cost was taken to be zero. Half of the recruiting costs for this first paper were allocated to implementation of the programme because half those recruited were randomised to the control group and did not receive the exercise programme. We estimated overhead costs as 21.9% of observed resource use because this was the sector average reported for all hospital and health services in New Zealand for operating costs and overhead expenses in 1998-9.12

Resource use and healthcare costs resulting from falls

In a previous trial of the exercise programme we found that 90% of the estimated healthcare costs resulting from falls were for hospital inpatient and associated health service costs.13 A further 4% were for those services used as a result of serious injuries and were not provided by the local hospital. Estimated costs for injuries we classified as moderate made up the remaining 6% of total healthcare costs resulting from falls.

Therefore to estimate the costs resulting from fall injuries in this trial we restricted measurement to actual costs incurred by the hospitals admitting participants as a result of a fall. For each fall event these included costs for emergency room, theatre, ward, physician, radiology, laboratory, and blood services, pharmacy products, hospital social workers, physiotherapy, and occupational therapy. Each hospital cost item included overhead costs (cleaning, heating, lighting, telephone, laundry, food, administration, orderlies, computing, and depreciation on equipment) calculated by the accounting convention at each hospital.

Costs for hospital items were identified as being associated with a fall by matching the date of the cost record with the date of a trial record for a fall event. Cost records were included only if the department and product description indicated that the item was likely to have been used as a result of the fall.

Calculation of cost effectiveness ratios

We measured cost effectiveness as the ratio ΔC: ΔE, where ΔC (incremental cost) was the change in resource use resulting from the exercise programme.14 This was taken as the total cost of implementing the exercise programme because the control group did not receive an intervention, plus the difference in hospital costs resulting from falls during the trial for the two groups. We planned to include estimates for hospital costs as a result of falls in ΔC only if these costs or the number of serious injuries proved to be significantly different between the two groups.

We measured ΔE (incremental effect) as the difference between the number of falls and the number of falls resulting in moderate or serious injury in the two groups. We considered the actual number of fall events and a standardised measure, fall events per 100 person years. This measure takes into account the variable follow up times for individuals in the trial.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out one way sensitivity analyses by calculating cost effectiveness ratios. We did this with a range of estimates of cost items for implementing the exercise programme to investigate robustness of the ratios to different delivery scenarios. We used the 125th centile of the total, the total, and the 75th centile of the total costs for implementation when calculating the cost effectiveness ratios to account for the possibility of different cost conditions when replicating the programme in different settings. Training and supervision of the exercise programme could be carried out from the same rather than a distant centre. We therefore calculated cost effectiveness ratios excluding travel costs between centres and the associated accommodation costs. We used the 125th centile of the costs for the home visits to give an indication of costs for delivering the programme in a more spread out community. The ankle cuff weights we used were manufactured cheaply in a non-commercial environment. Participants may well have been encouraged to use more weights. Therefore in the sensitivity analyses we used four times the actual cost of the weights. The home health service could not identify any extra overhead costs as a result of running the exercise programme. We included this scenario in the sensitivity analyses. For this part of our study we also calculated cost effectiveness ratios for those aged 80 years and older by apportioning the costs of the programme (on a pro rata basis) between the 75 to 79 year olds and those aged 80 and older, and using the number of fall events prevented in those aged 80 years and older.

Time horizon

Assuming that participants keep exercising, the benefits of the exercise programme would extend past the time individuals participated in the trial, but the extent of this benefit and longer term compliance rates are uncertain. We calculated cost effectiveness ratios for the duration of the trial only.

Statistical analysis

We analysed data on an intention to treat basis with Stata Release 6 and SPSS 6.1.1. No deviations occurred from random allocation—all those who were allocated to the exercise group received at least one home visit, and no participants in the control group received the programme. The mean (SD) time between baseline assessment and the first home visit was 11.5 (6.1) days.

We compared the numbers of falls in the two groups using negative binomial regression models.15 These models estimate the number of occurrences of an event when the event has Poisson variation with overdispersion, and they allow for variable follow up times for participants and investigation of the treatment and interaction effects. We used Student's t test to compare means and Fisher's exact test or c2 test to compare proportions between groups.

Results

Trial participants and follow up

The mean (SD) age of participants was 80.9 (4.2) years, and ages ranged from 75 to 95 years. Table 1 shows the characteristics of participants at entry to the trial.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants at entry to trial. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Control group (n=119) | Exercise group (n=121) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 81.1 (4.5) | 80.8 (3.8) |

| Aged ⩾80 years | 66 (55) | 60 (50) |

| Men | 39 (33) | 39 (32) |

| Living arrangements: | ||

| Two or more participants in one home | 31 (26) | 26 (21) |

| Living alone | 60 (50) | 66 (55) |

| Living in nursing home | — | 1 (1) |

| Fallen in previous year | 45 (38) | 44 (36) |

| Medical conditions: | ||

| Parkinson's disease | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Stroke | 21 (18) | 13 (11) |

| Hip fracture | 2 (2) | 5 (4) |

| Knee or hip pain, or both | 35 (29) | 41 (34) |

| Mean (SD) scores on SF-12*: | ||

| Physical component | 39.1 (11.7) | 40.1 (10.9) |

| Mental component | 54.5 (7.9) | 54.9 (8.2) |

| Mean (SD) No of current prescribed drugs | 3.1 (2.4) | 2.9 (2.3) |

| Taking psychotropic drugs | 25 (21) | 21 (17) |

| Home assistance: | ||

| Cleaning | 33 (28) | 32 (26) |

| Showering | 4 (3) | — |

| Meals on wheels | 14 (12) | 19 (16) |

Score ranges 0–100, lower scores indicate poorer health.

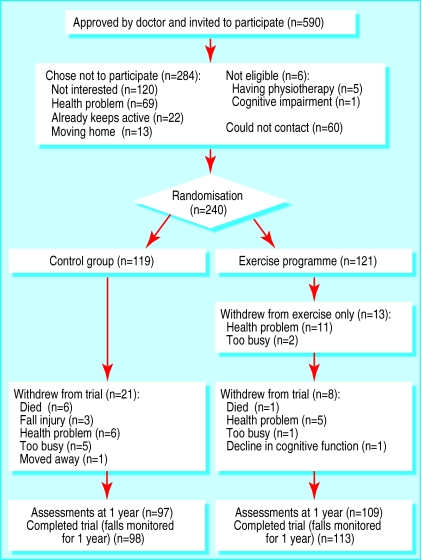

The figure shows the flow of participants through the trial. We have not reported the results of assessments repeated after one year. More participants from the exercise group than the control group completed the trial (113 v 98, difference 11%, 95% confidence interval 3% to 19%). Those who died or withdrew were more likely to have had a fall in the year before the trial and took more drugs at entry to the trial (mean (SD) number 4.3 (2.4) v 2.8 (2.3), P=0.002).

Overall, 43% (49 of 113) of participants who completed the trial carried out their prescribed exercise programme three or more times a week, 72% (n=81) carried it out at least twice a week, and 71% (n=80) walked at least twice a week during the year's follow up.

Falls and fall related injuries

Table 2 shows the actual and standardised numbers of falls and the numbers of falls resulting in injuries during the trial. We found a 46% reduction in the number of falls during the trial for the exercise group compared with the control group (incidence rate ratio from negative binomial regression model 0.54, 95% confidence interval 0.32 to 0.90). The number of falls was reduced in those aged 80 years and older (81 v 43 falls for control and exercise groups, respectively; P=0.007), and there was no difference in participants aged 75 to 79 years. One participant did fall while exercising according to instructions.

Table 2.

Incidence of fall events and follow up times

| Control group (n=119) | Exercise group (n=121) | |

|---|---|---|

| No of falls | 109 | 80* |

| Falls per 100 person years | 100.6 | 68.5 |

| No of injurious falls: | 49 | 42 |

| Serious | 9 | 2† |

| Moderate | 40 | 40 |

| Injurious falls per 100 person years | 45.2 | 36.0 |

| No (%) of falls for which medical care sought | 26 (24) | 18 (23) |

| Mean (SD) follow up time (months) | 10.9 (2.7) | 11.6 (1.9)‡ |

| Total follow up time (person years) | 108.33 | 116.79 |

Incidence rate ratio 0.54 (95% confidence interval 0.32 to 0.90), P=0.019.

Fisher's exact test, P=0.033.

Student's t test, P=0.028.

Fewer participants in the exercise than control group had a serious injury resulting from a fall during the trial (2 v 9, relative risk 4.6, 95% confidence interval 1.0 to 20.7). Nine falls resulted in fractures (five required hospital admission) and three in lacerations requiring sutures. The same numbers of moderate injuries occurred in the two groups.

Economic evaluation

Costs of implementing the exercise programme

Table 3 shows the values for the cost items for implementing the exercise programme. The programme cost $NZ52 229 ($NZ432 per person) to deliver to the 121 participants for one year.

Table 3.

Incremental costs of implementing exercise programme

| Cost item | Resource use | Unit cost ($NZ) | Total cost ($NZ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training course* | |||

| Exercise nurse: | |||

| Time (hours) | 40 | 17.73 | 709 |

| Travel to Dunedin | 1 return flight, shuttles | 696.25 | 696 |

| Accommodation (nights)† | 4 | 125.00 | 500 |

| Physiotherapist (hours) | 37.5 | 19.17 | 180 |

| Materials | Folder | 28.21 | 28 |

| Transport in Dunedin | Visits to 15 clients | 0.62 per km | 28 |

| Recruitment, programme prescription, and follow up | |||

| Exercise nurse time (hours) | 1239 | Average 18.43 | 22 833 |

| Exercise nurse transport (km) | 6250 | 0.62 | 3875 |

| Doctors' time‡ | 30 doctors, 0.25 hours each | 40.39 | 606 |

| General practice staff time‡ | 17 practices, 0.75 hours each | 13.11 | 111 |

| Typing lists and letters (hours)‡ | 51 | 15.64 | 399 |

| Pager (months) | 18 | 27.00 | 486 |

| Postage (stamps) | 580 | 0.40 | 232 |

| Stationery and photocopying | Paper, envelopes | 0.10 | 275 |

| Telephone calls | 1619 | 0.10 | 162 |

| Ankle cuff weights | 177, courier | Average 21.27 | 3764 |

| Instruction booklets | 121 folders, paper | 7.50 | 908 |

| Supervision of programme | |||

| Physiotherapist: | |||

| Time (hours) | 43.5 | 19.17 | 834 |

| Travel to Auckland | 3 return flights, shuttles | Average 545.67 | 1637 |

| Accommodation (nights)† | 5 | Average 137.40 | 687 |

| Telephone calls | 44 | Average 3.34 | 147 |

| Exercise nurse: | |||

| Time (hours) | 210 | 17.73 | 3720 |

| Telephone calls | 26 | Average 3.96 | 103 |

| Overhead costs§ | 21.85% of resource use | 9378 | |

| Total cost | 52 299 | ||

| Average cost per participant for 1 year programme | 432 | ||

Average exchange rate in 1998, $NZ1.00=32p.

Costs for training course were divided equally among the four nurses at course (three nurses were from trial reported in accompanying paper).

Includes food allowance.

Half these costs were used because control group participants were also recruited.Time spent by doctors was valued using weighted average price in 1998 for consultation “person over 65 without card”; item used in calculation of consumers price index.

Office accommodation, financial and administration services, depreciation on equipment.

Resource use resulting from falls

Overall, 44 of 189 (23%) falls resulted in the use of healthcare services (table 2). Medical care was sought for more falls in the control than exercise group, but the difference was not significant. The five people admitted to hospital were all from the control group and were aged over 80 years. The actual cost of these admissions and therefore the hospital cost averted by the exercise programme was $NZ47 818.

Cost effectiveness measures

The incremental cost per fall prevented was $NZ1803 (table 4). Estimates for the cost per fall with an injury prevented ranged from $NZ5603 to $NZ9437 for the different cost scenarios. When we included cost savings from hospital admissions in the calculation of cost effectiveness ratios, the estimates of the ratios were considerably lower (some indicated cost savings) than for those calculated using the exercise programme costs alone.

Table 4.

Cost effectiveness ratios and sensitivity analysis: incremental cost per fall event prevented in exercise group compared with control group

| Cost scenario | Exercise programme costs only ($NZ) | Including hospital costs averted* ($NZ) |

|---|---|---|

| Cost per fall prevented: | ||

| Total cost of programme | 1803 | 155 |

| 125th centile total cost of programme | 2254 | 605 |

| 75th centile total cost of programme | 1353 | (296) |

| Training, supervision in same centre | 1639 | (10) |

| 125th centile cost of home visits | 2084 | 435 |

| × 4 ankle cuff weights | 2278 | 629 |

| No extra overhead costs | 1480 | (169) |

| Aged ⩾80 years† | 682 | (576) |

| Adjusted cost per fall prevented‡: | ||

| Total cost of programme | 1629 | 140 |

| 125th centile total cost of programme | 2037 | 547 |

| 75th centile total cost of programme | 1222 | (268) |

| Training, supervision in same centre | 1481 | (9) |

| 125th centile cost of home visits | 1883 | 393 |

| × 4 ankle cuff weights | 2058 | 568 |

| No extra overhead costs | 1337 | (153) |

| Aged ⩾80 years† | 422 | (356) |

| Cost per injurious fall prevented: | ||

| Total cost of programme | 7471 | 640 |

| 125th centile total cost of programme | 9339 | 2508 |

| 75th centile total cost of programme | 5603 | (1228) |

| Training, supervision in same centre | 6791 | (41) |

| 125th centile cost of home visits | 8634 | 1802 |

| × 4 ankle cuff weights | 9437 | 2606 |

| No extra overhead costs | 6132 | (700) |

| Aged ⩾80 years† | 1852 | (1563) |

| Adjusted cost per injurious fall prevented‡: | ||

| Total cost of programme | 5685 | 487 |

| 125th centile total cost of programme | 7106 | 1908 |

| 75th centile total cost of programme | 4263 | (934) |

| Training, supervision in same centre | 5167 | (31) |

| 125th centile cost of home visits | 6569 | 1371 |

| × 4 ankle cuff weights | 7180 | 1983 |

| No extra overhead costs | 4665 | (532) |

| Aged ⩾80 years† | 1195 | (1009) |

Negative values, shown in brackets, indicate cost savings.

Average exchange rate in 1998 New Zealand $NZ1.00 =32p.

Estimates of ratios incorporate both incremental cost of implementing programme and hospital costs averted owing to fewer falls resulting in hospital admissions in exercise group compared with control group.

Calculated using total cost of programme divided pro rata between participants aged ⩾80 years (n=60) and less than 80 years (n=61) in exercise group and fall events prevented in those aged ⩾80 years.

Calculated using fall events per 100 person years to adjust for variable follow up times for individuals in trial.

The exercise programme was considerably more cost effective for those aged 80 years and older than for the total sample. Estimates for cost effectiveness ratios for implementing the exercise programme in this age group were $NZ682 per fall prevented and $NZ1852 per injurious fall prevented. When hospital costs averted and costs for implementation were both used in the calculations of the cost effectiveness ratios, the net cost of the programme for those aged 80 years and older resulted in cost savings of $NZ576 per fall event prevented and $NZ1563 per injurious fall event prevented.

Discussion

An individually tailored exercise programme delivered at home can prevent falls. The programme can be delivered safely by a district nurse and is suitable for both men and women. Academic researchers are sometimes perceived as being remote from the day to day realities of delivering health care, and the results of research do not always reach those who could benefit.16 Our trial is an example of effective collaboration between researchers, public health professionals, and administrators, resulting in health benefits to elderly people in the community.

Subgroup analysis showed that the programme was effective in those aged 80 years and older but not in those aged 75 to 79 years. Although our trial was not designed to test this, the finding is consistent with our previous finding that falls were not reduced by the exercise programme in a sample of women and men aged 65 years and older who were taking psychotropic drugs.17 The programme may be more effective in frailer, elderly people than younger, fitter people because the exercises increase strength and balance above the critical threshold necessary for stability.

As with all age groups only a proportion will be prepared to join an exercise programme, but as shown by the characteristics at trial entry, the participants represented a general population of this age group. Follow up was good, although more people withdrew from the control than exercise group. This may have biased the results against effectiveness because those who withdrew were at a higher risk of falling.

The exercise group had the same number of moderate injuries but fewer serious injuries as a result of a fall than the control group. Injuries resulting in hospital admissions are costly, and reducing injuries such as fractures and lacerations in our trial resulted in cost savings.

We used hospital admission costs as a result of a fall injury as our estimate of the consequences of the exercise programme. We found the same number of moderate injuries resulting from falls in both groups. We also knew from an earlier study that the remaining medical and personal costs resulting from falls account for only 10% of the total healthcare costs for falls.

We estimated the cost of implementing the exercise programme to serve as a guide for the cost of replicating the programme in the future. Costs may well differ in a different setting or be influenced by the reporting expectations of those who fund the programme, by the efficiency and experience level of the instructor, and by the age group enrolled. For example, some of the costs of implementing the programme would not be incurred if the programme was run in one urban area (see table 4 for the same centre scenario).

Comparison with other interventions for preventing falls

Effectiveness

Implementing this single intervention proved as or more effective in reducing falls than other successful community based programmes reported in the literature.18–21 Withdrawing psychotropic drugs reduced the risk of falls by 66%, but there were difficulties in recruiting participants to the trial and a high dropout rate.16 Other community based interventions have not proved successful in reducing falls.22–25

Economic efficiency

Little information is available at present for comparing the efficiency of the exercise programme with other interventions aimed at preventing falls. We found only two publications reporting the cost effectiveness of implementing an intervention for preventing falls in the community.26,27 The exercise programme in our trial was more cost effective than a home based, targeted, multifactorial intervention (total intervention implementation costs per fall prevented $US2668 (at 1993 prices; around $NZ6141) versus $NZ1803, although this figure did include “developmental” costs for the programme). A home assessment and modification programme, successful in reducing falls in those with a history of a fall in the previous year, cost an average of $A4986 (at 1997 prices; $NZ1.00=$A0.89 in 1997) per fall prevented. This cost effectiveness ratio incorporated all healthcare resource use during the trial.27

Some other studies have shown reduced healthcare use or cost savings occurred as a result of a programme to prevent falls.19,28 Benefits may result from early identification of health problems, earlier referrals, or physically fitter people spending a shorter time in hospital.

Conclusions

In our previous trials, the exercise programme was delivered by a physiotherapist.7,17 We conclude that a trained district nurse is also an appropriate person to implement the programme. Implementation of the programme worked well when run from an established home health service and required the minimum of input from other staff. We recommend that nurses are trained and supervised by a suitably qualified physiotherapist. Although supervision in the same centre would be less time consuming and less costly, long distance supervision combining site visits and telephone contact worked well. This trial studied one trained nurse in one health service delivering a home based exercise programme. Our second pragmatic trial studies practice nurses trained to deliver the programme from general practices.29

Figure.

Flow of participants through trial

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants; the West Auckland doctors and their receptionists; Gaye McKay, exercise instructor; Tania Roebuck, independent assessor; Lenore Armstrong, research nurse; Beth Cozens, manager, home health services; Margaret Devlin, Safe Waitakere; Toni Gibbins, clinical analyst; Peter Herbison, statistician; Molly Kavet, clinical information analyst; Professor Murray Tilyard and the General Practice Research Unit; Sheila Williams, statistician; and Gail Woollacott, locality manager.

Footnotes

Funding: This project was funded by the Health Funding Authority Northern Division, New Zealand. MCR and MMG were part funded by Accident Rehabilitation and Compensation Insurance Corporation of New Zealand. MMG was also part funded by a Trustbank Otago Community Trust medical research fellowship.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Hudes ES. Risk factors for injurious falls: a prospective study. J Gerontol Med Sci. 1991;46:164–170. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.5.m164. M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tinetti ME, Mendes de Leon CF, Doucette JT, Baker DI. Fear of falling and fall-related efficacy in relationship to functioning among community-living elders. J Gerontol Med Sci. 1994;49:140–147. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.3.m140. M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tinetti ME, Williams CS. Falls, injuries due to falls, and the risk of admission to a nursing home. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1279–1284. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710303371806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiel DP, O'Sullivan P, Teno JM, Mor V. Health-care utilization and functional status in the aged following a fall. Med Care. 1991;29:221–228. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199103000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rizzo JA, Friedkin R, Williams CS, Nabors J, Acampora D, Tinetti ME. Health care utilization and costs in a Medicare population by fall status. Med Care. 1998;36:1174–1188. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199808000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gardner MM, Robertson MC, Campbell AJ. Exercise in preventing falls and fall related injuries in older people: a review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2000;34:7–17. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.34.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, Norton RN, Tilyard MW, Buchner DM. Randomised controlled trial of a general practice programme of home based exercise to prevent falls in elderly women. BMJ. 1997;315:1065–1069. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, Norton RN, Buchner DM. Falls prevention over 2 years: a randomized controlled trial in women 80 years and older. Age Ageing. 1999;28:513–518. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.6.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell AJ, Borrie MJ, Spears GF. Risk factors for falls in a community-based prospective study of people 70 years and older. J Gerontol Med Sci. 1989;44:112–117. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.4.m112. M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchner DM, Hornbrook MC, Kutner NG, Tinetti ME, Ory MG, Mulrow CD, et al. Development of the common data base for the FICSIT trials. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:297–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenkinson C, Layte R, Jenkinson D, Lawrence K, Petersen S, Paice C, et al. A shorter form health survey: can the SF-12 replicate results from the SF-36 in longitudinal studies? J Public Health Med. 1997;19:179–186. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a024606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crown Company Monitoring Advisory Unit. Hospital and health services performance reporting measures. Quarter ended 30 Sep 1999.

- 13.Robertson MC, Devlin N, Scuffham P, Gardner MM, Buchner DM, Campbell AJ. Economic evaluation of a community based exercise programme to prevent falls. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001 (in press.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Drummond MF, O'Brien B, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 6.0. College Station, TX: Stata; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris M, Hutchinson J. Practice makes perfect: developing public health practice. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:683–684. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.11.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, Norton RN, Buchner DM. Psychotropic medication withdrawal and a home-based exercise program to prevent falls: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:850–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb03843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tinetti ME, Baker DI, McAvay G, Claus EB, Garrett P, Gottschalk M, et al. A multifactorial intervention to reduce the risk of falling among elderly people living in the community. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:821–827. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409293311301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buchner DM, Cress ME, de Lateur BJ, Esselman PC, Margherita AJ, Price R, et al. The effect of strength and endurance training on gait, balance, fall risk, and health services use in community-living older adults. J Gerontol Med Sci. 1997;52A:218–224. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.4.m218. M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolf SL, Barnhart HX, Kutner NG, McNeely E, Coogler C, Xu T, et al. Reducing frailty and falls in older persons: an investigation of Tai Chi and computerized balance training. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:489–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cumming RG, Thomas M, Szonyi G, Salkeld G, O'Neill E, Westbury C, et al. Home visits by an occupational therapist for assessment and modification of environmental hazards: a randomized trial of falls prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:1397–1402. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lord SR, Ward JA, Williams P, Strudwick M. The effect of a 12-month exercise trial on balance, strength, and falls in older women: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:1198–1206. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb07394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McMurdo ME, Mole PA, Paterson CR. Controlled trial of weight bearing exercise in older women in relation to bone density and falls. BMJ. 1997;314:569. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7080.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacRae PG, Feltner ME, Reinsch S. A 1-year exercise program for older women: effects on falls, injuries, and physical performance. J Aging Physical Activity. 1994;2:127–142. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reinsch S, MacRae P, Lachenbruch PA, Tobis JS. Attempts to prevent falls and injury: a prospective community study. Gerontologist. 1992;32:450–456. doi: 10.1093/geront/32.4.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rizzo JA, Baker DI, McAvay G, Tinetti ME. The cost-effectiveness of a multifactorial targeted prevention program for falls among community elderly persons. Med Care. 1996;34:954–969. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199609000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salkeld G, Cumming RG, O'Neill E, Thomas M, Szonyi G, Westbury C. The cost effectiveness of a home hazard reduction program to reduce falls among older persons. Aust NZ J Public Health. 2000;24:265–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2000.tb01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubenstein LZ, Robbins AS, Josephson KR, Schulman BL, Osterweil D. The value of assessing falls in an elderly population. A randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:308–316. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-4-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robertson MC, Gardner MM, Devlin N, McGee R, Campbell AJ. Effectiveness and economic evaluation of a nurse delivered home exercise programme to prevent falls. 2: Controlled trial in multiple centres. BMJ. 2001;322:701–704. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7288.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]