Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the melanoma imaging properties of a novel 67Ga-labeled lactam bridge-cyclized alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH) peptide. A lactam bridge-cyclized α-MSH peptide, DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH {DOTA-Gly-Glu-c[Lys-Nle-Glu-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-Gly-Arg-Pro-Val-Asp]}, was synthesized and radiolabeled with 67Ga. The melanoma targeting and pharmacokinetic properties of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH were determined in B16/F1 flank primary melanoma-bearing and B16/F10 pulmonary metastatic melanoma-bearing C57 mice. Flank primary melanoma and pulmonary metastatic melanoma imaging were performed by small animal single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)/CT using 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH as an imaging probe. 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was readily prepared with greater than 95% radiolabeling yield. 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH exhibited substantial tumor uptake (12.93 ± 1.63 %ID/g at 2 h post-injection) and prolonged tumor retention (5.02 ± 1.35 %ID/g at 24 h post-injection) in B16/F1 melanoma-bearing C57 mice. The uptake values for non-target organs were generally low (<0.30 %ID/g) except for the kidneys at 2, 4 and 24 h post-injection. 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH exhibited significantly (p<0.05) higher uptakes (1.44 ± 0.75 %ID/g at 2 h post-injection and 1.49 ± 0.69 %ID/g at 4 h post-injection) in metastatic melanoma-bearing lung than those in normal lung (0.15 ± 0.10 %ID/g and 0.17 ± 0.11 %ID/g at 2 and 4 h post-injection, respectively). Both flank primary B16/F1 melanoma and B16/F10 pulmonary melanoma metastases were clearly visualized by SPECT/CT using 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH as an imaging probe 2 h post-injection. 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH exhibited favorable melanoma targeting and imaging properties, highlighting its potential as an effective imaging probe for early detection of primary and metastatic melanoma.

Keywords: Primary and metastatic melanoma detection, 67Ga-labeled, alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone peptide, melanocortin-1 receptor

INTRODUCTION

G protein-coupled melanocortin-1 (MC1) receptors are distinct molecular targets for developing melanoma-specific peptide radiopharmaceuticals due to their over-expression on human and mouse melanoma cells (1–5). Alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH) peptides can specifically target the MC1 receptors with diagnostic and therapeutic radionuclides through specific peptide-receptor interaction for melanoma imaging and therapy (6–18). Recently, we have reported a novel class of 111In-labeled lactam bridge-cyclized α-MSH peptides as effective imaging probes for melanoma detection (19, 20). Unique lactam bridge-cyclization made the radiolabeled peptides stable both in vitro and in vivo. Both primary melanoma and pulmonary melanoma metastases were clearly visualized by small animal SPECT/CT using 111In-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH {111In-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid-c[Lys-Nle-Glu-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-Gly-Arg-Pro-Val-Asp]} as an imaging agent (19, 20), highlighting the potential applications of radiolabeled lactam bridge-cyclized α-MSH peptides as effective diagnostic and therapeutic agents for melanoma.

Gallium-67 and Gallium-68 are suitable SPECT and positron emission tomography (PET) radiometals with desirable radiophysical properties (21, 22). Gallium-67 has a half-life of 78.3 h and decays with three gamma-emissions at 93 keV (38% abundance), 185 keV (24% abundance) and 300 keV (16% abundance) that are suitable for SPECT imaging (23, 24). Moreover, 67Ga is also a potential therapeutic radiometal due to its emissions of Auger and conversion electrons (25). Gallium-67 is a cyclotron-produced radionuclide (68Zn(p, 2n)67Ga) and is commercially available. The relatively long half-life of 67Ga (78.3 h) makes it feasible to ship to the hospital or research institution after the production at the cyclotron site. Gallium-68 is an attractive radionuclide for PET imaging due to its 89% positron emission (maximum energy of 1.92 MeV). Gallium-68 has a half-life of 68 min and can be easily obtained via an in-house commercial 68Ge-68Ga generator, making the production of 68Ga independent of an onsite dedicated cyclotron (26). The 68-min half-life of 68Ga allows the generator elution every 3–4 h which is ideal for several clinical studies in patients in one day. The half-life of the parent 68Ge is 260.8 days, which makes the shelf-life of a 68Ge/68Ga generator greater than one year. Importantly, 67Ga and 68Ga can be easily conjugated by the DOTA-peptides, which makes the kit formulation possible and facilitates the clinical use of gallium radiopharmaceuticals for SPECT and PET imaging.

Our laboratory has been interested in developing radiometal-labeled lactam bridge-cyclized α-MSH peptides for melanoma SPECT imaging. Hence, we prepared 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH and examined its melanoma imaging properties in primary and pulmonary metastatic melanoma models to determine whether it could be used as an effective SPECT agent for both primary and metastatic melanoma detection in this study. The biodistribution and melanoma imaging properties of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH were determined in B16/F1 flank primary melanoma-bearing C57 mice and B16/F10 pulmonary metastatic melanoma-bearing C57 mice. The effect of L-lysine co-injection in reducing the renal uptake of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was examined in B16/F1 melanoma-bearing C57 mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and Reagents

Amino acids and resin were purchased from Advanced ChemTech Inc. (Louisville, KY) and Novabiochem (San Diego, CA). DOTA-tri-t-butyl ester was purchased from Macrocyclics Inc. (Richardson, TX). 67GaCl3 was purchased from MDS Nordion, Inc. (Vancouver, Canada). All other chemicals used in this study were purchased from Thermo Fischer Scientific (Waltham, MA) and used without further purification. B16/F1 and B16/F10 murine melanoma cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA).

Complexation of the Peptide with 67Ga

DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was synthesized as described previously (19) and identified by mass spectrometry. DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was radiolabeled with 67Ga using a 0.5 M NH4OAc-buffered solution at pH 3.5. Briefly, 10 μl of 67GaCl3 (18.5–37.0 MBq in 0.05 M HCl), 10 μL of 1 mg/mL DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH aqueous solution and 100 μL of 0.5 M NH4OAc (pH 3.5) were added into a reaction vial and incubated at 90°C for 20 min. After the incubation, 10 μL of 0.5% EDTA aqueous solution was added into the reaction vial to quench the reaction. The radiolabeled peptide was purified to single species by Waters RP-HPLC (Milford, MA) on a Grace Vadyc C-18 reverse phase analytical column (Deerfield, IL) using the following gradient at a flowrate of 1 mL/min. The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (20 mM HCl aqueous solution) and solvent B (100% CH3CN). The gradient was initiated and kept at 84:16 A/B for 3 min followed by a linear gradient of 84:16 A/B to 74:26 A/B over 20 min. Then, the gradient was changed from 74:26 A/B to 10:90 A/B over 3 min followed by an additional 5 min at 10:90 A/B. Thereafter, the gradient was changed from 10:90 A/B to 84:16 A/B over 3 min. The purified 67Ga-peptide sample was purged with N2 gas for 20 minutes to remove the acetonitrile. The pH of final solution was adjusted to 7.4 with 0.1 N NaOH and normal saline for cell work and animal studies. Serum stability of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was determined by incubation in mouse serum at 37°C according to the published procedure (19) for 24 h, and monitored for degradation by RP-HPLC.

Cellular Internalization and Efflux of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH

Cellular internalization and efflux of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH were evaluated in B16/F1 melanoma cells. After being washed once with binding medium, B16/F1 cells in cell culture plates were incubated at 25°C for 20, 40, 60, 90 and 120 min (n=3) in the presence of approximately 200,000 counts per minute (cpm) of HPLC-purified 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH. After incubation, the reaction medium was aspirated and the cells were rinsed with 2×0.5 mL of ice-cold pH 7.4, 0.2% BSA/0.01 M PBS. Cellular internalization of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was assessed by washing the cells with acidic buffer [40 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.5) containing 0.9% NaCl and 0.2% BSA] to remove the membrane-bound radioactivity. The remaining internalized radioactivity was obtained by lysing the cells with 0.5 mL of 1 N NaOH for 5 min. Membrane-bound and internalized 67Ga activities were counted in a gamma counter. Cellular efflux of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was determined by incubating B16/F1 cells with 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH for 2 h at 25°C, removing non-specific-bound activity with 2×0.5 mL of ice-cold pH 7.4, 0.2% BSA/0.01 MPBS rinse, and monitoring radioactivity released into cell culture medium. At time points of 20, 40, 60, 90 and 120 min, the radioactivities on the cell surface and in the cells were separately collected and counted in a Wallac 1480 automated gamma counter (PerkinElmer, NJ).

B16/F1 Flank Primary and B16/F10 Pulmonary Metastatic Melanoma Models

B16/F1 flank primary melanoma and B16/F10 pulmonary metastatic melanoma models were generated to evaluate the biodistribution properties of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH. B16/F1 or B16/F10 melanoma cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen Corporation, Grand Island, NY) containing NaHCO3 (2 g/L), which was supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, and 48 mg of gentamicin. B16/F1 flank primary melanoma tumors were generated by subcutaneously inoculating 1×106 B16/F1 cells/mouse in the right flank of the C57 mice (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN). The tumors reached approximately 0.2 g 10–12 days post the cell implantation. Pulmonary metastatic melanoma tumors were generated via injecting 2×105 B16/F10 cells/mouse into the C57 mice through the tail vein. The metastatic melanoma-bearing mice were used for biodistribution studies 16 days after cell injection.

Biodistribution Studies

All the animal studies were conducted in compliance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval. The biodistribution properties of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH were determined in B16/F1 flank melanoma-bearing C57 mice. Each mouse was injected with 0.037 MBq of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH through the tail vein. Groups of 5 mice were sacrificed at 0.5, 2, 4 and 24 h post-injection, and tumors and organs of interest were harvested, weighed and counted. Blood values were taken as 6.5% of the whole-body weight. The results were expressed as percent injected dose/gram (% ID/g) and as percent injected dose (% ID). The specificity of the tumor uptake of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was determined by blocking the tumor uptake with the co-injection of 10 μg of non-radiolabeled DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH. The biodistribution of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH in B16/F10 pulmonary metastatic melanoma-bearing C57 mice was determined and compared with that in normal C57 mice at 2 and 4 h post-injection.

Effect of L-lysine Co-injection on the Renal Uptake of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH

L-lysine co-injection is effective in decreasing the renal uptakes of radiolabeled α-MSH peptides. Hence, the effect of L-lysine co-injection on the renal uptake of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was examined in B16/F1 melanoma-bearing C57 mice. A group of 5 mice were injected with a mixture of 0.037 MBq of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH and 15 mg of L-lysine. The mice were sacrificed at 2 h post-injection, and tumors and kidneys were harvested, weighed and counted in a gamma counter.

Imaging Melanoma with 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH

The melanoma imaging properties of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH were examined in B16/F1 primary melanoma-bearing and B16/F10 pulmonary metastatic melanoma-bearing C57 mice. Two B16/F1 flank melanoma-bearing C57 mice were injected with 7.1 MBq of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH with or without 30 μg of non-radiolabeled DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH via the tail vein to demonstrate the specificity of the melanoma uptake. The mice were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane for small animal SPECT/CT (Nano-SPECT/CTR®, Bioscan) imaging 2 h post-injection. The 9-min CT imaging was immediately followed by the SPECT imaging of whole-body. The SPECT scans of 24 projections were acquired and total acquisition time was 60 min. Reconstructed data from SPECT and CT were visualized and co-registered using InVivoScope (Bioscan, Washington DC).

A B16/F10 pulmonary metastatic melanoma-bearing mouse was used for 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH SPECT/CT imaging to determine whether the melanoma metastases developed in the early stage (13 days post the cell injection) could be detected. The mouse was injected with 4.6 MBq of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH via the tail vein. The mouse was anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane for small animal SPECT/CT (Nano-SPECT/CT®, Bioscan) imaging 2 h post-injection. The 9-min CT imaging was immediately followed by the SPECT imaging of whole-body. Reconstructed data from SPECT and CT were visualized and co-registered using InVivoScope (Bioscan, Washington DC).

Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis was performed using the Student’s t-test for unpaired data to determine the significant differences between 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH with or without non-radiolabeled DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH co-injection, between the bodistribution of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH in pulmonary metastatic melanoma-bearing mice and normal mice, and between 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH with or without L-lysine co-injection. Differences at the 95% confidence level (p<0.05) were considered significant.

RESULTS

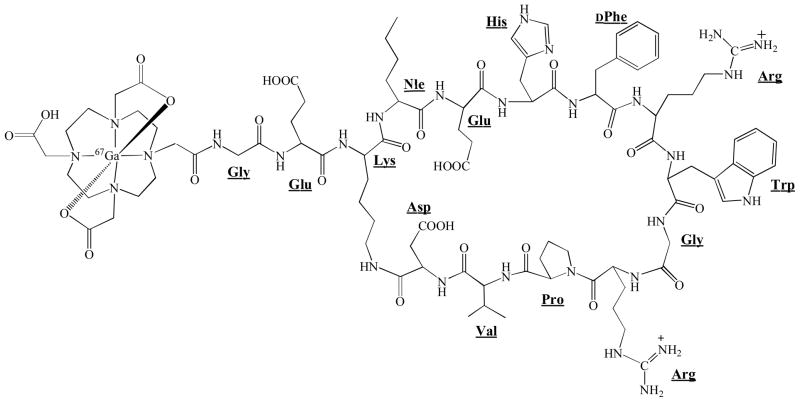

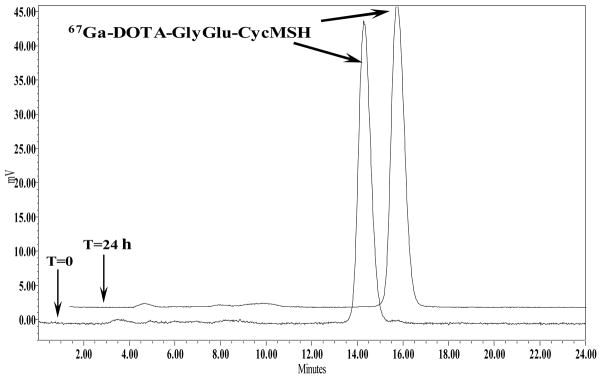

DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was synthesized, purified by RP-HPLC and characterized by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH displayed greater than 95% purity with 30% overall synthetic yield. The peptide was labeled with 67Ga using a 0.5 M NH4OAc-buffered solution at pH 3.5. The radiolabeling yield was greater than 95%. Figure 1 illustrates the schematic structure of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH. 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was completely separated from its excess non-labeled peptide by RP-HPLC. The retention times of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH and its non-labeled peptide were 14.4 and 15.9 min, respectively. 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was stable in mouse serum at 37°C. Only 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was detected by RP-HPLC after 24 h of incubation (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

The structure of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH.

Figure 2.

HPLC profile of radioactive 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH (T=0) and mouse serum stability of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH (T=24 h) after 24 h incubation at 37°C. The retention time of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was 14.4 min.

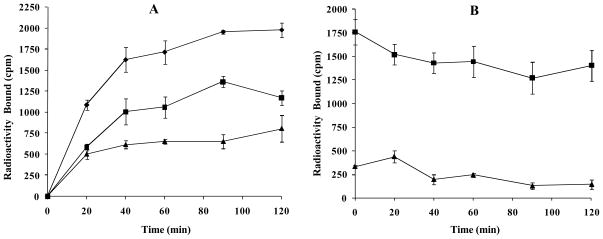

Cellular internalization and efflux of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH were evaluated in B16/F1 cells. Figure 3 illustrates cellular internalization and efflux of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH. 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH exhibited rapid cellular internalization and extended cellular retention. There was 53.82 ± 3.96% of the cellular uptake of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH activity internalized in the B16/F1 cells 20 min post incubation. There was 69.91 ± 3.33% of the cellular uptake of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH activity internalized in the cells after 90 min incubation. Cellular efflux results demonstrated that 79.77 ± 9.49% of the internalized 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH activity remained inside the cells 2 h after incubating cells in culture medium.

Figure 3.

Cellular internalization (A) and efflux (B) of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH in B16/F1 melanoma cells at 25°C. Total bound radioactivity (◆), internalized activity (■) and cell membrane activity (▴) were presented as counts per minute (cpm).

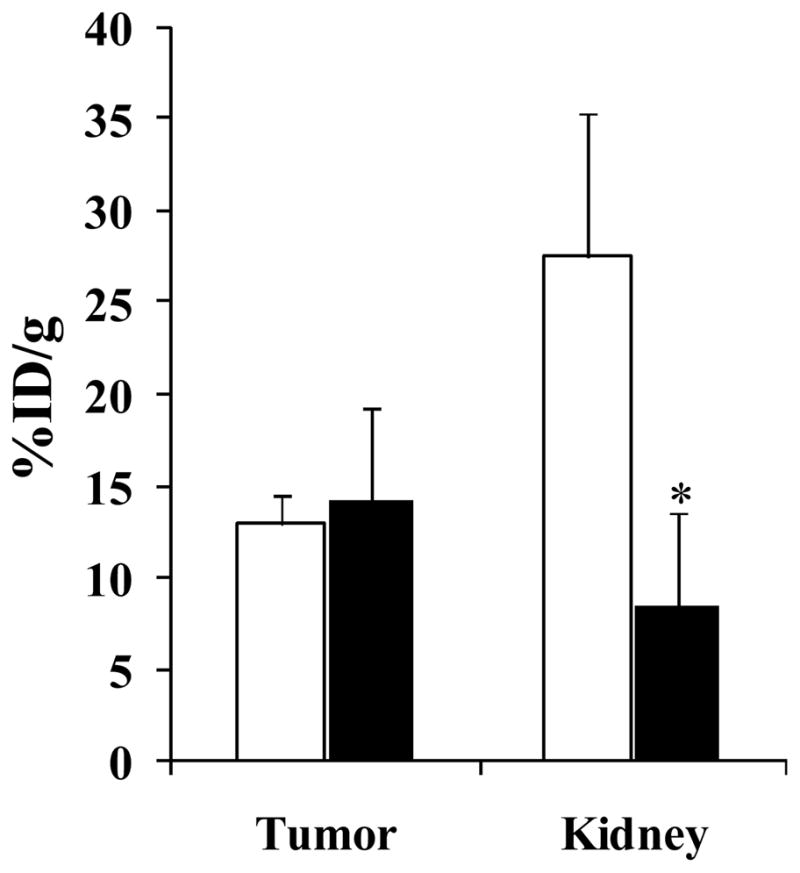

The pharmacokinetics and tumor targeting properties of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH were determined in B16/F1 flank primary melanoma-bearing and B16/F10 pulmonary metastatic melanoma-bearing C57 mice. The biodistribution results of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH are shown in Tables 1 and 2. 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH exhibited rapid and substantial tumor uptake. The tumor uptake value of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was 8.59 ± 1.37 %ID/g at 0.5 h post-injection. 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH reached its peak tumor uptake value of 12.93 ± 1.63 %ID/g at 2 h post-injection. There were 8.12 ± 0.60 %ID/g of the 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH activity remained in the tumors at 4 h post-injection. The tumor uptake value of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH decreased to 5.02 ± 1.35 %ID/g at 24 h post-injection. In the blocking study, the tumor uptake value of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH with 10 μg of non-radiolabeled DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH co-injection were only 2.9% of the tumor uptake value without non-radiolabeled DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH co-injection at 2 h post-injection (p<0.05), demonstrating that the tumor uptake was specific and receptor-mediated. Whole-body clearance of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was rapid, with approximately 82% of the injected radioactivity cleared through the urinary system by 2 h post-injection (Table 1). Normal organ uptakes of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH were generally very low (<0.30 %ID/g) except for the kidneys at 2, 4 and 24 h post-injection. The renal uptake values of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH were 23.94 ± 7.15, 27.55 ± 7.87, 22.60 ± 4.03 and 20.92 ± 5.77 %ID/g at 0.5, 2, 4 and 24 h post-injection. High tumor/blood and tumor/normal organ uptake ratios were demonstrated as early as 0.5 h post-injection except for the tumor/kidney ratio (Table 1). Co-injection of 15 mg of L-lysine reduced the kidney uptake value of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH to 8.32 ± 5.18% ID/g (69.8% reduction) without affecting the tumor uptake at 2 h post-injection (Fig. 4).

Table 1.

Biodistribution of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH in B16/F1 flank primary melanoma-bearing C57 mice. The data were presented as percent injected dose/gram or as percent injected dose (Mean±SD, n=5).

| Tissue | 0.5 h | 2 h | 2 h peptide blockade | 4 h | 24 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent injected dose/gram (%ID/g) | |||||

| Tumor | 8.59±1.37 | 12.93±1.63 | 0.37±0.02* | 8.12±0.60 | 5.02±1.35 |

| Brain | 0.10±0.03 | 0.01±0.01 | 0.01±0.00 | 0.01±0.00 | 0.01±0.00 |

| Blood | 1.22±0.59 | 0.05±0.04 | 0.24±0.02* | 0.17±0.13 | 0.15±0.11 |

| Heart | 0.29±0.10 | 0.04±0.04 | 0.04±0.01 | 0.05±0.02 | 0.14±0.13 |

| Lung | 1.44±0.47 | 0.02±0.02 | 0.04±0.03 | 0.11±0.09 | 0.10±0.06 |

| Liver | 0.69±0.27 | 0.23±0.01 | 0.29±0.04 | 0.25±0.07 | 0.24±0.08 |

| Spleen | 0.41±0.22 | 0.09±0.08 | 0.07±0.03 | 0.06±0.04 | 0.22±0.07 |

| Stomach | 1.30±0.36 | 0.08±0.07 | 0.06±0.05 | 0.08±0.07 | 0.07±0.04 |

| Kidneys | 23.94±7.15 | 27.55±7.87 | 22.75±4.32 | 22.6±4.03 | 20.92±5.77 |

| Muscle | 0.46±0.28 | 0.04±0.02 | 0.09±0.06 | 0.04±0.01 | 0.09±0.08 |

| Pancreas | 0.47±0.07 | 0.10±0.08 | 0.09±0.01 | 0.07±0.05 | 0.11±0.07 |

| Bone | 0.61±0.29 | 0.10±0.01 | 0.18±0.03 | 0.10±0.02 | 0.21±0.20 |

| Skin | 1.62±0.54 | 0.25±0.03 | 0.04±0.00* | 0.20±0.15 | 0.07±0.06 |

| Percent injected dose (%ID) | |||||

| Intestine | 2.76±1.34 | 0.37±0.23 | 0.74±0.10 | 0.35±0.16 | 0.20±0.01 |

| Urine | 77.33±0.74 | 81.90±2.42 | 92.00±1.50 | 86.59±1.73 | 88.56±6.78 |

| Tumor to normal tissue uptake ratio | |||||

| Tumor/Blood | 7.04 | 258.59 | 1.54 | 47.76 | 33.47 |

| Tumor/Kidney | 0.36 | 0.46 | 0.02 | 0.36 | 0.24 |

| Tumor/Lung | 5.97 | 646.48 | 9.25 | 73.82 | 50.20 |

| Tumor/Liver | 12.45 | 56.21 | 1.28 | 32.48 | 20.92 |

| Tumor/Muscle | 18.67 | 323.24 | 4.11 | 203.00 | 55.78 |

| Tumor/Skin | 5.30 | 51.72 | 9.25 | 40.60 | 71.71 |

p<0.05, significance comparison between 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH with or without peptide blockade at 2 h post-injection.

Table 2.

Biodistribution of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH in B16/F10 pulmonary metastatic melanoma-bearing (lung mets) and normal C57 mice (normal). The data were presented as percent injected dose/gram or as percent injected dose (Mean±SD, n=5).

| Tissue | 2 h | 4 h | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Mets | Normal | Lung Mets | Normal | |

| Percent injected dose/gram (%ID/g) | ||||

| Brain | 0.03±0.02 | 0.01±0.01 | 0.01±0.01 | 0.02±0.02 |

| Blood | 0.21±0.15 | 0.13±0.07 | 0.06±0.04* | 0.19±0.11 |

| Heart | 0.02±0.02* | 0.09±0.06 | 0.12±0.08 | 0.24±0.07 |

| Lung | 1.44±0.75* | 0.15±0.10 | 1.49±0.69* | 0.17±0.11 |

| Liver | 0.42±0.01* | 0.46±0.03 | 0.47±0.10 | 0.55±0.14 |

| Spleen | 0.41±0.07 | 0.33±0.08 | 0.14±0.11 | 0.04±0.04 |

| Stomach | 0.19±0.03 | 0.21±0.02 | 0.18±0.13 | 0.28±0.12 |

| Kidneys | 29.67±6.55 | 37.20±2.16 | 28.75±4.30 | 31.98±5.35 |

| Muscle | 0.07±0.01 | 0.10±0.05 | 0.17±0.11* | 0.05±0.02 |

| Pancreas | 0.16±0.09 | 0.15±0.07 | 0.18±0.09 | 0.20±0.07 |

| Bone | 0.16±0.09 | 0.12±0.08 | 0.44±0.09 | 0.42±0.16 |

| Skin | 0.57±0.19 | 0.50±0.09 | 0.33±0.12 | 0.46±0.15 |

| Percent injected dose (%ID) | ||||

| Intestines | 0.52±0.18 | 1.32±0.73 | 1.13±0.11 | 2.00±0.81 |

| Urine | 90.55±0.38 | 85.76±3.76 | 88.12±1.12 | 88.17±1.22 |

p<0.05, significance comparison between 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH in pulmonary metastatic melanoma-bearing and normal C57 mice.

Figure 4.

Effect of L-lysine co-injection on the renal uptake of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH at 2 h post-injection. Black and white columns represented the tumor and kidney uptakes of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH with or without L-lysine co-injection, respectively. L-lysine co-injection significantly (*p<0.05) reduced the renal uptake of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH by 69.8% at 2 h post-injection without affecting the tumor uptake.

The biodistribution results of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH in B16/F10 pulmonary metastatic melanoma-bearing C57 mice at 2 and 4 h post-injection are presented in Table 2 and compared with those in normal C57 mice. 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH exhibited significantly (p<0.05) higher uptake value in metastatic melanoma-bearing lung than that in normal lung. The uptake values of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH radioactivity in the metastatic melanoma-bearing and normal lungs were 1.44 ± 0.75 and 0.15 ± 0.10 %ID/g, 1.49 ± 0.69 and 0.17 ± 0.11 %ID/g at 2 and 4 h post-injection, respectively. The 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH displayed higher lung/normal organ uptake ratios in pulmonary metastatic melanoma-bearing mice than those in normal mice (Table 2). Similar rapid whole-body clearance of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH exhibited in both B16/F10 pulmonary metastatic melanoma-bearing C57 mice and normal C57 mice (Table 2).

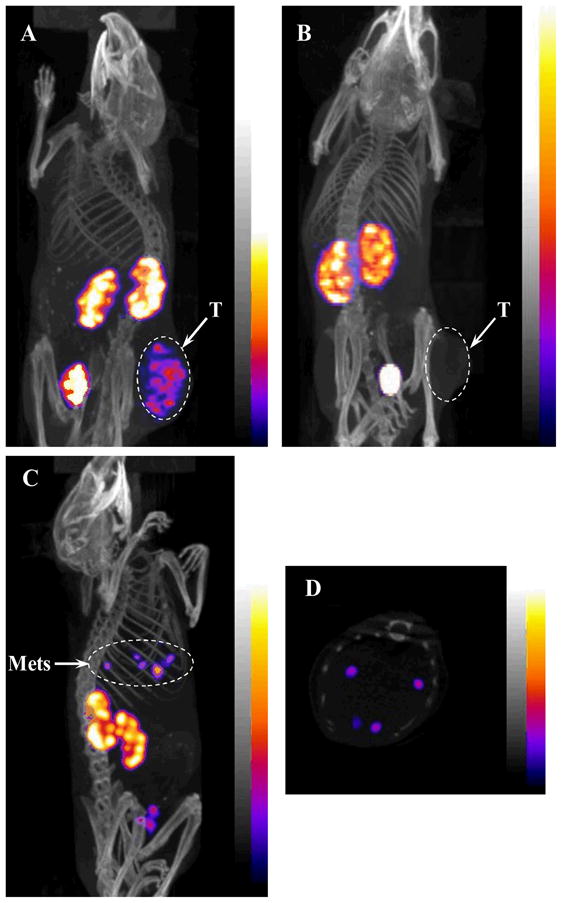

Two B16/F1 flank primary melanoma-bearing C57 mice were injected with 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH with or without non-radioactive DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH to visualize the tumors and determine the specificity of the tumor uptake at 2 h after dose administration. The whole-body SPECT/CT images of the mice are presented in Figures 5A and 5B. The flank melanoma tumors were clearly visualized by SPECT/CT using 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH as an imaging probe. 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH exhibited high tumor to normal organ uptake ratios except for the kidney, which were coincident with the biodistribution results. Accumulation of the 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH activity in the bladder demonstrated the major urinary clearance. Co-injection of non-radioactive DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH blocked the melanoma uptake (Fig. 5B), demonstrating the melanoma uptake of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was specific and MC1 receptor-mediated. A B16/F10 pulmonary melanoma-bearing C57 mouse was injected with 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH via the tail vein to image melanoma metastases early developed in the lung (13 days post the cell injection). The whole-body and transversal images are presented in Figures 5C and 5D. The pulmonary metastatic melanoma foci were clearly visualized in both whole-body and transversal images by SPECT/CT using 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH as an imaging probe.

Figure 5.

Whole-body images of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH in B16/F1 flank melanoma-bearing C57 mice with or without peptide blockade (A and B) at 2 h post-injection; Whole-body (C) and transversal (D) images of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH in a B16/F10 pulmonary metastatic melanoma-bearing C57 mouse at 2 h post-injection. Flank melanoma (T) and pulmonary melanoma metastases (Mets) were highlighted with arrows on the images.

DISCUSSION

Gallium-67 and Gallium-68 are attractive radiometals in nuclear medicine due to their suitable imaging properties for SPECT and PET. Compared to 68Ga, 67Ga has longer half-life and is thus a better radionuclide to use for examining the melanoma targeting property of the radioactive gallium-labeled lactam bridge-cyclized α-MSH peptide in vivo. In this study, we selected 67Ga to radiolabel the novel lactam bridge-cyclized DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH peptide to evaluate its potential for primary and metastatic melanoma detection. DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was readily labeled with 67Ga in greater than 95% radiolabeling yield. The metal chelator DOTA formed stable complex with 67Ga. 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was stable in serum at 37oC for 24 h (Fig. 2). 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH exhibited substantial melanoma uptake and prolonged melanoma retention in B16/F1 melanoma-bearing C57 mice (Table 1). 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH showed higher melanoma uptake values than those of 111In-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH (19). The tumor uptake values of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH were 1.24, 1.10 and 2.12 times the tumor uptake values of 111In-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH at 2, 4 and 24 h post-injection. In 2004, Froidevaux et al. (13) reported a 67Ga-labeled linear α-MSH peptide (67Ga-DOTA-NAPamide) for melanoma targeting. The tumor uptake values of 67Ga-DOTA-NAPamide were 9.43 ± 1.06 and 3.10 ± 0.36 %ID/g at 4 and 24 h post-injection in the B16/F1 flank melanoma-bearing C57 mice (13). 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH exhibited 14% less tumor uptake value than that of 67Ga-DOTA-NAPamide at 4 h post-injection. However, the tumor uptake value of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was 1.62 times the tumor uptake value of 67Ga-DOTA-NAPamide at 24 h post-injection. The renal uptake values of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH were 5.68 and 10.25 times the renal uptake values of 67Ga-DOTA-NAPamide at 4 and 24 h post-injection. Recently, it has been reported that different pathways may play roles in the mechanism of the renal uptakes of radiolabeled peptides besides the electrostatic interaction between the peptides and tubule cells (27, 28). For instance, the use of colchicines (preventing endocytosis in tubular cells) decreased the renal uptake up to 25% in a rat model (28). The transmembrane glycoprotein megalin involved in the renal uptakes of radiolabeled somatostatin analogues (29). Since the extracellular domains of megalin can accommodate a variety of ligands, megalin may be involved in the renal uptakes of other radiolabeled peptides. L-lysine co-injection decreased the renal uptake value by 69.8% at 2 h post-injection (Fig. 4), demonstrating that the electrostatic interaction between the peptide and tubular cells was a key factor for the renal uptake of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH. Reduction of the non-specific renal uptake of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH by L-lysine co-injection in this study was consistent with the published results on radiolabeled metal-cyclized α-MSH peptides (4). Although more studies need to be conducted in the future, it is likely that other mechanisms besides the electrostatic interaction involve in the renal uptake of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH as well.

Despite the clinical use of [18F]FDG in melanoma staging and melanoma metastases identification, [18F]FDG is not a melanoma-specific imaging agent and is also not effective in imaging small melanoma metastases (< 5 mm) and melanomas that have primary energy sources other than glucose (30–32). Radiolabeled lactam bridge-cyclized α-MSH peptides are melanoma-specific and can be employed to non-invasively confirm the identity of a tumor as melanoma. As showed in Fig. 5, the flank primary melanoma lesions were clearly visualized by SPECT/CT using 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH as an imaging probe. Importantly, the melanoma uptake of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was blocked by 30 μg of non-radioactive DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH, demonstrating the melanoma uptake of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was specific and MC1 receptor-mediated. 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH may have its greatest utilization when combined with a therapeutic radiometal-labeled DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH. Since the DOTA can form stable complexes with a variety of therapeutic radiometals (i.e. 177Lu, 90Y and 212Pb), the same DOTA-conjugated lactam bridge-cyclized α-MSH peptide can be radiolabeled with diagnostic and therapeutic radionuclides to yield matched-pair diagnostic and therapeutic peptides. The radiolabeled diagnostic peptide can be used to not only detect melanoma lesions, but also identify the expression levels of the MC1 receptors in different melanoma lesions. The important information on the expression of the MC1 receptors will provide the physicians critical guidance for selecting the right melanoma patients for MC1 receptor-targeted radionuclide therapy. The patient-specific dosimetry determined by the diagnostic peptide will guide the physicians to select safe and effective doses of the therapeutic peptide for the melanoma patients. Moreover, the follow-up imaging using the radiolabeled diagnostic peptide can monitor the response of melanoma to the treatment and provide the physicians the evidences for choosing more efficacious and safer therapeutic peptide doses to the melanoma patients for further treatment.

High mortality of malignant melanoma is tightly associated with the occurrence of metastatic melanoma due to its aggressiveness and resistance to current chemotherapy and immunotherapy regimens. Over the past several years, both radiolabeled linear and cyclic α-MSH peptides have been investigated to target the MC1 receptors for the detection of melanoma metastases (7, 12, 13, 20) by tissue autoradiograph and small animal SPECT/CT. Initially, linear 111In-DOTA-MSHoct and 67Ga-DOTA-NAPamide were reported to be able to identify both melanotic and amelanotic melanoma metastases in lung by tissue autoradiograph (12, 13). In 2007, 99mTc- and 111In-labeled metal-cyclized DOTA-Re(Arg11)CCMSH were reported to be successful in visualizing well-developed B16/F10 pulmonary melanoma metastases (24 days post the cell injection) in euthanized melanoma-bearing mice by small animal SPECT/CT (7), demonstrating the potential of using radiolabeled α-MSH peptides for non-invasive melanoma metastases imaging. Recently, we have reported the successful utilization of 111In-labeled lactam bridge-cyclized DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH in detecting B16/F10 relatively early-developed pulmonary metastases (17 and 20 days post the cell injection) in live melanoma-bearing mice by Nano-SPECT/CT® (20). Both individual metastatic melanoma foci (17 days post the cell injection) and bigger lesions (20 days post the cell injection) developed in the lung were clearly visualized with 111In-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH (20), demonstrating the feasibility of using 111In-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH as an imaging probe to monitor tumor response to therapy. Despite the fact that 111In-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH was superior to [18F]FDG in detecting pulmonary melanoma metastases reported in our previous publication (20), it was not answered whether the metastatic melanoma foci in the even earlier stage of development (< 17 days) could be detected by Nano-SPECT/CT® using radiolabeled DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH as an imaging probe. It seemed to us that it would be possible to detect the metastatic melanoma foci in the even earlier stage of development (< 17 days) based on the fact that the spatial resolution of Nano-SPECT with multiple-pinhole collimator was approximately 0.8 mm for a Jaszczak phantom filled with 111In aqueous solution. It was reported that pulmonary metastatic melanoma deposits were initially detectable by small animal CT approximately 15–18 days post tail vein injection of 0.2 million of B16/F10 melanoma cells (33). Hence, we selected 13 days post the cell injection (0.2 million B16/F10 cells) as an early development time point of pulmonary melanoma metastases to evaluate the imaging property of 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH in this study. As showed in Figs. 5C and 5D, individual pulmonary metastatic melanoma foci were clearly visualized by SPECT/CT using 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH as an imaging probe 2 h post-injection. Compared to the metastatic melanoma images we reported previously (20), the images of melanoma metastases reported in this study were even striking since the pulmonary melanoma metastases were developed only 13 days post the cell injection. The remarkable images of melanoma metastases presented in this study demonstrated the feasibility of using 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH as an effective imaging probe for early detection of metastatic melanoma.

In conclusion, 67Ga-DOTA-GlyGlu-CycMSH exhibited favorable primary and metastatic melanoma targeting and imaging properties, highlighting its potential as an effective imaging probe for early detection of primary and metastatic melanoma.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Dr. Fabio Gallazzi and Mr. Benjamin M. Gershman for their technical assistance. This work was supported in part by the Southwest Melanoma SPORE Developmental Research Program, the Oxnard Foundation, the DOD grant W81XWH-09-1-0105 and the NIH grant NM-INBRE P20RR016480. The image in this article was generated by the Keck-UNM Small Animal Imaging Resource established with funding from the W.M. Keck Foundation and the University of New Mexico Cancer Research and Treatment Center (NIH P30 CA118100).

References

- 1.Tatro JB, Reichlin S. Specific receptors for alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone are widely distributed in tissues of rodents. Endocrinology. 1987;121:1900–1907. doi: 10.1210/endo-121-5-1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegrist W, Solca F, Stutz S, Giuffre L, Carrel S, Girard J, Eberle AN. Characterization of receptors for alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone on human melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6352–6358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J, Cheng Z, Hoffman TJ, Jurisson SS, Quinn TP. Melanoma-targeting properties of 99mTechnetium-labeled cyclic α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone peptide analogues. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5649–5658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miao Y, Owen NK, Whitener D, Gallazzi F, Hoffman TJ, Quinn TP. In vivo evaluation of 188Re-labeled alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone peptide analogs for melanoma therapy. Int J Cancer. 2002;101:480–487. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miao Y, Whitener D, Feng W, Owen NK, Chen J, Quinn TP. Evaluation of the human melanoma targeting properties of radiolabeled alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone peptide analogues. Bioconjug Chem. 2003;14:1177–1184. doi: 10.1021/bc034069i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miao Y, Owen NK, Fisher DR, Hoffman TJ, Quinn TP. Therapeutic efficacy of a 188Re labeled α-melanocyte stimulating hormone peptide analogue in murine and human melanoma-bearing mouse models. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:121–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miao Y, Benwell K, Quinn TP. 99mTc- and 111In-labeled α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone peptides as imaging probes for primary and pulmonary metastatic melanoma detection. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miao Y, Hylarides M, Fisher DR, Shelton T, Moore HA, Wester DW, Fritzberg AR, Winkelmann CT, Hoffman TJ, Quinn TP. Melanoma therapy via peptide-targeted α-radiation. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5616–5621. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miao Y, Figueroa SD, Fisher DR, Moore HA, Testa RF, Hoffman TJ, Quinn TP. 203Pb-labeled alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone peptide as an imaging probe for melanoma detection. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:823–829. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.048553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miao Y, Hoffman TJ, Quinn TP. Tumor targeting properties of 90Y and 177Lu labeled alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone peptide analogues in a murine melanoma model. Nucl Med Biol. 2005;32:485–493. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miao Y, Shelton T, Quinn TP. Therapeutic efficacy of a 177Lu labeled DOTA conjugated α-melanocyte stimulating hormone peptide in a murine melanoma-bearing mouse model. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2007;22:333–341. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2007.376.A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Froidevaux S, Calame-Christe M, Tanner H, Sumanovski L, Eberle AN. A novel DOTA-α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analog for metastatic melanoma diagnosis. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:1699–1706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Froidevaux S, Calame-Christe M, Schuhmacher J, Tanner H, Saffrich R, Henze M, Eberle AN. A Gallium-labeled DOTA-α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analog for PET imaging of melanoma metastases. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:116–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Froidevaux S, Calame-Christe M, Tanner H, Eberle AN. Melanoma targeting with DOTA-alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analogs: structural parameters affecting tumor uptake and kidney uptake. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:887–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McQuade P, Miao Y, Yoo J, Quinn TP, Welch MJ, Lewis JS. Imaging of melanoma using 64Cu and 86Y-DOTA-ReCCMSH(Arg11), a cyclized peptide analogue of α-MSH. J Med Chem. 2005;48:2985–2992. doi: 10.1021/jm0490282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei L, Butcher C, Miao Y, Gallazzi F, Quinn TP, Welch MJ, Lewis JS. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Cu-64 labeled Rhenium-Cyclized α-MSH Peptide Analog Using a Cross-Bridged Cyclam Chelator. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:64–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei L, Miao Y, Gallazzi F, Quinn TP, Welch MJ, Vavere AL, Lewis JS. Ga-68 labeled DOTA-rhenium cyclized α-MSH Analog for imaging of malignant melanoma. Nucl Med Biol. 2007;34:945–953. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng Z, Xiong Z, Subbarayan M, Chen X, Gambhir SS. 64Cu-labeled alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analog for MicroPET imaging of melanocortin 1 receptor expression. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18:765–772. doi: 10.1021/bc060306g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miao Y, Gallazzi F, Guo H, Quinn TP. 111In-labeled lactam bridge-cyclized alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone peptide analogues for melanoma imaging. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:539–547. doi: 10.1021/bc700317w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo H, Shenoy N, Gershman BM, Yang J, Sklar LA, Miao Y. Metastatic melanoma imaging with an 111In-labeled lactam bridge-cyclized alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone peptide. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Green MA, Welch MJ. Gallium radiopharmaceutical chemistry. Int J Rad Appl Instrum B. 1989;16:435–448. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(89)90053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson CJ, Welch MJ. Radiometal-labeled agents (non-technetium) for diagnostic imaging. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2219–2234. doi: 10.1021/cr980451q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisenwiener K, Prata MI, Buschmann I, Zhang HW, Santos AC, Wenger S, Reubi JC, Mäcke HR. NODAGATOC, a new chelator-coupled somatostatin analogue labeled with [67/68Ga] and [111In] for SPECT, PET, and targeted therapeutic applications of somatostatin receptor (hsst2) expression tumors. Bioconjug Chem. 2002;13:530–541. doi: 10.1021/bc010074f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhernosekov K, Aschoff P, Filosofov D, Jahn M, Jennewein M, Adrian HJ, Bihl H, Rösch F. Visualisation of a somatostatin receptor-expressing tumor with 67Ga-DOTATOC SPECT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:1129. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-1864-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mariani G, Bodei L, Adelstein SJ, Kassis AI. Emerging roles for radiometabolic therapy of tumors based on auger electron emission. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1519–1521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maecke HR, Hofmann M, Haberkorn U. 68Ga-labeled peptides in tumor imaging. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:172S–178S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Béhé M, Kluge G, Becker W, Gotthardt M, Behr TM. Use of polyglutamic acids to reduce uptake of radiometal-labeled minigastrin in the kidneys. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1012–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rolleman EJ, Krenning EP, Van Gameren A, Bernard BF, De Jong M. Uptake of [111In-DTPA0]octreotide in the rat kidney is inhibited by colchicine and not by fructose. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:709–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Jong M, Barone R, Krenning EP, Bernard BF, Melis M, Vissor T, Gekle M, Willnow TE, Walrand S, Jamar F, Pauwels S. Megalin is essential for renal proximal tubule reabsorption of 111In-DTPA-Octreotide. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1696–1700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alonso O, Martínez M, Delgado L, De León A, De Boni D, Lago G, Garcés M, Fontes F, Espasandín J, Priario J. Staging of regional lymph nodes in melanoma patients by means of 99mTc-MIBI scintigraphy. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1561–1565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nabi HA, Zubeldia JM. Clinical application of 18F-FDG in oncology. J Nucl Med Technol. 2002;30:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Strauss LG, Burger C. Quantitative PET studies in pretreated melanoma patients: A comparison of 6-[18F]fluoro-L-DOPA with 18F-FDG and 15O-water using compartment and non-compartment analysis. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:248–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winkelmann CT, Figueroa SD, Rold TL, Volkert WA. Microimaging characterization of a B16-F10 melanoma metastasis mouse model. Molecular Imaging. 2006;5:105–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]