Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy of the Fostering Healthy Futures (FHF) program in reducing mental health and associated problems.

Design

Randomized controlled trial.

Setting

Denver Metro Area.

Participants

9–11-year-old children who were maltreated and placed in foster care.

Intervention

Children in the control group (n=77) received an assessment of their cognitive, educational, and mental health functioning. Children in the intervention (n=79) received the assessment and participated in a 9-month mentoring and skills group program.

Main Outcome Measures

Children and caregivers were interviewed at baseline prior to randomization (T1), immediately post-intervention (T2), and 6-months post-intervention (T3). Teachers were interviewed at two timepoints post baseline. Measures included a multi-informant index of mental health problems, youth-reported symptoms of posttraumatic stress, dissociation, and quality of life, and caregiver- and youth-reported use of mental health services and psychotropic medications.

Results

After adjusting for covariates, intent-to-treat analyses demonstrated that the treatment group had fewer mental health problems on a multi-informant factor at T3 (mean difference:−.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], −.84 to −.19), reported fewer symptoms of dissociation at T3 (mean difference: −3.66, CI, −6.58 to −.74), and reported better quality of life at T2 (mean difference: .11, CI, .03 to .19). Fewer intervention youth had received recent mental health therapy at T3, according to youth report (53% vs 71%; relative risk, .75, CI, .57 to .98).

Conclusions

A 9-month mentoring and skills group intervention for children in foster care can be implemented with fidelity and high uptake rates, resulting in improved mental health outcomes.

Introduction

In the U.S. in 2007, 5.8 million children were referred to Child Protective Services and maltreatment was substantiated for 794,000 of them (approximately 1% of the child population).1 In the same year, 496,000 children were in foster care on September 30th (approximately .7% of the child population).1–2 African American and multiracial children were overrepresented among children in care.3

Children who have been maltreated and placed in foster care are at risk for significant mental health problems including depression, post-traumatic stress, dissociation, social problems, suicidal behavior, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and conduct disorders.4–7 In a large study of children receiving child welfare services, 42% met diagnostic criteria for a DSM-IV diagnosis.6 Studies of Medicaid claims suggest that as many as 57% of youth in foster care meet criteria for a mental disorder.8

Rates of service use are also higher among children placed in foster care.9 One California study found that children in foster care, who comprised less than 4% of Medi-Cal-eligible children, accounted for 41% of all users of Medi-Cal mental health services.10 Another study found that children in foster care used more mental health services (including hospitalizations) than did children in the Aid to Families with Dependent Children program or children receiving Supplemental Security Income.8, 11 Although children in care are significant consumers of mental health services, some evidence suggests that many children do not receive needed services. In a recent, nationally-representative study, between 37% and 44% of youth with child welfare service involvement scored in the borderline or clinical ranges on measures of mental health functioning, but only 11% of these youth were receiving outpatient mental health services.12

Despite the need for contextually-sensitive, evidence-based prevention and intervention efforts for this high-risk population, few rigorous trials have been conducted. The Fostering Healthy Futures (FHF) nine-month preventive intervention was designed for preadolescent children, ages 9–11, recently placed in foster care due to child maltreatment. FHF includes two major components: skills groups and mentoring. Skills groups, which have been used effectively with other high-risk preadolescent populations, were designed to bring children in foster care together in order to reduce stigma and provide opportunities for them to learn skills in a supportive environment. Mentoring, which has demonstrated short-term efficacy in some studies, was designed to provide children in foster care with an additional supportive adult who could serve as a role model and advocate.

It was hypothesized that youth randomized to the intervention would evidence better self-esteem, social support, social acceptance and coping skills immediately following the program and that these improvements would be associated with better mental health functioning and improved quality of life six months post-program.

Methods

Participants

The study was conducted from July, 2002 to January, 2009 in two participating Colorado counties. Participants were recruited in 5 cohorts over 5 consecutive summers from a list of all children, aged 9–11, who were placed in foster care in participating counties. Children were recruited if they: 1) had been placed in foster care by court order due to maltreatment within the preceding year, 2) currently resided in foster care within a 35-minute drive to skills groups sites, 3) had lived with their current caregiver for at least 3 weeks, and 4) demonstrated adequate proficiency in English (although their caregivers could be monolingual Spanish speaking). When multiple members of a sibling group were eligible, one sibling was randomly selected to participate in the RCT. Letters explaining the study were sent to families, followed by recruitment calls a week later. Participation was voluntary, and could not be court-ordered.

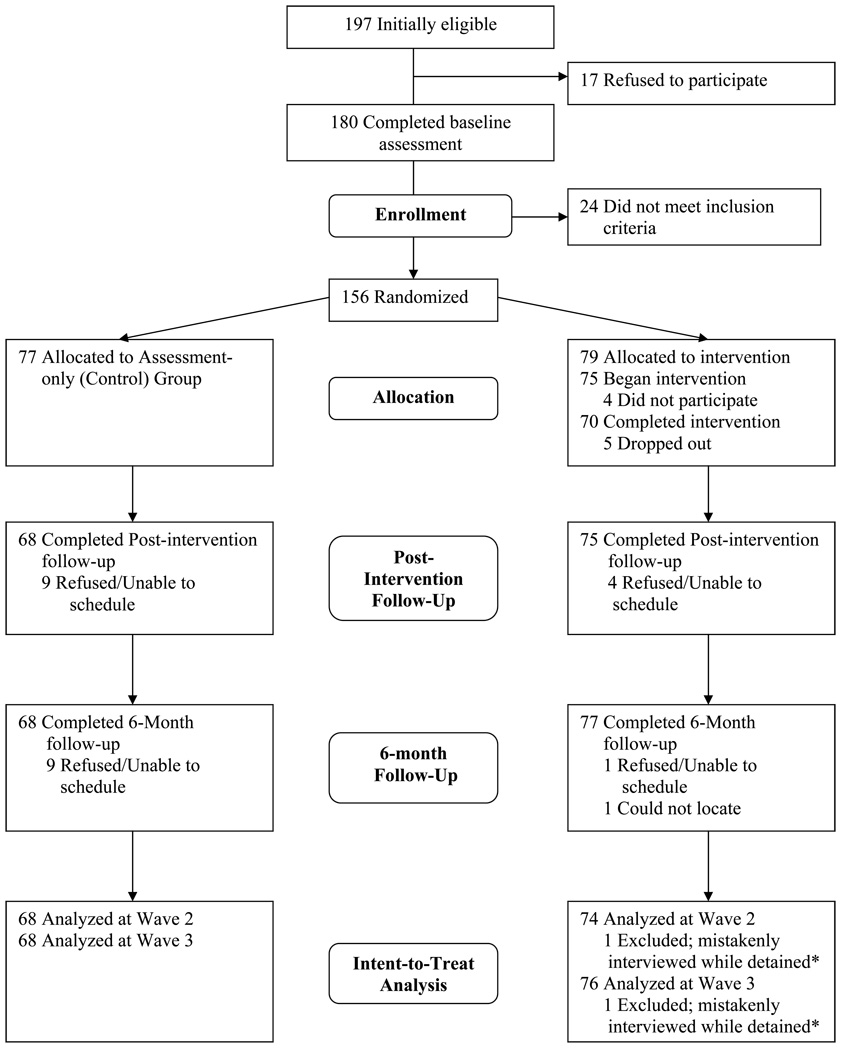

As the CONSORT diagram in Figure 1 shows, 91.3% percent of eligible children and their caregivers agreed to participate. After the baseline interview and prior to randomization, 13.3% of the participants were deemed ineligible for the following reasons: 6 were no longer in foster care, 7 had information on their child welfare records (obtained post-interview) that made them ineligible (e.g. incorrect birthdate), 9 were developmentally delayed, and 2 were not proficient enough in English to participate in the skills groups. Of the remaining 156 who were randomized to treatment and control groups, 8.3% were lost to follow-up at T2 and 7.1% at T3.

Figure.

CONSORT Diagram

*At both follow-up timepoints, one child was mistakenly interviewed while detained (the interviewers were told by the child’s legal guardian, who provided consent, that the child was in a residential treatment facility). Because the study had not yet obtained an approved prisoner protocol through our IRB and the Office for Human Research Protections, these data were unable to be analyzed.

Study Protocol

The study protocol was IRB-approved, and informed consent and assent were obtained. All children who participated in the baseline interview (n=180) were screened for cognitive, educational, and mental health problems, using standardized tests of intellectual ability13 and academic achievement,14 as well as normed caregiver- and child-report measures of psychological functioning. The findings and accompanying recommendations were summarized in reports provided to children’s caseworkers, who were encouraged to use the reports to advocate for educational and mental health evaluation and services.

Eligible children in both the “assessment only” (hereafter referred to as Control) and the “assessment plus intervention” (hereafter referred to as Intervention) groups were assessed at three timepoints: 1) Baseline (2–3 months prior to the start of the intervention), 2) Time 2, immediately post-intervention (11–13 months post-baseline), and 3) Time 3, 6-months post-intervention (17–20 months post-baseline). At each timepoint, children and their current caregivers were interviewed by separate interviewers, typically at the child’s residence. Interviewers were masked to condition, although some participants spontaneously disclosed their treatment condition. Children and caregivers were paid $40.00 for their participation. Teachers of participating children were also surveyed during the spring of two consecutive years – 10 months post-baseline (T2), and one year later (T3). At T2, 91.7% of children’s teachers were interviewed and at T3, 89.1% of children’s teachers were interviewed. Following the baseline interview, children were randomized after stratifying on gender and county. All children were manually randomized, by cohort, in a single block.

Intervention

The nine-month Fostering Healthy Futures (FHF) preventive intervention consisted of two components: 1) manualized skills groups,15 and 2) one-on-one mentoring16 by graduate students in social work (FHF is described in detail elsewhere17). The program was designed to be “above and beyond treatment as usual.” Although eligibility criteria required that children be in foster care at the start of the intervention, if they reunified or changed placements during the intervention, their participation continued following appropriate consent.

Skills Groups

FHF skills groups met for 30 weeks for 1.5 hours/week during the academic year and included 8–10 children and 2 group facilitators (licensed clinicians and graduate student trainees). The FHF skills groups followed a manualized curriculum that combined traditional cognitive-behavioral skills group activities with process-oriented material. Units addressed topics including: emotion recognition, perspective taking, problem solving, anger management, cultural identity, change and loss, healthy relationships, peer pressure, abuse prevention, and future orientation.17 The skills group curriculum was based on materials from evidence-based skills group programs, including Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies18–19 and Second Step20, which were supplemented with project-designed exercises from multicultural sources. The skills group curriculum included weekly activities that encouraged children to practice newly learned skills with their mentors in their communities.

Mentoring

The mentoring component of the FHF program provided 30 weeks of one-on-one mentoring for each child. Mentors were graduate students in social work who received course credit for their work on the project. Mentors were each paired with two children with whom they spent 2–4 hours of individual time each week. They also transported children to and from skills groups and joined the skills group for dinner. Mentors received weekly individual and group supervision and attended a didactic seminar, all of which were designed to support mentors as they: 1) created empowering relationships with children, serving as positive examples for future relationships, 2) ensured that children received appropriate services in multiple domains and served as a support for children as they faced challenges within various systems, 3) helped children generalize skills learned in group to the “real world” by completing weekly activities, 4) engaged children in a range of extracurricular, educational, social, cultural, and recreational activities, and 5) promoted attitudes to foster a positive future orientation. All of the mentoring activities employed by mentors were individually tailored for each child, based on the children’s presenting problems, strengths, and interests, as well as their family and placement characteristics.17

Program Uptake and Fidelity

On average, children attended 25.0 (Median=26.5, SD=5.8) of the 30 skills groups and 26.7 (Median=28, SD=6.25) of the 30 targeted mentoring visits. These numbers include data from children who withdrew from the program (n=5). The 30 skills group sessions included 108 discrete activities.15, 17 On average, across 11 groups, 104 (Median=106, SD=5.2) of the 108 group activities were completed.

Primary Outcome Measures

Mental health functioning was assessed using (1) child self-report on the posttraumatic stress and dissociation scales of the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (TSCC)21, a widely-used symptom-oriented measure of mental health problems, and (2) a multi-informant index of mental health problems. The mental health index was created based on principal components factor analysis of the children’s mean TSCC scores, and the Internalizing scales of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)22 and the Teacher Report Form (TRF),22 completed by children’s caregivers and teachers. The CBCL and TRF are well-normed measures of child emotional and behavior problems. The factor score explained 42% of the variance in these measures and factor loadings ranged from .59−.70. Children also completed the Life Satisfaction Survey,23 a quality of life measure, which asked respondents to rate satisfaction in several different domains (e.g. school, home, health, friendships). Children’s use of mental health services and psychotropic medications were assessed based on: (1) caregiver-report of services and medications used within the past month, and (2) child-report of services and medications used within the past 9 months at T2 and the past 6 months at T3.

Secondary Outcome Measures

Other constructs, related to mental health functioning, were also examined. These included (all child self-report measures): (1) Positive and Negative Coping scales from The Coping Inventory,24 which includes 42 strategies for coping with problems; (2) The Social Acceptance and Global Self-Worth scales of The Self-Perception Profile for Children,25–26 a widely-used measure of perceived self-competence; (3) a Social Support Factor Score, created based on principal components factor analysis of scale scores from The People in My Life – Short Form27–29 used to assess social support from caregivers, peers, and mentors (each in a separate scale). The social support factor score explained 45% of the variance in these three scales; factor loadings ranged from .63−.74.

Statistical Analyses

Equivalence between intervention and control groups on baseline characteristics and outcome measures was assessed using chi-square tests for categorical variables and one-way ANOVA for continuous variables. Attritted and non-attritted youth were compared on all baseline measures. Chi-square tests were also used to assess whether the rate of attrition varied by treatment condition.*

Linear regression was used to estimate effect sizes for continuous outcome variables, adjusting for baseline scores on the outcome measures and those variables that differed between conditions at baseline. Effect sizes were estimated with Cohen’s d, calculated as the difference between the adjusted means for the intervention and control conditions divided by the pooled standard deviation. Poisson regression with robust error variance was used to estimate relative risks for dichotomous outcomes, adjusting for baseline scores on corresponding outcome measures and those covariates that differed at baseline. Effect sizes were estimated as relative risks. All analyses used the intent-to-treat sample. Sample size for each analysis varied slightly due to missing data on outcome variables. All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Differences on Baseline Characteristics

Intervention youth were more likely to have higher IQ scores, F(1,155)=4.52, p=.04, to have been physically abused, χ2(1,N=156)=3.80, p=.05, and to have mothers with criminal histories, χ2(1,N=156)=6.54, p=.01 (see Table 1). A trend suggested that intervention youth were more frequently exposed to illegal activity, χ2(1,N=156)=3.04, p=.08. All four of these variables were used as covariates in linear and poisson regression models.

Table 1.

Baseline Differences

| Control (n = 77) |

Intervention (n = 79) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | ||

| Child characteristics | ||

| Age, Mean (SD) | 10.4 (0.9) | 10.4 (0.9) |

| Male, No. (%) | 38 (49) | 41 (52) |

| Hispanic, No. (%) | 43 (56) | 35 (44) |

| African American, No. (%) | 19 (25) | 27 (34) |

| Caucasian, No. (%) | 34 (44) | 33 (42) |

| IQ scores, Mean (SD) | 94.0 (12.5) | 98.3 (12.8)* |

| Maternal characteristics | ||

| Controlled substance use history, No. (%) | 45 (58) | 56 (72) |

| Criminal history, No. (%) | 34 (44) | 51 (65)* |

| Mental illness, No. (%) | 29 (38) | 31 (39) |

| Maltreatment history, No. (%) | 15 (20) | 19 (24) |

| Maltreatment characteristics | ||

| Family referrals to social services, Mean (SD) | 3.2 (3.4) | 4.2 (4.8) |

| Length of time in foster care, Mean (SD) | 0.6 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.3) |

| Physical abuse, No. (%) | 19 (25) | 31 (39)* |

| Sexual abuse, No. (%) | 11 (14) | 7 (9) |

| Failure to provide neglect, No. (%) | 40 (52) | 37 (47) |

| Lack of supervision neglect, No. (%) | 57 (74) | 61 (77) |

| Emotional abuse, No. (%) | 51 (66) | 45 (57) |

| Moral neglect (exposure to illegal activity), No. (%) | 21 (27) | 32 (40) t |

| Outcome measures | ||

| Primary variables | ||

| Mental health factor score, multi-informant, Mean (SD) | .03 (1.0) | −.03 (1.0) |

| Posttraumatic symptoms, youth report, t score, Mean (SD) | 48.0 (9.5) | 47.7 (9.1) |

| Dissociation symptoms, youth report, t score, Mean (SD) | 48.5 (9.7) | 48.7 (9.5) |

| Quality of life, youth report, Mean (SD) | 2.7 (0.3) | 2.7 (0.3) |

| Received MH therapy ever, youth report, No. (%) | 55 (71) | 56 (71) |

| Received MH therapy past month, caregiver report, No. (%) | 47 (64) | 50 (63) |

| Medication for MH problems ever, youth report, No. (%) | 11 (14) | 13 (17) |

| Medication for MH problems past month, caregiver report, No. (%) | 9 (12) | 9 (11) |

| Secondary variables | ||

| Positive coping, youth report, Mean (SD) | 1.9 (0.4) | 2.0 (0.4)t |

| Negative coping, youth report, Mean (SD) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) |

| Global self-worth, youth report, Mean (SD) | 3.4 (0.6) | 3.5 (0.6) |

| Social acceptance, youth report, Mean (SD) | 3.0 (0.8) | 3.2 (0.8) |

| Social support factor score, youth report, Mean (SD) | −0.14(1.0) | 0.13(1.0)t |

Abbreviations: MH, mental health; SD, standard deviation; No., number

p < .05

p < .10

Attrition

Those interviewed at follow-up were compared with non-interviewed children on all baseline characteristics and outcome measures. At T2 and T3, those not interviewed had lower IQ scores, T2:F(1,155)=9.99, p<.01; T3 F(1,155)=16.34, p<.01. Those not interviewed at T3 scored higher on the mental health factor score, F(1,156)=4.72, p=.03. Chi-square analyses suggested that rates of attrition did not differ by treatment condition at either T2, χ2(1, N=156)=1.37, p=.24, or T3, χ2(1,N=156)=3.42, p=.06.

Outcome Analyses

Intervention effects on primary and secondary outcomes at T2 and T3 are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. All analyses controlled for the corresponding T1 score and those covariates that differed between groups at baseline.

Table 2.

Impact of the FHF Intervention on T2 Outcome Variables

| Actual Mean (SE)/% | Adj Mean (SE)/% | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Control | FHF | Control | FHF | Adj. Mean Difference (95% CI) |

Cohen’s d/ RR (95% CI) |

p | |

| Primary Outcomes | ||||||||

| MH sxs factor (y, cg, t) | 127 | −.06(.13) | .05(.12) | −.04(.11) | .04(.11) | .07(−.25, .39) | .07(−.25, .39) | .66 |

| Trauma sxs (y) | 140 | 45.44(1.25) | 44.18(1.17) | 45.33(1.19) | 44.28(1.12) | −1.05(−4.33, 2.33) | −.10(−.43, .22) | .53 |

| Dissociation (y) | 140 | 46.23(1.21) | 45.76(1.21) | 46.64(1.14) | 45.39(1.07) | −1.24(−4.39, 1.90) | −.13(−.45, .19) | .44 |

| Quality of life (y) | 140 | 2.66(.03) | 2.78(.03) | 2.66(.03) | 2.78(.03) | .11(.03, .19) | .42(.12, .71) | .006 |

| Recent MH tx (y) % | 139 | 71% | 66% | 71% | 63% | .88(.70, 1.11) | .28 | |

| Current MH tx (cg) % | 133 | 70% | 57% | 68% | 55% | .81(.62, 1.06) | .12 | |

| Recent MH meds (y) % | 140 | 21% | 19% | 14% | 9% | .65(.33, 1.29) | .22 | |

| Current MH meds (cg) % | 132 | 22% | 19% | 12% | 13% | 1.07(.59, 1.94) | .83 | |

| Secondary Outcomes | ||||||||

| Positive coping (y) | 140 | 1.89(.05) | 1.99(.04) | 1.93(.04) | 1.96(.04) | .03(−.08, .14) | .09(−.22, .39) | .59 |

| Negative coping (y) | 140 | 1.23(.02) | 1.21(.02) | 1.22(.02) | 1.21(.02) | −.01(−.07, .04) | −.08(−.41, .25) | .64 |

| Global self-worth (y) | 140 | 3.42(.08) | 3.49(.07) | 3.44(.07) | 3.47(.06) | .03(−.15, .21) | .05(−.25, .34) | .76 |

| Social acceptance (y) | 140 | 3.03(.09) | 3.25(.09) | 3.08(.09) | 3.20(.08) | .12(−.12, .36) | .16(−.15, .48) | .32 |

| Social support factor (y) | 140 | −0.23(.13) | 0.21(.11) | −.13(.11) | 0.12(.10) | .25(−.05, .54) | .25(−.05, .54) | .10 |

Abbreviations: Adj., adjusted; SE, standard error; Control, control group; FHF, treatment group; d, Cohen’s d calculated as the difference between the adjusted means divided by the pooled standard deviation; RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval; p, p-value; MH, mental health; sxs, symptoms; tx, therapy; meds, psychotropic mediations; y, youth-report; cg, caregiver-report; t, teacher-report.

Table 3.

Impact of the FHF Intervention on T3 Outcome Variables

| Actual Mean (SE)/% | Adj Mean (SE)/% | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Control | FHF | Control | FHF | Adj. Mean Difference (95% CI) |

Cohen’s d/ RR (95% CI) |

p | |

| Primary Outcomes | ||||||||

| MH sxs factor (y, cg, t) | 132 | .22(.14) | −.20(.10) | .27(.12) | −.25(.11) | −.51(−.84, −.19) | −.51(−.84, −.19) | .003 |

| Trauma sxs (y) | 144 | 43.71(1.16) | 41.76(1.02) | 44.15(1.08) | 41.36(1.02) | −2.79(−5.77, .19) | −.30(−.63, .02) | .07 |

| Dissociation (y) | 144 | 45.51(1.30) | 42.70(.92) | 45.96(1.06) | 42.30(1.00) | −3.66(−6.58, −.74) | −.39(−.70, −.08) | .02 |

| Quality of life (y) | 143 | 2.74(.04) | 2.78(.03) | 2.74(.03) | 2.78(.03) | .04(−.05, .13) | .14(−.17, .45) | .38 |

| Recent MH tx (y) % | 142 | 71% | 54% | 71% | 53% | .75(.57, .98) | .04 | |

| Current MH tx (cg) % | 135 | 57% | 50% | 58% | 48% | .82(.59, 1.12) | .21 | |

| Recent MH meds (y) % | 142 | 22% | 17% | 15% | 10% | .67(.34, 1.31) | .25 | |

| Current MH meds (cg) % | 135 | 24% | 14% | 17% | 10% | .61(.30, 1.27) | .18 | |

| Secondary Outcomes | ||||||||

| Positive coping (y) | 143 | 1.90(.04) | 2.02(.04) | 1.92(.04) | 2.00(.04) | .09(−.03, .20) | .25(−.09, .58) | .15 |

| Negative coping (y) | 143 | 1.24(.02) | 1.21(.02) | 1.25(.02) | 1.20(.02) | −.04(−.10, .02) | −.21(−.51, .08) | .16 |

| Global self worth (y) | 143 | 3.50(.07) | 3.58(.06) | 3.48(.06) | 3.58(.06) | .10(−.06, .27) | .19(−.12, .50) | .23 |

| Social acceptance (y) | 143 | 3.16(.08) | 3.34(.07) | 3.20(.07) | 3.30(.07) | .11(−.10, .31) | .17(−.15, .48) | .30 |

| Social support factor (y) | 142 | −.05(.12) | .03(.11) | −.02(.12) | .00(.11) | .02(−.31, .36) | .02(−.31, .36) | .89 |

Abbreviations: Adj., adjusted; SE, standard error; Control, control group; FHF, treatment group; d, Cohen’s d calculated as the difference between the adjusted means divided by the pooled standard deviation; RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval; p, p-value; MH, mental health; sxs, symptoms; tx, treatment; meds, psychotropic medications; y, youth-report; cg, caregiver-report; t, teacher-report

Primary outcomes

At T2, there were no group differences on mental health symptomatology, but at T3, intervention youth scored lower on the multi-informant mental health factor (mean difference:−.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], −.84 to −.19). At T3, intervention youth also reported fewer symptoms of dissociation than did control youth (mean difference: −3.66, CI, −6.58 to −.74), and there was a trend suggesting that they were less likely to report symptoms of posttraumatic stress (mean difference: −2.79, CI, −5.77 to .19). At T2, groups did not differ on self- or caregiver-reported use of mental health services or psychotropic medication. At T3, however, intervention youth were less likely to report receiving recent mental health therapy (53% vs. 71%; RR=.75; CI, .57 to .98). At T2, intervention youth scored higher on a self-report scale measuring quality of life (mean difference: .11, CI, .03 to .19).

Secondary outcomes

There were no statistically significant differences between groups on any of the scales measuring secondary outcomes at T2 or T3, although a trend suggested that intervention youth were more likely than control youth to report receiving social support at T2 (mean difference: .25, CI, −.05 to .54).

Comment

This is the first known study to test, in a rigorous randomized controlled trial, the impact of a mentoring and skills group preventive intervention on the mental health outcomes of preadolescent maltreated children placed in foster care. The intervention demonstrated significant impact in reducing mental health symptomatology, especially symptoms associated with trauma, anxiety, and depression in this high-risk population. These findings are strengthened by the fact that the study controlled for baseline functioning, and multiple informants reported on children’s mental health functioning. In addition, the pattern of results suggested that program participants were less likely to use mental health therapy and psychotropic medication.

Although mental health functioning improved among program participants relative to controls, the effect was not apparent until six months post-intervention. Group differences on primary outcomes were not expected at T2 for several reasons. First, we hypothesized that improved functioning on primary outcomes would follow improved functioning on secondary outcomes. It was also hypothesized that short-term mental health functioning among program participants might be adversely impacted by participants’ need to say goodbye to mentors and program staff upon completion of the program, which corresponded with the T2 follow-up. Although study hypotheses about mental health effects and their timing were supported, hypotheses about short-term effects on secondary outcomes were not. The overall pattern of results on short-term impacts, however, was in the expected direction, and a trend suggested that program participation was associated with higher perceived social support at T2.

Findings of program efficacy are consistent with a large body of evidence suggesting that skills training curricula are effective in reducing risk and promoting mental health. Skills groups have demonstrated efficacy in multiple contexts and with diverse populations, including maltreated youth.30–32 Social skills groups may be particularly useful for children in foster care, as they often lack critical social skills, may have recently changed schools and peer groups, and may know no other children in foster care.

On the other hand, the current study’s findings provide valuable information to inform the evidence base for mentoring, which has much less empirical support despite its ideological promise.33–34 Although some studies suggest that mentoring can have a positive impact on youth functioning,35–38 there is reason for caution. Experimental studies of mentoring programs, particularly randomized controlled trials, are rare, and some studies fail to produce evidence of efficacy.39–42 Two recent large-scale evaluations of programs with a mentoring component failed to demonstrate effectiveness and one of the studies produced iatrogenic effects.43–44 Although there has been little empirical research, there has been enormous public and private investment in mentoring programs. Over $100 million in federal dollars, annually since 2004, have been dedicated to mentoring programs nationally.45–46 A 2006 Social Policy Report by the Society for Research in Child Development on mentoring research concluded, “There are few other areas where the research-program/policy connection is as badly needed.”47

FHF is one of the first randomized clinical trials with a high-risk population to demonstrate the efficacy of a mentoring program on mental health outcomes. Although the FHF program employs a fairly traditional community-based mentoring model, the fact that it is paired with skills groups may be particularly effective. Furthermore, FHF mentoring incorporates those practices that appear to enhance the effectiveness of mentoring. A meta-analysis of mentoring programs found that program effects were significantly enhanced when programs targeted high-risk youth and incorporated several “best practices.” Programs that used mentors with prior experience in a helping role or profession, those that provided for ongoing training of mentors, and those that provided structured activities for mentors and participating youth had the most beneficial effect on youth identified as high risk.48

The study’s methodological approach also speaks to the generalizability of the study findings. All eligible children in participating counties were recruited and the high recruitment, retention, and program uptake rates suggest that this intervention was contextually sensitive and well received. Despite the fact that the participants were extremely heterogeneous on sociodemographic factors, maltreatment history, current living situation, and cognitive, academic, emotional and behavioral functioning, there were important program main effects. The generalizability of the findings is also strengthened by the fact that participants did not self-select into the program (as is the case with most community-based mentoring programs in which participants sign up).

The study also demonstrates that it is possible to conduct a rigorous RCT with intent-to-treat analyses in a child welfare population, and to obtain information from multiple informants, including teachers. There are many barriers to conducting trials with a foster care population, including changes in legal guardianship, ongoing court processes, multiple system involvement, and the need to report all suspected maltreatment. The ability to conduct this important research speaks to the strength of the collaboration between researchers and participating counties. Despite all the challenges to program completion, all but 5 children who began the 9-month prevention program graduated. In addition, over 80% of those who either refused the prevention program or dropped out were interviewed at follow-up and included in intent-to-treat analyses. Success in recruitment and retention may be due to the fact that there were small cohorts as we developed and tested FHF. Such formative work is critical in the development of novel interventions, especially those at risk for iatrogenic effects.49 A full-scale efficacy trial is currently underway, which will enable us to test whether the program remains efficacious on a larger scale.

The study was not without limitations. Despite randomization, there were a few key variables on which the two groups differed at baseline. Although analyses controlled for these differences, there may have been other, unmeasured factors, which affected the baseline equivalence of groups. In addition, those lost to follow-up had lower IQs and more mental health problems than those interviewed, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Finally, the fact that children are in foster care presents some unique methodological challenges that may have influenced the results. Caregivers of children in foster care are not static, and some children had different caregivers at each of the three interview timepoints, while other children had the same caregiver. Because caregivers parented these children for variable amounts of time, their knowledge of the children’s current functioning and psychosocial histories varied greatly. To minimize the impact of the variability in caregiver familiarity with their children, which was not expected to differ between treatment conditions, the study asked questions of caregivers that focused on current functioning and recent mental health treatment. The addition of teacher reports, in which the informant is expected to vary each year, also mitigates concerns about reporter bias.

Despite study limitations, findings suggest that the FHF mentoring and skills group protocol holds promise and that future work examining program efficacy is warranted. Longer-term follow-up (currently underway) is needed to determine whether effects are sustained and/or whether new effects emerge. Despite the cluster of risks associated with maltreatment, including poverty, high-risk neighborhoods, parental psychopathology, substance use, and domestic violence, this study suggests that Fostering Healthy Futures promotes greater life satisfaction and better mental health functioning among maltreated youth placed in foster care. These are important findings given the dearth of evidence-based treatments for this vulnerable population. Although this study needs replication, it may be a promising model, not only for children in foster care, but for other high-risk youth populations as well.

Acknowledgement

Funding/Support: This project was principally supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (1 K01 MH01972, 1 R21 MH067618, and 1 R01 MH076919, H. Taussig, PI) and also received substantial funding from the Kempe Foundation, Pioneer Fund, Daniels Fund, and Children’s Hospital Research Institute.

Role of the Sponsor: The funding agencies were not involved in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or in the preparation of the data or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov, Identifier: NCT00809315

The child whose data were excluded from analyses was included in the non-interviewed group in attrition analyses.

Author Contributions: As principal investigator, Dr. Taussig had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Taussig, Culhane

Acquisition of data: Taussig, Culhane

Analysis and interpretation of data: Culhane, Taussig

Drafting of the manuscript: Taussig, Culhane

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Taussig, Culhane

Statistical analysis: Culhane, Taussig

Obtained funding: Taussig, Culhane

Study supervision: Taussig, Culhane

Financial Disclosures: None.

Additional Contributions: We wish to express our appreciation to the children and families who made this work possible and to the participating county departments of social services for their ongoing partnership in our joint clinical research efforts. We also thank David Olds, Ph.D. David MacKinnon, Ph.D. Edward Garrido, Ph.D. Tali Raviv, Ph.D. and Melody Combs, Ph.D. for insightful comments on drafts of this manuscript; Jennifer Koch-Zapfel, MSW, Dana Morgan, MSW, and Michel Holien, LCSW, for their recruitment efforts; Daniel Hettleman, Ph.D., Ann Petrila, LCSW, Rebecca Gennerman-Schroeder, LPC, and Robyn Wertheimer-Hodas, LCSW, for the development and implementation of the FHF program; and Dongmei Pan and Michael Knudson for conducting data analyses. Finally, this project would not have been possible without the work of the research assistants, project interviewers, interns/mentors, group leaders, and skills group assistants.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth and Families. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; Child Maltreatment 2007. 2009

- 2.U.S. Census Bureau. Washington, DC: Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2009. (128th ed) 2008 http://www.census.gov/prod/2008pubs/09statab/pop.pdf.

- 3.US Department of Health & Human Services: Administration on Children, Youth and Families. [Accessed June 29, 2009];The AFCARS Report Preliminary FY 2006 Estimates as of January 2008. 2009 http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/stats_research/afcars/tar/report14.htm.

- 4.Briere J. The APSAC handbook on child maltreatment. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1996. American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Child Welfare Information Gateway. [Accessed April, 2008];Long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect. 2008 http://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/factsheets/long_term_consequences.cfm.

- 6.Garland AF, Hough RL, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Wood PA, Aarons GA. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in youths across five sectors of care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001 Apr;40(4):409–418. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being. NSCAW No. 1: Who Are the Children in Foster Care? Research Brief, Findings from the NSCAW Study. [Accessed July, 2009]; http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre/abuse_neglect/nscaw/reports/children_fostercare/children_fostercare.html.

- 8.dosReis S, Zito JM, Safer DJ, Soeken KL. Mental health services for youths in foster care and disabled youths. Am J Public Health. 2001 Jul;91(7):1094–1099. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being. NSCAW No. 3: Children’s Cognitive and Socioemotional Development and their Receipt of Special Educational and Mental Health Services, Research Brief, Findings from the NSCAW Study. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre/abuse_neglect/nscaw/reports/spec_education/spec_education.html.

- 10.Halfon N, Berkowitz G, Klee L. Mental health service utilization by children in foster care in California. Pediatrics. 1992 Jun;89(6 Pt 2):1238–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harman JS, Childs GE, Kelleher KJ. Mental health care utilization and expenditures by children in foster care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000 Nov;154(11):1114–1117. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.11.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being. NSCAW One Year in Foster Care Wave 1 Data Analysis Report, Executive Summary. 2003 http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre/abuse_neglect/nscaw/reports/exesum_nscaw/exsum_nscaw.pdf.

- 13.Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test Manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corporation P. Wechsler Individual Achievement Test Screener. San Antonio, Tx: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hettleman D, Taussig H. Fostering Healthy Futures Skills Group Manual: a Unpublished manuscript. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Culhane SE, Taussig HN. Fostering Healthy Futures Mentor Manual: a Unpublished manuscript. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taussig HN, Culhane SE, Hettleman D. Fostering healthy futures: an innovative preventive intervention for preadolescent youth in out-of-home care. Child Welfare. 2007 Sep-Oct;86(5):113–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenberg MT, Kusche C. Promoting alternative thinking strategies. In: Elliot DS, editor. Book 10: Blueprints for Violence Series. Boulder, CO: Institute for Behavioral Science, University of Colorado, Boulder; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kusche CA, Greenberg MT. The PATHS curriculum: Promoting Alternative THinking Strategies. Seattle, WA: Developmental Research and Programs; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Children Cf. Second Step: A Violence Prevention Curriculum. Seattle: Committee for Children; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Briere J. Trama Symptom Checklist for Children - Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Achenbach TM. Integrative Guide for the 1991 CBCL/4–18, YSR, and TRF Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrews F, Withey S. Social Indicators of American's Perceptions of Life Quality. New York: Plenum; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dise-Lewis JE. The life events and coping inventory: an assessment of stress in children. Psychosom Med. 1988 Sep-Oct;50(5):484–499. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198809000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harter S. The Perceived Competence Scale for Children. Child Dev. 1982;53(1):87–97. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harter S. Manual for the Self-Perception Profile for Children. Denver, CO: University of Denver; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gifford-Smith M. [Accessed June, 2002];People in My Life. 2000 http://www.fasttrackproject.org.

- 28.Cook E, Greenberg M, Kusche C. People in My Life: Attachment Relationships in Middle Childhood; Paper presented at: Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Indianapolis, IN: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gifford-Smith M. [Accessed January 1, 2009];People in My Life: Grade 4, Year 5. 2000 http://www.childandfamilypolicy.duke.edu/fasttrack/techrept/p/pml/pml5tech.pdf.

- 30.Berliner L, Kolko D. What works in treatment for abused children. In: Kluger MP, Alexander G, Curtis PA, editors. What works in child welfare. Washington, DC: CWLA Press; 2000. pp. 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deblinger E, Stauffer LB, Steer RA. Comparative efficacies of supportive and cognitive behavioral group therapies for young children who have been sexually abused and their nonoffending mothers. Child Maltreat. 2001 Nov;6(4):332–343. doi: 10.1177/1077559501006004006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swenson C, Kolko D. Long-term management of the developmental consequences of child physical abuse. In: Reece RM, editor. Treatment of child abuse : common ground for mental health, medical, and legal practitioners. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2000. pp. 135–154. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhodes JE. Improving youth mentoring interventions through research-based practice. Am J Community Psychol. 2008 Mar;41(1–2):35–42. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts H, Liabo K, Lucas P, DuBois D, Sheldon TA. Mentoring to reduce antisocial behaviour in childhood. BMJ. 2004 Feb 28;328(7438):512–514. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7438.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGill D. Big Brothers Big Sisters of America. In: Elliot D, editor. Blueprints for Violence Prevention Book 2. Boulder, Colo.: Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence, University of Colorado at Boulder, Institute of Behavioral Science; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jekielek M, Moore K, Hair E, Scarupa H. Mentoring: A promising strategy for youth development. Washington, D.C.: Child Trends Research Brief; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keating LM, Tomishima MA, Foster S, Alessandri M. The effects of a mentoring program on at-risk youth. Adolescence. 2002 Winter;37(148):717–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rhodes JE, Grossman JB, Resch NL. Agents of change: pathways through which mentoring relationships influence adolescents' academic adjustment. Child Dev. 2000 Nov-Dec;71(6):1662–1671. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blechman EA, Maurice A, Buecker B, Helberg C. Can mentoring or skill training reduce recidivism? Observational study with propensity analysis. Prev Sci. 2000 Sep;1(3):139–155. doi: 10.1023/a:1010073222476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCord J. A pioneering longitudinal experimental study of delinquency prevention. In: McCord J, Tremblay RE, editors. Preventing antisocial behavior : interventions from birth through adolescence. xv. New York: Guilford Press; 1992. p. 391. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rhodes J, DuBois D. Understanding and facilitating the youth mentoring movement. Ann Arbor, MI: Society for Research in Child Development; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Royse D. Mentoring high-risk minority youth: evaluation of the Brothers project. Adolescence. 1998 Spring;33(129):145–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bernstein L, Dun Rappaport C, Olsho L, Hunt D, Levin M. Impact evaluation of the U.S. Department of Education's Student Mentoring Program - Executive Summary. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Institute, U.S. Dept. of Education; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiggins M, Bonell C, Burchett H, Austerberry H, Allen E, Strange V. Young People's Development Programme evaluation: Final Report. London, England: University of London with the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernandes A. Congressional Research Service; CRS Report for Congress: Vulnerable Youth: Federal Mentoring Programs and Issues. 2008 January 4;

- 46.Heard M, Rhodes J. Testimony for the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies: Departments of Education and Health and Human Services, Corporation for National and Community Service May 18, 2009. [Accessed July, 2009];2009 http://www.mentoring.org/downloads/mentoring_1213.pdf.

- 47.Sherrod L, editor. Understanding and facilitating the youth mentoring movement. Ann Arbor, MI: Society for Research in Child Development; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 48.DuBois DL, Holloway BE, Valentine JC, Cooper H. Effectiveness of mentoring programs for youth: a meta-analytic review. Am J Community Psychol. 2002 Apr;30(2):157–197. doi: 10.1023/A:1014628810714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olds DL, Sadler L, Kitzman H. Programs for parents of infants and toddlers: recent evidence from randomized trials. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007 Mar-Apr;48(3–4):355–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]