Abstract

On April 1, 2007, Alberta became the first province in Canada to introduce cystic fibrosis (CF) to its newborn screening program. The Alberta protocol involves a two-tier algorithm involving an immunoreactive trypsinogen measurement followed by molecular analysis using a CF panel for 39 mutations. Positive screens are followed up with sweat chloride testing and an assessment by a CF specialist. Of the 99,408 newborns screened in Alberta during the first two years of the program, 221 had a positive CF newborn screen. The program subsequently identified and initiated treatment in 31 newborns with CF. A relatively high frequency of the R117H mutation and the M1101K mutation was noted. The M1101K mutation is common in the Hutterite population. The presence of the R117H mutation has created both counselling and management dilemmas. The ability to offer CF transmembrane regulator full sequencing may help resolve diagnostic dilemmas. Counselling and management challenges are created when mutations are mild or of unknown clinical significance.

Keywords: CFTR, Cystic fibrosis, Newborn screening

Abstract

Le 1er avril 2007, l’Alberta est devenue la première province canadienne à inclure la fibrose kystique (FK) dans son programme de dépistage du nouveau-né. Le protocole de l’Alberta comporte un algorithme en deux volets alliant une mesure du trypsinogène immunoréactif suivie d’une analyse moléculaire faisant appel à 39 mutations de FK. Les dépistages positifs sont suivis d’un test à la sueur et d’une évaluation par un spécialiste de la FK. Des 99 408 nouveau-nés ayant fait l’objet d’un test de dépistage en Alberta pendant les deux premières années du programme, 221 ont obtenu des résultats positifs au dépistage néonatal de la FK. Le programme a ensuite permis de repérer et d’amorcer un traitement chez 31 nouveau-nés atteints de FK. On a remarqué une fréquence relativement élevée des mutations R117H et M1101K. La mutation M1101K est courante au sein de la population huttérienne. La présence de la mutation R117H a créé à la fois des dilemmes de counseling et de prise en charge. La capacité d’offrir un séquençage complet de la régulation transmembranaire de la fibrose kystique pourrait contribuer à résoudre les dilemmes diagnostiques. Les défis liés au counseling et à la prise en charge se produisent en cas de mutations légères ou de signification clinique inconnue.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive condition caused by mutations in the CF transmembrane regulator (CFTR) gene. It is widely recognized that CF is a variable condition that may affect the respiratory tract, pancreas, intestine, male genital tract, hepatobiliary system and exocrine sweat glands, resulting in complex multisystem disease. It is the most common life-limiting autosomal recessive disorder in the Caucasian population, with an incidence of 1:3200 live births. CF occurs with lower frequency in other ethnic and racial populations (1:15,000 in African Americans and 1:31,000 in Asian Americans) (1).

Newborn screening for CF is becoming more prevalent based on improved health outcomes of children diagnosed through these programs (1). Individuals with CF detected by newborn screening programs have improved nutritional status, better growth, improved lung function and fewer hospitalizations (2,3). Medical costs are also reduced due to decreased hospitalizations and diagnostic costs (2).

Alberta was the first Canadian province to add CF to its newborn screening program.

Following a one-year CF newborn screening pilot study, the provincial government established an expert panel who recommended the introduction of expanded newborn screening (4,5). As of April 1, 2007, newborns born in Alberta are screened for 16 metabolic and endocrine disorders, in addition to CF. We will describe the Alberta protocol and our experience during the first two years of CF newborn screening.

METHODS

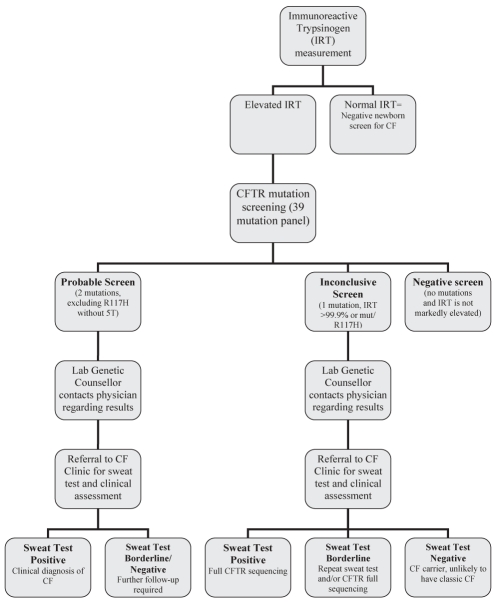

The Alberta CF newborn screening protocol involves a two-tier algorithm involving an initial immunoreactive trypsinogen (IRT) measurement followed by molecular analysis of samples with elevated IRT values. Subsequent sweat chloride testing and clinical assessment are performed when indicated (Figure 1).

Figure 1).

Alberta cystic fibrosis (CF) newborn screening protocol. 5T 5 thymine; CFTR CF transmembrane regulator; Lab Laboratory; mut Mutation

Tier 1: IRT

IRT from dried blood spots was initially measured from April 2007 to February 2008, using the manual DELFIA Neonatal IRT Kit (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Finland), and from March 2008 using the AutoDELFIA Neonatal IRT Kit (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences). The assay is a solid-phase, two-site fluoroimmunometric assay based on the direct sandwich technique, in which two monoclonal antibodies are directed against two separate antigenic determinants of the IRT molecule.

Initially, samples with IRT concentrations above the 98th percentile of each daily run were referred to the Alberta Health Services Molecular Diagnostic Laboratory (MDL; Edmonton) for CFTR mutation analysis. This was modified for two reasons. First, IRT concentration is dependent on the patient’s age at sample collection. For samples collected between 24 h and 30 h of age, the 98th percentile cut-off for IRT was 65.1 μg/L, while for samples collected between 31 h and 160 h of age, the 98th percentile cut-off for IRT was 60.2 μg/L. Second, daily runs incorporating a large number of newborns from the neonatal intensive care unit had a higher 98th percentile value. The current algorithm uses the 98th percentile cut-off; however, CFTR mutation analysis is performed on any sample with an IRT greater than 60 μg/L.

Tier 2: DNA

Blood spot DNA extraction:

DNA extraction from the newborn screen card is performed using the Generation Capture Card Kit (QIAGEN Inc, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. A 3 mm disk is punched from the blood spot card; DNA is then extracted from this punched spot. The immobilized DNA is washed multiple times, and then eluted and used for polymerase chain reaction amplification and mutation detection.

Mutation testing

Mutation identification is performed using the Tag-It Cystic Fibrosis Kit (Luminex Molecular Diagnostics Inc, USA), which simultaneously screens for the 23 CFTR gene mutations, as recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in 2004, plus 16 of the world’s most common and North American-prevalent mutations. These include the following mutations: delF508, I507del, G542X, G85E, R117H, 621+1G→T, 711+1G→T, G551D, R334W, R347P, A455E, 1717-1G→A, R560T, R553X, N1303K, 1898+1G→A, 2184delA, 2789+5G→A, 3120+1G→A, R1162X, 3659delC, 3849+10kbC→T, W1282X, 1078delT, 394delTT, Y122X, R347H, V520F, A559T, S549N, S549R, 1898+5G→T, 2183AA→G, 2307insA, Y1092X, M1101K, S1255X, 3876delA and 3905insT. If indicated, testing includes reflex analysis for the following variants: 5/7/9T exon 9 splice acceptor tracts, F508C, I507V and I506V. Molecular analysis of parents is recommended when R117H and 5 thymine (5T) are identified to assess phase. When required, full screening of the CFTR gene is performed by forward and reverse sequencing the entire coding region and flanking intron boundaries (primers available on request). Detection of deletions and duplications is performed using the multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification assay (MRC-Holland), and all positives are confirmed using TaqMan (Applied Biosystems, USA) real-time polymerase chain reaction.

Interpretation of positive screens

CF-positive newborns are reported as having either an inconclusive screen or probable CF. Newborns are reported to have an inconclusive screen if they fall into one of the following three categories: an elevated IRT and one mutation; a markedly elevated IRT and no mutations; or an elevated IRT and two mutations, in which the second mutation is R117H without 5T. Newborns with an elevated IRT and two mutations (excluding R117H without 5T) are reported as having probable CF. A genetic counsellor, employed within the MDL, contacts the ordering or family physician indicated on the newborn screen card to discuss each positive result. The newborns are generally three to four weeks of age when the results are reported to the physician. The ordering or family physician is then responsible for contacting the family and referring the child to one of the two CF clinics in Alberta (Edmonton or Calgary) for sweat chloride testing and clinical assessment.

Follow-up for newborns with positive screens

All newborns with a probable or inconclusive CF screen are referred for sweat chloride testing at one of two sweat chloride laboratories in Alberta. Sweat chloride testing is generally performed when infants are between four and six weeks of age. Sweat chloride concentrations are considered to be normal when they are lower than 30 μmol/L, borderline when they are between 30 μmol/L and 60 μmol/L, and abnormal when they are greater than 60 μmol/L.

A clinical assessment is completed by the CF team the same day that the sweat chloride testing is performed. Sweat chloride results are reported to the family by the CF team either the same day or the following day. Newborns with an abnormal sweat test result are closely followed by one of the two CF teams. Newborns with one mutation and an abnormal or borderline sweat chloride test have blood drawn for full screening of the CFTR gene by the MDL genetic counsellor. Routine paediatric care is recommended for newborns with a negative sweat chloride test and one mutation. Clinical follow-up data are subsequently reported back to the newborn screening program by the CF teams.

Genetic counselling, through one of the two medical genetics clinics in Alberta, is offered to the parents of all newborns with a positive CF screen. This generally takes place at a later date. Genetic counselling is also available to extended family members. If the family lives outside of one of the two major centres, the genetic counselling session can be conducted via telemedicine.

RESULTS

Between April 1, 2007 and March 31, 2009, 99,408 newborns born in Alberta had newborn screening performed. Of those, 2555 (2.58%) newborns had an elevated IRT value. Two hundred twenty-one newborns (8.6%) screened positive following molecular analysis. In total, 247 mutant alleles were identified. The mutation frequency is described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Mutation frequency

| Mutation name | Number of times detected (247 total mutations) | Frequency, % | Expected, % (reference) |

|---|---|---|---|

| delF508* | 156 | 63.2 | 68.6 (1) |

| R117H* | 36 | 14.6 | 0.7 (1) |

| G551D* | 11 | 4.5 | 2.1 (1) |

| 3849+10kbC→T* | 6 | 2.4 | 0.7 (1) |

| M1101K | 5 | 2.0 | Undetermined (1) |

| G542X* | 4 | 1.6 | 2.4 (1) |

| 1717-1G→A* | 4 | 1.6 | 0.7 (1) |

| 621+1G→T* | 3 | 1.2 | 0.9 (1) |

| 3120+1G→A* | 3 | 1.2 | 1.5 (1) |

| G85E* | 2 | 0.8 | 0.3 (1) |

| A455E* | 2 | 0.8 | 0.2 (1) |

| R553X* | 2 | 0.8 | 0.9 (1) |

| 2789+5G→A* | 2 | 0.8 | 0.3 (1) |

| ΔI507* | 1 | 0.4 | 0.3 (1) |

| 711+1G→T* | 1 | 0.4 | 0.1 (1) |

| R334W* | 1 | 0.4 | 0.2 (1) |

| N1303K* | 1 | 0.4 | 1.3 (1) |

| 1898+1G→A* | 1 | 0.4 | Undetermined (1) |

| 2184delA* | 1 | 0.4 | 0.1 (1) |

| 394delTT | 1 | 0.4 | Undetermined (1) |

| R347H | 1 | 0.4 | 0.2 (4) |

| V520F | 1 | 0.4 | 0.2 (4) |

| S549N | 1 | 0.4 | 0.1 (1) |

| 2307insA | 1 | 0.4 | 0.2 (1) |

| R347P* | 0 | 0 | 0.2 (1) |

| R560T* | 0 | 0 | 0.2 (1) |

| R1162X* | 0 | 0 | 0.2 (1) |

| 3659delC* | 0 | 0 | 0.2 (1) |

| W1282X* | 0 | 0 | 1.4 (1) |

| 1078delT | 0 | 0 | 0.03 (2) |

| Y122X | 0 | 0 | Undetermined (3) |

| A559T | 0 | 0 | 0.2 (1) |

| S549R | 0 | 0 | Undetermined (1) |

| 1898+5G→T | 0 | 0 | Undetermined (1) |

| 2183AA→G | 0 | 0 | 0.1 (1) |

| Y1092X | 0 | 0 | Undetermined (1) |

| S1255X | 0 | 0 | 0.2 (1) |

| 3876delA | 0 | 0 | Undetermined (4) |

| 3905insT | 0 | 0 | 0.12 (1) |

American College of Medical Genetics-recommended mutations

During the first two years of the program, 198 newborns had an inconclusive screen including 191 newborns with one mutation, two newborns with markedly elevated IRTs and five newborns with R117H/delF508 genotypes (Table 2). One hundred eighty-one newborns (91%) had normal sweat chloride analysis and were unaffected. The two newborns with markedly elevated IRTs had negative sweat chloride tests: one baby had a pancreatic cyst and the second had necrotizing enteritis. Eight newborns were diagnosed with CF based on a combination of the sweat test results, clinical findings and CFTR full sequencing results.

TABLE 2.

Positive cystic fibrosis newborn screen summary

| Screen result | Unaffected | Affected | Further follow-up required | Lost to follow-up | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probable screen | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 23 |

| Inconclusive screen | |||||

| One mutation | 179 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 191 |

| Markedly elevated IRT | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| R117H/F508del | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Total | 181 | 31 | 7 | 2 | 221 |

Data presented as n. IRT Immunoreactive trypsinogen

Six newborns had R117H in conjunction with a second CF mutation. In all cases, the second mutation was delF508. Five of the newborns had delF508/R117H without 5T and, therefore, were reported as having an inconclusive screen for CF. These newborns had negative or borderline sweat chloride test results (Table 3). One baby had delF508/R117H+5T and was treated as a probable case.

TABLE 3.

F508del/R117H cases

| ID number | Mutation status | Sweat test result(s), μmol/L | Other clinical information |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24827 | F508del/R117H | 28 | None |

| 23726 | F508del/R117H | 36/insufficient/20 | Fecal elastase normal |

| 22578 | F508del/R117H | 10 | None |

| 24500 | F508del/R117H | 34/insufficient | None |

| 18527 | F508del/R117H | 29 | None |

| 23317 | F508del/R117H+5T | 47/62 | Affected sibling |

5T 5 thymine

There were 23 newborns with probable screens. All were confirmed to be affected.

Thirteen newborns (57%) were delF508 homozygotes. Eight newborns (35%) were compound heterozygotes – one of the mutations was F508del including the baby with delF508/R117H+5T described above. One baby (4%) was a M1101K homozygote, and one was a compound heterozygote V520F/1898+1G→A.

Full CFTR screening, which includes both sequencing and dosage analysis and has a 98% detection rate, was offered to newborns with one mutation and a positive or multiple borderline sweat chloride tests. Of the newborns with inconclusive screens, four had positive sweat chloride tests. Full CFTR screening was performed on three of those newborns and a second CFTR mutation was identified (Table 4). The fourth baby did not have a full CFTR screening, but had a clinical diagnosis of CF based on a sweat chloride of 110 μmol/L, poor growth and persistent cough. One baby with a family history of CF was diagnosed prenatally. An affected sibling was identified as having F508del/G458V after CFTR full sequencing. The family declined sweat testing based on the family history and prenatal test results. In addition, the baby underwent newborn screening and had an elevated IRT.

TABLE 4.

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator full screen results for inconclusive cases with borderline and elevated sweat chloride results

| ID | Sweat chloride, μmol/L | IRT, μg/L | 1st mutation | 2nd mutation | Mutation description (reference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14920 | 67/72 | 194 | F508del | D110H | Associated with mild or atypical CF (5) |

| 14490 | 105 | 271 | F508del | W1204X | Rare but associated with classic CF (6) |

| 15810 | 95 | 162 | 1717G→A | Exon 2–3 del | Associated with classic CF (7) |

| 17167 | 110 | 178 | F508del | Not sequenced | N/A |

| 15905 | 40 | 94 | 3849+10kb | 2789+1G→A | Not previously reported. Predicted splice site mutation |

| 14780 | 35 | 69 | F508del | R352W | Rare, no clinical data published |

| 17316 | 53/35 | 74 | F508del | L206W | Variable, ranging from classic CF to isolated CBAVD (8) |

| 16053 | 26/62 | 72 | F508del | 5T | Associated with atypical CF and CBAVD (9) |

| 21739 | N/A | 98 | F508del | G458V | Associated with classic CF (17) |

| 16229 | 31/32 | 62 | F508del | – | N/A |

| 16369 | 38/48 | 79 | 711+G→T | – | N/A |

| 12468 | NSQ/30 | 103 | F508del | – | N/A |

5T 5 thymine; CBAVD Congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens; CF Cystic fibrosis; IRT Immunoreactive trypsinogen; N/A Not available; NSQ Not sufficient quantity

Seven newborns were found to carry one mutation with one or more borderline sweat chloride tests. All seven underwent CFTR full sequencing. A second mutation was identified in three cases and 5T was identified in one case. In three cases, a second mutation was not identified (Table 4).

One baby had an elevated IRT of 144 μg/L (greater than the 99.9 percentile), but no mutation was detected and, thus, was reported as a negative screen. This baby was subsequently diagnosed with CF at six months of age. The baby suffered from failure to thrive and was referred to a gastroenterologist who ordered CFTR full screening. The full screening identified two rare mutations and a diagnosis of CF was confirmed. Since then, a protocol for markedly elevated IRTs (greater than the 99.9 percentile) has been put in place. A baby with an IRT level equal to or greater than 133 μmol/L is reported as having an inconclusive screen for CF, even if no mutations are detected.

DISCUSSION

Alberta was the first province in Canada to introduce newborn screening for CF. In the first two years of the Alberta CF newborn screening program, 0.2% of the newborns screened were positive for CF with either inconclusive or probable screens. From the 39 mutation panel, we identified 24 different mutations. The individual frequency of those mutations was as expected, apart from R117H, which was more common in our study population. We also reported a 2% mutation frequency for the M1101K mutation.

The relatively high frequency of M1101K was expected based on the Hutterite population in Alberta. This mutation is believed to account for 69% of mutations in the Hutterite population (6). Hutterites are a group of German-speaking communal farmers that represent a genetic isolate within Alberta with an increased incidence of CF.

The overall frequency of the R117H mutation in our sample population appears to be higher than previously reported in the literature. The R117H mutation is known to be modified by the length of the polythymine tract in intron 8. When this mutation is in cis with 5T, it acts as a classic or severe CF mutation. Whereas, when R117H is in cis with 7T or 9T, it is believed to act as a mild mutation and is associated primarily with congenital absence of the vas deferens or atypical adult-onset CF. The frequency of R117H in the literature varies from 0.5% to 0.7% of CF mutations (3,7–9). In our population of screen-positive newborns, the frequency of R117H was 36 of 247 mutations (14.6%). In six of 36 cases, a second CFTR mutation was detected and in 30 of 36 cases, the baby carried only the R117H mutation, with or without 5T.

Other newborn screening programs also report a high frequency of R117H in newborns with two CFTR mutations. The frequency of an R117H mutation in newborns with two CFTR mutations ranges from 7.2% in France, to 8% in Massachusetts (USA), to 26.7% in Wisconsin (USA) (2,10,11). Before newborn screening, most individuals underwent molecular testing because they were symptomatic and the mutation frequencies reported in the literature were based on CF patient samples. Due to milder or absent phenotype, individuals with the R117H mutation may be underdiagnosed and the mutation frequency may be under-represented.

Newborns with a genotype involving a known disease-causing mutation and R117H create counselling and management dilemmas. We identified five newborns with a F508del/R117H genotype in the absence of 5T. All infants had normal or borderline sweat chloride results and no obvious clinical symptoms of CF. The literature suggests that these children are unlikely to have classic CF, although pulmonary symptoms have been reported (12). In addition, there have been a number of reported cases in which Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections have been identified in children with this genotype (13). Congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens is also associated with the combination of a severe mutation and R117H. Unfortunately, it is not possible to offer precise outcome predictions, which is difficult to convey to families. Currently, there is no consensus on how to manage children with a F508del/R117H genotype. Because the presence of CF disease in this population is unclear, our program follows these children annually with a chest x-ray, a throat swab and an assessment by a CF specialist. The goal is to identify and treat any concerns, as early as possible, without stigmatizing the children and their families. There has been debate in the literature regarding the inclusion of R117H in newborn screen. Some authors suggest that is it unethical to include such a mild mutation (14). Other authors argue that it has yet to be determined whether these patients are truly asymptomatic over the long term (15).

Newborns with one mutation and borderline or positive sweat chloride tests also present a diagnostic dilemma. Although not part of the newborn screening program, full CFTR sequencing is clinically available to these families. We identified a second mutation in seven of 10 newborns, including two mutations that are associated with classic childhood onset CF (W1204X and Exon 2–3 deletion). Three mutations (D110H, L206W and 5T) were identified that are associated with a mild or variable phenotype. Two mutations (2789+1 G→A and R352W) were also identified for which no published information on clinical phenotype was available. These cases also presented challenges because we were unable to predict clinical outcome for these children. The parents of the three newborns in whom a second mutation was not identified were told that their children were unlikely to develop classic CF. The combination of sequencing and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification assay can detect greater than 98% of CFTR mutations; thus, this testing is able to provide important diagnostic information for many newborns (16).

The Alberta newborn screening program has been successful – it has identified and initiated treatment for 31 newborns with CF. It is too early to determine the specificity and sensitivity of the program. We have already identified one baby with CF who was missed by the newborn screening program. It is possible that other newborns have been missed, but may have yet to develop symptoms and present to a physician. Continual tracking of outcomes through the CF newborn screening program is required to determine, in the long term, whether the program is able to identify most, if not all, newborns with classic CF. The first two years of the program have also highlighted several counselling and management challenges, which are being subjected to continued study and follow-up.

REFERENCES

- 1.Giusti R, Badgwell A, Iglesias AD, New York State Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening Consortium The first 2.5 years of experience with cystic fibrosis newborn screening in an ethnically diverse population. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e460–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comeau AM, Accurso FJ, White TB, et al. Guidelines for implementation of cystic fibrosis newborn screening programs: Cystic fibrosis foundation workshop report. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e495–e518. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bobadilla JL, Macek M, Jr, Fine JP, Farrell PM. Cystic fibrosis: A worldwide analysis of CFTR mutations – correlation with incidence data and application to screening. Hum Mutat. 2002;19:575–606. doi: 10.1002/humu.10041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borowski HZ, Brehaut J, Hailey D. Linking evidence from health technology assessments to policy and decision making: The Alberta model. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2007;23:155–61. doi: 10.1017/S0266462307070250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ball CL, Montgomery MD, Bridge PJ, Lyon ME. Evaluation of the quantase neonatal immunoreactive trypsinogen (IRT) screening assay for cystic fibrosis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43:570–2. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2005.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zielenski J, Fujiwara TM, Markiewicz D, et al. Identification of the M1101K mutation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene and complete detection of cystic fibrosis mutations in the Hutterite population. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52:609–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heim RA, Sugarman EA, Allitto BA. Improved detection of cystic fibrosis mutations in the heterogeneous U.S. population using an expanded, pan-ethnic mutation panel. Genet Med. 2001;3:168–76. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200105000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watson MS, Cutting GR, Desnick RJ, et al. Cystic fibrosis population carrier screening: 2004 revision of American College of Medical Genetics Mutation Panel. Genet Med. 2004;6:387–91. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000139506.11694.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strom CM, Crossley B, Redman JB, et al. Cystic fibrosis screening: Lessons learned from the first 320,000 patients. Genet Med. 2004;6:136–40. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000127268.65149.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munck A, Sahler C, Briard M, Vidailhet M, Farriaux JP. Cystic fibrosis: The French neonatal screening organization, preliminary results. Arch Pediatr. 2005;12:646–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2005.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rock MJ, Hoffman G, Laessig RH, Kopish GJ, Litsheim TJ, Farrell PM. Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis in Wisconsin: Nine-year experience with routine trypsinogen/DNA testing. J Pediatr. 2005;147:S73–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Massie RJ, Poplawski N, Wilcken B, Goldblatt J, Byrnes C, Robertson C. Intron-8 polythymidine sequence in Australasian individuals with CF mutations R117H and R117C. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:1195–200. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00057001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parad RB, Comeau AM. Diagnostic dilemmas resulting from the immunoreactive trypsinogen/DNA cystic fibrosis newborn screening algorithm. J Pediatr. 2005;147:S78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scotet V, Audrezet MP, Roussey M, et al. Immunoreactive trypsin/DNA newborn screening for cystic fibrosis: Should the R117H variant be included in CFTR mutation panels? Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1523–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehta A. A global perspective on newborn screening for cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2007;13:510–4. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3282f01136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strom CM, Huang D, Chen C, et al. Extensive sequencing of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator gene: Assay validation and unexpected benefits of developing a comprehensive test. Genet Med. 2003;5:9–14. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200301000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuppens H, Teng H, Raeymaekers P, et al. CFTR haplotype backgrounds on normal and mutant CFTR genes. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:607–14. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.4.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]