Abstract

Double fertilization in angiosperms involves several successive steps, including guidance and reception of the pollen tube and male-female gamete recognition. Each step entails extensive communication and interaction between two different reproductive cell or tissue types. Extensive research has focused on the pollen tube, namely, its interaction with the stigma and reception by maternal cells. Little is known, however, about the mechanism by which the gametes recognize each other and interact to form a zygote. We report that an ankyrin repeat protein (ANK6) is essential for fertilization, specifically for gamete recognition. ANK6 (At5g61230) was highly expressed in the male and female gametophytes before and during but not after fertilization. Genetic analysis of a T-DNA insertional mutant suggested that loss of function of ANK6 results in embryonic lethality. Moreover, male-female gamete recognition was found to be impaired only when an ank6 male gamete reached an ank6 female gamete, thereby preventing formation of homozygous zygotes. ANK6 was localized to the mitochondria, where it interacted with SIG5, a transcription initiation factor previously found to be essential for fertility. These results show that ANK6 plays a central role in male-female gamete recognition, possibly by regulating mitochondrial gene expression.

Keywords: ovule development, σ-factor, mitochondrial protein

Double fertilization, which produces both embryo and endosperm, is a unique feature in the life cycle of angiosperms. Several major successive steps, including pollen tube guidance, pollen tube reception by the ovule, and male-female gamete recognition, entail intricate communication and interaction between two different reproductive cell or tissue types of the parents (reviewed in refs. 1, 2). In recent years, progress has been made in identifying the genes and signals important for the initial step of this process (reviewed in refs. 3, 4). Thus, several proteins were found to be essential for guidance of the pollen tube, such as POP2, a transaminase that controls GABA level in flora (5); MYB98, a synergid cell-expressed transcriptional factor (6); ZmEA1, a small diffusible protein that is expressed in both egg and synergid cells in maize (7); and CCG, a central cell-expressed transcriptional factor (8). Long-range and local signals arising from the female sporophytic and gametophytic tissues appear to regulate this process (3, 9). Some small secreted polypeptide (members of cysteine-rich defensin-like proteins) were recently identified in Torenia fournieri as a pollen tube attractant secreted from specialized cells of the female gametophyte, the synergids, thus providing direct evidence for a role in guiding the pollen tube (10).

Several genes and mutants have also been identified and linked to the next phase, pollen tube reception by the ovule. A female-specific mutant, feronia (fer) or sirene (11, 12), was found to be defective in pollen tube reception. FERONIA/SIRENE encodes a synergid-expressed, plasma membrane-localized, receptor-like kinase (13). Two other female gametophytic Arabidopsis mutants, lorelei and scylla, have also been shown to be specifically defective in pollen tube reception (14, 15). Interestingly, disruption of two FERONIA/SIRENE homologs, ANXUR1 and ANXUR2, expressed in pollen, triggered pollen tube discharge before its arrival at the egg apparatus (16, 17). Further, a loss-of-function mutant, amc (abstinence by mutual consent), exhibited a pollen tube-invading phenotype very similar to that observed for the fer/sirene mutants. The amc mutant differed from fer/sirene, however, in that the defect appeared only when the pollen tube from an amc pollen grain encountered an amc embryo sac (18). AMC encodes a peroxin essential for protein import into peroxisomes.

In contrast to pollen tube guidance and reception, little is known about the mechanism whereby male and female gametes are recognized in the fertilization process. Studies showed that GCS1/HAP2, a sperm-specific protein from Lilium longiflorum, accumulates during late gametogenesis and is important in gamete fusion (19, 20). Further study showed that the N terminus of GCS1/HAP2 interacts with several proteins expressed in female gametes, whereas the positively charged C terminus may anchor itself to the plasma membrane through electrostatic interactions with other membrane proteins in the sperm (21). The mechanism of action of GCS1/HAP2 is not known, however, and other players need to be identified to understand the gamete recognition and fusion processes.

In exploring factors involved in double fertilization, we uncovered a role for ankyrins in male-female gamete recognition. Ankyrins are characterized by a widely occurring repeat motif of 33 amino acid residues (22) and are believed to act in protein-protein interactions (23–25). We show that the mutant in an ankyrin repeat gene, ANK6, has a phenotype in that it impairs male-female gamete recognition. Specifically, the development of homozygous mutant individuals was prevented when an ank6 mutant male gamete reached an ank6 female gamete. An ankyrin repeat protein, ANK6, was further linked to SIG5, a putative transcriptional regulator in mitochondria, suggesting that these two proteins jointly play an essential role in gamete recognition in the double-fertilization process, presumably by controlling the expression of genes important for the process.

Results and Discussion

ANK6 Is Highly Expressed in Both Male and Female Gametophytes.

To understand the function of ankyrins in reproduction, we analyzed the microarray database of Arabidopsis ANKs (http://www.bar.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi) and selected ANKs that were preferentially expressed in both male and female gametophytes for further analysis. ANK6 was one of the candidates that could be involved in the reproduction process.

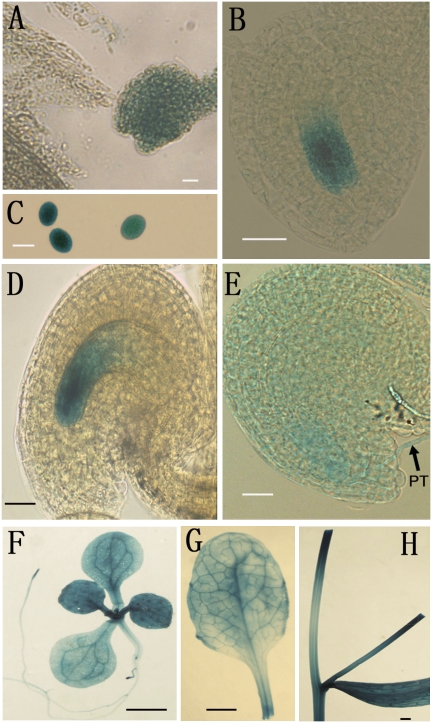

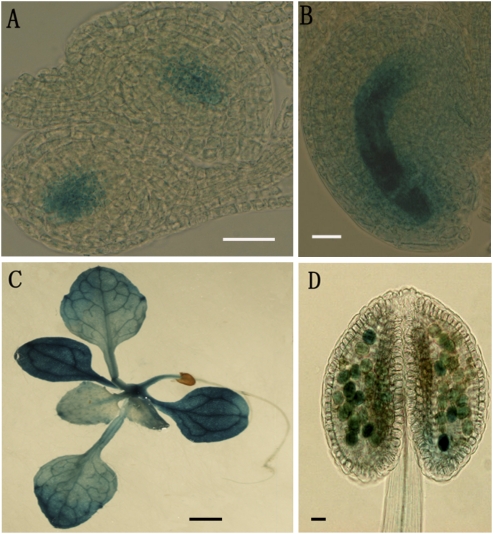

To confirm the expression pattern of ANK6, GUS reporter assays were performed in transgenic plants harboring a PromoterANK6-GUS reporter construct. Strong GUS activity was detected not only in pollen grains and pollen tubes of T2 transgenic lines but also in the female gametophyte, particularly in the synergids, egg cell, and central cell of the mature female gametophyte (Fig. 1 A–E). After fertilization, GUS activity began to decrease in fertilized ovules, and it eventually became undetectable at the stage before the first division of the endosperm. This expression pattern was consistent with a function in the development of mature male and female gametophytes as well as in fertilization. GUS activity was also detected in vegetative tissues, including leaves, stems, and roots (Fig. 1 F–H).

Fig. 1.

Expression patterns of ANK6 by GUS reporter analysis. Histochemical GUS staining of ovules from plants transformed with ANK6 promoter-GUS. GUS activities (indicated in blue) were observed at different developmental stages of male (C) and female (A, B, D, and E) gametophytes. GUS signals were also detectable in leaves (F and G), roots (F), and stems (H). Early one-nucleate embryo sac (A), FG1 stage (B), mature pollen (C), mature ovule (D), ovule with penetrating pollen tube (PT, arrow) (E), 2-wk-old plant (F), mature leaf (G), and mature stem (H) are shown. (Scale bars: A–E, 20 μm; F–H, 0.5 cm.)

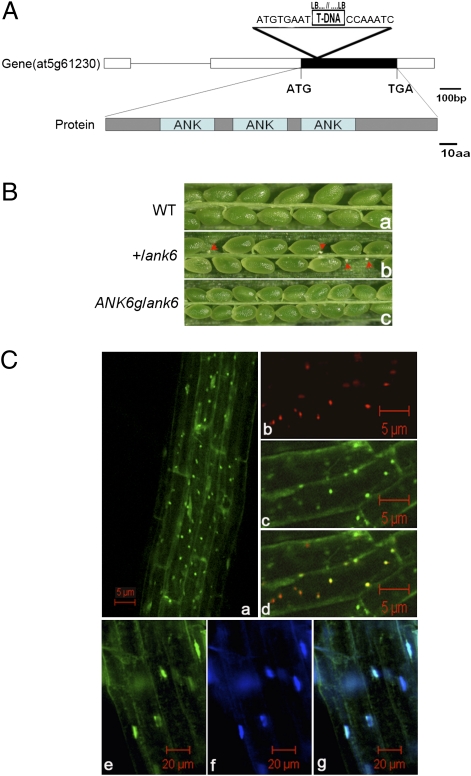

ANK6 T-DNA Insertion Mutant Displayed Empty Seed Set in the Siliques.

A T-DNA insertion mutant (SALK_043831) in ANK6 was obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center. The insertion site was mapped to the +168 nucleotide relative to the +1 translation start codon (ATG) (Fig. 2A). Genotyping of T2 plants obtained led to the identification of several heterozygous +/ank6 mutant plants, but no homozygous mutant seedlings were obtained in the progeny of selfed +/ank6 plants. Moreover, the heterozygous +/ank6 plants had unfertilized shriveled ovules significantly smaller than the developing seeds next to them (Fig. 2 B, b; arrowheads), suggesting that gametophyte or embryo development may have been defective when ANK6 function was disrupted. Because only a single T-DNA insertion line was available, we performed genetic complementation by introducing a functional gene cassette [pCAMBIA 1300 (pCAMBIA)-PANK6-cDNA-TANK6 construct; Materials and Methods and Table S2] into heterozygous +/ank6 mutant plants. In the T2 populations, 5 of 28 independent lines tested were homozygous for both the ank6 allele and the ANK6 transgene. In all T3 progenies of these five lines, silique seed sets were fully restored to the WT level (Fig. 2 B, c), demonstrating that the ANK6 transgene fully complemented the ank6 reduced seed set phenotype.

Fig. 2.

Phenotypic analysis of ank6 and subcellular localization of ANK6 protein. (A) ANK6 gene organization, protein structure, and position of T-DNA insert. The ATG start codon and TGA stop codon are indicated. A T-DNA insertion (triangle above the gene diagram) was detected in the exon by PCR and DNA sequencing of the PCR-amplified products. (B) In contrast to WT (B, a), a silique of self-pollinated +/ank6 plants showed unfertilized ovules (B, b; arrowheads), whereas a silique of complemented transgenic plants showed the WT phenotype (B, c). (C) ANK6-GFP protein (green) is localized both in mitochondria (C, d) and nuclei (C, g) using organelle-specific dyes as markers. Overview of GFP signals (C, a), mitochondria stained with the MitoTracker (red) (C, b), ANK6-GFP (green) (C, c), merged image of C, b and C, c (yellow) (C, d), nuclei stained with nuclear DNA-specific dye Hoechst 33258 (blue) (C, f), ANK6-GFP (green) (C, e), and merged image of C, e and C, f (C, g).

Compared with WT plants, self-pollinated heterozygous +/ank6 siliques yielded about 31.6% randomly located white shriveled ovules, suggesting a likely defect in gametophyte function. Within +/ank6 progeny, the segregation of the ank6 allele was analyzed by PCR-based genotyping, yielding a 2.01:1.00 ratio of heterozygous-to-WT in the progeny of self-pollinated F2 plants (n = 220) (Table S1), which is consistent with an embryonic lethality defect (χ2 = 0.0022, 0.95 < P < 0.975). No homozygous ank6 seedlings were detected. Segregation of Kanr analyzed in the progeny of eight self-pollinated heterozygous +/ank6 plants showed a 1.96:1.00 ratio of Kanr to Kans in the F2 generation (n = 764), which is, again, consistent with the ratio of embryonic lethality defect shown above (χ2 = 0.066, 0.75 < P < 0.90). This ratio suggested that the distorted segregation is most likely caused by a lethal mutation that affects embryo viability. The absence of homozygous plants, the seed set phenotype, and the distorted segregation ratio occurred after four successive backcrosses. Further, all kanamycin-resistant plants (n > 400) exhibited the incomplete seed set phenotype.

Although the segregation ratio observed in the mutants was close to the expected distortion for embryo lethality in homozygous mutation, it does not exclude the possibility that both genders were partially affected. Reciprocal crosses were thus performed to investigate whether the mutation affects male or female gametophyte function. Reciprocal crosses with WT plants showed 100% transmission efficiency of the ank6 gene through the male (n = 285; χ2 = 0.0035, P > 0.05) and 82% transmission efficiency through the female (n = 449; χ2 = 4.312, 0.025 < P < 0.05), indicating that the mutation slightly affected female but not male gametophyte development (Table S1).

ANK6 Is Localized in Mitochondria and Nucleus.

ANK6 encodes a 174-aa protein that, according to the SMART protein domain prediction program (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/), has three ankyrin repeat motifs at the N terminus (amino acid residues 28–129) and contains an atypical mitochondrial localization peptide signal in the first 12 amino acids of the N terminus. To investigate the subcellular location, an ANK6-GFP gene cassette (driven by the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter) was constructed and introduced into WT plants. Using MitoTracker (Invitrogen) and a DNA-specific dye (Hoechst 33258; Invitrogen) to label mitochondria and nuclei, respectively, we showed that ANK6-GFP was present in both mitochondria and nuclei of root cells. These labels colocalized with the GFP signals in both organelles (Fig. 2C, a–g). We suspect that the nuclear localization may not be specific, because small proteins often diffuse into the nucleus without a specific targeting signal. Mitochondrial localization more strictly depends on a signal peptide at the N terminus of the protein, however.

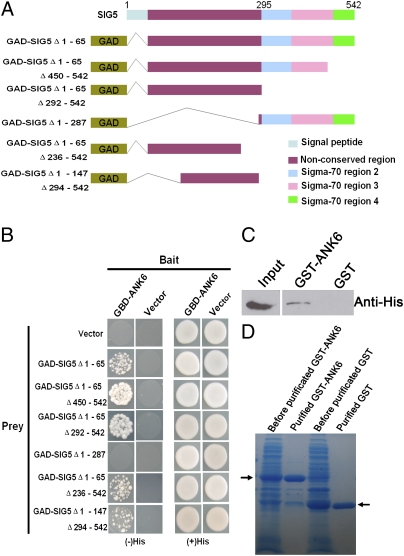

ANK6 Interacts with Mitochondrial/Plastid Transcription Initiation Factor SIG5.

The ankyrin repeat domain is likely to mediate protein-protein interactions. We therefore screened a yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) cDNA library using ANK6 (amino acid residues 21–174) as “bait” and identified several interacting proteins, including SIG5 (Fig. 3B). SIG5 is a member of the σ-factor family of proteins that function as transcription initiation factors in both chloroplasts and mitochondria (26). Interestingly, disruption of SIG5 function was reported to cause homozygous lethality similar to the phenotype of ank6 observed here. Thus, siliques in heterozygous mutant plants (+/sig5) exhibited aborted embryos and unfertilized ovules (26), suggesting that SIG5, like ANK6, plays a role in fertilization or embryo development.

Fig. 3.

Interaction between ANK6 and SIG5 determined by Y2H and in vitro GST pull-down. (A) Diagram of the full-length and truncated SIG5 constructs with specific deletions. (B) Y2H analyses showing ANK6 interaction with the N-terminal nonconserved region of SIG5. (C) Western blot analysis of His-SIG5 protein copurified with GST-ANK6 with anti-His antibody (Center) but not with GST (Right). (Left) Input of His-SIG5 extract. (D) Coomassie brilliant blue staining of GST-ANK6 and GST proteins (arrow).

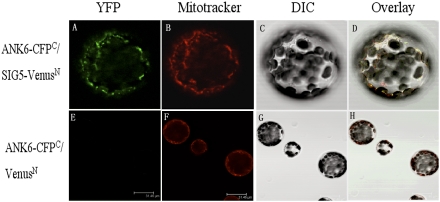

To confirm the interaction between ANK6 and SIG5, we performed both in vitro pull-down assays using recombinant proteins and bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays. Western blot analysis with an anti-His antibody showed that the His-SIG5 protein copurified with GST-ANK6 in the pull-down procedure (Fig. 3 C and D). In the BiFC assays, we coexpressed ANK6 tagged with C-terminal CFP and SIG5 tagged with N-terminal Venus in mesophyll protoplasts (Fig. 4). Interaction with ANK6 was indicated by yellow/green fluorescence (Fig. 4A). MitoTracker was used to localize the mitochondria (Fig. 4B). When Fig. 4 A–C was merged, the yellow/green fluorescence (Fig. 4A) and the red dye signals (Fig. 4B) overlapped (Fig. 4D), confirming that ANK6 and SIG5 interact with each other in mitochondria. The negative controls involving mismatched fluorescence protein complements failed to yield detectable yellow/green fluorescence (Fig. 4 E–H).

Fig. 4.

Interaction between ANK6 and SIG5 determined by BiFC analysis in mesophyll protoplast. Full-length ANK6 protein was fused to C-terminal CFP (CFPC), and full-length SIG5 was fused to N-terminal Venus (VenusN). Mesophyll protoplasts were cotransfected with the ANK6-CFPC and SIG5-VenusN fusion constructs (Upper) or with the ANK6-CFPC fusion and VenusN construct (Lower). YFP signals (green, observed with GFP filter) (A), mitochondria stained with MitoTracker (red) (B), image with differential interference contrast microscopy (DIC) (C), merged image of A–C (D), and images of the control (E–H).

The full-length mature SIG5 has an N-terminal nonconserved region and C-terminal–binding domains (26). To identify the ANK6-interacting domain, six truncated SIG5 variants were fused with GAL4 activation domain (GAD) (Fig. 3A). The interaction between these variants and ANK6 was assayed using the Y2H system (Fig. 3B, Left). ANK6 interacts with the nonconserved N-terminal region of SIG5. SIG5 lacking the C terminus showed the strongest interaction activity with ANK6 among the six variants, suggesting a role for the C terminus in inhibiting the interaction of SIG5 with ANK6 (Fig. 3 A and B).

Although Yao et al. (26) detected SIG5 protein in both the reproductive and vegetative organs by immunoblot analysis, a detailed expression pattern of SIG5 in the reproductive organ was not reported. We thus conducted a GUS reporter assay using transgenic plants harboring SIG5 promoter fused to GUS. SIG5 promoter was highly active in the male and female gametophytes (Fig. 5 A, B, and D) and seedlings (Fig. 5C). In particular, the expression patterns of SIG5 in reproductive organs perfectly matched those of ANK6, making it possible for SIG5 and ANK6 to function together.

Fig. 5.

Expression patterns of SIG5 assayed by GUS reporter analysis. Histochemical GUS staining in the plants transformed with SIG5 promoter-GUS. GUS activities (indicated in blue) were observed in male and female gametophytes. Ovules at FG1 (A) and mature stage (B) and in mature pollen (D). (C) GUS signals also detectable in vegetative tissues. (Scale bars: A, B, and D, 20 μm; C, 0.5 cm.)

ank6 and sig5 Mutants Both Show Defects in Female Gametophyte Development at the One-Nucleate Stage.

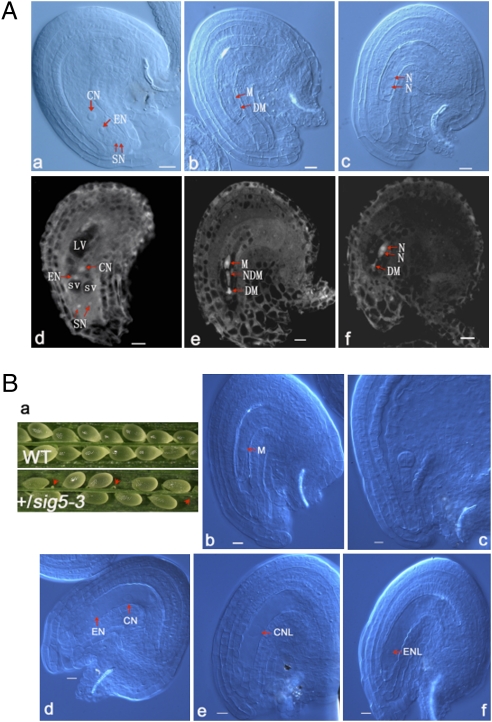

In the genetic analysis of the ANK6 T-DNA insertion mutant, we observed a defect in female gametophytes in addition to homozygous lethality (Table S1). To clarify this defect, we examined ovule development in WT and ank6 plants using whole-mount clearing and confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). Under CLSM, the cytoplasm, nucleoplasm, and nucleoli emit autofluorescence when excited by 488-nm light. Fluorescence from the nucleoli is especially bright, and fluorescence from the cytoplasm and nucleoplasm is moderate. Vacuoles are distinguished by a lack of fluorescence (Fig. 6 A, d). Female gametophyte development in Arabidopsis is divided into seven stages (27). Megagametogenesis of WT plants proceeds normally from the one-nucleate stage, female gametophyte stage 1 (FG1), to FG7. Ovule development in WT pistils is primarily synchronous, spanning at most three neighboring stages (28). After all ovules in WT and a large majority of the ovules in heterozygous plants had developed to FG7 (Fig. 6 A, a and d), however, ∼10% of the ovules (n > 1,000) of the +/ank6 mutants failed to proceed beyond FG1 and were eventually degraded (Fig. 6 A, b and e). Occasionally, the presumed ank6 ovules were arrested at the two-nucleate stage (FG2) (Fig. 6 A, c and f). These results indicate that the mutation also affects female gametophyte development.

Fig. 6.

Ovules are arrested in early developmental stages in both ank6 and sig5 mutants. (A) Ovule development in WT plants and ank6 mutant revealed by Nomarski microscopy and CLSM. CN, central nucleus; DM, degenerated megaspore; EN, egg nucleus; LV, large vacuole; N, nucleate; NDM, nondegenerated megaspore other than the functional megaspore; SN, synergid nuclei; SV, small vacuole. Mature WT ovule with a four-celled embryo sac at FG7 (A, a and d), ank6 mutant ovule arrested at FG1 (A, b and e), and ank6 mutant ovule arrested at FG2 (A, c and f). (Scale bars: 10 μm.) (B) Ovule development in WT plants and in sig5 mutant revealed by Nomarski microscopy. CN, central nucleus; CNL, central nuclear-like nucleus; EN, egg nucleus; ENL, egg nuclear-like nucleus; M, megaspore. Silique of self-pollinated +/sig5 plants showing frequently observed degenerating ovules indicated by arrowheads (B, a), sig5 mutant ovule arrested at FG1 (B, b), embryo at early globular stage of development in normal ovule of the same silique of control (B, c), sig5 mutant ovule arrested with egg cell and central cell unfertilized (B, d), sig5 mutant ovule arrested with a central cell-like nucleus remaining (B, e), and sig5 mutant ovule arrested with an egg cell-like nucleus remaining (B, f). (Scale bars: 10 μm.)

We next examined the functional similarity between ANK6 and SIG5 by monitoring ovule development in a SIG5 T-DNA insertion line. Phenotypic analysis was performed with a SIG5 T-DNA mutant (Salk_141383). The heterozygous mutant (+/SIG5-3), but not homozygous mutant, was obtained and displayed a white shriveled ovule phenotype (Fig. 6 B, a), which is similar to the phenotype reported earlier with +/sig5-1 and +/sig5-2 (26). Further analysis of the mutant showed that when normal ovules developed to the early globular embryo stage, a fraction of sig5 ovules, like some in +/ank6 plants, were arrested at the FG1 stage (Fig. 6 B, b), suggesting that SIG5, like ANK6, plays a minor role in ovule development.

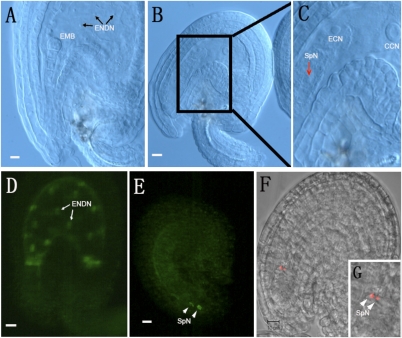

ank6 Is Defective in Sperm-Female Gamete Recognition.

To identify the cause of the phenotypic change, we further examined fertilization and zygote development in WT and +/ank6 plants. When all WT ovules had reached the preglobular embryo stage with multiple endosperm nuclei, ≈22% of the ovules in +/ank6 heterozygous plants appeared to be unfertilized. Moreover, some of the +/sig5-3 mutant ovules that had reached FG7 showed arrested development (Fig. 6 B, c–f), suggesting that SIG5, like ANK6, plays a role in ovule development and fertilization. Occasionally, one or two presumed sperm nuclei (29, 30) were observed at a site near the egg cell in the embryo sac (Fig. 7C, arrow). This observation prompted us to hypothesize that although released successfully into the embryo sacs, the mutant ank6 sperm cells failed to fuse with their targets. We therefore investigated whether gamete recognition was impaired. To this end, we fertilized +/ank6 and WT plant ovules with pollen from LIG1-GFP/ank6, a line expressing the nuclear marker DNA LIGASE 1 fused to GFP (LIG1-GFP) (31). As seen in Fig. 7D, the paternal expression of LIG1-GFP labeled both the embryo and endosperm in seeds produced from WT ovules. Approximately 40 h after the LIG1-GFP–labeled +/ank6 pollen had pollinated +/ank6 and WT plants, all ovules of WT and most of heterozygotes had developed from zygote elongation to the 16-cell embryo stage with multiple endosperm nuclei (Fig. 7D). About 10% of the ovules in heterozygous plants were unfertilized with two LIG1-GFP–labeled sperm nuclei near the degenerated synergid cells (Fig. 7E, arrowheads). The results suggested that ank6 sperm cells were indeed released into the embryo sacs but failed to fuse to their targets, reflective of a defect in sperm-female gamete recognition.

Fig. 7.

Assessment of gamete interaction in +/ank6 plants. Nomarski images of the ovules from a self-pollinated +/ank6 silique. CCN, central cell nucleus; ECN, egg cell nucleus; EMB, embryo; ENDN, endosperm nucleus; SpN, sperm nucleus. Morphologically normal ovule showing embryo at early globular stage of development (A), cleared mutant (unfertilized) ovule showing central cell, polarized egg cell (B and C), with sperm-like nucleus near egg cell in the sac (arrow). Paternally provided fluorescent LIG1-GFP marker is expressed after fertilization in the embryo and the endosperm. WT ovules and normal ovules in heterozygous plants developed from zygote elongation to 16-cell embryo stages with multiple endosperm nuclei (D; arrows); a small portion of the ovules in heterozygous plants are unfertilized with two sperm-like nuclei near the degenerated synergid cells (E; arrowheads). (F) Sperm-specific marker pHTR10-mRFP labeled free sperm nuclei after +/ank6 self-pollinated plants were examined. (G) Box shows the pHTR10-mRFP1 signals from two unfertilized sperm nuclei (arrowheads).

To test this possibility further, we used a transgenic Arabidopsis line whose male gametes expressed pHTR10-mRFP1 (monomeric red fluorescent protein 1) as a sperm-nuclear marker (32) and produced hybrid Arabidopsis plants containing both mutant ank6 and pHTR10-mRFP. The construct expresses mRFP1 under the control of the germline specific promoter HTR10, displaying fluorescence specifically in the two sperm-nuclei. When the paternal pHTR10-mRFP1 spreads to all nuclei of the fertilized central cell and the zygote, the mRFP1 signal disappears by direct dilution in the endosperm and replacement in the zygote (32). In normal plants, the ovules that have been double fertilized will emit no RFP signal within 1–2 d after pollination. In contrast, the ovules that fail in double fertilization because of defects in male-female gamete recognition could contain free sperm cells labeled by RFP signal. Siliques at about the 16-cell embryo stage were collected and analyzed from the self-pollinated pHTR10-mRFP+/+/ank6−/+ mutant and pHTR10-mRFP WT plants. In the self-pollinated pHTR10-mRFP+/+/ank6−/+ plants, we were able to detect sperm nuclei in most of the unfertilized ovules (Fig. 7 F and G). The shape of the mRFP1 signal was tight and compact, quite different from that of the mRFP1 signal in which karyogamy (merging of the male and female nuclei) had taken place. We did not observe such free sperm nuclei in pHTR10-mRFP–containing WT plants. The results thus confirmed that ANK6 plays a role in sperm-female gamete recognition. In other words, the ank6 mutant had defects in sperm-female gamete recognition only when an ank6 sperm cell reached an ank6 female gamete.

Concluding Remarks.

ANK proteins are well-known “adapter” proteins that mediate protein-protein interaction through the ANK repeat motif. Although the Arabidopsis genome encodes a large number of members of this family, the function of very few has been investigated. Although certain ANK proteins were reported to participate in embryo development (33, 24), the associated molecular mechanism is largely unknown.

SIG5 is localized in chloroplasts in the leaf during plant development most of the time. On flowering, a longer SIG5 protein was synthesized and targeted to both mitochondria and plastids of flower (26). Here, we have presented evidence that one of the ANK proteins, ANK6, interacts with an RNA polymerase transcription initiation factor, the longer SIG5 in mitochondria instead of the shorter version in plastids, thereby fulfilling a central function in male-female gamete recognition in ovules. By analogy with another σ-factor, σ70 (34–37), the results suggest that when flowering, ANK6 interacts with the inhibitory N-terminal sequence of SIG5 to uncover its C-terminal domain activities in the mitochondria. The released C terminus then binds both to the core enzyme to form a holoenzyme and to the promoter of a specific downstream region of the mitochondrial genome. Binding initiates the transcription of selected specific genes encoding enzymes or proteins that may be essential for production of a diffusible factor involved in gamete recognition in both gametophytes. The defect in the production or release of the factor in one gametophyte is rescued by diffusion of the molecule from the other gametophyte nearby. Therefore, fertilization is blocked only when both gametes are defective in producing this factor. Future experiments with mutants defective in other gamete recognition proteins coupled with identification of mitochondrial gene(s) regulated by SIG5-coupled transcriptional factor should further our understanding of gamete recognition.

Materials and Methods

The materials and methods used are briefly summarized below. Additional information is given in SI Materials and Methods.

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions.

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia 0 plants were grown in a constant-temperature room at 22 °C under 16-h light/8-h dark cycles. Seeds for the T-DNA insertion lines were purchased from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center.

Cleared Whole-Mount Preparations.

Ovules were excised from siliques and mounted with a clearing solution. After 15–60 min of incubation, samples were examined under a Leica DMR microscope (Leica Microsystems) fitted with differential interference contrast optics.

CLSM.

CLSM of ovules and seeds was performed as described previously (27). The sample was viewed with a Zeiss LSM510 META laser-scanning microscope.

Molecular Cloning.

The plasmid 35S-ANK6-GFP was prepared by cloning the ANK6 coding region without the stop codon into pMD1-GFP vector. Genomic DNA promoter fragment of the ANK6 gene and SIG5 were inserted into pBI101.2. For genetic complementation, the ANK6 promoter and cDNA terminator were subcloned into binary vector pCAMBIA 1300.

GUS Assays.

Pistils and siliques were opened and incubated in GUS staining solution for 2–3 d at 37 °C and observed with a Zeiss microscope. For staining the whole seedling, plants were first decolorized with 95% (vol/vol) ethanol and then examined and photographed with an Olympus SZX12 microscope equipped with a camera.

Y2H Screen.

AH109 yeast cells were first transformed with pBD-ANK6 and subsequently transformed with the Arabidopsis cDNA library. The transformed cells were plated on synthetic dropout selection medium that lacked Trp, Leu, and His supplemented with 20 mM 3-AT to reduce the growth of false-positive colonies. The full-length SIG5 cDNA was PCR-amplified from Arabidopsis cDNA, sequenced, and cloned into pGADT7 (Clontech) for further analysis.

Recombinant Protein Expressions and in Vitro Pull-Down Assays.

Recombinant His-SIG5 (encoding SIG5 amino acids 65–542 with an N-terminal 6× His tag) was generated in pET28A expression vector (Novagen). Recombinant GST-ANK6 was generated in pGEX4T-1 (Amersham Biosciences) expression vector. The pull-down assay was performed as described (38).

BiFC Assays.

The ORF sequence of ANK6 and SIG5 was cloned into the plasmid pE3449 and pE3308. Protoplasts were isolated from 5-wk-old Arabidopsis rosette leaves. Transient protoplast expression was performed using the polyethylene glycol transformation method.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Sheila McCormick for helpful comments and edits to the manuscript; Dr. Chunming Liu for assistance and helpful discussions on phenotype analysis; Dr. Frédéric Berger (Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory, National University of Singapore, Singapore) for pHTR10-HTR10-RFP and LIG1-GFP seeds; Drs. Stanton Gelvin and Lan-Ying Lee (Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN) for BiFC vectors; Drs. Xuanmin Liu and Chentao Lin for advice on Y2H experiments; and Drs. Weicai Yang, Dongqiao Shi, and Xianyong Sheng for assistance in laser confocal analysis. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (Grants NSFC-30970273 and NSFC-30830070, 2009ZX08009-127B), Hunan Provincial Scientific Programs (Grants 2009FJ1004-2 and 2007ZK3010), and the US National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1015911107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dresselhaus T. Cell-cell communication during double fertilization. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006;9:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger F. Double-fertilization, from myths to reality. Sex Plant Reprod. 2008;21:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higashiyama T, Hamamura Y. Gametophytic pollen tube guidance. Sex Plant Reprod. 2008;21:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Márton ML, Dresselhaus T. A comparison of early molecular fertilization mechanisms in animals and flowering plants. Sex Plant Reprod. 2008;21:37–52. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palanivelu R, Brass L, Edlund AF, Preuss D. Pollen tube growth and guidance is regulated by POP2, an Arabidopsis gene that controls GABA levels. Cell. 2003;114:47–59. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00479-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasahara RD, Portereiko MF, Sandaklie-Nikolova L, Rabiger DS, Drews GN. MYB98 is required for pollen tube guidance and synergid cell differentiation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2981–2992. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.034603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Márton ML, Cordts S, Broadhvest J, Dresselhaus T. Micropylar pollen tube guidance by egg apparatus 1 of maize. Science. 2005;307:573–576. doi: 10.1126/science.1104954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen YH, et al. The central cell plays a critical role in pollen tube guidance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3563–3577. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.053967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weterings K, Russell SD. Experimental analysis of the fertilization process. Plant Cell. 2004;16(Suppl):S107–S118. doi: 10.1105/tpc.016873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okuda S, et al. Defensin-like polypeptide LUREs are pollen tube attractants secreted from synergid cells. Nature. 2009;458:357–361. doi: 10.1038/nature07882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huck N, Moore JM, Federer M, Grossniklaus U. The Arabidopsis mutant feronia disrupts the female gametophytic control of pollen tube reception. Development. 2003;130:2149–2159. doi: 10.1242/dev.00458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotman N, et al. Female control of male gamete delivery during fertilization in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr Biol. 2003;13:432–436. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Escobar-Restrepo JM, et al. The FERONIA receptor-like kinase mediates male-female interactions during pollen tube reception. Science. 2007;317:656–660. doi: 10.1126/science.1143562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Capron A, et al. Maternal control of male-gamete delivery in Arabidopsis involves a putative GPI-anchored protein encoded by the LORELEI gene. Plant Cell. 2008;20:3038–3049. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rotman N, Gourgues M, Guitton AE, Faure JE, Berger F. A dialogue between the SIRENE pathway in synergids and the fertilization independent seed pathway in the central cell controls male gamete release during double fertilization in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2008;1:659–666. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssn023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boisson-Dernier A, et al. Disruption of the pollen-expressed FERONIA homologs ANXUR1 and ANXUR2 triggers pollen tube discharge. Development. 2009;136:3279–3288. doi: 10.1242/dev.040071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyazaki S, et al. ANXUR1 and 2, sister genes to FERONIA/SIRENE, are male factors for coordinated fertilization. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1327–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boisson-Dernier A, Frietsch S, Kim TH, Dizon MB, Schroeder JI. The peroxin loss-of-function mutation abstinence by mutual consent disrupts male-female gametophyte recognition. Curr Biol. 2008;18:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mori T, Kuroiwa H, Higashiyama T, Kuroiwa T. GENERATIVE CELL SPECIFIC 1 is essential for angiosperm fertilization. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:64–71. doi: 10.1038/ncb1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Besser K, Frank AC, Johnson MA, Preuss D. Arabidopsis HAP2 (GCS1) is a sperm-specific gene required for pollen tube guidance and fertilization. Development. 2006;133:4761–4769. doi: 10.1242/dev.02683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong JL, Leydon AR, Johnson MA. HAP2(GCS1)-dependent gamete fusion requires a positively charged carboxy-terminal domain. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breeden L, Nasmyth K. Similarity between cell-cycle genes of budding yeast and fission yeast and the Notch gene of Drosophila. Nature. 1987;329:651–654. doi: 10.1038/329651a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Mahajan A, Tsai MD. Ankyrin repeat: A unique motif mediating protein-protein interactions. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15168–15178. doi: 10.1021/bi062188q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcion C, et al. AKRP and EMB506 are two ankyrin repeat proteins essential for plastid differentiation and plant development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2006;48:895–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee SC, et al. A protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation network regulates a plant potassium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15959–15964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707912104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao JL, Roy-Chowdhury S, Allison LA. AtSig5 is an essential nucleus-encoded Arabidopsis σ-like factor. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:739–747. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.017913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christensen CA, King EJ, Jordan JR, Drews GN. Megagametogenesis in Arabidopsis wild type and the Gf mutant. Sex Plant Reprod. 1997;10:49–64. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu JJ, et al. Targeted degradation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor ICK4/KRP6 by RING-type E3 ligases is essential for mitotic cell cycle progression during Arabidopsis gametogenesis. Plant Cell. 2008;20:1538–1554. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.059741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rotman N, et al. A novel class of MYB factors controls sperm-cell formation in plants. Curr Biol. 2005;15:244–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boavida LC, et al. A collection of Ds insertional mutants associated with defects in male gametophyte development and function in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 2009;181:1369–1385. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.090852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ingouff M, et al. The two male gametes share equal ability to fertilize the egg cell in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr Biol. 2009;19:R19–R20. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ingouff M, Hamamura Y, Gourgues M, Higashiyama T, Berger F. Distinct dynamics of HISTONE3 variants between the two fertilization products in plants. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1032–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Albert S, et al. The EMB 506 gene encodes a novel ankyrin repeat containing protein that is essential for the normal development of Arabidopsis embryos. Plant J. 1999;17:169–179. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dombroski AJ, Walter WA, Record MT, Jr., Siegele DA, Gross CA. Polypeptides containing highly conserved regions of transcription initiation factor σ70 exhibit specificity of binding to promoter DNA. Cell. 1992;70:501–512. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90174-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dombroski AJ, Walter WA, Gross CA. Amino-terminal amino acids modulate σ-factor DNA-binding activity. Genes Dev. 1993;7(12A):2446–2455. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12a.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vassylyev DG, et al. Crystal structure of a bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme at 2.6 Å resolution. Nature. 2002;417:712–719. doi: 10.1038/nature752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hook-Barnard IG, Hinton DM. The promoter spacer influences transcription initiation via σ70 region 1.1 of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:737–742. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808133106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang DH, Gu XF, He YH. Establishment of the winter-annual growth habit via FRIGIDA-mediated histone methylation at FLOWERING LOCUS C in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21:1733–1746. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.067967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.