Abstract

Background

Effective condom use can prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unwanted pregnancy. We conducted a systematic review and methodological appraisal of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of interventions to promote effective condom use.

Methods

We searched for all RCTs of interventions to promote effective condom use using the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group's trials register (Oct 2006), CENTRAL (Issue 4, 2006), MEDLINE (1966 to Oct 2006), EMBASE (1974 to Oct 2006), LILACS (1982 to Oct 2006), IBSS (1951 to Oct 2006) and Psychinfo (1996 to Oct 2006). We extracted data on allocation sequence, allocation concealment, blinding, loss to follow-up and measures of effect. Effect estimates were calculated.

Results

We identified 139 trials. Seven out of ten trials reported reductions in ‘any STI’ with five statistically significant results. Three out of four trials reported reductions in pregnancy, although none was statistically significant. Only four trials met all the quality criteria. Trials reported a median of 11 (IQR 7–17) outcome measures. Few trials used the same outcome measure. Altogether, 10 trials (7%) used the outcome ‘any STI’, 4 (3%) self-reported pregnancy and 22 (16%) used ‘condom use at last sex’.

Conclusions

The results are generally consistent with modest benefits but there is considerable potential for bias due to poor trial quality. Because of the low proportion of trials using the same outcome the potential for bias from selective reporting of outcomes is considerable. Despite the public health importance of increasing condom use there is little reliable evidence on the effectiveness of condom promotion interventions.

Keywords: Contraception RB, contraception SA, sexual behaviour, sexual health, sexually transdis

Introduction

Unsafe sex is believed to be the second most important risk factor for disease, disability or death in the poorest countries of the world, and the ninth most important factor in developed countries.1 Effective condom use has the potential to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV, and unwanted pregnancy.2 3 However, condom effectiveness is lower than condom efficacy due to non use, inconsistent use and the incorrect application of condoms.4 5 Therefore, interventions that promote effective condom use have considerable potential to improve public health.

Interventions to increase effective condom use have addressed condom design, access to condoms, condom use behaviours and condom-related legislation. Existing systematic reviews of the effectiveness of interventions to promote effective condom use have examined specific population groups or interventions,6–8 but to date there has been no comprehensive systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of interventions to promote effective condom use.

Although systematic reviews of RCTs are considered to provide the most valid and reliable evidence of the effectiveness of healthcare interventions, recent studies have drawn attention to the effect of trial quality and selective publication on their results.9 Selective publication of trials has been recognised as a potent threat to validity for many years but more recently the importance of selective publication of trial outcomes has also been highlighted.10–13 We report a systematic review and methodological appraisal of RCTs of interventions to promote effective condom use.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

We included all RCTs of interventions to promote effective condom use regardless of publication status or language. Participants were men and women of any age. Interventions were any measure intended to increase effective condom use. Trials of female condoms or those comparing latex and non-latex condoms were excluded because they have been reviewed previously.14 Primary outcomes were the occurrence of pregnancy and STIs. Secondary outcomes were measures of condom use, including condom use at first sexual intercourse, condom use at last sexual intercourse, 100% condom use, frequency of condom use, frequency of unprotected sex, proportion of episodes of sex protected, condom use scales and refusal of sexual intercourse if condom not used. Secondary outcomes for condom failure outcomes included clinical breakage, non-clinical breakage and full or partial slippage rates.

Search strategy

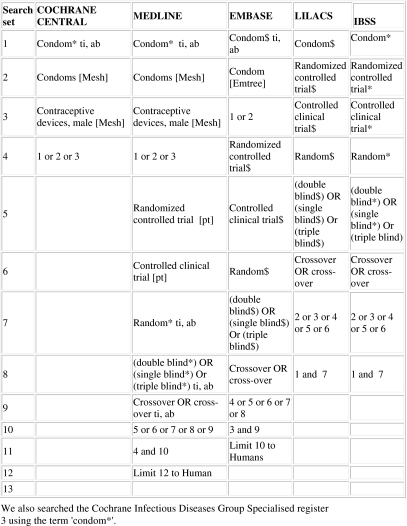

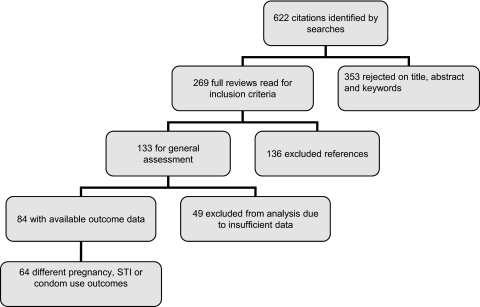

We searched the Cochrane Infectious Diseases Group's trials register (Oct 2006), CENTRAL (Issue 4, 2006), MEDLINE (1966 to Oct 2006), EMBASE (1974 to Oct 2006), LILACS (1982 to Oct 2006), IBSS (1951 to Oct 2006) and Psychinfo (1996 to Oct 2006) using the search terms condom, contraceptive devices male, condom breakage, slippage and failure in combination with the Cochrane collaboration's search strategy for retrieving trials (figure 1).15 We searched conference proceedings, contacted researchers and organisations working in the field and checked the reference lists of all identified reports. Two reviewers independently scanned the electronic records to identify potentially trials.

Figure 1.

Search strategy.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted data on the generation of the allocation sequence, allocation concealment, blinding and loss to follow-up according to the quality criteria developed by Juni9 (see key to additional table 1 online for full details). Overall losses to follow-up of up to 10% were scored adequate. We extracted data on the measure of effect used in each trial. In trials that collected short and long-term follow-up data, we extracted the long-term follow-up data. A reviewer contacted trial authors asking for all unclear or unreported methods and data. All discrepancies were agreed by discussion with a third reviewer. Trials that scored adequate for reporting of all four quality criteria were categorised as ‘high quality trials’. Data were extracted regarding whether clustering had been taken into account in the analysis.

Data analysis and synthesis

All analyses were conducted in STATA version 9.0. We used funnel plots to explore small study effects. We calculated the log of the ORs and standard mean differences (SMDs).16 For the purposes of meta-analysis, condom use outcomes during vaginal sex and unspecified type of sex were treated as the same outcome. Where two or more intervention arms were compared against a single control arm and the arms tested similar interventions, the most intensive intervention (with most components or longest duration) was included in the analysis. Where two or more diverse intervention arms were compared against a single control arm, or a factorial design was used, results are presented separately.

Poor trial quality is a source of bias so we report the results of trials that met the four quality criteria (allocation sequence, allocation concealment, loss to follow-up and blinding of outcome assessment) separately to other trials. We used random effects meta-analysis to give pooled estimates.17 Cluster randomised trial effect estimates were calculated based on the intra-cluster correlation co-efficient reported or, when not reported, the lowest of the published intra cluster co-efficient in the review.18 We examined heterogeneity visually by examining forest plots and statistically using the a χ2 test and I2 test for consistency.19 We explore the role of study quality via allocation concealment and inadequate or unclear blinding as these elements of study quality have been shown to influence outcomes reported.9

Results

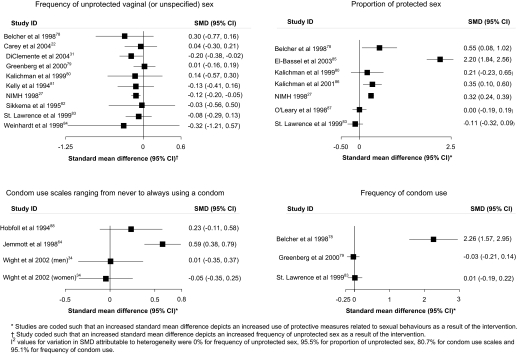

The combined search strategies identified 622 electronic records. These were screened for eligibility and the full texts of 269 potentially eligible reports were obtained for further assessment. Out of the 269 potentially eligible reports, 138 reports containing 139 RCTs met the study inclusion criteria (figure 2). See additional table 1 online for a short description of all studies and the results of the quality assessment.

Figure 2.

Associations of the effects of behavioural interventions on primary outcomes sexually transmitted infection (STI) and self-reported pregnancy.

Characteristics of studies

The 139 trials included approximately 143 000 participants. Of the 139 trials, one used a crossover design, 32 were cluster randomised trials and one used a factorial design. Altogether, 21 of the 32 cluster randomised trials reported having adjusted the results for clustering. Trial participants were recruited from several different settings, including healthcare (57 trials), education (28 trials), community (43 trials), military (1 trial) and unspecified (10 trials). Thirty-three trials had two or more intervention arms. The target populations were young people (48 trials), people with an STI (26 trials), intravenous drug users (19 trials), men who have sex with men (15 trials), other high risk individuals (17 trials), psychiatric patients (5 trials) and unspecified (15 trials). Altogether, 13 trials recruited participants from specific ethnic groups; the other 126 trials did not specify the ethnicity of participants. The median interval between randomisation and last outcome measurement was 26 weeks (IQR 13–52).

Interventions

The trials evaluated 181 different interventions. These were individual sexual behaviour change (n=156), sexual and intravenous drug behavioural change (n=19) and condom design (n=6). There were 23 simple interventions (with one or two components) and 158 complex interventions (with three or more components). The sexual behaviour change interventions addressed information, attitudes, condom use skills and/or condom availability, interpersonal factors within the sexual relationship influencing condom use and social factors influencing sex and condom use (see additional table 2 online). Sexual and intravenous drug behaviour interventions addressed safer injecting behaviour (15 trials), links between substance use and condom use (11 trials), substance use reduction (12 trials) and detoxification treatment (1 trial). Condom design trial interventions included providing a choice of condoms of different designs, different standards for manufacture of condoms, thicker/thinner condoms and different shapes of condom (baggy/straight shafted).

Outcomes and reporting bias

The trials included 90 different STI, pregnancy or condom use outcome measures. Trials reported between 1 and 49 outcomes per trial (median 11; IQR 7–17). Among the outcome measures used most frequently, 10 trials (7%) used the outcome ‘any STI’, 4 (3%) self-reported pregnancy and 22 (16%) used ‘condom use at last sex’.

Few trials used objective measures. Only 21(15%) trials reported a pregnancy or objective STI outcome measure. One trial used an objective measure of condom use.

Fifty-two trials did not provide enough data to calculate effect estimates so it was only possible to calculate effect estimates for 63% (n=87) of the trials.

Study quality

Only four trials scored adequate for reporting of all four quality criteria (allocation sequence, allocation concealment, loss to follow-up and blinding).31 35–37 The generation of the allocation sequence was adequate in 54 trials (39%), allocation concealment was adequate in 32 trials (23 %), losses to follow-up were adequate in 24 trials (17%) and outcome assessment was blinded in 34 trials (24%).

Effectiveness

For each type of intervention—sexual behaviour change interventions, sexual and intravenous drug behaviour change interventions and condom design interventions—we report the primary (pregnancy and STI) and secondary (condom use) outcomes. The results of high-quality trials are presented first followed by the results of other trials.

Sexual behaviour change interventions

Primary outcomes: pregnancy and STI

High-quality trial results

There was one trial which met all four quality criteria. Feldblum et al's trial evaluated peer education combined with individual risk counselling by a clinician among sex workers in Madagascar and reported a reduction in self-reported sexually transmitted disease symptoms OR=0.67 (0.51–0.89).35

Other trial results

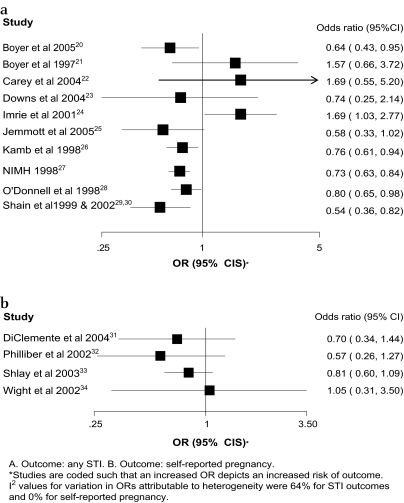

Figure 3 shows forest plots for the effect of complex sexual behaviour change interventions on primary outcome measures. Three of the four trials reporting results regarding self-reported pregnancy had fewer pregnancies in the intervention group but no results were statistically significant. In 7 of the 10 trials reporting the outcome ‘any STI’ there were fewer STIs in the intervention group with five statistically significant results. One trial reported a statistically significant increase in ‘any STI’. Table 1 shows the effect estimates for trials reporting other STI outcomes. In 10 out of the 16 reported outcomes there were fewer STIs in the intervention group with three statistically significant results. One trial reported a statistically significant reduction in gonorrhoea and a statistically significant increase in syphilis.42

Figure 3.

Associations of the effects of behavioural interventions on secondary binary outcomes measuring condom use during sex.

Table 1.

Primary outcomes for sexual behaviour change interventions

| Study | Outcome | OR/RR/SMD |

| (95% CI) | ||

| High-quality trials | ||

| Feldblum35 | STD symptoms | OR 0.67 (0.51 to 0.89) |

| Other trials | ||

| Branson36 | Gonorrhoea | OR 0.92 (0.64 to 1.32) |

| Branson36 | Syphillis | OR 1.80 (0.61 to 5.32) |

| Branson36 | Chlamydia | OR 0.90 (0.60 to 1.36) |

| Cohen 199237 (condom skills) | Reinfection with STI | OR 0.57 (0.34 to 0.96) |

| Cohen 199237 (condom distribution) | Reinfection with STI | OR 0.91 (0.58 to 1.44) |

| Cohen 199237 (condom social influences) | Reinfection with STI | OR 0.97 (0.60 to 1.56) |

| Diclemente38 | Chlamydia | OR 0.17 (0.03 to 0.09)* |

| Explore39 | HIV | OR 0.79 (0.61 to 1.02) |

| Gollub40 | Probable STI | OR 1.09 (0.60 to 1.99) |

| Harvey41 | Treated for STD in last 6 months | OR 0.96 (0.74 to 1.23) |

| Kamali42 | HIV rate (PY) | RR 1.00 (0.87 to 1.16) |

| Kamali42 | Gonorrhoea rate (PY) | RR 0.43 (0.32 to 0.59) |

| Kamali42 | Chlamydia rate (PY) | RR 1.06 (0.88 to 1.27) |

| Kamali42 | CHSV2 rate (PY) | RR 1.04 (0.93 to 1.17) |

| Kamali42 | Active syphilis rate (PY) | RR 7.01 (5.82 to 8.51) |

| Shain43 | Chlamydia or gonorrhoea | OR 0.8 (0.55 to 1.16) |

Results in italics are for studies with factorial design or those where more than one comparison group tested against a single control has been included.

These are the results reported in the paper, which adjusted for baseline variables and covariates.

PY, per year; STD, sexually transmitted disease; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Exploring heterogeneity in STI outcomes according to study quality

Pooled estimates for the outcome ‘any STI’ 0.79 (95% CI 0.66 to 0.94) showed considerable heterogeneity (I2 64%, p=0.003). The pooled OR for ‘any STI’ among trials with adequate allocation concealment was 0.98 (95% CI 0.64 to 1.52; I2 75.9%; p=0.006) and for trials with inadequate or unclear allocation concealment was 0.73 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.83; I2 9.8%; p=0.353). The pooled OR for ‘any STI’ among trials with adequate blinding of the outcome assessor was 0.83 (95% CI 0.62 to 1.10; I2 73.4%; p=0.01) and for trials with inadequate or unclear blinding was 0.76 (95% CI 0.58 to 0.99; I2 39.1%; p=0.145).

Secondary outcomes: condom use

High-quality trial results

There were two trials that met all four quality criteria. Egger et al used an objective measure of condom use (finding a used condom in the motel room bin).44 They found that giving out condoms and providing condoms in motel rooms used for commercial sex increased condom use compared to having condoms available on request from reception (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.61 and OR 1.31, 1.09 to 1.75, respectively. In motel rooms used for non-commercial sex, the same strategies also increased condom use for handing out condoms (OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.14 to 2.81) and for having condoms in motel rooms (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.38). Providing health educational materials reduced condom use in commercial sex compared to when health educational materials were not provided (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.94).44 Ehrhardt et al evaluated small group gender-specific discussion and used self-reported outcomes of either maintaining or improving safe sex (OR 1.64, 95% CI 0.95 to 2.86).45

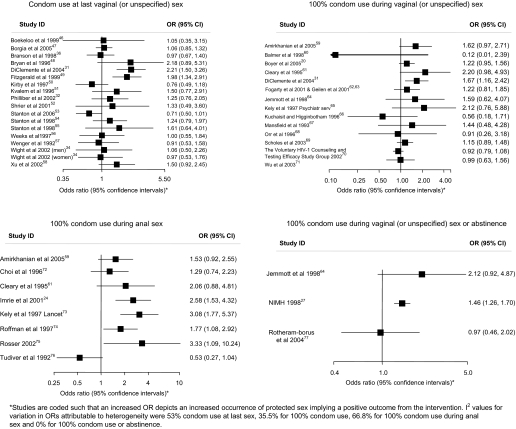

Other trial results

Figures 4 and 5 and table 2 show the effect estimates for trials for each measure of condom use. For condom use at last sex, 9 of the 18 trials reported increases in condom use with two statistically significant results. For 100% condom use in vaginal (or unspecified) sex, 9 of the 14 trials reported increases in condom use although none was statistically significant. For 100% condom use for anal sex, seven of the eight trials reported increases in condom use with three statistically significant results. Two out of three trials reported increases in 100% condom use or abstinence with one statistically significant result. No trials reported increases in the frequency of protected sex. Three out of six trials reported statistically significant increases in the proportion of sex protected. For outcomes using condom use scales, two out of four trials reported increases in condom use of which one was statistically significant. One of three trials reported a statistically significant increase in the frequency of condom use. In 16 of the 22 other condom use outcomes reported, there was more condom use in the intervention group with eight showing statistical significance (table 2).

Figure 4.

Associations of the effects of behavioural interventions on continuous secondary outcomes looking at frequency or proportion of unprotected sex or condom use.

Figure 5.

Flow chart of systematic review.

Table 2.

Secondary outcomes for sexual behaviour change interventions

| Study | Outcome | OR/SMD (95% CI) |

| High quality trials | ||

| Egger44(condom in room commercial sex hotel) | Retrieval of at least one condom | OR 1.31 (1.09 to 1.75) |

| Egger44(condom handed to client commercial sex hotel) | Retrieval of at least one condom | OR 1.32 (1.03 to 1.61) |

| Egger44(condom in room, non-commercial sex hotel) | Retrieval of at least one condom | OR 181 (1.14 to 2.81) |

| Egger44(condom handed to client non-commercial sex hotel) | Retrieval of at least one condom | OR1.52 (1.01 to 2.38) |

| Egger44(leaflet, commercial sex workers) | Retrieval of at least one condom | OR0.89 (0.84 to 0.94) |

| Egger44(leaflet non-commercial sex workers) | Retrieval of at least one condom | OR 1.03 (0.97 to 1.08) |

| Ehrhardt30 | Maintaining/improving safe-sex (women) | OR 1.64 (0.95 to 2.86) |

| Other trials | ||

| Bellingham89 | Condom use at last sex (vaginal or unspecified) | OR 0.58 (0.31 to 1.12) |

| Downs23 | Number of condom failures (over period ≥3 months) | SMD −0.25 (−0.55 to 0.06) |

| Downs23 | Consistency of condom use with partners | SMD 0.14 (−0.14 to 0.43) |

| Downs23 | Number of condom failures | SMD −0.25 (−0.55 to 0.06) |

| Hobfoll88 | Condom use scale (never – always) anal sex | SMD 0.316 (−0.034 to 0.67) |

| Jemmot25 | Number of days had unprotected sex in last year | SMD −4.42 (−4.89 to −3.95) |

| Kalichman80 | No condom, no sex (vaginal or unspecified) | OR 1.90 (0.74 to 4.88) |

| Kalichman80 | Condom use over 50% of the time | OR 2.36 (0.92 to 6.01) |

| Picciano90 | Frequency of condom use (oral sex) | SMD 0.062 (−0.35 to 0.48) |

| Robert91(eroticising safer sex) | 100% condom use or abstinence (anal sex) | OR 0.42 (0.10 to 1.89) |

| Robert91(Stop AIDS Programme) | 100% condom use or abstinence (anal sex) | OR 0.96 (0.18 to 5.22) |

| Roffman74 | Proportion of oral sex protected | SMD 0.02 (−0.21 to 0.25) |

| Roffman74 | Proportion of anal sex protected | SMD 0.28 (0.05 to 0.52) |

| Rosser75 | Change in unsafe anal sex | SMD −0.20 (−0.51 to 0.11) |

| Rosser75 | Change in failure to use condoms | SMD −0.79 (−1.35 to −0.23) |

| Stephenson92 | Unprotected first sex by age 16 y | OR 0.89 (0.24 to 3.31) |

| Shain 1999 and 200229 | <5 episodes of unsafe sex in last 3 months | OR 2.09 (1.44 to 3.05) |

| Shlay33 | Condom use over 50% of the time | OR 1.14 (0.82 to 1.57) |

| Swanson93 | Percentage of time condoms used to prevent herpes | SMD 0.28 (0.01 to 0.54) |

| The Voluntary HIV Testing Study70 | 100% protected sex with non-primary partner | OR 1.32 (0.98 to 1.78) |

| Tripiboon94 | Condom use score (for married couples) | SMD 11.04 (10.14 to 11.94) |

| Wenger57 | No condom, no sex (unspecified or vaginal) | OR 2.55 (1.19 to 5.45) |

Results in italics are for trials with a factorial design or trials where the results of more than one comparison group tested against a singe control group are reported.

All secondary outcomes reported in this table are used in less than three other trials of this type of intervention.

Sexual and intravenous drug behaviour change interventions

Primary outcomes: pregnancy and STI

High-quality trial results

There were no trials of sexual and intravenous drug behaviour change interventions that met all four quality criteria.

Other trial results

The Iguchi 1996 trial95 compared a 90-day drug detoxification programme to a 21-day drug detoxification programme and reported an OR consistent with a reduction in HIV acquisition (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.11 to 1.28) (table 3).

Table 3.

Primary and secondary outcomes for sexual and intravenous drug behaviour change interventions

| Study | Outcome | OR or SMD |

| (95% CI) | ||

| Primary outcomes | ||

| Iguchi95 | Acquisition of HIV | OR 0.37 (0.11 to 1.28) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| Avants96 | Number of weeks had sex without a condom | SMD −0.326 (−0.594 to −0.059) |

| Cottler97 | No sex if no condom | OR 0.99 (0.70 to 1.40) |

| Cottler97 | Used a condom in the last 30 days | OR 1.01 (0.74 to 1.36) |

| Cottler97 | ‘Improved’ condom use | OR 1.31 (0.98 to 1.77) |

| Eldridge98 | Log mean proportion of vaginal sex protected | SMD 0.925 (0.356 to 1.494) |

| Kotranski99 | 100% condom use or abstinence (vaginal or unspecified) | OR 1.50 (1.02 to 2.22) |

| Cottler97 | 100% condom use (vaginal or unspecified) | OR 0.95 (0.66 to 1.37) |

| Margolin100 | 100% condom use (vaginal or unspecified) | OR 3.94 (0.94 to 16.58) |

| Hershberger101 | 100% condom use (vaginal or unspecified) | OR 2.43 (1.37 to 4.32) |

| Hershberger101 | Proportion of sex protected (vaginal or unspecified) | SMD 0.08 (−0.07 to 0.22) |

| Iguchi95 | Improvement in condom use (dichotomous) | OR 1.03 (0.76 to 1.40) |

| Sorensen102 (maintenance group) | Proportion of sex protected (vaginal or unspecified) | SMD 0.661 (−0.397 to 1.718) |

| Sorensen102 (detoxification group) | Proportion of sex protected (vaginal or unspecified) | SMD 0.031 (−0.737 to 0.800) |

Secondary outcomes: condom use

High-quality trial results

There were no trials of sexual and intravenous drug behaviour change interventions reporting condom use outcomes that met all four quality criteria.

Other trial results

In 9 of the 13 condom use outcomes reported there was more condom use in the intervention group with three showing statistical significance (table 3).

Condom design interventions

Primary outcomes: pregnancy and STI

There were no trials of condom design interventions reporting primary (pregnancy or STI) outcomes.

Secondary outcomes: condom use

High-quality trial results

Golombok et al compared thicker condoms to thinner condoms and found that there was no difference in condom failure before or during sex (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.41) (table 4).103

Table 4.

Primary and secondary outcomes for condom design interventions

| Study | Type of intervention | Outcome | OR |

| (95% CI) | |||

| High quality trials | |||

| Golombok103 | Thicker vs thinner condom | Condom failure before/during sex | OR 1.06 (0.79 to 1.41) |

| Golombok103 | Thicker vs thinner condom | Condom failure during sex | OR 1.01 (0.70 to 1.47) |

| Golombok103 | Thicker vs thinner condom | Condom breakage before or during sex | OR 1.02 (0.66 to 1.58) |

| Golombok103 | Thicker vs thinner condom | Condom breakage during sex (over specified time period) | OR 0.94 (0.49 to 1.80) |

| Golombok103 | Thicker vs thinner condom | Full slippage during sex | OR 1.01 (0.70 to 1.47) |

| Golombok103 | Thicker vs thinner condom | Partial slippage during sex | OR 1.06 (0.64 to 1.76) |

| Other trials | |||

| Primary outcomes | |||

| Steiner104 | Choice of condoms | Any STI | OR 1.31 (0.80 to 2.15) |

| Secondary condom use outcomes | |||

| Joanis (C Joanis, M Weaver, C Toroitich-Ruto, et al, unpublished) | Choice of condoms | Proportion of sex protected | SMD −0.135 (−0.250 to −0.020) |

| Steiner104 | Choice of condom | Proportion of sex protected | SMD 0.110 (−0.082 to 0.303) |

| Benton105 | Swiss quality seal: Australian standard condom | Condom breakage during sex | OR 0.86 (0.49 to 1.49) |

| Benton105 | Swiss quality seal: Australian standard condom | Condom breakage during vaginal sex | OR 1.37 (0.65 to 2.89) |

| Benton105 | Swiss quality seal: Australian standard condom | Condom breakage during anal sex | OR 0.20 (0.04 to 0.92) |

| Renzi106 | Baggy condom: straight shafted condom | Condom breakage during sex (over specified time period) | OR 1.34 (0.46 to 3.89) |

| Renzi106 | Baggy condom: straight shafted condom | Slippage during sex | OR 0.85 (0.57 to 1.26) |

| Renzi106 | Female reality condom for anal sex | Breakage reported by men (receptive partners) | OR 1.71 (0.74 to 3.96) |

| Macaluso107 | Female reality condom for anal sex | Slippage reported by men (receptive partners) | OR 2.68 (1.92 to 3.75) |

| Macaluso107 | Female reality condom for anal sex | Slippage reported by men (insertive partner) | OR 34.10 (18.97 to 61.27) |

Other trial results

The Steiner 2006 trial compared providing participants with a choice of different types of condom to providing one type of condom and reported a OR consistent with an increase in acquisition of ‘any STI’ (OR 1.31, 95% CI 0.80 to 2.15) for the ‘choice of condom’ arm.104 The Benton 1997 trial105 reported that Swiss quality seal standard condoms were less likely to break during anal sex than Australian standard condoms, and the Renzi 2003 trial106 of the reality female condom for anal sex reported this was less likely to slip during anal sex than a standard condom (table 4).

Discussion

Summary of findings

This review included over 143 000 study participants from 139 trials promoting effective condom use. Despite these research efforts, this review cannot provide reliable estimates of the effectiveness of interventions in promoting condom use due to the high potential for bias in the effect estimates.

The potential for bias is high for three main reasons. First, trials were of low quality and only four trials met all the quality criteria. Effect estimates have been found to be higher in lower quality studies where there is no allocation concealment and the results of our subgroup analysis according to allocation concealment are consistent with this.9 Second, most trials relied only on self-reported condom use outcomes (85%). Only one of the trials meeting all four quality criteria also used an objective outcome measure. Third, a low proportion of trials reported data using the same outcomes measure. Among the most commonly used outcomes, only 10 trials (7%) reported data regarding the outcome ‘any STI’, 4 (3%) reported outcome data for pregnancy and 22 (16%) reported outcome data for ‘condom use at last sex’. This is likely to have resulted in an overestimate of effects due to selective reporting of outcomes where statistically significant benefit is found. Thus, while the results reported in the trials in this review are generally consistent with modest benefits, the effect estimates cannot be considered reliable.

In the entire review there was only one trial that met all the quality criteria and used a single objective condom use outcome measure.35 Furthermore, the intervention was unique and, thus, there is no potential for selective reporting of outcomes in other similar trials. This trial demonstrated that either giving condoms to clients in motels or providing them in motel rooms was effective in increasing condom use for commercial and non-commercial sex.

Strengths and limitations of the review

This is the first comprehensive systematic review and methodological appraisal of all interventions promoting effective condom use. Descriptions of the intervention components are limited as these were based on the trial reports, which varied considerably in detail. Our analysis of trial quality as a source of heterogeneity, according to blinding and allocation concealment, for the outcome ‘any STI’ has limited power as few trials contributed to this pooled analysis. The heterogeneity of effect estimates means it is more appropriate to view individual study results; pooled estimates according to study quality are presented to show that these findings are consistent with earlier studies.9 We had insufficient power to explore any other aspects of trial quality as sources of heterogeneity. Among the trials reporting an increase in ‘any STI’, both the Imrie et al24 and Boyer et al21 trials had adequate allocation concealment. Other potential sources of heterogeneity include the type of participants and features of the intervention such as the duration, components and educational media used in the interventions. For example, among the trials reporting an increase in ‘any STI’, Imrie et al recruited men who defined themselves as ‘gay’24 and Carey et al recruited patients attending outpatient psychiatric care.22 Imrie et al's intervention was the only trial that was a single session intervention.24 Many of the components addressed in trials of interventions reporting increases in ‘any STI’ were similar to those addressed in the interventions reporting beneficial effects (eg, information, attitudes, self-efficacy, condom use skills, condom negotiation skills, motivation),21 22 24 but Imrie et al's intervention did not involve personal risk assessment, which was addressed by five of the trials reporting beneficial effects.24 The interventions also used different educational methods. For example, neither Imrie et al nor Carey et al used videos, which were used in six of the interventions reporting beneficial effects.22 24 We did not have sufficient power to robustly explore the type of participants and the duration, components and educational media used in the interventions as sources of heterogeneity in this systematic review.

Sources of bias in the systematic review

First, low trial quality in this review is an important potential source of bias. Effect estimates have been found to be higher where there is no allocation concealment and the results of our subgroup analysis according to allocation concealment are consistent with this.9 Second, the use of self-reported condom use outcomes is likely to have resulted in bias. Interventions promoting sexual behaviour change may influence reporting regarding behaviour more than actual behaviour and where participants are not blind to the intervention there may be differential misreporting of outcomes between the intervention and control group. Third, a low proportion of trials reported sufficient data to calculate effect estimates using the same outcome measures. Of the most commonly reported outcomes, only ten trials (10%) reported data regarding the outcome ‘any STI’, four (4%) reported the outcome ‘pregnancy’ and 22 (16%) reported condom use at last sex outcomes. Furukawa et al conducted an analysis of Cochrane reviews in which a median of 46% of trials (IQR 20–75%) reported sufficient data to calculate effect estimates using the same outcome.13 They found that in systematic reviews where a low proportion of trials used the same outcomes the effect estimates were higher than in systematic reviews where a high proportion of trials used the same outcomes. This is caused by selective reporting of outcomes in trials where no statistically significant benefit is found.13 Therefore, the low proportion of trials using the same outcome measures in this systematic review is likely to have resulted in an over-estimate of effect estimates.

Implications for research

Standards of conduct and reporting for trials promoting effective condom use must urgently be agreed. Consensus must be reached regarding which outcomes must be included irrespective of other reported outcomes. All future trials must include an objective measure of STI or pregnancy so that the trial results can be meaningfully compared and, where relevant, can contribute to future meta-analyses of objective biological outcomes. The components of interventions should be clearly described within trial reports. Trial protocols must be registered in advance with clearly specified outcomes. Trials promoting effective condom use should follow the existing guidance for the reporting and conduct of RCTS.108

Implications for condom promotion interventions

Condom distribution proximal to the time of sex has been shown to increase condom use in one high-quality trial in one setting. Innovative alternate means of distributing condoms proximal to the time of sex, especially among high-risk groups, should be evaluated. A high-quality trial of the female reality condom for anal sex should be conducted as results from a low-quality trial suggest the female reality condom may be less likely to slip than a standard condom. Future sexual behaviour change interventions should be based on the content of existing interventions that report beneficial effects. Such interventions should be evaluated by an adequately powered high-quality RCT.

Conclusion

Increasing effective condom use is of global public health significance. Reported results in the trials in this review are generally consistent with modest benefits, but bias introduced by the poor quality of trials, reliance on self-reported outcomes and selective reporting of outcomes mean that the reported results are likely to be an over-estimate of effects. Robust conclusions regarding the effectiveness of interventions promoting effective condom use cannot be made. Future trials promoting effective condom use must be conducted and reported to the highest standards.

What is already known.

CONSORT standards for the conduct and reporting of trials are well-established.

What this paper adds.

Despite the public health importance of increasing condom use, there is little reliable evidence on the effectiveness of condom promotion interventions.

There is considerable potential for bias in trials of interventions promoting effective condom use due to poor trial quality.

Because of the low proportion of trials using the same outcome, the potential for bias from selective reporting of outcomes is also considerable.

Standards of conduct and reporting for trials promoting effective condom use must be agreed and consensus must be reached regarding which outcomes should be reported in all trials irrespective of other reported outcomes.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Contributors: CF and IR designed the study, reviewed electronic records and wrote the paper with comments from the other authors. CF, MF and FW extracted data and MF wrote to authors for missing or unclear data. CF, FW and TA cleaned and analysed the data.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.WHO Global prevalence and incidence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections: overview and estimates. World Health Organization: Geneva, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alan Guttmacher Institute Sharing responsibility: women, society and abortion. New York: Alan Guttmacher Institute, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS AIDS epidemic update. Geneva: UNAIDS, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farr G, Gabelnick H, Sturgen K, et al. Contraceptive efficacy and acceptability of the female condom. Am J Public Health 1994;84:1960–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spruyt A, Steiner MJ, Joanis C, et al. Identifying condom users at risk for breakage and slippage: findings from three international sites. Am J Public Health 1998;88:239–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shepherd J, Weston R, Peersman G, et al. Interventions for encouraging sexual lifestyles and behaviours intended to prevent cervical cancer (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 1. Oxford: Update Software, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Johnson WD, Hedges LV, Diaz RM. Interventions to modify sexual risk behaviors for preventing HIV infection in men who have sex with men (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 1. Oxford: Update Software, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Oakley A, Fullerton D, Holland J. Behavioral interventions for HIV/AIDS prevention. AIDS 1995;9:479–86 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care: assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ 2001;323:42–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan AW, Hrobjartsson A, Haahr MT, et al. Empirical evidence for selective reporting of outcomes in randomized trials: comparison of protocols to published articles. JAMA 2004;291:2457–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan AW, Altman DG. Identifying outcome reporting bias in randomized trials on PUBMED: review of publications and survey of authors. BMJ 2005;330:753–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williamson PR, Gamble C. Identification and impact of outcome selection bias in meta-analysis. Stat Med 2005;24:1547–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furukawa TA, Watanabe N, Omori IM, et al. Association between unreported outcomes and effect size estimates in Cochrane meta-analyses [Letter]. JAMA 2007;297:468–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barne R, Shey C, Wiysonge U, Kongynyuy E. Female condom for preventing HIV and sexually transmitted infections. Cochrane library 2008. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD003652/frame.html [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Chapter 6: Searching for studies. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.2 (updated September 2009). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2009. www.cochrane-handbook.org [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agresti A. An introduction to categorical data analysis. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Der Simonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayes RJ, Alexander ND, Bennett S, et al. Design and analysis issues in cluster-randomized trials of interventions against infectious diseases. Stat Methods Med Res 2000;9:95–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Chapter 9: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.2 (updated September 2009). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2009. www.cochrane-handbook.org [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyer P, Shafer M, Shaffer R, et al. Evaluation of a cognitive-behavioral, group, randomized controlled intervention trial to prevent sexually transmitted infections and unintended pregnancies in young women. Prev Med 2005;40:420–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyer CB, Barrett D, Peterman T, et al. Sexually transmitted disease (STD) and HIV risk in heterosexual adults attending a public STD clinic: evaluation of a randomized controlled behavioral risk-reduction intervention trial. AIDS 1997;11:359–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto S, et al. Reducing HIV-risk behavior among adults receiving outpatient psychiatric treatment: results from a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004;72:252–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Downs J, Murray P, Bruine de Bruin W, et al. Interactive video behavioral intervention to reduce adolescent females' STD risk: a randomized. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1561–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imrie J, Stephenson J, Cowan F, et al. A cognitive behavioural intervention to reduce sexually transmitted infections among gay men: randomised trial. BMJ 2001;322:1451–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmot LS, Braverman P, et al. HIV/STD risk reduction interventions for African American and Latino adolescent girls at an adolescent medicine clinic: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:440–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas J, et al. Efficacy of risk-reduction counselling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Project RESPECT Study Group. JAMA 1998;7:1161–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.NIMH Multisite HIV Prevention Trial Group The NIMH Multisite HIV Prevention Trial: reducing HIV sexual risk behavior. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Multisite HIV Prevention Trial Group. Science 1998;280:1889–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Donnell CR, O'Donnell L, Doval A, et al. Reductions in STD infections subsequent to an STD clinic visit. Using video-based patient education to supplement provider interactions. Sex Transm Dis 1998;25:161–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shain RN, Piper J, Newton E, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a behavioral intervention to prevent sexually transmitted disease among minority women. N Engl J Med 1999;340:93–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shain RN, Perdue ST, Piper JM, et al. Behaviors changed by intervention are associated with reduced STD recurrence: the importance of context in measurement. Sex Transm Dis 2002;29:520–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiClemente R, Wingwood G, Harrington K, et al. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;292:171–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Philliber S, Kaye J, Herrling S, et al. Preventing pregnancy and improving health care access among teenagers: an evaluation of the children's aid society-carrera program. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2002;34:244–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shlay JC, Mayhugh B, Foster M, et al. Initiating contraception in sexually transmitted disease clinic setting: a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:473–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wight D, Raab G, Henderson M, et al. Limits of teacher delivered sex education: interim behavioural outcomes from randomised trial. BMJ 2002;324:435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feldblum PJ, Hatzell T, Van Damme K, et al. Results of a randomised trial of male condom promotion among Madagascar sex workers. Sex Transm Infect 2005;81:166–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Branson BM, Peterman TA, Cannon R, et al. Group counseling to prevent sexually transmitted disease and HIV: a randomized controlled trial. Sex Transm Dis 1998;25:553–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen D, Dent C, MacKinnon D, et al. Condoms for men, not women. Results of brief promotion programs. Sex Transm Dis 1992;19:189–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DiClemente R, Wingwood G, Harrington K, et al. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;292:171–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.EXPLORE Study Team Effects of a behavioural intervention to reduce acquisition of HIV infection among men who have sex with men: the EXPLORE randomised controlled study. Lancet 2005;364:41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gollub EL, French P, Loundou A, et al. A randomized trial of hierarchical counseling in a short, clinic-based intervention to reduce the risk of Sex Transm Dis in women. AIDS 2000;14:1249–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harvey B, Stuart J, Swan T. Evaluation of a drama-in-education programme to increase AIDS awareness in South African high schools: a randomized community intervention trial. Int J STD AIDS 2000;11:105–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kamali A, Quigley M, Nakiyingi J, et al. Syndromic management of sexually-transmitted infections and behaviour change interventions on transmission of HIV-1 in rural Uganda: a community randomised trial. Lancet 2003;361:645–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shain RN, Piper J, Holden A, et al. Prevention of Gonorrhea and Chlamydia through behavioural intervention: results of two-year controlled randomized trial in minority women. Sex Transm Dis 2004;31:401–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Egger M, Pauw J, Lopatatzidis A, et al. Promotion of condom use in a high-risk setting in Nicaragua: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000;355:2101–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ehrhardt AA, Exner T, Hoffman S, et al. A gender-specific HIV/STD risk reduction intervention for women in a health care setting: short- and long-term results of a randomized clinical trial. AIDS Care 2002;14:147–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boekeloo BO, Schamus L, Simmens S, et al. A STD/HIV prevention trial among adolescents in managed care. Pediatrics 1999;103:107–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borgia P, Marinacci C, Schifano P, et al. Is peer education the best approach for HIV prevention in schools? Findings from a randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc Health 2005;36:508–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bryan AD, Aiken L, West S. Increasing condom use: evaluation of a theory-based intervention to prevent sexually transmitted diseases in young women. Health Psychol 1996;15:371–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fitzgerald AM, Standon B, Terreri N, et al. Use of Western-based HIV risk-reduction interventions targeting adolescents in an African setting. J Adolesc Health 1999;25:52–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kirby D, Korpi M, Adivi C, et al. An impact evaluation of project SNAPP: an AIDS and pregnancy prevention middle school program. AIDS Educ Prev 1997;9:44–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kvalem IL, Sundet J, Rivo KI, et al. The effect of sex education on adolescents' use of condoms: applying the Solomon four-group design. Health Educ Q 1996;23:34–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shrier LA, Ancheta R, Goodman E, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a safer sex intervention for high-risk adolescent girls. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001;155:73–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stanton B, Harris C, Cottrell L, et al. Trial of an urban adolescent sexual risk-reduction intervention for rural youth: a promising but imperfect fit. J Adolesc Health 2006;38:55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stanton B, Li X, Ricardo I, et al. A randomized, controlled effectiveness trial of an AIDS prevention program from low-income African-American youths. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1996;150:363–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stanton BF, Li X, Kahihuata J, et al. Increased protected sex and abstinence among Namibian youth following a HIV risk-reduction intervention: a randomized, longitudinal study. AIDS 1998;12:2473–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weeks K, Levy S, Gordon A, et al. Does parental involvement make a difference? The impact of parent interactive activities on students in a school-based AIDS prevention program. AIDS Educ Prev 1997;9:90–106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wenger NS, Greenberg JM, Hilborne LH, et al. Effect of HIV antibody testing and AIDS education on communication about HIV risk and sexual behavior. A randomized, controlled trial in college students. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:905–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu J, Jiyao W, Naiqing Z, et al. The effectiveness of an intervention program in the promotion of condom use among sexually transmitted disease patients. Chin J Epidemiol 2002;23:218–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Amirkhanian Y, Kelly J, Kabakachieva E, et al. A randomised social network HIV prevention trial with young men who have sex with men in Russia and Bulgaria. AIDS 2005;19:1897–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Balmer DH, Gikundi E, Nasio J, et al. A clinical trial of group counselling for changing high-risk sexual behaviour in men. Couns Psychol Q 1998;11:33–43 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cleary P, Van Devanter N, Steilen M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of an education and support program for HIV—infected individuals. AIDS 1995;9:1271–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fogarty LA, Heilig C, Armstrong K, et al. Long-term effectiveness of a peer-based intervention to promote condom and contraceptive use among HIV-positive and at-risk women. Public Health Rep 2001;116:103–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gielen AC, Fogarty L, Armstrong K, et al. Promoting condom use with main partners: A behavioral intervention trial for women. AIDS Behav 2001;5:193–204 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmot LS, Fong G. Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk-reduction interventions for African American adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;279:1529–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kelly JA, McAuliffe T, Sikkema K, et al. Reduction in risk behavior among adults with severe mental illness who learned to advocate for HIV prevention. Psychiatr Serv 1997;48:1283–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuchaisit C, Higginbotham N. An education intervention to increase the use of condoms for the prevention of HIV infection among male factory workers in Khon Kaen. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:13S [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mansfield CJ, Conroy M, Emans S, et al. A pilot study of AIDS education and counseling of high-risk adolescents in an office setting. J Adolesc Health 1993;14:115–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Orr DP, Langefeld C, Katz B, et al. Behavioral intervention to increase condom use among high-risk female adolescents. J Pediatr 1996;128:288–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scholes D, McBride C, Grothaus L, et al. A tailored minimal self-help intervention to promote condom use in young women: results from a randomized trial. AIDS 2003;17:1547–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Anonymous. The Voluntary HIV-1 Counseling and Testing Efficacy Study Group. Efficacy of voluntary HIV-1 counselling and testing in individuals and couples in Kenya, Tanzania, and Trinidad: a randomised trial. Lancet 2002;356:103–112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu Y, Stanton B, Galbraith J, et al. Sustaining and broadening intervention impact: a longitudinal randomized trial of 3 adolescent risk reduction approaches. Pediatrics 2003;111:32–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Choi K, Lew S, Vittinghoff E, et al. The efficacy of brief group counseling in HIV risk reduction among homosexual Asian and Pacific Islander men. AIDS 1996;10:81–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Sikkema KJ, et al. Community and HIV Prevention Research Network. Randomised, controlled, community-level HIV-prevention intervention for sexual-risk behaviour among homosexual men in US cities. Community HIV Prevention Research Collaborative. Lancet 1997;350:1500–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roffman RA, Picciano J, Ryan R, et al. HIV-prevention group counseling delivered by telephone: an efficacy trial with gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav 1997;1:137–54 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rosser BR, Bockting W, Rugg D, et al. A randomized controlled intervention trial of a sexual health approach to long-term HIV risk reduction for men who have sex with men: effects of the intervention on unsafe sexual behaviour. AIDS Edu Prev 2002;14:59–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tudiver F, Myers T, Kurtz R, et al. The talking sex project: Results of a randomized controlled trial of small-group AIDS education for 612 gay and bisexual men. Eval Health Prof 1992;83:26–42 [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Comulada S, et al. Prevention for substance-using HIV-positive young people telephone and in-person delivery. Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004;37:S68–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Belcher L, Kalichman S, Topping M. A randomized trial of a brief HIV risk reduction counseling intervention for women. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998;66:856–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Greenberg J, Hennessy M, MacGowan R, et al. Modeling intervention efficacy for high-risk women. The WINGS Project. Eval Health Prof 2000;23:123–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kalichman SC, Browne-Sperling F, Cherry C. Effectiveness of a video-based motivational skills-uilding HIV risk-reducation intervention for inner-city African American men. J Consult Clin Psychol 1999;67:959–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kelly JA, Murphy D, Washingtom C, et al. The effects of HIV/AIDS intervention groups for high-risk women in urban clinics. Am J Public Health 1994;84:1918–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sikkema KJ, Winett R, Lombard D. DeveNot Found In Databaselopment and evaluation of an HIV-risk reduction program for female college students. AIDS Educ Prev 1995;7:145–59 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.St Lawrence JS, Crosby R, Belcher L, et al. Sexual risk reduction and anger management interventions for incarcerated male adolescents: A randomized controlled trial of two interventions. J Sex Educ Ther 1999;24:9–17 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Weinhardt L, Carey M, Carey K, et al. Increasing assertiveness skills to reduce HIV risk among women living with a severe and persistent mental illness. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998;66:680–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Gilbert L, et al. The efficacy of a relationship-based HIV/STD prevention program for heterosexual couples. Am J Public Health 2003;93:963–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention to reduce HIV transmission risks in HIV-positive people. Am J Prev Med 2001;21:84–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.O'Leary A, Ambrose T, Raffaelli M, et al. Effects of an HIV risk reduction project on sexual risk behavior of low-income STD patients. AIDS Educ Prev 1998;10:483–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hobfoll S, Jackcon A, Lavin J, et al. Reducing inner-city women's AIDS risk activities: a study of single, pregnant women. Health Psychol 1994;13:397–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bellingham K, Gillies P. Evaluation of an AIDS education programme for young adults. J Epidemiol Community Health 1993;47:134–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Picciano J, Roffman R, Kalichman S, et al. A telephone based brief intervention using motivational enhancement to facilitate HIV risk reduction among MSM: A pilot study. AIDS Behav 2001;5:251–62 [Google Scholar]

- 91.Robert B, Rosser S. Evaluation of the efficacy of AIDS education interventions for homosexually active men. Health Educ Res 1990;5:299–308 [Google Scholar]

- 92.Stephenson JM, Strange V, Forrest S, et al. RIPPLE study team Pupil-led sex education in England (RIPPLE study): cluster-randomised intervention trial. Lancet 2004;364:338–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Swanson JM, Dibble S, Chapman L. Effects of psycho-educational interventions on sexual health risks and psycho-social adaptation in young adults with genital herpes. J Adv Nurs 1999;29:840–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tripiboon D. A HIV/AIDS prevention program for married women in rural northern Thailand. Aust J Prim Health 2001;7:83–91 [Google Scholar]

- 95.Iguchi MY, Bux D, Lidz V, et al. Changes in HIV risk behavior among injecting drug users: the impact of 21 versus 90 days of methadone detoxification. AIDS 1996;10:1719–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Avants SK, Usubiaga M, Doebrick C. Targeting HIV-related outcomes with intravenous drug users maintained on methadone: a randomized clinical trial of a harm reduction group therapy. J Subst Abuse Treat 2004;26:67–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cottler LB, Compton W, Abdallah A, et al. Peer-delivered interventions reduce HIV risk behaviors among out-of-treatment drug abusers. Public Health Rep 1998;113:31–41 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Eldridge GD, St Lawrence J, Little C, et al. Evaluation of the HIV risk reduction intervention for women entering inpatient substance abuse treatment. AIDS Educ Prev 1997;9:62–76 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kotranski L, Semaan S, Collier K, et al. Effectiveness of an HIV risk reduction counseling intervention for out-of-treatment drug users. AIDS Educ Prev 1998;10:19–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Margolin A, Avants K, Warburton LA, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a manual-guided risk reduction intervention for HIV-positive injection drug users. Health Psychol 2003;22:223–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hershberger SL, Wood M, Fisher D. A cognitive-behavioral intervention to reduce HIV risk behaviors in crack and injection drug users. AIDS Behav 2003;7:229–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sorensen JL, London J, Heitzmann C, et al. Psychoeducational group approach: HIV risk reduction in drug users. AIDS Edu Prev 1994;6:95–112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Golombok S, Harding R, Sheldon J. An evaluation of a thicker versus a standard condom with gay men. AIDS 2001;15:245–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Steiner MJ, Hylton-Kong T, Figueroa JP, et al. Does a choice of condoms impact sexually transmitted infection incidence? A randomized, controlled trial. Sex Transm Dis 2006;33:31–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Benton KW, Jolley D, Smith A, et al. An actual use comparison of condoms meeting Australian and Swiss standards: results of a double-blind crossover trial. Int J STD AIDS 1997;8:427–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Renzi C, Tabet S, Stucky J, et al. Safety and acceptability of the reality condom for anal sex among men who have sex with men. AIDS 2003;17:727–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Macaluso M, Blackwell R, Carr B, et al. Safety and acceptability of a baggy latex condom. Contraception 2000;61:217–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA 1996;276:637–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]