Abstract

RasC is required for optimum activation of adenylyl cyclase A and for aggregate stream formation during the early differentiation of Dictyostelium discoideum. RasG is unable to substitute for this requirement despite its sequence similarity to RasC. A critical question is which amino acids in RasC are required for its specific function. Each of the amino acids within the switch 1 and 2 domains in the N-terminal portion of RasG was changed to the corresponding amino acid from RasC, and the ability of the mutated RasG protein to reverse the phenotype of rasC− cells was determined. Only the change from aspartate at position 30 of RasG to alanine (the equivalent position 31 in RasC) resulted in a significant increase in adenylyl cyclase A activation and a partial reversal of the aggregation-deficient phenotype of rasC− cells. All other single amino acid changes were without effect. Expression of a chimeric protein, RasG1–77-RasC79–189, also resulted in a partial reversal of the rasC− cell phenotype, indicating the importance of the C-terminal portion of RasC. Furthermore, expression of the chimeric protein, with alanine changed to aspartate (RasG1–77(D30A)-RasC79–189), resulted in a full rescue the rasC− aggregation-deficient phenotype. Finally, the expression of either a mutated RasC, with the aspartate 31 replaced by alanine, or the chimeric protein, RasC1–78-RasG78–189, only generated a partial rescue. These results emphasize the importance of both the single amino acid at position 31 and the C-terminal sequence for the specific function of RasC during Dictyostelium aggregation.

Keywords: Adenylate Cyclase (Adenylyl Cyclase), Chemotaxis, Cyclic AMP (cAMP), Ras, Signal Transduction, Adenylyl Cyclase Activation, RasC, RasG

Introduction

The Ras subfamily proteins are monomeric GTPases that act as molecular switches, cycling between an active GTP-bound and an inactive GDP-bound state (1). Activation is controlled by guanine nucleotide exchange factors that catalyze the exchange of GDP for GTP, and inactivation is regulated by GTPase-activating proteins that stimulate the hydrolysis of bound GTP to GDP (1). Activated Ras proteins stimulate numerous downstream signaling pathways that regulate a wide range of cellular processes, including proliferation, cytoskeletal function, chemotaxis, and differentiation (2). The diversity of signaling pathways and the complexity of their regulation is emphasized by the presence of a large number of mammalian Ras subfamily homologues with high levels of sequence identity (3), and elucidation of the roles played by each Ras protein remains a formidable challenge. In particular, there is relatively little information about the amino acid sequences that determine Ras protein functional specificity. An important approach to this problem is the analysis of Ras protein function in organisms amenable to genetic manipulation.

The Dictyostelium discoideum genome encodes 14 Ras subfamily members, an unusually large number for such a relatively simple organism (4, 5). Six of these have been partially characterized, and each has been shown to be required for a specific repertoire of functions (5–8). RasC and RasG are the best characterized of these proteins. Both are activated in response to cAMP during aggregation (9) and play important roles in signal transduction during aggregation (10, 11). rasC− cells fail to aggregate and exhibit a major defect in the cyclic AMP relay, whereas rasG− cells exhibit a delay in aggregation and reduction in cAMP chemotaxis. There is, however, some overlap of signaling function between the two proteins in that a disruption of both the rasC and the rasG genes is necessary to generate a total loss of cAMP-mediated signaling (10, 11). Thus, all cAMP signal transduction during early development appears to be partitioned between pathways that use either RasC or RasG.

A simple quantitative assay for cAMP relay is the activation of the adenylyl cyclase, ACA,2 as measured by the accumulation of cAMP in response to a pulse of 2′-deoxy-cAMP. In rasC− cells, ACA activation is reduced to a very low level, indicating the importance of RasC for relaying the cAMP signal. We used this assay to examine which amino acid residues in RasC are required for specific functions.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Development

Strain JH10 was grown at 22 °C in HL5 medium (14.3 g of peptone, 7.15 g of yeast extract, 15.4 g of glucose, 0.96 g of Na2HPO4·7H2O, and 0.486 g of KH2PO4/liter of water), supplemented with 50 mg/ml streptomycin sulfate (Sigma) and 100 μg/ml thymidine (Sigma) in Nunc tissue culture dishes (Nunc, Rochester, NY). The rasC− cells were grown in HL5 medium, supplemented with 50 mg/ml streptomycin sulfate but without the thymidine supplement. The rasC−/[rasC]:RasG and all other transformants were grown in HL5 medium supplemented with 10 μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen). Cells were routinely grown to a density of ∼4 × 105 cells/cm2 on tissue culture dishes and then harvested by pipetting. For all transformations, 20 μg of the appropriate expression vector (see supplemental Table S1) was electroporated into Dictyostelium cells as described previously (12).

To observe aggregation streaming, vegetative cells were harvested, washed twice in Bonner's salts, seeded at ∼4 × 105 cells/cm2 in Nunc tissue culture dishes submerged under Bonner's salts, and incubated at 22 °C. Strains were photographed at 10 h following the onset of starvation using a Leica DMIL inverted microscope and LEICA DFC 350F camera.

cAMP Accumulation

cAMP production was measured by a previously described method (13). Vegetative cell suspensions were centrifuged (500 × g, 5 min), washed twice in KK2 (20 mm potassium phosphate, pH 6.1), and resuspended in KK2 to a final density of 5 × 106 cells/ml. 30 ml of this cell suspension was shaken at 150 rpm for 1 h and then pulsed every 6 min for 5 h, with 100 μl of cAMP to a final concentration of 50 nm using a polystaltic pump (Buchler, Fort Lee, NJ) and a laboratory controller timer (VWR, Mississauga, ON, Canada). Cells were then centrifuged (500 × g, 5 min), washed two times with KK2, and resuspended at a density of 6.25 × 107 cells/ml. The cell suspension was stimulated with 10 μm 2′-deoxy cAMP, and 100-μl samples were lysed at intervals by the addition of 100 μl of 3.5% perchloric acid and 50 μl of 50% saturated KHCO3. cAMP levels were then measured using a cAMP-binding protein assay kit (Amersham Biosciences TRK432).

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were harvested by centrifugation and lysed in 1× Laemmli SDS-PAGE loading buffer (6× buffer: 350 mm Tris-Cl, pH 6.8, 10% SDS, 600 mm DTT, 0.012% w/v bromphenol blue, 30% glycerol). Samples were then boiled at 100 °C for 5 min, and protein concentrations were determined using the protein assay from Bio-Rad. Equal amounts of protein were fractionated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (14). After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose (Amersham Biosciences) membranes, blocked with a 5% nonfat milk solution, and probed with the appropriate antibody. Levels of Ras protein were quantified approximately by densitometry (VersaDoc imaging system, model 5000, Bio-Rad). To confirm that proteins had been equally loaded, the gels were also stained with Coomassie Blue solution (0.025% w/v Coomassie G-250, 10% v/v acetic acid).

Vector Construction

A full description of the plasmids and primers used during the course of this study is given in supplemental Tables S1 and S2. The prasC:rasC vector was generated by ligating the BamHI-XhoI-excised fragment of rasC cDNA from pGEM-rasC into BglII-XhoI restriction sites of prasC plasmid. The pBM2 (rasC:rasG) vector was generated by ligating the BamHI-SalI-excised fragment of rasG cDNA from pGEM-rasG into BglII-XhoI restriction sites of prasC.

Site-directed mutants of rasC or rasG were generated using either pGEM-rasC or pGEM-rasG as templates and the oligonucleotide pairs of MC3-F and MC3-R or MG1–9-F and MG1–9-R, respectively, in accordance with the Stratagene PfuTurbo DNA polymerase-based protocol (see supplemental Table S2). pBMC3 expression plasmid was generated by ligating the BamHI-XhoI-excised fragment of pGEM-MC3 into BglII-XhoI of prasC. pBMG1–9 expression plasmids were generated by ligating the BamHI-SalI-excised fragment of pGEM-MG1–9 into BglII-XhoI of prasC.

RasG was also modified by two block switches of sequence with RasC. This was accomplished by ligating DNA coding the first 78 amino acids of RasC to DNA encoding amino acids 78–189 of RasG (designated CSA). In addition, a chimeric construct encoding amino acids 1–77 of RasG and 79–189 of RasC was generated (designated CSB). In more detail, to generate pBCSA and pBCSB chimeric constructs, the following strategy was employed. The primers PBRC3-F, PBRC78-R+G overhang, PBRC79-F, and PBRC3-R were used to generate two amplified products of C1 (nucleotides 1–234) and C2 (nucleotides 235–570) from rasC cDNA as template. The primers PBRG10-F, PBRG77-R+C overhang, PBRG78-F, and PBRG8-R were used to generate two amplified PCR products of G1 (nucleotides 1–231) and G2 (nucleotides 232–570) from rasG cDNA as template. The 50-μl reactions were performed in PCR tubes using the standard PCR protocol except that PfuTurbo DNA polymerase was used instead of Taq DNA polymerase to prevent the A-tailing, which would have prevented the proper subsequent cloning. After completion, the amplified products were gel-purified and subjected to a second round of standard amplification. Reactions were performed in 40-μl mixtures in PCR tubes containing 5 μl of 10× PfuTurbo buffer, 2.5 μl of 2.5 mm dNTPs, 1 μl of PfuTurbo DNA polymerase (2.5 units/μl), 200 ng of each gel-purified and amplified DNA (C1 and G2) or (G1 and C2), and double distilled H2O to 40 μl. The procedure was interrupted after 10 cycles to add 5 μl each of the PBRC3-F and PBRG8-R primers or the PBRG10-F and PBRC3-R primers, respectively. The resulting products, CSA (C1+G2) and CSB (G1+C2), were gel-purified and then subjected to standard amplification using Taq DNA polymerase and the PBRC3-F and PBRG8-R primers or the PBRG10-F and PBRC3-R primers, respectively. The PCR-amplified products were gel-purified and cloned by T/A ligation into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI) to generate pGEM-CSA and pGEM-CSB. pBCSA and pBCSB were generated by ligating the BglII-SalI fragment of pGEM-CSA and the BamHI-XhoI fragment of pGEM-CSB into BglII-XhoI of the prasC expression plasmid.

RESULTS

Dictyostelium rasC− cells exhibit a very dramatic developmental phenotype; upon starvation, they fail to aggregate (7, 10). This phenotype is predominantly due to the low level of cAMP generated in response to a stimulus of 2′-deoxy-cAMP. The activation of ACA provides a quantitative assay (7, 10) to determine which amino acids are specifically required for RasC function during aggregation.

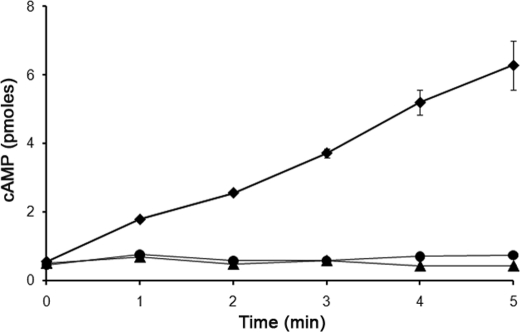

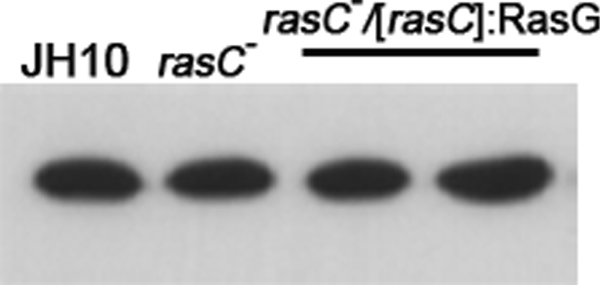

rasC− cells express wild type levels of RasG (10) and generate wild type levels of activated RasG in response to 2′-deoxy-cAMP (11), indicating that RasG cannot substitute for RasC despite the similarities in their amino acid sequences. To understand the basis of RasC specificity, the experimental rationale was to systematically change the amino acids of RasG to match the corresponding amino acids in RasC. As a first step, we determined whether in rasC− cells, expression from an exogenous unmutated rasG gene would enhance the activation of ACA. Because RasG is expressed maximally during growth and is then subsequently down-regulated during aggregation (15, 16), whereas RasC expression increases during early development (7), the rasG gene was expressed from the rasC promoter to ensure maximum RasG expression during aggregation. G418-resistant rasC−/[rasC]:RasG transformants were isolated and subjected to Western blotting to determine RasG protein levels. Some transformants exhibited no increase in the level of RasG protein, whereas others exhibited a slight increase, once again indicating that RasG protein levels in the cell are highly regulated (17), even when exogenous rasG is expressed from the rasC promoter. Two rasC−/[rasC]:RasG transformants, one with the same RasG protein level as the rasC− cells and one with a slightly higher protein level (Fig. 1), were selected and subjected to further analysis. Neither of the transformants aggregated when plated in plastic dishes under non-nutrient buffer (data not shown), and neither exhibited an increase in cAMP accumulation in response to 2′-deoxy-cAMP, relative to that observed in rasC− cells (Fig. 2), indicating that the slight increase in RasG protein level was not able to substitute for the absence of RasC.

FIGURE 1.

Western blot analysis of RasG protein levels. Lysates (10 μg of protein) of vegetative cells of the parental JH10, rasC−, and rasC−/[rasC]:RasG cells were subjected to Western blot analysis, using RasG-specific antibodies. Levels were quantified by densitometry, and for the rasC−/[rasC]:RasG transformants, levels were 1.0 and 1.15, respectively, relative to the JH10 control.

FIGURE 2.

cAMP accumulation in rasC− strains expressing RasG. Cells of strains JH10 (♦), rasC− (▲), and rasC−/[rasC]:RasG (●) were pulsed with cAMP for 5 h, washed, and stimulated with 2′-deoxy cAMP, and samples taken at the indicated times were assayed for cAMP accumulation as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The means and standard deviations for three independent experiments are shown.

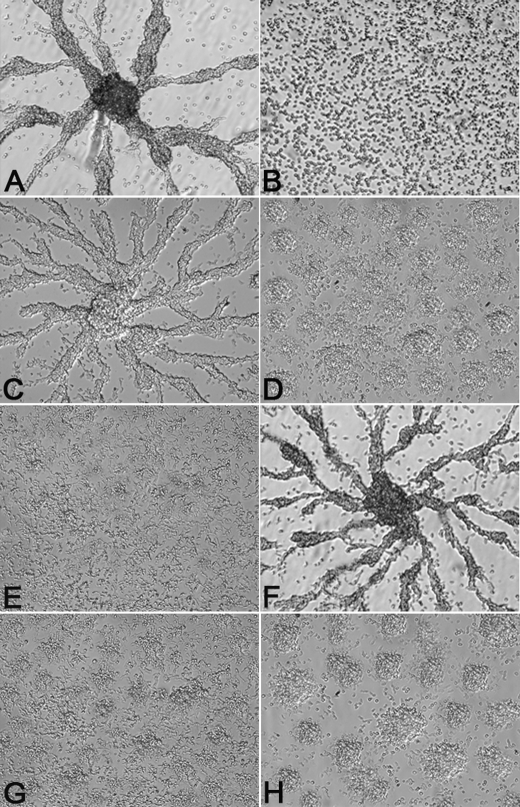

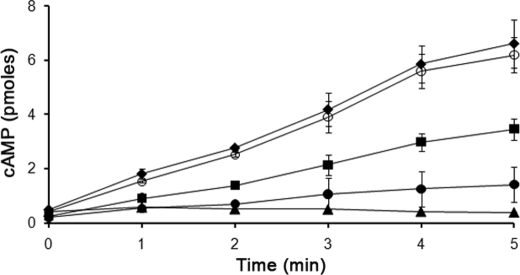

The finding that neither the absence of aggregation of the rasC− cells nor ACA activation could be compensated by the expression of exogenous RasG provided an experimental base line to determine whether any amino acid substitution in the RasG molecule could generate a gain of function in ACA activation and rescue the aggregation-deficient phenotype. Because RasC and RasG have a total of nine amino acid differences in the switch I domain and in the region flanking the switch II domain (Table 1), regions that have been shown to be important for Ras/effector interactions (18), RasG was modified by mutating cloned versions of the rasG gene, leading to individual substitution of each of the nine non-conserved amino acids with the corresponding amino acids from RasC. The resulting nine constructs were each transformed into rasC− cells, and five clones from each transformation were analyzed by Western blotting with the RasG antibody. Transformants contained either RasG protein levels that were similar to those found in the rasC− cells or slightly increased RasG protein levels (data not shown). Each of the isolated clones was tested for its ability to aggregate on plastic under non-nutrient buffer. Transformants with one of the nine mutations, aspartate at position 30 of RasG changed to the alanine at the equivalent position 31 of RasC, (rasC−/[rasC]:RasGD30A), formed small aggregates (Fig. 3D) but no aggregation streams typical of wild type (Fig. 3A) or fully rescued rasC− cells (Fig. 3C). Transformants expressing the remaining mutations showed no sign of aggregation (data not shown), results identical to that for the rasC− cell (Fig. 3B). Three transformants containing each type of mutation (one with same level of RasG protein and two with a slight increase in RasG protein) were analyzed for 2′-deoxy-cAMP stimulation of ACA activity. The rasC−/[rasC]:RasGD30A transformants were the only single amino acid change transformants that exhibited increase in cAMP accumulation in response to a stimulus of 2′-deoxy-cAMP (Fig. 4). All the others exhibited levels of cAMP accumulation that were not significantly higher than that of the rasC− cells (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Amino acid comparison of switch I and switch II regions of RasC and RasG

| Protein | Region | Amino acid sequencea |

|---|---|---|

| RasG | Switch I | 22QLIQNHFIDEYDPTIEDSY40 |

| RasC | Switch I | 23QLTQNQFIAEYDPTIENSY41 |

| RasG | Switch II | 50TCLLDILDTAGQEEYSAMRDQYMRT74 |

| RasC | Switch II | 51VYMLDILDTAGQEEYSAMRDQYIRS75 |

a The sequences 22–40 (switch I) and 50–74 (switch II) of RasG were aligned with the sequences 23–41 (switch I) and 51–75 (switch II) of RasC. Amino acid differences are shown in bold.

FIGURE 3.

Aggregation on plastic of rasC− cells expressing mutated RasG and RasC proteins. Strains JH10 (A), rasC− (B), rasC−/[rasC]:RasC (C), rasC−/[rasC]:RasGD30A (D), rasC−/[rasC]:RasG1–77-RasC79–189 (E), rasC−/[rasC]:RasG1–77(D30A)-RasC79–189 (F), rasC−/[rasC]:RasCA31D (G), and rasC−/[rasC]:RasC1–78-RasG78–189 (H) were seeded as monolayers in Nunc tissue culture dishes submerged under Bonner's salts solution and assayed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Single experiments are shown, but the results for the various strains were highly reproducible.

FIGURE 4.

cAMP accumulation in rasC− strains expressing modified RasG. Cells of strains JH10 (♦), rasC −/[rasC]:RasG1–77(D30A)-RasC79–189 (○), rasC−/[rasC]:RasGD30A (■), rasC−/[rasC]:RasG1–77-RasC79–189 (●), and rasC− (▲) were pulsed with cAMP for 5 h, washed, and stimulated with 2′-deoxy cAMP, and samples were taken at the indicated times were assayed for cAMP accumulation as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The means and standard deviations for three independent experiments are shown.

To determine whether any other amino acids in the RasC protein were important for the restoration of RasC signaling function during aggregation, we generated a chimeric construct encoding amino acids 1–77 of RasG and 79–189 of RasC under the control of the rasC promoter. This chimeric construct was transformed into rasC− cells, and several G418-resistant isolates were analyzed for their ability to aggregate and activate ACA. The rasC−/[rasC]:RasG1–77-RasC79–189 transformants showed no aggregation streams (Fig. 3E) but did accumulate 20% of the wild type level of cAMP in response to the 2′-deoxy-cAMP stimulation (Fig. 4). This slight ACA activation suggests a role for the C-terminal portion of the RasC molecule in its function. In view of the apparent importance of both the amino acid at the equivalent of position 30 and the C-terminal portion of the RasC molecule, we next generated a chimeric construct comprising the N-terminal portion of RasG, containing the single change of aspartate to alanine at position 30, and the C-terminal portion of RasC. Transformation of this construct ([rasC]:RasG1–77(D30A)-RasC79–189) into rasC− resulted in cells that exhibited normal aggregation (Fig. 3F) and wild type levels of ACA activation (Fig. 4). This result confirms that the alanine at position 31 of RasC (the equivalent of amino acid 30 in RasG) is the only amino acid in the N-terminal portion of the molecule that is important for signal transduction through RasC, leading to ACA activation, and confirms the importance of the C-terminal portion of the protein.

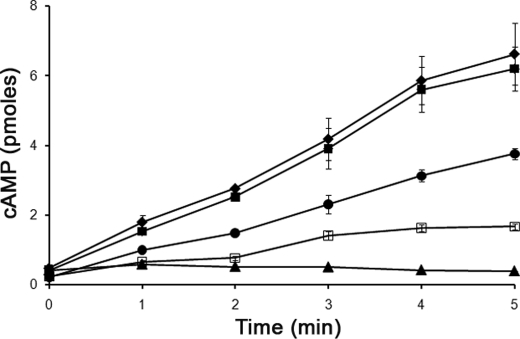

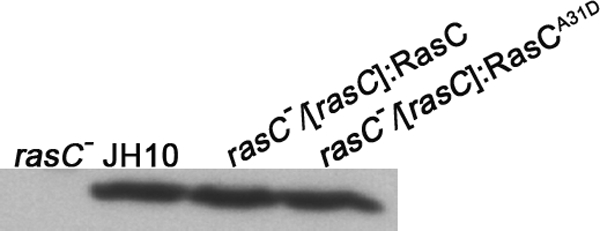

To confirm and extend these observations, we determined which changes in the RasC molecule would result in a loss of function. To this end, the alanine at position 31 of RasC was changed to aspartate, the corresponding amino acid of RasG. When this mutated rasC gene was expressed in rasC− cells, the resulting transformants (rasC−/[rasC]:RasCA31D) produced only very small aggregates, with no sign of aggregation streams (Fig. 3G), and a level of ACA activation that was considerably lower than that resulting from the expression of the non-mutated rasC gene (Fig. 5). This poor activation of ACA and poor aggregation were not the result of a low expression of the rasCA31D gene (Fig. 6). Thus, the single amino acid change at position 31 of RasC generated a loss of function. In addition, DNA encoding the first 78 amino acids of RasC was ligated to DNA encoding amino acids 78–189 of RasG, and this construct was transformed into rasC− cells. The rasC−/[rasC]:RasC1–78-RasG78–189 cells produced only small aggregates (Fig. 3H) and an activation of ACA that was ∼50% of that produced by the intact RasC molecule (Fig. 5), emphasizing the importance of the C-terminal portion of the molecule for its function.

FIGURE 5.

cAMP accumulation in rasC− strains expressing modified RasC. Cells of strains JH10 (♦), rasC−/[rasC]:RasC (■), rasC−/[rasC]:RasC1–78-RasG78–189 (●), rasC−/[rasC]:RasCA31D (□), and rasC− (▲) were pulsed with cAMP for 5 h, washed, and stimulated with 2′-deoxy cAMP, and samples taken at the indicated times were assayed for cAMP accumulation as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The means and standard deviations for three independent experiments are shown.

FIGURE 6.

Western blot analysis of RasC protein levels. Lysates (10 μg of protein) of vegetative cells of rasC−, JH10, rasC−/[rasC]:RasC, and rasC−/[rasC]:RasCA31D cells were subjected to Western blot analysis, using RasC-specific antibodies. Levels were quantified by densitometry and found to be the same for all three samples. A single experiment is shown, but identical results were observed for two additional experiments.

DISCUSSION

We have shown previously that RasG and RasC perform distinct functions during aggregation (10, 11). There is clearly a bifurcation of the signaling pathways, with signaling through RasC being more important for the regulation of ACA activation and signaling through RasG more important for the regulation of chemotaxis, although there does appear to be some overlap of function. This separation of signaling function is almost certainly due to differences in the interaction of the Ras proteins with their downstream effectors. For example, the Ras binding domains (RBDs) of Dictyostelium PI3K1 and PI3K2 bind more effectively to RasG than to RasC (9), consistent for the proposed roles for PI3K and RasG in establishing polarity and regulating chemotaxis (10, 11). However, there is as yet no direct binding data to indicate the nature of any downstream effectors that have high affinity for RasC. Genetic analyses suggest that the Ras-interacting protein-3 (Rip-3) is required for aggregation and ACA activation (19, 20), functions that also require RasC (7). In addition, both RasC and Rip-3 are important for the functioning of the TORC2 complex, which is necessary for optimum ACA activation and chemotaxis (19, 20). However, this presumptive connection between Rip-3 and RasC is confounded by the fact that Rip-3 interacts strongly with RasG but does not interact with RasC in yeast two-hybrid analyses (20) and that Rip-3 binds to RasG but does not bind to RasC in an RBD-Rip-3 pulldown assay.3 Thus, the signaling pathway that links RasC and ACA activation is still not entirely clear.

As an approach to the question of what determines the bifurcation of the signaling pathways through either RasG or RasC, we set out to establish the amino acid determinants that are responsible for RasC and RasG specificity. The requirement of RasC for the maximal activation of ACA in response to 2′-deoxy-cAMP provided an assay for determining the amino acids necessary for RasC specificity. These assays revealed the importance of a single amino acid in the N-terminal portion of the RasC molecule. The replacement of the aspartate at amino acid 30 of RasG by alanine, the corresponding amino acid at position 31 of RasC, was the only single amino acid change of those studied that generated a gain of function. That the alanine at position 31 of RasC was the only important one in the N-terminal portion of the RasC molecule was confirmed by the finding that a fusion of the intact N-terminal portion of RasC to the C-terminal portion of RasG did not enhance the level of ACA activation above that obtained by the single change of aspartate to alanine in RasG (Fig. 5 compared with Fig. 4). The importance for specificity of the alanine at position 31 of RasC was confirmed by the finding that the expression of RasG1–77(D30A)-RasC79–189 restored full ACA activation, whereas the single change of alanine to aspartate in RasC resulted in a reduced activation.

The effect of single amino acid changes on Ras protein function has been the subject of several studies in mammalian cells. Mutational changes in the Ha-Ras protein that differentially altered its binding of the protein to Ras effectors was determined by yeast two-hybrid analysis, and the effects of these mutations on the ability of constitutively activated Ha-Ras to malignantly transform mammalian cells were determined (21). Mutations at amino acids 35 and 37 both reduced transformation considerably. In a follow-up study, the effects of mutations on three properties that accompanied Ha-Ras-induced malignant transformation were determined (22). It was found that a mutation at position 35 prevented MAP kinase activation but had no effect on membrane ruffling and DNA synthesis, whereas a mutation at amino acid 40 had an effect on MAP kinase activation and DNA synthesis but no effect on membrane ruffling (22). In subsequent studies, the importance of Ral GTPase dissociation stimulator and PI3K as downstream effectors of Ras-induced transformation was delineated with the help of the single amino acid mutations (23, 24). In particular, mutations at amino acids 35, 37, 38, and 40 all had differential effects on Ras binding to Raf, Ral-GDS, and PI3K. In other studies, the amino acids that are specific for Ha-Ras, relative to mammalian Rap1, were altered to the Rap1 equivalents either singly or in pairwise combinations because constitutively activated Rap1 does not induce malignant transformation (25). Changes at amino acids 26, 27, 31, 32, and 45 all reduced the transformation potency of Ha-Ras, with the change of amino acid 45 having the most pronounced effect and the pairwise change at amino acids 30 and 31 having the least drastic effect.

None of the amino acids found to be important for malignant cell transformation by constitutively activated Ha-Ras are important for RasC specificity in Dictyostelium. RasG and RasC are identical at positions 27, 29, 35, 37, and 40, and so these amino acids are clearly unimportant for RasC specificity and, although the amino acids at positions 26, 29, and 38 of RasG are different from those in the corresponding positions in RasC, changing these amino acids to the RasC-specific ones did not enhance the ability of RasG to activate ACA. Amino acid 45, identified by the mammalian Ras studies as being important for specificity, is different in RasC and RasG, but we did not determine the effect of such a change because the replacement of the N-terminal portion of RasG with the N-terminal portion of RasC did not enhance ACA activation beyond that observed with the single amino acid change at position 30.

Although the Ras amino acid replacement studies in mammalian cells generated important information, they suffer from the fact that they were based on the ectopic expression of the constitutively activated Ha-Ras protein that, in many cases, was produced at aberrantly high levels and often mislocalized within the cell. This high expression of constitutively activated Ha-Ras could be interfering with the functions of other Ras proteins, and it has been suggested that these studies need to be repeated under more physiological conditions (26). The studies on Dictyostelium Ras protein specificity reported here do not suffer from these limitations because they are based on the rescue of a normal function, using physiological levels of ectopically expressed protein.

Our studies have also emphasized the importance of the C-terminal sequence of RasC in determining specificity. The limited restoration of ACA activation in rasC−/[rasC]:RasC1–78-RasG78–189 transformed cells indicates that although the amino acid 31 of RasC is a key determinant for its specificity, the C-terminal portion of the RasC molecule is also important. The unique role for each of the Dictyostelium Ras proteins may, therefore, be partially specified by the C-terminal hypervariable regions, playing important roles in localization. It is well established that the C-terminal portion of the mammalian Ras family proteins is important for localization within the cell (27), and the finding that the C-terminal portion of RasC molecule plays a role in functional specificity in Dictyostelium implies that the spatial separation of RasG and RasC may play an important role in the signal bifurcation. Consistent with this interpretation, PI3K activation occurs at the leading edge of a migrating cell and probably specifically involves RasG, whereas ACA activation occurs at the trailing end and specifically involves RasC. The study of the specific roles that RasG and RasC play in live cells is currently hampered by the lack of specific reagents that can uniquely identify activated RasC and activated RasG. Creating such specific reagents would be an important step for our future understanding.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (to G. W.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2.

H. Kae and G. Weeks, unpublished observations.

- ACA

- adenylyl cyclase

- 2′-deoxy-cAMP

- 2′-deoxyadenosine-monophosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mitin N., Rossman K. L., Der C. J. (2005) Curr. Biol. 15, R563–R574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell S. L., Khosravi-Far R., Rossman K. L., Clark G. J., Der C. J. (1998) Oncogene 17, 1395–1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reuther G. W., Der C. J. (2000) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12, 157–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eichinger L., Pachebat J. A., Glöckner G., Rajandream M. A., Sucgang R., Berriman M., Song J., Olsen R., Szafranski K., Xu Q., Tunggal B., Kummerfeld S., Madera M., Konfortov B. A., Rivero F., Bankier A. T., Lehmann R., Hamlin N., Davies R., Gaudet P., Fey P., Pilcher K., Chen G., Saunders D., Sodergren E., Davis P., Kerhornou A., Nie X., Hall N., Anjard C., Hemphill L., Bason N., Farbrother P., Desany B., Just E., Morio T., Rost R., Churcher C., Cooper J., Haydock S., van Driessche N., Cronin A., Goodhead I., Muzny D., Mourier T., Pain A., Lu M., Harper D., Lindsay R., Hauser H., James K., Quiles M., Madan Babu M., Saito T., Buchrieser C., Wardroper A., Felder M., Thangavelu M., Johnson D., Knights A., Loulseged H., Mungall K., Oliver K., Price C., Quail M. A., Urushihara H., Hernandez J., Rabbinowitsch E., Steffen D., Sanders M., Ma J., Kohara Y., Sharp S., Simmonds M., Spiegler S., Tivey A., Sugano S., White B., Walker D., Woodward J., Winckler T., Tanaka Y., Shaulsky G., Schleicher M., Weinstock G., Rosenthal A., Cox E. C., Chisholm R. L., Gibbs R., Loomis W. F., Platzer M., Kay R. R., Williams J., Dear P. H., Noegel A. A., Barrell B., Kuspa A. (2005) Nature 435, 43–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weeks G., Gaudet P., Insall R. H. (2005) in Dictyostelium genomics (Loomis W. F., Kuspa A. eds.), pp. 211–234, Horizon Bioscience, Norfolk, UK [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chubb J. R., Insall R. H. (2001) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1525, 262–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim C. J., Spiegelman G. B., Weeks G. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 4490–4499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuxworth R. I., Cheetham J. L., Machesky L. M., Spiegelmann G. B., Weeks G., Insall R. H. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 138, 605–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kae H., Lim C. J., Spiegelman G. B., Weeks G. (2004) EMBO Rep. 5, 602–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolourani P., Spiegelman G. B., Weeks G. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 4543–4550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolourani P., Spiegelman G. B., Weeks G. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 10232–10240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alibaud L., Cosson P., Benghezal M. (2003) BioTechniques 35, 78–80, 82–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Haastert P. J. M. (1984) J. Gen. Microbiol. 130, 2559–2564 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Ed., pp. 18.47–18.55, Cold Spring Harbor, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khosla M., Robbins S. M., Spiegelman G. B., Weeks G. (1990) Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 918–922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robbins S. M., Williams J. G., Jermyn K. A., Spiegelman G. B., Weeks G. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 938–942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thiery R., Robbins S., Khosla M., Spiegelman G. B., Weeks G. (1992) Biochem. Cell Biol. 70, 1193–1199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biou V., Cherfils J. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 6833–6840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee S., Comer F. I., Sasaki A., McLeod I. X., Duong Y., Okumura K., Yates J. R., 3rd, Parent C. A., Firtel R. A. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 4572–4583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee S., Parent C. A., Insall R., Firtel R. A. (1999) Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 2829–2845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White M. A., Nicolette C., Minden A., Polverino A., Van Aelst L., Karin M., Wigler M. H. (1995) Cell 80, 533–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joneson T., White M. A., Wigler M. H., Bar-Sagi D. (1996) Science 271, 810–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez-Viciana P., Warne P. H., Khwaja A., Marte B. M., Pappin D., Das P., Waterfield M. D., Ridley A., Downward J. (1997) Cell 89, 457–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White M. A., Vale T., Camonis J. H., Schaefer E., Wigler M. H. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 16439–16442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall M. S., Davis L. J., Keys R. D., Mosser S. D., Hill W. S., Scolnick E. M., Gibbs J. B. (1991) Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 3997–4004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karnoub A. E., Weinberg R. A. (2008) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 517–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hancock J. F. (2003) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 373–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.