Abstract

Thrombin is a potent modulator of endothelial function and, through stimulation of NF-κB, induces endothelial expression of intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1). These cell surface adhesion molecules recruit inflammatory cells to the vessel wall and thereby participate in the development of atherosclerosis, which is increasingly recognized as an inflammatory condition. The principal receptor for thrombin on endothelial cells is protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR-1), a member of the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily. Although it is known that PAR-1 signaling to NF-κB depends on initial PKC activation, the subsequent steps leading to stimulation of the canonical NF-κB machinery have remained unclear. Here, we demonstrate that a complex of proteins containing CARMA3, Bcl10, and MALT1 links PAR-1 activation to stimulation of the IκB kinase complex. IκB kinase in turn phosphorylates IκB, leading to its degradation and the release of active NF-κB. Further, we find that although this CARMA3·Bcl10·MALT1 signalosome shares features with a CARMA1-containing signalosome found in lymphocytes, there are significant differences in how the signalosomes communicate with their cognate receptors. Specifically, whereas the CARMA1-containing lymphocyte complex relies on 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 for assembly and activation, the CARMA3-containing endothelial signalosome functions completely independent of 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 and instead relies on β-arrestin 2 for assembly. Finally, we show that thrombin-dependent adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells requires an intact endothelial CARMA3·Bcl10·MALT1 signalosome, underscoring the importance of the signalosome in mediating one of the most significant pro-atherogenic effects of thrombin.

Keywords: Endothelium, G Protein-coupled Receptors (GPCR), Inflammation, NF-kappa B, Phosphatidylinositol-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1), Thrombin, Protease-activated Receptor (PAR), VCAM-1

Introduction

Thrombin is a serine protease produced during intravascular coagulation, typically as a consequence of vascular injury (1). Although thrombin plays a central role in furthering the coagulation cascade by cleaving fibrinogen to produce fibrin, it also possesses the ability to act like a traditional hormone and elicit responses in a variety of cell types, including circulating platelets and endothelial cells (1). These cellular responses are mediated by a small family of GPCRs3 that are activated by thrombin through an unusual mechanism. Specifically, thrombin-dependent cleavage removes the N-terminal sequence of a target receptor, unmasking a cryptic peptide ligand that is present within the extracellular domain of the receptor itself. This tethered ligand is then able to interact with the ligand-binding pocket of the receptor to stimulate intracellular signaling (1). As a result, the receptors that are activated in this manner have been termed protease-activated receptors, or PARs. Currently, four members of the family have been identified, PAR-1 through PAR-4, although not all are directly acted upon by thrombin and instead represent targets of other proteases such as trypsin (2–5).

Because thrombin is short-lived in the circulation, most of its effects are exerted locally, near its site of generation. Consequently, endothelial cells adjacent to a site of tissue injury and coagulation represent a particularly important target of thrombin action. The predominant receptor for thrombin on endothelial cells appears to be PAR-1 (6), and although many specific endothelial responses follow stimulation of PAR-1, most can be characterized as contributing to “endothelial dysfunction” (7, 8). This is defined as a breakdown in the ability of the endothelium to maintain appropriate vascular tone, permeability, metabolism, and production of biologically active substances (9). Central to the phenomenon of endothelial dysfunction is the expression of adhesion molecules for recruitment of inflammatory cells and the production of pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines. All of these effects are key to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, in which early vascular injury caused by cholesterol deposition leads to thrombin-induced inflammation and propagation of vessel damage.

Activation of the NF-κB transcription factor represents one of the foremost mechanisms responsible for thrombin-induced endothelial dysfunction. As for many activators of NF-κB, this occurs through the so-called canonical pathway, whereby activation depends upon stimulation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex (10–19). IKK in turn directs the phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of IκB, a protein that sequesters NF-κB (particularly in the form of RelA/p65) in the cytoplasm (20, 21). Upon IκB degradation, NF-κB is then free to translocate to the nucleus and stimulate transcription of various pro-inflammatory genes.

Although considerable work has been carried out to demonstrate that thrombin induction of the canonical NF-κB pathway in endothelial cells requires prior stimulation of PKCδ (2, 18, 22–24), the molecular links between PKC and the IKK complex have remained unclear. Recently, we and others demonstrated that a signaling complex composed of a scaffolding protein (CARMA3), a linker protein (Bcl10), and an effector protein (MALT1) mediates IKK complex activation and subsequent NF-κB stimulation downstream of a small number of GPCRs (25–33). Much of our understanding of the complex, now referred to as the CBM signalosome, comes from earlier work in lymphocytes where an analogous signalosome containing the related CARMA1 protein mediates NF-κB activation downstream of the antigen receptor (34–37). In the case of lymphocytes, antigen stimulation leads to activation of PKC, which in turn phosphorylates CARMA1, causing a conformational change that exposes the CARMA1 caspase recruitment domain (CARD), a region responsible for binding Bcl10 (38, 39). MALT1 is then recruited, and the intact signalosome interacts with and stimulates the IKK complex.

Because thrombin-dependent NF-κB activation clearly requires PKC activation as an upstream event, we asked whether the CBM signalosome might function as an integral component of the thrombin-responsive signaling machinery. Here we show that all three proteins, CARMA3, Bcl10, and MALT1, are essential for thrombin to effectively stimulate the canonical NF-κB pathway in endothelial cells. Importantly, we also show that disrupting the CBM signalosome in endothelial cells has important pathophysiologic consequences, because it effectively blocks the ability of thrombin to induce expression of the adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 and reduces the thrombin-dependent adhesion of monocytes to these endothelial cells. As such, the thrombin receptor now joins a small number of GPCRs that utilize the CBM signalosome to signal to NF-κB. Several of these GPCRs share the property of causing endothelial dysfunction and vascular inflammation in the context of atherosclerosis. As a result, the CBM signalosome can be seen as an increasingly attractive target for pharmaceutical intervention in our attempts to combat multiple common instigators of atherogenesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Polyclonal antibodies to p-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204; catalog number 9101), p-Akt (Ser-473, catalog number 9271; and Thr-308, catalog number 2965), Myc, and MALT1 (catalog number 2494) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Polyclonal antibodies to Bcl10 (sc-5611) and p65 (sc-372-G) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Monoclonal antibodies to PDK1 (sc-17765), HDAC1 (sc-81598), and GAPDH (sc-32233) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Monoclonal antibody to p-IκB (Ser-32/34; catalog number 9246) was from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibodies to tubulin (catalog number T5168) and FLAG (catalog number F3165) were from Sigma. TaqMan® gene expression primers for quantitative RT-PCR were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Gene expression assay identifiers for mouse GAPDH, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, CARMA3, and Bcl10 were Mm99999915, Mm00449197, Mm00516023, Mm00459941, and Mm01323721, respectively. Thrombin (catalog number T4393), TRAP-6 (catalog number T1573), and TNFα (catalog number T6674) were purchased from Sigma. EGF (catalog number E-3476) and insulin (catalog number 12585-014) were from Invitrogen. IL-1β was from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The inhibitors AG1478 (catalog number 658552), LY294002 (catalog number 440204), and wortmannin (catalog number 681676) were from EMD Chemicals (Gibbstown, NJ). Gene-specific siRNA oligonucleotides were obtained from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO), utilizing the ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool format. In the case of CARMA3, a second siRNA pool (Qiagen) was utilized.

Plasmids

The NF-κB-responsive luciferase reporter plasmid (pNF-κB-luciferase) was purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). Control Renilla plasmid (phRL-TK) was from Promega (Madison, WI). The PDK1-Myc and kinase-dead (KD) PDK1-Myc plasmids were gifts from C. Sutherland and D. Alessi (University of Dundee). All other expression plasmids encoding tagged versions of Bcl10, CARMA3, or CARMA1 have been described previously (40, 41).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared from cells using either the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) or with TRIzol (Invitrogen). Equivalent amounts of RNA (500–1000 ng) were used for cDNA synthesis with the Superscript first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen) using random primers. Quantitative PCR was performed using TaqMan® gene expression primers (Applied Biosystems) listed above, on an Applied Biosystems 7500 apparatus. Cycle thresholds (Ct) were determined and normalized with those for reactions performed with GAPDH-specific primers. Relative expression levels were determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method as described previously (42).

Cell Culture

SVEC4–10 mouse endothelial cells were obtained from ATCC and cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS. The generation of SVEC4–10 cells stably expressing an NF-κB-responsive luciferase reporter plasmid has been described previously (43). Briefly, the reporter plasmid (pNF-κB-luciferase; Stratagene) was transfected along with a pSV2neo helper plasmid from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA). The cells were then cultured in the presence of G418 at a concentration of 500 μg/ml. Approximately 3 weeks after transfection, G418-resistant clones were isolated and analyzed for luciferase activity to obtain an optimally responsive line. The resulting line was then maintained in medium containing 300 μg/ml G418.

Western Analysis

After lysing cells with radioimmune precipitation assay buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors, immunoblotting was performed as described (28). When analyzing transient induction of phosphorylated proteins (pIκBα, p-Akt, and p-ERK), the cells were starved overnight in serum-free medium and then treated for the indicated periods of time with either 0.1 unit/ml thrombin, 100 μm TRAP-6, 0.4 ng/ml IL-1β, 0.1 μg/ml EGF, 50 nm insulin, or 10 ng/ml TNFα in serum-free DMEM before harvesting for Western analysis.

Immunoprecipitation

HEK293T cells were transfected with expression plasmids encoding tagged versions of Bcl10, CARMA3, CARMA1, or PDK1. The cells were harvested 24 h later and lysed in 0.2% Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer. Immunoprecipitations were carried out using monoclonal anti-FLAG (Sigma) as described (44). The products were then resolved by SDS-PAGE and detected by Western blotting with polyclonal anti-Myc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Samples of total lysate, prior to immunoprecipitation, were analyzed in parallel.

Nuclear Fractionation

Cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were prepared using the NE-PERTM nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Purity of the nuclear extracts was confirmed by Western blot for HDAC1.

Transfection and Luciferase Reporter Assay

For transient transfection experiments, the cells were transfected with pNF-κB-luciferase and the phRL-TK control Renilla plasmid (Promega) using FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied). 36 h later, the cells were treated for an additional 5 h with or without medium containing either 5 units/ml thrombin or 0.125 ng/ml IL-1β. In some cases, the cells were cotransfected with expression vectors encoding wild-type PDK1 or a dominant negative, kinase-dead version of PDK1 (PDK1 KD). The cells were harvested, and luciferase activity in lysates was measured with a dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) and LMax II384 luminometer (Molecular Devices), as described (28).

RNA Interference

Individual proteins were targeted with the use of siRNA pools from Dharmacon and Qiagen. In brief, the cells were transfected with gene-specific siRNA or nontargeting siRNA at a concentration of 10–25 nm using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were allowed to recover for 48–72 h to achieve maximal knockdown.

Monocyte/Endothelial Adhesion

SVEC4–10 cells were transfected with control or Bcl10-specific siRNAs and allowed to grow to confluence. After an overnight serum starvation, the cells were then treated with or without 4 units/ml thrombin for 6 h. WEHI-274.1 mouse monocytes (ATCC) were then added to the culture medium (6 × 105 cells/well for a 6-well plate). Monocytes were allowed to attach for 10 min, followed by vigorous washing, and the number of monocytes remaining attached to the endothelial monolayer were counted using an inverted bright field microscope. For each well, the total number of attached monocytes was tallied in seven random 20× fields.

Statistics

The data are expressed as the means ± S.E. Differences between groups were compared for significance using paired or unpaired two-tailed Student's t tests, as appropriate, with the assistance of GraphPad InStat software. p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Thrombin Activates the Canonical NF-κB Pathway in Mouse Endothelial Cells through PAR-1

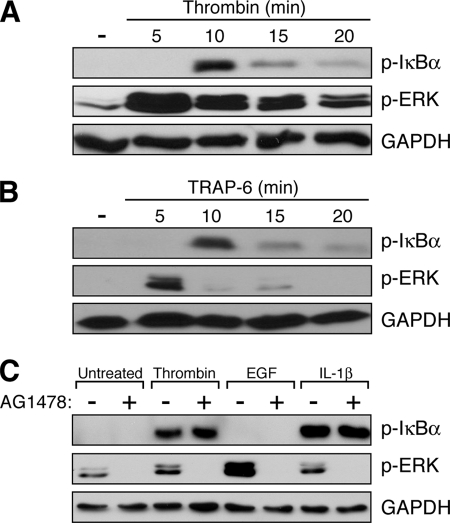

The immortalized mouse endothelial cell line, SVEC4–10, has proven to be a valuable model system for evaluating pro-inflammatory responses in the vasculature (45). However, little is known about the sensitivity of these cells to thrombin. Here, we found that thrombin causes rapid activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway in SVEC4–10 cells, as evidenced by the appearance of Ser-32/36 phosphorylated IκBα (p-IκB) in cell extracts within 10 min of treatment (Fig. 1A). Other thrombin-responsive signaling pathways are also activated, including that for ERK (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Canonical NF-κB activation through PAR-1 in SVEC4–10 endothelial cells. A, SVEC4–10 cells were treated with thrombin for varying periods of time before harvest and analysis by Western blot. Within 10 min, thrombin induces the phosphorylation of IκB, a marker of canonical NF-κB signaling. ERK activation, as evidenced by the appearance of p-ERK, occurs within 5 min. B, SVEC4–10 cells were similarly treated with a peptide that specifically activates PAR-1 (TRAP-6; SFLLRN). The time course for phosphorylation of IκB and ERK was identical to that observed with thrombin stimulation. C, SVEC4–10 cells were treated with the indicated agonists (thrombin, EGF, or IL-1β) in the presence or absence of 50 nm AG1478, an inhibitor of the EGFR tyrosine kinase. AG1478 was effective at completely eliminating both basal and induced levels of p-ERK, indicating that the EGFR is primarily responsible for ERK activation in these cells and that the inhibitor was fully active. In contrast, generation of p-IκB by thrombin was unaffected, suggesting that thrombin-dependent stimulation of the canonical NF-κB pathway is a direct effect of PAR-1 and not mediated through cross-activation of EGFR.

Of the various PAR family members, PAR-1 is the predominant member acting as a thrombin receptor in endothelial cells (6). To confirm that PAR-1 is functional in SVEC4–10 cells, we performed a similar time course with a PAR-1-specific peptide agonist (TRAP-6; SFLLRN). The results showed that TRAP-6 precisely mimics thrombin in its ability to induce the NF-κB and ERK pathways in SVEC4–10 cells, suggesting that PAR-1 likely mediates the thrombin response in these cells (Fig. 1B).

Most of the signaling cascades activated by PAR-1 are mediated through direct receptor-dependent stimulation of G proteins and their downstream signaling factors. However, PAR-1 is also known to transactivate the EGF receptor (EGFR), thereby stimulating additional signaling cascades (5, 46). To test whether the NF-κB activation observed following thrombin treatment might be secondary to EGFR transactivation, we co-treated cells with AG1478, an EGFR tyrosine kinase antagonist. Although AG1478 completely blocked ERK activation by thrombin, suggesting that stimulation of the ERK pathway in SVEC4–10 cells does indeed occur through EGFR transactivation, there was no effect on generation of p-IκB (Fig. 1C). Taken together, the results shown in Fig. 1 indicate that SVEC4–10 endothelial cells display a robust canonical NF-κB response to thrombin, an effect that is likely mediated through direct downstream signaling from PAR-1.

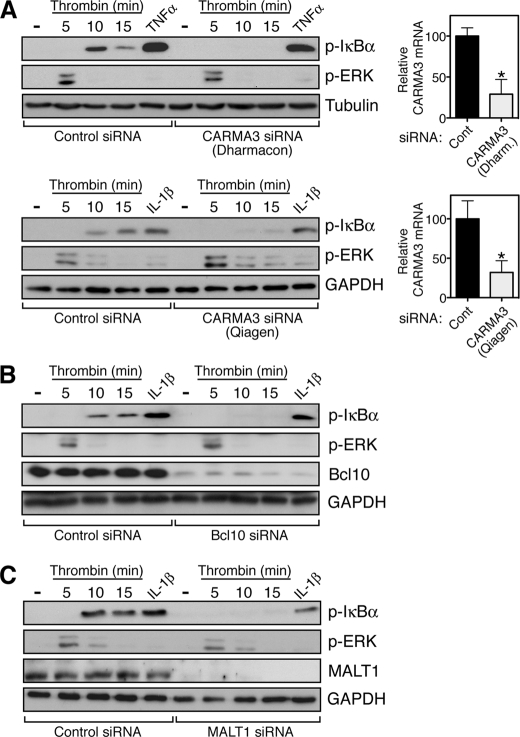

The CBM Signalosome Mediates Thrombin-dependent NF-κB Activation

We next employed an RNA interference approach to determine whether thrombin-mediated induction of p-IκB occurs through the CBM signalosome. Because of the lack of a sensitive and specific antibody for CARMA3, we used quantitative RT-PCR to demonstrate that siRNA targeting CARMA3 reduces mRNA levels for the protein by ∼70% (Fig. 2A, upper right panel). Concomitant with this reduction in CARMA3, we observed a complete blockade in the ability of thrombin to induce p-IκB (Fig. 2A, upper left panel). Conversely, the ability of TNFα to stimulate p-IκB production remained intact, indicating specificity for the role of CARMA3 in the thrombin response. Further, the reduction in CARMA3 levels did not impair other signaling responses induced by thrombin, such as that for ERK activation, again indicating specificity for the role of CARMA3 in a select pathway (Fig. 2A, upper left panel).

FIGURE 2.

The CBM signalosome mediates thrombin-dependent NF-κB activation in endothelial cells. A, SVEC4–10 cells were transfected with independent siRNA pools targeting CARMA3, designed by Dharmacon (upper panel) or Qiagen (lower panel), at a concentration of 20 and 10 nm, respectively. 48 h following transfection, the cells were treated with thrombin for the indicated periods of time or for 5 min with TNFα or IL-1β. The cells were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. CARMA3 knockdown completely abrogated p-IκB generation following thrombin treatment but had no effect on the response to either TNFα or IL-1β. In addition, the impact of CARMA3 on thrombin signaling was specific to the canonical NF-κB pathway, because CARMA3 knockdown had no effect on the ability of thrombin to induce p-ERK. CARMA3 mRNA knockdown was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR, shown at right. *, p < 0.05. Cont, control. B, SVEC4–10 cells were similarly transfected with an siRNA pool targeting Bcl10 (10 nm), resulting in nearly complete reduction of Bcl10 protein levels as determined by Western blotting. As with CARMA3 knockdown, the reduction in Bcl10 levels completely blocked thrombin-dependent p-IκB generation while not affecting the response to IL-1β and while not impacting the ability of thrombin to induce p-ERK. C, SVEC4–10 cells were similarly transfected with an siRNA pool targeting MALT1 (10 nm), resulting in complete reduction of MALT1 levels as determined by Western blotting. As seen in A and B, thrombin-dependent p-IκB generation was specifically blocked under these conditions.

As a further confirmation of the essential role for CARMA3 in the thrombin-mediated induction of p-IκB, we utilized an entirely different siRNA pool, prepared by a different manufacturer (Qiagen versus Dharmacon). This siRNA was nearly identical in its ability to reduce CARMA3 mRNA levels (Fig. 2A, lower right panel) and was also completely effective in blocking the thrombin induction of p-IκB (Fig. 2A, lower left panel). Again, the siRNA had no impact on p-IκB generation in response to an unrelated stimulus (IL-1β) and had no effect on thrombin-mediated ERK activation.

We next tested the role of the other components of the CBM signalosome and observed similar results. Knockdown of either Bcl10 or MALT1 completely blocked thrombin induction of p-IκB while not affecting the IL-1β response nor the ability of thrombin to activate ERK (Fig. 2, B and C). In both cases, Western analysis showed nearly complete reduction in the levels of the Bcl10 and MALT1 proteins, respectively, following siRNA transfection.

3-Phosphoinositide-dependent Protein Kinase 1 (PDK1) Is Not Needed to Bridge PAR-1 to the CBM Signalosome

Others have demonstrated a critical role for PI3K in mediating thrombin-induction of NF-κB-responsive genes (2, 22–24). Because PI3K activation causes rapid production of plasma membrane-associated phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate and subsequent recruitment of PDK1 through a phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate pleckstrin homology domain interaction (47), we considered the possibility that the thrombin receptor, PAR-1, might communicate with the CBM signalosome through PDK1. As such, this would be analogous to the mechanism by which a CARMA1-containing CBM signalosome is recruited and activated in T lymphocytes, following ligand activation of the antigen receptor complex, CD3/CD28 (48–50). In the case of T-lymphocytes, PDK1 serves as a scaffold by directly binding both CARMA1 and PKC. This allows PKC to phosphorylate CARMA1, resulting in exposure of the CARMA1 CARD, which subsequently binds Bcl10/MALT1. Thus, PDK1 is thought to function as a central “nidus” for assembly of the activated CBM signalosome in the vicinity of the antigen receptor.

To begin exploring the possible involvement of PDK1 in thrombin-dependent recruitment of the CARMA3-containing CBM signalosome, we used an immunoprecipitation approach to test whether CARMA3, like the lymphocyte-specific CARMA1, interacts with PDK1. The results showed that Myc-tagged PDK1 co-immunoprecipitates with FLAG-tagged CARMA3, suggesting that an interaction can occur between the two proteins (supplemental Fig. S1A). Importantly, when we compared the ability of CARMA3 and CARMA1 to bind to PDK1, we found that the two CARMA proteins are reasonably similar in their apparent affinity for PDK1 (supplemental Fig. 1B).

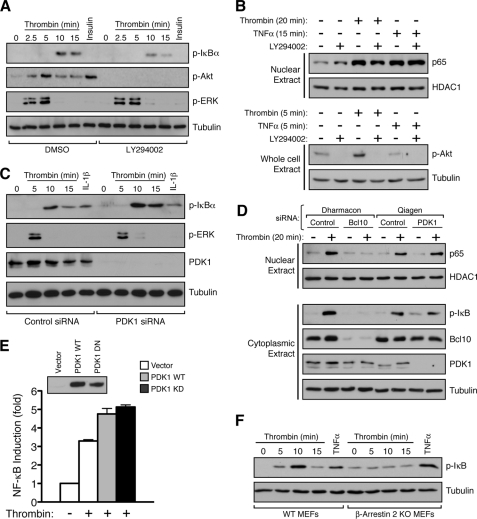

Because recruitment of PDK1 to the membrane is dependent on PI3K activation and generation of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate, we asked whether chemical inhibition of PI3K would be sufficient to block thrombin-induced generation of p-IκB, thereby suggesting impaired assembly of the CBM signalosome. Surprisingly, the well known PI3K inhibitor LY294002 had only a minimal effect on thrombin-induced p-IκB generation in SVEC4–10 cells (Fig. 3A). In contrast, LY294002 was completely effective at blocking thrombin- or insulin-induced phosphorylation of Akt, a known downstream substrate for the PI3K pathway, thereby demonstrating that the inhibitor was fully effective in eliminating PI3K activity in this context (Fig. 3A). Similar results were seen with wortmannin, an inhibitor that blocks PI3K activity through a mechanism different from that used by LY294002 (supplemental Fig. S2). We also found that LY294002 had a minimal effect on the ability of thrombin to induce nuclear translocation of the p65 subunit of NF-κB, an event that occurs as a consequence of IκB phosphorylation and degradation (Fig. 3B). Thus, two independent measures of thrombin-induced canonical NF-κB activation are largely unaffected by PI3K inhibition. These results sharply contrast with what has been shown in T-cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28; in this case, both LY294002 and wortmannin completely block antigen receptor-dependent signaling to IκB (49).

FIGURE 3.

PDK1 is dispensable for thrombin-dependent activation of canonical NF-κB. A, SVEC4–10 cells were pretreated for 1 h with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle or with 50 μm LY294002. The cells were then treated with thrombin for varying periods of time or with insulin for 5 min. The cells were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. The inhibitor had a minimal effect on thrombin induction of p-IκB while completely blocking phosphorylation of Akt (p-Akt473) in response to either thrombin or insulin. As expected, thrombin-induced ERK phosphorylation was not affected by LY294002, showing specificity for the effects of the inhibitor at the 50 μm dose. B, SVEC4–10 cells were similarly treated with DMSO or 50 μm LY294002 prior to thrombin stimulation for 20 min. The cells were then lysed, and the nuclear fraction was isolated and analyzed for p65 nuclear translocation by Western blotting (upper panel). As a loading control, nuclear fractions were also evaluated for the presence of the constitutive nuclear factor, HDAC1. Thrombin-dependent p65 nuclear translocation was largely unaffected by LY294002. As a control, TNFα treatment was also seen to induce nuclear accumulation of p65, an effect that was similarly unaltered by LY294002. In parallel wells, the cells were treated with or without thrombin, TNFα, and LY294002, as indicated, prior to preparing whole cell lysates and blotting for p-Akt308 (lower panel). As in A, this control demonstrates that the LY294002 compound was fully active at blocking PI3K activity within the context of the experiment. C, SVEC4–10 cells were transfected with an siRNA pool targeting PDK1 (25 nm; Qiagen), resulting in complete knockdown of PDK1 levels by 48 h. The cells were then treated with thrombin for the indicated periods of time or with IL-1β for 5 min. PDK1 knockdown had no detrimental effect on the ability of thrombin to stimulate p-IκB production. D, SVEC4–10 cells were transfected with siRNA pools, as indicated and treated with thrombin for 20 min before harvesting. The nuclear fractions were isolated and probed for p65, whereas separate cytoplasmic fractions were probed to assess knockdown efficiency for either Bcl10 or PDK1. Although Bcl10 knockdown completely abro-gated thrombin-induced p65 nuclear translocation, PDK1 knockdown had no effect. E, SVEC4–10 cells were transfected with NF-κB-luciferase and control Renilla reporter plasmids, in the presence or absence of co-transfected WT and kinase-dead, dominant negative (KD) PDK1 expression vectors as indicated. The cells were then treated for 5 h with or without thrombin. The cells were harvested, and the resulting NF-κB induction was measured by calculating the luciferase/Renilla ratio. The kinase-dead, PDK1 dominant negative mutant was unable to block thrombin-induced NF-κB activation under these conditions. The results are expressed as fold NF-κB induction ± S.E. and are representative of three experiments. Expression of the PDK1 proteins was evaluated by Western blotting (inset), using the same extracts as used for the luciferase assay. F, wild-type and β-arrestin 2 knock-out MEFs were treated with thrombin for the indicated periods of time or with TNFα for 5 min. The cells were harvested and analyzed for IκB phosphorylation. The results demonstrated that wild-type MEFs respond to both thrombin and TNFα with p-IκB generation, but β-arrestin 2 knock-out (KO) MEFs are completely unresponsive to thrombin while maintaining their responsiveness to TNFα.

As a more direct assessment of the functional role of PDK1 in the thrombin response, we then tested the effect of siRNA-mediated PDK1 knockdown in SVEC4–10 cells. Results showed that although PDK1 levels were almost completely ablated by the siRNA, the thrombin response, as measured by p-IκB generation, remained intact or was even slightly enhanced (Fig. 3C). Similarly, PDK1 knockdown had no effect on thrombin-induced p65 nuclear translocation, whereas in contrast, Bcl10 knockdown completely prevented the accumulation of p65 in the nucleus (Fig. 3D). Finally, when transiently expressed in SVEC4–10 cells, a kinase-dead, dominant negative mutant of PDK1 had no effect on thrombin-induced NF-κB activation, further supporting the notion that PDK1 has no significant role in mediating early steps in activation of the IKK complex or in the subsequent process of p65 nuclear translocation (Fig. 3E). These results again contrast with what has been shown for antigen receptor-dependent canonical NF-κB signaling in T-cells, which is entirely dependent upon the presence and activity of PDK1 (48, 49).

Recently, Sun and Lin (51) demonstrate that β-arrestin 2 can physically link the lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) receptor with CARMA3. Thus, in the context of GPCR signaling, β-arrestin 2 could represent an alternative to PDK1, with regard to assembly of the CARMA3-containing CBM signalosome. As a result, we measured thrombin-dependent p-IκB generation in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) obtained from wild-type mice as compared with MEFs obtained from β-arrestin 2 knock-out mice. Although the wild-type MEFs responded with a similar time course and magnitude of p-IκB induction as was seen with SVEC4–10 cells, the β-arrestin 2 knock-out MEFs were completely unresponsive to thrombin (Fig. 3F). In contrast, both MEF lines showed similar responsiveness to TNFα, indicating that β-arrestin 2 deficiency was not impacting the NF-κB pathway in a global manner.

In conclusion, despite the ability of PDK1 to physically interact with CARMA3 in co-immunoprecipitation experiments, our data suggest that PAR-1 does not require PDK1 for communication with the IKK complex. Instead, we find that PAR-1 depends upon β-arrestin 2 for NF-κB activation. Thus, PAR-1, and perhaps several other GPCRs, may utilize a mechanism that is quite distinct from that utilized by antigen receptors for assembly of the CBM signalosome.

The CBM Signalosome Is Critical for Thrombin Induction of NF-κB-responsive Gene Transcription in Endothelial Cells

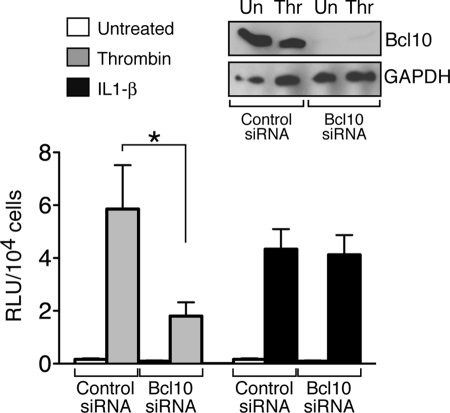

Having definitively shown a requirement for all of the components of the CBM signalosome in mediating an early step in the process of thrombin-induced canonical NF-κB activation, namely IκB phosphorylation, we next turned to an analysis of the role of the signalosome in mediating thrombin-dependent regulation of gene transcription. To this end, we evaluated SVEC4–10 cells with stable integration of an NF-κB-luciferase reporter and found that siRNA-mediated knockdown of Bcl10 resulted in profound impairment of thrombin-dependent luciferase expression (Fig. 4). Induction of luciferase in response to IL-1β, however, was unaffected.

FIGURE 4.

Bcl10 knockdown blocks thrombin-responsive NF-κB reporter activity. SVEC4–10 cells stably expressing the NF-κB-luciferase reporter were transfected with either a control siRNA pool or with an siRNA pool targeting Bcl10, as described in Fig. 2. After 48 h, the cells were treated for an additional 5 h with either thrombin or IL-1β. The cells were harvested, and NF-κB induction was assessed by measuring luciferase levels, corrected for cell number. The lysates were also analyzed for Bcl10 knockdown by Western blotting (inset). The results showed that Bcl10 knockdown dramatically reduced NF-κB activation by thrombin but had no effect on the activation achieved with IL-1β. The results represent the averages of three independent experiments ± S.E. *, p < 0.05. Un, untreated; Thr, thrombin.

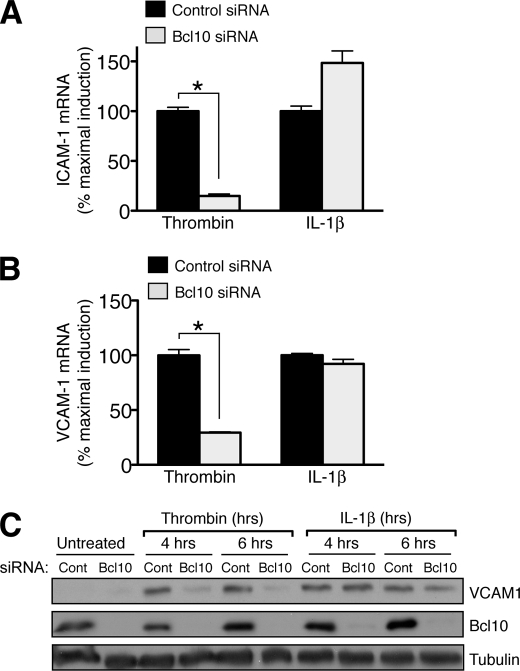

We then asked whether disrupting the CBM signalosome would affect the ability of thrombin to enhance transcription of endogenous genes, using the ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 genes as markers because they are known to be strongly induced by NF-κB (2). Preliminary studies showed that, as in other endothelial cell systems, thrombin induced these genes in a time-dependent fashion in SVEC4–10 cells, with mRNA levels increasing within 2 h following thrombin treatment and peak protein levels following shortly thereafter (not shown). We then used siRNA to block Bcl10 expression and found that this dramatically impaired the ability of thrombin to induce expression of both ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, as assessed by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 5, A and B). Because induction of VCAM-1 is particularly relevant to atherogenesis as a mechanism for promoting macrophage recruitment to the vessel wall, we also analyzed the impact of Bcl10 knockdown on VCAM-1 protein levels. Both thrombin and IL-1β caused a robust induction of VCAM-1 protein in SVEC4–10 cells within 4–6 h, but under conditions of Bcl10 knockdown, thrombin induction of VCAM-1 was almost completely blocked, whereas the induction by IL-1β remained unaffected (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the CBM signalosome is critical not only for proximal steps in canonical NF-κB activation but also for downstream regulation of NF-κB target genes.

FIGURE 5.

Bcl10 knockdown blocks thrombin-responsive induction of endothelial adhesion molecules. A and B, SVEC4–10 cells were transfected with control or Bcl10-specific siRNA as in Fig. 2. After 48 h, the cells were treated an additional 2 h with thrombin or IL-1β. The cells were harvested and assayed for ICAM-1 (A) or VCAM-1 (B) mRNA expression by quantitative RT-PCR. The results are expressed as the percentages of maximal induction and represent the means ± S.E. for three determinations. *, p < 0.05. C, similar to parts A and B above, SVEC4–10 cells were transfected with control (Cont) or Bcl10 siRNA and allowed to recover for 48 h. The cells were then treated with thrombin or IL-1β for the indicated periods of time before harvest and Western analysis.

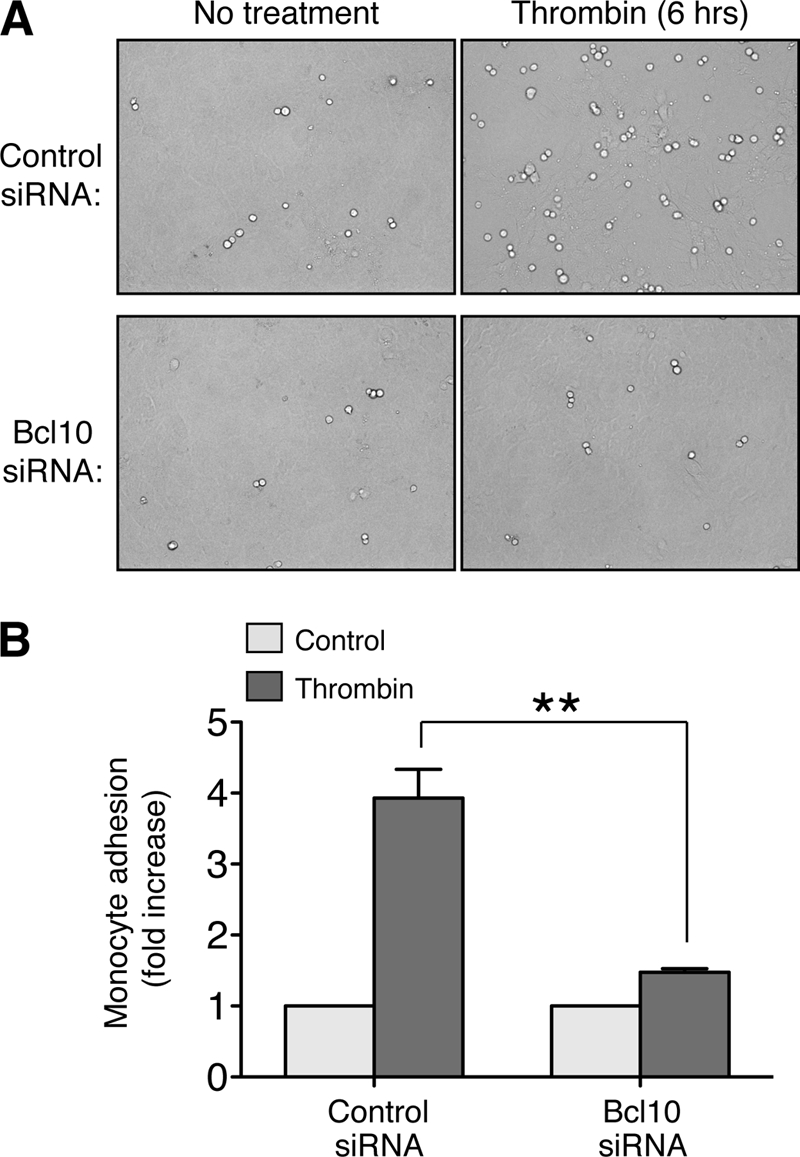

The CBM Signalosome Controls Thrombin-dependent Monocyte/Endothelial Adhesion

Recruitment of monocytes to the vessel wall is initiated largely through the interaction of VCAM-1, on the surface of endothelial cells, with very late antigen-4, an α4β1 integrin expressed on circulating monocytes (52). This interaction causes either rolling of monocytes on the endothelial surface or firm attachment when very late antigen-4 is in an activated conformation (53). Because we demonstrated that the CBM signalosome mediates thrombin-dependant NF-κB activation and VCAM-1 expression in endothelial cells, we utilized an in vitro adhesion assay to determine whether disruption of the endothelial CBM signalosome would interfere with thrombin-induced monocyte/endothelial attachment. To this end, we grew SVEC4–10 endothelial cells to confluency, treated with thrombin for 6 h, and then quantified the attachment of WEHI-274.1 mouse monocytes to the monolayer. Endothelial cells transfected with control siRNA showed a nearly 4-fold increase in monocyte attachment following thrombin treatment, whereas those transfected with Bcl10-specific siRNA showed only a 1.5-fold increase (Fig. 6, A and B). These findings illustrate, for the first time, an essential role for the CBM signalosome in mediating a critical biologic response to thrombin, one with important implications for endothelial pathophysiology.

FIGURE 6.

Thrombin-induced monocyte/endothelial adhesion is dependent on an intact endothelial CBM signalosome. A and B, SVEC4–10 cells were transfected with control or Bcl10 siRNA as above and were allowed to then grow to confluence, producing a monolayer. The cells were then treated with or without thrombin for 6 h to induce adhesion molecule expression. WEHI-274.1 monocytes were then added to the culture medium and allowed to settle onto the endothelial monolayer. After 10 min, unattached monocytes were removed by washing, and monocyte-endothelial attachment was measured by counting adherent monocytes in seven 20× fields per condition. Representative bright field micrographs of individual 20× fields are shown in A. Quantification of the fold increase in monocyte adherence is shown in B. The results represent the averages of nine independent determinations ± S.E. **, p < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Thrombin is now well recognized for exerting pro-inflammatory effects on the vasculature, particularly through its actions on endothelial cells. Whereas many of these effects are mediated by activation of the NF-κB transcription factor and downstream induction of NF-κB-responsive genes, the mechanisms linking thrombin receptors to the canonical NF-κB machinery are incompletely understood. In this study, we show that a signaling complex composed of the CARMA3, Bcl10, and MALT1 proteins (CBM signalosome) serves as a molecular bridge to link activated thrombin receptors to the IκB kinase. Further, we demonstrate that the CBM signalosome is essential for thrombin to activate transcription of key genes that underlie the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, particularly those that mediate recruitment of inflammatory cells to the vessel wall.

To date, a select group of GPCRs have now been shown to utilize the CBM signalosome for activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway. In addition to the thrombin receptor (PAR-1), these GPCRs include the receptors for angiotensin II, LPA, endothelin-1, platelet activating factor, IL-8 (CXCL8), and SDF-1 (CXCL12) (25–33). PAR-1 is unique among these GPCRs in that it is not activated by a circulating ligand. Rather, PAR-1 utilizes a tethered ligand that is present within the extracellular domain of the receptor itself but is masked by an N-terminal sequence that can be removed via proteolytic cleavage by thrombin (1). Once the N-terminal sequence is removed, the tethered ligand is free to interact with the ligand-binding pocket of the receptor and activate downstream signaling. Many other differences exist between these receptors, including their preferences for coupling to specific G protein families including Gαi, Gαq, and Gα12/13 (54, 55).

Despite their differences, GPCRs in this group do share some common properties. In particular, all are capable of activating PKC isoforms through Gαq (54, 55). We speculate that the PKC isoforms activated by these receptors phosphorylate CARMA3, thereby exposing the CARMA3 CARD and allowing for CARD-dependent recruitment of Bcl10 and MALT1. As such, this mechanism for assembly of the CBM signalosome would be analogous to that which occurs in B- and T-lymphocytes, following stimulation of antigen receptor (34–37).

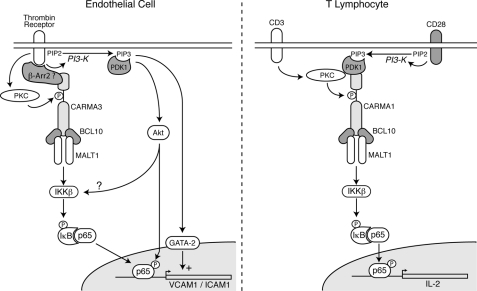

Clearly, however, many GPCRs are capable of activating PKC, but not all of these GPCRs are effective at stimulating NF-κB, and perhaps even fewer will be found to utilize the CBM signalosome. What are the distinguishing features that identify the group of GPCRs that effectively communicate with the CBM signalosome? The answer to this question is completely unknown but may lie in discovering additional signaling intermediates, besides PKC, that bridge selected GPCRs with the CBM signalosome. To gain further insight, we looked for clues by studying the well characterized activation of the analogous CARMA1-containing CBM signalosome in lymphocytes. In T-cells, strong evidence implicates PDK1 as a scaffolding protein that brings together activated PKC and CARMA1 following CD3/CD28 stimulation (48–50). In this case, stimulation of CD3 activates PKCθ, whereas stimulation of the CD28 co-receptor activates PI3K and induces PDK1 membrane recruitment (Fig. 7). PDK1 then binds to both PKC and CARMA1, facilitating the ability of PKC to recognize CARMA1 as a substrate and induce its phosphorylation.

FIGURE 7.

Schematic comparing CBM-dependent signaling in endothelial cells and lymphocytes. The schematic diagram illustrates potential differences between the mechanisms for recruitment and activation of the CARMA3-containing signalosome in endothelial cells (left panel) and the CARMA1-containing signalosome in T-cells (right panel). See text for further description.

Importantly, PAR-1 is known to activate PI3K in addition to PKC (1). Thus, we wondered whether this single receptor might be capable of activating two separate signal transduction pathways that converge on CARMA3, a feat that in the lymphocyte requires stimulation of two distinct receptors, CD3 and CD28 (Fig. 7). We therefore tested whether PI3K and PDK1 might be similarly important for the ability of PAR-1 to communicate with the CARMA3-containing CBM signalosome. As such, this could represent an additional level of control and potentially provide insight into the mechanisms governing the use of the CBM signalosome by only selected GPCRs.

However, despite evidence suggesting that a physical interaction can occur between PDK1 and CARMA3, we found that PDK1 knockdown by RNA interference had absolutely no impact on the thrombin-dependent NF-κB response, nor did expression of a PDK1 dominant negative mutant. PI3K inhibitors were also largely ineffective at blocking thrombin-induced p-IκB generation and p65 nuclear translocation. These results suggest that a significant difference exists between the mechanism utilized by PAR-1 for communication with the CARMA3-containing CBM signalosome and that utilized by CD3/CD28 for communication with the CARMA1-containing CBM signalosome.

It is intriguing to speculate that the difference may extend to multiple GPCRs, besides PAR-1. In fact, recent work by Sun and Lin (51) provides an alternative explanation as to how GPCRs may communicate with the CBM signalosome. These researchers demonstrated that MEFs from β-arrestin 2 knock-out mice were unable to respond to LPA with phosphorylation of IκB. In addition, β-arrestin 2 was found not only to bind CARMA3 but also to mediate an indirect physical interaction between the LPA receptor and CARMA3. Thus, β-arrestin 2 is an essential mediator of LPA-induced NF-κB activation. We similarly found that thrombin induction of p-IκB is completely impaired in β-arrestin 2 knock-out MEFs, whereas wild-type MEFs maintain a robust response. The arrestins are a small family of proteins known for their complex roles in GPCR signaling, and although some family members function only in the retina, two others, β-arrestin 1 and 2, are expressed ubiquitously and impact GPCR-dependent signaling more broadly (56, 57). In some cases, the arrestins work to terminate GPCR signaling activity, but in other cases they function as critical positive mediators of signaling. Because of this complex, nuanced role in regulating GPCR activity, one might imagine that specific arrestins could dictate which GPCRs communicate with the CBM signalosome, possibly in a cell type-specific manner. Based on our work and that of Sun and Lin, we suggest that in certain nonhematopoietic cells, such as endothelial cells, β-arrestin 2 replaces PDK1 as a scaffold for assembly of CARMA3-containing CBM signalosomes, in response to ligation of specific GPCRs that include PAR-1 and the LPA receptor (Fig. 7).

It is important to place our current work into the context of what is already known regarding thrombin induction of both ICAM-1 and VCAM-1. As noted earlier, NF-κB activation is a cornerstone in the regulation of these two genes, but other signal transduction events are also required to achieve optimal induction, some of which are specific to one gene or the other. Most relevant to our work is the fact that thrombin-induced PI3K activation is clearly crucial for the ultimate induction of both genes (2, 22–24), even though our studies indicate that PI3K activity is not particularly important for the proximal steps in the canonical NF-κB activation pathway, at least not for those leading to phosphorylation of IκB and p65 nuclear translocation.

It is therefore likely that the crucial role of PI3K lies in its stimulation of parallel pathways regulating ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 transcription. For example, it is clear that VCAM-1 induction depends not only on NF-κB activation but also on simultaneous activation of the GATA-2 transcription factor, which is PI3K-dependent (Fig. 7) (2, 24, 58). Others have shown that Akt activation, following thrombin-induced PI3K stimulation, is important for induction of ICAM-1 gene expression (23). However, it remains uncertain as to precisely how Akt contributes. Although evidence exists that Akt can directly phosphorylate components of the IκB kinase complex, contributing to its activation, this action of Akt appears to mostly impact IKKα and the noncanonical NF-κB pathway (59–62). Thus, in the setting of thrombin stimulation, Akt-responsive IKKα activation may not be sufficient for robust stimulation of the canonical pathway, leading to IκB phosphorylation, without the contributions of the CBM signalosome. Another explanation for the role of Akt stems from the observation that Akt can phosphorylate the p65 subunit of NF-κB, an event that increases its transcriptional capacity (Fig. 7) (63–65). Finally, PI3K activation can lead to stimulation of NADPH oxidase and generation of reactive oxygen species (66). Because NF-κB is a redox-sensitive transcription factor (67), this is yet another mechanism whereby PI3K may play a critical role in the downstream regulation of NF-κB-responsive gene transcription, without playing a dramatic role in CBM signalosome-dependent IκB phosphorylation and p65 nuclear translocation.

In summary, we show here that the CBM signalosome plays a critical role in mediating an important pathophysiologic response to thrombin, namely the induction of adhesion molecules on the surface of endothelial cells exposed to thrombin. This is an important event in a variety of conditions because adhesion molecules mediate the recruitment of inflammatory cells to sites of injury. In the case of atherogenesis, injury may be initiated by the chronic deposition of cholesterol in the vessel wall, with subsequent plaque rupture and thrombus formation. Thrombin generated locally in response to this injury stimulates recruitment of a variety of leukocytes through induction of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, which may further exacerbate the problem. However, similar cycles of injury and thrombosis may occur at sites of trauma and/or infection, where thrombin induction of adhesion molecules is beneficial and necessary for the wound-healing response. Although further work will be required to understand how PAR-1 communicates with the CBM signalosome, there now exists potential for targeting the signalosome in treatment of vascular conditions, such as atherosclerosis, where thrombin-induced NF-κB activation plays a pathologic role. This goal is potentially within grasp because an inhibitor of the MALT1 protease, the enzymatically active component of the signalosome, has now been described (68). Thus, the CBM signalosome is “drugable” and therefore represents an attractive target for pharmaceutical development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Christin Carter-Su, Mark Day, Ormond MacDougald, and Gabriel Nunez for advice. We thank Valerie Delekta for support and for review of the text. We thank Drs. Calum Sutherland and Dario Alessi for the gift of PDK1 expression plasmids. We thank Dr. Robert Lefkowitz for the gift of β-arrestin 2 knock-out MEFs and the corresponding wild-type MEF controls.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01-HL082914 and R01-DK079973 (to P. C. L.). This work was also supported by Shirley K. Schlafer Foundation (to L. M. M.-L.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- ICAM-1

- intracellular adhesion molecule-1

- VCAM-1

- vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

- PAR

- protease activated receptor

- CARMA

- CARD-containing MAGUK protein

- MALT

- mucosa associated lymphoid tissue

- CBM

- CARMA-Bcl10-MALT1

- IKK

- IκB kinase

- PDK1

- phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1

- CARD

- caspase recruitment domain

- EGFR

- EGF receptor

- LPA

- lysophosphatidic acid

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coughlin S. R. (2000) Nature 407, 258–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minami T., Sugiyama A., Wu S. Q., Abid R., Kodama T., Aird W. C. (2004) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 41–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Major C. D., Santulli R. J., Derian C. K., Andrade-Gordon P. (2003) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23, 931–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirano K. (2007) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27, 27–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martorell L., Martínez-González J., Rodríguez C., Gentile M., Calvayrac O., Badimon L. (2008) Thromb. Haemost. 99, 305–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Brien P. J., Prevost N., Molino M., Hollinger M. K., Woolkalis M. J., Woulfe D. S., Brass L. F. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 13502–13509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Croce K., Libby P. (2007) Curr. Opin Hematol. 14, 55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borissoff J. I., Spronk H. M., Heeneman S., ten Cate H. (2009) Cardiovasc. Res. 82, 392–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Brocq M., Leslie S. J., Milliken P., Megson I. L. (2008) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 10, 1631–1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fazal F., Bijli K. M., Minhajuddin M., Rein T., Finkelstein J. N., Rahman A. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 21047–21056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fazal F., Minhajuddin M., Bijli K. M., McGrath J. L., Rahman A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 3940–3950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bijli K. M., Minhajuddin M., Fazal F., O'Reilly M. A., Platanias L. C., Rahman A. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 292, L396–L404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minhajuddin M., Fazal F., Bijli K. M., Amin M. R., Rahman A. (2005) J. Immunol. 174, 5823–5829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tantivejkul K., Loberg R. D., Mawocha S. C., Day L. L., John L. S., Pienta B. A., Rubin M. A., Pienta K. J. (2005) J. Cell. Biochem. 96, 641–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miho N., Ishida T., Kuwaba N., Ishida M., Shimote-Abe K., Tabuchi K., Oshima T., Yoshizumi M., Chayama K. (2005) Yiovasc. Res. 68, 289–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anwar K. N., Fazal F., Malik A. B., Rahman A. (2004) J. Immunol. 173, 6965–6972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang K. W., Choi S. Y., Cho M. K., Lee C. H., Kim S. G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 17368–17378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahman A., Anwar K. N., Uddin S., Xu N., Ye R. D., Platanias L. C., Malik A. B. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 5554–5565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bijli K. M., Fazal F., Minhajuddin M., Rahman A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 14674–14684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghosh S., Hayden M. S. (2008) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 837–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vallabhapurapu S., Karin M. (2009) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 693–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rahman A., Fazal F. (2009) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 823–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahman A., True A. L., Anwar K. N., Ye R. D., Voyno-Yasenetskaya T. A., Malik A. B. (2002) Circ. Res. 91, 398–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minami T., Abid M. R., Zhang J., King G., Kodama T., Aird W. C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 6976–6984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grabiner B. C., Blonska M., Lin P. C., You Y., Wang D., Sun J., Darnay B. G., Dong C., Lin X. (2007) Genes Dev. 21, 984–996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klemm S., Zimmermann S., Peschel C., Mak T. W., Ruland J. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 134–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin D., Galisteo R., Gutkind J. S. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6038–6042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McAllister-Lucas L. M., Ruland J., Siu K., Jin X., Gu S., Kim D. S., Kuffa P., Kohrt D., Mak T. W., Nuñez G., Lucas P. C. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 139–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang D., You Y., Lin P. C., Xue L., Morris S. W., Zeng H., Wen R., Lin X. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 145–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahanivong C., Chen H. M., Yee S. W., Pan Z. K., Dong Z., Huang S. (2008) Oncogene 27, 1273–1280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Medoff B. D., Landry A. L., Wittbold K. A., Sandall B. P., Derby M. C., Cao Z., Adams J. C., Xavier R. J. (2009) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 40, 286–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rehman A. O., Wang C. Y. (2009) Int. J. Oral Sci. 1, 105–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borthakur A., Bhattacharyya S., Alrefai W. A., Tobacman J. K., Ramaswamy K., Dudeja P. K. (2010) Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 16, 593–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blonska M., Lin X. (2009) Immunol. Rev. 228, 199–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rawlings D. J., Sommer K., Moreno-García M. E. (2006) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6, 799–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thome M. (2004) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 348–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wegener E., Krappmann D. (2007) Sci. STKE 2007, pe21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsumoto R., Wang D., Blonska M., Li H., Kobayashi M., Pappu B., Chen Y., Wang D., Lin X. (2005) Immunity 23, 575–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sommer K., Guo B., Pomerantz J. L., Bandaranayake A. D., Moreno-García M. E., Ovechkina Y. L., Rawlings D. J. (2005) Immunity 23, 561–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lucas P. C., Yonezumi M., Inohara N., McAllister-Lucas L. M., Abazeed M. E., Chen F. F., Yamaoka S., Seto M., Nunez G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19012–19019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McAllister-Lucas L. M., Inohara N., Lucas P. C., Ruland J., Benito A., Li Q., Chen S., Chen F. F., Yamaoka S., Verma I. M., Mak T. W., Núñez G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 30589–30597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001) Methods 25, 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakano A., Hattori Y., Aoki C., Jojima T., Kasai K. (2009) Hypertens. Res. 32, 765–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inohara N., Koseki T., Lin J., del Peso L., Lucas P. C., Chen F. F., Ogura Y., Núñez G. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27823–27831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O'Connell K. A., Edidin M. (1990) J. Immunol. 144, 521–525 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kalmes A., Daum G., Clowes A. W. (2001) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 947, 42–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pearce L. R., Komander D., Alessi D. R. (2010) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 9–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee K. Y., D'Acquisto F., Hayden M. S., Shim J. H., Ghosh S. (2005) Science 308, 114–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park S. G., Schulze-Luehrman J., Hayden M. S., Hashimoto N., Ogawa W., Kasuga M., Ghosh S. (2009) Nat. Immunol. 10, 158–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Häcker H., Karin M. (2006) Sci. STKE 2006, re13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun J., Lin X. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 17085–17090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mestas J., Ley K. (2008) Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 18, 228–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alon R., Kassner P. D., Carr M. W., Finger E. B., Hemler M. E., Springer T. A. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 128, 1243–1253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ye R. D. (2001) J. Leukocyte Biol. 70, 839–848 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hendriks-Balk M. C., Peters S. L., Michel M. C., Alewijnse A. E. (2008) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 585, 278–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lefkowitz R. J., Shenoy S. K. (2005) Science 308, 512–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shenoy S. K., Lefkowitz R. J. (2003) Biochem. J. 375, 503–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Minami T., Aird W. C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 47632–47641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gustin J. A., Korgaonkar C. K., Pincheira R., Li Q., Donner D. B. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 16473–16481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ozes O. N., Mayo L. D., Gustin J. A., Pfeffer S. R., Pfeffer L. M., Donner D. B. (1999) Nature 401, 82–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cahill C. M., Rogers J. T. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 25900–25912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dan H. C., Cooper M. J., Cogswell P. C., Duncan J. A., Ting J. P., Baldwin A. S. (2008) Genes Dev. 22, 1490–1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Madrid L. V., Mayo M. W., Reuther J. Y., Baldwin A. S., Jr. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18934–18940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Madrid L. V., Wang C. Y., Guttridge D. C., Schottelius A. J., Baldwin A. S., Jr., Mayo M. W. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 1626–1638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sizemore N., Lerner N., Dombrowski N., Sakurai H., Stark G. R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 3863–3869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hawkins P. T., Davidson K., Stephens L. R. (2007) Biochem. Soc. Symp. 74, 59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pantano C., Reynaert N. L., van der Vliet A., Janssen-Heininger Y. M. (2006) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 8, 1791–1806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rebeaud F., Hailfinger S., Posevitz-Fejfar A., Tapernoux M., Moser R., Rueda D., Gaide O., Guzzardi M., Iancu E. M., Rufer N., Fasel N., Thome M. (2008) Nat. Immunol. 9, 272–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.