Abstract

5-Formyltetrahydrofolate (5-CHO-THF) is formed by a side reaction of serine hydroxymethyltransferase. Unlike other folates, it is not a one-carbon donor but a potent inhibitor of folate enzymes and must therefore be metabolized. Only 5-CHO-THF cycloligase (5-FCL) is generally considered to do this. However, comparative genomic analysis indicated (i) that certain prokaryotes lack 5-FCL, implying that they have an alternative 5-CHO-THF-metabolizing enzyme, and (ii) that the histidine breakdown enzyme glutamate formiminotransferase (FT) might moonlight in this role. A functional complementation assay for 5-CHO-THF metabolism was developed in Escherichia coli, based on deleting the gene encoding 5-FCL (ygfA). The deletion mutant accumulated 5-CHO-THF and, with glycine as sole nitrogen source, showed a growth defect; both phenotypes were complemented by bacterial or archaeal genes encoding FT. Furthermore, utilization of supplied 5-CHO-THF by Streptococcus pyogenes was shown to require expression of the native FT. Recombinant bacterial and archaeal FTs catalyzed formyl transfer from 5-CHO-THF to glutamate, with kcat values of 0.1–1.2 min−1 and Km values for 5-CHO-THF and glutamate of 0.4–5 μm and 0.03–1 mm, respectively. Although the formyltransferase activities of these proteins were far lower than their formiminotransferase activities, the Km values for both substrates relative to their intracellular levels in prokaryotes are consistent with significant in vivo flux through the formyltransferase reaction. Collectively, these data indicate that FTs functionally replace 5-FCL in certain prokaryotes.

Keywords: Archaebacteria, Bacteria, Folate Metabolism, Glutamate, Histidine, Comparative Genomics, Functional Complementation

Introduction

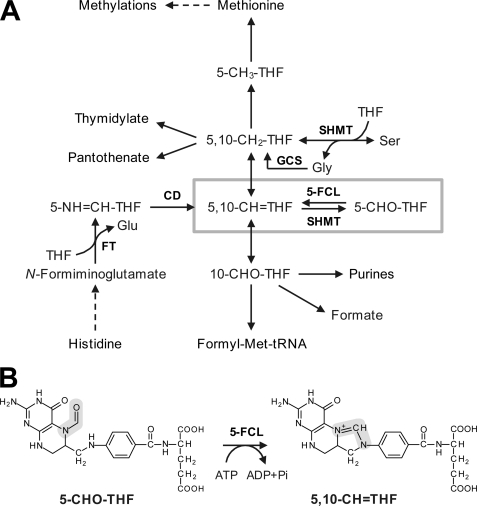

5-Formyltetrahydrofolate (5-CHO-THF)3 is exceptional among folates in two respects. First, it is not made by a dedicated enzyme. Rather, it is formed almost exclusively by a side reaction of serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT) in which 5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolate (5,10-CH=THF) is hydrolyzed to 5-CHO-THF in the presence of bound glycine (Fig. 1A) (1–3). Other possible enzymatic or chemical sources (4, 5) appear to be minor. Second, 5-CHO-THF is not an active donor of one carbon (C1) units but a potent inhibitor of various folate-dependent enzymes in the C1 metabolism network (6). 5-CHO-THF must consequently be removed. The only known removal mechanism for 5-CHO-THF is a salvage reaction in which it is reconverted to 5,10-CH=THF by the enzyme 5-CHO-THF cycloligase (5-FCL, EC 6.3.3.2) (6–9). This reaction requires MgATP and is essentially irreversible (Fig. 1B) (10). The 5-FCL reaction is medically significant because, by recycling 5-CHO-THF back to the active C1-folate pool, it allows use of 5-CHO-THF as an antifolate rescue agent in cancer chemotherapy (6).

FIGURE 1.

5-CHO-THF in the context of C1 metabolism. A, overview of the C1 folate reaction network. SHMT mediates the reversible conversion of THF and serine to 5,10-CH2-THF and glycine. This reaction is a major source of C1 units for use in other reactions. SHMT also mediates a side reaction that converts 5,10-CH=THF to 5-CHO-THF, which inhibits various folate-dependent enzymes and must therefore be metabolized. 5-FCL is the only enzyme known to do this. Dashed arrows depict multiple steps. Abbreviations: 5-CH3-THF, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate; 5,10-CH2-THF, 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate; 10-CHO-THF, 10-formyltetrahydrofolate; GCS, glycine cleavage system. B, the reaction catalyzed by 5-FCL. The C1 moiety is highlighted in gray.

The main reaction mediated by SHMT, the reversible conversion of serine to glycine and 5,10-methylene-THF, is a key source of C1 units and SHMT is an almost ubiquitous enzyme (11–13). The capacity to form 5-CHO-THF is thus also almost universal, and consequently so is the need for 5-CHO-THF removal. It might therefore be expected that all organisms would have 5-FCL, except those few that lack SHMT (14) or folates (15). However, in the course of a comparative genomic analysis of folate synthesis and metabolism involving hundreds of genomes (16) we were surprised to note that diverse prokaryotes had genes encoding SHMT (glyA) and other folate-dependent enzymes but no gene for 5-FCL (ygfA).

This lack of the ygfA gene appeared to signal a case of a missing enzyme, or pathway hole, i.e. where there is either a completely different enzyme (nonorthologous displacement) or an alternative pathway (16, 17). Here, we report an investigation of these possibilities using comparative genomics analysis. This analysis, together with literature mining, predicted that the histidine degradation enzyme glutamate formiminotransferase (FT, EC 2.1.2.5) could functionally replace 5-FCL in organisms that lack this enzyme. This prediction was experimentally verified by functional complementation of an Escherichia coli ygfA deletant, by antifolate rescue experiments with Streptococcus pyogenes, and by biochemical characterization of the formyltransferase activity of recombinant FT proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bioinformatics

Genomes were analyzed using the SEED data base and its tools (18). Archaea lacking folates were excluded from the analysis. Genes with anticorrelated distributions to that of ygfA were sought using the Phylogenetic Profiler tool at JGI and the Signature Genes tool at NMPDR. Sequences were aligned using ClustalW or Multalin. Phylogenetic analyses were made using MEGA4 (19).

Chemicals

(6S)-Tetrahydrofolic acid (THF), (6S)-5-formyltetrahydrofolic acid, calcium salt (5-CHO-THF), and (R,S)-5-formyltetrahydrofolate triglutamate were from Schircks Laboratories (Jona, Switzerland). Saturated stock solutions were prepared under N2, minimizing light exposure, by dissolving 2–10 mg of these folates in N2-sparged K-phosphate buffer (100 mm, pH 7.0) containing 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol. Concentrations of THF and 5-CHO-THF were determined spectrophotometrically using published extinction coefficients, ϵ298 nm = 28,000 m−1·cm−1 and ϵ287 nm = 31,500 m−1·cm−1, respectively (20). N-Formyl-l-glutamate was prepared as described (21) except that acetone was used in place of benzene to promote crystallization. The product was separated from glutamate by passage through a 15-ml column of AG-50 X8 (H+) (Bio-Rad) and washing with 15 ml of water. The eluate was neutralized with 1 m NH4OH and frozen. N-Formimino-l-glutamate (FIGLU) was synthesized and purified as described (22) except that FIGLU was separated from glutamate on a 25-ml column of AG-1 X8 (acetate) (Bio-Rad) that was eluted with a linear gradient of acetic acid (0–0.5 m) at a rate of 1 ml min−1, collecting 5-ml fractions. Fractions were analyzed by thin layer chromatography on 0.1 mm cellulose plates (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) developed with n-butanol:acetic acid:water, 60:15:25 (v/v/v). Detection was with ninhydrin; to detect FIGLU, plates were first exposed to NH3 vapor for 2 h. Fractions containing FIGLU were pooled and freeze-dried.

Strains and Media

E. coli Top10 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL strains (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) were used for plasmid amplification and protein overexpression, respectively. The ΔygfA deletion was made in E. coli K12 strain MG1655 (see below). All E. coli strains were grown at 37 °C with agitation in LB medium (23) or, for complementation tests, in M9 medium (23) containing 0.2% (w/v) glucose, micronutrients, and FeSO4 (24). S. pyogenes JRS4, a streptomycin-resistant derivative of serotype M6 strain D471 (25), was from I. Biswas (University of Kansas Medical Center). FT knockouts were made in this background (see below). S. pyogenes cultures were grown statically at 37 °C with 5% CO2 supply on TH-HS medium (Todd-Hewitt medium (Difco, Detroit, MI) supplemented with 5% (v/v) horse serum (Sigma-Aldrich) (26)) and on CDM chemically defined medium (27) from which p-aminobenzoic acid and folic acid were omitted. Antibiotic concentrations (μg ml−1) were: for E. coli, carbenicillin 100, chloramphenicol 34, erythromycin 500, kanamycin 50, streptomycin 50; for S. pyogenes, erythromycin 1.5, streptomycin 200.

Mutant Construction

Primers are listed in supplemental Table S1. The ygfA::Kan deletion from Keio collection strain JW2879 (28) was transferred to E. coli strain MG1655 by P1 transduction. Clones harboring the deletion were selected on LB containing kanamycin, and verified by sequencing. The S. pyogenes FT knock-out was obtained by single crossover recombination. A 421-bp fragment of the S. pyogenes FT gene was cloned in pSK-Erm, a pBluescript vector modified to confer erythromycin resistance (29). S. pyogenes JRS4 competent cells were obtained as described (26). Briefly, cells were grown in 20 ml of TH-HS medium containing streptomycin until A560 reached 0.3 and harvested by centrifugation at 4 °C (4500 × g, 5 min). The washed cell pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of ice-cold 0.5 m sucrose. Electroporation was performed by adding 2 μg of the Sp421bp-pSK-Erm construct to 40 μl of fresh competent cells; a Bio-Rad gene pulser was used (peak voltage 2.5 kV; capacitance 25 μF; pulse controller 200 Ω). Cells were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in 1 ml TH-HS, followed by plating on TH-HS containing erythromycin. Colonies appeared after 2 days. Mutants were screened by PCR using gene- and vector-specific primers (SpKOver-F and M13rev-R; SpKOver-R and M13fwd-F). The queT gene was used as a positive control (primers QueT-F and QueT-R). FT knock-out strains were electroporated as above with the S. pyogenes FT gene under the control of the strong P23 promoter (30, 31) in the shuttle vector pAT28 (32). pAT28 has the spc spectinomycin resistance gene and the pAMβ1 origin of replication, which confers high copy number in Gram+ bacteria (33). The FT gene was first subcloned into BamHI-SalI digested pOri23 (30). The P23-FT fragment was then excised with EcoRI-SalI and cloned into EcoRI-SalI-digested pAT28.

Expression Constructs for Functional Complementation and Protein Production

Genomic DNA of Acidobacteria bacterium Ellin345, Elusimicrobium minutum, Herpetosiphon aurantiacus, Syntrophus aciditrophicus, Picrophilus torridus, and Thermoplasma acidophilum were kindly provided by C. R. Kuske (Los Alamos National Laboratory), A. Brune (Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology), D. A. Bryant (Penn State University), M. J. McInerney (University of Oklahoma), W. Liebl (Technische Universität München), and W. Baumeister (Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry), respectively. Genomic DNA of S. pyogenes M1 was from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). FT sequences were amplified with PfuTurbo DNA Polymerase (Stratagene) using genomic DNA as template and primers (supplemental Table S1) designed with restriction sites to subclone the amplified product into pBluescript II SK (Stratagene) for complementation assays, or pET28b or pET21a (Novagen) for overexpression of proteins carrying a C-terminal His tag. Constructs were verified by sequencing.

Functional Complementation

E. coli ΔygfA cells harboring pACYC-RP and pSC101-RIL (Stratagene) encoding rare tRNAs were transformed with pBS II SK alone (negative control) or harboring E. coli ygfA (positive control) or a FT gene, plated on LB containing 1 mm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), kanamycin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, and carbenicillin, and incubated at 37 °C. The next day, independent clones were streaked on the M9 medium above or a modified version in which 50 mm glycine replaced 20 mm NH4Cl as nitrogen source. Plates were incubated for 4 days at 37 °C.

Production and Isolation of Recombinant Proteins

Porcine (Sus scrofa) glutamate formiminotransferase-cyclodeaminase (FT-CD) was produced as described (34) using an expression construct in pBke obtained from R. E. MacKenzie (McGill University). FTs from Acidobacteria bacterium Ellin345 (Ab), S. pyogenes (Sp), P. torridus (Pt), and T. acidophilum (Ta) were prepared as follows: BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL cells were transformed with AbFT-CD-pET21a, SpFT-pET28b, PtFT-pET28b, or TaFT-pET28b. Cultures were induced with 1 mm IPTG when A600 reached 0.7, then held for 3 h at room temperature. Cells were pelleted (6000 × g, 20 min, 4 °C), resuspended in 100 mm K-phosphate, pH 7.3, and disrupted by sonication (15 s × 12). The proteins were purified on 0.5-ml Ni2+-affinity columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) equilibrated with sonication buffer. Columns were washed with 100 mm K-phosphate, pH 7.3 containing 300 mm NaCl and 20 mm imidazole, eluted by raising the imidazole concentration to 250 mm, and desalted on PD-10 columns (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) equilibrated with 100 mm K-phosphate, pH 7.3 containing 10% (v/v) glycerol. The desalted samples were flash frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C; all proteins were stable in these conditions except Acidobacteria bacterium FT-CD, which lost 80% of activity after storage for 8 weeks. Protein concentration and purity were determined by the Bradford method (35) and SDS-PAGE, respectively.

Enzyme Assays

Formiminotransferase and reverse direction formyltransferase assays were slightly modified from those of Bortoluzzi and MacKenzie (36). Standard reactions (100 μl) contained 100 mm K-phosphate, pH 7.3, 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 0.5 mm THF, 5 mm FIGLU or N-formylglutamate (which were shown to be saturating concentrations), and 0.001–1 μg of enzyme. After incubation at 30 °C for 5–60 min, reactions were stopped by adding 100 μl of 0.36 m HCl followed by 55 s boiling, which converts 5-formimino-THF (5-NH=CH-THF) to 5,10-CH=THF. After cooling and centrifuging to clear (15,800 × g, 5 min), 5,10-CH=THF was estimated spectrophotometrically (ϵ350 = 24,900 m−1·cm−1) using a blank containing no FIGLU or N-formylglutamate. Standard forward-direction formyltransferase assays (100 μl) contained 100 mm K-phosphate, pH 7.3, 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mm 5-CHO-THF, 5 mm l-glutamate, and 0.1–1 μg of enzyme. After incubation at 30 °C for 5–30 min, reactions were stopped by adding 10 μl of 100 mm β-mercaptoethanol containing 20% (w/v) Na-ascorbate and boiling for 60 s, then cooled on ice and centrifuged as above. Folates were separated by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) on a 150 × 3.2 mm Prodigy 5 μm ODS(2) column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) with a 2.5–25% (v/v) acetonitrile gradient in 87 mm phosphoric acid, pH 2.3 (flow rate 1.5 ml min−1) and detected by fluorescence (excitation 295 nm, emission 356 nm) (37). THF and 5-CHO-THF standards were used to quantify substrate consumption and product formation. Km and kcat values were obtained by curve fitting to a rectangular hyperbola using SigmaPlot11 (SYSTAT Software, Chicago, IL).

Folate Analysis

E. coli wild-type or ΔygfA strains harboring pBS II SK alone or containing E. coli ygfA or S. pyogenes or S. aciditrophicus FT genes were grown at 37 °C in 120 ml of M9 medium containing 0.2% glucose, 1 mm IPTG, 7 mm glycine, and appropriate antibiotics. When A600 reached 1.0 ± 0.1, cells were pelleted, frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80 °C. Folates were then extracted as described (38). Briefly, pellets were resuspended in 10 ml of 50 mm HEPES-CHES, pH 7.8, containing 2% (w/v) Na-ascorbate and 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol, sonicated, boiled for 10 min, and centrifuged (13,000 × g, 10 min). The extraction step was repeated once. The combined extracts were treated for 2 h at 37 °C with rat plasma conjugase to deglutamylate folates. Samples were then boiled for 10 min, centrifuged as above, and filtered. Folates were isolated using 2-ml folate affinity columns, which were eluted with 5 ml of 87 mm phosphoric acid containing 1% (w/v) ascorbic acid (adjusted to pH 2.3 with KOH). Samples (400 μl) were analyzed by HPLC with electrochemical detection (39). Detector response was calibrated with standards from Merck Eprova (Schaffhausen, Switzerland). Tests with E. coli extracts spiked with 1.2 nmol of 5,10-CH=THF showed 4.9 ± 0.5% conversion to 5-CHO-THF; experimental values for endogenous 5-CHO-THF and 5,10-CH=THF were corrected accordingly.

RESULTS

A Candidate for 5-CHO-THF Removal Predicted by Comparative Genomics

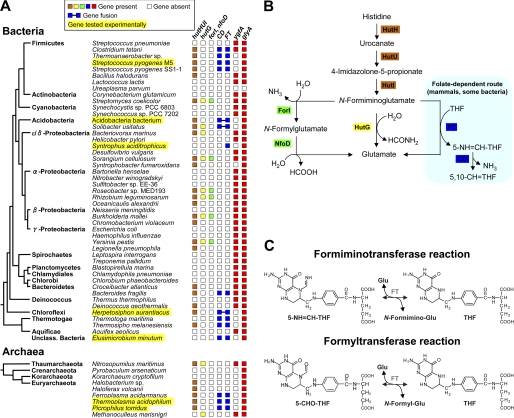

A systematic analysis of 621 bacterial and 19 archaeal genomes using the SEED data base (18) revealed that 618 have glyA genes encoding SHMT. Of these 618, 555 have ygfA genes specifying 5-FCL, and 63 (a significant minority) do not. The ygfA-deficient group includes taxonomically diverse bacteria and archaea (Fig. 2A). As some other gene is expected to replace ygfA when it is absent, we sought genes whose phylogenetic distribution is anticorrelated with that of ygfA. The gene encoding the histidine degradation enzyme FT emerged from this analysis as the strongest candidate. The FT gene is frequently present when ygfA is absent and almost always absent when ygfA is present (Fig. 2A); globally, FT occurs in 46% of the genomes without ygfA, but in only 2% of the genomes with it.

FIGURE 2.

Identification of FT as a potential candidate for 5-CHO-THF removal. A, distribution among representative prokaryotes of the FT gene, of other histidine degradation genes (hutHUI, hutG, forI, nfoD, CD), and of the genes involved in 5-CHO-THF formation (glyA) and removal (ygfA). The tree shows the standard branching order for each group and is adapted from (60), with the addition of archaea (61) for which chemical, biochemical, or genomic evidence supports the presence of folates (15, 16, 62, 63). Note the anticorrelated distributions of ygfA and FT. Organisms whose FTs were tested experimentally are highlighted in yellow. B, histidine degradation pathways. Folate-dependent reactions are highlighted in pale blue. C, reactions mediated by mammalian FT, i.e. formimino or formyl group transfer between glutamate and THF. Abbreviations: hutH, histidine ammonia-lyase; hutU, urocanate hydratase; hutI, imidazolone propionase; hutF, formiminoglutamate iminohydrolase; hutG, formiminoglutamase; nfoD, N-formylglutamate deformylase; forI, formiminoglutamate iminohydrolase.

Classical biochemical data on FT add to its plausibility as a substitute for 5-FCL. FT is a folate-dependent enzyme that mediates a late step in histidine degradation in mammals and certain bacteria; other bacteria use alternative, folate-independent routes (Fig. 2B) (18, 36). Specifically, FT catalyzes the transfer of a formimino group from FIGLU to THF, yielding 5-formimino-THF (5-NH=CH-THF), which is then converted to 5,10-CH=THF by the action of formiminotetrahydrofolate cyclodeaminase (CD) (Fig. 2C). In mammals and some bacteria, FT and CD are fused together in a single protein (Fig. 2A). Besides formimino transfer, mammalian FT is known to mediate an analogous formyl transfer between N-formylglutamate and THF, and to do so reversibly (Fig. 2C) (36, 40). The formyltransferase activity of mammalian FT is far lower than its formiminotransferase activity and has been viewed as physiologically insignificant (6, 36). Nevertheless, formyltransferase activity in the 5-CHO-THF → THF direction (henceforth termed the forward direction) would in principle enable 5-CHO-THF removal.

Further comparative genomic evidence of an alternative function for FT comes from its distribution pattern relative to those of other histidine degradation enzymes. Most prokaryotic genomes having FT also have CD and the other genes (hutHUI) needed for a complete histidine degradation pathway (Fig. 2A), and some (e.g. S. pyogenes) have these genes in an operonic arrangement (18). In these cases, the FT enzyme is predicted to retain a function in histidine breakdown. However, certain genomes such as E. minutum and S. aciditrophicus lack the hutHUI genes, and the latter lacks CD as well (Fig. 2A). Such conservation of FT in the absence of other histidine utilization genes implies a second function.

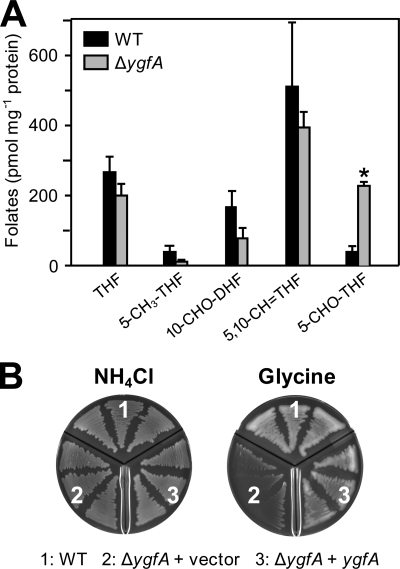

Phenotype of the E. coli ygfA Deletant

In order to develop a functional complementation test for alternatives to 5-FCL, we first determined the effects on folate metabolism and growth of deleting the ygfA gene in E. coli (which has no FT gene). The deletion was made in the standard K12 strain MG1655 by P1-transduction from a Keio collection strain (28). The deletant grew normally on LB rich medium or M9 minimal medium, and folate analysis detected little or no intracellular accumulation of 5-CHO-THF (not shown). However, supplementing M9 medium with glycine caused a 6-fold accumulation of 5-CHO-THF (Fig. 3A), presumably because the SHMT side-reaction that generates 5-CHO-THF is promoted by bound glycine (2). Glycine supplementation did not affect growth of the deletant but completely replacing the NH4Cl nitrogen source in M9 medium with 50 mm glycine led to a severe growth defect (Fig. 3B). This defect is likely due to a buildup of 5-CHO-THF inhibiting SHMT (6) and glycine cleavage (41), both of which E. coli needs to use glycine as nitrogen source (42). The growth defect was reversed by expressing the E. coli ygfA gene from a plasmid (Fig. 3B). These observations establish the ygfA deletant as a suitable platform for complementation tests of possible alternatives to 5-FCL.

FIGURE 3.

Characterization of the E. coli ΔygfA mutant. A, deletion of ygfA causes a 6-fold increase in cellular 5-CHO-THF content, significant at p < 0.05 by t test (asterisk). Folate analysis was performed on E. coli wild-type (WT) and deletant (ΔygfA) cells grown on M9 minimal medium supplemented with 0.2% glucose and 7 mm glycine. Data are means and S.E. from three replicates. 10-CHO-DHF, 10-formyldihydrofolate; other folate abbreviations are as in the legend to Fig. 1 and the abbreviations footnote. B, growth phenotype of the ΔygfA deletant. E. coli wild type or ΔygfA cells transformed with pBS II SK alone or harboring ygfA were plated on minimal medium containing either 20 mm NH4Cl or 50 mm glycine as sole nitrogen source. Plates were incubated for 3 days.

Complementation of the ΔygfA Strain by Prokaryotic Formiminotransferase Genes

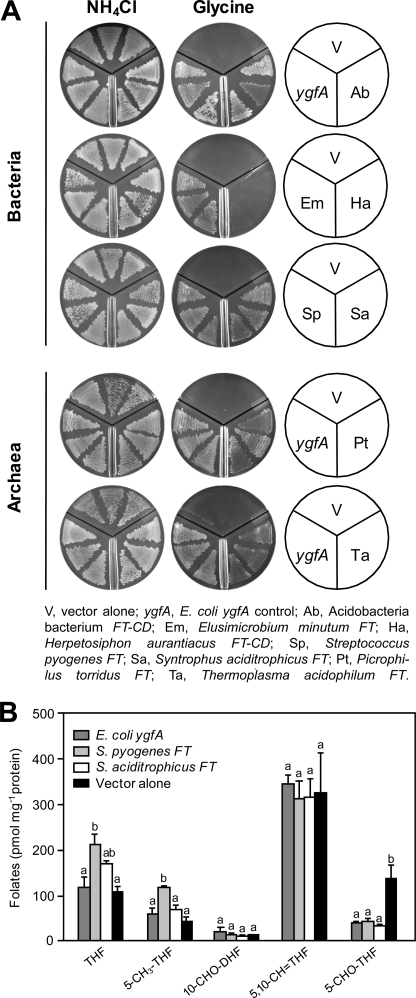

The ΔygfA deletant was transformed with pBS II SK alone or containing FT genes from five bacteria and two archaea; two of the genes were FT-CD fusions (Fig. 2A). E. coli ygfA served as a positive control. Transformants were plated on M9 medium containing NH4Cl or 50 mm glycine as nitrogen source. All strains grew well on NH4Cl, indicating that none of the FT genes was toxic. Six out of the seven FT genes tested permitted good growth on glycine (Fig. 4A), indicating that they can functionally replace 5-FCL. The exception, H. aurantiacus FT-CD, may be a pseudogene; uniquely, the histidine utilization (hut) operon in H. aurantiacus is entirely broken up, suggesting that this pathway no longer functions. Also, related bacteria (e.g. Roseiflexus spp.) entirely lack FT and most other histidine utilization genes. Folates were analyzed in ΔygfA cells harboring vector alone, or containing representative FT genes (from S. pyogenes and S. aciditrophicus) or E. coli ygfA as a control. The data confirmed that FTs can replace 5-FCL: both FT genes reversed the accumulation of 5-CHO-THF as effectively as E. coli ygfA (Fig. 4B); the effects of FT expression on other folates were minor.

FIGURE 4.

Functional complementation of the E. coli ΔygfA deletant with various formiminotransferase genes. A, complementation of the growth phenotype. The ΔygfA strain harboring pBS II SK alone or containing E. coli ygfA, or various FT or FT-CD genes, was plated on M9 medium containing 0.2% glucose, 1 mm IPTG, and either 20 mm NH4Cl or 50 mm glycine as nitrogen source. Plates were incubated for 3 days. B, folate contents of ΔygfA cells expressing pBS II SK alone or containing E. coli ygfA, S. pyogenes FT, or S. aciditrophicus FT. Cells were grown in M9 medium containing 0.2% glucose, 1 mm IPTG, and 7 mm glycine, and harvested when A600 reached 1.0. Data are means and S.E. from three replicates. For each folate, means marked with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.01, one-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak test). Folate abbreviations are as in the legend to Fig. 3.

Function of S. pyogenes FT in Its Native Host

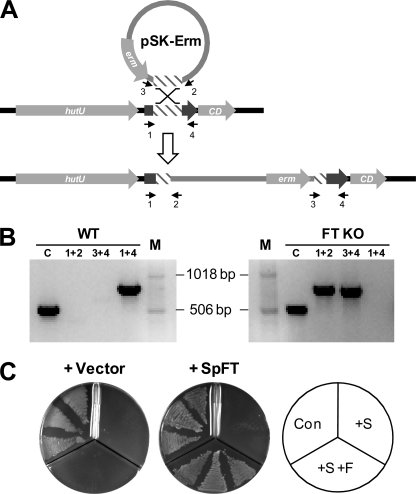

To reinforce the above evidence from heterologous expression that FT functions in vivo in 5-CHO-THF metabolism, we investigated the function of the FT from S. pyogenes in its native host. S. pyogenes was selected because it is genetically manipulable and a model human pathogen (43). We first ablated the FT gene by single crossover integration (Fig. 5A); qRT-PCR tests confirmed lack of FT expression in the disruptant and detected weak expression in wild-type cells (not shown). The disruption had no impact on the growth or the folate profile of cells cultured on TH-HS or CDM medium (not shown). This may reflect the low level of FT expression in wild-type cells, itself due to the FT gene being in a histidine operon (Fig. 5A) that is repressed by the culture conditions (44, 45). We therefore compared the FT disruptant strain with or without the native gene expressed from a plasmid. In this comparison, folate synthesis was blocked by the antifolate drug sulfathiazole, resulting in inhibition of growth, and 5-CHO-THF was supplied to attempt to reverse the inhibition. For reversal to occur, cells must take up 5-CHO-THF and convert it to other folates. Expression of S. pyogenes FT effectively reversed sulfathiazole inhibition (Fig. 5B), showing that this gene confers the capacity to metabolize 5-CHO-THF when expressed in its native host. This result also shows that S. pyogenes has a folate transport system, as do other Firmicutes (46).

FIGURE 5.

Evidence that the S. pyogenes formiminotransferase gene mediates 5-CHO-THF metabolism in its native host. A, construction of a null FT mutant by single crossover recombination (not drawn to scale). A 0.4-kb FT fragment (hatched box) was cloned into pSK-Erm, which contains the erm erythromycin resistance gene. Recombination between vector-borne and target FT sequences led to insertional inactivation of FT. B, PCR using pairs of vector and FT primers (numbers 1–4) verified the mutant; the queT gene served as a positive control (lane C). Lane M shows molecular size markers. Note that PCR with FT-specific primers (1 + 4) failed in the disruptant (FT KO), whereas a 0.8-kb band was amplified in the wild type (WT). C, rescue of S. pyogenes from antifolate blockade by 5-CHO-THF when the FT gene is expressed. The S. pyogenes disruptant harboring pAT28 alone or containing the S. pyogenes FT gene was plated on CDM containing 1% glucose alone (Con), or supplemented with 200 μm sulfathiazole (+S) or 200 μm sulfathiazole plus 50 μm 5-CHO-THF (+S +F). Plates were incubated for 2 days.

In Vitro Activities of Formiminotransferase Proteins

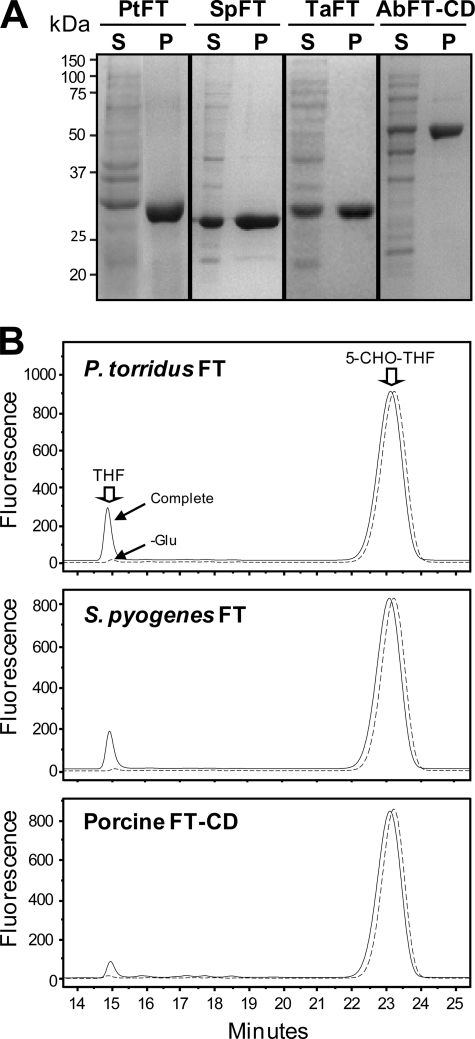

To show directly that prokaryote FT and FT-CD proteins have formyltransferase activity, His-tagged recombinant proteins were purified and assayed for formyltransferase activity in both directions. Formiminotransferase activity in the physiological direction (FIGLU + THF → Glu + 5-NH=CH-THF) was measured for comparison. The proteins analyzed were the FTs from S. pyogenes, P. torridus, and T. acidophilum, the FT-CD from Acidobacteria bacterium Ellin 345, and (as a benchmark) porcine FT-CD. The prokaryote protein preparations were all ≥95% homogeneous as judged by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Purification of bacterial and archaeal formiminotransferases and analysis of their formyltransferase activity. A, Ni2+-affinity purification of FTs from P. torridus (PtFT), S. pyogenes (SpFT), T. acidophilum (TaFT), and the FT-CD from Acidobacteria bacterium Ellin 345 (AbFT-CD). Total soluble proteins (S) (15 μg) and purified enzymes (P) (5–10 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue. The positions of molecular markers (kDa) are indicated. B, HPLC analysis of forward direction FT reactions (complete or minus glutamate) with P. torridus FT (0.1 μg), S. pyogenes FT (0.2 μg), or porcine FT-CD (1 μg) as a positive control. Reactions were run for 10 min (prokaryotic FTs) or 30 min (porcine FT-CD). The positions of THF and 5-CHO-THF standards are indicated. Similar results were obtained for T. acidophilum FT and Acidobacteria bacterium FT-CD (not shown). Note that no THF was formed in the absence of glutamate, nor was THF formed when enzyme was omitted or preboiled (not shown).

All the prokaryote enzymes catalyzed glutamate-dependent THF formation from 5-CHO-THF (Fig. 6B); the fact that no THF was formed in the absence of glutamate demonstrates that the reaction is a formyl transfer, not simply a deformylation. The porcine FT-CD control mediated the same reaction, as expected (40). None of the prokaryote enzymes catalyzed detectable THF formation when glutamate was replaced by any of the other 19 protein amino acids, indicating high specificity for glutamate as formyl acceptor. Kinetic characterization of the formyltransferase activities (Table 1) showed Km values in the micromolar range for 5-CHO-THF and for its triglutamate form; as triglutamates have been found to be the predominant folates in growing cells of various bacteria (47) the latter result confirms the effectiveness of the physiological form of the cofactor. The Km values for glutamate were two orders of magnitude greater. The kcat values for the prokaryote enzymes were equal to or greater than that for the porcine enzyme, and in one case (P. torridus) the difference was 10-fold. Because P. torridus FT also had the lowest Km value for 5-CHO-THF (Table 1), this result suggests that the P. torridus enzyme may have become more efficient in formyl transfer relative to formimino transfer.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic constants for formyltransferase activities measured in the forward direction

Data are means of triplicate determinations ± S.E.

| Enzyme | Km (5-CHO-THF)a | Km (5-CHO-THF-Glu3)a | Km (l-glutamate) | kcatb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | μm | μm | min−1 | |

| S. pyogenes FT | 5.4 ± 0.7 | 4.8 ± 1.3 | 1030 ± 30 | 0.13 ± 0.01 |

| P. torridus FT | 0.40 ± 0.04 | 0.70 ± 0.2 | 34 ± 6 | 1.16 ± 0.05 |

| T. acidophilum FT | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 113 ± 30 | 0.27 ± 0.03 |

| Acidobacteria bacterium FT-CD | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 276 ± 45 | 0.55 ± 0.03 |

| Porcine FT-CD | 7.2 ± 0.3 | 5.8 ± 0.4 | 206 ± 7 | 0.11 ± 0.01 |

a The cofactors used were the natural (S) form of 5-CHO-THF versus mixed natural and unnatural forms (R,S) of 5-CHO-THF-Glu3, so that Km values for 5-CHO-THF-Glu3 should be halved for comparison with those for 5-CHO-THF.

b Values for kcat were determined with 5-CHO-THF as cofactor; those determined with 5-CHO-THF-Glu3 were similar.

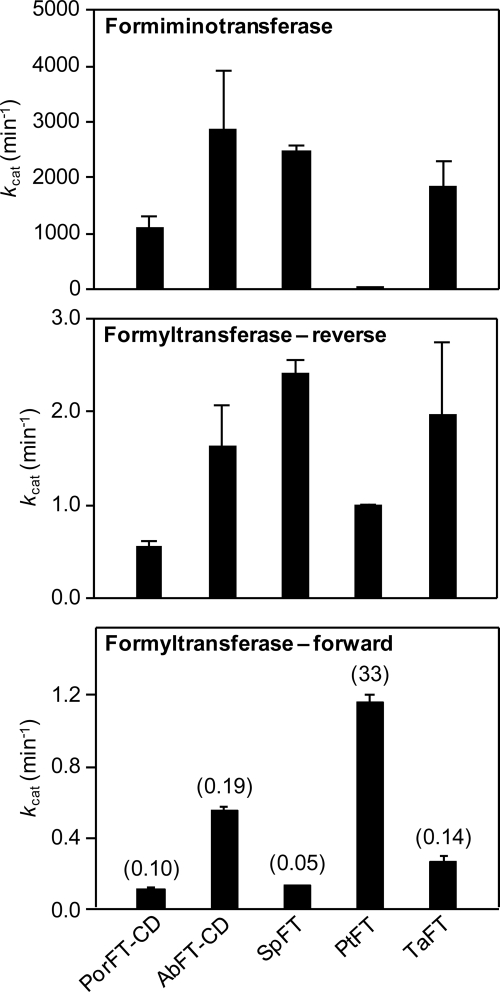

To investigate this possibility, we estimated kcat values for formiminotransferase activity (in the physiological direction) and compared them to the above values for formyltransferase in the forward direction (Fig. 7). We also measured formyltransferase kcat values for the reverse reaction, to juxtapose with the literature on the porcine FT-CD (Fig. 7); our values for this enzyme agreed with published ones (36). The forward formyltransferase/formiminotransferase ratio (in parentheses, Fig. 7, bottom panel) for P. torridus FT was 330-fold higher than that of the porcine enzyme, and 170–660-fold higher than those of the other prokaryote enzymes. The high ratio for P. torridus FT reflects a high formyltransferase activity combined with an exceptionally low formiminotransferase activity (Fig. 7). The P. torridus enzyme is thus a markedly more efficient formyltransferase than the others in terms of (i) the kcat/Km ratio for this activity and (ii) the relative magnitudes of the formyltransferase and formiminotransferase kcat values. However, even for this enzyme, the formyltransferase kcat value is 30-fold less than the formiminotransferase kcat value; for the other prokaryote enzymes, and for porcine FT, the formyltransferase kcat values are ∼5,000–20,000-fold less than the formiminotransferase kcat values. Formyltransferase activity is thus not the major activity in any of the enzymes tested.

FIGURE 7.

Comparison of kcat values for the formimino- and formyltransferase activities of glutamate formiminotransferases. Data are mean values ± S.E. from three replicates. Top panel, formiminotransferase activity in the physiological direction (FIGLU + THF → glutamate + 5-NH=CH-THF). Middle panel, formyltransferase activity in the reverse direction (N-formylglutamate + THF → glutamate + 5-CHO-THF). Bottom panel, formyltransferase activity in the forward direction (glutamate + 5-CHO-THF → N-formylglutamate + THF); the ratio of each forward kcat to the corresponding formiminotransferase kcat in per mil units (‰) is given in parentheses. Por, porcine; Ab, Acidobacteria bacterium; Sp, S. pyogenes; Pt, P. torridus; Ta, T. acidophilum.

DISCUSSION

The comparative genomic, genetic, and biochemical data presented above support the conclusion that the formyltransferase activity of the histidine degradation enzyme FT replaces 5-FCL in diverse prokaryotes. Most of these enzymes presumably retain their principal function in histidine catabolism because they have high formiminotransferase activity in vitro and their genes co-occur with the other genes of histidine breakdown, sometimes in operonic arrangements. Such FTs can therefore be viewed as moonlighting enzymes, i.e. as metabolic enzymes with an additional functional activity (48), in this case 5-CHO-THF salvage. As previously noted, however, some FTs occur in genomes that lack most or all other histidine degradation genes; in these cases the moonlighting activity may have become the only physiological one.

Although the in vitro formyltransferase activity of FTs is much lower than their formiminotransferase activity, three factors may enable the formyltransferase activity to function effectively in 5-CHO-THF removal. First, prokaryote FTs have low Km values for 5-CHO-THF (0.4 to 5.4 μm; Table 1). Second, the in vivo concentration of the glutamate substrate would be saturating, because Km values for glutamate are ≤1 mm (Table 1) and intracellular glutamate concentrations in prokaryotes are typically 30–100 mm (49–52). Third, no more than a low formyl transfer flux is needed to remove 5-CHO-THF, which is formed only by a minor side reaction (6) and which does not come to dominate the folate pool even if normal removal is blocked (Fig. 3A).

If FTs function simultaneously in histidine degradation and 5-CHO-THF salvage in the same cell, then they must carry flux in both directions because the formiminotransferase reaction consumes THF and produces glutamate and the formyltransferase salvage reaction does the opposite (Fig. 2C). Given that moonlighting functions can depend on differences in protein-protein interactions (48), it seems possible that running these opposing reactions concurrently is facilitated by FT joining/not joining a protein complex related to histidine degradation. In this connection, it is relevant that mammalian FT-CD is an octamer that can dissociate into two types of monofunctional dimers, and that while the FT and CD activities of the octamer function separately with monoglutamylated folates, polyglutamates are channeled from the FT to the CD active site (34, 53). Analogous behavior of prokaryote FT oligomers, or perhaps FT-CD complexes, together with polyglutamate-mediated channeling between FT and CD reactions, could result in the functional partitioning, i.e. mutual non-interference, of formyl- and formiminotransferase activities.

One of the FTs examined (that from the archaeon P. torridus) was far more efficient as a formyltransferase than the other prokaryote enzymes, which were themselves comparable in efficiency to porcine FT-CD. These findings are consistent with natural selection of the P. torridus protein for increased formyltransferase activity. They also imply that mammalian FT-CD cannot be ruled out a priori as a contributor to 5-CHO-THF salvage, particularly because glutamate levels in liver(to which FT-CD is confined) far exceed the Km for glutamate (206 μm; Table 1) (54). However, any contribution from FT-CD is probably small relative to that from 5-FCL because 5-FCL is highly expressed in liver (55) and its specific activity appears to be at least one order of magnitude greater than that of FT-CD formyltransferase (36, 56).

In removing 5-CHO-THF, the formyltransferase reaction generates N-formylglutamate (Fig. 2C), which is a metabolic dead-end that can apparently be metabolized only via hydrolysis to glutamate and formate. Although a dedicated N-formylglutamate hydrolase (Fig. 2, NfoD) participates in histidine degradation in certain bacteria (18, 57), this protein is absent from prokaryotes in which FT replaces 5-FCL (Fig. 2). However, deacylation of amino acids is a common reaction and nonspecific enzymes that hydrolyze N-formylglutamate have been reported from bacteria and other organisms (58, 59).

Finally, because our comparative genomic analysis indicated that FT occurs in only 46% of the genomes with SHMT (glyA) and without 5-FCL (ygfA), it is likely that at least one other gene for 5-CHO removal remains to be discovered in prokaryotes. Such a hypothetical missing gene might also be present in plants. Ablating the single gene encoding 5-FCL in Arabidopsis results in only a 2-fold increase in leaf 5-CHO-THF content, suggesting that 5-FCL is not the sole route for 5-CHO-THF disposal (9).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. R. E. MacKenzie for the porcine formiminotransferase-cyclodeaminase clone and for helpful discussions, Dr. I. Biswas for S. pyogenes strain JRS4 and plasmid pSK-Erm, Dr. L. N. Csonka for predicting the growth phenotype of the E. coli ΔygfA mutant, and M. J. Ziemak for technical advice and help.

This work was supported in part by United States (U.S.) National Science Foundation Award MCB-0839926 (to A. D. H.), by U.S. Dept. of Energy award FG02-07ER64498 (to V. de C. L.), by National Institutes of Health Award R03-DE019179 (to K. C. R.), and by an endowment from the C. V. Griffin, Sr. Foundation.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1.

- 5-CHO-THF

- 5-formyltetrahydrofolate

- 5,10-CH=THF

- 5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolate

- 5-NH=CH-THF

- 5-formiminotetrahydrofolate

- 5-FCL

- 5-formyltetrahydrofolate cycloligase

- FIGLU

- N-formimino-l-glutamate

- FT

- glutamate formiminotransferase

- FT-CD

- glutamate formiminotransferase-cyclodeaminase

- IPTG

- isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside

- SHMT

- serine hydroxymethyltransferase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stover P., Schirch V. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 14227–14233 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stover P., Schirch V. (1992) Biochemistry 31, 2155–2164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kruschwitz H. L., McDonald D., Cossins E. A., Schirch V. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 28757–28763 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelletier J. N., MacKenzie R. E. (1996) Bioorg. Chem. 24, 220–228 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baggott J. E. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 14647–14653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stover P., Schirch V. (1993) Trends Biochem. Sci. 18, 102–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes W. B., Appling D. R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 20205–20213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roje S., Janave M. T., Ziemak M. J., Hanson A. D. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 42748–42754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goyer A., Collakova E., de la Garza R. D., Quinlivan E. P., Williamson J., Gregory J. F., 3rd, Shachar-Hill Y., Hanson A. D. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 26137–26142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Field M. S., Szebenyi D. M., Perry C. A., Stover P. J. (2007) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 458, 194–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanson A. D., Roje S. (2001) Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 52, 119–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tibbetts A. S., Appling D. R. (2010) Annu. Rev. Nutr. 30, 57–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthews R. G. (1996) in Escherichia coli and Salmonella, Cellular and Molecular Biology (Neidhardt F. C. ed) Vol. 1, pp. 600–611, American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D. C [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glass J. I., Lefkowitz E. J., Glass J. S., Heiner C. R., Chen E. Y., Cassell G. H. (2000) Nature 407, 757–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White R. H. (1991) J. Bacteriol. 173, 1987–1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Crécy-Lagard V., El Yacoubi B., de la Garza R. D., Noiriel A., Hanson A. D. (2007) BMC Genomics. 8, 245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanson A. D., Pribat A., Waller J. C., de Crécy-Lagard V. (2010) Biochem. J. 425, 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Overbeek R., Begley T., Butler R. M., Choudhuri J. V., Chuang H. Y., Cohoon M., de Crécy-Lagard V., Diaz N., Disz T., Edwards R., Fonstein M., Frank E. D., Gerdes S., Glass E. M., Goesmann A., Hanson A., Iwata-Reuyl D., Jensen R., Jamshidi N., Krause L., Kubal M., Larsen N., Linke B., McHardy A. C., Meyer F., Neuweger H., Olsen G., Olson R., Osterman A., Portnoy V., Pusch G. D., Rodionov D. A., Rückert C., Steiner J., Stevens R., Thiele I., Vassieva O., Ye Y., Zagnitko O., Vonstein V. (2005) Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 5691–5702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. (2007) Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1596–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Temple C. T., Montgomery J. A. (1984) in Folates and Pterins, Vol. 1, 2nd Ed. (Blakley R. L., Benkovic S. J. eds) pp. 61–120, Wiley, New York [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tabor H., Mehler A. H. (1954) J. Biol. Chem. 210, 559–568 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabor H., Rabinowitz J. C. (1957) Biochem. Prep. 5, 100–105 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Ed., Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neidhardt F. C., Bloch P. L., Smith D. F. (1974) J. Bacteriol. 119, 736–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott J. R., Guenthner P. C., Malone L. M., Fischetti V. A. (1986) J. Exp. Med. 164, 1641–1651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon D., Ferretti J. J. (1991) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 82, 219–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van de Rijn I., Kessler R. E. (1980) Infect. Immun. 27, 444–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baba T., Ara T., Hasegawa M., Takai Y., Okumura Y., Baba M., Datsenko K. A., Tomita M., Wanner B. L., Mori H. (2006) Mol. Syst. Biol. 2, 2006.0008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biswas I., Scott J. R. (2003) J. Bacteriol. 185, 3081–3090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Que Y. A., Haefliger J. A., Francioli P., Moreillon P. (2000) Infect. Immun. 68, 3516–3522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biswas I., Jha J. K., Fromm N. (2008) Microbiology 154, 2275–2282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trieu-Cuot P., Carlier C., Poyart-Salmeron C., Courvalin P. (1990) Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon D., Chopin A. (1988) Biochimie 70, 559–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murley L. L., MacKenzie R. E. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 10358–10364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bradford M. M. (1976) Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bortoluzzi L. C., MacKenzie R. E. (1983) Can. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 61, 248–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gregory J. F., 3rd, Sartain D. B., Day B. P. (1984) J. Nutr. 114, 341–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfeiffer C. M., Rogers L. M., Gregory J. F. (1997) J. Agric. Food Chem. 45, 407–413 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bagley P. J., Selhub J. (2000) Clin. Chem. 46, 404–411 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silverman M., Keresztesy J. C., Koval G. J., Gardiner R. C. (1957) J. Biol. Chem. 226, 83–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee H. H., Kim D. J., Ahn H. J., Ha J. Y., Suh S. W. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 50514–50523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newman E. B., Batist G., Fraser J., Isenberg S., Weyman P., Kapoor V. (1976) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 421, 97–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sitkiewicz I., Nagiec M. J., Sumby P., Butler S. D., Cywes-Bentley C., Musser J. M. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 16009–16014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wray L. V., Jr., Pettengill F. K., Fisher S. H. (1994) J. Bacteriol. 176, 1894–1902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chasin L. A., Magasanik B. (1968) J. Biol. Chem. 243, 5165–5178 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodionov D. A., Hebbeln P., Eudes A., ter Beek J., Rodionova I. A., Erkens G. B., Slotboom D. J., Gelfand M. S., Osterman A. L., Hanson A. D., Eitinger T. (2009) J. Bacteriol. 191, 42–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arnold R. J., Reilly J. P. (2000) Anal. Biochem. 281, 45–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jeffery C. J. (2004) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14, 663–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tian J., Bryk R., Itoh M., Suematsu M., Nathan C. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 10670–10675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anderson C. B., Witter L. D. (1982) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 43, 1501–1503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brabban A. D., Orcutt E. N., Zinder S. H. (1999) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 1222–1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bennett B. D., Kimball E. H., Gao M., Osterhout R., Van Dien S. J., Rabinowitz J. D. (2009) Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 593–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Findlay W. A., MacKenzie R. E. (1987) Biochemistry 26, 1948–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bergmeyer H. U. (1974) Methods of Enzymatic Analysis, Vol. 4, p. 2285, Verlag Chemie, Weiheim, New York and London [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anguera M. C., Suh J. R., Ghandour H., Nasrallah I. M., Selhub J., Stover P. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 29856–29862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thompson H. R., Jones G. M., Narkewicz M. R. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 280, G873–G878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu L., Mulfinger L. M., Phillips A. T. (1987) J. Bacteriol. 169, 4696–4702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ohmura E., Hayaishi O. (1957) J. Biol. Chem. 227, 181–190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miyake M., Innami T., Kakimoto Y. (1983) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 760, 206–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barrick J. E., Breaker R. R. (2007) Genome Biol. 8, R239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spang A., Hatzenpichler R., Brochier-Armanet C., Rattei T., Tischler P., Spieck E., Streit W., Stahl D. A., Wagner M., Schleper C. (2010) Trends Microbiol. 18, 331–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Worrell V. E., Nagle D. P., Jr. (1988) J. Bacteriol. 170, 4420–4423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buchenau B., Thauer R. K. (2004) Arch. Microbiol. 182, 313–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.