Abstract

Chlamydia trachomatis infections cause severe and irreversible damage that can lead to infertility and blindness in both males and females. Following infection of epithelial cells, Chlamydia induces production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Unconventionally, Chlamydiae use ROS to their advantage by activating caspase-1, which contributes to chlamydial growth. NLRX1, a member of the Nod-like receptor family that translocates to the mitochondria, can augment ROS production from the mitochondria following Shigella flexneri infections. However, in general, ROS can also be produced by membrane-bound NADPH oxidases. Given the importance of ROS-induced caspase-1 activation in growth of the chlamydial vacuole, we investigated the sources of ROS production in epithelial cells following infection with C. trachomatis. In this study, we provide evidence that basal levels of ROS are generated during chlamydial infection by NADPH oxidase, but ROS levels, regardless of their source, are enhanced by an NLRX1-dependent mechanism. Significantly, the presence of NLRX1 is required for optimal chlamydial growth.

Keywords: Bacteria, Immunology, Innate Immunity, Mitochondria, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), Nod-like Receptors

Introduction

During electron transfer reactions, eukaryotic cells generate highly reactive O2 metabolites collectively known as reactive oxygen species (ROS).2 Given their high cellular toxicity, cells have developed mechanisms to maintain the levels of ROS in a homeostatic state and utilize them in cellular functions, including signaling pathways, gene expression regulation, and host defense mechanisms (1–3). Intracellular ROS generation is mediated by several enzymatic reactions, but the bulk of ROS is generated from two sources: the mitochondrial electron transport chain complex and membrane-bound NADPH oxidase (NOX and DUOX) (4).

During oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria, O2 is reduced to O2˙̄, which in turn is converted by superoxide dismutase into H2O2, which then diffuses across the mitochondrial membrane to the cytoplasm (4). Notably, NLRX1, a member of the intracellular Nod-like receptor (NLR) family that is localized in mitochondria, enhances ROS production induced by poly(I·C), TNFα, and Shigella flexneri infection (5). Although there is evidence that NLRX1 is the only NLR member that is found in mitochondria, its exact dynamic localization remains to be determined. Results from one study suggested that NLRX1 localizes to the outer mitochondrial membrane (6), but subsequent characterization suggests that NLRX1 is transported to the mitochondrial matrix, where it interacts with UQCRC2, a matrix-facing protein of respiratory chain complex III (bc1 complex). The bc1 complex is known to play an essential role in ROS generation from the mitochondria (5, 7).

Chlamydia trachomatis is the first cause of bacterial sexually transmitted disease in the United States, and the incidence of infection has been increasing for the past 20 years (8–10). The bacteria infect their preferred target cells, cervical epithelial cells, through entry vacuoles that avoid fusion with host cell lysosomes and then grow by subverting cell signaling pathways in the host cells and acquiring lipids from the Golgi apparatus (11–14). Host cells often produce ROS in response to bacterial infections as a defense mechanism to impair metabolism and growth of intracellular bacteria by inflicting damage to the pathogen's lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids (15). However, in the case of chlamydial infection of epithelial cells, the intracellular Chlamydiae stimulate the host cell to generate moderate amounts of ROS. These low levels of ROS lead to NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated caspase-1 activation, which contributes to chlamydial infection (16). Although the basis for caspase-1 stimulation of chlamydial infection is not known, caspase-1 has many non-inflammatory substrates and can stimulate metabolism of host cell lipids (17, 18). Therefore, we investigated the sources of intracellular ROS generation in epithelial cells during infection with C. trachomatis.

Here, we show that both NOX/DUOX and NLRX1 contribute to C. trachomatis-dependent ROS production. Inhibition of NOX/DUOX resulted not only in abrogation of ROS production but also lower chlamydial growth. Specifically, depletion of NOX/DUOX superfamily members NOX4, DUOX1, and DUOX2 resulted in lower ROS production during infection. Similarly, silencing NLRX1 expression led to a significant decrease in ROS levels during chlamydial infection, whereas overexpression of NLRX1 augmented Chlamydia-induced ROS production. NLRX1 enhanced ROS levels even when cells were treated with extracellular H2O2, suggesting that mitochondrial NLRX1 can enhance ROS levels regardless of their source. Our data indicate that ROS, usually produced in large quantities by immune cells to limit the growth of invading pathogens, is utilized by Chlamydia to promote its own growth and is generated from two sites: membrane-bound NOX and mitochondrial NLRX1.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells, Bacteria, and Chemical Reagents

Human cervical epithelial cells (HeLa 229 cells) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection, and Nlrx1−/− mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells were derived from Nlrx1−/− animals (produced together with genOway). The LGV/L2 strain of C. trachomatis was grown as described previously (19). HeLa cells were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in DMEM/F-12 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen) and 10 μg/ml gentamycin (Omega Scientific, Tarzana, CA). MEF cells were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Invitrogen), 1% nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), and 10 μg/ml gentamycin. C. trachomatis cells were grown in infected HeLa cell monolayer cultures to determine the number of bacterial inclusion-forming units as described previously (20). Diphenyliodonium chloride (DPI) was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals. Lipofectamine 2000 was purchased from Invitrogen. Hydrogen peroxide and the monoclonal antibody against tubulin were purchased from Sigma. The anti-NLRX1 polyclonal antibody was made as described previously (7).

Generation of siRNA against Human NLRX1

The sequences (sense strand) of the siRNA targeting NLRX1 and the scrambled siRNA were as follows: 5′-GAGGAGGACTACTACAACGAT-3′ (NLRX1) and 5′-GTGCAGGAGTAGGGCATTTAA-3′ (scrambled). The pLKO.1 lentiviral knockdown system (Addgene, Cambridge, MA) was used to generate lentiviral shRNA particles, and oligonucleotides containing the siRNA sequences were designed according to the pLKO.1 protocol of Addgene. Annealed oligonucleotides were ligated with digested pLKO.1 plasmid (EcoRI/AgeI) for 4 h at 16 °C, and positive clones were identified by restriction enzyme digestion (EcoRI/NcoI). shRNA constructs were fully sequenced with the pLKO.1 sequencing primer (5′-AAGGCTGTTAGAGAGATAATTGGA-3′).

Lentiviral Packaging

Packaging and purification of the lentivirus were performed according to standard procedures. HEK293T cells (1.6 × 106 cells) were seeded in a 10-cm culture dish in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS without antibiotics. The following day, cells were cotransfected with the lentiviral vector (1 μg) and the lentiviral packaging/envelope vectors psPAX2 (750 ng) and pMD2.G (250 ng). Viruses were collected from the culture supernatant 24–48 h post-transfection and spun at 1250 rpm for 5 min, and the medium was passed through a 0.45-μm filter.

Lentiviral Transduction in HeLa cells

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates and then incubated with lentivirus for at least 3 days in the presence of Polybrene (10 μg/ml). Cells that were successfully transfected were selected by adding a fresh medium that contained 2 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma) and further incubated for 24 h. Knockdown of NLRX1 protein expression was confirmed by Western blotting using rabbit anti-NLRX1 polyclonal antibody designed against CQLVAQRYTPLKEV (amino acids 214–227) of NLRX1 (Cedarlane Laboratories, Hornby, Canada).

Transient Transfection of HeLa Cells

The NLRX1-FLAG overexpression construct described previously (5) was transiently transfected into HeLa cells using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were plated 1 day before transfection so that cells would be 95% confluent at the time of transfection. Lipofectamine 2000 mixture was prepared by diluting the appropriate amount in serum-free medium (4 μl of Lipofectamine/1.6 μg of DNA) and incubating for 5 min at room temperature. A plasmid mixture was then prepared by diluting plasmid DNA in serum-free medium. The DNA and Lipofectamine mixtures were combined gently and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. DNA/Lipofectamine complexes were then added dropwise to each well containing cells and serum-free medium, and cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 6 h, detached using TrypLETM Express (Invitrogen), and plated to obtain 50% confluency after 18 h.

NADPH Oxidase Components

NOX1, NOX4, DUOX1, and DUOX2 were each depleted with three different siRNA constructs as described previously (21). The sequences of the NOX1 siRNA constructs were 5′-AAAACAUUCAGCCCUAACCaa-3′, 5′-AAUGUUGACCCAAGGAUUUtt-3′, and 5′-UGUGAUCCAAUUGCUUUCUca-3′. The sequences of the NOX4 siRNA constructs were 5′-GUGAUACUCUGGCCCUUGGtt-3′, 5′-UUAUCCAACAAUCUCCUGGtt-3′, and 5′-UGGUUAUACAGCAAGAAGGtt-3′. The sequences of the DUOX1 siRNA constructs were 5′-AUCUUCAACCAACACAUGGTC-3′, 5′-UACACGCCAUCUGCAUAGCtg-3′, and 5′-GUACCACCCAUCAAAUCGCtg-3′. The sequences of the DUOX2 siRNA constructs were 5′-CAUUAGACGGGACUUAUCCtg-3′, 5′-ACCUUCCGGAAAUGACAGCTG-3′, and 5′-UUCAACCACUAUGUUGUCCtc-3′. Control siRNA (MISSION siRNA universal negative control, Sigma) was used as a control for the knockdown procedure. Cells were transfected with siRNA constructs and Lipofectamine 2000 reagent following the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell Culture, Infection, and Treatments

HeLa cells growing at 50% confluency on tissue culture plates (Costar, Corning, NY) were infected with the LGV/L2 strain of C. trachomatis at a multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) of 3.0 unless specified otherwise and incubated for the indicated times in an incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. MEF cells growing at 80% confluency on tissue culture plates were infected with the LGV/L2 strain of C. trachomatis at an m.o.i. of 3.0 and incubated for 24 h in an incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Treatment with inhibitors or other reagents was performed at the indicated times and concentrations.

Measurement of ROS Production

HeLa cells were labeled with the cell-permeant ROS indicator 5(6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate acetyl ester (DCF; Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were plated in phenol red-free DMEM containing 10% FBS and then infected and/or treated for the indicated times. Cells were detached using TrypLETM Express, loaded with 2.5 μm DCF in PBS for 15 min at 37 °C, washed with PBS, resuspended in growth medium, and finally analyzed by flow cytometry with a Guava EasyCyte system with a 15-milliwatt argon ion laser at 488 nm. Fluorescence was measured on the FL1 (green) channel, gating only on live cells.

FLICA Staining

During the last hour of incubation, cells were labeled using a carboxyfluorescein-YVAD-fluoromethyl ketone caspase-1 FLICATM kit (ImmunoChemistry Technologies, Bloomington, IN), which binds to activated caspase-1. Flow cytometric analysis was performed as described previously (16). Briefly, cells were detached using TrypLETM Express and then incubated with FLICA for 1 h, followed by two washes and analysis using the Guava EasyCyte system.

Immunocytochemical Staining and Fluorescence Microscopy

For MitoTracker and indirect anti-FLAG immunocytochemical staining, cells were grown on coverslips and then transfected with the NLRX1-FLAG construct as described above. Cells were loaded with 500 nm MitoTracker® Orange (Molecular Probes) and incubated for 45 min at 37 °C, followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) for 15 min at room temperature (22). Fixed cells were probed with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody M2 (1:1000; Sigma) for 2 h at 37 °C, followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (Sigma) for 45 min at 37 °C. During the last 5 min of incubation, Hoechst stain (Sigma) was added, and cells were viewed on a wide-field fluorescence microscope (Leica, Deerfield, IL). Hoechst, NLRX1-FLAG, and MitoTracker® were viewed with blue, green, and red filters, respectively. For direct anti-FLAG immunocytochemical staining, cells were fixed with a freshly prepared mixture of methanol/acetone (1:1) and incubated with Cy3TM-conjugated anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody M2 (Sigma) at 1 mg/ml for 1 h. Anti-chlamydial antibody (Argene, Massapequa, NY) and Hoechst stain were added during the last 15 and 5 min of incubation, respectively. Cells were mounted on a glass slide, sealed with nail polish, and viewed with a Leica wide-field fluorescence microscope. Hoechst, Chlamydiae, and NLRX1-FLAG were viewed with the blue, green, and red filters, respectively.

RNA Isolation and Real-time PCR

mRNA was isolated from cells after the indicated treatments or infections using the Qiagen RNeasy kit following the manufacturer's instructions, and total RNA was converted into cDNA by standard reverse transcription with the TaqMan reverse transcriptase kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). For measurements of chlamydial 16 S rRNA, total mRNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative PCR was performed with the cDNA preparation (1:50) in the Mx3000P system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) in a 25-μl final volume with Brilliant QPCR Master Mix (Stratagene). The primers for human GAPDH were 5′-CTTCTCTGATGAGGCCCAAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCAGCAAACTGGAAAGGAAG-3′ (reverse). The primers for human NLRX1 were 5′-GTGCCCGGAAGCTGGGCTTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCGGGCACCACCTTCAGCAG-3′ (reverse). The primers for human NOX1 were 5′-CACCCCAAGTCTGTAGTGGGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCAGACTGGAATATCGGTGAC-3′ (reverse). The primers for human NOX4 were 5′-GGGCTTCCACTCAGTCTTTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTTGAGGGCATTCACCAGAT-3′ (reverse). The primers for human DUOX1 were 5′-TTCACGCAGCTCTGTGTCAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGGGACAGATCATATCCTGGCT-3′ (reverse). The primers for human DUOX2 were 5′-ACGCAGCTCTGTGTCAAAGGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGATGAACGAGACTCGACAGC-3′ (reverse). The primers for C. trachomatis 16 S rRNA were 5′-CCCGAGTCGGCATCTAATAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTACGCATTTCACCGCTACA-3′ (reverse). The primers for murine IFN-β were described previously (23). Real-time PCR included initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min and one cycle at 95 °C for 1 min, 55 °C for 30 s, and 95 °C for 30 s. For human genes, the CT values were normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH. For chlamydial 16 S RNA measurements, equal amounts of cDNA were loaded in all samples.

Statistical and Flow Cytometric Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad InStat software by Student's t test and was considered significant at p < 0.05. Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

NLRX1 Overexpression Augments C. trachomatis-induced ROS Production

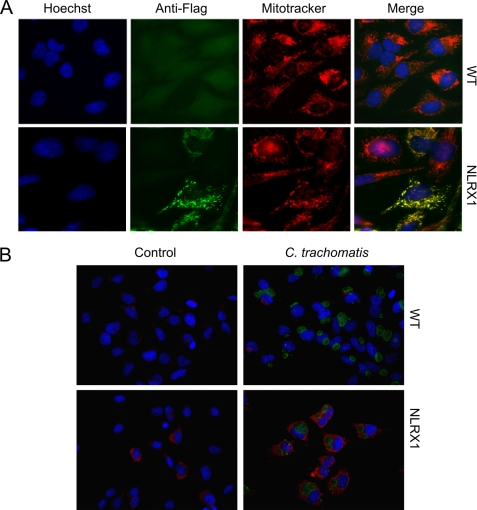

A recent study demonstrated that NLRX1, the only NLR family member that translocates to the mitochondria, enhances ROS production induced by cytokines and S. flexneri infection (5). To test whether NLRX1 may play a role in Chlamydia-induced ROS production, we overexpressed NLRX1 using the NLRX1-FLAG construct in HeLa cells. First, we confirmed by immunofluorescence microscopy that NLRX1 is overexpressed in HeLa cells and that it translocates to mitochondria (Fig. 1A). We also verified that C. trachomatis infection of NLRX1-overexpressing epithelial cells does not affect the distribution of NLRX1 (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

NLRX1 translocation to mitochondria in infected and uninfected cells. HeLa cells growing on coverslips were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent with the NLRX1-FLAG construct and infected or mock-infected with the LGV/L2 strain of C. trachomatis at an m.o.i. of 3 for 24 h. A, uninfected cells were fixed and stained with Hoechst stain (blue), MitoTracker® (red), and anti-FLAG antibody (green). B, infected cells were stained with Cy3-conjugated anti-FLAG antibody (red) and anti-chlamydial antibody (green). In both cases, the cells were visualized on a fluorescence microscope. WT, wild-type (Lipofectamine only).

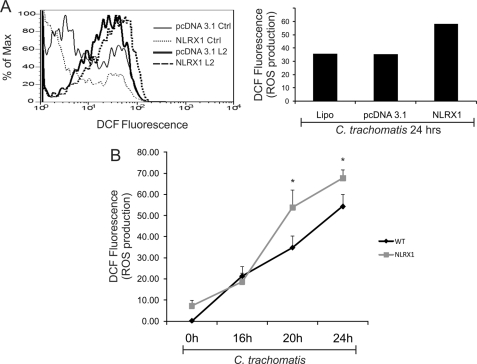

We then measured ROS production in C. trachomatis-infected HeLa cells treated with Lipofectamine alone or transfected with empty vector or with NLRX1-FLAG. We demonstrated that NLRX1-overexpressing HeLa cells produced higher levels of ROS in response to C. trachomatis infection than those treated with Lipofectamine (control) or transfected with empty vector (Fig. 2A). Consistent with the previous observation that ROS production during C. trachomatis infection increases 20 h post-infection and continues to increase at 24 h post-infection (16), NLRX1-dependent enhancement of ROS production was observed especially at 20 and 24 h post-infection (Fig. 2B). These data imply that NLRX1 may contribute to Chlamydia-induced ROS production in epithelial cells.

FIGURE 2.

NLRX1 overexpression augments C. trachomatis-induced ROS production. HeLa cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Lipo) with empty vector (pcDNA3.1) or the NLRX1-FLAG construct and infected or mock-infected with the LGV/L2 strain of C. trachomatis at an m.o.i. of 3. A, cells were infected or mock-infected for 24 h. ROS production was measured with the ROS-sensitive dye DCF and analyzed by flow cytometry. Non-fluorescent cells were gated in the first log decade, and the fluorescence intensity was proportional to the level of ROS production. Flow cytometry data of infected cells are presented as a histogram (left panel), and the amount of ROS production in infected cells relative to uninfected controls (Ctrl) is presented as a bar chart (right panel). Data are from one representative experiment. B, cells were infected or mock-infected for 0, 16, 20, or 24 h, and ROS production was measured by flow cytometry under the same conditions as described for A. Relative ROS levels were quantified as the mean DCF fluorescence, and the values measured in uninfected wild-type cells were subtracted from the other conditions. Error bars represent S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05 compared with wild-type infected cells (Lipofectamine only).

NLRX1 Enhances ROS Generation during Chlamydial Infection

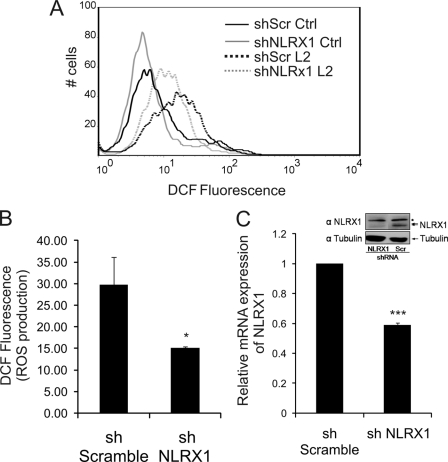

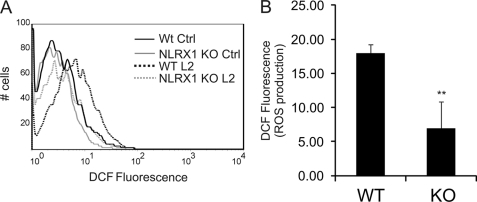

The NLRX1 overexpression system suggested a potential role for NLRX1 in C. trachomatis-induced ROS production. We further investigated this possibility by reducing expression of endogenous NLRX1 in epithelial cells using shRNA that specifically targets NLRX1 mRNA. Expression of NLRX1 mRNA was significantly reduced in comparison with cells transfected with non-target shRNA as measured by real-time PCR (Fig. 3C), and depletion of NLRX1 protein was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3C, inset). Depletion of NLRX1 caused a reduction of ∼50% in the production of ROS after 24 h of C. trachomatis infection compared with HeLa cells that were transfected with scrambled shRNA (control) (Fig. 3, A and B). These results were confirmed using MEFs from Nlrx1 knock-out mice. When Nlrx1 knock-out MEFs were infected with C. trachomatis for 24 h, there was significantly less ROS produced than when wild-type MEFs were infected (Fig. 4, A and B). Collectively, these data indicate that NLRX1 contributes to generation of ROS during infection with C. trachomatis.

FIGURE 3.

NLRX1 contributes to C. trachomatis-induced ROS production in epithelial cells. HeLa cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent with scrambled (shScr Ctrl) and NLRX1 (shNLRX1) shRNA constructs and infected or mock-infected with C. trachomatis at an m.o.i. of 3 for 24 h. A, ROS production was measured with DCF and analyzed by flow cytometry. Non-fluorescent cells were gated in the first log decade, and the fluorescence intensity was proportional to the level of ROS production. B, the bar chart represents ROS production in C. trachomatis-infected HeLa cells analyzed by flow cytometry under the conditions described for A. C, mRNA expression of NLRX1 was quantified by real-time PCR and compared with the scrambled shRNA (sh Scramble). Inset, HeLa cells were transduced for 72 h with lentiviruses expressing either NLRX1 shRNA or scrambled shRNA (Scr shRNA), and NLRX1 expression was determined by Western blotting using anti-NLRX1 antibody. Protein loading was controlled using an anti-tubulin antibody. The asterisk indicates a nonspecific band. Error bars represent S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001 compared with scrambled shRNA-infected cells.

FIGURE 4.

NLRX1 contributes to C. trachomatis-induced ROS production in murine fibroblasts. Wild-type (WT) or Nlrx1 knock-out (KO) MEFs were infected or mock-infected with C. trachomatis at an m.o.i. of 3 for 24 h. A, ROS production was measured with DCF and analyzed by flow cytometry. Non-fluorescent cells were gated in the first log decade, and the fluorescence intensity was proportional to the level of ROS production. B, the bar chart represents ROS production in C. trachomatis-infected MEF cells analyzed by flow cytometry under the conditions described for A. Error bars represent S.D. (n = 3). **, p < 0.01 compared with wild-type infected cells. Ctrl, control.

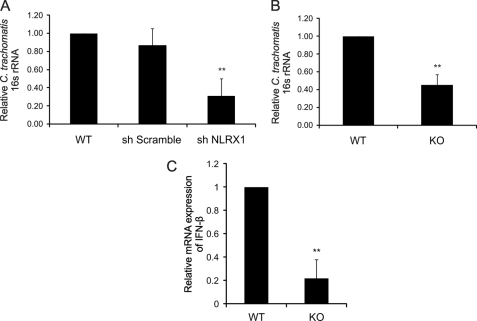

NLRX1-mediated ROS Production Is Required for Optimal Chlamydial Growth

To determine whether NLRX1-mediated ROS production during chlamydial infection plays a role in development of the chlamydial inclusion, we depleted NLRX1 in epithelial cells with NLRX1 shRNA and measured chlamydial 16 S rRNA by real-time PCR in cells infected with C. trachomatis for 24 h. In fact, C. trachomatis growth was significantly lower in epithelial cells that had a reduced expression of NLRX1 (Fig. 5A, sh NLRX1) compared with wild-type cells or cells transfected with control reagents (Fig. 5A, sh Scramble). Similarly, the complete absence of Nlrx1 expression in Nlrx1 knock-out MEFs led to a significantly reduced level of chlamydial growth, as shown by the lower chlamydial 16 S rRNA obtained from these cells compared with wild-type MEFs (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

NLRX1 expression enhances chlamydial growth. A, HeLa cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent with scrambled (sh Scramble) and NLRX1 (sh NLRX1) shRNA constructs and infected with C. trachomatis at an m.o.i. of 3 for 24 h. B and C, wild-type (WT) or Nlrx1 knock-out (KO) MEFs were infected with C. trachomatis at an m.o.i. of 3 for 24 h. Infection and IFN-β levels were quantified by real-time PCR. Total RNA was harvested for quantification of chlamydial 16 S rRNA production (A and B) or IFN-β expression (C) using real-time PCR as described under “Experimental Procedures”. Error bars represent S.D. of at least three separate experiments. **, p < 0.01 compared with infected cells treated with Lipofectamine only (A, WT) or wild-type cells (B and C).

NLRX1 has been reported to inhibit IFN-β production by interacting with the signaling adaptor MAVS (mitochondrial antiviral signaling) (6). Infection by Chlamydophila pneumoniae and Chlamydia muridarum also leads to IFN-β production. However, the production during C. pneumoniae infection requires MAVS, whereas C. muridarum infection induces IFN-β in the absence of MAVS (23, 24). We therefore considered the possibility that some of the decrease in C. trachomatis infection in Nlrx1 knock-out MEFs may be due to enhanced IFN-β production, which could indirectly inhibit chlamydial infection. However, on the contrary, we found that Nlrx1 deficiency leads to a decrease in IFN-β production (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that lower chlamydial infection in Nlrx1-deficient cells therefore leads to lower IFN-β production. In addition, our results are consistent with the possibility that IFN-β production during C. trachomatis infection is independent of MAVS, as in the case of C. muridarum infection.

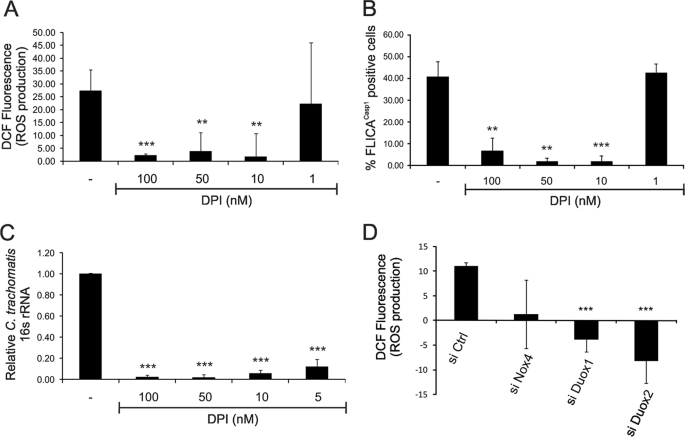

NADPH Oxidase Is Essential for ROS Production and Chlamydial Growth

To investigate whether NOX is involved in Chlamydia-induced ROS production in epithelial cells, we infected HeLa cells with C. trachomatis for 24 h and treated them 9 h post-infection with DPI, a potent and commonly used inhibitor of NOX or the NADPH oxidase family member DUOX. Inhibition of these enzymes by DPI caused a significant dose-dependent reduction in Chlamydia-induced ROS production (Fig. 6A). Importantly, we used significantly lower DPI concentrations (1–100 nm) in our study than the concentrations (10 μm) often used for NOX inhibition (25–27). As we recently showed that infection-dependent ROS production results in caspase-1 activation in epithelial cells (16), we verified that the same DPI concentrations also inhibited caspase-1 activation during chlamydial infection using FLICACasp1, a cell-permeable fluorescent reagent that can specifically bind to the active form of caspase-1 (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Chlamydia-induced ROS production requires NADPH oxidase in epithelial cells. A and B, HeLa cells were infected or mock-infected with C. trachomatis at an m.o.i. of 3 for 24 h in the presence of 0, 1, 10, 50, or 100 nm DPI (NOX and DUOX inhibitor) during the last 9 h of infection. A, ROS production was quantified by staining cells with DCF and measuring by flow cytometry. B, caspase-1 activation was quantified using fluorescent FLICACasp1 reagent and measuring by flow cytometry. C, HeLa cells were infected or mock-infected with C. trachomatis at an m.o.i. of 3 for 24 h and treated with 0, 5, 10, 50, or 100 nm DPI during the last 9 h of infection. Total RNA was harvested for quantification of chlamydial 16 S rRNA production using real-time PCR as described under “Experimental Procedures.” D, HeLa cells were transfected with control (si Ctrl), NOX4 (si Nox4), DUOX1 (si Duox1), and DUOX2 (si Duox2) siRNA constructs and infected or mock-infected with C. trachomatis at an m.o.i. of 3 for 24 h. ROS production was quantified by staining the cells with DCF and measuring ROS by flow cytometry. Error bars represent S.D. of at least three separate experiments. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 compared with infected untreated cells (A–C) or with uninfected cells treated with control siRNA (D).

We then tested whether the attenuation of ROS production caused by inhibition of NOX or DUOX can affect chlamydial growth by measuring the amount of chlamydial 16 S rRNA produced by infected cells. Indeed, treatment of C. trachomatis-infected HeLa cells with 100 nm DPI almost completely abrogated 16 S rRNA production by 24 h post-infection in a dose-dependent manner compared with controls (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that NOX and/or DUOX is a key enzyme in ROS production during chlamydial infection, which in turn is essential for caspase-1-dependent chlamydial growth.

To confirm the results with the inhibitor DPI, we also depleted, by RNA interference, the NOX/DUOX superfamily members that are expressed in HeLa cells (21, 28, 29). Thus, HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA constructs for NOX1, NOX4, DUOX1, and DUOX2 before infection with C. trachomatis. Depletion of DUOX1 and DUOX2 reduced ROS production significantly, whereas depletion of NOX4 had a smaller effect (Fig. 6D). Depletion of NOX1 had a negligible effect (data not shown), which may also be due to the previous observation that NOX1 is expressed in HeLa cells at much lower levels than NOX4 (28).

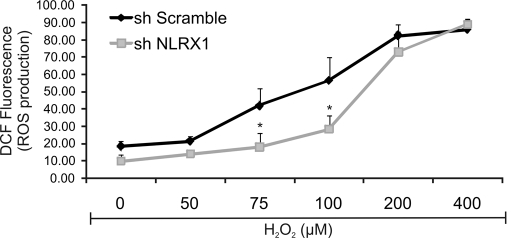

NLRX1 Can Amplify ROS Production due to Treatment with Exogenous Hydrogen Peroxide

Although NLRX1 is partially required for Chlamydia-induced ROS production, inhibition of NOX and/or DUOX by DPI led to nearly complete abrogation of ROS production following chlamydial infection. This suggests that, following infection, ROS is first generated by NOX/DUOX, and the ROS then diffuses into the mitochondria, resulting in further production of ROS in an NLRX1-dependent fashion. To test this hypothesis, we treated wild-type and NLRX1-depleted HeLa cells with different concentrations of exogenous H2O2 for 45 min and measured its induced ROS production. In fact, the addition of 75 or 100 μm H2O2 led to significantly lower ROS levels in NLRX1-depleted HeLa cells compared with control cells treated with the same concentrations of H2O2 (Fig. 7). Higher concentrations of H2O2 caused a saturated response independent of NLRX1. These results suggest that moderate levels of exogenous H2O2 can indeed stimulate mitochondrial NLRX1 to augment ROS levels in epithelial cells.

FIGURE 7.

Exogenous ROS leads to further ROS generation in an NLRX1-dependent manner. HeLa cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent with scrambled (sh Scramble) and NLRX1 (sh NLRX1) shRNA constructs, and exogenous hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was added at concentrations varying from 50 to 400 μm for 45 min. ROS production was measured with DCF and analyzed by flow cytometry. Non-fluorescent cells were gated in the first log decade, and the fluorescence intensity was proportional to the level of ROS production. Error bars represent S.D. of at least three separate experiments. *, p < 0.05, NLRX1 shRNA-treated cells compared with scrambled shRNA-treated cells.

Conclusions

We have shown previously that chlamydial infection of epithelial cells leads to K+ efflux in the host cells, which results in ROS production and NLRP3-dependent caspase-1 activation (16). In turn, chlamydial growth requires caspase-1 activation.

ROS is generated mainly by NOX on the plasma membrane and mitochondria. Other studies have reported ROS production during chlamydial infection (30, 31), but they did not identify the source of host cell-derived ROS production. In this study, we have demonstrated that ROS production during C. trachomatis infection of epithelial cells is due primarily to two sources: NOX enzymes and NLRX1. Inhibition of NOX almost completely abrogated Chlamydia-induced ROS production and the ability of Chlamydiae to maintain reproductive infection, whereas the NLR family member NLRX1 enhanced ROS production and was required for optimal chlamydial growth. Thus, NLRX1 overexpression in epithelial cells augments ROS production induced by chlamydial infection, whereas NLRX1 depletion by shRNA leads to a significant reduction in the amount of ROS produced. Using fibroblasts from Nlrx1-deficient mice, we confirmed the role of NLRX1 in the generation of ROS during chlamydial infection because Nlrx1-deficient cells exhibited a much lower level of ROS production compared with wild-type cells.

During infection, Chlamydiae inject virulence factors via the type 3 secretion apparatus into the host cell cytosol, causing efflux of K+ and production of ROS. Because the presence of endogenous NLRX1 did not overcome the inhibitory effects on ROS production of a NOX inhibitor, we propose that intracellular Chlamydiae first induce NOX-dependent production of ROS, which diffuse to the mitochondrial matrix and interact with NLRX1, thereby stimulating a further round of ROS production (Fig. 8). Moreover, we and others have shown that chlamydial infection can also stimulate the NLR family members Nod1 and Nod2 (32–35), and Nod2 has recently been found to interact with DUOX2, resulting in Nod2-dependent ROS production (21). Regardless of the source of the ROS (NOX or DUOX2), the ROS then leads to NLRP3-mediated caspase-1 activation, which is required for optimal chlamydial growth.

FIGURE 8.

NADPH oxidase and NLRX1-mediated mitochondrial production of ROS in response to C. trachomatis infection. Following infection, Chlamydiae inject virulence factors via the type 3 secretion (T3S) apparatus into the host cell cytosol, causing efflux of potassium, activation of NADPH oxidase, and production of ROS. ROS generated during chlamydial infection comes from two sources: NOX/DUOX and NLRX1. ROS then leads to NLRP3-mediated caspase-1 (Casp1) activation, which is required for optimal chlamydial growth. ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein.

Chlamydia is an astute pathogen because it can evade the immune system in many ways and modulate host cell signaling pathways in a well orchestrated and timely manner (14, 36–40). Paradoxically, C. trachomatis also turns one of the host cell's own defense mechanisms, ROS production, to its own advantage, providing one further example of this pathogen's ability to subvert the host immune response.

Footnotes

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- NOX

- NADPH oxidase

- DUOX

- dual oxidase

- NLR

- Nod-like receptor

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- DPI

- diphenyliodonium chloride

- m.o.i.

- multiplicity of infection

- DCF

- 5(6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate acetyl ester.

REFERENCES

- 1.Woo H. A., Yim S. H., Shin D. H., Kang D., Yu D. Y., Rhee S. G. (2010) Cell 140, 517–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamanaka R. B., Chandel N. S. (2009) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21, 894–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landriscina M., Maddalena F., Laudiero G., Esposito F. (2009) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 2701–2716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novo E., Parola M. (2008) Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 1, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tattoli I., Carneiro L. A., Jéhanno M., Magalhaes J. G., Shu Y., Philpott D. J., Arnoult D., Girardin S. E. (2008) EMBO Rep. 9, 293–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore C. B., Bergstralh D. T., Duncan J. A., Lei Y., Morrison T. E., Zimmermann A. G., Accavitti-Loper M. A., Madden V. J., Sun L., Ye Z., Lich J. D., Heise M. T., Chen Z., Ting J. P. (2008) Nature 451, 573–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnoult D., Soares F., Tattoli I., Castanier C., Philpott D. J., Girardin S. E. (2009) J. Cell Sci. 122, 3161–3168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerbase A. C., Rowley J. T., Mertens T. E. (1998) Lancet 351, 2–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller W. C., Ford C. A., Morris M., Handcock M. S., Schmitz J. L., Hobbs M. M., Cohen M. S., Harris K. M., Udry J. R. (2004) JAMA 291, 2229–2236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belland R., Ojcius D. M., Byrne G. I. (2004) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 530–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyrick P. B. (2000) Cell. Microbiol. 2, 275–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bavoil P. M., Hsia R., Ojcius D. M. (2000) Microbiology 146, 2723–2731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rockey D. D., Scidmore M. A., Bannantine J. P., Brown W. J. (2002) Microbes Infect. 4, 333–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carabeo R. A., Mead D. J., Hackstadt T. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 6771–6776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flannagan R. S., Cosío G., Grinstein S. (2009) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 355–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdul-Sater A. A., Koo E., Häcker G., Ojcius D. M. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 26789–26796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shao W., Yeretssian G., Doiron K., Hussain S. N., Saleh M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 36321–36329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurcel L., Abrami L., Girardin S., Tschopp J., van der Goot F. G. (2006) Cell 126, 1135–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ojcius D. M., Degani H., Mispelter J., Dautry-Varsat A. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 7052–7058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perfettini J. L., Ojcius D. M., Andrews C. W., Jr., Korsmeyer S. J., Rank R. G., Darville T. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 9496–9502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipinski S., Till A., Sina C., Arlt A., Grasberger H., Schreiber S., Rosenstiel P. (2009) J. Cell Sci. 122, 3522–3530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ojcius D. M., Niedergang F., Subtil A., Hellio R., Dautry-Varsat A. (1996) Res. Immunol. 147, 175–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prantner D., Darville T., Nagarajan U. M. (2010) J. Immunol. 184, 2551–2560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buss C., Opitz B., Hocke A. C., Lippmann J., van Laak V., Hippenstiel S., Krüll M., Suttorp N., Eitel J. (2010) J. Immunol. 184, 3072–3078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shinohara M., Adachi Y., Mitsushita J., Kuwabara M., Nagasawa A., Harada S., Furuta S., Zhang Y., Seheli K., Miyazaki H., Kamata T. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 4481–4488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou R., Tardivel A., Thorens B., Choi I., Tschopp J. (2010) Nat. Immunol. 11, 136–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papaiahgari S., Kleeberger S. R., Cho H. Y., Kalvakolanu D. V., Reddy S. P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 42302–42312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng G., Cao Z., Xu X., van Meir E. G., Lambeth J. D. (2001) Gene 269, 131–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeya R., Ueno N., Sumimoto H. (2006) Methods Enzymol. 406, 456–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azenabor A. A., Yang S., Job G., Adedokun O. O. (2005) Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 194, 91–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kälvegren H., Bylin H., Leanderson P., Richter A., Grenegård M., Bengtsson T. (2005) Thromb. Haemost. 94, 327–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welter-Stahl L., Ojcius D. M., Viala J., Girardin S., Liu W., Delarbre C., Philpott D., Kelly K. A., Darville T. (2006) Cell. Microbiol. 8, 1047–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Opitz B., Förster S., Hocke A. C., Maass M., Schmeck B., Hippenstiel S., Suttorp N., Krüll M. (2005) Circ. Res. 96, 319–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buchholz K. R., Stephens R. S. (2008) Infect. Immun. 76, 3150–3155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Derbigny W. A., Kerr M. S., Johnson R. M. (2005) J. Immunol. 175, 6065–6075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su H., McClarty G., Dong F., Hatch G. M., Pan Z. K., Zhong G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 9409–9416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verbeke P., Welter-Stahl L., Ying S., Hansen J., Häcker G., Darville T., Ojcius D. M. (2006) PLoS Pathog. 2, e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stephens R. S. (2003) Trends Microbiol. 11, 44–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scidmore M. A., Hackstadt T. (2001) Mol. Microbiol. 39, 1638–1650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McClarty G. (1994) Trends Microbiol. 2, 157–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]