Abstract

γ-Protocadherins (PCDH-γ) regulate neuronal survival in the vertebrate central nervous system. The molecular mechanisms of how PCDH-γ mediates this function are still not understood. In this study, we show that through their common cytoplasmic domain, different PCDH-γ isoforms interact with an intracellular adaptor protein named PDCD10 (programmed cell death 10). PDCD10 is also known as CCM3, a causative genetic defect for cerebral cavernous malformations in humans. Using RNAi-mediated knockdown, we demonstrate that PDCD10 is required for the occurrence of apoptosis upon PCDH-γ depletion in developing chicken spinal neurons. Moreover, overexpression of PDCD10 is sufficient to induce neuronal apoptosis. Taken together, our data reveal a novel function for PDCD10/CCM3, acting as a critical regulator of neuronal survival during development.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Cell Adhesion, Cell Death, Neurodevelopment, Protein-Protein Interactions, Signal Transduction

Introduction

Apoptosis is essential in controlling the size of distinct neuron populations in the nervous system (1, 2). During development, 50% or more neurons undergo apoptosis to ensure the appropriate partnership of pre- and postsynaptic target cells (1, 3–5). It is well known that target-derived cues such as trophic factors and synaptic activity are critical for the survival of different neuronal populations (6–9). Emerging evidence shows that clustered protocadherins (PCDH)3 also play an important role in the regulation of neuronal survival (10–13).

PCDH proteins are vertebrate-specific members of the cadherin superfamily, which share significant homology in extracellular domains with cadherins but have distinct cytoplasmic domains (14–17). Pcdh genes have a unique genomic organization in which nearly 60 Pcdh genes are tandem-arrayed in three clusters (Pcdh-α, Pcdh-β, and Pcdh-γ) on a single chromosome (16). Cell-specific promoter activation and allelic exclusion at the Pcdh locus generate distinct combinatorial expression patterns among individual neurons (18–21). PCDH proteins have been shown to mediate homophilic cell-cell adhesion, and they are enriched at synapses in the brain (15, 22–24). Furthermore, genetic analyses in model systems highlight the importance of PCDH function in the nervous system. These studies reveal that PCDH proteins are required for neuronal survival and synaptic connectivity in neuronal subpopulations. Deletion of Pcdh-γ in mice leads to an increased apoptosis of spinal interneurons and retina ganglion cells and knockdown of Pcdh-α in zebrafish causes massive neuronal loss during neurogenesis (10–13). Thus, clustered PCDH appears to be critical survival factors for certain neuronal populations during development. Independently from the role for survival, PCDH plays a role in the maintenance of synaptic connectivity in several neural circuits. For example, in Pcdh-γ mutant mice, spinal interneurons and hypothalamic neurons exhibit abnormal synaptic connectivity (25, 26). Similarly, olfactory sensory neurons and serotonergic neurons have been shown to have abnormal axon projections in Pcdh-α mutant mice (27, 28). Collectively, these data suggest that PCDH can control neural circuit formation by affecting neuron survival and synapse maturation.

Despite the importance of PCDH, the intracellular signaling pathways associated with PCDH are poorly understood. As an important step to understand the molecular action of PCDH, we recently used two complementary approaches to systematically identify downstream proteins important for PCDH function in the nervous system. First, we combined affinity purification and mass spectrometry to complete a systematic proteomic analysis of PCDH-γ-associated protein complexes (29). From this study, we identified a list of 154 nonredundant proteins that include nearly 30 members of clustered PCDH-α, -β, and -γ families and additionally >120 putative PCDH-associated proteins. Among these identified proteins, PCDH-α, -β, and -γ proteins form large core complexes, whereas the majority of non-PCDH proteins overlap with the proteomic profile of postsynaptic density preparations. Thus, proteomic data provide direct evidence that PCDH interacts with synaptic components at the molecular level. In parallel, we used a CytoTrap yeast two-hybrid approach to identify proteins that directly interact with the intracellular domain of PCDH-γ . This search identified 19 candidate proteins. Among these candidates, we recently found that PCDH-γ and PCDH-α bind to and inhibit PYK2 kinase activity in the brain and that increased PYK2 activity contributes to apoptosis in PCDH-γ-deficient neurons (30).

In this study, we continued the characterization of the PCDH downstream pathway in regulating neuronal survival, by focusing on a newly identified PCDH-γ-interacting protein- PDCD10 (programmed cell death protein 10). We show that PCDH-γ specifically interacts with PDCD10. PDCD10, also known as CCM3 (cerebral cavernous malformation protein 3) (31), is an intracellular adaptor protein that was found to be up-regulated during apoptosis (32). Using shRNA-mediated knockdown in the chicken spinal cord, we show that PDCD10 is a critical apoptosis regulator upon depletion of PCDH-γ. Moreover, PDCD10 overexpression is sufficient to induce neuronal death. Thus, our studies reveal an important function of PDCD10/CCM3 in the regulation of apoptosis during vertebrate neural development.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Construction

All cDNA constructs for CytoTrap two-hybrid system were cloned as described previously (30). Various expression vectors for Pcdh-γ, N-cadherin, E-cadherin, Pcdh-α, Pyk2, Ccm2/Osm, and Ccm3/Pdcd10 were constructed by cloning restriction enzyme-digested or PCR-amplified DNA fragments into pGEX.KG, pET28a, pcDNA3, and pPB-CAG. The original cDNAs were obtained from IMAGE or FANTOM clone collections and tagged with different epitope tags, including FLAG, 3×FLAG, 9E10-MYC, 6×MYC, and V5. PCDH-γ sh1 plasmids were constructed as described previously (29). To construct the CMV-Ff-Pdcd10 reporter, a 600-bp cDNA fragment corresponding to the chicken Pdcd10 was cloned into a CMV-Ff vector. Annealed double-strand oligos encoding PDCD10 shRNAs were cloned into a pPB-H1 vector as described previously (33). For PDCD10 sh130, primers 5′-TTT GAA CGA GGA GAA AGA AGA AAC GTT AAT TAC GTT TCT TCT TTC TCC TCG TTC TTT TTC-3′ and 5′-TCG AGA AAA AGA ACG AGG AGA AAG AAG AAA CGT AAT TAA CGT TTC TTC TTT CTC CTC GTT-3′ were used. For PDCD10 sh192, primers 5′-TTT GTG CCA ACC GAC TAA TTC ATC TTA ATT AGA TGA ATT AGT CGG TTG GCA CTT TTT C-3′ and 5′-TCG AGA AAA AGT GCC AAC CGA CTA ATT CAT CTA ATT AAG ATG AAT TAG TCG GTT GGC A-3′ were used. All cDNA and shRNA constructions were verified by complete or partial sequencing.

Cell Culture and Transfection

Human kidney HEK293T and chicken fibroblast DF-1 cells originally were purchased from ATCC and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used for HEK293T cells and Superfect (Qiagen) for DF-1 cells.

Chicken Spinal Cord Electroporation

Fertilized white leghorn chicken eggs were incubated at 38 °C to Hamberger and Hamilton (HH) stage 12. Plasmids were mixed with Fast Green dye and injected into the central canal of the neural tube; thoracic and lumbar segments of the chicken spinal cords were electroporated as described previously (34). Embryos were incubated for 24 h before the spinal cords were dissected and harvested for analysis.

Primary Neuron Culture

The developing chicken spinal cords were isolated from HH stage 28 chicken embryos and digested with papain for 30 min. The digested spinal cords were triturated in to single cell suspension. After removing papain with a low speed centrifugation, neurons were resuspended in Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum and plated at a density of 3.6 × 104 on (0.002%) poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips. 12 h later, attached neurons were switched to Neurobasal medium with B27 supplement, and cultured in vitro for 11 days prior to immune staining. The mouse hippocampal neurons were isolated and cultured as described previously (35).

Pulldown and Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP)

Various bacterially expressed recombinant proteins including N-cadherin-GST (N-CAD-GST), E-cadherin-GST (E-CAD-GST), PCDH-γ-C125-GST, PCDH-γ-C115-GST, PCDH-γ-C45-GST, PCDH-γ-C70-GST, PCDH-α-GST, GST alone, and His-PDCD10, were used in this study. Protein purification and pulldown assays were carried out as described previously (30).

For co-IPs in cultured cells, HEK293T cells were co-transfected with the expression vectors for 3×FLAG-PDCD10 and varied isoforms of PCDH and solubilized in a lysis buffer containing 25 mm HEPES, pH 7.6, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 1% Triton, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm pnenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and Roche Applied Science protease inhibitors. Aliquots of anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma) were incubated with cell lysates for the isolation of protein complexes. For co-IP using chicken spinal cord samples, FLAG-PDCD10 was electroporated into the developing chicken spinal cord at HH stage 12. 24 h after electroporation, the transfected spinal cords were dissected, lysed, and subjected to co-IP analysis. The co-IP analysis of PCDH-γ with PDCD10 using Pcdh-γfusg knock-in mice was performed as described previously (30).

Immunocytochemistry and Immunohistochemistry

Transfected cells or tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C for 2 h and washed extensively in PBS. For immunohistochemistry, samples were cryo-protected in 30% sucrose, mounted in optimal cutting temperature mixture. 12-μm cryostat sections were used for indirect immunofluorescence staining following standard protocols (33).

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used in this study: mouse anti-FLAG M2 (1:5000, Sigma), rabbit anti-PDCD10 polyclonal (1:500 for Western blotting and 1:200 for immunocytochemistry, ProteinTech Group, Inc.), 9E10 anti-MYC (1:1,000 DSHB), rabbit anti-GST (1:10,000, Novagen), rat anti-GFP (1:10,000, MBL), anti-Sox2 (AB15830) stem cell marker (1: 1,000, Abcam), E7 anti-β-tubulin (1:500, DSHB), anti-neuronal class III β-tubulin (TUJ1) monoclonal (1:1,000, Covance), mouse anti-V5 (1:2,000, Invitrogen), SMI-311 pan-neuronal neurofilament maker (1:2,000, Covance), Alexa Fluor 488 phalloidin (1:1,000, Invitrogen) and secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). The rabbit anti-PCDH-γ and rabbit anti-active chicken caspase-3 (CASP-3) antibodies were generated previously and characterized (10, 29). The rabbit anti-PDCD10 was generated using GST-tagged PDCD10 by Covance in this study, and the specificity was confirmed by Western blot analysis on PDCD10-overexpressing and knockdown chicken spinal cord lysates.

Statistic Analysis

For analysis of apoptotic cells in chicken spinal cords, active caspase-3 positive neurons on every fourth consecutive spinal cord section were counted. The death index (DI) is calculated by subtracting the number of caspase-3-positive cells on the nonelectroporated side from that of the electroporated side. The averages of three DIs from individual spinal cords were plotted on a scattered plot. The data in Figs. 3–8 were subjected to two-tailed unpaired Student t tests. The calculated p value for each experiment is shown in each figure.

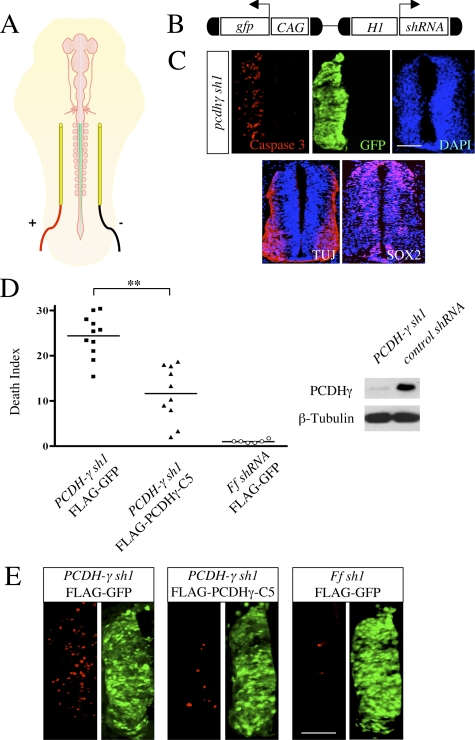

FIGURE 3.

The role of PCDH-γ in regulating neuronal survival in the chicken spinal cord. A, schematic illustration of the in ovo electroporation procedure to introduce expression vectors into the developing chicken spinal cord. The green line indicates injected DNA mixture with Fast Green dye filling the central cavity of the spinal cord. Electrical pulses are applied bilaterally to introduce DNA into one side of the spinal cord (+). B, a diagram showing the shRNA-expressing vector. The expression of short hairpin RNA is under the control of the H1 promoter, and the ubiquitous CAG promoter-driven GFP reporter is used to mark transfected cells. C, PCDH-γ sh1 induces apoptosis in the developing chicken spinal cord. Shown is a transverse section from PCDH-γ sh1-expressing chicken spinal cord with triple staining of active caspase-3 (red), GFP (green), and DAPI (blue). Sox-2 and TUJ were used to identify both progenitors and postmitotic neurons in the neural tube at the stage of analysis. D and E, PCDH-γ sh1 induces neuronal death, and this apoptosis is rescued by the overexpression of C5 isoform of PCDH-γ. D, the quantitative analysis of the apoptosis in the PCDH-γ knockdown chicken spinal cords. The indicated shRNA and protein expression vectors were electroporated into the chicken spinal cords, and samples were analyzed as described in C. The averages of three DIs from individual embryos were plotted in D. The results were subjected to t test. **, p ≪ 0.01. The statistically significant difference between FLAG-PCDH-γ-C5 rescued samples and FLAG-GFP controls demonstrates that PCDH-γ knockdown-induced apoptosis can be partially rescued by overexpression of a single PCDH-γ isoform. The Western blot shows an effective knockdown of the PCDH-γ proteins by PCDH-γ sh1 (right). E, representative images of active caspase-3 (red) and GFP (green) staining from the experiments shown in D. Bars, 100 μm.

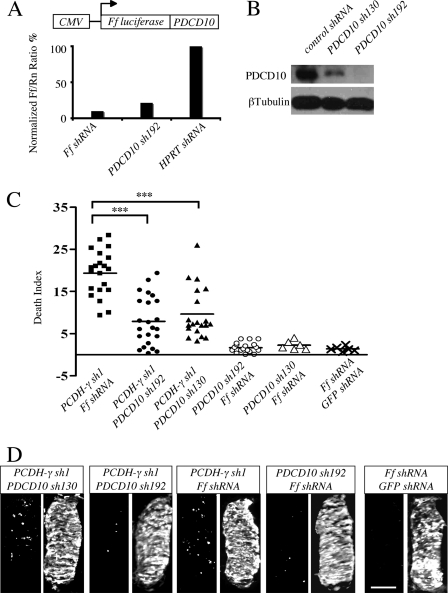

FIGURE 4.

PDCD10/CCM3 is a key mediator of apoptosis downstream of PCDH-γ. A, the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay was used to measure the relative knockdown efficiency of a PDCD10 shRNA. A diagram showing that a chicken PDCD10 cDNA fragment was fused with firefly luciferase (Ff) as the target sequence for shRNA. Renilla luciferase (Rn) was used to normalize the transfection efficiency. Ff and HPRT shRNAs served as positive and negative controls respectively. B, a Western blot showed that PDCD10 shRNAs efficiently reduced endogenous PDCD10 protein levels in the transfected chicken spinal cords. C and D, knockdown of PDCD10 by shRNAs attenuated the apoptotic phenotype induced by PCDH-γ depletion. Simultaneous knockdown of both PDCD10 and PCDH-γ reduced the number of apoptotic cells, whereas co-expression of control Ff-shRNA with PCDH-γ shRNA did not. Knockdown of PDCD10 alone appeared to have no effect on apoptosis. Two independent shRNAs against PDCD10 were used in the experiments to ensure the specificity and reduce the possibility of off-target effects. C, quantitative analysis of apoptosis in PCDH-γ and PDCD10 double knockdown chicken spinal cords. DIs were plotted as described in Fig. 3. The results were subjected to t tests. ***, p < 0.0001. D, representative images of C. Bars, 100 μm.

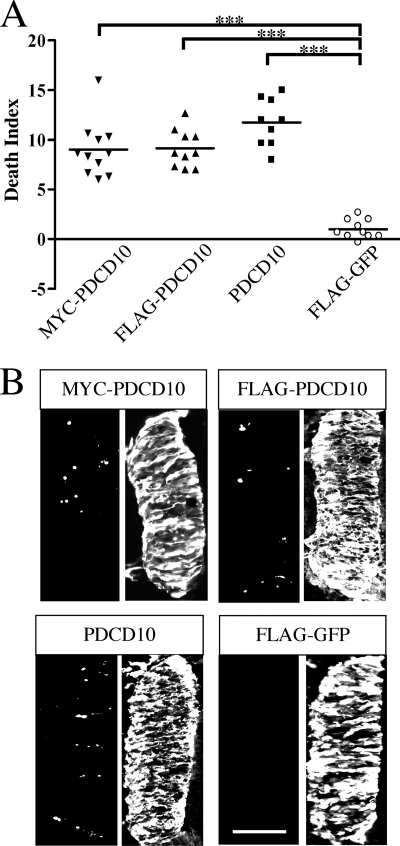

FIGURE 5.

PDCD10 overexpression is sufficient to induce neuronal apoptosis. Overexpression of different tagged and non-tagged PDCD10 proteins but not GFP induces apoptosis in the spinal cord neurons. A, various tagged and non-tagged forms of PDCD10 were electroporated into chicken spinal cords, and DIs were quantified and plotted. FLAG-tagged destabilized GFP was used as a negative control. ***, p < 0.0001. B, representative images of A. The active caspase-3 stained cells are shown to the left of each panel. MYC, FLAG, PDCD10, and GFP are shown to the right of each panel. Bars, 100 μm.

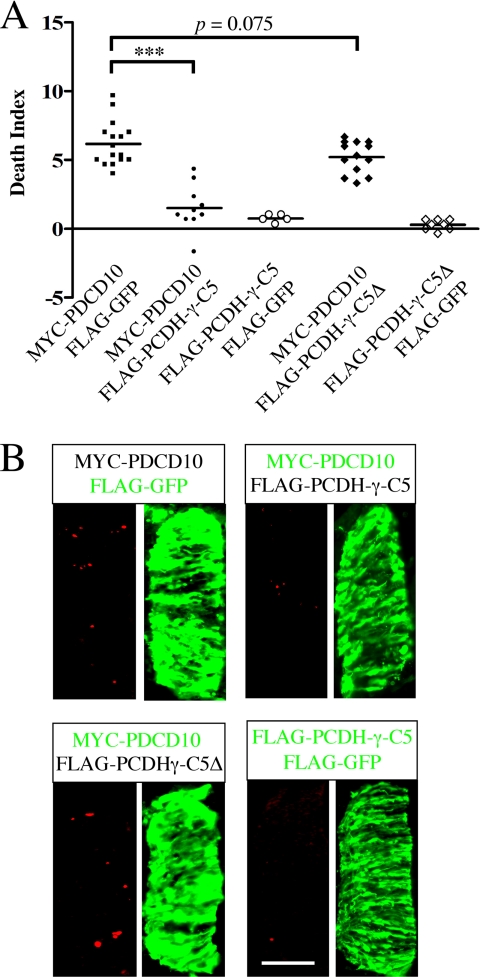

FIGURE 6.

Overexpression of PCDH-γ rescues PDCD10-induced neuronal apoptosis. A and B, overexpression of the C5 isoform of PCDH-γ rescued the apoptotic phenotype caused by PDCD10, whereas as controls, overexpression of either GFP or PCDH-γ-C5Δ failed to rescue. A, MYC-PDCD10 was co-electroporated and expressed with FLAG-PCDH-γ, FLAG-PCDH-γ-C5Δ, or control FLAG-GFP in the chicken spinal cord. FLAG-PCDH-γ-C5Δ encodes a PCDH-γ-C5 lack of the shared cytoplasmic domain. DIs were quantified and plotted in the graph. ***, p < 0.0001. n.s., no significant difference. B, representative images of A are shown. Active caspase-3 staining is shown in red, and anti-FLAG or anti-MYC staining is shown in green. Bar, 100 μm.

FIGURE 7.

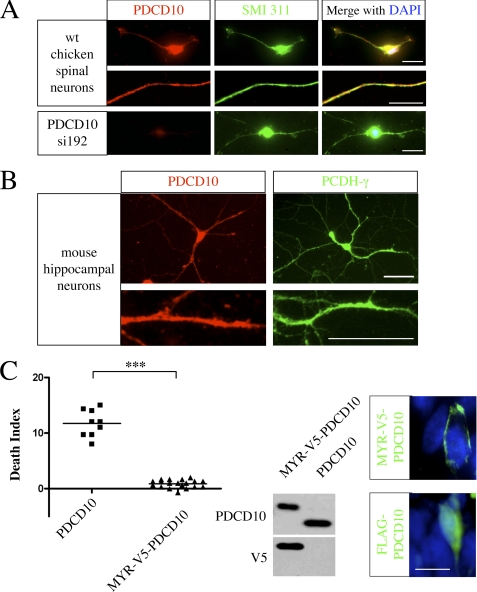

The subcellular localization of PDCD10 and its role in apoptosis. A, the endogenous PDCD10 is localized in both soma and neuronal processes in cultured spinal cord neurons. HH stage 28 chicken spinal neurons were cultured in vitro for 11 days and stained with anti-PDCD10 antibody and SMI311 anti-neurofilament antibody (top). The specificity of PDCD10 staining was demonstrated by significantly reduced signals in cultured neurons that were electroporated with PDCD10 sh192 (bottom). Bars, 50 μm. B, both endogenous PDCD10 and PCDH-γ localize in the neuronal processes of cultured mouse hippocampal neurons. Mouse hippocampal neurons from embryonic day 18 embryos were cultured in vitro for 14 days and stained with anti-PDCD10 antibody and anti-PCDH-γ antibody. Bars, 50 μm. C, overexpression of membrane-bound PDCD10 did not induce neuronal apoptosis. Left panel, quantitative analysis revealed no significant increase of apoptosis upon expression of Myr-V5-PDCD10 in the chicken spinal cord. The DIs were quantified and plotted in the graph as described in Fig. 3. ***, p < 0.0001. Middle panel, Western blots showed that Myr-V5-PDCD10 and PDCD10 proteins were expressed at a similar level. Right panel, Myr-V5-PDCD10 is membrane-bound (top, V5 in green), and FLAG-PDCD10 is distributed throughout the cell (bottom, FLAG in green). Bar, 10 μm.

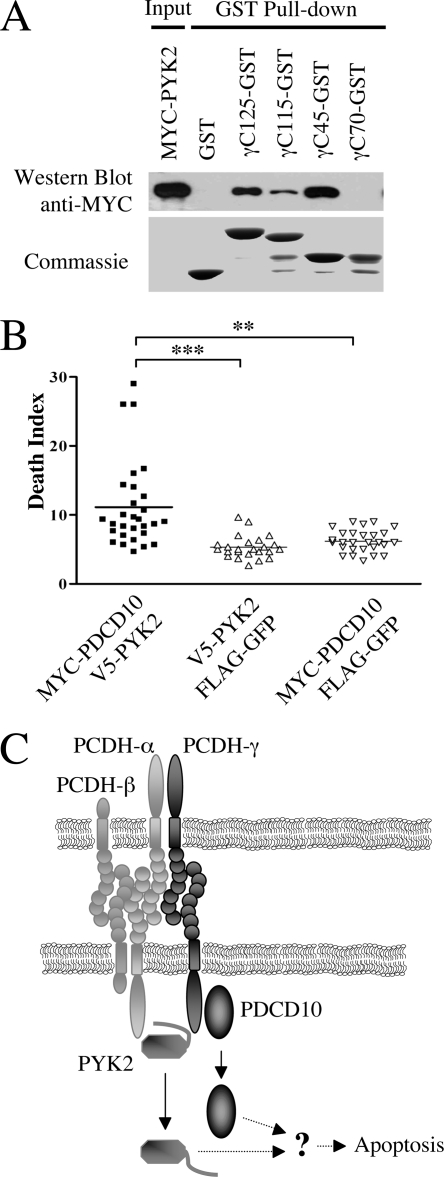

FIGURE 8.

PDCD10 cooperates with PYK2 in regulating apoptosis. A, GST pulldown assay showing that MYC-tagged PYK2 interacts with the γ-C45 region of PCDH-γ. The definitions of γ-C fragments are as described in the legend to Fig. 1. B, PDCD10 and PYK2 have an additive effect in inducing neuronal apoptosis. MYC-PDCD10 and V5-PYK2 expression vectors were co-electroportated (at a ratio of 1:1) or electroporated with control plasmid (FLAG-GFP) as indicated. DIs of each combination were quantified and plotted on the graph. Coexpression of PDCD10 and PYK2 induced significantly more cell death compared with PDCD10 or PYK2 alone. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.0001. C, a working hypothesis to illustrate the role of PCDH-γ in regulating neuronal survival is shown. In this model, PCDH-γ promotes neuronal survival by sequestering PDCD10 and inhibiting PYK2.

RESULTS

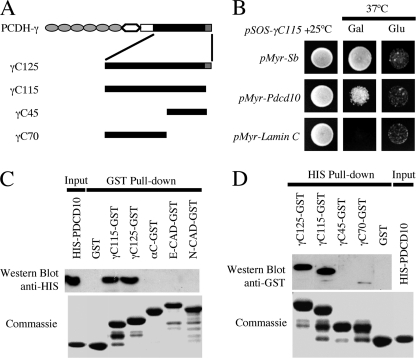

PCDH-γ Interacts with PDCD10/CCM3 in Vitro

To identify the intracellular signaling components of PCDH-γ, we recently performed a CytoTrap yeast two-hybrid screen using the shared intracellular domain of PCDH-γ (30). In addition to the previously described PYK2, we identified an additional positive clone that encodes an in-frame fusion between the myristoylation signal and full-length PDCD10 (programmed cell death 10). Mutations in PDCD10 are associated with a human genetic disorder known as CCM (cerebral cavernous malformation). PDCD10 is therefore also known as CCM3. As shown in Fig. 1, SOS-γ-C115 specifically interacted with Myr-PDCD10, and this interaction rescued the temperature-sensitive growth defect of cdc25H yeast at 37 °C (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

PCDH-γ interacts with PDCD10 in vitro. A, schematics of the domain structures of PCDH-γ constructs. γ-C125, complete shared cytoplasmic domain (amino acids 1–125); γ-C115, deletion of the poly-lysine tail at the C-terminal (amino acids 1–115); γ-C45, C-terminal region (amino acids 71–115); and γ-C70, N-terminal region (amino acids 1–70). B, γ-C115 interacts with PDCD10 in the CytoTrap yeast two-hybrid system. Cotransformation of the bait pSOS-γ-C115 with pMyr-Pdcd10 into the cdc25H strain showed that pMyr-Pdcd10 interacted with pSOS-γ-C115 and rescued yeast growth defect at a restricted temperature of 37 °C. pMyr-SB and pMyr-lamin C served as positive and negative controls, respectively. C, GST pulldown assays showed that immobilized PCDH-γ-C125-GST and PCDH-γ-C115-GST directly interacted with purified His-tagged PDCD10. Note that PCDH-α-GST, N-CAD-GST, E-CAD-GST, or GST alone did not interact with His-PDCD10. Shown are anti-His6 Western blots detecting PDCD10 proteins (top panel) and Coomassie staining of the input proteins (bottom). D, His pulldown assay confirmed the direct physical interactions between PCDH-γ-C and PDCD10. Shown are anti-GST Western blots detecting varies truncated PCDH-γ proteins (top panel) and Coomassie staining of the input proteins (bottom).

To determine whether PCDH-γ-C can directly bind to PDCD10, we purified bacterially expressed GST-γ-C fusion proteins and His-tagged PDCD10. Both full-length GST-γ-C125 and the poly-lysine deletion GST-γ-C115, but not GST alone, interacted with purified His-tagged PDCD10 in the GST pulldown assay (Fig. 1C), demonstrating that the shared cytoplasmic domain of PCDH-γ directly interacts with PDCD10. To further test the specificity of this interaction, we purified GST fusion proteins with the cytoplasmic domains of several other cadherin superfamily members, including N-cadherin (N-CAD), E-cadherin (E-CAD) and PCDH-α. Unlike the cytoplasmic domain of PCDH-γ, GST pulldown assays showed that cytoplasmic domains from other cadherin-like molecules did not interact with PDCD10/CCM3 (Fig. 1C). To map which region of PCDH-γ-C interacts with PDCD10, we divided PCDH-γ-C into two regions: a C-terminal region (PCDH-γ-C45) that consisted of the last 45 amino acids (amino acids 71–125) and a N-terminal region (PCDH-γ-C70) that consisted of the first 70 amino acids (amino acids 1–70). Using purified GST-fusion proteins with PCDH-γ-C fragments, we found that PDCD10 weakly interacted with PCDH-γ-C70 but not PCDH-γ-C45 (Fig. 1D). Taken together, our data show that PDCD10 specifically and directly interacts with PCDH-γ but not with other cadherin-like proteins.

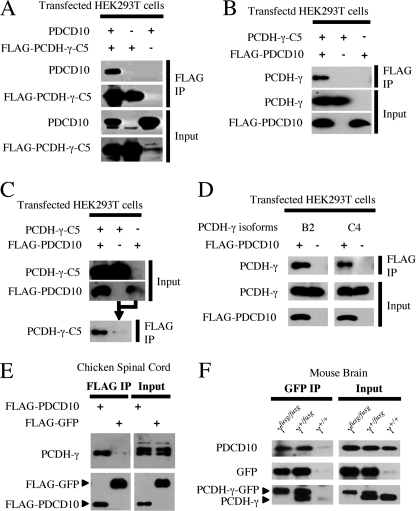

PCDH-γ Interacts with PDCD10 in Vivo

To demonstrate the interaction between PCDH-γ and PDCD10 in mammalian cells, we transfected HEK293T cells with the FLAG-tagged C5 isoform of PCDH-γ and PDCD10. Co-IP showed that PDCD10 was associated with PCDH-γ-C5 (Fig. 2A). A reciprocal co-IP with FLAG-PDCD10 confirmed this interaction (Fig. 2B). As a control, using mixed lysates from individually transfected cells, co-IP failed to detect significant interaction between PCDH-γ-C5 and PDCD10 (Fig. 2C), suggesting that the association of PDCD10 with PCDH-γ detected under the condition in Fig. 2, A and B, reflected a biologically relevant protein-protein interaction before cell lysis.

FIGURE 2.

PCDH-γ interacts with PDCD10 in vivo. A–C, full-length PCDH-γ-C5 interacts with PDCD10 in HEK293T cells. Different combinations of PDCD10 and full-length PCDH-γ-C5 isoform expression plasmids were transfected into HEK293T cells. The input and co-immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by Western blots. A, anti-FLAG co-IP was performed to isolate the PCDH-γ-C5-associated protein complex (top). FLAG-PCDH-γ-C5 and PDCD10 were associated when co-expressed in HEK293T cells. B, a reciprocal co-IP was performed to isolate the PDCD10-associated protein complex (top). Shown is the association of FLAG-PDCD10 with PCDH-γ-C5. C, as a control, the FLAG-PDCD10 and PCDH-γ-C5 were expressed individually and then mixed together as cell lysates. The interaction was barely detectable when the two proteins were not co-expressed in the cells. D, PDCD10 interacts with other isoforms of the full-length PCDH-γ. B2 and C4 expression plasmids were transfected into HEK293T with or without FlAG-PDCD10 as indicated. Co-IP assays were performed as described in A. PDCD10 was associated with both B2 and C4 isoforms of PCDH-γ in HEK293T cells. E, PDCD10 interacts with endogenous PCDH-γ in vivo. The FLAG-PDCD10 expression plasmid was electroporated into the developing chicken spinal cord at HH stage 12. Endogenous PCDH-γ was co-immunoprecipitated with FLAG-PDCD10 protein but not FLAG-GFP. F, PDCD10 interacts with PCDH-γ in the mouse brain. Pcdh-γfusg knock-in mouse brains were harvested at postnatal day 6 and PCDH-γ complexes were affinity-purified using an anti-GFP antibody. Note that in both Pcdh-γ+/fusg and Pcdh-γfusg/fusg brain samples, endogenous PCDH-γ-GFP fusion proteins were in complex with endogenous PDCD10. PCDH-γ proteins were associated with PCDH-γ-GFP fusion proteins in Pcdh-γ+/fusg mouse brain because PCDH-γ proteins form an oligomer in the brain (lower panel).

The PCDH-γ family consists of 22 isoforms that have distinct and related extracellular domains but share a common cytoplasmic domain. We further tested the interaction between PDCD-10 and two additional isoforms of PCDH-γ and found that PDCD10 also interacted with B2 and C4 isoforms (Fig. 2D). To determine whether PDCD10 and PCDH-γ interact in neurons, we chose the developing chicken spinal cord as an experimental system. Upon electroporation of FLAG-PDCD10 into the chicken spinal cord, endogenous chicken PCDH-γ proteins were found to be associated with tagged PDCD10 (Fig. 2E). Lastly, we tested whether endogenous levels of PCDH-γ and PDCD10 interact in vivo. To do so, we utilized a previously established Pcdh-γfusg knock-in mouse line, in which functional PCDH-γ-GFP proteins are expressed at the endogenous level (10, 29, 30). From postnatal day 6 mouse brain lysates, PDCD10 was coimmunoprecipitated with anti-GFP antibodies from both homozygous and heterozygous Pcdh-γfusg mice (Fig. 2F). Therefore, our data demonstrate that different PCDH-γ isoforms interact with PDCD10/CCM3 in vivo.

Role of PCDH-γ in Regulating Neuronal Survival in Developing Chicken Spinal Cord

Genetic studies in mice show that PCDH-γ is required for neuronal survival during development (10–12). In this study, we employed an RNAi transgenic approach in the developing chicken spinal cord to recapitulate the loss-of-function apoptotic phenotype seen in Pcdh-γ null mice (Fig. 3). At HH stage 12 (around embryonic day 2), we used in ovo electroporation to introduce a PiggyBac (PB) transgene expressing an shRNA against the common constant exons shared by all PCDH-γ isoforms (Fig. 3A). In this transgene, shRNA expression is under the control of H1 promoter and GFP is under the control of CAG promoter for monitoring the electroporated cells (Fig. 3B). 24 h (around HH stage 18–20) after introducing a transgene into the developing neural tube, we used an anti-active-caspase-3 immunostaining to detect apoptotic cells (Fig. 3C). Because normal developmental apoptosis could occur at this stage of development, we define a DI by subtracting the number of apoptotic cells in the non-electroporated side of spinal cord from the number in the electroporated side. At the time of analysis, the neural tube consists of a majority of neural progenitor cells (Sox2-positive) and a minority of mature neurons (TUJ-positive) (Fig. 3C). Based on their different soma locations, we estimate that the apoptotic cells we detected proportionally include both cell types. Quantitative analysis of cell DI showed that PCDH-γ shRNA expression significantly induces neuronal apoptosis in the chicken spinal cord (Fig. 3, D and E, and supplemental Fig. S1, comparing PCDH-γ shRNA and Ff shRNA). Western blot analysis confirmed that PCDH-γ shRNA effectively reduced PCDH-γ protein level (Fig. 3D, right). To confirm the specificity of RNAi and exclude the off-target effect, we performed a genetic rescue experiment with a mouse PCDH-γ-C5 isoform that is resistant to chicken PCDH-γ shRNA. Overexpression of mouse PCDH-γ-C5 partially rescued the apoptotic phenotype, demonstrating the specificity of this assay (Fig. 3, D and E, for representative images and supplemental Fig. S1 for complete images for neural tubes). Thus, application of RNAi in the developing chicken spinal cord provides a robust and efficient system to investigate the function of PCDH-γ downstream effectors in regulating neuronal apoptosis.

PDCD10/CCM3 Is a Key Mediator of Apoptosis Downstream of PCDH-γ

PDCD10 was first identified by differential display as a cDNA up-regulated in the cells undergoing apoptosis (32). For this reason, PDCD10 has been suggested to play a role in regulating apoptosis. The physical interaction of PDCD10 with PCDH-γ led us to investigate whether PDCD10 is required for PCDH-γ function in neuronal survival. We first designed and screened the efficacy of several shRNAs against chicken PDCD10 using a firefly (Ff) luciferase reporter containing the chicken PDCD10 coding sequence in its 3′-UTR (Fig. 4A). Dual-Luciferase assay showed that PDCD10 sh192 efficiently reduced Ff activity compared with a negative control (hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase shRNA). Western blot analysis confirmed that two PDCD10 shRNAs (sh130 and sh192) efficiently knocked down PDCD10 protein levels 24 h after electroporation into chicken spinal cord (Fig. 4B). We then simultaneously introduced both shRNAs against PCDH-γ and PDCD10 to examine whether PDCD10 knockdown is able to attenuate the apoptosis upon depletion of PCDH-γ by RNAi. Quantitative analysis of active caspase-3-positive neurons in the chicken spinal cord showed that knockdown of PDCD10 by two different shRNAs (sh192 and sh130) decreased the numbers of apoptotic cells induced by PCDH-γ depletion (Fig. 4, C and D, and supplemental Fig. S2), whereas on their own, PDCD10 shRNAs had no effect on neuronal survival. Thus, these results demonstrate that PDCD10 is a key component in PCDH-γ-mediated regulation of neuronal survival.

PDCD10 Overexpression Is Sufficient to Induce Neuronal Apoptosis

The PDCD10 knockdown experiments identified a role of PDCD10 in the regulation of neuronal apoptosis during development. Therefore, we next performed a gain-of-function experiment to determine whether overexpression of PDCD10 is sufficient to induce apoptosis in the chicken spinal cord. After introducing PDCD10 expression vectors with different epitope tags, we assayed the apoptosis phenotype in the electroporated spinal cords. In comparison with the negative control spinal cords that expressed GFP, both tagged and nontagged PDCD10 significantly increased the number of active-CASP-3-positive neurons in the electroporated spinal cords (Fig. 5, A and B, and supplemental Fig. S3). Therefore, our data show that overexpression of PDCD10 is sufficient to induce neuronal apoptosis during spinal cord development.

To further investigate the relationship between the apoptotic activity of PDCD10 and its interaction with PCDH-γ, we asked whether overexpression of PCDH-γ could suppress PDCD10-induced apoptosis. We co-expressed PCDH-γ and PDCD10 and found that PCDH-γ overexpression attenuated PDCD10 apoptotic activity (Fig. 6, A and B, and supplemental Fig. S4). As a control, a cDNA encoding PCDH-γ-C5 isoform lack of the shared cytoplasmic domain did not rescue the apoptotic phenotype. Thus, this result suggests that the interaction between PCDH-γ and PDCD10 prevents PDCD10 from inducing apoptosis.

The subcellular localization of PCDH-γ has been well characterized (10, 24, 30). PCDH-γ proteins are localized on the plasma membrane and intracellular vesicles. To determine the subcellular localization of PDCD10 in neurons, we performed immunofluorescence staining using a PDCD10-specific antibody on cultured chicken spinal cord neurons (Fig. 7A). In neurons, PDCD10 is distributed throughout the cell including soma and neuronal processes. The specificity of PDCD10 immune staining was validated by significantly reduced signals in PDCD10 shRNA-expressing spinal cord neurons (Fig. 7A, lower panel). Interestingly, this broad distribution pattern is in contrast with the reported Golgi-enriched pattern in non-neuronal cells (36), perhaps due to a higher level of PDCD10 expression in neuronal cells or the presence of neuron-specific binding partners. Because both PDCD10 and PCDH-γ antibodies were generated in rabbit, we were not able to perform colocalization studies on two endogenous proteins. However, the individual proteins exhibited similar distributions along neuronal processes in cultured hippocampal neurons (Fig. 7B), suggesting that PCDH-γ and PDCD10 likely interact on the membrane. We hypothesized that the physical association of PDCD10 with the intracellular domain of PCDH-γ localizes PDCD10 adjacent to the plasma membrane, thus inhibiting PDCD10 from triggering an as yet unidentified apoptotic pathway. To test this idea, we constructed an expression vector encoding a membrane-bound myristoylated PDCD10 protein. Myr-PDCD10 is localized on the plasma membrane and neuronal processes, whereas regular PDCD10 exhibited diffuse staining throughout the cell as shown previously (Fig. 7C, right panels). Interestingly, expression of myristoylated PDCD10 failed to induce any apoptosis in the chicken spinal cord (Fig. 7C), thus suggesting that mislocalization of PDCD10 from the membrane to other cellular compartments in PCDH-γ-depleted cells might contribute to the induction of apoptosis. Therefore, during normal development, PCDH-γ may sequester PDCD10 to a membrane proximal compartment and inhibit its apoptotic activity, thus promoting neuronal survival.

PDCD10 Cooperates with PYK-2 in Regulation of Apoptosis

We have previously shown that PCDH-γ and PCDH-α negatively regulate PYK-2 and abnormal activation of PYK2 contributes to the apoptosis in Pcdh-γ null mice. Interestingly, GST-pulldown assay showed that PYK2 interacted with the C-terminal region of PCDH-γ cytoplasmic domain (γ-C45) (Fig. 8A), whereas PDCD10 interacted with the N-terminal region γ-C70 (Fig. 1D). Thus, we further tested whether PDCD10 could cooperate with PYK-2 to regulate neuronal apoptosis. We co-expressed MYC-PDCD10 and V5-PYK-2 and examined the induced apoptotic phenotype in the chicken spinal cord. The statistical analysis of apoptotic cell number in these experiments showed that co-expression of both MYC-PDCD10 and V5-PYK-2 induced statistically more apoptotic neurons compared with expression of the individual proteins (Fig. 8B). This result suggests that both PDCD10 and PYK-2, as downstream effectors of PCDH-γ, cooperate in regulating apoptosis (Fig. 8C).

DISCUSSION

Several lines of experimental evidence demonstrate that PCDH-γ proteins promote neuronal survival during development (10–12, 26). To understand the molecular mechanisms of how PCDH-γ mediates this regulation, we examined the function of a newly identified PCDH-γ downstream effector, PDCD10/CCM3, in this process. We show that PCDH-γ isoforms specifically bind to PDCD10 through their common cytoplasmic domain both in vitro and in vivo. In neuronal cells, PDCD10 appears to be an intracellular adaptor protein that is localized throughout the soma and neuronal processes. Knockdown of PDCD10 attenuates the apoptosis induced by PCDH-γ depletion. Moreover, ectopic expression of wild type PDCD10 but not membrane-bound PDCD10 is sufficient to trigger neuronal apoptosis in the developing spinal cord. Finally, we show that two PCDH-γ downstream effectors, PDCD10 and PYK2, can cooperate to induce neuronal apoptosis. Taken together, these data are consistent with a working model that multiple PCDH-γ isoforms, possibly with other PCDH family members, form large protein complexes that sequester PDCD10 and inhibit PYK2 kinase on the plasma membrane (23, 29, 30). Upon depletion of PCDH-γ complexes, the release of PDCD10 and abnormal activation of PYK2 contribute to excessive neuronal death observed in Pcdh-γ mutant animals (Fig. 8C). Thus, our data demonstrate that apart from its known function in endothelia cells and vascular tissues (36–39), PDCD10 acts as a key regulator of apoptosis downstream of PCDH-γ in the nervous system.

The question remains as to how PDCD10/CCM3 regulates apoptosis in the developing nervous system. PDCD10 has previously been identified as one of the causal genes for CCMs (cerebral cavernous malfunctions) (31, 40–42). CCMs are common vascular lesions characterized by enlarged, thin-walled, and leaky blood vessels in the central nervous system (37). Linkage studies of familiar CCMs have identified three autosomal dominant mutations: CCM1 (KRIT1), CCM2 (OSM), and CCM3 (PDCD10) (31, 40, 43–45). Functional analyses of these CCM genes using zebrafish and mouse models have indicated that CCM pathogenesis is likely linked to autonomous functions of CCM genes in vascular endothelial cells (39, 46–48). For example, the vascular abnormality in sata (the orthologue of CCM1) mutant zebrafish can be rescued by transplanting wild type endothelial cells (47). Similarly, vascular endothelial deletion of CCM3/PDCD10 recapitulated the deficits in vascular development seen in CCM3 global knock-out mouse embryos (39). Biochemical studies have shown that CCM3/PDCD10 binds to MST3/STK24, YSK1/SOK1/STK25, and MST4, members of the germinal center kinase III subfamily serine/threonine kinases (36, 38, 49, 50). Genetic interactions between ccm3 and stks deficiency have also been recently revealed in zebrafish (38). Therefore, the germinal center kinase III kinases appear to be essential downstream effectors of CCM3 during cardiovascular development. In neuronal tissues, PDCD10 may employ similar signaling mechanisms through the germinal center kinase III kinases to regulate neuronal survival. Consistent with this idea, binding of PDCD10 to MST4 has been shown to activate MST4 kinase activity in cultured cells, and all three germinal center kinase III kinases have been previously implicated in the regulation of apoptosis in non-neuronal cells (49, 51–54). Thus, it is important for future experiments to directly test the roles of these kinases as PDCD10 downstream effectors in the nervous system.

Despite seemingly obvious function of CCM3/PDCD10 in endothelial cells, expression studies revealed that CCM3/PDCD10 and other CCM genes are most abundantly expressed in the central nervous system (55–57), suggesting that CCM genes may have additional functions in neuronal cells. Noticeably, CCM2 has been recently identified as a key mediator of TrkA tyrosine kinase dependent cell death in neuroblastoma and medulloblastoma cells (58). Both genetic interactions and biochemical interactions among CCM1–3 genes have been described (59–61). It is therefore important to examine a larger protein network including all CCM proteins when considering downstream outputs of PDCD10/CCM3. Recent proteomic data show that both CCM1 and CCM3 can directly bind to CCM2 (61, 62). CCM2 is also known as OSM, which plays a role in the regulation of p38/MAPK in response to osmotic stress (63, 64). Thus, PCDH-γ may function as an upstream regulator of p38 kinase through a protein scaffold containing PDCD10-OSM. In this scenario, PCDH-γ promotes neuronal survival by repressing p38 activity. In the absence of Pcdh-γ, abnormal p38 activation leads to an excessive apoptosis during development. Consistent with this hypothesis, it is well documented that p38 activation induces neuronal apoptosis (65–70).

In this study, our data demonstrate a novel function of PDCD10/CCM3 as a key regulator of neuronal survival in the PCDH-γ pathway during development. Although the exact mechanism of how PDCD10 mediates this regulation remains to be determined, it is worth noting that PCDH-γ proteins are abundantly expressed in vascular endothelial cells in the brain. With up to 0.1–0.5% of the general population being affected by sporadic and inherited CCM (37), and the identified three familiar CCM genes only accounting for a rare minority of all CCM patients, our finding that PCDH-γ acts upstream of CCM3/PDCD10 points to a possibility that abnormal PCDH-γ signaling may contribute to the pathogenesis of CCM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Robert Holmgren and Joshua Sanes for critical reading and advice on the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant 5R01NS051253 (to X. W.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4.

- PCDH

- protocadherin(s)

- HH

- Hamberger and Hamilton

- co-IP

- co-immunoprecipitation

- DI

- death index

- Myr

- myristoylated

- PYK2

- proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2

- CAG

- CMV early enhancer/chicken β actin promoter.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oppenheim R. W. (1991) Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 453–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nijhawan D., Honarpour N., Wang X. (2000) Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 23, 73–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vecino E., Hernández M., García M. (2004) Int. J. Dev. Biol. 48, 965–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowrie M. B., Lawson S. J. (2000) Prog. Neurobiol. 61, 543–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buss R. R., Sun W., Oppenheim R. W. (2006) Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 29, 1–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies A. M. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 2537–2545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewin G. R., Barde Y. A. (1996) Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 289–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mennerick S., Zorumski C. F. (2000) Mol. Neurobiol. 22, 41–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silos-Santiago I., Greenlund L. J., Johnson E. M., Jr., Snider W. D. (1995) Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 5, 42–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X., Weiner J. A., Levi S., Craig A. M., Bradley A., Sanes J. R. (2002) Neuron 36, 843–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prasad T., Wang X., Gray P. A., Weiner J. A. (2008) Development 135, 4153–4164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lefebvre J. L., Zhang Y., Meister M., Wang X., Sanes J. R. (2008) Development 135, 4141–4151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emond M. R., Jontes J. D. (2008) Dev. Biol. 321, 175–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sano K., Tanihara H., Heimark R. L., Obata S., Davidson M., St John T., Taketani S., Suzuki S. (1993) EMBO J. 12, 2249–2256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohmura N., Senzaki K., Hamada S., Kai N., Yasuda R., Watanabe M., Ishii H., Yasuda M., Mishina M., Yagi T. (1998) Neuron 20, 1137–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu Q., Maniatis T. (1999) Cell 97, 779–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yagi T. (2008) Dev. Growth Differ. 50, S131–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X., Su H., Bradley A. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 1890–1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tasic B., Nabholz C. E., Baldwin K. K., Kim Y., Rueckert E. H., Ribich S. A., Cramer P., Wu Q., Axel R., Maniatis T. (2002) Mol. Cell 10, 21–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esumi S., Kakazu N., Taguchi Y., Hirayama T., Sasaki A., Hirabayashi T., Koide T., Kitsukawa T., Hamada S., Yagi T. (2005) Nat. Genet. 37, 171–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ribich S., Tasic B., Maniatis T. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 19719–19724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernández-Monreal M., Kang S., Phillips G. R. (2009) Mol Cell. Neurosci. 40, 344–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schreiner D., Weiner J. A. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 14893–14898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips G. R., Tanaka H., Frank M., Elste A., Fidler L., Benson D. L., Colman D. R. (2003) J. Neurosci. 23, 5096–5104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiner J. A., Wang X., Tapia J. C., Sanes J. R. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 8–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su H., Marcheva B., Meng S., Liang F. A., Kohsaka A., Kobayashi Y., Xu A. W., Bass J., Wang X. (2010) Dev. Biol. 339, 38–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasegawa S., Hamada S., Kumode Y., Esumi S., Katori S., Fukuda E., Uchiyama Y., Hirabayashi T., Mombaerts P., Yagi T. (2008) Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 38, 66–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katori S., Hamada S., Noguchi Y., Fukuda E., Yamamoto T., Yamamoto H., Hasegawa S., Yagi T. (2009) J. Neurosci. 29, 9137–9147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han M. H., Lin C., Meng S., Wang X. (2010) Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 71–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen J., Lu Y., Meng S., Han M. H., Lin C., Wang X. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 2880–2890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Denier C., Goutagny S., Labauge P., Krivosic V., Arnoult M., Cousin A., Benabid A. L., Comoy J., Frerebeau P., Gilbert B., Houtteville J. P., Jan M., Lapierre F., Loiseau H., Menei P., Mercier P., Moreau J. J., Nivelon-Chevallier A., Parker F., Redondo A. M., Scarabin J. M., Tremoulet M., Zerah M., Maciazek J., Tournier-Lasserve E. (2004) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74, 326–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y., Liu H., Zhang Y., Ma D. (1999) Sci. China C Life Sci. 42, 323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu Y., Lin C., Wang X. (2009) Nucleic Acids Res. 37, e141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakamura H., Funahashi J. (2001) Methods 24, 43–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brewer G. J., Torricelli J. R., Evege E. K., Price P. J. (1993) J. Neurosci Res. 35, 567–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fidalgo M., Fraile M., Pires A., Force T., Pombo C., Zalvide J. (2010) J. Cell. Sci. 123, 1274–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riant F., Bergametti F., Ayrignac X., Boulday G., Tournier-Lasserve E. (2010) FEBS J. 277, 1070–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng X., Xu C., Di Lorenzo A., Kleaveland B., Zou Z., Seiler C., Chen M., Cheng L., Xiao J., He J., Pack M. A., Sessa W. C., Kahn M. L. (2010) J. Clin. Invest. 120, 2795–2804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He Y., Zhang H., Yu L., Gunel M., Boggon T. J., Chen H., Min W. (2010) Sci. Signal. 3, ra26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bergametti F., Denier C., Labauge P., Arnoult M., Boetto S., Clanet M., Coubes P., Echenne B., Ibrahim R., Irthum B., Jacquet G., Lonjon M., Moreau J. J., Neau J. P., Parker F., Tremoulet M., Tournier-Lasserve E. (2005) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 76, 42–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guclu B., Ozturk A. K., Pricola K. L., Bilguvar K., Shin D., O'Roak B. J., Gunel M. (2005) Neurosurgery 57, 1008–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liquori C. L., Berg M. J., Squitieri F., Ottenbacher M., Sorlie M., Leedom T. P., Cannella M., Maglione V., Ptacek L., Johnson E. W., Marchuk D. A. (2006) Hum. Mutat. 27, 118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laberge-le Couteulx S., Jung H. H., Labauge P., Houtteville J. P., Lescoat C., Cecillon M., Marechal E., Joutel A., Bach J. F., Tournier-Lasserve E. (1999) Nat. Genet. 23, 189–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liquori C. L., Berg M. J., Siegel A. M., Huang E., Zawistowski J. S., Stoffer T., Verlaan D., Balogun F., Hughes L., Leedom T. P., Plummer N. W., Cannella M., Maglione V., Squitieri F., Johnson E. W., Rouleau G. A., Ptacek L., Marchuk D. A. (2003) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 73, 1459–1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sahoo T., Johnson E. W., Thomas J. W., Kuehl P. M., Jones T. L., Dokken C. G., Touchman J. W., Gallione C. J., Lee-Lin S. Q., Kosofsky B., Kurth J. H., Louis D. N., Mettler G., Morrison L., Gil-Nagel A., Rich S. S., Zabramski J. M., Boguski M. S., Green E. D., Marchuk D. A. (1999) Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 2325–2333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chan A. C., Li D. Y., Berg M. J., Whitehead K. J. (2010) FEBS J. 277, 1076–1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hogan B. M., Bussmann J., Wolburg H., Schulte-Merker S. (2008) Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 2424–2432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boulday G., Blécon A., Petit N., Chareyre F., Garcia L. A., Niwa-Kawakita M., Giovannini M., Tournier-Lasserve E. (2009) Dis. Model Mech. 2, 168–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ma X., Zhao H., Shan J., Long F., Chen Y., Chen Y., Zhang Y., Han X., Ma D. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell. 18, 1965–1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Voss K., Stahl S., Hogan B. M., Reinders J., Schleider E., Schulte-Merker S., Felbor U. (2009) Hum. Mutat. 30, 1003–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dan I., Ong S. E., Watanabe N. M., Blagoev B., Nielsen M. M., Kajikawa E., Kristiansen T. Z., Mann M., Pandey A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 5929–5939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang C. Y., Wu Y. M., Hsu C. Y., Lee W. S., Lai M. D., Lu T. J., Huang C. L., Leu T. H., Shih H. M., Fang H. I., Robinson D. R., Kung H. J., Yuan C. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 34367–34374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu H. Y., Lin C. Y., Lin T. Y., Chen T. C., Yuan C. J. (2008) Apoptosis 13, 283–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nogueira E., Fidalgo M., Molnar A., Kyriakis J., Force T., Zalvide J., Pombo C. M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 16248–16258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petit N., Blécon A., Denier C., Tournier-Lasserve E. (2006) Gene Expr. Patterns. 6, 495–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Plummer N. W., Squire T. L., Srinivasan S., Huang E., Zawistowski J. S., Matsunami H., Hale L. P., Marchuk D. A. (2006) Mamm. Genome 17, 119–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tanriover G., Boylan A. J., Diluna M. L., Pricola K. L., Louvi A., Gunel M. (2008) Neurosurgery 62, 930–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harel L., Costa B., Tcherpakov M., Zapatka M., Oberthuer A., Hansford L. M., Vojvodic M., Levy Z., Chen Z. Y., Lee F. S., Avigad S., Yaniv I., Shi L., Eils R., Fischer M., Brors B., Kaplan D. R., Fainzilber M. (2009) Neuron 63, 585–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pagenstecher A., Stahl S., Sure U., Felbor U. (2009) Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 911–918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Voss K., Stahl S., Schleider E., Ullrich S., Nickel J., Mueller T. D., Felbor U. (2007) Neurogenetics 8, 249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hilder T. L., Malone M. H., Bencharit S., Colicelli J., Haystead T. A., Johnson G. L., Wu C. C. (2007) J. Proteome Res. 6, 4343–4355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zawistowski J. S., Stalheim L., Uhlik M. T., Abell A. N., Ancrile B. B., Johnson G. L., Marchuk D. A. (2005) Hum Mol. Genet. 14, 2521–2531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Uhlik M. T., Abell A. N., Johnson N. L., Sun W., Cuevas B. D., Lobel-Rice K. E., Horne E. A., Dell'Acqua M. L., Johnson G. L. (2003) Nat. Cell. Biol. 5, 1104–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fong B., Watson P. H., Watson A. J. (2007) BMC Dev. Biol. 7, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xia Z., Dickens M., Raingeaud J., Davis R. J., Greenberg M. E. (1995) Science 270, 1326–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng A., Chan S. L., Milhavet O., Wang S., Mattson M. P. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 43320–43327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harada J., Sugimoto M. (1999) Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 79, 369–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kummer J. L., Rao P. K., Heidenreich K. A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 20490–20494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Horstmann S., Kahle P. J., Borasio G. D. (1998) J. Neurosci. Res. 52, 483–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Linseman D. A., Laessig T., Meintzer M. K., McClure M., Barth H., Aktories K., Heidenreich K. A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39123–39131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.