Abstract

G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) channels are parasympathetic effectors in cardiac myocytes that act as points of integration of signals from diverse pathways. Neurotransmitters and hormones acting on the Gq protein regulate GIRK channels by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) depletion. In previous studies, we found that endothelin-1, but not bradykinin, inhibited GIRK channels, even though both of them hydrolyze PIP2 in cardiac myocytes, showing receptor specificity. The present study assessed whether the spatial organization of the PIP2 signal into caveolar microdomains underlies the specificity of PIP2-mediated signaling. Using biochemical analysis, we examined the localization of GIRK and Gq protein-coupled receptors (GqPCRs) in mouse atrial myocytes. Agonist stimulation induced a transient co-localization of GIRK channels with endothelin receptors in the caveolae, excluding bradykinin receptors. Such redistribution was eliminated by caveolar disruption with methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD). Patch clamp studies showed that the specific response of GIRK channels to GqPCR agonists was abolished by MβCD, indicating the functional significance of the caveolae-dependent spatial organization. To assess whether low PIP2 mobility is essential for PIP2-mediated signaling, we blocked the cytoskeletal restriction of PIP2 diffusion by latrunculin B. This abolished the GIRK channel regulation by GqPCRs without affecting their targeting to caveolae. These data suggest that without the hindered diffusion of PIP2 from microdomains, PIP2 loses its signaling efficacy. Taken together, these data suggest that specific targeting combined with restricted diffusion of PIP2 allows the PIP2 signal to be compartmentalized to the targets localized closely to the GqPCRs, enabling cells to discriminate between identical PIP2 signaling that is triggered by different receptors.

Keywords: Caveolae, G Protein-coupled Receptor (GPCR), Membrane Lipid, Phospholipase C, Potassium Channel, GIRK Channel, Gq-coupled Receptor, PIP2, Cardiac Myocyte, Compartmentalization

Introduction

Several lines of evidence suggest that neurohormonal imbalance plays a role in the generation of atrial fibrillation (1). Simultaneous sympathetic and parasympathetic (sympathovagal) activation facilitates the onset of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (2). In addition, vasoactive peptide hormones such as endothelin-1 (ET-1)3 (3) and angiotensin II (4) have been implicated in atrial fibrillation. The cardiovascular actions of native peptides and receptors showed a wide range of variety. Unlike ET-1 and angiotensin II, myocardial bradykinin (BK) might be a mechanism to protect the heart during acute myocardial infarction (5, 6). The neurohormonal imbalances have seldom been sufficiently characterized to study their pathophysiology.

One possible candidate for cross-talk for sympathovagal interaction and neurohormonal interaction in cardiac myocytes is the acetylcholine activated K+ (GIRK) channel. Recently, we and others found that α1-adrenergic receptor agonist inhibits GIRK channels by depleting PIP2 in the plasma membrane, indicating a novel pathway for sympathetic-parasympathetic interaction (7, 8). ET-1 and angiotensin II can also regulate GIRK channel activity via PIP2 signaling (8, 9). Thus, GIRK channels might act as points to integrate hormonal and neurotransmitter signals from diverse pathways. However, although GIRK channels are regulated by PIP2, they do not respond to PIP2 hydrolysis from stimulation of all Gq-coupled receptors. We found that BK had no effect on GIRK channels, although being capable of hydrolyzing PIP2 in cardiac myocytes (9). It is possible that these selective responses could discriminate the beneficial effect associated with BK from other Gq protein-coupled receptor (GqPCR) pathways. Until now, the molecular mechanisms underlying receptor specificity have been mostly unknown.

Several mechanisms were suggested to explain the receptor-specific and target-specific PIP2 signaling. One of those mechanisms is the PIP2 microdomain (10). In this scenario, PIP2 abundance can change independently within a restricted area, so that the activation of a given GqPCR affects only those targets that are partitioned in the same microdomain. However, it is unclear whether and how PIP2-sensitive targets are co-localized with specific GqPCRs in atrial myocytes.

Recent data showed that caveolae are important for co-localization of receptors with their signaling partners (11). Caveolae are small invaginations of the plasma membranes, and caveolins are the main structural components of caveolae (12, 13). It has been suggested that by selectively excluding or concentrating signaling proteins, caveolae confer a degree of spatial organization on signal transduction pathways (11, 14). Some receptors and signaling proteins are not fixed in the membrane but are translocated into or out of caveolae upon receptor activation (11, 15–17).

The present study offers the direct evidence that agonist stimulation induces a transient co-localization of GIRK channels with ET A receptor (ETAR) in caveolae, excluding BK B2 receptor (B2R) in mouse atrial myocytes, and that such compartmentalization is essential for receptor specificity in PIP2 signaling. Thus, the PIP2 microdomain created by caveolae plays a key role in the spatiotemporal coding of PIP2 signals, ensuring specificity of GqPCRs in cardiac myocytes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Isolation

Mouse atrial myocytes were isolated by perfusing Ca2+-free normal Tyrode solution containing collagenase (0.14 mg/ml; Yakult Pharmaceutical, Japan) on a Langendorff column at 37 °C as described (18). Isolated atrial myocytes were kept in high K+, low Cl− solution at 4 °C until use.

Electrophysiology

Membrane currents were recorded from single isolated myocytes in a perforated patch configuration by using nystatin (200 μg/ml; ICN) or ruptured whole cell patch clamp configuration at 35 ± 1 °C. Voltage clamp was performed by using an EPS-8 amplifier (HEKA Instruments) and filtered at 5 kHz. The patch pipettes (World Precision Instruments) were made by a Narishige puller (PP-830; Narishige, Tokyo). The patch pipettes used had a resistance of 2–3 megohms when filled with the below pipette solutions. Normal Tyrode solution contained 140 mm NaCl, 5.4 mm KCl, 0.5 mm MgCl2, 1.8 mm CaCl2, 10 mm glucose, and 5 mm HEPES, titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH. The Ca2+-free solution contained 140 mm NaCl, 5.4 mm KCl, 0.5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm glucose, and 5 mm HEPES, titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH. The high K+ and low Cl− solution contained 70 mm KOH, 40 mm KCl, 50 mm l-glutamic acid, 20 mm taurine, 20 mm KH2PO4, 3 mm MgCl2, 10 mm glucose, 10 mm HEPES, and 0.5 mm EGTA, adjusted to pH 7.3 with KOH. The pipette solution for perforated patches contained 140 mm KCl, 10 mm HEPES, 1 mm MgCl2, and 5 mm EGTA, titrated to pH 7.2 with KOH. The pipette solution for ruptured whole cell patches contained 20 mm KCl, 110 mm potassium aspartate, 10 mm NaCl, 10 mm HEPES, 1 mm MgCl2, 2 mm MgATP, 5 mm EGTA, and 0.01 mm GTP, titrated to pH 7.2 with KOH. To ensure a rapid solution turnover, the rate of superfusion was kept at >5 ml/min, which corresponded to 50 times bath volume (100 μl).

Subcellular Fractionation

Subcellular fractionation was performed as described previously (19). Briefly, atrial tissue were homogenized in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 120 mm NaCl, 20 mm NaF, 1 mm EDTA, 5 mm EGTA, 1 mm benzamidine, and 0.1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) supplemented with protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science) and fractionated by sequential centrifugation steps. The tissue homogenate was centrifuged at 500 × g for 15 min, and the pellet was discarded. The supernatant was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to separate a vesicle-containing soluble fraction and membrane-containing pellet fraction. Samples were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE.

Western Blotting and Immunoprecipitation

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation analyses were done as described previously (19). Primary antibodies used were anti-GIRK1 (Alomone Laboratories), anti-M2AChR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-B2R (BD Transduction Laboratories), anti-ETAR (BD Transduction Laboratories), anti-Cav-3 (BD Transduction Laboratories), anti-EEA1 (BD Transduction Laboratories), and anti-pan-cadherin (AbCam). Protein bands were quantified with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Immunocytochemistry

Immunostaining was performed on isolated mouse atrial myocytes as described previously (20). Briefly, atrial myocytes were plated on laminin (10 μg/ml)-coated coverslips for 3 h at 4 °C, fixed with 4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) on ice, permeabilized in 5% goat serum in PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 (30 min), incubated with the primary antibody against Cav-3 and WGA-Alexa-633 (overnight), followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody for 1 h. Immunofluorescence was visualized with confocal laser scanning microscopy using a LSM510 apparatus (Zeiss). Cells were randomly selected and used for imaging and analysis, and immunostaining experiments were repeated at least five times. Control experiments performed by using secondary antibody without primary antibody showed no noticeable labeling.

Confocal Ca2+ Imaging

For confocal Ca2+ imaging, freshly isolated mouse atrial myocytes were loaded with Fluo-4 AM (5 μm; Molecular Probes) for 30 min followed by a 10-min washout allowing for deesterification. Fluorescence images were recorded using a Leica TCSSP2 confocal microscope with ×63 water immersion objective (Leica). Fluo-4 was excited with 488-nm laser, and the fluorescence was detected at >505 nm. All experiments were conducted at 35 ± 1 °C.

Statistics and Presentation of Data

Results in the text and the figures are presented as mean ± S.E. (n = number of cells tested). Statistical analyses were performed by using Student's t test. The difference between two groups was considered to be significant when p < 0.01.

RESULTS

Caveolar Disruption Abolishes Receptor Specificity of GIRK Channel Regulation

From acutely isolated mouse atrial myocytes, membrane currents were recorded using a nystatin-perforated whole cell patch clamp technique, at a holding potential of −40 mV. When acetylcholine (ACh, 100 μm) was applied to the bath solution, IGIRK was promptly activated and underwent variable degrees of desensitization (Fig. 1A, top). Consistent with previous data (7, 9), desensitization recovered after washout of ACh, so IGIRK during a second ACh stimulation (I2) was similar to that during the first stimulation (I1) (Fig. 1B, right). The amplitudes of I2 measured at its peak (I2,peak) were 84.4 ± 2.4% of those of I1 (I1,peak) (n = 9; supplemental Fig. 1) and quasi-steady-state amplitudes of I2 (I2,qss) were 87.6 ± 2.3% of those of I1 (I1,qss) (n = 9, Fig. 1B). To investigate the effect of GqPCR-mediated signaling on IGIRK, GqPCR agonists were applied together with ACh in the second stimulation, and I2 was compared with I1. Fig. 1A (middle) illustrates typical examples of these experiments showing the effects of ET-1 (30 nm). Addition of ET-1 in the second stimulation did not cause significant changes in peak currents (supplemental Fig. 1), but accelerated the current decay, with the result that I2,qss was reduced significantly compared with I1,qss. I2,qss was 24.6 ± 5.9% (n = 6) of I1,qss, which was significantly smaller than the I2,qss in the absence of GqPCR agonists (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1B). In contrast, when the effect of BK on IGIRK was investigated using the same experimental protocol, I1 and I2 traces were almost completely overlapped (Fig. 1A, bottom). The decay phase of the current, as well as the peak amplitude, is unchanged by BK (Fig. 1B and supplemental Fig. 1), indicating that BK could not regulate IGIRK. This suggests that, as previously reported for these cells (9), GqPCR-induced regulation of IGIRK was receptor-specific.

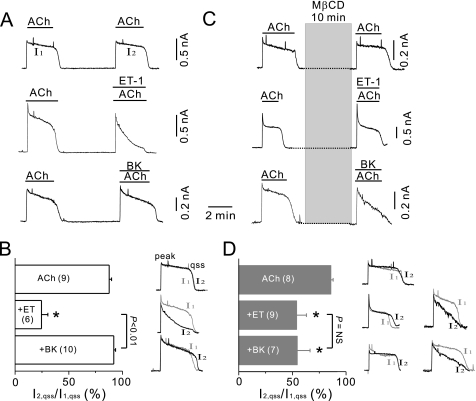

FIGURE 1.

Treatment with MβCD abolished the receptor-specific inhibition of IGIRK by GqPCR agonists. A, top, ACh (100 μm) induced K+ current (IGIRK) in mouse atrial cells. The second application of ACh was 4 min after washout of the first. Middle, ET-1 (30 nm) induced a profound inhibition of IGIRK. Bottom, BK (10 μm) did not affect IGIRK. B, histogram shows relative amplitudes (percent) of I2,qss with respect to I1,qss. *, p < 0.05 compared with ACh alone. Right, IGIRK during a first ACh stimulation (I1) and that during the second stimulation (I2) obtained from the experiment shown in A, are superimposed, showing the effect of the drugs on IGIRK. C, top, the second application of ACh was after 10-min treatment of MβCD. MβCD pretreatment did not affect IGIRK. Middle, MβCD pretreatment attenuated the effects of ET-1 on IGIRK. Bottom, MβCD pretreatment increased the effects of BK on IGIRK. D, data are summarized for I2,qss/I1,qss in cells pretreated with MβCD. *, p < 0.05, compared with ACh alone. Right, current traces obtained from the experiment shown in C are superimposed. Two representative traces for ET-1 or BK stimulated cells are shown.

If caveolae compartmentalize GIRK channels to ETARs, excluding B2Rs, the response of GIRK channels should be forced to be nonspecific by disruption of caveolae. To test this scenario, mouse atrial myocytes were pretreated with MβCD, which disrupts caveolae by depleting cholesterol (21, 22). We confirmed that treatment with 3 mm MβCD for 10 min did not affect IGIRK. The response to ACh following MβCD treatment (I2), was similar to that to ACh before MβCD application (I1) (Fig. 1C, top). I2,peak and I2,qss were 87.0 ± 5.5% (n = 8; supplemental Fig. 1) and 85.7 ± 2.3% (Fig. 1D) of those of I1 (I1,peak and I1,qss), respectively, which were not significantly different from the relative I2,peak and I2,qss under control. Then, the effects of ET-1 and BK on IGIRK were examined in MβCD-treated cells. As in the control, GqPCR agonists accelerated the decay phase of IGIRK, without significant changes in peak amplitude. However, the inhibitory effect of ET-1 (30 nm) on IGIRK was significantly attenuated and its effect varied in a wide range among cells (Fig. 1, C, middle, and D, right). On average, the I2,qss was 53.8 ± 9.3% (n = 9) of the I1,qss in MβCD-treated cells, which was significantly different from the result in the control (24.6 ± 5.9%, n = 6, p < 0.05). A dose-response curve performed in the presence after MβCD pretreatment was shifted to the right, with decrease of its maximum response (supplemental Fig. 2). BK stimulation also showed variable effects on IGIRK following MβCD treatment. In some cases, BK, which showed a minimal effect on IGIRK under control, induced a robust inhibition of IGIRK (Fig. 1C, bottom). On average, BK reduced I2,qss to 54.4 ± 12.1% (n = 7) of I1,qss (Fig. 1D). BK suppression of IGIRK was greater than the meager BK effect in control conditions and indistinguishable from the extent of ET-1-induced inhibition after MβCD pretreatment (p > 0.05, Fig. 1D). Thus, these data showed that the receptor-specific inhibition of IGIRK by GqPCR agonists was not observed when caveolae was disrupted, suggesting that caveolae are signaling platforms where receptor-specific regulation of GIRK channel is taking place in cardiac myocytes.

Association of M2AChR/GIRK Channel Complexes with Cav-3 during ACh Stimulation

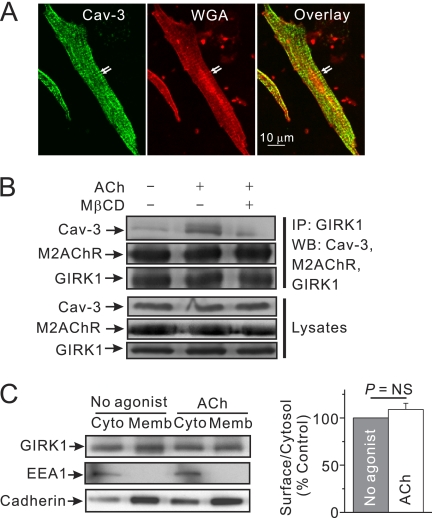

The next experiment examined whether GIRK channels and GqPCRs are localized to caveolae. Initially, the presence of caveolae in mouse atrial myocytes was confirmed. Consistent with a previous study (21), immunostaining using the antibody against caveolin-3 (Cav-3, green), a marker for caveoale of cardiac myocytes, clearly revealed Cav-3 along the peripheral sarcolemma and T tubules, coinciding with the location of the membrane dye WGA (red) (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Caveolar targeting of activated GIRK channel in response to M2AChR stimulation. A, immunofluorescence images of atrial myocytes labeled with Cav-3 antibody (green) and WGA-Alexa Fluor 633 (red). Arrows indicate T-tubules. Scale bar, 10 μm. B, atrial tissue was treated with control buffer or with 100 μm ACh alone for 4 min or after 10-min pretreatment of 10 mm MβCD at 37 °C. Tissue lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-GIRK1 antibody and then immunoblotted with anti-GIRK1, anti-Cav-3, or anti-M2AChR antibodies. C, cytoplasm and the membrane components of atrial myocytes were fractionated as described in under “Experimental Procedures,” and each fraction was confirmed by immunoblotting with antibodies against specific marker proteins; pan-cadherin for plasma membrane; EEA1 for early cytoplasmic endosome. Right, ratio of surface to intracellular localized GIRK channel was not significantly affected by ACh. Expression level of surface or cytosolic GIRK channels was normalized to the level of pan-cadherin or EEA1, respectively (n = 3). NS, not significant.

The spatial resolution of confocal microscopy is inadequate to localize proteins to caveolae definitively given the small size of caveolae (50–100 nm). Therefore, co-immunoprecipitation experiments were used to determine whether GIRK channels were localized to caveolae. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments showed that GIRK1 protein, the GIRK channel subunit, interacts with Cav-3 (Fig. 2B), suggesting the localization of GIRK1 at caveolae. Stimulation of M2AChR with ACh significantly increased the association of GIRK1 with Cav-3. This effect was prevented by the caveolar disruption with MβCD, suggesting that this process requires intact caveolae. In contrast, the amount of M2AChR that was co-precipitated with the GIRK channels was not affected by either ACh alone or combined treatment of MβCD and ACh. Consistent with a previous report (23), these data suggest that GIRK channels form stable complexes with M2AChR. The marginal effect of MβCD treatment on the responses of GIRK channels for ACh may be due to the relatively strong association of M2AChR and GIRK proteins (Fig. 1D). The expression levels of Cav-3 and M2AChR were not changed after agonist stimulation. ACh stimulation did not affect the localization of GIRK1 proteins (Fig. 2C). Taken together, these data support the suggestion that ACh treatment may induce the movement of GIRK1 proteins on the membrane to Cav-3 inside the caveolae structure.

Agonist Stimulation Increases Caveolar Association of ETAR and Decreases B2R Association

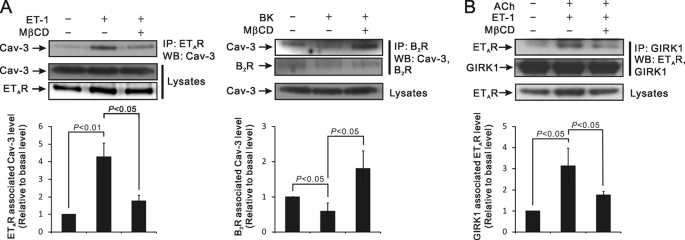

The next experiment examined the association of GqPCRs with Cav-3. ETAR and B2R mediate ET-1- or BK-induced PIP2 hydrolysis in cardiac myocytes, respectively (24, 25). Although treatment of ET-1 (30 nm, 4 min) increased the association of ETARs with Cav-3 (p < 0.01), BK application (10 μm, 4 min) decreased the association of B2Rs with Cav-3 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3A). MβCD pretreatment abrogated both of the ET-1 and BK effects (p < 0.05), suggesting that both processes require an intact caveolae structure.

FIGURE 3.

Agonist stimulation induces the association of GIRK channels and ETAR proteins with Cav-3 and the release of B2R from Cav-3. A, atrial tissue was treated with control buffer or with 30 nm ET-1 (upper) or 10 μm BK (lower) alone for 4 min or after 10-min pretreatment of 10 mm MβCD at 37 °C. Tissue lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-ETAR (upper) or anti-B2R (lower) antibodies and then immunoblotted with anti-Cav-3 or anti-B2R antibodies. Histograms show the protein levels of Cav-3 associated with either ETAR or anti-B2R, respectively, under conditions indicated in the figure. The results shown are averages of three independent experiments, quantified by ImageJ. The results were also analyzed using Student's t test. B, atrial tissue was treated with control buffer or with a combination of ACh and ET-1 before and after pretreatment of MβCD at 37 °C, as indicated, was immunoprecipitated with anti-GIRK1, and then immunoblotted with anti-GIRK1 or anti-ETAR antibodies. The results shown were quantified by ImageJ and analyzed using Student's t test.

Next, it was determined whether ETAR and GIRK channels interact with each other in caveolae. ETARs proteins were co-immunoprecipitated with GIRK1, and the association of ETAR with GIRK1 was increased by concurrent stimulation of ETARs and M2AChR/GIRK channel signaling pathway by ET-1 and ACh treatment (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3B). MβCD pretreatment blocked this process (p < 0.05), suggesting that the association of ETAR and GIRK proteins requires the caveolae.

Cytoskeletal Restriction of PIP2 Diffusion Is Necessary for PIP2 Signaling

Our previous simulation study (26) showed that the low mobility of PIP2 promotes locally high [PIP2] changes and limits PIP2 signal into neighboring regions, contributing to the formation of PIP2 microdomains. However, there is no direct evidence that low PIP2 mobility is necessary for PIP2-mediated signaling in cardiac myocytes. To examine whether the change in PIP2 mobility affects GqPCR-induced GIRK channel regulation in mouse atrial myocytes, latrunculin B, an inhibitor of actin filament polymerization, was utilized to manipulate PIP2 mobility. PIP2 diffusion increases markedly upon cytoskeletal disruption (26). When atrial myocytes were pretreated with latrunculin B (10 μm) for 30 min, the regulation of GIRK channels by ET-1 was completely abolished, so that I1 and I2 are almost completely overlapped (Figs. 4A). I2,qss in the presence of ET-1 was 89.7 ± 5.0% (n = 6) of the I1,qss, which is significantly different from that under control condition (24.6 ± 5.9% (n = 6), p < 0.01, Fig. 4C). BK also had no effect on IGIRK (Fig. 4B). The relative amplitude of I2,qss (I2,qss/I1,qss) in the presence of BK was 91.3 ± 3.9% (n = 3; Fig. 4C).

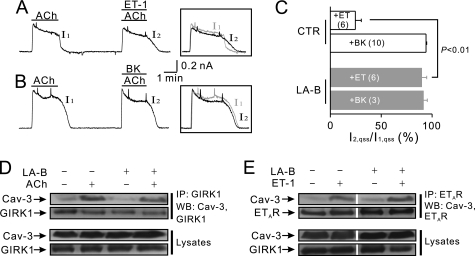

FIGURE 4.

Effects of latrunculin B on GqPCR-induced GIRK channel regulation. A and B, after 30-min pretreatment of latrunculin B (10 μm), ET-1 effects were completely abolished (A). BK also had no effects on IGIRK (B). Inset, current traces in control (I1) and in the presence of each GqPCR agonist (I2) are superimposed to show the effect of the drugs on IGIRK. C, data of IGIRK inhibition by ET-1 and BK in control conditions and in cells loaded with latrunculin B (LA-B) are summarized. D, atrial tissue was treated with control buffer or ACh before and after 30-min preincubation of 10 μm latrunculin B at 37 °C, as indicated, and then was immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-GIRK1 antibody and immunoblotted (WB) with anti-GIRK1 or anti-Cav-3 antibodies. E, atrial tissue was treated with control buffer or ET-1 before and after 30-min preincubation of 10 μm latrunculin B at 37 °C, as indicated, then immunoprecipitated with anti-ETAR and immunoblotted with anti-ETAR or anti-Cav-3 antibodies. In D and E, all four conditions were processed simultaneously.

To rule out the possibility that latrunculin B affects PIP2-mediated signal by blocking the dynamic targeting, the association of GIRK channels with Cav-3 in latrunculin B-pretreated cardiac myocytes was examined. ACh stimulation increased the association of Cav-3 with the GIRK channel regardless of latrunculin pretreatment (Fig. 4D), and latrunculin B also did not affect the increase in the association of ETARs to Cav-3 during ETAR stimulation (Fig. 4E). These data indicate that latrunculin treatments did not inhibit the caveolar targeting of GIRK channels or GqPCRs. Taken together, these data suggest that latrunculin B might affect GqPCR-induced GIRK regulation by disrupting the barrier to PIP2 diffusion, suggesting the critical importance of low PIP2 mobility in efficient PIP2-mediated signaling.

PIP2 Regeneration Is Not Involved in Receptor Specificity of GIRK Channel Regulation

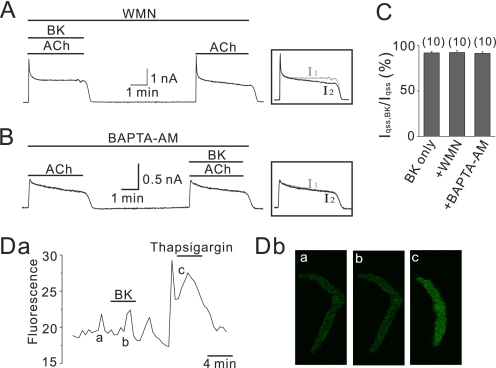

An alternative hypothesis of receptor specificity for GIRK channel regulation is that as exemplified by the N-type Ca2+ channel modulation in SCG neuron (27), B2Rs promote activity of PI4-kinase, which compensates for the PIP2 depletion induced by the phospholipase C pathway. If this is true in atrial myocytes, then it should be possible to for B2R to modulate GIRK channels in atrial myocytes by acute PI4-kinase blockade. To test this possibility, 10 μm BK was applied in the presence of 50 μm wortmannin (WMN) (Fig. 5A). This brief treatment (∼10 min) by WMN should be sufficient to block PI4-kinase but would not be long enough to cause substantial PIP2 depletion by itself, as evidenced by the only minor rundown of IGIRK during WMN application (7). Although this maneuver indeed conferred to B2Rs the ability to suppress ICa with the same potency as for muscarinic M1 receptors in SCG neurons (28), it did not cause BK to induce an inhibition of IGIRK (Fig. 5A). In the WMN-treated cells the qss amplitude of I2 in the presence of BK was 92.2 ± 2.1% (n = 10) of I1,qss. This was not significantly different from I2,qss/I1,qss in the control experiments (91.8 ± 1.6%, n = 10, p > 0.05).

FIGURE 5.

Blocking PIP2 resynthesis pathway does not affect the sensitivity of GIRK channels to B2R. A, even in the presence of WMN (50 μm), BK effects on IGIRK were not affected, and current after washout of BK was completely recovered. B, effects of BK on IGIRK when the cells were incubated with 10 μm BAPTA-AM for 30 min are shown. Note that BK did not affect IGIRK. C, data of IGIRK inhibition by BK in various conditions are summarized. The numbers in parentheses indicate numbers of cells. Da, atrial myocytes were loaded with 5 μm Fluo-4 AM for Ca2+ measurements. Cells were treated with BK or thapsigargin as indicated by horizontal bars above the traces. BK does not affect [Ca2+]. Db, confocal image of control (a), after BK application, (b), and after thapsigargin treatment (c) in the Da are shown.

The potent Gq regulation of PIP2 synthesis was mediated via increases of [Ca2+]i acting as the stimulus (28). Therefore, an experiment was done to assess whether blocking the increase of intracellular Ca2+ would allow B2R modulation of GIRK channels. Fig. 5B shows a perforated patch experiment on atrial myocytes pretreated with BAPTA-AM (10 μm, 30 min), a membrane-permeant Ca2+-specific chelator. The cells did not respond to BK stimulation; I2,qss was 91.3 ± 2.0% (n = 10) of I1, similar to control cells (p > 0.05). BAPTA under ruptured whole cell conditions produced similar results (90.9 ± 2.5%, n = 6). The data are summarized in Fig. 5C.

Next, the ability of BK to mobilize Ca2+ from intracellular IP3 stores in atrial myocytes was assessed. [Ca2+]i was measured in undialyzed cells with the membrane-permeant dye Fluo-4 AM (Fig. 5D). In contrast to BK stimulation in neurons, Ca2+ mobilization was not detectable in atrial myocytes. Taken together, unlike stimulation of B2Rs in SCG neurons, B2Rs in atrial myocytes may not induce a compensatory PIP2 synthesis during concurrent PIP2 depletion.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study demonstrate that the agonist-induced association of GIRK channel and selective receptors to caveoale is necessary for receptor-specific regulation of GIRK channels. In contrast to B2Rs, ETARs are clustered with GIRK channels to form discrete signaling complexes during receptor stimulation. The low PIP2 mobility limits the propagation of the PIP2 signal and confines PIP2 depletion to ETARs and co-localized GIRK channels, ensuring specificity of the signaling pathway.

Signaling Microdomains for PIP2

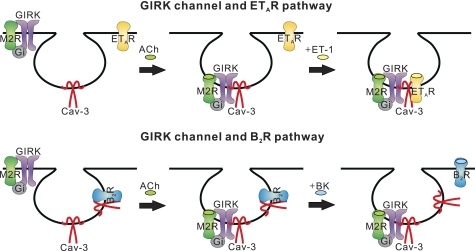

The results show that agonist stimulation induced signaling complexes linking ETAR and GIRK channels, excluding B2Rs. The signaling pathway involved in GIRK channel regulation is illustrated schematically in Fig. 6. Immunoprecipitation analysis suggests that M2AChR stimulation can induce the targeting of the M2AChR-GIRK channel complex to Cav-3, most probably via their lateral redistribution along the cell surface (Fig. 2). Immunoprecipitation data for GqPCR localization suggest that agonist stimulation might also induce the targeting of ETAR to Cav-3 but diminish B2R binding to Cav-3 (Fig. 3). By binding GIRK channel and ETAR receptors in caveolae, Cav-3 might bring both GIRK channel and ETAR in close proximity to each other, enabling these proteins to interact. This notion is supported by the fact that co-precipitation of ETAR and GIRK channels was increased after simultaneous activation of both pathways. In contrast, B2R dissociated from Cav-3 during B2R stimulation. By losing the scaffolding network, they could not interact with GIRK channel complexes.

FIGURE 6.

Schematic diagram of signaling microdomain for specific PIP2 signal. Stimulation of M2AChR/GIRK pathway and ETAR induce the recruitments of each component to Cav-3, which allow ETAR to interact with GIRK channels (upper). In contrast, B2R are dissociated from Cav-3 during B2R stimulation. By losing scaffolding network, they cannot interact with GIRK channel complexes any more (lower).

Caveolar disruption eliminated the receptor specificity of PIP2-mediated GIRK channel regulation (Fig. 1), suggesting that compartmentalization of GIRK channels and GqPCRs by caveolae may be important for specificity of PIP2 signals. However, co-localization of GIRK channels with their signaling partners can be attributed to, but is not solely sufficient, to cause receptor-specific regulation of GIRK channels. The present results show that when PIP2 mobility was high, GqPCR-induced regulation of GIRK channel was abolished (Fig. 4), suggesting that low mobility of PIP2 may be necessary for GqPCR-mediated regulation of GIRK. Thus, it is conceivable that only when combined with low PIP2 mobility, can complexes of ETARs with GIRK channels induce changes in [PIP2] in close proximity to GIRK channels high enough to induce a strong inhibition of GIRK channels. In line with this, B2Rs, which are physically excluded and remote from GIRK channel domains, might fail to deplete PIP2 near GIRK channels. This could prevent B2R from inhibiting GIRK channels. Furthermore, the possibility that receptor specificity of PIP2 signaling could be induced by differential abilities of GqPCRs to induce a compensatory PIP2 synthesis during concurrent PIP2 depletion could be ruled out (Fig. 5). In summary, given a diffusion-limited PIP2 signal, the geometric relationship between GIRK channels and GqPCRs determines the precise nature of the physiological response to this signal.

Caveolae as Organizer of GIRK Channel Signaling Network

Caveolae are abundantly present in cardiac myocytes, including ventricular, atrial, and nodal cells (12). Although the caveolae of ventricle modulate excitation-contraction coupling, β2-adrenergic signaling, and ATP-sensitive K+ channel regulation (21, 22, 29), the role of caveolae in the atria remains unclear. The current data showed that caveolae can act as signaling platforms linking GIRK channels and GqPCRs in mouse atrial myocytes. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show the role of caveolae in the receptor specificity of PIP2 signaling in native cardiac myocytes.

The ability of caveolae to coordinate signaling pathways is related to the ability of selectively recruiting a certain set of signaling molecules while excluding others. Still, the mechanism responsible for reversible caveolin-protein interaction is unclear. It is conceivable that GIRK channels might be passively recruited to Cav-3 together with M2AChR, based on the fact that GIRK channels were occupied in stable association with M2AChR (Fig. 2) (23), which is known to translocate into the caveolae upon stimulation (30). In the case of ETAR, it is possible that its palmitoylation after agonist stimulation increases the affinity of ETAR for the caveolar membrane (31, 32). In contrast to these receptors, B2R seems to translocate out of, rather than into, caveolae with receptor activation. These data conflict with reports showing the translocation of B2Rs into caveolae upon agonist stimulation in A431 cells (33) and HEK293 cells (34). This discrepancy implies that the redistribution of GPCR to stimulation differs depending on cell type (35). Experimental manipulations such as exposure time to agonist also need to be considered; presently, the effects of acute stimulation (4 min) on the localization of receptor were observed, whereas others focused on the effects of prolonged simulation (10–30 min) (33, 34). Indeed, receptor trafficking out of caveolae is not uncommon. A1-adenosine receptors of cardiac myocytes (15) and adrenergic β2- receptors were reported to exit caveolae upon receptor stimulation. Thus, dynamic targeting of GPCRs and stimulus-dependent protein-protein associations could be the logical mechanisms to ensure specificity of signaling, at the same time permitting similar pathways to exist in different parts of the same cell (Fig. 6).

Because caveolae contribute to the fine spatial control of PIP2 signaling, changes in the caveolae density/function will perturb the compartmentalization of PIP2 signals, thereby affecting the ability of cardiac cells to produce the receptor-specific GIRK channel responses. Given that changes in caveolin expression, location, and caveolae density are seen with age, in cardiovascular diseases including cardiac hypertrophy, cardiac failure, and diabetes and following the use of drugs such as statins for treatment of cardiovascular disease (36), this has wide implications. It is possible that dysregulation of the caveolar organization could contribute to arrhythmia or heart failure by affecting GIRK signaling complexes and consequently resulting in sympathovagal imbalance (37, 38). This hypothesis is strongly supported by the previous study reporting the development of heart failure in Cav-3−/− mice (11).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Jong-Sun Kang for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by Grant A080604 from the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare, and Family Affairs, Republic of Korea.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1 and 2.

- ET-1

- endothelin-1

- ACh

- acetylcholine

- BK

- bradykinin

- B2R

- BK B2 receptor

- Cav

- caveolin

- ETAR

- ET A receptor

- GIRK

- G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+

- GqPCR

- Gq protein-coupled receptor

- MβCD

- methyl-β-cyclodextrin

- PIP2

- phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- qss

- quasi-steady state

- WGA

- wheat germ agglutinin

- WMN

- wortmannin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen P. S., Tan A. Y. (2007) Heart Rhythm 4, S61–S64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharifov O. F., Fedorov V. V., Beloshapko G. G., Glukhov A. V., Yushmanova A. V., Rosenshtraukh L. V. (2004) J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 43, 483–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolettis T. M., Kyriakides Z. S., Zygalaki E., Kyrzopoulos S., Kaklamanis L., Nikolaou N., Lianidou E. S., Kremastinos D. T. (2008) J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 21, 203–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai C. T., Lai L. P., Lin J. L., Chiang F. T., Hwang J. J., Ritchie M. D., Moore J. H., Hsu K. L., Tseng C. D., Liau C. S., Tseng Y. Z. (2004) Circulation 109, 1640–1646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitakaze M., Node K., Takashima S., Minamino T., Kuzuya T., Hori M. (2000) Hypertens. Res. 23, 253–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoemaker R. G., van Heijningen C. L. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 278, H1571–H1576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho H., Nam G. B., Lee S. H., Earm Y. E., Ho W. K. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 159–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer T., Wellner-Kienitz M. C., Biewald A., Bender K., Eickel A., Pott L. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 5650–5658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho H., Lee D., Lee S. H., Ho W. K. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 4643–4648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gamper N., Shapiro M. S. (2007) J. Physiol. 582, 967–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Razani B., Woodman S. E., Lisanti M. P. (2002) Pharmacol. Rev. 54, 431–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balijepalli R. C., Kamp T. J. (2008) Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 98, 149–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen A. W., Hnasko R., Schubert W., Lisanti M. P. (2004) Physiol. Rev. 84, 1341–1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lisanti M. P., Scherer P. E., Vidugiriene J., Tang Z., Hermanowski-Vosatka A., Tu Y. H., Cook R. F., Sargiacomo M. (1994) J. Cell Biol. 126, 111–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lasley R. D., Narayan P., Uittenbogaard A., Smart E. J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 4417–4421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ostrom R. S., Bundey R. A., Insel P. A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 19846–19853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rybin V. O., Xu X., Lisanti M. P., Steinberg S. F. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 41447–41457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho H., Youm J. B., Ryu S. Y., Earm Y. E., Ho W. K. (2001) Br. J. Pharmacol. 134, 1066–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bae G. U., Gaio U., Yang Y. J., Lee H. J., Kang J. S., Krauss R. S. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 8301–8309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobrzynski H., Marples D. D., Musa H., Yamanushi T. T., Henderson Z., Takagishi Y., Honjo H., Kodama I., Boyett M. R. (2001) J. Histochem. Cytochem. 49, 1221–1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balijepalli R. C., Foell J. D., Hall D. D., Hell J. W., Kamp T. J. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 7500–7505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garg V., Jiao J., Hu K. (2009) Cardiovasc. Res. 82, 51–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavine N., Ethier N., Oak J. N., Pei L., Liu F., Trieu P., Rebois R. V., Bouvier M., Hebert T. E., Van Tol H. H. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 46010–46019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minshall R. D., Nakamura F., Becker R. P., Rabito S. F. (1995) Circ. Res. 76, 773–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaguchi H., Sakamoto N., Watanabe Y., Saito T., Masuda Y., Nakaya H. (1997) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 273, H1745–H1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho H., Kim Y. A., Yoon J. Y., Lee D., Kim J. H., Lee S. H., Ho W. K. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 15241–15246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delmas P., Coste B., Gamper N., Shapiro M. S. (2005) Neuron 47, 179–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gamper N., Reznikov V., Yamada Y., Yang J., Shapiro M. S. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 10980–10992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calaghan S., White E. (2006) Cardiovasc. Res. 69, 816–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feron O., Smith T. W., Michel T., Kelly R. A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 17744–17748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horstmeyer A., Cramer H., Sauer T., Müller-Esterl W., Schroeder C. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 20811–20819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feron O., Balligand J. L. (2006) Cardiovasc. Res. 69, 788–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haasemann M., Cartaud J., Muller-Esterl W., Dunia I. (1998) J. Cell Sci. 111, 917–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sabourin T., Bastien L., Bachvarov D. R., Marceau F. (2002) Mol. Pharmacol. 61, 546–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ostrom R. S., Insel P. A. (2004) Br. J. Pharmacol. 143, 235–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sbaa E., Frérart F., Feron O. (2005) Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 15, 157–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfaffinger P. J., Martin J. M., Hunter D. D., Nathanson N. M., Hille B. (1985) Nature 317, 536–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakmann B., Noma A., Trautwein W. (1983) Nature 303, 250–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.