Abstract

Context

Pain and depression are two of the most prevalent and treatable cancer-related symptoms, yet frequently go unrecognized and/or undertreated.

Objective

To determine whether centralized telephone-based care management coupled with automated symptom monitoring can improve depression and pain in cancer patients.

Design, Setting, and Patients

Randomized controlled trial conducted in 16 community-based urban and rural oncology practices across the state of Indiana. Recruitment occurred from March 2006 through August 2008 and follow-up concluded in August 2009. The 405 patients had depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score ≥ 10), cancer-related pain (Brief Pain Inventory worst pain score ≥ 6), or both.

Intervention

Patients were randomly assigned to the intervention (n=202) or to usual care (n=203), stratified by symptom type. Intervention patients received centralized telecare management by a nurse-physician specialist team coupled with automated home-based symptom monitoring by interactive voice recording or internet.

Main Outcome Measures

Blinded assessment at baseline, 1, 3, 6, and 12 months for depression (20-item Hopkins Symptom Checklist [HSCL-20]) and pain (Brief Pain Inventory [BPI]) severity.

Results

There were 131 patients enrolled with depression only, 96 with pain only, and 178 with both depression and pain. Of the 274 patients enrolled for pain, the 137 intervention patients had greater improvements than the 137 usual care patients in BPI pain severity over the 12 months of the trial whether measured as a continuous severity score or as a categorical pain responder (P < .0001 for both). Similarly, of the 309 patients enrolled for depression, the 154 intervention patients had greater improvements than the 155 usual care patients in HSCL-20 depression severity over the 12 months of the trial whether measured as a continuous severity score (P < .0001) or as a categorical depression responder (P < .001). The standardized effect size for between-group differences at 3 and 12 months was .67 and .39 for pain, and .42 and .44 for depression.

Conclusion

Centralized telecare management coupled with automated symptom monitoring resulted in improved pain and depression outcomes in cancer patients receiving care in geographically-dispersed urban and rural oncology practices.

Keywords: cancer, pain, depression, antidepressants, analgesics, telemedicine, care management

Pain and depression are the most common physical and psychological symptoms, respectively, in cancer patients.1–4 However, despite their prevalence and associated disability,5–10, cancer-related pain and depression are frequently undetected and undertreated.1,11–15

Collaborative care is a team-based approach in which a care manager supervised by a physician specialist work together with the principal provider to optimize outcomes through educating patients, monitoring adherence and therapeutic response, and adjusting treatment. Various collaborative care models have well-established effectiveness for enhancing depression outcomes, with most trials conducted in primary care16,17, though a few in specialty clinic settings have shown benefits in post-stroke18 and post-CABG depression.19 Two recent trials in primary care suggest collaborative interventions may enhance pain outcomes as well.20,21

Therefore, we conducted the Indiana Cancer Pain and Depression (INCPAD) trial, a collaborative care approach to managing depression and pain in geographically-dispersed oncology practices. Centralized care management combined with automated disease monitoring facilitated coverage of multiple urban and rural oncology practices throughout an entire state. Our hypothesis was that this telecare management intervention would be superior to usual care in improving the co-primary study outcomes of pain and depression.

METHODS

Identifying and Enrolling Study Subjects

Details of the INCPAD trial design have been previously described.22 Study participants were enrolled from 16 urban and rural oncology practices in Indiana from March 2006 through August 2008. The practices included 10 that were staffed by Community Cancer Care which provides satellite oncology services to rural areas and mid-sized communities throughout Indiana, 4 large oncology clinics in Indianapolis, 1 oncology clinic providing care for underserved patients, and 1 VA oncology clinic. Patients presenting for oncology clinic visits who screened positive for either pain or depression underwent an eligibility interview; all eligibility criteria relied on patient report. Eligible patients who were willing to participate provided audiotaped oral informed consent (with follow-up written consent forms obtained by mail) and completed a baseline interview after which they were randomized to the intervention or usual care group. Randomization was computer-generated in randomly varying block sizes of 4, 8 and 12 and stratified by symptom type (pain only, depression only, or both pain and depression). The study was approved by the institutional review boards.

Study Eligibility

Depression had to be at least moderately severe, defined as a Patient Health Questionnaire nine-item depression scale (PHQ-9) score ≥ 10 and endorsement of either depressed mood and/or anhedonia.23,24 Pain had to be: (a) definitely or possibly cancer-related; (b) at least moderately severe, defined as a score of ≥ 6 on the “worst pain in the past week” item of the Brief Pain Inventory;14,25,26 and (c) persistent despite trying one or more analgesics. Excluded were individuals who did not speak English; had moderately severe cognitive impairment as defined by a validated 6-item cognitive screener27; had schizophrenia or other psychosis; had a pending pain-related disability claim; were pregnant; or were in hospice care.

Outcome Assessment

All five assessments (baseline, 1, 3, 6, and 12 months) were administered by telephone interview and conducted by research assistants blinded to treatment arm. These research assistants had no involvement in the study intervention and their call list included participant name and study number but not treatment arm. Depression and pain severity were the two co-primary study outcomes. Depression severity was assessed with the Hopkins Symptom Checklist twenty-item depression scale (HSCL-20)28–30 Pain severity was assessed with the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) which rates the severity of pain on 4 items (current, worst, least, and average pain in past week).14,31 Scores range from 0 to 4 on the HSCL-20 and from 0 to 10 on the BPI, with higher scores representing greater severity.

Secondary depression-specific outcomes included the 3-item depression severity subscale of the SF-36 Mental Health Inventory32 and depression diagnostic status as assessed by the PHQ-9.23 Secondary pain-specific outcomes included the SF-36 bodily pain scale,33 the BPI interference scale,14,31 and global change in pain assessed with a 7-point scale with the options being worse, the same, or a little, somewhat, moderately, a lot, or completely better.34

Secondary outcomes assessed in the full sample included health-related quality of life, disability, co-interventions, and self-reported health care use. The SF-12 was used to calculate Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores.35 Overall quality of life was assessed with a single-item 0 to 10 scale.36 Anxiety was assessed by the seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) scale.37,38 Physical symptom burden was assessed with a 22-item somatic symptom scale.22 Fatigue was assessed with the SF-36 vitality scale.33 Disability was assessed with the 3-item Sheehan Disability Scale 39 and the number of self-reported days in which activities were limited during the preceding 4 weeks.40,41 Because pain and depression treatment and outcomes may vary by race or ethnicity,42,43 race/ethnicity (identified by the patient from preselected options) was also included as a demographic characteristic.

A treatment survey inquired about treatments received for pain and depression as well as self-reported health care use. For intervention patients, the number of months on antidepressant and opioid medications and number of care manager contacts were abstracted from care manager logs, and the number of automated symptom monitoring contacts was determined from computerized reports.

Intervention

Care Management

Telephonic care management was delivered by a nurse care manager (NCM) trained in assessing symptom response and medication adherence; in providing pain and depression-specific education; and in making treatment adjustments according to evidence-based guidelines. The NCM met weekly to review cases with the pain-psychiatrist specialist who was also available to discuss management issues that arose between case management meetings. Subjects received a baseline and 3 follow-up NCM calls (1, 4, and 12 weeks) during the first 3 months of treatment. In addition to these scheduled NCM phone contacts, triggered phone calls occurred when automated monitoring indicated inadequate symptom improvement, nonadherence to medication, side effects, suicidal ideation, or a patient request to be contacted.

Automated Symptom Monitoring

Automated symptom monitoring (ASM) was performed using either interactive voice recorded (IVR) telephone calls or web-based surveys based upon patient preference. The 21-item ASM survey included the PHQ-9 depression scale, 8 pain items from the BPI (3 severity and 5 interference), and a single item each on medication adherence, side effects, global improvement, and whether or not the patient would like a NCM call. ASM was administered twice a week for the first 3 weeks, then weekly during weeks 4 through 11, twice a month during months 3 through 6, and once a month during months 7 through 12. However, more frequent ASM could be reinstituted for subjects who underwent treatment changes. Those not completing their scheduled assessment were contacted telephonically by the NCM.

Medication Management

Details of the INCPAD treatment protocol including the antidepressant and analgesic algorithms have been previously published.22 Treatment recommendations were provided to the study participant’s oncologist who was responsible for prescribing all medications. The antidepressant algorithm was informed by the multi-center STAR*D trial and our primary care based SCAMP trial.34,44 The analgesic algorithm used in INCPAD was adapted from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Cancer Pain Guidelines.45, with some simplification based upon other guidelines.46–48 For depression, the goal was remission (PHQ-9 score < 5) or, failing this, a PHQ-9 score < 10 with a ≥50% decline from the baseline score. Subjects who preferred not to take antidepressants were encouraged to consider a referral to mental health referral for psychotherapy. For pain, the goal was to obtain a ≥30% reduction in the BPI pain score and, ideally, a score of ≤3. In participants with both pain and depression, the protocol focused on pain treatment for the first 4 weeks, unless depression was more severe (PHQ-9 scores ≥ 15)23,24 If depression persisted despite this initial treatment period for pain, antidepressant therapy was recommended.

Usual Care Group

Patients randomized to usual care were informed of their depressive and pain symptoms and their screening results were provided to their oncologist. There were no further attempts by study personnel to influence depression or pain management unless a psychiatric emergency arose (e.g., suicidal ideation was detected on baseline or follow-up outcome assessment).

Statistical Analysis

The study was powered to detect clinically significant improvement in the two primary outcomes of depression (HSCL-20) and pain (BPI). A reduction of ≥ 50% in depression severity and ≥ 30% in pain severity are accepted thresholds for clinically significant improvement in depression and pain trials, respectively.49,50 It was determined that 97 subjects per symptom group would provide 80% power to detect a 20% absolute difference in response rates with two-tailed alpha < .05. This sample size also provided 80% power to detect a moderate treatment effect size of 0.4 when analyzing depression and pain as continuous outcomes. Enrollment of 120 patients per group with pain (240 total) and 120 patients per group with depression (240 total) allowed for up a 20% attrition rate. Preliminary work demonstrated that approximately a quarter of patients had pain only, a third had depression only and 40–45% had both depression and pain. Thus, to enroll at least 240 patients with pain and 240 patients with depression, INCPAD required an estimated sample size of 380.

Analyses were based on intention-to-treat in all randomized participants. Group differences over the 12 months of the trial were compared using mixed effects model repeated measures (MMRM) analysis, adjusting for baseline value of the outcome variable and time.51 To accommodate the large variability of the health care use data, negative binomial distribution regression analysis was used to model count data.

Analyses were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. This does not affect interpretation of our primary outcomes (HSCL-20 and BPI severity), but findings for secondary outcomes should be interpreted cautiously unless they are highly significant (P < .001). Analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

As a sensitivity analysis, we also compared group differences using two imputation strategies: last-observation carried forward (LOCF) imputation for all outcomes and multiple regression imputation for our primary outcomes. There was no difference in the magnitude of missing data between the treatment groups. Further, logistic regression models showed that intervention and control participants for which 12-month data was missing did not differ in terms of baseline depression or pain severity, age, gender, cancer type, or phase of cancer. For participants who died during the 12-month period following their study enrollment, imputation was right censored, i.e., no data was imputed beyond the date of death.

Depression-specific outcomes were compared in participants enrolled with depression, pain-specific outcomes in those enrolled with pain, and secondary outcomes (health-related quality of life, disability, health care use, and co-interventions) in the full sample. Stratifying randomization by symptom type assured that the proportion of patients with depression only, pain only, and comorbid pain and depression was balanced among intervention and control groups. For the primary outcomes, standardized effect sizes were calculated as the mean group difference divided by the pooled standard deviation at baseline. For patients who died, time to death was compared between treatment groups using survival analysis.

RESULTS

Participant Enrollment and Baseline Characteristics

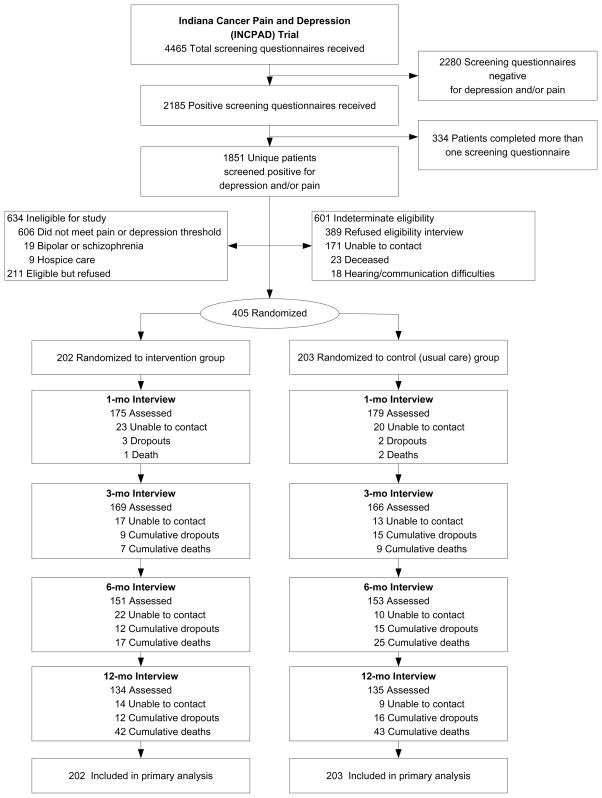

Figure 1 summarizes the participant flow in INCPAD. Of the 616 subjects in which eligibility could be ascertained, about two-thirds consented to enroll in the study and were randomized to either the intervention or the usual care control group. The intervention and control groups were similar in terms of overall mortality (42 [20.8%] vs. 43 [21.2%] as well as time to death [P = .94 by log-rank test]. Among participants still alive at each follow-up point, assessment rates were similar in both groups and uniformly high, including 88.1% (354/402] at 1 month, 86.1% [335/389] at 3 months, 83.7% [304/363] at 6 months, and 84.1% [269/320] at 12 months

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participants in the INCPAD trial

Of the 405 participants enrolled, randomization resulted in intervention (n = 202) and control (n = 203) groups balanced in terms of baseline characteristics (Table 1). The sample included 131 (32%) participants with depression only, 96 (24%) with pain only, and 178 (44%) with both depression and pain. The average SCL-20 depression score in the 309 depressed participants was 1.64 (on a 0–4 scale), and the average BPI severity score (i.e., mean of the 4 severity items) in the 274 participants with pain was 5.2 (on a 0–10 scale), representing at least moderate levels of symptom severity. Also, 283 (92%) of the 309 patients enrolled for depression had major depression, dysthymia, or both.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the 405 Subjects Enrolled in INCPAD Trial*

| Baseline Characteristic | Intervention Group (N=202) | Usual Care Group (N=203) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age, yr | 58.7 (11.0) | 59.0 (10.6) | .81 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 128 (63) | 147 (72) | .051 |

| Race, n (%) | .32 | ||

| White | 159 (79) | 163 (80) | |

| Black | 40 (20) | 33 (16) | |

| Other | 3 (2) | 7 (3) | |

| Education, n (%) | .36 | ||

| Less than High school | 45 (22) | 42 (21) | |

| High school | 83 (41) | 77 (38) | |

| Some college or trade school | 55 (27) | 53 (26) | |

| College graduate | 19 (9) | 31 (15) | |

| Married, n (%) | 109 (54) | 90 (44) | .053 |

| Employment status, n (%) | .57 | ||

| Employed | 36 (18) | 45 (22) | |

| Unable to work due to poor health or disability | 90 (45) | 86 (42) | |

| Retired | 62 (31) | 55 (27) | |

| Other | 13 (6) | 17 (8) | |

| Patient-perceived level of income, n (%) | .67 | ||

| Comfortable | 46 (23) | 54 (27) | |

| Just enough to make ends meet | 99 (49) | 95 (47) | |

| Not enough to make ends meet | 57 (28) | 54 (27) | |

| Mean (SD) no. of medical diseases | 2.0 (1.6) | 2.2 (1.6) | .23 |

| Symptom group, n (%) | 1.00 | ||

| Depression only | 65 (32) | 66 (33) | |

| Pain only | 48 (24) | 48 (24) | |

| Depression and pain | 89 (44) | 89 (44) | |

| Phase of cancer, n (%) | .082 | ||

| Newly-diagnosed | 74 (36.6) | 76 (37.4) | |

| Maintenance or disease-free | 78 (38.6) | 94 (46.3) | |

| Recurrent or progressive | 50 (24.8) | 33 (16.3) | |

| Type of cancer, n (%) | .21 | ||

| Breast | 55 (27) | 63 (31) | |

| Lung | 42 (21) | 39 (19) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 40 (20) | 30 (15) | |

| Lymphoma and hematological | 22 (11) | 31 (15) | |

| Genitourinary | 17 (8) | 24 (12) | |

| Other | 26 (13) | 16 (8) | |

| Mean (SD) scores | |||

| BPI pain severity (score range, 0–10) | 4.30 (2.36) | 4.23 (2.35) | .74 |

| SCL-20 depression (score range, 0–4) | 1.43 (0.71) | 1.46 (0.71) | .62 |

| Sheehan Disability Index (score range, 0 to 10) | 5.44 (2.84) | 5.44 (2.88) | .99 |

| Overall quality of life (score range, 0 to 10) | 5.74 (2.28) | 5.51 (2.27) | .30 |

| Bed days in past 4 weeks | |||

| Median (interquartile range) | 2 (0–10) | 1 (0–10) | |

| Mean (SD) | 5.6 (7.3) | 5.7 (8.1) | .91 |

| Days in which activities reduced by ≥ 50% in past 4 weeks (excluding bed days) | |||

| Median (interquartile range) | 10 (4–16) | 10 (3–18) | |

| Mean (SD) | 11.3 (8.9) | 11.1 (9.1) | .84 |

| Baseline medication use, n (%)b | |||

| Antidepressants (excluding tricyclics) | 71 (36) | 80 (41) | .24 |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | 13 (7) | 22 (11) | .09 |

| Psychotropics (excluding antidepressants) | 52 (26) | 64 (33) | .13 |

| Opioid analgesics | 107 (54) | 107 (55) | .75 |

| Nonopioid analgesics | 87 (44) | 91 (46) | .50 |

| Currently being seen by a mental health professional, n (%) | 18 (9) | 26 (13) | .21 |

| Currently being seen in a pain clinic, n (%) | 12 (6) | 9 (4) | .49 |

Baseline medication data was available from the oncology medical records for 396 (97.8%) of the 405 participants, including 200 in the intervention group and 196 in the usual care group

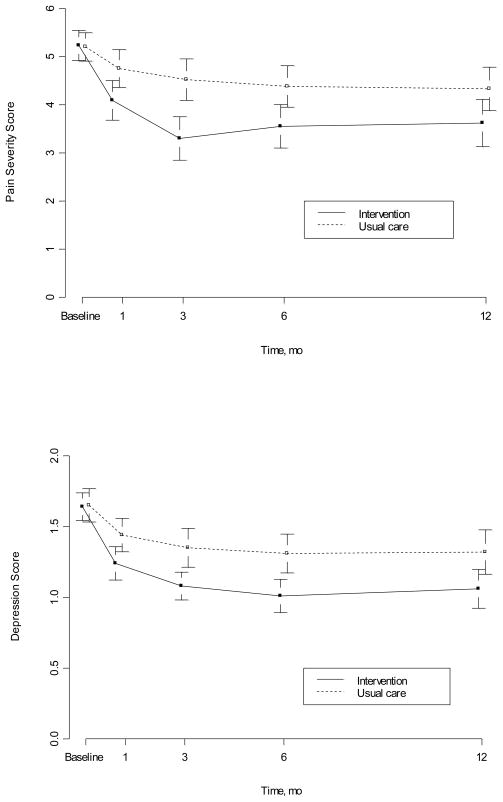

Pain-Specific Outcomes

Table 2 summarizes the pain-specific outcomes among the 274 patients enrolled for pain. For the primary outcome (BPI pain severity), the 137 intervention patients had significantly greater improvement than the 137 usual care patients by MMRM analysis (P < .0001) over the 12 months of the trial whether measured as a continuous severity score or as a categorical pain responder (Table 2 and Figure 2). Between-group differences for BPI pain severity as both a continuous variable and a categorical response variable were also significant at all time points for assessed cases (Table 2) and for assessed and imputed cases using LOCF and multiple regression imputation analyses (not shown). The standardized effect size for the between-group differences at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months was .36, .67, .46, and .39, respectively. Effect sizes of 0.2 and 0.5 represent modest and moderate differences, respectively.52.

Table 2.

Pain-Specific Outcomes in the 274 Participants Enrolled in the INCPAD Trial for Pain

| Clinical Outcome | Intervention (137)a | Usual Care (137)a | Time-Specific Between-Group Difference or Relative Risk (95% CI) | Overall P value by MMRMb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary pain outcome (n = assessed cases) | ||||

| BPI pain severity, mean (SD) (range, 0–10) | <.0001 | |||

| Baseline (n = 274) | 5.23 (1.85) | 5.20 (1.78) | 0.03 (−0.40 to 0.46) | |

| 3-mo follow-up (n = 230) | 3.30 (2.45) | 4.52 (2.33) | −1.22 (−1.85 to −0.60) | |

| 6-mo follow-up (n = 206) | 3.55 (2.36) | 4.38 (2.21) | −0.83 (−1.46 to −0.20) | |

| 12-mo follow-up (n = 180) | 3.62 (2.42) | 4.33 (2.21) | −0.70 (−1.39 to −0.02) | |

| BPI pain severity responder, N (%)c | <.0001 | |||

| 3-mo follow-up (n = 230) | 67 (57.3) | 34 (30.1) | 1.90 (1.38 to 2.63) | |

| 6-mo follow-up (n = 206) | 51 (49.5) | 27 (26.2) | 1.89 (1.29 to 2.76) | |

| 12-mo follow-up (n = 180) | 46 (50.6) | 31 (34.8) | 1.45 (1.02 to 2.06) | |

| Secondary pain outcomes (n = assessed cases) | ||||

| BPI pain interference, mean (SD) (range, 0–10) | <.0001 | |||

| Baseline (n = 274) | 5.35 (2.62) | 5.96 (2.48) | −0.61 (−1.22 to 0.00) | |

| 12-mo follow-up (n = 168) | 3.86 (2.45) | 5.08 (2.88) | −1.22 (−2.04 to −0.40) | |

| SF-36 bodily pain scale, mean (SD) (range, 0–100) | .004 | |||

| Baseline (n = 272) | 32.8 (18.1) | 30.7 (17.5) | 2.1 (−2.1 to 6.4) | |

| 12-mo follow-up (n = 179) | 48.4 (24.7) | 39.0 (22.6) | 9.4 (2.4 to 16.4) | |

The number of subjects with pain who were assessed for pain outcomes was 230 (117 intervention and 113 controls) at 3 months, 206 (103 intervention and 103 controls) at 6 months, and 180 (91 intervention and 89 controls) at 12 months.

Mixed effects model repeated measures (MMRM) analysis was used to compare group differences over 12 months, adjusting for time effect and for baseline value of outcome variable. Assessments were conducted at baseline, 1, 3, 6 and 12 months for BPI severity and interference and at baseline, 3 and 12 months for SF-36 bodily pain.

Defined as 30% or greater decrease in BPI severity from baseline

Figure 2.

Co-primary outcomes. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Top graph represents mean Brief Pain Inventory Severity scores, which can range from 0 to 10. There were 137 intervention and 137 control patients with pain assessed at baseline, 117 and 120 at 1 month, 117 and 113 at 3 months, 103 and 103 at 6 months, and 91 and 89 at 12 months. Bottom graph represents mean 20-item Hopkins Symptoms Checklist depression scores, which can range from 0 to 4. There were 154 intervention and 155 control patients with depression assessed at baseline, 131 and 136 at 1 month, 124 and 122 at 3 months, 110 and 113 at 6 months, and 98 and 104 at 12 months. Intervention patients had significantly lower pain (P < .0001) and depression (P < .0001) severity scores over the 12 months of the trial by mixed effects model repeated measures (MMRM) analysis.

Intervention patients also had greater improvement in the secondary pain-specific outcomes of BPI pain interference and SF-36 bodily pain scores (Table 2). Additionally, global ratings of change showed there were significant between-group differences at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months (eFigure 1 [http://www.jama.com]).

Depression-Specific Outcomes

Table 3 summarizes the depression-specific outcomes among the 309 depressed patients enrolled in INCPAD. For the primary outcome (HSCL-20 depression severity), the 154 depressed intervention patients had significantly greater improvement than the 155 depressed usual care patients by MMRM analysis (P < .0001) over the 12 months of the trial whether measured as a continuous severity score or as a categorical depression responder (Table 3 and Figure 2). Between-group differences for HSCL-20 as a continuous variable were also significant at all time points for available cases (Table 3) and for assessed and imputed cases using LOCF and multiple regression imputation analyses (not shown); a categorical depression response was significantly more likely in the intervention group at 1, 3, and 6 months but not at 12 months. The standardized effect size for these between-group differences at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months was .31, .42, .45, and .44, respectively.

Table 3.

Depression-Specific Outcomes in the 309 Participants Enrolled in the INCPAD Trial for Depression

| Clinical Outcome | Intervention (154)a | Usual Care (155)a | Time-Specific Between-Group Difference or Relative Risk (95% CI) | Overall P value by MMRMb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary depression outcome (n = assessed cases) | ||||

| HSCL-20 depression severity, mean (SD) (range, 0–4) | <.0001 | |||

| Baseline (n = 309) | 1.64 (0.63) | 1.64 (0.65) | 0.00 (−0.15 to 0.14) | |

| 3-mo follow-up (n = 246) | 1.08 (0.61) | 1.35 (0.73) | −0.27 (−0.44 to −0.10) | |

| 6-mo follow-up (n = 223) | 1.01 (0.59) | 1.31 (0.73) | −0.29 (−0.47 to −0.12) | |

| 12-mo follow-up (n = 202) | 1.06 (0.65) | 1.32 (0.83) | −0.26 (−0.46 to −0.05) | |

| HSCL-20 depression severity responder, N (%) c | <.001 | |||

| 3-mo follow-up (n = 246) | 45 (36.3) | 25 (20.5) | 1.77 (1.16 to 2.70) | |

| 6-mo follow-up (n = 223) | 42 (38.2) | 27 (23.9) | 1.60 (1.06 to 2.40) | |

| 12-mo follow-up (n = 202) | 33 (33.7) | 29 (27.9) | 1.21 (0.80 to 1.83) | |

| Secondary depression outcomes (n = assessed cases) | ||||

| Major depressive disorder, N (%) | .002 | |||

| Baseline (n = 309) | 94 (61.0) | 96 (61.9) | 0.99 (0.83 to 1.18) | |

| 3-mo follow-up (n = 247) | 30 (24.2) | 47 (38.2) | 0.63 (0.43 to 0.93) | |

| 12-mo follow-up (n = 203) | 21 (21.4) | 37 (35.2) | 0.61 (0.38 to 0.96) | |

| Mental Health Inventory depression severity subscale, mean (SD), range (3–15) | .009 | |||

| Baseline (n = 309) | 8.61 (2.82) | 8.99 (2.59) | −0.38 (−0.98 to 0.23) | |

| 12-mo follow-up (n = 202) | 7.01 (2.58) | 7.91 (3.00) | −0.90 (−1.68 to −0.12) | |

The number of depressed subjects who were assessed for depression outcomes was 246–247 (124 intervention and 122–123 controls) at 3 months, 223 (110 intervention and 113 controls) at 6 months, and 202–203 (98 intervention and 104–105 controls) at 12 months.

Mixed effects model repeated measures (MMRM) analysis was used to compare group differences over 12 months, adjusting for time effect and for baseline value of outcome variable. Assessments were conducted at baseline, 1, 3, 6 and 12 months for HSCL-20 and at baseline, 3 and 12 months for secondary depression outcomes.

Defined as 50% or greater decrease in HSCL-20 from baseline

Intervention patients also had greater improvement in the secondary depression-specific outcomes of MHI depression severity and depression diagnostic status. While a similar proportion of intervention and usual care patients met criteria for major depressive disorder at baseline, significantly fewer intervention patients had major depressive disorder at 3 months and 12 months.

Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQL), Health Care Use, and Co-Interventions

Between-group differences in secondary outcomes that were not pain- or depression-specific were assessed in all 405 participants. The intervention group had better outcomes by MMRM analysis for several HRQL domains, including mental health, vitality, anxiety, and physical symptom burden (eTable 1 [http://www.jama.com]). The intervention group also had greater improvement on the Sheehan Disability Scale but did not differ from the usual care group in self-reported disability days, physical health, or overall quality of life. In contrast to MMRM, LOCF analyses were not significant for any of the HRQL outcomes.

Compared to controls, intervention patients showed a trend towards fewer hospital days (mean of 3.6 vs. 5.8) and emergency department visits (mean of 1.0 vs. 1.4), but there was large variability in all 5 measures of health care use and none of the between-group differences were statistically significant (eTable 2 [http://www.jama.com]). The groups were also similar in self-reported use of 11 of 12 potential co-interventions (eTable 2), differing only in use of “other pain treatments” (p = .03).

Intensity of Intervention in Terms of Contacts and Medication

Intervention intensity could only be assessed in the intervention group because this data was abstracted from care manager and automated symptom monitoring logs. Participants in the intervention group had a mean of 11.2 ± 8.1 care manager telephone contacts and 20.5 ±10.6 automated symptom monitoring (ASM) contacts. The care manager spent a mean of 157 ± 104 minutes of direct telephone time per intervention subject. At least 1 care manager and 1 ASM contact occurred in 196 and 185 of the intervention subjects, respectively, and ≥ 5 care manager and ≥ 10 ASM contacts each occurred in 165 subjects. The inter-subject variability in nurse and ASM contacts was due to death early drop-out by some intervention patients and extra contacts required for others. The 154 intervention patients enrolled for depression were on antidepressants a mean of 5.4 ± 5.2 months, with 89 (58%) on an antidepressant ≥ 3 months. The 137 intervention patients enrolled for pain were on opioid medication a mean of 4.0 ± 5.1 months, with 66 (48%) on ≥ 1 month. The care manager coordinated a pain-specific referral for 12 patients and a mental health referral for 11 patients.

DISCUSSION

Our INCPAD trial has several important findings. First, the telecare management intervention resulted in significant improvements in both pain and depression. Second, the trial demonstrated that it is feasible to provide telephone-based centralized symptom management across multiple geographically dispersed community-based practices in both urban and rural areas by coupling human with technology-augmented patient interactions. Third, the findings did not appear to be confounded by differential rates of co-interventions or health care use.

The moderate effect sizes and improvement rates for pain in INCPAD were comparable to those found in recent collaborative care interventions for pain20 as well as pain with comorbid depression.21 Although several recent trials demonstrated somewhat greater improvements in depression at 12 months than those produced by our INCPAD intervention,53–55 these trials enrolled fewer patients with advanced cancer and delivered more intensive depression treatment including in-person visits and psychotherapy. Telephone-based psychotherapy can be effectively delivered 56 and might augment the optimized medication intervention provided in INCPAD.

Our study has several limitations. First, our sample included a wide range of cancer types and phases. This increases the generalizability of our findings to real-world practice but precludes more precise estimates of treatment effective in specific types or stages of cancer. Second, the lack of electronic medical records in most of the community-based practices resulted in a less complete assessment of pain- and depression-specific treatments in the control group. Third, an economic analysis might further strengthen the case for dissemination. To this end, we are currently integrating self-report measures of health care use and work productivity with hospital data to better clarify the cost-effectiveness of the INCPAD intervention.

The fact that INCPAD was beneficial for the most common physical and psychological symptoms in cancer patients demonstrates that a collaborative care intervention can cover several conditions, both physical and psychological. In 3 trials involving 796 cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy Givens et al showed that a nurse-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) intervention improved physical symptom burden.57–59 The model was more disease management rather than collaborative care in that the nurse worked with the patient independent of the oncology practice. Such interventions may be strengthened by closer integration with practices.60 Combining the collaborative care approach and physician-nurse team that facilitated optimized medication management in INCPAD with the nurse-administered CBT and symptom self-management approach tested by Givens might provide an even more effective way to manage multiple cancer-related symptoms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledgement the nurse care management provided by Becky Sanders and Susan Schlundt and the research assistance provided by Stephanie McCalley and Pam Harvey. These individuals were compensated as study personnel

Funding/Support: This work was supported by grant R01 CA-115369 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. Dr. Kroenke was the principal investigator.

Role of the Sponsor: The sponsor provided financial support for the study only and had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the study; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute to Dr. Kroenke (R01 CA-115369)

Footnotes

Trial Registration clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00313573

Author Contributions: Drs. Kroenke had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Kroenke, Theobald, Carpenter, Morrison

Acquisition of data: Kroenke, Theobald, Norton

Analysis and interpretation of data: Kroenke, Wu, Tu, Theobald, Carpenter, Morrison,

Drafting of the manuscript: Kroenke, Wu, Tu

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Kroenke, Wu, Tu, Theobald, Carpenter, Morrison, Norton

Statistical analysis: Kroenke, Wu, Tu.

Obtained funding: Kroenke.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Kroenke, Theobald, Norton

Study supervision: Kroenke, Theobald, Norton

Financial Disclosures. Dr. Kroenke has received research funding from Eli Lilly and Pfizer, and honoraria as a speaker, consultant, or advisory board member from Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Forest Laboratories. No other authors reported disclosures.

References

- 1.Carr D, Goudas L, Lawrence D, et al. AHRQ Publication No. 02-E032. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2002. Management of cancer symptoms: Pain, depression, and fatigue. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 61 (Prepared by the New England Medical Center Evidence-based Practice Center under contract No 290-97-0019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bottomley A. Depression in cancer patients: a literature review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 1998;7:181–191. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.1998.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caraceni A, Portenoy RK. An international survey of cancer pain characteristics and syndromes. IASP Task Force on Cancer Pain. International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain. 1999;82:263–274. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Portenoy RK, Lesage P. Management of cancer pain. Lancet. 1999;353:1695–1700. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Given CW, Given B, Azzouz F, Kozachik S, Stommel M. Predictors of pain and fatigue in the year following diagnosis among elderly cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21:456–466. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Given CW, Given BA, Stommel M. The impact of age, treatment, and symptoms on the physical and mental health of cancer patients. A longitudinal perspective. Cancer. 1994;74:2128–2138. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19941001)74:7+<2128::aid-cncr2820741721>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Stommel M, Given CW, Given B. Predictors of depressive symptomatology of geriatric patients with colorectal cancer: a longitudinal view. Support Care Cancer. 2002;10:494–501. doi: 10.1007/s00520-001-0338-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Stommel M, Given CW, Given B. Physical functioning and depression among older persons with cancer. Cancer Pract. 2001;9:11–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.91004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Stommel M, Given CW, Given B. The influence of symptoms, age, comorbidity and cancer site on physical functioning and mental health of geriatric women patients. Women Health. 1999;29:1–12. doi: 10.1300/J013v29n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stommel M, Given BA, Given CW. Depression and functional status as predictors of death among cancer patients. Cancer. 2002;94:2719–2727. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fallowfield L, Ratcliffe D, Jenkins V, Saul J. Psychiatric morbidity and its recognition by doctors in patients with cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1011–1015. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Passik SD, Dugan W, McDonald MV, Rosenfeld B, Theobald DE, Edgerton S. Oncologists’ recognition of depression in their patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1594–1600. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharpe M, Strong V, Allen K, et al. Major depression in outpatients attending a regional cancer centre: screening and unmet treatment needs. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:314–320. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, et al. Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:592–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403033300902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cleeland CS. Undertreatment of cancer pain in elderly patients. JAMA. 1998;279:1914–1915. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.23.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314–2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams JW, Jr, Gerrity M, Holsinger T, Dobscha S, Gaynes B, Dietrich A. Systematic review of multifaceted interventions to improve depression care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:91–116. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams LS, Kroenke K, Bakas T, et al. Care management of post-stroke depression: a randomized controlled trial. Stroke. 2007;38:998–1003. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000257319.14023.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rollman BL, Belnap BH, LeMenager MS, et al. Telephone-delivered collaborative care for treating post-CABG depression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:2095–2103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobscha SK, Corson K, Perrin NA, et al. Collaborative care for chronic pain in primary care: a clustered randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1242–1252. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Damush TM, et al. Optimized antidepressant therapy and pain self-management in primary care patients with depression and musculoskeletal pain: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:2099–2110. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroenke K, Theobald D, Norton K, et al. Indiana Cancer Pain and Depression (INCPAD) Trial: design of a telecare management intervention for cancer-related symptoms and baseline characteristics of enrolled participants. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:240–253. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new depression and diagnostic severity measure. Psychiatric Annals. 2002;32:509–521. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cleeland CS. Pain assessment in cancer. In: Osoba D, editor. Effect of Cancer on Quality of Life. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 293–305. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams LS, Jones WJ, Shen J, Robinson RL, Kroenke K. Outcomes of newly referred neurology outpatients with depression and pain. Neurology. 2004;63:674–677. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000134669.05005.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. A six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40:771–781. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroenke K, West SL, Swindle R, et al. Similar effectiveness of paroxetine, fluoxetine, and sertraline in primary care: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2001;286:2947–2955. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.23.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:1109–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cleeland CS. Measurement of pain by subjective report. In: Foley KM, editor. Advances in Pain Research and Therapy. 1989. pp. 391–403. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cuijpers P, Smits N, Donker T, ten Have M, de Graaf R. Screening for mood and anxiety disorders with the five-item, the three-item, and the two-item Mental Health Inventory. Psychiatry Res. 2009;168:250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kroenke K, Bair M, Damush T, et al. Stepped Care for Affective Disorders and Musculoskeletal Pain (SCAMP) study Design and practical implications of an intervention for comorbid pain and depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:506–517. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Unutzer J, Williams JW, Callahan CM, et al. Improving primary care for depression in late life: the design of a multicenter randomized trial. Med Care. 2001;39:785–799. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Monahan PO, Lowe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11 (Suppl 3):89–95. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner EH, LaCroix AZ, Grothaus LC, Hecht JA. Responsiveness of health status measures to change among older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41:241–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb06700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, Werner J, Duan N. Improving depression outcomes in community primary care practice: a randomized trial of the quEST intervention. Quality Enhancement by Strategic Teaming. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:143–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cintron A, Morrison RS. Pain and ethnicity in the United States: A systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1454–1473. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lesser IM, Castro DB, Gaynes BN, et al. Ethnicity/race and outcome in the treatment of depression: results from STAR*D. Med Care. 2007;45:1043–1051. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181271462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1905–1917. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.NCCN Practice Guidelines in Oncology - v.1.2004. 2004. Cancer Pain Version 1.2004. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bookbinder M, Coyle N, Kiss M, et al. Implementing national standards for cancer pain management: program model and evaluation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1996;12:334–347. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Technical report series 804. 2. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. Report of the WHO Expert Committee on Cancer Pain Relief and Active Supportive Care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pain Management Part 4 Cancer Pain and End-of-Life Care. American Medical Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keller MB. Past, present, and future directions for defining optimal treatment outcome in depression: remission and beyond. JAMA. 2003;289:3152–3160. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9:105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mallinckrodt CH, Clark WS, David SR. Type I error rates from mixed effects model repeated measures versus fixed effects ANOVA with missing values imputed via last observation carried forward. Drug Information J. 2001;35:1215–1225. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kazis LE, Anderson JJ, Meenan RF. Effect sizes for interpreting changes in health status. Med Care. 1989;27:S178–S189. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fann JR, Fan MY, Unutzer J. Improving primary care for older adults with cancer and depression. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24 (Suppl 2):S417–S424. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0999-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ell K, Xie B, Quon B, Quinn DI, Dwight-Johnson M, Lee PJ. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4488–4496. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Strong V, Waters R, Hibberd C, et al. Management of depression for people with cancer (SMaRT oncology 1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;372:40–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60991-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Tutty S, Operskalski B, Von Korff M. Telephone psychotherapy and telephone care management for primary care patients starting antidepressant treatment: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:935–942. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Given C, Given B, Rahbar M, et al. Effect of a cognitive behavioral intervention on reducing symptom severity during chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:507–516. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sherwood P, Given BA, Given CW, et al. A cognitive behavioral intervention for symptom management in patients with advanced cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:1190–1198. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.1190-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sikorskii A, Given CW, Given B, et al. Symptom management for cancer patients: a trial comparing two multimodal interventions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coleman K, Mattke S, Perrault PJ, Wagner EH. Untangling practice redesign from disease management: how do we best care for the chronically ill? Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:385–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.