Abstract

Thiopurines are effective immunosuppressants and anti-cancer agents. However, the long-term use of thiopurines was found to be associated with a significantly increased risk of various types of cancer. To date, the specific mechanism(s) underlying the carcinogenicity associated with thiopurine treatment remain(s) unclear. Herein, we constructed duplex pTGFP-Hha10 shuttle vectors carrying a 6-thioguanine (SG) or S6-methylthioguanine (S6mG) at a unique site and allowed the vectors to propagate in three different human cell lines. Analysis of the replication products revealed that, while neither thionucleoside blocked considerably DNA replication in any of the human cell lines, both SG and S6mG were mutagenic, resulting in G→A mutation at frequencies of ~8% and ~39%, respectively. Consistent with what was found from our previous study in E. coli cells, our data demonstrated that the mutagenic properties of SG and S6mG provided significant evidence for mutation induction as a potential carcinogenic mechanism associated with chronic thiopurine intervention.

Since the approval of the thiopurine drugs by FDA in the 1950s, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, and 6-thioguanine (SG) have been extensively used as anticancer and immunosuppressive agents for over half a century (1). Azathioprine is widely used as an immunosuppressive agent in organ transplantation and for treating autoimmune disease (2, 3). As a prodrug, azathioprine is converted efficiently (~90%) to 6-mercaptopurine from attack by sulfhydryl-containing compounds such as glutathione and cysteine after oral administration and absorption (1). 6-Mercaptopurine, a prescribed anticancer drug, is commonly used for acute lymphoblastic leukemia treatment (4, 5). SG is the ultimate active metabolite of all thiopurine prodrugs and it can be converted to SG nucleotides and incorporated into nucleic acids (1, 6).

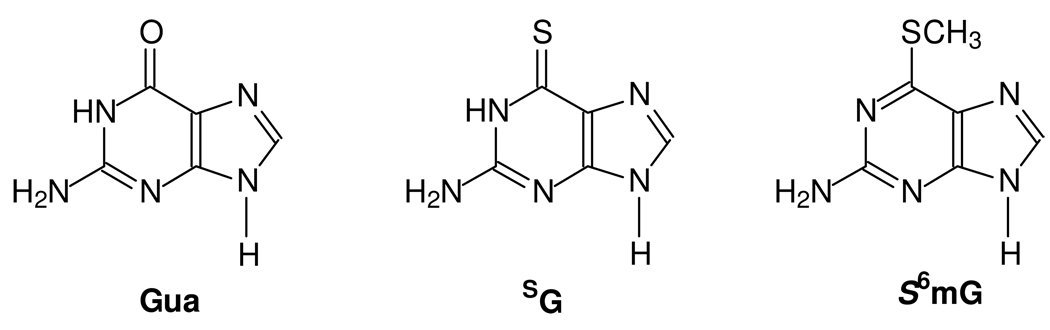

Some studies have been carried out toward understanding the molecular mechanisms of action of the thiopurine drugs. Along this line, it was found that azathioprine and its metabolites could induce apoptosis in human T cells (7). The induction of apoptosis requires co-stimulation with CD28 and is mediated by specific blockade of Rac1 activation through binding of 6-thioguanosine triphosphate (SGTP) in lieu of GTP (7). Although the molecular mechanisms for the anticancer activity of the thiopurine drugs remain unclear, it was observed that DNA SG could be spontaneously methylated by S-adenosyl-L-methionine (S-AdoMet) to afford S6mG (Figure 1), which may trigger the mismatch repair pathway and induce cell death through futile cycles of repair synthesis (8).

Figure 1. The structures of guanine (Gua), 6-thioguanine (SG) and S6-methylthioguanine (S6mG).

A major concern for thiopurine therapy is a high occurrence of certain cancers in long-term survivors of these patients following the drug treatment (9–15). Azathioprine has been shown to be genotoxic and classified as a human carcinogen because of its associated caner risk (16). To date, the specific mechanism(s) underlying the in-vivo carcinogenicity of thiopurines remain(s) unclear.

Our recent study showed that both SG and S6mG are mutagenic in E. coli cells and could lead to G→A mutation at frequencies of 10% and 94%, respectively (17). We also carried out the measurement of the level of 6-thio-2′-deoxyguanosine (SdG) and S6-methylthio-2′-deoxyguanosine (S6mdG) in genomic DNA in four SG-treated human leukemia cell lines by employing a sensitive HPLC coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method (18). Our results revealed that, upon treatment with 3 µM SG for 24 h, approximately 10, 7.4, 7, and 3% of guanine in genomic DNA was replaced with SG in Jurkat T, HL-60, CCRF-CEM and K-562 cells, respectively (18). In addition, a small percentage of the DNA SG was observed to be methylated to S6mG (18). Therefore, the mutation induced by the SG and S6mG in DNA may contribute to the carcinogenic effects of thiopurines. However, it remains undefined whether the mutagenic properties of the two mercaptopurine derivatives found in E. coli cells can be observed in human cells because human cells are equipped with a more intricate DNA replication machinery than prokaryotic cells. In addition, it would certainly be more significant to investigate the cytotoxic and mutagenic properties of these thiopurine nucleosides in human cells because of the increased occurrence of cancers in humans receiving the thiopurine drugs.

In the present study, we investigated the mutagenic and cytotoxic properties of the two thiopurine derivatives in human cells by developing a novel shuttle vector-based method with the use of double-stranded plasmids containing a SG or S6mG at a defined site. We first synthesized a 17-mer SG-containing oligodeoxyribonucleotide (ODN) 5’-GCGCAAASGCTAGAGCTC-3’. SG in ODNs can be selectively methylated to S6mG by treatment with methyl iodide (CH3I) in a phosphate buffer (pH 8.5) (19). We employed similar procedures and isolated the desired S6mG-containing ODN from the reaction mixtures by HPLC. The identities of these thionucleoside-bearing ODNs were confirmed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analyses (Figures S1 and S2).

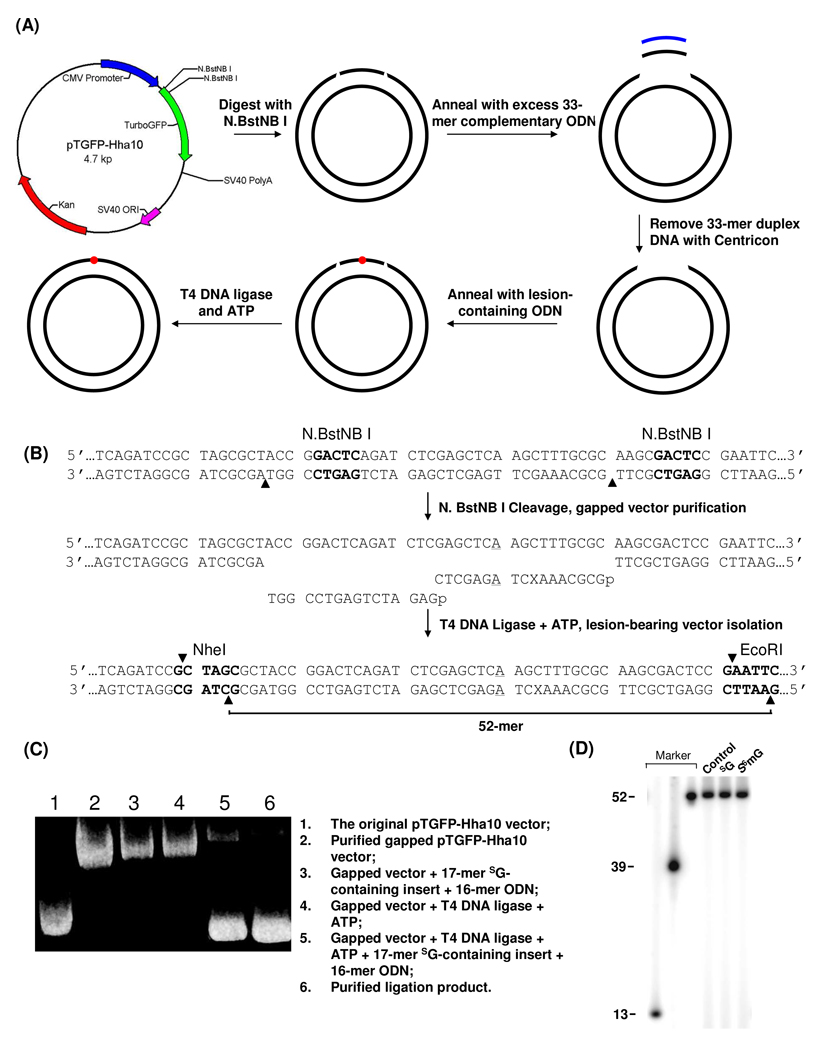

We next constructed double-stranded pTGFP-Hha10 vectors housing a SG or S6mG (Figure 2A). The pTGFP-Hha10 plasmid harbors two unique N.BstNB I recognition sites and this restriction enzyme nicks only one strand of duplex DNA at the 4th nucleotide 3’ to the GAGTC restriction recognition site (Figure 2B) (20). The resulting 33mer single-stranded ODN can be removed from the nicked plasmid by annealing the cleavage mixture with its complementary ODN in 50-fold molar excess. The gapped plasmid was isolated, ligated with a 5’-phosphorylated 17-mer lesion-carrying insert and a 16-mer unmodified ODN, and the resulting lesion-carrying double-stranded plasmid was isolated from the mixture by using agarose gel electrophoresis (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Method for the construction of lesion-containing duplex vector.

(A) A schematic diagram showing the procedures for the preparation of the lesion-containing plasmid. See Materials and Methods for details. (B) Enzymatic digestion and ligation for the insertion of SG- or S6mG-carrying ODN into gapped pTGFP-Hha10 vector. ‘X’ represents guanine, SG or S6mG, and the A:A mismatch site is underlined. The restriction recognition sites are highlighted in bold and cleavage sites are indicated by solid triangles. (C) Agarose (1%) gel electrophoresis for monitoring the processes for the construction of the SG-bearing pTGFP-Hha10 vector. (D) Restriction digestion and post-labeling for assessing the integrity of the control and lesion-containing vectors (see text).

Constructing a lesion-bearing plasmid is among the most challenging steps when a double-stranded shuttle vector is employed for in-vivo replication experiments. However, the use of the pTGFP-Hha10 vector allows for the facile preparation of the lesion-containing plasmid because the ligation only necessitates the insertion of a single-stranded damage-containing ODN into a gapped double-stranded vector. As depicted in Figure 2C, the above-described strategy facilitated the efficient generation of lesion-containing double-stranded vector, and agarose gel electrophoresis afforded convenient purification of the resulting double-stranded vector from the ligation mixture (Figure 2C); we could routinely produce the SG- and S6mG-containing pTGFP-Hha10 vectors at an overall yield of ~30%.

We further confirmed the incorporation of the lesion-containing insert by employing a restriction digestion/post-labeling assay. In this experiment, the aforementioned double-stranded genomes were digested with EcoR I (the unique EcoR I site is shown in Figure 2B). The nascent terminal phosphate groups were removed by using alkaline phosphatase, and the 5’-termini were subsequently re-phosphorylated with [γ-32P]ATP. The linearized vector was further cleaved with Nhe I (the unique Nhe I site is shown in Figure 2B), which affords a 52-mer lesion-containing ODN if the ligation is successful (Figure 2B). Indeed denaturing PAGE analysis revealed a distinct 52-mer 32P-labeled fragment, and no shorter fragments could be detected (Figure 2D), supporting the successful incorporation of the 17-mer lesion-containing insert and the 16-mer unmodified ODN into the gapped construct.

When the lesion-containing double-stranded shuttle vector is replicated in mammalian cells, the undamaged strand may be preferentially replicated over the lesion-carrying strand (21, 22), rendering it difficult to determine accurately the mutation frequencies. To overcome this difficulty, we employed a similar strategy as reported by Moriya et al. (21, 22) and incorporated an A:A mismatch three nucleotides away from the lesion site (Figure 2B and Figure 3A). This method facilitated the independent assessment of the products arising from the replication of the lesion-containing strand and its opposing unmodified strand (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Determination of the bypass efficiencies and mutation frequencies of SG or S6mG.

(A) Restriction digestion of PCR products of progeny genome arising from in-vivo replication of SG- and S6mG-bearing genomes in mammalian cells. The PCR fragments were digested with SacI, and the nascent terminal phosphate groups in the resulting DNA fragments were removed by shrimp alkaline phosphatase. The 5’ termini were subsequently labeled with [γ-32P]ATP, and the resulting DNA fragments were further digested with FspI and resolved on a 30% denaturing PAGE gel. (B) Denaturing PAGE for assessing the bypass efficiencies and mutation frequencies of SG and S6mG in 293T, GM00627 and GM04429 cells.

We next asked how the presence of SG and S6mG compromises DNA replication. The lesion-containing and the control lesion-free vectors were transfected separately into 293T human kidney epithelial cells. To assess whether nucleotide excision repair is involved with the repair of SG and S6mG, we also evaluated the replication of the lesion-carrying and control lesion-free vectors in SV40-transformed XPA-deficient (GM04429) and repair-proficient (GM00627) human fibroblast cells. The pTGFP-Hha10 vector contains an SV40 origin, which allows the vector to be replicated in the SV40-transformed cells. The isolated progeny vectors from the host cells were digested with Dpn I to remove the residual unreplicated vectors prior to PCR amplification; thus, only the progeny vectors can be amplified by PCR. The bypass efficiencies and mutation frequencies of these modified nucleosides were assessed by using the modified REAP assay (Figure 3) (17, 23).

In the absence of deletion mutation, restriction digestion of the PCR products of the progeny genome emanating from in-vivo replication affords a 10-mer fragment harboring the site where the SG or S6mG was initially incorporated (Figure 3). The failure to detect radio-labeled fragments with lengths shorter than 10-mer supports that neither thiopurine derivative gives rise to deletion mutations (Figure 3). In this context, we employed 30% (19:1, acrylamide:bisacrylamide) denaturing polyacrylamide gels containing 5 M urea to resolve the 32P-labeled fragments and it turned out that the 10-mers with a single nucleotide difference can be resolved from each other (Figure 3B).

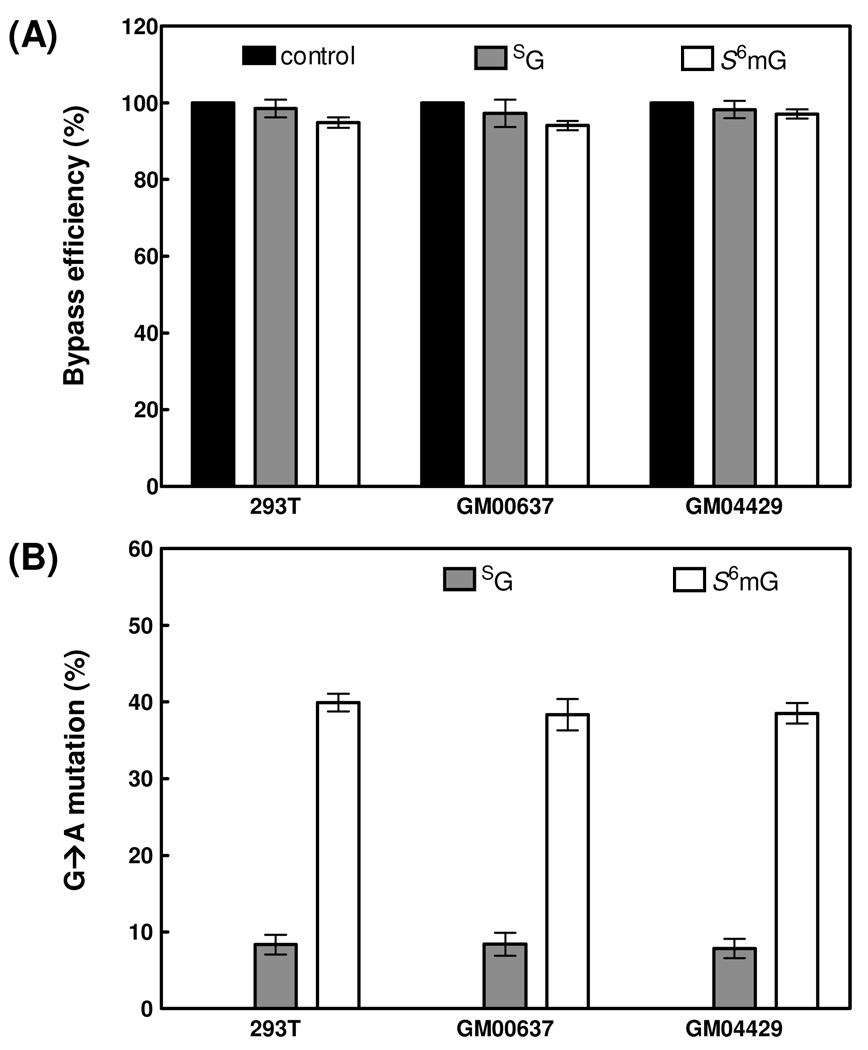

The bypass efficiencies were calculated from the ratio of the combined intensities of bands for the 10-mer products from the replication of the lesion-bearing bottom-strand over the intensity of the band for the 10-mer product from the replication of the lesion-free top-strand. The bypass efficiencies for the lesion-carrying genomes were then normalized against that for the control lesion-free genome. Our results revealed that neither SG nor S6mG is a strong block to DNA replication in human 293T cells, and the bypass efficiencies for SG and S6mG are approximately 98% and 95%, respectively. In addition, deficiency in NER factor XPA does not affect appreciably the bypass efficiencies for these thionucleosides when we compared the bypass efficiencies of SG and S6mG in GM00637 and GM04429 cell lines (Figure 4A). These data suggest that NER is not involved in the repair of SG or S6mG in human cells.

Figure 4. Bypass efficiencies (A) and mutation frequencies (B) of guanine, SG and S6mG in 293T, GM00627 and GM04429 cells.

Black, gray and white columns represent the results for substrates carrying guanine, SG and S6mG, respectively. The data represent the means and standard deviations of results from three independent transfection experiments.

The results from denaturing PAGE analysis also allowed us to measure the mutation frequencies of SG and S6mG in human cells with the restriction endonuclease and postlabeling (REAP) assay (24, 25). The mutation frequencies were calculated from the ratio of the intensity of the band for the 10-mer mutated product over the combined intensities of bands for the 10-mer products from the replication of the lesion-bearing bottom-strand. The quantification data showed that S6mG are highly mutagenic in human 293T cells and in human fibroblast cells that are XPA-deficient or repair-proficient, with G→A transition occurring at frequencies of 40%, 39% and 38%, respectively. The presence of SG also results in G→A transition mutation at a frequency of ~8% in all three cell lines. Thus, deficiency in NER did not confer significant alteration in the mutation frequencies for the replication of the two thionucleosides (Figure 4B).

We also employed LC-MS/MS for interrogating the restriction fragments (Figure 3) (17, 23, 26, 27). In this respect, the restriction digestion mixture was analyzed by LC-MS/MS and we monitored the fragmentation of the [M – 4H]4− ions of d(GCAAAMCTAGAGCT), where “M” is an A, T, C or G. It turned out that only d(GCAAAGCTAGAGCT) and d(GCAAAACTAGAGCT) could be detected in the digestion mixtures for samples arising from the in-vivo replication of SG- and S6mG-containing substrates, which is in line with what we found from PAGE analysis (LC-MS/MS results are shown in Figure S3).

The observation that SG can induce a high frequency of G→A mutation supports that the presence of SG in DNA can introduce SG:T base pair, which may trigger the post-replicative mismatch repair (MMR) pathway. Along this line, it was observed that the SG:T base pair can be recognized by mammalian MMR factors to a similar extent as a G:T mispair (28). Recently we observed that, upon a 24-h treatment with 3 µM SG, ~3–10% of guanine was replaced with SG in 4 different leukemic cell lines; however, less than 0.02% of SdG was converted to S6mdG in the above cell lines (18). These results, in conjunction with the observation that the S6mG:T mispair can be recognized less efficiently than the SG:T mispair by MMR factors (28, 29), suggest that SG can exert its cytotoxic effect by triggering the post-replicative MMR pathway without being converted to S6mG. A direct SG-associated cytotoxicity could be a reason that thiopurine drugs have had success as anti-leukemic agents.

Long-term immunosuppression with azathioprine in organ transplant patients is associated with an increased risk of certain types of cancer (9–15), and azathioprine has been designated as a human carcinogen (16). Although other factors may also contribute to the carcinogenic effect, it is reasonable to believe that the mutagenic properties of SG and S6mG in human cells, as observed in the current study, may play a significant role in the carcinogenicity of thiopurine drugs. Viewing the extremely low frequency of conversion of SG to S6mG in genomic DNA (18), it is very likely that the mutagenic effect of the thiopurine drugs arises predominantly from the mutagenic bypass of SG in DNA. In this context, it is of note that in the current study we employed a shuttle vector to evaluate the mutagenic properties of SG and S6mG, where the replication across SG and S6mG occurs extra-chromosomally; this may differ, to some extent, from the replication of these nucleobases when present in genomic DNA.

Lastly, it is important to note that the modified version of the REAP assay developed in the present study may be generally applicable to examine the cytotoxic and mutagenic properties of other DNA lesions in mammalian cells.

Materials and Methods

Unmodified ODNs used in this study were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). [γ-32P]ATP was obtained from Perkin Elmer (Piscataway, NJ). The phosphoramidite building block of 6-thio-2’-deoxyguanosine was obtained from Glen Research (Sterling, VA). Shrimp alkaline phosphatase was from USB Corporation (Cleveland, OH), and all other enzymes were from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) was purchased from TCI America (Portland, OR). Chemicals unless otherwise noted were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The 293T cells (HEK 293T/17) were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). The XPA (xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group A)-deficient (GM04429) and repair-proficient human fibroblast cells (GM00627) were kindly provided by Prof. Gerd P. Pfeifer.

The detailed experimental procedures are described in the Supporting Information. Briefly, the lesion-containing genomes were constructed by inserting a 17-mer SG- or S6mG-bearing ODN into a gapped pTGFP-Hha10 vector via enzymatic ligation. The lesion-carrying and the control lesion-free genomes were transfected separately into cultured human cells. After in-vivo replication for 24 h, the progeny vectors were isolated, digested with DpnI to remove the residual unreplicated parent vector, amplified by PCR, and the PCR products were digested with restriction enzymes. The restriction fragments were selectively labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and resolved on polyacrylamide gels to determine the bypass efficiencies and mutation frequencies (Figure 3). The restriction fragments were also subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis to identify unambiguously the replication products.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Prof. Gerd P. Pfeifer (The City of Hope) for kindly providing us the XPA-deficient (GM04429) and repair-proficient human fibroblast cells (GM00627) and Mr. David Baker for technical assistance in plasmid construction. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK082779).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Detailed experimental procedures, ESI-MS and MS/MS results. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Elion GB. The purine path to chemotherapy. Science. 1989;244:41–47. doi: 10.1126/science.2649979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease (1) N. Engl. J. Med. 1991;325:928–937. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199109263251306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Present DH, Korelitz BI, Wisch N, Glass JL, Sachar DB, Pasternack BS. Treatment of Crohn's disease with 6-mercaptopurine. A long-term, randomized, double-blind study. N. Engl. J. Med. 1980;302:981–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198005013021801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pui CH, Evans WE. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339:605–615. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808273390907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pui CH, Jeha S. New therapeutic strategies for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:149–165. doi: 10.1038/nrd2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lepage GA. Basic biochemical effects and mechanism of action of 6-thioguanine. Cancer Res. 1963;23:1202–1206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tiede I, Fritz G, Strand S, Poppe D, Dvorsky R, Strand D, Lehr HA, Wirtz S, Becker C, Atreya R, Mudter J, Hildner K, Bartsch B, Holtmann M, Blumberg R, Walczak H, Iven H, Galle PR, Ahmadian MR, Neurath MF. CD28-dependent Rac1 activation is the molecular target of azathioprine in primary human CD4+ T lymphocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:1133–1145. doi: 10.1172/JCI16432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swann PF, Waters TR, Moulton DC, Xu YZ, Zheng Q, Edwards M, Mace R. Role of postreplicative DNA mismatch repair in the cytotoxic action of thioguanine. Science. 1996;273:1109–1111. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtis RE, Metayer C, Rizzo JD, Socie G, Sobocinski KA, Flowers ME, Travis WD, Travis LB, Horowitz MM, Deeg HJ. Impact of chronic GVHD therapy on the development of squamous-cell cancers after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: an international case-control study. Blood. 2005;105:3802–3811. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Offman J, Opelz G, Doehler B, Cummins D, Halil O, Banner NR, Burke MM, Sullivan D, Macpherson P, Karran P. Defective DNA mismatch repair in acute myeloid leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome after organ transplantation. Blood. 2004;104:822–828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindelof B, Sigurgeirsson B, Gabel H, Stern RS. Incidence of skin cancer in 5356 patients following organ transplantation. Br. J. Dermatol. 2000;143:513–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kandiel A, Fraser AG, Korelitz BI, Brensinger C, Lewis JD. Increased risk of lymphoma among inflammatory bowel disease patients treated with azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine. Gut. 2005;54:1121–1125. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.049460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maddox JS, Soltani K. Risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer with azathioprine use. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1425–1431. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Relling MV, Rubnitz JE, Rivera GK, Boyett JM, Hancock ML, Felix CA, Kun LE, Walter AW, Evans WE, Pui CH. High incidence of secondary brain tumours after radiotherapy and antimetabolites. Lancet. 1999;354:34–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)11079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Euvrard S, Kanitakis J, Claudy A. Skin cancers after organ transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1681–1691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grosse Y, Baan R, Straif K, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Galichet L, Cogliano V. A review of human carcinogens-Part A: pharmaceuticals. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:13–14. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(08)70286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan B, Wang Y. Mutagenic and cytotoxic properties of 6-thioguanine, S6-methylthioguanine, and guanine-S6-sulfonic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:23665–23670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804047200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Wang Y. LC-MS/MS coupled with stable isotope dilution method for the quantification of 6-thioguanine and S6-methylthioguanine in genomic DNA of human cancer cells treated with 6-thioguanine. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:5797–5803. doi: 10.1021/ac1008628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu Y. Post-synthetic introduction of labile functionalities onto purine residues via 6-methylthiopurines in oligodeoxyribonucleotides. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:10737–10750. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker DJ, Wuenschell G, Xia L, Termini J, Bates SE, Riggs AD, O'Connor TR. Nucleotide excision repair eliminates unique DNA-protein cross-links from mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:22592–22604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levine RL, Yang IY, Hossain M, Pandya GA, Grollman AP, Moriya M. Mutagenesis induced by a single 1,N6-ethenodeoxyadenosine adduct in human cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4098–4104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang I-Y, Johnson F, Grollman AP, Moriya M. Genotoxic mechanism for the major acrolein-derived deoxyguanosine adduct in human cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2002;15:160–164. doi: 10.1021/tx010123c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuan B, Cao H, Jiang Y, Hong H, Wang Y. Efficient and accurate bypass of N2-(1-carboxyethyl)-2’-deoxyguanosine by DinB DNA polymerase in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:8679–8684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711546105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delaney JC, Essigmann JM. Context-dependent mutagenesis by DNA lesions. Chem. Biol. 1999;6:743–753. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)80021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delaney JC, Essigmann JM. Assays for determining lesion bypass efficiency and mutagenicity of site-specific DNA lesions in vivo. Methods Enzymol. 2006;408:1–15. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)08001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong H, Cao H, Wang Y. Formation and genotoxicity of a guanine cytosine intrastrand cross-link lesion in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7118–7127. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuan B, Jiang Y, Wang Y. Efficient formation of the tandem thymine glycol/8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine lesion in isolated DNA and the mutagenic and cytotoxic properties of the tandem lesions in Escherichia coli cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2010;23:11–19. doi: 10.1021/tx9004264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffin S, Branch P, Xu YZ, Karran P. DNA mismatch binding and incision at modified guanine bases by extracts of mammalian cells: implications for tolerance to DNA methylation damage. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4787–4793. doi: 10.1021/bi00182a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waters TR, Swann PF. Cytotoxic mechanism of 6-thioguanine: hMutSα, the human mismatch binding heterodimer, binds to DNA containing S6-methylthioguanine. Biochemistry. 1997;36:2501–2506. doi: 10.1021/bi9621573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.