Abstract

Turning point, a key concept in the developmental life course approach, is currently understudied in the field of substance abuse, but merits further research. A turning point often involves a particular event, experience, or awareness that results in changes in the direction of a pathway or persistent trajectory over the long-term. This article (1) provides an overview of the relevant literature on the concept of turning points from the life course and developmental criminology perspectives, (2) reviews literature on turning points in substance use, (3) discusses methodological considerations, and (4) suggests areas for future research on turning points in drug use. The influence of life course concepts related to drug use trajectories and turning points (including, for example, timing and sequencing of life events, individual characteristics, human agency, and social and historical context) offers a potentially fruitful area of investigation that may increase our understanding of why and how drug users stop and resume using over the long-term. Further research on turning points may be particularly valuable in unpacking the multifaceted and complex underlying mechanisms and factors involved in lasting changes in drug use.

Keywords: turning points, substance use, life course

INTRODUCTION

Illicit drug use continues to be a topic of public concern, directly or indirectly affecting individuals, families, and communities, with detrimental effects that may persist across generations. It is now widely accepted that addiction is a chronic and recurring condition [1], oftentimes spanning decades of an individual’s lifetime [2]. As such, focus has increasingly turned toward embracing long-term care and continuity of care models for understanding and treating drug addiction [2–4]. It naturally follows that drug abuse research must also involve a longer-term perspective. Further, most drug abusers have frequent and repeated encounters with social, health service, and criminal justice systems. Thus, a life course perspective using a more holistic, integrated, or systems approach to studying substance abuse, which takes into account varied and multiple factors that might contribute toward abstinence, persistence, or relapse, may be helpful given the complex nature of drug abuse and its dynamic interplay with various social systems [2]. The approach complements the shift in the treatment and research paradigms from short-term or episodic substance use and treatment to longer-term developmental patterns of behavior and outcomes over time, and takes into consideration factors that may shape or be shaped by these pathways.

Turning point, a key concept in the life course approach may be particularly beneficial in the study of changes in drug use behaviors within varying contexts (e.g., environmental, developmental stage in life) and over the life span. How and why do individuals stop and resume using drugs, particularly when such changes result in the redirection of a pathway or a persistent trajectory? Answers to these questions will have important implications for treatment and relapse prevention strategies. The purpose of this article is to (1) provide an overview of the relevant literature on the concept of turning points from the life course and developmental criminology perspectives, including definitions of terms and a description of factors contributing to turning points (e.g., life events and experiences, developmental stages, environmental context, individual attributes), (2) review literature on turning points in substance use, (3) discuss methodological considerations in examining turning points, and (4) suggest areas for future research on turning points in drug use.

Turning Points

“Turning point” is a commonly used term. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language [5] defines a turning point as “the point at which a very significant change occurs; a decisive moment.” As will be shown in our literature review, while the concept of turning points has been used in many studies, what constitutes a turning point and the best way to identify and measure it is not a simple or definitive matter [6, 7]. In this paper, our focus will be on turning point as “an alteration or deflection in a long-term pathway or trajectory that was initiated at an earlier point in time” [8] (p.16), distinguishing it from a temporary change or mere fluctuation in behaviors. We are interested in understanding turning points that redirect trajectories, not simply temporary detours from life pathways [7].

Turning points often involve particular events, experiences, or awareness that result in changes in the direction of a pattern or trajectory over the long term. Understanding turning points may be particularly valuable in providing insight into the complicated underlying processes involved in long-term changes in drug use and reveal why, for instance, the same life event (e.g., obtaining employment, becoming a parent) constitutes a turning point leading to a marked increase or decrease in drug use for some, but not for others.

TURNING POINTS FROM THE LIFE COURSE PERSPECTIVE

Turning points is a key concept in the life course approach, which emphasizes long-term developmental patterns of continuity and change in relation to transitions in terms of social roles (e.g., parent, employee, drug offender) over the life span [2]. The developmental life course perspective has roots in the social sciences and evolved more recently as developmental criminologists became increasingly interested in using the approach to study criminal careers [9]. Focusing on developmental stages and patterns of behavior across the life span and taking into account individual and environmental factors that may shape these patterns are instrumental in understanding persistence as well as changes in behavior. Key life course concepts involve developmental trajectories, transitions and turning points, and their relationships to one another. Elder [10] defines the life course as the interconnected trajectories as people age. Trajectories are interdependent sequences of events in different life domains (e.g., drug use, criminal justice involvement, health, mental health, employment). In the developmental criminology literature, which offers parallels to drug abuse in terms of focusing on patterns of delinquent behaviors (e.g., criminal activity, illicit drug use) over time, Sampson and Laub [11] refer to trajectories as “long-term patterns and sequences of behavioral transition” (p. 351), which are affected by the degree of social capital (individuals’ interpersonal relations and institutional ties, i.e., to family, work) available to an individual [12]. Transitions are changes in stages or roles (e.g., getting married or divorced, obtaining one’s first job) that are short-term. Some, but not all, transitions lead to turning points that produce long-term behavioral change.

Life Events and Experiences

The term, turning point, has typically been used in association with life events [6], but not all of these events or experiences lead to changes in life trajectories. Marriage, employment, and military service are often cited in the literature as representing turning points in the life course [6, 11–15]. However, only when events “redirect paths,” may they be considered as important turning points in life [10] (p. 35). Further, although some of these events (e.g., marriage, birth of a child) may be perceived or self-perceived as redirecting the life path, it is only with the passing of a period of time that the stability of the redirected pathway can be confirmed. Thus, it is only in hindsight that turning points emerge [7, 16].

For some individuals, turning points may be the result of single dramatic events that bring about abrupt changes [13], while for others, changes are more incremental, occurring gradually over time [17] and accumulate whereby at some point an “epiphany” triggers a decision to radically change one’s life [18]. Life events and experiences may have cumulative and long-range effects, opening up or shutting down future opportunities [7, 17, 19]. For example, having a satisfying job was found to have a positive influence on criminal careers [15, 20–22]. Laub and Sampson [22] suggest that upon becoming married, spouses of criminal justice offenders may exert direct social control, structure, a new sense of identity and meaning in life, and provide social and emotional support, which may put offenders on the path toward desistence. However it occurs, according to Wethington [23], “a turning point involves a fundamental shift in the meaning, purpose, or direction of a person’s life and must include a self-reflective awareness of, or insight into, the significance of the change” (p. 217), which may be prompted by positive or negative, major or minor events, or other experiences. Similarly, turning points may also involve both positive and negative results, and may concern events over which a person has some, little, or no control or choice [19].

While a wide range of experiences and life events (e.g., change in health status, a significant loss, an adversity or experience of personal growth) has been associated with turning points in the life course [24–25], some respondents report not being able to identify any turning points or particularly positive ones [6, 22]. Given the variety of turning point events and evidence that different people have varied responses to the same event, contextual factors and individual characteristics described in the life course literature concerning turning points are particularly important in understanding such marked changes in awareness and behavior.

Developmental Stages

According to life course theory [10], the timing and sequence of developmental transitions across the life span are of consequence because age and social norms are associated with particular age groups (e.g., may influence how the person adapts, and in turn, how that response affects the life pattern). The subjective meaning of an experience and the associated implications (e.g., drug use, crime) may be age-graded and may vary over the life span [12, 26–27]. Individuals are influenced by different things at varied stages in the life course [9, 28], especially as they age and their roles change (e.g., student, employee, spouse, parent, grandparent). For example, military service during the World War II period has been reported as a turning point for men transitioning into young adulthood with respect to their occupation, employment status, job stability, and economic status, regardless of differences in childhood characteristics and socioeconomic background [11]. Elder et al. [13] found that among four longitudinal samples of American men born between 1904 and 1930, the probability of perceiving military service as a turning point in their lives was significantly influenced by entry at a relatively young age. Moreover, in interviewing 60 women in three age cohorts (first interviewed in their early 40s, 50s, and 60s, and then five years later) about their turning points, Leonard and Burns [29] found that overall, the nature of the turning points changed around midlife, and that role transition-related turning points decreased with age, whereas personal growth ones increased. With regard to employment, findings suggest that work is a turning point for older but not younger offenders [15, 20].

Environmental Context–Historical, Cultural, Social

Whether a life event, experience, or new awareness serves as a turning point may also depend, in part, on contextual factors, which are often unpredictable. One of the key notions of the life course approach is the importance of understanding lives within their larger dynamic and complex environment, particularly social, cultural and historical contexts [28, 30]. Historical events (e.g., war, economic downturns) have an impact on families and individuals’ lives [28]. How turning points are interpreted may also be shaped by culture, as norms (e.g., marriage) may vary across cultures.

Further, cultural and racial/ethnic factors (e.g., socioeconomic level) may affect how individuals perceive and experience particular life events (e.g., arrest with the possibility of incarceration), which may trigger turning points that redirect life pathways. Within the life course criminology literature, Laub and Sampson [30] posit that “cumulative continuity and processes of change are likely to interact with race and structural location [in society]” (p. 319). Hareven and Masaoka [31] found cultural differences among American and Japanese cohorts in 1910–1950 in the timing of life transitions and relevant perceptions over the life course.

Social capital can similarly influence a life pathway because personal change does not happen in a vacuum, but is situated within a larger social context (e.g., interpersonal relationships and institutional ties) that can either impede or facilitate such change [32]. As Coleman [33] notes, “social capital is productive, making possible the achievements of certain ends that in its absence would not be possible” (p. 98). Laub and Sampson [30] theorize that these social linkages or informal social controls (e.g., employment) may help explain how changes in adult behavior occur over the life course in that adult social ties create interdependent systems of obligation and restraint and have associated costs and rewards.

Individual Factors

Individual attributes or background characteristics such a human agency and gender, is yet another area that has been reported as influencing turning points in the life course.

Human Agency

The amount of personal choice and control over decision making individuals feel they have shapes their perceptions and the outcomes of life events and transitions [6, 34], and may contribute to the differential effects that the same life event may have on different people. For example, Rönka et al. [6] found that when individuals perceived that they had more personal choice related to the turning point, they evaluated the life event as more positive. Human agency is a key concept in that overall, people appreciate being able to plan and make choices among the options presented in any given situation that affect their lives [26, 28, 34].

Gender

Gender-based differences have been noted in the life course literature. For example, in a study conducted by Rönka et al. [6] among a sample of 283 men and women, the women reported parenthood, health problems of significant others, and moving to another community as turning points more often than men; men regarded work events, military service, and lifestyle changes as turning points more often than women.

TURNING POINTS STUDIED IN SUBSTANCE ABUSE RESEARCH

The concept of turning points in the developmental life course has been an area of growing interest among substance abuse researchers [2, 35], although earlier inquiries into major events or other reasons for quitting substance use may not have been framed from a life course perspective and have not explored the underlying processes and mechanisms contributing to decisions to abstain. Turning points in substance use has evolved to become a separate area of empirical study. Further, with more recent empirical findings uncovering the heterogeneity of life course drug use patterns and frequent interplay with multiple service systems (e.g., criminal justice) and theoretical developments in other disciplines (e.g., criminology, sociology), the life course perspective has become a useful tool that allows a more comprehensive scientific investigation into the complexities of addiction and recovery over the life span [2].

A number of studies examining turning points in substance use were found in the literature. For example, with respect to alcohol use, Kaskutas [36] describes self-reported turning points (e.g., physical symptoms, emotional problems) in seeking help for drinking problems among a sample of 600 women in Women for Sobriety groups in the United States and Canada. In the study, the author operationalized a “turning point” as becoming really aware that the respondent must do something about her drinking. It was noted that on average, it took respondents four years to become sober. Curran et al. [37] found a relationship between becoming married for the first time and a decreasing trend in alcohol use over time among a sample of young adults drawn from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (N=4,052). In a qualitative study by Moneyham and Connor [24] in which eight adult males recruited at a substance abuse treatment program were interviewed in-depth, the turning points that emerged represented changes in the men’s views about themselves and situations in their lives, including a significant loss, changes in health status, and caring relationships. Key life events prompted the men’s readiness to change. Further, Cloud and Granfield [35] reported that among a sample of 46 individuals who overcame their drug and alcohol addiction without treatment, turning points were typically related to experiences involving other people (e.g., death of a father, responsibilities to children), but turning points also included “bottom-hitting” events that made the respondents aware that their addiction was truly problematic. Similar life events and processes have been reported in the literature [37–41] that may serve to “knife off” [22] individuals from their past drug using behaviors to quit drug use or seek substance abuse treatment.

Turning points in drug use and drug use trajectories may also be influenced by recovery capital, a concept used to describe the types and amount of both internal and external resources that can impact (either positively or negatively) one’s capacity to initiate and sustain recovery from substance abuse [42–44]. Recovery capital also includes social capital, economic/financial capital (e.g., income, property), and cultural capital (e.g., values and beliefs that result from membership in a particular cultural group), and human or personal capital (e.g., knowledge, skills, mental health).

While studies have investigated turning points and life events that have contributed to changes in drug use over the long term, research is limited that delves into how contextual factors (e.g., social, environmental, historical), personal characteristics (e.g., age, gender, race/ethnicity), and individual factors (e.g., human agency, recovery capital) might influence turning points.

METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The literature includes various methodological approaches to the study of turning points. Qualitative methods, such as the life history narrative approach, have typically been employed to investigate self-perceived turning points [23, 22, 35, 45–49]. In this approach, the individual’s own words, and the meanings and significance of the events as well as the complicated process of change over time can be captured. For example, with regard to drug use research, in an exploratory qualitative study involving interviews with 18 ex-heroin users, Bammer and Weeks [50] concluded that for many of them, multiple factors were involved in stopping dependent heroin use and that the process is complex. Kearney and O’Sullivan [51] used a grounded theory approach in reviewing 14 qualitative studies of change in unhealthy behaviors, including substance abuse. They concluded that the turning point that prompted behavior change was not the specific life event, but the self-appraisal process that followed. Through the use of qualitative methods, the intricate patterns, sequencing of events and interconnectedness of different life trajectories embedded in social and historical contexts can be unpacked and explored [22]. While a growing knowledge base exists, the samples are typically modest and the work largely exploratory. We have limited knowledge of the mechanisms and processes that underlie turning points in drug use, which would be useful in developing intervention or other strategies to help facilitate positive turning points and to maintain downward trends in drug use.

In addition to qualitative methods, advanced statistical methods involving examination of repeated measures associated with changes in developmental trajectories over time have been used to examine drug use trajectories within which turning points are embedded. With the advent of recent advances in statistical analysis methods applied to longitudinal data (e.g., growth mixture modeling), researchers have been able to discern distinct long-term developmental patterns of substance use [40, 52–61]. For example, Hser et al. [56] identified the trajectories of three distinct user groups among a sample of 471 male heroin users that the researchers had followed over 33 years. The “stable high-level users” maintained a consistently high level of heroin use over 16 years since initiation; the “late decelerated users” showed a high level of use for about 10 years after initiation, after which time more became nonusers; and the “early quitters” decreased use within 3 years of initial use and stopped using within the subsequent 7 years. Ellickson et al. [54] found four developmental trajectory groups of marijuana users studied from adolescence to young adulthood (age 23). The “early high users” had a relatively high level of use at age 13, then decreased their use until about age 18, after which they maintained a relatively moderate level of use; “stable light users” at age 13 had a relatively low level of use and maintained this level throughout the study period; “steady increasers” had no use at age 13 and increased their use in a somewhat linear fashion throughout the study (age 23); “occasional light users” showed no use at age 13 and comparatively lower levels of use at all other time points. However, although research on drug use trajectories over the life course is increasing, it is still unclear what influences these pathways, and more importantly, the turning points that bring about enduring changes in substance use. To the authors’ knowledge, the turning points associated with particular drug use trajectories have not been explored.

Rutter [19] cautions that an investigation of turning points “requires careful attention to measurement issues, the examination of systematic intra-individual change over time, and the testing of hypothesis-driven connections between such intra-individual change and the occurrence of some intra- or extra-organismic experience that has selectively impinged on the individual and which might have brought about the change” (pp. 621–622). Abbott [16] explains that “a true turning point, as distinguished from a mere random episode, has the further character that the trajectories it separates either differ in direction (slope, transition probabilities, regression character) or in nature (one is ‘trajectory-like,’ the other is random)” (p. 94). However, quantitative methods may not fully capture the underlying mechanisms and processes influencing turning points. At present, use of such methods is not able to explain what marked the turning point, which may be different for individuals even with similar trajectories.

Another option that integrates qualitative and quantitative methods is to prospectively, concurrently, and repeatedly collect and analyze both quantitative and qualitative data to examine turning points and related factors as well as the underlying processes over the long-term among cohorts of drug users. Statistical analyses conducted to identify drug use and related trajectories (e.g., crime, mental health) could alert researchers as to when turning points occur over the life course. Complementary qualitative data could shed light on the underlying mechanisms and processes associated with the turning points. However, integrating qualitative and quantitative approaches, and data, would most likely be extremely resource and time intensive.

Several additional methodological issues related to empirically investigating turning points in many studies have been raised because of the subjective and retrospective process involved in identifying them [31]. Whether a critical life event is perceived as a turning point at one point in time may differ at another point in time, for example, several decades later. “What makes a turning point a turning point rather than a minor ripple is the passage of sufficient time ‘on a new course’ such that it becomes clear that the direction has indeed been changed” [16] (p. 89). However, the particular life event is not as consequential -- because individuals respond to the same event in different ways -- but understanding the mechanisms and processes that underlie the turning point is, and may be crucial to developing effective prevention strategies and interventions at critical junctures over the life span.

As investigation of turning points in life course drug use trajectories appears to still be in the exploratory stage, more comprehensive methods are needed in collecting and analyzing data on the wide range and complexity of turning point experiences. This understanding can help in guiding the development of theory and a set of hypotheses that can be tested using statistical methods.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR DRUG USE RESEARCH ON TURNING POINTS

Research on drug use trajectories from a developmental life course perspective is currently limited and studies on turning points in drug use pathways, specifically, are scarcer. We know that individuals are able to identify and describe events and experiences that represent turning points in their drug use. These turning points are not temporary fluctuations in behavior, but are long-lasting. However, turning points vary depending on the person and the context; the same event can trigger a change in one person’s drug use but not another’s. As indicated earlier, the concept of turning points is intuitive, but has been difficult to operationalize; yet the concept is useful as a marker for long-term behavioral changes. The literature suggests that substance abuse researchers must not only identify possible turning point events and experiences, but more importantly, the developmental processes and underlying mechanisms involved in shaping the redirection [2, 16, 19, 22, 37, 60, 62] in drug use trajectories. Rutter [19] argues that “turning points are not things in themselves, but they are an extraordinary useful pointer to the operation of important developmental mechanisms…” (p. 622). Similarly, Pinder [49] states, “The interesting question is not simply identifying the important turning points in a person’s life, but exploring and identifying what it is that constitutes the turn” (p. 213).

Conceptual Framework

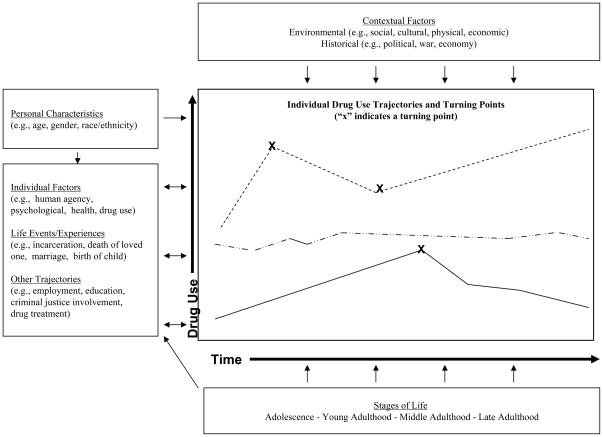

Based on the brief literature review of turning points using a life course perspective, we propose a conceptual framework, illustrated in Fig. (1), to guide future drug use research on turning points. The figure includes key domains and concepts for exploring drug use trajectories and turning points. The framework (1) situates individual drug use trajectories within the context of the larger environment and historical times, (2) takes into consideration that personal characteristics (e.g., age, gender) may influence individual factors (e.g., psychological, health), life events/experiences (e.g., incarceration, birth of a child), and drug use and other trajectories (e.g., criminal justice involvement, employment), and (3) depicts that individual factors, life events and other trajectories may shape and, in turn, be shaped by and interconnected with individual drug use trajectories and turning points in those trajectories. The diverse trajectories illustrated in the center of the figure highlight the heterogeneity and dynamic nature of drug use trajectories and turning points as key events/experiences embedded in these long-term pathways across developmental stages of life (e.g., adolescence, young adulthood, late adulthood). For example, whereas drug use persists over the lifespan for some, for others it may decelerate gradually or dramatically, and then may cease entirely, or it may exhibit a recurring pattern of repeated acceleration and deceleration with periods of abstinence. For some drug offenders, a certain event or experience (e.g., arrest and potential incarceration) may be a turning point and for others, it may not be so. Understanding why this is so is important. Specifically, there is a need to better understand the underlying factors (indicated by the arrows in regular font), mechanisms and processes involved in turning points.

Figure 1.

Preliminary Guiding Conceptual Framework: Drug Use Trajectories and Turning Points

Methods

Although changes in drug use trajectories and their interplay with pathways in other domains (e.g., health, mental health, criminal justice) can be observed through the application of advanced statistical methods or revealed by asking individuals to subjectively identify turning points in their lives, research is needed to uncover and explore, from the drug abuser point of view as well as using statistical approaches, what contributes to changes to or persistence in drug use behaviors. Qualitative methods in particular, but also qualitative and quantitative methods used in an integrated manner, are needed as research on turning points in drug use trajectories is still at the exploratory stage, and we need to first understand, for example: the factors and processes that influence turning points in drug use; the role that timing, sequence, developmental age, human agency, race/ethnicity, and social capital and structures, and other contextual factors play in redirecting drug use trajectories; and the processes and factors that may be altered, supported or developed to facilitate positive turning points experiences.

SUMMARY

The concept of turning points in the life course as applied in the social sciences and more recently in the area of developmental criminal careers has increased our understanding of events and processes that may trigger a redirection of a life pathway over time (e.g., desistence of criminal activity) and may be similarly valuable when applied to drug use careers (e.g., initiation, acceleration, regular use, cessation, relapse) [2]. The developmental life course perspective alerts investigators to the importance of considering the multifaceted and ever-changing influences that shape interdependent drug use and other trajectories over the life span. Longitudinal research and sophisticated statistical methods developed to analyze such data complements the widely held view of drug addiction as a chronic and relapsing condition that may persist over the adult life span. Turning points in a life course perspective is an important evolving area of investigation in the substance abuse field. The influence of related life course concepts, including timing and sequencing of life events, individual characteristics, human agency, and social and historical context on drug use trajectories and turning points offers a potentially fruitful area of investigation that may increase our understanding of why and how drug users stop using over the long-term. Understanding the factors and processes involved in triggering a drug user’s decision to quit using or seek treatment will help policy makers design programs and researchers and health care professionals to develop and implement more effective intervention strategies.

Learning Objectives.

Become familiar with the literature relevant to turning points from life course and developmental criminology perspectives.

Become familiar with the literature on turning points as it pertains to substance use.

Future Research Questions.

What contextual factors, personal characteristics and individual factors influence turning points in drug use?

What mechanisms and processes underlie turning points in drug use?

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Grant Numbers P30 DA016383 and R03DA025291 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Dr. Hser is also supported by a Senior Scientist Award (K05 DA017648). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health. We thank the Center for Advancing Longitudinal Drug Abuse Research (CALDAR) Executive Committee members for their comments on an early draft of the manuscript.

References

- 1.McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;284:1689–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hser Y, Longshore D, Anglin MD. The life course perspective on drug use. Eval Rev. 2007;31:515–547. doi: 10.1177/0193841X07307316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dennis M, Scott C. Managing addiction as a chronic condition. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2007;4:45–55. doi: 10.1151/ascp074145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hser Y, Anglin MD, Grella C, Longshore D, Prendergast ML. Drug treatment careers: A conceptual framework and existing research findings. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1997;14:543–558. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. [Accessed on September 10, 2008];American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. (4). from Dictionary.com website: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/turningpoint.

- 6.Rönka A, Oravala S, Pulkknen L. Turning points in adults’ lives: The effects of gender and the amount of choice. J Adult Dev. 2003;10:203–215. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wheaton B, Gotlib IH. In: Stress and adversity over the life course. Gotlib IH, Wheaton B, editors. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sampson RJ, Laub JH. A life-course view of the development of crime. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2005;602:12–45. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benson ML. Crime and the life course: An introduction. Los Angeles: Roxbury; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elder GH. Perspectives on the life course. In: Elder GH, editor. Life course dynamics: Trajectories and Transitions, 1968–1980. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 1985. pp. 23–49. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sampson RJ, Laub JH. Socioeconomic achievement in the life course of disadvantaged men: Military service as a turning point, circa 1940–1965. Am Sociol Rev. 1996;61:347–367. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sampson RJ, Laub JH. Crime in the making: Pathways and turning points though life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elder GH, Gimbel C, Ivie R. Turning points in life: the case of military service and war. Mil Psychol. 1991;3:215–231. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laub JH, Nagin DS, Sampson RJ. Trajectories of change in criminal offending: Good marriages and the desistance process. Am Sociol Rev. 1998;63:225–238. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uggen C. Work as a turning point in the life course of criminals: A duration model of age, employment, and recidivism. Am Sociol Rev. 2000;65:529–546. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbott A. On the concept of turning point. Comp Soc Res. 1997;16:85–105. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pickles A, Rutter M. Statistical and conceptual models of ‘turning points’ in developmental processes. In: Magnusson D, Bergman LR, Rudinger G, Torestad B, editors. Problems and methods in longitudinal research: Stability and change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991. pp. 133–65. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denzin NK. Interpretive interactionism. 2. California: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rutter M. Transitions and turning points in developmental psychopathology: As applied to the age span between childhood and mid-adulthood. Int J Behav Dev. 1996;19:603–626. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uggen C, Staff J. Work as a turning point for criminal offenders. Corrections Management Quarterly. 2001;5:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright JP, Cullen FT. Employment, peers, and life-course transitions. Justice Quarterly. 2004;21:183–204. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laub JH, Sampson RJ. Shared beginnings, divergent lives: Delinquent boys to age 70. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whethington E, Cooper H, Holmes CS. In: Stress and adversity over the life course. Gotlib IH, Wheaton B, editors. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 215–231. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moneyham L, Connor A. The road in and out of homelessness: Perceptions of recovering substance abusers. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 1995;6:11–19. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(05)80018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rönka A, Oravala S, Pulkknen L. “I met this wife of mine and things got onto at better track”: Turning points in risk development. J Adolesc. 2002;25:47–63. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elder GH. Time, human agency, and social change: Perspectives on the life course. Soc Psychol. 1994;57:4–15. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thornberry TP, editor. Developmental theories of crime and delinquency. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elder GH. The life course as developmental theory. Child Development. 1998;69:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leonard R, Burns A. Turning points in the lives of midlife and older women: Five-year follow-up. Aust Psychol. 2006;41:28–36. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laub JH, Sampson RJ. Turning points in the life course: Why change matters to the study of crime. Criminology. 1993;31:301–325. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hareven T, Masaoka K. Turning points and transitions: Perceptions of the life course. J Fam Hist. 1988;13:271–289. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Granfield R, Cloud W. Social context and “natural recovery”: The role of social capital in the resolution of drug-associated problems. Subst Use Misuse. 2001;36:1543–1570. doi: 10.1081/ja-100106963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coleman J. Social capital in the creation of human capital. A J S. 1988;94:95–120. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liddle J, Carlson G, McKenna K. Using a matrix in life transition research. Qual Health Res. 2004;14:1396–1417. doi: 10.1177/1049732304268793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenqvist P, Blomqvist J, Koski-Jännes, Öjesjö L, editors. Addiction and life course, NAD Monograph No. 44; Proceedings of the 2002 meeting of the Kettil Bruun Society for Social and Epidemiological Research on Alcohol on “Addiction in the Life Course Perspective”; Helsinki: Nordic Council for alcohol and Drug Research; 2004. Retrieved on January 25, 2010 from http://www.nordisktvalfardscenter.org/?id=91749&cid=91758. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaskutas LA. Pathways to self-help among women of sobriety. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1996;22:259–80. doi: 10.3109/00952999609001658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Curran PJ, Muthen BO, Harford TC. The influence of changes in marital status on developmental trajectories of alcohol use in young adults. J Stud Alcohol. 1998;59:647–658. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blomqvist J. Recovery with and without treatment: A comparison of resolutions of alcohol and drug problems. Addict Res Theory. 2002;10:119–158. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Maturing out of alcohol dependence: The impact of transitional life events. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67:195–203. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karlamangla A, Zhou K, Reuben D, Greendale G, Moore A. Longitudinal trajectories of heavy drinking in adults in the United States of America. Addiction. 2006;101:91–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McIntosh J, McKeganey N. Addicts’ narratives of recovery from drug use: Constructing a non-addict identity. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:1501–1510. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00409-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cloud W, Granfield R. Natural recovery from substance dependency: Lessons for treatment providers. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2001;1:83–104. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cloud W, Granfield R. A life course perspective on exiting addiction: The relevance of recovery capital in treatment. NAD Publication. 2004;44:185–202. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cloud W, Granfield R. Conceptualizing recovery capital: Expansion of a theoretical construct. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43:1971–1986. doi: 10.1080/10826080802289762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banyard VL, Williams LM. Women’s voices on recovery: A multi-method study of the complexity of recovery from child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31:275–290. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Denzin NK. The recovering alcoholic. California: Sage; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 47.King G, Cathers T, Brown E, et al. Turning points and protective processes in the lives of people with chronic disabilities. Qual Health Res. 2003;13:184–206. doi: 10.1177/1049732302239598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Öjesjö L. The recovery from alcohol problems over the life course: The Lundby longitudinal study, Sweden. Alcohol. 2000;22:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(00)00106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pinder R. Turning points and adaptations: One man’s journey into chronic homelessness. Ethos. 1994;22:209–239. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bammer G, Weekes S. Becoming an ex-user: Insights into the process and implications for treatment and policy. Drug Alcohol Rev. 1994;13:285–292. doi: 10.1080/09595239400185381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kearney MH, O’Sullivan J. Identity shifts as turning points in health behavior change. West J Nurs Res. 2003;25:134–152. doi: 10.1177/0193945902250032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chassin L, Pitts SC, Prost J. Binge drinking trajectories from adolescence to emerging adulthood in a high-risk sample: Predictors and substance abuse outcomes. J Consult Clin Psych. 2002;70:67–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clark DB, Jones BL, Wood DS, Cornelius JR. Substance use disorder trajectory classes: Diachronic integration of onset age, severity, and course. Addict Behav. 2006;31:995–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ellickson PL, Martino SC, Collins RL. Marijuana use from adolescence to young adulthood: Multiple developmental trajectories and their associated outcomes. Health Psychol. 2004;23:299–307. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guo J, Chung I-J, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. Developmental relationships between adolescent substance use and risky sexual behavior in young adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31:354–362. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00402-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hser Y, Huang Y, Anglin MD. Trajectories of heroin addiction: Growth mixture modeling results based on a 33-year follow-up study. Eval Rev. 2007;31:548–563. doi: 10.1177/0193841X07307315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Needham BL. Gender differences in trajectories of depressive symptomatology and substance use during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:1166–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prendergast M, Huang D, Hser Y. Patterns of crime and drug use trajectories in relation to treatment initiation and five-year outcomes: An application of growth mixture modeling across three datasets. Eval Rev. 2008;32:59–82. doi: 10.1177/0193841X07308082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, Johnston LD. J Stud Alcohol. 1996;57:289–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tucker JS, Ellickson P, Orlando M, Martino S, Klein D. Substance use trajectories from early adolescence to emerging adulthood: A comparison of smoking, binge drinking, and marijuana use. J Drug Issues. 2005;35:307–332. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xie H, Drake R, McHugo G. Are there distinctive trajectory groups in substance abuse remission over 10 years? An application of the group-based modeling approach. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006;33:423–432. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thurnher M. Turning points and developmental change: Subjective and “objective” assessments. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1983;53:52–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1983.tb03349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]