Abstract

Epidemiological studies have shown a positive correlation between poor lung function and respiratory disorders like asthma and development of adverse cardiovascular events. Increased adenosine (AD) levels are associated with lung inflammation which could lead to altered vascular responses and systemic inflammation. There is relatively little known about the cardiovascular effects of adenosine in a model of allergy. We have shown that A1 adenosine receptors (AR) are involved in altered vascular responses and vascular inflammation in allergic mice. Allergic A1wild type mice showed altered vascular reactivity, increased airway responsiveness and systemic inflammation. Our data suggests that A1 AR is pro-inflammatory systemically in this model of asthma. There are also reports of the A2B receptor having anti-inflammatory effects in vascular stress; however its role in allergy with respect to vascular effects hasn’t been fully explored. In this review, we have focused on the role of adenosine receptors in allergic asthma and the cardiovascular system and its possible mechanism (s) of action.

Keywords: Allergy, asthma, vascular inflammation, vascular reactivity, adenosine receptors, adenosine metabolism, G-protein coupled receptor.

1. Generation of adenosine and its metabolism

Adenosine is a ubiquitous purine nucleoside with multiple physiological effects. It has several regulatory functions including relaxation of the vascular smooth muscle, neuromodulation, regulation of inotropy, chronotropy amongst others [1]. Under normal physiological conditions, adenosine is formed by the intracellular conversion of S-adenosyl-L methionine (SAM) to S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine (SAH), which is then converted to adenosine and homocysteine by SAH-hydrolase [2, 3]. Adenosine can also be produced extra-cellulary through successive dephosphorylation of ATP; ATP is dephosphorylated to ADP and then AMP which is converted to adenosine via ecto-5’-nucleotidases [4, 5]. Adenosine, thus, produced can be further converted to inosine by the enzyme adenosine deaminase (ADA) and finally is broken down to uric acid which is excreted in urine. Adenosine can be phosphorylated to AMP via the enzyme adenosine kinase. Extra-cellular concentrations of adenosine are elevated several fold during periods of increased metabolic demand, injury or stress such as ischemia [6] and inflammation.

2. Adenosine receptors

Adenosine acts on specific cell surface purinergic receptors to induce various physiological effects, and thus far, four subtypes have been identified; namely A1, A2A, A2B and A3. All four adenosine receptors are G-protein coupled and the effects that adenosine produces depends on both the receptor subtype that is activated as well as organ/tissue in which the receptor is present. A1 and A3 receptors are coupled to Gi while the A2A and A2B receptors are coupled to Gs. A1 and A2A have a high affinity for adenosine, while A2B is low affinity and A3 is intermediate [7, 8]. The A1 receptor signals through Gi/Go-proteins and its activation leads to an inhibition of adenylyl cyclase (AC) which causes a lowering of cyclic AMP (cAMP). Signaling through the A1 receptor can also lead to activation of IP3/DAG through the PLCβ-III pathway [9]. The A2A receptor signals through the Gs pathway and its activation leads to stimulation of AC resulting in increased production of cAMP. The A2A receptor is mainly anti-inflammatory and is involved in coronary vasodilation as well as vascular smooth muscle relaxation to various degrees depending on the species [10-12]. The A2B receptor signals through Gs/q and its activation can either result in increased cAMP, IP3/DAG and Ca2+ levels. Lastly, the A3 receptor signals through Gi and is negatively coupled to AC [13].

3. Asthma

Asthma is a chronic lung disease characterized by inflammation and airway hyper-reactivity. There are over 20 million people diagnosed with asthma, with 9 million under the age of 18 years. Allergic asthma accounts for about half of these numbers. The disease consists of episodic events which manifest as hyper-responsiveness of the airways to common triggers like dust, pollen, cold air, exercise, cigarette smoke and other pollutants, resulting in bronchospasm and difficulty in breathing. Airway obstruction occurs due to inflammation, excessive mucus production, and overactive bronchial smooth muscle. Initially, the inflammation is acute in nature but eventually becomes chronic with the progression of the disease, and long term effects of asthma are linked to the inflammatory component of the disease. Disease management consists of anti-inflammatory drugs, leukotriene modifiers and bronchodilators.

4. Adenosine and asthma

Adenosine has long been implicated in the pathogenesis of asthma [14]. Inhalation of adenosine was shown to be a potent bronchoprovocant in asthmatic patients [15]. Inosine, the deaminated metabolite of adenosine does not produce bronchoconstriction [16] suggesting that the effect on bronchial smooth muscle is specific to adenosine and possibly involves adenosine receptors. Increases in adenosine levels correspond to increased airway inflammation and tissue damage, and asthmatic patients also have significantly higher levels of adenosine in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) and exhaled breath condensate than normal healthy subjects [17, 18]. Adenosine causes degranulation of mast cells which leads to the release of histamine and subsequent cascade of events including H1 receptor mediated bronchoconstriction and inflammatory response [19, 20]. This mast-cell mediated response is believed to occur through the A2B receptor although this has not been conclusively proven as yet [21].

Mice that lack the adenosine deaminase (ADA) enzyme have large amounts of adenosine in their lungs and severe lung inflammation [22]. In fact, these mice were unable to survive beyond three weeks due to respiratory distress ADA deficient mice demonstrated the presence of eosinophilia in the lungs extensive mast cell degranulation and increased levels of serum IgE [23], indicating a strong correlation between chronic elevation of adenosine levels and increased lung inflammation. There is evidence that adenosine causes recruitment of inflammatory cells to the lung [24] and amplification of the inflammatory response [25].

In allergic mice, adenosine among other inflammatory mediators from allergic lung and activated leukocytes are released [16, 26]. This adenosine may be involved in further release of chemotactic and inflammatory mediators in the lung and systemic circulation by acting on its receptors present on different cells including mast cells, eosinophils, neutrophils and other inflammatory cells [25, 27-29]. Experimentally induced temporary elevations in lung adenosine levels through the inhalation of adenosine (resulting from breakdown of adenosine 5'-monophosphate) have been shown to cause an increase in infiltration of eosinophils in patients with asthma [30].

5. Reactive airway diseases and cardiovascular complications

There is epidemiological evidence indicating that people suffering from asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and reactive airway diseases are at an increased risk for developing cardiovascular disease (CVD) [31-33]. There is an association between atherosclerosis and stroke with reactive airway diseases. One study found that adult-onset asthma was associated with increased carotid atherosclerosis in women [34]. Impaired lung function has been found to be a risk factor for CVD [35]. Bronchial hyper-responsiveness to methacholine is associated with increased carotid intima-media thickness [36]. One of the leading causes for hospitalizations and deaths occurring in COPD patients is cardiovascular events [37].

Recent evidence in animal models indicates that CV complications associated with asthma are independent of asthma therapy and could be a result of asthma itself. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury was enhanced in a rabbit model of systemic allergy and asthma [38] and allergic inflammation in the airways enhanced neutrophil recruitment to the myocardium and severity of ischemia-reperfusion in a murine model [39]. Allergic mice have poor vascular responses and systemic inflammation, with adenosine aerosol exacerbating these effects [40]; Table 1). In our study, we found that use of an A1 AR antagonist ameliorated some of these effects that lead to the hypothesis that A1 AR receptor is involved in proinflammatory effects systemically in a mouse model of allergic asthma.

Table 1.

Vascular responses to adenosine in Balb-C mice aorta [40]

| Group | Response to 10-4 M adenosine (%) |

|---|---|

| Control | 21.44±3.94 |

| Allergic | 7.02±2.94* |

| Allergic + adenosine | -4.45±3.8 (contraction)*# |

P<0.05 compared to control

P<0.05 compared to allergic tissues.

+ Relaxation; - contraction

6. Adenosine receptors in asthma and vasculature

Adenosine has a well established role in the control of vascular tone, and its effects are exerted through the activation of four ARs [41]. A1 and A3 ARs have been shown to be involved in vasoconstriction [9, 42-44] whereas A2A and A2B ARs cause vasorelaxation [45-47]. Adenosine and other inflammatory mediators are released from allergic lung and activated leukocytes [16, 26]. Adenosine that is generated in allergic lungs may be involved in the release of further chemotactic and inflammatory mediators in the lung and systemic circulation by acting on its receptors present on different cells including mast cells, eosinophils, neutrophils and other inflammatory cells [25, 27-29]. This has been confirmed by recent observations where experimentally induced temporary elevations in lung adenosine levels through the inhalation of adenosine (resulting from breakdown of adenosine 5'-monophosphate) have been shown to cause an increase in infiltration of eosinophils in patients with asthma [30].

The four ARs have different modulatory roles in asthma, and the cardiovascular system [48-50]. Many reports suggest that the A1 AR is involved in direct bronchoconstrictor effects of adenosine. The expression of A1 AR was found to be elevated in a rabbit model of asthma and the use of an A1 antisense nucleotide to inhibit this upregulation resulted in blunted bronchoconstriction to adenosine [51, 52]. Use of a selective A1 antagonist (L-97) produced significant reduction of airway hyper-responsiveness in allergic rabbits by blocking these receptors [53]. A recent study reported that the expression of A1 AR is significantly elevated in airway smooth muscle in asthmatic patients [54]. Other than the effects on airway smooth muscle, the A1 AR has been implicated in increased mucin production in human tracheal cells [55] and in mediating monocyte phagocytosis [56]. All these studies suggest a strong role for the A1 AR in asthma, both in airway obstruction and inflammation.

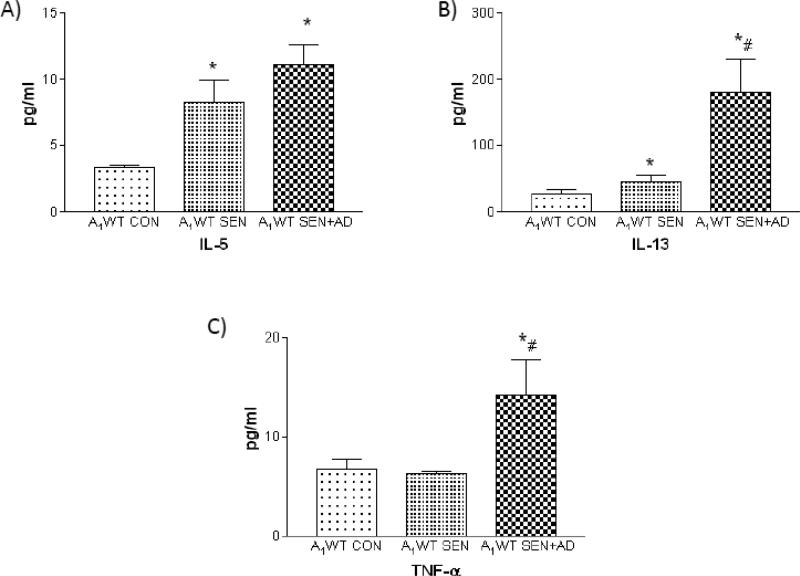

A1 ARs also have systemic effects and are involved in blood pressure regulation [57] and vasoconstriction [9, 42-44]. Recent studies suggest a role for A1 AR in altered peripheral vascular reactivity and increased systemic inflammation [40]; Table 1 and Figs. 1-2). In this study, Balb/C (A1 wild-type: A1WT) mice were divided into 3 groups: control or non allergic (A1WT CON), ragweed sensitized mice (A1WT SEN) and ragweed sensitized mice further challenged with a single aerosol of adenosine (A1WT SEN+AD) were studied.

Figure 1.

Systemic inflammatory markers in plasma A) IL-5 B) IL-13 C) TNF-α in A1WT non-allergic control (A1WT CON), A1WT allergic (A1WT SEN), A1WT allergic further challenged with adenosine (A1WT SEN+AD) mice [40] *P<0.05 compared to WT CON; #P<0.05 compared to WT SEN

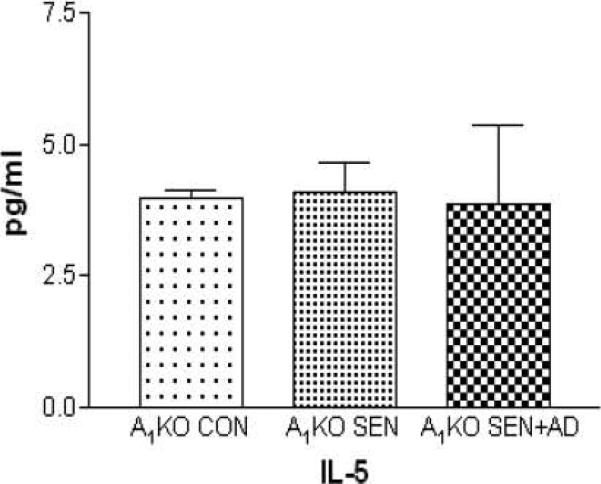

Figure 2.

Plasma levels of IL-5 in A1KO non-allergic control (A1KO CON), A1KO allergic (A1KO SEN), A1KO allergic further challenged with adenosine (A1KO SEN+AD) mice (unpublished observation; IL-13 and TNF-α were not detected in A1KO plasma)

The A2B AR has been found to play a protective role in vasculature against arterial injury (vascular stress) and is involved in the regulation of TNF-alpha, which contributes to the anti-inflammatory actions of adenosine[58]. In A2B receptor–null mice, the expression of vascular adhesion molecules was increased, as also the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines [59, 60]. A2B antagonism also produced further impairment of adenosine mediated aortic vasorelaxation in allergic mice [40].

Despite these data, there is little information specifically regarding the role of lung inflammation (as seen in asthma) in the development of cardiovascular disease, in relation to the vascular and systemic effects of adenosine. Systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction and altered vascular reactivity appear to be associated with asthma. Adenosine plays an important role in these effects and exogenously administered adenosine to increase the lung levels experimentally beyond the allergen exposure exacerbates observed outcomes.

Recent work from our lab [61] using A1 AR knock-out (A1AR KO) mice has shown the involvement of A1 ARs in systemic and vascular inflammation. Data showed that the allergic A1WT mice (A1WT SEN and A1WT SEN+AD groups) had lower adenosine-mediated aortic relaxation to 5’-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA; non-selective adenosine analog) (Table 2) and higher contraction to 2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CCPA; selective A1 AR agonist), with increased protein expression of A1 AR in the aorta. There were also significantly higher levels of inflammatory markers in the plasma, and in aortic tissue. In contrast, no impairment in adenosine-mediated vascular responses was observed in A1 AR KO (Table 2; allergic and non-allergic controls: control or non allergic A1KO CON, ragweed sensitized A1KO SEN and ragweed sensitized further challenged with a single aerosol of adenosine A1KO SEN+AD) aortic tissues. There were also significantly lower (or undetectable) levels of inflammatory markers in aortic tissue in allergic KO mice. These data implicate the involvement of A1 AR in the deleterious systemic effects in allergic mice that may occur as a result of inflammation. The exact signaling mechanism(s) of the A1 AR remains to be elucidated.

Table 2.

Vascular responses to 5’-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA; non-selective AR agonist) in A1 wild-type and knockout Balb/C mice aorta [61]

| Group | Response to 10-5 M NECA (% relaxation) |

|---|---|

| A1WT Control | 48.64±2.98 |

| A1WT Allergic | 28.08±5.06* |

| A1WT Allergic + adenosine | 17.4±5.53* |

| A1KO Control | 43.0±2.45 |

| A1KO Allergic | 48.48±1.93 |

| A1KO Allergic + adenosine | 48.2±1.47 |

P<0.05 compared to WT control

The A2A receptor has been reported to have anti-inflammatory and protective role in the lung, especially lung injury A2A KO mice were shown to have higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and extensive tissue damage when subjected to an inflammatory insult that were less in the corresponding A2A WT mice [62].

Our lab has reported that A2A KO mice have higher oxidative stress that leads to impaired tracheal relaxation [63]. There have also been reports that the A2A AR protects against myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury [64]. In some preliminary data from our lab (unpublished), we have also observed that allergic A2A KO mice have poor aortic relaxation and increased airway response (whole body plethysmography) compared to WT. All these findings lead us to speculate that the A2A AR may protect against vascular inflammation.

Reports have suggested that activation of A3 receptor by inosine [65] as well as adenosine [66] leads to mast-cell induced increase in vascular permeability and extravasation. A3 receptors can also have anti-inflammatory effects [67]. The A3 AR also increases mucin production in asthma [68] and has been shown to be involved in bronchoconstriction and eosinophilia [69, 70]. Other reports suggest an anti-inflammatory role for A3 receptors in diseases like rheumatoid arthritis [71]. The role of the A3 receptor thus could possibly be both pro- and ant-inflammatory. How this receptor behaves in the vasculature in allergic mice remains to be seen.

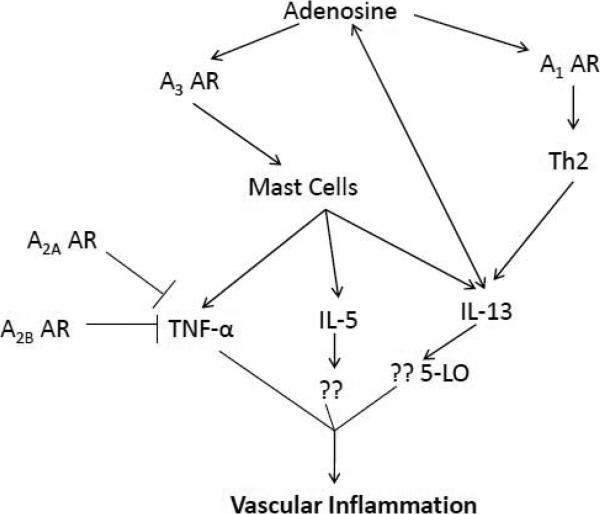

7. Possible pathway for adenosine-induced vascular changes in asthma

Based on the literature and some of our data we hypothesize a speculative pathway for lung inflammation leading to systemic effects (Fig 3). We found that IL-13 levels were highest in allergic mice [40]. A review of the literature shows a close relationship between IL-13 and adenosine in lung inflammation [72]. IL-13 is an important mediator in asthma and has been implicated in lung inflammation and airway remodeling. It is a product of mast cell degranulation and is also released from T-helper 2 (Th2) cells. Adenosine and IL-13 interact with each other positively as shown in studies done with asthmatic mice [72].These authors found that IL-13 caused a progressive increase in adenosine accumulation, inhibited the activity of adenosine deaminase, and augmented the expression of the A1, A2B, and A3 ARs. Their findings suggest that adenosine signaling contributes to and influences the severity of IL-13 and Th2 -mediated disorders such as asthma.

Figure 3.

Possible pathway for adenosine receptors as both pro- and anti-inflammatory effectors in vascular inflammation in asthma. “??” indicates unknown or possible mediators.

IL-13 signaling occurs through the Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway. This cytokine acts on its receptor (via JAK-1) and leads to phosphorylation of STAT6, which induces the transcription of several genes including 5-lipoxygenase (LO). 5-LO, via the arachidonic acid pathway, produces inflammatory leukotrienes (LTs) which are very important mediators of IL-13 induced lung injury [73]. Recent studies have also suggested a proatherosclerotic role for LTs with LTB4 acting as a potent leukocyte chemoattractant that amplifies inflammation in atherosclerosis [74].

IL-13 and IL-4 act synergistically with TNF-α to increase eotaxin levels in the lungs. Eotaxin increases lung eosinophilia in asthma and is very important in amplification of eosinophilic inflammation. Though eosinophilia is considered to be a characteristic hallmark of asthmatic inflammation, eosinophils are not found in any significant amounts in atherosclerotic lesions. Eotaxin may have a novel role in atherosclerosis independent of eosinophils. Haley et al. have reported that eotaxin and its receptor, CCR3, were overexpressed in the inflammatory infiltrate of human atheroma [75]. CCR3 was predominantly expressed on macrophages and they suggest eotaxin may participate in mast cell activation or recruitment. In addition to this, in our most recent study [61] we have found significantly higher levels of IL-5 in aortic tissue of allergic A1WT mice. This may further support a role for IL-5 induced eotaxin effects in vasculature.

In conclusion, adenosine mediated effects in asthma may extend beyond the lung and have consequences both systemically and in the vasculature. It is possible that inflammation underlies these additional effects and there is evidence so far for the A1 AR having a pro-inflammatory role. There remains much to be learnt in this field, with each adenosine receptor's role not yet delineated. Such studies would help to further the potential of adenosine agonists and antagonists as therapeutic agents for systemic and vascular inflammation from a number of disorders including hypertension, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and many other complications.

Acknowledgments

Supported by: NIH grants HL 027339 and HL04447

ABBREVIATIONS

- AC

Adenylyl cyclase

- ACh

Acetylcholine

- ADA

Adenosine deaminase

- AD

Adenosine

- ADP

Adenosine diphosphate

- AR

Adenosine receptor

- AK

Adenosine kinase

- AMP

Adenosine monophosphate

- BAL

Bronchoalveolar lavage

- cAMP

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CCPA

2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine

- CGS

21860 2-p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenethylamino-5' N- ethylcarboxy amidoadenosine hydrochloride

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CV

Cardiovascular

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DAG

Diacylglycerol

- DPCPX

1,3-Dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine

- IP3

Inositol triphosphate

- LO

Lipoxygenase

- LT

Leukotriene

- KO

Knockout

- NECA

N-ethylcarboxamide-adenosine

- SAH

S-Adenosyl-L-homocysteine

- SAH-hydrolase

S-Adenosyl-L-homocysteine-hydrolase

- SAM

S-Adenosyl-L methionine

- WT

Wild type

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fredholm BB. Adenosine, an endogenous distress signal, modulates tissue damage and repair. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1315–1323. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pelleg A, Porter RS. The pharmacology of adenosine. Pharmacotherapy. 1990;10:157–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deussen A, Lloyd HG, Schrader J. Contribution of S-adenosylhomocysteine to cardiac adenosine formation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1989;21:773–782. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(89)90716-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forsythe P, Ennis M. Adenosine, mast cells and asthma. Inflamm Res. 1999;48:301–307. doi: 10.1007/s000110050464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bardenheuer H, Schrader J. Supply-to-demand ratio for oxygen determines formation of adenosine by the heart. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:H173–180. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.250.2.H173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sparks HV, Jr., Bardenheuer H. Regulation of adenosine formation by the heart. Circ Res. 1986;58:193–201. doi: 10.1161/01.res.58.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryzhov S, Goldstein AE, Biaggioni I, Feoktistov I. Cross-talk between G(s)- and G(q)-coupled pathways in regulation of interleukin-4 by A(2B) adenosine receptors in human mast cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:727–735. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.022780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobson KA. A3 adenosine receptors: design of slective ligands and therapeutic prospects. 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Tawfik HE, Schnermann J, Oldenburg PJ, Mustafa SJ. Role of A1 adenosine receptors in regulation of vascular tone. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1411–1416. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00684.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nayeem MA, Poloyac SM, Falck JR, Zeldin DC, Ledent C, Ponnoth DS, Ansari HR, Mustafa SJ. Role of CYP epoxygenases in A2A AR-mediated relaxation using A2A AR-null and wild-type mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H2068–2078. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01333.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ponnoth DS, Sanjani MS, Ledent C, Roush K, Krahn T, Mustafa SJ. Absence of adenosine-mediated aortic relaxation in A(2A) adenosine receptor knockout mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1655–1660. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00192.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mustafa SJ, Morrison RR, Teng B, Pelleg A. Adenosine receptors and the heart: role in regulation of coronary blood flow and cardiac electrophysiology. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009:161–188. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-89615-9_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ansari HR, Nadeem A, Tilley SL, Mustafa SJ. Involvement of COX-1 in A3 adenosine receptor-mediated contraction through endothelium in mice aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H3448–3455. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00764.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson CN, Nadeem A, Spina D, Brown R, Page CP, Mustafa SJ. Adenosine receptors and asthma. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009:329–362. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-89615-9_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cushley MJ, Tattersfield AE, Holgate ST. Inhaled adenosine and guanosine on airway resistance in normal and asthmatic subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;15:161–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1983.tb01481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mann JS, Holgate ST, Renwick AG, Cushley MJ. Airway effects of purine nucleosides and nucleotides and release with bronchial provocation in asthma. J Appl Physiol. 1986;61:1667–1676. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.61.5.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Driver AG, Kukoly CA, Ali S, Mustafa SJ. Adenosine in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:91–97. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huszar E, Vass G, Vizi E, Csoma Z, Barat E, Molnar Vilagos G, Herjavecz I, Horvath I. Adenosine in exhaled breath condensate in healthy volunteers and in patients with asthma. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:1393–1398. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00005002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fozard JR, Hannon JP. Species differences in adenosine receptor-mediated bronchoconstrictor responses. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:1213–1220. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oldenburg PJ, Mustafa SJ. Involvement of mast cells in adenosine-mediated bronchoconstriction and inflammation in an allergic mouse model. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:319–324. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.071720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhong H, Shlykov SG, Molina JG, Sanborn BM, Jacobson MA, Tilley SL, Blackburn MR. Activation of murine lung mast cells by the adenosine A3 receptor. J Immunol. 2003;171:338–345. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blackburn MR, Volmer JB, Thrasher JL, Zhong H, Crosby JR, Lee JJ, Kellems RE. Metabolic consequences of adenosine deaminase deficiency in mice are associated with defects in alveogenesis, pulmonary inflammation, and airway obstruction. J Exp Med. 2000;192:159–170. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhong H, Chunn JL, Volmer JB, Fozard JR, Blackburn MR. Adenosine-mediated mast cell degranulation in adenosine deaminase-deficient mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:433–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan M, Mustafa SJ. Adenosine-mediated bronchoconstriction and lung inflammation in an allergic mouse model. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2002;15:147–155. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2001.0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spicuzza L, Di Maria G, Polosa R. Adenosine in the airways: implications and applications. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;533:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mann JS, Renwick AG, Holgate ST. Release of adenosine and its metabolites from activated human leucocytes. Clin Sci (Lond) 1986;70:461–468. doi: 10.1042/cs0700461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Driver AG, Kukoly CA, Metzger WJ, Mustafa SJ. Bronchial challenge with adenosine causes the release of serum neutrophil chemotactic factor in asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143:1002–1007. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.5_Pt_1.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan M, Jamal Mustafa S. Role of adenosine in airway inflammation in an allergic mouse model of asthma. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nadeem A, Mustafa SJ. Adenosine receptor antagonists and asthma. Drug Disc Today: Therapeutic Strategies. 2006;3:269–275. [Google Scholar]

- 30.van den Berge M, Kerstjens HA, de Reus DM, Koeter GH, Kauffman HF, Postma DS. Provocation with adenosine 5'-monophosphate, but not methacholine, induces sputum eosinophilia. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:71–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sin DD, Man SF. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:8–11. doi: 10.1513/pats.200404-032MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gan WQ, Man SF, Senthilselvan A, Sin DD. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Thorax. 2004;59:574–580. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.019588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schanen JG, Iribarren C, Shahar E, Punjabi NM, Rich SS, Sorlie PD, Folsom AR. Asthma and incident cardiovascular disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Thorax. 2005;60:633–638. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.026484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onufrak S, Abramson J, Vaccarino V. Adult-onset asthma is associated with increased carotid atherosclerosis among women in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195:129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tockman MS, Pearson JD, Fleg JL, Metter EJ, Kao SY, Rampal KG, Cruise LJ, Fozard JL. Rapid decline in FEV1. A new risk factor for coronary heart disease mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:390–398. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.2.7842197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zureik M, Kony S, Neukirch C, Courbon D, Leynaert B, Vervloet D, Ducimetiere P, Neukirch F. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness to methacholine is associated with increased common carotid intima-media thickness in men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1098–1103. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000128128.65312.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sidney S, Sorel M, Quesenberry CP, Jr., DeLuise C, Lanes S, Eisner MD. COPD and incident cardiovascular disease hospitalizations and mortality: Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program. Chest. 2005;128:2068–2075. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hazarika S, Van Scott MR, Lust RM. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury is enhanced in a model of systemic allergy and asthma. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H1720–1725. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01064.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hazarika S. Allergic inflammation in the airways enhances neutrophil recruitment to the myocardium and severity of ischemia-reperfusion. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ponnoth DS, Nadeem A, Mustafa SJ. Adenosine-mediated alteration of vascular reactivity and inflammation in a murine model of asthma. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H2158–2165. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01224.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tabrizchi R, Bedi S. Pharmacology of adenosine receptors in the vasculature. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;91:133–147. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00152-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Talukder MA, Morrison RR, Jacobson MA, Jacobson KA, Ledent C, Mustafa SJ. Targeted deletion of adenosine A(3) receptors augments adenosine-induced coronary flow in isolated mouse heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H2183–2189. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00964.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hansen PB, Castrop H, Briggs J, Schnermann J. Adenosine induces vasoconstriction through Gi-dependent activation of phospholipase C in isolated perfused afferent arterioles of mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2457–2465. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000086474.80845.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shepherd RK, Linden J, Duling BR. Adenosine-induced vasoconstriction in vivo. Role of the mast cell and A3 adenosine receptor. Circ Res. 1996;78:627–634. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ansari HR, Nadeem A, Talukder MA, Sakhalkar S, Mustafa SJ. Evidence for the involvement of nitric oxide in A2B receptor-mediated vasorelaxation of mouse aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H719–725. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00593.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grbovic L, Radenkovic M. Analysis of adenosine vascular effect in isolated rat aorta: possible role of Na+/K+-ATPase. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;92:265–271. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2003.920603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lewis CD, Hourani SM, Long CJ, Collis MG. Characterization of adenosine receptors in the rat isolated aorta. Gen Pharmacol. 1994;25:1381–1387. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(94)90162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Belardinelli L, Linden J, Berne RM. The cardiac effects of adenosine. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1989;32:73–97. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(89)90015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shryock JC, Belardinelli L. Adenosine and adenosine receptors in the cardiovascular system: biochemistry, physiology, and pharmacology. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:2–10. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mubagwa K, Mullane K, Flameng W. Role of adenosine in the heart and circulation. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;32:797–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nyce JW, Metzger WJ. DNA antisense therapy for asthma in an animal model. Nature. 1997;385:721–725. doi: 10.1038/385721a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abebe W, Mustafa SJ. A1 adenosine receptor-mediated Ins(1,4,5)P3 generation in allergic rabbit airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L990–997. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.5.L990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Obiefuna PC, Batra VK, Nadeem A, Borron P, Wilson CN, Mustafa SJ. A novel A1 adenosine receptor antagonist, L-97-1 [3-[2-(4-aminophenyl)-ethyl]-8-benzyl-7-{2-ethyl-(2-hydroxy-ethyl)-amino]- ethyl}-1-propyl-3,7-dihydro-purine-2,6-dione], reduces allergic responses to house dust mite in an allergic rabbit model of asthma. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:329–336. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.088179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brown RA, Clarke GW, Ledbetter CL, Hurle MJ, Denyer JC, Simcock DE, Coote JE, Savage TJ, Murdoch RD, Page CP, Spina D, O'Connor BJ. Elevated expression of adenosine A1 receptor in bronchial biopsy specimens from asthmatic subjects. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:311–319. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00003707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McNamara N, Gallup M, Khong A, Sucher A, Maltseva I, Fahy J, Basbaum C. Adenosine up-regulation of the mucin gene, MUC2, in asthma. Faseb J. 2004;18:1770–1772. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1964fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salmon JE, Brogle N, Brownlie C, Edberg JC, Kimberly RP, Chen BX, Erlanger BF. Human mononuclear phagocytes express adenosine A1 receptors. A novel mechanism for differential regulation of Fc gamma receptor function. J Immunol. 1993;151:2775–2785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brown RD, Thoren P, Steege A, Mrowka R, Sallstrom J, Skott O, Fredholm BB, Persson AE. Influence of the adenosine A1 receptor on blood pressure regulation and renin release. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1324–1329. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00313.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen H, Yang D, Carroll SH, Eltzschig HK, Ravid K. Activation of the macrophage A2b adenosine receptor regulates tumor necrosis factor-alpha levels following vascular injury. Exp Hematol. 2009;37:533–538. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang D, Zhang Y, Nguyen HG, Koupenova M, Chauhan AK, Makitalo M, Jones MR, St Hilaire C, Seldin DC, Toselli P, Lamperti E, Schreiber BM, Gavras H, Wagner DD, Ravid K. The A2B adenosine receptor protects against inflammation and excessive vascular adhesion. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1913–1923. doi: 10.1172/JCI27933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang D, Koupenova M, McCrann DJ, Kopeikina KJ, Kagan HM, Schreiber BM, Ravid K. The A2b adenosine receptor protects against vascular injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:792–796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705563105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ponnoth DS, Nadeem A, Tilley S, Mustafa SJ. Involvement of A1 adenosine receptors in altered vascular responses and inflammation in an allergic mouse model of asthma. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 299:H81–87. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01090.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ohta A, Sitkovsky M. Role of G-protein-coupled adenosine receptors in downregulation of inflammation and protection from tissue damage. Nature. 2001;414:916–920. doi: 10.1038/414916a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nadeem A, Ponnoth DS, Ansari HR, Batchelor TP, Dey RD, Ledent C, Mustafa JS. A2A AR deficiency leads to impaired tracheal relaxation via NADPH oxidase pathway in allergic mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009 doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.151613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang Z, Day YJ, Toufektsian MC, Ramos SI, Marshall M, Wang XQ, French BA, Linden J. Infarct-sparing effect of A2A-adenosine receptor activation is due primarily to its action on lymphocytes. Circulation. 2005;111:2190–2197. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000163586.62253.A5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jin X, Shepherd RK, Duling BR, Linden J. Inosine binds to A3 adenosine receptors and stimulates mast cell degranulation. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2849–2857. doi: 10.1172/JCI119833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tilley SL, Wagoner VA, Salvatore CA, Jacobson MA, Koller BH. Adenosine and inosine increase cutaneous vasopermeability by activating A(3) receptors on mast cells. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:361–367. doi: 10.1172/JCI8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Salvatore CA, Tilley SL, Latour AM, Fletcher DS, Koller BH, Jacobson MA. Disruption of the A(3) adenosine receptor gene in mice and its effect on stimulated inflammatory cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4429–4434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Young HW, Sun CX, Evans CM, Dickey BF, Blackburn MR. A3 adenosine receptor signaling contributes to airway mucin secretion after allergen challenge. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:549–558. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0060OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fan M, Qin W, Mustafa SJ. Characterization of adenosine receptor(s) involved in adenosine-induced bronchoconstriction in an allergic mouse model. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L1012–1019. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00353.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tilley SL, Tsai M, Williams CM, Wang ZS, Erikson CJ, Galli SJ, Koller BH. Identification of A3 receptor- and mast cell-dependent and -independent components of adenosine-mediated airway responsiveness in mice. J Immunol. 2003;171:331–337. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ochaion A, Bar-Yehuda S, Cohen S, Amital H, Jacobson KA, Joshi BV, Gao ZG, Barer F, Patoka R, Del Valle L, Perez-Liz G, Fishman P. The A3 adenosine receptor agonist CF502 inhibits the PI3K, PKB/Akt and NF-kappaB signaling pathway in synoviocytes from rheumatoid arthritis patients and in adjuvant-induced arthritis rats. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;76:482–494. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Blackburn MR, Lee CG, Young HW, Zhu Z, Chunn JL, Kang MJ, Banerjee SK, Elias JA. Adenosine mediates IL-13-induced inflammation and remodeling in the lung and interacts in an IL-13-adenosine amplification pathway. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:332–344. doi: 10.1172/JCI16815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shim YM, Zhu Z, Zheng T, Lee CG, Homer RJ, Ma B, Elias JA. Role of 5-lipoxygenase in IL-13-induced pulmonary inflammation and remodeling. J Immunol. 2006;177:1918–1924. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Back M, Bu DX, Branstrom R, Sheikine Y, Yan ZQ, Hansson GK. Leukotriene B4 signaling through NF-kappaB-dependent BLT1 receptors on vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis and intimal hyperplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17501–17506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505845102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haley KJ, Lilly CM, Yang JH, Feng Y, Kennedy SP, Turi TG, Thompson JF, Sukhova GH, Libby P, Lee RT. Overexpression of eotaxin and the CCR3 receptor in human atherosclerosis: using genomic technology to identify a potential novel pathway of vascular inflammation. Circulation. 2000;102:2185–2189. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.18.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]