Abstract

Reactions of nitric oxide with cysteine-ligated iron-sulfur cluster proteins typically result in disassembly of the iron-sulfur core and formation of dinitrosyl iron complexes (DNICs). Here we report the first evidence that DNICs also form in the reaction of NO with Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] clusters. Upon treatment of a Rieske protein, component C of toluene/o-xylene monooxygenase (ToMOC) from Pseudomonas sp. OX1, with a slight excess of NO (g) or NO-generators S-nitroso-N-acetyl-D,L-pencillamine (SNAP) and diethylamine NONOate (DEANO), the absorbance bands of the [2Fe-2S] cluster are epxtinguished and replaced by a new feature that slowly grows in at 367 nm. Analysis of the reaction products by EPR, Mössbauer, and NRVS spectroscopy reveals that the primary product of the reaction is a thiolate-bridged diiron tetranitrosyl species, [Fe2(μ-SCys)2(NO)4] having a Roussin's red ester (RRE) formula, and that mononuclear DNICs account for only a minor fraction of nitrosylated iron. Reduction of this RRE reaction product with sodium dithionite produces the one-electron reduced Roussin's red ester (rRRE) having absorbtions at 640 and 960 nm. These results demonstrate that NO reacts readily with Rieske centers in protein and suggest that dinuclear RRE species, not mononuclear DNICs, may be the primary iron dinitrosyl species responsible for the pathological and physiological effects of nitric oxide in such systems in biology.

Introduction

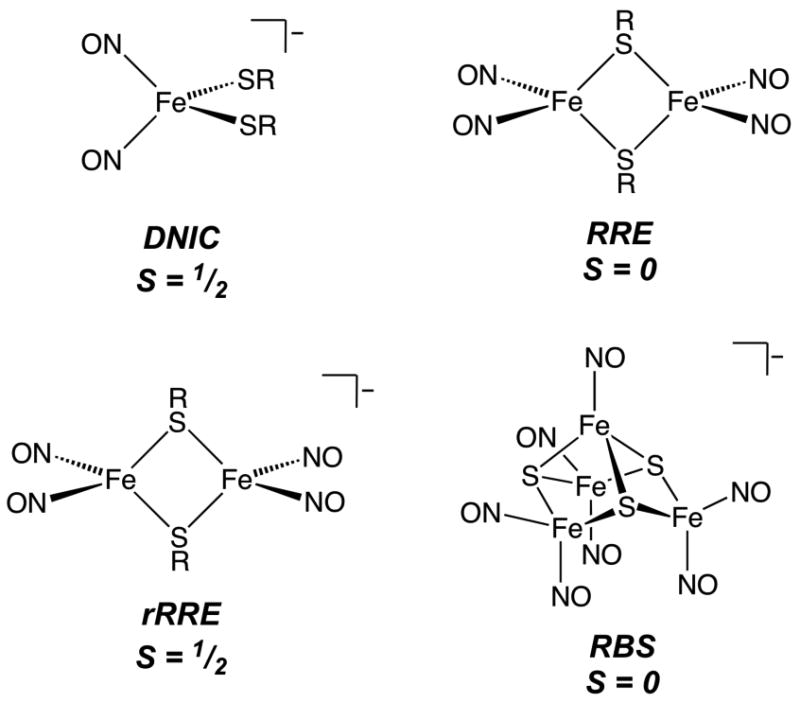

Nitric oxide (NO) drives a variety of biological processes, serving as a neurotransmitter,1 a transcriptional regulator,2-6 a cytotoxic agent,7,8 a signaling molecule in the immune response,9 and the endothelium-derived relaxing factor.10,11 Inside the cell, this small molecule functions primarily by interacting with metal-containing proteins, although its reaction products with O2 (NOx), superoxide (ONOO−), and transition metal ions (NO+) can lead to modification of nucleic acids, amino acid side chains, and small amines and thiols.12-14 Among the metal sites targeted by NO are iron-sulfur cluster proteins.15-17 The chemistry of NO at these sites typically results in disassembly of the iron-sulfur core and formation of dinitrosyl iron complexes (DNICs, Chart 1).18 EPR spectroscopy has long been employed to detect radical species in biological tissue samples19 and has become a standard way of identifying thiolate-ligated DNICs in proteins20 because of their characteristic axial gav = 2.03 signal.21 These species, designated {Fe(NO)2}9 in the Enemark-Feltham notation,22 have the general formula [Fe(NO)2L2]− where L typically represents a sulfur-based ligand such as cysteine.23 DNICs form readily at [2Fe-2S] and [4Fe-4S] clusters in various proteins2,5,18,24-27 and have been proposed to elicit a variety of physiological functions including vasodilation,28-30 regulation of enzymatic activity,24,25 transcription,2,5 DNA repair,31,32 and initiation of heat-shock protein synthesis.33 Treatment of tumor cells that do not generate NO with NO-producing murine macrophages led to EPR-detectable DNICs, suggesting a role for these centers in the immune response.7

Chart 1.

Iron dinitrosyl species observed in biological and biomimetic synthetic systems.

Although mononuclear DNICs are generally deemed to be the important species in biological systems, {Fe(NO)2}9 units can occur as a component of several different structures.34 Included are the dimeric Roussin's red ester (RRE), the reduced Roussin's red ester (rRRE), and an [4Fe-3S] cluster known as Roussin's black salt (RBS) (Chart 1). Like the DNIC, rRRE species can be detected readily by EPR spectroscopy,35,36 and have been generated in several instances upon reduction of NO-treated [4Fe-4S] cluster proteins.18,24 The relevance of iron dinitrosyl species other than the mononuclear DNIC in biological settings is largely unexplored owing to the difficulty of detecting the diamagnetic RRE and RBS species. Using nuclear resonance vibrational spectroscopy (NRVS), we recently showed that Roussin's black salt, rather than a DNIC, is the predominant product formed in the reaction of a D14C mutant [4Fe-4S] ferredoxin from Pyrococcus furious with NO.37 In addition, many of the reported products of iron-sulfur cluster protein reactions with nitric oxide typically display EPR-integrated DNIC signals that account for only a fraction of the total protein iron concentration despite complete cluster degradation.2,5,18,24 Thus, a more definitive spectroscopic method for analyzing the products of NO reactions with iron-sulfur proteins is desired to enhance our understanding of the pathological and physiological properties of nitric oxide.

Despite a sizeable body of literature describing DNIC formation from cysteine-ligated iron-sulfur clusters, there are currently no reports that iron dinitrosyl species are generated at Rieske centers. Rieske proteins, which harbor [2Fe-2S] clusters ligated by two terminal cysteine and two terminal histidine residues, are common to prokaryotes and eukaryotes and play important roles in electron transport, mitochondrial respiration, and photosynthesis.38,39 Because of their similarity to ferredoxins, these proteins are expected to be targeted by NO in vivo. We recently discovered that reaction of NO with a synthetic [2Fe-2S] complex featuring an N2S2 ligand scaffold resulted in formation of both N-bound and S-bound DNICs, suggesting that similar chemistry may occur in Rieske systems.40 To our knowledge, the only report of Rieske protein nitrosylation revealed no evidence for DNIC formation.41 The authors of this study employed purified beef heart ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase (QCR) as a model Rieske system and showed that no S = ½ DNIC species were generated upon reaction with NO gas, although protein activity was reversibly inhibited. The Rieske cluster in QCR is buried within the protein matrix and further shielded from solvent by protein complexation with succinate-ubiquinone reductase, a component used in the assays.41 It is therefore possible that NO could not efficiently access the cluster.

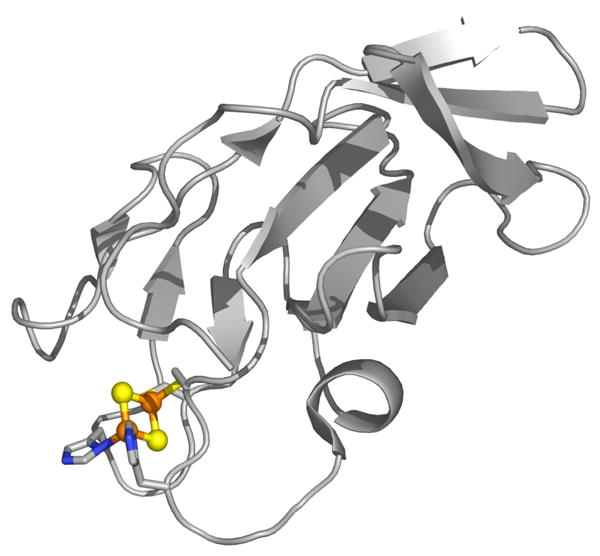

To determine whether DNICs and/or other iron dinitrosyl species can form at biological Rieske centers, in the present study we exposed the Rieske protein, toluene/o-xylene monooxygenase component C (ToMOC) from Pseudomonas sp. OX1, to NO. This 112-residue protein is an ideal system because it harbors a relatively stable [2Fe-2S] Rieske cluster that we anticipate to be largely solvent-exposed based on structural characterization of the closely related toluene 4-monooxygenase component C (T4moC), which shares 57% sequence identity with ToMOC.42 A solution NMR structure determination of T4moC revealed a Rieske cluster coordinated by two histidine and two cysteine ligands on two loop regions extending from the top of a β-sandwich structure. Although one face of the Rieske cluster is shielded by a small β-sheet, the other is largely solvent-exposed (Figure 1). Exogenous NO should be able to reach the [2Fe-2S] center in ToMOC and react to form iron dinitrosyl species in a manner similar to the chemistry observed with 2Fe-2S ferredoxins. Furthermore, Psuedomonas sp. OX1 has the ability to metabolize NO.43 A description of the reactivity of potential target proteins other than those intended for NO metabolism is therefore relevant to the global management of nitric oxide within the organism. Here we demonstrate that iron dinitrosyl species are indeed generated at ToMOC upon exposure to nitric oxide and provide evidence that the major product is not a mononuclear DNIC species but rather the diamagnetic Roussin's red ester (RRE). The implications of these findings with respect to the NO chemistry of other iron sulfur clusters are discussed.

Figure 1.

Solution NMR structure of T4moC, a Rieske protein that shares 57% sequence identity with ToMOC. The [2Fe-2S] center including the coordinating histidine and cysteine ligands are depicted as spheres in ball-and-stick format and are colored by atom type: carbon (gray), nitrogen (blue), sulfur (red), iron (orange). PDB ID code 1SJC.

Materials and Methods

General Considerations

Manipulations requiring anaerobic conditions were conducted in a Vacuum Atmospheres glovebox under an atmosphere of purified N2. Buffer solutions were degassed by sparging with N2 for a minimum of 1 h. ToMOC was expressed in E. coli and purified as described elsewhere.44 Protein obtained by this method generally exhibited an A458/A280 ratio ≥ 0.12. The buffer system employed in all experiments was 25 mM potassium phosphate (KPi), pH 7.0. S-nitroso-N-acetyl-D,L-penicillamine (SNAP) and diethylamine NONOate (DEANO) were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI) and used as received. Nitric oxide (99%) was purchased from AirGas and was purified according to a protocol described previously.45 Briefly, NO was passed through an Ascarite column (NaOH fused on silica gel) and then a 6-ft coil filled with silica gel and cooled to −78 °C with a dry ice/acetone bath. NO gas was stored and transferred under an inert atmosphere using a gas storage bulb. 57Fe metal (95.5%) was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA). All other chemicals were obtained from Aldrich and were used as received. Distilled water was deionized with a Milli-Q filtering system.

Preparation of 57Fe-ToMOC

For incorporation of 57Fe into ToMOC, BL21(DE3) E. coli cells harboring the touC-pET22b(+) plasmid were grown in minimal media consisting of 10 g bactotryptone and 5 g NaCl in 1L ddH2O supplemented with 4 g/L casamino acids, 1 mM thiamine hydrochloride, 4 g/L glucose, 100 mg/mL ampicillin, and 50 μM 57FeCl3. Solutions of 57FeCl3 were prepared by dissolving 57Fe metal in ultrapure concentrated HCl. Cells were grown at 37 °C and were induced at an O.D.600 of 0.7 with 400 μM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Following induction, cells were grown at 37 °C for 3 h, collected by centrifugation, and stored at -80 °C until further use.

ToMOC Reduction

Na2S2O4 was titrated into ToMOCox to determine the number of electrons needed to achieve complete protein reduction. A solution of Na2S2O4 in 25 mM KPi, pH 7.0, was prepared and its concentration was determined by anaerobic titration into K3[Fe(CN)6].46 This solution was then diluted to 937 μM and was anaerobically titrated into 92.6 μM ToMOCox in 5 μL aliquots. Experiments were conducted in a glass tonometer equipped with a titrator and a quartz optical cell. UV-vis spectra were recorded after addition of each aliquot of Na2S2O4.

General Spectroscopic Measurements

EPR samples of ToMOCred were prepared by incubating ToMOCox with 0.5 equiv of Na2S2O4 at room temperature in an anaerobic chamber. Reactions of ToMOCox and ToMOCred with DEANO were carried out by incubating the protein with excess (at least 5 equiv) DEANO for 1 h at room temperature. Mössbauer samples were prepared by incubating 57Fe-enriched ToMOCox with 34 equiv of DEANO for 1 h at room temperature. Zero field 57Fe Mössbauer spectra were recorded at 90 K on an MSI spectrometer (WEB Research Company) with a 57Co source embedded in a Rh matrix. The isomer shift (δ) values are reported with respect to iron foil (α-Fe). Spectra were folded and simulated using the WMOSS software program (WEB Research Company).47 UV-vis spectra were measured on a Cary-50 spectrophotometer at 25 °C in a septum-capped quartz cell. X-Band EPR spectra were recorded at 77 K on a Bruker EMX spectrometer equipped with a quartz finger dewar. Spin quantitations were performed by comparison of the doubly integrated signals to those of a 500 μM CuEDTA solution in KPi or a standard of 250 μM [(Ar-nacnac)Fe(NO)2] (Ar-nacnac = [(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)NC(Me)]2CH) prepared in 2-MeTHF or toluene.

NRVS Measurements

Samples of 1.56 mM 57Fe-enriched ToMOCox and 1.66 mM 57Fe-enriched ToMOCox treated with 10 equiv DEANO were loaded into 3 × 7 × 1 mm3 (interior dimensions) Lucite sample cells encased in Kapton tape. Samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C for four days prior to shipping. To confirm that the integrity of the DEANO-treated 57Fe-enriched ToMOCox sample was maintained over the time between preparation and measurement, the 77 K EPR spectra of small aliquots of the reaction mixture diluted 7.5-fold and used as-is or treated with 14 equiv of Na2S2O4 were recorded concomitantly with the NRVS spectrum. 57Fe NRVS spectra were recorded using published procedures48,49 at beamline BL09XU at Spring-8, Japan. Flux were on the order of 1.2 × 109 photons/sec in a 0.9 meV bandpass. During data collection the sample was maintained at low temperature using a liquid He cyrostat (head temperature < 10 K). Accurate sample temperatures were calculated from the ratio of anti-Stokes to Stokes intensity by the expression S(-E) = S(E)e(-E/kT) and were ∼ 80 K. Delayed nuclear fluorescence and delayed Fe K fluorescence were recorded with an avalanche photodiode array. Spectra were recorded between -240 and 740 cm-1. The data recorded for the DEANO-treated ToMOCox sample represent the sum of 30 65-min scans. Scans were normalized to the intensity of the incident beam and then averaged according to their cts/s signal level. Partial vibrational density of states (PVDOS) were calculated from the raw NRVS spectra using the PHOENIX Software package.50

Stopped-Flow Optical Spectroscopy

Stopped-flow optical spectroscopic experiments were performed on a Hi-Tech Scientific (Salisbury, UK) SF-61 DX2 instrument. Reactions of 40 μM ToMOCox with DEANO were carried out by rapidly mixing anaerobic solutions of protein with DEANO dissolved in KPi. DEANO solutions were allowed to stand at room temperature for at least one half-life, as designated by the manufacturer, to ensure that the kinetics events monitored resulted from the inherent reactivity of the cluster with NO and not from slow release of NO from the NONOate. Although it is possible that, under these conditions, NO is still released from the NONOate during the course of the experiment, the change in concentration resulting from such a process is negligible compare with the overall concentration of NO employed. The data were therefore satisfactorily fit without accounting for this possibility. Data were recorded at 362 and 459 nm using a photomultiplier tube. The temperature for all experiments was maintained at 25 °C using a circulating water bath. Data analyses were performed with Origin v. 6.1 (OriginLab Corporation) software and data fits were evaluated on the basis of the goodness-of-fit χ2red value, the fit residuals, and the parameter errors. Data collected at 362 and 459 nm were fit simultaneously using fixed rate constant parameters to ensure that model used in the analysis appropriately described the events occurring at both wavelengths. Data were fit well using the three exponential function y = A1exp(-kobs1*t) + A2exp(-kobs2*t) + A3exp(-kobs3*t) + Abst=∞ where t is time, A1, A2, A3 and are the pre-exponential factors for the three processes, kobs1, kobs2, and kobs3 are the rate constants for the three processes, and Abst=∞ is the final absorbance value (black lines). Attempts to fit the data to a two exponential function describing two processes yielded poor fit statistics and residual plots.

Results

Reactions of ToMOC with NO and NO Donors

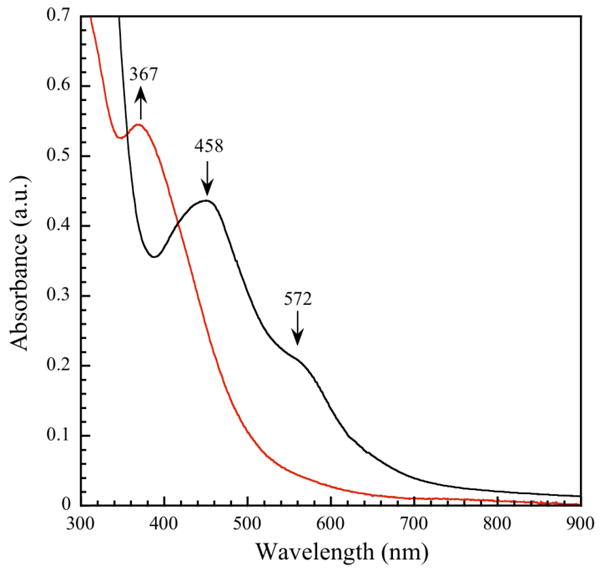

The optical spectrum of ToMOCox exhibits a broad band at 458 nm and a shoulder around 572 nm that are attributed to S-to-Fe(III) charge transfer transitions (Figure 2, black spectrum). As Na2S2O4 is added, these two peaks become less intense and three new maxima characteristic of reduced ToMOC appear at 380 nm, 420 nm, and 520 nm.44 After addition of 0.56 equiv of Na2S2O4, or 1.12 equiv of electrons, the spectra no longer change with increasing dithionite concentration, indicating complete reduction of the iron-sulfur cluster (Figure S1). These optical features of ToMOCox and ToMOCred were used as benchmarks to determine whether the various redox states of the cluster undergo reaction with NO (g) and NO donors such as DEANO and SNAP under anaerobic conditions.

Figure 2.

UV-vis spectra before (black) and after (red) incubation of 57 μM ToMOCox with 20 equiv of DEANO at 25 °C in 25 mM KPi buffer, pH 7.0 for 90 min.

Upon addition of excess (20 equiv) DEANO (Figure 2) or SNAP (Figure S2) to an anaerobic solution of ToMOCox, the charge transfer bands of ToMOCox bleached, consistent with cluster disassembly. When the reaction was complete, as judged by no further changes in the spectrum, a new optical feature indicative of an iron dinitrosyl species was evident at 367 nm (Figure 2, red spectrum).51-53 Several isosbestic points were observed at distinct time points during the course of the reaction pathway, indicating the presence of multiple sequential intermediate species.

Stoichiometric reactions of ToMOCox with NO derived from DEANO revealed optical changes similar to those for reactions performed with excess DEANO (Figure S3). Spectra collected after incubation with 1 or 2 equiv of NO from DEANO appeared identical to those collected at early time points during reactions with excess DEANO, indicating that either the reactions result in only partial disassembly of the [2Fe-2S] cluster or that the spectra correspond to intermediate species along the reaction pathway. Similar spectra were obtained from reactions of ToMOCox with excess NO (g) (Figure S4), although it is conceivable that the concentration of nitric oxide dissolved in solution was substantially less in experiments employing NO (g) than in those employing the NO donors, SNAP, and DEANO.

Anaerobic addition of excess DEANO to ToMOCred yielded a final product with an optical spectrum nearly identical to that resulting from the analogous reaction with ToMOCox, suggesting the same iron dinitrosyl species formed in both reactions (Figure S5). Reaction of ToMOCred with DEANO is more complicated and seems to proceed through an even greater number of intermediate species than the reaction with ToMOCox. It therefore appears that, whereas both reactions yield the same product, the mechanism of its formation depends on the redox state of the cluster.

EPR spectroscopy was employed to further characterize the products, hereafter ToMOCNO, of the reactions of ToMOCox and ToMOCred with NO and NO donors. Whereas ToMOCox is EPR-silent due to antiferromagnetic coupling between the iron atoms, ToMOCred displays a broad rhombic signal having gx = 2.01, gy = 1.92, and gz = 1.76 at 77 K (Figure S6). The observed spectrum is similar to those of other reduced Rieske centers,54,55 and consistent with a valence trapped Fe(II)/Fe(III) system in which the Fe(II) ion is coordinated to the histidine residues.54,56,57

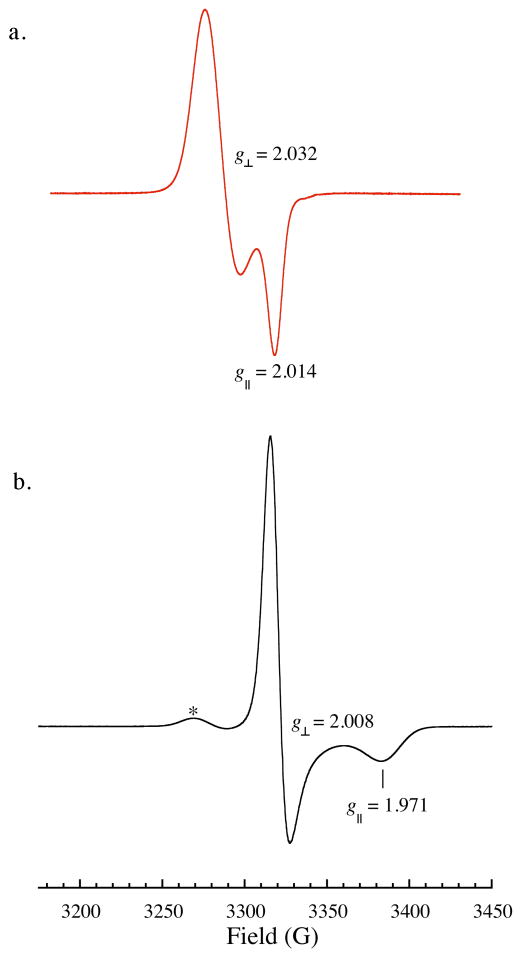

Anaerobic treatment of ToMOCox with excess DEANO (Figure 3a), SNAP (Figure S7), or NO (g) (Figure S8) for 1 h at 25 °C resulted in an axial S = ½ EPR signal with g⊥ = 2.032 and g‖ = 2.013 at 77 K. This type of signal is characteristic of a thiolate-bound {Fe(NO)2}9 DNIC23 and suggests the formation of such a species during the reaction. Double integration of the signals from multiple experiments employing DEANO, SNAP, or NO gas indicated that the DNIC is present in at most 20% of the total iron concentration. Treatment of ToMOCred with excess DEANO yielded the same EPR signal, which integrated to 7% of the total iron concentration (Figure S9). The resulting spectrum did not show any features indicative of ToMOCred, indicating complete consumption of the original {Fe2S2}1+ cluster.

Figure 3.

(a) 77 K X-band EPR spectrum of ToMOCNO prepared by incubating 250 μM ToMOCox with 10 equiv DEANO for 1 h at 25 °C. (b) 77 K EPR spectrum of (a) treated with 1 equiv of Na2S2O4; the asterisk denotes a small amount of signal from (a). Instrument parameters: 9.332 GHz microwave frequency; 0.201 mW microwave power; 5.02 × 103 receiver gain for (a), 1.00 × 103 for (b); 100.0 kHz modulation frequency; 8.00 G modulation amplitude; 40.960 ms time constant.

Zero-field 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy was also employed to study reactions of ToMOC with NO. The Mössbauer spectrum of ToMOCox recorded at 90 K consists of two nested quadrupole doublets of narrow Lorentzian line shape (Γ = 0.32(2) mm/s for subsite 1 and 0.28(2) for subsite 2) that account for all of the iron in the sample (Figure S10). Data analysis using a least-squares fitting algorithm returned the parameters δ = 0.25(2) mm/s and ΔEQ = 0.54(2) mm/s for subsite 1 and δ = 0.34(2) mm/s and ΔEQ = 1.11(2) mm/s for subsite 2. These values are identical to those of several well-characterized Rieske proteins, including closely related T4moC.54,55 Tetrahedral iron(III) coordinated by sulfur-based ligands such as thiolate and sulfide typically display isomer shifts between 0.20 and 0.30 mm/s.54 We therefore assign subsite 1 as the cysteine-bound iron atom. Larger isomer shifts are characteristic of mixed histidine/sulfide coordination, and subsite 2 therefore represents the histidine-bound iron atom.54,55

The zero-field 230 K 57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of ToMOCred generated by anaerobic incubation of ToMOCox with 0.54 equiv of Na2S2O4 contains two quadrupole doublets that account for all of the iron in the sample (Figure S11). At lower temperatures, the lines broaden appreciably due to magnetic hyperfine interactions, and two unresolved envelopes are observed (data not shown). However, at 230 K, the spin relaxation rate is fast and magnetic hyperfine interactions are averaged, leading to two resolved quadrupole doublets.54 Data analysis using a least-squares fitting algorithm revealed that δ = 0.65(2) mm/s and ΔEQ = 2.92(2) mm/s for the histidine-bound ferrous site and δ = 0.23(2) mm/s and ΔEQ = 0.69(2) mm/s for the cysteine-ligated ferric site. These parameters are again identical to those of several well-characterized Rieske proteins.54,55 Although the lineshapes of these doublets are narrow enough to obtain a good data fit, Γ = 0.32(2) mm/s for the Fe(II) site and 0.40(2) for the Fe(III) site, the latter doublet is significantly broadened by nuclear relaxation at 230 K.54

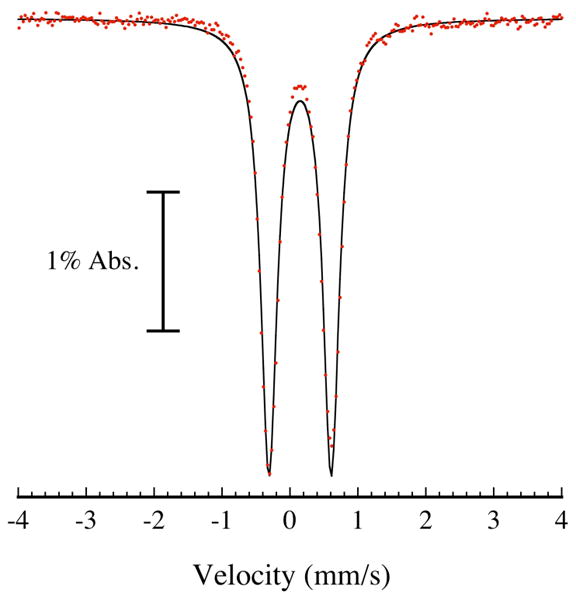

The zero-field 90 K 57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of ToMOCox treated with 34 equiv of DEANO displays a single quadrupole doublet with a narrow linewidth, Γ = 0.29(2) mm/s, which accounts for all of the iron in the sample (Figure 4). Data analysis using a least-squares fitting algorithm revealed that δ = 0.15(2) mm/s and ΔEQ = 0.92(2) mm/s. These parameters are strongly indicative of iron dinitrosyl species,52,53 although its exact nature cannot be definitively assigned because the Mössbauer parameters of various iron dinitrosyls are similar (Table S1).37 The presence of a single quadrupole doublet indicates that both iron atoms of the [2Fe-2S] cluster are converted to an iron dinitrosyl species. In light of the results from the EPR quantitations (vide supra), these Mössbauer spectroscopic experiments demonstrate that dinitrosyl iron species other than the DNIC must account for the most of the iron in the reaction products.

Figure 4.

77 K Mössbauer spectrum (red points) of the iron dinitrosyl species formed from reaction of 711 μM 57Fe-enriched ToMOCox with 34 equiv DEANO for 1 h at 25 °C in 25 mM KPi buffer, pH 7.0. Data were fit to a single quadrupole doublet with δ = 0.15(2) mm/s, ΔEQ = 0.92(2) mm/s, and Γ = 0.29(1) mm/s (black line).

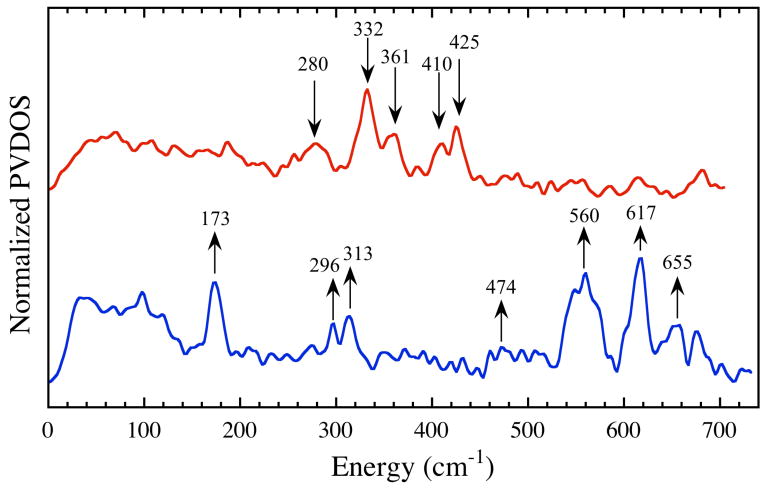

To gain further insight into the nature of the iron dinitrosyl species in ToMOCNO, we employed 57Fe nuclear resonance vibrational spectroscopy (NRVS). The NRVS spectrum of 57Fe-enriched ToMOCox contains four well-resolved peaks in the region between 300 and 450 cm-1 and a weaker signal near 280 cm-1(Figure 5, red). The four most intense peaks, located at 332, 361, 410, and 425 cm-1, are very similar in energy and relative intensity to the asymmetric and symmetric Fe–S stretching modes observed in the NRVS spectra of [2Fe-2S] ferredoxins from Rhodobacter capsulatus and Aquifex aeolicus.58 Moreover, these peaks correspond well to those assigned as Fe–S normal modes in resonance Raman spectra of the related T4moC protein.59 The weaker absorbance at ∼280 cm-1 is probably due to a mode involving a terminal ligand (His or Cys), although there is probably a large degree of coupling between these modes and those of the bridging sulfide ligands.59

Figure 5.

57Fe partial vibrational density of states (PVDOS) NRVS spectra of 1.56 mM 57Fe-enriched ToMOCox (red) and 1.66 mM 57Fe-enriched ToMOCox treated with 10 equiv of DEANO for 1 h at 25 °C in 25 mM KPi buffer, pH 7.0 (blue).

Upon treatment of 57Fe-enriched ToMOCox with DEANO, the Fe–S modes disappear and three distinct new peaks are observed in the high-energy region between 500 and 700 cm-1 (Figure 5, blue line). These peaks, located at ∼560, 617, and 655 cm-1, are attributed to normal vibrational modes involving the nitrosyl ligands, which arise from a bend and asymmetric and symmetric stretches of the N—Fe—N atoms of the {Fe(NO)2}9 unit.37,60 Comparisons of these peak intensities and energies to those of several previously characterized iron dinitrosyl synthetic compounds, including synthetic models of DNIC ((Et4N)[Fe(NO)2(SPh)2]), RRE ([Fe2(μ-SPh)2(NO)4]), and RBS ((Et4N)[Fe4(μ-S)3(NO)7]), species,37 indicate that the NRVS spectrum of the reaction product most closely matches that of a RRE (Figure S12). The spectral features do not overlap significantly with those of the DNIC model compound, further stressing that the paramagnetic, mononuclear DNIC is not the major iron dinitrosyl species formed in this chemistry.

Reduction of the Iron Dinitrosyl Species formed in the Reaction of ToMOC with excess NO

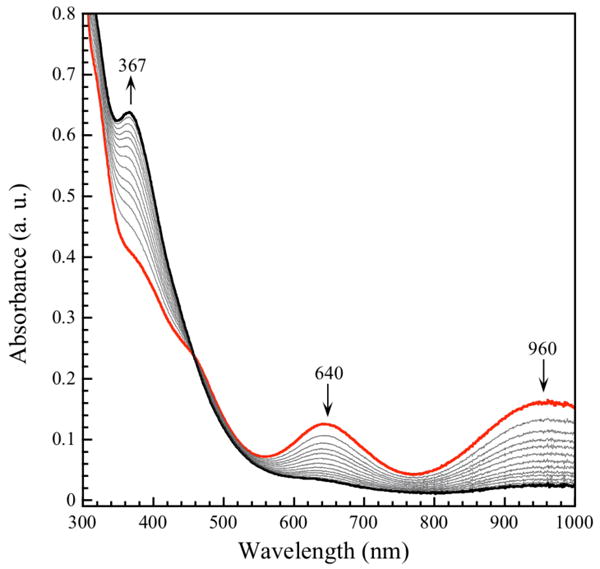

The reaction of ToMOCNO with an electron donor, Na2S2O4, was also investigated. We reasoned that reduction of diamagnetic (S = 0), EPR-silent nitrosyl species formed in the reaction might yield an open shell product with a demonstrable paramagnetic resonance spectrum. Upon anaerobic addition of stoichiometric or excess sodium dithionite to ToMOCNO, the solution immediately turned from pale yellow to bright green and two new optical features at 640 and 960 nm appeared, which we attribute to the one-electron reduced Roussin's red ester species (Figure 6, red).35-37 For reactions performed with stoichiometric or excess (4 equiv of electrons) reducing agent, these optical features bleached over the course of 10 or 90 min, respectively, and the initial ToMOCNO spectrum, having λmax = 367 nm, reappeared (Figure 6, black spectrum). These results indicate reversible formation of the RRE. Similar results were obtained upon addition of one electron to the DEANO-treated ToMOCox sample, although the rRRE species decayed more rapidly in this instance. For the latter case, addition of a second electron to the reaction mixture after decay of the rRRE spectrum resulted in regeneration of the green rRRE species, but the decay process was an order of magnitude slower than after the first electron addition (Figure S13). The nature of the oxidant and mechanism of decay of the rRRE species are unknown at this time, but may correspond to reduction of adjacent protein residues such as cystines. Because ToMOC has six highly flexible cysteine residues, we propose that oxidation of the rRRE may be affected by nearby disulfide bonds. If these oxidants were utilized, the decay process would become much slower.

Figure 6.

UV-vis spectral changes associated with the decay of reduced iron dinitrosyl species formed by addition of 2 equiv of Na2S2O4 to a mixture of 79 μM ToMOCox and DEANO at 25 °C in 25 mM KPi buffer, pH 7.0. Data show the spectra 2 min after addition of reductant (red) and at various intervals until reaction completion after 80 min (black).

The 77 K EPR spectrum of reduced ToMOCNO displays an axial signal with g⊥ = 2.011 and g‖ = 1.971 (Figure 3b). As with the optical features, these values are characteristic of the rRRE.35-37 A small peak at g = 2.04 attributed to the original DNIC signal is also present, indicating that this species was not completely eliminated by treatment with Na2S2O4. This observation indicates at least partial reduction of the {Fe(NO)2}9 unit. Upon addition of reducing equivalents, the DNIC could transform to an EPR-inactive {Fe(NO)2}10 species. Such a species would probably be histidine-bound to stabilize the increased electron density at iron. Alternatively, reduction could result in reaction of a putative thiolate-bound {Fe(NO)2}10 species with a neighboring DNIC unit to generate the more thermodynamically stable rRRE unit. Spin quantitation of the rRRE signal indicates that the new peaks account for 70% of the total iron. The 90 K zero-field Mössbauer spectrum of a sample of the ToMOCNO treated with 1 equiv of Na2S2O4 displays a single quadrupole doublet with δ = 0.15(2) mm/s, ΔEQ = 0.83(2) mm/s, and Γ = 0.31(2) mm/s (Figure S14). These parameters demonstrate that the integrity of the dinitrosyl iron is preserved upon reduction, because only one quadrupole doublet is observed. Given the similarity in isomer shift and quadrupole coupling parameters between the RRE and rRRE37 and the propensity for the latter to oxidize, Mössbauer data for reduced ToMOCNO cannot be used to definitely assign this species (Table S1).

Kinetics of ToMOC Iron Dinitrosyl Formation

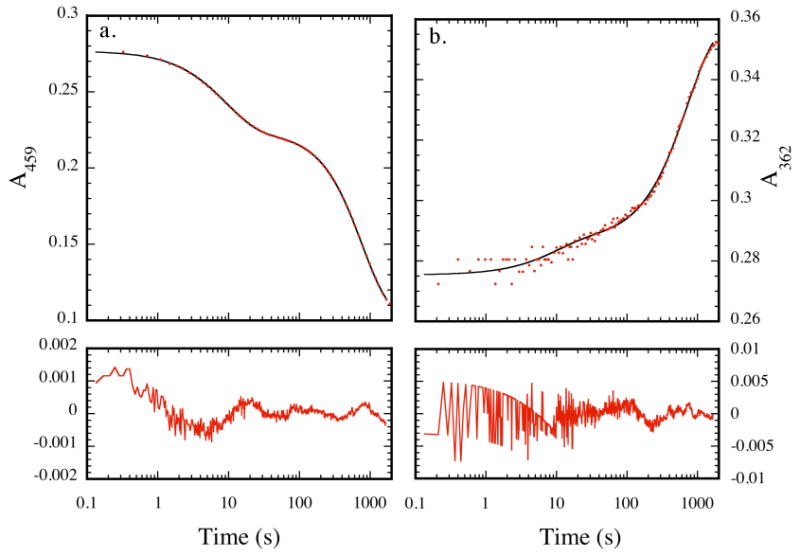

Using stopped-flow kinetic techniques, changes in the optical bands at 459 and 362 nm were followed over the course of ∼40 min under pseudo-first order conditions (> 10 fold excess of DEANO) after mixing ToMOCox and DEANO. These bands, which correspond to the iron-sulfur cluster (459 nm) and the dinitrosyl iron (362 nm) species, provide a means to examine both cluster degradation and iron dinitrosyl formation (Figure 7). Data from the two wavelengths, fit simultaneously to kinetic models, were best described by a three exponential process characterized by three distinct kinetic rate constants. Variation of the DEANO concentration resulted in a corresponding change in all three rate constants, revealing that each process is NO-dependent (Table S2). A linear relationship between kobs and [DEANO] was observed for concentrations below 2 mM. Above 2 mM the concentration of NO in aqeous solution saturates,61 and the observed rate constants level off with increasing [DEANO] (Figure S15). Decay of the band at 459 nm was associated with all three processes, indicating that cluster decomposition is not complete until the final kinetic phase (Figure 7a). In contrast, the band at 362 nm was associated only with the slowest phase of the process, indicating that formation of the iron dinitrosyl species with λmax at this wavelength corresponds only to the final reaction process (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Representative stopped-flow absorbance profiles (red points) for the reaction of 40 μM ToMOCox with 150 equiv DEANO in 25 mM KPi buffer, pH 7.0, at 25 °C at 459 nm (a) and 362 nm (b). Data were analyzed as described in the text. Residual plots are shown in the bottom panels of (a) and (b).

Discussion

Reactions of nitric oxide with cysteine-coordinated iron-sulfur clusters have been extensively investigated due to their importance in physiological signal transduction and NO-mediated pathology. DNIC products of these reactions have been proposed to regulate a variety of biological processes. The working hypothesis that mononuclear DNICs are the major species responsible for the effects of biological iron nitrosyls has been called into question as more complete characterization of the reaction products has been achieved. The present results contribute to this paradigm shift.

Characterization of RRE as the Primary Product in the Reaction of the Rieske Protein ToMOC with excess NO

The results of UV-visible, EPR, 57Fe-Mössbauer, and 57Fe-NRVS spectroscopic experiments conclusively demonstrate [2Fe-2S] cluster degradation and formation of iron dinitrosyl species upon treatment of ToMOCox with a slight excess of NO, providing the first evidence that iron dinitrosyls can form at biological Rieske centers. Although EPR spectroscopy has been used historically as the primary tool for identification of DNICs, a major limitation of this technique is that S = 0 EPR-inactive species including RRE and RBS are not detected if formed. The various spectroscopic methods employed here indicate that iron dinitrosyl species form in 100% yield from the reaction of ToMOCox with excess NO. Integration of the observed DNIC EPR signal clearly shows that this species is not the predominant reaction product. Rather, the RRE appears to be the major product, as judged by Mössbauer and NRVS spectroscopy. Further evidence for RRE as the major species is provided by experiments in which ToMOCNO was treated with Na2S2O4. This reaction generated optical and EPR signatures that are distinctive for a rRRE, the formation of which most likely results from reduction of the corresponding RRE.35-37 This experiment thus provides indirect evidence that ToMOCNO is a RRE species.

Spectral features similar to those observed here have previously been attributed to reduction of a {Fe(NO)2}9 DNIC (termed a “d7 DNIC”) to generate a “d9 DNIC”.18,24 Recent work has shown, however, that the d9 DNIC is in fact a rRRE.35,36 The agreement between the spectroscopic properties of the species observed here with those of synthetic rRRE complexes of known structure suggests that these features arise from the red ester rather than a reduced mononuclear DNIC.

In the present study, integration of the rRRE EPR signal from several experiments indicates that this species is produced in yields as high as 70%. This fact further implies that the RRE forms in comparable yields. The remaining ∼30% of iron that is not accounted for by either the DNIC or the rRRE signal could be due to an EPR silent species, such as a histidine-ligated {Fe(NO)2}10 DNIC, or the iron-sulfur nitrosyl cluster, Roussin's black salt (RBS, Chart 1). The amount of iron dinitrosyl species formed may depend on the relative concentrations of NO and iron sulfur cluster employed, both in vitro or available in a cellular context. In the noted studies, we used a modest excess of NO, conditions that may pathophysiological conditions in which a burst of nitric oxide reacts with an iron sulfur protein present at sub-milimolar concentrations.

Nature of DNIC Species Formed in the Reaction of ToMOC with excess NO

The Rieske-type ferredoxin offers the possibility that a DNIC might form at either or both of the cysteine- and histidine-ligated iron atoms. Although biological DNICs typically feature cysteine thiolate ligation, there is also evidence for DNICs with O/N coordination in proteins. Exposure of the [3Fe-4S] form of mitochondrial aconitase to NO resulted in DNIC formation and migration of the resulting {Fe(NO)2}9 species to a histidine residue, presumably to form a mixed cysteine/histidine unit.24 Histidine- and carboxylate-coordinated DNICs have also been observed in the reaction of NO with mammalian ferritins.62 Treatment of bovine serum albumin with [Fe(NO)2(L-cysteine)2] resulted in transfer of the DNIC to surface histidine residues on the protein.63 Recently we reported that a synthetic model of a Rieske cluster reacts with NO to form both sulfur- and nitrogen-ligated DNIC species, although the nitrogen-based ligand used in these studies was anionic and better able to stabilize DNICs than neutral histidine residues.40 The present EPR data indicate that only cysteine-bound DNIC species form in the reaction of ToMOC with NO. There is no evidence for histidine-bound DNICs, which are distinguishable from cysteine-bound DNICs by their EPR parameters.24 The possibility that the {Fe(NO)2}10 unit formed upon treatment of ToMOCNO with dithionite is transferred to the histidine ligands cannot be ruled out, given the precedence for stabilization of such a DNIC redox state by imidazole ligands.64

Mechanism of Formation of Iron Dinitrosyl Species

One aspect of biological iron-sulfur NO chemistry that remains largely ill-defined is the mechanism by which the clusters transform into iron dinitrosyl species. Some insight is provided by synthetic biomimetic chemistry involving simple homoleptic iron thiolates. Studies with these compounds demonstrated the intermediacy of a mononitroysl iron complex (MNIC) along the pathway from [Fe(SR)4]2-/1- to DNIC.65,66 Analogous reactions with synthetic [2Fe-2S] and [4Fe-4S] clusters also yield DNICs but no intermediates have yet been identified.67,68 Previous work from our laboratory with a synthetic analog of a Rieske cluster revealed that both N-bound and S-bound DNICs are produced upon reaction with NO.40 This reactivity is analogous to that described for purely thiolate-bound [2Fe-2S] clusters and suggests a generality in the reactivity of the {Fe2S2}2+ core toward nitric oxide.

In contrast to results with the synthetic Rieske cluster, we find here no evidence for formation of histidine-bound DNICs with ToMOC. Moreover, formation of cysteine-bound DNICs accounts for only a small fraction of the total nitrosylated iron, with most of the iron converting to the dinuclear RRE (vide supra). Investigation of the kinetics of the reaction indicates that several intermediate species are produced during disassembly of the iron-sulfur cluster. The kinetic data are best fit by a three-exponential process, with each rate constant depending on DEANO concentration. We cannot at this time assign specific structures to these discrete intermediates along the pathway from [2Fe-2S] cluster to RRE, although it is likely that at least one of these intermediates corresponds to a mononitrosyl iron species. Because the optical spectra of the reaction products of ToMOCox with stoichiometric NO generated by DEANO (Figure S3) are identical to those observed at early time points during reaction with excess DEANO (Figure 2), it might be possible to trap and characterize intermediates along the pathway to cluster degradation. Experiments to test this possibility will provide important mechanistic information and will form the basis for future work in our laboratory.

Implications for Other Iron-Sulfur Systems

Previous reports have associated the biological consequences of NO reactivity with [2Fe-2S] and [4Fe-4S] clusters with the formation of mononuclear DNIC species. Such DNICs are probably the focus of such investigations due to their ease of detection by EPR spectroscopy. However, spin quantitation of the DNIC EPR signal in such reactions typically reveal that < 10% of the initial iron sites form DNICs even though complete cluster degradation occurs.2,5,24,40,69 Evidence from some of these earlier investigations implies that other types of iron dinitrosyl species might be formed during these reactions. A study probing the reaction of NO with FNR, a [4Fe-4S] transcription factor, estimated that < 20% of the iron originating from the [4Fe-4S] cluster formed a DNIC. The authors suggested RRE to be the major product, present in 80% yield, although there was no direct evidence for this species.70 rRREs have previously been shown to result from chemical reduction of the products of iron-sulfur cluster nitrosylation.18,24 Our results provide clear evidence that a RRE species is the major product formed in the reaction of the ToMOC Rieske center with NO. Given that treatment of cysteine-coordinated iron-sulfur clusters proceeds with relatively little DNIC formation but complete cluster degradation, it is likely that the major products of reaction are also Roussin's red ester species and that iron dinitrosyl species other the mononuclear DNIC are principally responsible for the observed in vitro and in vivo effects of iron-sulfur cluster nitrosylation.

Concluding Remarks

In this study we examined the reactivity of a prototypical Rieske protein with nitric oxide. Our results indicate that Rieske proteins react with NO and that dinuclear dinitrosyl iron species (RREs) are the predominant products formed. In light of these findings, we suggest that the dinuclear RRE, not the mononuclear DNIC, is responsible for many of the observed pathological and physiological consequences of iron-sulfur cluster nitrosylation. Further studies on a variety of different iron-sulfur proteins are necessary to test this hypothesis and explore its generality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grant GM032134 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS). SPC thanks the Department of Energy (DOE OBER) and the NIGMS (GM065440) for financial support. CET received partial support from the NIGMS under Interdepartmental Biotechnology Training Grant T32 GM08334. Z. J. T. thanks the NIGMS for a postdoctoral fellowship (1 F32 GM082031-03).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Tables S1-S2 and Figures S1-S14 as described in the text. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

References

- 1.Prast H, Philippu A. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;64:51–68. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yukl ET, Elbaz MA, Nakano MM, Moënne-Loccoz P. Biochemistry. 2008;47:13084–13092. doi: 10.1021/bi801342x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Autréaux B, Tucker NP, Dixon R, Spiro S. Nature. 2005;437:769–772. doi: 10.1038/nature03953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D'Autréaux B, Touati D, Bersch B, Latour JM, Michaud-Soret I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16619–16624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252591299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding H, Demple B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5146–5150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strube K, de Vries S, Cramm R. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20292–20300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drapier JC, Pellat C, Henry Y. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:10162–10167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lancaster JR, Hibbs JB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1223–1227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.3.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bogdan C. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:907–16. doi: 10.1038/ni1001-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ignarro LJ, Buga GM, Wood KS, Byrns RE, Chaudhuri G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:9265–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derbyshire ER, Marletta MA. cGMP: Generators, Effectors and Therapeutic Implications. 2009. pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radi R. Chem Res in Toxicol. 1996;9:828–835. doi: 10.1021/tx950176s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stamler JS. Cell. 1994;78:931–936. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bosworth CA, Toledo JC, Jr, Zmijewski JW, Li Q, Lancaster JR., Jr Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4671–4676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710416106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren B, Zhang N, Yang J, Ding H. Mol Microbiol. 2008;70:953–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asanuma K, Iijima K, Ara N, Koike T, Yoshitake J, Ohara S, Shimosegawa T, Yoshimura T. Nitric Oxide. 2007;16:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reddy D, Lancaster JR, Jr, Cornforth DP. Science. 1983;221:769–70. doi: 10.1126/science.6308761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foster MW, Cowan JA. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:4093–4100. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Commoner B, Ternberg JL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1961;47:1374–1384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.47.9.1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woolum JC, Tiezzi E, Commoner B. Biochim Biophys Acta-Protein Struct. 1968;160:311–320. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(68)90204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vanin AF, Serezhenkov VA, Mikoyan VD, Genkin MV. Nitric Oxide. 1998;2:224–234. doi: 10.1006/niox.1998.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Enemark JH, Feltham RD. Coord Chem Rev. 1974;13:339–406. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butler AR, Megson IL. Chem Rev. 2002;102:1155–1165. doi: 10.1021/cr000076d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kennedy MC, Antholine WE, Beinert H. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20340–20347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sellers VM, Johnson MK, Dailey HA. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2699–2704. doi: 10.1021/bi952631p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duan X, Yang J, Ren B, Tan G, Ding H. Biochem J. 2009;417:783–789. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogers PA, Eide L, Klungland A, Ding H. DNA Repair. 2003;2:809–817. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(03)00065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vanin AF, Stukan RA, Manukhina EB. Biochim Biophys Acta-Protein Struct. 1996;1295:5–12. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(95)00247-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vedernikov YP, Mordvintcev PI, Malenkova IV, Vanin AF. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;211:313–317. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90386-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vanin AF. Nitric Oxide. 2009;21:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lobysheva II, Stupakova MV, Mikoyan VD, Vasilieva SV, Vanin AF. FEBS Lett. 1999;454:177–180. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00777-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stupakova MV, Lobysheva II, Mikoyan VD, Vanin AF, Vasilieva SV. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2000;65:690–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiegant FAC, Malyshev IY, Kleschyov AL, van Faassen E, Vanin AF. FEBS Lett. 1999;455:179–182. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00806-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butler AR, Glidewell C, Li MH. Adv Inorg Chem. 1988;32:335–93. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu TT, Tsou CC, Huang HW, Hsu IJ, Chen JM, Kuo TS, Wang Y, Liaw WF. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:6040–6050. doi: 10.1021/ic800360m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsou CC, Lu TT, Liaw WF. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12626–12627. doi: 10.1021/ja0751375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tonzetich ZJ, Wang H, Mitra D, Tinberg CE, Do LH, Jenney FE, Adams MWW, Cramer SP, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6914–6916. doi: 10.1021/ja101002f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lippard SJ, Berg JM. Principles of Bioinorganic Chemistry. University Science Books; Mill Valley, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beinert H, Holm RH, Münck E. Science. 1997;277:653–659. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5326.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tonzetich ZJ, Do LH, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7964–7965. doi: 10.1021/ja9030159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Welter R, Yu L, Yu CA. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;331:9–14. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skjeldal L, Peterson F, Doreleijers J, Moe L, Pikus J, Westler W, Markley J, Volkman B, Fox B. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2004;9:945–953. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0594-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cladera AM, Sepúlveda-Torres LdC, Valens-Vadell M, Meyer JM, Lalucat J, García-Valdés E. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2006;29:422–430. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cafaro V, Scognamiglio R, Viggiani A, Izzo V, Passaro I, Notomista E, Piaz FD, Amoresano A, Casbarra A, Pucci P, Di Donato A. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:5689–5699. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lorković IM, Ford PC. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:632–633. doi: 10.1021/ic9910413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lambeth DO, Palmer G. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:6095–6103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kent, T. A.; WEB Research Co.: Minneapolis, MN, 1998.

- 48.Smith MC, Xiao Y, Wang H, George SJ, Coucouvanis D, Koutmos M, Sturhahn W, Alp EE, Zhao J, Cramer SP. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:5562–5570. doi: 10.1021/ic0482584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiao Y, Fisher K, Smith MC, Newton WE, Case DA, George SJ, Wang H, Sturhahn W, Alp EE, Zhao J, Yoda Y, Cramer SP. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7608–7612. doi: 10.1021/ja0603655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sturhahn W. Hyperfine Interact. 2000;125:149–172. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Costanzo S, Menage S, Purrello R, Bonomo RP, Fontecave M. Inorg Chim Acta. 2001;318:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 52.D'Autréaux B, Horner O, Oddou JL, Jeandey C, Gambarelli S, Berthomieu C, Latour JM, Michaud-Soret I. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6005–6016. doi: 10.1021/ja031671a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lobysheva II, Serezhenkov VA, Stucan RA, Bowman MK, Vanin AF. Biochemistry (Moscow) 1997;62:801–808. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fee JA, Findling KL, Yoshida T, Hille R, Tarr GE, Hearshen DO, Dunham WR, Day EP, Kent TA, Münck E. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:124–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pikus JD, Studts JM, Achim C, Kauffmann KE, Munck E, Steffan RJ, McClay K, Fox BG. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9106–9119. doi: 10.1021/bi960456m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ballmann J, Albers A, Demeshko S, Dechert S, Bill E, Bothe E, Ryde U, Meyer F. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:9537–9541. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bertrand P, Guigliarelli B, Gayda JP, Beardwood P, Gibson JF. Biochim Biophys Acta, Protein Struct Mol Enzymol. 1985;831:261–6. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xiao Y, Tan ML, Ichiye T, Wang H, Guo Y, Smith MC, Meyer J, Sturhahn W, Alp EE, Zhao J, Yoda Y, Cramer SP. Biochemistry. 2008;47:6612–6627. doi: 10.1021/bi701433m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rotsaert F, Pikus J, Fox B, Markley J, Sanders-Loehr J. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2003;8:318–326. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0417-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dai RJ, Ke SC. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:2335–2346. doi: 10.1021/jp066964f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Armor JN. J Chem Eng Data. 1974;19:82–84. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee M, Arosio P, Cozzi A, Chasteen ND. Biochemistry. 1994;33:3679–3687. doi: 10.1021/bi00178a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boese M, Mordvintcev PI, Vanin AF, Busse R, Mülsch A. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29244–29249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reginato N, McCrory CTC, Pervitsky D, Li L. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:10217–10218. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lu TT, Chiou SJ, Chen CY, Liaw WF. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:8799–8806. doi: 10.1021/ic061439g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harrop TC, Song D, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3528–3529. doi: 10.1021/ja060186n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harrop TC, Tonzetich ZJ, Reisner E, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:15602–15610. doi: 10.1021/ja8054996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsai FT, Chiou SJ, Tsai MC, Tsai ML, Huang HW, Chiang MH, Liaw WF. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:5872–5881. doi: 10.1021/ic0505044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Foster MW, Liu L, Zeng M, Hess DT, Stamler JS. Biochemistry. 2009;48:792–799. doi: 10.1021/bi801813n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cruz-Ramos H, Crack J, Wu G, Hughes MN, Scott C, Thomson AJ, Green J, Poole RK. EMBO J. 2002;21:3235–3244. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.