Abstract

Adolescent marriage is common in India, placing young women at risk of HIV, early pregnancy, and poor birth outcomes. Young women’s capacity to express their sexual desires is central to negotiating safe and mutually consensual sexuality. Men too play an important role in shaping women’s sexual and reproductive health outcomes, but little research has examined how men influence women’s sexual expression. Using paired husband and wife data, this paper reports on a preliminary investigation into the patterns of and concurrence between women’s sexual expression and their husbands’ attitudes about it, as well as the influence of men’s approval of their wives’ sexual expression on women’s actual expression of sexual desire. The results suggest that among this sample, men are more open to sexual expression than their wives and that for women, expressing desire not to have sex is far more common than expressing desire to have sex. Further, men’s approval of sexual expression from wives appears to positively influence women’s actual expression. These findings suggest that men may be resources for women to draw upon as they negotiate sexuality in adolescence and early adulthood.

Keywords: Sexual expression, India, reproductive health, young women

Introduction

Young women in India face considerable challenges to their sexual and reproductive health (International Institute for Population Sciences 2007). Early marriage remains common, with nearly six in 10 women aged 20–49 married by age 18, and the median age at first sexual intercourse among 20–24 year-olds is 17.8 years (International Institute for Population Sciences 2007). Marriage and sexual activity during adolescence and early adulthood places girls at increased risk for contracting HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STI), for early or unintended pregnancy, and for poor birth outcomes (Krishnan et al. 2005).

Men’s influence on women’s reproductive health

Men’s behaviours, attitudes, and decision-making regarding reproductive health have been shown to exert considerable influence over women’s contraceptive use, fertility, STI and HIV transmission, and reproductive health decision-making in a variety of settings (Bankole 1995;Becker, Fonseca-Becker, and Schenck-Yglesias 2006;Blanc 2001;Derose and Ezeh 2005;Mason and Smith 2000). Couple communication and gender norms that lead to inequities between men and women have been increasingly studied as two mechanisms through which men influence women’s reproductive health (Blanc 2001). In many contexts, couples’ communication, or lack thereof, about reproductive matters appears to be a central pathway through which husbands’ attitudes determine reproductive health outcomes (Blanc 2001). Many studies find considerable disagreement between husband and wife on objective reproductive outcomes, such as the number of pregnancies or live births experienced (Becker 1996;Becker, Fonseca-Becker, and Schenck-Yglesias 2006;Mason and Smith 2000) and in terms of subjective components of women’s lives, including mobility, access to resources, and decision-making (Allendorf 2007;Jejeebhoy 2002;Sathar and Kazi 1997). The discordance between couples in reporting actual events and beliefs about women’s autonomy suggests that couple communication is low in many settings, particularly for younger women (Blanc 2001). Such breakdowns in communication can prove destructive to women’s sexual and reproductive health when they mean that women cannot negotiate safe and desired sexual activity.

Patriarchal norms that subordinate women to men are also a pathway through which men’s preferences, attitudes and behaviours influence women’s reproductive health outcomes, in part because these norms can contribute to lack of couple communication (Blanc 2001). Such dynamics are highly context dependent, and men’s and women’s experience of these norms often change over the life course. Research in Nigeria, Ghana and Bangladesh has found that women have little power in childbearing negotiations during the early years of marriage, but as they grow older and become more established matriarchs their own childbearing preferences come to dominate those of their husbands’ (Bankole 1995;Derose and Ezeh 2005;Gipson and Hindin 2007). When comparing how men’s attitudes influence their wives’ contraceptive use in five South and Southeast Asian countries, Mason and Smith (2000) demonstrate that in societies where men maintain considerable control over their wives, husbands’ attitudes are more likely to influence women’s contraceptive use than in societies where women have greater control in their own lives. Even within India, where gender inequality is pervasive and men’s attitudes are recognized as important determinants of what is and is not acceptable for women, men’s preferences appear to exert stronger effect on women’s reproductive outcomes in regions with greater gender inequality (Jejeebhoy 2002;Sathar and Kazi 1997).

Women’s agency

Although men’s attitudes influence women’s sexual and reproductive outcomes, women’s own sexual agency – that is, their ability to make and act upon decisions in the sexual realm (Kabeer 1999;Pande et al. 2009) – may play an equally important role in determining sexual and reproductive health. Sexual agency can enable women to leverage equality in gender relations to achieve their reproductive desires by mediating the ways in which patriarchal norms influence sexual behaviours and facilitate resistance to traditional norms that may limit women’s reproductive and sexual decision-making (Blanc 2001). Agency is a key capability in terms of achieving improved sexual and reproductive health outcomes, as it enables women to practice contraception, control the timing of their childbearing and protect themselves from STI, HIV and unintended pregnancy (Jejeebhoy 2002).

In India, women exert little agency over their own sexuality, as norms mandating submissiveness and male control over women’s sexuality leave Indian women able to make few choices in the sexual sphere (Santhya and Jejeebhoy 2005). This normative context particularly disadvantages young women, who are constrained in their ability to negotiate protective measures for sex within marriage, such as condom or contraceptive use (George 2002;Joshi et al. 2001;Maitra and Schensul 2002), and can face increased risk of coercive sex (Jejeebhoy and Bott 2005;Koenig et al. 2008).

Although significant bodies of research have investigated the role of husbands’ preferences, attitudes and behaviour and the role of women’s sexual agency in determining sexual and reproductive health outcomes, fewer studies examine empirically the role of men in shaping women’s sexual agency. Disentangling how husband’s preferences shape women’s sexual agency can begin to identify areas for intervention with couples to decrease women’s vulnerability within marriage, delay childbearing, and prevent HIV and STI infection.

This paper aims to further understanding of how women’s ability to discuss and express sexuality with their husbands – one dimension of sexual agency -- is shaped by their husbands’ preferences for the type of sexual expression they wish their wives to demonstrate. We explore two primary questions: What are husbands’ opinions regarding wives’ sexual discussion and expression, and how does that compare to wives’ actual discussion and expression behaviours?; and, what effect do husbands’ preferences have on wives’ sexual expression?

Methodology

Study setting

This study is set in two low-income areas in Bangalore, the capital city of Karnataka state, which are home to almost 20 percent of Bangalore’s five million people (Nair 2005). While the municipal government classifies these areas as ‘slums,’ they are well established and have access to basic infrastructure, including electricity and health clinics. Economic development, driven by India’s information technology industry, has created momentum for social change; young women increasingly defy traditional norms by discussing who they will marry with elders, marrying later, and earning independent incomes (Krishnan 2005;Rocca et al. 2008). While these changes create opportunities for women to make some strategic choices related to their sexuality, patriarchal norms remain entrenched and manifest themselves in persistent domestic violence and taboos around discussion of sex and condom use (Krishnan, Pande, Sanghamitra, Mathur, Subbaih, Roca, Measham, and Anuradha 2005)(Krishnan, Pande, Sanghamitra, Mathur, Subbaih, Roca, Measham, & Anuradha 2005).

Data

This study uses matched husband-wife data drawn from baseline and midline surveys conducted in 2005 and 2006 as part of a prospective study on married women implemented between 2002 and 2008 (endline data collection occurred in 2007). A two-year qualitative data collection effort (2002 – 2004) preceded the baseline to inform the design of the quantitative survey, providing a nuanced picture of gender roles and marital sexual relations, decision-making, communication in the local context. The qualitative phase played central role in shaping the hypotheses in this study.

Women were recruited into the study using a convenience sample methodology, with women approached through two municipal primary health centres serving the study communities. This approach was selected both because the poorly defined lanes within these dense slum communities made random sampling challenging and costly, and because of the difficulty with soliciting such sensitive information through a standard household survey methodology. Both the qualitative phase and prior research suggested that women would be reluctant to discuss sexual behaviour and desires in settings where privacy could not be guaranteed, as would be the case if they were interviewed in their homes. Trained outreach workers recruited women in the two health centres and surrounding communities through door-to-door visits at women’s homes. Married females between 16 and 25 years of age, who spoke one of the local languages (Tamil or Kannada) fluently, and who anticipated residence in the community for the duration of the 2-year study were eligible for inclusion. Consent from parents or husbands, depending on who was available, was obtained for women under 18. The study protocol was approved by the human subjects protection committees of the University of California, San Francisco, RTI International, and the Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore.

All informed consent procedures and data collection were conducted at the primary health centres. Enrolled women participated in one-hour face-to-face interviews conducted by trained interviewers in private rooms in the health centres in either Tamil or Kannada. The baseline survey collected information on women’s socio-demographic characteristics, sources of social support, and decision-making. The midline survey collected follow-up information. Information was collected from 744 women in the baseline and 653 at midline. While it is unclear to what degree this sample is representative of the broader population in these two slums, both the qualitative data collected and NFHS data suggest our sample of women has similar characteristics as the general population of urban Karnataka, particularly in terms of parity, education, and more general social attitudes (International Institute for Population Sciences 2007)(International Institute for Population Sciences 2007). Further, 95% of urban women in Karnataka access antenatal care and most poor women obtain care in public facilities (International Institute for Population Sciences 2007;Mahal et al. 2001)(International Institute for Population Sciences 2007;Mahal et al. 2001). Taken together, we feel our recruitment efforts reached a similar population to that of the slum communities.

At baseline, a subset of participants’ husbands completed face-to-face interviews, during which trained male interviewers asked men similar questions to those answered by their wives. Husbands were eligible to participate if wives authorised the study team to contact them at both the woman’s baseline interview and at the actual time of the husband’s interview. At the first stage, 330 women authorised the study team to contact their husbands1. Of those, consent was obtained at the second opportunity from 304 women. The study team was unable to contact 87 husbands at the given address and a further 19 husbands refused to participate in the interview process. Data were collected from 198 husbands. The current study uses data from the couple dyads for whom midline data were also available (n=185).

The relatively low proportion of couples for which matched husband-wife data was collected raised the possibility that couples who participated may be in a more intimate or “progressive” relationship than the general population. To examine this issue, we compared women whose husbands were interviewed with those whose husbands were not across a range of characteristics, including those used as dependent variables in the multivariate analysis (Table 1). The results of this comparison suggest that while the groups are broadly similar, the two groups do differ significantly on two variables. Women whose husbands did not participate in the study were more likely to have known him prior to marriage (p-value=0.025); and women whose husbands completed the survey were more likely to have reported showing or telling their husbands they did not want to have sex in the last 6 months (p=0.049). While the lack of statistically significant differences for other variables measuring relationship quality and couple communication suggests that these results are not indicative of fundamental differences between the two groups, they do suggest the women included in the analyses may be somewhat different from the overall sample in terms of sexual communication, at least in terms of refusal of sex. In addition, there may be unobservable differences between the two groups that are not reflected in the measures used in this study. As a result, care should be taken in extrapolating these findings to other populations.

Table 1.

Key characteristics of women who did not authorise their husbands to be contacted for the study (n=468) and study women (n=185); married women ages 16–25 in Bangalore, India, 2005–2006. All data from baseline (2005) unless otherwise noted.

| Women without husbands in sample (n=468) |

Women with husbands in sample (n=185) |

Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | p-value | |

| Woman’s age | 22.39 | 0.107 | 22.33 | 0.165 | 0.766 |

| Husband’s age (woman’s report) | 27.66 | 0.177 | 27.64 | 0.262 | 0.940 |

| Marital Duration (years) | 4.43 | 0.133 | 4.33 | 0.214 | 0.678 |

| Parity | 1.72 | 0.051 | 1.56 | 0.083 | 0.103 |

| Household asset score | 0.01 | 0.047 | 0.04 | 0.072 | 0.711 |

| Women’s highest year of education (years) | 5.81 | 0.229 | 6.16 | 0.247 | 0.389 |

| Husband’s highest year of education (years) | 5.41 | 0.198 | 5.77 | 0.294 | 0.326 |

| N | Percent | N | Percent | p-value | |

| Couples’ Education | 0.474 | ||||

| Wife more educated | 81 | 17.31 | 37 | 20.00 | |

| Equal education | 294 | 62.82 | 118 | 63.78 | |

| Husband more educated | 93 | 19.87 | 30 | 16.22 | |

| Worked before married | 320 | 68.38 | 123 | 66.42 | 0.641 |

| Felt prepared for first sex | 47 | 10.04 | 20 | 10.81 | 0.771 |

| Husband lived in same area pre-marriage | 266 | 56.84 | 104 | 56.22 | 0.885 |

| Knew husband well pre-marriage | 258 | 55.13 | 84 | 45.41 | 0.025 |

| Husband primary source of social support (at midline) | 211 | 45.09 | 86 | 46.49 | 0.513 |

| Ever talked to husband about sex – wife’s report | 169 | 36.11 | 71 | 38.38 | 0.588 |

| Ever openly disagreed with husband – wife’s report | 302 | 64.53 | 123 | 66.49 | 0.636 |

| Language: Tamil | 329 | 70.30 | 126 | 68.11 | 0.583 |

| Violence | |||||

| Safe from physical violence in last 6 months | 338 | 72.22 | 143 | 77.30 | 0.185 |

| Physical violence status | 0.332 | ||||

| Never abused | 200 | 42.74 | 80 | 43.24 | |

| Abused greater than 6 months ago | 138 | 29.49 | 63 | 34.05 | |

| Abused in last 6 months | 130 | 27.78 | 42 | 22.70 | |

| Husband’s Work Status | |||||

| Currently working (woman’s report) | 454 | 97.01 | 177 | 95.68 | 0.495 |

| Worked in last 6 months (woman’s report) | 408 | 87.18 | 162 | 87.57 | 0.818 |

| Migrates for work (woman’s report) | 161 | 34.40 | 65 | 35.14 | 0.859 |

| Has a stable job (at midline) | 72 | 15.38 | 36 | 19.46 | 0.936 |

| Dependent variables: Sexual expression in last six months (midline) | |||||

| Showed or told husband she wants to have sex | 112 | 23.93 | 55 | 29.73 | 0.126 |

| Showed or told husband she does not want to have sex | 312 | 66.67 | 138 | 74.59 | 0.049 |

Measures and analytical approach

This study focuses on sexual expression as a dimension of women’s sexual agency and how this is shaped by husband’s preferences. We use the dyadic nature of the data to contrast and compare descriptively women’s and their husbands’ response patterns regarding sexual discussion and expression. We then explore the degree to which women’s expression reflects their husbands’ preferences using multivariate regression techniques. Together, these two approaches allow for a comprehensive assessment of the interplay between women’s behaviour and partner preferences in our sample.

We include three measures of sexual discussion and expression in our analyses, all reported by women themselves at midline (conducted in 2006). We consider “discussion” to be talking about sex generally and “expression” to be conveying preferences or desires. We measure discussion about sex with a dichotomous variable indicating whether women answered ‘yes’ to the question “In the last six months have you talked to your husband about having sex, for example when to have sex, how to have sex, what brings pleasure, what does not, and such things?” Our measures of sexual expression include one dichotomous measure of whether women reported telling or showing husbands that they wanted to have sex in the last 6 months and one dichotomous measure of whether women reported telling or showing husbands that they did not want to have sex in the last 6 months.

Measures of men’s preferences for their wives’ sexual discussion parallel women’s reported discussion and expression behaviours. Husbands were asked several yes/no questions on sexual expression from wives, including, “Do you feel it is ok for your wife to talk to you about having sex?”; “Would you like your wife to show you or tell you that she wants to have sex?”; and “Do you feel it is ok for your wife to show or tell you that she does NOT want to have sex with you?”. We create an additive four-category variable from these questions. Men who responded ‘no’ to all questions are coded as 0; men who responded positively to one question are coded as 1; and so on. These variables are all measured at baseline.

To supplement our descriptive analysis, we use multivariate logistic regression to model the effects of husbands’ preferences on the two dichotomous measures of women’s sexual expression. Because husband variables are all measured at baseline and women’s expression variables are measured at midline, we are predicting the effect of husbands’ preferences on sexual expression that is taking place one year after. This approach ensures a logical temporal order of predictor and outcome variables and minimizes potential endogeneity between husbands’ preferences and women’s actual expression.2

We include several independent variables in our multivariate analyses that capture women’s sexual expression at baseline, general couple discussion, resources available to women that may influence sexual expression, and couples’ backgrounds. We include baseline measures of whether women had ever expressed desire to have sex or desire not to have sex in each model, respectively, to account for the influence women’s experience with past sexual expression may have on future sexual expression.3 To capture general couple discussion, we include women’s reports of talking with their husbands about sex at baseline as a predictor variable, as husbands’ preferences may have less of an influence when discussion of sexual matters is poor, because wives may be unable to ascertain their husbands’ opinions (Mason and Smith 2000)(Mason & Smith 2000). We also include a measure of couples’ overall communication at baseline: a dichotomous variable capturing whether women reported ever openly disagreeing with husbands.

The resources available to women that may influence sexual communication include life stage, education and employment, sexual health, and spousal social dependence (Pande, Falle, Rathod, Edmeades, and Krishnan 2009)(Pande et al. 2009). Unless otherwise noted, all resource variables are measured in the 2005 baseline. Life stage measures include continuous measures of the age differential, in years, between husband and wife (husband – wife), marital duration, and number of living children. To measure education, we use a three-category variable capturing intra-couple educational differences (wife has higher education; couple has equal education; and husband has higher education). For employment, we include a dichotomous measure of whether women reported working before marriage. We include a two category variable indicating whether the woman felt prepared for her first sexual experience and a dichotomous measure of spousal social dependence: whether women identified their husbands as their primary source of social support (measured at midline). We hypothesise that women who depend primarily on their husbands may have fewer sources of outside support and thus are less likely to demonstrate sexual expression that may conflict with their husbands’ presumed wishes. Finally, we include a dichotomous measure of wives’ reports of whether husbands had any difficulty finding or keeping a job in the last six months at midline and an index variable capturing household assets at baseline.

Results And Analysis

On average, women in our sample were younger than their husbands by 5.31 years, had been married 4.33 years, and had 1.56 living children (Table 2). Most women had achieved equal education as their husbands, although 20% were more educated. Two-thirds had worked prior to marriage.

Table 2.

Key characteristics of study women (n=185); married women ages 16–25 in Bangalore, India, 2005–2006.

| Women (n=185) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | |

| Age difference with husband (years) | 5.31 | 0.220 |

| Marital Duration | 4.33 | 0.214 |

| Number of living children | 1.56 | 0.083 |

| N | Percent | |

| Education difference with husband | ||

| Wife more educated | 37 | 20.00 |

| Equal education | 118 | 63.78 |

| Husband more educated | 30 | 16.22 |

| Worked before marriage | 123 | 66.42 |

| Felt prepared for first sex | 20 | 10.81 |

| Husband primary source of social support – (midline) | 86 | 46.49 |

| Ever talked to husband about sex – wife’s report | 71 | 38.38 |

| Ever openly disagreed with husband – wife’s report | 123 | 66.49 |

| Husband had no difficulty finding or keeping a job (midline) | 36 | 19.46 |

Few women reported feeling they had enough information prior to the first time they had sex. When asked about their social networks at the midline, 46% cited their husbands as their primary source of social support. Thirty-eight percent of women reported ever discussing sex with their husbands at baseline, and two-thirds reported ever openly disagreeing with their husbands at baseline. Only 19% of women reported that their husbands had not had trouble finding or keeping a job in the last six months.

Women’s sexual expression and couple concurrence

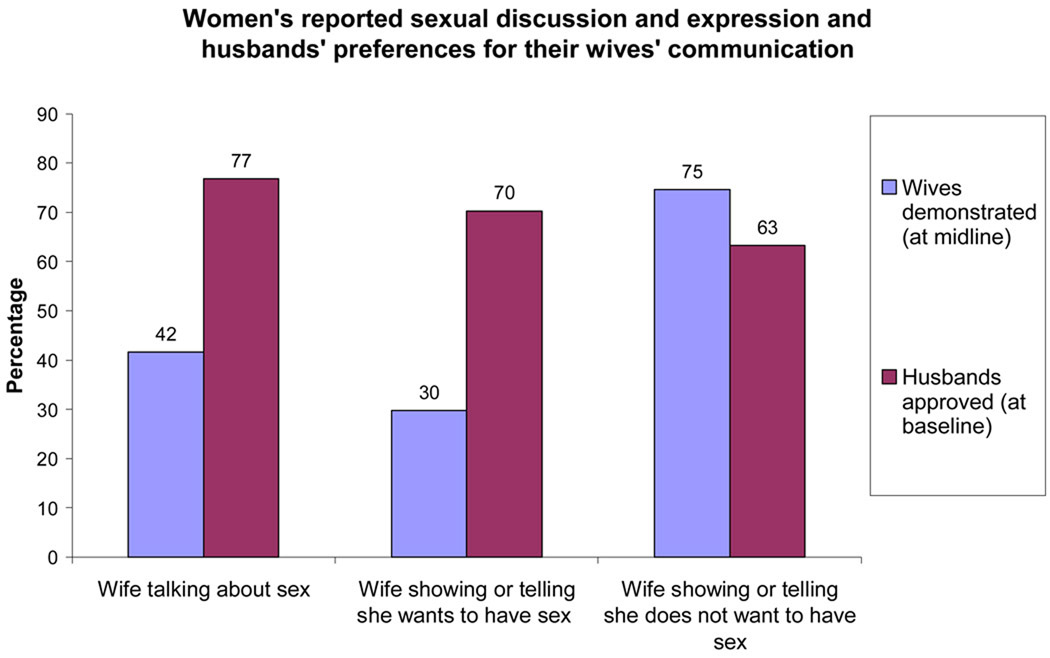

In low-income communities in India, women are often expected to provide sex to their husbands as part of their marital duty, and although studies find that many women do express sexual desire, experience of sexual violence within marriage routinely limits women’s enjoyment of sex (George 1998;Krishnan, Pande, Sanghamitra, Mathur, Subbaih, Roca, Measham, and Anuradha 2005;Maitra and Schensul 2002)(George 1998;Krishnan, Pande, Sanghamitra, Mathur, Subbaih, Roca, Measham, & Anuradha 2005;Maitra & Schensul 2002). Given this context, it is unsurprising that women and men reported widely varying patterns of sexual discussion and expression and approval of it. Figure 1 suggests that in our sample men were more open to sexual discussion and expression than women. Regarding talking about sex, 42% of women at midline reported talking with their husbands about sex in the last six months, compared to 77% of men who approved of discussing sex (at baseline). Similarly, a much larger proportion of husbands believed it was acceptable for their wives to show or tell when she wanted to have sex (70%) than the proportion of women who had expressed sexual desire (30%). In contrast, women were more likely to report telling or showing their husbands they did not want to have sex in the past six months (75%) than their husbands reporting this as acceptable behaviour (63%).

Figure 1.

Women’s reported sexual discussion and expression and husbands’ preferences regarding wives’ sexual discussion and expression; young married women aged 16–25 and their husbands in Bangalore, India, 2005–2006.

As the trends in husbands’ and wives’ agreement about sexual expression suggest, it appears that women in our sample were better able to express desire NOT to have sex than they were to express desire to have sex. Although a slightly lower percentage of husbands approved of this, in half of couples, wives reported telling their husbands they did not want sex and husbands felt it was reasonable for them to do so (Table 3). The majority of discordance occurred when the woman reported telling her husband she did not want to have sex and her husband did not approve of her doing so (25% of couples). This suggests that a noteworthy minority of men in the sample are supportive of increased sexual expression when this may lead to increased sexual access to their wives, and less so when this may mean decreased access.

Table 3.

Expressing desire not to have sex and desire to have sex among study women and men (n=185); married women ages 16–25 in Bangalore, India, 2005–2006.

| Respondents (n=185) | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | Percent | |

| Desire not to have sex | ||

| Converge | ||

| Wife expressed refusal and husband approved | 92 | 49.73 |

| Wife did not express refusal and husband did not approve | 22 | 11.89 |

| Diverge | ||

| Wife expressed refusal, husband did not approve | 46 | 24.86 |

| Wife did not express refusal, husband approved | 25 | 13.51 |

| Desire to have sex | ||

| Converge | ||

| Wife expressed desire and husband approved | 37 | 20.00 |

| Wife did not express desire and husband did not approve | 37 | 20.00 |

| Diverge | ||

| Wife expressed desire, husband did not approve | 18 | 9.73 |

| Wife did not express, husband approved | 93 | 50.27 |

Fewer women (30%) showed or told their husbands that they wanted to have sex, and a large divergence existed between husbands’ reported preferences and wives’ reported expression of sexual desire. This divergence was due almost entirely to women not engaging in sexual expression to the extent that their husbands reported preferring; in half of couples the husband reported approving of his wife showing or telling him that she wanted sex while the wife reported not having done so (Table 3). However, agreement between husbands’ preferences for and wives’ reported expression of sexual desire occurred in a sizeable minority of couples. In one in five couples in our sample, women reported expressing sexual desire while their husbands reported wanting them to do so. In another 20% of couples, women did not express sexual desire and husbands reported that they did not want them to do so.

These results suggest that avoiding or refusing sex may be more acceptable than seeking sex for women in this context, which supports findings from other studies that expressing sexual desire is difficult in conservative South Asian settings (Khan et al. 2002). Some explanation of why women did not express sexual desire can be found in women’s reported reasons for lack of expression.. The most commonly cited reason by women who had not shown or told their husbands that they wanted to have sex in the past six months (n=130) were that they do not like sex (79.2%), that there is “no need” to show or tell husbands (73.8%), and that they are too shy to do so (61.5%). Just over half of these women (56.9%) cited the inappropriateness for women to express desire as a reason (results not shown).

The reasons cited most commonly for not refusing sex suggest that it is not that most women could not do so because of social norms. Rather, many may have chosen not to refuse sex because of a mutual respect with their husbands. Nearly all women (93.5%) reported “liking their husbands a lot” as a reason not to rebuff husbands. The next most commonly cited reasons for not saying no to sex were that her husband does not say no when she expresses her desire (63.0%) and that she likes to have sex (60.9%). However, 51% of women who did not refuse sex with husbands reported that it was inappropriate for women to do so. Norms of what is and is not appropriate from women did appear to influence women’s sexual expression, but the ‘give and take’ relationship dynamic seemed to be more commonly felt in this small group of women who reported that they did not say no to sex with their husbands.

Multivariate results

We use multivariate regression to further explore the insights into how men’s preferences reflect and differ from women’s sexual expression that emerged from the descriptive analyses. Due to the characteristics of the sample, particularly the small number and potential selectivity of cases included, these results should be viewed as exploratory and are intended to bolster the descriptive findings. We restrict our discussion to those variables that directly relate to couple communication.

Our findings suggest that among this sample of couples, husbands’ preferences at baseline are an important influence on whether wives told or showed their husbands that they wanted to have sex (Model 1, Table 4) and that they did not want to have sex (Model 2, Table 4) one year later at midline. Women whose husbands felt it was acceptable for wives to demonstrate one form were significantly more likely to report having told or shown their husband they wanted to have sex in the previous 6 months than those whose husbands did not (beta=2.8, p=0.03). Similarly, we saw a trend that women whose husbands approved of them showing two or three forms of sexual discussion or expression were also more likely to have shown or said they wanted to have sex (beta=2.4, p=0.06 and beta=2.0, p=0.10, respectively). The magnitude of the effect was largest for women with husbands who approved of only one form of sexual expression from wives, suggesting that the threshold in encouraging women to express sexual desire is any indication from their husband that this is acceptable.

Table 4.

Significant determinants of women’s sexual expression; married women ages 16–25 in Bangalore, India, 2005–2006.£

| VARIABLES (reference in parentheses) | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Told husband want to have sex (at midline) |

Told husband do not want to have sex (at midline) |

|||

| Coef. | p-value | Coef. | p-value | |

| Husbands’ perceptions (at baseline) | ||||

| Husbands feel it is ok if wives demonstrate: | ||||

| 1 form of sexual discussion and expression (0 forms) | 2.799** | 0.027 | 1.578** | 0.042 |

| 2 forms of sexual discussion and expression (0 forms) | 2.382* | 0.055 | 1.190* | 0.07 |

| 3 forms of sexual discussion and expression (0 forms) | 2.024* | 0.097 | 1.421** | 0.038 |

| Women’s sexual expression at baseline | ||||

| Told or showed husband want to have sex (did not) | 1.687*** | <0.001 | ||

| Told or showed husband did not want to have sex (did not) | 1.882*** | <0.001 | ||

| General couple discussion (at baseline) | ||||

| Ever talked to husband about sex – wife’s report (has not talked) | 0.715* | 0.080 | 0.481 | 0.252 |

| Resources (at baseline) | ||||

| Number of living children | 0.055 | 0.798 | 0.515** | 0.027 |

| Household asset score – baseline | −0.112 | 0.580 | 0.403* | 0.069 |

| Constant | −5.077*** | <0.001 | −1.144 | 0.264 |

| Observations | 185 | 185 | ||

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.1870 | 0.1842 | ||

p values in parentheses

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

We report only the statistically significant (p<0.10) variables. The models also control for husband-wife age difference; marital duration; education difference; women’s report of ever openly disagreeing with husbands, preparation for first sex, work prior to marriage, perception that husband is primary source of social support; and husband has a stable job at midline.

Women whose husbands approved of sexual discussion and expression were also more likely to show when they did not want to have sex (Model 2, Table 4). The magnitude of the association is highest when men are open to one form of women’s sexual discussion and expression (beta=1.6, p=0.04), suggesting again that any indication from husbands that sexual expression is acceptable encourages women to express desire not to have sex. These findings are consistent with our descriptive results, with greater couple convergence on whether wives can or should express a desire to not have sex, and more divergence on wives demonstrating a desire to have sex.

In addition to the association between husbands’ preferences and women’s sexual expression, women’s own experience with sexual expression at baseline had a significant effect on their sexual expression at midline. Women who had ever shown or told their husbands they wanted to have sex at baseline were significantly more likely to have done so in the 6 months preceding midline (beta=1.7, p<0.001, Model 1). Similarly, women who had ever said no to sex at baseline were significantly more likely to have done so at midline (beta=1.9, p<0.001, Model 2). These results suggest that while husbands’ preferences play an important role in determining women’s sexual expression, so too does women’s own experience with showing sexual desire. Women’s own sexual expression may increase the likelihood that husbands approve of their wives’ discussion of sex, which may encourage women’s communication about sex.

When women reported talking with their husbands about sex at baseline, they trended towards being more likely to express desire to have sex at midline (beta=0.7, p=0.08, Model 1), although no more likely to express desire not to have sex (beta=0.4, p=0.252, Model 2). Open disagreement with husbands on any issue was not a significant determinant of either form of sexual expression. These results suggest that talking about sex is a key component of demonstrating sexual desire, but general disagreement is not particularly relevant to disagreements about sex specifically.

Discussion

Among this sample of women and their husbands in the slums of Bangalore, significant divergence of opinion and action characterised husbands’ and wives’ sexual expression. A minority of women reported talking about sex or expressing sexual desire, although a large majority had at least attempted to refuse sex with their husbands. While women’s sexual expression appeared to be significantly constrained by norms of women’s sexual submissiveness and/or lack of interest in sex, we found that husbands were more comfortable with their wife expressing sexual preferences than norms might suggest. Many husbands reported that they felt it was acceptable for their wives to talk about sex, and that they would like wives to show sexual desire. Furthermore, the multivariate results suggest that an increased openness to sexual discussion among husbands may encourage wives to express their sexual desire and to refuse sex when it is unwanted.

Expressing sexual desire is limited among couples

In this population of couples, women appeared better able to disagree with their husbands about having sex than to express sexual desire themselves. This finding corroborates previous research; the 2005 National Family Health Survey (NFHS) found that in Karnataka only 16.4% of women and 11.9% of men believed women were not justified in refusing sex to their husbands (International Institute for Population Sciences 2007). Our findings, as well as those from the recent NFHS, allude to the importance of women’s creative communication to determine the timing of sexual activity (Blanc 2001;Khan, Townsend, and D'Costa 2002).

The majority of women in our sample did not express sexual desire to husbands, which seems to conform to traditional ideals of the ‘good’ wife who is uninterested in sex and sexually submissive (Joshi, Dhapola, Kurian, and Pelto 2001). However, this majority was not overwhelming; 30% of women reported that they did tell or show their husband they wanted to have sex. This finding adds to the growing evidence that a stereotype of the Indian wife as uniformly passive and sexually subservient fails to capture the nuance of women’s experiences within the narrow range of socially acceptable behaviors (Joshi, Dhapola, Kurian, and Pelto 2001;Pande, Falle, Rathod, Edmeades, and Krishnan 2009), and is encouraging. As Indian women increasingly communicate with their husbands about their sexual desires, they will better placed to define the timing and nature of their sexual experiences and negotiate strategies to prevent unintended pregnancy and STI infection (George 2002;Joshi, Dhapola, Kurian, and Pelto 2001;Maitra and Schensul 2002).

Couple discussion may be an asset for women to meet their sexual desires

Husbands in our sample reported greater approval for women’s expression of sexual desire than women themselves demonstrated, while women’s sexual refusals and their husbands’ approval of them were quite common. They also proved more open to their wives’ sexual expression than is commonly thought to be the case in India. However, husbands appeared more receptive of communication that may increase sexual access to their wives and less receptive to empowering their wives to refuse sex, a situation that may not improve women’s overall sexual empowerment. Alternatively, men’s preferences for sexually expressive wives may become a resource for women who enjoy sex to leverage to achieve their personal, sexual and reproductive intentions in spite of a disempowering normative context.

However, our analyses also suggest that leveraging husbands’ attitudes is likely to be dependant on women improving the quality and quantity of discussion about sex with husbands. Couples’ general discussion of sex plays an important role in improving women’s expression of their sexual desires among this sample of women and in other analyses (Jejeebhoy and Bott 2005;Koenig, Jejeebhoy, Cleland, and Ganatra 2008). Although gender norms in India cast women as sexually submissive, among our study population women may be able to express sexual desire and achieve mutually consensual sexuality if couples talk more openly about sex.

Limitations

This study offers suggestive findings about concordance in couples attitudes’ and behaviours regarding sexual expression in Bangalore slums. However, the findings should be interpreted carefully, as the data are not representative of the broader population and the process through which husbands are included in the study may have resulted in a less conservative group than the norm. Husbands participated in our study after their wives gave the study team permission to contact them, potentially excluding couples with particularly poor relationships. Although we find little evidence based on women’s reports to suggest that husbands and wives who completed the baseline survey have more intimate marital relationships, it is possible that the women included in the study, or their husbands, differ in unmeasured ways from couples who were not included. It is possible that the study failed to recruit particularly disempowered women, or that the husbands who participated are particularly “progressive” in their view of sexual interactions, and thus not reflective of these two slum communities as wholes. This is partially supported by observations that women in our sample were more likely to have indicated desire to not have sex with their husbands in the preceding six months. More direct measures of relationship quality and intra-partner communication would perhaps have found greater difference between the two groups and should be included in future studies, as should recruitment methods focused on the couple dyad (rather than one partner). However, it is noteworthy that even if the sample is less conservative than the norm, significant gender differences in terms of sexual expression exist and women continue to exhibit a general lack of sexual agency, suggesting that these gender differences may be even more marked in the broader population.

Social desirability bias may also explain some of men’s comparatively more open attitudes regarding their wives’ sexual expression. If men are in fact less open to sexual communication than they report, then men’s preferences are likely to be a less important influence on women’s sexual expression than our results and discussion suggest. However, we find that men’s preferences are associated with women’s sexual expression in the hypothesised way, suggesting that men are demonstrating approval for their wives’ sexual expression and that women themselves perceive this approval. Furthermore, previous research shows that in South Asia and other settings, husbands seem to have a comparatively more liberal view of women’s autonomy than do wives (Becker, Fonseca-Becker, and Schenck-Yglesias 2006;Jejeebhoy 2002).

Finally, the dynamics of sexual communication and negotiation are more nuanced than the measures used in this paper. In this context, couple communication around sex is determined to a significant extent by the broader social and cultural environment. As a result, women are likely to rely on relaying their sexual desires in very subtle ways. An ideal study would incorporate a more nuanced approach to measuring couple interaction dynamics in this context, including both quantitative and qualitative analyses that engages both elements of the spousal dyad. However, attempting to measure these complex social processes quantitatively is an important first step to further research in this area, despite the inherent limitations to this approach.

Directions for future research

This study points to some preliminary drivers of women’s sexual expression in the Bangalore slums, and identifies areas for future research to elucidate more complete understanding of strategies to improve women’s sexual agency. Additional studies could investigate the ways in which husbands and wives agree and disagree on acceptable sexual communication and how husbands’ attitudes influence wives’ communication behaviours. Further research with a larger and more representative sample would add understanding to if and how this relationship functions outside of our study population. Moreover, future investigation should focus on developing more nuanced measures of both men and women’s preferences and communication topics within the sexual arena, as certain topics may be more acceptable than others, a difference potentially obscured in the broader measures employed in this paper.

Next, our results suggest that husbands may be more receptive to their wives’ attempts to communicate their sexual needs than is commonly thought, but many women are either unaware of this receptiveness or unwilling to express their needs for cultural reasons. These findings suggest that in this sample of couples, programmes targeted at changing men’s attitudes about wives’ sexual expression or at boosting women’s sexual expression in absence of husbands may not be as effective as an intervention that works with both partners to increase overall discussion. While programmes targeting men have a place in changing men’s attitudes and behaviours, engendering a more communicative marriage may be necessary before husbands’ attitudes can be translated into behaviour among wives. Given the relatively open attitudes expressed by husbands in this study, improved discussion may allow women to exert more influence over their sexual expression, perhaps with support of their husbands.

Conclusions

Although exploratory and preliminary in nature, our findings suggest men do play a role in determining women’s sexual expression, and therefore their overall capacity to negotiate the terms of their sexuality. Our results suggest that while couple discussion is limited, men in our study seem to want more engagement from their wives, not less. When couples communicate more frequently and effectively about sex, both verbally and non-verbally, husbands’ preferences may become a resource for women to draw upon as they exercise sexual agency. In this limited sample, husbands do not appear to fit the stereotype of men looking for complete sexual control over their wives (Santhya and Jejeebhoy 2005). While further research is required to establish whether this is more broadly true, the results do suggest that it may be time to begin a new body of research to reassess empirically the paradigm of husbands as arbiters of women’s sexuality.

Acknowledgements

The authors would to acknowledge the contributions of the Samata study team for their data collection efforts. We thank Rohini Pande and Reshma Trasi for their invaluable comments on earlier versions of this manuscript, and Laura Brady for her research assistance. This research was supported by grant R01HD041731 to Suneeta Krishnan from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NICHD.

Footnotes

The most common reasons for women refusing consent were: lack of time on their husband’s part (174 women), feeling that he would not participate (154 women), and feeling he would be angry with her for answering the questions or participating (72 women). While there may be important differences between these groups in terms of sexual communication, the available data do not allow us to explore this detail.

The potential endogeneity results because husbands’ receptiveness to women’s expression of sexual desires may encourage that expression, which may in turn change husband’s preferences.

Women’s baseline and midline responses to questions about sexual expression are not highly correlated (rho<0.35 for both measures).

References

- Allendorf K. Couples' Reports of Women's Autonomy and Health-Care Use in Nepal. Studies in Family Planning. 2007;38(1):35–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2007.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankole A. Desired Fertility and Fertility Behaviour among the Yoruba of Nigeria: A Study of Couple Preferences and Subsequent Fertility. Population Studies. 1995;49(2):317–328. [Google Scholar]

- Becker S. Couples and Reproductive Health: A Review of Couple Studies. Studies in Family Planning. 1996;27(6):291–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker S, Fonseca-Becker F, Schenck-Yglesia C. Husbands' and Wives' Reports of Women's Decision-Making Power in Western Guatemala and Their Effects on Preventive Health Behaviors. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62(9):2313–2326. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc AK. The Effect of Power in Sexual Relationships on Sexual and Reproductive Health: An Examination of the Evidence. Studies in Family Planning. 2001;32(3):189–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derose LFD, Ezeh AC. Men's Influence on the Onset and Progress of Fertility Decline in Ghana, 1988–98. Population Studies. 2005;59(2):197–210. doi: 10.1080/00324720500099496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George A. Differential Perspectives of Men and Women in Mumbai, India on Sexual Relations and Negotiations Within Marriage. Reproductive Health Matters. 1998;6(12):87–96. [Google Scholar]

- George A. Embodying Identity Through Heterosexual Sexuality - Newly Married Adolescent Women in India. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2002;4(2):207–222. [Google Scholar]

- Gipson JD, Hindin MJ. 'Marriage Means Having Children and Forming Your Family, So What is the Need of Discussion?' Communication and Negotiation of Childbearing Preferences Among Bangladeshi Couples. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2007 March–April;9(2):185–198. doi: 10.1080/13691050601065933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), India 2005–06. Mumbai, India: International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS); Macro International; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jejeebhoy SJ. Convergence and Divergence in Spouses' Perspectives on Women's Autonomy in Rural India. Studies in Family Planning. 2002;33(4):299–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2002.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jejeebhoy SJ, Bott S. Non-Consensual Sexual Experiences of Young People in Developing Countries. In: Jejeebhoy SJ, Shah I, Thapa S, editors. Sex Without Consent: Young People in Developing Countries. New York, NY: Zed Books; 2005. pp. 3–45. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A, Dhapola M, Kurian E, Pelto PJ. Experiences and Perceptions of Marital Sexual Relationships among Rural Women in Gujarat, India. Asia-Pacific Population Journal. 2001;16(2):177–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer N. Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women's Empowerment. Development and Change. 1999;30(3):435–464. [Google Scholar]

- Khan ME, Townsend JW, D'Costa S. Behind Closed Doors: A Qualitative Study of Sexual Behaviour of Married Women in Bangladesh. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2002;4(2):237–256. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Jejeebhoy SJ, Cleland JC, Ganatra B. Reproductive Health in India: New Evidence. Jaipur, India; New Delhi, India: Rawat Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan S. Gender, Caste, and Economic Inequalities and Marital Violence in Rural South India. Health Care for Women International. 2005;26(1):87–99. doi: 10.1080/07399330490493368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan S, Pande RP, Sanghamitra I, Mathur S, Subbaih K, Roca E, Measham D, Anuradha R. Marriage and Motherhood: Influences on Urban Indian Women's Power in Sexual Relationships. Paper presented at International Union for the Scientific Study in Population; July 18 2005; Tours, France. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mahal A, Yazbeck AS, Peters DH, Ramana GNV. The Poor and Health Service Use in India. Washington, DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Maitra S, Schensul SL. Reflecting Diversity and Complexity in Marital Sexual Relationships in a Low-Income Community in Mumbai. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2002;4(2):133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Mason KO, Smith HL. Husbands' Versus Wives' Fertility Goals and Use of Contraception: The Influence of Gender Context in Five Asian Countries. Demography. 2000;37(3):299–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair J. The Promise of the Metropolis: Bangalore's Twentieth Century. New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pande RP, Falle TY, Rathod S, Edmeades J, Krishnan S. Agency in Sexuality and Reproductive Health among Young Married Women in Bangalore, India. Paper presented at Annual Meetings of the Population Association of America; April 29 2009; Detroit Michigan. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rocca CH, Rathod S, Falle T, Pande RP, Krishnan S. Challenging Assumptions About Women's Empowerment: Social and Economic Resources and Domestic Violence among Young Married Women in Urban South India. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;38(2):557–585. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhya KG, Jejeebhoy SJ. Young Women's Experiences of Forced Sex Within Marriage: Evidence from India. In: Jejeebhoy SJ, Shah I, Thapa S, editors. Sex Without Consent: Young People in Developing Countries. New York, NY: Zed Books; 2005. pp. 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sathar ZA, Kazi S. Survey on the Status of Women and Fertility. Islamabad, Pakistan: Institute of Development Economics; 1997. [Google Scholar]