Abstract

Aqueous humor production is a metabolically active process sustained by the delivery of oxygen and nutrients and removal of metabolic waste by the ciliary circulation. This article describes our investigations into the relationship between ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor production. The results presented indicate that there is a dynamic relationship between ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor production, with production being blood flow independent above a critical level of perfusion, and blood flow dependent below it. The results also show that the plateau portion of the relationship shifts up or down depending on the level of secretory stimulation or inhibition, and that oxygen is one critical factor provided by ciliary blood flow. Also presented is a theoretical model of ocular hydrodynamics incorporating these new findings.

Keywords: Ciliary blood flow, Aqueous humor production, Aqueous humor dynamics, Intraocular pressure

1. Introduction

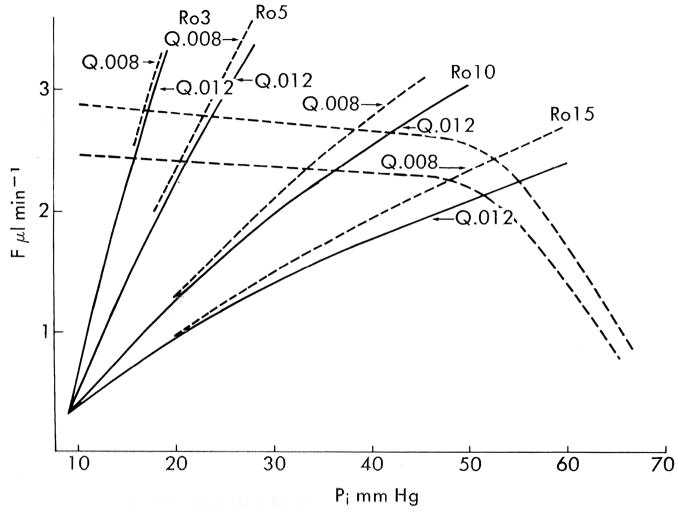

Moses published one of the most iconic yet enigmatic graphs in the field of aqueous humor dynamics in the 7th edition of Adler’s Physiology of the Eye (Fig 1). (Moses, 1981) The graph is iconic because it concisely illustrates the fundamental concept that steady state intraocular pressure occurs when aqueous humor inflow and outflow are equal. The graph is enigmatic because data for the aqueous humor inflow curves were scant at the time, and the “equation unknown”. Even more enigmatic, Moses was silent about the graph showing two inflow curves rather than one and mum about what might cause multiple curves to occur. Regarding the shape of the inflow curves, he said only “the rate of aqueous humor formation decreases slightly as intraocular pressure increases until the region of ciliary artery blood pressure is approached, when it decreases rapidly.” It was known at the time that ciliary blood flow is autoregulated (Bill, 1981) and that aqueous humor production is a metabolically active process, (Sears, 1981) and so it is plausible he hypothesized that production is blood flow dependent and so declines when the autoregulatory range is exceeded. It was also known that aqueous humor production can be stimulated or inhibited pharmacologically, and so multiple inflow curves would also perhaps have seemed reasonable. We will never know his rationale for the inflow curves, but recent studies on the relationship between ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor production support the predictions of Moses’ iconic graph.

Figure 1.

Moses’ hypothetical graph showing the effect of IOP (Pi) on aqueous humor inflow and outflow; steady state IOP occurs where the curves intersect and inflow equals outflow. The slopes of the curves for total outflow (trabecular plus a fixed uveoscleral flow of 0.3 μl/min) rising up and to the right vary with outflow resistance (Ro) as modified by the obstruction coefficient (Q). The episcleral venous pressure (Pe) is assumed to be 9 mmHg, which defines the origin of the outflow curves, since trabecular outflow ceases when Pi = Pe. Aqueous humor inflow is represented by the dashed lines with small negative slopes until IOP exceeds 50 mmHg, whereupon the slopes become more negative, extrapolating to an x-intercept (i.e., inflow = zero) when IOP equals the assumed ciliary arterial pressure of 70 mmHg. (Moses, 1981)

2. Anatomical considerations

2.1 Gross anatomy and vasculature

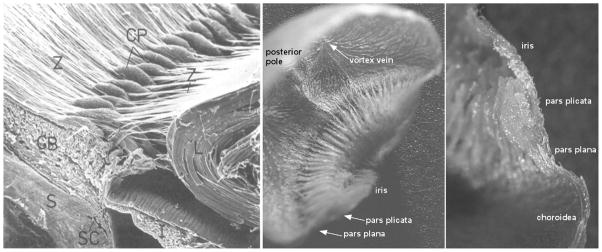

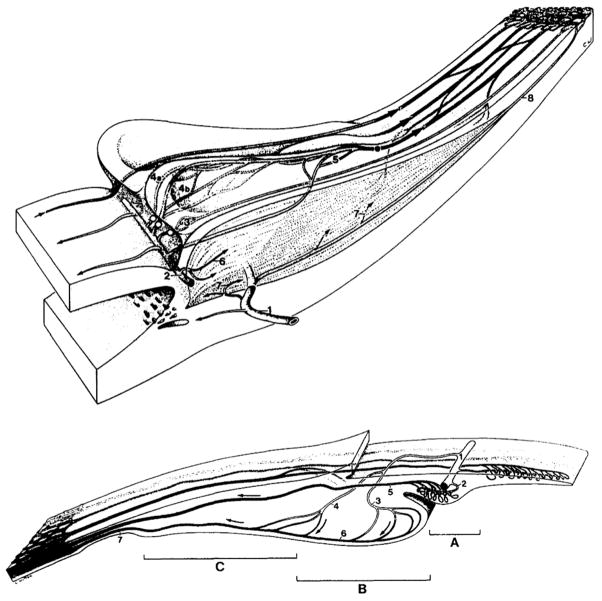

Aqueous humor is produced in the ciliary processes, which form a ring of leaf-like projections into the posterior chamber under the iris root and limbus (Fig 2). (Gabelt et al., 2006) The arterial supply to the ciliary processes is derived from the major arterial circle of the iris fed primarily by the long posterior ciliary arteries (Fig 3). (Morrison et al., 1987) The ciliary circulation typically divides into three zones. (Funk and Rohen, 1990; Lutjen-Drecoll and Rohen, 1994) The first zone is at the anterior base of the processes and consists of arterioles and capillaries that drain into a venular system separate from the other zones. This zone is the boundary between the non-fenestrated capillaries of the iris and the fenestrated capillaries of the ciliary processes. The fenestrations in the ciliary capillaries permit passage of protein into the stroma, which establishes an oncotic pressure that is important in aqueous humor production. (Bill, 1968a, b) The second zone also originates at the anterior base but extends more anteriorly into the processes and then drains into marginal venules running along the inner edge of the processes that coalesce into an efferent venous segment that travels posteriorly into the pars plana and the vortex veins. The third zone supplies the posterior portion of the major processes and the minor processes if present. The morphology of ciliary processes and their attendant vascularization varies among mammalian species (Fig 3), though all share an anterior arterial source and posterior venous drainage. (Rohen and Funk, 1994)

Figure 2.

Ciliary anatomy. Left: scanning electron micrograph of anterior eye of cynomolgus monkey showing ciliary processes. (Rohen, 1979, with permission of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology) Middle: view of ciliary processes from the posterior pole of a bisected vascular cast of a rabbit eye. Right: vascular cast of a single ciliary process in profile. (Reitsamer and Kiel, 2002a) (Z: zonules, CP: ciliary process, CB: ciliary body, L: lens, S: sclera, SC: Schlemm’s canal, I: iris)

Figure 3.

Schematic illustrations of human (top) and rabbit (bottom) ciliary circulations. Top: 1= perforating branch of anterior ciliary artery, 2= major arterial circle of the iris, 3=capillaries of first vascular territory, 4a= thoroughfare channel, 4b= capillary network, 5=capillaries of posterior major processes, 6= circular muscle vessels, 7= longitudinal muscle vessels, 8=recurrent choroidal artery. Bottom: A=iridial processes, B= major processes, C=minor processes, 1=major arterial circle of the iris, 2=terminal arterioles of iridial processes, 3=terminal arterioles of major processes, 4=terminal arterioles of minor processes, 5=venule draining iridial processes, 6=marginal vein of major processes, 7=efferent veins draining into pars plana venules. (Rohen and Funk, 1994)

The ciliary body’s small size, inaccessible location and complex vascular organization make it difficult to study ciliary hemodynamics. Nonetheless, some general assumptions are possible for baseline perfusion pressure and ciliary blood flow. Direct measurements of ciliary arterial pressure have not been made, but a reasonable estimate for arterial pressure just outside the eye is 67 mmHg for humans in an upright position with a normal brachial arterial pressure of 100 mmHg. (Bill, 1984) The intraocular veins behave as Starling resistors such that the venous pressure inside the eye is set by the IOP. (Fry et al., 1980; Moses, 1963; Patterson and Starling, 1914) In animals, the choroidal venous pressure is 1–2 mmHg higher than the IOP and ciliary venous pressure should behave similarly. (Maepea, 1992) Capillary pressure is similarly IOP-dependent, and approximately 8 mmHg higher than IOP in the rabbit choriocapillaris. (Maepea, 1992) Assuming that ciliary hemodynamics are similar, the ciliary capillary and venous pressures at a normal IOP of 15 mmHg should be approximately 23 and 17 mmHg, respectively. (Kiel, 1998) Baseline values for ciliary blood flow are scant. The plasma clearance of ascorbate is high in the ciliary processes, and a typical aqueous-to-plasma ascorbate ratio of 26.5 and rate of aqueous humor production at 2.75 μl/min in humans give a rough estimate of ciliary plasma flow at 73 μl/min, or a blood flow of 133 μl/min assuming a normal hematocrit. (Linner, 1950, 1952) Microsphere measurements in monkeys indicate a slightly lower ciliary blood flow at 89 μl/min. (Alm and Bill, 1973)

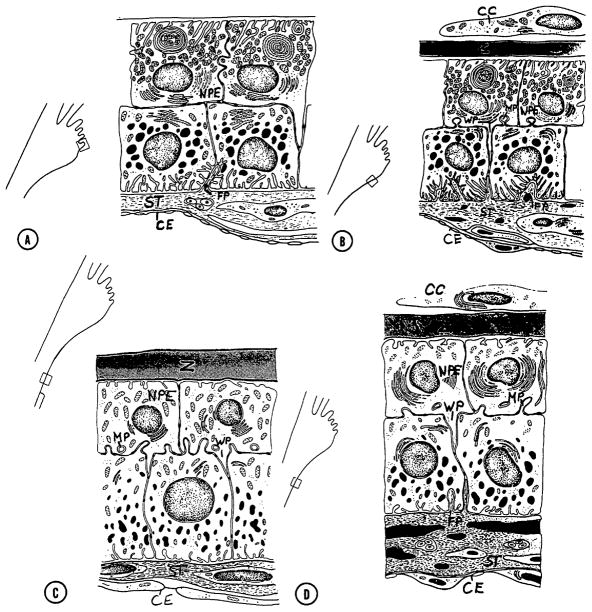

2.2 Epithelial bilayer

The surface of the ciliary processes is covered with an epithelial bilayer overlaying the core of stroma and blood vessels; a layer of pigmented epithelial cells facing the stroma and a layer of non-pigmented epithelial cells facing the posterior chamber. The structure of the epithelial bilayer varies along the length of the processes (Fig 4) with the anterior region having morphological characteristics consistent with secretion. (Hara et al., 1977)

Figure 4.

Schematic of variation in primate ciliary epithelial bilayer fine structure from anterior process to posterior base. CC: covering cells, CE: capillary endothelium, FP: fingerlike projections, MP: mushroomlike process, NPE: nonpigment epithelium, ST: stromal layer, WP: wedgelike process, Z: zonular fibers. (Hara et al., 1977, with permission of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology)

3. Stages of aqueous humor formation

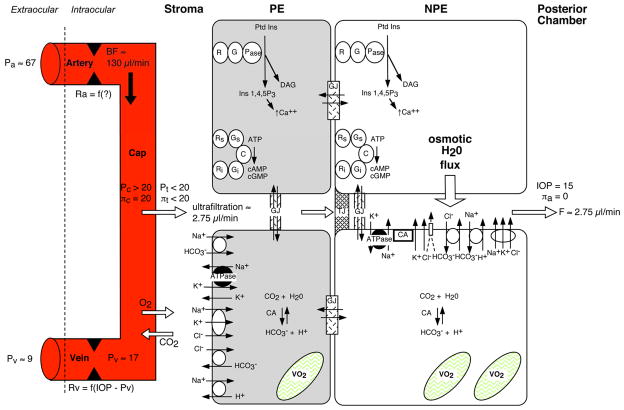

Figure 5 shows a schematic overview of aqueous humor production. (Kiel, 1998) Aqueous humor is formed in three stages: 1) convective delivery of water, ions, proteins and metabolic fuel by the ciliary circulation, 2) ultrafiltration and diffusion from the capillaries into the stroma driven by the oncotic pressure, hydrostatic pressure, and concentration gradients, and 3) ionic transport into the basolateral spaces between the nonpigmented epithelial cells followed by water movement down the resultant osmotic gradient into the posterior chamber. Due to the blood-aqueous barrier, the relative lack of protein in aqueous humor establishes a Starling equilibrium that opposes passive fluid movement across the epithelial bilayer, and so aqueous humor production is considered an active process requiring the expenditure of metabolic energy.

Figure 5.

Overview of aqueous humor formation. (Pa: extraocular arterial pressure; Ra: ciliary arterial resistance; BF: ciliary blood flow; Pc: ciliary capillary pressure; πc: capillary plasma oncotic pressure; Pt: stromal tissue hydrostatic pressure; πt: stromal tissue oncotic pressure; Pv: ciliary venous pressure; Rv: ciliary venous resistance; VO2: mitochondrial oxygen consumption; πa: aqueous humor oncotic pressure; F: aqueous humor flow; Ptd Ins: phosphatydalinositol; Ins 1;4;5 P3: inositol trisphosphate (2nd messenger for Ca++ release); DAG: diacylglycerol (2nd messenger for protein kinase C activation); Pase: phosphoinositidase; G: G protein complex; R: receptor; C: adenylate cyclase; Gs: stimulatory G protein complex; Gi: inhibitory G protein complex; Rs: stimulatory receptor; Ri: inhibitory receptor; ; GJ: gap junction; TJ: tight junction; ATPase: Na/K ATPase; open circles with arrows: transporters/cotransporters/antiporters; arrows: movement via ionic channels or diffusion) (Kiel, 1998; Kiel and Reitsamer, 2010)

The presence of various receptors and second messenger systems in the ciliary epithelia, the ability of drugs to inhibit or stimulate aqueous humor production, and the diurnal variation in aqueous humor production all suggest that the rate of aqueous humor production is influenced by the neurohumoral milieu of the ciliary processes.

4. Methodology

The results described below are based on 305 experiments conducted over the last decade. Some of the results are published and some not, so a brief description of the methods is warranted. All experiments were performed in New Zealand albino rabbits (1.8 – 2.5 kg, either sex) anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (30 mg/kg, i.v., supplemented as needed), and paralyzed with gallamine triethiodide (1mg/kg) to eliminate eye movement. The animals were intubated through a tracheotomy and respired with room air to maintain expired PCO2 at ≈40 mmHg and a heating pad was used to maintain normal body temperature (38–39°C). All intravenous injections were given via cannulated marginal ear veins.

A catheter inserted into the right ear artery and connected to a pressure transducer positioned at the same height above the heart as the eye was used to obtain an estimate of ocular arterial pressure. (Kiel and van Heuven, 1995) In some animals, hydraulic occluders were placed around the thoracic descending aorta and the inferior vena cava through a right thoracotomy to mechanically control mean arterial pressure (MAP). (Kiel and Shepherd, 1992) After the initial surgical preparation, the animals were mounted in a stereotaxic head holder. A transit-time ultrasound flow probe (Transonic Systems, 2PSB, Ithaca, NY) was placed on the right carotid artery and connected to a flowmeter (Transonic Systems, TS420, Ithaca, NY) to obtain an index of overall cerebral blood flow. The pulsatile carotid blood flow (BFcar) signal was used to trigger a digital cardiotachometer (ADInstruments PowerLab Chart v5.3, Colorado Springs, CO) to measure heart rate (HR). The right orbital venous sinus was cannulated with a 23 gauge needle inserted through the posterior supraorbital foramen to measure orbital venous pressure (OVP) with a second pressure transducer. (Reitsamer and Kiel, 2002b) The right eye was cannulated with a 23 gauge needle inserted into the vitreous cavity through the pars plana to measure the intraocular pressure (IOP) with a third pressure transducer. To avoid the rabbit ocular trauma response and release of prostaglandins, the right eye was anesthetized topically with lidocaine before the cannulation and care was taken not to disturb the cornea and anterior chamber. (Camras and Bito, 1980; Neufeld et al., 1972; Sears, 1960)

4.1 Aqueous humor flow measurement

As an index of aqueous humor production, aqueous humor flow (aqFlow) through the anterior chamber was measured by fluorophotometry (FM-2, OcuMetrics, Mountain View, CA). (Jones and Maurice, 1966) Each animal received 4–5 drops of fluorescein (2.5 mg/ml, Flurox, Ocusoft, Richmond, TX) at ≈8:00 AM on the day of the experiment. Two hours later, the animals were anesthetized, the treated eye irrigated with saline to remove excess fluorescein, and then the animal preparation described above was performed. Once the animals were mounted in the stereotaxic instrument and stable (3 – 3.5 hrs post fluorescein application), triplicate fluorophotometric scans were performed at 15 min intervals to measure the changes in corneal and anterior chamber fluorescein concentrations over time. (Kiel et al., 2001) Aqueous humor flow was calculated based on Brubaker’s method after applying the focal diamond correction to the raw corneal fluorescein concentration values. (Brubaker, 1991; Topper et al., 1984)

4.2 Ciliary blood flow measurement

Laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF) was used to measure ciliary blood flow (BFcil). (Shepherd and Öberg, 1990) LDF provides 3 indices of perfusion derived from the frequency spectra collected from tissue illuminated with laser light: the number of moving blood cells, their mean velocity, and the flux (the product of the velocity and number of moving blood cells). The flux correlates linearly with independent measures of blood flow in a variety of tissues. The laser Doppler flowmeters (PF4000 and PF5000, Perimed, Stockholm, Sweden) used in this study employ an infrared laser diode (780 nm, 1 mW) coupled to a fiber optic probe (PF403, 0.25 mm fiber separation, Perimed, Stockholm, Sweden). The flowmeter was calibrated so that the flux registered 250 perfusion units (P.U.) when the probe was placed in a suspension of latex particles at 22°C, and zero P.U. when placed against a plastic disk. The absence of a zero offset was confirmed at the end of each experiment when the animal was euthanized.

Ciliary blood flow was measured transclerally by placing the LDF probe on the scleral surface over the ciliary body (posterior to the limbus and anterior to the low blood flow reading at the pars plana) using a phonograph tonearm to hold the probe at the same location with the same force throughout the experiment. For the wavelength (780 nm) and fiber separation (0.25 mm) used in this study, the volume of tissue sampled by the flowmeter is approximately 1 mm3 which is sufficient to measure perfusion in the ciliary body through the overlying relatively avascular sclera. (Kiel et al., 2001)

4.3 Oxygen measurements

In some experiments, the partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) was measured in the posterior chamber next to the ciliary processes with single-barrel oxygen sensitive microelectrodes. (Linsenmeier and Yancey, 1987) (Reitsamer et al., 2006) In other experiments, arterial PO2 was measured with a ruthenium-tipped fiber-optic advanced to the distal aorta through the left femoral artery (Ocean Optics FOXY, Dunedin, FL). In some animals, a pulse oximeter with the probe placed on the oral mucosa was used to measure the percent saturation of hemoglobin with oxygen (%Sat).

4.4 Protocols

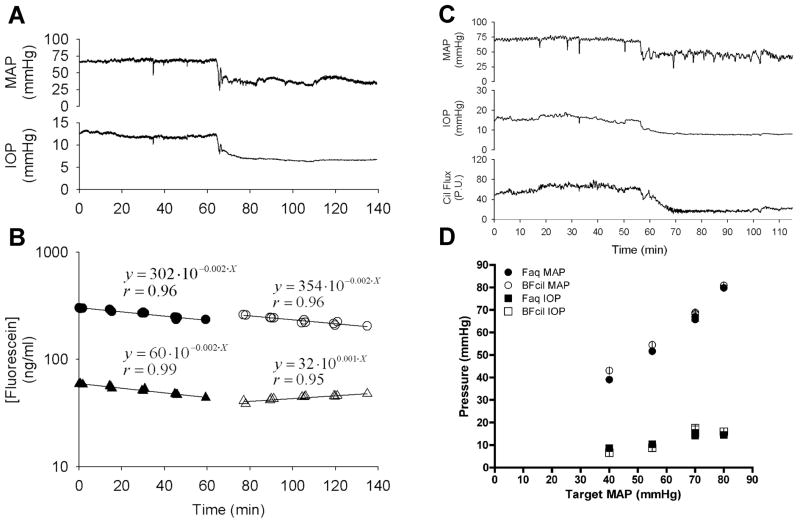

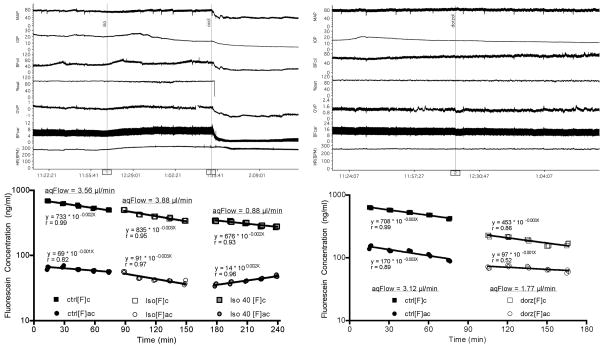

The goal of the initial studies was to study the relationship between ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor production. Ideally, this requires varying and measuring ciliary blood flow over a wide range while simultaneously measuring aqueous humor production. To vary ciliary blood flow, we chose mechanical rather than pharmacologic manipulation of systemic blood pressure to avoid confounding drug effects on aqueous humor production. In the early experiments, we had only the large FM-2 Fluorotron Master Fluorophotometer to measure aqueous humor flow, which precluded consistent placement of the LDF fiber optic probe to measure ciliary blood flow. Consequently, separate groups of animals were used to study aqueous humor flow and ciliary blood flow (Fig 6). For more recent studies, this problem was overcome by obtaining the smaller FM-2 Fluorotron Master Fluorophotometer Laboratory Animal Edition so that simultaneous measurements were achieved. (Fig 7). However, an insurmountable problem is that reliable aqueous humor flow calculations require measurements of fluorescein clearance for a minimum of 60 min, but our rabbit model remains stable for only 4–5 hours, so all target MAPs can not be studied in each animal. Thus, separate groups were used for each target pressure, with each group undergoing a 60–90 min period of baseline measurements (MAP at ≈70 mmHg) followed by 60–180 min of measurements at one target pressure, i.e., 40, 55, or 80 mmHg, sometimes with a superimposed drug intervention (e.g. isoproterenol infusion in Fig 7 left panel). More straightforward studies involved 60–90 min of baseline measurements followed by a drug intervention or inspired gas challenge (e.g. topical dorzolamide in Fig 7 right panel). A significant effort was made to ensure that the measurement conditions were as similar as possible for all groups (e.g. Fig 6D) and studies.

Figure 6.

Early experimental protocol required separate groups for each target mean arterial pressure (MAP) and separate subgroups for aqueous humor flow and ciliary blood flow. Protocol entailed a 60 min baseline period followed by 75 min of measurements at a target MAP (e.g. 40 mmHg experiments are shown). Panels A and B show the MAP and IOP traces and corresponding fluorescein decay curves used to calculate aqueous humor flow. (circles: cornea fluorescein concentration, triangles: anterior chamber fluorescein concentration, filled symbols: normal blood pressure, open symbols: blood pressure held at a target pressure of 40 mmHg) Panel C shows the ciliary blood flow trace during the same protocol in a different animal. Panel D shows the averages and standard errors for the achieved MAPs for each target MAP group and each aqueous humor flow (Faq) and ciliary blood flow (BFcil) subgroup, as well as the IOPs. (Reitsamer and Kiel, 2003, with permission of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology)

Figure 7.

More recent protocols with simultaneous aqueous humor flow and ciliary blood flow measurements. Left panel shows experimental tracings and fluorescein decay curves for 60 min of baseline followed by infusion of isoproterenol at normal MAP 60 min then continued isoproterenol infusion with MAP mechanically decreased to 40 mmHg. Other groups underwent the same protocol with target MAPs of 80 and 55 mmHg. Right panel shows a simpler protocol entailing 60 min of baseline followed by topical dorzolamide and another 60 min of measurements. (MAP: mean arterial pressure, IOP: intraocular pressure, BFcil: ciliary blood flow, OVP: orbital venous pressure, BFcar: carotid blood flow, HR: heart rate, [F]c: cornea fluorescein concentration, [F]ac: anterior chamber fluorescein concentration, ctrl: control, iso: isoproterenol, dorz: dorzolamide)

4.5 Statistics

Comparisons within groups were analyzed by paired t-tests or repeated measures ANOVA. Comparisons between groups were analyzed by unpaired t-tests or ANOVA. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant. All data are presented as the mean ± the standard error (S.E.).

5. Relationship between ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor production

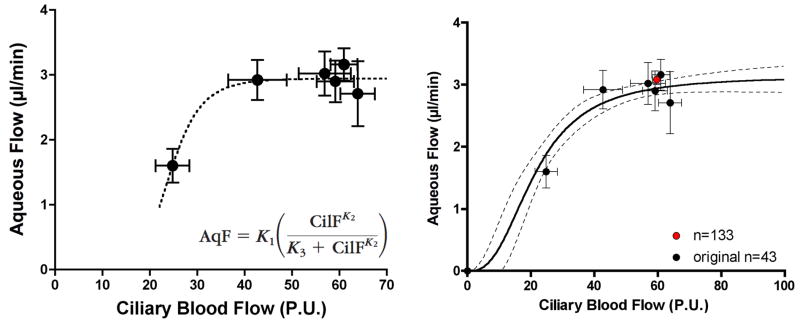

5.1 Control

The original study data and data from subsequent studies indicate that in the anesthetized rabbit model the normal aqueous humor flow rate is 3.06 ± 0.6 μl/min (mean ± SE, n=225) and the LDF ciliary blood flow is 58.01 ± 0.97 P.U. (mean ± SE, n=213); based on experiments with simultaneous measurements (n=133) the values are 3.08 ± 0.08 μl/min and 59.65 ± 1.27 P.U., respectively. When ciliary blood flow was varied under control conditions by holding MAP at 40, 55, 70 and 80 mmHg, aqueous humor flow was constant until ciliary blood flow was decreased below ≈40 P.U., roughly 74% of its baseline value; below that level of ciliary perfusion, aqueous humor flow decreased as a seemingly linear function of ciliary blood flow. Based on these results we proposed that aqueous humor production is independent of ciliary blood flow above a critical level of ciliary perfusion, and blood flow dependent below that critical level of perfusion. The underlying hypothesis was that ciliary blood flow delivers something essential to aqueous humor production, possibly oxygen, which is required to sustain the active ionic transport that drives aqueous humor production. Excess delivery of this essential factor beyond the current needs dictated by the neurohumoral milieu, would simply pass through in the venous effluent, whereas insufficient delivery of this factor would compromise aqueous humor production.

Although he did not measure ciliary blood flow, Bill used hemorrhage to achieve target MAPs at different levels while measuring aqueous humor flow in anesthetized monkeys. (Bill, 1970) In that study, the IOP was held constant at 12 mmHg, and the baseline MAP values were higher (i.e., 119 ± 7 mmHg) than in this rabbit study. However, despite the differences between the studies, Bill’s finding that aqueous humor production in monkeys is unaffected by decreases in MAP until MAP falls below 70 – 90 mmHg is qualitatively similar to the rabbit results, and suggests that a critical ciliary blood flow exists in other species.

Another secretory tissue exhibits similar behavior. In the stomach, acid secretion is blood flow dependent when blood flow is reduced below a critical level, and blood flow independent when blood flow is increased above that critical level. (Holm et al., 1981; Perry et al., 1982a; Perry et al., 1982b) Like aqueous humor production, acid secretion is a metabolically active process dependent on sufficient oxygen delivery to drive ionic transport. If blood flow is raised above the critical level, the excess oxygen is not extracted and passes through to the venous circulation. However, as blood flow is reduced below the critical level, even maximal oxygen extraction fails to provide sufficient ATP to maintain ionic transport and so secretion falls. Other substrates are also possible rate limiting candidates, but oxygen seems important. The situation appears similar for aqueous humor production.

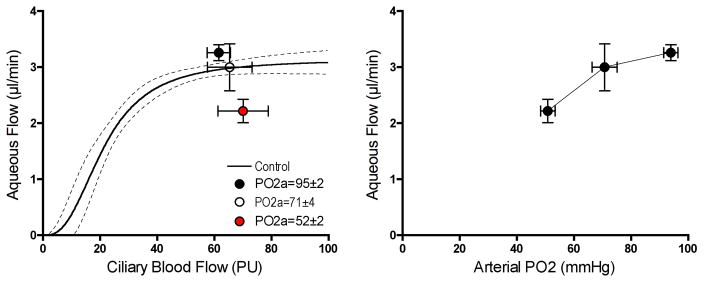

5.2 Oxygen

Figure 9 shows the effect of graded hypoxia on ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor flow. Ciliary blood flow was unchanged when the arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PO2 a) was reduced in two steps from 95 mmHg (normoxia) to ≈70 mmHg and then ≈50 mmHg by respiring the animals with air progressively depleted of oxygen. The mild level of hypoxia had no significant effect on aqueous humor flow, but the more severe hypoxia significantly reduced aqueous humor flow. Since ciliary blood flow was unchanged, it is likely that the delivery of only oxygen was reduced while the delivery of other potentially rate limiting factors for aqueous humor production were maintained. Thus, it appears that oxygen delivery by ciliary blood flow is indeed essential for aqueous humor production and that production falters when oxygen delivery falls below a critical level.

Figure 9.

Effect of graded hypoxia on ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor flow (n=20). Mild hypoxia had no effect on either variable, but more severe hypoxia reduced aqueous humor flow without changing ciliary blood flow, indicating a critical level of oxygen delivery is needed to sustain aqueous humor production.

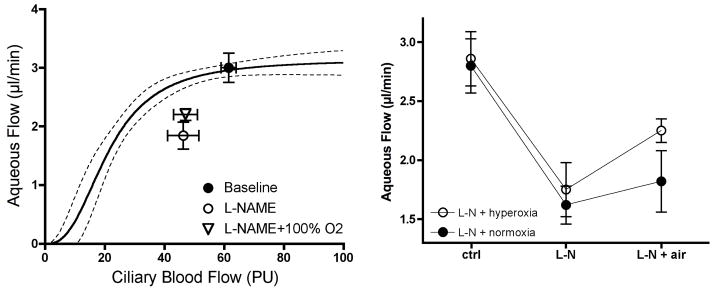

If oxygen delivery is the critical factor, then it seems reasonable to hypothesize that giving supplemental oxygen during an imposed decrease in ciliary blood flow would sustain aqueous humor production. When given systemically, the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor L-NAME is a potent ciliary vasoconstrictor that decreases ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor flow. (Kiel et al., 2001) Since L-NAME’s effects are sustained for several hours, we compared the responses in two groups of animals, both respired on room air during a 60 min baseline period, whereupon both were given L-NAME and continued on room air for a second 60 min period, and then one was switched to 100% oxygen while the other continued on room air for a final 60 min period. As shown in Figure 10, hyperoxia did significantly increase aqueous humor flow compared to normoxia, but it did not restore aqueous humor flow back to control.

Figure 10.

100% oxygen breathing partially reverses L-NAME (5 mg/kg, iv, n=22) induced decrease in aqueous humor flow.

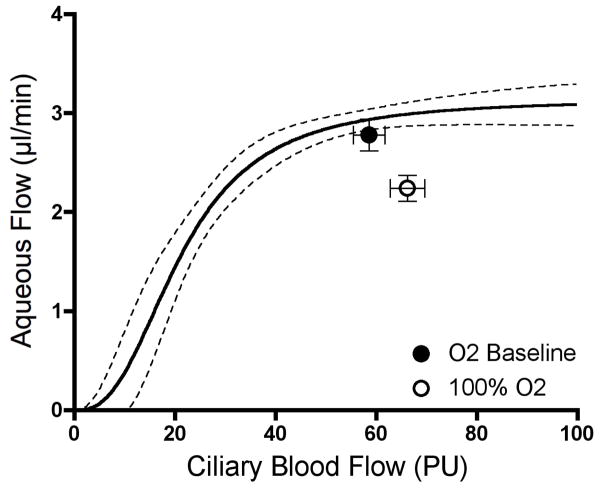

The L-NAME plus hyperoxia results were suggestive, but did not fully support oxygen as the critical factor, which prompted a control experiment to determine the effect of hyperoxia alone on aqueous humor flow. Surprisingly, 100% oxygen breathing significantly decreased aqueous humor flow and slightly but significantly increased ciliary blood flow. Both responses are difficult to explain since hyperoxia more commonly elicits vasoconstriction and does not alter baseline function. Nonetheless, an inhibitory effect on aqueous humor flow has been noted or suspected previously, (Gallin-Cohen et al., 1980; Krupin et al., 1980; Yablonski et al., 1985) and so a lower level of hyperoxia and carbogen needs to be tested in the future. Such studies may reveal if hyperoxia activates an unknown feedback loop that operates to prevent excess aqueous humor oxygen delivery to the lens. (Shui et al., 2006) In the meantime, the hypoxia data are consistent with oxygen being an important factor delivered by ciliary blood flow.

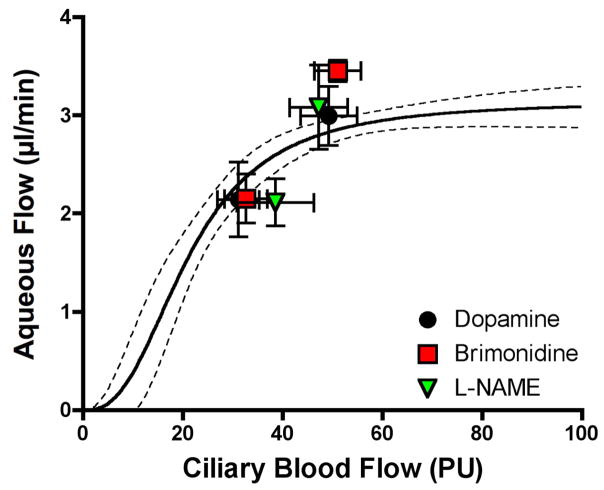

5.3 Indirect versus direct modulation of aqueous humor production

Another problem with the L-NAME plus hyperoxia study is that the decrease in aqueous humor flow was greater than would be expected for the decrease in ciliary blood flow based on the results for mechanical manipulation of MAP, i.e., the L-NAME data point is outside the 95% confidence boundary in Figure 10. By contrast, as shown in Figure 12, an earlier study with L-NAME (Kiel et al., 2001) placed the L-NAME response near the confidence boundary in keeping with the responses to two other drugs that caused ciliary vasoconstriction, topical brimonidine and a high dose infusion of dopamine. For brimonidine and dopamine, the responses lie within the confidence boundary suggesting that the decreases in ciliary blood flow account for the aqueous humor flow responses; an indirect effect rather than a direct inhibition of aqueous humor production within the epithelial bilayer.

Figure 12.

Effects of dopamine (600 μg/min, iv, n=18), brimonidine (40 μl topical, 0.15%, n=20), and L-NAME (5 mg/kg, iv, n=22) on ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor flow.

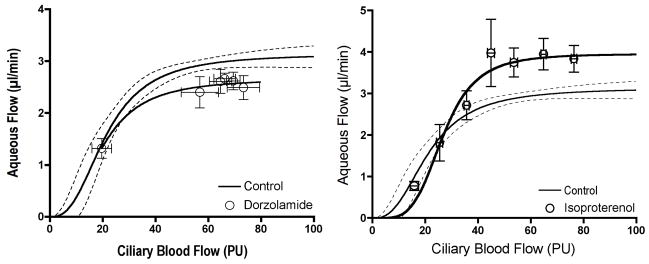

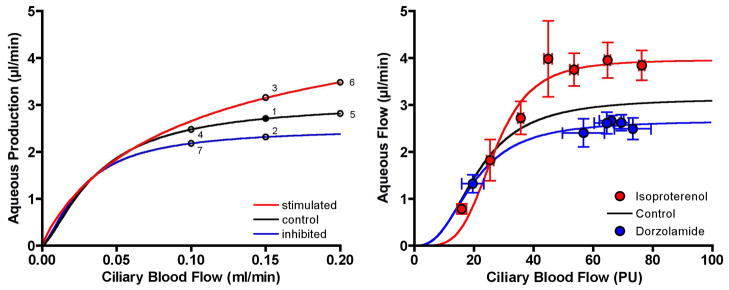

This issue of aqueous humor production being altered by an indirect vascular mechanism versus a direct effect on epithelial transport is complex. Work in the stomach indicates that stimulants of acid secretion (e.g. pentagastrin) shift the relationship between mucosal blood flow and acid secretion upwards while inhibitors (e.g. isoproterenol) shift the relationship downwards. (Perry et al., 1983) An interpretation of this behavior is that the set point for secretory activity is determined by the neurohumoral or drug exposure of the secretory cells, and that set point is achieved if the blood flow delivery of oxygen and nutrients is sufficient to meet the metabolic demand. As noted earlier, if blood flow falls below a critical level, secretion falters. Figure 13 suggests similar behavior for the relationship between ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor production, since the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor dorzolamide shifts the plateau portion of the relationship downward (Reitsamer et al., 2009), while the beta agonist isoproterenol shifts the plateau portion of the relationship upwards. Dorzolamide is thought to inhibit aqueous humor production directly by reducing the availability of bicarbonate for epithelial transport, and isoproterenol is thought to stimulate aqueous humor production directly via epithelial cAMP activation of ionic transport. (Gabelt et al., 2006)

Figure 13.

Dorzolamide (topical, 50 μl, 2%, n=54) shifts the plateau portion of the relationship between ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor flow downwards, and isoproterenol (0.02 μg/min/kg, iv, n=37) shifts the plateau upwards. (Note: a low dose of isoproterenol was chosen that did not alter MAP.)

5.4 Neurohumoral modulation

The list of potential neurohumoral modulators of aqueous humor production is long and we have evaluated only a few. And frankly, all of the results are perplexing.

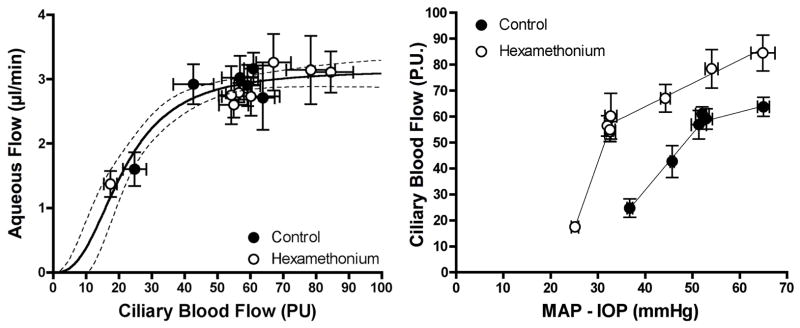

An obvious starting point to study neurohumoral control is to eliminate neural control with a ganglionic blocker. We had previous success using hexamethonium to evaluate choroidal autoregulation and so used it again. (Kiel, 1999) Unlike the choroid where ganglionic blockade revealed a tonic level of neural vasodilator tone, there appears to be a tonic level of neural vasoconstrictor tone in the ciliary circulation since hexamethonium shifted the pressure-flow relationship upwards and to the left (Figure 14). However, despite the wider range of ciliary blood flow, the relationship between ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor flow was not altered. Although we had anticipated a downward shift in the relationship due to the loss of neural input, normal levels of aqueous humor production occur in patients with Horner’s syndrome or after adrenalectomy, and in primates given atropine. (Bill, 1969; Larson and Brubaker, 1988; Maus et al., 1994; Wentworth and Brubaker, 1981) Consequently, the lack of effect of ganglionic blockade is perhaps reasonable.

Figure 14.

Ganglionic blockade with hexamethonium (25 mg/kg, iv, n=60) provided a wider range of ciliary blood flow but did not alter the relationship between ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor flow. The upward and leftward shift in the pressure-flow relationship indicates a tonic level of neural constrictor tone in the control condition.

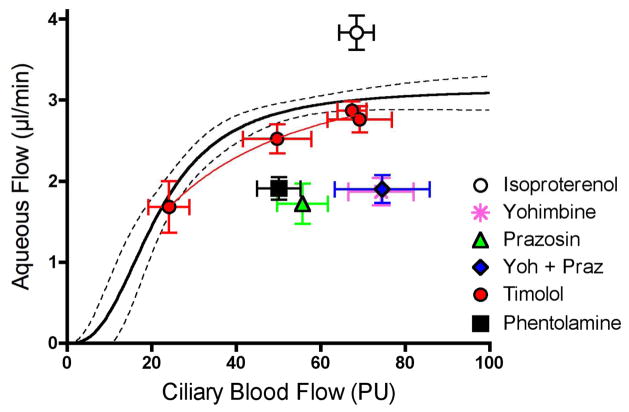

More perplexing were the responses to adrenergic agonists and antagonists shown in Figure 15. As noted earlier, the beta-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol increased aqueous humor flow, indicating that beta-adrenergic receptors were present and functional. However, the beta-adrenergic antagonist timolol had little effect on the relationship between ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor flow. Given the lack of effect of ganglionic blockade, this would suggest little tonic sympathetic tone, which might be expected based on the rabbit circadian IOP cycle. (Dinslage et al., 1998; McLaren et al., 1996; Schnell et al., 1996) And yet, the non-selective alpha adrenergic antagonist phentolamine, (Kiel and Reitsamer, 2007) as well as the selective alpha adrenergic antagonists prazosin and yohimbine, all significantly decreased aqueous humor flow. Clearly, there was adrenergic tone present, and it was dominated by alpha-adrenergic receptors rather than beta-receptors. This is in contrast to humans where the widespread successful use of beta-adrenergic antagonists to inhibit aqueous humor production and lower IOP indicates that beta-adrenergic mechanisms predominate. The seeming paradox may be a species difference, or perhaps alpha-adrenergic antagonists warrant further study as ocular hypotensive agents.

Figure 15.

Adrenergic modulation. Beta-adrenergic stimulation with isoproterenol (0.02 μg/min/kg, iv, n=37) stimulates aqueous humor flow, but the beta-adrenergic antagonist timolol (50 μl, 0.5%, n=55) does not inhibit aqueous humor flow. However, the lack of timolol effect is not due to the absence of adrenergic tone since the alpha adrenergic antagonists phentolamine (0.1 mg/kg, iv, n=16), prazosin (0.001 mg/kg/min, iv, n=10), yohimbine (1 mg/kg/min, iv, n=10) and a mixture of yohimbine and prazosin (Yoh+Praz, n=9) all inhibit aqueous humor flow.

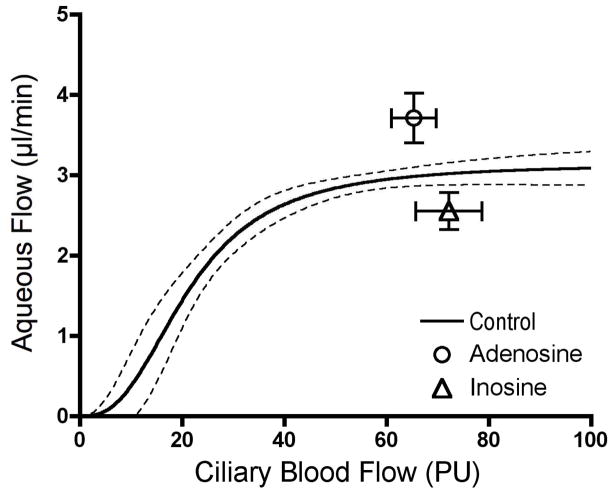

A final perplexing finding is the responses to the related compounds adenosine and inosine. Adenosine is a neurotransmitter (Burnstock, 2006; Ralevic and Burnstock, 1998) and a mediator of vascular autoregulation (Berne, 1980), and adenosine receptors have clear but complex effects on aqueous humor dynamics. (Avila et al., 2001; Crosson, 2001) Inosine is a degradative product of adenosine, and generally thought to have low affinity for adenosine receptors and consequently to be relatively inactive, though this view appears to be changing. (Hasko et al., 2004) Nonetheless, while adenosine caused a significant increase in aqueous humor flow, inosine decreased it (Figure 16). Identifying the receptors involved in both responses requires further investigation.

Figure 16.

Opposite responses to adenosine (60 μg/min/kg, iv, n=29) and inosine (90 μg/min/kg, iv, n=10).

6. Theoretical model of ocular hydrodynamics

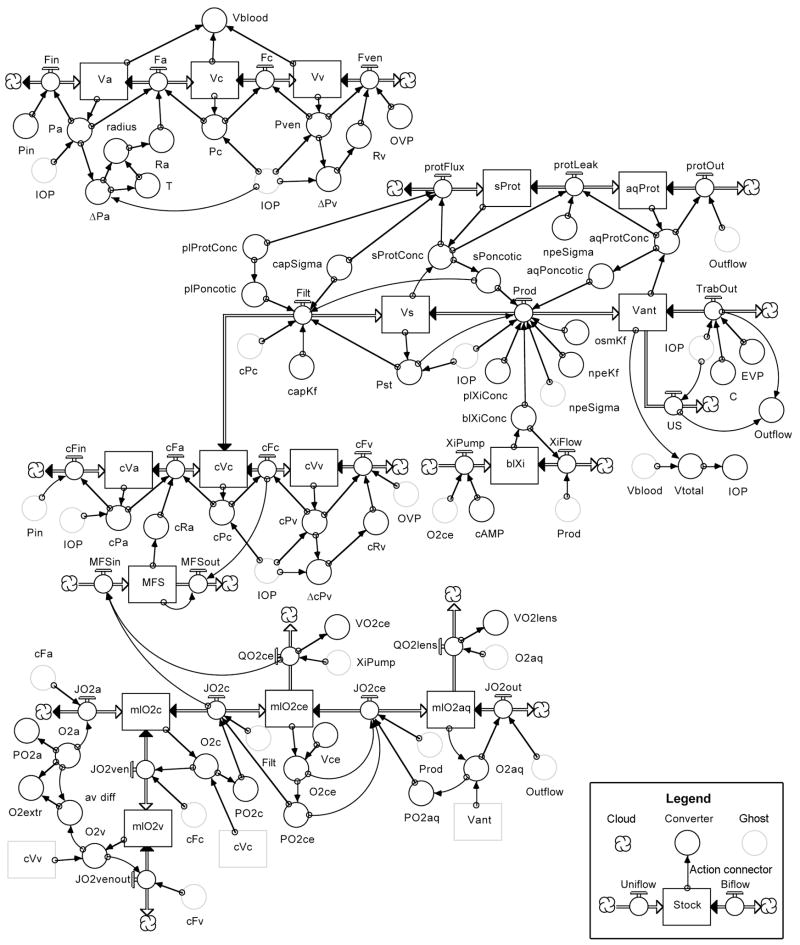

In the 8th Edition of Adler’s Physiology of the Eye, Moses provided his most thorough mathematical analysis of aqueous humor dynamics, relying heavily on his own and Barany’s earlier analyses. (Barany, 1963; Moses, 1987) However, Moses also rightly raised a cautionary note “to warn those readers who would extrapolate from the mathematical model presented here: predictions from such a model must be checked by observation and experiment. The actual living organism is so complex that our model must be a reduction of fact, and extrapolations from it may be worthless without further information.” The relationship between ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor flow offers some of that additional information, and in the tradition of Brubaker’s analog model of aqueous humor dynamics (Brubaker, 1976), the senior author has attempted to incorporate that information into a computer based mathematical model of ocular hydrodynamics. (Kiel and Shepherd, 1992; Zamora and Kiel, 2010) The model diagram is shown in Figure 17 and the underlying equations are provided in the Appendix.

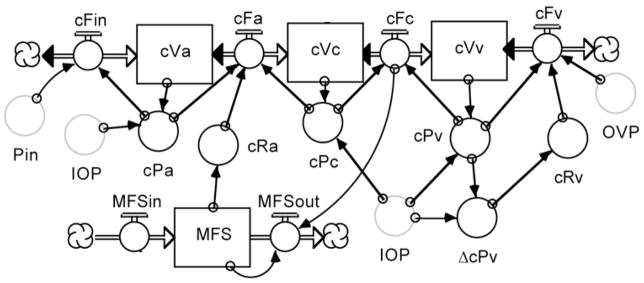

Figure 17.

Flow diagram of model of ocular hydrodynamics written in STELLA. There are several graphic objects in a STELLA model. “Stocks” (or reservoirs) are represented by a rectangular box that can gain or lose material. Flow regulators are represented by a spigot on a double-lined arrow connecting stocks or clouds (special stocks that provide continuous sources or sinks for the flowing material). “Uniflow” and “Biflow” regulators permit flow in one direction indicated by the single arrowhead or in both directions indicated by arrowheads at both ends of the double line, respectively. “Converters” are represented by a circle that can contain an equation or a constant. “Action Connectors” are represented by single-lined arrows that pass information between objects. Copies of an object, represented as a faintly outlined grey “ghost” of the original, can be placed at different locations on the screen to avoid long, confusing tangles of arrows. All variables are defined in the Appendix and further explained in the text.

Appendix.

ocular hydrodynamics model equations

| Symbol | Variable | Value | Units | Equations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choroidal Circulation | ||||

| ΔPa | arterial transmural pressure | 45 | mmHg | ΔPa = Pa-IOP |

| ΔPv | venous transmural pressure | 2 | mmHg | ΔPv = Pv-IOP |

| Fa | arterial flow | 1 | ml/min | Fa = (Pa-Pc)/(Ra) |

| Fc | capillary flow | 1 | ml/min | Fc = (Pc-Pv)/((25-17)/1) |

| Fin | choroidal inflow | 1 | ml/min | Fin = (Pin-Pa)/((70-60)/1) |

| Fven | venous flow | 1 | ml/min | Fven = (Pv-Pout)/(Rv) |

| OVP | orbital venous pressure | 3 | mmHg | OVP = 3 (user defined) |

| Pa | arterial pressure | 60 | mmHg | Pa = Va/(0.02/60) |

| Pc | capillary pressure | 25 | mmHg | Pc = IOP+(0.1*10^(33.33333333*Vc)) |

| Pin | mean arterial pressure | 70 | mmHg | Pin = 70 (User defined) |

| Pv | venous pressure | 17 | mmHg | Pv = IOP+(0.1*10^(10.8419166*Vv)) |

| Ra | arterial resistance | 35 | mmHg/ml/min | Ra = 35/artRadius^4 |

| radius | arterial radius | 1 | A.U. | artRadius = T/(ΔPa)*7.80396528 |

| Rv | venous resistance | 9 | mmHg/ml/min | Rv = 6/(0.13+1.3/(1+exp(3.5*(−(ΔPv)+1.9743945582))))^4 |

| T | arterial wall tension | 1.48 | A.U. | T = 3.5*tan(0.025*(ΔPa)+2.1209)+5.4 |

| Va | arterial volume | 0.02 | ml | Va(t) = Va(t - dt) + (Fin - Fa) * dt |

| Vc | capillary volume | 0.06 | ml | Vc(t) = Vc(t - dt) + (Fa - Fc) * dt |

| Vv | venous volume | 0.12 | ml | Vv(t) = Vv(t - dt) + (Fc - Fv) * dt |

| Ciliary Circulation | ||||

| cFa | arterial flow | 0.15 | ml/min | cFa = (cPa-cPc)/cRa |

| cFc | capillary flow | 0.14725 | ml/min | cFc = (cPc-cPv)/((25-17)/(0.15-2.75e-03)) |

| cFin | ciliary inflow | 0.15 | ml/min | cFin = (Pin-cPa)/((70-60)/0.150) |

| cFv | venous flow | 0.14725 | ml/min | cFv = (cPv-Pout)/cRv |

| cPa | arterial pressure | 60 | mmHg | cPal = cVa/(0.001/60) |

| cPc | capillary pressure | 25 | mmHg | cPc = cVc/(0.002/25) |

| cPv | venous pressure | 17 | mmHg | cPv = cVv/(0.007/17) |

| cRa | arterial resistance | 233.33 | mmHg/ml/min | cRa = (100+266.6666666666/(1+exp(25*(MFS-0.5))))+deltacRa |

| cRv | venous resistance | 61.12 | mmHg/ml/min | cRv = 9/(0.15+0.6/(1+exp(4*(-(cPv-IOP)+1.81788580364))))^4 |

| cVa | arterial volume | 0.001 | ml | cVa(t) = Va(t - dt) + (cFin - cFa) * dt |

| cVc | capillary volume | 0.002 | ml | cVc(t) = Vc(t - dt) + (cFa - cFc - Filt) * dt |

| cVv | venous volume | 0.007 | ml | cVv(t) = Vv(t - dt) + (cFc - cFv) * dt |

| MFS | metabolic feedback signal | 0.85 | A.U. | MFS(t) = MFS(t - dt) + (MFSin - MFSout) * dt |

| MFSin | MFS production | 0.262 | A.U./min | MFSin = MFSin = (QO2ce/JO2c)*0.168974 |

| MFSout | MFS removal | 0.262 | A.U./min | MFSout = MFS*cFc*2.274004 |

| Oxygen Delivery and Consumption | ||||

| JO2a | arterial O2 inflow | 0.029527 | mlO2/min | JO2a=O2a*cFa |

| JO2c | capillary O2 flux | 2.74E-03 | mlO2/min | JO2c=(PO2c-PO2ce)*3e-5*1.5e-5*60*(5.7*0.75)/2e-3+PO2c*0.00003*Filt |

| JO2ce | epithelial O2 flux | 2.20E-05 | mlO2/min | JO2ce=(PO2ce-PO2aq)*3e-5*1.5e-5*60*5.7/0.125+O2ce*Prod |

| JO2cv | capillary O2 outflow | 0.02742 | mlO2/min | JO2cv=cFv*O2c |

| JO2out | aqueous O2 flux | 2.00E-06 | mlO2/min | JO2aq = O2aq*Outflow |

| JO2v | venous O2 outflow | 0.02742 | mlO2/min | JO2v = cFv*O2v |

| mlO2aq | aqueous ml O2 | 1.48E-04 | mlO2 | mlO2aq= mlO2aq(t - dt)+(JO2ce-QO2lens - JO2aq)*dt |

| mlO2c | capillary ml O2 | 3.64E-04 | mlO2 | mlO2c= mlO2c(t - dt) + (JO2a - JO2c - JO2v) * dt |

| mlO2ce | epithelial mlO2 | 8.20E-05 | mlO2 | mlO2ce(t) = mlO2ce(t - dt)+(JO2c - JO2ce - QO2ce)* dt |

| mlO2v | venous mlO2 | 1.27E-03 | mlO2 | mlO2v(t) = mlO2v(t - dt) + (JO2v - JO2vout) * dt |

| O2a | arterial O2 content | 0.19685 | mlO2/ml | O2a = 0.19685 (User defined) |

| O2aq | aqueous O2 content | 7.41E-04 | mlO2/ml | O2aq = mlO2aq/Vant |

| O2c | capillary O2 content | 0.1819 | mlO2/ml | O2c=mlO2c/cVc |

| O2ce | epithelial O2 content | 1.41E-03 | mlO2/ml | O2ce = mlO2ce/Vce |

| O2v | venous O2 content | 0.1819 | mlO2/ml | O2v = mlO2v/cVv |

| PO2a | arterial PO2 | 100 | mmHg | PO2a=(27/1.23)*LOGN(1/(1-SQRT(O2a/(0.15*1.34)))) |

| PO2aq | aqueous PO2 | 29.55 | mmHg | PO2aq = O2aq/3E-05[3E-05 =O2 solubility coefficient] |

| PO2c | capillary PO2 | 66.34 | mmHg | PO2c=(27/1.23)*LOGN(1/(1-SQRT(O2c/(0.15*1.34)))) |

| PO2ce | epithelial PO2 | 46.87 | mmHg | PO2ce= O2ce/3E-05 [3E-05 =O2 solubility coefficient] |

| QO2ce | epithelial O2 uptake | 2.72E-03 | ml/min | QO2ce = (0.03*0.068/XiPumP)*XiPump |

| QO2lens | lens O2 uptake | 2.11E-05 | mlO2/min | QO2lens = 0.00007407*O2aq/(O2aq+0.002) |

| VO2ce | epithelial O2 consumption | 4 | mlO2/min*100g | VO2ce= QO2ce/0.068*100 |

| VO2ce | oxygen uptake | 4 | ml/min/100g | VO2ce=QO2ce/0.068*100 |

| VO2lens | lens O2 consumption | 0.0114 | mlO2/min*100g | VO2lens= QO2lens/0.175*100 |

| Aqueous Humor Dynamics | ||||

| aqPoncotic | aqueous oncotic pressure | 0.11 | mmHg | aqPoncotic = (2.1*aqProtConc*100+0.1*(aqProtConc*100)^2 +0.006*(aqProtConc*100)^3) |

| aqProt | aqueous protein | 0.0001 | grams | aqProt(t) = aqProt(t - dt) + (protLeak - protOut) * dt |

| aqProtConc | aqueous [protein] | 0.0005 | grams/ml | aqProtConc = aqProt/Vant |

| blXi | basolateral Xi | 0.147 | μmol | blXi(t) = blXi(t - dt) + (XiPump - XiFlow) * dt |

| blXiConc | basolateral Xi concentration | 147 | μmol/ml | blXiConc = blXi/0.001 |

| C | trabecular facility | 0.00035 | ml/min/mmHg | C = 0.00245/(15-8) (User defined) |

| cAMP | Ionic pump stimulus | 1 | A.U. | cAMP = 1.0 (User defined) |

| capKf | filtration coefficient | 0.00044935 | ml/min/mmHg | capKf = 0.00044935 (User defined) |

| capSigma | cap. reflection coefficient | 0.96 | A.U. | npeSigma = 0.96 (User defined) |

| EVP | Episcleral venous pressure | 8 | mmHg | EVP=8 (user defined) |

| Filt | capillary filtration | 0.00275 | ml/min | Filt = capKf*((cPc-Pst)-capSigma*(plPoncotic-sPoncotic)) |

| IOP | intraocular pressure | 15 | mmHg | IOP = 15*10^((Vtotal-6)* 0.0215*1000) |

| npeKf | NPE Starling filtration coefficient | 0.00002 | ml/min/mmHg | npeKf = 0.00002 (User defined) |

| npeSigma | NPE protein reflection coefficient | 0.999 | A.U. | npeSigma = 0.999 (User defined) |

| osmKf | NPE osmotic filtration coefficient | 0.00153445 | ml/min/mmHg | osmKf = 0.00153445 (User defined) |

| Outflow | total outflow | 0.00275 | ml/min | Outflow = TrabOut+US |

| plPoncotic | plasma oncotic pressure | 20 | mmHg | plPoncotic = 2.1*plProtConc*100+0.1*(plProtConc |

| plProtConc | plasma [protein] | 0.066 | grams/ml | plProtConc = 0.066 (User defined) |

| plXiConc | plasma Xi concentration | 145 | μmol/ml | plXiConc = 145 (User defined) |

| Prod | aqueous production | 0.00275 | ml/min | Prod=osmKf*(blXiConc-plXiConc)+(npeKf*((Pst-IOP)-npeSigma*(sPoncotic-aqPoncotic))) |

| protFlux | capillary protein flux | 0.000001 | grams/min | protFlux = (1-npeSsigma)*(plProtConc-sProtConc)-0.0003 |

| protLeak | NPE protein flux | 0.000001 | grams/min | protLeak = (1-npeSigma)*(sProtConc-aqProtConc)-0.000057 |

| protOut | aq. protein removal | 0.000001 | grams/min | protOut = aqProtConc*Outflow |

| Pst | stromal tissue pressure | 15 | mmHg | Pst = Vs/(0.0136/15) |

| sPoncotic | stromal oncotic pressure | 17 | mmHg | sPoncotic = (2.1*sProtConc*100+0.1*(sProtConc*100)^2 + 0.006*(sProtConc*100)^3) |

| sProt | stromal protein | 0.0008 | grams | sProt(t) = sProt(t - dt) + (protFlux - protLeak) * dt |

| sProtConc | stromal [protein] | 0.0587 | grams/ml | sProtConc = sProt/Vs |

| TrabOut | trabecular outflow | 0.00245 | ml/min | TrabOut = (IOP-Pout)*C |

| US | uveoscleral outflow | 0.0003 | ml/min | US = 0.0004*IOP/(IOP+5) |

| Vant | anterior chamber volume | 0.2 | ml | Vant(t) = Vant(t - dt) + (Prod - TrabOut - US) * dt |

| Vs | stromal volume | 0.0136 | ml | Vs(t) = Vs(t - dt) + (Filt - Prod) * dt |

| Vtotal | total ocular volume | 6 | ml | Vtotal = Vant+Va+Vc+Vv+5.6 |

| XiFlow | basolateral Xi removal | 0.404 | μmol/min | XiFlow = Prod*blXiConc |

| XiPump | basolateral Xi pump | 0.404 | μmol/min | XiPump = cAMP*6.603291e-8/(0.02+2500000/(1+exp(17000*(O2ce+1.0e-7))))^4 |

6.1 Model description

The model was developed in STELLA (ISEE Systems, Lebanon, NH), a graphical programming language designed specifically for creating iterative models and well suited for modeling hydrodynamic processes. STELLA objects are selected from a menu-bar and positioned with the mouse on the screen to create a diagram similar to a programmer’s flow chart. Once the objects are placed and connected, clicking on a stock calls a dialog box where the initial amount of material is specified (e.g. Va = 0.02 ml). The same dialog box also shows the equation created automatically by STELLA based on the flows entering and leaving the reservoir (e.g. Va = Va + (Fin − Fa)•dt). Clicking on a flow regulator calls a dialog box to enter the equation governing flow through the regulator using the variable values provided by the action connectors (e.g. Fa = (Pa - Pc) ÷ Ra). Similarly, clicking on a converter calls a dialog box where the user can enter a constant (e.g. Pin = 70 mmHg) or an equation to convert one or more variables into another (e.g. Pa = Va ÷ Ca).

Once the initial values, constants and equations have been assigned to the objects in the diagram, the model is executed by issuing a run command. STELLA execution begins with an initialization phase during which the program ranks the equations in required order of execution and calculates their initial values. This is followed by a runtime phase where each iteration begins by calculating the change in the stocks during the preceding interval, dt, to determine the new values for the stocks, which are then used to calculate the new values for the flows and converters. At the end of each iteration, the simulation time is updated by an increment of dt until the simulation time equals the pre-specified end time for the simulation. The values for all variables at each iteration (or a longer time interval) can be displayed graphically or in a table. Perturbations are simulated using a variety of built-in commands to change single or multiple variables at specific time points during a run (e.g. Pin = 70 + step(−10,5) will decrease Pin by 10 mmHg at the 5 minute time point in the simulation), and the remaining variables are then iteratively recalculated based on this new input and the interactions with the other variables.

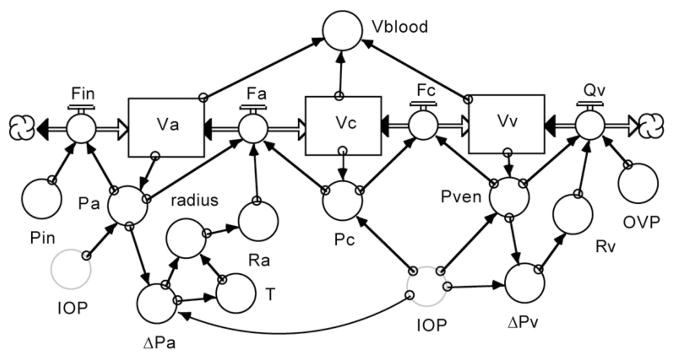

Figure 18 shows the choroidal section of the model. The flow chart starts at the left with blood flowing sequentially from the systemic arterial circulation (far left cloud) into the choroidal arterial (Va), capillary (Vc) and venous reservoirs (Vv) and then into the systemic venous circulation (far right cloud), with the rate of flow between reservoirs set by their pressure gradients and resistances. Choroidal arterial resistance (Ra) is under myogenic autoregulatory control, which responds to the transmural pressure gradient 3 (ΔPa) and the resulting vascular wall tension (T) to determine the vessel radius. (Kiel and Shepherd, 1992) Choroidal venous resistance (Rv) is a passive function of the transmural pressure gradient 3 (ΔPv). The IOP exerts a compressing force on the vessels, which modulates their compliance and pressures (Pa, Pc and Pven).

Figure 18.

Choroidal blood flow section of eye model.

Figure 19 shows the ciliary vascular segment of the model. Here the blood flow again proceeds down the pressure gradient from systemic circulation (Pin) to the venous circulation (OVP) with interposed resistance between the arterial (cVa) and capillary compartments (cVc), and the capillary and venous compartments (cVv). The ciliary arterial resistance (cRa) is modulated by a metabolic feedback signal (MFS) driven by the metabolic demand to oxygen delivery ratio. The ciliary venous resistance (cRv) is again a passive function of the transmural pressure gradient, and the vascular compliances are modulated by the IOP.

Figure 19.

Ciliary blood flow section of the model.

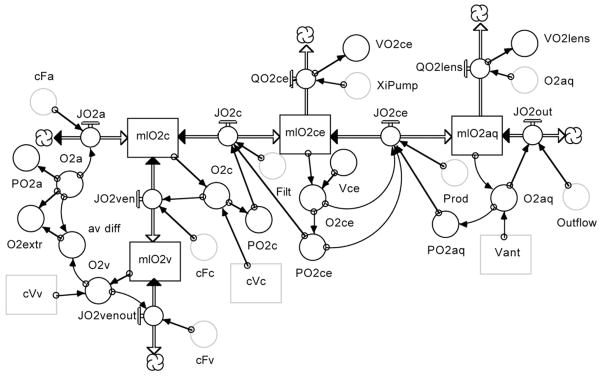

Figure 20 shows the oxygen utilization segment. The model assumes that O2 enters the ciliary tissue by convective vascular delivery (JO2a), with the oxygen entering the tissue by diffusion and convection (JO2c), and the remainder exiting in the venous blood (JO2v). The oxygen entering the tissue is either consumed by the epithelial bilayer (QO2ce) or the lens (QO2lens), or leaves the eye by convection with the aqueous humor outflow (JO2out). The oxygen flux from capillary to the bilayer is defined by:

Figure 20.

Oxygen delivery and consumption segment of the model.

Here, (PO2c-PO2ce) is the PO2 gradient for diffusion, K is the oxygen solubility coefficient, D is oxygen diffusion coefficient, SA is the vascular surface area which is estimated to be 75% of the epithelial surface area, dX is the diffusion distance, and the convection is the plasma dissolved oxygen times the rate of capillary filtration (which equals aqueous humor production at steady state). The oxygen flux across the epithelial bilayer is defined by:

Here, the gradient is (PO2 ce-PO2 aq), K and D are the same, the SA is 5.7 cm2, the diffusion distance to the lens is 1.25 mm, and the convection is the dissolved oxygen times the rate of aqueous humor production. The remaining variables are either steady state values from the model inthe appendix, conversions of amounts to concentrations, or concentrations to PO2 using the hemoglobin dissociation curve or the oxygen solubility coefficient. To obtain an estimate of the PO2 distribution, the epithelial oxygen consumption (VO2 ce) was set at 4 mlO2/min*100g (similar to the retina) and the lens oxygen consumption at 0.012 ml/min*100g (similar to the 8 μlO2/hr*g reported in the literature). Based on this analysis, the model predicts a capillary PO2 of 66 mmHg, an epithelial PO2 of 47 mmHg, and an aqueous humor PO2 of 30 mmHg.

Figure 21 shows the aqueous humor dynamics segment of the model. Aqueous humor production begins as an ultrafiltration of plasma (Filt) from the ciliary capillary compartment (cVc) driven by the Starling equilibrium:

Figure 21.

Aqueous humor dynamics segment of the model.

Here, capKf is the capillary filtration coefficient, cPc and Pst are the capillary and stromal hydrostatic pressures, capSigma is the protein reflection coefficient and plPoncotic and sPoncotic are the plasma and stromal oncotic pressures. Protein movement from capillary to stroma occurs down the concentration gradient impeded by capSigma.

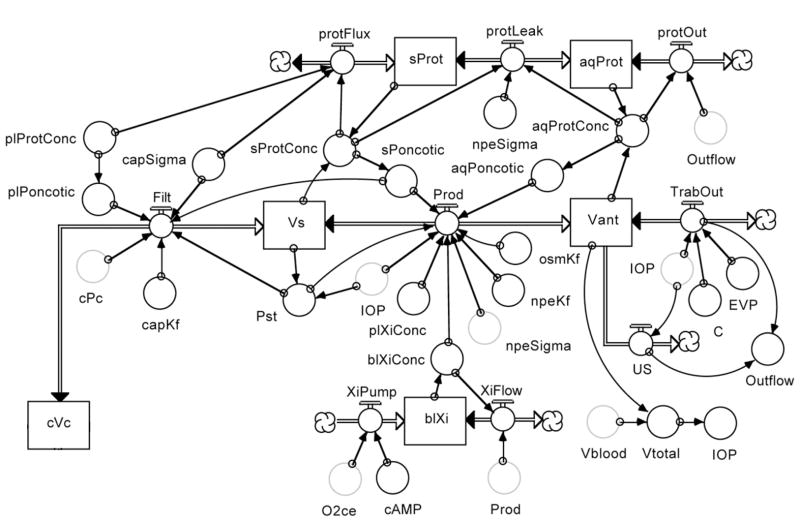

The movement of fluid across the epithelial bilayer (Prod) is the result of the osmotic gradient established by active ionic transport and the Starling equilibrium:

Here, osmKf is the bilayer osmotic filtration coefficient, blXiConc and plXiConc are the ionic concentrations in the basolateral space and plasma (stromal ionic concentration is assumed equal to stromal ionic concentration), npeKf is the bilayer filtration coefficient, Pst and IOP are the hydrostatic pressure gradient, npeSigma is the bilayer protein reflection coefficient and sPoncotic and aqPoncotic are the oncotic pressure gradient. The protein movement across the bilayer (prot leak) is a function of the protein concentration gradient and the protein reflection coefficient. Protein leaves the eye by convection with aqueous humor outflow.

blXiConc is a function of oxygen availability (O2ce) and the level of second messenger stimulation (cAMP) that drive ionic pumping (XiPump) and the convective washout (XiFlow) of ions by the movement of fluid across the bilayer (Prod). (Note that the symbol “Xi” represents generic ions rather than a specific ion.)

Aqueous humor leaves the eye by trabecular and uveoscleral outflow. Trabecular outflow (Trab Out) is driven by the pressure gradient from IOP to episcleral venous pressure (EVP) against the outflow facility (C). Uveoscleral outflow (US) is relatively constant until IOP falls to low levels. EVP is a function of orbital venous pressure (OVP).

The IOP is an exponential function of the total ocular volume, assuming fixed volumes for the lens and vitreous, and variable volumes for the aqueous humor (Vant) and blood (Vblood). The volumes in the posterior chamber and non-choroidal circulations are assumed negligible.

6.2 Model simulations

The left graph in Figure 22 shows three model generated curves for aqueous humor production plotted as a function of ciliary blood flow: a control curve for normal secretory stimulation (Ctrl), a curve for a state of secretory stimulation (Stim), and a curve for a state of secretory inhibition (Inhib). Point #1 on the control curve occurs at a normal ciliary blood flow (150 μl/min) and aqueous humor production (2.75 μl/min). A drug that acts directly on the active secretion by the NPE cells (e.g. by changing intracellular cAMP) can decrease (Point #2) or increase (Point #3) production without changing ciliary blood flow. Alternatively, a drug that causes ciliary vasoconstriction (Point #4) or vasodilation (Point #5) without altering the stimulus for secretion can nonetheless decrease or slightly increase production. A third scenario is that ciliary autoregulation is linked to metabolism so that a drug that stimulates secretion causes a concomitant vasodilation (Point #6) while a drug that inhibits secretion causes a vasoconstriction (Point #7). The right panel of Figure 22 shows similar shifts in the plateau portion of the relation between ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor flow with a secretory inhibitor and stimulant.

Figure 22.

Left: model simulation curves for ciliary blood flow versus aqueous humor production under stimulated, control and inhibited conditions. Points are: 1: control production and blood flow; 2: inhibited production without change in blood flow; 3: stimulated production without change in blood flow; 4: ciliary constriction with flow-dependent decrease in production; 5: ciliary dilation with small flow-dependent increase in production; 6: stimulated production with metabolic dilation; 7: inhibited production with metabolic constriction. Right: relation between ciliary blood flow and aqueous flow in the rabbit under control conditions and during secretory stimulation with isoproterenol (0.02 μg/min/kg, iv, n=37) and secretory inhibition with dorzolamide (2%, 50 μl, topical, n = 62).

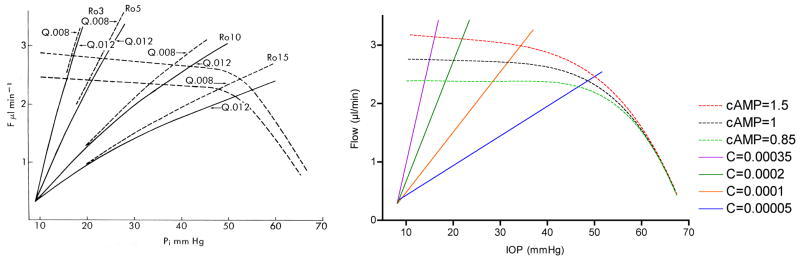

This article began by invoking Moses’ iconic 1981 graph depicting steady state IOP as the intersection of aqueous humor inflow and outflow, and the enigma of his aqueous humor inflow curves. The experiment to verify his inflow curves was not technically possible then and would be exceedingly difficult with today’s technology. The difficulty is that our techniques to measure aqueous humor flow rely on the clearance or dilution of tracers in the anterior chamber, but the most straightforward way to raise IOP is to add fluid to the eye, which would interfere with the aqueous humor flow measurement. The alternative ways to increase IOP would be to decrease trabecular facility or increase EVP, but neither can be done with precision. It is in these circumstances when the model can be useful.

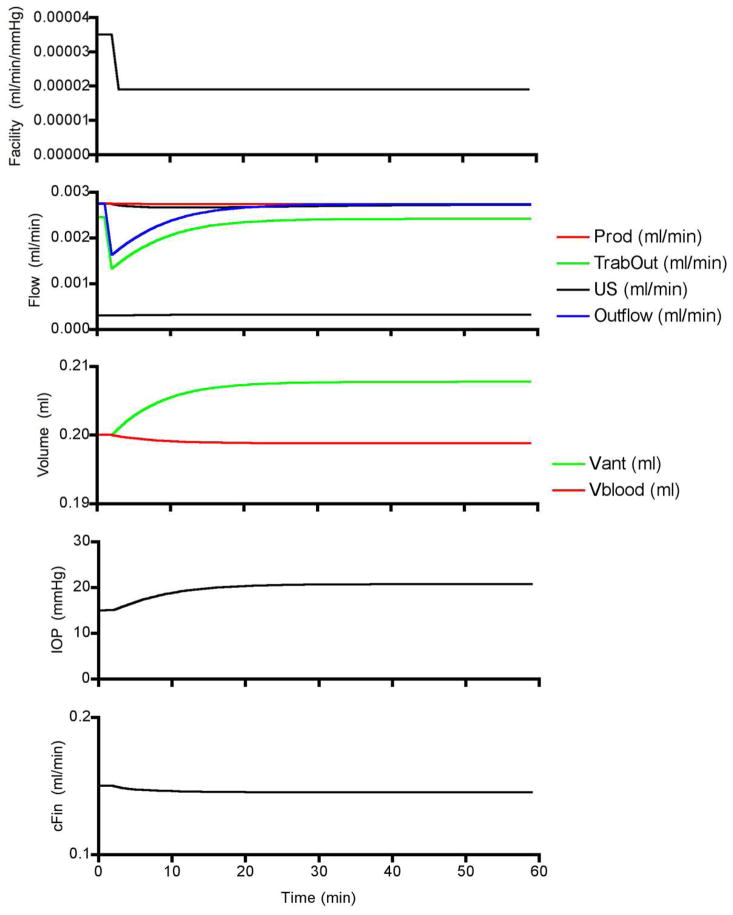

Figure 23 shows the simulated response to a step decrease in outflow facility sufficient to raise IOP from 15 to 20 mmHg. The decrease in facility causes a decrease in trabecular outflow while aqueous humor production remains unchanged and so aqueous humor begins accumulating in the anterior chamber. As aqueous humor accumulates, the IOP begins to rise until the pressure gradient for trabecular outflow is sufficient to overcome the reduced facility and inflow and outflow re-equilibrate. Ciliary autoregulation counters the modest reduction in ciliary perfusion pressure, which maintains aqueous humor production. Repeated simulations at progressively lower facilities and different levels of production stimulation and inhibition (i.e., raised and lowered “cAMP”) provides a simulated version of Moses’ inflow experiments. The outflow experiments are simulated by increasing production at different fixed facilities. Figure 24 shows that, although there are subtle differences between the two graphs (e.g. the model does not use Brubaker’s obstruction coefficients), the model simulation is remarkably similar to Moses’ original graph.

Figure 23.

Model simulated responses to a step decrease in facility.

Figure 24.

Moses’ original 1981 graph (left) and the results of model simulations (right). In both graphs, the steady state IOP is defined by the intersection of aqueous humor inflow and outflow.

7. Conclusion and future directions

Moses’ admonition to be wary of mathematical models in the absence of experimental verification is timeless advice; however, his inflow curves with the “equation unknown” appear to have been remarkably accurate. The experimental results presented in this article indicate that there is a dynamic relationship between ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor production, with production being blood flow independent above a critical level of perfusion, and blood flow dependent below it. The results also show that the plateau portion of the relationship shifts up or down depending on the level of secretory stimulation or inhibition. Given that IOP is a determinant of the perfusion pressure, these results are consistent with Moses’ predicted inflow behavior. The finding that oxygen is a critical factor provided by the ciliary circulation is a piece of extra information, but he might well have predicted that as well, if asked.

For the future, resolving the pharmacologic paradoxes (e.g. adrenergic and purinergic modulation) may be beneficial in the quest for new glaucoma treatments. At the more basic level, refining our understanding of ciliary oxygen delivery and utilization, and identifying other critical factors delivered by the ciliary circulation will provide new insights into the complex physiology of aqueous humor production.

Figure 8.

Relationship between ciliary blood flow and aqueous humor production in anesthetized rabbits. The left graph shows the relationship based on the original 43 rabbits using an arbitrary function to fit the data. (Reitsamer and Kiel, 2003, with permission of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology) The right graph shows the original data set plotted on a slightly revised regression curve based on additional experiments and also shows the normal values for aqueous humor flow and ciliary blood flow based on 133 simultaneous measurements. (AqF: aqueous flow, CilF: ciliary blood flow, K1–3: constants)

Figure 11.

Hyperoxia increases ciliary blood flow and decreases aqueous humor flow (n=8)

Acknowledgments

NIH EY09702 (JWK), a Research to Prevent Blindness Lew R Wasserman Merit Award (JWK), Austrian FWF J1866-MED (HAR), the van Heuven endowment (JWK) and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness Inc. Sincere appreciation is expressed to Ms Alma Maldonado for her technical contributions and performance of many of the experiments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alm A, Bill A. Ocular and optic nerve blood flow at normal and increased intraocular pressures in monkeys (macaca irus): a study with radioactively labeled microspheres including flow determinations in brain and some other tissues. Exp Eye Res. 1973;15:15–29. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(73)90185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila MY, Stone RA, Civan MM. A(1)-, A(2A)- and A(3)-subtype adenosine receptors modulate intraocular pressure in the mouse. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:241–245. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barany E. A mathematical formulation of intraocular pressure as dependent on secretion, ultrafiltration, bulk outflow, and osmotic reabsorption of fluid. Invest Ophthalmol. 1963;2:584–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berne RM. The role of adenosine in the regulation of coronary blood flow. Circ Res. 1980;47:807–813. doi: 10.1161/01.res.47.6.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bill A. A method to determine osmotically effective albumin and gammaglobulin concentrations in tissue fluids, its application to the uvea and a note on the effects of capillary “leaks” on tissue fluid dynamics. Acta Physiol Scand. 1968a;73:511–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201x.1968.tb10890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bill A. Capillary permeability to and extravascular dynamics of myoglobin, albumin and gammaglobulin in the uvea. Acta Physiol Scand. 1968b;73:204–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1968.tb04097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bill A. Effects of atropine on aqueous humor dynamics in the vervet monkey (Cercopithecus ethiops) Exp Eye Res. 1969;8:284–291. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(69)80040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bill A. The effect of changes in arterial blood pressure on the rate of aqueous humour formation in a primate (Cercopithecus ethiops) Ophthalmic Res. 1970;1:193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Bill A. Ocular circulation. In: Moses R, editor. Adler’s Physiology of the Eye: clinical applications. C.V. Mosby Co; St Louis: 1981. pp. 184–203. [Google Scholar]

- Bill A. Circulation in the eye. In: Renkin EM, Michel CC, editors. The Microcirculation, Part 2, Handbook of Physiology. Section 2. American Physiological Society; Bethesda: 1984. pp. 1001–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker RF. Computer-assisted instruction of current concepts in aqueous humor dynamics. Am J Ophth. 1976;82:59–63. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(76)90665-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker RF. Flow of aqueous humor in humans. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:3145–3166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147(Suppl 1):S172–181. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camras CB, Bito LZ. The pathophysiological effects of nitrogen mustard on the rabbit eye. II. The inhibition of the initial hypertensive phase by capsaicin and the apparent role of substance P. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1980;19:423–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosson CE. Intraocular pressure responses to the adenosine agonist cyclohexyladenosine: evidence for a dual mechanism of action. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1837–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinslage S, Mclaren J, Brubaker R. Intraocular pressure in rabbits by telemetry II: effects of animal handling and drugs. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:2485–2489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry D, Thomas L, Greenfield J. Flow in collapsible tubes. Basic Hemodynamics and Its Role in Disease Processes. 1980:405–423. [Google Scholar]

- Funk R, Rohen JW. Scanning electron microscopic study on the vasculature of the human anterior eye segment, especially with respect to the ciliary processes. Exp Eye Res. 1990;51:651–661. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(90)90049-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabelt BT, Kiland JA, Tian B, Kaufman PL. Aqueous humor: secretion and dynamics. In: Tasman W, Jaeger EA, editors. Duane’s Clinical Ophthalmology, vol. Foundation. Vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gallin-Cohen PF, Podos SM, Yablonski ME. Oxygen lowers intraocular pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1980;19:43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Lutjen-Drecoll E, Prestele H, Rohen JW. Structural differences between regions of the ciliary body in primates. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1977;16:912–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasko G, Sitkovsky MV, Szabo C. Immunomodulatory and neuroprotective effects of inosine. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L, Perry MA, Granger DN. Autoregulation of gastric blood flow and oxygen uptake. Am J Physiol. 1981;241:G143–G149. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1981.241.2.G143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R, Maurice D. New methods of measuring the rate of aqueous flow in man with fluorescein. Exp Eye Res. 1966;5:208–220. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(66)80009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel J. Physiology of the intraocular pressure. In: Feher J, editor. Pathophysiology of the Eye: Glaucoma. Vol. 4. Akademiai Kiado; Budapest: 1998. pp. 109–144. [Google Scholar]

- Kiel JW, Shepherd AP. Autoregulation of Choroidal Blood Flow in the Rabbit. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:2399–2410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel JW, Van Heuven WAJ. Ocular Perfusion Pressure and Choroidal Blood Flow in the Rabbit. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:579–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel JW. Modulation of choroidal autoregulation in the rabbit. Exp Eye Res. 1999;69:413–429. doi: 10.1006/exer.1999.0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel JW, Reitsamer HA, Walker JS, Kiel FW. Effects of nitric oxide synthase inhibition on ciliary blood flow, aqueous production and intraocular pressure. Exp Eye Res. 2001;73:355–364. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel JW, Reitsamer HA. Paradoxical effect of phentolamine on aqueous flow in the rabbit. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2007;23:21–26. doi: 10.1089/jop.2006.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel JW, Reitsamer HA. Ciliary blood flow and its role in aqueous humor formation. In: Dart DA, Besharse JC, Dana R, editors. Encyclopedia of the Eye. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Krupin T, Feitl M, Roshe R, Lee S, Becker B. Halothane anesthesia and aqueous humor dynamics in laboratory animals. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1980;19:518–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RS, Brubaker RF. Isoproterenol stimulates aqueous flow in humans with Horner’s syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1988;29:621–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linner E. A method for determining the rate of plasma flow through the secretory part of the ciliary body. Acta Physiol Scand. 1950;22:83–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1951.tb00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linner E. Ascorbic acid as a test substance for measuring relative changes in the rate of plasma flow through the ciliary processes. Acta Physiol Scand. 1952;26:57–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1952.tb00891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsenmeier RA, Yancey CM. Improved fabrication of double-barreled recessed cathode O2 microelectrodes. J Appl Physiol. 1987;63:2554–2557. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.6.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutjen-Drecoll E, Rohen JW. Anatomy of aqueous humor formation and drainage. In: Kaufman PL, Mittag TW, editors. Textbook of Ophthalmology. Mosby; London: 1994. pp. 1.1–1.16. [Google Scholar]

- Maepea O. Pressures in the anterior ciliary arteries, choroidal veins and choriocapillaris. Exp Eye Res. 1992;54:731–736. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(92)90028-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maus T, Young W, Brubaker R. Aqueous flow in humans after adrenalectomy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:3325–3331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mclaren J, Brubaker R, Fitzsimon J. Continuous measurement of intraocular pressure in rabbits by telemetry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:966–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison JC, Defrank MP, Van Buskirk EM. Comparative microvascular anatomy of mammalian ciliary processes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987;28:1325–1340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses R. Intraocular Pressure. In: Moses R, editor. Adler’s Physiology of the Eye: clinical application. C.V. Mosby Co; St Louis: 1981. pp. 227–254. [Google Scholar]

- Moses R. Intraocular Pressure. In: Moses R, Hart W, editors. Adler’s Physiology of the Eye: clinical application. C.V. Mosby Co; St Louis: 1987. pp. 223–245. [Google Scholar]

- Moses RA. Hydrodynamic model eye. Ophthalmologica. 1963;146:137–142. doi: 10.1159/000304511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld AH, Jampol LM, Sears ML. Aspirin prevents the disruption of the blood-aqueous barrier in the rabbit eye. Nature. 1972;238:158–159. doi: 10.1038/238158a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson S, Starling E. On the mechanical factors which determine the output of the ventricles. J Physiol. 1914;48:357–379. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1914.sp001669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry M, Bulkley G, Kvietys P, Granger D. Regulation of oxygen uptake in resting and pentagastrin-stimulated canine stomach. Am J Physiol. 1982a;242:G565–G569. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1982.242.6.G565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry M, Murphree D, Granger D. Oxygen uptake as a determinant of gastric blood flow autoregulation. Digest Dis Sci. 1982b;27:675–679. doi: 10.1007/BF01393761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry M, Haedicke G, Bulkley G, Kvietys P, Granger D. Relationship between acid secretion and blood flow in the canine stomach: role of oxygen consumption. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:413–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitsamer HA, Kiel JW. Effects of dopamine on ciliary blood flow, aqueous production, and intraocular pressure in rabbits. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002a;43:2697–2703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitsamer HA, Kiel JW. A rabbit model to study orbital venous pressure, intraocular pressure, and ocular hemodynamics simultaneously. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002b;43:3728–3734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitsamer HA, Kiel JW. Relationship between ciliary blood flow and aqueous production in rabbits. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3967–3971. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitsamer HA, Posey M, Kiel JW. Effects of a topical alpha2 adrenergic agonist on ciliary blood flow and aqueous production in rabbits. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:405–415. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitsamer HA, Bogner B, Tockner B, Kiel JW. Effects of dorzolamide on choroidal blood flow, ciliary blood flow, and aqueous production in rabbits. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2301–2307. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohen J, Funk R. Vasculature of the anterior eye segment. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 1994;13:653–685. [Google Scholar]

- Rohen JW. Scanning electron microscopic studies of the zonular apparatus in human and monkey eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1979;18:133–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell C, Debon C, Percicot C. Measurement of intraocular pressure by telemetry in conscious, unrestrained rabbits. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:958–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears M. The aqueous. In: Mose R, editor. Adler’s Physiology of the Eye: clinical application. C.V. Mosby Co; St Louis: 1981. pp. 204–226. [Google Scholar]

- Sears ML. Miosis and intraocular pressure changes during manometry. A.M.A. Arch Ophthal. 1960;63:159–166. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1960.00950020709014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd AP, Öberg PA. Laser-Doppler Blood Flowmetry. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Norwell, MA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Shui YB, Fu JJ, Garcia C, Dattilo LK, Rajagopal R, Mcmillan S, Mak G, Holekamp NM, Lewis A, Beebe DC. Oxygen distribution in the rabbit eye and oxygen consumption by the lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1571–1580. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topper JE, Mclaren J, Brubaker RF. Measurement of aqueous humor flow with scanning ocular fluorophotometers. Cur Eye Res. 1984;3:1391–1395. doi: 10.3109/02713688409000834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentworth W, Brubaker R. Aqueous humor dynamics in a series of patients with third neuron Horner’s syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981;92:407–415. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(81)90533-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yablonski ME, Gallin P, Shapiro D. Effect of oxygen on aqueous humor dynamics in rabbits. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985;26:1781–1784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamora D, Kiel J. Episcleral Venous Pressure Responses to Topical Nitroprusside and N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1614–1620. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]