Abstract

Environmental enrichment (EE) introduced during abstinence from cocaine self-administration is protective in reducing cue-elicited incentive motivation for cocaine in rats. This study examined neural activation associated with this protective effect of EE using Fos protein expression as a marker. Rats were trained to press a lever reinforced by cocaine (0.75 mg/kg/0.1 ml infusion) and light and tone cues across 15 consecutive days during which they were all housed in isolated conditions (IC). Rats were then assigned to either remain in IC, or to live in pair-housed conditions (PC) or EE for 30 days of forced abstinence from cocaine. Subsequently, cocaine-seeking behavior (lever presses without cocaine reinforcement) elicited by response-contingent cue presentations was assessed for 90 min, after which the rats' brains were immediately harvested for Fos protein immunohistochemistry. EE attenuated, whereas IC enhanced, cue-elicited cocaine-seeking behavior relative to PC. Also, within the prelimbic and orbitofrontal cortices and basolateral amygdala, IC enhanced, whereas EE reduced, Fos expression relative to PC. Furthermore, EE attenuated Fos expression in the infralimbic and anterior cingulate cortices, the nucleus accumbens (core and shell), bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and ventral tegmental area, evident as a reduction relative to both PC and IC. In contrast, IC enhanced Fos expression in the dorsal caudate putamen, substantia nigra, and central amygdala, evident as an increase relative to both PC and EE. These results suggest that EE blunts neural activation throughout the mesocorticolimbic circuitry involved in cue-elicited incentive motivation for cocaine, whereas IC enhances activation primarily within the nigrostriatal dopamine pathway. These findings have important implications for understanding and treating drug-conditioned craving in humans.

Keywords: Environmental enrichment, immediate early gene, cocaine cues, incentive motivation, neurocircuitry, craving

1. Introduction

A number of successful treatment regimens have been prescribed for alcohol, opioid, and tobacco dependence, yet little progress has been made in developing FDA approved medications for cocaine dependence (de Lima et al., 2002; Sofuoglu and Kosten, 2004; O'Brien, 2005). A particularly difficult aspect of cocaine addiction is the high rate of relapse that occurs even following prolonged periods of abstinence (Dackis and O'Brien, 2001). Craving often contributes to relapse and can be triggered by exposure to cues previously associated with cocaine use (Gawin and Kleber, 1986; McLellan et al., 2000). This can be modeled in animals by examining cocaine-seeking behavior, which is operationally defined as operant responses previously reinforced by cocaine that are performed in the absence of cocaine reinforcement (de Wit and Stewart, 1981). Cocaine-seeking behavior measured in the environment where cocaine had been self-administered along with presentation of discrete cues that had been paired previously with cocaine infusions is thought to reflect, in part, the incentive motivational effects of the contextual and discrete drug-paired cues (Markou et al., 1993).

A potential behavioral intervention for reducing drug craving, and presumably incentive motivation, is the use of environmental enrichment (EE). Until recently, the majority of preclinical drug abuse studies have examined EE and other housing/exercise-induced manipulations with a focus on protective effects against susceptibility to drug reward and reinforcement when introduced during rearing or immediately prior to drug exposure (Howes et al., 2000; Bardo et al., 2001; Green et al., 2002; Stairs et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2008; Solinas et al., 2009). However, Solinas et al. (2008) demonstrated that EE introduced only after a cocaine-conditioned place preference (CPP) acquisition phase, during which mice were housed under standard living conditions, attenuates subsequent expression and cocaine-primed reinstatement of cocaine-CPP. In parallel, Grimm et al. (2008) reported that the use of this EE intervention-like strategy attenuates sucrose-seeking behavior. Finally, work from our laboratory, and that of Solinas and colleagues, has demonstrated that EE introduced during forced abstinence from cocaine self-administration attenuates subsequent contextual and cue-induced cocaine-seeking behavior (Chauvet et al., 2009; Thiel et al., 2009; Thiel et al., in press). Taken together, the findings suggest that EE may be an effective intervention treatment strategy. Importantly, components of EE, such as exercise, access to multiple non-drug reinforcers, and social reinforcement, have been shown to yield some success as treatment approaches aimed at drug addiction in humans, and in parallel reduce drug-seeking behavior in animals, thus lending support for the validity of the animal model (Kearns and Weiss, 2007; Smith et al., 2008; Carroll et al., 2009; Zlebnik et al., 2010).

The robust effects of EE on cue-elicited cocaine-seeking behavior begs the question of which neural mechanisms are involved, and a good starting point for addressing this question is to examine Fos protein expression. This measure has been used extensively as a marker of functional activation of a neuron in response to external stimuli (Herrera and Robertson, 1996; Harlan and Garcia, 1998). Given that Fos is a transcription factor, it stands to reason that its activation may mediate some of the enduring neuronal changes that underlie the incentive motivational effects of cocaine-paired stimuli. Indeed, Fos protein expression is elicited by exposure to a cocaine-associated context (Brown et al., 1992; Crawford et al., 1995; Hotsenpiller et al., 2002; Hamlin et al., 2008), cocaine-associated discrete cues (Neisewander et al., 2000; Zavala et al., 2007; Zavala et al., 2008; Kufahl et al., 2009), as well as discriminative stimulus cues that signal the availability of cocaine (Ciccocioppo et al., 2001).

In the present study, we used Fos protein expression to examine the neural circuitry involved in the protective effects of EE against cue-elicited cocaine-seeking behavior. Rats previously trained to self-administer cocaine while living under isolated conditions (IC) were subsequently assigned to live in either IC, pair-housed conditions (PC), or EE during a period of forced abstinence and were then tested for reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior by response-contingent cue presentations. We hypothesized that an EE-induced reduction of cue-elicited cocaine-seeking behavior relative to IC and PC controls would be accompanied by attenuation of functional activation within cortical, striatal, and limbic circuitry components that have been implicated in the incentive motivation for cocaine elicited by drug-associated cues.

2. Method

2.1. Animals and surgery

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 225-250 g upon arrival were housed under IC (i.e., 1 rat/cage, 21.6 × 45.7 × 17.8 cm) with food and water available ad libitum in a temperature-controlled colony with a 12-h reverse light:dark cycle (lights off at 7:00 a.m.). Care and housing were in adherence to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (1996). Rats were acclimated to handling for 5 days prior to surgically implanting intravenous (i.v.) catheters under 2-3% isoflurane anesthesia using procedures described previously (Zavala et al., 2007). Following surgery, animals were returned to their home cage for at least 5 days recovery prior to the start of self-administration training. In order to prevent infection and maintain patency, catheters were flushed daily with 0.1 ml bacteriostatic saline containing heparin sodium (70 U/ml; APP Pharmaceuticals, Schaumburg, IL), Abbokinase (20 mg/ml; ImaRx Therapeutics, Tucson, AZ), and Timentin (66.7 mg/ml; GlaxoSmithKlinr, Research Triangle Park, NC). Proper catheter function was tested periodically by administering 0.05 ml methohexital sodium (16.7 mg/ml; JHP Pharmaceuticals, Rochester, MI), a dose that produces brief anesthetic effects only when administered i.v.

2.2. Cocaine self-administration

Rats underwent 15 days of cocaine self-administration training for 3 h/day during their dark cycle while housed in IC. Initially, sessions began under an fixed ratio 1 (FR1) schedule of reinforcement and progressed to a variable ratio 5 (VR5) schedule based on individual performance, with the latter in effect exclusively during at least the last 5 sessions. Schedule completions on a designated lever (i.e., active lever) located on the left side of the chamber resulted in simultaneous presentation of a tone (500 Hz, 10 db above background), cue light above the lever, and house light, and were followed 1 s later by a cocaine infusion (0.75 mg/kg/0.1 ml, IV). Upon completion of the 6-s infusion, the cue light and tone ceased, but the house light remained on for an additional 20-s timeout. Responses on another lever (i.e., inactive lever, located on the right side of the chamber) produced no consequences. Rats were restricted to 16 g of food/day beginning 2 days before training to facilitate exploration. A rat remained food-restricted until a criterion of ≥21 infusions/3 h was achieved on 2 consecutive days, after which food was available ad libitum in the home cage throughout the remainder of the experiment. All rats had reached this criterion by the 10th session. Two rats were omitted from data analysis within the study due to catheter failure during self-administration; however, they were used to even out the living conditions described below.

2.3. Forced abstinence

The day after completing self-administration, rats were assigned to one of three housing conditions during abstinence, counterbalanced for previous cocaine intake: Isolated Conditions (IC; n=9), Pair-housed Conditions (PC; n=9), or an Enriched Environment (EE; n=9). The PC was identical to the IC except that there were 2 rats/cage. The EE group lived in large plastic tubs (74 × 91 × 36 cm) that housed 5 rats and contained bedding, nesting material, 3 PVC pipes, 2 running wheels, 2 water bottles, 2 food dishes, and 2 small plastic toys. Toys were continually changed 3 times/week to maintain novelty. Two rats were omitted from the analyses due to catheter failure but were used for the living conditions during abstinence.

2.4. Cue test

On day 21 of abstinence, rats were tested for cocaine-seeking behavior following a cocaine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) priming injection within the self-administration chamber and the results from this test have been reported previously (Thiel et al., 2009). Following this test, all rats were placed back into their assigned living conditions for an additional 9 days of abstinence. Subsequently (i.e., on Day 30 of abstinence), the rats were placed back into the self-administration chambers and were tested for cocaine-seeking behavior (i.e., active lever presses without cocaine reinforcement) for 90 min with response-contingent cue presentations available (i.e., the stimulus complex previously paired with cocaine infusions). To begin the test session, a non-contingent programmed cue presentation occurred shortly after the animals were placed into the chambers, which was the first time since the self-administration phase that rats were exposed to these cues. Thereafter, the cues were presented on an FR1 schedule of reinforcement as this schedule has previously been demonstrated to yield high response rates from which to detect group differences during testing for cocaine-seeking behavior (Acosta et al., 2008).

2.5. Tissue preparation

Immediately after testing, rats were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (65 mg/kg, i.p.) and perfused transcardially with 300 ml of ice-cold 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4, followed by 300 ml of ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4. The brains were removed, postfixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde, and then transferred to 15% sucrose for 24 h and then 30% sucrose for an additional 24 h while continuously being stored at 4°C. Coronal sections (40 μm) were collected using a freezing microtome at levels corresponding to +3.2, +1.6, +0.0, -2.56, -5.6 mm relative to bregma (Paxinos and Watson, 1998). The tissue sections were then frozen and stored at 4°C in a cryoprotectant solution comprised of 0.02 M PBS (pH = 7.2), 30% sucrose, 10% polyvinyl pyrrolidone, and 30% ethylene glycol.

2.6. Fos protein immunohistochemistry

Tissue sections were first washed in 0.1 M PBS (6 × 10 min) to remove the cryoprotectant. Sections were then incubated in 0.3% H2O2 for 30 min and rinsed with 0.1 M PBS (3 × 10 min), followed by incubation in 0.1 M PBS containing 5% normal goat serum (NGS) (Vector Laboratories) and 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma) for 1 h. Sections were then incubated for 48 h at 4°C in 0.1 M PBS containing anti-Fos rabbit polyclonal antibody (SC-52; 1:2,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1% NGS, and then rinsed in 0.1 M PBS (3 × 10 min). Sections were then incubated in 0.1 M PBS containing biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:500; Vector Laboratories) and 1% NGS for 1 h, and then rinsed in 0.1 M PBS (3 × 10 min). Subsequently, horseradish peroxidase activity was visualized with nickel diaminobenzidine and glucose oxidase reaction as described in Dielenberg et al. (2001). This reaction was terminated after 10 min by rinsing the tissue in 0.1 M PBS (3 × 10 min). Sections were then mounted onto gelatin-coated slides, dried, and dehydrated before cover slipping.

2.7. Fos immunoreactivity analysis

Figure 1 illustrates the specific subregions analyzed. Sections taken at +3.2 mm contained the prelimbic (PrL), infralimbic (IL), and orbitofrontal (OFC) cortices; sections taken at +1.6 mm contained the Cg2 region of the anterior cingulated cortex, nucleus accumbens (NAc) core (NAcC) and shell (NAcS), and the dorsal caudate putamen (dCPu); sections taken at +0.0 mm contained the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST); sections taken at -2.56 mm contained the basolateral amygdala (BlA), central amygdala (CeA), and somatosensory cortex (SS); sections taken at -5.6 mm contained the VTA, substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and pars reticulata (SNr), ventral subiculum (vSub) and the dorsal CA1, CA3, and dentate gyrus (DG) subregions of the hippocampus. Quantification of Fos immunoreactivity was examined using a Nikon Eclipse E600 (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, USA) microscope set at 20× magnification and counted by an observer blind to treatment conditions using the Image Tool software package (Version 3.0, University of Texas Health Sciences Center, San Antonio, TX). For all regions, the sample area counted was 0.26 mm2 and there were a total of 6 sample areas counted for each subject (i.e., 1 sample area/2 hemispheres/3 sections). The sections mounted onto each slide for each rat were 160 μm apart along the rostral-caudal extent of each region analyzed in order to avoid double counting of Fos-labeled cells. Care was taken to ensure that the sections for each subject that were labeled came from the same anatomical level within each plane. Fos immunoreactivity was identified as a blue-black oval-shaped nucleus distinguishable from background (see Figure 2). The counts from all 6 sample areas from a particular region were averaged to provide a mean number of immunoreactivity cells per sample area.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of coronal sections of the rat brain taken at +3.2, +1.6, -0.26, -2.56, and -5.6 mm from Bregma (Paxinos and Watson, 1998). Numbers in the sections represent the regions analyzed for Fos as follows: (1) prelimbic cortex (PrL); (2) infralimbic cortex (IL); (3) orbital frontal cortex (OFC); (4) Cg2 region of the anterior cingulate cortex (Cg2); (5) dorsal caudate-putamen (dCPu); (6) nucleus accumbens core (NAcC); (7) nucleus accumbens shell (NAcS); (8) bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST); (9) somatosensory cortex (SS); (10) basolateral amygdala (BlA); (11) central amygdala (CeA); (12) ventral tegmental area (VTA); (13) CA3 region of the hippocampus (CA3); (14) CA1 region of the hippocampus (CA1); (15) dentate gyrus (DG); (16) substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc); (17) substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr); (18) ventral subiculum (vSub).

Figure 2.

Representative photomicrographs taken from coronal sections (top 3 rows) at 20× magnification in the basolateral amygdala (BlA; column 1), infralimbic cortex (IL; column 2) and dorsal caudate putamen (dCPu; column 3) demonstrating Fos protein labeling (black arrows) in representative rats from the isolated condition (IC; row 1), pair-housed condition (PC; row 2), and environmental enrichment (EE; row 3). Scale bar on the BlA/EE photomicrograph is equal to 100 μm. Also included along the bottom row are photomicrographs taken from coronal sections of EE rats at 4× magnification demonstrating the 0.26 mm2 sampling areas. White arrows refer to the corpus callosum (external capsule extension on BlA picture) for reference.

2.8. Data analysis

Separate one-way ANOVAs with Living Condition as a between subjects factor were used to analyze active and inactive lever presses on test day, as well as to analyze Fos protein expression within each region of interest. Post hoc Tukey HSD tests (p< 0.05) were used for subsequent pair-wise comparisons. Additionally, the correlation between cocaine-seeking behavior and Fos expression within each region of interest was calculated using Pearson's product-moment correlation. In general, patterns of Fos expression within each region corresponded with the living condition-induced differences in cocaine-seeking behavior, thus resulting in strong positive correlations. Therefore, to further gauge the extent to which the act of lever pressing correlated with Fos expression, correlations between cocaine-seeking behavior and Fos expression within each region of interest were also conducted separately for the IC, PC, and EE groups.

3. Results

3.1. Cocaine intake

Group assignment was counterbalanced such that cocaine intake, as well as total active lever presses, was equated across the IC, PC, and EE groups. These data have been published previously (Experiment 2 in Thiel et al., 2009).

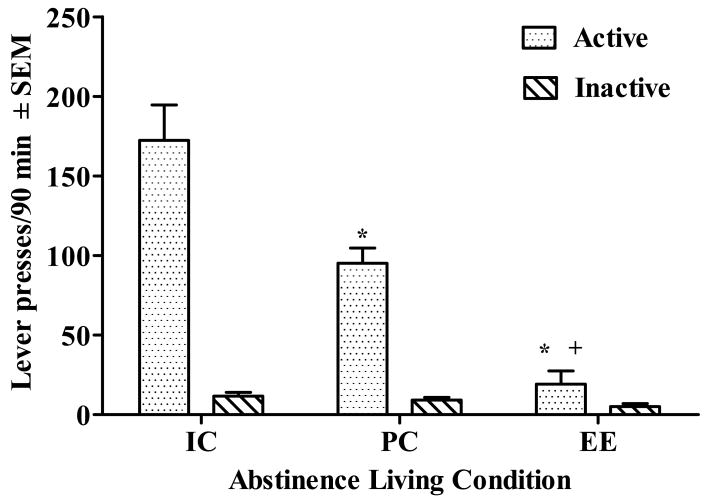

3.2. Cue-induced cocaine-seeking behavior

Total cocaine-seeking behavior, as well as inactive lever pressing, during the 90-min cue test phase is illustrated in Figure 3. There was a significant effect of Living Condition (F(2,24) = 26.83, p< 0.001) for active lever presses during this phase. IC exhibited more cocaine-seeking behavior than both PC and EE (p<.05, Tukey's HSD; Fig. 3). PC also exhibited more cocaine-seeking behavior than EE (p<.05, Tukey's HSD; Fig. 3). There were no group differences in inactive lever pressing.

Figure 3.

Cue-elicited cocaine-seeking behavior (i.e., active lever responses ± SEM, dotted bars) and inactive lever responses ± SEM (diagonal lined bars) totaled across the 90-min test phase for rats housed under isolated conditions (IC), pair-housed conditions (PC), or environmental enrichment (EE) during forced abstinence. After the 30-d forced abstinence period, rats were placed back into their self-administration chambers and immediately given a non-contingent programmed presentation of the light and tone cue complex previously associated with cocaine infusions. Subsequently, active lever presses response-contingently activated this cue complex on an FR1 schedule. Asterisk (*) represents a difference from IC (p<0.05, Tukey). Cross (+) represents a difference from PC (p<0.05, Tukey).

3.3. Fos protein immunoreactivity

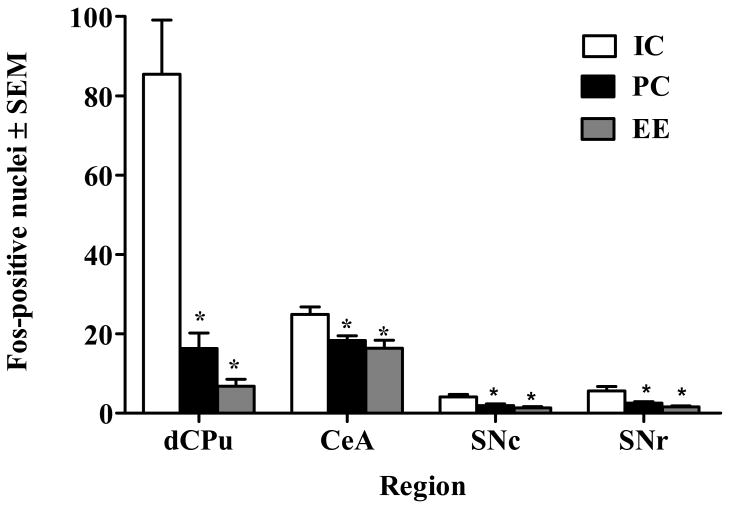

Analysis of Fos protein revealed 3 general patterns of expression. In the first pattern, significant Living Condition effects were observed in the PrL (F(2,24) = 74.45, p< 0.001), OFC (F(2,24) = 30.44, p< 0.001), and BlA (F(2,24) = 56.89, p< 0.001); subsequent post-hoc tests indicated that IC resulted in enhanced, whereas EE resulted in decreased, Fos expression relative to PC (p<.05, Tukey's HSD; Figure 4). This pattern suggests that IC and EE produced oppositional influences on functional activation by cocaine cues in these regions. In the second pattern, significant Living Condition effects were observed in the IL (F(2,24) = 23.27, p< 0.001), Cg2 (F(2,24) = 14.38, p< 0.001), NAcC (F(2,24) = 27.15, p< 0.001), NAcS (F(2,24) = 17.68, p< 0.001), BNST (F(2,24) = 7.53, p< 0.01), CA1 (F(2,24) = 7.53, p< 0.01), and VTA (F(2,24) = 9.84, p< 0.001); subsequent post-hoc tests indicated that EE resulted in decreased Fos expression relative to both IC and PC (p<.05, Tukey's HSD; Figure 5). This pattern suggests that EE blunted functional activation by cocaine cues in these regions. In the third pattern, significant Living Condition effects were observed in the dCPu (F(2,24) = 26.88, p< 0.001), SNc (F(2,24) = 5.85, p< 0.01), SNr (F(2,24) = 6.75, p< 0.01), and CeA (F(2,24) = 6.59, p< 0.01); subsequent post-hoc tests indicated that IC resulted in enhanced Fos expression relative to both EE and PC (p<.05, Tukey's HSD; Figure 6). This pattern suggests that IC enhanced functional activation by cocaine cues in these regions. No group differences in Fos expression were observed in the vSub, DG, CA3, or SS (Figure 7).

Figure 4.

Number of Fos-positive nuclei/0.26 mm2 ± SEM in regions where rats housed under isolated conditions (IC) during forced abstinence exhibited enhanced Fos expression, whereas those housed under environmental enrichment (EE) exhibited decreased Fos expression relative to rats in pair-housed conditions (PC) during the 90-min cue-elicited cocaine-seeking test described in the caption of Figure 3. Asterisk (*) represents a difference from IC (p<0.05, Tukey). Cross (+) represents a difference from PC (p<0.05, Tukey).

Figure 5.

Number of Fos-positive nuclei/0.26 mm2 ± SEM in regions where rats housed under environmental enrichment (EE) during forced abstinence exhibited decreased Fos expression relative to rats in pair-housed conditions (PC) and isolated conditions (IC) during the 90-min cue-elicited cocaine-seeking test described in the caption of Figure 3. Asterisk (*) represents a difference from IC (p<0.05, Tukey). Cross (+) represents a difference from PC (p<0.05, Tukey).

Figure 6.

Number of Fos-positive nuclei/0.26 mm2 ± SEM in regions where rats housed under isolated conditions (IC) during forced abstinence exhibited enhanced Fos expression relative to rats in pair-housed conditions (PC) and environmental enrichment (EE) during the 90-min cue-elicited cocaine-seeking test described in the caption of Figure 3. Asterisk (*) represents a difference from IC (p<0.05, Tukey).

Figure 7.

Number of Fos-positive nuclei/0.26 mm2 ± SEM in regions where there were no regional differences in Fos expression in rats housed under isolated conditions (IC), pair-housed conditions (PC), or environmental enrichment (EE) mediated during the 90-min cue-elicited cocaine-seeking test described in the caption of Figure 3.

In general, for all brain regions in which there were group differences in Fos expression, the degree of Fos expression strongly correlated with overall cocaine-seeking behavior (r2 ranging from +0.44 - +0.88, p<.05). However, when IC, PC, and EE were examined separately, there were no significant correlations between cocaine-seeking behavior and Fos expression within any brain region for any of these individual groups, suggesting increased Fos was not simply the result of increased lever responding as reported previously (Neisewander et al., 2000).

4. Discussion

Cocaine-seeking behavior was most robust in rats under IC and was attenuated in rats under EE, which is consistent with previous findings (Chauvet et al., 2009; Thiel et al., 2009). The reduced cocaine-seeking behavior observed with PC relative to IC may reflect attenuation of stress-induced enhancement of cocaine-seeking behavior due to chronic isolation. Indeed, isolation is a stressor in adult rats (Hall, 1998), and stressors such as footshock have been shown to enhance cue reinstatement (Buffalari and See, 2009). However, it is important to note that all rats were housed in IC upon arrival and throughout self-administration training; therefore, while isolation stress may have contributed to cocaine-seeking behavior in IC abstinent rats, isolation itself was not introduced as an acute stressor. Given that social housing is only one aspect of EE, and that the EE group exhibited even less cocaine-seeking behavior than the PC group, the findings suggest that individual components of enrichment likely provide additive protective effects, as suggested previously (van Praag et al., 2000).

The focal novel finding in the present study is that EE attenuated cue-elicited Fos protein expression across a number of cortical, striatal, and limbic structures that have been implicated in cocaine-seeking behavior (Koob and Le Moal, 2001; Shalev et al., 2002; Vanderschuren et al., 2005; Feltenstein and See, 2008; Kalivas, 2008). Our laboratory has previously demonstrated robust cue-elicited Fos expression throughout the majority of these structures with a notable exception being the BNST, which we had not examined previously (Zavala et al., 2007; Zavala et al., 2008; Kufahl et al., 2009). Importantly, the cue-elicited Fos expression is not likely due to the act of lever pressing per se as we have previously demonstrated similar effects even without levers available (Neisewander et al., 2000). Furthermore, non-conditioned saline-yoked controls in our previous studies failed to exhibit an increase in Fos upon exposure to the cues, and no group differences were observed in the SS in the present study, suggesting that sensory processing did not likely alter Fos expression. Differences in Fos expression due to living conditions per se (i.e., regardless of a cue test) are also unlikely given a recent study by Solinas and colleagues which demonstrated no differences in saline-primed Fos protein expression throughout the PFC, accumbens, amygdala, and VTA between saline-conditioned mice that lived in either standard housing or EE for 10 days (Solinas et al., 2008). We suggest that the EE attenuation of Fos expression in the present study was likely related to processes involved in cue-evoked incentive motivation for cocaine.

Overall, examination of living condition effects on cue-elicited Fos expression revealed three interesting patterns of change across groups. In the first pattern, IC during forced abstinence resulted in enhanced, whereas EE resulted in decreased, Fos expression in the PrL, OFC, and BlA (Figure 4). Notably, this pattern of Fos expression corresponds with the pattern of cocaine-seeking behavior across the groups (Figure 3), suggesting that these regions may play a particularly important role in the behavior. The OFC contains extensive reciprocal connections with the medial PFC and the BlA (Cavada et al., 2000; Krawczyk, 2002), with connections to the latter playing an integral role in regulating goal-directed behavior and modifying the incentive value of conditioned reinforcers (Schoenbaum et al., 2003; Schoenbaum and Setlow, 2005; Stalnaker et al., 2007). Furthermore, functional connectivity between the BlA and the PrL is responsible for integrating and processing emotionally relevant stimuli (Laviolette et al., 2005). A history of cocaine exposure may alter signaling within this BlA-PFC pathway that eventually manifests as maladaptive emotional responding and impulsive drug-seeking behavior in response to drug-associated stimuli (Winstanley, 2007). Indeed, cocaine abusers exhibit blunted OFC activity under baseline resting conditions and exaggerated OFC activity in response to cocaine-paired cues in a manner that correlates with self-report of craving (Volkow and Fowler, 2000). EE, and to a lesser extent PC, may restore plasticity and functioning within the OFC, PrL, and BlA in such a way that exposure to drug-related cues no longer elicits robust cocaine-seeking behavior. The decreased Fos expression observed in these regions under PC relative to IC may specifically highlight socially-mediated blunting of cue-induced neural processing in corticolimbic circuitry. In contrast, IC during withdrawal may exacerbate neuroadaptations within these regions that lead to both impulsive and compulsive drug-seeking in the presence of drug-related stimuli, whereas PC may reduce and EE may even reverse these changes, resulting in progressively less cue-elicited Fos expression.

The second pattern of Fos expression observed was that EE uniquely attenuated Fos expression throughout the IL, Cg2, NAc, BNST, CA1 and VTA relative to both IC and PC (Figure 5). Although this pattern does not correspond precisely with the behavior (i.e., no differences in Fos between IC and PC groups), it highlights additional regions in which EE blunts cue-elicited activation. The NAc receives glutamatergic projections from the PFC which are thought to mediate drug-seeking behavior (Kalivas and Volkow, 2005). The IL and anterior cingulate are also thought to process the incentive motivational effects of cocaine-associated stimuli (Neisewander et al., 2000; Ciccocioppo et al., 2001; Kufahl et al., 2009), as well as optimal reinforcement-guided choices based on reward value expectations (Rushworth et al., 2004; Kennerley et al., 2006), with the NAc additionally functioning as an integration center where limbic and cortical processing is transferred into goal-directed actions (Sesack and Grace, 2010). BNST activation stimulates dopaminergic cells within the VTA (Georges and Aston-Jones, 2001, 2002), which in turn has been implicated in mediating responses to drug-paired stimuli (Wise, 2009). All of these regions are part of the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system, which undergoes an array of cocaine-induced neuroplastic changes during abstinence that contribute to an enduring vulnerability to relapse (Thomas et al., 2008). For example, electrophysiology studies have demonstrated increased neuronal activity within the NAc throughout abstinence (Ghitza et al., 2003; Hollander and Carelli, 2007), and alterations in brain-derived neurotrophic factor have been observed within the PFC, NAc, and VTA (Lu et al., 2004; McGinty et al., 2010). Thus, attenuated cue-elicited Fos expression throughout this system may reflect a reversal or normalization of some of these neuroadaptations, which in turn may reduce motivation elicited by the cocaine-paired cues.

Interestingly, Green et al. (2010) recently demonstrated that enrichment decreases phosphorylated cAMP response element binding protein (pCREB) within the NAc, and that this correlates with an antidepressant behavioral phenotype. Given that Fos expression is regulated upstream by CREB phosphorylation, the attenuated Fos expression within the NAc of EE rats in the present study may also be indicative of an antidepressant effect, which in turn may be a possible mechanism by which EE attenuates cocaine-seeking behavior, as has been suggested by others (Chauvet et al., 2009).

The third pattern of Fos expression was that IC uniquely resulted in enhanced Fos within the dCPu, SNc, SNr, and CeA relative to both PC and EE (Figure 6). We suggest that this pattern reflects a reduction of nigrostriatal neuronal activation (i.e., the dopaminergic pathway projecting from the SNc to the CPu) associated with the potential isolation stress of IC. Stress cross-sensitizes with psychomotor stimulants, and relief from isolation stress may reduce sensitized responses of the nigrostriatal pathway. The CeA projects extensively to the SNc (Zahm, 2006) and has been heavily implicated in anxiety-related neuroadaptations during cocaine withdrawal (Koob, 2009; Erb, 2010) and stress-elicited cocaine-seeking behavior (Shaham et al., 2000; McFarland et al., 2004). Furthermore, the dorsal striatum (i.e., dCPu) plays a particularly important role in controlling cocaine-seeking behavior following periods of abstinence (Fuchs et al., 2006; See et al., 2007), and mediates the habitual nature of drug seeking/taking that largely characterizes addiction (Jog et al., 1999; Canales, 2005; Everitt and Robbins, 2005). It has been suggested that chronic cocaine use shifts neural activity from the ventral striatum to the dorsal striatum resulting in vulnerability to relapse (Everitt and Robbins, 2005; See et al., 2007). Based on the present pattern of activation, it is possible that social and environmental stimulation during abstinence may prevent this shift. This may partially explain the reduced cocaine-seeking behavior observed in PC and EE rats compared to IC rats. EE's additional reduction in cocaine-seeking behavior relative to PC may therefore be the result of reduced activation of cortical and ventral striatal structures (e.g., NAc) noted above.

In conclusion, EE strongly attenuated cue-elicited cocaine-seeking behavior following a month of forced abstinence from cocaine self-administration, whereas IC enhanced this behavior relative to PC. EE also reduced Fos expression relative to both IC and PC throughout mesocorticolimbic circuitry that is thought to be involved in processing the motivational value of drug-paired cues and making decisions to engage in cocaine-seeking behavior (Kalivas and Volkow, 2005). In addition, IC enhanced Fos expression relative to PC and EE within nigrostriatal dopamine circuitry that is thought to underlie the habitual nature of drug seeking (Volkow et al., 2006; Everitt et al., 2008), suggesting that IC increases subconscious, automatic control of drug seeking that is thought to contribute to relapse vulnerability (Tiffany and Carter, 1998). Taken together, it appears that both the mesocorticolimbic and nigrostriatal circuits are fully engaged by cocaine-paired cues in IC rats while both circuits are less engaged in EE rats. PC rats exhibit some cue-elicited mesocorticolimbic activation, but failed to exhibit nigrostriatal activation, which may partially explain why they demonstrate significantly greater cue-elicited cocaine-seeking behavior than EE rats, but significantly less of this behavior compared to IC rats. Although speculative, it is possible that EE, and to a lesser extent PC, may counter or reverse cocaine-induced neuroadaptations that occur within these circuits. EE has widespread effects on neural plasticity (Markham and Greenough, 2004; Stairs and Bardo, 2009), and it will be necessary to pinpoint the specific processes and mechanisms of its protective effects in future studies. This line of research may lead to novel intervention strategies for the treatment of psychomotor stimulant dependence.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants R01DA11064, R21DA023123, and F31DA023746 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of NIDA or the National Institutes of Health. The authors wish to thank Lara Pockros, Lindsey Robertson, and Ben Engelhardt for their expert technical assistance throughout various phases of the study.

List of abbreviations

- BlA

basolateral amygdala

- BNST

bed nucleus of the stria terminalis

- CeA

central amygdala

- CPP

conditioned place preference

- CREB

cAMP response element binding protein

- CRF

corticotropin releasing factor

- dCPu

dorsal caudate putamen

- DG

dentate gyrus

- EE

environmental enrichment

- FR

fixed ratio

- IC

isolated condition

- IL

infralimbic cortex

- i.p

intraperitoneal

- i.v

intravenous

- NAc

nucleus accumbens

- NAcC

nucleus accumbens core

- NAcS

nucleus accumbens shell

- NGS

normal goat serum

- OFC

orbtiofrontal cortex

- PC

pair-housed condition

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

- PrL

prelimbic cortex

- SNc

substantia nigra pars compacta

- SNr

substantia nigra pars reticulata

- SS

somatosensory cortex

- VR

variable ratio

- vSub

ventral subiculum

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Acosta JI, Thiel KJ, Sanabria F, Browning JR, Neisewander JL. Effects of schedule of reinforcement on cue-elicited reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19:129–136. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282f62c89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardo MT, Klebaur JE, Valone JM, Deaton C. Environmental enrichment decreases intravenous self-administration of amphetamine in female and male rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;155:278–284. doi: 10.1007/s002130100720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EE, Robertson GS, Fibiger HC. Evidence for conditional neuronal activation following exposure to a cocaine-paired environment: role of forebrain limbic structures. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4112–4121. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-10-04112.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffalari DM, See RE. Footshock stress potentiates cue-induced cocaine-seeking in an animal model of relapse. Physiol Behav. 2009;98:614–617. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canales JJ. Stimulant-induced adaptations in neostriatal matrix and striosome systems: transiting from instrumental responding to habitual behavior in drug addiction. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2005;83:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Anker JJ, Perry JL. Modeling risk factors for nicotine and other drug abuse in the preclinical laboratory. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104 1:S70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavada C, Company T, Tejedor J, Cruz-Rizzolo RJ, Reinoso-Suarez F. The anatomical connections of the macaque monkey orbitofrontal cortex. A review. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:220–242. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvet C, Lardeux V, Goldberg SR, Jaber M, Solinas M. Environmental enrichment reduces cocaine seeking and reinstatement induced by cues and stress but not by cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2767–2778. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccocioppo R, Sanna PP, Weiss F. Cocaine-predictive stimulus induces drug-seeking behavior and neural activation in limbic brain regions after multiple months of abstinence: reversal by D(1) antagonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1976–1981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford CA, McDougall SA, Bolanos CA, Hall S, Berger SP. The effects of the kappa agonist U-50,488 on cocaine-induced conditioned and unconditioned behaviors and Fos immunoreactivity. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;120:392–399. doi: 10.1007/BF02245810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dackis CA, O'Brien CP. Cocaine dependence: a disease of the brain's reward centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;21:111–117. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lima MS, de Oliveira Soares BG, Reisser AA, Farrell M. Pharmacological treatment of cocaine dependence: a systematic review. Addiction. 2002;97:931–949. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Stewart J. Reinstatement of cocaine-reinforced responding in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1981;75:134–143. doi: 10.1007/BF00432175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dielenberg RA, Hunt GE, McGregor IS. “When a rat smells a cat”: the distribution of Fos immunoreactivity in rat brain following exposure to a predatory odor. Neuroscience. 2001;104:1085–1097. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb S. Evaluation of the relationship between anxiety during withdrawal and stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34:798–807. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Belin D, Economidou D, Pelloux Y, Dalley JW, Robbins TW. Review. Neural mechanisms underlying the vulnerability to develop compulsive drug-seeking habits and addiction. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:3125–3135. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: from actions to habits to compulsion. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/nn1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltenstein MW, See RE. The neurocircuitry of addiction: an overview. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:261–274. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Branham RK, See RE. Different neural substrates mediate cocaine seeking after abstinence versus extinction training: a critical role for the dorsolateral caudate-putamen. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3584–3588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5146-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawin FH, Kleber HD. Abstinence symptomatology and psychiatric diagnosis in cocaine abusers. Clinical observations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:107–113. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800020013003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georges F, Aston-Jones G. Potent regulation of midbrain dopamine neurons by the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-j0003.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georges F, Aston-Jones G. Activation of ventral tegmental area cells by the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis: a novel excitatory amino acid input to midbrain dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5173–5187. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-05173.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghitza UE, Fabbricatore AT, Prokopenko V, Pawlak AP, West MO. Persistent cue-evoked activity of accumbens neurons after prolonged abstinence from self-administered cocaine. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7239–7245. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-19-07239.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green TA, Alibhai IN, Roybal CN, Winstanley CA, Theobald DE, Birnbaum SG, Graham AR, Unterberg S, Graham DL, Vialou V, Bass CE, Terwilliger EF, Bardo MT, Nestler EJ. Environmental enrichment produces a behavioral phenotype mediated by low cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding (CREB) activity in the nucleus accumbens. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green TA, Gehrke BJ, Bardo MT. Environmental enrichment decreases intravenous amphetamine self-administration in rats: dose-response functions for fixed- and progressive-ratio schedules. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;162:373–378. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1134-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm JW, Osincup D, Wells B, Manaois M, Fyall A, Buse C, Harkness JH. Environmental enrichment attenuates cue-induced reinstatement of sucrose seeking in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2008;19:777–785. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32831c3b18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall FS. Social deprivation of neonatal, adolescent, and adult rats has distinct neurochemical and behavioral consequences. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1998;12:129–162. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v12.i1-2.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin AS, Clemens KJ, McNally GP. Renewal of extinguished cocaine-seeking. Neuroscience. 2008;151:659–670. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlan RE, Garcia MM. Drugs of abuse and immediate-early genes in the forebrain. Mol Neurobiol. 1998;16:221–267. doi: 10.1007/BF02741385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera DG, Robertson HA. Activation of c-fos in the brain. Prog Neurobiol. 1996;50:83–107. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(96)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander JA, Carelli RM. Cocaine-associated stimuli increase cocaine seeking and activate accumbens core neurons after abstinence. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3535–3539. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3667-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotsenpiller G, Horak BT, Wolf ME. Dissociation of conditioned locomotion and Fos induction in response to stimuli formerly paired with cocaine. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:634–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes SR, Dalley JW, Morrison CH, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Leftward shift in the acquisition of cocaine self-administration in isolation-reared rats: relationship to extracellular levels of dopamine, serotonin and glutamate in the nucleus accumbens and amygdala-striatal FOS expression. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;151:55–63. doi: 10.1007/s002130000451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jog MS, Kubota Y, Connolly CI, Hillegaart V, Graybiel AM. Building neural representations of habits. Science. 1999;286:1745–1749. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW. Addiction as a pathology in prefrontal cortical regulation of corticostriatal habit circuitry. Neurotox Res. 2008;14:185–189. doi: 10.1007/BF03033809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Volkow ND. The neural basis of addiction: a pathology of motivation and choice. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1403–1413. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns DN, Weiss SJ. Contextual renewal of cocaine seeking in rats and its attenuation by the conditioned effects of an alternative reinforcer. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennerley SW, Walton ME, Behrens TE, Buckley MJ, Rushworth MF. Optimal decision making and the anterior cingulate cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:940–947. doi: 10.1038/nn1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Brain stress systems in the amygdala and addiction. Brain Res. 2009;1293:61–75. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug addiction, dysregulation of reward, and allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:97–129. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk DC. Contributions of the prefrontal cortex to the neural basis of human decision making. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26:631–664. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kufahl PR, Zavala AR, Singh A, Thiel KJ, Dickey ED, Joyce JN, Neisewander JL. c-Fos expression associated with reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior by response-contingent conditioned cues. Synapse. 2009;63:823–835. doi: 10.1002/syn.20666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviolette SR, Lipski WJ, Grace AA. A subpopulation of neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex encodes emotional learning with burst and frequency codes through a dopamine D4 receptor-dependent basolateral amygdala input. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6066–6075. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1168-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Grimm JW, Hope BT, Shaham Y. Incubation of cocaine craving after withdrawal: a review of preclinical data. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47 1:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham JA, Greenough WT. Experience-driven brain plasticity: beyond the synapse. Neuron Glia Biol. 2004;1:351–363. doi: 10.1017/s1740925x05000219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markou A, Weiss F, Gold LH, Caine SB, Schulteis G, Koob GF. Animal models of drug craving. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;112:163–182. doi: 10.1007/BF02244907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland K, Davidge SB, Lapish CC, Kalivas PW. Limbic and motor circuitry underlying footshock-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1551–1560. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4177-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty JF, Whitfield TW, Jr, Berglind WJ. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and cocaine addiction. Brain Res. 2010;1314:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O'Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. Jama. 2000;284:1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisewander JL, Baker DA, Fuchs RA, Tran-Nguyen LT, Palmer A, Marshall JF. Fos protein expression and cocaine-seeking behavior in rats after exposure to a cocaine self-administration environment. J Neurosci. 2000;20:798–805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00798.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien CP. Anticraving medications for relapse prevention: a possible new class of psychoactive medications. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1423–1431. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushworth MF, Walton ME, Kennerley SW, Bannerman DM. Action sets and decisions in the medial frontal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8:410–417. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbaum G, Setlow B. Cocaine makes actions insensitive to outcomes but not extinction: implications for altered orbitofrontal-amygdalar function. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:1162–1169. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbaum G, Setlow B, Saddoris MP, Gallagher M. Encoding predicted outcome and acquired value in orbitofrontal cortex during cue sampling depends upon input from basolateral amygdala. Neuron. 2003;39:855–867. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00474-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See RE, Elliott JC, Feltenstein MW. The role of dorsal vs ventral striatal pathways in cocaine-seeking behavior after prolonged abstinence in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;194:321–331. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0850-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesack SR, Grace AA. Cortico-Basal Ganglia reward network: microcircuitry. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:27–47. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Erb S, Stewart J. Stress-induced relapse to heroin and cocaine seeking in rats: a review. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;33:13–33. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev U, Grimm JW, Shaham Y. Neurobiology of relapse to heroin and cocaine seeking: a review. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:1–42. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Schmidt KT, Iordanou JC, Mustroph ML. Aerobic exercise decreases the positive-reinforcing effects of cocaine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;98:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofuoglu M, Kosten TR. Pharmacologic management of relapse prevention in addictive disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2004;27:627–648. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solinas M, Chauvet C, Thiriet N, El Rawas R, Jaber M. Reversal of cocaine addiction by environmental enrichment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17145–17150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806889105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solinas M, Thiriet N, El Rawas R, Lardeux V, Jaber M. Environmental enrichment during early stages of life reduces the behavioral, neurochemical, and molecular effects of cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1102–1111. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stairs DJ, Bardo MT. Neurobehavioral effects of environmental enrichment and drug abuse vulnerability. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;92:377–382. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stairs DJ, Klein ED, Bardo MT. Effects of environmental enrichment on extinction and reinstatement of amphetamine self-administration and sucrose-maintained responding. Behav Pharmacol. 2006;17:597–604. doi: 10.1097/01.fbp.0000236271.72300.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalnaker TA, Franz TM, Singh T, Schoenbaum G. Basolateral amygdala lesions abolish orbitofrontal-dependent reversal impairments. Neuron. 2007;54:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel KJ, Engelhardt B, Hood LE, Peartree NA, Neisewander JL. The interactive effects of environmental enrichment and extinction interventions in attenuating cue-elicited cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.09.014. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel KJ, Sanabria F, Pentkowski NS, Neisewander JL. Anti-craving effects of environmental enrichment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:1151–1156. doi: 10.1017/S1461145709990472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MJ, Kalivas PW, Shaham Y. Neuroplasticity in the mesolimbic dopamine system and cocaine addiction. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:327–342. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST, Carter BL. Is craving the source of compulsive drug use? J Psychopharmacol. 1998;12:23–30. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH. Neural consequences of environmental enrichment. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2000;1:191–198. doi: 10.1038/35044558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJ, Di Ciano P, Everitt BJ. Involvement of the dorsal striatum in cue-controlled cocaine seeking. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8665–8670. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0925-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS. Addiction, a disease of compulsion and drive: involvement of the orbitofrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:318–325. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J, Childress AR, Jayne M, Ma Y, Wong C. Cocaine cues and dopamine in dorsal striatum: mechanism of craving in cocaine addiction. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6583–6588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1544-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstanley CA. The orbitofrontal cortex, impulsivity, and addiction: probing orbitofrontal dysfunction at the neural, neurochemical, and molecular level. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1121:639–655. doi: 10.1196/annals.1401.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Ventral tegmental glutamate: a role in stress-, cue-, and cocaine-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56 1:174–176. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahm DS. The evolving theory of basal forebrain functional-anatomical ‘macrosystems’. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:148–172. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavala AR, Biswas S, Harlan RE, Neisewander JL. Fos and glutamate AMPA receptor subunit coexpression associated with cue-elicited cocaine-seeking behavior in abstinent rats. Neuroscience. 2007;145:438–452. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavala AR, Browning JR, Dickey ED, Biswas S, Neisewander JL. Region specific involvement of AMPA/Kainate receptors in Fos protein expression induced by cocaine-conditioned cues. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;18:600–611. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlebnik NE, Anker JJ, Gliddon LA, Carroll ME. Reduction of extinction and reinstatement of cocaine seeking by wheel running in female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;209:113–125. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1776-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]