Abstract

The trpc2 gene encodes an ion channel involved in pheromonal detection and is found in the vomeronasal organ. In tprc2-/- knockout (KO) mice, maternal aggression (offspring protection) is impaired and brain Fos expression in females in response to a male are reduced. Here we examine in lactating wild-type (WT) and KO mice behavioral and brain responses to different olfactory/pheromonal cues. Consistent with previous studies, KO dams exhibited decreased maternal aggression and nest building, but we also identified deficits in nighttime nursing and increases in pup weight. When exposed to the bedding tests, WT dams typically ignored clean bedding, but buried male-soiled bedding from unfamiliar males. In contrast, KO dams buried both clean and soiled bedding. Differences in brain Fos expression were found between WT and KO mice in response to either no bedding, clean bedding, or soiled bedding. In the accessory olfactory bulb, a site of pheromonal signal processing, KO mice showed suppressed Fos activation in the anterior mitral layer relative to WT mice in response to clean and soiled bedding. However, in the medial and basolateral amygdala, KO mice showed a robust Fos response to bedding, suggesting that regions of the amygdala canonically associated with pheromonal sensing can be active in the brains of KO mice, despite compromised signaling from the vomeronasal organ. Together, these results provide further insights into the complex ways by which pheromonal signaling regulates the brain and behavior of the maternal female.

Keywords: trpc2, vomeronasal, maternal, pheromone, defensive burying, amygdala

1. Introduction

Pheromonal sensing drives social behaviors and accompanying physiological responses in a range of species [2]. In most mammalian species, a vomeronasal organ (VNO) mediates much of pheromonal sensing, using receptors evolved to detect same-species chemical cues. An ion channel encoded by the trpc2 gene and located in the VNO and testes, mediates signaling in the VNO [34,35]. The trpc2-/- mouse (KO) has become a popular model for exploring the role of the VNO in a range of rodent behaviors, including male and female sexual behavior, aggression, and maternal behaviors [18,20,23,31].

It has been known for some time that the VNO plays an essential role in the production of maternal aggression [1]. In an earlier study, we quantified some effects of deleting the trpc2 gene on the behavioral responses of lactating mice to a novel male, as well as on the anatomy of the VNO and Fos expression in their brains [15]. Less is known about the role of the VNO in shaping responses to other pheromonal cues during lactation. In this study, we explore the impact of deleting the trpc2 gene on the response of lactating females to a potent and relevant cue: soiled bedding from the cage of group-housed male mice. We quantify both the behavioral and brain responses to this cue, using Fos immunoreactivity (Fos) to measure levels of brain activation in regions associated with olfaction, pheromonal sensing, and maternal behavior. At the same time, we follow up on work demonstrating that KO mice show deficiencies in pup-directed maternal behaviors [15,20] by performing frequent observations of KO and wild type (WT) mothers over the first five days and nights, postpartum. Together, these studies provide new information about how pheromonal information contributes to both behavior and brain activity during lactation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Animals and breeding

The animals in this study were derived from crosses of male KO mice bred in a C57BL6/J background (generously donated by Dr. Catherine Dulac, Harvard University) and wild-type females from our colony of hsd:icr mice selected for high levels of maternal defense (S) [8]. KO males and females were bred back into S mice for three generations, at which point the S background represented approximately 87% of the genetic background of the offspring. The WT and KO groups originated as littermates from heterozygote parents and the focal animals of this study were offspring of homozygous WTand KO pairings.

2.2 Animal conditions

All animals were housed in polypropylene plastic cages with ad lib access to tap water and food (Mouse Breeder Chow, Harlan) on a 14:10 light/dark cycle with lights on at 0600 CST. Cages were changed weekly, except during the postpartum period, when they were left undisturbed until the conclusion of the experiment for that animal. Virgin males and females were group housed until pairing for litters. Breeding pairs remained together for 10 days, at which point males were removed. Starting 18 days post-pairing, cages were checked for litters with any litters born before 1600 h considered born that day. Day of birth was considered postpartum day (PPD) 0. Dams and litters were weighed on PPD 0 and litters were culled to 11 pups. No dams with fewer than 8 pups in a litter were included in the study. Dams and litters were weighed again on PPD 6, prior to sacrifice. Due to experimental error, dam weights were not consistently collected on D6. This was purely a procedural error, but leads to different ns for the two groups. Pups in this study were not sexed, but we did analyze sex ratios in the progenitors of this line and found no sex ratio imbalance.

2.3 Genotyping

Mice were genotyped by PCR. To amplify the wild-type gene, two primers were used to identify the pore region of the Trpc2 ion channel: sense, 5’ – ACA GAG GAC CCC CAG TTT CT – 3’, and antisense 5’- ACA GAG GAA GGC AGT CAG GA – 3’. The deleted gene was replaced with a PGK- neo cassette in the knock-out mice [31] which we amplified using the following primers: 5’ – AAT ATC ACG GGT AGC CAA CG – 3’ and 5’ – TGC TCC TGC CGA GAA AGT AT – 3’.

2.4 Maternal behavior observations

The behavior of a subset of KO and WT dams was noted at 3 minute intervals for 2 hours during the day portion of the light cycle (between 900 and 1200 hours) and again during the dark portion of the light cycle (between 2000 and 2300 hours) on PPD 1 through 5. The following behaviors in any combination were noted: nursing, self-grooming, licking of pups, eating, drinking, nest-building, contact with pups (exclusive of nursing or licking).

A pup retrieval and nest-building test was performed on the evening of PPD 0 and morning of PPD 1. Pups were removed from the nest and then redistributed around the cage, avoiding the nest area. The observer noted latencies of the dam to: sniff the pups; retrieve the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and all pups; nest-build; and crouch over the pups.

2.5 Maternal aggression testing

On PPD5, after maternal behavior observations were complete, each dam was intruder tested. The female was brought in her home cage to the testing room, pups were removed from the cage, and an unrelated, sexually mature but naïve male from a cage of group-housed males was placed in her cage. Half the KO and half the WT dams were tested between 1300h and 1700h; the other half of each group was tested between 2000h and 2349h. The interaction between the mice was videotaped for 3 minutes, at which point the male was removed from the cage, the pups returned and the female's cage replaced in the home room. Videotapes were scored offline by individuals blind to the animal's genotype. Behaviors scored were: latency to first attack, total number of attacks, total time attacking.

2.6 Bedding testing

On PPD 6, KO and WT dams were brought into the testing room. Dams of each genotype were randomly assigned to one of three groups: soiled bedding (SB), clean bedding (CB) or no bedding (NB). Dams in the SB and CB groups had approximately 1 tablespoon of either soiled bedding from the cage of group-housed, adult male mice or clean bedding added to their cages on the opposite side of the cage from the nest. Pups remained in the cage so that we could quantify maternal behaviors in the presence of the bedding stimulus. Dams from all 3 groups were returned to their home room after 10 minutes. Dams presented with bedding were videotaped for 10 minutes; these tapes were scored by individuals blind to the genotype of each dam. Behaviors scored were: latency to sniff the bedding, total time sniffing the bedding, latency to defensively bury the bedding, total time defensive burying, and time spent on the side of the cage where the bedding had been deposited. Maternal behaviors scored in these tests included latency to crouch over pups, total time crouching, latency to nest-build, total time nest-building, bouts of nursing, bouts of pup grooming, and bouts of self-grooming.

2.7 Tissue Preparation

Dams were sacrificed 90 minutes following the introduction of bedding to the cage or after being brought to the testing room (in the case of dams presented with no bedding). After brief isoflurane anesthesia, the mice were deeply anesthetized with 0.15 mls of sodium pentobarbital and perfused pericardially, first with 0.9% saline and then with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Brains and olfactory bulbs were dissected, fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, and then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PBS.

In order to examine the accessory olfactory system, olfactory bulbs and the most rostral 2 mm of tissue from the brains were removed and cut sagittally into 40 μm sections using a sliding microtome (Leica, Microsystems, Heidelberg, Germany), and sorted into two alternate sets of sections in a 24-well plate containing cryoprotectant solution (PBS containing 30% sucrose, 30% ethylene glycol, and 10% polyvinylpryrrolidone) and stored at -20 C° until processing for immunoreactivity. The remaining caudal portions were frozen and sectioned frontally into 40 μm sections, sorted into two alternate sets, and stored identically to the olfactory sections.

2.8 Immunohistochemistry

To visualize Fos, one set of alternate sections was washed with PBS in the presence of 0.2% Triton X-100 (PBS-X), blocked in 5% normal goat serum for 1 hour, and incubated for 2 days at 4° C with anti-rabbit c-Fos antibodies (1:20,000; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Sections were then washed in PBS-X, incubated for 90 min at room temperature in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:500; Vector Laboratories, Burglingame, CA), washed in PBS-X, exposed to an avidin-biotin complex (Vector) for 1 hour, washed again in PBS-X, and stained with diaminobenzidine (0.7 mg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) as a chromagen, enhanced with 0.008% nickel chloride. Stained sections were then mounted, dehydrated, and coverslipped.

2.9 Image Analysis

The number of Fos-stained cells in a given region of the brain was quantified by projecting sections in bright-field from an Axioskop Zeiss microscope (Zeiss, Gottingen, Germany), through an Axiocam Zeiss high resolution digital camera attached to the microscope, to a computer running KS300 software (Zeiss). The software performed thresholding and cell counting with a paradigm similar to one previously employed [9,13,27]. Each region of the brain was identified and located using standard brain landmarks and counted in a frame of uniform size, with the exception of the mitral (MiA) and granular (GrA) layers of the accessory olfactory bulb (AOB). Because these cell layers are both relatively small and irregularly shaped, Fos was quantified in these regions using a macro built in KS300 to manually outline the layer on a digital image. Frame sizes used were the same as previously described [15]. The software then calculated the number of Fos-positive cells within the outlined area, using the same criteria used in the rest of the brain.

Several measures were taken to ensure Fos was measured consistently between samples [27]. All sections were processed in a single batch and exposed to diaminobenzidine for exactly 10 minutes. The background for each cell count was normalized by automatically adjusting light levels. A constant threshold level of staining was used to automatically distinguish Fos-positive cells. All slides were coded by one individual and counted by another who was blind to the test conditions. Fos-positive nuclei within a specified size range were counted.

2.10 Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were run using Sigma-Stat software (SPSS, Inc.) except for the comparisons of maternal behavior PPD1-PPD5, which were performed using SPSS (SPSS, Inc.). The cutoff value for significance for all tests was set at p < 0.05; values between 0.10 and 0.050 are considered trends.

Dam weights were compared by genotype using one-way ANOVAs; average individual pup weights were calculated for each litter by dividing total litter weight by number of pups and these average pup weights were compared by genotype using oneway ANOVAs. Pup counts were compared by genotype using one-way ANOVAs or Kruskal-Wallis ANOVAs on ranks, when data was non-normally distributed or of non-equal variance.

Maternal behavior observations were grouped into categories and quantified as a percentage of total observations. These totals were compared using two-way ANOVAs with genotype and light or dark cycle as variables. Non-normally distributed data was transformed where possible. Maternal aggression behavior was compared using one-way ANOVAs, or Kruskal-Wallis one way ANOVAs on rank, where data was non-normal or of non-equal variance. Bedding behavior was compared using two-way ANOVAs, with genotype and bedding type as variables and with one-way comparisons within genotype or bedding type.

Fos was analyzed using two-way ANOVAs using genotype and bedding as the variables. In cases where data were not normally distributed either a natural log or square root transform was used to attain or improve normality before running the tests. One-way ANOVAs were also run to provide specific comparisons between WT and KO mice for a given bedding condition. In studies comparing Fos expression across different genotypes and test conditions, it is often the case that data across the four groups are not normally distributed. Ideally, such groups would be compared using a well-validated, non-parametric equivalent of a 2-way ANOVA, but we know of no such test. However, in discussion with statisticians, we have learned that the 2-way ANOVA is actually fairly robust with respect to non-normality [12]. For this reason, in the few cases where we could not transform data to normality, we still include these results in Supplemental Table 1, but make clear to the reader that the data are not normally distributed so that the reader can evaluate the validity of the findings.

3. Results

3.1 Effect of trpc2 on response to bedding

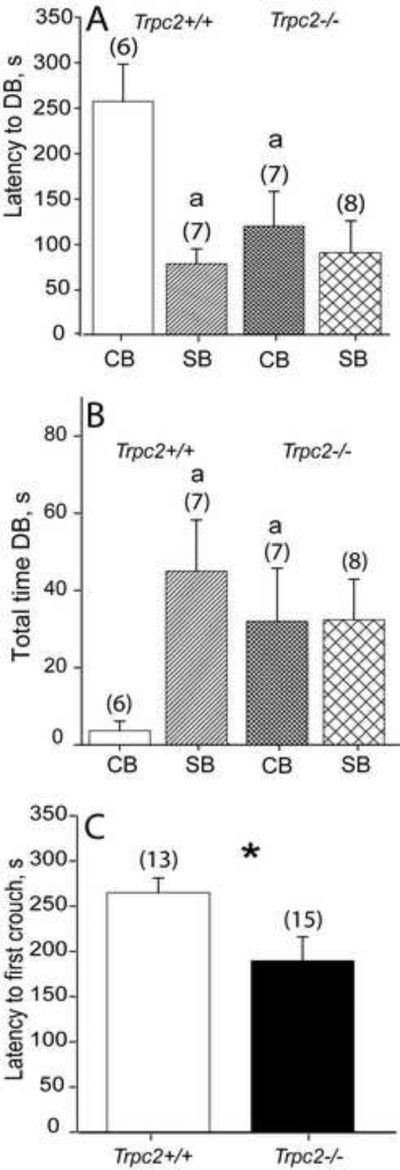

The strongest behavioral response in the bedding tests was defensive burying (Fig. 1). Latency to defensive burying was sensitive to bedding type depending upon the genotype of the animal: main effect of bedding type (F(1,27) = 9.41, P = 0.005); interaction of genotype and bedding type (F(1,27) = 4.87, P = 0.037). Post hoc tests show a significant effect of bedding type for WTdams but not for KO, with WTdams beginning to bury the SB much faster than the CB (P = 0.001). By contrast, KO dams did not distinguish between the two bedding types (P = 0.534) and took less time to approach the CB than did WTdams (P = 0.011). Comparing only WTdams, there was a significant effect of bedding type with animals spending more time burying SB than CB (P = 0.005, ANOVA on Ranks). There was no difference in time spent burying between the two KOgroups (P = 0.983). The KOand WT behavior differed when exposed to SB (P = 0.022). Neither the absence of the trpc2 gene nor the type of bedding presented to the animal had a significant impact on the animal's latency to make nose contact with the bedding (genotype, P = 0.650; bedding type, P = 0.337) or in total time spent in nose contact with the bedding (genotype, P = 0.105; bedding type, P = 0.882). There was no effect of genotype or bedding on time spent on the side of the cage where the bedding was deposited (genotype, P = 0.365; bedding type, P = 0.902). There was no effect of bedding or genotype on bouts of nursing, total time nursing, bouts of pup grooming or bouts of self-grooming.

Figure 1.

KO dams defensively bury both clean and soiled bedding. A) WT dams show a significantly longer latency to bury clean than soiled bedding, but KO dams begin burying both with a shorter latency, B) WT dams spend significantly more time burying soiled bedding than clean, but KO dams bury soiled and clean for longer periods. C) KO dams show a shorter latency to crouch over the nest than WT dams. KO = Trpc2-/-, WT = Trpc2+/+, CB = exposed to clean bedding, SB = exposed to soiled bedding. N's shown in parentheses. Bars marked with an a are significantly different from WT CB. * indicates P <0.05.

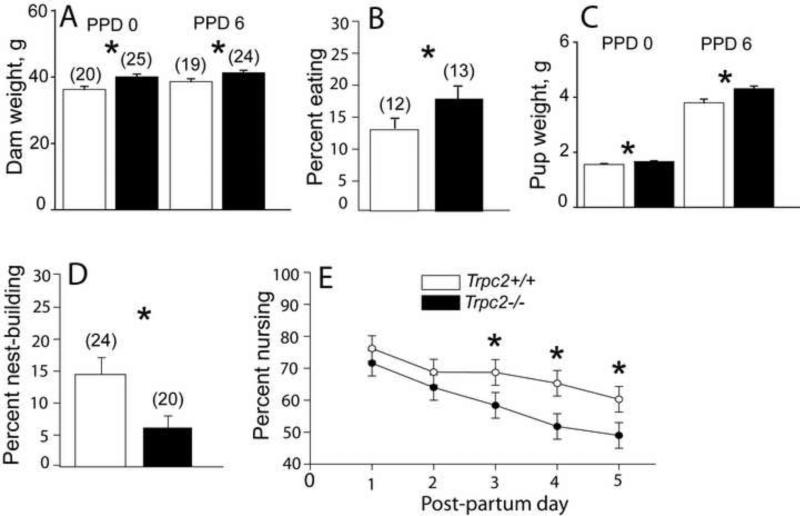

3.2 Impact of genotype on dam and pup weights

Litters were counted and both dams and pups were weighed on PPD 0 and on PPD 6 (Fig. 2). KO dams and pups were significantly heavier on both PPD 0 (mean dam weight, F(1, 44) = 9.2, P = 0.004; mean pup weight, F(1, 44) = 6.0, P = 0.019) and PPD 6 (mean dam weight, F(1, 33) = 4.5, P = 0.042; mean pup weight, F(1, 33) = 5.6, P = 0.025). Litter size did not differ on either day (P = 0.728; P = 0.130, respectively).

Figure 2.

KO dams and pups weigh more, KO dams provide different maternal care. A) KO dams weigh more than WT dams on PPD 6, B) KO dams eat/drink more frequently, C) KO pups weigh more than WT pups on PPD 0 and PPD 6, D) KO dams nest-build less frequently, E) KO dams nurse less frequently at night, starting at PPD 3. KO = Trpc2-/-, WT = Trpc2+/+, PPD = postpartum day. Ns shown in parentheses. * p < 0.05.

3.3 Effect of tprc2 on maternal behavior

On the evening of PPD 0 and the day of PPD 1, each dam was given a pup-retrieval and nest-building test. From PPD 1 through 5, maternal behaviors were observed in the home cage during both the light and dark cycles (Fig.2). KO dams took longer to initiate nest-building in the PPD 1 pup-retrieval test than WT dams (F(1, 25) = 13.6, P = 0.001) and nest built less frequently. Beginning the night of PPD 3, the groups showed significant differences in frequency of nursing (F(1, 24) = 8.6, P = 0.007), with KO dams nursing fewer times. The difference appears to be a function of time spent in the nest, since KO animals are in contact with their pups less frequently at night (F(1, 24) = 7.9, P = 0.010), and eat more frequently (F(1, 24) = 6.4, P = 0.019) than WT dams. A similar trend in frequency of contact appears in daytime behavior of KO dams (F = 3.64, P = 0.069). There was no effect of the tprc2 gene on pup retrieval in either the day or night tests (data not shown).

3.4 Effect of trpc2 on maternal aggression, night and day

Two out of 22 KO mice showed maternal aggression; the remaining 20 showed no aggression either at night or during the day. WT mice showed high levels of aggression overall (latency to attack 14.1 s ± 9, number of attacks 16.5 ± 2, mean total time attacking 42.6 s ± 6), with no effect of light cycle on any measure of aggression (data not shown). The only variable that showed an effect of light cycle was number of times the female sniffed the intruder. KO mice sniffed more frequently overall than WT (9.4 ± 1 vs 4.6 ± 1, two way ANOVA, F(1, 36) = 9, P = 0.005), and KO mice tested at night sniffed more frequently than those tested during the day (11.7 ± 1 vs 7.0 ± 1, P = 0.029). This effect of light cycle did not extend to total time spent sniffing, although KO mice still sniffed for longer than WT mice (54.1 s ± 6 vs 12.9 ± 7, one way ANOVA on ranks H = 17.8, p < 0.0001).

3.5 Fos in WT and KO mice

Two-way ANOVA analysis revealed a significant effect of both genotype and bedding type on Fos activity in a range of brain regions; see Supplemental Table 1 for a summary of p-values and F-statistics. Significant statistical results within and between each genotype, including mean ± SE, are provided in Table 1. As expected, in the AOB (including mitral and granular layers) the KO mice exhibited impairments of Fos activation in response to bedding cues. Suppression of Fos in response to bedding in KO mice was also found in a subset of regions that are downstream of AOB, including posteromedial cortex of the amygdala (PMCo) (which receives direct projections from AOB), basomedial amygdala (BMA), hypothalamic attack areas, and lateral periaqueductal gray (LPAG). The KO Fos responses to bedding were robust in some regions, however, including olfactory tubercle regions, medial amygdala (MeA), and basolateral amygdala (BLA), that latter two of which receive direct projections from AOB. Non-significant results (p≥ 0.05) are provided in Supplemental Table 2.

Table 1.

ANOVA tests with significant differences for Fos IR cell counts (means ± SE) in the CNS among WT and KO mice exposed to no bedding (none), clean bedding, or soiled bedding.

| Trpc2+/+ | Trpc2-/- | WT vs KO | WT vs KO | WT vs KO | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| | |||||||||

| Region | None | Clean | Soiled | None | Clean | Soiled | None | Clean | Soiled |

| MiAa | 34±10 a | 49±10 | 92±10 c | 17±9 | 23±9 | 30±9 | 0.235 | 0.232 | 0.002 |

| MiAp | 14±4 a | 33±4 b | 35±4 | 14±4 a | 21±4a | 28±4 | 0.942 | 0.232 | 0.269 |

| GrAa | 40±20 a | 103±20b | 115±20 | 22±18a | 36±18 | 44±18 | 0.496 | 0.072 | 0.029 |

| GrAp | 37±14 a | 79±14b | 103±14 | 15±14 a | 28±14 | 36±14 | 0.271 | 0.054 | 0.009 |

| MiA | 48±13 a | 87±13 | 127±1 c | 32±12 a | 47±12 | 58±12 | 0.371 | 0.094 | 0.006 |

| GrA | 80±30 a | 175±30b | 206±30 | 36±28 a | 54±28 | 80±28 | 0.296 | 0.014 | 0.009 |

| BAOT | 37±10 a | 50±10 | 75±10 c | 36±10 a | 49±9 | 68±10 | 0.935 | 0.919 | 0.684 |

| PMCo | 38±11 a | 56±11 | 89±10 c | 34±11 | 35±9 | 46±9 | 0.695 | 0.227 | 0.023 |

| Aco | 61±13 a | 79±13 | 100±13 | 73±13a | 70±12 | 105±12 c | 0.491 | 0.597 | 0.795 |

| MeA | 81±17a | 112±17 | 128±15 | 78±14 a | 77±14 | 139±15 c | 0.899 | 0.136 | 0.669 |

| BLA | 17±8a | 21±8 | 30±8 | 10±8 a | 21±9 | 40±7 c | 0.710 | 0.630 | 0.368 |

| BMA | 40±8 a | 58±8b | 61±8 | 46±8 | 47±8 | 60±7 | 0.368 | 0.425 | 0.962 |

| MPOM | 56±10 a | 48±9 | 89±10 c | 33±9 a | 42±8b | 63±9 | 0.073 | 0.614 | 0.173 |

| MPA | 48±8 | 39±8 | 65±8 c | 44±8 | 58±7 | 61±7 | 0.630 | 0.072 | 0.716 |

| PVN | 14±5a | 15±5 | 27±5 | 12±5 a | 13±4b | 26±5 | 0.647 | 0.345 | 0.805 |

| HAAa | 52±9 a | 47±9 | 87±9 c | 43±9 | 54±9 | 60±9 | 0.547 | 0.528 | 0.130 |

| LH | 51±10 | 42±10 | 75±10 c | 62±10 | 61±10 | 71±9 | 0.422 | 0.117 | 0.807 |

| HAAp | 43±10 a | 75±11 b | 105±11c | 60±11a | 83±9 | 85±9 | 0.278 | 0.538 | 0.184 |

| TuL | 17±15 | 23±14 | 41±14 | 15±14 a | 42±13b | 65±12 | 0.628 | 0.368 | 0.348 |

| TuM | 25±10a | 34±9 | 45±9 | 24±11 a | 43±9a | 57±8 | 0.949 | 0.453 | 0.326 |

| Pir1 | 53±21 a | 87±17 | 130±17 | 55±14a | 110±34a | 110±14 | 0.936 | 0.576 | 0.383 |

| Pir2 | 41±37 a | 129±34 b | 131±34 | 59±29 a | 148±29 b | 159±27 | 0.218 | 0.950 | 0.431 |

| LPAG | 100±11 a | 102±12 | 133±12 c | 71±12a | 82±10 | 97±10 | 0.037 | 0.319 | 0.019 |

| LC | 49±11 a | 50±11 | 91±12 c | 39±11 a | 55±10 | 86±10 c | 0.463 | 0.694 | 0.637 |

Results on left are for comparisons of bedding effect within each genotype. Data were natural log transformed to achieve normal distribution and equal variance, if necessary. Within a given genotype

(in bold) indicates that no bedding (none) is significantly different than soiled bedding.

(in bold) indicates that no bedding is significantly different than clean bedding.

(in bold) indicates that clean bedding is significantly different than soiled bedding. Letters shown in italics indicate trends with p-values between 0.05 and 0.10. Brain regions are listed from rostral to caudal. Results (p values) on right are for ANOVA comparisons between WT and KO for each bedding condition; P-values below 0.05 are indicated in bold, while P-values between 0.10 and 0.05 are indicated in italics. ANOVA on Ranks for MiAa, MiAp, GrAp, MiA, GrA, PVN, MeA, BLA, CeM, TuL, TuM, and Pir2. Aco, anterior cortex; BAOT, bed nucleus of the accessory olfactory tract; GrA, granular layer; GrAa, GrA anterior portion; GrAp, GrA posterior portion; HAAa, hypothalamic attack area, anterior portion; HAAp, HAA, posterior portion; LC, locus coeruleus; LH, lateral hypothalamus; MiA, mitral layer; MiAa, MiA anterior portion; MiAp, MiA posterior portion; MPA, medial preoptica area; MPOM, medial preoptic nucleus; Pir1, piriform cortex 1; Pir2, Pir 2; PVN, paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus; TuL, olfactory tubercle, lateral portion; TuM, Tu, medial portion.

4. Discussion

In this study, we explore effects of the trpc2 gene on maternal behavior and brain activity in the mouse. By presenting mice with soiled male bedding – as opposed to an actual male mouse, as in other studies of Trpc2-/- dams – we show that while the trpc2 gene may be necessary for generating an aggressive response, it is not necessary for marshalling a defensive one. Furthermore, Fos in the brains of KO mice indicates that regions of the brain canonically associated with pheromonally-mediated behaviors, such as the MeA, are activated in KO mice presented with soiled bedding, suggesting that these regions may not need complete signaling from the VNO-AOB accessory system in order to produce a response. By observing maternal behavior over more days and during both the light and dark periods, we also show a variety of deficits in maternal care associated with a reduction in pheromonal sensing.

4.1 Response to Soiled Bedding

We hypothesized that KO dams would react differently than WT dams to soiled bedding, and would treat clean bedding and soiled bedding similarly. Given that KO dams showed very little aggression towards male intruders, we expected that they would also respond passively to both bedding types. We were therefore surprised to find that KO dams actively buried both types of bedding (Fig. 1), suggesting both a failure to discriminate between different stimuli, and the capacity for an active responsive to aversive stimuli. However, the presence of pups in the cage during the encounter with novel bedding may also have been a confound in comparing KO behavior towards bedding to KO behavior towards a novel intruder. The presence of the pups might have led to a more active response to this cue, although earlier studies have not shown a reduction in the aggression normal female mice show an intruder if their pups are not present during an encounter.

Defensive burying behavior is considered an index of fear and anxiety [5]. Rates of defensive burying vary with reproductive state in rats [26], but the behavior persists through all reproductive and life stages and in both sexes. Interestingly, defensive burying behavior correlates highly with levels of intruder aggression in male rats and mice [30], but not in our WT or KO female mice (data not shown). Defensive burying does not appear to be dependent upon the VNO. Instead, defensive burying appears to be the default response to newly introduced bedding, at least in lactating mice. The role of the VNO seems to be to provide cues that signal the neutrality or lack of danger in a specific stimulus, rather than to actively promote a specific response, as is the case in confrontations between lactating and male mice. It is also worth noting that the clean bedding used in these tests was identical to that used in all the mouse cages in our colony, and every dam tested had been repeatedly exposed to this bedding during weekly cage changes prior to the postpartum period. The defensive burying seen in the KO mice suggests not only that the VNO is critical to distinguishing dangerous from benign, but also in remembering the valence of a stimulus between encounters.

4.2 VNO-activated brain circuit

Here, we used Fos as a proxy for neuronal activity in the AOB, as well as in brain regions associated with VNO-mediated behaviors. In many regions of the AOB, WT mice showed significant differences in Fos in comparisons between no bedding and clean bedding, clean bedding and soiled bedding, or soiled bedding and no bedding conditions (Table 1, Supplemental Table 1). This ability to distinguish between conditions at the level of the AOB is clearly compromised in the VNO of KO mice, but some regions do show higher levels of activation in animals exposed to soiled bedding compared to no bedding. Residual function in the VNO has been found for KO dams [18] and this could explain our findings. Further, increased Fos in KO mice could also be reflective of signaling from downstream brain regions that have reciprocal connections with the AOB [19,25]. Recent work suggests pathways from the main olfactory epithelium (MOE) to AOB [16] and from the main olfactory bulb to medial amygdala [17]. Both of these circuits can be activated by urine cues, which provides a possible explanation for some of the elevated Fos found in KO mice in AOB and vomeronasal amygdala. In a recent study, the disruption of the VNO impaired medial amygdala Fos responses to urine and predator cues [28] and this could be due to a more complete disruption of VNO signaling than in our study.

Patterns of Fos in regions of the brain responsible for olfactory processing reveal different strategies for interpreting the information found in soiled bedding. In both the lateral and medial regions of the Tu, KO animals show more robust responses to soiled bedding than do WT – a difference which might reflect compensation for the lack of pheromonal information reaching the KO brain. These differences do not result from more contact with the bedding, since there was no difference in time spent in contact with the soiled bedding between the two genotypes. Both genotypes showed higher levels of Fos in Pir when exposed to soiled bedding than other bedding types, but not in the same sub-regions. The Pir1 and 2 were responsive in the brains of WT dams, whereas Pir2 (posterior portion) was more responsive in the brains of KO dams. This effect corresponds with increased BLA Fos seen in the KO dams exposed to soiled bedding, as the BLA sends more projections to the Pir2 [24]. The posterior Pir also plays a more active role in forming odor-cue associations than the more anterior regions [4], and the higher levels of Fos seen in soiled bedding-exposed KO posterior Pir may reflect an attempt by the brain to recall or form associations between the bedding and its odors.

Within the amygdala, each genotype shows a unique pattern of response. Several regions of the amygdala are critical to the expression of maternal aggression, so we were particularly interested to see the effect of pheromonal cues alone on Fos in these regions. While WT animals actively responded to the soiled bedding by burying it, fewer regions within the WT amygdala were active in response to soiled bedding than to the presence of a live intruder [13]. Specifically, the MeA, BLA, and CeM did not show the robust increases in Fos in WT comparisons between clean bedding- and soiled bedding-exposed brains that we typically see in response to a novel male [9,10,13,14]. The contact time with bedding in this study was much lower than contact time with a live male (sniffing and aggression) in our previous study [15] and this could help account for the more modest response of the amygdala to bedding seen here. Our findings are consistent with studies in rats showing that lesions of the amygdala do not impair defensive burying of an electric probe [32]. However, the higher levels of Fos in the PMCo of WT animals exposed to soiled bedding compared to no bedding suggest that the WT amygdala is still more “interested” in the soiled bedding than in the clean bedding. KO mice did not show significant effects of bedding condition on Fos in PMCo, but did show increases in MeA, BLA and Aco. Given the failure of KO dams to distinguish between clean bedding and soiled bedding, the increased Fos levels in PMCo of WT dams suggests that it, along with the BAOT, the HAA and the medial preoptic areas, forms a network that evaluates signals received by the VNO. The MeA, BLA and Aco may be more involved in registering the general “aversiveness” of a stimuli, as well as producing a behavioral response.

Recently, we examined Fos in WT and KO lactating mice in response to maternal aggression testing (with a male mouse) and in the absence of testing [15]. In that study we found that exposure to a live male triggered heightened Fos activity in the AOB in WT compared with KO mice, providing a similar result as seen here. In downstream regions, WT male-exposed mice showed greater Fos activity relative to KO mice, including in regions such as MeA, LPO, PMCo, HAA, VMH, Tu, and LC. In this study, only PMCo and LPAG (and possibly VMH, p = 0.050) showed higher Fos activity in soiled bedding-tested WT versus KO mice. The lower number of highlighted regions in this study likely reflects lower sensory input from bedding (versus a live mouse) and lack of activation of the maternal aggression circuitry.

4.3 Pup care and nest-building behaviors

Most previous research on the contributions of the vomeronasal system (VNS) to maternal behavior in rodents has concluded that pheromonal cues facilitate maternal defense but inhibit or have no effect on the production of pup-directed care [6,11,22,33]. However, more recent data [20] contradict this view, showing that lactating KO females spend less time on-nest than WT mice. Using an observation paradigm developed to discern subtle behavioral differences [7], we also found that lactating KO mice nurse and nest-build less frequently than WTdams, while eating more (Fig. 2). These data might suggest that Trpc2-/- mice are deficient mothers, perhaps because signals from the VNO are important to maintaining maternal motivation. Support for this hypothesis comes from work on the roles of the main and accessory olfactory systems in mate recognition. These studies show that while the AOB is not necessary for mate recognition, it does enhance an animal's motivation to seek a mate [16]. However, these behavioral deficits have no impact on litter size, pup survivorship or weight. In fact, both KO dams and pups weighed more than controls on PPD0 and PPD6, findings which suggest either that KO pups nurse more effectively, or that KO milk is more nutritious. These effects may point to a role of the VNO-AOB system in regulating metabolism.

The reductions in nest-building seen in the KO dams could also be a reflection of alterations in metabolic function. One function of nest-building is to regulate ambient temperature in the nest [3]; reductions in nest-building may indicate that KO dams and/or their pups have higher basal body temperatures than their WT counterparts. Both feeding behavior and basal body temperature are regulated by the hypothalamus [29], a brain region targeted both directly and indirectly by the VNS [19]. There is some evidence of a role for pheromonal cues in regulating metabolism – for example, male rat pheromones can evoke body temperature changes in other rats [21] – but clearly, more data are needed before drawing conclusions about the impact of the VNS on metabolism.

4.4 Conclusion

Here we show a range of impacts on brain and behavior in lactating mice from disruption of the trpc2 gene. One key goal of this study was to gain a deeper understanding of the brain circuitry mediating the response to pheromonal cues during lactation. We show that in normal mice, the PMCo consistently responds to pheromonal cues from novel males, whether or not an actual male is present, suggesting that this region is a linchpin between the VNO-AOB and downstream brain systems that generate response. We also show that regions of the amygdala that are typically activated in dams during maternal aggression – the MeA, BLA and Aco – are not activated in the absence of an actual novel male mouse, suggesting that these regions play a role in the production of maternal aggression, but not in parsing the nature of pheromonal cues. Interestingly, KO dams do appear to use these regions of the brain during defensive burying, suggesting that multiple brain systems or strategies may be recruited in service of a common behavioral response. Studies that target PMCo or MeA specifically could help unravel the specific contributions of these regions to these aspects of maternal pheromonal response.

This study also demonstrates wider-ranging impacts of the VNO-AOB system on maternal behaviors than previously thought, from stimulating eating and defensive burying to reducing nursing and maternal aggression. Further studies are needed to tease apart these effects, in particular those that suggest a role in motivation from those that suggest a role in metabolic regulation, keeping in mind that these two systems are also linked. By exploring how pheromonal signaling drives maternal behaviors at this most proximate level, we may deepen our understanding of how evolution has shaped mammalian females to deliver the demanding and critical care our infants need.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 MH066086 and MH085642 to S.C.G, NSF grant 0921706 to S.C.G., and an AAUW American Fellowship to N.S.H. The authors wish to thank Dr. Catherine Dulac for generous donation of animals; James Curley for help with statistical analysis; Kate Skogen and Jeff Alexander for animal care; and Sharon Stevenson, Amy Toberman, and Sarang Patel for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bean NJ, Wysocki CJ. Vomeronasal organ removal and female mouse aggression: the role of experience. Physiol Behav. 1989;45:875–82. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brennan PA, Kendrick KM. Mammalian social odours: attraction and individual recognition. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361:2061–78. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bult A, Lynch CB. Multiple selection responses in house mice bidirectionally selected for thermoregulatory nest-building behavior: crosses of replicate lines. Behav Genet. 1996;26:439–46. doi: 10.1007/BF02359488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calu DJ, Roesch MR, Stalnaker TA, Schoenbaum G. Associative encoding in posterior piriform cortex during odor discrimination and reversal learning. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:1342–9. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Boer SF, Koolhaas JM. Defensive burying in rodents: ethology, neurobiology and psychopharmacology. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;463:145–61. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Del Cerro MC. Role of the vomeronasal input in maternal behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23:905–26. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Francis D, Diorio J, Liu D, Meaney MJ. Nongenomic transmission across generations of maternal behavior and stress responses in the rat. Science. 1999;286:1155–8. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gammie SC, Garland T, Stevenson SA. Artificial selection for increased maternal defense behavior in mice. Behav Genet. 2006;36:713–722. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9071-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gammie SC, Negron A, Newman SM, Rhodes JS. Corticotropin-releasing factor inhibits maternal aggression in mice. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118:805–14. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.4.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gammie SC, Nelson RJ. cFOS and pCREB activation and maternal aggression in mice. Brain Res. 2001;898:232–41. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gandelman R, Zarrow MX, Denenberg VH. Reproductive and maternal performance in the mouse following removal of the olfactory bulbs. Journal of Reproduction & Fertility. 1972;28:453–6. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0280453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harwell MR, Rubinstein EN, Hayes WS, Olds CC. Summarizing Monte-Carlo results in methodological research - the 1-factor and 2-factor fixed effects anova cases. Journal of Educational Statistics. 1992;17:315–339. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasen NS, Gammie SC. Differential fos activation in virgin and lactating mice in response to an intruder. Physiol Behav. 2005;84:684–695. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasen NS, Gammie SC. Maternal aggression: new insights from Egr-1. Brain Res. 2006;1108:147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasen NS, Gammie SC. Trpc2 gene impacts on maternal aggression, accessory olfactory bulb anatomy and brain activity. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:639–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jakupovic J, Kang N, Baum MJ. Effect of bilateral accessory olfactory bulb lesions on volatile urinary odor discrimination and investigation as well as mating behavior in male mice. Physiol Behav. 2008;93:467–73. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang N, Baum MJ, Cherry JA. A direct main olfactory bulb projection to the ‘vomeronasal’ amygdala in female mice selectively responds to volatile pheromones from males. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:624–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06638.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelliher KR, Spehr M, Li XH, Zufall F, Leinders-Zufall T. Pheromonal recognition memory induced by TRPC2-independent vomeronasal sensing. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:3385–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keverne EB. The vomeronasal organ. Science. 1999;286:716–20. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimchi T, Xu J, Dulac C. A functional circuit underlying male sexual behaviour in the female mouse brain. Nature. 2007;448:1009–14. doi: 10.1038/nature06089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiyokawa Y, Kikusui T, Takeuchi Y, Mori Y. Alarm pheromones with different functions are released from different regions of the body surface of male rats. Chem Senses. 2004;29:35–40. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjh004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lepri JJ, Wysocki CJ, Vandenbergh JG. Mouse vomeronasal organ: effects on chemosignal production and maternal behavior. Physiol Behav. 1985;35:809–14. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(85)90416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leypold BG, Yu CR, Leinders-Zufall T, Kim MM, Zufall F, Axel R. Altered sexual and social behaviors in trp2 mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6376–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082127599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Majak K, Ronkko S, Kemppainen S, Pitkanen A. Projections from the amygdaloid complex to the piriform cortex: A PHA-L study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2004;476:414–28. doi: 10.1002/cne.20233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martel KL, Baum MJ. Sexually dimorphic activation of the accessory, but not the main, olfactory bulb in mice by urinary volatiles. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:463–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05651.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Picazo O, Fernandez-Guasti A. Changes in experimental anxiety during pregnancy and lactation. Physiol Behav. 1993;54:295–9. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90114-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rhodes JS, Garland T, Jr., Gammie SC. Patterns of brain activity associated with variation in voluntary wheel-running behavior. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:1243–56. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.6.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samuelsen CL, Meredith M. The vomeronasal organ is required for the male mouse medial amygdala response to chemical-communication signals, as assessed by immediate early gene expression. Neuroscience. 2009;164:1468–76. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saper CB, Lu J, Chou TC, Gooley J. The hypothalamic integrator for circadian rhythms. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:152–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sgoifo A, de Boer SF, Haller J, Koolhaas JM. Individual differences in plasma catecholamine and corticosterone stress responses of wild-type rats: relationship with aggression. Physiol Behav. 1996;60:1403–7. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00229-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stowers L, Holy TE, Meister M, Dulac C, Koentges G. Loss of sex discrimination and male-male aggression in mice deficient for TRP2. Science. 2002;295:1493–500. doi: 10.1126/science.1069259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Treit D, Menard J. Dissociations among the anxiolytic effects of septal, hippocampal, and amygdaloid lesions. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111:653–8. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.3.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vandenbergh JG. Effects of central and peripheral anosmia on reproduction of female mice. Physiol Behav. 1973;10:257–61. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(73)90307-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yildirim E, Birnbaumer L. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 179. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2007. TRPC2: molecular biology and functional importance. pp. 53–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zufall F, Ukhanov K, Lucas P, Liman ER, Leinders-Zufall T. Neurobiology of TRPC2: from gene to behavior. Pflugers Archive for European Journal of Physiology. 2005;451:61–71. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.