Abstract

Background

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) functions within the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway as a critical modulator of cell survival. On the basis of promising pre-clinical data, the safety and tolerability of therapy with the mTOR inhibitor RAD001 in combination with radiation (RT) and temozolomide (TMZ) was evaluated in this Phase I study.

Methods

All patients received weekly oral RAD001 in combination with standard chemo-radiotherapy, followed by RAD001 in combination with standard adjuvant temozolomide. RAD001 was dose escalated in cohorts of 6 patients. DLTs were defined during RAD001 combination therapy with TMZ/RT.

Results

Eighteen patients were enrolled with a median follow-up of 8.4 months. Combined therapy was well tolerated at all dose levels with 1 patient on each dose level experiencing a DLT: Grade 3 fatigue, Grade 4 hematologic toxicity, and Grade 4 liver dysfunction. Throughout therapy, there were no Grade 5 events, 3 patients experienced Grade 4 toxicities and 6 patients had Grade 3 toxicities attributable to treatment. On the basis of these results, the recommended Phase II dose currently being tested is RAD001 70 mg/week in combination with standard chemo-radiotherapy. FDG PET scans also were obtained at baseline and after the second RAD001 dose prior to initiation of TMZ/RT: the change in FDG uptake between scans was calculated for each patient. Fourteen patients had stable metabolic disease and 4 patients had a partial metabolic response.

Conclusions

RAD001 in combination with RT/TMZ and adjuvant TMZ was reasonably well tolerated. Changes in tumor metabolism can be detected by FDG PET in a subset of patients within days of initiating RAD001 therapy.

Keywords: glioblastoma, radiation, temozolomide, fluorodeoxyglucose PET, everolimus

INTRODUCTION

Sirolimus and everolimus (RAD001) are structurally related drugs that selectively inhibit the signaling activity of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). mTOR functions within 2 distinct complexes, mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTORC2, and the sirolimus-family of drugs selectively suppress signaling through mTORC1. This complex functions downstream from multiple receptor tyrosine kinases in a PI3K/Akt-dependent pathway to promote cell growth and proliferation 1, 2. mTORC1 signaling also modulates expression of vascular endothelial growth factor during hypoxia, and mTOR inhibitors are anti-angiogenic in multiple tumor types 3. Hyperactivation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling is common and is associated with increased dependence on mTOR signaling in a subset of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) 4–6. While monotherapy with mTOR inhibitors in recurrent GBM has limited activity 7, 8, pre-clinical studies in GBM and melanoma models suggest the combination of mTOR inhibitors with either radiation or temozolomide provide additive to synergistic enhancement of cell killing 9–11. Based on these data, the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG) N057K clinical trial was initiated to evaluate the acute tolerability of RAD001 therapy integrated with standard temozolomide (TMZ) and radiotherapy (RT) in patients with newly diagnosed GBM.

METHODS and MATERIALS

Eligibility Criteria

Patients with a new diagnosis of a World Health Organization (WHO) Grade IV astrocytoma, confirmed by central review, were enrolled between 1 and 6 weeks following surgical resection or biopsy. Additional enrollment criteria were: age 18 years or older, ECOG performance status of 0–2, absolute neutrophil count ≥1500/μL, hemoglobin ≥9.0g/dL, platelets ≥100,000/μL, total bilirubin ≤2.5× upper limit of normal (ULN), serum total cholesterol <350mg/dL, serum total triglycerides <400mg/dL, SGOT ≤2.5× ULN, creatinine ≤1.5× ULN, measurable disease ≥1cm3, willingness to undergo research PET scans and blood sampling. Specific exclusion criteria included: 1) prior chemotherapy for a CNS malignancy, prior treatment with TMZ or mTOR inhibitor, or prior cranial irradiation, 2) pregnant women or refusal to use contraception, 3) patients taking enzyme-inducing anti-convulsants, because of their effect on RAD001 metabolism 12, 13 4) major trauma or surgery within 21 days, 5) HIV infection; other medical or social situations that would limit study compliance, 6) other cancers requiring active therapy or >30% risk of death from prior cancer within 2 years, 7) inability to take oral medication, prior surgical procedures affecting gastrointestinal absorption, or uncontrolled peptic ulcer disease, 8) allergy to dacarbazine or currently taking warfarin.

Protocol therapy

The protocol was approved by the Mayo Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from patients prior to enrollment at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota and Jacksonville, Florida. RAD001 was provided by Novartis (Basel, Switzerland). The treatment schema is outlined in Figure 1. The dose and schedule for RT and TMZ conformed to the standard of care. RAD001 was taken orally weekly starting 1 week prior to RT/TMZ and continued through the end of radiation. Patients had a 4–6 week break without therapy prior to adjuvant treatment. Adjuvant TMZ was administered for 6 – 28 day cycles with treatment on Days 1–5 at 200 mg/m2/day. RAD001 was delivered weekly (Days 1, 8, 15, 22) during adjuvant therapy and then continued weekly until disease progression or intolerance. Antibiotic prophylaxis with either Bactrim or intravenous pentamidine and oral levofloxacin was required throughout and 1 month following completion of drug therapy.

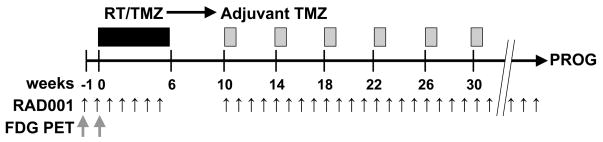

Figure 1.

The treatment schema for this Phase I trial is shown. RAD001 was given weekly during concomitant radiation (RT) and temozolomide (TMZ) and then during after adjuvant TMZ. FDG PET scans were performed before the 1st dose and after the 2nd dose of RAD001, before RT and TMZ were started.

RT was delivered using 3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy to a total dose of 60 Gy in 30 fractions. An initial treatment volume was treated to 50 Gy in 25 fractions with fields defined as 2 cm to the field edge beyond the T2 or FLAIR (fluid attenuated inversion recovery) MRI signal abnormality. A boost of 10 Gy in 5 fractions was then delivered with fields defined as 2 cm to field edge beyond the contrast-enhancing abnormality seen on the T1-weighted scans. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy was allowed with 54 Gy to PTV1 and 60 Gy to PTV2 in 30 fractions. During RT, TMZ was delivered daily at 75 mg/m2/day. The dose of RT was fixed, but dosing of TMZ and/or RAD001 was adjusted for hematologic toxicities and non-hematologic toxicities.

The dose of RAD001 was escalated in cohorts of 6 patients. The starting dose for RAD001 was 30 mg/week and subsequent dose levels were 50 and 70 mg/week, respectively. Patients were assessed during RT for dose-limiting toxicities (DLT). DLTs were defined as failure to deliver greater than 75% of the planned doses of TMZ or RAD001 during RT, interruption of radiation for more than 5 days due to toxicity, or the following: ≥grade 3 diarrhea or skin rash, ≥grade 4 neutropenia, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia, ≥grade 4 hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesterolemia or hyperglycemia despite optimal medical management, other ≥grade 3 non-hematological events, or ≥grade 4 radiation dermatitis. MTD was defined a priori as the highest dose level at which 0 or 1 of 6 patients developed DLTs.

Patient Evaluations

Patients underwent baseline evaluation within 14 days of registration, which included consultations with medical and radiation oncologists, history, physical and mini-mental status exam, brain MRI, and laboratory testing. For women with child-bearing potential, a serum pregnancy test was required within 7 days of registration. Toxicity assessments were performed weekly during RT and with each cycle of adjuvant therapy. During RT, a CBC was obtained weekly and the chemistries were obtained at week 4. CBC and chemistries were obtained at each adjuvant TMZ cycle and then at increasing intervals during adjuvant RAD001 monotherapy. MRI was performed at baseline, just prior to adjuvant TMZ cycles 2, 4 and 6 and then at 2 months or greater intervals during RAD001 monotherapy.

PET imaging and RAD001 levels

FDG PET or PET/CT scans were obtained prior to initiation of treatment and within 24 hours of the second dose of RAD001. The PET images were acquired using PET/CT scanners (Discovery RX; GE Healthcare) or (ECAT EXACT HR+ scanner; Siemens Healthcare). Fasting subjects were injected with 370–685 MBq of 18F-FDG and imaged 35 minutes later. A 10 minute PET scan was obtained, consisting of five 2-minute dynamic frames. A low dose CT or Germanium-68 transmission scan was obtained for attenuation correction. All 18F-FDG PET images were interpreted by a single observer with expertise in PET imaging of brain tumors. MRI performed close to the time of 18F-FDG PET was used to aid in the interpretation. The interpreting physician placed a region of interest (ROI) over the tumor area with the highest FDG uptake. The maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) normalized for body weight and decay-corrected dose of each tumor ROI was recorded. The percent change in SUVmax was calculated as follows:

Serum levels of RAD001 were measured 24 hours after the first dose of drug and immediately prior to the second dose of RAD001 6 days later. RAD001 blood levels were determined by Clinical Reference Laboratory (CRL: Lenexa, KS).

Assessment of response and toxicity

Response was evaluated by MRI and categorized as previously described 14. Metabolic response measured on serial FDG PET scans was defined as described by the EORTC PET Study Group 15.

Statistical considerations

Adverse events (AEs) were reported according to the Common Toxicity Criteria (CTCAE) version 3.0. Toxicities were defined as adverse events that were deemed possibly, probably, or definitely related to study treatment. Overall toxicity incidence was summarized using frequency distributions and descriptive measures. A cohort-of-6 design was selected to allow a meaningful interpretation of the FDG PET scans that were performed in this study. The primary endpoint was MTD, and secondary endpoints included best objective status and time to progression. The percent change of SUVmax levels (from baseline to post-RAD001 treatment) were compared across all dose levels using ANOVA/Kruskal-Wallis test and pairwisely using a Wilcoxon rank sum test. The percent change of SUVmax levels was correlated to RAD001 serum levels using Spearman rank correlation coefficient.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Between May 30, 2008 and May 29, 2009, 18 patients were enrolled on this clinical study. All 18 patients received the study treatment and were evaluable for toxicity. The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Phase I (N=18) | |

|---|---|

| Age, median(range) | 57.5 (23,74) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 9 (50%) |

| Male | 9 (50%) |

| Race | |

| White | 17 (94%) |

| Asian | 1 (6%) |

| Performance Score | |

| 0 | 4 (22%) |

| 1 | 9 (50%) |

| 2 | 5 (28%) |

| Corticosteroid Therapy | |

| Yes | 12 (67%) |

| No | 6 (33%) |

| Extent of Resection | |

| Biopsy | 4 (22%) |

| Subtotal Resection | 10 (56%) |

| Gross Total Resection | 4 (22%) |

| Laterality | |

| Right | 12 (67%) |

| Left | 6 (33%) |

| History Brain Cancer | |

| Yes | 2 (11%) |

| No | 16 (89%) |

Toxicities

Dose-limiting toxicities were defined during concomitant treatment with RAD001, RT, and TMZ. One of 6 patients had a DLT at each of the 3 dose levels: Grade 3 fatigue (30 mg/week RAD001), Grade 4 neutropenia, lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia (50 mg/week RAD001), and Grade 4 bilirubin and transaminitis secondary to reactivation of a latent hepatitis B infection (70 mg/week RAD001, no steroids). No patients required interruption of RT or failed to receive greater than 75% of the planned TMZ or RAD001 doses. A summary of toxicities occurring during all cycles of therapy is provided in Table 2. Overall, 6 patients experienced a Grade 3 toxicity and 3 patients experienced a Grade 4 toxicity. The most common toxicities were Grade 3 or 4 fatigue and Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, leukopenia, or thrombosis. Hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia and thrombocytopenia were the most common Grade 1 or 2 toxicities. One patient developed a Grade 2 infection of herpes zoster while on maintenance RAD001 therapy after completing adjuvant TMZ/RAD001. The overall rate of greatest toxicity for patients treated on N057K is summarized at the bottom of Table 2 and is similar to a previous NCCTG Phase I/II trial in newly diagnosed GBM evaluating the combination of erlotinib, radiation and temozolomide 16. Thus, therapy with RAD001 combined with RT/TMZ and adjuvant TMZ was relatively well tolerated with only modest toxicities at doses up to 70 mg/week.

Table 2.

Summary of toxicities

| GRADE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| % | % | % | % | % | |

| HYPERCHOLESTEROLEMIA | 56 | 33 | |||

| THROMBOCYTOPENIA | 83 | 6 | |||

| HYPERTRIGLYCERIDEMIA | 61 | 11 | |||

| NAUSEA | 17 | 28 | |||

| NEUTROPENIA | 6 | 28 | 6 | 6 | |

| FATIGUE | 17 | 11 | 6 | ||

| LEUKOPENIA | 22 | 6 | 6 | ||

| DIARRHEA | 17 | 6 | |||

| RASH | 11 | 11 | |||

| ANOREXIA | 11 | 6 | |||

| COUGH | 17 | ||||

| THROMBOSIS | 6 | 6 | 6 | ||

| ANEMIA | 6 | 6 | |||

| CONSTIPATION | 11 | ||||

| WEIGHT LOSS | 11 | ||||

| BILIRUBIN | 6 | ||||

| DEHYDRATION | 6 | ||||

| DYSPNEA | 6 | ||||

| HYPOCALCEMIA | 6 | ||||

| HYPOPHOSPHATEMIA | 6 | ||||

| HYPOTENSION | 6 | ||||

| INFECTION | 6 | ||||

| ORAL MUCOSITIS | 11 | ||||

| SGOT ELEVATION | 6 | ||||

| SGPT ELEVATION | 6 | ||||

| TASTE | 6 | ||||

| VOMITING | 6 | ||||

| GREATEST TOXICITY: N057K | 2 (11%) | 8 (44%) | 5 (28%) | 3 (17%) | 0 |

| GREATEST TOXICITY: N0177 | 5 (5%) | 26 (27%) | 46 (48%) | 13 (14%) | 2 (2%) |

Response Assesment

The disease status for the 18 patients treated on this trial is shown in Table 3. The best patient response obtained during treatment included 1 partial response, 1 regression, 15 stable disease, and 1 progressive disease. Five patients remain on active therapy, and of the patients no longer on treatment, 10 of 13 discontinued due to disease progression or death, 2 due to adverse events, and 1 due to refusal of further treatment. Given the limited number of patients and short follow-up, no conclusions can be drawn regarding efficacy of the regimen.

Table 3.

Response to therapy

| Phase I (N=18) | |

|---|---|

| Number cycles received, median(range) | 4.5 (1,11) |

| Follow-up Status | |

| Alive | 14 (78%) |

| Dead | 4 (22%) |

| Median follow-up in months (range) | 8.4 (1.8, 15.9) |

| Progression Status | |

| No progression | 8 (44%) |

| Progression | 10 (56%) |

| Best Response | |

| Partial response / regression | 2 (12%) |

| Stable disease | 15 (82%) |

| Progressive disease | 1 (6%) |

| Off Active Treatment | |

| Yes | 13 (72%) |

| No | 5 (28%) |

| Reason End Treatment (% out of 7) | |

| Disease Progression | 9 (69%) |

| Refused Further Rx | 1 (8%) |

| Adverse Event | 2 (15%) |

| Died on Study | 1 (8%) |

FDG-PET imaging

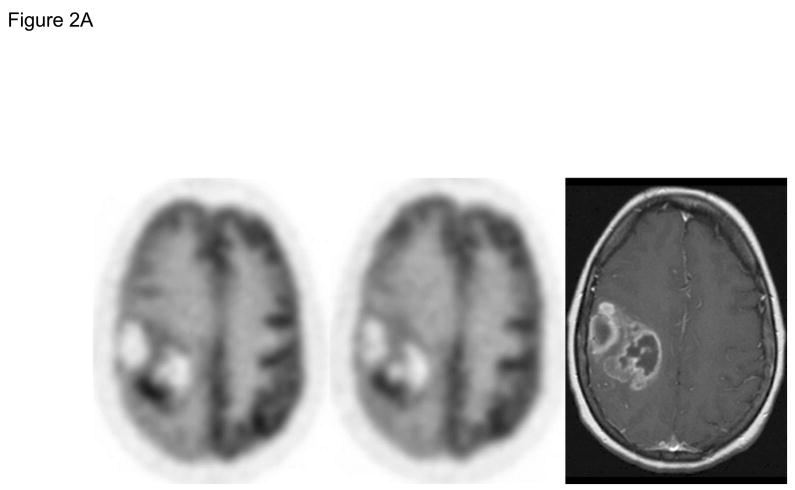

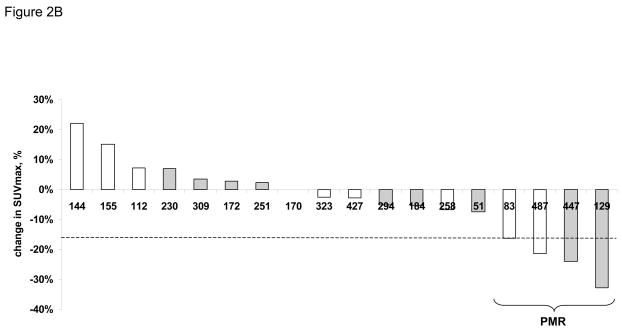

Early imaging with FDG PET was performed on all patients before and after 1 week of RAD001 therapy, prior to initiation of RT/TMZ. Across 18 pairs of pre- and post-treatment scans obtained on patients with less than a gross total resection, the median difference in SUVmax was −3%, and there was no significant difference in SUVmax change between the 3 dose-levels (p=0.66). According to the EORTC response criteria, no patients had a complete metabolic response, 4 patients had a partial metabolic response (PMR: >15% decrease in SUVmax), and 14 patients had stable metabolic disease (SMD: <25% increase to < 15% decrease in SUV) (Figure 2). Of the 4 patients with a PMR, 2 are alive without radiographic progression at 83 and 487 days of follow-up, and 2 are alive with disease progression detected at 129 and 447 days.

Figure 2.

FDG PET brain scans were obtained before (pre-RAD001) and after the 2nd dose of RAD001 (post-RAD001), and the change in SUVmax was calculated for each patient. A) Representative pre- and post-RAD001 PET scans from a patient with a partial metabolic response (PMR) is shown with a corresponding axial T1 MR image with gadolinium. B) Waterfall plot of change in SUVmax for each patient is shown. Those patients in white are alive without evidence of progression. Those in gray are either dead or alive with progressive disease. The numbers along the X-axis are the days from diagnosis to last follow-up or date of progressive disease, respectively.

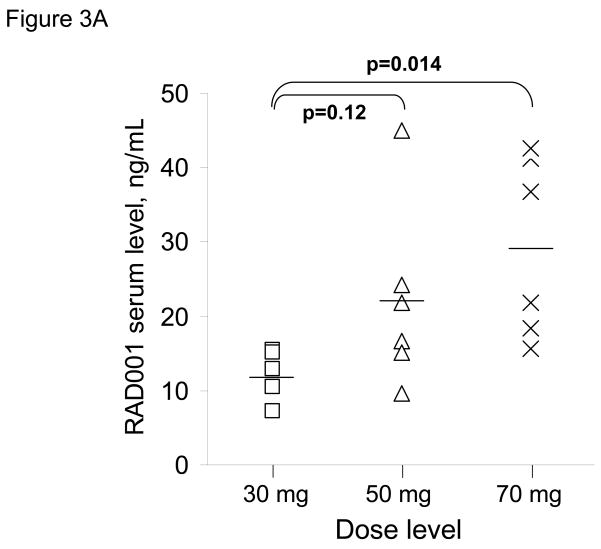

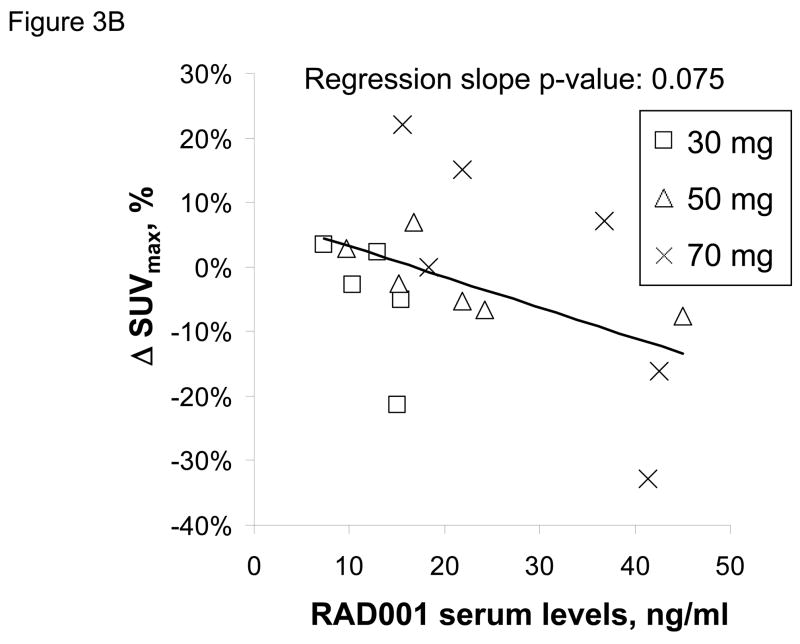

RAD001 blood levels were determined 24 hours after the first dose of RAD001 in 17 of 18 patients and trough levels just prior to the 2nd dose were obtained in 16 of 18 patients. Twenty-four hours following RAD001 dosing, the mean serum drug level for patients in the 30 mg dose cohort (12.2 ng/ml) was lower than those in the 50 mg cohort (22.1 ng/ml; p=0.12) and the 70 mg cohort (29.4 ng/ml; p=0.014) (Figure 3A). The mean trough drug levels were 0, 0.2, and 2.5 ng/ml for the 30, 50 and 70 mg dose cohorts, respectively; trough everolimus levels were detectable only in the 3 patients with initial 24 h drug levels exceeding 40 ng/ml. Correlation of the 24 hour everolimus level with PET imaging data, showed a marginal trend towards greater suppression of SUVmax in association with higher 24 hour drug blood levels (Figure 3B). Thus, while higher RAD001 serum levels were achieved at higher dose levels, there was not a robust association between serum drug level and the extent of SUVmax suppression.

Figure 3.

Serum drug levels and change in SUVmax by PET. A) RAD001 serum levels were obtained 24 hours after the first dose of RAD001 and are plotted for individual patients according to dose cohort. The mean serum level for each cohort is shown as a horizontal line. B) RAD001 serum levels are plotted relative to the change in SUVmax for 17 patients treated on this trial.

DISCUSSION

Concurrent suppression of mTOR signaling during radiation and/or chemotherapy has the potential to enhance the efficacy of treatment. In this Phase I study, weekly oral RAD001 combined with RT/TMZ and adjuvant TMZ was well tolerated with an acceptable rate of toxicity. The spectrum of toxicities observed are encompassed by the known risks of TMZ-based chemoradiotherapy or RAD001 therapy with the most common adverse events including fatigue, thrombosis, thrombocytopenia and elevated lipids. Consistent with the safety of combining RAD001 with radiation, a previous clinical trial performed at Mayo Clinic demonstrated that sirolimus combined with 60 Gy of radiation and weekly cisplatin in patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer was well tolerated without elevated radiation-induced toxicities 17. In solid tumors, weekly dosing with RAD001 has been limited to 70 mg/week based on known biological activity and tolerability in patients 18, and at this dose level, only 1 of 6 patients experienced a DLT on this trial. Throughout the entire course of treatment, 33% and 17% of patients experienced Grade 3 or 4 toxicities, respectively, which is similar to that reported in a previous NCCTG trial testing erlotinib combined with standard chemo-radiotherapy (48% and 14%, respectively) 16. In contrast to our results with weekly RAD001, dose-limiting myelosuppression was observed with daily RAD001 combined with adjuvant TMZ at 200 mg/m2, but was better tolerated with TMZ dosed at 150 mg/m2 19. Thus, although an MTD was not reached, weekly RAD001 at 70 mg/dose is the recommended Phase 2 dose for use in combination with standard chemoradiotherapy in GBM.

Both RAD001 and TMZ are immunosuppressive agents associated with an increased risk of opportunistic infections. Consequently, prophylaxis for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) and gram negative organisms was required throughout therapy. This recommendation was based on excessive infectious risks observed in patients treated on a similar trial (N027D) testing temsirolimus combined with chemo-radiotherapy (manuscript submitted). Possibly due to the planned rigorous antibiotic regimen, no bacterial opportunistic infections were observed on the present trial. However, 2 patients developed viral opportunistic infections with re-activation of hepatitis B and development of herpes zoster, respectively. Although viral reactivation of latent hepatitis infections is a known risk during cancer chemotherapy,20 only one other case of hepatitis reactivation has been reported in a GBM patient 5 weeks after completing concomitant RT and TMZ21. Sirolimus and RAD001-containing immunosuppressive regimens have been used safely in hepatitis-infected transplant recipients with a relatively low risk of transaminitis and without overt elevation in hepatitis viral load 22–24. On the basis of these data, we hypothesize that the combined immune suppression from both temozolomide and RAD001 may place patients at increased risk for reactivation of a chronic hepatitis B or C infection, and patients positive for hepatitis antigen or serology are excluded from enrollment on the Phase 2 portion of this study.

Multiple pre-clinical studies demonstrate sensitizing effects of mTOR inhibitors in combination with radiation or temozolomide, although the mechanism of sensitization is unknown. Our group first demonstrated a marked in vivo sensitizing effect of sirolimus combined with protracted fractionated radiotherapy in U87 glioma xenografts despite no effect on intrinsic radiosensitivity in clonogenic assays 10. Consistent with sensitizing effect secondary to suppression of tumor repopulation, sirolimus combined with a condensed radiation schedule over 4 days was no more effective than radiation alone 25. Subsequently, several groups have demonstrated enhanced in vitro cytotoxicity of mTOR inhibitors and radiation on human endothelial cells and increased tumor vasculature disruption with combined mTOR inhibition and radiation 9, 26, 27. Additional data demonstrate at least additive effects of combined RAD001 and TMZ in glioma xenografts (unpublished data: Sarkaria laboratory and Novartis). On the basis of the cumulative pre-clinical efficacy data and the tolerability of the combination in the current study, the combination of RAD001 with standard chemoradiotherapy in GBM is now being tested in the Phase II portion of this clinical trial.

The dosing schedule used for RAD001 was based on prior clinical data, and designed to maximize penetration of the drug into the brain. In a Phase I study, both daily and weekly RAD001 were explored, and both regimens were well tolerated 18. Weekly dosing with 70 mg/dose was associated with almost a 3-fold higher maximum serum concentration (Cmax) and a 7-fold higher area under the curve exposure as compared to daily dosing at 10 mg/day. Consistent with sustained and essentially irreversible inhibition of mTORC1 signaling, p70S6 kinase activity in peripheral blood mononuclear cells was markedly suppressed for over 7 days with weekly RAD001 doses of 20 mg or greater. RAD001 is a known substrate for endothelial P-glycoprotein drug efflux pump 28, which contributes to blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity, and consistent with reduced penetration through the BBB, preliminary studies in mice demonstrated that a modest dose-escalation was required to robustly inhibit p70S6 kinase activity in normal brain as compared to peripheral tissues (unpublished data, Sarkaria laboratory). Since GBM cells infiltrate into regions of normal brain with an intact BBB, weekly RAD001 dosing was selected for this study based on the assumption that the higher Cmax would maximize suppression of mTOR signaling in tumor cells throughout the brain.

FDG PET imaging was incorporated into this trial around a 1 week run-in period of RAD001 treatment prior to initiation of radiation to test whether changes in FDG uptake could be used as a non-invasive pharmacodynamic marker for mTORC1 inhibition. Biochemical studies have demonstrated that PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling can play a central role in modulating glucose uptake29, 30, and preliminary data suggested that RAD001 suppressed FDG uptake regardless of inherent RAD001 sensitivity (data not shown). However, recently published pre-clinical studies suggest uniform suppression of FDG uptake in sensitive models but variable suppression in sirolimus-resistant tumors 30–33. Moreover, in a recent Phase I/II trial of sirolimus monotherapy, partial metabolic responses (PMR) were observed in 14 of 34 patients after 1 month of sirolimus therapy, but PET response did not correlate with radiographic disease response.33 These results are similar to the current clinical trial in which 4 of 18 patients had a PMR after only 1 week of RAD001 therapy. While these studies suggest that suppression of FDG uptake is not an adequate surrogate for mTORC1 inhibition, the relatively rapid metabolic response observed in a subset of tumors validates the concept that PET imaging can be used to detect relatively early changes in tumor metabolism induced by mTOR inhibition. The present clinical trial is not sufficiently powered to understand the clinical relevance of the observed metabolic changes or whether there is a relationship between change in SUVmax and dose or serum level of RAD001.

Limited pharmacokinetic (PK) sampling was performed on this trial to facilitate comparison of everolimus drug levels to PET imaging results. In previous studies, RAD001 serum levels peaked within 1–2 hours of intake, stabilized within 24 hours, and had a terminal half life of 30 hours 18, 34. At steady state, RAD001 cumulative exposure was proportional to dose for doses between 5–70 mg/week. Limited or no accumulation was observed between weekly doses of RAD001 18, 35. Consistent with these observations, 24 hour serum everolimus levels at a dose of 70 mg/week were significantly higher than at 30 mg/week on this trial. While there was a marginal association between initial RAD001 serum levels and change in SUVmax, more extensive characterization of RAD001 PK at steady-state levels would be required to more clearly understand the relationship between RAD001 exposure and changes in tumor FDG uptake.

CONCLUSIONS

The integration of weekly RAD001 therapy with standard chemo-radiotherapy in newly diagnosed GBM patients was reasonably well tolerated. Early FDG PET imaging after 1 week of RAD001 monotherapy demonstrated partial metabolic response in a subset of patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the expert clinical support provided by Sue Steinmetz and Debra Sprau, protocol development by Sara Braun, and biostatistical analysis by Sara Felton and Keith Anderson.

Footnotes

This study was conducted as a collaborative trial of the North Central Cancer Treatment Group and Mayo Clinic and was supported in part by Public Health Service grants: CA-25224, CA-37404, CA-35103, CA-114740 and Brain SPORE CA-108961 from the National Cancer Institute, Department of Health and Human Services. Funding also was provided by Novartis. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Health or Novartis.

Conflicts of Interest Notification. Funding was provided by Novartis in support of this clinical trial.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sandsmark DK, Pelletier C, Weber JD, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin: master regulator of cell growth in the nervous system. Histol Histopathol. 2007;22:895–903. doi: 10.14670/HH-22.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faivre S, Kroemer G, Raymond E. Current development of mTOR inhibitors as anticancer agents. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2006;5:671–688. doi: 10.1038/nrd2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao RD, Buckner JC, Sarkaria JN. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors as anti-cancer agents. Current Cancer Drug Targets. 2004;4:621–635. doi: 10.2174/1568009043332718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neshat MS, Mellinghoff IK, Tran C, et al. Enhanced sensitivity of PTEN-deficient tumors to inhibition of FRAP/mTOR. PNAS. 2001;98:10314–10319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171076798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choe G, Horvath S, Cloughesy TF, et al. Analysis of the phosphatidylinositol 3'-kinase signaling pathway in glioblastoma patients in vivo. Cancer Research. 2003;63:2742–2746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu X, Pandolfi PP, Li Y, et al. mTOR promotes survival and astrocytic characteristics induced by Pten/AKT signaling in glioblastoma. Neoplasia. 2005;7:356–368. doi: 10.1593/neo.04595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galanis E, Buckner JC, Maurer MJ, et al. Phase II Trial of Temsirolimus (CCI-779) in Recurrent Glioblastoma Multiforme: A North Central Cancer Treatment Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5294–5304. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.23.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang SM, Wen P, Cloughesy T, et al. Phase II study of CCI-779 in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Invest New Drugs. 2005;23:357–361. doi: 10.1007/s10637-005-1444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shinohara ET, Cao C, Niermann K, et al. Enhanced radiation damage of tumor vasculature by mTOR inhibitors. Oncogene. 2005;24:5414–5422. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eshleman J, Carlson B, Mladek A, et al. Inhibition of the Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Sensitizes U87 Xenografts to Fractionated Radiation Therapy. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7291–7297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinnberg T, Lasithiotakis K, Niessner H, et al. Inhibition of PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling sensitizes melanoma cells to cisplatin and temozolomide. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1500–1515. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovarik JM, Hartmann S, Figueiredo J, et al. Effect of rifampin on apparent clearance of everolimus. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:981–985. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuhn B, Jacobsen W, Christians U, et al. Metabolism of sirolimus and its derivative everolimus by cytochrome P450 3A4: insights from docking, molecular dynamics, and quantum chemical calculations. J Med Chem. 2001;44:2027–2034. doi: 10.1021/jm010079y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishnan S, Brown PD, Ballman KV, et al. Phase I trial of erlotinib with radiation therapy in patients with glioblastoma multiforme: results of North Central Cancer Treatment Group protocol N0177. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:1192–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young H, Baum R, Cremerius U, et al. Measurement of clinical and subclinical tumour response using [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography: review and 1999 EORTC recommendations. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) PET Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:1773–1782. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown PD, Krishnan S, Sarkaria JN, et al. Phase I/II Trial Erlotinib and Temozolomide With Radiation Therapy in the Treatment of Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma Multiforme: North Central Cancer Treatment Group Study N0177. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5603–5609. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarkaria JN, Schwingler P, Schild SE, et al. Phase I trial of sirolimus combined with radiation and cisplatin in non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2007;2:751–757. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3180cc2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Donnell A, Faivre S, Burris HA, 3rd, et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the oral mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1588–1595. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.0988. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mason WP, MacNeil M, Easaw J, et al. A phase I study of temozolomide (TMZ) and RAD001 in patients (pts) with glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2009;27:2036. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeo W, Zee B, Zhong S, et al. Comprehensive analysis of risk factors associating with Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1306–1311. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chheda MG, Drappatz J, Greenberger NJ, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation during glioblastoma treatment with temozolomide: a cautionary note. Neurology. 2007;68:955–956. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259430.48835.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vivarelli M, Vetrone G, Zanello M, et al. Sirolimus as the main immunosuppressant in the early postoperative period following liver transplantation: a report of six cases and review of the literature. Transpl Int. 2006;19:1022–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2006.00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Simone P, Carrai P, Precisi A, et al. Conversion to everolimus monotherapy in maintenance liver transplantation: feasibility, safety, and impact on renal function. Transpl Int. 2009;22:279–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2008.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang HR, Lin CC, Lian JD. Lack of hepatotoxicity upon sirolimus addition to a calcineurin inhibitor-based regimen in hepatitis virus-positive renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:1520–1522. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.02.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weppler SA, Krause M, Zyromska A, et al. Response of U87 glioma xenografts treated with concurrent rapamycin and fractionated radiotherapy: possible role for thrombosis. Radiother Oncol. 2007;82:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy JD, Spalding AC, Somnay YR, et al. Inhibition of mTOR Radiosensitizes Soft Tissue Sarcoma and Tumor Vasculature. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:589–596. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manegold PC, Paringer C, Kulka U, et al. Antiangiogenic therapy with mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor RAD001 (Everolimus) increases radiosensitivity in solid cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:892–900. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laplante A, Demeule M, Murphy GF, et al. Interaction of immunosuppressive agents rapamycin and its analogue SDZ-RAD with endothelial P-gp. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:3393–3395. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(02)03658-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taha C, Liu Z, Jin J, et al. Opposite translational control of GLUT1 and GLUT4 glucose transporter mRNAs in response to insulin. Role of mammalian target of rapamycin, protein kinase b, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in GLUT1 mRNA translation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33085–33091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.33085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shackelford DB, Vasquez DS, Corbeil J, et al. mTOR and HIF-1alpha-mediated tumor metabolism in an LKB1 mouse model of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11137–11142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900465106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cejka D, Kuntner C, Preusser M, et al. FDG uptake is a surrogate marker for defining the optimal biological dose of the mTOR inhibitor everolimus in vivo. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1739–1745. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei LH, Su H, Hildebrandt IJ, et al. Changes in Tumor Metabolism as Readout for Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Kinase Inhibition by Rapamycin in Glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3416–3426. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma WW, Jacene H, Song D, et al. [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography correlates with Akt pathway activity but is not predictive of clinical outcome during mTOR inhibitor therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2697–2704. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.8383. [see comment] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka C, O'Reilly T, Kovarik JM, et al. Identifying optimal biologic doses of everolimus (RAD001) in patients with cancer based on the modeling of preclinical and clinical pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1596–1602. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tabernero J, Rojo F, Calvo E, et al. Dose- and schedule-dependent inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway with everolimus: a phase I tumor pharmacodynamic study in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1603–1610. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5482. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]