Abstract

BACKGROUND

We sought to identify socioeconomic (SES) factors associated with adjuvant hormonal therapy (HT) use among a contemporary population of older breast cancer survivors.

METHODS

Telephone surveys were conducted among women (65–89 years) residing in 4 states (CA, FL, IL, NY) who underwent initial breast cancer surgery in 2003. Demographic, SES, and treatment information was collected.

RESULTS

Of the 2,191 women, 67% received adjuvant HT with either tamoxifen or an aromatase inhibitor (AI); 71% of these women were on an AI. When adjusting for multiple demographic and SES factors, predictors of HT use were: better education (high school degree or higher), better informational/emotional support, and younger age (65 – 79 years). Race/ethnicity, income, and insurance coverage for medication costs were not associated with receiving HT. For those on HT, when adjusting for all other factors, women were more likely to be treated with an AI if they had insurance coverage for some or all medication costs, were wealthier, had better informational/emotional support, and were younger (65 – 69 years).

CONCLUSIONS

The majority of older women in this population-based cohort received adjuvant HT and the adoption of AIs was early. Providers should be aware that a woman’s education level and support system influence her decision to take HT. Given the high cost of AIs, its benefits in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer, and our finding that women with no insurance coverage for medication costs were significantly less likely to receive an AI, we recommend that policy-makers address this issue.

Keywords: breast cancer, hormonal therapy, tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors, surgery

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 75% of postmenopausal women with breast cancer have hormone receptor-positive disease.1–3 For hormone receptor-positive disease, tamoxifen has been the gold standard of adjuvant hormonal therapy.4–6 In the last several years, several clinical trials have demonstrated the even greater effectiveness of adjuvant aromatase inhibitors (AIs) compared to tamoxifen in treating postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive disease.7–9 In 2005, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommended that adjuvant treatment for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer should include an AI.7 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and St. Gallen Consensus guidelines also incorporate AIs in the adjuvant therapy of postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer.8 However, AIs are more expensive than tamoxifen. In 2004, the annual estimated retail cost of an AI was $2,700 to $2,900 while the annual cost of tamoxifen was approximately $1,600.10

Several breast cancer studies have shown that women of lower socioeconomic status (SES) have worse survival compared to women with higher SES; this decrease in survival cannot be fully explained by disparities in the use of screening mammography, cancer stage at presentation and initial treatment (surgery, radiation and chemotherapy).11–16 We hypothesized that this survival difference could be due to women of lower SES being less likely to take hormonal therapy or, if they take hormonal therapy, less likely to use an AI. Decreased use in women with lower SES may be attributed to financial issues or a poorer understanding of the rationale to take hormonal therapy, in general, and specifically the more expensive AIs.

Currently, little is known about the factors that affect whether a patient with breast cancer receives adjuvant hormonal therapy and the extent to which AIs are being used.17–19 Investigations of this nature in population-based cohorts are limited since information on hormone receptor status and the receipt of hormonal therapy have not been routinely available in either tumor registry or administrative (Medicare claims) databases. Therefore, using a contemporary cohort of older community-dwelling women with breast cancer, we sought to determine to what extent tamoxifen and AIs are being used and to identify SES factors associated with the receipt of adjuvant hormonal therapy.

METHODS

The study sample consists of a population-based cohort of 3,083 female breast cancer survivors who are participating in a survey study examining breast cancer outcomes, as previously described.20, 21 In brief, community-dwelling women between the ages of 65 and 89 who reside in four geographically diverse states (California, Florida, Illinois and New York) were initially identified from Medicare claims as having had an incident breast cancer surgery during the period of March 2003 to October 2003, using our validated claims-based algorithm.22 The median time from surgery to the first interview was 33 months. For this study, we excluded 873 women with ductal carcinoma in situ or unknown stage information and 19 women with incomplete hormonal therapy information. Therefore, the study cohort consists of 2,191 women with invasive breast cancer and complete hormonal therapy information.

Data collected from this initial telephone survey included information on demographic, SES, and treatment factors. Additional hormonal therapy use information was collected from three subsequent survey waves, which ended in September 2008. Participants also gave informed consent for the use of their Medicare claims and state tumor registry information. Comorbidity scores were determined from Medicare claims using the methodology described by Klabunde.23 Tumor stage information, SEER Summary Stage 2000,24 was obtained from the four state tumor registries, which are members of the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries.25 Hormone receptor status information was only available in 26% of cases. This study was approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the institutional review boards of our institution and the four states.

Hormonal therapy definitions

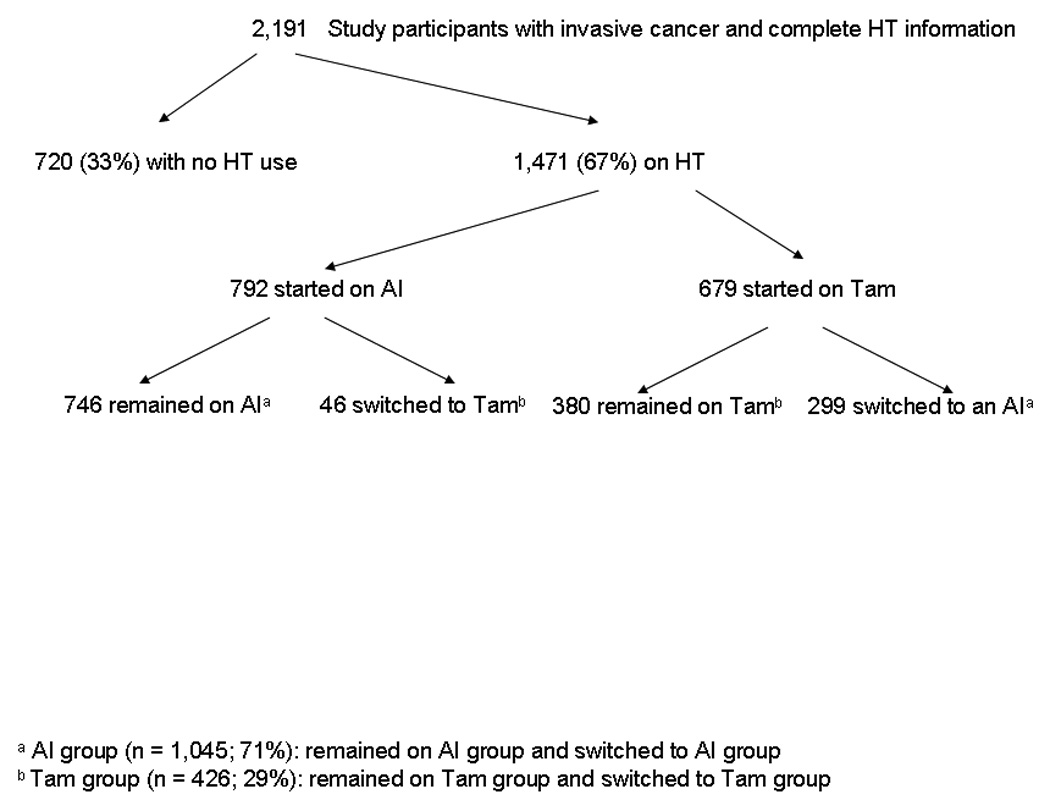

Receipt of hormonal therapy was defined as any hormonal therapy use with tamoxifen or an AI (anastrozole, letrozole, or exemestane) of any duration within one year of surgery. The one-year cut-off was chosen as this time frame is endorsed by the National Quality Forum as one of its breast cancer quality measures.26 Of the 2,191 women, 1,471 (67%) initiated adjuvant hormonal therapy within one year of surgery (Figure 1). Of the 792 women who started on an AI, 46 subsequently switched to tamoxifen during the study period, which ended in September 2008. Of the 679 women who started on tamoxifen, 299 (44%) switched to an AI during the study period. All women were subsequently condensed into two groups and categorized as having received: 1) adjuvant therapy with an AI or 2) adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen. The AI group (n = 1,045) consisted of women who only received an AI (n = 746) and women who switched from tamoxifen to an AI (n = 299). The tamoxifen group (n = 426) consisted of women who only received tamoxifen (n = 380) and women who switched from an AI to tamoxifen (n = 46). From the perspective of understanding determinants of ultimate hormonal therapy use, we chose to group the switchers based on the final drug received for two reasons: 1) the majority of switchers switched from tamoxifen to an AI, which would be clinically appropriate as suggested by the ASCO guidelines, 7 and 2) switching tended to occur early during the first few months of treatment.

Fig. 1.

Study cohort. Adjuvant hormonal therapy use was initiated within one year of surgery and additional hormonal therapy information was collected through September 2008. Abbreviations: AI, aromatase inhibitor; HT, hormonal therapy; Tam, tamoxifen.

Demographic and SES factors

Patient’s age and state geographic location were determined from Medicare files.22 All other variable information was obtained by survey response. Age was defined by four categories: 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, and 80–89. The race/ethnicity variable was categorized as “non-Hispanic white” and “other”. “Other” included Black or African American (n = 74), Hispanic or Latino (n = 73), and American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, or Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander (n = 62). Marital status was defined by four categories: married, widowed, divorced, and never married. “Married” was defined as married or living with a partner. “Divorced” was defined as separated or divorced.

Educational attainment was grouped into three categories based on years of education: less than high school, high school graduate or GED degree, and greater than high school (any post-high school education, 4-year college degree, professional or graduate degree). Women were asked to estimate their total household income in 2004. Income was categorized as: $15,000 or less, $15,001–$25,000, $25,001–$50,000, and greater than $50,000. Medication coverage was based on how much the cost of prescription medications was covered by Medicare and/or private health insurance plans and was defined by three categories: none of the cost, some of the cost, almost all to all of the cost.

Social support was assessed by the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Scale, which is a validated measure of patients’ perceptions of help and support available to them in various aspects of life.27, 28 Twelve questions were asked; eight were related to emotional/informational support (e.g. “someone to give you information to help you understand a situation”, “someone to turn to for suggestions about how to deal with a personal problem”) while four were related to tangible support around the time of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment (e.g. “someone to take you to the doctor if you needed it”). Answers to each item were determined using a 5-point Likert scale with 1 = none of the time and 5 = all of the time. Two subscale (emotional/informational and tangible) scores were then determined. For each subscale, quartiles were categorized based on the cohort’s distribution.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcomes were: 1) the receipt of any hormonal therapy, and 2) among those women initiating hormonal therapy, the type of hormonal therapy medication (tamoxifen vs. AI) received. Univariate testing for significant differences for these two outcomes according to baseline characteristics was performed. Differences in the distribution of characteristics were analyzed by the Pearson chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. A multiple logistic regression model was developed to determine those characteristics independently associated with the receipt of hormonal therapy, when simultaneously controlling for all 9 demographic and SES variables. Among the 1,471 women on hormonal therapy, a multiple logistic regression model was developed to determine those characteristics independently associated with the type of hormonal therapy medication received, when simultaneously controlling for all 9 sociodemographic variables. Point estimates from the model are reported as odds ratios (OR) along with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). For both outcomes, the predicted probabilities for each woman based on the logistic regression model were calculated and then averaged by either education level or insurance coverage for medication costs. Data analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software (Version 9.1, SAS Institute; Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The demographic and SES features of the cohort are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the women in 2003 was 73.0 years (sd = 5.5). Ninety-one percent were Caucasian and 50% were married. The cohort was fairly well distributed among the four states. Eighty-nine percent of women had completed at least a high school degree. The mean annual income of the cohort in 2004 was $38,284 and 79% had at least some insurance coverage for medication costs. More than half of the women in the cohort reported having social support available to them most or all of the time (score ≥ 4.0). The majority of the women were healthy (63% had a comorbidity score of 0) and had node-negative tumors (76%).

Table 1.

Demographic and socioeconomic features of the study cohort (n = 2,191)

| Demographic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 65 – 69 | 678 | 30.9 |

| 70 – 74 | 690 | 31.5 |

| 75 – 79 | 520 | 23.7 |

| 80 – 89 | 303 | 13.8 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1982 | 90.5 |

| Black | 74 | 3.4 |

| Hispanic | 73 | 3.3 |

| Other | 62 | 2.8 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1091 | 49.8 |

| Widowed | 771 | 35.2 |

| Divorced | 191 | 8.7 |

| Never married | 85 | 3.9 |

| Not answered | 53 | 2.4 |

| Geographic Location | ||

| California | 595 | 27.2 |

| Florida | 726 | 33.1 |

| Illinois | 399 | 18.2 |

| New York | 471 | 21.5 |

| Socioeconomic | ||

| Educational level | ||

| < High school | 183 | 8.3 |

| High school graduate | 735 | 33.5 |

| Some college | 625 | 28.5 |

| ≥ College degree | 591 | 27.0 |

| Not answered | 57 | 2.6 |

| Annual income ($) | ||

| 15,000 or less | 276 | 12.6 |

| 15,001 – 25,000 | 417 | 19.0 |

| 25,001 – 50,000 | 576 | 26.3 |

| More than 50,000 | 447 | 20.4 |

| Not answered | 475 | 21.7 |

| Medication coverage | ||

| None of the cost | 360 | 16.4 |

| Some of the cost | 764 | 34.9 |

| Almost all to all of the cost | 958 | 43.7 |

| Not answered | 109 | 5.0 |

| Tangible social support score | ||

| < 4.0 (least) | 629 | 28.7 |

| 4.1 – 4.75 | 481 | 22.0 |

| 4.76 – 5.0 (most) | 993 | 45.3 |

| All 4 items not answered | 88 | 4.0 |

| Emotional/informational social support score | ||

| < 3.5 (least) | 635 | 29.0 |

| 3.5 – 4.25 | 603 | 27.5 |

| 4.26 – 4.75 | 364 | 16.6 |

| 4.76 – 5.0 (most) | 506 | 23.1 |

| All 8 items not answered | 83 | 3.8 |

| Other | ||

| Comorbidity | ||

| 0 | 1378 | 63.0 |

| > 0 – 0.72 | 474 | 21.6 |

| > 0.72 | 224 | 10.2 |

| Missing | 115 | 5.2 |

| Tumor stage | ||

| Local | 1672 | 76.3 |

| Regional | 501 | 22.9 |

| Distant | 18 | 0.8 |

Factors associated with the receipt of hormonal therapy

Of the 2,191 study participants, 1,471 (67%) initiated adjuvant hormonal therapy with tamoxifen or an AI within one year after surgery. Of the 792 women who started on an AI, 72% were on anastrozole, 16% on letrozole, and 11% on exemestane. In the multivariate logistic regression model (Table 2), when adjusting for race, marital status, geographical location, income, insurance coverage for medication costs, and tangible social support, women were more likely to receive adjuvant hormonal therapy if they were better educated (high school graduate or higher education) or had more emotional/informational support. Women who were better educated had, on average, a 69% model-predicted probability of receiving hormonal therapy, compared to 57% among those without a high school degree. Women were less likely to receive adjuvant hormonal therapy if they were ≥ 80 years of age.

Table 2.

Factors associated with adjuvant hormonal therapy use in multivariate logistic regression analysis (n = 2,033)a

| OR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | < 0.01 | ||

| 65 – 69 | 1.00 | ||

| 70 – 74 | 0.87 | 0.68 – 1.10 | 0.26 |

| 75 – 79 | 0.92 | 0.70 – 1.20 | 0.55 |

| 80 – 89 | 0.56 | 0.41 – 0.77 | < 0.01 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.91 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.00 | ||

| Other | 1.02 | 0.73 – 1.43 | |

| Marital Status | 0.36 | ||

| Married | 1.00 | ||

| Widowed | 0.86 | 0.68 – 1.08 | 0.20 |

| Divorced | 0.85 | 0.59 – 1.21 | 0.37 |

| Never Married | 1.25 | 0.73 – 2.14 | 0.41 |

| Geographic Location | 0.16 | ||

| California | 1.00 | ||

| Illinois | 1.35 | 1.01 – 1.81 | 0.04 |

| New York | 1.23 | 0.94 – 1.62 | 0.14 |

| Florida | 1.06 | 0.83 – 1.36 | 0.62 |

| Educational Level | < 0.01 | ||

| < High school | 1.00 | ||

| High school graduate | 1.55 | 1.07 – 2.24 | 0.02 |

| > High school | 1.81 | 1.26 – 2.61 | < 0.01 |

| Annual Income ($) | 0.87 | ||

| 15,000 or less | 1.00 | ||

| 15,001 – 25,000 | 1.05 | 0.74 – 1.49 | 0.78 |

| 25,001 – 50,000 | 0.98 | 0.69 – 1.40 | 0.93 |

| More than 50,000 | 0.91 | 0.62 – 1.34 | 0.64 |

| Missing | 0.75 | 0.52 – 1.08 | 0.12 |

| Medication Coverage | 0.87 | ||

| None of the cost | 1.00 | ||

| Some of the cost | 0.93 | 0.71 – 1.23 | 0.61 |

| Almost all to all of the cost | 0.94 | 0.72 – 1.23 | 0.65 |

| Tangible Social Support | 0.22 | ||

| < 4.0 (least) | 1.00 | ||

| 4.0 – 5.0 (most) | 0.87 | 0.69 – 1.09 | |

| Emotional/Informational Support | 0.02 | ||

| < 3.5 (least) | 1.00 | ||

| 3.5 – 5.0 (most) | 1.30 | 1.03 – 1.63 | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio

Excludes 158 patients with missing information in any variable except income.

Comorbidity and tumor stage were not significant factors and were therefore not included in the model.

Factors associated with the type of hormonal therapy received

Of the 1,471 women on adjuvant hormonal therapy, 71% were on an AI and 29% were on tamoxifen (Figure 1). Estimates from a multivariate logistic regression model (Table 3) that also adjusted for race/ethnicity, marital status, geographic location, education level, and tangible support revealed that women were more likely to be treated with an AI if they had insurance coverage for medication costs, were wealthier (> $50,000 annual income), had better emotional/informational social support, and were younger (age 65 – 69). Women who had any insurance coverage for medication costs had, on average, a 73% model-predicted probability of receiving an AI, compared to 62% among those with no insurance coverage for medication costs.

Table 3.

Factors associated with AI versus tamoxifen use in multivariate logistic regression analysis (n = 1,379)a

| OR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | < 0.01 | ||

| 65 – 69 | 1.00 | ||

| 70 – 74 | 0.52 | 0.38 – 0.72 | < 0.01 |

| 75 – 79 | 0.57 | 0.40 – 0.80 | < 0.01 |

| 80 – 89 | 0.43 | 0.28 – 0.66 | < 0.01 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.66 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1.00 | ||

| Other | 1.10 | 0.72 – 1.70 | |

| Marital Status | 0.44 | ||

| Married | 1.00 | ||

| Widowed | 0.88 | 0.66 – 1.17 | 0.39 |

| Divorced | 1.08 | 0.68 – 1.73 | 0.74 |

| Never Married | 0.66 | 0.37 – 1.19 | 0.17 |

| Geographic Location | 0.12 | ||

| California | 1.00 | ||

| Florida | 1.23 | 0.89 – 1.69 | 0.21 |

| Illinois | 1.09 | 0.76 – 1.56 | 0.62 |

| New York | 1.52 | 1.06 – 2.18 | 0.02 |

| Educational Level | 0.60 | ||

| < High school | 1.00 | ||

| High school graduate | 0.78 | 0.46 – 1.31 | 0.34 |

| > High school | 0.84 | 0.50 – 1.41 | 0.51 |

| Annual Income ($) | 0.23 | ||

| 15,000 or less | 1.00 | ||

| 15,001 – 25,000 | 1.23 | 0.80 – 1.89 | 0.33 |

| 25,001 – 50,000 | 1.39 | 0.91 – 2.14 | 0.13 |

| More than 50,000 | 1.65 | 1.02 – 2.67 | 0.04 |

| Missing | 1.13 | 0.72 – 1.78 | 0.61 |

| Medication Coverage | < 0.01 | ||

| None of the cost | 1.00 | ||

| Some of the cost | 1.58 | 1.13 – 2.22 | < 0.01 |

| Almost all to all of the cost | 1.66 | 1.20 – 2.30 | < 0.01 |

| Tangible Social Support | 0.08 | ||

| < 4.0 (least) | 1.00 | ||

| 4.0 – 5.0 (most) | 0.77 | 0.58 – 1.03 | |

| Emotional/Informational Support | < 0.01 | ||

| < 3.5 (least) | 1.00 | ||

| 3.5 – 5.0 (most) | 1.58 | 1.19 – 2.10 | |

Abbreviations: AI, aromatase inhibitor; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio

Excludes 92 patients with missing information in any variable except income.

DISCUSSION

In this population-based study of 2,191 postmenopausal women with early stage breast cancer in 2003, 67% of women had received adjuvant hormonal therapy within one year of surgery. Women were more likely to receive hormonal therapy if they were better educated, had better informational/emotional support, and were younger. For those on hormonal therapy, women were more likely to be treated with an AI if they had insurance coverage for some or all medication costs, were wealthier, had better informational/emotional support, and were younger.

In December 2001, the initial results of the Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) trial were presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. At a median follow-up of 33 months, adjuvant anastrozole was superior to tamoxifen in terms of relapse-free survival.29 In January 2002, the NCCN endorsed anastrozole as “an alternative” to tamoxifen. However, it was not until 2005 that ASCO and St. Gallen each published guidelines recommending adjuvant AI use for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer and the FDA approved the adjuvant use of anastrozole.7, 8 In our study, 71% of women receiving adjuvant hormonal therapy were on an AI and over 80% of these women initiated AI use in 2003–2004. This finding confirms the results of previous studies demonstrating the substantial early adoption of AIs after the release of the initial ATAC results in December 2001, well prior to ASCO’s guideline publication in 2005.17, 19, 30 This rapid adoption of adjuvant AI use in the community is remarkable since, in the past, there has been a much slower adoption of other treatments (breast-conserving surgery) for breast cancer 31, 32 and to date, there is no overall survival advantage to using an AI, compared to tamoxifen.9

We found several independent predictors of adjuvant hormonal therapy use, including two SES factors: education and informational/emotional support (Table 2). The finding that better educated women (high school degree or higher) were more likely to receive any adjuvant hormonal therapy is not unexpected as discussions regarding the benefits and risks of hormonal therapy medications are extensive. Understanding and interpreting this information, believing the data supporting adjuvant hormonal therapy use, as well as weighing the pros and cons of these various medications may be more difficult for less educated women. Furthermore, women who have a more robust support system to seek advice and opinions may be better able to interpret and understand the benefits of hormonal therapy and be more comfortable deciding to take it. When a provider recommends adjuvant hormonal therapy, a woman may decide not to follow this advice for a variety of reasons; these two SES factors play a role in her decision. Interestingly, when adjusting for education and informational/emotional support, we found that race/ethnicity, income, insurance coverage for medication costs, and tangible social support were not associated with the receipt of hormonal therapy.

Our finding that relatively younger women (age 65–79 years) were more likely to receive adjuvant hormonal therapy is interesting since the indications for hormonal therapy are not age-related. Doctors and patients may be considering the possible risks/side effects associated with hormonal therapy (thromboembolic events, endometrial carcinoma, bone loss) more carefully in this older population. Our finding of geographic differences with hormonal therapy use is not surprising as there is much literature demonstrating the geographic variations in health care, and specifically, breast cancer care.32–36

Among women receiving hormonal therapy (Table 3), women were more likely to receive an AI if they had better informational/emotional support, had insurance coverage for medication costs, were wealthier (> $50,000 annual income), and were younger (age 65–69). Less AI use in relatively older women may be because both doctors and patients are particularly concerned with the possibility of additional bone loss associated with AI use and the potential morbidity of bony fractures in these older women. Women with more opportunities to discuss treatment decisions may ultimately come to value and believe in the benefits of an AI as opposed to tamoxifen more so than women with less informational/emotional support.

We found that wealthier women (>$50,000 annual income) and, most strikingly, women with any insurance coverage for medication costs were more likely to receive an AI as opposed to tamoxifen. This is not an unexpected finding given the markedly higher cost of AIs compared to tamoxifen. The fact that the lack of insurance coverage for medication costs was an important factor regarding type of hormonal therapy (AI versus tamoxifen) received has health care policy implications. Postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer with no insurance coverage for medication costs may not be receiving an AI because of the financial burden associated with these medications.37 The most recent ATAC data, at a median of 100 months of follow-up, continues to clearly show long-term efficacy of anastrozole compared with tamoxifen.9 For more postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer to derive benefit from adjuvant AI therapy, the review and possible revision of Medicare Part D and other insurance policies regarding AI coverage should be considered.

There are inherent limitations/biases with a survey study. In addition, our cohort is largely non-Hispanic white, due in part to the underlying racial distribution of the Medicare population in these four states as well as the predilection of breast cancer for Caucasian women; therefore, racial/ethnicity differences with hormonal therapy use may not be evident in our study. Another limitation is that women with the lowest income status will often have Medicaid pharmaceutical coverage. The fact that we found no association with income status and the initiation of hormonal therapy may be explained by this relationship. We also did not control for other non-Medicare insurance coverage.

We did not have hormone receptor status information from the state tumor registries in the majority of women. However, we can presume that approximately 75% of these postmenopausal women have hormone receptor-positive breast cancer.2, 3 Therefore, a relatively small proportion of women who might have been eligible for hormonal therapy did not receive it. This finding is encouraging as previous population-based studies have shown that only 50%-78% of older women with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer received adjuvant tamoxifen therapy.38–41 Finally, our study is limited to women 65 years of age and older and therefore our findings may not be generalizable to younger postmenopausal women. However, performing this survey study in Medicare patients allowed for the analysis of several demographic and SES factors associated with hormonal therapy use in a large population-based cohort. To our knowledge, no other study addressing these particular issues has been performed. Two studies have found no differences in tamoxifen use between women of diverse education levels and SES backgrounds;15, 16 however, these studies were performed in countries (United Kingdom and Sweden) that have national health insurance coverage, unlike in the United States. Furthermore, no studies have examined potential differences in AI therapy use.

In summary, our results show that SES-related differences in hormonal therapy use exist and raise the possibility that SES-related survival disparities could be partially due to differences in hormonal therapy use. In this population-based cohort of older breast cancer survivors, almost all women eligible for hormonal therapy received it and the adoption of adjuvant AI therapy was early. Better-educated women (high school degree or higher) and women with better informational/emotional support were more likely to receive hormonal therapy, especially an AI. When counseling women about hormonal therapy, providers should be aware that these two factors play a role in a woman’s decision to take hormonal therapy. Surprisingly, other SES factors (race/ethnicity, income status, and insurance coverage for medication costs) did not affect hormonal therapy use in this cohort. However, for women on hormonal therapy, those with no insurance coverage for medication costs were significantly less likely to receive an AI than women who had at least some medication coverage. Given this finding, the continued high cost of AIs and the clear benefits of adjuvant AI use in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer, we recommend that policy-makers address this issue.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant Numbers K07CA125586 and R01CA81379 from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 3rd Annual Academic Surgical Congress, Huntington Beach, CA, February 13, 2008.

There are no financial disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Lane DS, et al. Predicting risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women by hormone receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(22):1695–1705. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colditz GA, Rosner BA, Chen WY, Holmes MD, Hankinson SE. Risk factors for breast cancer according to estrogen and progesterone receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(3):218–228. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nattinger AB, Laud PW, Sparapani RA, Zhang X, Neuner JM, Gilligan MA. Exploring the surgeon volume outcome relationship among women with breast cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(18):1958–1963. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.18.1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Tamoxifen for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 1998;351(9114):1451–1467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference statement: adjuvant therapy for breast cancer, November 1–3, 2000. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2001;(30):5–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365(9472):1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winer EP, Hudis C, Burstein HJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology technology assessment on the use of aromatase inhibitors as adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: status report 2004. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(3):619–629. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlson RW, Hudis CA, Pritchard KI. Adjuvant endocrine therapy in hormone receptor-positive postmenopausal breast cancer: evolution of NCCN, ASCO, and St Gallen recommendations. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006;4(10):971–979. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2006.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forbes JF, Cuzick J, Buzdar A, Howell A, Tobias JS, Baum M. Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 100-month analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(1):45–53. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hewitt ME, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Translation. Committee on Cancer Survivorship: Improving Quality Care and Quality of Life, National Cancer Policy Board. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bigby J, Holmes MD. Disparities across the breast cancer continuum. Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16(1):35–44. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-1263-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Race, socioeconomic status, and breast cancer treatment and survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(7):490–496. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.7.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byers TE, Wolf HJ, Bauer KR, et al. The impact of socioeconomic status on survival after cancer in the United States: findings from the National Program of Cancer Registries Patterns of Care Study. Cancer. 2008;113(3):582–591. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peek ME, Han JH. Disparities in screening mammography. Current status, interventions and implications. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):184–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Downing A, Prakash K, Gilthorpe MS, Mikeljevic JS, Forman D. Socioeconomic background in relation to stage at diagnosis, treatment and survival in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;96(5):836–840. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eaker S, Halmin M, Bellocco R, et al. Social differences in breast cancer survival in relation to patient management within a National Health Care System (Sweden) Int J Cancer. 2009;124(1):180–187. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buzdar A, Macahilig C. How rapidly do oncologists respond to clinical trial data? Oncologist. 2005;10(1):15–21. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aiello EJ, Buist DS, Wagner EH, et al. Diffusion of aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer therapy between 1996 and 2003 in the Cancer Research Network. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(3):397–403. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9558-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chlebowski RT. Clinical trial presentations, agency guidelines, and oncology practice: findings from the arimidex, tamoxifen, alone or in combination trial. Clin Breast Cancer. 2008;8(4):343–346. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2008.n.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yen TW, Fan X, Sparapani R, Laud PW, Walker AP, Nattinger AB. A contemporary, population-based study of lymphedema risk factors in older women with breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(4):979–988. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0347-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nattinger AB, Pezzin LE, Sparapani RA, Neuner JM, King TK, Laud PW. Heightened attention to medical privacy: challenges for unbiased sample recruitment, and one solution. Am J Epidemiol. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq220. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nattinger AB, Laud PW, Bajorunaite R, Sparapani RA, Freeman JL. An algorithm for the use of Medicare claims data to identify women with incident breast cancer. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(6 Pt 1):1733–1749. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klabunde CN, Legler JM, Warren JL, Baldwin LM, Schrag D. A refined comorbidity measurement algorithm for claims-based studies of breast, prostate, colorectal, and lung cancer patients. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(8):584–590. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results. [accessed January 27, 2009];SEER Summary Staging Manual - 2000. Available from URL: http://seer.cancer.gov/tools/ssm/

- 25.The North American Association of Central Cancer Registries, Inc. [accessed January 27, 2009]; Available from URL: http://www.naaccr.org.

- 26.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. ASCO/NCCN Quality Measures: Breast and Colorectal Cancer. [accessed January 27, 2009]; Available from URL: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/quality_measures/default.asp.

- 27.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.RAND Health. Medical Outcomes Study: Social Support Survey. [accessed January 27, 2009]; Available from URL: http://www.rand.org./health/surveys_tools/mos/mos_socialsupport.html.

- 29.Baum M. The ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) adjuvant breast cancer trial in postmenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;69:210. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Svahn TH, Niland JC, Carlson RW, et al. Predictors and temporal trends of adjuvant aromatase inhibitor use in breast cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7(2):115–121. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lazovich D, Solomon CC, Thomas DB, Moe RE, White E. Breast conservation therapy in the United States following the 1990 National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference on the treatment of patients with early stage invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86(4):628–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nattinger AB, Gottlieb MS, Veum J, Yahnke D, Goodwin JS. Geographic variation in the use of breast-conserving treatment for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(17):1102–1107. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204233261702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baicker K, Chandra A, Skinner JS. Geographic variation in health care and the problem of measuring racial disparities. Perspect Biol Med. 2005;48(1 Suppl):S42–S53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baicker K, Chandra A, Skinner JS, Wennberg JE. Who you are and where you live: how race and geography affect the treatment of medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.var.33. Suppl Web Exclusives:VAR33-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farrow DC, Hunt WC, Samet JM. Geographic variation in the treatment of localized breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(17):1097–1101. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204233261701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guadagnoli E, Weeks JC, Shapiro CL, Gurwitz JH, Borbas C, Soumerai SB. Use of breast-conserving surgery for treatment of stage I and stage II breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(1):101–106. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pezzin LE, O'Niel MB, Nattinger AB. The economic consequences of breast cancer adjuvant hormonal treatments. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24 Suppl 2:S446–S450. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harlan LC, Clegg LX, Abrams J, Stevens JL, Ballard-Barbash R. Community-based use of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early-stage breast cancer: 1987–2000. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(6):872–877. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.5840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silliman RA, Guadagnoli E, Rakowski W, et al. Adjuvant tamoxifen prescription in women 65 years and older with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(11):2680–2688. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harlan LC, Abrams J, Warren JL, Clegg L, Stevens J, Ballard-Barbash R. Adjuvant therapy for breast cancer: practice patterns of community physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(7):1809–1817. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mariotto AB, Feuer EJ, Harlan LC, Abrams J. Dissemination of adjuvant multiagent chemotherapy and tamoxifen for breast cancer in the United States using estrogen receptor information: 1975–1999. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2006;(36):7–15. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgj003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]