SUMMARY

There are over 350 million people chronically infected with the Hepatitis B virus (HBV); chronic HBV infections are associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). While the precise mechanism of HBV-associated HCC remains undefined, it is believed to involve a combination of the host immune response to infection and activities of HBV proteins including the nonstructural X protein (HBx). HBx is a multifunctional protein that can modulate various cellular processes including cell proliferation. The exact effect of HBx on cell proliferation has varied depending on the cell line and exact conditions used in the study. Our previously published reports have demonstrated that HBx modulates the levels of cell cycle regulatory proteins in primary rat hepatocytes; however, the effect of HBx on cell cycle regulatory proteins in primary human hepatocytes, the natural host for HBV infection, has not been studied. Here we have examined the effect of HBx on cell cycle regulatory proteins in cultured, primary human hepatocytes. We demonstrate that HBx decreases the levels of cell cycle proteins that prevent progression into G1 phase and increases the levels of cell cycle proteins active in G1 phase. We have also shown that HBx modulation of cell cycle regulatory proteins requires cytosolic calcium, similar to the results we previously obtained in primary rat hepatocytes. Cumulatively, our results are the first demonstration that HBx modulates the levels of cell cycle regulatory proteins in a calcium-dependent manner in primary human hepatocytes.line n

Keywords: calcium, cell cycle, HBx, Hepatitis B virus, primary human hepatocytes

Globally, it is estimated that 350 million people are chronically infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) (reviewed in (Seeger et al., 2007)). Approximately 25% of chronically HBV-infected individuals will develop hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the third highest death-associated cancer worldwide (Seeger et al., 2007; WHO, 2008); however, the precise mechanism underlying HBV-associated HCC remains undefined. HBV encodes a partially double-stranded DNA genome that contains four open reading frames (ORFs) which encode the viral polymerase/reverse-transcriptase, core protein, surface antigen, and the nonstructural X protein (HBx) (reviewed in (Seeger et al., 2007)). Activities of HBV proteins, including HBx, in combination with the immune response to infection, are believed to be involved in the development of HBV-associated HCC.

HBx is a 17kD protein with many described activities; HBx is important for HBV replication and can regulate cellular transcription, protein degradation, proliferation, and apoptotic signaling pathways (reviewed in (Bouchard and Schneider, 2004)). Studies have also demonstrated that the activities of HBx likely contribute to the development of HBV-associated HCC (reviewed in (Bouchard and Schneider, 2004; Seeger et al., 2007)). Several studies in HBx-transgenic mice suggest that HBx plays at least a co-factor role in the development of HCC (Kim et al., 1991; Koike et al., 1998; Madden et al., 2001; Slagle et al., 1996; Terradillos et al., 1997; Yu et al., 1999; Zhu et al., 2004). Although the exact contribution of HBx activities to HCC development is unknown, it may involve regulation of several cell processes including cell proliferation and apoptosis.

The effect of HBx on cell proliferation pathways has been studied in various models and under different conditions with varying results (reviewed in (Madden and Slagle, 2001)). HBx can regulate the levels of several cell cycle regulatory proteins including p16, p21, p27, cyclin D1, cyclin A, and cyclin B1, activate the p21 promoter, and increase the activity of cyclin dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) (Ahn et al., 2001; Bouchard et al., 2001; Chin et al., 2007; Han et al., 2002; Leach et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2002; Mukherji et al., 2007; Park et al., 2006; Park et al., 2000; Qiao et al., 2001). Most previous studies were performed in transformed or immortalized cell lines, often not of liver origin. Few studies have examined the effect of HBx in primary hepatocytes, and no studies have examined the effect of HBx on cell proliferation pathways in primary human hepatocytes, the natural host for an HBV infection. Our previously published reports have demonstrated that HBx modulates cell proliferation pathways in primary rat hepatocytes; HBx induced normally quiescent rat hepatocytes to exit G0 phase, and enter, but stall in, G1 phase of the cell cycle (Gearhart and Bouchard, 2010a). We also showed that HBx modulation of cell proliferation pathways was dependent on cytosolic calcium signaling, and that modulation of these pathways was required for HBV replication in cultured, primary rat hepatocytes (Gearhart and Bouchard, 2010a; Gearhart and Bouchard, 2010b). However, although primary rat hepatocytes provide a biologically relevant model system to study the biology of HBV, human hepatocytes are the natural host for HBV, and differences between the two model systems may exist.

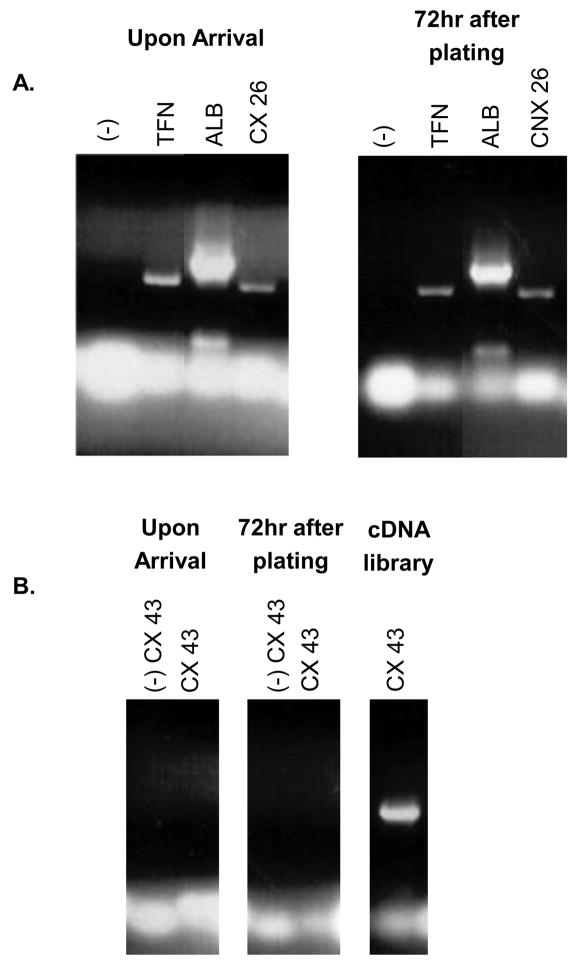

Primary human hepatocytes were purchased in suspension from the University of Pittsburgh, through the Liver Tissue Procurement and Distribution System (LTPAD). The hepatocytes were plated on collagen-coated tissue culture plates at approximately 1.5×106 cells/35mm plate (~80% confluent). These hepatocytes were maintained in Williams E medium supplemented with 2.0mM L-glutamine, 1.0mM sodium pyruvate, 4.0μg/mL Insulin/Transferrin/Selenium (ITS), 5.0μg/mL hydrocortisone, 5.0ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF), 10μg/mL gentamycin, and 2% Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) and maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 (Goyak et al., 2008). Cultured, human hepatocytes were monitored for maintenance of normal hepatocyte morphology and expression of specific markers of differentiated hepatocytes. To confirm that the hepatocytes maintained expression of differentiated hepatocyte-specific markers, RNA was isolated using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), reverse-transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (BioRad), and sequences of specific mRNAs were amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR); see Table 1 for primer sequences. Transferrin (TFN), albumin (ALB), and connexin 26 (CX26) were used as accepted markers of differentiated hepatocytes (Block et al., 1996; Zhang and Thorgeirsson, 1994). In addition, expression of connexin 43 (CX43), a marker present in liver sinusoid endothelial cells, Kupffer cells, and stellate cells, but not present in differentiated hepatocytes, was used to determine the purity of hepatocytes upon arrival and throughout the time course of our studies (Zhang and Thorgeirsson, 1994). Hepatocyte-specific markers were expressed immediately following isolation, and in hepatocytes that were maintained in culture for 72 hours, the time frame for our longest experiments (Figure 1A). Expression of CX43 was not detected in hepatocytes upon arrival or in hepatocytes that were cultured for 72 hours (Figure 1B). A human total liver cDNA library (BioChain Institute, Inc.) was used as a positive control for CX43 expression (Figure 1B). The results of these studies indicate that cultured, primary human hepatocytes maintained their differentiated status throughout the time course of our studies and contained undetectable levels of contamination with other liver cell types. Consistent with the differentiated status of the cultured primary human hepatocytes, replication of the hepatocytes was not observed during the time course of our experiments and hepatocytes could be maintained for 10 days in culture without a noticeable impact on cell number, morphology, or viability (data not shown).

Table 1.

Primer sequences of markers specific for differentiated human hepatocytes

| Marker | Forward Primer (5′ → 3′) | Reverse Primer (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|---|

| TFN | GCAAGCTTCGGGTCTAGGCAGGTCCG | CGGATCCGCATCCATCCTGGGGGGG |

| ALB | GCAAGCTTCCCCCGATTGGTGAGACC | CGGATCCGATCTGCAGCGGCACAGC |

| CX26 | GCAAGCTTGCACGCTGCAGACGATCC | CGGATCCCAGTCTTCTCCGTGGGCC |

| CX43 | GCAAGCTTCTGGGGACAGCGGTTGAG | CGGATCCGGTTGGTGAGGAGCAGCC |

Figure 1. Confirmation of differentiated primary human hepatocytes.

(A-B) RNA was extracted from hepatocytes upon arrival or hepatocytes cultured for 72 hours. RNA was then reverse-transcribed and PCR-amplified using primers specific for transferrin (TFN), albumin (ALB), connexin 26 (CX26), or connexin 43 (CX43). Expected band sizes are 574 base pairs (bp) for TFN, 761 bp for ALB, 618 bp for CX26, and 717 bp for CX43. A human total liver cDNA library (BioChain Institute, Inc.) was used as the positive control for CX43. (-) signifies samples where isolated RNA was directly PCR amplified, without undergoing the reverse transcription step, to confirm the absence of DNA contamination. Results shown are representative samples from experiments performed in duplicate from three human donors.

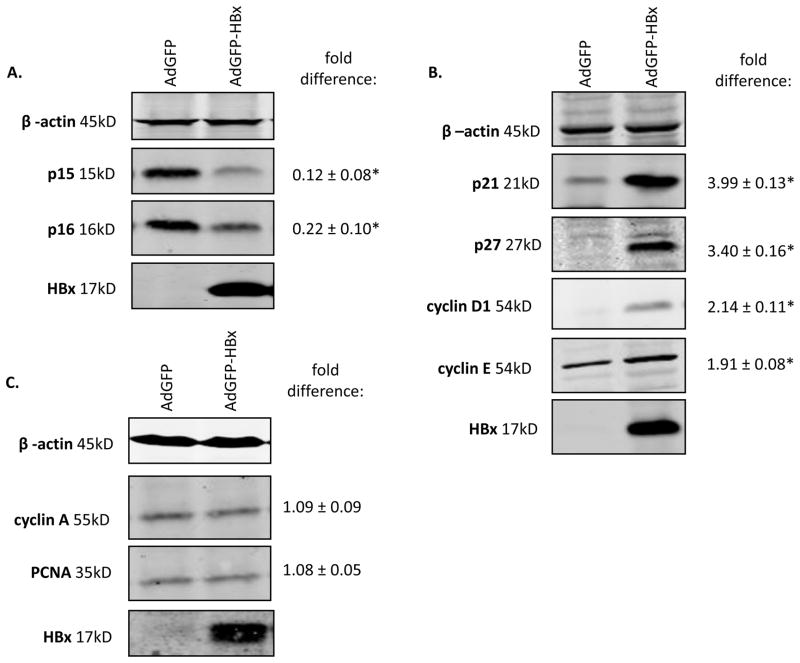

Due to low DNA transfection efficiency in primary human hepatocytes, these cells were infected with green fluorescent protein- (GFP) or GFP-HBx-encoding replication defective recombinant adenoviruses, AdGFP and AdGFP-HBx respectively; GFP and HBx are independently expressed from AdGFP-HBx (Clippinger et al., 2009). The titers of AdGFP or AdGFP-HBx were determined in Ad293 cells, and primary human hepatocytes were infected at a multiplicity of infection that ensured that 100% of the hepatocytes were infected as previously described for our studies in cultured primary rat hepatocytes (Clippinger et al., 2009). Because all the recombinant adenoviruses encode GFP, GFP expression was visually monitored to ensure that the infection efficiency was equivalent in all samples. 48 hours following recombinant adenovirus infection, we examined the effect of HBx on the levels of p15, p16, p21, p27, cyclin D1, cyclin E, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), and cyclin A using our previously described Western blot analysis protocol (Gearhart and Bouchard, 2010a). Equal loading of protein was confirmed by analysis of β-actin levels. All protein levels were first normalized to β-actin and then fold differences were determined by dividing the intensity of the protein in either the AdGFP-HBx lanes by the intensity in the AdGFP lanes using the quantitative, Odyssey® Infrared Imaging System (Licor® Biosciences). HBx decreased the levels of p15 and p16, proteins that inhibit entry into G1 phase of the cell cycle (Figure 2A). HBx increased the levels of active G1 phase proteins including cyclin D1, cyclin E, p21, and p27 (Figure 2B). Additionally, HBx had no effect on the levels of S phase proteins cyclin A and PCNA, suggesting that HBx-expressing cultured primary human hepatocytes do not progress into S phase (Figure 2C). These results demonstrate that HBx modulates human hepatocyte proliferation pathways to decrease factors that maintain hepatocyte quiescence (p15 and p16), elevate G1 phase factors (cyclin D1, p21, and p27), and elevate proteins that prevent progression into S phase (p21 and p27), similar to our previous observations in cultured primary rat hepatocytes (Gearhart and Bouchard, 2010a).

Figure 2. HBx modulates cell cycle regulatory proteins in primary human hepatocytes.

Primary human hepatocytes were infected with AdGFP and AdGFP-HBx recombinant adenoviruses and collected 48 hours post-infection. Lysates were resolved via SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western blot analysis for (A-C) β-actin, HBx, p15, p16, p21, p27, cyclin D1, cyclin E, cyclin A, and PCNA. Results shown are representative samples from independent experiments performed in duplicate in hepatocytes from six human donors. *fold difference plus/minus standard error between AdGFP-HBx and AdGFP was statistically significant as determined using a Student’s t-test (p≤0.05).

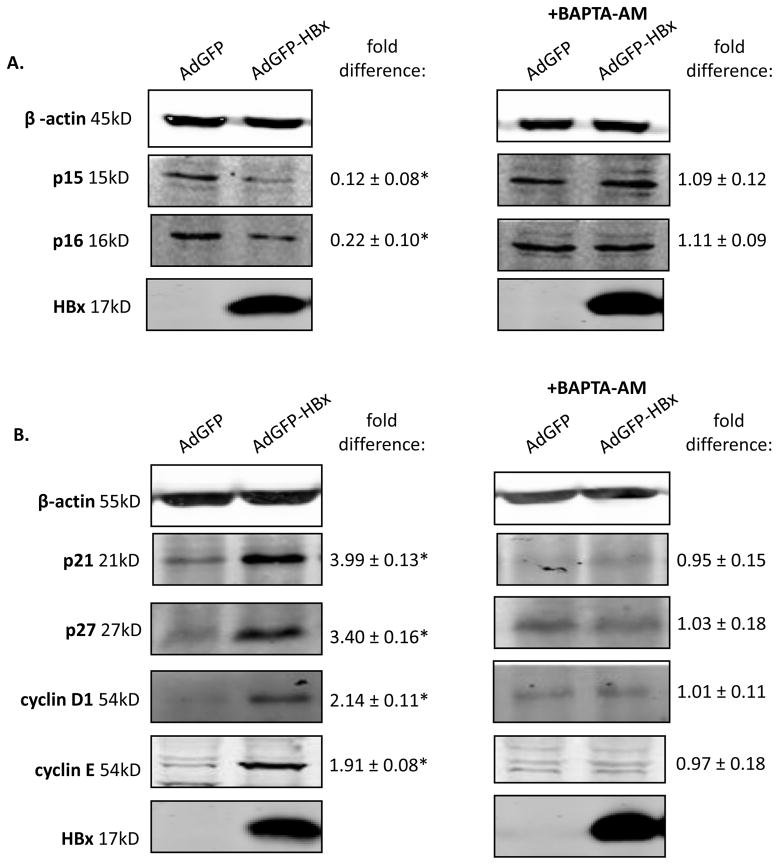

We previously demonstrated that cytosolic calcium signaling is required for modulation of cell proliferation pathways in primary rat hepatocytes (Gearhart and Bouchard, 2010a). Cytosolic calcium signaling is also required for HBV replication in both HepG2 cells and primary rat hepatocytes (Gearhart and Bouchard, 2010b; McClain et al., 2007). Because cytosolic calcium signaling is required for HBx modulation of cell proliferation pathways in primary rat hepatocytes, we examined whether cytosolic calcium signaling was also involved in HBx modulation of cell proliferation pathways in primary human hepatocytes. Hepatocytes were infected with AdGFP or AdGFP-HBx, treated with 50μM BAPTA-AM (1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid-tetraacetoxymethyl ester; Invitrogen) 24 hours post-infection, collected 24 hours after treatment, and the levels of the cell cycle regulatory proteins p15, p16, p21, p27, cyclin D1, and cyclin E were examined. Treatment with BAPTA-AM inhibited the ability of HBx to decrease the levels of p15 and p16, and inhibited HBx-induced increases in the levels of p21, p27, cyclin D1 and cyclin E (Figure 3A–B). These results suggest that HBx requires cytosolic calcium signaling to modulate cell proliferation pathways in primary human hepatocytes. This is similar our previous observations in cultured, primary rat hepatocytes (Gearhart and Bouchard, 2010a). Whether cytosolic calcium directly or indirectly impacts HBx regulation of cell cycle proliferation pathways in human hepatocytes has not yet been determined; our studies that included BAPTA-AM treatment confirm the importance of calcium signaling in HBx regulation of cell cycle progression but do not yet specify if this is a direct or indirect effect.

Figure 3. HBx requires cytosolic calcium signaling to modulate cell cycle regulatory proteins in primary hepatocytes.

Primary human hepatocytes were infected with AdGFP or AdGFP-HBx recombinant adenoviruses, treated with 50μM BAPTA-AM 24 hours post-infection, and collected 24 hours post-treatment. Lysates were resolved via SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western blot analysis for (A-B) β-actin, HBx, p15, p16, p21, p27, cyclin D1, and cyclin E. Results shown are representative samples from independent experiments performed in duplicate in hepatocytes from 3 human donors. *fold difference plus/minus standard error between AdGFP-HBx and AdGFP was statistically significant as determined using a Student’s t-test (p≤0.05).

The studies described here are the first demonstration that HBx modulates cell proliferation pathways in cultured, primary human hepatocytes and the first evidence that cytosolic calcium signaling is involved in HBx activities in normal human hepatocytes. An important observation of these studies is the similarities between results observed in cultured primary rat and human hepatocytes. The observation of similar consequences of HBx expression in both systems validates the use of rat hepatocytes as an alternative model for human hepatocytes, which are not readily available and difficult to acquire in large amounts. In addition, although the results described here are from studies in which HBx is expressed at higher levels than would be observed in the context of HBV replication, and from a recombinant adenovirus, because these results are similar to our previous observations in primary rat hepatocytes when HBx was expressed from a transfected, HBx-expression plasmid, AdGFP-HBx, or in the context of HBV replication, it is unlikely that our observations in cultured primary human hepatocytes are an artifact of using recombinant adenoviruses or HBx over expression (Gearhart and Bouchard, 2010a; Gearhart and Bouchard, 2010b). However, a direct confirmation of similar findings in human hepatocytes with HBx expressed in the context of HBV replication awaits analyses in HBV-infected human hepatocytes as compared to human hepatocytes infected with a mutant HBV that does not express HBx. Consequently, in future studies, we will analyze the effect of HBx on human hepatocyte proliferation pathways when HBx is expressed in the context of HBV replication. While it is likely that similar HBx activities will be apparent in the context of HBV replication in human hepatocytes, it is possible that other HBV proteins contribute to HBx regulation of cell cycle factors. However, because many HBV-associated tumors continue to express HBx in the absence of other viral proteins or HBV replication (Seeger et al., 2007), characterizing HBx activities when HBx is expressed in the absence of other HBV proteins could also identify mechanisms of HBV-associated HCC. We previously observed that HBx-induced entry into G1 and HBx-induced G1 arrest are required for HBV replication in primary rat hepatocytes (Gearhart and Bouchard, 2010a; Gearhart and Bouchard, 2010b). We anticipate that a similar HBx function will be required for HBV replication in cultured, primary human hepatocytes. Overall, studies of HBx activities in cultured primary human and rat hepatocytes provide biologically relevant models for identifying HBx activities that regulate HBV replication and may play a role in the development of HBV-associated HCC.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Adams, Olimpia Meucci, Eishi Noguchi and Laura Steel for continued discussions and advice. This work was supported by NIH grants R01AI064844 to M.J.B and 1 F31 AA017811-01 to T.L.G.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahn JY, Chung EY, Kwun HJ, Jang KL. Transcriptional repression of p21(waf1) promoter by hepatitis B virus X protein via a p53-independent pathway. Gene. 2001;275(1):163–8. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00604-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block GD, Locker J, Bowen WC, Petersen BE, Katyal S, Strom SC, Riley T, Howard TA, Michalopoulos GK. Population expansion, clonal growth, and specific differentiation patterns in primary cultures of hepatocytes induced by HGF/SF, EGF and TGF alpha in a chemically defined (HGM) medium. J Cell Biol. 1996;132(6):1133–49. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.6.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard M, Giannakopoulos S, Wang EH, Tanese N, Schneider RJ. Hepatitis B virus HBx protein activation of cyclin A-cyclin-dependent kinase 2 complexes and G1 transit via a Src kinase pathway. J Virol. 2001;75(9):4247–57. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.9.4247-4257.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard MJ, Schneider RJ. The enigmatic X gene of hepatitis B virus. J Virol. 2004;78(23):12725–34. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.12725-12734.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin R, Earnest-Silveira L, Koeberlein B, Franz S, Zentgraf H, Dong X, Gowans E, Bock CT, Torresi J. Modulation of MAPK pathways and cell cycle by replicating hepatitis B virus: factors contributing to hepatocarcinogenesis. J Hepatol. 2007;47(3):325–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clippinger AJ, Gearhart TL, Bouchard MJ. Hepatitis B virus X protein modulates apoptosis in primary rat hepatocytes by regulating both NF-kappaB and the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J Virol. 2009;83(10):4718–31. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02590-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhart TL, Bouchard MJ. The Hepatitis B Virus X Protein Modulates Hepatocyte Proliferation Pathways to Stimulate Viral Replication. J Virol. 2010a;84(6):2675–86. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02196-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhart TL, Bouchard MJ. Replication of the hepatitis B virus requires a calcium-dependent HBx-induced G1 phase arrest of hepatocytes. Virology. 2010b doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyak KM, Johnson MC, Strom SC, Omiecinski CJ. Expression profiling of interindividual variability following xenobiotic exposures in primary human hepatocyte cultures. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;231(2):216–24. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han HJ, Jung EY, Lee WJ, Jang KL. Cooperative repression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 gene expression by hepatitis B virus X protein and hepatitis C virus core protein. FEBS Lett. 2002;518(1–3):169–72. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Koike K, Saito I, Miyamura T, Jay G. HBx gene of hepatitis B virus induces liver cancer in transgenic mice. Nature. 1991;353:317–320. doi: 10.1038/351317a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike K, Moriya K, Yotsuyanagi H, Shintani Y, Fujie H, Tsutsumi T, Kimura S. Compensatory apoptosis in preneoplastic liver of a transgenic mouse model for viral hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 1998;134(2):181–6. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(98)00252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach JK, Qiao L, Fang Y, Han SL, Gilfor D, Fisher PB, Grant S, Hylemon PB, Peterson D, Dent P. Regulation of p21 and p27 expression by the hepatitis B virus X protein and the alternate initiation site X proteins, AUG2 and AUG3. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18(4):376–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.02990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Tarn C, Wang WH, Chen S, Hullinger RL, Andrisani OM. Hepatitis B virus X protein differentially regulates cell cycle progression in X-transforming versus nontransforming hepatocyte (AML12) cell lines. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(10):8730–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden C, Finegold M, Slagle B. Hepatitis B virus X protein acts a a tumor promoter in development of diethylnitrosamine-induced preneoplastic lesions. J Virol. 2001;75:3851–3858. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3851-3858.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden CR, Slagle BL. Stimulation of cellular proliferation by hepatitis B virus X protein. Dis Markers. 2001;17(3):153–7. doi: 10.1155/2001/571254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClain SL, Clippinger AJ, Lizzano R, Bouchard MJ. Hepatitis B virus replication is associated with an HBx-dependent mitochondrion-regulated increase in cytosolic calcium levels. J Virol. 2007;81(21):12061–5. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00740-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherji A, Janbandhu VC, Kumar V. HBx-dependent cell cycle deregulation involves interaction with cyclin E/A-cdk2 complex and destabilization of p27Kip1. Biochem J. 2007;401(1):247–56. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SG, Chung C, Kang H, Kim JY, Jung G. Up-regulation of cyclin D1 by HBx is mediated by NF-kappaB2/BCL3 complex through kappaB site of cyclin D1 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(42):31770–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park US, Park SK, Lee YI, Park JG. Hepatitis B virus-X protein upregulates the expression of p21waf1/cip1 and prolongs G1-->S transition via a p53-independent pathway in human hepatoma cells. Oncogene. 2000;19(30):3384–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao L, Leach K, McKinstry R, Gilfor D, Yacoub A, Park JS, Grant S, Hylemon P, Fisher P, Dent P. Hepatitis B virus X protein increases expression of p21Cip-1/WAF1/MDA6 and p27Kip-1 in primary mouse hepatocytes, leading to a reduced cell cycle progression. Hepatology. 2001;34:906–917. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.28886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger C, Zoulim F, Mason W. Hepadnaviruses. In: Knipe D, Howley P, editors. Fields Virology. Vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2007. pp. 2977–3029. [Google Scholar]

- Slagle BL, Lee TH, Medina D, Finegold MJ, Butel JS. Increased sensitivity to the hepatocarcinogen diethylnitrosamine in transgenic mice carrying the hepatitis B virus X gene. Mol Carcinog. 1996;15(4):261–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2744(199604)15:4<261::AID-MC3>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terradillos O, Billet O, Renard CA, RL, Molina T, Briand P, Buendia MA. The hepatitis B virus X gene potentiates c-myc-induced liver oncogenesis in transgenic mice. Oncogene. 1997;14:395–404. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Hepatitis B: fact sheet. Vol. 2010 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yu DY, Moon HB, Son JK, Jeong S, Yu SL, Yoon H, Han YM, Lee CS, Park JS, Lee CH, Hyun BH, Murakami S, Lee KK. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in transgenic mice expressing the hepatitis B virus X-protein. J Hepatol. 1999;31(1):123–32. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80172-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Thorgeirsson SS. Modulation of connexins during differentiation of oval cells into hepatocytes. Exp Cell Res. 1994;213(1):37–42. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Wang Y, Chen JS, Cheng G, Xue J. Transgenic mice expressing hepatitis B virus X protein are more susceptible to carcinogen induced hepatocarcinogenesis. Exp Mol Path. 2004;76:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]