Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) is a member of the family Flaviviridae and JEV infection is a major cause of acute encephalopathy in children, which destroys cells in the CNS, including astrocytes and neurons. However, the detailed mechanisms underlying the inflammatory action of JEV are largely unclear.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

The effect of JEV on the expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 was determined by gelatin zymography, Western blot analysis, real-time PCR and promoter assay. The involvement of the NADPH oxidase and reactive oxygen species (ROS), MAPKs, and the transcription factor NF-κB in these responses was investigated by using selective pharmacological inhibitors and transfection with appropriate siRNAs.

KEY RESULTS

JEV induced the expression of the pro-form of MMP-9 in rat brain astrocytes (RBA-1 cells). In RBA-1 cells, JEV induced MMP-9 expression and promoter activity, which was inhibited by pretreatment with inhibitors of NADPH oxidase (diphenylene iodonium chloride or apocynin), MAPKs (U0126, SB203580 or SP600125) and a ROS scavenger (N-acetylcysteine), or transfection with siRNAs of p47phox, ERK1, JNK2 and p38. In addition, JEV-induced MMP-9 expression was reduced by pretreatment with an inhibitor of NF-κB (helenalin) or transfection with p65 siRNA. Moreover, JEV-stimulated NF-κB activation was inhibited by pretreatment with the inhibitors of NADPH oxidase and MAPKs.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

MMP-9 expression induced by JEV infection of RBA-1 cells was mediated through the generation of ROS and activation of p42/p44 MAPK, p38 MAPK and JNK1/2, leading to NF-κB activation.

Keywords: Japanese encephalitis virus, ROS, matrix metalloproteinase-9, MAPKs, NF-κB

Introduction

Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) is predominantly an arthropod-borne virus composed of a single-stranded positive-strand RNA genome approximately 11 kb in length (Raung et al., 2007). Several lines of evidence suggest that JEV frequently causes severe encephalitic conditions in humans. Clinical symptoms include fever, headache, vomiting, signs of meningeal irritation, and altered consciousness leading to high mortality and neurological sequelae in some of the survivors. The principal target cells for JEV are in the CNS and include neurons and astrocytes (Raung et al., 2005). Astrocytes are neuroectodermally derived cells which are critical for normal function of the CNS, including maintenance of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), support of axons, and ion and neurotransmitter buffering. Moreover, astrocytes may be critical for early recruitment of inflammatory cells in the initiation of virus-induced inflammation (Carpentier et al., 2008). Clinically, an infection with JEV results in increased levels of inflammatory factors such as macrophage-derived chemotactic factor, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-8 (IL-8) in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid (Khanna et al., 1991; Ravi et al., 1997; Singh et al., 2000). The increased levels of inflammatory mediators appear to play a protective role or to initiate an irreversible immune response leading to cell death. However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying JEV-infection-induced inflammation in astrocytes are largely unknown.

In the context of neuro-inflammatory disease, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) have been implicated in several processes, including BBB and blood-nerve barrier opening, invasion of neural tissue by blood-derived immune cells, and direct cellular damage (Leppert et al., 2001; Sellner and Leib, 2006). MMPs are a group of zinc-dependent endopeptidases which degrade extracellular matrix and cell surface proteins. They are essential for embryogenesis, cell migration, tissue remodelling and modulation of inflammation (Martinez-Torres et al., 2004). One class of MMPs that has been shown to function as mediators of lesion development in response to brain injury are the gelatinases, MMP-2 and MMP-9. However, there are differences in the regulation of their expression. MMP-2 is constitutively expressed by several cell types, including brain cells (Galis et al., 1994; Fabunmi et al., 1996; Vecil et al., 2000). In contrast, basal levels of MMP-9 are usually low and its expression can be induced by treatment with TNF-α and IL-1β (Sato and Seiki, 1993; Galis et al., 1994; Ries and Petrides, 1995; Fabunmi et al., 1996; Gottschall and Deb, 1996; Vecil et al., 2000). Previous studies have reported that MMP-9 is up-regulated by viral infection in the nervous system and viruses such as HIV increase MMP-9 expression (Misse et al., 2001; Ju et al., 2009). These studies suggested that the expression of MMP-9 might be similarly up-regulated during JEV infection.

The generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) plays an important role in diverse cellular functions including signal transduction, oxygen sensing and host defence (Geiszt and Leto, 2004; Lambeth, 2004) during infection by viruses such as HCV, EBV, EV71 and JEV (Schwarz, 1996; Peterhans, 1997; Lin et al., 2004; Cerimele et al., 2005; Ho et al., 2008; 2009; Miura et al., 2008; Kang et al., 2009). Among the ROS generating enzymes, NADPH oxidases are the major source of ROS (Takeya and Sumimoto, 2006). NADPH oxidase is a multicomponent protein formed by membrane-bound cytochrome b558 and composed of the catalytic subunits gp91phox and p22phox and cytosolic regulatory subunits comprised of p40phox, p47phox, p67phox and the small GTPase Rac (Sumimoto et al., 1996; Barbieri et al., 2004; Nishikawa et al., 2007). ROS production is linked to MMP-9 expression in monocytes and in keratinocytes (Shin et al., 2008; Wan et al., 2008). However, the mechanism of JEV-induced ROS formation leading to MMP-9 expression in astrocytes is, so far, unknown.

Several studies have shown that virus-infected cells activate signalling cascades to produce mediators that initiate inflammatory responses or stimulate anti-viral activities. Moreover, oxidative stress and MAPKs signalling cascades play important roles in the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokine expression following viral infection (Lin et al., 2000; Casola et al., 2001; Barber et al., 2002; Pazdrak et al., 2002). In addition, the activation of NF-κB by viral infection is a key trigger in inducing the expression of cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, MMPs, COX-2 and iNOS (Caamano and Hunter, 2002; Santoro et al., 2003). Previous studies indicated that mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) signalling cascades are involved in virus-induced MMP-9 expression in infected cells. For instance, HIV-1 glycoprotein 120 induces the expression of MMP-9 via p38 MAPK signalling pathway (Misse et al., 2001) and HIV-1 Tat up-regulates expression of MMP-9 via an MAPK-NF-κB dependent pathway in human astrocytes (Ju et al., 2009). Hepatitis B viral HBx protein induces MMP-9 gene expression through the activation of p42/p44 MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways (Chung et al., 2004). However, whether JEV-induced MMP-9 expression is mediated via these signalling pathways in astrocytes is unknown.

In the present study, we investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying JEV-induced MMP-9 expression in cultured rat brain astrocytes (RBA-1 cells). Here, we show that the JEV-induced expression of MMP-9 in RBA-1 cells was mediated through the activation of the NF-κB signalling pathway, following generation of ROS and activation of MAPKs.

Methods

Preparation of viruses

The T1P1 strain of JEV was propagated in C6/36 cells, as previously described (Chiou et al., 2007). The C6/36 cells were transferred to 15 mL tubes, centrifuged at 900×g for 10 min, and the supernatant discarded. JEV (moi = 0.1) was added to the cells for adsorption at 28°C for 1 h. After adsorption, culture medium was added to the tube and the contents were transferred to a T75 flask, followed by incubation at 37°C in an incubator in room air and 5% CO2. After 3 days, the viral supernatants were collected and centrifuged at 900×g for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to Eppendorf tubes and stored at −80°C.

The titer of JEV was determined by a plaque assay. BHK-21 cells (4 × 105 cells per well) were seeded into a six-well culture plate overnight and then infected with a 10-fold serially diluted virus suspension. After 1 h adsorption, the cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and overlaid with 4 mL methylcellulose (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA; 11 g in 500 mL sterile water), 5% PBS and 50% MEM). After 5 days, the cells were fixed with 10% formaldehyde and then stained with 1% crystal violet solution. The virus titer was quantified as PFU (mL cell lysate)−1.

Rat brain astrocyte-1 culture

RBA-1 cells were used throughout this study. This cell line originated from a primary astrocyte culture of neonatal rat cerebrum and was naturally developed through successive cell passages (Jou et al., 1985). RBA-1 cells were stained with glial fibrillary acid protein as an astrocyte-specific marker and used within 40 passages. These cells show normal cellular morphological characteristics and have steady growth and proliferation in the monolayer system (Hsieh et al., 2004).

MMP gelatin zymography

After JEV treatment, the culture medium was collected and mixed with equal amounts of non-reduced sample buffer and separated by electrophoresis on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels containing 1 mg mL−1 gelatin as a protease substrate. Following electrophoresis, gels were placed in 2.7% Triton X-100 for 30 min to remove SDS, and then incubated for 24 h at 37°C in developing buffer (50 mM Tris base, 40 mM HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, and 0.2% Briji 35 Novex, Carlsbad, CA, USA) on a rotary shaker. After incubation, gels were stained in 30% methanol, 10% acetic acid and 0.5% w/v Coomassie Brilliant Blue for 10 min followed by destaining. Mixed human MMP-2 and MMP-9 standards (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA) are used as positive controls. Gelatinolytic activity was evident as horizontal white bands on a blue background. Because cleaved MMPs were not reliably detectable, only pro-form zymogens were quantified.

Total RNA extraction and real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from RBA-1 cells treated with JEV for the indicated times in 10 cm culture dishes with TRIzol according to the protocol of the manufacturer. RNA concentration was spectrophotometrically determined at 260 nm. First strand cDNA synthesis was performed with 2 µg of total RNA using random hexamers as primers in a final volume of 20 µL (5 µg µL−1 random hexamers, 1 mM dNTPs, 2 units µL−1 RNasin and 10 units µL−1 Moloney murine leukaemia virus reverse transcriptase). The reaction was carried out at 37°C for 60 min.

One µL of a 1:10 dilution of the cDNA reaction was amplified using forward and reverse primers for the MMP-9 or GAPDH as a control, using a Taqman PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The primer and probe sequences for MMP-9 or GAPDH gene amplification were custom-designed by GeneDirex (Taipei, Taiwan). The amplification profile includes 1 cycle of initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, 28 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, primer annealing at 62°C for 1 min, extension at 72°C for 1 min and then 1 cycle of final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The expression of GAPDH was used as an internal control for the assay of a constitutively expressed gene. The reactions were performed in a StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) under the following thermal cycling conditions: 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 60 s. The threshold cycle value was normalized to that of GAPDH.

Western blotting analysis of MMP-9

Conditioned media derived from untreated or JEV-treated RBA-1 cells were mixed with equal amounts of reduced sample buffer at 95°C for 5 min before electrophoresis with 10% SDS-PAGE. The resolved band was electrotransferred onto nitrocellulose (NC) membrane, which was incubated overnight at 4°C with a monoclonal antibody against MMP-9 as described by Wu et al. (2004).

Preparation of cell extracts and Western blot analysis

Growth-arrested RBA-1 cells were incubated with JEV at 37°C for various times. The cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, scraped and collected by centrifugation at 45 000×g for 1 h at 4°C to yield the whole cell extract, as described previously (Hsieh et al., 2004). Samples were denatured, subjected to SDS-PAGE using a 10% (w/v) running gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were incubated overnight using anti-phospho-p42/44 MAPK, anti-phospho-p38 MAPK, anti-phospho-JNK1/2, anti-NF-κB (p65) or anti-GAPDH antibody. Membranes were washed with Tris-Tween buffered saline (composition: 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween-20, pH 7.4) four times for 5 min each, incubated with a 1:2000 dilution of anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase antibody for 1 h. The immunoreactive bands detected by ECL reagents were developed by PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA, USA).

Cell fraction isolation

RBA-1 cells were seeded in 10 cm dishes. When they reached 90% confluence, the cells were starved for 24 h in serum-free medium. After incubation, the cells were washed once with ice-cold PBS. Homogenization buffer A (200 µL; 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM EGTA, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 25 µg mL−1 aprotinin, 10 µg mL−1 leupeptin) was added to each dish, and the cells were scraped into a 1.5 mL tube. The cytosolic, membrane and nuclear fractions were prepared by centrifugation as previously described (Hsieh et al., 2007). The protein concentration of each sample was determined by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) reagents. Samples from these supernatant fractions (30 µg protein) were denatured and then subjected to SDS-PAGE using a 10% (w/v) running gel and transferred to NC membranes. The degradation of IκBα and translocation of NF-κB were identified and quantified by Western blot analysis using anti-IκBα and anti-NF-κB (p65) antibodies respectively. The immunoreactive bands detected by ECL reagents were developed by Hyperfilm-ECL.

Rat MMP-9 promoter cloning, transient transfection and promoter activity assays

The upstream region (−1280 to +108) of the rat MMP-9 promoter was cloned to the pGL3-basic vector containing the luciferase reporter system. All plasmids were prepared by using QIAGEN plasmid DNA preparation kits (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The MMP-9 promoter reporter construct was transfected into RBA-1 cells using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. To assess promoter activity, cells were collected and disrupted by sonication in lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-phosphate, pH 7.8, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100 and 10% glycerol). After centrifugation, aliquots of the supernatants were tested for luciferase activity using the luciferase assay system. Firefly luciferase activities were standardized to β-galactosidase activity.

Transient transfection with siRNAs

The RBA-1 cells were cultured on 12-well plates to 70–80% confluence and transiently transfected with siRNAs (p47phox, ERK1, p38, JNK2, p65 or scrambled siRNA) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Briefly, siRNA (100 nM) was formulated with Lipofectamine. The transfection complex was diluted into 400 µL of DMEM/F-12 medium and added directly to the cells for 2 h. The medium was replaced with DMEM/F-12 for 24 h and then infected with JEV. The culture medium was analysed by gelatin zymography. The transfection with siRNAs had no apparent cytotoxic effect (as determined by the conversion of the tetrazolium salt XTT to orange-coloured formazan; Weislow et al., 1989; data not shown).

Measurement of intracellular ROS accumulation

The fluorescent probe DCF-DA was used to monitor net intracellular accumulation of ROS. This method is based on the oxidative conversion of non-fluorescent DCFH-DA to fluorescent DCF by H2O2. RBA-1 cells were washed with warm Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) and incubated in HBSS or cell medium containing 10 µM DCFH-DA at 37°C for 45 min. Subsequently, HBSS or cell medium containing DCFH-DA was removed and replaced with fresh cell medium. RBA-1 cells were then incubated with JEV. The fluorescence intensity (relative fluorescence units) was measured at 485 nm excitation and 530 nm emission using a fluorescence microplate reader (Appliskan™, Thermo, Fremont, CA, USA).

Determination of NADPH oxidase activity by chemiluminescence assay

After incubation, cells were gently scraped and centrifuged at 400×g for 10 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was resuspended with 35 µL per well of ice-cold RPMI-1640 medium, and the cell suspension was kept on ice. To a final 200 µL volume of pre-warmed (37°C) RPMI-1640 medium containing either NADPH (1 µM) or lucigenin (20 µM), 5 µL of cell suspension (0.2 × 105 cells) were added to initiate the reaction followed by immediate measurement of chemiluminescence in an Appliskan luminometer (Thermo) in out-of-coincidence mode. Appropriate blanks and controls were established, and chemiluminescence was recorded. Neither NADPH nor NADH enhanced the background chemiluminescence of lucigenin alone (30–40 counts per min). Chemiluminescence was continuously measured for 12 min, and the activity of NADPH oxidase was expressed as counts per million cells

Inoculation of JE virus in mice and experimental procedures

All animal care and experimental procedures complied with the guidelines of Animal Care Committee of Chang Gung University and NIH Guides for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. ICR mice aged 6–8 weeks were purchased from the National Laboratory Animal Centre (Taipei, Taiwan). A group of five mice were injected i.p. with a dose of 1 × 107 PFU per mouse of JEV suspension diluted with PBS to a final volume of 100 µL. Another five mice were inoculated with a virus-free solution diluted from the cell culture medium; these were used as the control to confirm the infection of mice inoculated with virus suspension. A further group of five mice were given one dose of MMP-2/MMP-9 inhibitor II (1.637 µg kg−1 body weight) for 1 h, prior to JEV infection. The movement and body coordination of inoculated mice were monitored daily for at least 1 week to detect symptoms, such as movement disorders (mostly rigidity of the hind-limbs). In order to examine the cellular expression of the MMP-9 and to confirm JEV infection into the brain, immunohistochemical staining was performed on sections of the brain, which were deparaffinized, rehydrated and washed with PBS. Non-specific binding was blocked by preincubation with PBS containing 5 mg mL−1 of BSA for 1 h at room temperature. The sections were incubated with an anti-MMP-9 or anti-NS1 (glycoprotein of JEV) antibody at 37°C for 1 h and then with an anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase antibody at room temperature for 1 h. Bound antibodies were detected by incubation in 0.5 mg mL−1 of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine/0.01% hydrogen peroxide in 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer, as chromogen (Vector Lab, Burlingame, CA, USA).

Data analysis

Concentration-effect curves were fitted and EC50 values were estimated using the GraphPad Prism program (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Data were expressed as mean ± SEmean. and analysed by one-way ANOVA followed with Tukey's post hoc test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Materials

Anti-phospho-p42/p44 MAPK, anti-phospho-p38 MAPK and anti-phospho-JNK1/2 antibodies were from Cell Signaling (Danver, MA, USA). Anti-MMP-9, anti-IκBα, anti-phospho-IκBα and anti-NF-κB (p65) antibodies were from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Anti-GAPDH antibody was from Biogenesis (Bournemouth, UK). Antibody to NS1 glycoprotein of JEV was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). U0126, SB203580, SP600125 and helenalin (HLN) were from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA). Apocynin (APO) was from ChromaDex (Santa Ana, CA, USA). Diphenylene iodonium chloride (DPI) was from Biomol. MMP-2/MMP-9 inhibitor II was from Calbiochem (Gibbstown, NJ, USA). BCA protein assay reagent was from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA). The p47phox, ERK1, p38, JNK2, p65 and scrambled siRNAs were from Invitrogen. Gelatin, enzymes and other chemicals were from Sigma.

Results

JEV induces MMP-9 expression

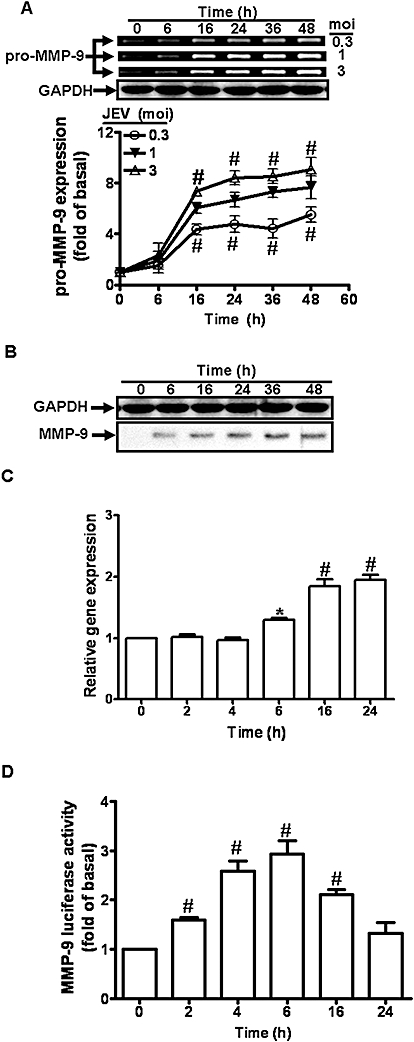

In order to determine the effect of JEV infection on MMP-9 expression, RBA-1 cells were treated with JEV for up to 48 h (Figure 1A). The MMP-9 activity and protein expression in the cell medium were determined by gelatine zymography and Western blot analyses. Exposure to JEV induced MMP-9 protein expression in a time-dependent manner (Figure 1A,B). There was a significant increase in MMP-9 protein by 16 h and a maximal response was achieved after 48 h incubation. The apparent up-regulation occurred in the 92 kDa pro-form zymogen of MMP-9. In contrast, the GAPDH was not changed by incubation with JEV. To examine further whether the increase in MMP-9 activity by JEV resulted from the increase of MMP-9 mRNA expression, the levels of MMP-9 mRNA in RBA-1 cells were determined by real-time PCR and promoter assay. JEV (moi = 1) induced MMP-9 mRNA accumulation in a time-dependent manner in RBA-1 cells (Figure 1C,D). These results suggested that JEV-induced MMP-9 expression occurs at transcriptional and translational levels.

Figure 1.

Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) induces matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 expression in rat brain astrocytes (RBA)-1 cells. (A) RBA-1 cells were infected with JEV for various time intervals. The conditioned media were analysed by gelatin zymography. The whole cell lysates were analysed by Western blot using an anti-GAPDH antibody (as an internal control). (B) Cells were infected with JEV (moi = 1) for various time intervals. The conditioned media were analysed by Western blot using an anti-MMP-9 antibody. (C) RBA-1 cells were infected with JEV for various time intervals. The RNA samples were analysed by real-time PCR for the levels of MMP-9 mRNA. (D) Cells were transiently transfected with an MMP-9-luc reporter gene, and then infected with JEV for various time intervals. The promoter activity of MMP-9 was measured. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; #P < 0.01 as compared with the basal level.

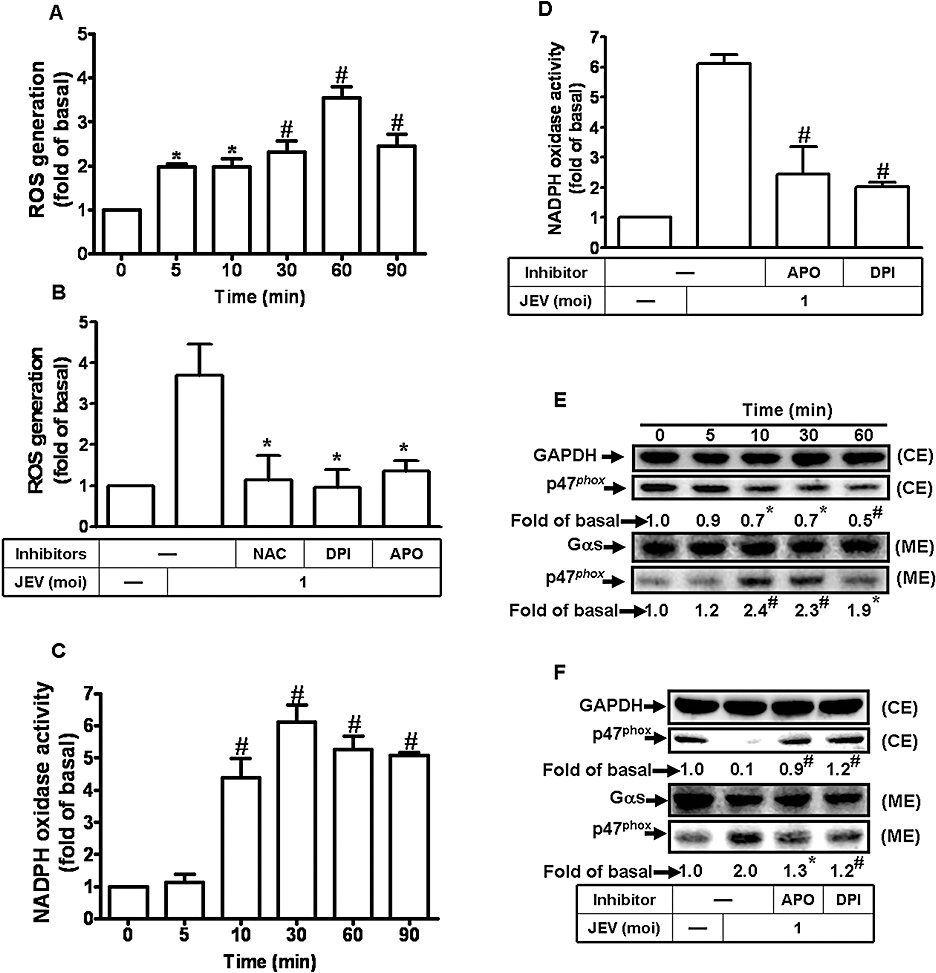

JEV-induced MMP-9 expression is mediated via NADPH oxidase/ROS

JEV has been shown to damage neuronal cells through a ROS-mediated pathway (Lin et al., 2004). Thus, to determine whether JEV could induce ROS production in astrocytes, we used a fluorescent probe DCF-DA to measure the generation of ROS in RBA-1 cells. We found that treatment with JEV induced a significant increase in ROS levels, measurable by 5 min and sustained over 90 min (Figure 2A). NADPH oxidase is an important source for the production of ROS (Takeya and Sumimoto, 2006), and to determine whether ROS was generated by NADPH oxidase in our experimental model, we used two inhibitors of NADPH oxidase (APO and DPI) and a ROS scavenger (NAC) (Lee et al., 2008) were used. Pretreatment with these inhibitors clearly inhibited JEV-induced ROS production in RBA-1 cells (Figure 2B). The activated form of NADPH oxidase is a multimeric protein complex consisting of at least three cytosolic subunits of p47phox, p67phox and p40phox. The phosphorylation of p47phox leads to a conformational change allowing its interaction with p22phox and is indicative of NADPH activation (Sumimoto et al., 1996). Therefore, we determined the effect of JEV on activation of NADPH oxidase and translocation of p47phox in RBA-1 cells. Our results showed that JEV induced a significant increase in NADPH oxidase activity in a time-dependent manner with a maximal response within 30 min (Figure 2C), which was suppressed by pretreatment with APO and DPI (Figure 2D). Moreover, as illustrated in Figure 2E, JEV stimulated a time-dependent increase in translocation of p47phox to the membrane, which was attenuated by pretreatment with DPI and APO (Figure 2F). These results indicated that JEV induces the generation of ROS via increased NADPH oxidase activity.

Figure 2.

Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV)-induced matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 expression was mediated via the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in rat brain astrocytes-1 cells. (A) Cells were labelled with DCF-DA (10 µM), and then infected with JEV (moi = 1) for the indicated time intervals. The fluorescence intensity (relative DCF fluorescence) was measured at 485 nm excitation and 530 nm emission. (B) Cells were labelled with DCF-DA, pretreated with 10 mM NAC, 10 µM diphenylene iodonium chloride (DPI) or 100 µM apocynin (APO) for 1 h, and then infected with JEV (moi = 1) for 1 h. The fluorescence intensity was measured. (C) Cells were infected with JEV (moi = 1) for the indicated time intervals. NADPH oxidase activity was measured. (D) Cells were pretreated with APO or DPI and then infected with JEV for 30 min. The NADPH oxidase activity was measured. (E) Cells were stimulated with JEV (moi = 1) for the indicated time intervals. The membrane and cytosolic fractions were analysed by Western blot using an anti-p47phox antibody. Gαs and GAPDH were used as marker proteins for membrane and cytosolic fractions respectively. (F) Cells were pretreated with DPI (10 µM) or APO (100 µM), and then infected with JEV (moi = 1) for 90 min. The membrane and cytosolic fractions were analysed by Western blot analysis using an anti-p47phox antibody. (G) Cells were pretreated with NAC, DPI or APO for 1 h, and then incubated with JEV (moi = 1) for 16 h. The level of MMP-9 expression was determined by gelatin zymography. (H) Cells were transfected with p47phox siRNA, and then treated with JEV for 16 h. The conditioned media were assessed for MMP-9 expression by gelatin zymography. The whole cell lysates were analysed by Western blot using an anti-p47phox or anti-GAPDH antibody. (I) Cells were pretreated with 10 mM NAC, 10 µM DPI or 100 µM APO for 1 h, and then incubated with JEV (moi = 1) for 6 h. The RNA samples were analysed by real-time PCR for the levels of MMP-9 mRNA. (J) Cells were transiently transfected with an MMP-9-luc reporter gene, pretreated with NAC, DPI or APO for 1 h, and then incubated with JEV for 6 h. The promoter activity of MMP-9 was measured. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; #P < 0.01 as compared with the basal level (A, C and E). *P < 0.05 as compared with the cells exposed to JEV alone (B, D, F, and J). CE, cystolic extract; ME, membranous extract.

The generation of ROS has been shown to induce MMP-9 expression in various cell types (Shin et al., 2008; Wan et al., 2008). In RBA-1 cells, pretreatment with NAC, DPI or APO for 1 h prior to exposure to JEV (moi = 1) significantly attenuated MMP-9 expression, in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 2G). In other experiments, transfection of RBA-1 cells with p47phox siRNA, before treatment with JEV for 16 h, down-regulated the expression of p47phox protein and reduced MMP-9 expression induced by JEV (Figure 2H). These results indicated that JEV-induced expression of MMP-9 protein was mediated via the generation of ROS by NADPH oxidase. We further investigated whether ROS were involved in the expression of mRNA for MMP-9 following JEV infection. Pretreatment with NAC, DPI or APO significantly blocked JEV-induced MMP-9 mRNA accumulation and promoter activity (Figure 2I,J). These results indicated that in RBA-1 cells, JEV-induced de novo MMP-9 mRNA synthesis was mediated through NADPH oxidase and generation of ROS.

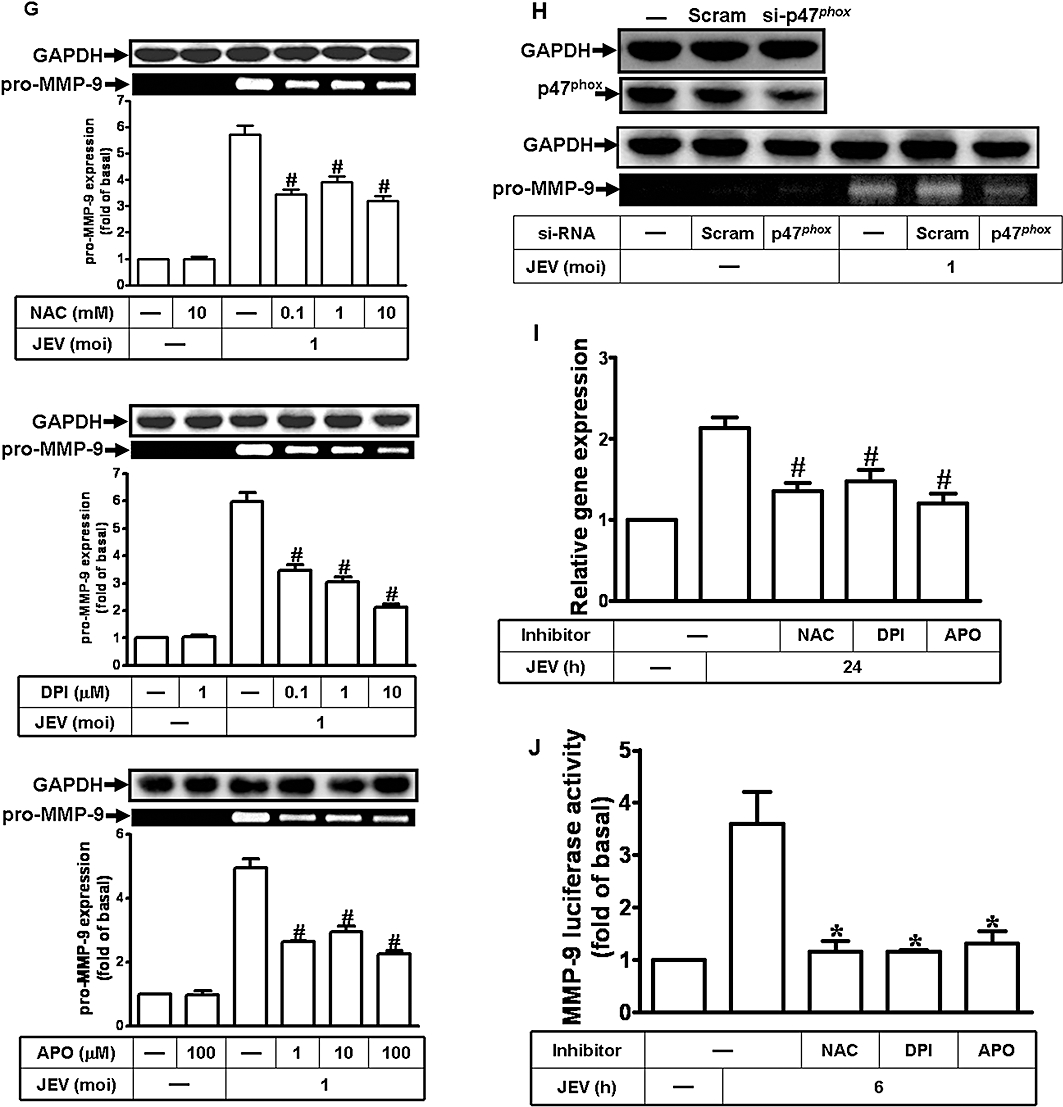

JEV-induced MMP-9 expression is mediated via p42/p44 MAPK

Previous studies have shown that virus-induced MMP-9 expression is mediated through p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation in various cell types (Chung et al., 2004; Behren et al., 2005; Shin et al., 2008). In our model, pretreatment with U0126, an inhibitor of MEK1/2 (an upstream component of p42/p44 MAPK) significantly attenuated, in a concentration-dependent manner, the MMP-9 expression induced by JEV (Figure 3A). In further experiments, transfection of RBA-1 cells with ERK1 siRNA, before incubation with JEV for 16 h, down-regulated the expression of ERK1 protein and reduced MMP-9 expression induced by JEV (Figure 3B). To determine whether the phosphorylation of p42/p44 MAPK was involved in MMP-9 expression, an activation of these kinases was assayed using an antibody specific for the phosphorylated, active forms of p42/p44 MAPK by Western blot. As shown in Figure 3C, JEV stimulated a time-dependent phosphorylation of p42/p44 MAPK in RBA-1 cells. A maximal response was obtained within 3–5 min and slightly declined close to the basal level within 30 min. Pretreatment with U0126 blocked JEV-stimulated p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation during the period of observation. These results suggested a link between activation of p42/p44 MAPK and MMP-9 expression induced by JEV in RBA-1 cells.

Figure 3.

Involvement of p42/p44 MAPK in Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV)-induced matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 expression in rat brain astrocytes-1 cells. (A) Cells were pretreated with U0126 for 1 h and infected with JEV (moi = 1) for 16 h. (B) Cells were transfected with ERK1 siRNA, and then infected with JEV for 16 h. (A, B) The conditioned media were assessed for MMP-9 expression by gelatin zymography. The cell lysates were analysed by Western blot using an anti-ERK1 or anti-GAPDH antibody. (C) Cells were pretreated with 1 µM U0126 for 1 h and then infected with JEV (moi = 1) for the indicated time intervals. (D) Cells were pretreated with 10 mM NAC, 10 µM diphenylene iodonium chloride (DPI), or 100 µM apocynin (APO) for 1 h and then infected with JEV (moi = 1) for 5 min. The cell lysates were analysed by Western blot using an anti-phospho-p42/p44 MAPK or anti-GAPDH antibody. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; #P < 0.01 as compared with the cells exposed to JEV alone.

ROS generation has been shown to stimulate p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation (Komatsu et al., 2008; Sarro et al., 2008) and, in our experimental system, pretreatment of RBA-1 cells with NAC, DPI or APO caused a significant attenuation of JEV-stimulated p42/p44 MAPK phosphorylation (Figure 3D). Taken together, these results suggest that JEV-induced MMP-9 expression was mediated through the ROS-dependent activation of p42/p44 MAPK in RBA-1 cells.

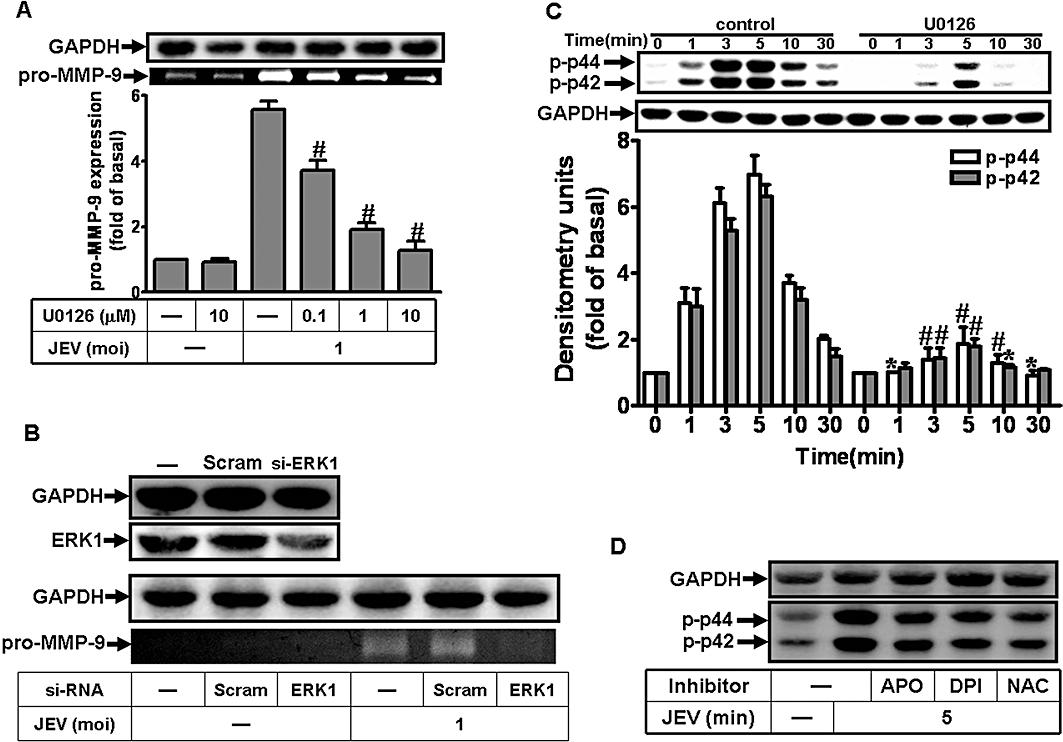

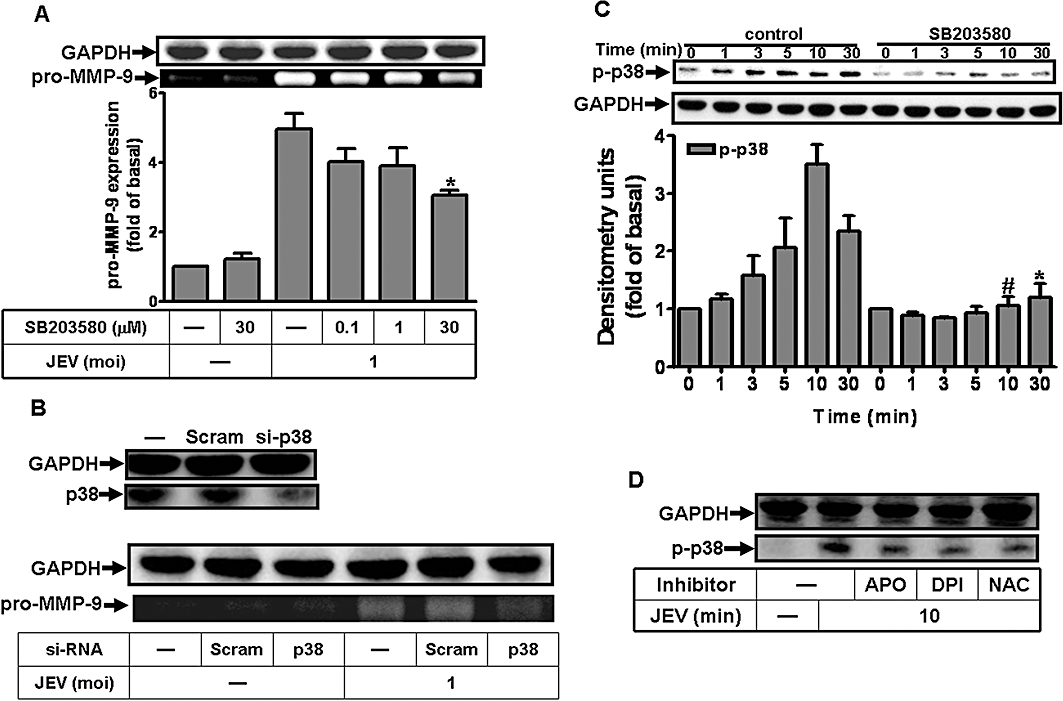

JEV-induced MMP-9 expression is mediated via p38 MAPK

In the rat glioma cell line, HIV-1 gp120 has been shown to activate p38 and this was associated with MMP-9 secretion (Misse et al., 2001). In our RBA-1 cells, pretreatment with the p38 MAPK inhibitor, SB203580, significantly attenuated JEV-induced MMP-9 expression, in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4A). Furthermore, transfection with p38 siRNA down-regulated the expression of p38 protein and reduced MMP-9 expression induced by JEV (Figure 4B). In order to determine whether phosphorylation, that is, activation, of p38 MAPK was involved in MMP-9 expression, we used an antibody specific for the phosphorylated, active form of p38 MAPK in Western blots. As shown in Figure 4C, JEV stimulated a time-dependent phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in RBA-1 cells. A maximal response was obtained within 10 min and slightly declined within 30 min. Pretreatment with SB203580 blocked JEV-stimulated p38 MAPK phosphorylation during the period of observation. Taken together, these results suggested that the activation of p38 MAPK was involved in the expression of MMP-9 induced by JEV in RBA-1 cells.

Figure 4.

Involvement of p38 MAPK in Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV)-induced matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 expression in rat brain astrocytes-1 cells. (A) Cells were pretreated with SB203580 for 1 h and then infected with JEV (moi = 1) for 16 h. (B) Cells were transfected with p38 siRNA, and then infected with JEV for 16 h. (A, B) The conditioned media were assessed for MMP-9 expression by gelatin zymography. The cell lysates were analysed by Western blot using an anti-p38 or anti-GAPDH antibody. (C) Cells were pretreated with 1 µM SB203580 for 1 h and then infected with JEV (moi = 1) for the indicated time intervals. (D) Cells were pretreated with 10 mM NAC, 10 µM diphenylene iodonium chloride (DPI), or 100 µM apocynin (APO) for 1 h and then infected with JEV (moi = 1) for 10 min. The cell lysates were analysed by Western blot using an anti-phospho-p38 MAPK or anti-GAPDH antibody. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; #P < 0.01 as compared with the cells exposed to JEV alone.

The activation of p38 MAPK is stimulated by ROS in cardiomyocytes (Kulisz et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2009). In RBA-1 cells, pretreatment with NAC, DPI or APO caused a significant attenuation of JEV-induced phosphorylation of p38 MAPK (Figure 4D). These results suggested that the activation of p38 MAPK in RBA-1 cells by JEV infection was mediated via ROS generation, leading to MMP-9 expression.

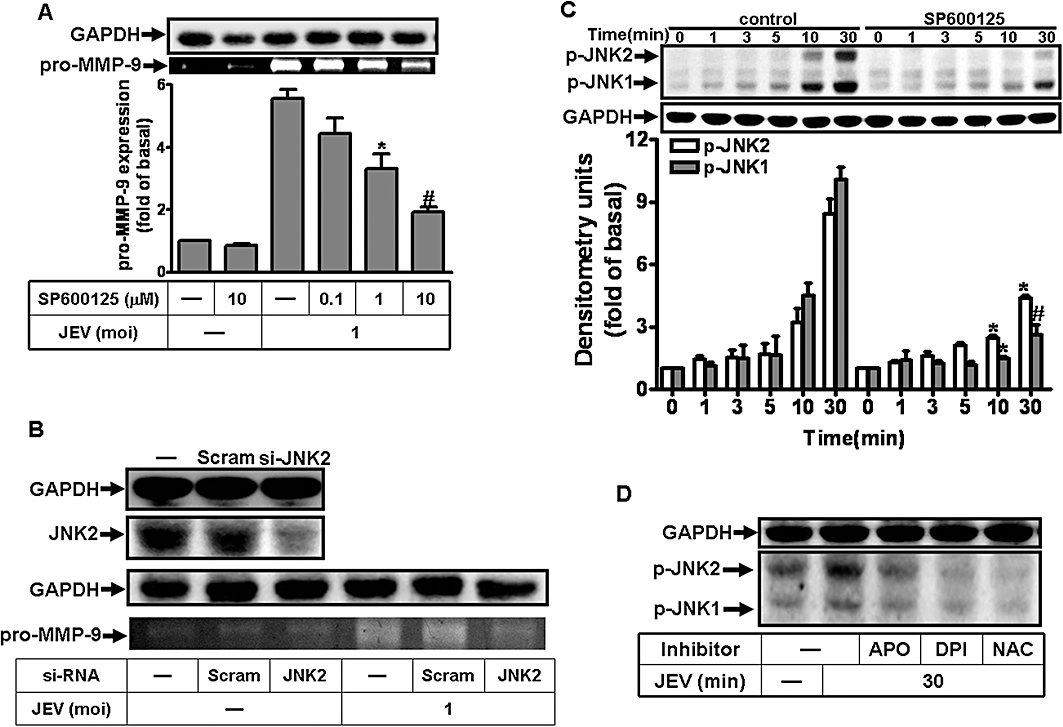

JEV-induced MMP-9 expression is mediated via JNK1/2

The expression of MMP-9 induced by IL-1β-was mediated through JNK1/2 in RBA-1 cells (Wu et al., 2004). As shown in Figure 5A, pretreatment with an inhibitor of JNK1/2, SP600125, significantly attenuated MMP-9 expression induced by JEV, in a concentration-dependent manner. In another set of experiments, transfection with JNK2 siRNA down-regulated the expression of JNK2 protein and reduced MMP-9 expression induced by JEV (Figure 5B). As shown in Figure 5C, JEV also stimulated a time-dependent phosphorylation of JNK1/2 with a maximal response within 30 min in RBA-1 cells. Pretreatment with SP600125 blocked JEV-stimulated JNK1/2 phosphorylation during the period of observation (Figure 5C). Taken together, these results suggested a link between activation of JNK1/2 and expression of MMP-9 induced by JEV in RBA-1 cells.

Figure 5.

Involvement of JNK1/2 in Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV)-induced matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 expression in rat brain astrocytes-1 cells. (A) Cells were pretreated with SP600125 for 1 h and then infected with JEV (moi = 1) for 16 h. (B) Cells were transfected with JNK2 siRNA, and then infected with JEV for 16 h. (A, B) The conditioned media were assessed for MMP-9 expression by gelatin zymography. The cell lysates were analysed by Western blot using an anti-JNK2 or anti-GAPDH antibody. (C) Cells were pretreated with 1 µM SP600125, 10 mM NAC, 10 µM diphenylene iodonium chloride (DPI) or 100 µM apocynin (APO) for 1 h, and then infected with JEV (moi = 1) for the indicated time intervals. (D) Cells were pretreated with 10 mM NAC, 10 µM DPI or 100 µM APO for 1 h, and then infected with JEV (moi = 1) for 30 min. The cell lysates were analysed by Western blot using an anti-phospho-JNK1/2 or anti-GAPDH antibody. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; #P < 0.01 as compared with the cells exposed to JEV alone.

Generation of ROS initiated the activation of JNK1/2 by TNF-α (Schwabe and Brenner, 2006; Shen and Liu, 2006). As shown in Figure 5D, pretreatment with NAC, DPI or APO caused a significant attenuation of JEV-stimulated JNK1/2 phosphorylation. These results suggested that the activation of JNK1/2 was mediated via ROS production, leading to MMP-9 expression in RBA-1 cells by JEV infection.

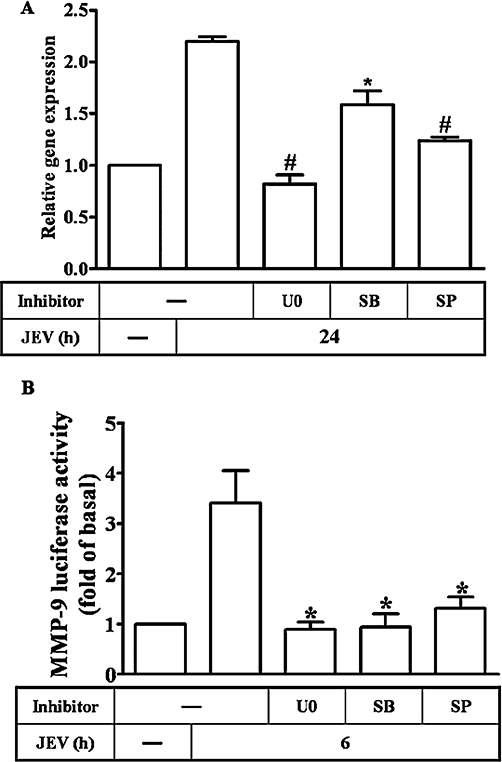

JEV-induced MMP-9 mRNA expression is mediated through MAPKs

The possible regulation of MMP-9 mRNA transcription by MAPKs was investigated using selective pharmacological inhibitors. As shown in Figure 6A and B, the pretreatment of RBA-1 cells with U0126, SB203580 or SP600125 significantly blocked JEV-induced MMP-9 mRNA accumulation and promoter activity. These results further indicated that in RBA-1 cells, regulation of MMP-9 expression through activation of MAPKs occurred mainly at the transcriptional level.

Figure 6.

Involvement of MAPKs in matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 mRNA expression induced by Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) in rat brain astrocytes-1 cells. (A) Cells were pretreated with 1 µM of U0126 (U0), SP600125 (SP) or SB203580 (SB) for 1 h, and then infected with JEV (moi = 1) for 6 h. The RNA samples were analysed by real-time PCR for the levels of MMP-9 mRNA. (B) Cells were transiently transfected with an MMP-9-luc reporter gene, pretreated with 1 µM of U0126, SB203580 or SP600125 for 1 h, and then infected with JEV for 6 h. The promoter activity of MMP-9 was measured. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; #P < 0.01 as compared with the cells exposed to JEV alone.

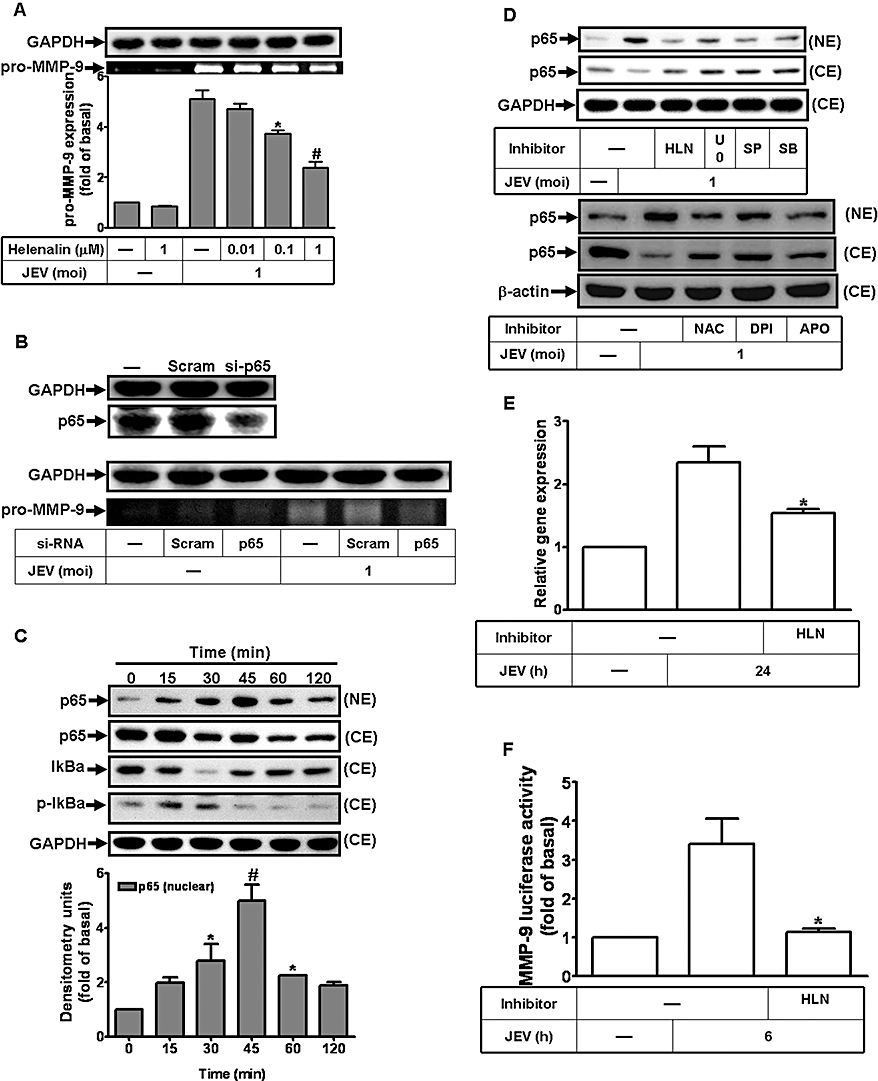

JEV stimulates NF-κB activation mediated through p42/p44 MAPK, p38 MAPK and JNK1/2, and leads to MMP-9 expression

Inflammatory responses to viral infections are highly dependent on the activation of the transcription factor NF-κB (Caamano and Hunter, 2002; Li and Verma, 2002). First, we determined whether the activation of NF-κB was involved in JEV-induced MMP-9 expression in RBA-1 cells. As shown in Figure 7A, pretreatment with an NF-κB inhibitor HLN attenuated MMP-9 expression in a concentration-dependent manner. Further, transfection with p65 siRNA down-regulated the expression of p65 protein and attenuated JEV-induced MMP-9 expression in RBA-1 cells (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

NF-κB translocation is a functional index during Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV)-induced matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 expression in rat brain astrocytes-1 cells. (A) Cells were pretreated with helenalin (HLN) for 1 h and then infected with JEV (moi = 1) for 16 h. (B) Cells were transfected with p65 siRNA, and then infected with JEV for 16 h. (A, B) The conditioned media were assessed for MMP-9 expression by gelatin zymography. The cell lysates were analysed by Western blot using an anti-NF-κB p65 or anti-GAPDH antibody. (C, D) Time dependence of JEV-induced NF-κB translocation and IκB-α degradation. Cells were pretreated with or without 1 µM helenalin, 1 µM U0126, 1 µM SP600125, 1 µM SB203580, 10 mM NAC, 10 µM diphenylene iodonium chloride (DPI) and 100 µM apocynin (APO) for 1 h, and then were stimulated with JEV (moi = 1) for the indicated time intervals. Nuclear and cytosolic fractions were analysed by Western blot using an anti-NF-κB (p65), anti-phospho-IκBα, anti-IκBα antibody or anti-GAPDH antibody. (E) Cells were pretreated with 1 µM helenalin for 1 h, and then infected with JEV (moi = 1) for 6 h. The RNA samples were analysed by real-time PCR for the levels of MMP-9 mRNA. (F) Cells were transiently transfected with an MMP-9-luc reporter gene, pretreated with helenalin for 1 h and then infected with JEV for 6 h. The promoter activity of MMP-9 was measured. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; #P < 0.01 as compared with the cells exposed to JEV alone (A and F) or exposed to vehicle alone (C).

The activation of the NF-κB pathway involves degradation of the inhibitor, IκBα, followed by NF-κB translocation into the nucleus. The cytosolic and nuclear fractions of RBA-1 cells stimulated with JEV for various times were used to determine the degradation of IκBα and NF-κB translocation by Western blot using an anti-IκBα or anti-NF-κB (p65) antibody respectively. As shown in Figure 7C, JEV stimulated the translocation of NF-κB (p65) into nucleus and the degradation of IκBα within 30 to 45 min.

In addition, many of the genes regulated by MAPKs are dependent on NF-κB for transcription. We therefore assessed the activation of NF-κB, following JEV stimulation, in the presence of the inhibitors of ROS generation, MAPKs and NF-κB. JEV-stimulated activation of NF-κB was significantly inhibited by pretreatment with HLN, U0126, SP600125, SB203580, NAC, DPI and APO (Figure 7D), implying that NF-κB translocation was essential for MMP-9 induction mediated through NADPH oxidase, ROS, p42/p44 MAPK, p38 MAPK and JNK1/2 in RBA-1 cells.

This regulation of MMP-9 gene transcription through NF-κB pathways induced by JEV was confirmed by real-time PCR and promoter assay. As shown in Figure 7E and F, JEV-induced MMP-9 mRNA accumulation and promoter activity were inhibited by pretreatment with HLN. These results indicated that JEV induced MMP-9 gene transcription via a NF-κB signalling pathway in RBA-1 cells.

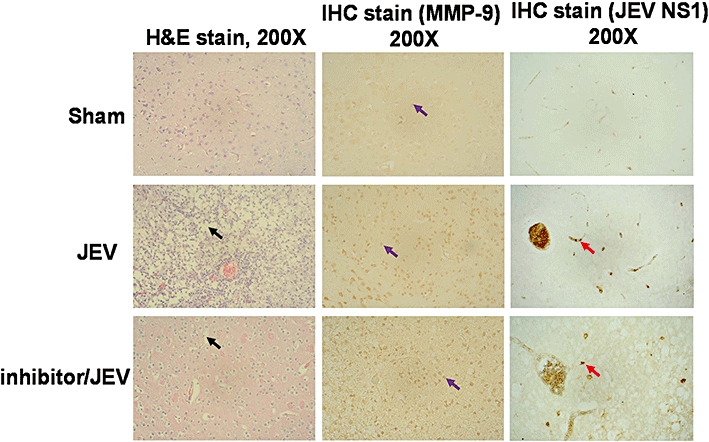

JEV-induced MMP-9 expression in the mouse brain tissue

MMP-9 is over-expressed in brains of animals, affected by neurodegenerative diseases associated with a chronic inflammatory process (Leppert et al., 2001; Mandal et al., 2003; Sellner and Leib, 2006). Therefore, we looked for MMP-9 expression in histological sections of brain from JEV infected mice. Immunohistochemical staining with antibodies against MMP-9 and NS1 showed that, in brains from JEV-infected mice, both NS1 glycoprotein of JEV and MMP-9 were strongly expressed (Figure 8). In addition, JEV infection caused brain damage, as revealed by H&E staining, and which was reduced by pretreatment with MMP-2/MMP-9 inhibitor II. These data demonstrated that JEV infection induced MMP-9 expression in the brain and was associated with brain damage in vivo.

Figure 8.

Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) infection induced matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 expression and brain damage in mice. Immunohistochemical staining (IHC) for MMP-9 and NS1 in sections of the brain and H&E staining for the brain from virus-free culture medium-treated mice (Sham), JEV-injected mice (JEV) and MMP-2/MMP-9 inhibitor II-pretreated mice (Inhibitor/JEV). The black arrow indicates tissue damage. The purple arrow indicates MMP-9 expression. The red arrow indicates NS1 glycoprotein of JEV. Photographs were taken at 200× magnification.

Discussion

Neurological diseases caused by neurotropic viruses are often characterized by a massive neuronal dysfunction and destruction (Raung et al., 2007). Based on neural cell composition and the barrier between the peripheral and CNS, astrocytes could play a role in the transmission of virus from peripheral blood flow into the CNS. In the CNS, MMPs have been shown to degrade components of the basal lamina, leading to disruption of the BBB and to contribute to the neuroinflammatory responses in many neurological diseases (Mandal et al., 2003). In certain in vivo situations, it has been observed that the inflammation-related MMPs, such as MMP-9 and matrilysin, are over-expressed in brains with neurodegenerative diseases, associated with a chronic inflammatory process. Furthermore, some in vitro studies have shown that other neural cells, such as astrocytes, are also infected by JEV (Chen et al., 2000b). However, the mechanisms of MMP-9 expression induced by JEV in astrocytes are largely unknown. In this study, our results have demonstrated that JEV stimulated MMP-9 expression that was mediated through the generation of ROS and activation of NADPH oxidase, p42/p44 MAPK, p38 MAPK, JNK1/2 and NF-κB in RBA-1 cells.

Oxidative stress is a major factor in the development and the progression of many pathological conditions, including JEV-induced damage of neuronal cells (Schwarz, 1996; Peterhans, 1997; Lin et al., 2004; Cerimele et al., 2005; Ho et al., 2008; 2009; Miura et al., 2008; Kang et al., 2009). Our results revealed that JEV infection in RBA-1 cells stimulated the cellular production of ROS mediated through the activation of NADPH oxidase. In addition, the activation of NADPH oxidase was due to the translocation of p47phox from the cytosol to the cell membrane, which was inhibited by pretreatment with APO and DPI. Previous studies have also reported that MMP-9 expression is induced by oxidative stress after metal nanoparticle stimulation (Shin et al., 2008; Wan et al., 2008). In our study, JEV-induced MMP-9 protein and mRNA expression, as well as promoter activity, were attenuated by pretreatment with APO, NAC, and DPI or transfection with p47phox siRNA. These results, taken together, indicated that the expression of MMP-9 in RBA-1 cells, induced by JEV, involved the activation of NADPH oxidase and the generation of ROS.

MMP-9 gene expression has been shown to be regulated by diverse MAPKs in different cell types (Schwingshackl et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2002; Arai et al., 2003). Our results revealed that JEV stimulated rapid phosphorylation of p42/p44 MAPK, which was significantly inhibited by pretreatment with U0126. In addition, the JEV-induced expression of MMP-9 protein was significantly inhibited by pretreatment with U0126 or transfection with ERK1 siRNA, indicating that p42/p44 MAPK cascade participated in MMP-9 induction in RBA-1 cells. These results are consistent with those obtained with hepatitis B viral HBx- and papillomavirus E2 protein-induced MMP-9 expression, via the p42/p44 MAPK pathway (Chung et al., 2004; Behren et al., 2005). Next, we confirmed the involvement of p38 MAPK in JEV-induced MMP-9 expression in RBA-1 cells. Our data showed that JEV stimulated phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and led to MMP-9 expression, which was blocked by pretreatment with SB203580 or transfection with p38 siRNA. These results indicated that JEV-induced MMP-9 expression was partially mediated through the activation of p38 MAPK pathway, consistent with other results showing that the activation of p38 MAPK is necessary for HIV-1 gp120-induced MMP-9 expression in rat glioma cell line (Misse et al., 2001). Apart from p42/p44 MAPK and p38 MAPK, we found that JEV-induced MMP-9 expression was mediated through the activation of JNK1/2, as pretreatment with SP600125 or transfection with JNK2 siRNA attenuated JEV-induced responses. These observations are consistent with reports that the activation of JNK1/2 has been shown to induce MMP-9 expression in several cell types (Woo et al., 2004; 2005;). These results suggest that the JEV-stimulated MMP-9 expression was mediated through MAPKs in RBA-1 cells. Moreover, previous studies have reported that ROS regulate MAPKs activation (Kulisz et al., 2002; Schwabe and Brenner, 2006; Komatsu et al., 2008; Sarro et al., 2008). In this study, we ascertained that MAPKs activated by JEV infection were diminished by pretreatment with the APO, DPI and NAC. These results suggested that JEV-induced MAPKs activation was mediated through NADPH oxidase activation and ROS generation in RBA-1 cells.

It has been well established that certain inflammatory responses following exposure to extracellular stimuli are highly dependent on the activation of NF-κB which plays an important regulatory role in the expression of certain genes (Chen et al., 2000a; Bian et al., 2001). In this study, MMP-9 expression induced by JEV was abolished by pretreatment with HLN or transfection with p65 siRNA, indicating that the activation of NF-κB was involved in the JEV-induced expression of MMP-9. Moreover, a rapid activation of NF-κB following JEV exposure was observed, which was also inhibited by HLN. However, it remains unclear how the production of ROS and the activation of these MAPKs are associated with NF-κB gene expression. Interestingly, our results demonstrated that JEV-stimulated NF-κB activation was inhibited by pretreatment with NAC, DPI, APO, U0126, SB203580 or SP600125, indicating that the production of ROS and the activation of MAPK pathways may also play a role in NF-κB-dependent gene expression. Moreover, our data confirmed that JEV-induced MMP-9 expression triggered by these signalling components was mediated through regulating MMP-9 promoter transcription activity and mRNA expression.

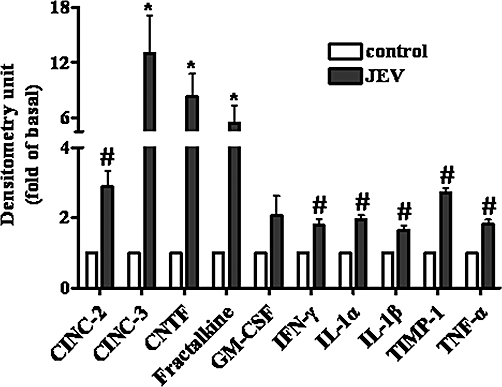

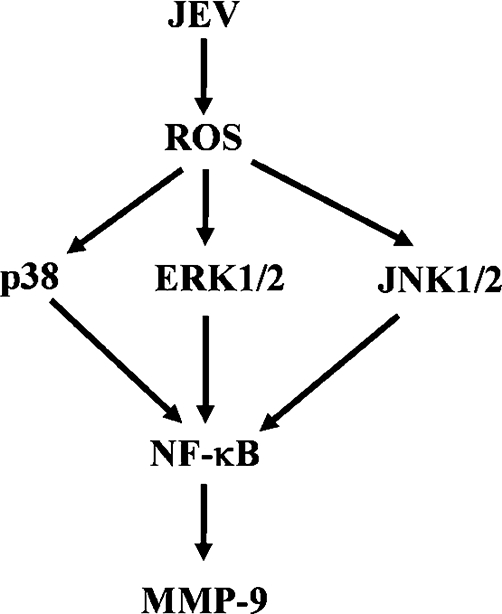

In this study, our results demonstrated that JEV-stimulated NF-κB translocation was essential for MMP-9 induction mediated through NADPH oxidase/ROS and MAPKs in RBA-1 cells. In addition, we also found that JEV infection could induce the expression of cytokines, such as CINC-2, CINC-3, CNTF, fractalkine, IFN-γ, IL-1α, IL-1β, TIMP-1 and TNF-α in RBA cells, which may be involved in the expression of MMP-9 (Figure 9). The roles of these mediators in the expression of MMP-9 will be the subject of a future study. Based on our findings, a schematic pathway depicts a model for the activation of these signalling molecules leading to MMP-9 expression in RBA-1 cells exposed to JEV (Figure 10). These findings concerning JEV-induced MMP-9 expression in RBA-1 cells imply that JEV might play an important role in CNS inflammation and neurological disease. Understanding the underlying mechanisms of MMP-9 expression and its subsequent involvement in inflammatory processes in the CNS may provide useful therapeutic targets that could improve the treatment of brain inflammatory conditions caused by JEV infection.

Figure 9.

Cytokines released from rat brain astrocytes-1 cells induced by Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) infection. After 24 h cultured in serum-free medium, the cells were treated with JEV (moi = 1) for 48 h. The cultured medium was collected and the levels of cytokines were determined using a cytokine array assay kit. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; #P < 0.01 as compared with the control.

Figure 10.

Scheme of the JEV-mediated signalling pathways linked to matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-9) expression in brain astrocytes. Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV)-induced MMP-9 expression is mediated through NADPH oxidase/reactive oxygen species (ROS)/MAPKs leading to NF-κB activation. This signalling pathway might contribute to sustained expression of MMP-9 which is implicated in brain inflammation. Moreover, JEV may induce expression of some cytokines, including IL-1α, IL-β, TNF-α and IFN-γ in rat brain astrocytes-1 cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Council, Taiwan, Grant numbers: NSC97-2321-B-182-007 and NSC98-2321-B-182-004; and Chang Gung Medical Research Foundation, Grant numbers: CMRPD150313, CMRPD140252, CMRPD170491, CMRPD180371 and CMRPD150253. The authors appreciate Mr Li-Der Hsiao for his technical assistance during the preparation of the manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- BCA

Bicinchoninic acid

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acid protein

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IL-8

interleukin-8

- JEV

Japanese encephalitis virus

- MMP-9

matrix metalloproteinase-9

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- Arai K, Lee SR, Lo EH. Essential role for ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase in matrix metalloproteinase-9 regulation in rat cortical astrocytes. Glia. 2003;43:254–264. doi: 10.1002/glia.10255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber SA, Bruett L, Douglass BR, Herbst DS, Zink MC, Clements JE. Visna virus-induced activation of MAPK is required for virus replication and correlates with virus-induced neuropathology. J Virol. 2002;76:817–828. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.2.817-828.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri SS, Cavalca V, Eligini S, Brambilla M, Caiani A, Tremoli E, et al. Apocynin prevents cyclooxygenase 2 expression in human monocytes through NADPH oxidase and glutathione redox-dependent mechanisms. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behren A, Simon C, Schwab RM, Loetzsch E, Brodbeck S, Huber E, et al. Papillomavirus E2 protein induces expression of the matrix metalloproteinase-9 via the extracellular signal-regulated kinase/activator protein-1 signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11613–11621. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian ZM, Elner SG, Yoshida A, Kunkel SL, Su J, Elner VM. Activation of p38, ERK1/2 and NIK pathways is required for IL-1beta and TNF-alpha-induced chemokine expression in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2001;73:111–121. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caamano J, Hunter CA. NF-kappaB family of transcription factors: central regulators of innate and adaptive immune functions. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:414–429. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.3.414-429.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier PA, Getts MT, Miller SD. Pro-inflammatory functions of astrocytes correlate with viral clearance and strain-dependent protection from TMEV-induced demyelinating disease. Virology. 2008;375:24–36. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casola A, Burger N, Liu T, Jamaluddin M, Brasier AR, Garofalo RP. Oxidant tone regulates RANTES gene expression in airway epithelial cells infected with respiratory syncytial virus. Role in viral-induced interferon regulatory factor activation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19715–19722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101526200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerimele F, Battle T, Lynch R, Frank DA, Murad E, Cohen C, et al. Reactive oxygen signalling and MAPK activation distinguish Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)-positive versus EBV-negative Burkitt's lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:175–179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408381102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Chen JJ, Chou CY. Protein kinase calpha but not p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase, p38, or c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase is required for intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression mediated by interleukin-1beta: involvement of sequential activation of tyrosine kinase, nuclear factor-kappaB-inducing kinase, and IkappaB kinase 2. Mol Pharmacol. 2000a;58:1479–1489. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.6.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CJ, Liao SL, Kuo MD, Wang YM. Astrocytic alteration induced by Japanese encephalitis virus infection. Neuroreport. 2000b;11:1933–1937. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200006260-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Ovesen JL, Puga A, Xia Y. Distinct contributions of JNK and p38 to chromium cytotoxicity and inhibition of murine embryonic stem cell differentiation. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:1124–1130. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou SS, Tsai KH, Huang CG, Liao YK, Chen WJ. High antibody prevalence in an unconventional ecosystem is related to circulation of a low-virulent strain of Japanese encephalitis virus. Vaccine. 2007;25:1437–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung TW, Lee YC, Kim CH. Hepatitis B viral HBx induces matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene expression through activation of ERK and PI-3K/AKT pathways: involvement of invasive potential. FASEB J. 2004;18:1123–1125. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1429fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabunmi RP, Baker AH, Murray EJ, Booth RF, Newby AC. Divergent regulation by growth factors and cytokines of 95 kDa and 72 kDa gelatinases and tissue inhibitors or metalloproteinases-1, -2, and -3 in rabbit aortic smooth muscle cells. Biochem J. 1996;315:335–342. doi: 10.1042/bj3150335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galis ZS, Muszynski M, Sukhova GK, Simon-Morrissey E, Unemori EN, Lark MW, et al. Cytokine-stimulated human vascular smooth muscle cells synthesize a complement of enzymes required for extracellular matrix digestion. Circ Res. 1994;75:181–189. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiszt M, Leto TL. The Nox family of NAD(P)H oxidases: host defense and beyond. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51715–51718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400024200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschall PE, Deb S. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase expressions in astrocytes, microglia and neurons. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1996;3:69–75. doi: 10.1159/000097229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho HY, Cheng ML, Weng SF, Chang L, Yeh TT, Shih SR, et al. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency enhances enterovirus 71 infection. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:2080–2089. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/001404-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho HY, Cheng ML, Weng SF, Leu YL, Chiu DT. Antiviral effect of epigallocatechin gallate on enterovirus 71. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:6140–6147. doi: 10.1021/jf901128u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HL, Yen MH, Jou MJ, Yang CM. Intracellular signalings underlying bradykinin-induced matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in rat brain astrocytes-1. Cell Signal. 2004;16:1163–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HL, Wang HH, Wu CY, Jou MJ, Yen MH, Parker P, et al. BK-induced COX-2 expression via PKC-δ-dependent activation of p42/p44 MAPK and NF-κB in astrocytes. Cell Signal. 2007;19:330–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jou TC, Jou MJ, Chen JY, Lee SY. [Properties of rat brain astrocytes in long-term culture] Taiwan Yi Xue Hui Za Zhi. 1985;84:865–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju SM, Song HY, Lee JA, Lee SJ, Choi SY, Park J. Extracellular HIV-1 Tat up-regulates expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 via a MAPK-NF-kappaB dependent pathway in human astrocytes. Exp Mol Med. 2009;41:86–93. doi: 10.3858/emm.2009.41.2.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SM, Kim SJ, Kim JH, Lee W, Kim GW, Lee KH, et al. Interaction of hepatitis C virus core protein with Hsp60 triggers the production of reactive oxygen species and enhances TNF-alpha-mediated apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 2009;279:230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna N, Agnihotri M, Mathur A, Chaturvedi UC. Neutrophil chemotactic factor produced by Japanese encephalitis virus stimulated macrophages. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;86:299–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05813.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu D, Kato M, Nakayama J, Miyagawa S, Kamata T. NADPH oxidase 1 plays a critical mediating role in oncogenic Ras-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression. Oncogene. 2008;27:4724–4732. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulisz A, Chen N, Chandel NS, Shao Z, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial ROS initiate phosphorylation of p38 MAP kinase during hypoxia in cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L1324–L1329. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00326.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambeth JD. NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:181–189. doi: 10.1038/nri1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee IT, Wang SW, Lee CW, Chang CC, Lin CC, Luo SF, et al. Lipoteichoic acid induces HO-1 expression via the TLR-2/MyD88/c-Src/NADPH oxidase pathway and Nrf2 in human tracheal smooth muscle cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:5098–5110. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.5098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppert D, Lindberg RL, Kappos L, Leib SL. Matrix metalloproteinases: multifunctional effectors of inflammation in multiple sclerosis and bacterial meningitis. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;36:249–257. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Verma IM. NF-kappaB regulation in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:725–734. doi: 10.1038/nri910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin RJ, Liao CL, Lin YL. Replication-incompetent virions of Japanese encephalitis virus trigger neuronal cell death by oxidative stress in a culture system. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:521–533. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19496-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YL, Liu CC, Chuang JI, Lei HY, Yeh TM, Lin YS, et al. Involvement of oxidative stress, NF-IL-6, and RANTES expression in dengue-2-virus-infected human liver cells. Virology. 2000;276:114–126. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal M, Mandal A, Das S, Chakraborti T, Sajal C. Clinical implications of matrix metalloproteinases. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;252:305–329. doi: 10.1023/a:1025526424637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Torres FJ, Wagner S, Haas J, Kehm R, Sellner J, Hacke W, et al. Increased presence of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 in short- and long-term experimental herpes simplex virus encephalitis. Neurosci Lett. 2004;368:274–278. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misse D, Esteve PO, Renneboog B, Vidal M, Cerutti M, St Pierre Y, et al. HIV-1 glycoprotein 120 induces the MMP-9 cytopathogenic factor production that is abolished by inhibition of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling pathway. Blood. 2001;98:541–547. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K, Taura K, Kodama Y, Schnabl B, Brenner DA. Hepatitis C virus-induced oxidative stress suppresses hepcidin expression through increased histone deacetylase activity. Hepatology. 2008;48:1420–1429. doi: 10.1002/hep.22486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa H, Wakano K, Kitani S. Inhibition of NADPH oxidase subunits translocation by tea catechin EGCG in mast cell. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;362:504–509. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazdrak K, Olszewska-Pazdrak B, Liu T, Takizawa R, Brasier AR, Garofalo RP, et al. MAPK activation is involved in posttranscriptional regulation of RSV-induced RANTES gene expression. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L364–L372. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00331.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterhans E. Oxidants and antioxidants in viral diseases: disease mechanisms and metabolic regulation. J Nutr. 1997;127:962S–965S. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.5.962S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raung SL, Chen SY, Liao SL, Chen JH, Chen CJ. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors attenuate Japanese encephalitis virus-induced neurotoxicity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;327:399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raung SL, Chen SY, Liao SL, Chen JH, Chen CJ. Japanese encephalitis virus infection stimulates Src tyrosine kinase in neuron/glia. Neurosci Lett. 2007;419:263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi V, Parida S, Desai A, Chandramuki A, Gourie-Devi M, Grau GE. Correlation of tumor necrosis factor levels in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid with clinical outcome in Japanese encephalitis patients. J Med Virol. 1997;51:132–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries C, Petrides PE. Cytokine regulation of matrix metalloproteinase activity and its regulatory dysfunction in disease. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1995;376:345–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro MG, Rossi A, Amici C. NF-κB and virus infection: who controls whom. EMBO J. 2003;22:2552–2560. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarro E, Tornavaca O, Plana M, Meseguer A, Itarte E. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitors protect mouse kidney cells from cyclosporine-induced cell death. Kidney Int. 2008;73:77–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Seiki M. Regulatory mechanism of 92 kDa type IV collagenase gene expression which is associated with invasiveness of tumor cells. Oncogene. 1993;8:395–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe RF, Brenner DA. Mechanisms of liver injury. I. TNF-alpha-induced liver injury: role of IKK, JNK, and ROS pathways. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G583–G589. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00422.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz KB. Oxidative stress during viral infection: a review. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;21:641–649. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)00131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwingshackl A, Duszyk M, Brown N, Moqbel R. Human eosinophils release matrix metalloproteinase-9 on stimulation with TNF-alpha. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:983–989. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellner J, Leib SL. In bacterial meningitis cortical brain damage is associated with changes in parenchymal MMP-9/TIMP-1 ratio and increased collagen type IV degradation. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;21:647–656. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HM, Liu ZG. JNK signalling pathway is a key modulator in cell death mediated by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:928–939. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin MH, Moon YJ, Seo JE, Lee Y, Kim KH, Chung JH. Reactive oxygen species produced by NADPH oxidase, xanthine oxidase, and mitochondrial electron transport system mediate heat shock-induced MMP-1 and MMP-9 expression. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:635–645. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Kulshreshtha R, Mathur A. Secretion of the chemokine interleukin-8 during Japanese encephalitis virus infection. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:607–612. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-7-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumimoto H, Hata K, Mizuki K, Ito T, Kage Y, Sakaki Y, et al. Assembly and activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Specific interaction of the N-terminal Src homology 3 domain of p47phox with p22phox is required for activation of the NADPH oxidase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22152–22158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.22152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeya R, Sumimoto H. Regulation of novel superoxide-producing NAD(P)H oxidases. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1523–1532. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecil GG, Larsen PH, Corley SM, Herx LM, Besson A, Goodyer CG, et al. Interleukin-1 is a key regulator of matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in human neurons in culture and following mouse brain trauma in vivo. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:212–224. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000715)61:2<212::AID-JNR12>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan R, Mo Y, Zhang X, Chien S, Tollerud DJ, Zhang Q. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 are induced differently by metal nanoparticles in human monocytes: the role of oxidative stress and protein tyrosine kinase activation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;233:276–285. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Mori T, Jung JC, Fini ME, Lo EH. Secretion of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 after mechanical trauma injury in rat cortical cultures and involvement of MAP kinase. J Neurotrauma. 2002;19:615–625. doi: 10.1089/089771502753754082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weislow OS, Kiser R, Fine DL, Bader J, Shoemaker RH, Boyd MR. New soluble-formazan assay for HIV-1 cytopathic effects: application to high-flux screening of synthetic and natural products for AIDS-antiviral activity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:577–586. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.8.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo JH, Lim JH, Kim YH, Suh SI, Min DS, Chang JS, et al. Resveratrol inhibits phorbol myristate acetate-induced matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression by inhibiting JNK and PKC delta signal transduction. Oncogene. 2004;23:1845–1853. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo MS, Jung SH, Kim SY, Hyun JW, Ko KH, Kim WK, et al. Curcumin suppresses phorbol ester-induced matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression by inhibiting the PKC to MAPK signaling pathways in human astroglioma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;335:1017–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CY, Hsieh HL, Jou MJ, Yang CM. Involvement of p42/p44 MAPK, p38 MAPK, JNK and nuclear factor-kappa B in interleukin-1beta-induced matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression in rat brain astrocytes. J Neurochem. 2004;90:1477–1488. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]