Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

The cannabinoid CB1 receptor is primarily thought to be functionally coupled to the Gi form of G proteins, through which it negatively regulates cAMP accumulation. Here, we investigated the dual coupling properties of CB1 receptors and characterized the structural determinants that mediate selective coupling to Gs and Gi.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

A cAMP-response element reporter gene system was employed to quantitatively analyze cAMP change. CB1/CB2 receptor chimeras and site-directed mutagenesis combined with functional assays and computer modelling were used to determine the structural determinants mediating selective coupling to Gs and Gi.

KEY RESULTS

CB1 receptors could couple to both Gs-mediated cAMP accumulation and Gi-induced activation of ERK1/2 and Ca2+ mobilization, whereas CB2 receptors selectively coupled to Gi and inhibited cAMP production. Using CB1/CB2 chimeric receptors, the second intracellular loop (ICL2) of the CB1 receptor was identified as primarily responsible for mediating Gs and Gi coupling specificity. Furthermore, mutation of Leu-222 in ICL2 to either Ala or Pro switched G protein coupling from Gs to Gi, while to Ile or Val led to balanced coupling of the mutant receptor with Gs and Gi.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

The ICL2 of CB1 receptors and in particular Leu-222, which resides within a highly conserved DRY(X)5PL motif, played a critical role in Gs and Gi protein coupling and specificity. Our studies provide new insight into the mechanisms governing the coupling of CB1 receptors to G proteins and cannabinoid-induced tolerance.

Keywords: cannabinoid, CB1, CB2, Gi family, Gs family, adenylyl cyclases, cAMP, structure determinations, mutagenesis/chimeric approaches, drug tolerance/dependence

Introduction

Cannabis has been described in the traditional Chinese pharmacopoeia since 200 ad and is used in different civilizations for a variety of medical applications such as appetite stimulation and the treatment of pain, nausea, fever and gynaecological disorders (Adams and Martin, 1996; Lambert, 2001). The mechanism of action of cannabinoid drugs was unknown until the discovery of two cannabinoid receptors, termed CB1 and CB2 (Matsuda et al., 1990; Munro et al., 1993; receptor nomenclature follows Alexander et al., 2009). CB1 receptors are among the most abundant G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in the CNS and are expressed at high levels in the cortex, hippocampus, basal ganglia, and cerebellum, where they mediate the majority of the psychotropic and behavioural effects of cannabis (Matsuda et al., 1990; Howlett et al., 2002). In comparison, CB2 receptors are expressed in peripheral tissues such as spleen, tonsils and on immune cells, suggesting a role in immune responses (Demuth and Molleman, 2006).

The CB1 receptor is a member of the rhodopsin subfamily of GPCRs and was first found to inhibit cAMP production in N18TG2 neuroblastoma cells when the cells were treated with Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Howlett and Fleming, 1984). This effect was blocked by Pertussis toxin (PTX) treatment, suggesting the involvement of Gi proteins (Howlett et al., 1986). A rapid, transient and PTX-sensitive release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores was also observed upon agonist binding to CB1 receptors in NG108-15 and NG18TG2 neuroblastoma cells (Sugiura et al., 1996; 1997;). Although the functional inhibition of adenylyl cyclase by CB1 receptors has been identified in several other systems (Bidaut-Russell et al., 1990; Felder et al., 1993; Childers et al., 1994; Hillard et al., 1999; Wade et al., 2004), several lines of evidence suggest that CB1 receptors can also stimulate the formation of cAMP through coupling to Gs. A cannabinoid-mediated increase in cAMP has been demonstrated in cultured rat striatal neurons as well as in CB1-expressing CHO cells in the presence of forskolin (Glass and Felder, 1997; Felder et al., 1998). A stimulation of basal cAMP accumulation was also observed in a slice preparation of rat globus pallidus in response to high concentrations of the non-selective cannabinoid agonist WIN55,212-2 in the absence of forskolin and PTX (Maneuf and Brotchie, 1997). The interaction of the CB1 receptor with Gs also has been confirmed in CHO cells transfected with recombinant human CB1 receptors (Bonhaus et al., 1998; Calandra et al., 1999). In comparison with CB1, the CB2 receptor modulates adenylyl cyclase and MAP kinase signalling through selective coupling to the PTX-sensitive Gi/o proteins (Bayewitch et al., 1995; Bouaboula et al., 1996).

It is generally believed that several receptor regions of GPCRs are responsible for G protein recognition, coupling and activation. Numerous studies using traditional mutagenesis approaches such as chimeric receptors, alanine-scanning or site-directed mutagenesis have suggested that the second intracellular loop (ICL2) and the third intracellular loop (ICL3) are critically important in determining G-protein recognition and coupling as well as G protein activation efficiency (Moro et al., 1993; Itoh et al., 2001; Nanoff et al., 2006; Johnston and Siderovski, 2007). In addition, the proximal C-terminal tail contains a highly conserved domain, referred as Helix 8, and plays an important role in constraining basal activity (Palczewski et al., 2000) and switching multiple active conformations (Prioleau et al., 2002). A recent study demonstrated that a single amino acid in Helix 8 in the CB1 receptor contributes to selective coupling with GαoA, Gαi1, Gαi2 and Gαi3 (Anavi-Goffer et al., 2007). Additional studies using mutant CB1 receptors, synthetic peptides and molecular modelling have suggested that the first, second and third intracellular loops of the CB1 receptor are involved in its interaction with Gs (Abadji et al., 1999; Calandra et al., 1999; Ulfers et al., 2002). In spite of such information, it still remains unknown which domains are critical for the CB1 receptor to selectively couple to Gs and Gi, pathways with opposing effects on the regulation of cAMP formation.

In the current study, we used different cell lines expressing human CB1 or CB2 receptors to demonstrate that the CB1 receptor dually coupled to the Gs-mediated cAMP accumulation pathway and the Gi-induced activation of ERK1/2 and Ca2+ mobilization, whereas the CB2 receptor only coupled to Gi and thus inhibited cAMP production. Using mutagenesis approaches, functional analysis and computer modelling, we further investigated the structural determinants involved in the coupling of the CB1 receptor with Gs and Gi. These experiments identified the ICL2 and, in particular, the residue Leu-222 as a critical determinant of G-protein coupling selectivity.

Methods

Cell manipulation and transfection

The HEK293, COS-7 and 3T3 cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA). The Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell line was cultured in F12/DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. The CB1 receptor plasmid constructs were transfected into cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two days after transfection, selection for stable expression was initiated by the addition of G418 (800 µg·mL−1).

Molecular cloning, plasmid construction, and mutagenesis of human CB1 and CB2 receptors

CB1 (GenBank Accession NM_016083.4) and CB2 (GenBank Accession NM_001841.2) receptors were cloned by PCR using human genomic DNA as a template. The PCR products were inserted into the HindIII and BamHI sites of the pCMV-Flag and pEGFP-N1 vectors. All constructs were sequenced to verify that they had the correct sequences and orientations. CB1/CB2 receptor chimeras were constructed by the exchange of restriction fragments between CB1 and CB2, using overlap extension PCR strategies. Point mutations were introduced into the CB1 receptor in the ICL2 by PCR overlap extension. Sequence analysis was performed to exclude frame shifts or point mutations, and to control deletion of the termination codon. All of the constructs were generated by ligation of the chimeric receptors or mutated receptors into the HindIII/BamHI sites of the pCMV-Flag vector.

Flow cytometry analysis

Approximately 2 × 105 cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 0.5% BSA [fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer] and incubated with 10 µg·mL−1 of fluorescein isothiocyanate-labelled anti-Flag M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma) in a total volume of 100 µL. After incubating for 60 min at 4°C, cells were pelleted and washed three times in FACS buffer. The cells were then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in FACS buffer and subjected to flow cytometry analysis on a FACScan flow cytometer (Coulter EPICS Elite, Coolten Corp., Hialeah, FL, USA).

cAMP measurement

HEK293 cells stably transfected with Flag-CB1 receptors were seeded in 96 well plates, 24 h before drug treatments. Cells were stimulated with 1 µM WIN55,212-2 in the absence or presence of 10 µM forskolin for 30 min. A non-radioactive homogeneous assay using HitHunter DiscoveRx enzyme fragment complementation technology (DiscoveRx, CA, USA) was used for measuring cAMP levels under the appropriate assay conditions and performed according to the manufacturer's instructions for cAMP determination.

Luciferase activity

After seeding cells in a 96-well plate overnight, HEK293 cells, stably or transiently co-transfected with Flag-CB1 receptors and pCRE-Luc, were grown to 90–95% confluence, stimulated with the indicated concentration of drug in DMEM without FBS, and incubated for 4–6 h at 37°C. Luciferase activity was detected by use of a firefly luciferase assay kit (Kenreal, Shanghai, China). When required, cells were treated overnight with PTX (100 ng·mL−1), or 1 h with H89 (10 µM), Go6983 (1 µM), U0126 (10 µM), wortmannin (1 µM), GM6001 (1 µM) and AG1478 (10 µM) in serum-free DMEM before the start of the experiment.

Confocal microscopy

HEK293 cells transiently transfected with CB1-EGFP and CB2-EGFP were seeded in cover glass-bottomed six-well plates. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were washed with PBS and then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Finally, cells were mounted in mounting reagent (dithiothreitol/PBS/glycerol). Images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM510 laser scanning confocal microscope using a Zeiss Plan-Apo 63 × 1.40 NA oil immersion lens (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Image handling was done in Adobe Photoshop.

ELISA analysis of cell-surface expression

The CB1 and CB2 receptors were analyzed for their comparative ability to traffic to the cell surface using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect the surface expression of the engineered Flag-tag epitope. HEK293 cells were seeded in poly-L-lysine treated 48-well plates and transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 as described previously. The cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde/Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 5 min at room temperature. The cells were then washed three times with TBS and non-specific binding blocked with TBS containing 1% BSA for 45 min at room temperature. The first antibody (anti-Flag M2 monoclonal antibody; Sigma) was added at a dilution of 1:5000 in TBS/BSA for 1 h at room temperature. Three washes with TBS followed, and cells were briefly re-blocked for 15 min at room temperature. An incubation with rabbit anti-mouse conjugated alkaline peroxidase (Sigma) diluted 1:5000 in TBS/BSA was carried out for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were washed three times with TBS and a colorimetric peroxidase substrate was added. When the adequate color change was reached, 100 µL samples were taken for colorimetric readings. Cells transfected with pCMV-Flag3 were studied concurrently to determine background.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cell samples as detailed in the manufacturer's protocol (RNAiso, Takara). Reverse transcription was completed using PrimeScript 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara). cDNA from samples was quantified on a 7500 Real-Time PCR Machine (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) instrument using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara). The following CB1 receptor and β-actin primers were used: β-actin-F: 5′-GGAAATCGTGCGTGACATTA A-3′, β-actin-R: 5′-CAGGAAGGAAGGCTGGAAGA-3′; CB1-F: 5′-CGTCGTTCAAGGAGAATGAGG-3′, CB1-R: 5′-TGCCGATGAAGTGGTAGGAAG-3′. The possibility of genomic DNA contamination was excluded by DNAase treatment and by measurement of β-actin levels in RNA samples (which were not reverse transcribed). Differential expression of the cell lines was compared using the ΔΔCT method.

ERK1/2 activation

The HEK293 cells stably expressing Flag-CB1 receptors were seeded in 12-well plates and starved for 4 h in serum-free medium to reduce background ERK1/2 activation. After stimulation with the drug, cells were lysed. Equal amounts of total cell lysate were size-fractionated by SDS-PAGE (10%) and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked in blocking buffer (TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 5% non-fat dry milk) for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with rabbit monoclonal anti-pERK1/2 antibody (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) and anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (CHEMICON, Temecula, CA, USA) according to the manufacturers' protocols. Total ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling) was assessed as a loading control after p-ERK1/2 chemiluminescence detection using HRP substrate purchased from Cell Signaling.

Intracellular calcium measurement

Calcium mobilization was performed as described previously, with slight modifications (Luo et al., 2008). Briefly, HEK293 cells with stable expression of Flag-CB1 receptors were harvested with Cell Stripper (Mediatech, Herndon, VA, USA), washed twice with PBS and resuspended at 5 × 106 cells·mL−1 in Hanks' balanced salt solution containing 0.02% BSA. The cells were then loaded with 3 µM fura-2/AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) for 30 min at 37°C. Calcium flux was measured using excitation wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm in a fluorescence spectrometer (LS55, Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA, USA). Calibration was performed using 0.1% Triton X-100 for total fluorophore release and 10 mM EGTA to chelate free Ca2+. Intracellular Ca2+ concentrations were calculated using a fluorescence spectrometer measurement programme.

Sequence alignment

The sequences of human Gs- and Gi-coupled receptors were retrieved from the gpDB Database, which is a relational database of reports of GPCRs and GPCR interacting proteins (Theodoropoulou et al., 2008). Multiple sequence alignments of human Gs- or Gi-coupled receptors were constructed using CLUSTALW (Thompson et al., 1994). The site-wise residue frequency diagrams [Logo representation (Schneider and Stephens, 1990)] were plotted using the WebLogo online server (Crooks et al., 2004).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the means ± SEM. Results were analyzed with a one-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni post hoc test using the software Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Differences with a probability value of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Materials

Cell culture media and G418 were purchased from Invitrogen. The pCMV-Flag vectors, forskolin (FSK), Pertussis toxin, the PKA inhibitor H89, the PKC inhibitor Go6983, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) inhibitor U0126, the phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor wortmannin, the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitor GM6001 and the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor AG1478 were purchased from Sigma. The pEGFP-N1 vectors were purchased from Clontech Laboratories, Inc. (Palo Alto, CA, USA). WIN55,212-2, CP55,940, AM630, and AM251 were obtained from Tocris (Ellisville, MO, USA) while rimonabant (Rimon) was obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Supply Program (Bethesda, MD, USA).

Results

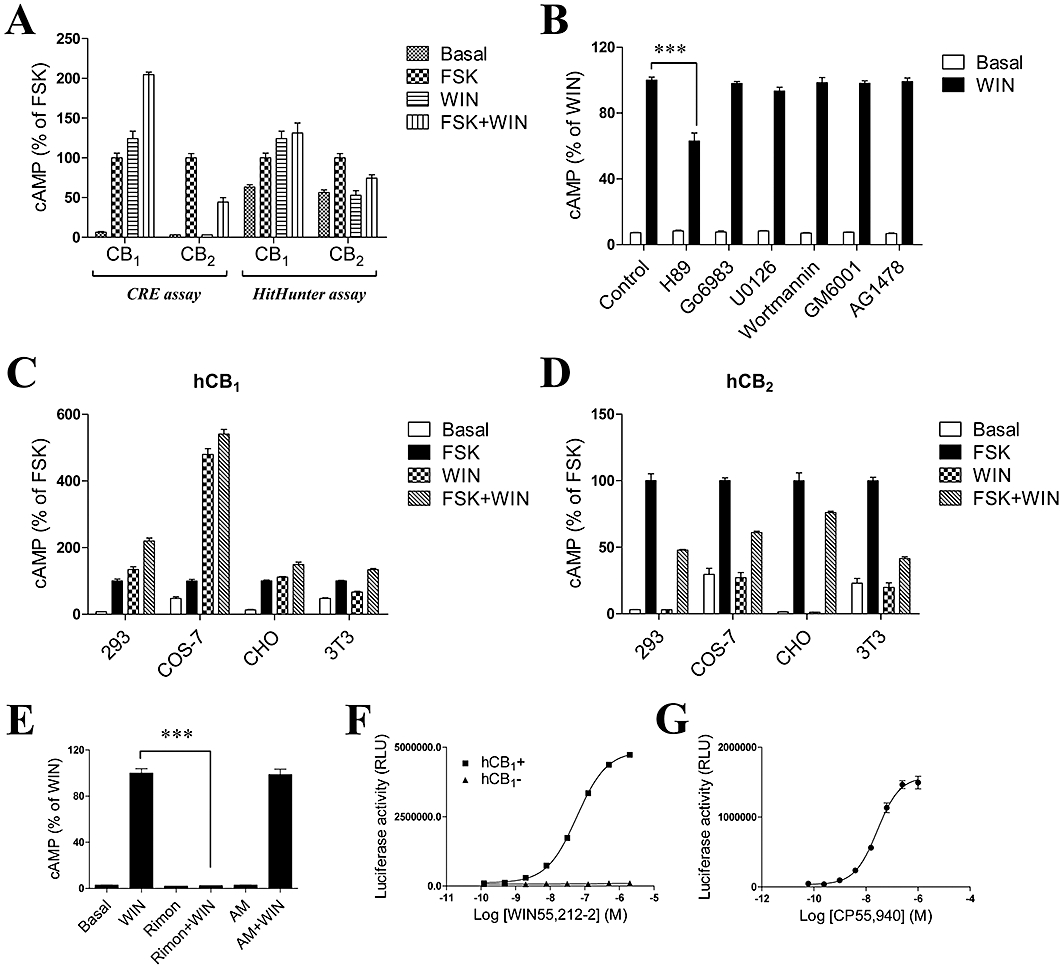

Agonist-induced activation of adenylyl cyclase in cells expressing human CB1 receptors

In our initial experiments, we established stable HEK293 cell lines that express the human cannabinoid CB1 or CB2 receptors, and a reporter gene consisting of the firefly luciferase coding region under control of a minimal promoter containing cAMP-response elements (CREs). The cannabinoid agonist-mediated stimulation of luciferase expression was observed in CB1-expressing cells while the agonist inhibited FSK-stimulated luciferase production in CB2-expressing cells (Figure 1A). To assess the validity and reliability of CRE-luciferase assay, we employed the HitHunter cAMP assay, a method for the detection of cAMP in cells using enzyme fragment complementation technology. As expected, we obtained similar results using the HitHunter cAMP assay (Figure 1A), indicating that activated CB1 receptors can induce cAMP accumulation, as shown earlier (Calandra et al., 1999).

Figure 1.

Agonist-induced activation of adenylyl cyclase in cells expressing the human CB1 receptor. (A) Characterization of cAMP signaling using CRE-luciferase assay and HitHunter cAMP assay. HEK293 cells stably transfected with Flag-CB1 or Flag-CB2 receptors were stimulated with 1 µM WIN55,212-2 in the absence or presence of 10 µM forskolin (FSK). cAMP measurements were carried out as described in the Methods section. (B) Effects of protein kinase inhibitors on inhibition of adenylate cyclase activity induced by WIN55,212-2. HEK293 cells stably expressing CB1 receptors were pretreated with inhibitors for 1 h and stimulated with 1 µM WIN55,212-2 for 4 h. (C,D) cAMP assay of CB1 and CB2 receptors in different cell lines. Different cell lines were transiently transfected with CB1 or CB2 receptor expression constructs and functional assays were carried out as described in the Methods section. (E) WIN55,212-2 induced cAMP accumulation was completely blocked by the CB1 receptor-specific inverse agonist rimonabant (Rimon). Cells were treated with either vehicle or 1 µM WIN55,212-2 alone, or pretreated with 1 µM Rimon and AM630 followed by application of 1 µM WIN55,212-2 in the presence of 1 µM Rimon and AM630. (F,G) Dose-dependent curve of WIN55,212-2 or CP55,940-induced cAMP levels. Cells were incubated with various concentrations of WIN55,212-2 or CP55,940 for 4 h. Results (mean ± SEM) are representative of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. ***P < 0.001.

We further examined whether different inhibitors were responsible for WIN55,212-2-induced luciferase expression. HEK293 cells stably expressing CB1 receptors were pretreated with the PKA inhibitor H89 (10 µM), the PKC inhibitor Go6983 (1 µM), the MAPK inhibitor U0126 (10 µM), the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin (1 µM), the MMP inhibitor GM6001 (1 µM) or the EGFR inhibitor AG1478 (10 µM) for 1 h before agonist challenge. The results demonstrated that only the PKA inhibitor H89 significantly reduced the WIN55,212-2-induced luciferase expression (Figure 1B), implying that luciferase expression was via a cAMP-PKA-gene transcription pathway and the CRE-luciferase assay offered an alternative to functional and biochemical assays for GPCRs.

To eliminate the possibility that CB1 receptor-mediated cAMP accumulation was cell type-specific, we transiently expressed the CB1 or CB2 receptors in HEK293, CHO, COS-7 and 3T3 cells, and then analysed cAMP production. As in our initial studies, the agonist WIN55,212-2 stimulated cAMP production in all cell lines expressing the CB1 receptor (Figure 1C). In contrast, WIN55,212-2 did not stimulate cAMP production in any of the lines expressing the CB2 receptor although it was able to effectively inhibit FSK-stimulated cAMP production (Figure 1D). These results demonstrate that WIN55,212-2-induced regulation of cAMP production was not cell type-specific but was mediated by the intrinsic properties of the CB1 and CB2 receptors. WIN55,212-2-induced cAMP production in the CB1-expressing cells was completely blocked by the selective CB1 receptor antagonist Rimon, but not by the CB2-specific antagonist AM630 (Figure 1E), demonstrating that this effect was mediated by the CB1 receptor. Furthermore, we also studied the dose-dependence of WIN55,212-2-induced cAMP production and measured an EC50 of ∼60 nM (Figure 1F), comparable with the reported affinities for this compound which range from 1.89 to 123 nM (Howlett et al., 2002).

There is some evidence that the binding of WIN55,212-2 to the CB1 receptor is different from that of classical or non-classical cannabinoids, albeit in a manner that still permits displacement by other cannabinoids from CB1 receptor binding sites. To determine whether the cAMP stimulatory pathway induced by the CB1 receptor is ligand-specific, another highly potent agonist, CP55,940, was employed. As shown in Figure 1G, the incubation of CB1 receptor-transfected HEK293 cells with increasing concentrations of CP55,940 led to an dose-dependent increase in cAMP production with an EC50 of ∼30 nM.

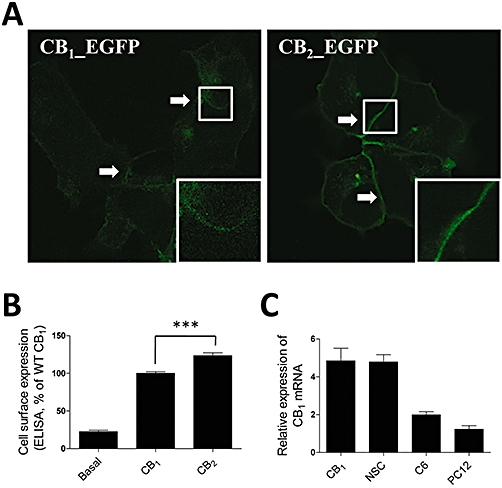

The cell surface expression of CB1 receptor was weaker than CB2 receptor in recombinant cells and was physiologically relevant

The CB1 and CB2 receptors show distinct G protein coupling. We explored the possibility that the distinct coupling properties between CB1 and CB2 receptors might be caused by different expression levels. The green fluorescent protein (GFP) from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria has been developed as a popular reporter molecule for monitoring protein expression and localization. We compared the expression and distribution of CB1 and CB2 receptors, and using these receptors fused to GFP. As shown in Figure 2A, the fluorescence intensity of CB1-EGFP was much weaker than that of CB2-EGFP, although membrane localization of both receptors was observed clearly in HEK293 cells. To demonstrate that the microscopy analysis presents a valid measure of cell surface expression, we further quantitatively detected the surface expression of CB1 and CB2 receptors both fused with the Flag-tag at the C-terminus, using a whole-cell ELISA. The ELISA data presented here show that CB2 receptors were more robustly expressed than the CB1 receptors in recombinant systems (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Expression of CB1 and CB2 receptors. (A) Confocal microscopy analysis of CB1 and CB2 receptor expression. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with EGFP-fused receptors and the cell surface expression was analysed by confocal microscopy. Insets have been sequentially magnified ×2. The cells shown are representative of the cell populations and performed at least three times. (B) ELISA analysis of CB1 and CB2 receptor expression. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with Flag epitope-tagged receptors and the cell surface expression was measured by ELISA analysis. The results represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, each done in triplicate. ***P < 0.01. (C) Expression of CB1 receptor mRNA in cells with endogenous expression and in recombinant cell lines. Quantitative real-time PCR detection of CB1 receptor mRNA was normalized to that of β-actin within each sample, and expressed as a fold difference relative to the PC12 cell line. The error bars displayed are the standard error of duplicate readings from at least three independent experiments. WT, wild type.

To determine whether the expression level of CB1 receptors presented here is physiologically relevant, we examined the expression patterns of CB1 receptor transcripts in stably transfected HEK293 cells and in several cell lines with endogenous expression of these receptors, using a highly sensitive and quantitative PCR-based method. The level of expression in neural stem cells was the highest among the cells with endogenous expression and comparable with the level of CB1 receptors in stably transfected HEK293 cells (Figure 2C). Again, the level of CB1 receptor mRNA expression in the C6 glioma cell line was slightly higher than that in the PC12 cell line (Figure 2C), in agreement with previous observations (Sarker and Maruyama, 2003).

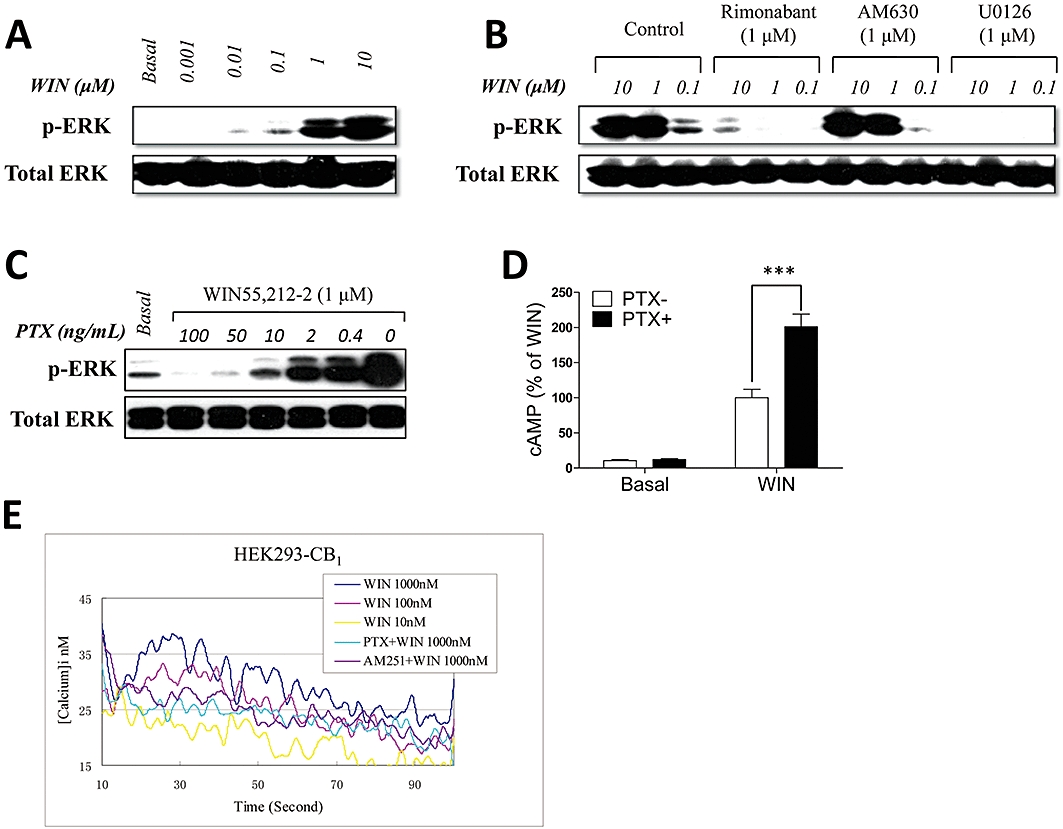

CB1 receptors can dually couple to stimulatory and inhibitory G proteins

As shown in Figure 1, the human CB1 receptor stimulated cAMP production in an agonist-dependent and antagonist-sensitive manner, suggesting a specific interaction of the CB1 receptor with Gs proteins. To investigate whether additional G proteins contribute to CB1 receptor-mediated signalling, intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and ERK1/2 phosphorylation were assessed.

WIN55,212-2 effectively activates ERK1/2 in HEK293 cells stably expressing the CB1 receptor with an EC50 of ∼500 nM (Figure 3A). ERK1/2 activation by WIN55,212-2 was completely inhibited by pre-incubation with the antagonist Rimon, but not by AM630 (Figure 3B). CB1 receptor-mediated ERK1/2 activation was sensitive to the MEK inhibitor U0126 (Figure 3B) and was also effectively blocked by PTX treatment (Figure 3C), suggesting an important role for Gi coupling. Additional evidence that CB1 receptors coupled to Gi was provided by the finding that PTX pretreatment of CB1 receptor-expressing cells resulted in an approximately twofold increase in WIN55,212-2-induced activation of cAMP production (Figure 3D). Taken together, these studies reveal that CB1 receptors can couple to both Gs and Gi and that the Gi pathway primarily contributes to activation of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway.

Figure 3.

The CB1 receptor is dually coupled to Gs and Gi. (A) For dose-response experiments, serum-starved cells were treated with different concentrations of WIN 55,212-2 as indicated and harvested after 5 min. (B) Inhibition of WIN55,212-2-stimulated ERK phosphorylation by rimonabant. Serum-starved cells were incubated for 15 min with 1 µM rimonabant and AM630 and stimulated for 5 min with 1 µM WIN55,212-2 in the presence of rimonabant and AM630. U0126 (1 µM) was used as a negative control. (C) Inhibition of ERK phosphorylation was observed in cells pretreated with increasing concentration of Pertussis toxin (PTX) and stimulated with 1 µM WIN55,212-2. The results shown (A–C) are representative of one of three independent experiments with similar results. (D) PTX unmasked the Gi-coupling of the CB1 receptor in the cAMP assay. Transiently transfected HEK293 cells were pretreated with or without 100 ng·mL−1 PTX for 12 h and stimulated with 1 µM WIN55,212-2. The data (D) are representative of at least three separate experiments performed in triplicate, and mean ± SEM are shown. ***P < 0.001. (E) Specific block of intracellular Ca2+ influx in HEK293 cells by PTX and AM251. Ca2+ influx in cells stably expressing CB1 and pretreated with 100 ng·ml−1 PTX or with 1 µM AM251 was measured in response to 1 µM WIN55,212-2 using the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator fura-2. The data shown in (E) are representative of more than four separate experiments performed in triplicate.

We also examined the effects of cannabinoid agonists on intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in HEK293 cells stably expressing CB1 receptors. WIN55,212-2 induced a transient dose-dependent elevation of intracellular Ca2+ that was effectively attenuated by PTX pretreatment (Figure 3E). This result is consistent with our findings for ERK1/2 activation. Collectively, our studies demonstrate that the CB1 receptor is dually coupled to both stimulatory and inhibitory G-proteins while the CB2 receptor appears to couple selectively to Gi.

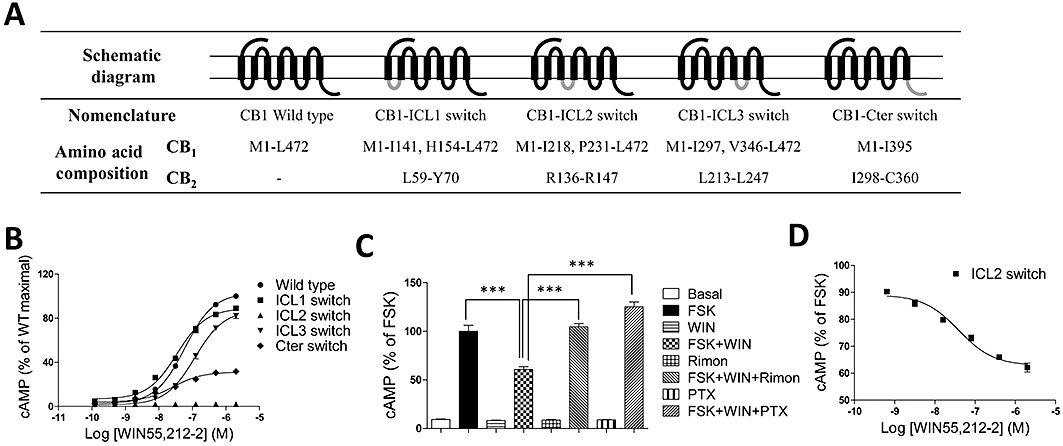

Major role for the ICL2 of the CB1 receptor in the activation of adenylyl cyclase

To identify the intracellular domains responsible for the selective activation of Gs by the CB1 receptor, chimeric cannabinoid receptors were constructed in which intra-cytoplasmic domains of the CB1 receptor were replaced with analogous segments of the CB2 receptor (Figure 4A). These chimeric receptors were then expressed in HEK293 cells and characterized for expression and ability to regulate cAMP production (Table 1 and Figure 4). Replacement of the ICL1 and ICL3 of the CB1 receptor with the corresponding regions of the CB2 receptor had minimal effects on cAMP accumulation while substitution of the C-terminal domain significantly attenuated cAMP production (Figure 4B). Interestingly, while the chimeric CB1 receptor that contains the ICL2 of CB2 receptors was completely defective in stimulating cAMP production (Figure 4B), this chimera effectively coupled to a PTX-sensitive Gi pathway and inhibited FSK-induced cAMP production (Figure 4C,D). These results demonstrate that the ICL2 of the CB1 receptor is responsible for the specificity of receptor-G protein coupling, whereas the C-terminal region of the receptor plays an important role in defining the effectiveness of G protein activation.

Figure 4.

Effects of key domains in the CB1 receptor on Gs- and Gi-dependent signalling. (A) Composition of cannabinoid receptor chimeras. The overall composition of individual cannabinoid receptor chimeras is shown schematically. Numbers indicate the amino acid residues corresponding to the parental cannabinoid receptors. The CB1 receptor sequence is shown in black, and the CB2 receptor sequence is in dark grey. (B) Dose-response curve of cAMP accumulation for the CB1 chimeric receptors upon WIN55,212-2 stimulation. For cAMP measurements, cells were incubated 48 h after transfection with various concentrations of WIN55,212-2. (C) Effects of Pertussis toxin (PTX) and rimonabant (Rimon) on cAMP accumulation in HEK 293 cells expressing CB1-ICL2 receptors. Cells were seeded 24 h prior to the addition of toxins and antagonist. PTX (100 ng·mL−1) and Rimon (1 µM) were added to the cells in FBS-free medium and incubated for 12 h and 15 min respectively. Cells were then incubated with 10 µM forskolin (FSK) or 1 µM WIN55,212-2 plus 10 µM FSK for 4 h. (D) Dose-response curve of inhibition of FSK-induced cAMP elevation, mediated by CB1-ICL2 receptors. Cells were incubated with 10 µM FSK or 10 µM FSK plus WIN55,212-2 (various concentrations) for 4 h. Data shown in (B) and (C, D) are expressed as the percent cAMP activity over the maximal response of wild-type (WT) CB1 receptors and the percent cAMP activity over FSK respectively. Data shown in (B–D) are expressed as the mean ± SEM for triplicate experiments performed in triplicate. ***P < 0.001. ICL, intracellular loop.

Table 1.

Functional characterization of cannabinoid receptor chimeras

| cAMP accumulation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptors | Surface expression FACS; % of WT | Basal % of WT basal | Maximal stimulation % of WT maximal | Fold increase/ (inhibition rate %) | EC50 (nM) |

| CB1WT | 100 | 100 | 100 | 56 ± 2.0 | 59 ± 3.8 |

| CB1-ICL1 | 103 ± 3.1 | 144 ± 8.7 | 90 ± 0.5 | 35 ± 1.9 | 35 ± 1.0 |

| CB1-ICL2 | 61 ± 3.4 | 9.2 ± 1.2 | ND | (40 ± 0.9%)α | 46 ± 4.2α |

| CB1-ICL3 | 110 ± 5.1 | 68 ± 2.9 | 82 ± 1.3 | 69 ± 3.8 | 119 ± 6.4 |

| CB1-Cter | 115 ± 3.5 | 78 ± 3.6 | 32 ± 0.1 | 23 ± 1.1 | 26 ± 1.0 |

The values are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 experiments).

ND, not detected, not compared with wild-type (WT) CB1 receptor.

The values were obtained in the presence of forskolin.

FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; ICL, intracellular loop.

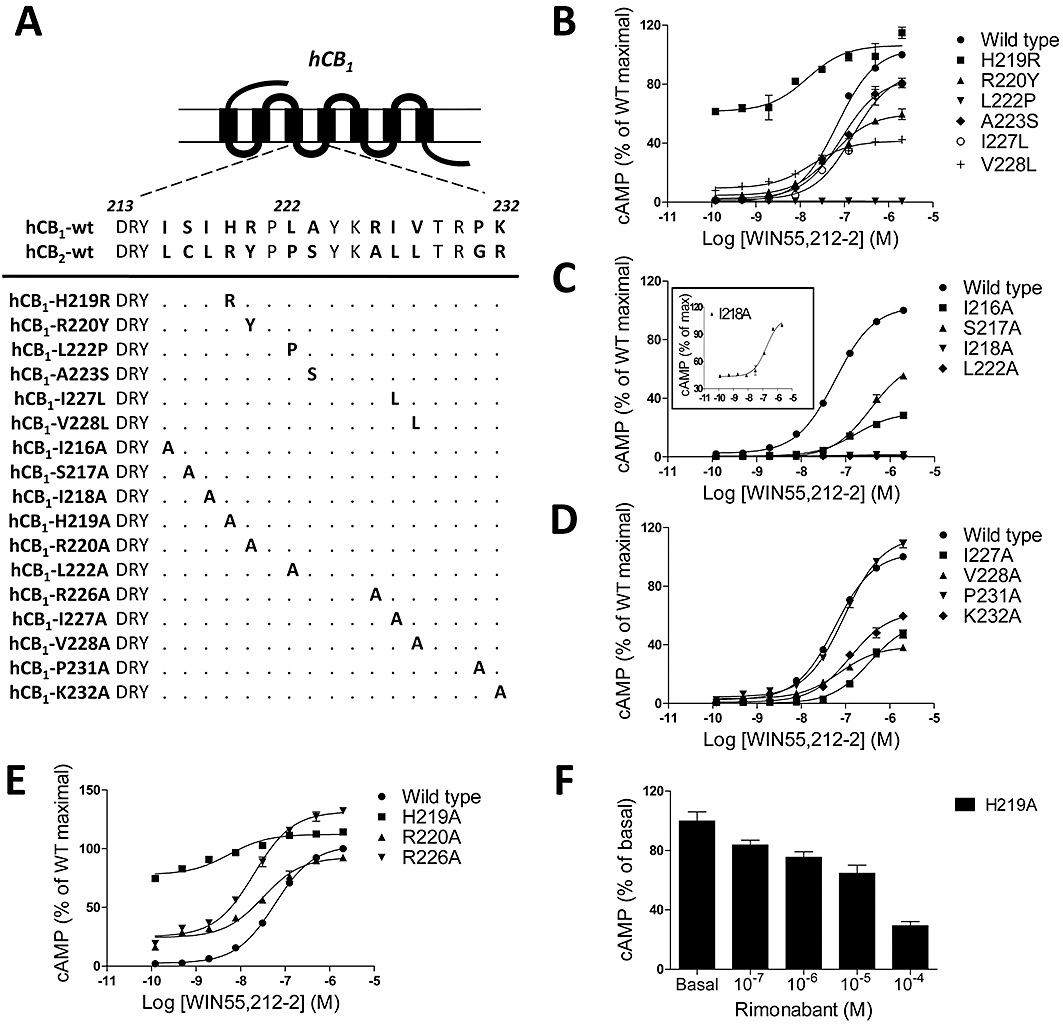

Key residues involved in the interaction of the CB1 receptor with G proteins

Among the 12 amino acids in the ICL2 core region (His-219 to Arg-230), seven amino acids were different between CB1 and CB2 receptors and were candidate residues for selective G-protein coupling (Figure 5A). We therefore initially substituted six of the seven candidate amino acids with corresponding residues in CB2 receptors and constructed the reciprocal series of CB1 mutant receptors (H219R, R220Y, L222P, A223S, I227L and V228L). Among these mutants, A223S and I227L showed cAMP formation in an agonist dose-dependent manner similar to wild-type (WT) CB1 receptors, whereas R220Y and V228L had relative low efficacies compared with WT CB1 receptors (Figure 5B). In contrast, L222P failed to induce cAMP formation and had very low basal cAMP accumulation (Figure 5B). Significant basal cAMP formation was observed in R220Y, V228L and especially H219R, and the last mutant also demonstrated high efficacies of cAMP production compared with WT receptors (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Effects of key residues in the second intracellular loop (ICL2) of the CB1 receptor on Gs-dependent signalling. (A) Single amino acid CB1 mutations within the ICL2. (B–E) Cells were incubated with various concentrations of WIN55,212-2 for 4 h. Values are expressed as a percentage of WIN55,212-2 maximal stimulation in wild-type (WT) CB1 receptors. The results for the mutant I218A is presented in detail in the inset in panel (C), the values of which are expressed as the percent over its maximal. (F) Effect of rimonabant on basal levels of cAMP in H219A mutant transiently transfected cells. Cells were exposed to increasing concentration of rimonabant for 4 h at 37°C. Data points are shown as the mean ± SEM and are representative of at least three independent experiments, each carried out in triplicate.

To further define the functionally critical residues involved in G protein coupling specificity within the ICL2 of the CB1 receptor, alanine scanning mutagenesis was used to mutate each residue between Ile-216 and Lys-232 (Figure 5A). All mutants were transiently expressed in HEK293 cells and analysed for cell surface expression and ability to regulate cAMP production (Figure 5 and Table 2). The mutation of Ile-216, Ser-217, Ile-227, Val-228 and Lys-232 led to a 40–70% loss in WIN 55,212-2-stimulated cAMP production compared with the WT CB1 receptor. In contrast, Ile-218 mutation led to an ∼98% reduction while mutation of Leu-222 again led to a complete loss in cAMP production (Figure 5C,D and Table 2). Interestingly, the mutation of three charged residues (His-219, Arg-220 and Arg-226) led to a significant enhancement in basal cAMP accumulation (∼36, ∼6.6, and ∼7.8-fold, respectively), as well as a modest increase in the ability to stimulate cAMP production (Figure 5E and Table 2), similar to the results in Figure 5B. In view of the observed spontaneous agonist-independent receptor activity, we investigated whether Rimon exhibited negative intrinsic activity by reducing the basal levels of cAMP. The incubation of cells transfected with the H219A mutant, with increasing concentrations of Rimon, resulted in a dose-dependent decrease of basal levels of cAMP (Figure 5F). Taken together, these data suggest an important role for several residues in mediating CB1 receptor coupling to Gs.

Table 2.

Functional characterization of the cannabinoid receptor mutations in the ICL2

| cAMP accumulation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptors | Surface expression FACS; % of WT | Basal % of WT basal | Maximal stimulation % of WT maximal | Fold increase | EC50 (nM) |

| CB1WT | 100 | 100 | 100 | 56 ± 2.0 | 59 ± 3.8 |

| I216A | 78 ± 3.4 | 32 ± 2.0 | 28 ± 0.6 | 51 ± 3.7 | 169 ± 13.3 |

| S217A | 98 ± 9.2 | 32 ± 1.4 | 55 ± 0.7 | 99 ± 3.3 | 372 ± 4.1 |

| I218A | 53 ± 2.1 | 38 ± 1.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 2 ± 0.1 | 163 ± 29.5 |

| H219A | 107 ± 3.7 | 3611 ± 27.1 | 114 ± 0.9 | 2 ± 0.1 | 6 ± 1.0 |

| R220A | 86 ± 4.1 | 656 ± 18.9 | 92 ± 0.8 | 7.9 ± 0.2 | 31 ± 1.7 |

| L222A | 73 ± 5.3 | 16 ± 2.1 | ND | ND | ND |

| R226A | 93 ± 3.2 | 780 ± 20.0 | 133 ± 0.7 | 9.5 ± 0.3 | 19 ± 0.7 |

| I227A | 68 ± 1.5 | 44 ± 0.25 | 48 ± 1.2 | 62 ± 1.9 | 370 ± 23.9 |

| V228A | 73 ± 3.8 | 83 ± 5.5 | 38 ± 0.8 | 26 ± 1.6 | 75 ± 7.6 |

| P231A | 98 ± 4.3 | 129 ± 7.2 | 109 ± 1.2 | 47 ± 2.3 | 95 ± 8.5 |

| K232A | 87 ± 6.7 | 51 ± 1.1 | 60 ± 0.6 | 66 ± 1.7 | 126 ± 2.6 |

The values are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 experiments).

ND, not detected, not compared with wild-type (WT) CB1 receptor.

FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

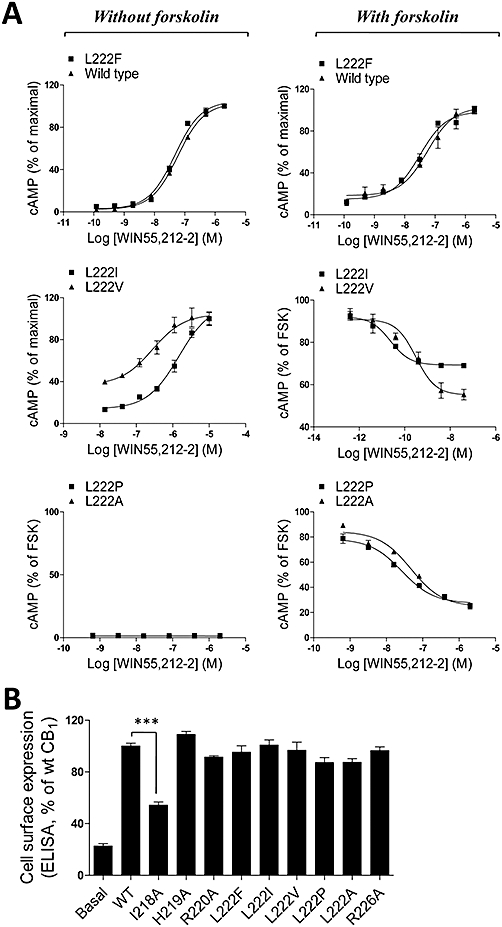

Critical role of a conserved hydrophobic residue in G protein coupling specificity

Because the L222A and L222P mutants were completely defective in promoting cAMP production (Figure 5B,C), the functional role of this residue in regulating G protein coupling was further analysed. Interestingly, initial studies revealed that while these mutants were defective in coupling to Gs, they were able to effectively inhibit FSK-stimulated cAMP production, suggesting that they can couple to Gi (Figure 6A). This suggests a critical role for this residue in determining the specificity of receptor-G protein coupling. The alignment of the ICL2 of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor with those of other members of the GPCR family, including the Gs, Gi and Gs/Gi dual coupling receptors (Supporting Information Table S1), reveals that this hydrophobic residue is highly conserved in the GPCR family (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

(A) Effects of key residues within a highly conserved G protein-coupled receptor motif in selective G protein coupling. Cells were seeded overnight and then incubated with WIN55,212-2 (various concentrations) in the presence or absence of forskolin (FSK; 10 µM) for 4 h. Data (mean ± SEM) are representative of at least three separate experiments performed in triplicate. (B) ELISA analysis of expression of wild-type and mutant receptors. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with Flag epitope-tagged receptors and the cell surface expression was measured by ELISA analysis. The results represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, each carried out in triplicate. ***P < 0.001.

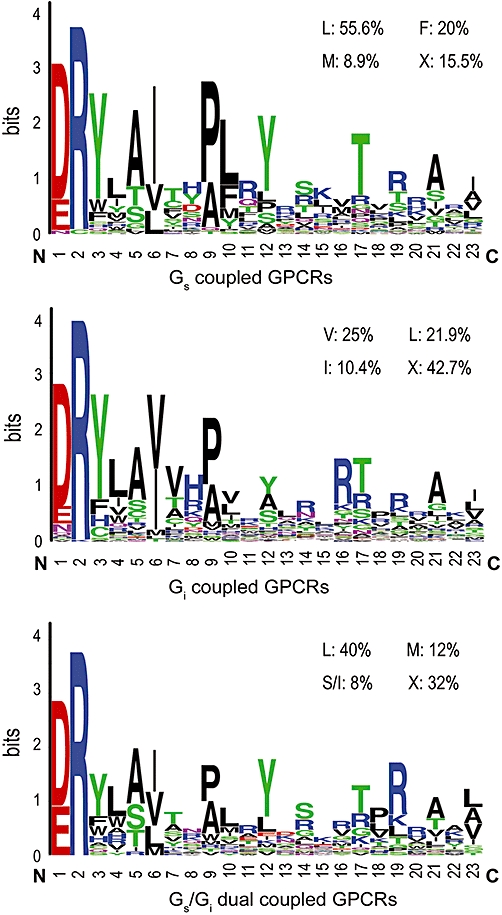

Figure 7.

Amino acid frequency of the second intracellular loop (ICL2) in the CB1 receptor. Amino acid frequency of ICL2 in G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) generated from analysis of the composition of the ICL2 of 96 Gi, 45 Gs and 27 Gi/Gs dual coupled receptors. Frequency of occurrence at position CB1-L222 for Gs, Gi and Gs/Gi dual coupled GPCRs is indicated in the upper right corner in each panel.

To further elucidate the role of this residue in G protein coupling, we next mutated Leu-222 to a number of different residues, including Phe, Ile and Val. The cell surface expression analysis revealed that WT and mutants of CB1 receptors, except the I218A mutant, were expressed at comparable levels on the cell surface (Tables 2 and 3 and Figure 6B). However, mutation to a Phe resulted in a receptor with properties similar to WT CB1, while mutation to Ala or Pro (the residue found in the CB2 receptor), two residues lacking large hydrophobic side chains, led to mutants that were defective in coupling to Gs but effectively coupled to Gi to mediate inhibition of FSK-induced cAMP generation with EC50 values of 30 and 50 nM respectively (Figure 6A and Table 3). These effects were sensitive to PTX and Rimon treatment (Figure S1A). Interestingly, the L222I and L222V mutant receptors exhibited the ability to couple very effectively to Gi, and inhibited FSK-induced cAMP production with EC50 values of ∼0.03 and ∼0.4 nM, respectively, and also coupled to Gs and elevated intracellular cAMP, albeit with EC50s of ∼1600 and ∼370 nM respectively (Figure 6A and Table 3). Pretreatment of cells expressing the L222I (Figure S1B) or L222V (Figure S1C) mutants with PTX attenuated the inhibition of FSK-induced cAMP accumulation seen at low agonist concentrations. Taken together, these results demonstrate that Leu-222, within a highly conserved DRY(X)5PL motif, plays a critical role in mediating G protein coupling specificity of the CB1 receptor and is therefore likely to play an important role in mediating the specificity of many members of the GPCR family.

Table 3.

Functional characterization of leucine-222 mutations of cannabinoid receptor

| cAMP accumulation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptors | Surface expression FACS; % of WT | Basal % of WT basal | Maximal stimulation % of WT maximal | Fold increase/(inhibition rate %) | EC50 (nM) |

| CB1WT | 100 | 100 | 100 | 56 ± 2.0 | 59 ± 3.8 |

| L222F | 95 ± 5.0 | 177 ± 9.1 | 63 ± 1.3 | 20 ± 1.2 | 48 ± 3.2 |

| L222I | 98 ± 6.3 | 19 ± 3.0 | ND | (33 ± 1.6) %α | 0.022 ± 0.009α |

| 6.2 ± 0.4 | 1530 ± 210 | ||||

| L222V | 97 ± 6.3 | 22 ± 3.3 | ND | (45 ± 2.5) %α | 0.34 ± 0.20α |

| 2.2 ± 0.1 | 365 ± 150 | ||||

| L222P | 85 ± 5.3 | 16 ± 1.7 | ND | (75 ± 0.5) %α | 48 ± 3.1α |

| I222A | 73 ± 5.3 | 16 ± 2.1 | ND | (76 ± 0.9) %α | 28 ± 7.9α |

The values are expressed as the mean ± SEM (n = 3 experiments).

ND, not detected, not compared with wild-type (WT) CB1 receptor.

The values were obtained in the presence of forskolin.

FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

Discussion and conclusion

It has long been established that the CB1 receptor primarily induced inhibition of intracellular cAMP production, as the characteristic response to cannabinoid agonists in the brain (Bidaut-Russell et al., 1990; Childers et al., 1994), cultured neurons (Howlett and Fleming, 1984; Howlett et al., 1988; Pinto et al., 1994) and in cells expressing recombinant CB1 receptors (Matsuda et al., 1990; Felder et al., 1993). In addition, this cannabinoid-mediated effect is sensitive to PTX and the CB1 specific antagonist Rimon, demonstrating that the CB1 receptor interacts with Gi/o proteins (Howlett et al., 1986; Pacheco et al., 1993; Vogel et al., 1993; Hillard et al., 1999). However, potentiation of cAMP production was also observed in response to cannabinoid agonists under conditions of PTX pretreatment in cultured neurons and CB1-transfected CHO cells (Glass and Felder, 1997; Bonhaus et al., 1998; Felder et al., 1998), and upon co-expression of CB1 receptors with D2 dopamine receptors in striatal cells and in HEK293 cells (Bonhaus et al., 1998; Felder et al., 1998; Jarrahian et al., 2004). These studies suggest that the CB1 receptor can also interact with Gs proteins. More recently, cellular impedance assays demonstrated that the CB1 receptor can dually couple to Gi and Gs in transfected CHO and HEK293 cells (Peters and Scott, 2009). In the present study, we used several cell lines including HEK293, CHO, COS-7 and NIH3T3 cells, which either transiently or stably expressed the human CB1 receptor, to investigate changes in intracellular cAMP. Our experimental evidence revealed that cAMP accumulation was evoked upon stimulation of cannabinoid agonists in a dose-dependent and PTX-insensitive manner, and this accumulation was blocked by the antagonist Rimon, demonstrating interaction of the CB1 receptor with Gs proteins. Additional functional assays revealed a PTX-sensitive increase in intracellular Ca2+ as well as ERK1/2 phosphorylation in response to CB1 receptor agonists, suggesting that both Gs and Gi proteins are involved in CB1 receptor-mediated signalling.

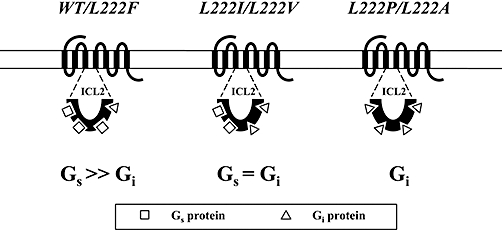

In contrast to the CB1 receptor, the WT CB2 receptor retained the ability to inhibit cAMP accumulation in a PTX-sensitive manner. This led us to further elucidate the structural determinants for the CB1 receptor that are involved in G-protein coupling. We first constructed chimeric CB1/CB2 receptor mutants to investigate the intracellular loops and C-terminal domain of the CB1 receptor implicated in the interaction with G-proteins. As replacement of the ICL2 of the CB1 receptor with the corresponding region of the CB2 receptor resulted in a switch in coupling from Gs to Gi (Figure 4), it seemed that the ICL2 of the CB1 receptor played a major role in the direct interaction of the CB1 receptor with Gs/Gi proteins. Furthermore, as illustrated in Figure 8, a single amino acid, Leu-222, within the highly conserved DRY(X)5PL motif, was identified as a key residue for the specificity of G protein coupling. The L222F mutant receptor retained the ability to couple to Gs proteins to stimulate cAMP production, and substitution of alanine (L222A mutant) or proline (L222P mutant) for Leu-222 switched coupling from the stimulatory pathway to the inhibitory pathway. Replacement of Leu-222 with valine (L222V mutant) or isoleucine (L222I mutant) resulted in balanced coupling of the receptor with Gs and Gi proteins.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of cannabinoid CB1 receptor-G protein coupling. Gs >>Gi represents the receptor predominantly coupling to Gs; Gs= Gi represents the receptor balanced coupling to Gs and Gi; and Gi means the receptor only coupling to Gi.

An alignment of peptide sequences corresponding to the ICL2 region in other G protein-coupled receptors shows that most GPCRs of the rhodopsin family contain a relatively bulky lipophilic amino acid, such as isoleucine, phenylalanine, methionine or valine, at the position corresponding to Leu-222 in the CB1 receptor. Substitutions of alanine or hydrophilic amino acids in this residue in the M1 and M3 muscarinic receptors (Moro et al., 1993), β2-adrenoceptor (Moro et al., 1993), gonadotropic-releasing hormone receptor (Arora et al., 1995), 5-HT2C receptor (Berg et al., 2008), kisspeptin receptor (GPR54) (Wacker et al., 2008), and mouse EP2 and EP3 prostaglandin receptors (Sugimoto et al., 2004) revealed that the resulting mutant receptors were greatly altered in their ability to activate G proteins. Taken together, these results indicate that the targeted ICL2 residue is generally important for receptor-G protein interaction. In the present study, however, the mutant L222F retained preferential Gs coupling, whereas substitution of Leu-222 with either alanine or proline resulted in the switching of G-protein coupling from Gs to Gi. Interestingly, replacement of Leu-222 with either isoleucine or valine led to mutant CB1 receptors (L222V and L222I) with balanced coupling of receptor with Gs and Gi proteins, suggesting that the precise chemical nature of this amino acid residue within the DRY(X)5PL motif plays a critical role in determining the coupling of CB1 receptors to Gs or Gi proteins. In addition, the ICL2 sequence conservation pattern was drawn in the Logo format according to the MSA result of 45 Gs and 96 Gi coupled receptors (Figure 7). Different amino acid preferences in the CB1L222 position had been observed in Gs- and Gi-coupled receptors. At this position, Gs-coupled receptors were relatively well conserved and used a relatively small group of residues including Leu (55.6%), Phe (20%), Met (8.9%) and others (15.5%). In contrast, Gi-coupled receptors were less discriminating and preferentially used Val (25%), Leu (21.9%), Ile (10.4%) and others (42.7%). This alignment result is quite consistent with our site-directed mutagenesis data, suggesting that Leu-222 in the highly conserved motif DRY(X)5PL plays a critical role in regulating the selectivity of the coupling of receptor to Gs and/or Gi, at least in the case of CB1 receptors.

It has been proposed that the density of receptors plays a role in governing the receptor-G protein coupling. Although in recombinant systems promiscuous interaction of receptors with G proteins has been observed when receptor density was increased (Eason et al., 1992), previous studies have demonstrated that Gs-coupling has been observed in cells where CB1 receptors are endogenously expressed ((Glass and Felder, 1997; Bash et al., 2003). In the current study, we demonstrated that the CB1, but not CB2 receptors, could mediate agonist-induced Gs coupling via PTX-insensitive pathways, though CB1 and CB2 receptors are closely related cannabinoid subtypes (Munro et al., 1993), sharing approximately 68% homology in their amino acid sequence, and quantitative analysis confirmed higher cell surface expression of CB2 than that of CB1 receptors in recombinant systems. In addition, our mutagenesis study has provided a molecular and structural explanation for the dual coupling of CB1 receptors to Gi and Gs. Collectively, these results strongly argue against the idea that multiple receptor–G protein coupling reflects an artificial activation of non-preferred G proteins due to receptor over-expression. A recent study presented evidence that cannabinoid tolerance induced by WIN55,212-2 was associated with a molecular switch from Gi/o to Gs coupling in striatum (Paquette et al., 2007). It is likely that the physiological activation of different unrelated G proteins provides a complex mechanism allowing for both the fine-tuning and the adaptation of diverse functional responses elicited by CB1 receptors.

It is seemingly contradictory for one GPCR to dually couple to pathways that are stimulatory and inhibitory for cAMP accumulation, but previous studies showed that several receptors such as the angiotensin II AT1 receptor (Bharatula et al., 1998), the M4 muscarinic cholinoceptor (Dittman et al., 1994), the dog thyrotropin receptor (Allgeier et al., 1997), the prostaglandin EP3D receptor (Negishi et al., 1995) and the human α2-adrenoceptor (Eason et al., 1992) can dually couple to Gs and Gi. Our observation that the mutant CB1 receptors exhibited a switch of G-protein coupling from Gs to Gi (L222A and L222P) or balanced coupling to Gs and Gi (L222V and L222I) strongly suggests that the CB1 receptor has an inherent ability to couple to the stimulatory pathway. It seems unlikely that the CB1 receptor couples to Gs and Gi based on switching, resulting from phosphorylation mediated by PKA as for the β2-adrenoceptor and the mouse prostacyclin receptor (Daaka et al., 1997; Lawler et al., 2001) or by Src for the µ-opioid receptor (Zhang et al., 2009). Furthermore, while the human A1 adenosine receptor differentially activates the Gs and Gi pathways in an agonist-specific manner (Cordeaux et al., 2004), the selectivity of Gs or Gi coupling was found to depend on different concentrations of agonists for the α2A-adrenoceptor (Chabre et al., 1994) and the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor (Krsmanovic et al., 2003). As shown in this study, the WT CB1 receptor expressed in different cell lines was demonstrated not only to preferentially couple to Gs at nanomolar concentrations, resulting in the stimulation of cAMP production, but to also couple to Gi at micromolar concentrations, leading to a PTX-sensitive increase in intracellular Ca2+ as well as ERK1/2 phosphorylation. These results indicate that the dual coupling of WT CB1 receptors with Gs and Gi is likely to be dependent on agonist concentration.

Although the physiological significance of a dual Gs and Gi response to CB1 receptor activation remains to be examined, a recent study demonstrated that rats chronically treated with WIN55,212-2 alone had CB1 receptors predominantly coupled to Gs in the striatum, and the tolerance induced by cannabinoid agonists was associated with an increase in excitatory signalling-mediated pain output triggered by the Gs-coupled CB1 receptors (Paquette et al., 2007). The results obtained in this study clearly illustrate the ability of human CB1 receptors to couple functionally to both Gs and Gi in cell lines expressing recombinant receptors. We have demonstrated for the first time that the ICL2 and particularly the hydrophobic amino acid Leu-222, which resides within the highly conserved DRY(X)5PL motif of the human cannabinoid CB1 receptor, play a critical role in Gs and Gi protein coupling. Our findings will be helpful in understanding the mechanism of cannabinoid agonist-induced antinociceptive tolerance. It will also be interesting to evaluate whether GPCRs generally interact with Gs and Gi proteins through the molecular mechanism discovered in this study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ms Aiping Shao for her technical assistance and equipment usage and Dr Wing-Tai Cheung (School of Biomedical Sciences, the Chinese University of Hong Kong) for his invaluable discussion and careful reading. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China [30871292, 30670425] (to N.M.Z.); the Ministry of Science and Technology [2008AA02Z138] (to N.M.Z.); and the National Institutes of Health [GM44944, GM47417] (to J.L.B.).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- cAMP

cyclic AMP

- CB1

cannabinoid CB1 receptor

- CB2

cannabinoid CB2 receptor

- CRE

cAMP-response element

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinase1/2

- Gi

inhibitory GTP-binding protein of adenylyl cyclase

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- Gs

stimulatory GTP-binding protein of adenylyl cyclise

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- ICL2

the second intracellular loop

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinases

- PI3K

phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase

- PKA, PKC

protein kinase A, C

- PTX

Pertussis toxin

- WT

wild type

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1 (A) Effects of Pertussis toxin (PTX) and rimonabant (Rimon) on cAMP accumulation in HEK 293 cells expressing CB1-L222 mutations. PTX (100 ng·mL−1) and Rimon (1 μM) were added to the cells in FBS-free medium and incubated for 12 h and 15 min respectively. Cells were then incubated with 10 μM forskolin (FSK) or 1 μM WIN 55,212-2 plus 10 μM FSK for 4 h. (B-C) Effects of PTX on cAMP accumulation in HEK 293 cells expressing CB1L222I (B) and CB1L222V (C). Cells were seeded 24 h prior to the addition of toxins. PTX (100 ng·mL−1) was added to the cells in FBS-free medium and incubated for 12 h respectively. Cells were then incubated with 1 μM WIN 55,212-2 plus 10 μM FSK for 4 h. The results are the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments carried out in triplicate. Statistical comparisons were made using Student's two-tailed, unpaired t-test. ***P < 0.001.

Table S1 Amino acid sequences of the second intracellular loop (ICL2) in the 168 G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), including 96 Gi, 45 Gs and 27 Gi/Gs dual coupled receptors.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Abadji V, Lucas-Lenard JM, Chin C, Kendall DA. Involvement of the carboxyl terminus of the third intracellular loop of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor in constitutive activation of Gs. J Neurochem. 1999;72:2032–2038. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0722032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams IB, Martin BR. Cannabis: pharmacology and toxicology in animals and humans. Addiction. 1996;91:1585–1614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 4th edn. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(Suppl 1):S1–S254. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allgeier A, Laugwitz KL, Van Sande J, Schultz G, Dumont JE. Multiple G-protein coupling of the dog thyrotropin receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1997;127:81–90. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(96)03996-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anavi-Goffer S, Fleischer D, Hurst DP, Lynch DL, Barnett-Norris J, Shi S, et al. Helix 8 Leu in the CB1 cannabinoid receptor contributes to selective signal transduction mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25100–25113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703388200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora KK, Sakai A, Catt KJ. Effects of second intracellular loop mutations on signal transduction and internalization of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22820–22826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.22820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bash R, Rubovitch V, Gafni M, Sarne Y. The stimulatory effect of cannabinoids on calcium uptake is mediated by Gs GTP-binding proteins and cAMP formation. Neurosignals. 2003;12:39–44. doi: 10.1159/000068915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayewitch M, Avidor-Reiss T, Levy R, Barg J, Mechoulam R, Vogel Z. The peripheral cannabinoid receptor: adenylate cyclase inhibition and G protein coupling. FEBS Lett. 1995;375:143–147. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01207-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KA, Dunlop J, Sanchez T, Silva M, Clarke WP. A conservative, single-amino acid substitution in the second cytoplasmic domain of the human Serotonin2C receptor alters both ligand-dependent and -independent receptor signaling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:1084–1092. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.131524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharatula M, Hussain T, Lokhandwala MF. Angiotensin II AT1 receptor/signaling mechanisms in the biphasic effect of the peptide on proximal tubular Na+,K+-ATPase. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1998;20:465–480. doi: 10.3109/10641969809053225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidaut-Russell M, Devane WA, Howlett AC. Cannabinoid receptors and modulation of cyclic AMP accumulation in the rat brain. J Neurochem. 1990;55:21–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb08815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonhaus DW, Chang LK, Kwan J, Martin GR. Dual activation and inhibition of adenylyl cyclase by cannabinoid receptor agonists: evidence for agonist-specific trafficking of intracellular responses. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;287:884–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouaboula M, Poinot-Chazel C, Marchand J, Canat X, Bourrie B, Rinaldi-Carmona M, et al. Signaling pathway associated with stimulation of CB2 peripheral cannabinoid receptor. Involvement of both mitogen-activated protein kinase and induction of Krox-24 expression. Eur J Biochem. 1996;237:704–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0704p.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calandra B, Portier M, Kerneis A, Delpech M, Carillon C, Le Fur G, et al. Dual intracellular signaling pathways mediated by the human cannabinoid CB1 receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;374:445–455. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabre O, Conklin BR, Brandon S, Bourne HR, Limbird LE. Coupling of the alpha 2A-adrenergic receptor to multiple G-proteins. A simple approach for estimating receptor-G-protein coupling efficiency in a transient expression system. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5730–5734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childers SR, Sexton T, Roy MB. Effects of anandamide on cannabinoid receptors in rat brain membranes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;47:711–715. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeaux Y, Ijzerman AP, Hill SJ. Coupling of the human A1 adenosine receptor to different heterotrimeric G proteins: evidence for agonist-specific G protein activation. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:705–714. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daaka Y, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Switching of the coupling of the beta2-adrenergic receptor to different G proteins by protein kinase A. Nature. 1997;390:88–91. doi: 10.1038/36362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demuth DG, Molleman A. Cannabinoid signalling. Life Sci. 2006;78:549–563. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittman AH, Weber JP, Hinds TR, Choi EJ, Migeon JC, Nathanson NM, et al. A novel mechanism for coupling of m4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors to calmodulin-sensitive adenylyl cyclases: crossover from G protein-coupled inhibition to stimulation. Biochemistry. 1994;33:943–951. doi: 10.1021/bi00170a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eason MG, Kurose H, Holt BD, Raymond JR, Liggett SB. Simultaneous coupling of alpha 2-adrenergic receptors to two G-proteins with opposing effects. Subtype-selective coupling of alpha 2C10, alpha 2C4, and alpha 2C2 adrenergic receptors to Gi and Gs. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15795–15801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felder CC, Briley EM, Axelrod J, Simpson JT, Mackie K, Devane WA. Anandamide, an endogenous cannabimimetic eicosanoid, binds to the cloned human cannabinoid receptor and stimulates receptor-mediated signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7656–7660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felder CC, Joyce KE, Briley EM, Glass M, Mackie KP, Fahey KJ, et al. LY320135, a novel cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist, unmasks coupling of the CB1 receptor to stimulation of cAMP accumulation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:291–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass M, Felder CC. Concurrent stimulation of cannabinoid CB1 and dopamine D2 receptors augments cAMP accumulation in striatal neurons: evidence for a Gs linkage to the CB1 receptor. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5327–5333. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05327.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillard CJ, Manna S, Greenberg MJ, DiCamelli R, Ross RA, Stevenson LA, et al. Synthesis and characterization of potent and selective agonists of the neuronal cannabinoid receptor (CB1) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:1427–1433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett AC, Fleming RM. Cannabinoid inhibition of adenylate cyclase. Pharmacology of the response in neuroblastoma cell membranes. Mol Pharmacol. 1984;26:532–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett AC, Qualy JM, Khachatrian LL. Involvement of Gi in the inhibition of adenylate cyclase by cannabimimetic drugs. Mol Pharmacol. 1986;29:307–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett AC, Johnson MR, Melvin LS, Milne GM. Nonclassical cannabinoid analgetics inhibit adenylate cyclase: development of a cannabinoid receptor model. Mol Pharmacol. 1988;33:297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett AC, Barth F, Bonner TI, Cabral G, Casellas P, Devane WA, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XXVII. Classification of cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:161–202. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, Cai K, Khorana HG. Mapping of contact sites in complex formation between light-activated rhodopsin and transducin by covalent crosslinking: use of a chemically preactivated reagent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4883–4887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051632998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrahian A, Watts VJ, Barker EL. D2 dopamine receptors modulate Galpha-subunit coupling of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:880–886. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.057620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston CA, Siderovski DP. Structural basis for nucleotide exchange on G alpha i subunits and receptor coupling specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2001–2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608599104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Krsmanovic LZ, Mores N, Navarro CE, Arora KK, Catt KJ. An agonist-induced switch in G protein coupling of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor regulates pulsatile neuropeptide secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2969–2974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0535708100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert DM. [Medical use of cannabis through history] J Pharm Belg. 2001;56:111–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler OA, Miggin SM, Kinsella BT. Protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation of serine 357 of the mouse prostacyclin receptor regulates its coupling to G(s)-, to G(i)-, and to G(q)-coupled effector signaling. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33596–33607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Busillo JM, Benovic JL. M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated signaling is regulated by distinct mechanisms. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:338–347. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.044750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maneuf YP, Brotchie JM. Paradoxical action of the cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2 in stimulated and basal cyclic AMP accumulation in rat globus pallidus slices. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:1397–1398. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature. 1990;346:561–564. doi: 10.1038/346561a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro O, Lameh J, Hogger P, Sadee W. Hydrophobic amino acid in the i2 loop plays a key role in receptor-G protein coupling. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:22273–22276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu-Shaar M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature. 1993;365:61–65. doi: 10.1038/365061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanoff C, Koppensteiner R, Yang Q, Fuerst E, Ahorn H, Freissmuth M. The carboxyl terminus of the Galpha-subunit is the latch for triggered activation of heterotrimeric G proteins. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:397–405. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.016725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negishi M, Irie A, Sugimoto Y, Namba T, Ichikawa A. Selective coupling of prostaglandin E receptor EP3D to Gi and Gs through interaction of alpha-carboxylic acid of agonist and arginine residue of seventh transmembrane domain. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16122–16127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.27.16122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco MA, Ward SJ, Childers SR. Identification of cannabinoid receptors in cultures of rat cerebellar granule cells. Brain Res. 1993;603:102–110. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91304-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palczewski K, Kumasaka T, Hori T, Behnke CA, Motoshima H, Fox BA, et al. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: a G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2000;289:739–745. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette JJ, Wang HY, Bakshi K, Olmstead MC. Cannabinoid-induced tolerance is associated with a CB1 receptor G protein coupling switch that is prevented by ultra-low dose rimonabant. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18:767–776. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282f15890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters MF, Scott CW. Evaluating cellular impedance assays for detection of GPCR pleiotropic signaling and functional selectivity. J Biomol Screen. 2009;14:246–255. doi: 10.1177/1087057108330115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto JC, Potie F, Rice KC, Boring D, Johnson MR, Evans DM, et al. Cannabinoid receptor binding and agonist activity of amides and esters of arachidonic acid. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:516–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prioleau C, Visiers I, Ebersole BJ, Weinstein H, Sealfon SC. Conserved helix 7 tyrosine acts as a multistate conformational switch in the 5HT2C receptor. Identification of a novel ‘locked-on’ phenotype and double revertant mutations. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:36577–36584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206223200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarker KP, Maruyama I. Anandamide induces cell death independently of cannabinoid receptors or vanilloid receptor 1: possible involvement of lipid rafts. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:1200–1208. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3055-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider TD, Stephens RM. Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6097–6100. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto Y, Nakato T, Kita A, Takahashi Y, Hatae N, Tabata H, et al. A cluster of aromatic amino acids in the i2 loop plays a key role for Gs coupling in prostaglandin EP2 and EP3 receptors. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11016–11026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307404200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura T, Kodaka T, Kondo S, Tonegawa T, Nakane S, Kishimoto S, et al. 2-Arachidonoylglycerol, a putative endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand, induces rapid, transient elevation of intracellular free Ca2+ in neuroblastoma x glioma hybrid NG108-15 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;229:58–64. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura T, Kodaka T, Kondo S, Nakane S, Kondo H, Waku K, et al. Is the cannabinoid CB1 receptor a 2-arachidonoylglycerol receptor? Structural requirements for triggering a Ca2+ transient in NG108-15 cells. J Biochem. 1997;122:890–895. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodoropoulou MC, Bagos PG, Spyropoulos IC, Hamodrakas SJ. gpDB: a database of GPCRs, G-proteins, effectors and their interactions. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1471–1472. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulfers AL, McMurry JL, Miller A, Wang L, Kendall DA, Mierke DF. Cannabinoid receptor-G protein interactions: G(alphai1)-bound structures of IC3 and a mutant with altered G protein specificity. Protein Sci. 2002;11:2526–2531. doi: 10.1110/ps.0218402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel Z, Barg J, Levy R, Saya D, Heldman E, Mechoulam R. Anandamide, a brain endogenous compound, interacts specifically with cannabinoid receptors and inhibits adenylate cyclase. J Neurochem. 1993;61:352–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker JL, Feller DB, Tang XB, Defino MC, Namkung Y, Lyssand JS, et al. Disease-causing mutation in GPR54 reveals the importance of the second intracellular loop for class A G-protein-coupled receptor function. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31068–31078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805251200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade MR, Tzavara ET, Nomikos GG. Cannabinoids reduce cAMP levels in the striatum of freely moving rats: an in vivo microdialysis study. Brain Res. 2004;1005:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Zhao H, Qiu Y, Loh HH, Law PY. Src phosphorylation of micro-receptor is responsible for the receptor switching from an inhibitory to a stimulatory signal. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1990–2000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807971200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.