Burden of Child and Adolescent Mental Disorders

In the last half-century, new techniques have substantially reduced the morbidity and mortality associated with “somatic” health problems: however, there is a “new morbidity” of behavioral and mental disorders on the rise.1 The vast majority of mental disorders have an initial onset before age 24, and 20% of children have experienced a mental health disorder.2–7 Most mental disorders are characterized by a relapsing and remitting pattern over a lifetime (16.6% for major depression, 13.2% for alcohol abuse), and they are among the top 10 causes of lost disability adjusted life years 5, 8 1, 4 8–9. Given this, reducing the burden of child and adolescent mental disorder is a major public health priority.10

Need for Alternative Strategies to Address Child and Adolescent Mental Disorder Burden

Many promising diagnostic approaches and treatment strategies, including psychotherapy and pharmacologic approaches, have been developed to address the morbidity and mortality associated with mental disorders.11 Psychotherapy interventions in both school-based treatment and preventive interventions have demonstrated small to moderate effect sizes and number needed to treat values in the 4–10 range.12–13 Despite these improvements, cost containment strategies for mental health have increased pressure on health care professionals to provide more services at lower costs.14 Many new approaches, such as collaborative care and dual treatment with antidepressant medications and psychotherapy, improve outcomes for patients, particularly for ethnic minorities, but at an additional cost.15–17 18 Telemedicine offers the prospect of facilitating such reconfiguration of services to address geographic and supply-based access issues.11, 19 While television has previously been used for psycho-education,20 both the interactivity of web-based treatment and the ability to simultaneously deliver services to large numbers of clients make Internet interventions a particularly appealing model for prevention, first-step treatment, or as a companion to existing treatment. In addition, contemporary children and adolescents exhibit high levels of computer literacy, which leads us to believe that Internet interventions would be an effective way of providing children and adolescents with treatment.

Internet Intervention Models

Internet interventions are developed around theoretically grounded concepts and offer good prospects for improving health related behaviors. Several recent publications have summarized key concepts for Internet interventions, such as the importance of motivation of participants, participant participation, website design, and support for participation.21–23 Children and adolescents live and develop within an ecological context of family, school/peers and community experiences. They have much less control over their environment than adults do, and are also undergoing much more rapid developmental changes than adults are.10 Additionally, children and adolescents may be more likely to respond to alternative delivery strategies such as internet based video or games.24–25 People of this age also warrant special protection and concern with regard to use of the Internet. In short, we need to consider Internet intervention within the unique frame of child and adolescent ecology and experiences.

Evidence for Benefit of Internet Interventions for Health

A substantial body of literature supports the use of Internet-based approaches to treat a range of mental disorder symptoms in adults and somatic health problems in adolescents.19, 26–27 Several randomized trials have demonstrated efficacy in reducing depression and/or anxiety symptoms,26, 28 eating and alcohol abuse disorders,29–30 and improving knowledge/attitudes (psycho-education) in adults.31 Internet interventions have been developed to address somatic health problems in the youth population, including: obesity, smoking, HIV/AIDS risk, and sexual risk.32–38 Despite measurable improvements, Internet interventions remain dependent on contextual factors to spur motivation, with less than 10% of the population ready to engage a lifestyle change online at any given moment.39–40

Internet Interventions, Ecological Context, Development and Social Capital Formation

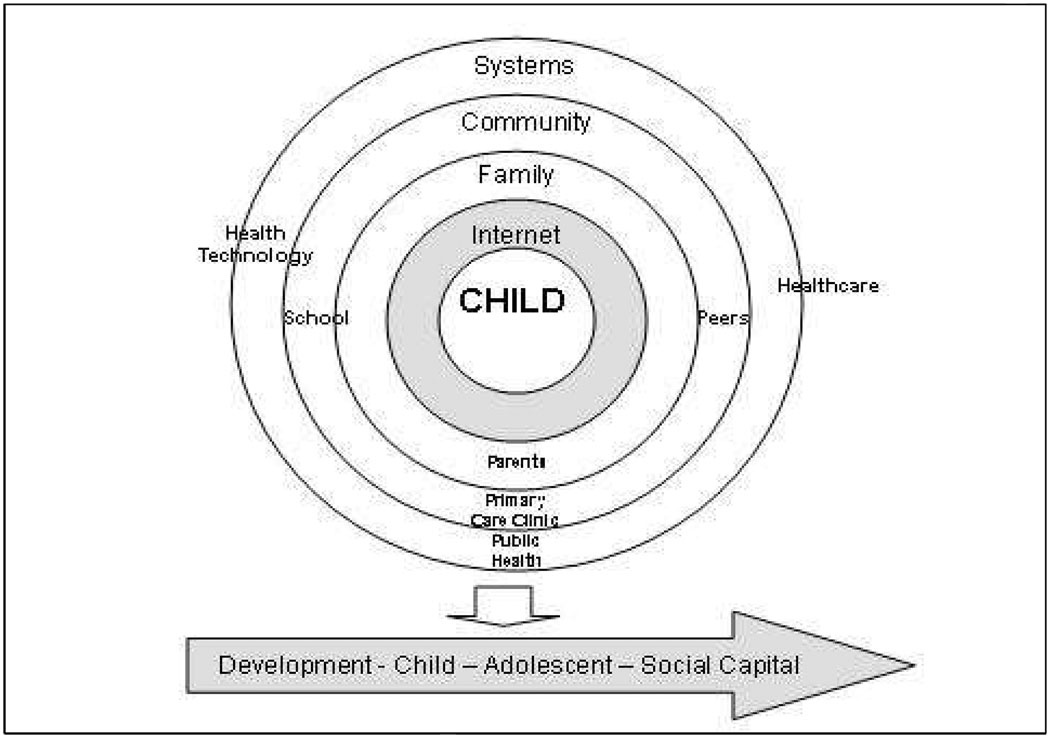

We present an overview of this emerging literature of Internet-based interventions for child mental health within both a psychopathology (disorder based) and an ecological and developmental framework (Figure 1).41 Internet-based interventions for child and adolescent mental health were conceptualized as fully integrated components of the ecological developmental process that leads to social capital formation.42 These include health promotion, prevention, and treatment interventions that work with and seek to influence the child through family, community and system contexts.10 For example, adolescents could be screened for risk of depression in primary care, and through the primary care provider be engaged with an Internet-based prevention strategy that includes a parent training component–a synergistic combination of treating the adolescent within family, Internet and community resources.43–45 We summarize progress in this area by disorder (as well as for general mental health promotion) and within an ecological and developmental context and also offer recommendations for future directions.

Figure 1.

Ecological and Developmental Model of Child Internet Mental Health Interventions

Review Methods

We systematically searched Medline and PsycInfo databases for unique intervention papers. The search was guided by MESH (for Medline) and subject terms (for PsycInfo) that covered the topics of “mental health” in combination with both “intervention” terms and “Internet” terms. These formal data base searches were supplemented by examining the citation lists of acquired articles, hand-searching abstract listings of two major conferences in Internet mental health held in 2009, and consulting a list of field experts. Data extracted from acquired articles focused on clinical measures of the disorders specific to each publication. Some data on psycho-education measures were also included. Individual effect sizes (ES, also known as standard mean difference) were calculated between intervention and control groups, and also pre- and post-intervention for disorder-specific measures (usually symptom measures). We chose to include pre/post effect sizes for the following reasons: 1) some studies were single arm pre/post design and 2) many randomized controlled trials utilized active controls that may have led to an underestimate of treatment effects. Not all of the studies included all measures required to calculate all effect sizes. Number needed to treat (NNT) values were calculated for dichotomous outcome data whenever it was available (not all studies included dichotomous outcomes). While individual effect sizes and NNTs are shown in table 1, the review also includes mean effect sizes and NNTs for each disorder category. The data for mean effect sizes and NNTs are not included in a reference table, but a more detailed description is available through the corresponding author. Where appropriate, psycho-education effects sizes were calculated.

Table 1.

Child and Adolescent Internet Interventions Content and Outcomes

| Citation | Age/Gender | N | Study Type | Control | Setting/Goal | Content | Outcomes: Effect Size (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression Studies | |||||||

| O'Kearney et al. '(2009); all female study; MoodGYM | 15–16 years female: 100% | 157 | RCT | MoodGym vs. normal school health class | School/Prevention | CBT Education | CESD: ES=.18 (−0. to 0.50) ‡0.23 (−0.11 to 0.57) |

| O'Kearney et al. (2006); all male study; MoodGYM | 15–16 years male: 100% | 78 | RCT | MoodGym vs. normal school health class | Prevention, psychoeducation, treatment | CBT Education | CESD: ES=0.11(−.46 to 0.68) NNT (risk of depression)= 9.10 |

| Calear et al. (2009); MoodGYM | 14.34 (0.75) female:55.9% | 1477 | RCT | MoodGym vs. normal school health class | Prevention, psychoeducation, treatment | CBT Education motivation for change | CESD: total participants; ES=0.15 (0.03 to 0.26) ‡0.05 (−0.07 to 0.18) |

| CESD: male participants; ES=0.40 (0.23 to 0.56) ‡0.21 (−0.07 to 0.18) | |||||||

| RCMAS: total participants; ES=0.15 (0.03 to 0.26) ‡0.31 (0.18 to 0.43) | |||||||

| NNT (incidence of anxiety)=71.43 | |||||||

| NNT (incidence of depression)= 14.93 | |||||||

| Van Voorhees et al. (2009); Project CATCH-IT | 17.39 (2.04) female:56.6% | 84 | RCT | Motivational Interview vs. Brief Advice | Primary Care/Prevention | CBT IPT and BA motivational interview | CESD-10: ES=0.18 (−0.25 to 0.61) ‡0.54 (0.11 to 0.97) NNT (depressive episode)= 5.60 |

| Van Voorhees et al. (2008); Project CATCH-IT | 17.44 (2.04) female:56.6% | 84 | RCT | Motivational interview vs. Brief Advice | Prevention | CBT IPT and BA motivational interview | Perceived social support: ES=0.20 (−0.39 to 0.77) ‡ES=0.76 (0.18 to 1.32) |

| Anxiety Studies | |||||||

| March et al. (2009); BRAVE-online | 9.45 (1.37) female:54.8% | 73 | RCT | BRAVE Program vs. wait-list | Treatment psychoeducation | CBT | CESD: ES=0.08 (−.43 to 0.59) ‡0.24 (−0.27 to 0.75) |

| SCAS-C: ES=0.18 (−.34 to 0.69) ‡ES=0.91 (0.37 to 1.43) | |||||||

| SCAS-P: ES=0.31 (−.20 to 0.82) ‡0.94 (0.40 to 1.46) | |||||||

| NNT (remission of anxiety)= −5.08 | |||||||

| Spence et al. (2006) | 9.93 (1.74) female:41.7% | 72 | RCT | online intervention vs. wait list | Treatment psychoeducation | CBT Education | RCMAS: ES=0.42 (−0.15 to 0.98) ‡0.78 (0.21 to 1.32) |

| NNT (remission of anxiety)= −2.57 | |||||||

| Van Vliet and Andrews (2009); Climate Schools | 13 years unknown | 653 | Clinical trial | Climate Schools vs. control schools | Treatment psychoeducation | Education | Knowedge: ES=0.36 Support seeking coping ES=0.02 Avoidant coping ES=.22 Total difficulties ES=0.16 |

| Eating Disorder Studies | |||||||

| Heinicke et al. (2007); My body, My life | 14.4 (1.53) female:100% | 83 | RCT | Intervention vs wait list | Prevention | CBT motivation for change | EDI-Bulimia: ES=0.45 (0.02 to 0.91) ‡0.48 (0.01 to 0.95) |

| Brown et al. (2009); Student Bodies | 15.1 (0.4) female:100% | 153 Children | RCT | Intervention vs. normal health education | Prevention | Adult Ed, Child Ed CBT,Social-Support | EDI-Bulimia: ES=0.13 (−0.20 to 0.91) ‡0.10 (−.18 to 0.37) |

| 69 parents | Knowledge (Child) ES=0.64 (0.29–0.98) ‡0.93 (.63 to 1.21) | ||||||

| PACS(Healthy Outlook); ES=0.29 (0.22 to 0.79) ‡0.74 .11 to 1.33) | |||||||

| Substance Abuse Studies | |||||||

| Newton et al. (2009); Climate Schools | 13.08 (0.58) female:40% | 764 | RCT | Online intervention vs. normal health class | Prevention Treatment Psychoeducation | Cannibus Alcohol education | Alcohol knowledge ES=0.78 (0.64 to 0.93) ‡0.79 (0.65 to 0.94) |

| Weekly Alcohol Consumption 0.25 (0.11 to 0.39) ‡0.05 (−0.09 to 0.19) | |||||||

| Health Promotion | |||||||

| Fukkink and Hermanns (2009); Kinder-telefoon | 13.8 (2.0) female:80% | 339 | non-randomized trial | telephone chat- users | wellness promotion | problem-solving, Social-support | Well Being (chat vs. phone); ES= 0.15 (0.01 to 0.28) ‡0.63 (.47 to .78) |

| Perceived Burden; ES= 0.04 (−0.10 to 0.17) ‡0.46 (0.30 to 0.60) | |||||||

| Santor et al. (2009); YouMagazine | grades 7–12 unknown | 558 | non-randomized trial | non-users of Internet program | Health Information | psychoeducation | Relative risk of visiting mental health specialist =2.19 (1.22 to 3.92) >11,000 logins in 1 year |

| Nicholas (2010); Reach Out website | ages 16–25 unknown | 1,016 | convenience sample, Survey/Description | none | Prevention Treatment Education | Education, CBT, Gaming, social support | >7,000,000 logins since 1998 After visiting Reach Out, 38% of people contact a mental health professional |

| Michaud and Colom (2009); "Ciao" website | 13–18 63% female | 257 | convenience sample, Survey/Description | none | Treatment Education | Education, Professional, interaction forum | 83% of users felt satisfied with the content |

indicates pre/post effect size (as compared to between group effect sizes). ES= effect size. NNT= number needed to treat. CESD=Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. RCMAS= Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale. EDI= Eating Disorder Inventory. CBT= Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.

Intervention for Specific Mental Disorders

Depression

We found articles describing two main interventions for childhood depression, MoodGym and Project CATCH-IT (Table 1).44, 46–48 Both interventions include a focus on Cognitive Behavioral Psychotherapy approaches, but CATCH-IT also incorporates Interpersonal Psychotherapy components(. The MoodGym studies are done in schools, while in CATCH-IT the adolescents are engaged via a primary care encounter. The mean between-group effect sizes for depression intervention are small (Mean ES= 0.20). The pre/post effect sizes also fall into the smaller range (Mean ES= 0.26). The average number needed to treat is moderate (Mean= 9.88). MoodGym uses animation as a teaching adjunct, while CATCH-IT utilizes adolescent narratives. Pre/post effect sizes are larger for samples with depression symptoms (such as “indicated prevention (those with early symptoms, but not have full criteria and subgroups of symptomatic persons within “universal” prevention model studies (entire school exposed to interventions) than for samples with of largely asymptomatic adolescents (universal prevention).

MoodGym (moodgym.anu.edu.au) uses modules based on cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) both to provide pertinent information and to directly address depressive symptoms in a youth population.46–48 The program comprises five modules, focusing on prevention, education, and treatment using CBT, and has undergone three randomized clinical trials comparing it to routine health class participation alone. In the largest (male and females) randomized controlled trial (1477 participants, mean age 14.34 (SD=0.75)), the MoodGym program was compared with a wait-list control group (received health class).46 Post-intervention, the total Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scales (CES-D) scores for the intervention group were slightly reduced (Effect Size = 0.15), but the difference was significant for male participants, yielding a larger CES-D effect size (ES = 0.40). Results from the two smaller randomized controlled trials for the mood gym were found in single-gender school setting contrasted with the larger, mixed-gender study.47–48 Effect sizes for CES-D scores for the all-male study were small to moderate (depending on participation level), and not significant, but there was a significantly lower likelihood of being classified as at risk for depression (NNT=9.1).47 The other was an all-female study with 157 participants where effects size were small immediately post study, but moderate at 20 week follow-up.48.

Project CATCH-IT (http://catchit-public.bsd.uchicago.edu) is a primary care-based interventional website that focuses on the prevention of adolescent depression and uses principles based on CBT, Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) and Behavioral Activation (BA). 44, 49 The 84 participants were recruited via screening in primary care. These participants had a mean age of 17.39 years (SD=2.04), and were randomized to either a motivational interview group (MI, 5–10 minute physician interview) to a brief advice group (BA, 1–2 minutes) in preparation for Internet site use. While the MI group demonstrated greater participation, both group engaged the Internet site substantially and between group differences were small. However, both groups demonstrated moderate pre/post effect sizes for depressed mood and the MI group had significantly fewer depressive episodes at 3 month follow-up.44

Anxiety

Three interventions were identified focusing on anxiety and one on both depression and anxiety. The studies include one pre/post50 design and three randomized clinical trials,46, 51–52 with both wait list and health class control groups (mean between group effect size ES=0.24 and a mean pre/post ES =0.64). The three interventions without direct face-to-face therapeutic contact report small effect sizes, while the study done in a clinic setting, as a component of a standard intervention, reports moderate effect sizes. All the interventions except one (Spence) use animation to illustrate CBT concepts, while one (Climate schools) uses animated narratives. Interestingly, the intervention with the least interactivity (Spence) also had the largest effect size.

BRAVE Online (brave.psy.uq.edu.au) is a program designed to treat childhood anxiety issues and provide participants with psycho-educational information.51 Child sessions contain modules based on CBT and anxiety reduction strategies. Parent sessions are focused on psycho-education regarding child anxiety, and strategies for overcoming it. The study included 73 participants with pre-existing anxiety disorders, ages 7–12 (mean age of 9.45 years (SD=1.37)). Participants were recruited through public announcements. The children and families were randomly assigned to either an intervention group or a non-treatment control group. There are small, non-significant differences between group effect sizes, while the intervention arm did demonstrate moderate and significant effects sized for improvement in anxiety (pre/post analysis).51.

In another randomized controlled trial, Spence combines Internet interventions with traditional clinical treatment within a mental health clinic setting. 52 Among the participants were 72 children and adolescents (mean age=9.93 years (SD=1.74)) with pre-existing anxiety disorders.52 After recruitment from the clinic, they were randomly assigned to either clinic-only treatment with face-to-face counseling, or to treatment which has half of the sessions via the Internet. The modules of intervention are based on CBT and psycho-education. Comparisons of post-treatment anxiety scores for children and adults yield small-to-medium effect sizes between groups (SCAS-C, ES=0.09; SCAS-P, ES= 0.48 and NNT=2.57) for likelihood of having an anxiety diagnosis.52

A final study addresses anxiety using the ClimateSchools program.50 This intervention is delivered within the school setting in place of normal health classes, and is offered as preventative intervention. The study was organized with a pre/post design. ClimateSchools focuses on psycho-education and presents its content in an online, cartoon format. 653 eighth graders were included in the study, and participants were randomly assigned to either the treatment group or health class as usual. As stated by the authors, there were no significant differences observed between groups. Due to the fact that raw data were not reported, effect sizes could not be calculated. The authors did report an effect size of 0.36 between the interventions pre- and post-treatment anxiety knowledge.50

Eating Disorders

Two eating disorder preventative interventions were identified: My Body, My Life; Body Image Program for Adolescent Girls and the Student Bodies Program.53–54 The mean between-group effect sizes is in the small to moderate range (ES= 0.29), and the pre/post effect size is the same (ES= 0.29). Both programs used CBT elements and discussion formats, but My Body, My Life focuses on synchronous online group psychotherapy, while the Student Bodies Program is built around self-directed learning behavior change and an asynchronous discussion board. (53–54)

My Body, My Life is a program developed to prevent eating disorders in adolescents.54 CBT=based treatment is given at home, via an Internet site. Sessions were moderated online by a therapist. In this intervention, participants work through an online manual addressing body image and eating issues. Eighty-three female adolescents with self-identified body image concern (mean age of 14.4 (SD= 1.53)) were recruited online and randomly assigned to either a delayed treatment group or to active intervention. At the conclusion of the program, there were moderate effect sizes between groups for both bulimia (EDI-Bulimia, ES= 0.45) and depression scores (Beck Depression Scale, ES= 0.43).54

The Student Bodies program, an intervention for adolescent eating disorders, utilizes a combined CBT and psycho-educational website, and focuses on both adolescents and their parents in a school setting.53 The website also includes a patrolled social networking aspect that allows participants to express issues and share stories. 153 adolescents (mean age of 15.1 (SD=0.4)) and 69 parents were assigned to either active intervention or wait-list control. Small-to-medium effect sizes were observed for both adolescent and parent outcomes. Intervention group adolescents showed an effect size of 0.13 for bulimia and 0.64 for knowledge at post-intervention as compared to wait-list participants. Intervention group parents showed improvement in healthy outlook (ES= 0.29).53

Substance Abuse

The ClimateSchools program for prevention of substance abuse is an interactive website which uses animated narratives focusing on substance abuse education.55–56 Participants learn important information about the perils of alcohol and cannabis. The intervention group completes the program in place of their normal health class. 763 adolescents participated in the study. The mean age for all participants was 13.08 (SD= 0.58).55–56 Small-to-moderate effect sizes were observed between groups for knowledge of alcohol and cannabis and their use. Effect sizes of 0.78 and 0.77 were shown for alcohol and cannabis knowledge (data not shown in table), respectively. Small effect sizes were seen for weekly alcohol consumption (0.25) and frequency of cannabis use (0.25, data not shown in table).55–56

Health Promotion

A series of Internet interventions have been developed to provide broad mental health promotion in children and adolescents. We identified four such interventions in the published literature: Kindertelefoon (www.kindertelefoon.nl), YooMagazine (www.Yoomagazine.net), Ciao, and ReachOut (www.reach-out.org).57–61 These interventions primarily focus on providing health education, problem-solving strategies, and sources where users could seek help. With the exception of one pre/post observational study.58, these articles are surveys that outline modalities, describe frequencies of use, and display user satisfaction with the programs.57, 59–61 Half of the survey articles provide some form of social support, and one also utilizes a CBT-based game. In post-use surveys, the majority of interventions are ranked as either helpful or useful by users. The YooMagazine study design demonstrated that when offered a public health amenity, about a quarter of adolescents will engage it61. All the interventions demonstrated some evidence for the promotion of mental health seeking and users' satisfaction with information provided. 58–61.

The Kindertelefoon program was studied with a pre/post design.58 Users who log on to the website are given the opportunity to interact with a trained health care volunteer via chat and an interactive forum. Intervention strategies were based upon providing children with an opportunity to express their emotions, problems, and situations as well as a space for problem solving. Each conversation has five elements: 1) establishing contact, 2) clarifying the child’s story, 3) determining the goal of the conversation, 4) developing the goal of the conversation and 5) closing the conversation. Each volunteer has 40 hours of training and fifteen hours of supervision. In the study design, online chatters were compared to those who selected the traditional telephone-based chat service. In between-group comparisons, while the online chatters were had more severe levels of symptoms of mental disorders, outcome at follow-up did not differ. Users displayed moderate improvements between pre- and post-chat surveys in regard to perceived burden (ES= 0.46) and wellbeing (ES= 0.62). These effects appeared to continue through the one-month follow up (ES= 0.52 for both scales).58

Free-standing websites, such as YooMagazine, are created to promote health literacy, foster early detection of mental health problems, and encourage help seeking among its users.61 The Internet site uses a magazine format with monthly focus articles, topical information sheets (based on existing public health materials), and a questions/response board. Adolescents pose questions that are answered by experts. The intervention was studied by enrolling 1775 students grades 7–12 who completed both baseline and follow-up surveys and who had access to the site over a 1-year period. Overall, 25.6% of respondents utilized the Internet site, recording a mean of 21.27 visits (SD=62.40), and posted a mean of 8.32 (SD-12.05) questions. Questions about relationships and sexuality comprised the majority (67%) while only a minority involved mental health (7%). Greater mental health symptoms predicted greater use of the Internet site. Students who visited the site were more likely to have visited a mental health specialist in the last year and to report a reduction in school-related worries than non-site users(61).

ReachOut! (www.reach-out.org) is a website with a multifaceted approach to improving adolescent mental health that aims to increase literacy, strengthen meaningful participation and relationships, enhance skills that bolster resilience, and improve help seeking among youth60. To accomplish this, ReachOut! uses 1) research related information prepared by youth volunteers, 2) an online community forum, 3) games based on CBT, 4) self-expression, 5) portable digital media (podcasts, short message service (SMS)), and 6) ReachOut Professional (information for health professionals about the program. ReachOut has had over seven million visitors.60 A convenience sample of visitors to the site reported favorable ratings of knowledge and support for health seeking.

Ciao is a website that provides health and leisure information and the locations of medical and mental health providers. It allows users to ask questions of health professionals while remaining anonymous. During the year of publication, 4,382 questions were posted with 20% with regard to general health, 14% interpersonal relations, 10% substance abuse and 3% interpersonal violence. In a convenience survey of users, the great majority reported they would recommend it to a friend and 35% reported finding a useful address. 59

Ecological Context and Developmental Considerations

Child and Family Characteristics

Socio-demographics: Studies were conducted in many countries around the world. The greatest number of publications were from groups in Australia (9), followed by the United States (3). One article each came from the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Canada. Out of the 11 interventional trial studies, 8 out of 11 (72.7%) listed participants as primarily from middle- to upper-class families.44, 47–49, 51–53, 55–56 Health promotion survey articles did not provide information regarding user demographics. Many of the studies did not describe the ethnicity of participants, but the three that did indicated that 40% or more of their patient population was non-white.44, 49, 53 Three studies indicated high levels of children living with both parents (78.3%–85.0%).46, 51–52 Overall, information provided in these articles directs us to believe that the majority of interventions were tested in middle to upper class populations.

Ecological setting

Intervention and Internet sites were introduced in a variety of settings. Six interventions were introduced to young people at school. Four of the interventions, primarily the health promotion sites, were free-standing.58–61 Two studies combined home and primary care settings,44, 49 and two combined home and mental health specialist settings.51–52 One study was used only in a mental health care provider’s office57 as a supplement to regular treatment. For the most part, the school and primary care interventions were preventative while the mental health clinic models were for treatment. Free-standing programs tended to be public health amenities focused on mental health promotion.

A structured setting for introduction of the Internet intervention may increase participation and improve outcomes. For instance, in the randomized controlled trials testing the MoodGym program in schools, all participants at least logged on once (although only 30% to 40% of participants completed ≥ 3 out of 5 modules). Increased participation was associated with improved outcomes in one of the studies.46–48 Similarly, in a health care setting, the authors of Project CATCH-IT reported that between 77.5% and 90% of participants visited the site, and that those people spent between 98.40 and 143.70 minutes exploring it.44, 49 Additionally, MoodGym studies demonstrated different results for boys and girls depending on the peer setting. Outcomes for boys and girls varied by whether the program was introduced in a mixed or single gender school: boys had more favorable outcomes in mixed gender settings, while girls had more favorable outcomes in single gender settings.46–48 Another contextual influence might be pre-conditioning: specifically, whether or not there is also engagement with a medical professional. In the CATCH-IT study, the combination of a primary care physician's motivational interview and an Internet program appeared to be superior to only receiving brief advice and an Internet program in increasing participation and preventing depressive episodes.44

Internet Site and Development

Instructional models

Most of the programs included some form of CBT or other behavioral therapy and utilized a variety of learning strategies. The most commonly used approaches were interactive features such as homework, quizzes, or forums that were intended to engage participant interest. Fourteen interventions included some form of interactivity.44, 46–49, 51–54, 57–61 Eight interactive interventions included some form of quiz or homework.44, 46–49, 51–53 Seven programs required students to do problem solving exercises.44, 46–49, 51, 53 The Internet site developers incorporated learning experiences intended to appeal to children and adolescents including animation, peer forums and question and answer boards, and games. These learning experiences have not been extensively discussed in recent conceptual models (with the exception of gaming) for site development or motivation to use the same in adults as well as greater levels of supervision.21, 24, 62–63

Support

Site navigation was addressed in a variety of ways. Some of the interventions directed users through the modules. This was achieved by either using a hard-coded program, or through the direct instruction of a mediating health care specialist. Three of the interventions provided direct chat contact with a health care provider,51–52, 54 while N= 6 were supervised via school class46–48, 50, 53, 55–56 and N=10 were supervised by an Internet or phone based therapist or social worker.44, 49–54, 58–60 Most intervention allowed for self-directive navigation (N= 8)44, 46–49, 60–61 while one has machine directed navigation.51

Safety

Given the sensitivity of child and adolescent psychiatry, it is not surprising that the majority of interventions included some form of support for users. While not all of the papers directly included information regarding safety and support, those that did not were school-based, and all of the school-based interventions were thought to be supervised by a school teacher. Some of the programs also included information on where to reach health professionals if necessary, and in some cases provided health surveys that were monitored for student distress.

Peer-to-Peer Interaction

Four programs provided a peer to peer forum for participants to ask questions, tell stories, and share positive ideas.53, 59–61 One of the studies included gaming aspects.60 These forums allowed participants to ask questions and share stories and coping strategies with one another. The involvement of parents, family and even peers in building resiliency in children and youth is supported in both empirical and observational studies.64–67 However, there are many concerns related to exposure to self-harm, negative affective states, or pessimistic cognitions of other peers.68–69 One program developed volunteer monitors (REACHOUT) and is consistent with successful approaches employed adults.70

Parent involvement

Five interventions included a parent component,44, 49, 51–53 with two of these including some form of parent-to-parent forum or Internet-based psychotherapy.53–54 Parent content focused primarily on mental health education. In addition, some of the programs provided parents with coping strategies that could be used to assist children dealing with specific symptoms (i.e. relaxation exercises to reduce anxiety71 (Spence et al.)). Brunning (The Student Bodies Program) reported in her eating disorder intervention that parent score improvements did not impact their daughters' scores on clinical ratings.

Comparison with Adult Studies and Child Face-to-Face Psychotherapy

The fact that child and adolescent Internet interventions demonstrate small-to-moderate effect sizes is a new finding. The effect sizes for depression (0.20), anxiety (0.24), eating disorders (0.29), substance abuse (0.25), and all studies (0.23) health promotion (ES=0.42) tended to be modestly smaller than those observed in adult Internet studies (depression, ES=0.41), anxiety, (ES=0.93), substance abuse (ES=0.40), eating disorders (ES=0.10), and health promotion/psycho-education (ES=0.20).26, 29, 72–73 However, most of studies included an active control condition such as a health class or even another version of the Internet intervention. This is suggested by the somewhat larger effect size for pre/post (0.40) than for between groups for all clinical measures (ES=0.23). These differences in effect size could be explained by lack of appropriate educational and behavior change approaches for children and adolescents. For example, more engaging learning approaches suited to children may have larger effect sizes, as was demonstrated in a meta-analysis of media (video based) interventions for child behavior problems (ES=0.67).25 Conversely, perhaps children and adolescents incorporate coping strategies more slowly into their emerging repertoires of response to external stressors than adults. The finding that effect sizes in this review are similar to face-to-face prevention intervention for depression (ES=0.26) and eating disorders (ES=0.26) suggests that the small effect sizes are characteristics of the current psychotherapy approaches, regardless of delivery, rather than of the Internet delivery mechanism.74–75 The NNT sizes for depression (9.88) and anxiety (26.36) were larger than their corresponding NNT values in face to face treatment (NNT= 7.1 and 3.0).76

Summary

We conducted a review of the literature with regard to child and adolescent mental health intervention, from which we identified twenty unique publications (sixteen highlighted in table 1) and twelve separate interventions. These interventions encompassed depression, anxiety, substance abuse, eating disorders, and mental health promotion. Studies were very heterogeneous with a wide range of study designs and comparison groups creating some challenges in interpretation. However, modest evidence was found that Internet interventions demonstrated benefits compared to controls and pre-intervention symptom levels. Interventions had been developed for a range of settings, but tended to recruit middle-class participants of European ethnicity. Internet interventions demonstrated a range of approaches towards engaging children and incorporating parents and peers into the learning process.

Conclusions

Our systematic review can best be characterized as an exploration of an entirely new field that has largely been developed in the last decade. An important strength of this review is range of setting, disorders and types of interventions identified in this review and the use of semi-quantitative methods to compare studies with one another and our results with those of prior studies. However, the studies identified focused primarily on internalizing disorders and only one involved in externalizing disorders. The reader should consider the following limitations: 1) lack of attention to broader aspects of the ecological context of the child, 2) narrow scope developmentally in terms of modalities, age range and disorders, and 3) variable attention to elements like supervision that will be critical in integrating Internet programs into systems of care. Despite the unanswered questions regarding internet mental health interventions for children and adolescents, a small body of literature is beginning to develop that supports its efficacy. While effect sizes in this study are small to moderate, that may be sufficient given their potential low cost and ease of distribution.

Future Directions

Increased attention to ecological context child development and intervention:

Increased use of primary settings to conduct Internet-based prevention research for mental disorders and mental health clinics to evaluate blended treatment approaches

Study designs that incorporate and evaluate contribution of family and peer participation, to outcomes.

Increasing diversity of study populations to encompass broader range of family and community contexts.

Expand the developmental range – modalities, age, and disorders

Study new delivery modalities such as gaming, virtual reality, and social media.

Develop and evaluate interventions across age range from infants to adolescents.

Develop and evaluate interventions for externalizing as well as internalizing disorders

Research to address integration of interventions into wider systems of care

Evaluation of the degree of professional supervision, including safety monitoring plans.

Improved study design that determine contribution to healthcare system including: a) control conditions such as treatment as usual, b) larger sample sizes to detect smaller effect sizes, and c) economic and cost effectiveness analyses

Exploration of economic costs and benefits in children and adolescents

Acknowledgments

Supported by a NARSAD Young Investigator Award, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Depression in Primary Care Value Grant, and a career development award from the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH K-08 MH 072918-01A2)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: Benjamin W. Van Voorhees has served as a consultant to Prevail Health Solutions, Inc, Mevident Inc, San Francisco and Social Kinetics, Palo Alto, CA, and the Hong Kong University to develop Internet-based interventions. In order to facilitate dissemination, the University of Chicago recently agreed to grant a no-cost license to Mevident Incorporated (3/5/2010) to develop a school-based version. Neither Dr. Van Voorhees nor the university will receive any royalties or equity. Dr. Van Voorhees has agreed to assist the company in adapting the intervention at the rate of $1,000/day for 5.5 days. The CATCH-IT Internet site and all materials remain open for public use and made freely available to healthcare providers at http://catchit-public.bsd.uchicago.edu/.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics. The new morbidity revisited: a renewed commitment to the psychosocial aspects of pediatric care. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. Pediatrics. 2001 Nov;108(5):1227–1230. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.5.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS, Skuban EM, Horwitz SM. Prevalence of social-emotional and behavioral problems in a community sample of 1- and 2-year-old children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001 Jul;40(7):811–819. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cassidy LJ, Jellinek MS. Approaches to recognition and management of childhood psychiatric disorders in pediatric primary care. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1998 Oct;45(5):1037–1052. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costello EJ, Pantino T. The new morbidity: who should treat it? J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1987 Oct;8(5):288–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heneghan A, Garner AS, Storfer-Isser A, Kortepeter K, Stein RE, Horwitz SM. Pediatricians' role in providing mental health care for children and adolescents: do pediatricians and child and adolescent psychiatrists agree? J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008 Aug;29(4):262–269. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31817dbd97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelleher KJ, McInerny TK, Gardner WP, Childs GE, Wasserman RC. Increasing identification of psychosocial problems: 1979–1996. Pediatrics. 2000 Jun;105(6):1313–1321. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.6.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams J, Klinepeter K, Palmes G, Pulley A, Foy JM. Diagnosis and treatment of behavioral health disorders in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2004 Sep;114(3):601–606. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997 May 24;349(9064):1498–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'connell M, Boat T, Warner K. Preventing Mental, Emotional and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graeff-Martins AS, Flament MF, Fayyad J, Tyano S, Jensen P, Rohde LA. Diffusion of efficacious interventions for children and adolescents with mental health problems. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008 Mar;49(3):335–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watanabe N, Hunot V, Omori IM, Churchill R, Furukawa TA. Psychotherapy for depression among children and adolescents: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007 Aug;116(2):84–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy LA, Newman E, De Thomas CA, Chun V. Effectiveness of school-based prevention and intervention programs for children and adolescents with emotional disturbance: a meta-analysis. J Sch Psychol. 2009 Apr;47(2):77–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wells KB. Cost containment and mental health outcomes: experiences from US studies. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1995 Apr;(27):43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Domino ME, Burns BJ, Silva SG, et al. Cost-effectiveness of treatments for adolescent depression: results from TADS. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 May;165(5):588–596. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07101610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbody S, Bower P, Whitty P. Costs and consequences of enhanced primary care for depression: systematic review of randomised economic evaluations. Br J Psychiatry. 2006 Oct;189:297–308. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.016006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katon WJ, Schoenbaum M, Fan MY, et al. Cost-effectiveness of improving primary care treatment of late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Dec;62(12):1313–1320. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Voorhees BW, Walters AE, Prochaska M, Quinn MT. Reducing Health Disparities in Depressive Disorders Outcomes between Non-Hispanic Whites and Ethnic Minorities: A Call for Pragmatic Strategies over the Life Course. Med Care Res Rev. 2007 Aug 31; doi: 10.1177/1077558707305424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hailey D, Roine R, Ohinmaa A. The effectiveness of telemental health applications: a review. Can J Psychiatry. 2008 Nov;53(11):769–778. doi: 10.1177/070674370805301109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paykel ES, Hart D, Priest RG. Changes in public attitudes to depression during the Defeat Depression Campaign. Br J Psychiatry. 1998 Dec;173:519–522. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.6.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crutzen R, de Nooijer J, Brouwer W, Oenema A, Brug J, de Vries NK. A conceptual framework for understanding and improving adolescents' exposure to Internet-delivered interventions. Health Promot Int. 2009 Sep;24(3):277–284. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Conceptualizing changes in behavior in intervention research: the range of possible changes model. Psychol Rev. 2006 Jul;113(3):554–583. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.113.3.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritterband LM, Thorndike FP, Cox DJ, Kovatchev BP, Gonder-Frederick LA. A behavior change model for internet interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2009 Aug;38(1):18–27. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9133-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilkinson N, Ang RP, Goh DH. Online video game therapy for mental health concerns: a review. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008 Jul;54(4):370–382. doi: 10.1177/0020764008091659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montgomery P, Bjornstad G, Dennis J. Media-based behavioural treatments for behavioural problems in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD002206. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002206.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersson G, Cuijpers P. Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009 Dec;38(4):196–205. doi: 10.1080/16506070903318960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tate DF, Finkelstein EA, Khavjou O, Gustafson A. Cost effectiveness of internet interventions: review and recommendations. Ann Behav Med. 2009 Aug;38(1):40–45. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9131-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuijpers P, Marks IM, van Straten A, Cavanagh K, Gega L, Andersson G. Computer-aided psychotherapy for anxiety disorders: a meta-analytic review. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009 Jun;38(2):66–82. doi: 10.1080/16506070802694776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riper H, Kramer J, Smit F, Conijn B, Schippers G, Cuijpers P. Web-based self-help for problem drinkers: a pragmatic randomized trial. Addiction. 2008 Feb;103(2):218–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zabinski MF, Wilfley DE, Pung MA, Winzelberg AJ, Eldredge K, Taylor CB. An interactive internet-based intervention for women at risk of eating disorders: a pilot study. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;30(2):129–137. doi: 10.1002/eat.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donker T, Griffiths KM, Cuijpers P, Christensen H. Psychoeducation for depression, anxiety and psychological distress: a meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2009;7:79. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-7-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ybarra ML, Kiwanuka J, Emenyonu N, Bangsberg DR. Internet use among Ugandan adolescents: implications for HIV intervention. PLoS Med. 2006 Nov;3(11):e433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lou CH, Zhao Q, Gao ES, Shah IH. Can the Internet be used effectively to provide sex education to young people in China? J Adolesc Health. 2006 Nov;39(5):720–728. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirk SF, Harvey EL, McConnon A, et al. A randomised trial of an Internet weight control resource: the UK Weight Control Trial [ISRCTN58621669] BMC Health Serv Res. 2003 Oct 29;3(1):19. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patten CA, Croghan IT, Meis TM, et al. Randomized clinical trial of an Internet-based versus brief office intervention for adolescent smoking cessation. Patient Educ Couns. 2006 Dec;64(1–3):249–258. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wantland DJ, Portillo CJ, Holzemer WL, Slaughter R, McGhee EM. The effectiveness of Web-based vs. non-Web-based interventions: a meta-analysis of behavioral change outcomes. J Med Internet Res. 2004 Nov 10;6(4):e40. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.4.e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van den Berg MH, Schoones JW, Vliet Vlieland TP. Internet-based physical activity interventions: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9(3):e26. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.3.e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walters ST, Wright JA, Shegog R. A review of computer and Internet-based interventions for smoking behavior. Addict Behav. 2006 Feb;31(2):264–277. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evers KE, Cummins CO, Prochaska JO, Prochaska JM. Online health behavior and disease management programs: are we ready for them? Are they ready for us? J Med Internet Res. 2005 Jul 1;7(3):e27. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.3.e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verheijden MW, Jans MP, Hildebrandt VH, Hopman-Rock M. Rates and determinants of repeated participation in a web-based behavior change program for healthy body weight and healthy lifestyle. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9(1):e1. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.1.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atkins MSAJ, Jackson M, McKay MM, Bell CC. An ecological model for school-based mental health services. Paper presented at: 13th Annual Research Conference Proceedings, A system of care for children’s mental health: Expanding the Research2001; The Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, Research and Training Center for Children’s Mental Health; Tampa. University of South Florida; [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris K. An integrative approach to health. Demography. 2010;47(1):1–22. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Voorhees BW, Paunesku D, Gollan J, Kuwabara S, Reinecke M, A B. Predicting future risk of depressive episode in adolescents: the Chicago Adolescent Depression Risk Assessment (CADRA) Annals of Family Medicine. 2008;6(6):503–511. doi: 10.1370/afm.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Voorhees BW, Fogel J, Reinecke MA, et al. Randomized clinical trial of an Internet-based depression prevention program for adolescents (Project CATCH-IT) in primary care: 12-week outcomes. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009 Feb;30(1):23–37. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181966c2a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Voorhees BW, Melkonian S, Marko M, Humensky J, Fogel J. Adolescents in primary care with sub-threshold depressed mood screened for participation in a depression prevention study: Co-morbidity and factors associated with depressive symptoms. The Open Psychiatry Journal. 2010;4:10–18. 4, 10–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Calear AL, Christensen H, Mackinnon A, Griffiths KM, O'Kearney R. The YouthMood Project: a cluster randomized controlled trial of an online cognitive behavioral program with adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009 Dec;77(6):1021–1032. doi: 10.1037/a0017391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O'Kearney R, Gibson M, Christensen H, Griffiths KM. Effects of a cognitive-behavioural internet program on depression, vulnerability to depression and stigma in adolescent males: a school-based controlled trial. Cogn Behav Ther. 2006;35(1):43–54. doi: 10.1080/16506070500303456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Kearney R, Kang K, Christensen H, Griffiths K. A controlled trial of a school-based Internet program for reducing depressive symptoms in adolescent girls. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(1):65–72. doi: 10.1002/da.20507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Voorhees BW, Vanderplough-Booth K, Fogel J, et al. Integrative internet-based depression prevention for adolescents: a randomized clinical trial in primary care for vulnerability and protective factors. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008 Nov;17(4):184–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vliet HV, Andrews G. Internet-based course for the management of stress for junior high schools. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009 Apr;43(4):305–309. doi: 10.1080/00048670902721145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.March S, Spence SH, Donovan CL. The efficacy of an internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention for child anxiety disorders. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009 Jun;34(5):474–487. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spence SH, Holmes JM, March S, Lipp OV. The feasibility and outcome of clinic plus internet delivery of cognitive-behavior therapy for childhood anxiety. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006 Jun;74(3):614–621. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bruning Brown J, Winzelberg AJ, Abascal LB, Taylor CB. An evaluation of an Internet-delivered eating disorder prevention program for adolescents and their parents. J Adolesc Health. 2004 Oct;35(4):290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heinicke BE, Paxton SJ, McLean SA, Wertheim EH. Internet-delivered targeted group intervention for body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2007 Jun;35(3):379–391. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Newton NC, Andrews G, Teesson M, Vogl LE. Delivering prevention for alcohol and cannabis using the Internet: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Prev Med. 2009 Jun;48(6):579–584. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Newton NC, Teesson M, Vogl LE, Andrews G. Internet-based prevention for alcohol and cannabis use: final results of the Climate Schools course. Addiction. 2010 Apr;105(4):749–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coyle D, Doherty G, Sharry J. An evaluation of a solution focused computer game in adolescent interventions. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009 Jul;14(3):345–360. doi: 10.1177/1359104508100884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fukkink RG, Hermanns JM. Children's experiences with chat support and telephone support. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009 Jun;50(6):759–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Michaud PA, Colom P. Implementation and evaluation of an internet health site for adolescents in Switzerland. J Adolesc Health. 2003 Oct;33(4):287–290. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nicholas J. The role of internet technology and social branding in improving the mental health and wellbeing of young people. Perspect Public Health. 2010 Mar;130(2):86–90. doi: 10.1177/1757913908101797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Santor DA, Poulin C, LeBlanc JC, Kusumakar V. Online health promotion, early identification of difficulties, and help seeking in young people. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007 Jan;46(1):50–59. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242247.45915.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Crutzen R, de Nooijer J, Brouwer W, Oenema A, Brug J, de Vries NK. Internet-delivered interventions aimed at adolescents: a Delphi study on dissemination and exposure. Health Educ Res. 2008 Jun;23(3):427–439. doi: 10.1093/her/cym094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cuijpers P, Donker T, van Straten A, Li J, Andersson G. Is guided self-help as effective as face-to-face psychotherapy for depression and anxiety disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Psychol Med. 2010 Apr 21;:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garber J. Depression in children and adolescents: linking risk research and prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2006 Dec;31(6 Suppl 1):S104–S125. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Compas BE, Hinden BR, Gerhardt CA. Adolescent development: pathways and processes of risk and resilience. Annu Rev Psychol. 1995;46:265–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.46.020195.001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beardslee WR, Gladstone TRG. Prevention of childhood depression: Recent findings and future prospects. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49(12):1101–1110. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Beardslee WR, Gladstone TR, Wright EJ, Cooper AB. A family-based approach to the prevention of depressive symptoms in children at risk: evidence of parental and child change. Pediatrics. 2003;112(2):e119–e131. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.e119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Griffiths KM, Calear AL, Banfield M, Tam A. Systematic review on Internet Support Groups (ISGs) and depression (2): What is known about depression ISGs? J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(3):e41. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Griffiths KM, Calear AL, Banfield M. Systematic review on Internet Support Groups (ISGs) and depression (1): Do ISGs reduce depressive symptoms? J Med Internet Res. 2009;11(3):e40. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hsiung R. The best of both worlds: an online self-help group hosted by a mental health professional. Cyberpsychol Behav. 3:935–950. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Spence SH. Online CBT in the treatment of child and adolescent anxiety disorders: issues in the development of BRAVE-ONLINE and two case illustrations. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2008;36:411–430. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reger MA, Gahm GA. A meta-analysis of the effects of internet- and computer-based cognitive-behavioral treatments for anxiety. J Clin Psychol. 2009 Jan;65(1):53–75. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Winzelberg AJ, Taylor CB, Sharpe T, Eldredge KL, Dev P, Constantinou PS. Evaluation of a computer-mediated eating disorder intervention program. Int J Eat Disord. 1998 Dec;24(4):339–349. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199812)24:4<339::aid-eat1>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Merry S, McDowell H, Hetrick S, Bir J, Muller N. Psychological and/or educational interventions for the prevention of depression in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1):CD003380. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003380.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pratt BM, Woolfenden SR. Interventions for preventing eating disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD002891. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Munoz-Solomando A, Kendall T, Whittington CJ. Cognitive behavioural therapy for children and adolescents. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008 Jul;21(4):332–337. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328305097c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]