Abstract

Pyrophosphate is a potent inhibitor of medial vascular calcification where its level is controlled by hydrolysis via a tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP). We sought to determine if increased TNAP activity could explain the pyrophosphate deficiency and vascular calcification seen in renal failure. TNAP activity increased twofold in intact aortas and in aortic homogenates from rats made uremic by feeding adenine or by 5/6 nephrectomy. Immunoblotting showed an increase in protein abundance but there was no increase in TNAP mRNA assessed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Hydrolysis of pyrophosphate by rat aortic rings was inhibited about half by the nonspecific alkaline phosphatase inhibitor levamisole and was reduced about half in aortas from mice lacking TNAP. Hydrolysis was increased in aortic rings from uremic rats and all of this increase was inhibited by levamisole. An increase in TNAP activity and pyrophosphate hydrolysis also occurred when aortic rings from normal rats were incubated with uremic rat plasma. These results suggest that a circulating factor causes pyrophosphate deficiency by regulating TNAP activity and that vascular calcification in renal failure may result from the action of this factor. If proven by future studies, this mechanism will identify alkaline phosphatase as a potential therapeutic target.

Keywords: vascular calcification

Vascular disease is common in renal failure and is responsible for much of the morbidity and mortality in end-stage renal disease. One component of this that is receiving increased attention is calcification of the arterial media, which is distinct from the intimal calcification associated with atherosclerosis. The extent and natural history of medial calcification in end-stage renal disease is unknown because atherosclerotic calcification is often present in these patients as well and recent studies using electron-beam computed tomography to quantitate coronary artery calcification have not distinguished between these forms. However, these studies do indicate that virtually all hemodialysis patients eventually develop coronary artery calcification.1 A survey almost 30 years ago, based on soft-tissue X-rays that probably detect only medial calcification, found that 40% of patients with chronic renal failure had calcification whether or not they were undergoing dialysis.2 The true incidence was probably higher due to the insensitivity of plain X-rays.

Clinical practice to prevent medial vascular calcification in end-stage renal disease is based on the flawed assumption that it is merely a manifestation of plasma concentrations of Ca2+ and that are above the solubility product for Ca3(PO4)23. This clearly cannot be the entire explanation since medial calcification is commonly seen in diabetes and in aging, and in several genetic defects in the presence of normal plasma calcium and phosphate concentrations.4–7 These observations suggest that calcification can occur at normal concentrations of calcium and phosphate and that mechanisms are normally in place to inhibit this. Thus, vascular calcification must result from a failure of these inhibitory mechanisms in addition to the disturbances in mineral metabolism.

Pyrophosphate is a well-established inhibitor of calcification in cartilage, of calcium oxalate crystallization in the kidney,8,9 and of vascular calcification in vitamin D-toxic rats.10 It is a direct and potent inhibitor of hydroxyapatite formation in vitro, and even small concentrations in plasma (2–4 μm) are sufficient to completely prevent crystallization from saturated solutions of calcium and phosphate.8,9,11 We have shown that pyrophosphate (PPi) is released by aortas in culture and that calcification of these aortas in the presence of high phosphate and calcium concentrations only occurs when the PPi is removed.12 Consistent with this, humans with low levels of PPi due to the absence of the PPi-producing enzyme PC1 develop severe, fatal arterial calcification.5,13

Tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) is a key determinant of tissue PPi levels and calcification.14 This ectoenzyme hydrolyzes PPi and its absence in humans (hypophosphatasia) increases plasma PPi concentrations15 and results in defective bone mineralization. This phenotype is recreated in mice lacking TNAP16 and is corrected by reducing PPi levels.17 Whether TNAP has a similar role in vascular smooth muscle calcification is not known. We recently showed that plasma PPi levels are reduced in hemodialysis patients,18 suggesting that PPi deficiency might contribute to uremic vascular calcification. To determine whether there is an increase in TNAP that could explain PPi deficiency and calcification in smooth muscle in renal failure, we assayed alkaline phosphatase and the hydrolysis of PPi in aortas from uremic rats and in normal aortas cultured under uremic conditions.

RESULTS

The concentrations of urea, calcium, and phosphate in the adenine-fed rats and control pair-fed rats are shown in Table 1. The adenine-fed rats had ninefold higher urea levels and 2.5-fold higher phosphate levels, and slightly higher calcium levels. Alkaline phosphatase activity was 92% greater in aortic extracts from adenine-fed rats than in that from control rats (Figure 1). A similar increase (126%) was observed in the remnant kidney model of uremia. The serum urea concentration in these rats was 113±22 mg per 100 ml, a little more than half the level in the adenine-fed rats. The increase in alkaline phosphatase activity was even greater (142%) when intact aortas (adenine-fed rats) were assayed. To determine the mechanism by which renal failure increases AP activity, protein and mRNA levels were examined. Immunoblots of aortic extracts (Figure 2) revealed a prominent band at approximately 75 kD that was absent in bone from Akp2−/− mice but not wild-type mice, confirming its identity as TNAP. Densitometry revealed a 126% increase in signal from 52.5±9.2 U in six control aortas to 119±9.1 U in seven uremic aortas (P<0.001). Removal of endothelium by swabbing the luminal surface did not reduce AP activity (not shown), and adventitia was removed prior to assay, indicating that vascular smooth muscle was responsible for the AP activity measured in the aortas.

Table 1.

Plasma chemistries in control and adenine-fed rats

| Urea N (mg per 100 ml) |

Phosphate (mg per 100 ml) |

Calcium (mg per 100 ml) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 22±1.9 | 4.0±0.5 | 8.2±0.2 |

| Adenine-fed | 202±6* | 10.3±1.0* | 9.16±0.2** |

P<0.001;

P<0.01.

Figure 1. Alkaline phosphatase activity in aortas from uremic (filled bars) and control pair-fed rats (open bars).

(a) Hydrolysis of p-nitrophenylphosphate in homogenates of aortas from adenine-fed rats, expressed as mg of protein. (b) Hydrolysis of p-nitrophenylphosphate in homogenates of aortas from nephrectomized rats, expressed as mg protein. (c) Hydrolysis of p-nitrophenylphosphate by intact, freshly isolated aortas from adenine-fed rats, expressed as mg dry weight. Results are the means+s.e. of the number of animals indicated in parentheses. *P<0.0001; **P<0.002 vs control.

Figure 2. Immunoblot of extracts from control and uremic aortas using a polyclonal antibody against TNAP.

Also shown are bone extracts from wild-type (TNAP+/+) mice and mice lacking TNAP. Each sample was 50 μg of protein.

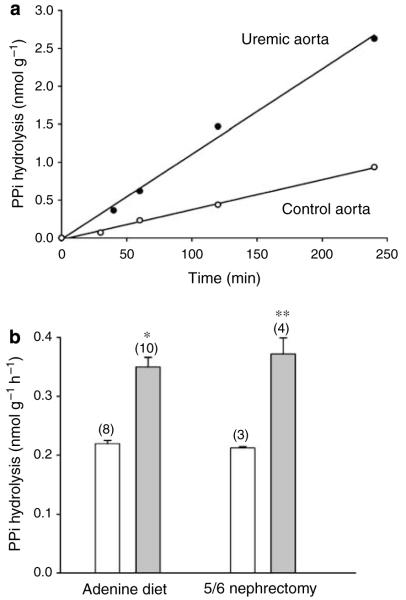

To confirm that the increase in alkaline phosphatase activity resulted in increased hydrolysis of PPi, aortas were incubated with 32PPi in culture medium. Hydrolysis of PPi was linear for at least 4 h in both control and uremic aortas (Figure 3a) and there was no hydrolysis of PPi in culture medium without aortas (not shown). As shown in Figure 3b, hydrolysis was 59% greater in aortas from the adenine-fed rats and, again, a similar increase (76%) was seen in aortas from uremic, remnant kidney rats. Assays were repeated with levamisole, an inhibitor of alkaline phosphatase, to determine whether the increase in PPi hydrolysis was due to the increased TNAP activity (Figure 4). Levamisole produced a dose-dependent inhibition of alkaline phosphatase with 80% inhibition at 1 mm (Figure 4a). The residual activity most likely represents incomplete inhibition of TNAP. This concentration of levamisole reduced PPi hydrolysis by 41±9% in aortas from control pair-fed rats (Figure 4b). The increased hydrolysis in uremic aortas was completely inhibited by levamisole, with no increase in levamisole-resistant hydrolysis, indicating that TNAP was responsible for the increased hydrolysis of PPi. Hydrolysis of PPi by smooth muscle TNAP was confirmed in Akp2−/− mice, which lack TNAP.16,19 Like patients with hypophophatasia, these mice are characterized by hypophosphatasemia due to global deficiency of TNAP activity, endogenous accumulation of the AP substrates inorganic PPi and pyridoxal-5′-phosphate, and impaired skeletal matrix mineralization leading to rickets or osteomalacia. Unfortunately, these mice do not live for more than 2 weeks after birth, making the assay technically difficult and prohibiting uremia from being studied. Because of the limited amount of tissue available, the assay was extended to 66 h and the results were normalized to length of aorta rather than weight. As shown in Figure 5, hydrolysis of PPi was linear over this time and was substantially reduced in each of the homozygous mouse aortas. The hydrolysis rate in aortas from homozygous mice (0.068±0.005 pmol h−1 mm−1) was 44% the rate in wild-type mice (0.156±0.007 pmol h−1 mm−1). The rate in heterozygote aortas (0.136±0.004 pmol h−1 mm−1) was slightly but not significantly lower than that in wild-type aortas.

Figure 3. Hydrolysis of PPi by rat aorta.

(a) Time course showing representative results from a single uremic rat (5/6 nephrectomy) and a control rat. (b) Hydrolysis rate in aortas from uremic (filled bars) and control pair-fed rats (open bars). Results are the means+s.e. of the number of animals indicated in parentheses. *P<0.0001; **P<0.005 vs control.

Figure 4. Effect of levamisole on alkaline phosphatase and PPi hydrolysis in intact rat aorta.

(a) Alkaline phosphatase activity in aortic rings from normal rats at different concentrations of levamisole, expressed per mg dry weight. (b) Hydrolysis of PPi by aortas from uremic and control pair-fed rats in the absence (black bars) and presence (gray bars) of 1 mm levamisole. Results are the means+s.e. of seven control and five uremic aortas.

Figure 5. Hydrolysis of PPi in aortas from mice lacking tissue-nonselective alkaline phosphatase (Akp2−/− mice; solid circles) from heterozygote mice (open circles), and wild-type mice (triangles).

Each line represents a single aorta.

Quantitative PCR was performed to determine whether the upregulation of TNAP was transcriptional and whether it was related to osteogenic transformation in the smooth muscle. As shown in Table 2, the quantity of TNAP mRNA was the same in aortas from uremic (adenine-fed) and control rats. There was also no difference in the abundance of mRNA for cbfa-1, a transcription factor for osteogenesis, and bone gla protein, a bone-specific protein. The amount of cbfa-1 mRNA was very low and mRNA for bone gla protein was essentially undetectable. In contrast, ROS 17/2.8 osteosarcoma cells contained over 100-fold more mRNA for cbfa-1 and bone gla protein. An increase in mRNA was detected for osteopontin, which is also upregulated in uremic vessels (K Lomashvili and WC O’Neill, unpublished data), demonstrating the ability of quantitative PCR to detect increased gene transcription in uremic aorta. The possibility that a circulating factor or factors is responsible for the upregulation of alkaline phosphatase was investigated by examining the effect of uremic plasma on normal aortas maintained in culture (Figure 6). We have previously demonstrated the viability of these aortas for up to 2 weeks in serum-free medium.12 Under these conditions, all the AP activity remains in the vessels with none detected in the medium. Culture for 9 days in medium containing 10% uremic, heat-inactivated rat plasma increased AP activity in aortic extracts by 141% and increased PPi hydrolysis in intact aortas by 57% compared to culture with control plasma (P<0.001 for both).

Table 2.

Quantitation of mRNA in rat aorta and ROS cells

| Copies per 106 18S RNA |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | Control aorta | Uremic aorta | ROS cells | Fold increase in uremia | P-value |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 42±4 | 49±12 | 369 | 1.2 | NS |

| cbfa-1 | 11±4 | 16±6 | 5900 | 1.5 | NS |

| Bone gla protein | <0.01 | <0.01 | 128 | 1.4 | NS |

| Osteopontin | 420±90 | 2030±580 | 109 | 4.8 | <0.05 |

NS, nonsignificant; ROS, rat osteosarcoma.

Control and uremic samples were run simultaneously for each comparison and the values are means±s.e.m. of five separate aortas. Data for the ROS cells are from a single assay.

Figure 6. Effect of uremic plasma on cultured rat aortas.

Aortic rings were cultured for 9 days in 10% plasma from control (open bars) or uremic (filled bars) rats. (a) Alkaline phosphatase activity in homogenates expressed per mg protein. (b) Hydrolysis of PPi expressed per dry weight. Results are the means+s.e. of the number of animals indicated in parentheses. *P<0.0001; **P<0.005 vs control.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that renal failure increases the expression in vascular smooth muscle of TNAP, a key enzyme in the mineralization of bone and cartilage. The role of TNAP in calcification was originally thought to be the provision of inorganic phosphate from organic phosphates but recent data have demonstrated that it functions instead to hydrolyze and reduce the levels of extracellular pyrophosphate, an endogenous inhibitor of hydroxyapatite formation. Both mice and humans lacking TNAP have increased PPi levels and mineralization defects,16 and in mice, these can be corrected by crossing them with mice deficient in extracellular PPi production due to the absence of ectonucleotide pyrophosphorylase or the putative PPi transporter Ank.17 Furthermore, overexpression of TNAP can induce ectopic calcification.14 Since PPi is also an important inhibitor of vascular calcification, it is likely that TNAP plays a key role in mineralization of vascular smooth muscle as well.

The increased hydrolysis of PPi resulting from upregulation of TNAP in uremic rat aorta would be expected to promote vascular calcification by lowering PPi levels. Although it is not possible to measure extracellular PPi levels in aorta, we have demonstrated decreased plasma levels in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis,18 which likely reflect a deficiency at the tissue level. It is important to distinguish vascular TNAP from circulating TNAP. The former is entirely tissue-bound, consistent with the localization of this ectoenzyme on the extracellular surface,20 while the latter likely derives from apoptosis of osteoblasts20 and is an indication of bone turnover. Although the circulating form is also enzymatically active, it is unlikely to achieve the local effect of the membrane-bound enzyme in the vessel wall. There is no correlation between circulating levels of TNAP and PPi.18 Thus, it is unlikely that circulating TNAP explains the apparent connection between bone turnover and vascular calcification.

Levamisole, an inhibitor of TNAP, reduced PPi hydrolysis in rat aorta, consistent with the ability of TNAP to hydrolyze PPi in vitro.21 Despite the fact that 1 mm levamisole inhibited TNAP activity (p-nitrophenyl phosphate hydrolysis) by 79%, PPi hydrolysis was reduced by only 41%, indicating that TNAP accounts for about half of the PPi hydrolysis in rat aorta. This was confirmed by showing that PPi hydrolysis was reduced only 56% in aortas from mice lacking TNAP compared to aortas from wild-type mice. The identity of the enzyme responsible for TNAP-independent hydrolysis is not known but, since all of the increase in PPi hydrolysis in uremic aortas was inhibited by levamisole, the other enzyme(s) is not upregulated in uremia.

Because TNAP is an ectoenzyme, its regulation is principally through changes in protein expression and, consistent with this, the increase in TNAP activity (92%) and protein (126%) in uremic aortas were similar. However, this increase in TNAP protein did not appear to be transcriptionally mediated since the quantity of TNAP mRNA did not increase in uremic aortas. Because of the insensitivity of quantitative PCR to small changes in mRNA, a small increase in mRNA resulting in a doubling of TNAP protein cannot be ruled out. A similar mRNA-independent upregulation of TNAP occurs in L cells in response to elevations in cyclic AMP,22 indicating that TNAP can be regulated through changes in protein degradation or translation efficiency. The fact that the increase was also observed in the remnant model of renal failure indicates that it was related to uremia and not due to some other effect of adenine. The increase observed in aortas cultured with uremic plasma indicates that a circulating factor is involved. Candidates include hyperphosphatemia and elevated levels of parathyroid hormone, which we have previously shown to upregulate AP activity in normal aortas in culture.23 Although hyperphosphatemia could contribute to the upregulation of AP in vivo, the 10-fold dilution of plasma in culture would result in an insignificant increase in the in vitro studies. The plasma dilution would have also minimized any effect of PTH but this cannot be ruled out.

Tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase is an important component of osteoblastic differentiation, and transformation of vascular smooth muscle cells into osteoblastic cells has been proposed as a mechanism for medial calcification.24 However, there was no evidence of osteogenesis, as indicated by lack of induction of cbfa-1 or bone Gla protein, in aortas from uremic, adenine-fed rats. These results indicate that the increase in AP activity in uremic vessels is not due to osteoblastic transformation and that, in this model, uremia does not produce osteoblastic transformation in vascular smooth muscle.

The results of this study suggest that preventing upregulation of TNAP or inhibiting its hydrolysis of PPi could reduce uremic vascular calcification. Unfortunately, tools to answer this hypothesis do not currently exist. The Akp2 mice that lack TNAP should be protected from uremic vascular calcification but survive for only 2 weeks after birth, preventing uremia from being tested. Levamisole is a weak inhibitor of TNAP and has other effects in vivo,25 and the levels necessary to inhibit TNAP are not achievable in vivo. The development of more potent and specific inhibitors26 may enable TNAP to be a therapeutic target in the future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Uremic rats

Chronic renal failure was produced by feeding adenine to rats.27,28 This results in crystallization of 2,8-dihydroxyadenine in the tubules and interstitium with resulting renal fibrosis and atrophy and all the metabolic abnormalities of chronic renal failure.27 Rats were fed standard rat chow (0.95% calcium and 0.4% phosphorus)+0.75% adenine for 4 weeks, after which blood was collected and aortas were harvested. Aortic calcification does not occur with this diet. Control rats were fed a restricted diet of normal rat chow so that their weight loss matched with that of the adenine-fed rats. Except where indicated, all studies were performed on aortas from adenine-fed rats. In some studies, renal failure was produced by unilateral nephrectomy followed by partial infarction of the remnant kidney and a high-protein diet as previously described.29

Aortic culture

Aortic culture was performed as previously described.12 Briefly, aortas were removed under sterile conditions from male Sprague—Dawley rats weighing 150–250 g and adventitia was carefully removed. Adventitia was not completely removed as this led to smooth muscle injury. The vessels were cut into 3–4 mm rings and placed in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Mediatech, Herndon, VA, USA) without serum at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator with medium changes every 3 days. The concentrations of calcium and phosphate in this medium are 1.8 and 0.9 mm respectively.

Alkaline phosphatase activity

Alkaline phosphatase was measured colorimetrically as the hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl phosphate at pH 10.5 according to instructions from the supplier (Sigma Diagnostics, St Louis, MO, USA). Aortas were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (10 mm Tris, pH 7.4; 2.5 mm EDTA; 50 mm NaF; 1 mm Na4P2O7.10H2O; 1% Triton X-100; 10% glycerol; 1% deoxycholate, 1 μgml−1 aprotinin, 0.18 mg ml−1 phenylmethanesulphonylfluoride, 0.18 mg ml−1 orthovanadate, 1% Triton X-100 in 0.9% saline) on ice and centrifuged in a microfuge at the maximum speed for 5 min. Supernatant was removed for assay. Assays in intact aortas were performed in Hanks buffered salt solution (pH 7.4) containing 1 mm Ca and 4 mg ml−1 p-nitrophenyl phosphate.

Alkaline phosphatase protein and mRNA

Immunoblots were performed on aortic extracts prepared as above and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Following transfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, the blots were developed using a polyclonal antibody developed against rat liver alkaline phosphatase30 and kindly provided by Dr Y Ikehara. Total RNA was isolated from rat aortas using a phenol extraction method (ToTALLY RNA total RNA Isolation kit; Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Integrity of RNA was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis. cDNA was synthesized from RNA by reverse transcriptase primed with oligo(dT)20 using Thermoscript RT-PCR (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). For 18S RNA, the specific primer GAGCTGGAATTACCGCGGCT was used for reverse transcription.31 Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed on cDNA samples with an iCycler iQ Real Time PCR detection system using iQ SYBR GREEN SUPERMIX (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA). Primers for TNAP were TGGACGGTGAACGG GAGAAC (forward) and TGAAGCAGGTGAGCCATAGG (reverse). These primers span one intron and include neighboring exons. Primers for 18S RNA were GGGAGGTAGTGACGAAAAATAACAAT (forward) and TTGCCCTCCAATGGATCCT (reverse) as previously described.31 Melting curves revealed only single peaks. Serial dilutions of TNAP and 18S cDNA were used to construct standard curves for quantitative polymerase chain reaction and to calculate amplification efficiencies. Nearly full-length cDNA for TNAP was cloned from rat osteosarcoma cell cDNA using pCRII-TOPO (Invitrogen). ROS 17/2.8 cells were kindly provided by Dr Mark Nanes.

Pyrophosphate hydrolysis

Aortic rings were preincubated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium for 1 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator, after which the medium was changed to Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 1 μm sodium pyrophosphate and [32P]PPi (μCi ml−1). Levamisole was added from a stock solution of 100 mm in 25% dimethylsulfoxide to a final concentration of 1 mm. Samples of medium (20 μl) were mixed with 800 μl of ammonium molybdate (to bind orthophosphate) in 0.75 m sulfuric acid. The samples were then extracted with 1.6 ml of isobutanol/petroleum ether (4:1) to separate phosphomolybdate from PPi, and 400 μl of the top (organic) phase containing phosphomolybdate was removed for counting of radioactivity. The rings were then dried and weighed.

Mice lacking tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase

The generation and characterization of Akp2−/− mice, deficient in TNAP, has been reported previously.16,19 Akp2−/− mice (C57BL/6 and 129J hybrid background) were maintained by heterozygote breeding. All animals (breeders, nursing moms, pups) had free access to a modified laboratory rodent diet 5001 with 325 p.p.m. pyridoxine (No. 48057, TestDiet), since supplementation with vitamin B6 extends the life of the Akp2−/− pups for a few days. Akp2−/− pups were killed at day 16 for isolation of the aortas.

Statistics

Data are presented as means±s.e.m. Significance was tested by two-tailed Student’s t-test. For multiple comparisons, the P-value was multiplied by the number of comparisons. For skewed data, a logarithmic transformation was applied prior to statistical analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported by grants DK69681 (WCO), DE12889 (JLM), AR47908 (JLM), from the National Institutes of Health and a grant from the Genzyme Renal Innovations Program (WCO). Dr Garg was supported by NIH Training Grant DK07656 and Dr Lomashvili was supported by an Amgen Nephrology Fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goodman WG, Goldin J, Kuizon BD, et al. Coronary-artery calcification in young adults with end-stage renal disease who are undergoing dialysis. New Eng J Med. 2000;342:1478–1483. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Memma HE, Oreopoulos DG, deVeber GA. Arterial calcifications in severe chronic renal disease and their relationship to dialysis treatment, renal transplant, and parathyroidectomy. Radiology. 1976;121:315–321. doi: 10.1148/121.2.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Neill WC. The fallacy of the calcium phosphorus product. Kidney Int. 2007;72:792–796. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Everhart JE, Pettitt DJ, Knowler WC, et al. Medial arterial calcification and its association with mortality and complications of diabetes. Diabetologia. 1988;31:16–23. doi: 10.1007/BF00279127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutsch F, Vaingankar S, Johnson K, et al. PC-1 nucleotide triphosphate pyrophosphohydrolase deficiency in idiopathic infantile arterial calcification. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:543–554. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63996-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bucay N, Sarosi I, Dunstan C, et al. Osteoprotegerin-deficient mice develop early onset osteoporosis and arterial calcification. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1260–1268. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo G, Ducy P, McKee MD, et al. Spontaneous calcification of arteries and cartilage in mice lacking matrix Gla protein. Nature. 1997;386:78–81. doi: 10.1038/386078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russell RGG, Bisaz S, Fleisch H. Pyrophosphate and diphosphates in calcium metabolism and their possible role in renal failure. Arch Intern Med. 1969;124:571–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer JL. Can biological calcification occur in the presence of pyrophosphate? Arch Biochem Biophys. 1984;231:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(84)90356-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schibler D, Russell GG, Fleisch H. Inhibition by pyrophosphate and polyphosphate of aortic calcification induced by vitamin D3 in rats. Clin Sci. 1968;35:363–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francis MD, Russell RGG, Fleisch H. Diphosphonates inhibit formation of calcium phosphate crystals in vitro and pathologic calcification in vivo. Science. 1969;165:1264–1266. doi: 10.1126/science.165.3899.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lomashvili KA, Cobbs S, Hennigar RA, et al. Phosphate-induced vascular calcification: role of pyrophosphate and osteopontin. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1392–1401. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000128955.83129.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terkeltaub RA. Inorganic pyrophosphate generation and disposition in pathology. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1–C11. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murshed M, Harmey D, Millan JL, et al. Unique coexpression in osteoblasts of broadly expressed genes accounts for the spatial restriction of ECM mineralization to bone. Genes Dev. 2006;19:1093–1104. doi: 10.1101/gad.1276205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell RGG, Bisaz S, Donath A, et al. Inorganic pyrophosphate in plasma in normal persons and in patients with hypophosphatasia, osteogenesis imperfecta, and other disorders of bone. J Clin Invest. 1971;50:961–969. doi: 10.1172/JCI106589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fedde KN, Blair L, Silverstein J, et al. Alkaline phosphatase knock_out mice recapitulate the metabolic and skeletal defects of infantile hypophosphatasia. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:2015–2026. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.12.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harmey D, Hessle L, Narisawa S, et al. Concerted regulation of inorganic pyrophosphate and osteopontin by Akp2, Enpp1 and Ank: an integrated model of the pathogenesis of mineralization disorders. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1199–1209. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63208-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lomashvili KA, Khawandi W, O’Neill WC. Reduced plasma pyrophosphate levels in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2495–2500. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004080694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Narisawa S, Frohlander N, Millan JL. Inactivation of two mouse alkaline phosphatase genes and establishment of a model of infantile hypophosphatasia. Dev Dyn. 1997;208:432–446. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199703)208:3<432::AID-AJA13>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Millan JL. Mammalian Alkaline Phosphatases. From Biology to Applications in Medicine and Biotechnology. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.; Weinheim, Germany: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moss DW, Eaton RH, Smith JK, et al. Association of inorganic pyrophosphatase activity with human alkaline phosphatase preparations. Biochem J. 1967;102:53–57. doi: 10.1042/bj1020053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uhler MD, Abou-Chebl A. Cellular concentrations of protein kinase A modulate prostaglandin and cAMP induction of alkaline phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:8658–8665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lomashvili K, Garg P, O’Neill WC. Chemical and hormonal determinants of vascular calcification in vitro. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1464–1470. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moe SM, O’Neill KD, Duan D, et al. Medial artery calcification in ESRD patients is associated with deposition of bone matrix proteins. Kidney Int. 2002;61:638–647. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renoux G. The general immunopharmacology of levamisole. Drugs. 1980;19:89–99. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198020020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narisawa S, Harmey D, Yadav MC, et al. Novel inhibitors of alkaline phosphatase suppress vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1700–1710. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yokozawa T, Zheng PD, Oura H, et al. Animal model of adenine-induced chronic renal failure in rats. Nephron. 1986;44:230–234. doi: 10.1159/000183992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okada H, Kaneko Y, Yawata T, et al. Reversibility of adenine-induced renal failure in rats. Clin Exp Nephrol. 1999;3:82–88. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bailey JL, Wang X, England BE, et al. The acidosis of chronic renal failure activates muscle proteolysis in rats by augmenting transcription of genes encoding proteins of the ATP-dependent Ubiquitin–Proteasome pathway. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1447–1453. doi: 10.1172/JCI118566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoshi K, Amizuka N, Oda K, et al. Immunolocalization of tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase in mice. Histochem Cell Biol. 1997;107:183–191. doi: 10.1007/s004180050103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu L, Altmann SW. mRNA and 18S-RNA coapplication-reverse transcription for quantitative gene expression analysis. Anal Biochem. 2005;345:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]