Abstract

Background

Increased focus on the number and type of physicians delivering health care in the United States necessitates a better understanding of changes in graduate medical education (GME). Data collected by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) allow longitudinal tracking of residents, revealing the number and type of residents who continue GME following completion of an initial residency. We examined trends in the percent of graduates pursuing additional clinical education following graduation from ACGME-accredited pipeline specialty programs (specialties leading to initial board certification).

Methods

Using data collected annually by the ACGME, we tracked residents graduating from ACGME-accredited pipeline specialty programs between academic year (AY) 2002–2003 and AY 2006–2007 and those pursuing additional ACGME-accredited training within 2 years. We examined changes in the number of graduates and the percent of graduates continuing GME by specialty, by type of medical school, and overall.

Results

The number of pipeline specialty graduates increased by 1171 (5.3%) between AY 2002–2003 and AY 2006–2007. During the same period, the number of graduates pursuing additional GME increased by 1059 (16.7%). The overall rate of continuing GME increased each year, from 28.5% (6331/22229) in AY 2002–2003 to 31.6% (7390/23400) in AY 2006–2007. Rates differed by specialty and for US medical school graduates (26.4% [3896/14752] in AY 2002–2003 to 31.6% [4718/14941] in AY 2006–2007) versus international medical graduates (35.2% [2118/6023] to 33.8% [2246/6647]).

Conclusion

The number of graduates and the rate of continuing GME increased from AY 2002–2003 to AY 2006–2007. Our findings show a recent increase in the rate of continued training for US medical school graduates compared to international medical graduates. Our results differ from previously reported rates of subspecialization in the literature. Tracking individual residents through residency and fellowship programs provides a better understanding of residents' pathways to practice.

Background

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) is a private nonprofit organization responsible for accrediting allopathic graduate medical education (GME) programs in the United States. Since 2000, the ACGME has required programs to annually update information about each resident on duty as part of the accreditation process. While a small number of residency and fellowship programs are accredited by other organizations (or are unaccredited), the majority of allopathic residents are trained in ACGME-accredited programs. The ACGME database of residents is arguably the most comprehensive in the United States, as the complete and accurate reporting of residents is an accreditation requirement.

The number and specialty mix of physicians entering practice is of great importance in health care delivery. In the past 10 years, there has been a great deal of interest in patterns of growth in GME, both in terms of the number and type of programs and of the number of physicians completing training and entering subspecialty training.1,2 This growth has implications for estimates of the number of physicians available to enter practice.2–4 Prior studies1–8 have examined trends in subspecialization using cross-sectional data comparison or individual physician surveys. In this report, we use annual ACGME data to track individual residents through graduation and across ACGME-accredited residency and fellowship programs to assess patterns of continuing GME.

Methods

The ACGME maintains a cumulative database (the Accreditation Data System) of all residents in every accredited GME program, used for accreditation purposes. Each academic year (AY, July 1 to June 30), programs are required to update information for all their residents and enter newly appointed residents into this database. Programs must provide information regarding demographics, medical school (name, type, and degree date), and status in the program (active full-time or part-time, completed training, transferred, etc) for each resident. A unique identifier code is assigned to each resident using a complex algorithm which includes information unchanged over time (date of birth, medical school of graduation, graduation date, encrypted Social Security number, and sex). Ongoing quality assurance measures ensure that the information provided by programs is accurate and up-to-date. Programs failing to provide required information may ultimately place their accreditation status in jeopardy.

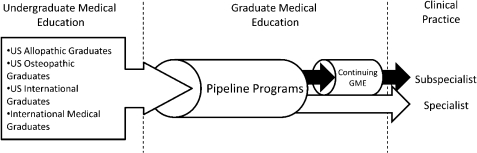

We restricted our analyses to those specialties leading to initial board certification, which we refer to as pipeline specialties (box). At the time of graduation from these specialties, residents may either choose to enter clinical practice or choose to enter additional specialty or subspecialty training. Regardless of the pathway to practice, the net output of physicians over time from residency education into clinical practice is determined by the number of graduates of pipeline specialties (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram of the Graduate Medical Education (GME) Pipeline. Pipeline Programs Are Programs Leading to Initial Board Certification. Continuing GME Programs Are Programs Undertaken by Residents After Successful Completion of Pipeline Programs. In Many Disciplines, These Are Also Called Fellowship Programs, Although Residents May Also Choose to Pursue a Second Specialty Program Prior to Entering Clinical Practice

box List of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–Accredited Pipeline Specialties that Lead to Initial Board Certification as of Academic Year 2009–2010

Anesthesiology

Dermatology

Emergency medicine

Family medicine

Internal medicine

Internal medicine–pediatrics combined

Medical genetics

Neurological surgery

Neurology

Nuclear medicine

Obstetrics and gynecology

Ophthalmology

Orthopedic surgery

Otolaryngology

Pathology

Pediatrics

Physical medicine and rehabilitation

Plastic surgery

Plastic surgery, integrated

Preventive medicine

Psychiatry

Radiology, diagnostic

Radiation oncology

Surgery

Thoracic surgery, integrated

Urology

Vascular surgery, integrated

We examined trends in the number of graduates and the number of graduates continuing GME for the pipeline specialties. Graduates of the pipeline specialties were identified as those residents given a status of “completed all training and promoted to practice” and grouped by AY of graduation. These graduates were then tracked using the unique ACGME-assigned resident code to determine the rate of continuing GME, defined as entering a subsequent residency or fellowship program within 2 years. We included residents who graduated in AY 2002–2003 through AY 2006–2007 because these years compose the most recent 5-year period that would allow us to track residents for 2 years beyond graduation. Residents in combined internal medicine–pediatrics, integrated plastic surgery, integrated vascular surgery, and integrated thoracic surgery programs were not included in this analysis since these programs were not accredited by the ACGME until after AY 2005–2006.

We analyzed data and trends by medical school type, comparing the rates of US allopathic medical school graduates (USMGs) and international medical graduates (IMGs) pursuing additional GME training during this 5-year period. In reporting the patterns of change by specialty, we focused our comparisons of USMGs and IMGs to the subset of pipeline specialties that represent the majority of graduates continuing training: specialties having at least 400 graduates each year, of which at least 10% are IMGs, and at least a 5% rate of continuing GME. Due to small sample sizes, we do not separately report the percentages of continuing education for graduates for whom medical school was unknown, Canadian medical graduates, and osteopathic graduates (doctors of osteopathy, or DOs).

Results

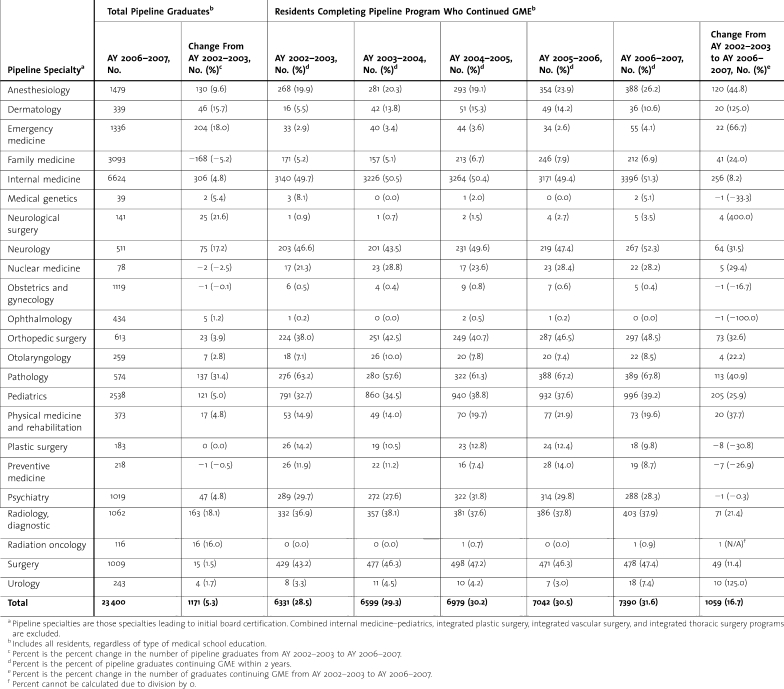

table 1 shows the changes in the number of pipeline specialty graduates, the number and percent of graduates continuing GME for each year, and the change in the absolute number of graduates continuing GME, for the period from AY 2002–2003 to AY 2006–2007. The total increase in the number of graduates since AY 2002–2003 was proportionally small (1171, or 5.3%), while the number of graduates entering additional training over the same time period showed a much larger proportional increase (1059, or 16.7%). The percentage of graduates continuing their training increased, overall and within most pipeline specialties, across the 5-year period. Among pipeline specialty graduates in AY 2002–2003, 28.5% (6331/22229) continued training in an additional residency or fellowship program, compared with 31.6% residents (7390/23400) in AY 2006–2007. Across all years, approximately 95% of the residents continuing GME entered a fellowship program rather than entering another pipeline residency.

Table 1.

Residents Who Graduate From Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–Accredited Pipeline Specialty Programs and Continue Graduate Medical Education (GME), From Academic Year (AY) 2002–2003 to AY 2006–2007, by Specialty

Among pipeline specialties, the largest increases in the percent of graduates continuing training were in nuclear medicine (21.3% [17/80] to 28.2% [22/78]), pediatrics (32.7% [791/2417] to 39.2% [996/2538]), anesthesiology (19.9% [268/1349] to 26.2% [388/1479]), and neurology (46.6% [203/436] to 52.3% [267/511]). Specialties with the lowest percentage of graduates continuing training (<1%) across all AYs were obstetrics and gynecology, ophthalmology, and radiation oncology. These are specialties with no ACGME-accredited fellowship programs. An analysis that excluded the graduates from pipeline specialties without ACGME-accredited fellowships (nuclear medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, ophthalmology, and radiation oncology) showed an overall rate of continuing GME that was slightly higher but increased similarly across all years (30.8% [6307/20500] versus 28.5% [6331/22229] in AY 2002–2003 and 34.0% [7362/21653] versus 31.6% [7390/23400] in AY 2006–2007).

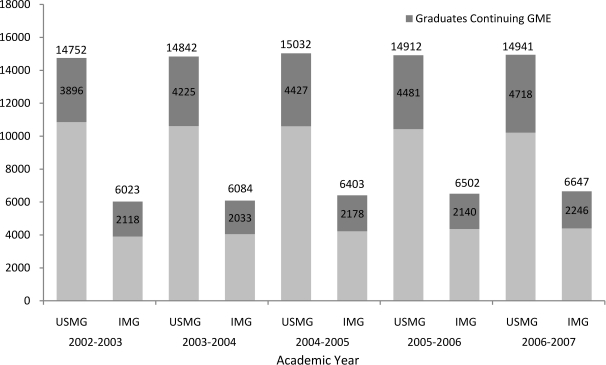

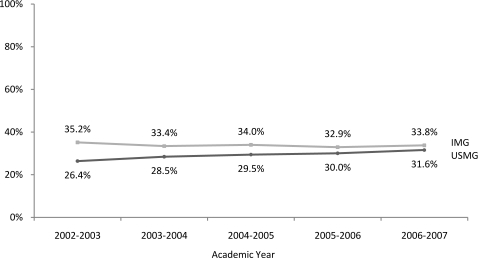

Our findings show differences in these trends for USMG and IMG graduates. The number of USMG pipeline graduates remained relatively stable during this time period (14 752 in AY 2002–2003 versus 14 941 in AY 2006–2007), while the number of USMGs entering additional training increased substantially (3896 versus 4718, respectively; see figure 2). In contrast, the number of IMGs graduating from pipeline specialties increased from 6023 in AY 2002–2003 to 6647 in AY 2006–2007, but the numbers of those seeking further GME training increased to a lesser extent (2118 versus 2246, respectively). This resulted in an overall increase in the rate of continuing GME among USMGs (26.4% [3896/14752] in AY 2002–2003 to 31.6% [4718/14941] in AY 2006–2007) and a net decrease in the rate of continuing GME among IMGs (35.2% [2118/6023] to 33.8% [2246/6647], respectively; see figure 3).

Figure 2.

Total Number of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–Accredited Pipeline Program Graduates and the Number Continuing Graduate Medical Education (GME), From Academic Year (AY) 2002–2003 to AY 2006–2007, by Type of Medical School Education. IMG Indicates International Medical Graduate; USMG Indicates US Medical School Graduate

Figure 3.

Rate of Continuing Graduate Medical Education (GME), From Academic Year (AY) 2002–2003 to AY 2006–2007, by Type of Medical School Education. IMG Indicates International Medical Graduate; USMG Indicates US Medical School Graduate

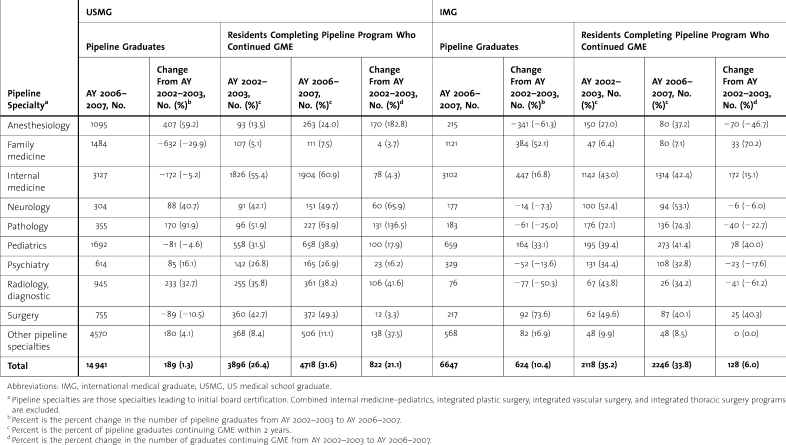

table 2 shows the number of USMG and IMG pipeline graduates and the continuance rates for those specialties having large graduate classes and at least 5% of graduates continuing GME. The largest increases in the number of USMG graduates during this time period occurred in anesthesiology, pathology, and diagnostic radiology; decreases occurred in the number of USMG graduates in surgery, family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics. The percent of USMG graduates continuing GME increased during this time across all specialties, with the largest percentage increases occurring in anesthesiology (13.5% [93/688] to 24.0% [263/1095]) and pathology (51.9% [96/185] to 63.9% [227/355]).

Table 2.

Residents Who Graduate From Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–Accredited Pipeline Specialty Programs and Continue Graduate Medical Education (GME), From Academic Year (AY) 2002–2003 to AY 2006–2007, by Specialty and Type of Medical School Education

The largest increases in the number of IMG pipeline graduates occurred in primary care specialties, while there were decreases in the number of IMGs graduating from anesthesiology, neurology, pathology, psychiatry, and diagnostic radiology. The decrease in the percent of IMGs continuing GME is particularly notable in diagnostic radiology (43.8% [67/153] versus 34.2% [26/76]) and surgery (49.6% [62/125] versus 40.1% [87/217]). For the majority of specialties, however, the continuing GME rate was still higher among IMGs compared to USMGs—especially in pathology (63.9% [227/355] for USMGs versus 74.3% [136/183] for IMGs in AY 2006–2007).

Discussion

Our results show a recent shift in the numbers of USMGs pursuing careers in ACGME-accredited specialties that were previously occupied by relatively large percentages of IMGs (eg, anesthesiology, pathology, and diagnostic radiology). At the same time, fewer USMGs graduate from primary care specialties, and these specialties show the largest growth for IMGs. These findings are consistent with patterns of change in pipeline specialty graduation found by other researchers.1,2

Previous reports1,4–6 on subspecialization showed that IMGs subspecialized at higher rates than USMGs. Our results indicate this trend is shifting, predominantly due to an increase in the number of USMG pipeline graduates continuing training across all specialties in our analysis. Possible explanations for this change include growth in the number and array of subspecialty programs available to residents,1–3 residents' desire to gain a competitive edge,9 and a real or perceived lack of preparedness to enter practice as graduates of pipeline residencies. Supporting this latter interpretation is a study reporting that almost 30% of surgical residents did not feel confident performing procedures independently following graduation.9 Another notable finding in our data is that 5% of pipeline graduates reenter another pipeline specialty. Reasons may include dissatisfaction with initial specialty choice, lifestyle factors, need for broader clinical context, and availability of research opportunities.9,10

Our study has several limitations. First, we limited tracking of residents to the 2-year period following graduation; our estimates do not account for those entering the workforce and then reentering GME training more than 2 years after graduation. Second, our data may underrepresent continuing GME rates, as we are unable to track residents into fellowship programs not accredited by the ACGME. Despite these limitations, our findings offer important new data on how many and in which specialties graduates pursue additional training, suggesting a changing trend in subspecialization rates compared with the findings of previously published studies.1–8

Conclusions

With the proliferation of GME subspecialty programs available to pipeline program graduates, it is apparent that longitudinal tracking of residents, as is possible with ACGME data, helps describe the pathways that residents are taking to enter practice. This pathway has become more diverse, with an increase in subspecialization, while the supply of practicing physicians has remained relatively constant. The increasing rate at which residents are continuing GME has implications for the supply of physicians entering full-time practice, and for the availability of primary and subspecialty physicians. The relatively stable number of pipeline positions may also have implications for the availability of residency positions for US medical school graduates, particularly given the significant projected increase in the number of USMGs with the opening of a number of new medical schools.11 By tracking residents through the pipeline of GME, we are better prepared to predict trends in physician supply, as well as the effects of increased subspecialization on the profession itself and the public's access to medical resources. Future analyses should assess continuing GME rates by education type, sex, geographic region, and other relevant variables to contribute to a comprehensive assessment of the numbers and types of physicians available for clinical practice.

Footnotes

All authors are at the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Lauren M. Byrne, MPH, is Data Analyst in the Applications and Data Analysis Department; Kathleen D. Holt, PhD, is Senior Analyst and Director of Special Projects in the Applications and Data Analysis Department and adjunct professor the Department of Family Medicine at University of Rochester; Thomas Richter, MA, is Director, Data Systems and Data Analysis in the Applications and Data Analysis Department; Rebecca S. Miller, MS, is Senior Vice President in the Applications and Data Analysis Department; and Thomas J. Nasca, MD, MACP, is ACGME's chief executive officer and Professor of Medicine at Jefferson Medical College.

We thank the Department of Applications and Data Analysis at the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education for collecting and ensuring the quality and accuracy of the graduate medical education data.

The ACGME provided support for Ms. Byrne, Dr. Holt, Mr. Richter, Ms. Miller, and Dr. Nasca for this research.

The funding body had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Brotherton S. E., Rockey P. H., Etzel S. I. US graduate medical education, 2004–2005: trends in primary care specialties. JAMA. 2005;294((9)):1075–1082. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.9.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salsberg E., Rockey P. H., Rivers K. L., Brotherton S. E., Jackson G. R. US residency training before and after the 1997 Balanced Budget Act. JAMA. 2008;300((10)):1174–1180. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stitzenberg K. B., Sheldon G. F. Progressive specialization within general surgery: adding to the complexity of workforce planning. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201((6)):925–932. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.06.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borman K. R., Vick L. R., Biester T. W., Mitchell M. E. Changing demographics of residents choosing fellowships: longterm data from the American Board of Surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206((5)):782–788. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.12.012. discussion 788–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn M. R., Miller R. S. The shifting sands of graduate medical education. JAMA. 1996;276((9)):710–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller R. S., Dunn M. R., Richter T. Graduate medical education, 1998–1999: a closer look. JAMA. 1999;282((9)):855–860. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller R. S., Dunn M. R., Richter T. H., Whitcomb M. E. Employment-seeking experiences of resident physicians completing training during 1996. JAMA. 1998;280((9)):777–783. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.9.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brotherton S. E., Rockey P. H., Etzel S. I. US graduate medical education, 2003–2004. JAMA. 2004;292((9)):1032–1037. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.9.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeo H., Viola K., Berg D., et al. Attitudes, training experiences, and professional expectations of US general surgery residents: a national survey. JAMA. 2009;302((12)):1301–1308. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorsey E. R., Jarjoura D., Rutecki G. W. Influence of controllable lifestyle on recent trends in specialty choice by US medical students. JAMA. 2003;290((9)):1173–1178. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Association of American Medical Colleges. Analysis of the 2009 AAMC Survey. Available at: http://www.aamc.org/workforce/enrollment/enrollment2010.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2010.