Abstract

Introduction

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) recommends resident portfolios as 1 method for assessing competence in practice-based learning and improvement. In July 2005, when anesthesiology residents in our department were required to start a portfolio, the residents and their faculty advisors did not readily accept this new requirement. Intensive education efforts addressing the goals and importance of portfolios were undertaken. We hypothesized that these educational efforts improved acceptance of the portfolio and retrospectively audited the portfolio evaluation forms completed by faculty advisors.

Methods

Intensive education about the goals and importance of portfolios began in January 2006, including presentations at departmental conferences and one-on-one education sessions. Faculty advisors were instructed to evaluate each resident's portfolio and complete a review form. We retrospectively collected data to determine the percentage of review forms completed by faculty. The portfolio reviews also assessed the percentage of 10 required portfolio components residents had completed.

Results

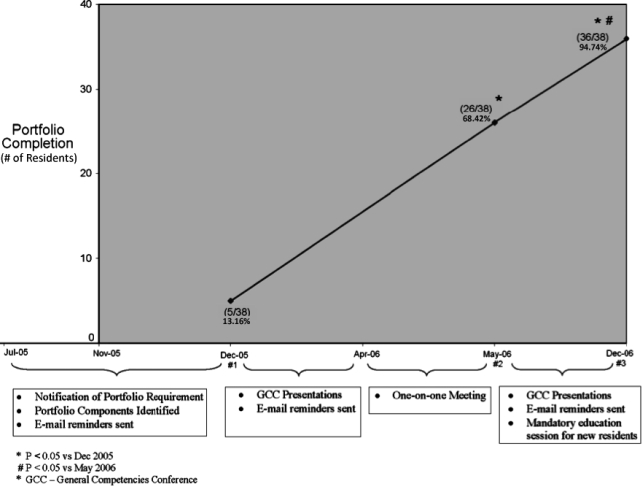

Portfolio review forms were completed by faculty advisors for 13% (5/38) of residents during the first advisor-advisee meeting in December 2005. Initiation of intensive education efforts significantly improved compliance, with review forms completed for 68% (26/38) of residents in May 2006 (P < .0001) and 95% (36/38) in December 2006 (P < .0001). Residents also significantly improved the completeness of portfolios between May and December of 2006.

Discussion

Portfolios are considered a best methods technique by the ACGME for evaluation of practice-based learning and improvment. We have found that intensive education about the goals and importance of portfolios can enhance acceptance of this evaluation tool, resulting in improved compliance in completion and evaluation of portfolios.

Introduction

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Outcome Project1 changed the focus and tools for assessment of graduate medical education by requiring that programs include educational activities and assessment of resident competence in 6 general competencies. Programs also are required to use outcome data to make ongoing improvements to their training programs and document that educational goals for individual residents and the program are being met.

The ACGME requires multiple assessment methods for evaluating the competencies.2 The traditional methods of evaluation in anesthesiology training programs—global evaluations performed by faculty who have worked with a resident to assess patient care abilities and performance on standardized multiple choice examinations to assess medical knowledge—remain important components but are not ideally suited for the assessment of resident competence in practice-based learning and improvement (PBLI), systems-based practice (SBP), and aspects of professionalism. Securing valid assessment methods that are feasible and practical is a challenge, given the limited financial and personnel resources available to many academic departments.

The ACGME, in cooperation with the American Board of Medical Specialties, developed a Toolbox of Assessment Methods that describes tools that could be used to assess resident competence, including the portfolio—a collection of materials that provides evidence of a student's learning and achievement.3 Because portfolios provide a structure for self-reflection and assessment that can lead to a plan for self-improvement, they are considered the most effective method for evaluating PBLI and also are useful for evaluating aspects of SBP and professionalism. Portfolios have been used extensively in general education and are being increasingly used in undergraduate and graduate medical education.4–7 An advisory group consisting of current and former residency program directors also recommended the use of a portfolio with a checklist assessment for evaluation of PBLI.8

Portfolio Design

Our department's General Competencies Committee decided to use the portfolio as a learning and evaluation tool for PBLI and some components of professionalism and SBP. One important component of the portfolio is the health care matrix, which provides a framework for the resident to assess individual and health care system performance in an actual patient care episode and identify opportunities for improvement using the general competencies and Institute of Medicine aims.9 We felt the portfolio could be an effective and practical assessment method because it could be used for formative and summative evaluations.

As we developed our implementation plan, we discovered little information about the use of portfolios in anesthesiology residency programs. However, several other specialties had reported on their use of portfolios, including internal medicine,10 pediatrics,1,6,11 ophthalmology,12 and psychiatry.1,13,14 Where appropriate, we integrated their strategies into our portfolio development plan.

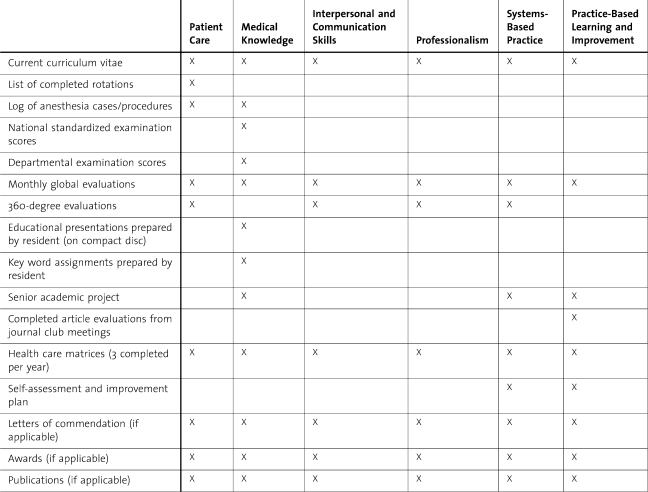

Several types of portfolios have been described in the literature. We chose to use a structured portfolio in which members of the General Competencies Committee developed the framework of what should be included, but residents determined the actual content of the portfolio. Holmboe et al15 suggested this type of portfolio is most appropriate for assessment in outcomes-based evaluation programs and recommended specific characteristics be included to improve the document's validity. These characteristics include a multifaceted and triangulated approach to evaluation (eg, a variety of evaluation methods are used and several can evaluate more than one competency as illustrated in table 1), evidence of resident self-assessment and reflection, and a document that is longitudinal, encompassing the entire residency training period. Our portfolio framework incorporated all of these attributes.

Table 1.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Competencies Evaluated by Each Portfolio Component

Implementation

In July 2005, all residents in our anesthesiology department were required to develop a portfolio for assessment of PBLI and some components of SBP and professionalism. The portfolios were to be evaluated by faculty advisors on a semiannual basis. Initially neither residents nor faculty readily accepted this new evaluation tool, and intensive education addressing the goals and importance of portfolios was undertaken several months after implementation of the portfolios.

Methods

We hypothesized that these educational efforts would improve acceptance of the portfolio as an assessment method and retrospectively audited the portfolio evaluation forms completed by faculty advisors during an 18-month period to determine if compliance with resident portfolio completion and faculty portfolio evaluation had improved. The University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board determined that this project qualified as an exempt study.

Residents and faculty were advised of the portfolio requirement, including the materials expected to be included in the portfolio document (table 2), via e-mail communication between July 2005 and November 2005. The first portfolio assessment was performed during our department's semiannual faculty advisor–resident advisee meetings in December 2005. Faculty and residents have no other responsibilities during this designated 1-hour period.

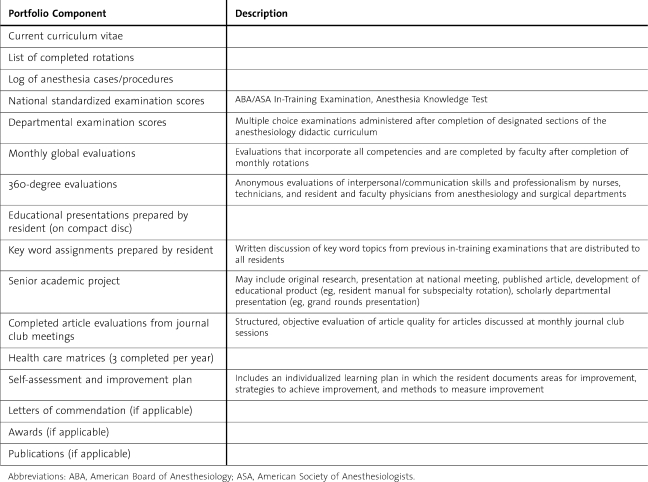

Table 2.

Required Components of Resident Portfolio

Intensive education about the goals and importance of resident portfolios began in January 2006 and comprised ongoing presentations at departmental conferences attended by residents and faculty and additional e-mail communications. These efforts culminated with one-on-one portfolio education sessions with all residents (n = 38) and faculty advisors (n = 27) that were conducted by the residency program director and/or the chair of the department's General Competencies Committee during April 2006. The purpose of these 15-minute sessions was to describe the portfolio and each of its components to the resident and advisor. Participants also were shown an example of a complete and well-organized portfolio. Particular emphasis was placed on educating residents and their advisors about the components of the portfolio considered most important for assessing competence in PBLI, including the health care matrix and the resident's individualized self-assessment and improvement plan. Following these one-on-one educational sessions, ongoing education occurred via e-mail communications and presentations at department-wide educational conferences held in the month before each scheduled portfolio review. When new residents joined the department in July 2006, a mandatory portfolio education session for these residents was conducted and written expectations for the portfolio were distributed to them.

Three faculty advisor–resident advisee meetings were scheduled in December 2005 and May and December of 2006 to allow faculty advisors to conduct a portfolio assessment with their advisees. The assessments consisted of 2 parts: a checklist of all required components graded as complete or incomplete and a qualitative assessment of the resident's health care matrices and self-assessment and improvement plan.

We retrospectively collected blinded data from all portfolio evaluation forms that were completed during the 3 evaluation periods. Some components of the portfolio were not pertinent for all 4 years of residency (postgraduate year [PGY]-1 to PGY-4). For instance, none of the PGY-1 rotations include 360-degree evaluations, and the senior academic project does not become a part of the portfolio until the PGY-4 year. Ten portfolio components were identified as required components for all levels of residency training: the curriculum vitae, a list of completed rotations, a current procedure log, in-training examination scores, department examination scores, global evaluations from completed rotations, key word assignments (a summary explanation of a key word from the anesthesiology in-training examination that is written by the resident and distributed to all residents for their use), assessment forms for journal club articles, health care matrices, and self-assessment and improvement plan. The faculty advisors evaluate the number of complete components for each portfolio review for each of the assessment periods. The researchers analyzed the percentage of portfolio evaluation forms completed by faculty during each evaluation period and the number of completed portfolio components for each evaluation that was performed. Data were analyzed using Fisher exact test and paired t test as appropriate to determine if resident and faculty compliance with our portfolio requirement improved after intensive educational efforts. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Throughout the study period of July 2005 to December 2006, there were 38 anesthesiology residents in the training program: 8 at the PGY-1 level and 10 each at the PGY-2 to PGY-4 levels. At the December 2005 advisor-advisee meetings, portfolio evaluation forms were completed by faculty members for only 5 of the 38 residents (13%). After initiation of our intensive one-on-one education about portfolios, significant improvement among residents and faculty in accepting this assessment method occurred as shown in the figure. At the May 2006 advisor-advisee sessions, the number of completed portfolio evaluation forms increased to 26 of 38 residents (68%, P < .0001 compared with December 2005). With the continuation of educational efforts between May and December of 2006, successful acceptance of this evaluation tool by faculty and residents was maintained, with portfolio evaluation forms completed for 36 of 38 residents at the December 2006 sessions (95%, P < .0001 compared with December 2005). In addition, further improvement in compliance with the portfolio requirement occurred between the May 2006 and December 2006 advisor meetings (68% vs 95%, P = .0062).

Figure.

Relationship Between Portfolio Education Efforts and Completion of Portfolio Evaluations During Faculty Advisor–Resident Advisee Meetings

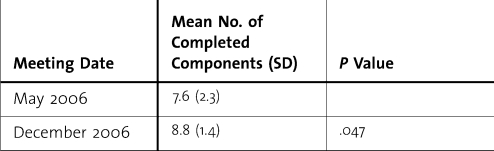

Because the number of portfolios that were reviewed by faculty was quite small (n = 5) for the December 2005 period, we did not evaluate the mean number of completed components of those portfolios. The completeness of portfolios for the May 2006 and December 2006 assessment periods is reported in table 3. The residents significantly improved the completeness of their portfolios in December 2006 as compared with May 2006 (8.8 vs 7.6 complete components, P = .047).

Table 3.

Completed Portfolio Components at May and December 2006 Portfolio Review Sessions

Discussion

When we introduced the portfolio as an assessment method, our residency curriculum already included education and evaluation techniques focused on the general competencies, such as 360-degree evaluations. We did not anticipate that significant educational efforts regarding resident portfolios would be necessary. In retrospect, our initial expectation that compliance with the portfolio requirement would be readily accepted was probably naïve. Without a full understanding of the goals of the portfolio, some residents perceived this as additional “busy” work without educational merit. Although faculty had generally accepted integration of the general competencies into our residency curriculum, previous changes to our resident evaluation process had only required additional effort from a few key faculty members in our general competencies plan.

In actuality, implementation of portfolios required significant involvement of all faculty because advisors were expected to evaluate their advisee's portfolio. The poor response of both residents and faculty to the first portfolio assessment session in December 2005 (only 13% of expected evaluations were completed) indicated that further efforts by our General Competencies Committee would be required if we were to successfully adopt this assessment method.

Our intensive education efforts included ongoing presentations about the goals and importance of portfolios at our department-wide conferences that were reinforced with several e-mail communications to residents and faculty, one-on-one educational sessions between all residents and faculty and either the residency program director or the chair of the General Competencies Committee, and mandatory portfolio education meetings when new residents joined the department. We believe the one-on-one sessions and the ongoing nature of our educational efforts, which continue to date and now include podcasts, are the most important factors in the significantly increased faculty and resident acceptance of portfolios. Residents now have a clear understanding of the goals of the portfolio and find it to be an education and assessment tool of which they can take ownership. It is also likely that our intensive efforts served to make department members aware of the importance that department leaders place on the use of resident portfolios as an essential tool for the evaluation of residents' competence.

Our study has several limitations. Because of the retrospective nature of our analysis and the lack of a control group, we cannot prove that our education efforts were responsible for the increased compliance with portfolio completion and faculty assessment. Other factors may have played a role in this outcome. During the study period, further integration of the ACGME general competencies into our residency curriculum occurred. Our traditional weekly department-wide Case Discussion Conference was renamed the General Competencies Conference. In keeping with the name change, significant emphasis was placed on incorporating discussion of the competencies of professionalism and SBP in presentations and each case presentation by a resident was expected to include a completed health care matrix. These changes might have contributed to the improved compliance with the completion and evaluation of portfolios over time without our educational efforts.

When we first considered introducing portfolios into our residency curriculum, we questioned the feasibility of this assessment method. However, we discovered that most of the time and effort required to successfully implement resident portfolios were able to be integrated into already existing components of our training program, such as our General Competencies Conference and our semiannual faculty advisor–resident advisee meetings. The one-on-one educational sessions did require an additional time commitment, with both the residency program director and the chair of the General Competencies Committee being provided with 3 nonclinical days to complete those meetings. By meeting with residents and faculty in an office located within the operating room suite, these meetings were able to occur primarily when residents and faculty had some available time between their clinical responsibilities. Thus, faculty and residents did not need to be relieved from clinical duties in most situations to complete these educational sessions. In addition, providing the faculty who had responsibility for these sessions with nonclinical time to accomplish these duties helped reinforce that the departmental leadership considered the portfolio an important initiative.

Resident development of portfolios requires an additional time commitment. However, residents have also found that having an organized portfolio saved time when they began the licensing and credentialing process in preparation for postresidency employment. Experience with portfolio development could be useful to our residents after residency when they participate in the American Board of Anesthesiology's Maintenance of Certification in Anesthesiology. Maintenance of Certification in Anesthesiology requires that anesthesiologists demonstrate competence in the same 6 ACGME competencies, including PBLI. The American College of Surgeons recommended that a portfolio approach be used to document practice-based learning and improvement activities in their maintenance of certification process.16 Recently the American Board of Anesthesiology announced that the performance assessment and practice improvement portion of Maintenance of Certification in Anesthesiology will require completion of a case evaluation, including self-assessment of aspects of practice, implementation of an improvement plan, and self-determination of the improvement that has occurred.17 This process is similar to the self-assessment and improvement plan that our residents currently perform on a semiannual basis.

Conclusions

Resident portfolios have been recommended by the ACGME as a best method for assessment of the PBLI competency, yet many anesthesiology residents and faculty are unfamiliar with this evaluation tool. Implementation of a portfolio requirement in our residency initially was met with apathy by faculty and residents. We found that intensive education about the goals and importance of portfolios was associated with a significant improvement in the acceptance of this technique, as documented by increases in the number of completed portfolios and the number of portfolio evaluations completed by faculty advisors. Similar education efforts for faculty and residents may be effective in assisting programs across specialties as they strive to implement and gain widespread acceptance of portfolios.

Footnotes

All authors are located at the University of Kentucky, College of Medicine, Department of Anesthesiology.

References

- 1.ACGME Outcome Project. Available at: www.acgme.org/Outcome. Accessed January 26, 2009.

- 2.Tetzlaff J. E. Assessment of competency in anesthesiology. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:812–825. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264778.02286.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACGME Outcome Project. Toolbox of assessment methods ©. Available at: www.acgme.org/Outcome/assess/Toolbox.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2009.

- 4.Gordon J. Assessing students' personal and professional development using portfolios and interviews. Med Educ. 2003;37:335–340. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Driessen E. W., Tartwijk J., Overeem K., Vermunt D., van der Bleuten C. Conditions for successful reflective use of portfolios in undergraduate medical education. Med Educ. 2005;39:1230–1235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melville C., Rees M., Brookfield D., Anderson J. Portfolios for assessment of pediatric specialist registrars. Med Educ. 2004;38:1117–1125. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lonka K., Slotte V., Halttunen M., et al. Portfolios as a learning tool in obstetrics and gynaecology undergraduate training. Med Educ. 2001;35:1125–1130. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ACGME Outcome Project. Outcome project think tank. Available at: www.acgme.org/outcome/project/thinktank.asp. Accessed January 26, 2009.

- 9.Bingham J. W., Quinn D. C., Richardson M. G., Miles P. V., Gabbe S. G. Using a healthcare matrix to assess patient care in terms of aims for improvement and core competencies. J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31:98–105. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(05)31014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinsky L. E., Fryer-Edwards K. Diving for PERLS: working and performance portfolios for evaluation and reflection on learning. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:582–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carraccio C., Englander R. Evaluating competence using a portfolio: a literature review and web-based application to the ACGME competencies. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16:381–387. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1604_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee A. G., Carter K. D. Managing the new mandate in resident education: a blueprint for translating a national mandate into local compliance. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1807–1812. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Sullivan P. S., Reckase M. D., McClain T., Savidge M. A., Clardy J. A. Demonstration of portfolios to assess competency of residents. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2004;9:309–323. doi: 10.1007/s10459-004-0885-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarvis R. M., O'Sullivan P. S., McClain T., Clardy J. A. Can one portfolio measure the six ACGME general competencies? Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28:190–196. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.28.3.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmboe E. S., Rodak W., Mills G., McFarlane M. J., Scheultz H. J. Outcomes-based evaluation in resident education: creating systems and structured portfolios. Am J Med. 2006;119:708–714. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sachdeva A. K. The new paradigm of continuing education in surgery. Arch Surg. 2005;140:264–269. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guidry O. F. Maintenance of certification in anesthesiology (MOCA®)–an update. ABA News. 2007;20:3–15. [Google Scholar]