Abstract

Oxidative stress and inflammation are fundamental for the onset of aging and appear to be causatively linked. Previously, we reported that hepatocytes from aged rats, compared with young rats, are hyperresponsive to interleukin-1β (IL-1β) stimulation and exhibit more potent c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation and attenuated interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-1 (IRAK-1) degradation. An age-related increase in the activity of neutral sphingomyelinase-2 (NSMase-2), a plasma membrane enzyme, was found to be responsible for the IL-1β hyperresponsiveness. The results reported here show that increased NSMase activity during aging is caused by a 60–70% decrease in hepatocyte GSH levels. GSH, at concentrations typically found in hepatocytes from young animals, inhibits NSMase activity in a biphasic dose-dependent manner. Inhibition of GSH synthesis in young hepatocytes activates NSMase, causing increased JNK activation and IRAK-1 stabilization in response to IL-1β, mimicking the hyperresponsiveness typical for aged hepatocytes. Vice versa, increased GSH content in hepatocytes from aged animals by treatment with N-acetylcysteine inhibits NSMase activity and restores normal IL-1β response. Importantly, the GSH decline, NSMase activation, and IL-1β hyperresponsiveness are not observed in aged, calorie-restricted rats. In summary, this report demonstrates that depletion of cellular GSH during aging plays an important role in regulating the hepatic response to IL-1β by inducing NSMase-2 activity.— Rutkute, K., R. H. Asmis, and M. N. Nikolova-Karakashian. Regulation of neutral sphingomyelinase-2 by GSH: a new insight to the role of oxidative stress in aging-associated inflammation.

Supplementary key words: ceramide, calorie restriction, interleukin-1 receptor-associatedkinase-1, c-JunN-terminalkinase, reduced glutathione

Increased basal inflammation is a phenomenon emblematic of the aging process. It is characterized by increased concentrations of serum markers such as C-reactive protein and serum amyloid A (1) as well as by the activation of proinflammatory signaling molecules such as c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (2), nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) (3), and CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins α and β (4). According to the oxidative stress hypothesis of aging, changes in mitochondrial functions and the deterioration of anti-oxidant defense mechanisms lead to an imbalance in the production and neutralization of free radicals, which in turn induces tissue damage and inflammation. Indeed, oxidative stress seems to play a fundamental role in the onset of aging-associated inflammation, because a decline in reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation brought about by calorie restriction (5) or by antioxidant supplementation decreases the expression of various inflammatory markers in aged animals. It has been proposed that the excess ROS generated during aging stimulate the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, thus creating a proinflammatory environment (5). However, despite the fact that basal levels of some cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), seem to increase with age, these increases are modest, and it is not yet clear whether they are sufficient to evoke an inflammatory response. Moreover, the systemic concentrations of other cytokines, including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), remain unchanged in healthy elderly (6, 7).

Earlier studies have shown that some cells, including peritoneal macrophages (8, 9), hepatocytes (4), and glial cells, become more responsive to inflammatory challenges with age, apparently as a result of changes in the cell signaling mechanisms. We previously reported that the hepatic response to IL-1β is substantially upregulated during aging (10). IL-1β is a major proinflammatory cytokine that binds to the interleukin-1 receptor type I (IL-1RI). IL-1RI and the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) receptor are the main representatives of the Toll-like receptor family of receptors that activate a conserved signaling pathway. The binding of IL-1β to IL-1RI recruits the IL-1RI accessory protein and several other adaptor proteins (11). Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-1 (IRAK-1) and IRAK-4 then bind to the receptor complex, where IRAK-1 becomes hyperphosphorylated and recruits tumor necrosis factor-associated factor-6 (TRAF-6) (12). Subsequently, the IRAK-1/IRAK-4/TRAF-6 complex leaves the receptor to interact with transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase-1 (TAK-1) (13). This ultimately leads to the activation of transcription factors, including activator protein-1 and NF-κB through JNK (14) and IκB kinases, respectively. The phosphorylation of IRAK-1 is essential for the activation of downstream signaling molecules; however, IRAK-1 phosphorylation also leads to its ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation (15), which effectively terminates the signaling cascade. It is important to note that IRAK-1 stability is a critical parameter determining the magnitude of the cellular response and has been implicated in LPS sensitization and/or the onset of LPS tolerance (16–18).

In a recent study, we compared IL-1β signaling in young and aged rat hepatocytes and observed significant differences (10). In hepatocytes isolated from aged rats, JNK was activated by very low IL-1β doses that had no effect on hepatocytes from young animals. Moreover, the magnitude of JNK activation was substantially higher, suggesting that cells from aged animals are hyperresponsive to IL-1β stimulation. The IL-1β hyperresponsiveness was not attributed to changes in the expression of IL-1RI, total JNK, IRAK-1, or TAK-1. Rather, a constitutive age-dependent increase in the basal activity of neutral sphingomyelinase-2 (NSMase-2) appeared to be responsible. NSMase-2, which is a plasma membrane protein that is activated by IL-1β, regulates the magnitude of JNK phosphorylation by inhibiting IRAK-1 phosphorylation and its subsequent ubiquitination and degradation (19). We have shown that overexpression of NSMase-2 in hepatocytes from young rats induces hyperresponsiveness to IL-1β stimulation. In contrast, inhibition of NSMase-2 activity in hepatocytes from aged animals, either by small interfering RNA silencing or pharmacological inhibitors, restores the normal IL-1β response (10). These observations led us to postulate that age-related changes in NSMase activity were both sufficient and required for hepatic IL-1β hyperresponsiveness.

NSMase-2 modulates cellular levels of ceramide, thereby regulating cell growth and differentiation, apoptosis, and inflammation (19, 20). Numerous studies have established a central role for ceramide as a mediator of cellular responses to stress. More recent reports, however, have begun to delineate novel important functions of ceramide in the aging process. Significant accumulation of ceramide and upregulation of sphingomyelinase activity have been found in livers and brains of aged rodents (21–23). Increased ceramide generation has been implicated in the upregulation of LPS-induced prostaglandin E2 production in macrophages from aged mice (24), in the onset of senescence-associated growth arrest in fibroblasts (25), and in the regulation of telomerase activity in human neuroblastoma cell lines (26). Studies in Drosophila melanogaster and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have shown that abnormal ceramide metabolism is involved in photoreceptor degeneration during aging (27) and in lifespan determination (28, 29). Together, these studies suggest that the aging-induced increase in ceramide plays a role in the mechanism of aging.

Interestingly, increased NSMase activity during aging may be causatively linked to the increased state of oxidative stress. Indications to that effect come from the fact that reduced glutathione is a potent and reversible inhibitor of NSMase activity (30). Depletion of GSH in response to TNF-α stimulation (31) or hypoxia (32) activates NSMase and increases ceramide content, whereas increases in cellular GSH levels prevent the hypoxia-induced generation of ceramide and apoptosis. Studies in whole animal models have confirmed the role of GSH as a negative regulator of NSMase activity in liver (33) and brain (34). The goal of this study was to determine whether GSH plays a role in the age-related increase in hepatic NSMase activity leading to IL-1β hyperresponsiveness with age.

Methods

Materials

Young (3–4 months), aged (20–22 months), and aged calorie-restricted (20 months) male Fisher 344 rats were purchased from the National Institute of Aging (Bethesda, MD). Matrigel™ was from BD Bioscience (Bedford, MA). Recombinant rat IL-1β was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). 6-N-(7-Nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino-sphingomyelin (NBD-SM) was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). The enhanced chemifluorescent kit was from Amersham (Piscataway, NJ). The Bioxytech® GSH/GSSG-412™ assay kit was from OXIS International (Foster City, CA). Antibodies were from the following manufacturers: anti-phospho-JNK1/2 and anti-cyclophilin A were from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA); anti-β-actin and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); and anti-IRAK-1 was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). All other reagents were from Sigma and Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Primary hepatocyte isolation, culture, and treatments

All animals were housed in an American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-approved facility. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Kentucky and were done in conformity with the Public Health Service Policy on Human Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Before cell isolation, 35 mm tissue culture dishes were coated with 0.15 ml of 6.3 mg/ml Matrigel as described previously (35). Hepatocytes were isolated from ether-anesthetized rats by in situ collagenase perfusion (19). Cell viability as determined by Trypan Blue exclusion assay was >80% for both young and aged rats. The cells were plated at a density of 1 × 106 per dish in 1.5 ml of Waymouth's medium supplemented with insulin (0.15 μM) and penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/ml). Cultures were maintained for 5 days at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, with replacement of the medium at 3 h and then every 48 h.

Adenovirus encoding mouse NSMase-2 under doxycyclin-inducible promoter (AdNSMase-2) (19) was used to overexpress NSMase-2 as described previously (19). Hepatocytes were infected at 48 h after isolation at a multiplicity of infection between 2 and 5. Expression of the transgene was confirmed by Western blotting. Control cells were infected but not induced. Treatments with IL-1β were done at 72 h after infection. Where indicated, pretreatments with l-buthionine-S,R-sulfoximine (BSO), H2O2, or N-acetylcysteine (NAC) were performed before treatment with IL-1β.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting

The medium was aspirated and the Matrigel was reliquified by incubating with PBS containing 5 mM EDTA for 30 min at 4°C. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 500 g for 4 min. After one rinse, cell pellets were resuspended in 50 μl of lysis buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM Na2VO4, 1 mM NaF, and 1:200 (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail]. The cells were incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 16,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Protein concentration in cell extracts was measured, and proteins (usually 80 μg/lane) were resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to an Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Specified proteins were detected using the antibodies described above in Materials. Protein-antibody interactions were visualized using enhanced chemifluorescent substrate and a Storm 860 fluorescence scanning instrument and analyzed using ImageQuant 5.0 software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

NSMase activity assay

NSMase activity was assayed as described previously with minor modifications (10). Briefly, hepatocytes were resuspended in 100 μl of lysis buffer and homogenized by sonication for 5 min. A total of 50 μg of protein was incubated in an assay mix (400 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 20 μM NBD-SM, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.01% Triton X-100, 5 mM NaF, and protease inhibitors) for 30 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by adding 1 ml of methanol. Cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 16,000 g. The supernatants were analyzed by HPLC on a reverse-phase column (Nova PAC, C18) using methanol-water-orthophosphoric acid (850:150:0.150, v/v) as a mobile phase at a flow rate of 2 ml/min (36). NBD-ceramide formation was quantified after calibration using NBD-ceramide as an exogenous standard, and it was proportional to the amount of protein added for up to 0.1 mg/assay.

Ceramide mass measurements

The lipids were extracted by the method of Bligh and Dyer (37), modified as described previously (38), and analyzed by thin-layer chromatography on silica gel 60 plates using chloroform-methanol-triethylamine-2-propanol-0.25% potassium chloride (30:9:18:25:6, v/v) as the developing solvent. The relevant regions of the plate were scraped, and ceramide was eluted from the silica gel (35) and quantified by HPLC after an acid hydrolysis in 0.5 M HCl in methanol at 65°C for 15 h (38).

Determination of cellular glutathione

For the HPLC method, hepatocytes were harvested, suspended in 1.5 ml of 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5) buffer containing 1 mM EDTA, and processed as described previously (39). Briefly, after taking an aliquot for DNA determination, samples were split into two equal aliquots for the determination of GSSG and total glutathione (GSH + GSSG). The samples designated for GSSG determination were pretreated with N-ethylmaleimide (3.8 mM) to alkylate free thiol groups, whereas those for total glutathione were left untreated. Proteins were precipitated with 100 μl of cold 18% perchloric acid; supernatants were neutralized with 1 M KPi (pH 7.0) and reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol for 60 min at room temperature. Samples were derivatized with 11 mM o-phthalaldehyde, and glutathione was quantified on a reverse-phase HPLC system (Jasco, Inc., Easton, MD) equipped with a spectrofluorometer (FP-920; Jasco). Glutathione was separated on a Brownlee 22 cm C18 ODS analytical column (5 μm) using 21 mM propionate buffer (in 35 mM NaPi, pH 6.5)-acetonitrile (95:5, v/v) as a mobile phase at a flow rate of 1.2 ml/min. Excitation wavelength was 340 nm, and emission wavelength was 420 nm. Levels of GSH were calculated as the difference between GSH + GSSG and GSSG.

For use of the Bioxytech® GSH/GSSG-412™ assay kit, hepatocytes were harvested as described above and suspended in 250 μl of PBS with 5 mM EDTA. A 50 μl aliquot was taken for protein measurement for normalization purposes, and 100 μl aliquots were used for each GSH + GSSG and GSSG determination according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

After assuming equal variance across groups, differences were assessed using Student's t-test or two-way ANOVA where applicable. Results are presented as means ± SD.

Results

Potentiation of the response to IL-1β during aging

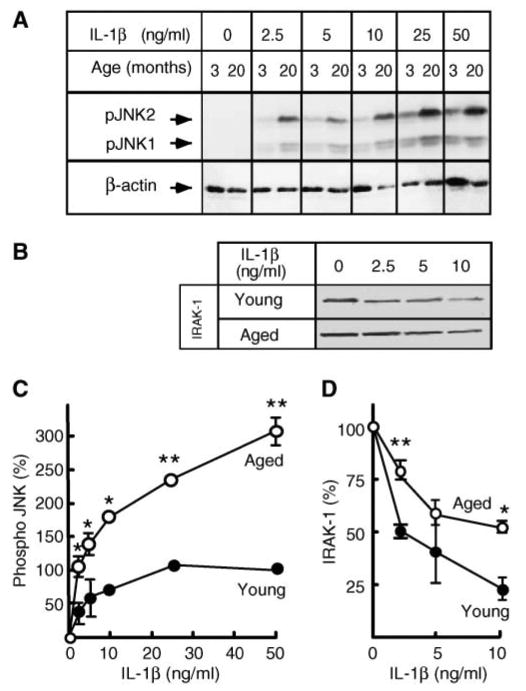

In the course of aging, hepatocytes become more sensitive to IL-1β stimulation (10). Cells isolated from the aged (20–22 months) Fisher 344 rats responded vigorously to low IL-1β concentrations that had little effect in young (3–4 months) rats (Fig. 1). Moreover, the extent of JNK phosphorylation was substantially higher in aged hepatocytes at all IL-1β concentrations used (Fig. 1A, C) and correlated with higher JNK activity as judged by enhanced phosphorylation of c-Jun (data not shown) as well as with the stabilization of IRAK-1 (Fig. 1B, D). These differences were not attributable to changes in the basal levels of IL-1β receptor, IRAK-1, TAK-1, or total JNK (data not shown). We showed previously that hepatic IL-1β hyperresponsiveness during aging is caused by a constitutive increase of NSMase-2 activity and that overexpression of NSMase-2 in young hepatocytes is sufficient to induce the aging phenotype (10). Moreover, suppression of basal NSMase-2 activity in aged hepatocytes using small interfering RNA restores the normal response to IL-1β, further confirming that NSMase-2 plays an important role in the onset of inflammation during aging (10). It remains unclear, however, why the basal activity of NSMase-2 increases with age.

Fig. 1.

Hepatocytes from aged rats are hypersensitive to interleukin-1β (IL-1β). A, C: Dose response of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) phosphorylation. Hepatocytes from young (3–4 months) and aged (20–22 months) rats were treated with the indicated concentrations of IL-1β for 15 min. JNK phosphorylation was determined by Western blotting using an antibody specific for the dually phosphorylated forms of JNK1 and JNK2 (pJNK1/2). β-Actin was used as a control for uniform loading. The combined intensity of JNK1 and JNK2 was used for quantification. Data are presented as percentages of the phospho-JNK levels in young hepatocytes at 50 ng/ml IL-1β. Values are means ± SD (n = 3). * P < 0.01, ** P < 0.001. B, D: Dose response of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-1 (IRAK-1) degradation. Hepatocytes from young (3–4 months) and aged (20–22 months) rats were treated with the indicated concentrations of IL-1β for 15 min. Levels of IRAK-1 were determined by Western blotting and quantified. Results are expressed as percentages of the IRAK-1 levels in untreated hepatocytes. Values are means ± SD (n = 3). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.005.

Aging is accompanied by a substantial GSH level decline in hepatocytes

It is known that GSH reversibly inhibits NSMase activity (30, 31); therefore, the increase in NSMase-2 activity could be attributable to a decline in GSH content with age. Indeed, studies by other investigators have found that liver GSH content decreases with age (40, 41). However, it has also been reported that there is no GSH depletion but only a decrease in the GSH/GSSG ratio, which reflects increased generation of GSSG (42, 43). To examine the effects of aging on GSH levels in hepatocytes, we used two independent analytical methods: an HPLC-based assay and the colorimetric Bioxytech® assay, normalized for the amount of DNA and protein, respectively (Table 1). The results from both assays were comparable, given that the average yield of DNA was 17 μg/mg protein. We found that GSH levels in hepatocytes from aged rats were significantly lower (by ∼60%) than in hepatocytes from young animals. These results correspond well to data reported by Hagen et al. (44) and Vericel et al. (45), who found 40–60% declines in GSH content in hepatocytes from 26 month old rats. Aging-associated differences in GSH levels were not observed (data not shown) between young and aged hepatocytes supplemented with NAC, a precursor of GSH biosynthesis, suggesting that GSH depletion in aged hepatocytes was not caused by a defect in GSH synthesis. Importantly, cellular NSMase activity and ceramide content increased with age (Table 1). These findings support the hypothesis of an inverse correlation between NSMase activity and GSH levels during the aging process.

TABLE 1. Effects of aging on cellular GSH levels, NSMase activity, and ceramide content.

| Assay | Young | Aged |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC-based assay (nmol/μg DNA) | ||

| Total glutathione | 15.90 ± 2.70 | 4.70 ± 0.10a |

| GSH | 15.8 ± 2.70 | 4.60 ± 0.10a |

| GSSG | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.45 ± 0.01 |

| Biotech® GSH/GSSG-412™ assay (nmol/mg protein) | ||

| Total glutathione | 237.70 ± 49.50 | 90.80 ± 24.50b |

| GSH | 237.50 ± 49.50 | 90.70 ± 24.50b |

| GSSG | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.00 |

| NSMase activity (pmol/mg protein/min) | 266.17 ± 28.96 | 479.00 ± 117.35c |

| Ceramide (nmol/mg protein) | 1.23 ± 0.20 | 1.76 ± 0.11c |

NSMase, neutral sphingomyelinase. Hepatocytes were isolated from young (3–4 months) and old (20–22 months) rats. GSH and GSSG levels were measured by HPLC or by Biotech® GSH/GSSG-412™ assay and normalized for the amount of DNA or protein, respectively. NSMase activity was assessed in cell homogenates using NBD-sphingomyelin as a substrate, whereas ceramide mass was measured by HPLC. Data are presented as means ± SD.

P < 0.05 (n = 2).

P < 0.01 (n = 4).

P < 0.001 (n = 3).

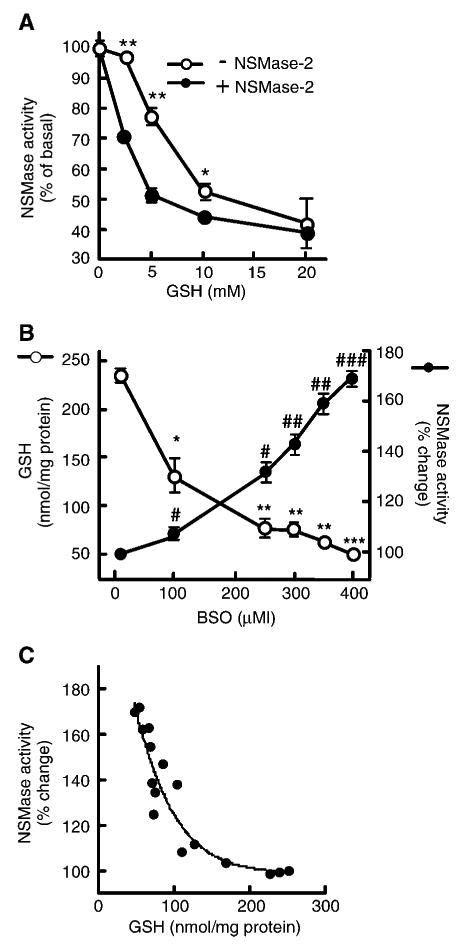

GSH is a potent inhibitor of liver NSMase-2 activity

To further substantiate the hypothesis that the decline in GSH content during aging is responsible for NSMase-2 activation, the ability of GSH to regulate NSMase activity in liver was investigated. First, we tested whether GSH can directly inhibit hepatocyte NSMase activity in vitro (Fig. 2A). It should be noted that the NSMase activity measured in these assays is a function of at least two genetically different enzymes, NSMase-1 and NSMase-2, with identical pH optima and Mg2+ dependence. To determine whether NSMase-2 in particular was inhibited by GSH, we also used hepatocytes overexpressing NSMase-2. As reported previously by Liu and Hannun (30) for MCF-7 cells, the exogenous addition of GSH to cell homogenates from young hepatocytes inhibits in a dose-dependent manner the endogenous NSMase activity (Fig. 2A, open circles). More importantly, the dose-dependence curve was shifted to the left in cells overexpressing NSMase-2 (Fig. 2A, closed circles), indicating that GSH addition inhibits the activity as a result of NSMase-2.

Fig. 2.

Effects of GSH on neutral sphingomyelinase (NSMase) activity. A: GSH inhibits NSMase in vitro. Hepatocytes from young (3–4 months) rats were infected with adenovirus encoding mouse NSMase-2 under doxycyclin-inducible promoter (AdNSMase-2), and the expression of NSMase-2 was induced with doxycycline (closed circles) or not induced (open circles). NSMase activity was measured in vitro in the presence of the indicated concentrations of GSH. Results are expressed as percentages of the activity in samples without GSH and are means ± SD (n = 3). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.005. B: GSH depletion leads to NSMase activation. Hepatocytes from young (3–4 months) rats were treated with the indicated concentrations of l-buthionine-S,R-sulfoximine (BSO) for 24 h. GSH levels were measured using the Bioxytech® GSH/GSSG-412™ assay kit, and NSMase activity was measured as described. GSH content is presented on the left scale (open circles) as nmol GSH/mg cellular protein; values are means ± SD (n = 3). * P < 0.01, ** P < 0.001, *** P < 0.0001. NSMase activity is shown on the right scale (closed circles) as percentages of the activity measured in samples not treated with BSO; values are means ± SD (n = 3). #P < 0.03, ##P < 0.001, ###P < 0.0001. C: Correlation between GSH levels and endogenous NSMase activity. Hepatocytes from young (3–4 months) rats were treated with the same concentrations of BSO for 24 h, and GSH content and NSMase activity were measured as described for B. NSMase activity is expressed as a function of cellular GSH levels. Each dot represents an individual sample, and the regression curve represents the Boltzmann sigmoid equation.

Next, we investigated whether GSH is an endogenous inhibitor of NSMase. Hepatocytes from young (3–4 months) rats were treated with BSO, a potent inhibitor of GSH biosynthesis. The addition of BSO at concentrations up to 500 μM had no effect on cell viability for 48 h after treatment (data not shown). As expected, the cellular content of GSH decreased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2B, open circles), whereas NSMase activity increased (Fig. 2B, closed circles). Interestingly, the initial decrease in GSH content observed at 100 μM BSO had very little effect on NSMase activity. However, as the GSH levels continued to decline further, NSMase activity increased sharply. To analyze this relationship further, the values for NSMase activity were replotted as a function of the measured GSH (Fig. 2C). Interpolation with different nonlinear regression models showed that the Boltzmann sigmoid curve offered the best fit for the experimental data (R2 = 0.8788, P = 0.1002), suggesting that GSH might inhibit NSMase in a cooperative manner. Alternatively, the biphasic dose response might indicate that reaching a threshold in GSH decline was required before NSMase activation occurred. The latter possibility is supported by the fact that BSO concentrations that resulted in GSH levels of <100 nmol/mg protein, which corresponds to the levels found in aged hepatocytes (Table 1), caused the sharp increase in NSMase activity.

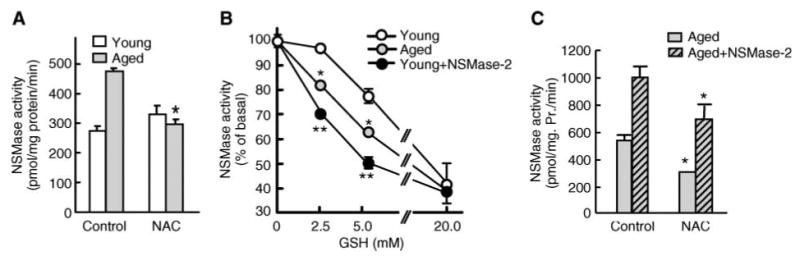

GSH depletion is responsible for the age-related upregulation of NSMase-2 activity in hepatocytes

To test directly whether the increase in NSMase activity during aging is attributable to GSH depletion, hepatocytes from young and aged rats were treated with NAC. The addition of NAC significantly decreased the activity of NSMase in aged hepatocytes to a level similar to that of young ones (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, NAC had no effect on hepatocytes from young animals. These results suggest that increased basal NSMase activity during aging might indeed be caused by the lower hepatic GSH content. In young hepatocytes, however, NSMase activity is constitutively inhibited by the intrinsically high GSH content; thus, it is not affected by further increases in cellular GSH content. To test directly whether the sensitivity of NSMase to GSH inhibition differs with age, NSMase activity was measured in detergent-free hepatocyte homogenates from young (Fig. 3B, open circles) and old (Fig. 3B, gray circles) animals in the presence of various concentrations of GSH. The dose-dependence curve for inhibition was indeed different for young and aged hepatocytes, and in the latter case it was shifted to the left, confirming that NSMase activity in aged hepatocytes is more sensitive to inhibition by GSH. Notably, the dose-dependence curve shift observed in aged hepatocytes was similar to that seen in young hepatocytes overexpressing NSMase-2 (Fig. 3B, closed circles).

Fig. 3.

Aging-associated activation of NSMase is caused by the depletion of hepatic GSH content. A: N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) supplementation decreases NSMase activity only in hepatocytes from aged animals. Hepatocytes from young (3–4 months) and aged (20–22 months) rats were cultured as described and treated with 20 mM NAC for 2 h before assessment of NSMase activity. Results are expressed as specific activity of NSMase (hydrolysis of picomoles of substrate per milligram of cellular protein per minute) and are means ± SD (n = 3). * P < 0.001. B: NSMase activity in aged hepatocytes is more sensitive to GSH inhibition than that of young hepatocytes. Hepatocytes from young (open circles) and aged (gray circles) rats, as well as young hepatocytes overexpressing NSMase-2 (closed circles), were cultured and harvested as described. NSMase activity was measured in vitro in the presence of the indicated concentrations of GSH. Results are expressed as percentages of the activity in respective samples without GSH and are means ± SD (n = 3). C: NAC decreases basal activity of the endogenous NSMase and the exogenous NSMase-2 in aged rat hepatocytes. Hepatocytes from aged (20–22 months) rats were infected with AdNSMase-2, and expression of NSMase-2 was either induced with doxycycline (striped bars) or not induced (gray bars). Cells were treated with 20 mM NAC for 2 h before NSMase activity measurements. Results are presented as specific activity of NSMase (hydrolysis of picomoles of substrate per milligram of cellular protein per minute) and are means ± SD (n = 6). * P < 0.01, ** P < 0.001.

To further confirm that NSMase-2 specifically is stimulated by GSH depletion during aging, induced and non-induced AdNSMase-2-infected hepatocytes from aged rats were supplemented with NAC. As expected, the addition of NAC led to a significant decrease in endogenous NSMase activity. Notably, the specific NSMase activity measured in cells overexpressing NSMase-2 also declined substantially (Fig. 3C). Together, these results indicate that the age-related increase in NSMase activity is associated with GSH depletion.

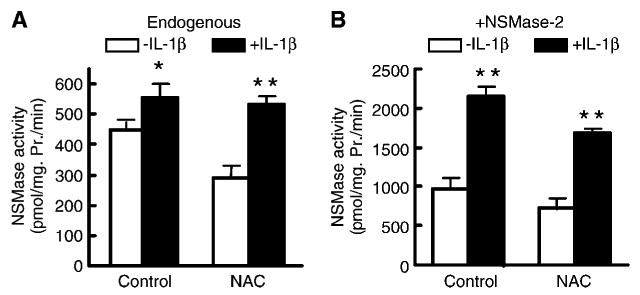

Aging and IL-1β stimulate NSMase-2 by different mechanisms

Because GSH depletion has been shown to mediate TNF-α-induced NSMase activation, it was of interest to determine whether IL-1β also activates NSMase-2 in a GSH-dependent manner. NAC pretreatment of aged hepatocytes suppressed basal NSMase activity but had no effect on the ability of IL-1β to stimulate either the endogenous NSMase (Fig. 4A) or the overexpressed NSMase-2 (Fig. 4B). This finding suggests that only aging-induced, and not IL-1β-induced, activation of NSMase is GSH-dependent.

Fig. 4.

IL-1β-induced activation of NSMase-2 is not GSH-dependent. A: IL-1β activates endogenous NSMase in the presence of NAC. Hepatocytes from aged (20–22 months) rats were pretreated with 20 mM NAC for 2 h before incubation with 2.5 ng/ml IL-1β for 30 min and subsequent NSMase activity measurements. Results are presented as specific activity of NSMase (hydrolysis of picomoles of substrate per milligram of cellular protein per minute) and are means ± SD (n = 6). B: IL-1β activates exogenous NSMase-2 in the presence of NAC. Hepatocytes from aged (20–22 months) rats were infected with AdNSMase-2, and the expression of NSMase-2 was induced with doxycycline. Cells were treated as described for Fig. 3A, and NSMase activity was measured. Results are presented as specific activity of NSMase (hydrolysis of picomoles of substrate per milligram of cellular protein per minute). Values are means ± SD (n = 6). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

GSH depletion leads to IL-1β hyperresponsiveness

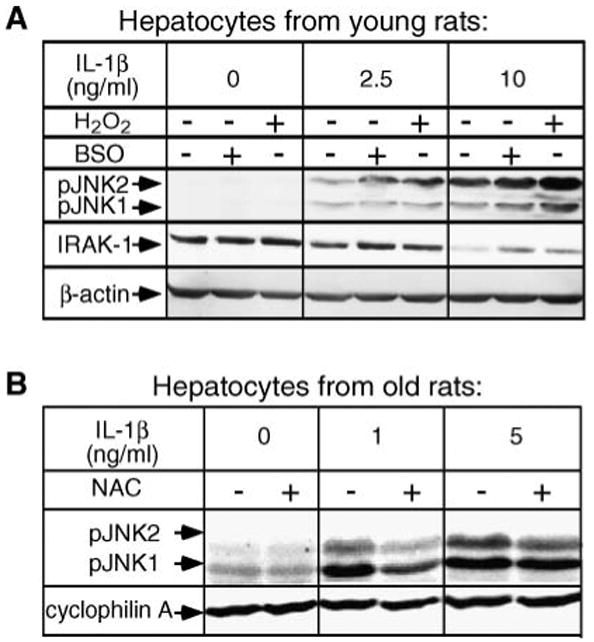

If depletion of GSH is responsible for the NSMase-2 activation during aging, then a decrease in cellular GSH content should be sufficient and required for the onset of IL-1β hyperresponsiveness. Vice versa, increases in GSH levels should reverse the aging phenotype of IL-1β hyperresponsiveness. To test this, GSH content in hepatocytes of young (3–4 months) animals was depleted using BSO. This treatment, as seen in Fig. 2B, decreases GSH and activates NSMase to levels typically found in aged animals. Importantly, upon IL-1β stimulation, the BSO-treated young hepatocytes exhibited more potent induction of JNK and attenuated degradation of IRAK-1 (Fig. 5A), very similar to the effect shown in Fig. 1A, B for aged hepatocytes. Similar results were obtained when cells were treated with H2O2, a potent ROS molecule that is neutralized via GSH peroxidase reaction and effectively decreases the levels of GSH. However, compared with the BSO treatments, the effects of H2O2 on JNK seemed more potent than those on IRAK-1. This was likely attributable to IRAK-1-independent (direct) effects of H2O2 on JNK. Next, hepatocytes from aged (20–22 months) rats were pretreated with NAC to increase the levels of endogenous GSH. NAC substantially diminished the magnitude of IL-1β-induced JNK phosphorylation (Fig. 5B), in agreement with the inhibition of NSMase activity shown in Fig. 3A. These results suggest that GSH depletion, just like NSMase-2 activation, is sufficient and required for the age-related IL-1β hyperresponsiveness.

Fig. 5.

GSH depletion is required and sufficient to induce hyperresponsiveness to IL-1β. A: GSH depletion induces hyperresponsiveness to IL-1β in hepatocytes from young rats. Hepatocytes from young (3–4 months) rats were pretreated with 400 μM BSO for 24 h or with 500 μM H2O2 for 15 min, then treated with the indicated concentrations of IL-1β for 30 min. IRAK-1 degradation and JNK phosphorylation were determined by Western blotting using antibodies against IRAK-1 and phospho-JNK1/2. β-Actin was used as a control for uniform loading. B: NAC supplementation attenuates the IL-1β hyperresponsiveness in hepatocytes from aged rats. Hepatocytes from aged (20–22 months) rats were pretreated with 20 mM NAC for 2 h before treatment with the indicated concentrations of IL-1β for 30 min. Phospho-JNK was visualized by Western blotting. Cyclophilin A was used as a control for uniform loading.

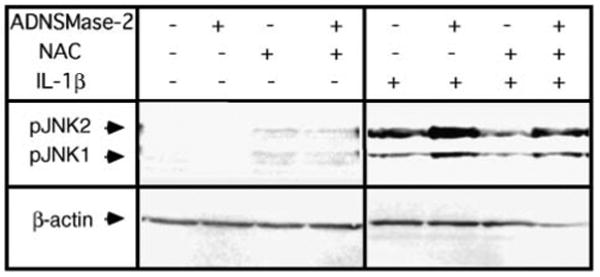

NSMase-2 acts downstream of GSH in the induction of IL-1β hyperresponsiveness

If NSMase-2 activation acts downstream of GSH, then overexpressing NSMase-2 in hepatocytes from aged rats supplemented with NAC should rescue the aging phenotype. To test this, hepatocytes from aged (20–22 months) rats were infected with AdNSMase-2 and cells were treated with NAC and IL-1β (Fig. 6). As shown earlier (Fig. 3C), NAC supplementation partially inhibits NSMase-2 activity, but the activity is still higher than that in aged NAC-treated hepatocytes that do not overexpress NSMase-2. Importantly, in IL-1β-treated cells overexpressing NSMase-2, the magnitude of JNK phosphorylation was higher regardless of whether the cells were also treated with NAC. This implies that in the pathway leading to IL-1β hyperresponsiveness, NSMase-2 acts downstream of GSH depletion, and its activation is sufficient to suppress the ability of NAC to restore normal IL-1β response in hepatocytes from aged rats.

Fig. 6.

NSMase-2 overexpression rescues the hyperresponsive phenotype suppressed by NAC. Hepatocytes from aged (20–22 months) rats were infected with AdNSMase-2, and expression of NSMase-2 was either induced with doxycycline or not induced. Cells were pretreated with 20 mM NAC for 2 h before treatment with 2.5 ng/ml IL-1β for 30 min. JNK phosphorylation was determined by Western blotting using antibodies against phospho-JNK1/2. β-Actin was used as a control for uniform loading.

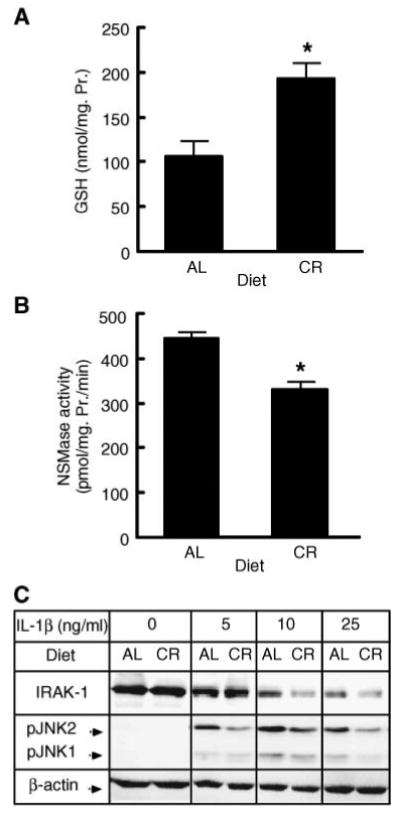

Calorie restriction attenuates the onset of age-related IL-1β hyperresponsiveness

Calorie-restricted animals live significantly longer than their ad libitum-fed littermates. Most importantly, the aging-associated sensitization to environmental oxidative damage is reduced in these animals, indicating the normal antioxidant capacity of the cells, including normal GSH levels (5). Therefore, calorie-restricted animals are an ideal model for testing the physiological significance of GSH depletion in the onset of IL-1β hyperresponsiveness. For this reason, hepatocytes from old (20 months) age-matched calorie-restricted or ad libitum-fed rats were isolated and their GSH content, NSMase activity, and responsiveness to IL-1β were assessed (Fig. 7). Aged calorie-restricted rats had a higher GSH content in their hepatocytes compared with aged ad libitum-fed animals (Fig. 7A). They also exhibited lower NSMase activity (Fig. 7B). Moreover, calorie restriction also reversed the hyperresponsive phenotype, as judged by increased IRAK-1 degradation and less potent JNK phosphorylation (Fig. 7C). These results indicate that both the increase in NSMase activity and the onset of IL-1β hyperresponsiveness result from changes that are intrinsic to the aging process.

Fig. 7.

Calorie restriction attenuates the age-related onset of IL-1β hyperresponsiveness. A: Effects of calorie restriction on GSH levels in hepatocytes. GSH levels in hepatocytes from aged (20 months) calorie-restricted (CR) or ad libitum-fed (AL) rats were measured using the Bioxytech® GSH/GSSG-412™ assay kit. Results are presented as nmol GSH/mg cellular protein and are means ± SD (n = 4). * P < 0.013. B: Effects of calorie restriction on NSMase activity in hepatocytes. NSMase activity in hepatocytes from aged (20 months) calorie-restricted (CR) or ad libitum-fed (AL) rats was measured as described. Results are presented as specific activity of NSMase (hydrolysis of picomoles of substrate per milligram of cellular protein per minute) and are means ± SD (n = 4). * P < 0.05. C: Effects of calorie restriction on IRAK-1 degradation and JNK phosphorylation. Hepatocytes from aged (20 months) calorie-restricted (CR) or ad libitum-fed (AL) rats were treated with the indicated concentrations of IL-1β for 30 min. IRAK-1 and phospho-JNK levels were determined by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as a control for uniform loading.

Discussion

Inflammation, a hallmark of the aging process, contributes to many age-related conditions, such as atherosclerosis and Alzheimer's disease. Previously, we showed that hepatocytes isolated from aged Fisher 344 rats are hyperresponsive to IL-1β stimulation, and increased basal NSMase-2 activity is responsible for this phenomenon (10). However, the exact mechanism by which NSMase-2 is activated with age remained unclear.

Oxidative stress is known to be a major factor leading to inflammation during aging. Therefore, the goal of this study was to test whether oxidative stress and, more specifically, cellular GSH content contributes to IL-1β hyperresponsiveness by regulating NSMase-2 activity. Previous studies have shown that GSH is a reversible inhibitor of NSMase activity (30, 31) and that the onset of oxidative stress in aging animals is accompanied by a net decrease of GSH in different organs. We used two different methods to measure GSH levels in primary hepatocytes and observed a dramatic age-dependent decline in GSH, consistent with the 40–60% decline reported by other investigators (44, 45). Apparently, this decline in GSH is responsible for the age-related NSMase-2 activation, because i) NAC supplementation led to a significant decrease in the endogenous NSMase activity of aged hepatocytes to a level typical for young hepatocytes, and ii) the addition of BSO to young hepatocytes decreased their GSH levels, causing sharp increases in NSMase activity.

The modulation of NSMase activity by GSH had been studied previously in the context of the regulation of TNF-α signaling and apoptosis (30, 31). The ability of GSH to affect the sensitivity of T47D/H3 breast cancer cells to doxorubicin has also been attributed to the inhibitory effect that GSH has on NSMase activity (46). A correlation between oxidative stress and NSMase activity has been found in long-lived rats on a vitamin Q10-enriched diet (47) and in astrocytes treated with vitamin E (48). The results presented here are the first to establish a direct link between the decrease in GSH content during the physiological process of aging, the activity of NSMase-2, and age-related IL-1β hyperresponsiveness.

GSH depletion seems to exert its effect on NSMase activity in a biphasic manner, consistent with the existence of a threshold for activation. Alternatively, it is possible that there is a large cellular pool of GSH that is not involved in NSMase regulation and that only changes in a specific GSH pool, possibly within the immediate surroundings of the enzyme, influence NSMase activity. Because the direct in vitro effect of GSH on NSMase-2 was also biphasic, the former possibility appears more likely. Interestingly, NSMase-1, an NSMase that is genetically distinct from NSMase-2 and has different subcellular localization and no known function in signaling, is sensitive to changes in the GSH/GSSG ratio but not to ex vivo treatment with BSO alone or to direct in vitro treatment with GSH (49). This may indicate that GSH specifically inhibits NSMase-2 but not NSMase-1, or alternatively, that these subtle differences are caused by different endogenous levels and/or pools of GSH in various cell types.

We also found that although the increase in NSMase activity during aging is apparently caused by GSH depletion, the IL-1β-induced NSMase activation is GSH-independent. This is consistent with the observation that IL-1β (unlike TNF-α) induces ROS production in the liver only modestly (50), without substantially altering liver GSH content.

According to the inflammation hypothesis of aging, increased ROS production during aging leads to the onset of a proinflammatory state by affecting two critical redox-sensitive molecules, JNK and NF-κB. A consequent increase in the basal circulating levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 is considered the principal mechanism for the onset of systemic inflammation during aging. However, the age-associated changes in the basal levels of proinflammatory cytokines measured in different animal species and humans are either very small or not statistically significant; thus, it is unclear whether they are sufficient to evoke a response in target tissues. Our observations suggest that in addition to the proposed direct induction of the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress may also potentiate the cellular responses to IL-1β via the depletion of cellular GSH content. As a result, even small increases in the levels of IL-1β in the circulation may be clinically relevant for aged individuals.

It has been reported that basal JNK phosphorylation in intact livers increases with aging (51). However, we could not confirm these observations in primary hepatocyte cultures. Basal JNK phosphorylation was undetectable in cells from both young and aged animals, despite a significant difference in their GSH content. Similarly, JNK phosphorylation was not visibly stimulated by either H2O2-or BSO-induced oxidative stress in the absence of IL-1β stimulation. This suggests that at least in hepatocytes, oxidative stress alone is not sufficient to induce JNK activation. The decrease in GSH content, however, was sufficient to potentiate JNK phosphorylation in the presence of an external stimulus such as IL-1β. Together, these observations suggest that the induction of basal JNK phosphorylation in liver tissue during aging may require the combined effects of intrinsic (increased cellular oxidative stress) and extrinsic (changes in the levels of various systemic stimuli) factors.

Calorie restriction extends the lifespan in many species, from yeast to mammals. Animals subjected to calorie-restricted diets at early maturity exhibit delayed aging in terms of their physiological functions and a marked decrease in the incidence of aging-related diseases. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is an overall decline in oxidative stress as a result of the attenuation of intracellular ROS generation and the maintenance of high antioxidative capacity in the calorie-restricted animals. Our findings that hepatocytes from aged, calorie-restricted rats, compared with those from age-matched ad libitum-fed rats, have attenuated IL-1β responsiveness resulting from higher GSH content and lower NSMase activity are in good agreement with this hypothesis. These observations also provide further support for the proposed role of GSH in the regulation of NSMase activity and IL-1β responsiveness. Moreover, these findings also indicate that the IL-1β response and NSMase activity are modulated in an age-specific manner in correlation with the lifespan of the organism.

In summary, by providing evidence that the age-related increase in NSMase activity is attributable to GSH depletion and that the GSH content modulates IRAK-1 stability and JNK phosphorylation through NSMase-2, this study delineates GSH as an important determinant of IL-1β response during aging and identifies NSMase-2 as a link between increased oxidative stress and the onset of inflammation during aging.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Aging Grants RO1 AG-019223 and R01 AG-026711 (to M.N.N-K.) and in part by a predoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association (to K.R.). The authors sincerely thank Mr. Alexander Karakashian for thoughtful reading and correcting of the manuscript, the Cardiovascular Research Discussion Group (University of Kentucky) for valuable comments, and Mr. James Begley for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- AdNSMase-2

adenovirus encoding mouse NSMase-2 under doxycyclin-inducible promoter

- BSO

l-buthionine-S,R-sulfoximine

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

- IL-1RI

interleukin-1β receptor

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- IRAK-1

interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-1

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine

- NBD-SM

6-N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino-sphingomyelin

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- NSMase-2

neutral sphingomyelinase-2

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TAK-1

transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase-1

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- TRAF-6

tumor necrosis factor-associated factor-6

References

- 1.Ballou SP, Lozanski FB, Hodder S, Rzewnicki DL, Mion LC, Sipe JD, Ford AB, Kushner I. Quantitative and qualitative alterations of acute-phase proteins in healthy elderly persons. Age Ageing. 1996;25:224–230. doi: 10.1093/ageing/25.3.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsieh CC, Rosenblatt JI, Papaconstantinou J. Age-associated changes in SAPK/JNK and p38 MAPK signaling in response to the generation of ROS by 3-nitropropionic acid. Mech Ageing Dev. 2003;124:733–746. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(03)00083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Supakar PC, Jung MH, Song CS, Chatterjee B, Roy AK. Nuclear factor kappa B functions as a negative regulator for the rat androgen receptor gene and NF-kappa B activity increases during the age-dependent desensitization of the liver. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:837–842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsieh CC, Xiong W, Xie Q, Rabek JP, Scott SG, An MR, Reisner PD, Kuninger DT, Papaconstantinou J. Effects of age on the posttranscriptional regulation of CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta isoform synthesis in control and LPS-treated livers. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1479–1494. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.6.1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung HY, Kim HJ, Kim JW, Yu BP. The inflammation hypothesis of aging: molecular modulation by calorie restriction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;928:327–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Iorio A, Ferrucci L, Sparvieri E, Cherubini A, Volpato S, Corsi A, Bonafe M, Franceschi C, Abate G, Paganelli R. Serum IL-1beta levels in health and disease: a population-based study. The InCHIANTI Study. Cytokine. 2003;22:198–205. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4666(03)00152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roubenoff R, Harris TB, Abad LW, Wilson PW, Dallal GE, Dinarello CA. Monocyte cytokine production in an elderly population: effect of age and inflammation. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53:M20–M26. doi: 10.1093/gerona/53a.1.m20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang Y, Di Pietro L, Feng Y, Wang X. Increased TNF-alpha and PGI(2), but not NO release from macrophages in 18-month-old rats. Mech Ageing Dev. 2000;114:79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(00)00090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu D, Marko M, Claycombe K, Paulson KE, Meydani SN. Ceramide-induced and age-associated increase in macrophage COX-2 expression is mediated through up-regulation of NF-kappa B activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10983–10992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutkute K, Karakashian A, Giltiay N, Dobierzewska A, Nikolova-Karakashian MN. Aging in rat causes hepatic hyperresponsiveness to interleukin 1beta which is mediated by neutral sphingomyelinase-2. Hepatology. 2007 doi: 10.1002/hep.21777. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wesche H, Henzel WJ, Shillinglaw W, Li S, Cao Z. MyD88: an adapter that recruits IRAK to the IL-1 receptor complex. Immunity. 1997;7:837–847. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80402-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao Z, Xiong J, Takeuchi M, Kurama T, Goeddel DV. TRAF6 is a signal transducer for interleukin-1. Nature. 1996;383:443–446. doi: 10.1038/383443a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang Z, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Qian Y, Matsumoto K, Li X. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor-associated kinase-dependent IL-1-induced signaling complexes phosphorylate TAK1 and TAB2 at the plasma membrane and activate TAK1 in the cytosol. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7158–7167. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.20.7158-7167.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Kishimoto K, Hiyama A, Inoue J, Cao Z, Matsumoto K. The kinase TAK1 can activate the NIK-I kappaB as well as the MAP kinase cascade in the IL-1 signalling pathway. Nature. 1999;398:252–256. doi: 10.1038/18465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamin TT, Miller DK. The interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase is degraded by proteasomes following its phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21540–21547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuschieri J, Gourlay D, Garcia I, Jelacic S, Maier RV. Implications of proteasome inhibition: an enhanced macrophage phenotype. Cell Immunol. 2004;227:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, Cousart S, Hu J, McCall CE. Characterization of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase in normal and endotoxin-tolerant cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23340–23345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001950200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adib-Conquy M, Cavaillon JM. Gamma interferon and granulocyte/monocyte colony-stimulating factor prevent endotoxin tolerance in human monocytes by promoting interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase expression and its association to MyD88 and not by modulating TLR4 expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27927–27934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200705200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karakashian AA, Giltiay NV, Smith GM, Nikolova-Karakashian MN. Expression of neutral sphingomyelinase-2 (NSMase-2) in primary rat hepatocytes modulates IL-beta-induced JNK activation. FASEB J. 2004;18:968–970. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0875fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchesini N, Luberto C, Hannun YA. Biochemical properties of mammalian neutral sphingomyelinase 2 and its role in sphingolipid metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13775–13783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212262200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petkova DH, Momchilova-Pankova AB, Markovska TT, Koumanov KS. Age-related changes in rat liver plasma membrane sphingomyelinase activity. Exp Gerontol. 1988;23:19–24. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(88)90016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lightle SA, Oakley JI, Nikolova-Karakashian MN. Activation of sphingolipid turnover and chronic generation of ceramide and sphingosine in liver during aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2000;120:111–125. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(00)00191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cutler RG, Kelly J, Storie K, Pedersen WA, Tammara A, Hatanpaa K, Troncoso JC, Mattson MP. Involvement of oxidative stress-induced abnormalities in ceramide and cholesterol metabolism in brain aging and Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2070–2075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305799101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Claycombe KJ, Wu D, Nikolova-Karakashian M, Palmer H, Beharka A, Paulson KE, Meydani SN. Ceramide mediates age-associated increase in macrophage cyclooxygenase-2 expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30784–30791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204463200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venable ME, Blobe GC, Obeid LM. Identification of a defect in the phospholipase D/diacylglycerol pathway in cellular senescence. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26040–26044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kraveka JM, Li L, Bielawski J, Obeid LM, Ogretmen B. Involvement of endogenous ceramide in the inhibition of telomerase activity and induction of morphologic differentiation in response to all-trans-retinoic acid in human neuroblastoma cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;419:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acharya U, Patel S, Koundakjian E, Nagashima K, Han X, Acharya JK. Modulating sphingolipid biosynthetic pathway rescues photoreceptor degeneration. Science. 2003;299:1740–1743. doi: 10.1126/science.1080549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D'Mello NP, Childress AM, Franklin DS, Kale SP, Pinswasdi C, Jazwinski SM. Cloning and characterization of LAG1, a longevity-assurance gene in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15451–15459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schorling S, Vallee B, Barz WP, Riezman H, Oesterhelt D. Lag1p and Lac1p are essential for the acyl-CoA-dependent ceramide synthase reaction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3417–3427. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.11.3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu B, Hannun YA. Inhibition of the neutral magnesium-dependent sphingomyelinase by glutathione. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16281–16287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu B, Andrieu-Abadie N, Levade T, Zhang P, Obeid LM, Hannun YA. Glutathione regulation of neutral sphingomyelinase in tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced cell death. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11313–11320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshimura S, Banno Y, Nakashima S, Hayashi K, Yamakawa H, Sawada M, Sakai N, Nozawa Y. Inhibition of neutral sphingomyelinase activation and ceramide formation by glutathione in hypoxic PC12 cell death. J Neurochem. 1999;73:675–683. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsyupko AN, Dudnik LB, Evstigneeva RP, Alessenko AV. Effects of reduced and oxidized glutathione on sphingomyelinase activity and contents of sphingomyelin and lipid peroxidation products in murine liver. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2001;66:1028–1034. doi: 10.1023/a:1012381928535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernardo K, Krut O, Wiegmann K, Kreder D, Micheli M, Schafer R, Sickman A, Schmidt WE, Schroder JM, Meyer HE, et al. Purification and characterization of a magnesium-dependent neutral sphingomyelinase from bovine brain. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7641–7647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen J, Nikolova-Karakashian M, Merrill AH, Jr, Morgan ET. Regulation of cytochrome P450 2C11 (CYP2C11) gene expression by interleukin-1, sphingomyelin hydrolysis, and ceramides in rat hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25233–25238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.25233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nikolova-Karakashian M, Morgan ET, Alexander C, Liotta DC, Merrill AH., Jr Bimodal regulation of ceramidase by interleukin-1beta. Implications for the regulation of cytochrome p450 2C11. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18718–18724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bligh E, Dyer W. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merrill AH, Jr, Wang E, Mullins RE, Jamison WC, Nimkar S, Liotta DC. Quantitation of free sphingosine in liver by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1988;171:373–381. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90500-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asmis R, Wang Y, Xu L, Kisgati M, Begley JG, Mieyal JJ. A novel thiol oxidation-based mechanism for adriamycin-induced cell injury in human macrophages. FASEB J. 2005;19:1866–1868. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2991fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palomero J, Galan AI, Munoz ME, Tunon MJ, Gonzalez-Gallego J, Jimenez R. Effects of aging on the susceptibility to the toxic effects of cyclosporin A in rats. Changes in liver glutathione and antioxidant enzymes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:836–845. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00471-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jung K, Henke W. Developmental changes of antioxidant enzymes in kidney and liver from rats. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20:613–617. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rebrin I, Kamzalov S, Sohal RS. Effects of age and caloric restriction on glutathione redox state in mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35:626–635. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00388-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rikans LE, Kosanke SD. Effect of aging on liver glutathione levels and hepatocellular injury from carbon tetrachloride, allyl alcohol or galactosamine. Drug Chem Toxicol. 1984;7:595–604. doi: 10.3109/01480548409042822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hagen TM, Vinarsky V, Wehr CM, Ames BN. (R)-Alpha-lipoic acid reverses the age-associated increase in susceptibility of hepatocytes to tert-butylhydroperoxide both in vitro and in vivo. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2000;2:473–483. doi: 10.1089/15230860050192251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vericel E, Narce M, Ulmann L, Poisson JP, Lagarde M. Age-related changes in antioxidant defence mechanisms and peroxidation in isolated hepatocytes from spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 1994;132:25–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00925671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gouaze V, Mirault ME, Carpentier S, Salvayre R, Levade T, Andrieu-Abadie N. Glutathione peroxidase-1 overexpression prevents ceramide production and partially inhibits apoptosis in doxorubicin-treated human breast carcinoma cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:488–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bello RI, Gomez-Diaz C, Buron MI, Alcain FJ, Navas P, Villalba JM. Enhanced anti-oxidant protection of liver membranes in long-lived rats fed on a coenzyme Q10-supplemented diet. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:694–706. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ayasolla K, Khan M, Singh AK, Singh I. Inflammatory mediator and beta-amyloid (25-35)-induced ceramide generation and iNOS expression are inhibited by vitamin E. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:325–338. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin SF, Sawai H, Villalba JM, Hannun YA. Redox regulation of neutral sphingomyelinase-1 activity in HEK293 cells through a GSH-dependent mechanism. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;459:295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lang CH, Nystrom GJ, Frost RA. Regulation of IGF binding protein-1 in Hep G2 cells by cytokines and reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G719–G727. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.3.G719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bose C, Bhuvaneswaran C, Udupa KB. Age-related alteration in hepatic acyl-CoA: cholesterol acyltransferase and its relation to LDL receptor and MAPK. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:740–751. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]