Abstract

Purpose

To quantitate bone marrow edema-like lesions (BMEL) and the radiologic properties of cartilage in knees with acute anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries using T1ρ MRI over a 1 year time period.

Methods

9 patients with ACL injuries were studied. MRI were acquired within 8 weeks of the injury, after which ACL reconstruction surgery was performed. Images were then acquired 0.5, 6, and 12 months following reconstructions. The volume and signal intensity of BMEL were quantified at baseline and follow up exams. T1ρ values were quantified in cartilage overlying the BMEL (OC) and compared to surrounding cartilage (SC) at all time-points.

Results

BMEL were most commonly found in the lateral tibia and lateral femoral condyle. Nearly 50% of BMEL resolved over 1-year. The T1ρ values of the OC in the lateral tibia, medial tibia, and medial femoral condyle were elevated compared to respective regions in SC at all time points, significant only in the lateral tibia (P < 0.05). The opposite results were found in the lateral femoral condyle. For the medial tibia and medial femoral condyle, none of the time periods were significantly different. The percent increase in T1ρ values of OC in the lateral tibia was significantly correlated to BMEL-volume (r = 0.74, P < 0.05). At 1-year, the OC in the lateral tibia, medial tibia, and medial femoral condyle showed increased T1ρ values despite improvement of BMEL.

Conclusions

In patients following ACL tear and reconstruction, (1) the cartilage overlying BMEL in the lateral tibia experiences persistent T1ρ signal change immediately after acute injuries and at 1-year follow up despite BMEL improvement. (2) The superficial layers of the overlying cartilage demonstrate greater matrix damage than the deep layers, and (3) the volume of the BMEL may predict the severity of the overlying matrix's damage in the lateral tibia. T1ρ is capable of quantitatively and noninvasively monitoring this damage and detecting early cartilage changes in the lateral tibia over time.

Level of Evidence

IV

Introduction

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of the most commonly injured ligaments in the knee with an incidence of 81 per 100,000 persons between the ages of 10 and 64(1). Patients with ACL-injured knees are at an increased risk of posttraumatic osteoarthritis(2-4). Over 40% of patients with ACL ruptures develop radiographic changes of osteoarthritis 10-20 years after the injury and, on average, 15-20 years earlier than those with primary osteoarthritis(5-8). This was initially attributed to additional traumatic and progressive deterioration of the joint as a result of mechanical instability and abnormal loading patterns(9-11). However, recent studies have shown that 50-60% of patients with functionally stable ACL-reconstructed knees continue to develop degenerative changes in the knee, suggesting an alternative etiology in the development of posttraumatic osteoarthritis (12, 13).

Bone bruises, or bone marrow edema-like lesions (BMEL), are present in up to 80% of ACL-ruptured knees(14, 15). These lesions are defined as areas of increased signal intensity on T2-weighted, fat-saturated magnetic resonance images (MRI)(16, 17). Histologically, chronic lesions are characterized by bone marrow necrosis and fibrosis, microtrabeculae fractures and sclerosis, and swelling of fat of cells(18). BMEL are thought to be a result from translational impact during ACL rupture, where the anterolateral femur impacts the posterolateral tibia(15, 19). Upon impact, it has been proposed that the cartilage overlying BMEL sustains irreversible injury, and subsequently, cartilage degeneration continues to occur even after ACL reconstruction(20-23). Despite the significant prevalence of BMEL with ACL ruptures, the natural history of and the causal relationship between these lesions and local posttraumatic osteoarthritis remains to be elucidated.

Analysis of BMEL in patients with knee injury has traditionally relied upon qualitative or semi-quantitative imaging studies(17, 24). Recent methods that manually or semi-automatically measure bone marrow edema-like lesion's volume are encouraging, as they provide potential for quantitative assessment of these lesions(17). Advanced MRI techniques have been developed to detect macromolecular changes within cartilage matrix at the early stages of osteoarthritis, and the imaging markers ideal for this purpose are those that are capable of probing proteoglycan loss, which is characteristic of early cartilage damage. Among them, T1ρ imaging is an attractive candidate relative to standard MRI because it probes the interactions between water molecules and the cartilage extracellular matrix, specifically proteoglycans (25-30). A change, specifically an increase, in T1ρ values represents damage to the extracellular matrix. Thus, the degree to which the T1ρ values change/increase is an indication of the severity of cartilage matrix injury. While both T1ρ and T2 values increase with the degree of osteoarthritis, two studies suggest that T1ρ is more sensitive than T2 for detecting early cartilage degeneration (31, 32).

The objective of this study was to quantitate the volume and signal intensity of BMEL as well as the radiologic characteristics of the associated cartilage in ACL-reconstructed knees following acute ACL tear using T1ρ MRI at 3 Tesla over a 1 year time period. We hypothesized that the cartilage overlying BMEL in acute ACL-injured knees will show significant abnormal T1ρ signal changes compared to normal knees, and BMELs will be a correlate to the that the quantitative characteristics of the severity of cartilage matrix injury at 1 year following ACL injury. Additionally, we hypothesize that while BMEL will improve after ACL injury, signal changes in the overlying cartilage will persist.

Methods

Subjects

All experiments were approved by the Committee on Human Research at our institution. All patients with ACL injuries were referred by one orthopaedic surgeon at our institution's Sports Medicine clinic. The inclusion criteria were clinically diagnosed acute complete ACL rupture using an increased anterior-posterior laxity scale (Lachman grade 2-3) and confirmation by MRI, willingness to have an ACL-reconstruction, and capability to undergo the standard pre- and post-injury/operative rehabilitation. The exclusion criteria include prior history of osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, previous injury and surgery on either knee, and repeated injuries to either knee during the follow-up period. In addition, patients who required surgical intervention for other injuries, including meniscal, collateral ligament, and posterior cruciate ligament tears, were excluded from the study.

9 patients (4 women and 5 men, mean age = 35.4 ± 6.0 years, age range = 27 – 45 years, number of patients = 2, 5, 2 for age ranging 20 – 30 year, 30 – 40 year, and 40 – 50 years, respectively; BMI = 23.1 ± 2.1 kg/m2) with acute ACL injuries who showed BMEL were studied. Patients were initially scanned within eight weeks of the injury, after which ACL tears were reconstructed. Subsequent scans were aquired at 2 weeks (n=9), 6 months (n=7), and 12 months (n=9) following ACL reconstructions.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MR data were acquired with a 3 Tesla GE Excite Signa MR scanner (General Electric Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) using a transmit/receive quadrature knee coil (Clinical MR Solutions, Brookfield, WI, USA). The imaging protocol to assess cartilage morphology included sagittal 3D water excitation high-resolution spoiled gradient-echo (SPGR) images (TR/TE = 15/6.7 ms, flip angle = 12°, field of view = 14 cm, matrix = 512 × 512, slice thickness = 1 mm, bandwidth = 31.25 kHz, NEX = 0.75) and sagittal T2-weighted fat-saturated fast spin-echo (FSE) images (TR/TE = 4300/51 ms, field of view = 14 cm, matrix size = 512 × 256 slice thickness = 2.5 mm, gap = 0.5 mm, echo train length = 9, receiver bandwidth = 31.25 kHz, number of excitations = 2). The high-resolution SPGR images were used to segment cartilage and the T2-weighted fat-saturated FSE images were used to evaluate and quantify BMEL.

Sagittal 3D T1ρ-weighted images were acquired based on spin-lock techniques and 3D spoiled gradient-echo image acquisition(33). The sagittal 3D T1ρ-weighted imaging sequence was composed of two parts: magnetization preparation based on spin-lock techniques to impart T1ρ contrast, and an elliptical-centered segmented 3D spoiled gradient-echo acquisition immediately after transient signal evolution. The duration of the spin-lock pulse was defined as time of spin-lock, and the strength of the spin-lock pulse was defined as spin-lock frequency. The number of D pulses after each T1ρ magnetization preparation was defined as views per segment. There was a relatively long time of recovery between each magnetization preparation to allow enough and equal recovery of the magnetization before each T1ρ preparation. The imaging parameters were: TR/TE = 9.3/3.7 ms; field of view = 14 cm, matrix size = 256 × 192, slice thickness = 3 mm, receiver bandwidth = 31.25 kHz, views per segment = 48, time of recovery = 1.5 seconds, time of spin-lock = 0, 10, 40, 80 ms, spin-lock frequency = 500 Hz.

MR Post-Processing

Measuring BMEL Volume and Signal Intensity

BMEL were segmented and quantified using an algorithm developed previously by our lab(34). Briefly, BMEL were segmented automatically using a threshold method. The threshold was determined by the mean and standard deviation of signal intensity of the normal appearing bone marrow (NBM.mean) in the same compartment. The signal intensity and volume of the automatically segmented BMEL were recorded, and subsequently the relative signal intensity was calculated using the following equation:

| (1) |

Regions of interest for BMEL were verified by a musculoskeletal radiologist.

Cartilage Processing

Cartilage Segmentation

Semi-automatic cartilage segmentation was performed on the sagittal SPGR images using proprietary software developed with Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) based on Bezier splines and edge detection(35). Four compartments were defined within the femoral-tibial joint: the lateral and medial femoral condyles and the lateral and medial tibias.

Determination of Cartilage Overlying and Surrounding BMEL

In order to determine the cartilage overlying and surrounding BMEL, the T2-weighted fat-saturated fast spin-echo images were aligned to the high-resolution spoiled gradient-echo images using the Visualization Tool Kit-Computational Imaging Sciences Group (VTK- CISG) Registration Toolkit(36). The 3D cartilage contour generated from the SPGR images was overlaid to the aligned FSE images from which BMEL were identified. 3D contours of the overlying and surrounding cartilage were then manually defined (Fig. 1). “Overlying cartilage” was defined as cartilage that was 3 mm or less from an underlying BMEL; and “surrounding cartilage” was defined as cartilage that was greater than 3 mm from the underlying BMEL (Fig. 1). The fast spin-echo images acquired at follow-up exams were registered to the baseline images using the VTK-CISG Registration Toolkit(36) . The boundary between the overlying cartilage and surrounding cartilage defined in baseline images was used to define the cartilage overlying and surrounding the initial BMEL in the follow up scans to evaluate longitudinally the macromolecular changes within the same initial cartilage regions of interest (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Representative cartilage overlying a bone marrow edema-like lesion (red) and the surrounding cartilage (blue) at baseline and 1 year in acute ACL-injured knees treated with ACL- reconstruction. Yellow contours: BMEL. “Overlying cartilage” was defined as cartilage that was 3 mm or less from an underlying BMEL; and “surrounding cartilage” was defined as cartilage that was greater than 3 mm from the underlying BMEL. Note that while the bone marrow edema-like lesion improves over 1 year, the same areas overlying the old bone bruise (red) are studied with T1ρ to evaluate for changes to the cartilage matrix. T2-FSE = T2-weighted fat-saturated fast spin-echo images. SPGR = 3D water excitation high-resolution spoiled gradient-echo images.

Quantification of T1ρ relaxation

T1ρ maps were reconstructed using a proprietary developed fitting algorithm. T1ρ-weighted image intensities obtained for different time of spin-lock were fitted pixel-by-pixel to the following equation:

| (2) |

Next, the reconstructed T1ρ maps were rigidly registered to the previously acquired high-resolution spoiled gradient-echo images using the VTK CISG Registration Toolkit(36) using the first time of spin-lock image to compute the transformation. The cartilage contours of the overlying cartilage and surrounding cartilage defined above were overlaid to the registered T1ρ maps. The T1ρ values for different layers of the overlying and surrounding cartilage were further calculated using a proprietary developed laminar analysis program developed with Matlab(37). Briefly, for each point in the bone-cartilage interface of the cartilage segmentations a vector normal to the interface and ending at the articular surface was computed. All the normal vectors were then sampled at 20 equally spaced points using bicubic interpolation. The mean of T1ρ values from points 1-10 and 11-20 were then calculated, and termed as the deep and superficial layers, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

The average volume, relative signal intensity, and standard deviation (SD) of BMEL and the mean and SD of T1ρ were calculated in the overlying and surrounding cartilage for all the subjects. For the respective variable, ANOVA with repeated measures were used to compare the means at different time points. If ANOVA indicated significant differences, a standard paired t-test was used to compare the means between each two time points. A paired t-test was used to compare the T1ρ values in the overlying cartilage to those in the surrounding cartilage in patients. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to evaluate the correlation between BMEL' quantitative characteristics and T1ρ values in the overlying cartilage. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

BMEL Prevalence, Longitudinal Quantitative Characteristics, and Resolution

At baseline scans, five out of the nine patients had BMEL located in multiple knee compartments – two patients contained lesions in 2 different compartments and 3 patients had lesions in 3 different compartments (Table 1). Overall, the majority of patients had BMELs in the lateral compartments of the knee; and lesions were more common in the lateral tibia than the lateral femoral condyle (Table 2). BMEL were uncommon in the medial compartments of the knee, as 2 patients each had one lesion in the medial femoral condyle and 3 patients each had one lesion in the medial tibia (Table 1). The lesions located in the lateral tibia were found to have the largest average volume, and those in the medial femoral condyle had the smallest average volume (Table 2). The BMEL with the highest and lowest relative signal intensities were found in the lateral femoral condyle and medial tibia, respectively (Table 2).

Table 1.

Study subjects and locations of bone marrow edema-like lesions.

| Study Subjects | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| BMEL Location |

LT | LT MFC |

LT | LFC LT MT |

LFC LT MT |

LFC | MFC | LFC LT MT |

LFC LT |

LT = lateral tibia; LFC = lateral femoral condyle; MT = medial tibia; MFC = medial femoral condyle.

Table 2.

BMEL prevalence and longitudinal volumes and relative signal intensities in the four compartments of ACL-reconstructed knees

| Compartment | N | Average Volume (cm3) / RI at Baseline |

Average Volume (cm3) / RI at 1 year |

|---|---|---|---|

| LT | 7 | 9.35 / 2.92 | 0.46 / 2.37 |

| LFC | 5 | 6.21 / 3.50 | 0.01 / 1.79 |

| MT | 3 | 2.94 / 1.59 | 0.61 / 0.48 |

| MFC | 2 | 1.82 / 3.47 | 0.15 / 0.75 |

LT = lateral tibia; LFC = lateral femoral condyle; MT = medial tibia; MFC = medial femoral condyle; N = number of patients, RI = Average intensity of BMEL relative to average intensity of normal bone marrow.

In all four compartments of the knee, the volume and relative signal intensities of BMEL were observed to decrease over time (Fig. 2A,B). A significant decrease in BMEL volume was found between the baseline scan and the 6- and 12-month time points in the lateral tibia (Fig. 2A, *p<0.05). It was found that the decrease in bone marrow edema-like lesion volume and signal intensity, as described herein, eventually resulted in normalization of the lesions (Fig. 2). Overall, 9 lesions were observed out of the initial 17 lesions at the 12-month time point (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Longitudinal quantitative measurements of BMEL' (A) volume and (B) relative signal intensity in the four knee compartments. Relative intensity is defined as the average intensity of BMEL relative to the average intensity of normal bone marrow. Note that over time, the volume and signal intensities of BMEL decrease in all four compartments of the knee. (C) Percentage of BMEL resolved at each time point in ACL-reconstructed knees following acute ACL tear. Of note is that nearly 50% of BMEL resolved over a 1-year period. LFC = lateral femoral condyle; MFC = medial femoral condyle; LT = lateral tibia; MT = medial tibia. (* denotes significance; p< 0.05).

BMEL-associated Cartilage Changes: T1ρ Analysis of Overlying and Surrounding Cartilage

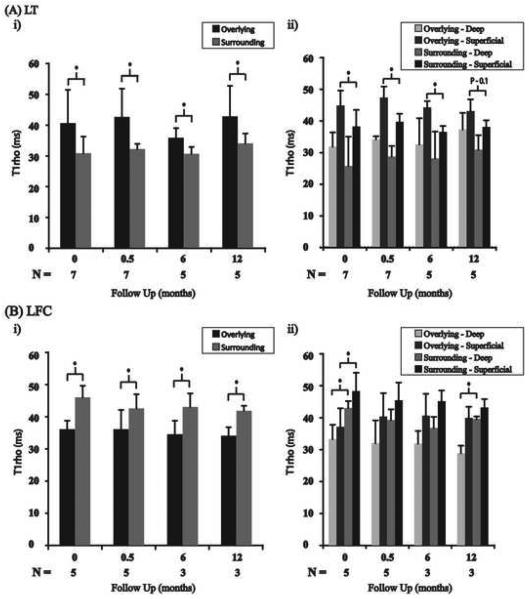

Next, we determined the T1ρ values for the full thickness and deep and superficial layers of the overlying cartilage and surrounding cartilage in all four compartments of the knee. In the lateral tibia it was found that the overlying cartilage had significantly higher T1ρ values than those of the surrounding cartilage at all time points (Fig. 3Ai, *p<0.05). Zonal analysis of the lateral tibia revealed significantly elevated T1ρ values in the superficial layer of the overlying cartilage relative to the superficial layer of the surrounding cartilage at baseline, 2 weeks, and 6 months, and a trend toward significance was observed at 12 months (Fig. 3Aii). Additionally, at all timepoints, T1ρ values were found to be higher in the deep layer of the overlying cartilage relative to the deep layer of the surrounding cartilage, although no significant differences were found (Fig. 3Aii). Figure 4 illustrates an example patient who showed BMEL in lateral tibia at baseline. T1ρ values in the cartilage overlying BMEL in the posterior lateral aspect of the tibia were significantly elevated compared to the surrounding cartilage (Figure 4, left). At 12-months follow up, T1ρ values of cartilage in the posterior lateral tibia remained elevated despite resolution of BMEL (Figure 4, right).

Figure 3.

Full-thickness and zonal analysis T1ρ values for the overlying and surrounding cartilage in the lateral tibia (A) and lateral femoral condyle (B). The overlying cartilage in the lateral tibia has significantly higher full-thickness T1ρ values than those of the surrounding cartilage at all time points (Ai). The deep and superficial layers of the overlying cartilage have elevated T1ρ values compared to their respective layers of the surrounding cartilage at all timepoints (Aii). LT = lateral tibia; LFC = lateral femoral condyle. (* denotes significance; p< 0.05).

Figure 4.

T1ρ maps of an ACL-injured knee at baseline (left) and 1-year follow up (right). At baseline, cartilage overlying BMEL showed significantly elevated T1ρ values compared to surrounding cartilage. At 1-year follow-up, despite resolution of lesions, cartilage overlying BMEL still showed elevated T1ρ values compared to the surrounding cartilage.

In the lateral femoral condyle the surrounding cartilage had significantly higher T1ρ values than the overlying cartilage at all time points (Fig. 3Bi, *p<0.05). The superficial layers of the overlying cartilage in the lateral femoral condyle were also found to have lower T1ρ values relative to the surrounding cartilage's superficial layer at all time points, although significance was found only at baseline (Fig. 3Bii, *p<0.05). This trend was observed for the deep layers in the lateral femoral condyle; however, only baseline and 12 month time points showed significant differences (Fig 3Bii, *p<0.05).

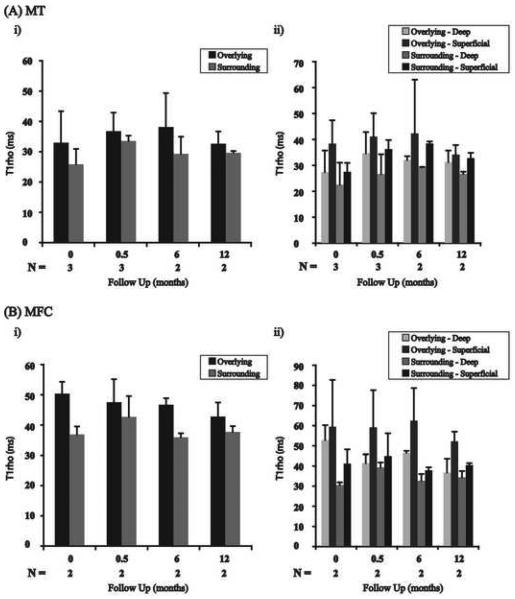

In the medial tibia the cartilage overlying BMEL had elevated T1ρ values relative to the surrounding cartilage at all time points (Fig. 5Ai). Zonal analysis in the medial tibia revealed elevated T1ρ values in the superficial layers of the overlying cartilage relative to the surrounding cartilage's superficial layer at all time points (Fig. 5Aii). This trend was also observed for the deep layers (Fig 5Aii). Statistical comparisons could not be accurately calculated for the medial tibia given only 3 total lesions in the compartment among all patients.

Figure 5.

Full-thickness and zonal analysis T1ρ values for the overlying and surrounding cartilage in the medial tibia (A) and medial femoral condyle (B). The overlying cartilage in the medial tibia and medial femoral condyle has higher full-thickness T1ρ values than those of the surrounding cartilage (A&Bi). The superficial and deep layers of the overlying cartilage have elevated T1ρ values compared to their respective layers in the surrounding cartilage at all timepoints (A&Bii). MT = medial tibia; MFC = medial femoral condyle. (* denotes significance; p< 0.05).

In the medial femoral condyle, the overlying cartilage had elevated full-thickness T1ρ values compared to the surrounding cartilage at all timepoints (Fig. 5Bi). The superficial layers of the overlying cartilage had higher T1ρ values compared to the superficial layers of the surrounding cartilage at all time points (Fig. 5Bii). Additionally, the deep layers of the overlying cartilage had higher T1ρ values compared to the deep layers of the surrounding cartilage at all time points (Fig. 5Bii). Statistical comparisons could not be accurately calculated for the medial femoral condyle given only 2 total lesions in the compartment among all patients.

A significant association was found between BMEL volume and the percent increase in T1ρ values of the overlying cartilage relative to surrounding cartilage in the lateral tibia (r = 0.74, p = 0.05, Table 3). No correlation was found between the volume and signal intensity of BMEL and the T1ρ values of the overlying cartilage in the lateral tibia (Table 3). Furthermore, no correlation was found between the volume and signal intensity of BMEL and the T1ρ values of the overlying cartilage, surrounding cartilage, or the percent increase in T1ρ values of the overlying cartilage relative to surrounding cartilage in the lateral femoral condyle (Table 3). Statistical comparisons could not be accurately calculated for the medial tibia and medial femoral condyle given few numbers of lesions in both compartments.

Table 3.

Correlation between lateral femoral condyle and lateral tibia BMEL characteristics and T1ρ values of overlying and surrounding cartilage.

| Overlying Cartilage | Surrounding Cartilage | % change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LFC | |||

| Volume | 0.06 | −0.21 | 0.29 |

| RI | −0.28 | −0.14 | −0.14 |

|

| |||

| LT | |||

| Volume | 0.90 | −0.33 | 0.74 |

| RI | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.10 |

LFC = lateral femoral condyle; LT = lateral tibia. RI = Average intensity of BMEL relative to average intensity of normal bone marrow. % change = [(overlying cartilage T1ρ values − surrunding cartilage T1ρ values) / overlying cartilage T1ρ values]. Note that the volume of BMEL in the lateral tibia is significantly correlated with the percent change between the overlying cartilage and surrounding cartilage T1ρ values. Also, medial tibia and medial femoral condyle comparisons were not statistically possible given few numbers of lesions in both compartments.

Discussion

In this study, radiologic changes of BMEL and cartilage were quantitatively evaluated in ACL-reconstructed knees following acute ACL tears longitudinally over a one-year period. A one-year study period was used because we wanted to evaluate relatively acute changes in cartilage composition following ACL-injury and determine if T1ρ was capable of detecting these early changes. Local cartilage organization was assessed by evaluating T1ρ values of the full thickness, deep and superficial layers of cartilage overlying and surrounding BMEL. In this study, we have demonstrated that T1ρ is capable of detecting cartilage changes in acute ACL-injured knees as early as one-year post-reconstruction. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first imaging study that quantitatively and longitudinally evaluates cartilage matrix composition in ACL-injured knees.

Similar to previous studies(15), we found the highest prevalence of BMEL in the lateral tibia and lateral femoral condyle in acutely injured knees. Lesions in the medial side of the knee were uncommon. While the acute quantitative characteristics of BMEL were unique to the individual knee compartments, the lesions were found to improve over 1 year in all four knee compartments, as indicated by a reduction in the lesions' volume and relative signal intensity. These observations are consistent with a recent MRI study of ACL-injured knees that reported that BMEL gradually decreased over the first year after ACL-injury(38); although the reports in the literature regarding the natural history of BMEL have been variable(15, 17, (39), (40)). Two earlier studies suggested that these lesions are not seen in patients who had MRIs acquired six weeks(16) or six months(39) post-injury. More recent work by Davies et al. suggested that BMEL may persist after 12-14 weeks post-injury using Short TI Inversion Recovery images(17). Our results in conjunction with these previous studies suggest that the initial trauma experienced by the trabeculae in each knee compartment may be different, but universally transient.

While BMEL improve over time, it is postulated that the cartilage overlying the lesions experiences irreversible damage during the initial injury(20-23). In a previous study, Johnson et al.(20) collected samples of cartilage in patients with acute ACL ruptures and observed biochemical variations and histologic changes (chondrocyte and matrix degeneration) in the cartilage overlying BMEL. In this study, we found that the full thickness of the overlying cartilage in the lateral tibia, medial tibia, and medial femoral condyle had elevated T1ρ values relative to the surrounding cartilage at baseline and subsequently at every follow up time point, with significant differences found only in the lateral tibia. These results suggest that the overlying cartilage in the lateral tibia, medial tibia, and medial femoral condyle do have damage despite resolution of BMEL. We also found that the superficial layer of the overlying cartilage in the lateral tibia, medial tibia, and medial femoral condyle had higher T1ρ values relative to the surrounding cartilage's superficial layer throughout the study period, and the differences were significant in the lateral tibia at baseline, 2 weeks, and 6 months. The deep layers of the overlying cartilage were also found to have greater T1ρ values than the surrounding cartilage's deep layer for the entire study period, although none of the differences were significant. While the authors did not measure cartilage thickness over the 1-year time period to assess cartilage volume loss, a recent study showed no significant difference in cartilage thickness after 7 years following ACL reconstruction (41), so the authors don't expect any change in morphology for this study's cohort.

In the lateral femoral condyle, the relationship between the overlying and surrounding cartilage was the reverse of the finding in the lateral tibia, medial tibia, and medial femoral condyle, as the surrounding cartilage had significantly higher T1ρ values than the overlying cartilage. This may be due to the observation that BMEL in the lateral femoral condyle were normally seen in the weight-bearing regions (cartilage overlying the anterior horn of the meniscus and the cartilage between the anterior and posterior horns of the meniscus), which are reported to have significantly lower T1ρ values than non-weight-bearing regions (most anterior and posterior regions of cartilage not protected by menisci in the femur)(32, 42). This spatial variation of T1ρ values in weight-bearing vs. non-weight bearing regions in femoral condyles can be attributed to potential different hydration and macromolecular structure caused by mechanical compression, as well as the potential dependence of T1ρ values on the orientation of the cartilage extracellular matrix with respect to the main magnetic field. Further experiments are needed to take spatial variation into account during comparison of T1ρ values between overlying cartilage and surrounding cartilage in the lateral femoral condyle.

BMEL are proposed to represent the trauma experienced by the joint surfaces at the moment of ACL injury(1, 43, 44). Frobell et al. report that knees that have suffered more severe injuries, i.e. with cortical depression fractures, have larger lesions(1). Additionally, two animal studies suggested that cell death occurs in the impacted cartilage, and that it spreads in depth and width with increasing stress forces(45, 46). Thus, size and macromolecular characteristics of BMEL may play a role in predicting cartilage matrix injury longitudinally. By comparing each patient's overlying cartilage T1ρ values to their surrounding cartilage values, we are able to assess the severity of each individual patient's injury more accurately. In this study, we found that the BMEL volume was correlated with the percent increase in T1ρ values of the overlying cartilage relative to the surrounding cartilage in the lateral tibia. No correlation was found between BMEL characteristics and the T1ρ values of the overlying cartilage in the lateral femoral condyle and statistical comparisons could not be calculated accurately for the medial tibia and medial femoral condyle given few numbers of lesions in both compartments. Therefore, these results suggest that the volume of a patient's bone marrow edema-like lesion in the lateral tibia may be used to predict the degree of damage to the overlying cartilage in the lateral tibia. The long-term goal would be to use these data to predict a patient's risk for developing secondary osteoarthritis. However, longer follow-up timepoints with arthritis measurements and evaluation of cartilage injury persistence and subsequent osteoarthritis development in all four knee compartments are warranted to accomplish this goal.

While many of the results described herein are promising, a number of limitations to this study exist. One limitation of this study is that the deep and superficial cartilage layers analyzed above do not correlate with the three physiological layers of cartilage: tangential, intermediate, and radiate. While the two layers were used instead of three because of limited resolution, it is possible that the deep and superficial layers analyzed also have limited resolution. Additional limitations of this study include the relatively short length of follow-up and the small number of patients evaluated, and no alignment data and arthroscopic evaluation were collected. One year following ACL-injury is a relatively short length of time, and it is possible that the observed aforementioned T1ρ signal changes may improve over time. Additionally, given the few number of patients and the infrequency of BMEL in the medial compartments of the knee relative to the lateral compartments, it is difficult to accurately evaluate the BMEL and associated cartilage in the medial tibia and medial femoral condyle. Another limitation of the study is that the T1ρ signal changes noted in this study were not correlated to standard MRI or to arthroscopic appearance of the cartilage. Thus, the results from this study should invite future clinical outcome studies with larger cohorts of patients and with longer follow up timepoints and include correlations between T1ρ values and arthroscopic cartilage measurements.

Conclusions

In patients following ACL tear and reconstruction, (1) the cartilage overlying BMEL in the lateral tibia experiences persistent T1ρ signal change immediately after acute injuries and at 1-year follow up despite BMEL improvement. (2) The superficial layers of the overlying cartilage demonstrate greater matrix damage than the deep layers, and (3) the volume of the BMEL may predict the severity of the overlying matrix's damage in the lateral tibia. T1ρ is capable of quantitatively and noninvasively monitoring this damage and detecting early cartilage changes in the lateral tibia over time.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Eric Han from Global Applied Science Laboratory, GE Healthcare for his help with pulse sequence development, and Dr. Jian Zhao for identifying BMEL.

Sources of Support: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants K25 AR053633 and RO1 AR46905, and the Aircast Foundation. A.A. Theologis is a medical student at UCSF who was funded by the UCSF Student Research Summer Fellowship and the Orthopaedic Research and Education Foundation Medical Student Summer Orthopaedic Research Fellowship.

One or more of the researchers or an affiliated institute has received (or agreed to receive) from a commercial entity something of value (exceeding the equivalent of US$500) related in any way to this manuscript or research. __N/A__.

Research was performed at _N/A_ (if different from affiliation of any of the authors).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Frobell RB, Roos HP, Roos EM, Hellio Le Graverand MP, Buck R, Tamez-Pena J, et al. The acutely ACL injured knee assessed by MRI: are large volume traumatic bone marrow lesions a sign of severe compression injury? Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008 Jul;16(7):829–36. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feagin JA., Jr. The syndrome of the torn anterior cruciate ligament. Orthop Clin North Am. 1979 Jan;10(1):81–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lohmander LS, Ostenberg A, Englund M, Roos H. High prevalence of knee osteoarthritis, pain, and functional limitations in female soccer players twelve years after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Oct;50(10):3145–52. doi: 10.1002/art.20589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright V. Post-traumatic osteoarthritis--a medico-legal minefield. Br J Rheumatol. 1990 Dec;29(6):474–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/29.6.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks PH, Donaldson ML. Inflammatory cytokine profiles associated with chondral damage in the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. Arthroscopy. 2005 Nov;21(11):1342–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawkins RJ, Misamore GW, Merritt TR. Followup of the acute nonoperated isolated anterior cruciate ligament tear. Am J Sports Med. 1986 May-Jun;14(3):205–10. doi: 10.1177/036354658601400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noyes FR, Mooar PA, Matthews DS, Butler DL. The symptomatic anterior cruciate-deficient knee. Part I: the long-term functional disability in athletically active individuals. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983 Feb;65(2):154–62. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198365020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roos H, Adalberth T, Dahlberg L, Lohmander LS. Osteoarthritis of the knee after injury to the anterior cruciate ligament or meniscus: the influence of time and age. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1995 Dec;3(4):261–7. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(05)80017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrack RL, Bruckner JD, Kneisl J, Inman WS, Alexander AH. The outcome of nonoperatively treated complete tears of the anterior cruciate ligament in active young adults. Clinical Orthop Relat Res. 1990 Oct;(259):192–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noyes FR, McGinniss GH, Mooar LA. Functional disability in the anterior cruciate insufficient knee syndrome. Review of knee rating systems and projected risk factors in determining treatment. Sports Med. 1984 Jul-Aug;1(4):278–302. doi: 10.2165/00007256-198401040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDaniel WJ, Jr., Dameron TB., Jr. Untreated ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament. A follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980 Jul;62(5):696–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferretti A, Conteduca F, De Carli A, Fontana M, Mariani PP. Osteoarthritis of the knee after ACL reconstruction. Int Ortho. 1991;15(4):367–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00186881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniel DM, Stone ML, Dobson BE, Fithian DC, Rossman DJ, Kaufman KR. Fate of the ACL-injured patient. A prospective outcome study. Am J Sports Med. 1994 Sep-Oct;22(5):632–44. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faber KJ, Dill JR, Amendola A, Thain L, Spouge A, Fowler PJ. Occult osteochondral lesions after anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Six-year magnetic resonance imaging follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 1999 Jul-Aug;27(4):489–94. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270041301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costa-Paz M, Muscolo DL, Ayerza M, Makino A, Aponte-Tinao L. Magnetic resonance imaging follow-up study of bone bruises associated with anterior cruciate ligament ruptures. Arthroscopy. 2001 May;17(5):445–9. doi: 10.1053/jars.2001.23581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graf BK, Cook DA, De Smet AA, Keene JS. “Bone bruises” on magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1993 Mar-Apr;21(2):220–3. doi: 10.1177/036354659302100210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies NH, Niall D, King LJ, Lavelle J, Healy JC. Magnetic resonance imaging of bone bruising in the acutely injured knee--short-term outcome. Clin Radiol. 2004 May;59(5):439–45. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zanetti M, Bruder E, Romero J, Hodler J. Bone marrow edema pattern in osteoarthritic knees: correlation between MR imaging and histologic findings. Radiology. 2000 Jun;215(3):835–40. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.3.r00jn05835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Speer KP, Spritzer CE, Bassett FH, 3rd, Feagin JA, Jr., Garrett WE., Jr. Osseous injury associated with acute tears of the anterior cruciate ligament. Am J Sports Med. 1992 Jul-Aug;20(4):382–9. doi: 10.1177/036354659202000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson DL, Urban WP, Jr., Caborn DN, Vanarthos WJ, Carlson CS. Articular cartilage changes seen with magnetic resonance imaging-detected bone bruises associated with acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Am J Sports Med. 1998 May-Jun;26(3):409–14. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260031101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lahm A, Uhl M, Erggelet C, Haberstroh J, Mrosek E. Articular cartilage degeneration after acute subchondral bone damage: an experimental study in dogs with histopathological grading. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004 Dec;75(6):762–7. doi: 10.1080/00016470410004166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis JL, Deloria LB, Oyen-Tiesma M, Thompson RC, Jr., Ericson M, Oegema TR., Jr. Cell death after cartilage impact occurs around matrix cracks. J Orthop Res. 2003 Sep;21(5):881–7. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin JA, Brown T, Heiner A, Buckwalter JA. Post-traumatic osteoarthritis: the role of accelerated chondrocyte senescence. Biorheology. 2004;41(3-4):479–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felson DT, Chaisson CE, Hill CL, Totterman SM, Gale ME, Skinner KM, et al. The association of bone marrow lesions with pain in knee osteoarthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2001 Apr 3;134(7):541–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-7-200104030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dijkgraaf LC, Liem RS, de Bont LG. Temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis and crystal deposition diseases: a study of crystals in synovial fluid lavages in osteoarthritic temporomandibular joints. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998 Aug;27(4):268–73. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80509-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redfield AG. Nuclear Spin Thermodynamics in the Rotating Frame. Science. 1969 May 30;164(3883):1015–23. doi: 10.1126/science.164.3883.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makela HI, Grohn OH, Kettunen MI, Kauppinen RA. Proton exchange as a relaxation mechanism for T1 in the rotating frame in native and immobilized protein solutions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001 Dec 14;289(4):813–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duvvuri U, Reddy R, Patel SD, Kaufman JH, Kneeland JB, Leigh JS. T1rho-relaxation in articular cartilage: effects of enzymatic degradation. Magn Reson Med. 1997 Dec;38(6):863–7. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910380602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akella SV, Regatte RR, Gougoutas AJ, Borthakur A, Shapiro EM, Kneeland JB, et al. Proteoglycan-induced changes in T1rho-relaxation of articular cartilage at 4T. Magn Reson Med. 2001 Sep;46(3):419–23. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menezes NM, Gray ML, Hartke JR, Burstein D. T2 and T1rho MRI in articular cartilage systems. Magn Reson Med. 2004 Mar;51(3):503–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Regatte RR, Akella SV, Lonner JH, Kneeland JB, Reddy R. T1rho relaxation mapping in human osteoarthritis (OA) cartilage: comparison of T1rho with T2. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006 Apr;23(4):547–53. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X, Han ET, Ma CB, Link TM, Newitt DC, Majumdar S. In vivo 3T spiral imaging based multi-slice T(1rho) mapping of knee cartilage in osteoarthritis. Magn Reson Med. 2005 Oct;54(4):929–36. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li X, Han ET, Busse RF, Majumdar S. In vivo T(1rho) mapping in cartilage using 3D magnetization-prepared angle-modulated partitioned k-space spoiled gradient echo snapshots (3D MAPSS) Magn Reson Med. 2008 Feb;59(2):298–307. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li X, Ma BC, Bolbos RI, Stahl R, Lozano J, Zuo J, et al. Quantitative assessment of bone marrow edema-like lesion and overlying cartilage in knees with osteoarthritis and anterior cruciate ligament tear using MR imaging and spectroscopic imaging at 3 Tesla. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008 Aug;28(2):453–61. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carballido-Gamio J, Bauer J, Lee KY, Krause S, Majumdar S. Combined image processing techniques for characterization of MRI cartilage of the knee. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2005;3:3043–6. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2005.1617116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rueckert D, Sonoda LI, Hayes C, Hill DL, Leach MO, Hawkes DJ. Nonrigid registration using free-form deformations: application to breast MR images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1999 Aug;18(8):712–21. doi: 10.1109/42.796284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carballido-Gamio J, Link TM, Majumdar S. New techniques for cartilage magnetic resonance imaging relaxation time analysis: texture analysis of flattened cartilage and localized intra- and inter-subject comparisons. Magn Reson Med. 2008 Jun;59(6):1472–7. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frobell RB, Le Graverand MP, Buck R, Roos EM, Roos HP, Tamez-Pena J, et al. The acutely ACL injured knee assessed by MRI: changes in joint fluid, bone marrow lesions, and cartilage during the first year. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009 Feb;17(2):161–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dimond PM, Fadale PD, Hulstyn MJ, Tung GA, Greisberg J. A comparison of MRI findings in patients with acute and chronic ACL tears. Am J Knee Surg. 1998 Summer;11(3):153–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bretlau T, Tuxoe J, Larsen L, Jorgensen U, Thomsen HS, Lausten GS. Bone bruise in the acutely injured knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2002 Mar;10(2):96–101. doi: 10.1007/s00167-001-0272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andreisek G, White LM, Sussman MS, Kunz M, Hurtig M, Weller I, et al. Quantitative MR imaging evaluation of the cartilage thickness and subchondral bone area in patients with ACL-reconstructions 7 years after surgery. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009 Jul;17(7):871–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Regatte RR, Akella SV, Wheaton AJ, Lech G, Borthakur A, Kneeland JB, et al. 3D-T1rho-relaxation mapping of articular cartilage: in vivo assessment of early degenerative changes in symptomatic osteoarthritic subjects. Acad Radiol. 2004 Jul;11(7):741–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2004.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanders TG, Medynski MA, Feller JF, Lawhorn KW. Bone contusion patterns of the knee at MR imaging: footprint of the mechanism of injury. Radiographics. 2000 Oct;20(Spec No):S135–51. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.suppl_1.g00oc19s135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu JS, Cook PA. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the knee: a pattern approach for evaluating bone marrow edema. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1996 Sep;37(4):261–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Milentijevic D, Rubel I, Liew A, Helfet D, PA T. An in vivo rabbit model for cartilage trauma: a preliminary study of the influence of impact stress magnitude on chondrocyte death and matrix damage. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(7):466–73. doi: 10.1097/01.bot.0000162768.83772.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ewers B, Jayaraman V, Banglmaier R, Haut R. Rate of blunt impact loading affects changes in retropatellar cartilage and underlying bone in the rabbit patella. J Biomech. 2002;35(6):747–55. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]