Abstract

Polymer-drug conjugates have gained significant attention as pro-drugs releasing an active substance as a result of enzymatic hydrolysis in physiological environment. In this study, a conjugate of 3-hydroxybutyric acid oligomers with a carboxylic acid group-bearing model drug (ibuprofen) was evaluated in vivo as a potential pro-drug for parenteral administration. Two different formulations, an oily solution and an o/w emulsion were prepared and administered intramuscularly (IM) to rabbits in a dose corresponding to 40 mg of ibuprofen/kilogramme. The concentration of ibuprofen in blood plasma was analysed by HPLC, following solid–phase extraction and using indometacin as internal standard (detection limit, 0.05 μg/ml). No significant differences in the pharmacokinetic parameters (C max, T max, AUC) were observed between the two tested formulations of the 3-hydroxybutyric acid conjugate. In comparison to the non-conjugated drug in oily solution, the relative bioavailability of ibuprofen conjugates from oily solution, and o/w emulsion was reduced to 17% and 10%, respectively. The 3-hydroxybutyric acid formulations released the active substance over a significantly extended period of time with ibuprofen still being detectable 24 h post-injection, whereas the free compound was almost completely eliminated as early as 6 h after administration. The conjugates remained in a muscle tissue for a prolonged time and can hence be considered as sustained release systems for carboxylic acid derivatives.

Key words: drug conjugates, ibuprofen, oligo(3-hydroxybutyrates), pharmacokinetics, pro-drugs

Along with aqueous suspensions, oily solutions, microspheres and implants, conjugates of drug substances with biocompatible and biodegradable polymers have been widely investigated for drug delivery applications (1,2). In contrast to technologies based on drug incorporation into the polymer matrix, conjugation to polymers significantly changes not only the pharmacokinetic properties of the drug, but also its chemical and physicochemical characteristics, including, e.g., solubility, stability and reactivity. Some of these conjugates, mainly with polyethylene glycols (PEG), have been approved and introduced into the clinic as safe and effective alternative to the parent drugs (1). Alternatives to PEG include polysaccharides (e.g., dextrans), vinyl polymers, poly amino acids and dendrimers (3). Current research in the field of biopolymers and biomaterials is focused on the development of novel polymers which are characterised by well-established metabolism route, demonstrate absence of toxicity and improve the pharmacokinetic properties of drugs, mainly by extending their half-life time, enhancing their solubility, reducing immunological reactions as well as fast elimination by enzymatic degradation (4).

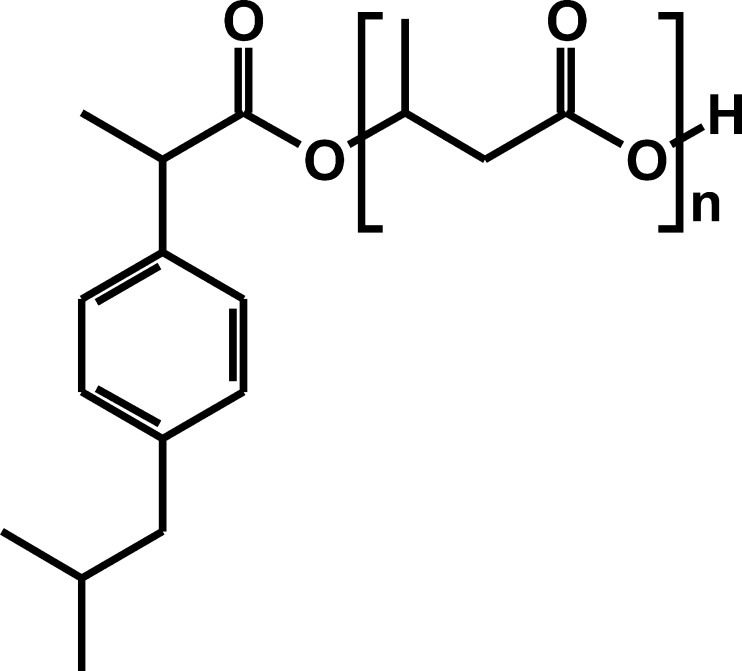

A novel approach for drug conjugation are oligomers of 3-hydroxybutyric acid (OHB) (5) which are synthesised by a number of microorganisms and can also be found in animal cells (6). Conjugates of carboxylic acid group-bearing non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) with OHB have recently been developed and characterised at the Centre of Polymer and Carbon Materials of Polish Academy of Sciences. It was reported that these conjugates are biocompatible and show high stability in aqueous solutions of pH 6.0–8.0 (7–9). Ibuprofen–OHB (Fig. 1) is a semi-solid substance with good solubility in organic solvents including oil (vegetable oils and Miglyol). It also marked resistance against hydrolytic enzymes (e.g., pancreatin) (9), however, no data on the conjugate's pharmacokinetics following parenteral administration has been available.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of the conjugate of ibuprofen with oligomers of 3-hydroxybutyric acid (n = 3–7)

In the present study we discuss the in vivo pharmacokinetics of ibuprofen–OHB after IM injection into rabbits from two different formulations, an oily solution and an o/w emulsion. We also report on the development of a high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method, preceded by SPE that was developed to analyse ibuprofen concentrations in the collected plasma samples.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Racemic ibuprofen (IB, Shasun, Chennai, India) was kindly donated by Polfa Kutno (Kutno, Poland) and indometacin (IND) was a gift from Jelfa (Jelenia Gora, Poland). Ibuprofen–OHB (M.W. 570 Da) containing approximately 2.5% (w/w) of non-conjugated IB was provided by the Centre of Polymer and Carbon Materials (Zabrze, Poland). Synthesis and analytical methods confirming purity, structure and molecular weight of the conjugate have been described elsewhere (9,10).

Acetonitrile (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and methanol (POCh, Gliwice, Poland) were of HPLC grade. Reagents for preparation of buffered solutions were also purchased from POCh. For drug formulations, Miglyol 812 (medium-chain triglycerides, Caesar and Loretz, Hilden, Germany), 86% (w/w) glycerol (Laboratorium Galenowe, Olsztyn, Poland) and Tween 80 (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) were used.

Instrumentation and Chromatographic Conditions

The HPLC system (Merck Hitachi, Darmstadt, Germany) consisted of an isocratic HPLC pump (L-7100), autosampler (L-7200), UV–vis detector (L-7420) and integrator (D-7000). As stationary phase a LiChrospher 100 RP-18 column (5 μm, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was used and the mobile phase was a mixture of 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and acetonitrile 70:30 (v/v). Flow rate was set to 1 ml/min, and detection was performed at 220 nm.

Standard Solutions and Sample Preparation

For calibration, solutions of IB (5, 12.5, 25, 50, 125, 500 and 1,250 μg/ml) and a solution of an internal standard IND (25 μg/ml) in methanol were used. Twenty microlitres of IB solution and 20 μl of the internal standard solution were added to 500 μl of blood plasma and vortexed for 10 s. Then, 100 μl of a 2% (w/w) solution of phosphoric acid and 600 μl of 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) were added, and the sample was vortexed again for 30 s. SPE columns (Strata-X 33 μm, Phenomenex, Torrance, USA) were initially washed with 1 ml of methanol followed by 1 ml of water according to manufacturer's directions (11). The samples were applied to the SPE columns and allowed to pass through without vacuum being applied. The columns were then washed with 700 μl of 5% (v/v) methanol in water. A vacuum was applied for 1 min to remove residual solvents. The elution was carried out using 1 ml of methanol. Collected solutions were centrifuged (3,000×g) and 950 μl were transferred to HPLC vials and the solvent was allowed to evaporate at 37°C under a gentle stream of air. The residue was then dissolved in 200 μl of methanol, and 20 μl were injected into the HPLC system.

Validation

Specificity of the method was determined at 220 nm by comparing the chromatograms after extraction of blank plasma and plasma spiked with IB (1 μg/ml) and IND (1 μg/ml). Linearity was tested by extraction and injection of nine sets of IB standard solutions in the concentration range 0.2–50 μg/ml. Precision was calculated at different concentrations—0.2, 5 and 20 μg/ml. Repeatability and reproducibility were calculated from the chromatograms of the same samples injected at different time points during one day (n = 3) or on three different days, respectively. Accuracy was calculated by applying the test procedure four times for three different IB concentrations (0.5, 2 and 5 μg/ml). Recovery rates were determined by comparing extracted spiked plasma samples with non-extracted solutions of standards in methanol (IB 1.25, 5 and 12.5 μg/ml). Limits of detection and quantification were also determined.

Drug Formulations

For parenteral administration of ibuprofen–OHB, a 25% (w/w) oily solution in Miglyol 812 and a 10% o/w emulsion (20% of oily phase) were prepared. The oily solution was obtained by dissolving ibuprofen–OHB in Miglyol at 60°C, followed by sterilisation through filtration (0.2 μm cellulose acetate filters). The emulsion containing ibuprofen–OHB, polysorbate 80 (2% w/w), glycerol (2.8% w/w), Miglyol 812 and water was prepared by high-speed homogenisation with an Ultra-Turrax T-25 (Janke and Kunkel, Staufen, Germany). Sterilisation of the emulsion formulation was performed by autoclaving (121°C, 15 min). An oily solution of non-conjugated IB (5% w/w) in Miglyol 812 was prepared as control and also sterilised by filtration as described above. No adverse effects of the thermal sterilisation on the emulsion stability were observed (9). Parameters investigated were pH, droplet size and ibuprofen–OHB concentration. All formulations were prepared at most 5 days prior to the start of the in vivo experiments, however stability of the formulations at 5 ± 2°C was investigated within 90 days after preparation (9).

Pharmacokinetics of Ibuprofen after Ibuprofen-OHB Administration in Rabbits

The animal experiments were designed to follow guidelines of the National Ethics Committee. The application was reviewed and approved by the 4th Local Ethics Committee in Warsaw (Permission No 25/2007). Eighteen adult rabbits (less than 1 year old, nine males and nine females) with body weights of 2.73 ± 0.32 kg were used. The animals were purchased from Hodowla Krolikow Rasowych (Wielichowo, Poland) and left to acclimatise for 1 week in the animal facility, prior to the start of the study. The animals were fed with standard rodent chow and had unrestricted access to fresh water. The study was supervised and assisted by a qualified veterinary surgeon and preceded accordingly to the application approved.

The animals were divided into three groups of six (males and females) and each group received one of the investigated formulations by injection into the musculus semimembranosus. Ibuprofen in oily solution was administered at doses of 25 mg/kg and ibuprofen–OHB in oil or in emulsion–at doses of 120 mg/kg (corresponding to 40 mg/kg of IB). The total injection volume, depending on the formulation, was between 1.1–3.5 ml. One-millilitre blood samples were collected in heparinised plastic tubes (Medlab Products, Raszyn, Poland) from the marginal ear vein prior to drug administration and at 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h after injection. Samples were centrifuged at room temperature (15 min, 3,000×g) and the plasma was separated and stored at −20°C until further analysis. After addition of 20 μl of the internal standard (IND, 25 μg/ml) to 500 μl of the plasma, samples were acidified, diluted with 600 μl phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) and analysed as described above.

Data Analysis

The calibration curves were calculated by linear regression of the IB/IND peak area ratio versus IB concentration. The AUC0-24h (for IB formulation) or AUC0-48h (for ibuprofen-OHB formulations) was calculated using linear trapezoidal rules. Statistical analysis was performed using Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance. Individual differences between the formulations were identified by Dunn's post hoc test or by Mann–Whitney rank sum test. A significance level of p < 0.05 denoted significance in all cases.

Relative bioavailability (EBA) was calculated using Eq. (1).

|

1 |

where AUC is area under curve and D is a dose of ibuprofen–OHB or IB.

Results

Analytical Method

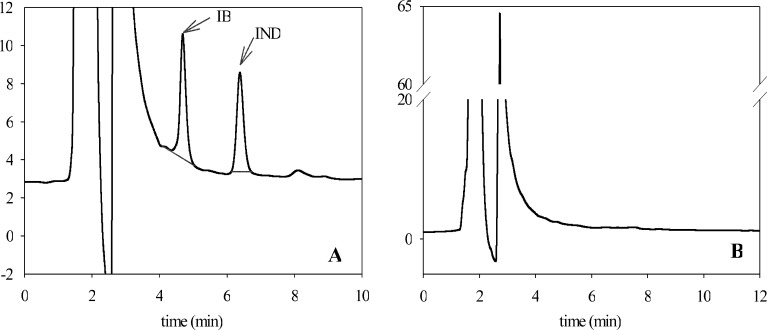

The chromatographic conditions allowed for an evident separation of IB from the internal standard. Figure 2a represents a sample chromatogram of plasma collected during the experiment, spiked with IND and subjected to SPE. Ibuprofen and IND are represented by peaks with retention times at 4.5 and 6.3 min, respectively. Blank plasma samples did not show any peaks with retention times after 4 min (Fig. 2b). This suggests absence of interferences of the analysed substances (IB and IND) with endogenous compounds. A linear correlation between IB/IND peak area ratio and IB concentration (CIB 0.2–20 μg/ml) was clearly demonstrated (R 2 = 0.9999) and is given by Eq. (2).

|

2 |

Fig. 2.

Sample HLPC chromatogram of analysed plasma collected during the experiment, spiked with an internal standard (IND, 2.5 μg/ml) and subjected to solid-phase extraction a and representative HPLC chromatogram of extracted blank plasma sample b

The coefficient of variation for the repeatability (within-a-day) and the reproducibility (in-between-days) analyses was 2.06 ± 3.18% and 10.05 ± 7.03%, respectively. The percentage of recovery from rabbit plasma was 75.5 ± 8.3% for IB and 84.5 ± 7.6% for IND. The method proved to be accurate, with 99.3 ± 1.5% of IB detected in the analysed samples. The quantification and detection limits were 0.2 and 0.05 μg/ml, respectively.

Drug Formulations

The properties and stability of ibuprofen–OHB drug formulations as well as physicochemical characteristics of the conjugate have been discussed elsewhere (9). Briefly, concentrations of ibuprofen-OHB, size of the emulsion oily droplets as well as pH did not change significantly during the stability test (3% decrease in concentration after 90 days was observed). On average, upper limit of diameter for 50% of droplets (d0.5) was approximately 1.50 while the pH was 6.10. This did not change during sterilisation process.

Pharmacokinetics of IB in Rabbits

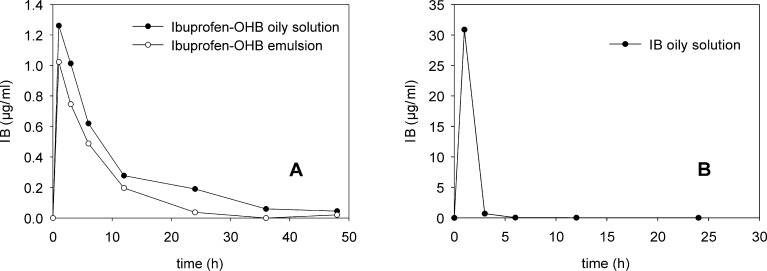

The IB plasma concentrations after administration of each formulation are shown in Table I and Fig. 3. Except for two cases (animals 2 and 8, Table I), the maximum concentration of IB in plasma was detected after approximately 1 h, irrespective of the type of formulation. Average IB Cmax values for ibuprofen–OHB preparations were 1.3 and 1.0 μg/ml for the oily solution and emulsion, respectively. However, this difference was not found to be significant (p < 0.05). A higher concentration of IB in plasma (Cmax 48.5 μg/ml) was found after injection of IB compared with ibuprofen–OHB, despite administration of a lower dose of IB (25 mg/kg versus 40 mg/kg in case of ibuprofen-OHB). Six hours after injection, detectable IB concentrations were only observable in plasma of three rabbits receiving free IB; however, these samples were below the limit of quantification. In contrast, following injection of ibuprofen–OHB formulations, detectable IB plasma concentrations (up to 1 μg/ml) were found at the time points up to 24 h. Four samples (Table I) were rejected from the analysis due to incoherence with the expected pharmacokinetic profile (rabbit 1; 24 h) or with values measured at the same conditions for the other animals from the same group (rabbit 7). It should be stressed that the AUC values were calculated on a basis of all obtained results, also these below LOQ, so they should be treated rather as approximations (however, the precision calculated as a RSD between single injections did not exceed 15% also for C values below 0.2 μg/ml). These values were still reported (Table I) due to the fact that their rejection did not significantly change the final AUC (e.g. the values for ibuprofen-OHB emulsion were 7.9 and 7.15 μg/ml·h, respectively). Moreover, the precision was assessed as sufficient to demonstrate the time of drug release.

Table I.

Individual Plasma Concentration Profiles of IB Administered in a Form of Non-nonconjugated Substance and in a Form of the Conjugate (Ibuprofen–OHB) as an Oily Solution and o/w Emulsion.

| Animal No | Time (h) | AUC0-t (μg/ml·h) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 24 | 36 | 48 | ||

| Ibuprofen–OHB oily solution (40 mg IB/kg) | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.24 | 0.58 | 0.45 | 0.23 | 0.71r | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 2 | 1.10 | 1.17 | 0.61 | 0.18a | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 3 | 0.82 | 0.55 | 0.46 | 0.15a | 0.11a | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 4 | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.60 | 0.67 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 5 | 1,68 | 1.61 | 1.00 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.36 | 0.25 | |

| 6 | 1.86 | 1.38 | 0.60 | 0.15a | 0.08a | 0.00 | 0.02a | |

| Mean ± SD | 1.26 ± 0.42 | 1.01 ± 0.44 | 0.62 ± 0.20 | 0.28 ± 0.20 | 0.19 ± 0.09 | 0.06 ± 0.14 | 0.04 ± 0.1 | 13.2 ± 6.7 |

| Ibuprofen-OHB emulsion (40 mg IB/kg) | ||||||||

| 7 | 0.28r | 0.16r | 0.20r | 0.18a | 0.03a | 0.00 | 0.09a | |

| 8 | 0.91 | 0.97 | 0.75 | 0.31 | 0.03a | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 9 | 0.56 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.19a | 0.04a | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 10 | 1.19 | 0.72 | 0.41 | 0.19a | 0.02a | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| 11 | 0.88 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.18a | 0.06a | 0.00 | 0.03a | |

| 12 | 1.58 | 1.33 | 0.63 | 0.13a | 0.03a | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Mean ± SD | 1.02 ± 0.38 | 0.74 ± 0.42 | 0.49 ± 0.19 | 0.20 ± 0.06 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.04 | 7.9 ± 2.2 |

| IB oily solution (25 mg IB/kg) | ||||||||

| 13 | 37.36 | 2.07 | 0.01a | 0.00 | 0.01a | Not analysed | ||

| 14 | 25,28 | 0.90 | 0.14a | 0.10a | 0.00 | |||

| 15 | 54,74 | 0.72 | 0.08a | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 16 | 10.01 | 0.04a | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 17 | 19.47 | 0.06a | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| 18 | 38.41 | 0.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03a | |||

| Mean ± SD | 30.88 ± 15.91 | 0.69 ± 0.76 | 0.04 ± 0.06 | 0.02 ± 0.04 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 48.4 ± 25.1 | ||

aValues below quantification limit

rData rejected

Fig. 3.

Pharmacokinetic profiles of tested IM formulations: a Ibuprofen-OHB oily solution and emulsion (40 mg IB/kg), b IB oily solution (25 mg/kg). Values are means of at least five independent experiments (p* < 0.05; Mann–Whitney rank sum test)

Although the difference between AUCs obtained for ibuprofen–OHB preparations (13.2 μg/ml·h for the oily solution and 7.9 μg/ml·h for the emulsion) may indicate a superior bioavailability of the pro-drug administered as an oily solution, statistical analysis did not confirm significance (p = 0.129) between both preparations. Statistically significant difference, however, was shown 24 h after injection, when the concentration of IB (0.19 μg/ml, with results below LOQ) following administration of the oily solution of ibuprofen-OHB was higher than after injection of the emulsion (all results below LOQ).

A pronounced difference in bioavailability was demonstrated between IB and ibuprofen–OHB preparations. Despite a being nearly two times the lower dose of IB, AUC values calculated for IB oily solution (48.4 μg/ml·h) exceeded the AUC values for both ibuprofen–OHB preparations by four to six times. Consequently, the relative bioavailability of IB bounded to OHB compared with the IB preparation was relatively low (17.0% for the oily solution and 10.0% for the emulsion).

Discussion

A HPLC method was developed for the analysis of IB in rabbit plasma which proved to be reliable, precise and accurate. An internal standard (IND) chosen on a basis of previous findings (12) allowed for appropriate peak separation. Although some authors obtained better validation parameters, especially, with regards to the recovery of the analysed substance (13,14), others reported values similar to our findings (15).

An initial increase of IB plasma levels following ibuprofen-OHB administration with relatively early T max values identical to the non-conjugated IB preparation can be attributed to free IB present in the ibuprofen–OHB formulation. Administration of 25 mg IB/kg as an oily solution resulted in a Cmax of approx 30 μg/ml. Since the content of the non-conjugated drug in ibuprofen–OHB was ~2.5% (9), the animals receiving 120 mg/kg of ibuprofen–OHB (40 mg of IB), received a dose of ~1.0 mg/kg of non-conjugated drug. Hence, the expected Cmax of 1.2 μg/ml was confirmed in the experiment.

Hydrolytic breakdown of ibuprofen-OHB in vivo was confirmed by the presence of IB in the samples collected 6, 12 and 24 h after administration, while in rabbits receiving free IB, the drug could no longer be detected. The very slow rate of hydrolysis is also consistent with results obtained previously in vitro, revealing after 72 h, only 15% of non-conjugated IB in pH 6.8 simulated intestinal fluid, and no significant increase in IB concentration in different phosphate-buffered solutions at a pH range 7.0–8.0 (9). It can thus be deduced that, due to low hydrolytic rate, almost all of the substance remains in the muscle tissue.

Ibuprofen–OHB allowed for sustained release of the active compound, although the slow hydrolysis of the conjugate resulted in low plasma concentrations. This phenomenon coincides with the published results of several other groups (16,17) suggesting that the hydrolysis rate of drug conjugates depends on the nature of chemical linkage between the active molecule and the conjugated substance. Faster hydrolysis rate would require incorporation of an appropriate spacer group with hydrolytically unstable bonds between the IB and OHB moieties, which has been demonstrated to accelerate hydrolysis and allows for detection of considerably higher drug levels in blood (17). The observed hydrolysis profile makes the oligo(3-hydroxybutyric acid) conjugates particularly interesting for monocarboxylic acid drugs with considerable pharmacological activity at low doses.

Conclusion

No significant differences in pharmacokinetic characteristics between ibuprofen–OHB emulsion and oily solution have been demonstrated. In comparison to non-conjugated model drug, the conjugated form allowed for prolonged release of the active substance. It can be concluded that, due to reported lack of toxicity (5) and sustained release characteristics, drug conjugates with oligo(3-hydroxybutyric acid) are promising candidates for parenteral drug carriers.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Galenos Fellowship in the Framework of the EU Project “Towards a European PhD in Advanced Drug Delivery”, Marie Curie Contract MEST-CT-2004-4049922. The authors wish to thank Ms. Anna Kowalczyk and Ms. Iwona Kalinowska for their excellent technical assistance during the experiments.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Pasut G, Veronese FM. Polymer-drug conjugation, recent achievements and general strategies. Prog Polym Sci. 2007;32:933–961. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamidi M, Azadi A, Rafiei P. Pharmacokinetic consequences of pegylation. Drug Deliv. 2006;13:399–409. doi: 10.1080/10717540600814402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duncan R, Vicent MJ, Greco F, Nicholson RI. Polymer–drug conjugates: towards a novel approach for the treatment of endrocine-related cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12:189–199. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khandare J, Minko T. Polymer-drug conjugates: progress in polymeric prodrugs. Prog Polym Sci. 2006;31:359–397. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2005.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piddubnyak V, Kurcok P, Matuszowicz A, Glowala M, Fiszer-Kierzkowska A, Jedlinski Z, Juzwa M, Krawczyk Z. Oligo-3-hydroxybutyrates as potential carriers for drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5271–5279. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zinn M, Witholt B, Egli T. Occurrence, synthesis and medical application of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoate. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;53:5–21. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(01)00218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jedlinski Z, Juzwa M, Zawidlak-Wegrzynska B, Kaczmarczyk B, Bosek I, Wanic A. Novel esters of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and methods of their preparation. Polish Patent PL 196384, 2007.

- 8.Juzwa M, Rusin A, Zawidlak-Wegrzynska B, Krawczyk Z, Obara I, Jedlinski Z. Oligo(3-hydroxybutanoate) conjugates with acetylsalicylic acid and their antitumour activity. Eur J Med Chem. 2008;43:1785–1790. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stasiak P, Ehrhardt C, Juzwa M, Sznitowska M. Characterisation of a novel conjugate of ibuprofen with 3-hydroxybutyric acid oligomers. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2009;61:1119–1124. doi: 10.1211/jpp.61.08.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zawidlak-Wegrzynska B, Kawalec M, Bosek I, Luczyk-Juzwa M, Adamus G, Rusin A, Filipczak P, Glowala-Kosinska M, Wolanska K, Krawczyk Z, Kurcok P. Synthesis and antiproliferative properties of ibuprofen–oligo(3-hydroxybutyrate) conjugates. Eur J Med Chem. 2010;45:1833–1842. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.http://www.phenomenex.com/AppManager/Files/CN-007_Extraction%20of%20Ibuprofen%20from%20Plasma%20using%20strata-X.pdf. Accessed 13 August 2009.

- 12.Sochor J, Klimes J, Sedlacek J, Zahradnícek M. Determination of ibuprofen in erythrocytes and plasma by high performance liquid chromatography. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1995;13:899–903. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(95)01306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farrar H, Letzig L, Gill M. Validation of a liquid chromatographic method for the determination of ibuprofen in human plasma. J Chromatogr B. 2002;780:341–348. doi: 10.1016/S1570-0232(02)00543-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonato PS, Del Lama MP, de Carvalho R. Enantioselective determination of ibuprofen in plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography–electrospray mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B. 2003;796:413–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2003.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallardo A, Parejo C, San Roman J. NSAIDs bound to methacrylic carriers: microstructural characterization and in vitro release analysis. J Control Release. 2001;71:127–140. doi: 10.1016/S0168-3659(01)00212-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao X, Tao X, Wei D, Song Q. Pharmacological activity and hydrolysis behavior of novel ibuprofen glucopyranoside conjugates. Eur J Med Chem. 2006;41:1352–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babazadeh M. Synthesis and study of controlled release of ibuprofen from the new acrylic type polymers. Int J Pharm. 2006;316:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]