Abstract

Injectable lipid emulsions, for decades, have been clinically used as an energy source for hospitalized patients by providing essential fatty acids and vitamins. Recent interest in utilizing lipid emulsions for delivering lipid soluble therapeutic agents, intravenously, has been continuously growing due to the biocompatible nature of the lipid-based delivery systems. Advancements in the area of novel lipids (olive oil and fish oil) have opened a new area for future clinical application of lipid-based injectable delivery systems that may provide a better safety profile over traditionally used long- and medium-chain triglycerides to critically ill patients. Formulation components and process parameters play critical role in the success of lipid injectable emulsions as drug delivery vehicles and hence need to be well integrated in the formulation development strategies. Physico-chemical properties of active therapeutic agents significantly impact pharmacokinetics and tissue disposition following intravenous administration of drug-containing lipid emulsion and hence need special attention while selecting such delivery vehicles. In summary, this review provides a broad overview of recent advancements in the field of novel lipids, opportunities for intravenous drug delivery, and challenges associated with injectable lipid emulsions.

Key words: biodisposition, lipid emulsions, microfluidization, parenteral formulations, sterilization

INTRODUCTION

Over the last decade, our understanding of diseases and the molecular pathways involved has increased exponentially. A structure activity-based rational approach has helped in designing novel potent therapeutic agents. However, many of these highly promising agents are dropped from the development pipeline because of their low aqueous solubility. In recent years injectable lipid emulsions, a heterogeneous system in which the lipid phase is dispersed as droplets in an aqueous phase and stabilized by emulsifying agents, have started evolving as a feasible vehicle for the delivery of hydrophobic compounds. This drug delivery approach finds its roots in the now well-established parenteral nutrition formulations. In this review, a brief overview of the parenteral lipid emulsions and the various facets in the development of injectable lipid emulsions for drug delivery has been discussed.

EVOLUTION OF PARENTERAL NUTRITION EMULSIONS

English naturalist William Courten, in 1678–1679, first attempted an intravenous administration of olive oil in dogs which resulted in pulmonary embolism (1,2). Later in 1873, Edward Hodder infused milk into cholera patients; two out of three patients recovered. However, later studies found that infusion of milk caused severe adverse effects (1). In 1904 Paul Friedrich infused total parenteral nutrition consisting of fat, peptone, glucose, and electrolytes, subcutaneously, in humans. However, pain associated with this route of administration was so severe that subcutaneous total parenteral nutrition administration was not considered for further development (1,3). With time it was realized that fat could be given intravenously only in the form of emulsions. Between 1920 and 1960, a large number of emulsions were prepared with varying compositions (oils and surfactants). Lipomul® (15% cotton seed oil, 4% soy phospholipids, 0.3% poloxamer 188 (w/v)) was the first intravenous fat emulsion introduced in the USA in the early 1960s (2,4). However, it was later withdrawn from the market due to severe adverse reaction (2,5,6). Intralipid® (100% soybean oil: 1.2% egg phospholipid), after around 14 years of safe clinical use in European countries, was finally approved for use in the USA in the year 1975 (5). Currently, two types of emulsions, one consisting of 100% soybean oil (Intralipid® and Liposyn III®) and the other a 50/50 blend of soybean oil and safflower oil (Liposyn II®), are marketed in the USA.

Long-chain triglyceride (LCT) (e.g., soybean oil and safflower oil) based emulsions have been widely used in the clinical setting for over 40 years now. These lipids provide a rich source of non-glucose based calories (7), essential fatty acids such as linoleic (ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (ω-6 PUFA)) and α-linolenic acid (ω-3 PUFA), vitamins E and K (8). However, high proportions of ω-6 PUFA, 52–54% in soybean oil and 77% in safflower oil, have raised concerns about their administration as the sole lipid source to critically ill patients and patients with compromised immune function, sepsis, and trauma (8). High levels of ω-6 PUFA leads to increased production of arachidonic acid which in turn leads to increased synthesis of potent pro-inflammatory mediators (9), tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin-6 (4). Moreover, high proportions of ω-6 PUFA have been correlated with immunosuppressive actions such as impaired reticular endothelial system function and inhibition of lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophil functions (7), although the data are somewhat contradictory (10–12). Furthermore, the high number of double bonds in ω-3 PUFA and ω-6 PUFA, makes them prone to lipid peroxidation (6). The lipid peroxides generated can lead to cell death and cause damage to DNA, lipids, and proteins (6,7). Additionally, phytosterols, an isomer of cholesterol and another component of soybean oil, has been associated with adverse effects on liver function (4,13).

An emulsion containing a 1:1 physical mixture of medium-chain triglyceride (MCTs; from coconut oil) and soybean oil was first developed to address the problems associated with the LCTs. This emulsion (Lipofundin®) contains 50% less ω-6 PUFA (8). Other advantages of MCTs include greater solubilization effect, lower accumulation in adipose tissues and liver, faster clearance, and resistance to peroxidation (10,14,15). Moreover, MCTs do not promote the synthesis of pro-inflammatory mediators (14,16) and, unlike LCTs, have been suggested to improve immune function (10,17,18). Oxidation of MCTs is more rapid and complete than LCTs and is therefore a quick source of energy (14). Incidentally, rapid breakdown of MCTs may lead to ketosis, thereby limiting their use in patients with diabetes mellitus or where clinical condition may be aggravated by acidosis or ketosis (7,19). MCTs are, however, almost always used in combination with LCTs because MCTs are not a source of essential fatty acids (20). Moreover, oxidation of MCTs leads to increased body temperature; increased energy expenditure, and induces toxicity in the central nervous system (21).

To avoid high blood levels of medium-chain fatty acids (MCFA) and yet provide essential fatty acids, structured triglyceride (STs)-based emulsions were developed (e.g., Structolipid®). STs consist of MCFA and long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) bound to the same glycerol backbone and are produced by chemical or enzymatic inter-esterification of MCFA and LCFA. For example, LMM-ST consists of LCFA at sn1-position and MCFA in sn2- and sn3-positions of the glycerol backbone (21). In patients with sepsis or multiple injuries, when compared with LCTs, STs demonstrated improved nitrogen balance and were well tolerated. No significant differences in the respiratory quotient, energy expenditure, or glucose or triglyceride levels were observed between the LCT- and STs-treated groups (22). In a recent study, STs were observed to generate lower plasma levels of leukocyte integrin expression, indicating lower inflammatory effect (23). Furthermore, STs have no effect on mononuclear phagocytic system function, does not stimulate pro-inflammatory mediator production, and alters liver function to a lesser extent than LCT- and MCT-based emulsions (21,24).

Olive oil has also been evaluated for replacing soybean oil in order to reduce ω-6 PUFA (24). Literature suggests that ClinOleic® (80% olive oil and 20% soybean oil) has neutral immunological effect and is well suited for patients who are at risk of immune suppression or are immune compromised (25) and demonstrates better liver tolerance compared with those receiving MCT/LCT emulsions (26). However, large and well-designed clinical trials in target populations are required to demonstrate its advantage over LCT- and MCT-based emulsions and to get worldwide approval (10).

Fish oil containing emulsions represent the most recent development. Fish oil is currently found in three parenteral nutrition emulsions, Omegaven® (pure fish oil emulsion); Lipoplus® (50 MCT: 40 soya bean oil: 10 fish oil); SMOFlipid® (30 MCT: 30 soybean oil: 25 olive oil: 15 fish oil). Fish oil is rich in ω-3 PUFA, particularly EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and DHA (docosahexaenoic acid). These ω-3 PUFA’s possess significantly less inflammatory and vasomotor potential and may exert antagonistic functions (9,27). Additionally, ω-3 PUFA inhibits the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β) and modulates the production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-10) (9,27). Moreover, ω-3 PUFA has the potential to prevent cardiac arrhythmias. These properties make fish oil an ideal component of lipid emulsions intended for critically ill patients with a variety of diseases (7).

Although adverse effects have been associated with the administration of large volumes of lipids in parenteral nutrition, their potential negative effects, however, may not be as severe when used for drug delivery considering the small amounts involved. For example, for an adult weighing 70 kg the daily dosage of Intralipid® 20% has been recommended as not to exceed 175 g of fat. In the case of Diprivan®, an injectable anesthetic, (10 mg/ml containing 10% w/v fat) for an adult in an ICU setting on a 24 h infusion (at a rate of 6 mg−1 kg−1 h−1), considering worst-case scenario, the daily fat administration will not exceed 100 g (28). Therefore when compared with Intralipid®, 1.8-fold less fat is administered. In the case of emulsions formulated as small volume injections, the potential the side effects associated with the lipids is not an issue altogether.

APPLICATIONS OF EMULSION IN PARENTERAL DRUG DELIVERY

Following successful commercialization of parenteral nutrition emulsions, there has been a strong and continuous interest in developing emulsions as carriers for delivering oil-soluble drugs intravenously. A number of drug-containing emulsions have been introduced in the market (Table I) and several others such as aclacinomycin A, amphotericin B, paclitaxel, docetaxel, and cyclosporine A are under development and in preclinical trials (29).

Table I.

Representative list of currently marketed drug containing injectable emulsions

| Product | Active Ingredient | Market | Composition | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleviprex | Clevidipine Butyrate | USA | SO: EP: G | (147, 148) |

| Diazemuls® | Diazepam | Europe, Canada and Australia | SO: AcM: EP: G: NaOH | (149, 150) |

| Diazepam-Lipuro® | Diazepam | Europe, Canada and Australia | SO: MCT: EL: G: sodium oleate | (151) |

| Diprivan® | Propofol | Worldwide | SO: EL: G: disodium edetate: NaOH | (28, 29) |

| Etomidat-Lipuro® | Etomidate | Germany | SO: MCT: EL: G: sodium oleate | (151) |

| Fluosol-DA® | Perfluorodecalin, Perflurotripropylamine | Worldwide | EP: pluronic F68: potassium oleate: G | (150) |

| Liple® | Alprostadil (PEG1) | Japan | SO: EP: OA: G | (150) |

| Limethason® | Dexamethasone Palmitate | Japan, Germany | SO: EL: G | (29, 150) |

| Lipo-NSAID® | Flurbiprofen axetil | Japan | SO: EL: G | (29, 150) |

| Stesolid | Diazepam | Europe | SO: AcM: EP: G | (42, 151) |

| Vitalipid® | Vitamins A, D2, E, K1 | Europe | SO: EL: G | (29, 150) |

SO Soy Oil, AcM Acetylated monoglycerides, G Glycerol, MCT Medium-chain Triglycerides, EP egg phospholipid, EL egg lecithin, OA Oleic acid

Advantages

Injectable emulsions present a number of potential advantages as drug delivery vehicle.

Reduction in pain, irritation, and thrombophlebitis: The marketed formulation of diazepam (Valium®/Assival®; Vehicle, propylene glycol/ethanol/benzyl alcohol) is frequently associated with pain, tissue irritation and venous sequelae (30,31). Administration of Diazemuls® (diazepam emulsion) to 2,435 patients resulted in only 0.4% of patient experiencing pain, with no reddening of skin or tenderness along the vein, related to the injection, in any patient (32). In rabbits, an emulsion formulation of diazepam caused significant reduction in local tissue reaction when compared to Assival® (31). Similarly, administration of clarithromycin in an emulsion formulation was associated with 2–3-fold less pain compared to that of clarithromycin lactobionate solution formulation (33). In a randomized study with 16 volunteers, Suttmann et al. observed that in contrast to emulsion formulations, a commercial etomidate formulation (Hypnomidate®) caused four subjects to develop phlebitis or thrombophlebitis, within 7 days after injection (34). Similarly, a glycoferol–water solution of diazepam (Apozepam) has been reported to cause thrombophlebitis more frequently than Diazemuls® (35).

Reduced Toxicity: Paclitaxel (Taxol®) and Cyclosporine (Sandimmune® Injection) are currently formulated in a mixture of Cremophor® EL and ethanol for intravenous injection. Cremophor® EL is associated with bronchospasms, hypotension, nephrotoxicity, and can cause anaphylactic reaction (36,37). Additionally, cyclosporine by itself exhibits dose-dependent nephrotoxicity. Formulation of cyclosporine in an emulsion formulation (1.2% egg phospholipid/10% soybean oil) did not significantly affect glomerular filtration rate (GFR), while Sandimmune and Cremophor® EL-reduced GFR to approximately 70% and 75%, respectively, of the baseline level. These results indicate that a change in the vehicle may reduce the acute nephrotoxic side effects associated with cyclosporine in the Cremophor® EL formulation (38). In mice, paclitaxel when formulated in the form of an emulsion was demonstrated to be well tolerated and the maximum tolerated dose for the emulsion formulation was approximately 3.5-fold higher (70 mg/kg) compared to Taxol® (20 mg/kg) (37). Similarly, Amphotericin B in emulsion formulations has been reported to reduce erythrocyte lysis and to preserve the monolayer integrity of kidney cells compared with the commercial drug formulation (Fungizone®) (39,40).

Improved Stability and Solubility: A number of drugs such as clarithromycin, all-trans-retinoic acid, sodium phenobarbital, physostigmine perilla ketone, and oxathiin carboxanilide demonstrated improved stability in emulsion formulation, probably due to decreased susceptibility to oxidation or hydrolysis (41). Additionally, emulsion formulations have been investigated for the solubilization of water-insoluble drugs (42).

Targeted Drug delivery: This approach has been recently extended to injectable lipid emulsions. The feasibility of this approach was demonstrated by Resen et al. in male Wistar rats wherein emulsion pre-loaded with rec-apoE was taken up to a greater extent (70% of the injected dose) by the liver compared with the control formulation without apoE (30% of the injected dose) (43). Studies targeting the asialoglycoprotein receptors localized on liver parenchymal cells and mannose and fructose receptors on non-parenchymal liver cells have also been reported (44, 45).

Disadvantages

Although injectable emulsions present a number of potential advantages the number of approved products is relatively low (Table I). Some of the major issues preventing a broader application of emulsions in drug delivery are:

LCT and MCT approved by the regulatory agencies are not necessarily good solvents of lipophilic drugs.

Even if the drug shows reasonable solubility in the oil phase, the oil phase in the emulsion system generally does not exceed 30% causing drug-loading challenges for drugs with high dose requirements. Development of novel oils with improved drug solubility would require extensive toxicity studies.

Incorporated drugs may render the emulsion physically unstable during storage making formulation efforts challenging. There are strict regulatory requirements with respect to the control of droplet size of injectable emulsions.

Limited number of approved safe emulsifiers to stabilize the emulsion system, limiting the pharmaceutical scientist to circumvent formulation challenges, and develop emulsion system with desired target product profile.

INJECTABLE EMULSION COMPONENTS

Lipids

Lipids (LCTs and MCTs) approved by the regulatory agencies, alone or in combination, are generally first-choice for developing drug emulsions. LCTs such as triolein, soybean oil, safflower oil, sesame oil, and castor oil are approved for clinical use. Approved MCTs include fractionated coconut oil, Miglyol® 810, 812, Neobee® M5, Captex® 300 (42). Solubility and stability of the active pharmaceutical ingredient, however, govern the selection of the lipid phase. MCTs have been reported to be a better solubilizer and exhibit greater oxidative stability compared to LCTs (10,14,15,46). Triglycerides with short-chain fatty acids, such as tributyrin (C4), tricaproin (C6), and tricaprylin (C8), have been reported to be better solubilizers of paclitaxel than LCTs (29,47). Vitamin E, another lipid approved for parenteral use, has been demonstrated to solubilize a number of lipophilic drugs (48) and has been recently used to develop an emulsion formulation of paclitaxel (29,37). The oil phase must be of high purity and free of undesirable components such as peroxides, pigments, decomposition products, and unsaponifiable matters such as sterols and polymers. Lipid peroxides, already present or formed during storage, can serve as initiators of oxidation and destabilize compounds susceptible to oxidation. Stickley et al. demonstrated that NSC 629243, an anti-HIV drug, was oxidatively degraded in various oil phases due to presence of peroxides in the oil. The shelf-life of the drug in various oils varied from <1 to >100 days, depending on the type of oil and its supplier. Oxidation was inhibited by the incorporation of an oil-soluble thioglycolic acid into the oil. Therefore, oxidation of oil and drug during preparation and storage must be minimized by the addition of antioxidants such as α-tocopherol, thioglycolic acid, or by manufacturing under a nitrogen atmosphere (46,49).

Emulsifiers

Emulsions are thermodynamically unstable systems and will eventually undergo physical changes (e.g., aggregation, creaming, and droplet growth) over time. Emulsifiers stabilize emulsions by reducing the interfacial tension of the system and by providing enough surface charge for droplet–droplet repulsion. The choice of emulsifier is driven by its toxicity profile, intended site of delivery, and stabilizing potential. Natural lecithin, obtained from egg yolk, has been used extensively to stabilize injectable emulsions (29). These emulsifiers are biocompatible, nontoxic, and are metabolized like natural fat (30). However, hydrolysis of natural lecithin during emulsification, sterilization and storage leads to the formation of lysophospholipids, with detergent like properties, and causes hemolysis. Although, such effects have been rarely reported in clinics lysophospholipid levels must be controlled (50). Combination of synthetic surfactants with lecithin, use of purified lecithin, and addition of free fatty acids has been suggested to reduce the formation of lysophospholipids (46,50). Polyethylene glycol (PEG) lipids such as polyethylene glycol-modified phosphatidylethanolamine (PEG-PE) have been used as emulsifiers/co-emulsifiers to sterically stabilize emulsion formulations through the presence of PEG head groups at the emulsion surface (51–53). Additionally, the steric stabilization and/or increased hydrophilicity imparted by these emulsifiers have been demonstrated to reduce the affinity of the emulsion droplet for the mononuclear phagocyte systems (53). Non-ionic surfactants, especially Pluronic® F68, also hold great potential. Injectable emulsions stabilized with Pluronic® F68, either alone or in combination with phospholipids, have been shown to improve the stability of emulsions. However, long-term administration of emulsions containing Pluronic® F68 has been associated with so-called “overloading” syndrome characterized by hyperlipidemia, fever, anorexia, and pain in the upper stomach, hemolysis, and anemia (46,54–57). Systemic toxicity, mainly hemolysis, and problems during autoclaving have limited the use of a number of, otherwise excellent, emulsifying agents (58).

Aqueous Phase

Additives such as tonicity modifiers, antioxidants and preservatives are usually added to the aqueous phase (water for injection). Tonicity adjustment can be achieved with glycerin, sorbitol, or Xylitol (46,58). Dextrose is generally not used for tonicity adjustment because it interacts with lecithin and leads to discoloration of the emulsion (58). Buffering agents are generally not added to the emulsion because there is the potential for buffer catalysis of the hydrolysis of lipids (46). Additionally, buffering agents consist of weak or strong electrolytes which can affect the stability of the phospholipid stabilized emulsions. A number of electrolytes have been demonstrated to interact with charged colloids, through nonspecific and specific adsorption, causing physical alterations such as a change in the surface potential which can ultimately lead to emulsion destabilization (59). Small amount of sodium hydroxide is used to adjust the pH of the system to around 8.0 before sterilization. A slightly alkaline pH is preferred because the pH decreases during sterilization, and on storage, due to the production of free fatty acids (FFAs) (46,58). Antioxidants such as α-tocopherol, ascorbic acid, and deferoxamine mesylate are generally added to prevent oxidation of the oil and drug substance (46,60). Additionally, antimicrobial agents such as EDTA, and sodium benzoate and benzyl alcohol, found in Diprivan® (AstraZeneca) and propofol injectable emulsion (Hospira, Inc.), are sometimes added to the aqueous phase to prevent microbial growth (46,61–63).

MANUFACTURING

Formulation Process

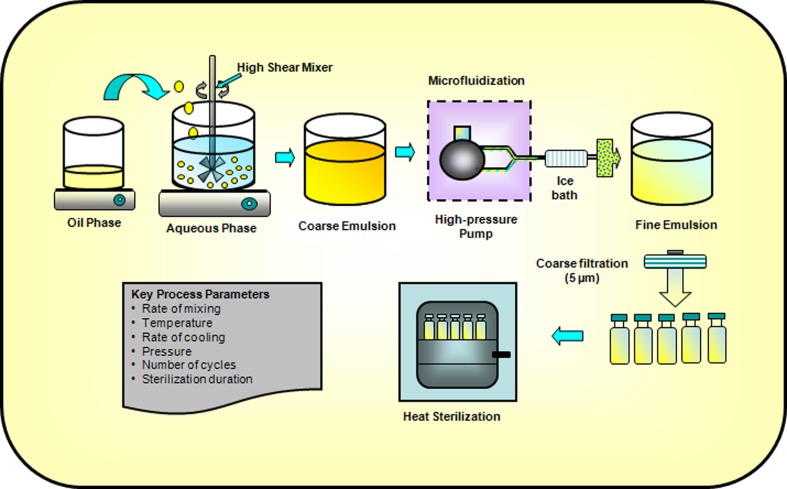

Figure 1 depicts the key processes involved in the production of injectable lipid emulsions. Water soluble and oil-soluble ingredients are generally dissolved in the aqueous phase and oil phase, respectively. Emulsifiers, such as phosphatides, can be dispersed in either oil or aqueous phase. Both phases are adequately heated and stirred to disperse or dissolve the ingredients. The lipid phase is then generally added to the aqueous phase under controlled temperature and agitation (using high-shear mixers) to form a homogenously dispersed coarse emulsion (46,58). Coarse emulsions with a droplet size smaller than 20 μm generally produces unimodal and physically stable fine emulsions (64). The coarse emulsion is then homogenized (using a microfluidizer or a high-pressure homogenizer) at optimized pressure, temperature, and number of cycles to further reduce the droplet size and form fine emulsion (65,66). Factors such as type and concentration of oil phase and surfactants, operating temperature, pressure, number of cycles, etc. can influence the mean droplet size during high-pressure homogenization and microfluidization. The USP <729> specifies that throughout the shelf-life mean droplet size and PFAT5 (volume-weighted percentage of fat globules ≥5 μm) of an injectable fine emulsion should be ≤500 nm and ≤0.05%, respectively (67,68). For example, the mean droplet size of Intralipid 10% and 20% has been reported to be 276 and 324 nm, respectively (65). The pH of the resulting fine emulsion is then adjusted to the desired value and the emulsion is filtered through 1–5 μm filters (64). The fine emulsions are usually packed in USP type I glass containers. Siliconized containers are sometimes used to prevent droplet size growth (58). Plastic containers are permeable to oxygen and contain oil-soluble plasticizers and are thus usually avoided (46,58). Additionally, teflon-coated vial plugs/stoppers are usually used to prevent oxygen permeation and softening on contact with the oil phase (46,58). The entire process (filtration/coarse and fine emulsion preparation) should be carried out under nitrogen atmosphere whenever possible and especially in cases where the excipients and drugs are sensitive to oxidation (46,58,60).

Fig. 1.

Key unit operations for preparing lipid emulsions

Drug Incorporation Methods

Water-insoluble drugs, with or without the aid of co-solvents, can be incorporated into the emulsions by dissolving the drug in the oil phase prior to emulsification (de novo method) or added to pre-prepared emulsions (extemporaneous addition). For drugs that are highly oil soluble, the de novo method, which involves dissolving the therapeutic agent into the oil phase prior to emulsification, is usually adopted (42,69). In some cases, elevation of temperature and use of fatty acids as lipophilic counter-ions can help in the solubilization process (33,70). Alternately, oil-soluble drugs that are liquid at room temperature, such as halothane and propofol, can be extemporaneously added to pre-formed emulsions (e.g., Intralipid®) whereon the drug preferentially partitions into the oil phase (42). Recently, a solvent-free novel SolEmuls® Technology has been developed that localizes the drug at the interface of the emulsion. In this approach, the drug, as ultra-fine powders/nanocrystals, is added to pre-formed emulsions (e.g., Lipofundin® and Intralipid®) or to coarse emulsions, and the mixture is then homogenized until the drug crystals are dissolved, resulting in localization of drug at the interface (69,71,72). Amphotericin B formulated using this technology has been shown to be more effective and less toxic than the commercially available formulation (73). However, it has been suggested that in order to take advantage of emulsion dosage forms it is desirable to incorporate the drug into the innermost phase of the emulsion (70).

Drugs that are slightly soluble in oil can be incorporated into the emulsions with the aid of co-solvents (42,64). The solvents are evaporated during the manufacturing process. Another approach involves dissolving drug and phospholipids in organic solvents followed by evaporation of the organic phase under reduced pressure in round bottom flasks to form a thin film. Upon sonication with the aqueous phase, a liposome-like dispersion is formed. Addition of the oil phase to this drug-liposome dispersion followed by emulsification results in an emulsion formulation (60). However, the use of co-solvents warrants careful assessment of drug precipitation, physical and chemical stability of emulsions and drug partitioning in the formulation (42).

Figure 2 depicts the emulsion structure and possible drug molecule distribution within the emulsion system. Drug may possibly get incorporated within the oil phase, aqueous phase, phospholipid rich phase (PLR) or the mesophase. Centrifuging the emulsions will separate these phases. The PLR has been suggested to be composed of phospholipids that formed a layer at the interface between the oil phase and the aqueous phase as well as excess phospholipids dispersed in the emulsion system. The mesophase is thought to essentially consist of liposomes, also formed from excess phospholipids (74,75). Recently, Sila-on et al. investigated the effect of drug incorporation method (de novo versus extemporaneous addition) on partitioning behavior of four lipophilic drugs, diazepam (logP 2.23), clonazepam (logP 1.46), lorazepam (logP 0.99), and alprazolam (logP 0.54) in parental lipid emulsions (soybean oil (10% w/w) and Epikuron® 200) (74). Partitioning of diazepam was unaffected by drug incorporation method; both methods yielded high drug concentrations in the inner oil phase and PLR. On the other hand, partitioning of the less lipophilic drugs clonazepam, lorazepam, and alprazolam was dependent on the method of incorporation. De novo emulsification and extemporaneous addition resulted in higher drug localization in PLR, and aqueous and mesophase, respectively (74).

Fig. 2.

A schematic depicting drug distribution within the emulsion system

Sterilization

Sterilization of the formulations can be achieved by terminal heat sterilization or by aseptic filtration. Terminal sterilization generally provides greater assurance of sterility of the final product (76). However, if the components of the emulsions are heat labile sterile filtration can be used. Sterilization by filtration requires the emulsion droplet size to be below 200 nm. Recently, Constantinides et al. formulated a paclitaxel emulsion using high-shear homogenization in which the mean droplet diameter was below 100 nm and 99% cumulative droplet size was below 200 nm (37). Alternatively, aseptic processing may be employed. However, this process is very cumbersome, labor intensive and requires additional process validation data and justification during regulatory submissions (46,76).

CHARACTERIZATION OF INJECTABLE EMULSIONS

Droplet Size

Droplet size can have a direct impact on toxicity and stability of the emulsion system. Droplets greater than 5 μm can be trapped in the lungs and cause pulmonary embolism. Additionally, increase in the droplet size is the first indication of formulation stability issues. Therefore, droplet size and distribution are amongst the most important characteristics of an injectable emulsion (30,58). The USP <729> specifies a two tier method, namely Light scattering method and Light obscuration or extinction method for determining the mean droplet diameter and amount of fat globules comprising the large-diameter tail of the distribution (>5 μm), respectively. For measurement of mean droplet size use of either dynamic light scattering also known as photon correlation spectroscopy or classical light scattering based on Mie scattering theory is recommended. On the other hand, for determination of the amount of fat globules comprising the large-diameter tail of the globule size distribution (>5 μm), expressed as volume-weighted percent of fat >5 μm, use of a light obscuration or light extinction method that uses single-particle (globule) optical sizing technique is recommended (67,68). Other complementary techniques such as use of optical microscopy, atomic force microscopy and electron microscopy can also be used to determine the droplet size and morphology of the droplets (29). Detailed review of application of these techniques in submicron emulsions has been published (77,78).

Zeta Potential

Zeta potential is defined as the electrical potential at the shear plane of the emulsion droplet and is a useful parameter for stability assessment. A number of factors such as pH, ionic strength, type and concentration of emulsifiers and presence of electrolytes can affect the zeta potential of the system (78). A zeta potential value of ±25 mV has been suggested to produce a stable emulsion (79).

Viscosity

The rheological properties of emulsions have been reviewed by Sherman et al. (80). These properties can be complex and depends on a number of factors such as surfactants and oils used, ratio of dispersed and continuous phase, droplet size distribution and other factors. Flocculation of emulsions will generally increase the viscosity during storage and is important for assessing stability and shelf-life of the emulsion system.

pH

The pH of these lipid emulsions decrease during sterilization and storage as a result of increase in FFA content due to the hydrolysis of phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), the lysoderivatives of PC and PE, and the emulsified triglycerides (81). A decrease in pH can lead to a decrease in the zeta potential of the emulsion droplets and ultimately lead to emulsion instability. Thus, pH of the system should be maintained throughout the shelf-life of the emulsion (82).

In Vitro Release

Characterizing in vitro drug release from emulsions is a challenging task because of the submicron size of the droplets and difficulty in separating the continuous and dispersed phase (58). A number of experimental techniques such as dialysis bag method, diffusion cell method, centrifugal ultrafiltration technique, ultrafiltration at low pressure, and continuous and in situ flow methods have been investigated to measure the release of drug from colloidal dispersions. Detailed descriptions of these methods have been given elsewhere (58,83). However each of the above methods is associated with certain drawbacks. Ultrafiltration techniques use filtration and centrifugation steps to separate the drug released into the continuous phase from the oil droplets. However, application of external energy can result in emulsion destabilization and increase in the drug release rates (58,83).

In the dialysis bag and cell diffusion methods, a dialysis membrane separates the emulsion and the receiving medium, and the release of drug is measured over time. The drawback is that in these methods the emulsion is not diluted and the experiments are thus not performed under sink conditions. The drug in the oil phase will be in equilibrium with the drug in the continuous phase; thus partition coefficient instead of the true release rate of the drug is measured (84). Chidambaram and Burgess claimed that the surface area available for diffusion of the drug from the submicron emulsion droplets is considerably larger than the surface area of the dialysis membrane available for diffusion of the drug and can lead to further violation of the sink conditions (85).

In the in situ technique, the carrier is infinitely diluted and the released drug content is measured without separating the residual carrier bound drug. However, this method is not suitable for all compounds as it requires an analytical method which detects the drug without interference from the emulsion system (86). The continuous flow method involves addition of the drug carrier to a filtration cell containing the sink medium. The sink medium is continuously replaced with fresh medium and analyzed simultaneously. Clogging of the filter, and emulsion destabilization, limits the use of these systems for measuring true release rates.

Reverse bulk equilibrium dialysis avoids the above drawbacks. In this method, the drug incorporated emulsion is added to a sink media containing a number of small dialysis bags, previously filled and equilibrated with the sink solution. At appropriate time points these small dialysis bags are removed and the content analyzed. This method avoids violation of sink condition, destabilization of emulsion and the need for filtration and centrifugation. Additionally, this technique has the capability to mimic the in vivo situation where the drug is administered intravenously (86).

KEY CONSIDERATIONS

Impact of Processing Parameters

A monodispersed emulsion with very small mean droplet size has been suggested to improve the physical stability of emulsions (41,87,88). A number of variables such as type of oil and emulsifier, emulsifying equipment, pre-emulsion temperature, mixing time, mixer speed, rate of addition of oil, homogenization temperature, duration, and operating pressure, can influence the mean droplet size and size distribution (46,60). The droplet size is also affected by the concentration of the oil phase; generally higher the oil phase greater the droplet size (65,88). An increase in the oil phase proportion would decrease the emulsifier concentration and lead to partial or minimal interfacial surface coverage by the emulsifier. This would lead to an increase in the surface tension and an increase in the droplet size (89). To stabilize this formulation with reduced droplet size, an excess amount of emulsifier would be needed. This could further increase the viscosity of the system and also increase the risk of hemolysis (from excess free surfactants in the aqueous phase), depending on the nature of the surfactant, making administration painful (90,91).

Washington and Davis demonstrated that droplet diameter and polydispersity of a 10% emulsion decreased to a plateau after four homogenization cycles and further processing did not have a significant effect (65). In another study, Trotta et al. observed that a decrease in the mean droplet size with an increase in the number of homogenization cycles occurred only at 200 bar. At pressures of 1,000 and 1,500 bar the droplet size decreased up to three cycles after which the mean particle size increased (92). Similarly, Jafari et al. observed an increase in the emulsion droplet size with an increase in the operating pressure of the micro fluidizer (93). These observations could be explained by “over-processing” of the emulsion which would lead to domination of re-coalescence over disruption leading to an increase in the mean droplet size of the emulsion (92,93). Processing temperature can also affect the emulsion droplet size and distribution by decreasing emulsion viscosity and interfacial tension. It has been demonstrated that an increase in the operating temperature could decrease the droplet size of the emulsion (65). However, increase in temperature can alter activity of certain emulsifiers and also increase droplet re-coalescence, leading to an increase in the emulsion droplet size (93).

Impact of Emulsifiers

Emulsifiers enhance emulsion stability not only by reducing the droplet size but also by forming an interfacial film at the o/w interface. The interfacial film provides a mechanical barrier and provides repulsive forces to stabilize the emulsion system. The repulsive forces can be electrostatic (e.g., Lecithin), steric (e.g., block copolymers) or electrosteric (e.g., combination of both lecithin and block copolymer) depending on the nature of emulsifier used (41,59).

Natural lecithin used for the preparation of injectable emulsions is a complex mixture of phosphatides. The mixture consists of diacyl derivatives of PC and PE as major components and phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylserine (PS), and phosphatidic acid (PA) as minor components. A number of researchers have studied the effect of length, degree of saturation and the nature of head group of these phosphatides on emulsion stability (59). At physiological pH, PC and PE are uncharged and PA, PS, and PI are negatively charged. Emulsions prepared with pure PC have been shown to be unstable (94, 95). On the other hand, PA, PS, and PI, which from the minor components of the mixture, impart a high negative surface charge to the emulsion leading to increased stability (59,96). Thus, the degree of dispersion and stability of the emulsions can be optimized by a combination of negatively charged and neutral phospholipids or by selecting commercial lecithin containing an adequate fraction of negatively charged phospholipids (96). Rubino et al. demonstrated that PA was the most important anionic component of phosphatides for stabilizing emulsions in the presence of calcium ions (97).

The carbon chain length and degree of saturation may significantly impact the stability of lipid emulsions. An investigation by Nii and Ishii suggests that differences in the chain length and degree of unsaturation may result in differences in size, shape, phase transition temperature, and HLB which can affect the droplet size of the emulsion (98). Recently, Kawaguchi et al. examined the effect of structured PC (PC-LM), containing long- and medium-chain fatty acids at C-1 and C-2 position of glycerol, on the physiochemical properties of soybean oil emulsions, compared with purified egg yolk (PC) and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC). PC-LM emulsions were more stable and had a smaller droplet size than PC emulsions. Although, LPC emulsions demonstrated greater stability when compared to PC-LM and PC emulsions, hemolytic activity associated with LPC restricts its utility. The authors suggested that PC-LM would be more suitable for preparing injectable emulsions (99).

Emulsion formulations with phospholipids as the sole emulsifier has resulted in phase separation in some cases (100). Combinations of hydrophilic and hydrophobic emulsifiers are considered to be better options. Trotta et al. observed that a combination of lecithin and hexanoyl derivative (hydrophilic) resulted in a decrease in emulsion droplet size and increased stability of indomethacin emulsions. The zeta potential was highest for this formulation and was maintained in the presence of indomethacin also. The authors suggested that formation of mixed interfacial film (with high surface charge), and change in packing characteristics of lecithin at the interface, leads to enhanced stability (92). Similarly, combination of Pluronic® F68 and phospholipids have been demonstrated to increase the stability of diazepam and physostigmine emulsions (54,89).

Impact of Sterilization Process

Injectable emulsions stabilized by phospholipids exhibit excellent physical stability against heat-stress during autoclaving. Groves et al. suggested that upon heat sterilization, the phospholipids rapidly relocate from the aqueous phase to the oil phase. This relocation occurs in combination with the formation of a cubic liquid crystalline phase at the interface during heat sterilization which converts to a lamellar phase on cooling (101). This organization of interfacial material is responsible for enhanced stability of phospholipid emulsions on heat sterilization (101). Heat sterilization also increases FFA content as a result of degradation of the phospholipid emulsifier (81). Increased levels of FFAs increases the zeta potential leading to enhanced stability (50). However, excess FFA can cause serious adverse effects (82) because of which USP limits the level of FFAs in an injectable emulsion formulation (≤0.07 mEq/g of Oil).

Jumma and Muller observed that Pluronic® F68 stabilized emulsions, unlike Tween® 80, Cremophor® EL, and Solutol® H15, did not demonstrate any significant changes in the droplet size upon autoclaving. The authors suggested that the high cloud point of F68 helped resist dehydration and damage of the emulsifier film at high temperatures during autoclaving. Additionally, Pluronic® F68 was effective in the presence of calcium ions and at different pH values (102). A combination of phospholipids (Lipoid S 75) and the non-ionic emulsifier Solutol® H15 (1:1 w/w) was also observed to be suitable for autoclaving because of a high cloud point, increased zeta potential and steric stabilization (103). Charturvedi et al. suggested that acidic emulsions (before sterilization) may result in higher droplet size upon autoclaving compared to slightly alkaline emulsions due to the influence on the film thickness and a reduction in the dissociation of FFAs (104).

BIOLOGICAL FATE OF INJECTABLE LIPID EMULSIONS

Intravenous emulsions are cleared either by the mononuclear phagocyte systems (MPS; e.g., kupffer cells and splenic macrophages) or metabolized as endogenous chylomicrons (29). Chylomicrons and lipid emulsions are both rich in trigylcerides (TG) and are stabilized by a phospholipid assembly (PL). The mean diameter of the fat emulsions (200–320 nm) is within the range of the chylomicrons (75–1,000 nm). As a result, the metabolic fate of the injectable emulsions has been suggested to be analogous to that of chylomicrons. However, in contrast to chylomicrons, lipid emulsions do not posses apolipoproteins and cholesteryl ester and have higher phospholipid content (105). Following intravenous administration, fat emulsions acquire, within a few minutes, apoproteins such as apo-E, apo-CI, apo-CII, apo-CIII, and apo-AIV, from high-density lipoproteins (HDL) and very low-density lipoproteins (VDL). Apo-CII acts as LPL (lipoprotein lipase) activator and apo-E helps in hepatic removal of remnants by liver (29,75). Once the emulsions acquire apoproteins the droplets bind to the LPL leading to the hydrolysis of TG and production of FFA which are taken up adjacent tissues as a source of energy or stored in adipose tissues. The phospholipid and TG content of the lipid emulsions in the blood circulation are also continuously modified by the cholesteryl ester transfer protein (transfers both the TG and the PL to HDL and VDL) and phospholipid transfer protein (transfers PL to HDL). These processes reduce the size of the emulsion droplet and forms much smaller cholesterol rich, TG and PL depleted, residual particles referred to as chylomicron remnants. The chylomicron remnants are then cleared mostly in the liver by low-density lipoprotein receptors (LDL) or by LDL receptor-related proteins and non-receptor mediated pathways heparin sulfate proteoglycans and other ligands (75,105,106).

PHARMACOKINETICS AND TISSUE DISTRIBUTION

Some of the studies comparing the pharmacokinetics, pharamacodynamics and tissue distribution of drugs administered in solution versus emulsion formulations have been summarized in Table II. These studies demonstrate that emulsions may or may not have a significant impact on the distribution and elimination of drugs. Several molecules formulated as emulsions have exhibited pharmacokinetic parameters similar to that of a solution dosage form (107–112). One of the main reasons for not observing any difference has been attributed to a rapid release of the drug from the emulsion. Influence of lipophilicity on the retention of the drug in the emulsions has been reported in several studies (107,113–115). Takino et al. concluded that drugs with log P > 9 remained in the circulation within the emulsion system and that the in vivo disposition of such drugs can be controlled by changing emulsion formulation characteristics (113). However, many drugs such as chlorambucil (log P 1.7), docetaxel (log P 4.1), sudan II (log P 5.4), and cinnarizine (log P 5.8) with lower log P have also been successfully formulated in emulsion formulations with improved pharmacokinetics compared with solutions (114,116–118). This improvement has been attributed to increased steady-state partitioning of the drugs into the particular oil phase used in these studies, or to an interaction with the phospholipid bilayer, as a result of which the drug is slowly released and shows extended presence in the plasma compartment (114,116–118). Therefore, other than log Poct/water, estimation of partitioning of the drug in various oil phases and interaction of drug with the phospholipids used would help in understanding the release of drug form the emulsion formulations. However, for drugs without sufficient lipophilicity, one approach to increase the lipophilicity and retention in the emulsion system is prodrug derivatization. Several reports indicate that lipophilic prodrugs have higher affinity to, and are thus retained in, the oil phase of the emulsion relative to the parent drug. Kurihara et al. reported that following intravenous administration rhizoxin (log P 1.9) was rapidly cleared from the plasma in comparison to its prodrug palmitoyl rhizoxin RS-1541 (log P 13.8) (107). Similarly, prostaglandin E1 prodrug, etoposide oleate, and paclitaxel oleate have been successfully formulated in the form of emulsions (119–121).

Table II.

Comparison of solution and emulsion formulation with respect to pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and tissue distribution of injectable drugs

| Drug / Formulations | Dose (mg/kg) | Outcome* | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alacinomycin A (log P 1.0) | 5, 10, 24 (mice) | • Higher plasma AUC | (152) |

| Solution: Drug dissolved in saline | • Heart, lung, kidney uptake – Lower; Liver and spleen uptake – similar | ||

| Emulsion: D:Vitamin E:PEG DSPE:Chol (~123 nm) | • Lower acute toxicity and greater antitumor effects | ||

| All- trans retinoic acid (ATRA) (log P 6.6) | 0.6 /day; 3–7 days (mice) | • Higher blood concentration | (153, 154) |

| Solution: [3H] ATRA dissolved in serum or miceller solution | • Higher liver accumulation | ||

| Emulsion: [3H] ATRA:SO:EYPC:Chol (~133 nm) | • Reduced liver metastatic nodules number and liver weight; Prolonged survival time | ||

| 2-(Allythio) Pyrazine (log P 1.94) | 50 (rats) | • Lower t ½, MRT, AUC, and V dss | (122) |

| Solution: D in 40% PEG200 | • Faster (~2.4 fold) CL from blood | ||

| Emulsion: SO:SL: water | • Higher tissue uptake indicates MPS uptake | ||

| Chlorambucil (log P 1.7) | 10 (mice) | • Higher AUC, MRT, t ½ and V ss; slower plasma CL | (116) |

| Solution: Drug in acidified ethanol, PG, phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) | • Tissue distribution - No significant difference | ||

| Emulsion: D:SO:EYPC: Chol (~131 nm) | • Significantly greater tumor growth suppression | ||

| Cinnarizine (log P 5.8) | 2 (rats) | • Increased plasma AUC, decreased CL and Vss | (117, 155) |

| Solution: D in Tween 80, PG (pH 4.0) | • Lower CNS tissue uptake and hence reduced toxicity | ||

| Emulsion: D:MCT:LCT:EYPC: Tween 80: PF 68:SOL (~140 nm) | |||

| Clarithromycin (log P 1.7) | 22.5 (rats) | • No significant difference in PK parameters between solution and emulsion, however, V SS was higher in solution | (112, 156) |

| Solution: D in phosphoric acid (pH 6.0) | |||

| Emulsion: D-phospholipid complex:SL :MCT :LCT: Tween 80: PF 68:SOL (~140 nm) | |||

| Cylosporin A (log P 2.92) | 3 (rats) | • No significant difference in PK parameters and tissue distribution between solution and emulsion | (108, 157) |

| Solution: Sandimmune® | |||

| Emulsion: SO:EYPC (~200 nm) | |||

| Docetaxel (log P 4.1) | 12 (rats) | • Greater AUC, higher C max, low CL and low V dss | (118, 158) |

| Micellar Solution: D in Tween 80 and ethanol | • Increased plasma concentration | ||

| Emulsion: D:SO: MCT: SL: PF 68 (~162 nm) | |||

| KW-3902 (log P 4.7) | 0.1 and 1 (rats) | • No significant difference in PK parameters between solution and emulsion at both doses | (109) |

| Solution: D in Dimethyl sulfoxide and 1N NaOH | • No significant difference in tissue distribution except lung (Higher with solution at 1mpk dose) | ||

| Emulsion: D:SO:OA: EYPC (130 nm) | |||

| Menatetrenone (log P 9.5) | 30 (rats) | • Higher plasma concentration | (159) |

| Micellar Solution: D in HCO-60, Sesame oil, PG (~25 nm) | • Higher liver and spleen update indicating phagocytosis of emulsion droplets by MPS | ||

| Emulsion: D: SO: EYPC (~167 nm) | • Improved anti-hemorrhagic effect | ||

| Rhizoxin (log P 1.9) | 1 (rats) | • No significant difference in PK parameters and tissue distribution between solution and emulsion | (107) |

| Solution: PEG/DMA | |||

| Emulsion: ODO, HCO (89–114 nm) |

*Outcome comments refer to the emulsions as compared to the solution

EYPC egg yolk soylecithin, PEG Polyethylene glycol 400, HC0 60 Polyoxylethele-60-hydrogenated castor oil, DMA dimethylacetamide, ODO Dioctanoyl- decanoyl –glycerol, Chol Cholesterol, SO Soybean oil, SOL sodium oleate, OA oleic acid, MCT Miglyol 812, SL Soybean Lecithin, Pluronic F 68 PF 68, PEG DSPE polyethylene derivative of distearoylphosphatidyl ethanolamine, PG Propylene glycol

If the drug release rate from the emulsions is very slow, drug release occurs via natural fat metabolism by the liver parenchymal cells or the drug loaded droplets are cleared by MPS. Molecules with relatively lower log P values, e.g., cyclosporine (log P 2.92) and KW-3902 (log P 4.7), and which are rapidly released from the emulsion system, will in most cases show tissue distribution profile similar to that observed with a solution formulation (107–109). However, drugs with lower log P values but demonstrating increased steady-state partitioning into the oil phase, or compounds with high log P values, may demonstrate a different tissue distribution profile depending on the formulation components, metabolic fate, enterohepatic recirculation, and other factors (114,117).

Sakeda et al. examined the biological fate of blank emulsion and drug (Menatetrenone, log P = 9.5) containing emulsion in rats. The authors observed that size of the oil particles decreased with time and pretreatment with dextran sulfate, a MPS inhibitor, resulted in marked reduction of plasma clearance and a time-dependent alteration of the oil particles, indicating that oil particles were taken up by MPS. Also, drug loaded emulsion selectively accumulated in the liver, lung and spleen, suggesting the role of MPS (115). Similar uptake of drug by MPS was observed with amphotericin B and 2-(Allylthio) pyrazine containing emulsions (64,122). If the drug is to be delivered to treat disorders associated with liver and macrophages of MPS this may be desirable. However, if the target organs are other than MPS tissues it will be necessary to change the disposition of the emulsions (116).

A number of factors such as composition of the oil phase, droplet size, emulsifier and surface charge, are important factors that determine the biological fate of injectable emulsions. These factors have already being thoroughly reviewed earlier (29,123) and a brief overview and recent work is presented here.

Effect of Triglyceride Composition

Compared with LCT, MCT-based emulsions have been reported to be cleared more rapidly from the plasma (20,124). The rapid clearance has been attributed to the ability of the LPL to hydrolyze MCT more rapidly and completely compared to LCT (124). ST emulsions are oxidized at even faster rates (21). LPL has been demonstrated to preferentially cleave the TGs at the sn1 and sn3 positions resulting in the production of two FFAs and a sn2-monoglyceride (21). In moderately catabolic patients, Kurimel et al. demonstrated that ST (MLM) was cleared rapidly from the plasma, when compared to physical mixtures of MCT and LCT, indicating position/site specificity of LPL (125).

Intravascular LPL-mediated lipolysis has been suggested to have a limited role in the clearance of emulsions containing fish oil. Oliveira et al. suggested that positional specificity (sn1 and sn3) of LPL may have a role in the slow hydrolytic rates of ω-3 PUFA present in fish oil, located at the sn2 position of the triglyceride (126). Qi et al. also reported that, in contrast to ω-6 TG, clearance of ω-3 TG is dependent on LPL-mediated lipolysis to a minor extent and is independent of apoE, LDL and LDR, and lactoferrin-sensitive pathways. Fish oil, in combination with other emulsions, has been demonstrated to alter systemic clearance and peripheral tissue uptake (127,128).

Effect of Cholesterol

Cholesterol alters the metabolism of lipid emulsions. Maranhoa et al. demonstrated that triolein-egg phospholipid emulsions with high amounts of free cholesterol (>16% w/w) were rapidly taken up by the liver without significant lipolysis (129). Handa et al. observed that the emulsions containing egg phospholipid (EYPC), soybean oil (SO), free cholesterol (20:20:8.7 in molar ratio) were retained longer in the plasma and demonstrated lower hepatic uptake after intravenous injection than formulations containing EYPC and SO (20:20) (130). Clark et al. reported that increasing the cholesterol content accelerated droplet clearance from the plasma when triolein emulsions were made with EYPC and prolonged their circulation when the emulsion contained dimyristoyl phosphatidyl choline (DMPC), dipalmitoyl phosphatidyl choline (DPPC), and distearoyl phosphatidyl choline (DSPC). Lipolysis of triolein occurred only with EYPC and DMPC emulsions containing low cholesterol content and this lipolysis was blocked when the cholesterol content was increases. Lipolysis was not observed when emulsions contained DPPC or DSPC, irrespective of the cholesterol content (131). Handa et al. also investigated the in vivo disposition of intravenous emulsions composed of SO, SO and cholesterol oleate (CO), or CO alone emulsified with EYPC, in rats. SO/EYPC emulsions were rapidly cleared from the plasma and addition of CO to the emulsion retarded the plasma clearance. Complete replacement of the SO with CO resulted in enhanced plasma retention (130). Thus, presence of free cholesterol can either promote particle clearance or prolong plasma residence time in vivo depending upon the type of emulsifier and oil phase used. Therefore, a case-by-case study based on the targeted profile is required to ascertain whether or not free cholesterol should be included in the product formulation. Additionally, studies are required to understand the pharmacokinetic and tissue distribution of emulsions in the presence of esterified cholesterol.

Effect of Emulsifiers

The emulsifier used also influences the metabolism and biodistribution of emulsions. Lenzo et al. reported that a DPPC-stabilized emulsion remains in the circulation due to poor LPL metabolism (Table III) (132). However, Clark and Derksen reported that although DSPC-stabilized emulsions were resistant to LPL metabolism they were rapidly removed from the blood circulation, into the liver and spleen, indicating a role of MPS (133). The difference in the disposition profile of DSPC- and DPPC-stabilized emulsions was attributed to surface fluidity, interaction between the core TG, and association with apolipoproteins (132). Emulsions stabilized with Poloxamer 338 and Poloxamine 908 reduced the amount of drug in MPS organs (134,135). Recently, Udea et al. demonstrated that 20 oxyethylene units (OE) in hydrogenated castor oil was the minimum number required for extended circulation time in the plasma, through evasion of MPS (136). However, the same authors reported that for soybean oil/Pluronic stabilized emulsions, a large number of OE units of Pluronics were required.

Table III.

Effect of droplet size on clearance, body distribution and efficacy of injectable emulsions

| Model Compound / Formulations | Particle Size | Outcome | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| RS-1541 | 70–630 nm | ⇒ Tumor uptake: 110 nm and 220 nm > 350 nm–630 nm | (146) |

| Colloidal solution: Drug in HCO-60/DMA | ⇒ Highest anti-tumor activity - 220 nm emulsions | ||

| Emulsion: D:ODO:HCO-60 | ⇒ Enhanced delivery of drug to tumor may be achieved with controlled particle size | ||

| Species: Mice | |||

| [ 14 C]cholesterol oleate | 100 nm | ⇒ Blood circulation time: 100 nm > 250 nm | (113) |

| Emulsion: Soybean: EYPC | 250 nm | ⇒ Plasma elimination rate: 250 nm (60 % of dose recovered in liver within 10 min) > 100 nm | |

| Species: Mice | ⇒ AUC: 100 nm (4x) > 250 nm | ||

| ⇒ Reduction in size avoided RES uptake | |||

| RS-1541 | ~100 nm | ⇒ Plasma concentration: 100 nm > 243 nm > 580 nm | (107) |

| Colloidal solution: Drug in HCO-60/DMA | ⇒ MPS tissue uptake: 100 nm < 243 nm < 580nm | ||

| Emulsion: D:ODO:HCO-60 | ~243 nm | ⇒ Clearance | |

| • 100 nm – reduced CL in liver | |||

| Species: Rats | ~580 nm | • 243 nm – reduced CL in bone marrow / small intestine | |

| • 580 nm – reduced CL in kidney / small intestine | |||

| ⇒ Drug disposition is emulsion droplet size dependant |

RS-1541 13-O-palmitoyl-rhizoxin, HCO 60 Polyoxylethele-60-hydrogenated castor oil, DMA dimethylacetamide, ODO Dioctanoyl- decanoyl –glycerol, EYPC egg yolk phosphatidyl choline

Effect of Sphingomyelin and PEG Derivatives

Sphingomyelin (SM) is an important component of the lipoprotein surface and the surface concentration of SM plays an important role in metabolism and biodistribution of the emulsions (113,137–139). Takino et al. and Redgrave et al. observed that addition of SM led to a prolonged retention in the plasma and reduced uptake by the liver (113,139). The prolonged plasma retention and reduced MPS uptake can be attributed to SM induced reduced LPL-mediated lipolysis and decreased binding capacity of apoE (137,138).

Incorporation of PEG lipid derivatives has also been demonstrated to increase circulation time and reduce uptake by MPS. Lui et al. studied the effect of PEG chain length in PEG-PE (dioleoyl phosphatidylethanolamine) co-emulsified emulsions and observed that PEG with molecular weights of 2,000 and 5,000 had the greatest effect on circulation time and liver accumulation (53). PEG lipid derivatives (PEG2000 derivative of distearoylphosphatidyl ethanolamine) increased the circulation time, reduced liver uptake and produced higher anti-tumor activity with drugs such as etoposide (140). These effects of PEG derivatives can be attributed to an increased hydrophilicity of the emulsion surface and/or steric stabilization (51,53).

Effect of Droplet Size

All the factors listed above, in particular type and concentration of lipid and emulsifier used, can significantly affect the droplet size (57,88,90,112,141,142). An increase in the total interfacial area with a decrease in droplet size facilitates LPL and HL activity (143,144). However, larger sized droplets (>than 250 nm compared to <100 nm) were cleared faster, indicating a greater role of MPS, compared to LPL, in the clearance of these emulsion (144,145). Takino et al. and Kurihara et al. also demonstrated that compared to small sized emulsion, large size emulsions were rapidly eliminated from the blood circulation and were taken up by the MPS (107,113). Moreover, droplet size has been shown to determine distribution within tumor and other peripheral tissues (146). Emulsions with droplet size larger than 200 nm effectively inhibited drug penetration into the bone marrow, small intestine and other non-MPS organs, indicating size controlled disposition in the body (Table III) (107).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

In recent years, the concept of tailored emulsion for delivery of oil-soluble lipophilic compound has gained significant attention in the field of parenteral drug delivery. Clinical applications of novel lipids hold promising future for parenteral emulsion however, well-designed multicenter clinical studies, in order to determine safety and efficacy of novel lipids, are warranted. A fundamental understanding of lipid chemistry and drug solubility in emulsion system can be further explored to meet patient’s need and circumvent formulation-related challenges. The limited number of approved marketed product seems to be a key constraint in linking physico-chemical characteristics of therapeutic agents to the efficacy, safety and formulability of lipid-based drug delivery systems. A case-by-case formulation development approach needs to be considered keeping the target product profile in mind.

References

- 1.Vinnars E, Hammarqvist F. 25th Arvid Wretlind’s Lecture—Silver anniversary, 25 years with ESPEN, the history of nutrition. Clin Nutr. 2004;23:955–62. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wretlind A. Development of fat emulsions. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1981;5:230–5. doi: 10.1177/0148607181005003230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vinnars E, Wilmore D. Jonathan roads symposium papers. History of parenteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2003;27:225–31. doi: 10.1177/0148607103027003225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Meijer VE, Gura KM, Le HD, Meisel JA, Puder M. Fish oil-based lipid emulsions prevent and reverse parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease: the Boston experience. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009;33:541–7. doi: 10.1177/0148607109332773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raghunathji NB, Albert EC, Madurai G, Charles ES, inventors; Emulsion compositions for the parenteral and/or oral administration of sparingly water soluble ionizable hydrophobic drugs patent EP0215313. 1992.

- 6.Calder PC, Jensen GL, Koletzko BV, Singer P, Wanten GJ. Lipid emulsions in parenteral nutrition of intensive care patients: current thinking and future directions. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:735–49. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1744-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waitzberg DL, Torrinhas RS, Jacintho TM. New parenteral lipid emulsions for clinical use. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2006;30:351–67. doi: 10.1177/0148607106030004351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carpentier YA, Dupont IE. Advances in intravenous lipid emulsions. World J Surg. 2000;24:1493–7. doi: 10.1007/s002680010267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furst P, Kuhn KS. Fish oil emulsions: what benefits can they bring? Clin Nutr. 2000;19:7–14. doi: 10.1054/clnu.1999.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calder PC. Hot topics in parenteral nutrition. Rationale for using new lipid emulsions in parenteral nutrition and a review of the trials performed in adults. Proc Nutr Soc. 2009;68:252–60. doi: 10.1017/S0029665109001268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Battistella FD, Widergren JT, Anderson JT, Siepler JK, Weber JC, MacColl K. A prospective, randomized trial of intravenous fat emulsion administration in trauma victims requiring total parenteral nutrition. J Trauma. 1997;43:52–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199707000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenssen P, Bruemmer BA, Bowden RA, Gooley T, Aker SN, Mattson D. Intravenous lipid dose and incidence of bacteremia and fungemia in patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:927–33. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.5.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clayton PT, Bowron A, Mills KA, Massoud A, Casteels M, Milla PJ. Phytosterolemia in children with parenteral nutrition-associated cholestatic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1806–13. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)91079-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ulrich H, Pastores SM, Katz DP, Kvetan V. Parenteral use of medium-chain triglycerides: a reappraisal. Nutrition. 1996;12:231–8. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(96)00089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manuel-y-Keenoy B, Nonneman L, De Bosscher H, Vertommen J, Schrans S, Klutsch K, et al. Effects of intravenous supplementation with alpha-tocopherol in patients receiving total parenteral nutrition containing medium- and long-chain triglycerides. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56:121–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radermacher P, Santak B, Strobach H, Schror K, Tarnow J. Fat emulsions containing medium chain triglycerides in patients with sepsis syndrome: effects on pulmonary hemodynamics and gas exchange. Intensive Care Med. 1992;18:231–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01709838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gogos CA, Kalfarentzos FE, Zoumbos NC. Effect of different types of total parenteral nutrition on T-lymphocyte subpopulations and NK cells. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;51:119–22. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gogos CA, Zoumbos N, Makri M, Kalfarentzos F. Medium- and long-chain triglycerides have different effects on the synthesis of tumor necrosis factor by human mononuclear cells in patients under total parenteral nutrition. J Am Coll Nutr. 1994;13:40–4. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1994.10718369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bach AC, Babayan VK. Medium-chain triglycerides: an update. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;36:950–62. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/36.5.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bach AC, Storck D, Meraihi Z. Medium-chain triglyceride-based fat emulsions: an alternative energy supply in stress and sepsis. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1988;12:82S–8. doi: 10.1177/014860718801200610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chambrier C, Lauverjat M, Bouletreau P. Structured triglyceride emulsions in parenteral nutrition. Nutr Clin Pract. 2006;21:342–50. doi: 10.1177/0115426506021004342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindgren BF, Ruokonen E, Magnusson-Borg K, Takala J. Nitrogen sparing effect of structured triglycerides containing both medium-and long-chain fatty acids in critically ill patients; a double blind randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2001;20:43–8. doi: 10.1054/clnu.2000.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin M-T, Yeh S-L, Tsou S-S, Wang M-Y, Chen W-J. Effects of parenteral structured lipid emulsion on modulating the inflammatory response in rats undergoing a total gastrectomy. Nutrition. 2009;25:115–21. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wanten GJ, Calder PC. Immune modulation by parenteral lipid emulsions. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1171–84. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sala-Vila A, Barbosa VM, Calder PC. Olive oil in parenteral nutrition. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2007;10:165–74. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32802bf787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia-de-Lorenzo A. Monounsaturated fatty acid-based lipid emulsions in critically ill patients are associated with fewer complications. Br J Nutr. 2006;95:1029. doi: 10.1079/BJN20061760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waitzberg DL, Torrinhas RS. Fish oil lipid emulsions and immune response: what clinicians need to know. Nutr Clin Pract. 2009;24:487–99. doi: 10.1177/0884533609339071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diprivan Injectable Emulsion. AstraZeneca. Available at: http://www1.astrazeneca-us.com/pi/diprivan.pdf. Accessed 23 March 2010.

- 29.Rossi J, Leroux J-C. Principles in the Development of Intravenous Lipid Emulsions. In: Wasan KM, editor. Role of Lipid Excipients in Modifying Oral and Parenteral Drug Delivery. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 88–123. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Floyd AG, Jain S. Injectable emulsions and suspensions. In: Lieberman HA, Rieger MM, Banker GS, editors. Pharmaceutical dosage forms: dispersed systems. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1996. pp. 261–310. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levy MY, Langerman L, Gottschalk-Sabag S, Benita S. Side-effect evaluation of a new diazepam formulation: venous sequela reduction following intravenous (i.v.) injection of a diazepam emulsion in rabbits. Pharm Res. 1989;6:510–6. doi: 10.1023/A:1015928825882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Dardel O, Mebius C, Mossberg T, Svensson B. Fat emulsion as a vehicle for diazepam. A study of 9492 patients. Br J Anaesth. 1983;55:41–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/55.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lovell MW, Johnson HW, Hui HW, Cannon JB, Gupta PK, Hsu CC. Less-painful emulsion formulations for intravenous administration of clarithromycin. Int J Pharm. 1994;109:45–57. doi: 10.1016/0378-5173(94)90120-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suttmann H, Doenicke A, Kugler J, Laub M. A new formulation of etomidate in lipid emulsion—bioavailability and venous provocation. Anaesthesist. 1989;38:421–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selander D, Curelaru I, Stefansson T. Local discomfort and thrombophlebitis following intravenous injection of diazepam. A comparison between a glycoferol-water solution and a lipid emulsion. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1981;25:516–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1981.tb01696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venkataram S, Awni WM, Jordan K, Rahman YE. Pharmacokinetics of two alternative dosage forms for cyclosporine: liposomes and intralipid. J Pharm Sci. 1990;79:216–9. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600790307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Constantinides PP, Lambert KJ, Tustian AK, Schneider B, Lalji S, Ma W, et al. Formulation development and antitumor activity of a filter-sterilizable emulsion of paclitaxel. Pharm Res. 2000;17:175–82. doi: 10.1023/A:1007565230130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tibell A, Larsson M, Alvestrand A. Dissolving intravenous cyclosporin A in a fat emulsion carrier prevents acute renal side effects in the rat. Transpl Int. 1993;6:69–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.1993.tb00753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lamb KA, Washington C, Davis SS, Denyer SP. Toxicity of amphotericin B emulsion to cultured canine kidney cell monolayers. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1991;43:522–4. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1991.tb03529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forster D, Washington C, Davis SS. Toxicity of solubilized and colloidal amphotericin B formulations to human erythrocytes. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1988;40:325–8. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1988.tb05260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eccleston GM. Emulsions and Microemulsions. In: Swarbrick J, editor. Encylopedia of Pharmaceutical Technology. New York: Informa Healthcare USA. Inc; 2007. pp. 1548–65. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cannon BJ, Shi Y, Gupta P. Emulsions, microemulsions, and lipid-based drug delivery systems for drug solubilization and delivery—Part I: parenteral applications. In: Rong L, editor. Water-Insoluble Drug Formulation. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2008. pp. 195–226. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rensen PC, van Dijk MC, Havenaar EC, Bijsterbosch MK, Kruijt JK, van Berkel TJ. Selective liver targeting of antivirals by recombinant chylomicrons—a new therapeutic approach to hepatitis B. Nat Med. 1995;1:221–5. doi: 10.1038/nm0395-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ishida E, Managit C, Kawakami S, Nishikawa M, Yamashita F, Hashida M. Biodistribution characteristics of galactosylated emulsions and incorporated probucol for hepatocyte-selective targeting of lipophilic drugs in mice. Pharm Res. 2004;21:932–9. doi: 10.1023/B:PHAM.0000029280.39882.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yeeprae W, Kawakami S, Higuchi Y, Yamashita F, Hashida M. Biodistribution characteristics of mannosylated and fucosylated O/W emulsions in mice. J Drug Target. 2005;13:479–87. doi: 10.1080/10611860500293367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Floyd AG. Top ten considerations in the development of parenteral emulsions. Pharm Sci Technol Today. 1999;2:134–43. doi: 10.1016/S1461-5347(99)00141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kan P, Chen Z-B, Lee C-J, Chu IM. Development of nonionic surfactant/phospholipid o/w emulsion as a paclitaxel delivery system. J Control Release. 1999;58:271–8. doi: 10.1016/S0168-3659(98)00164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Constantinides PP, Tustian A, Kessler DR. Tocol emulsions for drug solubilization and parenteral delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56:1243–55. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strickley RG, Anderson BD. Solubilization and stabilization of an anti-HIV thiocarbamate, NSC 629243, for parenteral delivery, using extemporaneous emulsions. Pharm Res. 1993;10:1076–82. doi: 10.1023/A:1018935311304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herman CJ, Groves MJ. Hydrolysis kinetics of phospholipids in thermally stressed intravenous lipid emulsion formulations. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1992;44:539–42. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1992.tb05460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wheeler JJ, Wong KF, Ansell SM, Masin D, Bally MB. Polyethylene glycol modified phospholipids stabilize emulsions prepared from triacylglycerol. J Pharm Sci. 1994;83:1558–64. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600831108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Papahadjopoulos D, Allen TM, Gabizon A, Mayhew E, Matthay K, Huang SK, et al. Sterically stabilized liposomes: improvements in pharmacokinetics and antitumor therapeutic efficacy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11460–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu F, Liu D. Long-circulating emulsions (oil-in-water) as carriers for lipophilic drugs. Pharm Res. 1995;12:1060–4. doi: 10.1023/A:1016274801930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benita S, Friedman D, Weinstock M. Physostigmine emulsion: a new injectable controlled release delivery system. Int J Pharm. 1986;30:47–55. doi: 10.1016/0378-5173(86)90134-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levy MY, Benita S. Design and characterization of a submicronized o/w emulsion of diazepam for parenteral use. Int J Pharm. 1989;54:103–12. doi: 10.1016/0378-5173(89)90329-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jumaa M, Müller BW. Physicochemical properties of chitosan-lipid emulsions and their stability during the autoclaving process. Int J Pharm. 1999;183:175–84. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5173(99)00086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buszello K, Muller BW. Emulsions as drug delivery systems. In: Nielloud F, Marti-Mestres G, editors. Pharmaceutical Emulsions and Suspensions. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2000. pp. 191–229. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hansrani PK, Davis SS, Groves MJ. The preparation and properties of sterile intravenous emulsions. J Parenter Sci Technol. 1983;37:145–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Washington C. Stability of lipid emulsions for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1996;20:131–45. doi: 10.1016/0169-409X(95)00116-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Benita S, Levy MY. Submicron emulsions as colloidal drug carriers for intravenous administration: comprehensive physicochemical characterization. J Pharm Sci. 1993;82:1069–79. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600821102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Han J, Washington C. Partition of antimicrobial additives in an intravenous emulsion and their effect on emulsion physical stability. Int J Pharm. 2005;288:263–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Propofol Injectable Emulsion 1%. Hospira Inc. Available at: http://www.hospira.com/Products/productcatalog.aspx. Accessed 11 July 2010.

- 63.Driscoll DF, Dunbar JG, Marmarou A. Fat-globule size in a propofol emulsion containing sodium metabisulfite. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61:1276–80. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.12.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Collins-Gold LC, Lyons RT, Bartholow LC. Parenteral emulsions for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1990;5:189–208. doi: 10.1016/0169-409X(90)90016-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Washington C, Davis SS. The production of parenteral feeding emulsions by Microfluidizer. Int J Pharm. 1988;44:169–76. doi: 10.1016/0378-5173(88)90113-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Innocente N, Biasutti M, Venir E, Spaziani M, Marchesini G. Effect of high-pressure homogenization on droplet size distribution and rheological properties of ice cream mixes. J Dairy Sci. 2009;92:1864–75. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.USP. <729>Globule size distribution in Lipid Injectable Emulsions. The United states Pharmacopeia 33/National Formulary 28; 2009. pp. 314–6.

- 68.USP. Lipid injectable emulsions. The United States Pharmacopeia 33/National Formulary 28; 2009. pp. 3641–3.

- 69.Akkar A, Müller RH. Intravenous itraconazole emulsions produced by SolEmuls technology. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2003;56:29–36. doi: 10.1016/S0939-6411(03)00063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Singh M, Ravin LJ. Parenteral emulsions as drug carrier systems. J Parenter Sci Technol. 1986;40:34–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Akkar A, Müller RH. Formulation of intravenous Carbamazepine emulsions by SolEmuls® technology. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2003;55:305–12. doi: 10.1016/S0939-6411(03)00028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Müller RH, Schmidt S, Buttle I, Akkar A, Schmitt J, Brömer S. SolEmuls®–novel technology for the formulation of i.v. emulsions with poorly soluble drugs. Int J Pharm. 2004;269:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]