Abstract

In schizophrenia, glutamic acid decarboxylase 1 (GAD1) disturbances are robust, consistently observed, cell-type specific and represent a core feature of the disease. In addition, neuropeptide Y (NPY), which is a phenotypic marker of a sub-population of GAD1-containing interneurons, has shown reduced expression in the prefrontal cortex in subjects with schizophrenia, suggesting that dysfunction of the NPY+ cortical interneuronal sub-population might be a core feature of this devastating disorder. However, modeling gene expression disturbances in schizophrenia in a cell type-specific manner has been extremely challenging. To more closely mimic these molecular and cellular human post-mortem findings, we generated a transgenic mouse in which we downregulated GAD1 mRNA expression specifically in NPY+ neurons. This novel, cell type-specific in vivo system for reducing gene expression uses a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) containing the NPY promoter-enhancer elements, the reporter molecule (eGFP) and a modified intron containing a synthetic microRNA (miRNA) targeted to GAD1. The animals of isogenic strains are generated rapidly, providing a new tool for better understanding the molecular disturbances in the GABAergic system observed in complex neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia. In the future, because of the small size of the silencing miRNAs combined with our BAC strategy, this method may be modified to allow generation of mice with simultaneous silencing of multiple genes in the same cells with a single construct, and production of splice-variant-specific knockdown animals.

Keywords: miRNA, BAC, transgenic, NPY, GAD1, schizophrenia

Introduction

In the past decade, significant progress has been made in describing detailed pathophysiologic features of brain diseases, including signature patterns of altered gene expression1, 2 and disruption of fundamental neuroanatomical features of defined circuits.3, 4 Mechanistic insight has been gained from the use of various animal models, with the aim of mimicking alterations of circuits, transmitter systems or cell subtypes that may be involved in the behavioral disturbances that characterize specific psychiatric and neurologic diseases. Molecular perturbations of highly precise specificity, however, have been difficult to achieve. For example, complete deletion of a neurotransmitter receptor from multiple cell types in a genetic model may result in pathophysiological consequences, but not necessarily related to a disease state. Moreover, the traditional generation of mice by gene targeting is time consuming and can be expensive. Thus, the current state of transgenic models falls short of modulating gene expression in disease-relevant phenotypic and regional patterns.5

At a molecular level, schizophrenia is characterized by interrelated transcript deficits that consists of downregulation of BDNF, TRKB, GAD67, SST, NPY, PARV, CCK and GABRAD genes,6, 7, 8, 9, 10 implicating the cortical GABAergic interneuron as a central component of the pathophysiology underlying the disease. Perhaps the most widely replicated finding in post-mortem studies of schizophrenia is a reduced expression of glutamic acid decarboxylase 1 (GAD1),11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 which is an enzyme responsible for the synthesis of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA. Furthermore, neuropeptide Y (NPY), which is a phenotypic marker of a sub-population of GAD1-containing interneurons,17, 18, 19, 20 shows reduced expression in the prefrontal cortex in subjects with schizophrenia, suggesting that dysfunction of NPY+ cortical interneurons is also an additional core feature of this disorder.9, 20, 21, 22, 23

To develop new strategies for more closely mimicking these molecular and cellular human post-mortem findings, we have established a novel, cell type-specific in vivo system for regulation of gene expression; we combined a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC)24, 25 containing the NPY promoter-enhancer elements, the reporter molecule (eGFP) and a modified intron containing a synthetic microRNA (miRNA)26, 27, 28 targeted to glutamate decarboxylase 1 (GAD1) to generate a transgene that simultaneously downregulates GAD1 mRNA expression and expresses GFP, specifically in NPY+ neurons.

Materials and methods

BAC selection

BACs containing the mouse neuropeptide Y (mNpy) locus (Chr6: 49700790-49860898, National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Build 37.1) were identified using the Human MapViewer resource at NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/mapview/).29 The mNpy gene itself is mapped at Chr6: 49772728-49779506 bp, + strand. The mNpy containing BAC RP24-386I9 was selected because the chromosomal sequence was derived from a C57BL/6 genomic source and the mNpy gene was centrally located within the BAC. The RP24-386I9 BAC was provided by the BACPAC Resource at the Children's Hospital of Oakland Research Institute in Oakland, California, (http://bacpac.chori.org/). The RP24-386I9 BAC was isolated from the original DH10B Escherichia coli strain through standard alkaline lysis protocol (available upon request) and transformed into EL250 E. coli cells (kind gift of Dr Neil Copeland, National Cancer Institute). The presence of the mNpy locus in RP24-386I9 was verified using restriction enzyme digest mapping.

miRNA selection and cloning

Two miRNAs targeting mGad1 were identified at the RNAi Codex website (mp ID 283874: acgtggatcctgctgttgacagtgagcgaccacccagtctgacatcgatttagtgaag ccacagatgtaaatcgatgtcagactgggtggctgcctactgcctcggaggatccacgt and 298398: acgtggatcctgctgttgacagtgagcgcgctctctactggtttggatattagtgaagcca cagatgtaatatccaaaccagtagagagcttgcctactgcctcggaggatccacgt). Two partially overlapping oligos were designed for each potential miRNA. PCR fill-in of these oligos generated a 100-bp fragment that contained an XhoI site at the 5′ terminus and an EcoRI site at the 3′ terminus. This fragment was ligated into the XhoI/EcoRI site of the TMP vector (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL, USA) that contains unique miR-30 sequences (9 nt) at the 5′ of the XhoI site. PCR from this ligated plasmid amplified the unique flanking miR-30 region and the intervening GAD1 miRNA (∼450 bp total) while introducing BamHI sites to the 5′ and 3′ regions of the PCR product. The BamHI-digested fragment containing fused miR30,miRNA:Gad1 was later inserted into a β–globin minigene.

BAC targeting construct generation

BACs were targeted as described previously.30 Two partially overlapping oligos were generated that contained two Lox 2272 recognition sites for CRE recombinase, separated by a SpeI site and flanked by NotI sites. This version of the recognition site for the CRE recombinase was chosen to avoid interaction with Lox sites that are commonly found in commercially available BACs. These oligos were annealed and filled in using Amplitaq Gold DNA polymerase, digested with NotI and cloned into the pGEM 11ZF (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). After sequence verification, a minigene consisting of the 3′ portion of exon 1, the entire intron 1 and the 5′ portion of exon 2 of the human β-globin gene was amplified and cloned into the SpeI site of the Lox 2272 construct described above using XbaI sites engineered into the 5′ and 3′ ends of the β-globin cassette. A BglII restriction enzyme site was introduced (through PCR mutagenesis) into intron 1 (57 bp 3′ to the exon 1 splice donor site) of the β-globin minigene to permit introduction of the miR30, miRNA:Gad1 fragment. Digestion of this plasmid with NotI released a 764-bp fragment, which was subsequently cloned into the NotI site of pEGFP-N1-BglII/NcoI (see below).

The BglII restriction site was added to pEGFP-N1 (Clontech Laboratories, Inc, Mountain View, CA, USA) by inserting an oligo at the AflII site, which was located at the 3′ end of the SV40 polyadenilation signal. This generated a plasmid designated as pEGFP-NI-BglII. The NotI fragment containing Lox 2272 flanked β-globin minigene with miR30, miRNA:Gad1 was inserted into the NotI site of pEGFP-NI-BglII, which was located immediately after the eGFP coding sequences. Two separate versions of this construct, one for each miRNA:Gad1 (283874 and 298398) were generated. These constructs were denoted Intermediate constructs. As in these constructs the expression of eGFP and the β-globin minigene was driven by the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (inherent to the eGFP-N1 parent vector) and not the restricted NPY promoter, they were suitable for testing the silencing effect of the miRNA:Gad1 precursor in cell culture assays.

A 500-nt fragment symmetrically spanning the translation start site (ATG codon) of the Npy gene was generated using PCR. During the amplification, an NcoI restriction enzyme site (CCATGG) was inserted by mutation of the nucleotides surrounding the ATG codon. The fragment was then cloned in pSTBlue-1 (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA), which is a TA cloning vector system that contains EcoRI restriction enzyme sites flanking the TA cloning insertion site. The NcoI site became a recipient of an NcoI fragment containing eGFP and the floxed minigene from the intermediate construct described above. In this way, eGFP and the floxed minigene were surrounded by the Npy homology arms necessary for the final BAC targeting event. Finally, a FRT-flanked neomycin resistance cassette (gift of Neil Copeland, National Cancer Institute and National Institute of Mental Health) was cloned into the BglII site and with this the targeting construct was completed. An EcoRI targeting fragment was then released from it and used for homologous recombination with the Npy containing BAC RP24-386I9 as described.31 BACs were then screened by PCR and confirmed with restriction mapping and sequence analysis for correct modifications. The E. coli strain containing the modified BAC was then induced with arabinose for the expression of FLP recombinase, which removed the FRT-flanked neomycin resistance cassette. Proper recombination was confirmed with restriction mapping and sequence analysis of the region of interest.

Mouse generation

The BAC DNA construct was isolated with alkaline lysis and purified with Sepharose CL-4B chromatography as described previously.32 Transgenic mice were generated by injection of circular BAC DNA construct into fertilized mouse oocytes by the Vanderbilt Transgenic Mouse/Embryonic Stem Cell Shared resource (http://www.vcscb.org/shared_resource/). Transgenic founder mice were identified by PCR using construct-specific primer pairs.

Cell culture/western blotting

Intermediate construct DNA (CMV-eGFP, miRNA:Gad1) was co-transfected into HEK-293 cells (American Type Culture Collection) along with a GAD1 expression construct (IMAGE clone 5358787) in a 3:1 ratio using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were incubated for either 24 or 48 h after transfection, at which point they were harvested into 500 μl RIPA buffer (150 m NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 50 m Tris pH 8.0) containing protease inhibitors. Western blot was performed using 50 μg total protein per lane with 1:5000 dilution of mouse anti-Gad1 monoclonal antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and 1:5000 dilution of anti-mouse-horseradish peroxidase (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase protein levels served as a reference using a rabbit antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and anti-rabbit-horseradish peroxidase. GFP expression was confirmed by fluorescence imaging of transfected cells using an Axiovert 40 CFL inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Inc, Thomwood, NY, USA) fitted with a digital camera.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunolocation studies, animals were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and transcardially perfused with 1 × phosphate buffer (PB) solution for 1 min, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde made up in 0.1 M PB (pH 7.4) for 11–30 min at room temperature. All procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science and the Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Protection of Research Subjects. Brains were then removed and postfixed for 4 h at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehyde. After washing extensively with PB, the tissue was equilibrated in 30% sucrose–phosphate buffer and subsequently transferred to a plastic mold filled with Tissue-Tek optimal cutting compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA), frozen on dry ice and stored at −70 °C until sectioned. Coronal sections, 50-μm thick, were prepared with a cryostat (CM1950, Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL, USA), and then washed several times in 0.1 M PB. Sections were stored at −20 °C in an antifreeze solution until immunostaing.

Brain sections were extensively washed in PB and then incubated for 1 h in 10% normal donkey serum in 0.1 m PB (pH 7.4). Immunostaining for eGFP was performed either with a rabbit anti-GFP (Invitrogen; 1:2000) or chicken anti-GFP (Abcam; 1:2000). Immunostaining for NPY was performed using 1:1000 dilution of rabbit anti-NPY antibody (Peninsula Laboratories, San Carlos, CA, USA). Additional rabbit anti-NPY antibodies (Immunostar, Inc, Hudson, WI, USA; 1:1000) and sheep anti-NPY (Millipore; 1:1000) were used to confirm NPY-GFP co-expression pattern (data not shown). For GAD1 immunostaining, sections were pre-incubated with 70 μg ml–1 of a monovalent Fab' fragment of donkey anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA) to block endogenous mouse immunoglobulins, and proceeded with the standard protocol for immunolabeling with mouse anti-GAD-1 (Millipore; 1:2000). The following secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch) were used for fluorescence detection: donkey anti-rabbit DyLight488, donkey anti-rabbit Cy3, donkey anti-chicken DyLight488, donkey anti-sheep Cy3 and donkey anti-mouse Cy3 (all diluted 1:250). All sections were incubated with primary antibodies for 72 h at 4 °C, washed extensively and incubated in secondary antibodies for 3 h at room temperature. Immunolabeled sections were mounted in Fluoromont-G (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA) and examined using a fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems, Inc, Bannockburn, IL, USA). For the direct detection of eGFP fluorescence, cryostat sections were washed three times in 0.1 M PB, and then mounted on slides. Images were stored and analyzed using IPLAb for Windows (version 4.03; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) scientific imaging software. Brightness and contrast were adjusted for the whole image using Adobe Photoshop CS3 software (Adobe Systems, Inc, San Jose, CA, USA).

Results

The construct

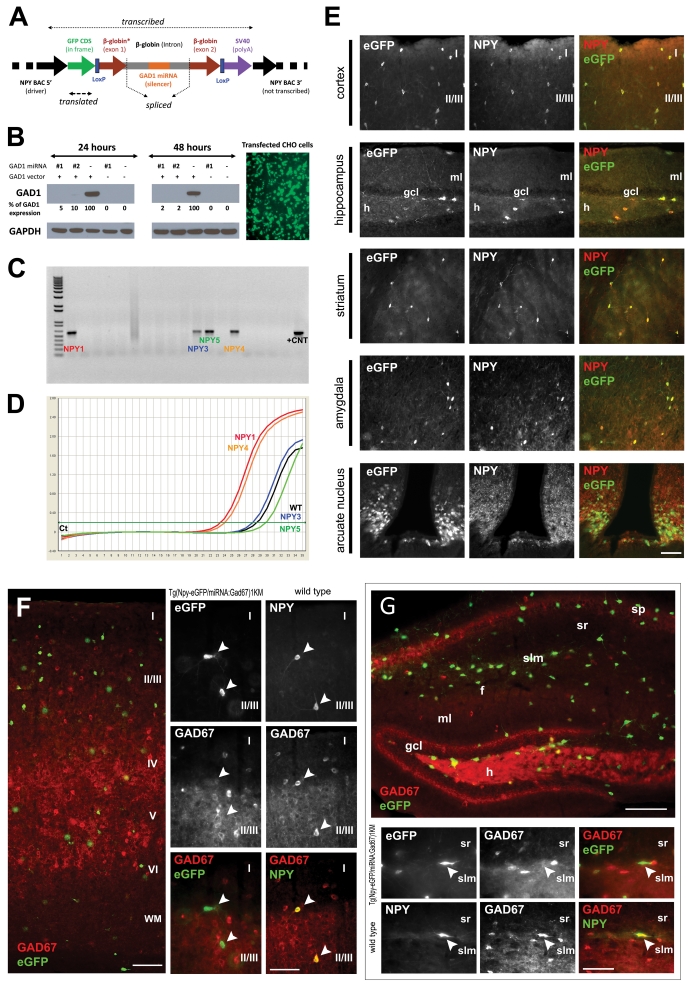

The construction of a hybrid reporter/miRNA knockdown transgenic construct was achieved through a multi-step cloning procedure, which is depicted in Supplementary Material 1. The final construct (Figure 1a) has several parts as follows. (1) A centrally located minigene containing part of the first exon, intervening intron and second exon of the human β-globin gene, providing the necessary sequence elements for expression modulation. This non-coding sequence exerts an effect as a ‘carrier' for a synthetic miRNA directed against the GAD1 mRNA. The realization that intronic localization of a miRNA (as is observed with some endogenous miRNAs) does not disrupt the protein-coding capability of the gene empirically shows that intron splicing proceeds miRNA excision; thus, we located the miRNA within an intron to allow excision of the miRNA by class 2 RNase III enzyme, DROSHA, without destruction of the coding potential of the remaining transcript.33 The processed miRNA binds the GAD1 mRNA, and the resulting miRNA:mRNA complex is targeted to the RNA-induced silencing complex for degradation.26 The minigene sequence is flanked by LoxP sites, which will allow excision of the gene-silencing aspect of the transgene in vivo while retaining the potential to express eGFP. This could theoretically be used to assess whether phenotypes associated with the transgene are due to gene expression silencing or insertional inactivation of a non-related gene during transgene integration. (2) 5′ to the silencing minigene an eGFP sequence was inserted in frame with the start codon of the BAC-encoded NPY gene (expression of NPY itself from the transgene was thereby eliminated), resulting in expression of eGFP in cells in which the transgene is expressed. (3) 3′ to the silencing minigene is a strong polyadenylation sequence (SV40-pA) to ensure that the transgene does not ‘read through' to downstream NPY coding regions. (4) Finally, the eGFP-silencing minigene-SV40-pA sequences are flanked by the NPY BAC, containing the full complement of NPY genetic regulatory elements, thus providing cell type-specific expression.

Figure 1.

Generation and validation of the Tg(Npy-eGFP/miRNA:Gad1)1KM mice. (a) Schematic linear representation of the construct. Flanking regions of the construct are derived from the driver NPY BAC that provides interneuron subtype-specific expression of the construct. The 5′ region of the driver BAC (NPY promoter region) ensures specific expression of eGFP, and the SV40-pA ensures proper polyadenylation. The construct, containing a non-functional (not translated) part of β-globin exons 1 and 2, and intron 1 in its entirety, is spliced by the cellular machinery, liberating the intron that contains the 70–100 nucleotide long double-stranded miRNA directed against GAD1. The spliced intron-miRNA:Gad1 is processed through DROSHA and exported from the nucleus. In the cytoplasm the miRNA binds to and degrades the endogenous GAD1 mRNA through an RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC).33, 50 The eGFP mRNA is translated, thus fluorescently labeling cells of interest. The presence of LoxP sites facilitates generation of animals lacking the silencing part of the miRNA:Gad1 construct, but still expresses eGFP, to serve as controls. (b) miRNA-mediated downregulation of GAD1 in vitro. CHO cells co-transfected with GFP reporter vector alone (−), two different intermediate constructs (GFP reporter vectors containing two different synthetic miRNAs directed against GAD1—nos. 1 and 2), and GAD1 expression vector. The cells were harvested at 24 and 48 h after transfection. Western blot analysis confirmed that the two different miRNAs against GAD1 were correctly processed from the β-globin intron and that both miRNAs strongly downregulated GAD1 expression. Similar results have been obtained in HEK293 cells with stable expression of GAD1 that were engineered in our laboratory (data not shown). The same cells transfected with CMV-eGFP,miRNA:Gad1 show high levels of eGFP expression, confirming that the construct performs as expected. In addition, the processing of the miRNA from the β-globin intron in the construct does not interfere with eGFP protein translation. (c) Identification of founder animals by PCR-based genotyping of founder animals using eGFP primers with genomic DNA as template. The first lane represents size marker, and the last lane corresponds to positive control, with the remaining lanes containing eGFP amplification products from the genomic DNA of individual animals. The 550-nt product on a 1% agarose gel indicates construct incorporation into the genome of four founder animals (NPY 1, 3, 4 and 5). Similar results were obtained by Southern hybridization (data not sown). (d) Quantitative PCR (qPCR) amplification plot from frontal cortex of founder animals using eGFP construct-specific primers. The y axis denotes PCR product accumulation, and the x axis denotes amplification cycle number. Note that two (NPY1 and NPY4) of the four founder lines that incorporated the NPY-BAC/GAD1-miRNA construct reported functional eGFP expression. These lines were used for further characterization. (e) The NPY-BAC/GAD1-miRNA construct showed the expected tissue distribution in the brain. Micrographs depict the fidelity of co-localized eGFP and NPY in adult transgenic animals from line Tg(Npy-eGFP/miRNA:Gad1)1KM. The left column micrographs denote eGFP immunostaining, middle column micrographs represent sections labeled with anti-NPY and the right column micrographs illustrate pseudocolored composite of eGFP-NPY co-localization in the same tissue sections. In the cortex, roman numerals denote cortical laminae. Hippocampus abbreviations: gcl, granule cell layer; h, hilus; ml, molecular layer. Note that all GFP+ neurons are also NPY+, and all NPY+ cells are GFP+, suggesting that the construct is specifically and exclusively expressed in the phenotypically appropriate target cell population. Calibration bar=100 μm. (f, g) Tg(Npy-eGFP/ miRNA:Gad1)1KM animals show undetectable GAD1 levels in the frontal cortex and hippocampus of NPY+ cells compared with NPY+ neurons in control animals. eGFP-GAD1 double-immunohistochemistry (eGFP, green; GAD1, red) was performed from a coronal section through the frontal cortex and hippocampus of a transgenic animal. Wild-type control littermate was double stained against NPY and GAD1. Same cells are denoted by arrowheads. In the cortex, roman numerals denote cortical laminae. Hippocampal abbreviations: f, hippocampal fissure; gcl, ganglion cell layer; h, hilus; ml, molecular layer; slm, stratum lacunosum moleculare; sp, stratum pyramidale; sr, stratum radiatum. Note that all NPY+ cells (white arrows) are GAD1+ in control animals, whereas none of the eGFP+ (and thus NPY+) neurons (white arrows) show GAD1 staining in the transgenic mice. Moreover, note the large number of single-labeled GAD1+ neurons that are eGFP– in the transgenic line. These data indicate selective, miRNA-mediated, cell type-specific downregulation of GAD1 in NPY+ interneurons. Calibration bars=60 μm (overview figures) and 100 μm.

The specific miRNA for the gene of interest (GAD1) was inserted into the intron 5′ proximal to the branch point required for lariat formation during pre-mRNA processing. The human β-globin gene has been extensively characterized in studies of mRNA processing,34 including the structure of the intron; insertion of sequence >20 bp 5′ of the branch point does not interfere with RNA processing. The presence of our custom miRNA construct, located within an intron 3′ to the eGFP coding region, did not impair eGFP protein expression and resulted in the generation of a miRNA competent to target RNA-degradation complexes to the GAD1 mRNA (see below).

In vitro silencing of GAD1

To analyze the validity of our approach, we tested an intermediate eGFP-miRNA construct (before integration into the NPY BAC) on CHO and HEK293 cell systems. Both transiently transfected CHO cells with GAD1 and HEK293 cells with stable incorporation of GAD1 were co-transfected with our miRNA silencing construct (under the control of the CMV promoter). Two different silencing constructs were tested, each harboring a different miRNA directed against GAD1. Transfection with either GAD1 miRNA construct (eGFP/miRNA:Gad1) resulted in a >90% reduction in GAD1 protein at 24 and 48 h after transfection (Figure 1b) in both cell lines. Furthermore, the transfected cells expressed high levels of eGFP, confirming that the eGFP coding potential of the construct was maintained with the addition of the minigene and that excision of the miRNA did not interfere with the translation of eGFP (as predicted).

Generation of NPY BAC-driven GAD1 miRNA-silenced transgenic animals

To accurately direct expression of the GAD1-targeted miRNA to an interneuronal sub-population of interest (NPY-expressing cells), we included the enhancer regions that specify expression of the desired driver gene (NPY). This interneuron subtype comprises approximately 8% of the total neocortical GABAergic interneuron population in mice,35 providing a stringent test of specificity of the BAC-driven silencing strategy. The driver gene is relatively small, facilitating identification of a BAC that contained a centrally located coding region. This feature greatly improved the likelihood of including all of the necessary regulatory regions. We identified BACs using the NCBI genome browser (Build 36), restricting the selection to BACs containing C57BL/6 genomic DNA (RP23/RP24, bacpac.chori.org) to allow generation of C57BL/6 congenic animals. Although BAC clones are ‘tiled' to the genomic sequence by sequencing their ends and identifying the appropriate region of the genome, errors can occur through the curation process or during transfer to the ‘recombineering' bacteria. To confirm the correct, linearly intact arrangement of the genomic DNA in the BACs, restriction mapping was performed using the restriction enzyme SpeI after transformation into the EL250 ‘recombineering' E. coli strain.31 Digests were separated by field inversion gel electrophoresis and band sizes approximated by comparison with a 5-kb molecular weight ladder. All band sizes were as predicted based on NCBI sequence data, confirming the identity and structure of the sequence contained in the BAC after transfer to EL250 cells.

Supercoiled recombinant BAC DNA was injected at approximately 1 ng μl–1 into C57BL/6 embryos by the Vanderbilt Transgenic Mouse/Embryonic Stem Cell Shared Resource. C57BL/6 embryos (rather than C57BL/6 × DBA F1 embryos) were used, which resulted in founder transgenic animals that were congenic C57BL/6 at their inception. This strategy eliminates the confound of cross-strain allelic variation and the need for time-consuming backcrossing before downstream analyses. Founder animals were identified by PCR genotyping using GFP-specific primers. Four founders (Figure 1c) were mated to C57BL/6 animals and transgenic lines were established. GFP expression was detected in the forebrain of two out of four transgenic lines (Figure 1d). Line NPY1 (Tg(Npy-eGFP/miRNA:Gad1)1KM ) was chosen for further characterization, as in the other eGFP-expressing transgenic mouse line (NPY4—Tg(Npy-eGFP/miRNA:Gad1)4KM), as well as several wild-type and transgenic animals from the same mother-developed hydrocephalus. The NPY BAC/GAD1 miRNA transgenic animals from line NPY4 showed identical eGFP expression patterns as the transgenic animals from the NPY1 line. The Tg(Npy-eGFP/miRNA:Gad1)1KM animals expressed consistent and high levels of the minigene carrying the GAD1 microRNA in the frontal cortex (Supplementary Material 2).

Anatomical characterization of NPY BAC/GAD1 miRNA transgenic animals

Normal distribution of the NPY mRNA and protein has been extensively studied in the rodent brain. NPY is expressed at high levels in a small sub-population of hippocampal18, 36 and neocortical interneurons,17, 37, 38, 39 and in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus.40, 41 In brain sections from transgenic animals, strong eGFP fluorescence was detected without immunostaining, although visualization of dendritic arbors markedly improved when the eGFP signal was amplified by immunohistochemical methods (Supplementary Material 3). In a regional survey of the brains derived from Tg(Npy-eGFP/miRNA:Gad1)1KM transgenic animals, we found that eGFP expression correlated with previous descriptions of NPY distribution in wild-type rodents (Figure 1e, left column).19, 35, 39, 42, 43, 44 Coexpression of eGFP with endogenous NPY was also confirmed in double-labeling studies, which showed a >99% co-localization between NPY immunoreactivity and transgenic eGFP expression (Figure 1e, right column). The vast majority of the neocortical interneurons showed morphology of neurogliaform cells. In addition, numerous Martinotti-like cells (Supplementary Materials 4 and 5)19, 43 and occasional double-bouquet interneurons were detected. In the hippocampus, the appearance and localization of cells corresponded to neurogliaform44 and Ivy-type interneurons,42 which are known to express NPY. Overall, the morphology and distribution of the labeled interneurons across the different brain structures suggested that the transgene was specifically expressed in the cell sub-populations that normally express the NPY gene.

After the successful expression of the transgene in a native NPY pattern, we next evaluated the efficacy of the GAD1-directed miRNA in reducing GAD1 expression in the targeted interneurons. Because NPY+ cells make up such a small proportion of total GAD1+ cells in any brain area, tissue measurement of transcript or protein would not be sufficiently sensitive to reveal differences between control and transgenic animals. We thus performed GFP-GAD1 double-fluorescence immunohistochemistry to characterize effective knockdown of protein expression (through gene transcript degradation) in NPY+ cells. There was intense GAD1 immunoreactivity in single-labeled interneurons throughout the cerebral cortex, but in the same sections, virtually none of the GFP-positive (for example, NPY+) cells showed detectable GAD1 expression in the frontal cortex and hippocampus (Figures 1f and g). The absence of GAD1 immunoreactivity was evident in all NPY cell types examined, and there did not seem to be a selective cell loss due to the absence of GAD1 expression in these targeted cells. The cellular selectivity of the knockdown was striking, consistent with successful cell type-specific targeting of reduced GAD1 expression to undetectable levels.

Discussion

In this study we report the development of a new strategy to modulate gene expression in a phenotypic and regional manner, facilitating wide dissemination of a straightforward genetic approach for investigators to establish in vivo disease models based on available pathophysiological data for disease states.5 In schizophrenia, GAD1 disturbances are robust, replicable and represent a core feature of the disease,14, 15 making it a leading candidate for developing transgenic animal models that more closely mimic the disease phenotype. However, GAD1 downregulation in schizophrenia is not uniform across all the interneuronal sub-populations: neurons containing parvalbumin (PARV), somatostatin (SST) and NPY seem to be preferentially affected in a complex pattern.9 Importantly, NPY+ interneurons in the cortex tend to provide inhibitory inputs to the distal dendrites of pyramidal neurons14, 19 decreasing excitability in cortical circuits. As a result, these neurons seem to be critical for learning and memory.45 Furthermore, as NPY+ cells are affected by the disease process of schizophrenia,9, 20, 21, 22, 23 the success in this study in selectively reducing GAD1 expression in these cells provides a unique opportunity to define the role of these cells in cortical pathophysiology that may relate to the disease.

The novel strategy for rapidly generating transgenic mouse lines uses NPY BAC-mediated expression of a synthetic GAD1 miRNA precursor to direct the cell type-specific downregulation of a defined transcript through an endogenous miRNA processing cellular mechanism. Furthermore, due to incorporation of an eGFP coding sequence, the targeted cells are identifiable in both live and fixed tissues. In addition, the components of our targeting construct are modular, which will allow investigators to perform a relatively easy exchange of the miRNA precursor or the sequences homologous to the driver gene.

The advantages of this in vivo gene silencing system are numerous. First, we achieve cell type-specific downregulation of transcripts (in which this specificity depends on the driver gene present on a BAC) and visualize the targeted cells by expressing a reporter gene eGFP. This native fluorescence will facilitate further characterization of the targeted cells with a variety of analytical techniques, including (but not limited to) electrophysiology, morphological analyses, laser dissection microscopy for genomic analysis, double-labeling studies and flow sorting. Second, these transgenic mice are congenic on the C57BL/6 background, and can be generated rapidly (several months) and at a low cost. This allows production of a variety of genetically manipulated animals. Third, to achieve complex gene modulation that more accurately mimics brain disease pathophysiology, the miRNA BAC mice can be crossed with other mouse models, including multiple transgenic lines and various knockout animals. Finally, because of the small size of the silencing miRNAs, this method may allow targeting of specific splice variants, generating splice-variant-specific knockdown animals. We are currently establishing this technology for dissemination.

The in vivo miRNA silencing technology can be further developed in at least three additional directions to study cell-specific silencing of gene expression. First, the construct produced in this study can be placed under the control of an inducible promoter (for example, tetracycline-dependent activators and repressors),46, 47 which would allow the study of the developmental effects of gene silencing in the targeted, GFP-expressing cells (Supplementary Material 6A). Second, the eGFP gene sequence can be exchanged for any Red Fluorescent Protein sequence48, 49 (Supplementary Material 6B), allowing combinatorial breeding of various miRNA-silenced mice, in which the multiple silenced sub-populations of live neurons would be readily identifiable by the use of different fluorescent proteins. Finally, the construct could be further modified to include multiple introns, each harboring miRNAs against different gene products, enabling simultaneous silencing of multiple genes in the same cells with a single construct (Supplementary Material 6c). The methodological advances reported in this study provide opportunities to generate a complex pathophysiology in mice that reflects more accurately unique features of different brain diseases.

In the context of research related to gaining mechanistic insight of the core biological disturbances in schizophrenia, our characterization of the Tg(Npy-eGFP/miRNA:Gad1)1KM animals will allow us to assess the anatomical, biochemical, electrophysiological and behavioral consequences of the GAD1 deficit in the NPY-expressing cells. Furthermore, a combined analysis of the NPY-, PV-, CCK- and SST-BAC-driven GAD1 miRNA-silenced mice (which are currently in production in our laboratory) will greatly contribute to an understanding of the specific role that different interneuronal sub-populations have in cortical inhibition, working memory and cognition. In turn, this will shed light on the mechanisms that cell type-specific GABAergic disturbances have in phenotypic manifestations of schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (K02 MH070786 to KM, R01 MH067234 to KM and R01MH067842 to PL) and Young Investigator Award from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders (to JPE). We are thankful to Dr Ron Emeson for providing advice on the cloning procedures and Drs Christine Konradi (Vanderbilt U), Janos Szabadics (KOKI, Budapest, Hungary) and Csaba Varga (UC Irvine) for advice with immunohistochemistry and comments on the manuscript. We also thank the Vanderbilt Transgenic Mouse/Embryonic Stem Cell Shared resource for generating the transgenic animals.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Molecular Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/mp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Mirnics K, Levitt P, Lewis DA. Critical appraisal of DNA microarrays in psychiatric genomics. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:163–176. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirnics K, Pevsner J. Progress in the use of microarray technology to study the neurobiology of disease. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:434–439. doi: 10.1038/nn1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small GW, Bookheimer SY, Thompson PM, Cole GM, Huang SC, Kepe V, et al. Current and future uses of neuroimaging for cognitively impaired patients. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:161–172. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70019-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Lesnick TG, Maraganore DM, Isacson O. Axon guidance and synaptic maintenance: preclinical markers for neurodegenerative disease and therapeutics. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel TR. From animal models to model animals. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1337–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub RE, Lipska BK, Egan MF, Goldberg TE, Callicott JH, Mayhew MB, et al. Allelic variation in GAD1 (GAD67) is associated with schizophrenia and influences cortical function and gene expression. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:854–869. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weickert CS, Ligons DL, Romanczyk T, Ungaro G, Hyde TM, Herman MM, et al. Reductions in neurotrophin receptor mRNAs in the prefrontal cortex of patients with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:637–650. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Shirakawa O, Toyooka K, Kitamura N, Hashimoto T, Maeda K, et al. Abnormal expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its receptor in the corticolimbic system of schizophrenic patients. Mol Psychiatry. 2000;5:293–300. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Arion D, Unger T, Maldonado-Aviles JG, Morris HM, Volk DW, et al. Alterations in GABA-related transcriptome in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:147–161. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knable MB, Barci BM, Webster MJ, Meador-Woodruff J, Torrey EF.Molecular abnormalities of the hippocampus in severe psychiatric illness: postmortem findings from the Stanley Neuropathology Consortium Mol Psychiatry 20049609–620.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk DW, Austin MC, Pierri JN, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Decreased glutamic acid decarboxylase67 messenger RNA expression in a subset of prefrontal cortical gamma-aminobutyric acid neurons in subjects with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:237–245. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti A, Auta J, Davis JM, Di-Giorgi-Gerevini V, Dwivedi Y, Grayson DR, et al. Decrease in reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase67 (GAD67) expression in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a postmortem brain study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knable MB, Barci BM, Bartko JJ, Webster MJ, Torrey EF. Molecular abnormalities in the major psychiatric illnesses: classification and regression tree (CRT) analysis of post-mortem prefrontal markers. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:392–404. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DA, Hashimoto T, Volk DW. Cortical inhibitory neurons and schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:312–324. doi: 10.1038/nrn1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa E, Davis JM, Dong E, Grayson DR, Guidotti A, Tremolizzo L, et al. A GABAergic cortical deficit dominates schizophrenia pathophysiology. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2004;16:1–23. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v16.i12.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbarian S, Huang HS. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of altered GAD1/GAD67 expression in schizophrenia and related disorders. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2006;52:293–304. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendry SH, Jones EG, DeFelipe J, Schmechel D, Brandon C, Emson PC. Neuropeptide-containing neurons of the cerebral cortex are also GABAergic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:6526–6530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.20.6526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperk G, Hamilton T, Colmers WF. Neuropeptide Y in the dentate gyrus. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:285–297. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagiannis A, Gallopin T, David C, Battaglia D, Geoffroy H, Rossier J, et al. Classification of NPY-expressing neocortical interneurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3642–3659. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0058-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K, Iritani S, Ueno H, Niizato K. Distribution of neuropeptide Y interneurons in the dorsal prefrontal cortex of schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28:379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuromitsu J, Yokoi A, Kawai T, Nagasu T, Aizawa T, Haga S, et al. Reduced neuropeptide Y mRNA levels in the frontal cortex of people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Res Gene Expr Patterns. 2001;1:17–21. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(01)00003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caberlotto L, Hurd YL. Reduced neuropeptide Y mRNA expression in the prefrontal cortex of subjects with bipolar disorder. NeuroReport. 1999;10:1747–1750. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199906030-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen SO, Ekman R, Gottfries CG, Widerlov E, Jonsson S. Reduced concentrations of galanin, arginine vasopressin, neuropeptide Y and peptide YY in the temporal cortex but not in the hypothalamus of brains from schizophrenics. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;83:273–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1991.tb05539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintz N. BAC to the future: the use of bac transgenic mice for neuroscience research. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:861–870. doi: 10.1038/35104049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintz N. Gene expression nervous system atlas (GENSAT) Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:483. doi: 10.1038/nn0504-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory RI, Chendrimada TP, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. Human RISC couples microRNA biogenesis and posttranscriptional gene silencing. Cell. 2005;123:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SL, Miller JD, Ying SY. Intronic microRNA (miRNA) J Biomed Biotechnol. 2006;2006:26818. doi: 10.1155/JBB/2006/26818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying SY, Lin SL. Current perspectives in intronic micro RNAs (miRNAs) J Biomed Sci. 2006;13:5–15. doi: 10.1007/s11373-005-9036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DL, Church DM, Lash AE, Leipe DD, Madden TL, Pontius JU, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:11–16. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert PJ, Campbell DB, Levitt P. Bacterial artificial chromosome transgenic analysis of dynamic expression patterns of regulator of G-protein signaling 4 during development. I. Cerebral cortex. Neuroscience. 2006;142:1145–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EC, Yu D, Martinez de Velasco J, Tessarollo L, Swing DA, Court DL, et al. A highly efficient Escherichia coli-based chromosome engineering system adapted for recombinogenic targeting and subcloning of BAC DNA. Genomics. 2001;73:56–65. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong S, Yang XW.Modification of bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) and preparation of intact BAC DNA for generation of transgenic mice Curr Protoc Neurosci 2005Chapter 5Unit 5 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SM. Dicing and slicing: the core machinery of the RNA interference pathway. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5822–5829. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.08.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed R, Maniatis T. A role for exon sequences and splice-site proximity in splice-site selection. Cell. 1986;46:681–690. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonchar Y, Wang Q, Burkhalter A. Multiple distinct subtypes of GABAergic neurons in mouse visual cortex identified by triple immunostaining. Front Neuroanat. 2007;1:3. doi: 10.3389/neuro.05.003.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray TS, Morley JE. Neuropeptide Y: anatomical distribution and possible function in mammalian nervous system. Life Sci. 1986;38:389–401. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(86)90061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonders CP, Anderson SA. The origin and specification of cortical interneurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:687–696. doi: 10.1038/nrn1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascoli GA, Alonso-Nanclares L, Anderson SA, Barrionuevo G, Benavides-Piccione R, Burkhalter A, et al. Petilla terminology: nomenclature of features of GABAergic interneurons of the cerebral cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:557–568. doi: 10.1038/nrn2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Kubota Y. GABAergic cell subtypes and their synaptic connections in rat frontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 1997;7:476–486. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.6.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danger JM, Tonon MC, Jenks BG, Saint-Pierre S, Martel JC, Fasolo A, et al. Neuropeptide Y: localization in the central nervous system and neuroendocrine functions. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1990;4:307–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1990.tb00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris BJ. Neuronal localisation of neuropeptide Y gene expression in rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1989;290:358–368. doi: 10.1002/cne.902900305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentealba P, Begum R, Capogna M, Jinno S, Marton LF, Csicsvari J, et al. Ivy cells: a population of nitric-oxide-producing, slow-spiking GABAergic neurons and their involvement in hippocampal network activity. Neuron. 2008;57:917–929. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Toledo-Rodriguez M, Gupta A, Wu C, Silberberg G, Luo J, et al. Anatomical, physiological and molecular properties of Martinotti cells in the somatosensory cortex of the juvenile rat. J Physiol. 2004;561 (Part 1:65–90. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.073353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJ, Cauli B, Kovacs ER, Kulik A, Lambolez B, Shigemoto R, et al. Neurogliaform neurons form a novel inhibitory network in the hippocampal CA1 area. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6775–6786. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1135-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen AT, Kanter-Schlifke I, Carli M, Balducci C, Noe F, During MJ, et al. NPY gene transfer in the hippocampus attenuates synaptic plasticity and learning. Hippocampus. 2008;18:564–574. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuschle U, Meyer WK, Thiesen HJ. Tetracycline-reversible silencing of eukaryotic promoters. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1907–1914. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida S, Sakai S, Furuichi T, Hosoda H, Toyota K, Ishii T, et al. Tight regulation of transgene expression by tetracycline-dependent activator and repressor in brain. Genes Brain Behav. 2006;5:96–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell RE, Tour O, Palmer AE, Steinbach PA, Baird GS, Zacharias DA, et al. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7877–7882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082243699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner NC, Campbell RE, Steinbach PA, Giepmans BN, Palmer AE, Tsien RY. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1567–1572. doi: 10.1038/nbt1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherr M, Morgan MA, Eder M. Gene silencing mediated by small interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Curr Med Chem. 2003;10:245–256. doi: 10.2174/0929867033368493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.