Abstract

The attachment of bacteria to host cells and tissues and their subsequent invasion and dissemination are key processes during disease pathogenesis. In this issue of Molecular Microbiology, Jensch and co-workers provide further molecular insight into these events during infection with the Gram-positive bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae. Their characterization of PavB, a bacterial surface protein with orthologues in other streptococci, shows it to bind the extracellar matrix components fibronection and plasminogen by virtue of repetitive sequences designated Streptococcal Surface Repeats (SSURE). In mice, a pavB mutant showed reduced nasopharyngeal colonisation and was attenuated in a lung infection model. As discussed here in the context of the pneumococcus, the study of PavB highlights the central role during microbal pathogenesis of targetting the extracellular matrix by so-called MSCRAMMs (microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules).

Keywords: streptococci, adherence, invasion, PavB, extracellular matrix, MSCRAMMs

Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae attachment to eukaryotic cells and tissues is meditated by a diverse group of bacterial surface molecules that includes cell wall components, choline binding proteins, LPxTG proteins, lipoproteins, and non-classical adhesins such as surface associated enzymes (Hammerschmidt, 2006). While attachment to host surfaces is initially mediated by loose interactions with glycoconjugates (Andersson et al., 1983), avid bacterial adhesion is primarily mediated by specific interactions with host proteins. Tissue-specific distribution of these ligands in mammals, and in turn pneumococcal genetic diversity, therefore impacts the propensity of different S. pneumoniae isolates to establish lung infection and translocate from the lungs to bloodstream and bloodstream to central nervous system (Orihuela et al., 2004, Obert et al., 2006). Herein, we will discuss how adherence to the extracellular matrix in the lungs, in particular that mediated by Pneumococcal Adherence and Virulence Factor B (PavB), described in this issue by Jensch et al. (Jensch et al., 2010), contributes to airway infection and possibly bloodstream invasion. We also take lesson from the observed discrepancy between the publically available genomic sequences for pavB and the actual size of PavB within the sequenced strains. Thus we will highlight the difficulty of working with proteins containing multiple conserved repeats such as the Streptococcal SUrface REpeats (SSURE) domains of PavB.

PavB and other pneumococcal adhesins target the extracellular matrix

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is the part of animal tissue that provides structural support for cells. ECM includes the interstitial matrix, which is found between cells, and the basement membrane upon which epithelial cells rest. The ECM is composed of glycosylated proteins and glycosaminoglycans that together form a fibrous network that stores water and growth factors. Individual components of the ECM include heparin sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, keratin sulfate, hyaluronic acid, collagen, elastin, fibronectin and laminin among others. Proteins attached to the ECM include plasminogen, which when activated to plasmin, cleaves ECM proteoglycans, laminin, fibronectin along with fibrin clots. As in other tissues, ECM is distributed throughout the lungs and serves as a scaffold for cell attachment. Basement membranes are located under bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells, in the pulmonary interstitium, and form a barrier between the vascular endothelium and alveolar cells (Dunsmore & Rannels, 1996). In all, given the ubiquity of ECM within tissues, it should not be surprising that the pneumococcus and other pathogens target the ECM.

As shown by Jensch et al., PavB is a surface exposed, conserved multidomain protein consisting of a signal peptide, cell wall anchoring motif, and numerous repetitive SSURE domains that vary from 5 to 9 depending on the pneumococcal isolate tested. Each SSURE domain is approximately 150 amino acids, but varies by at least one specific nucleotide; which allowed for discrimination and accurate DNA sequencing. PavB was detected in all 23 strains and 13 serotypes tested by Jensch et al., and was previously recognized by Obert et al. to be part of the core genome in a comparative genomic hybridization of 72 different strains (Obert et al., 2006). Orthologues of PavB were detected by Jensch et al. in Streptococcus mitis, Streptococcus agalactiae and Streptococcus gordonii but not in Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus mutants, enterococci, or other bacterial pathogens. Using numerous molecular techniques including ligand overlay assays, surface plasmon resonances, and competitive inhibition assays, Jensch et al., convincingly demonstrate that PavB binds to the ECM components fibronectin and to a lesser extent plasminogen. Avidity for fibronectin and plasminogen increased with the number of SSURE domains present within the recombinant PavB protein tested. In turn deletion of pavB resulted in reduced pneumococcal adherence to host cells in vitro and attenuated virulence in mice. PavB is also of significance as a candidate vaccine antigen by way of its surface location, distribution and sequence conservation between strains, and immunogenicity in humans. Importantly, studies by Papasergi et al., independently examining the same protein under the nomenclature of Plasminogen- and Fibronectin-Binding protein B (PfbB), recapitulate the interaction of PavB with fibronectin and plasminogen and its role as an adhesin (Papasergi et al., 2010). Together these studies expand on the initial work of Bumbaca et al. (Bumbaca et al., 2004).

PavB is only one of many pneumococcal proteins that target the ECM. Surface displayed enolase present on diverse pathogens such as S. pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and the parasite Leishmania mexicana bind to plasminogen, as well as immobilized laminin, fibronectin, and collagens (Bergmann et al., 2001, Antikainen et al., 2007, Carneiro et al., 2004). Pce, PfbA, and PavA, the latter which is not homologous to PavB, also mediate pneumococcal attachment to plasminogen and fibronectin (Attali et al., 2008, Yamaguchi et al., 2008, Holmes et al., 2001). RrgA, the tip protein of the pneumococcal pilus-1 structure has been shown to bind to fibronectin, collagen I, and laminin (Hilleringmann et al., 2008). Interestingly, pneumococcal CbpA (also referred to as PspC), meningococcal PilQ and PorA, and OmpP2 of H. influenzae also target laminin receptor (Orihuela et al., 2009), which is presumably accessible to laminin in the ECM; likewise PsaA binds to E-cadherin (Anderton et al., 2007). Finally, an unknown pneumococcal component binds to vitronectin and this interaction induces microspike formation and invasion (Kostrzynska & Wadstrom, 1992, Bergmann et al., 2009). Thus, similar to the redundancy seen with iron transport systems in pathogens, the presence of multiple ECM adhesins highlights the importance of this trait for the pneumococcus, moreover makes it difficult to determine the relative contribution of individual ECM proteins to colonization and disease processes.

Access to the extracellular matrix proteins during infection

ECM proteins are produced and secreted by resident cells with tissues (Dunsmore & Rannels, 1996). In vitro, sufficient ECM components are secreted by non-polarized cells to permit the adherence of bacteria expressing adhesins that target these factors. For example, deletion of the genes encoding for PavB, enolase, Pce, PfbA, PavA, CbpA, PsaA, PsrP, and RrgA all diminished the ability of S. pneumoniae to adhere to assorted cell lines. In vivo, the same proteins have been shown to facilitate nasopharyngeal colonization and/or the establishment of lower respiratory tract infection. (Jensch et al., 2010, Yamaguchi et al., 2008, Bergmann et al., 2003, Attali et al., 2008, Holmes et al., 2001, Rosenow et al., 1997, Anderton et al., 2007, Rose et al., 2008, Papasergi et al., 2010).

During an infection the host response includes the production and activation of matrix-metalloproteases (MMPs). These enzymes are capable of degrading the extracellular matrix, but are also necessary for processing a number of bioactive molecules. Briefly, MMPs play a major role in tissue remodeling, cell proliferation, apoptosis and the host defense (Page-McCaw et al., 2007). Activation of MMPs during infection may therefore also be a host mechanism for the release of adhered bacteria. In some instances this may be beneficial; for example allowing for mucociliary clearance of the bacteria from the lungs. Alternatively, in other instances may be detrimental, and facilitate spread of the microorganisms within the infected tissues. These conflicting possibilities are exemplified by findings showing that MMP-8 KO mice had more severe infection during Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced periodontitis (Kuula et al., 2009), and studies with Chlamydia muridarum infected mice given MMP inhibitors that had lower isolation rates from the upper genital tract (Imtiaz et al., 2006). Interestingly, P. gingivalis binds to collagen-1, the target of MMP-8 which may contribute to the phenotype described above (Pierce et al., 2009). Currently, susceptibility of MMP KO mice to pneumococcal pneumonia is not known. However MMP-9 KO mice had greater disease severity when tested in a mouse model of bacterial meningitis (Bottcher et al., 2003).

Importantly, the pneumococcus also targets ECM proteins with its own collection of proteinases or sequesters host-derived proteolytic activity such as plasmin, which is known to activate MMPs (Bergmann & Hammerschmidt, 2007, Bergmann et al., 2005). Virulence determinants such as CbpG, Pce, and ZmpC have been shown by numerous investigators to degrade gelatin, fibronectin, and plasminogen moreover to facilitate migration through the ECM in vitro (Mann et al., 2006, Lagartera et al., 2005, Camilli et al., 2006, Chiavolini et al., 2003, Attali et al., 2008). The specific role of these enzymes during infection is multifactorial and difficult to dissect. Many of these proteinases also cleave host molecules such as MMP-9 and immunoglobulin A that have been demonstrated to affect the host-defense (Oggioni et al., 2003). Of note, mutants deficient in these genes have also been demonstrated to be attenuated in vivo.

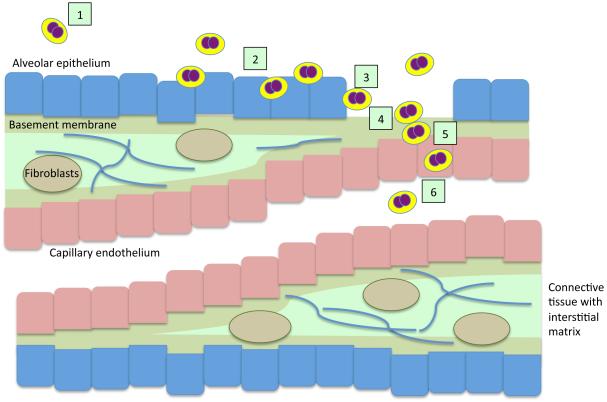

In areas of the lungs where gas diffusion occurs, the basement membranes of alveolar epithelial cells capillary endothelial are shared to minimize thickness and facilitate gas diffusion. These areas do not contain interstitial cells (Dunsmore & Rannels, 1996). In these areas, as bacterial infection progresses, and alveolar epithelial cells are exposed to noxious agents such as pneumococcal pneumolysin, hydrogen peroxide, and bacterial cell wall components, alveolar cell death will most likely result in greater exposure of the basement membrane and the ECM proteins that are found between these cells. Thus ECM-binding proteins such as PavB may also play an important role in positioning the bacteria next to capillary endothelial cells for subsequent blood stream invasion. At this site, the aforementioned bacterial proteases or the activated host proteases may degrade ECM and facilitate development of bacteremia by enhancing access to the basolateral surface of endothelial cells. A summary of how binding to ECM may contribute to pneumococcal pathogenesis in the lung is detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Model of how binding to ECM may facilitate development of pneumococcal pneumonia and disease progression.

(1) Once aspirated into the lungs, pneumococci attach to epithelial cells (2) via loose interactions with glycoconjugates, apical surface expressed proteins, as well as extracellular matrix components that are accessible between cells and in low amounts on the apical side of the cell. (3) As the bacteria replicate and cause tissue damage and epithelial cell death, they presumably gain greater accessibility to ECM components that are located between host cells as well as in the underlying the basement membrane. (4) In areas where gas exchange occurs, binding to ECM components of the basement membrane facilitates access to the vascular endothelial cells that form the capillaries. (5-6) Due to the release of bacterial proteases, activation of host proteases that target the ECM including MMPs, vascular leakage due to inflammation, and receptor-mediated endocytosis, the bacteria are able to translocate into the bloodstream.

Finally, one unexplored but potentially important role for ECM binding proteins might be during parapneumonic empyema (PPE). PPE occurs primarily in children and is characterized as a serous, often bloody, purulent accumulation of bacteria and cells outside of the lungs but within the pleural space. While the underlying mechanisms for empyema formation are not known, the incidence of PPE in children with pneumonia has increased during the last decade (Byington et al., 2009, Li & Tancredi, 2009). Fibronectin and plasminogen binding proteins such as PavB may be important for PPE formation because the composition of pleural effusions have been shown to contain high levels of fibrinogen and plasminogen (Philip-Joet et al., 1995, Michelin et al., 2008) and fibrin clots are a major component of the effusions (Salzberg, 1956).

Discrepancy between genomic sequence data and actual PavB size

In their bioinformatic analysis of PavB, Jensch et al. analyzed the sequence of pavB in six pneumococcal strains with annotated genomes. For four of these, TIGR4, G54, D39 and R6x, a discrepancy was observed between the actual number of SSURE repeats (five to nine repeats) and the published number in the annotated genomes (four to six repeats). Despite the high conservation of these repetitive elements, Jensch et al. determined the true number of SSURE repeats by taking into account single nucleotide substitutions within individual repeats and using highly specific ssure primers for their molecular approaches. By using this technique, they were also able to determine the location of the additional repeats and provided a corrected full-length sequence of the TIGR4 PavB. This discrepancy reflects the difficulties of sequencing and working with genes containing repetitive elements. Importantly, as different sequencing centers were responsible for these annotated genomes, this was not an isolated event.

In the past, a similar problem was encountered when sequencing the adhesin psrP; requiring the insertion of placeholder sequences (Tettelin et al., 2002). The SRR2 domain of TIGR4 PsrP consists of 539 24-bp imperfect repeats. The actual size of PsrP in different strains is near impossible to ascertain, as the protein is glycosylated, and thereby runs at significantly higher size on separation gels (Shivshankar et al., 2009), moreover the repetitive elements make normal sequencing impossible. Clearly a degree of skepticism and independent confirmation of the sequence data are warranted when working on genes with repetitive elements.

Summary

Binding to the ECM is a conserved pathogenic mechanism. For the pneumococcus, multiple surface expressed adhesins, including PavB, target the ECM and when deleted results in an attenuated phenotype. How bacterial adhesion to ECM proteins and their targeting by proteases is coordinated and contributes to disease at the alveolar-blood barrier is currently not well understood. Nonetheless, binding to ECM components in the basement membrane of alveoli most likely facilitates subsequent bloodstream invasion by the pneumococcus and more severe infection.

References

- Andersson B, Dahmen J, Frejd T, Leffler H, Magnusson G, Noori G, et al. Identification of an active disaccharide unit of a glycoconjugate receptor for pneumococci attaching to human pharyngeal epithelial cells. J Exp Med. 1983;158:559–570. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.2.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderton JM, Rajam G, Romero-Steiner S, Summer S, Kowalczyk AP, Carlone GM, et al. E-cadherin is a receptor for the common protein pneumococcal surface adhesin A (PsaA) of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb Pathog. 2007;42:225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antikainen J, Kuparinen V, Lahteenmaki K, Korhonen TK. pH-dependent association of enolase and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of Lactobacillus crispatus with the cell wall and lipoteichoic acids. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:4539–4543. doi: 10.1128/JB.00378-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attali C, Frolet C, Durmort C, Offant J, Vernet T, Di Guilmi AM. Streptococcus pneumoniae choline-binding protein E interaction with plasminogen/plasmin stimulates migration across the extracellular matrix. Infect Immun. 2008;76:466–476. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01261-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann S, Hammerschmidt S. Fibrinolysis and host response in bacterial infections. Thromb Haemost. 2007;98:512–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann S, Lang A, Rohde M, Agarwal V, Rennemeier C, Grashoff C, et al. Integrin-linked kinase is required for vitronectin-mediated internalization of Streptococcus pneumoniae by host cells. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:256–267. doi: 10.1242/jcs.035600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann S, Rohde M, Chhatwal GS, Hammerschmidt S. alpha-Enolase of Streptococcus pneumoniae is a plasmin(ogen)-binding protein displayed on the bacterial cell surface. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:1273–1287. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann S, Rohde M, Preissner KT, Hammerschmidt S. The nine residue plasminogen-binding motif of the pneumococcal enolase is the major cofactor of plasmin-mediated degradation of extracellular matrix, dissolution of fibrin and transmigration. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:304–311. doi: 10.1160/TH05-05-0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann S, Wild D, Diekmann O, Frank R, Bracht D, Chhatwal GS, et al. Identification of a novel plasmin(ogen)-binding motif in surface displayed alpha-enolase of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:411–423. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottcher T, Spreer A, Azeh I, Nau R, Gerber J. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 deficiency impairs host defense mechanisms against Streptococcus pneumoniae in a mouse model of bacterial meningitis. Neurosci Lett. 2003;338:201–204. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01406-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumbaca D, Littlejohn JE, Nayakanti H, Rigden DJ, Galperin MY, Jedrzejas MJ. Sequence analysis and characterization of a novel fibronectin-binding repeat domain from the surface of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Omics. 2004;8:341–356. doi: 10.1089/omi.2004.8.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byington CL, Hulten KG, Ampofo K, Sheng X, Pavia AT, Blaschke AJ, et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Pediatric Pneumococcal Empyema 2001-2007. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;16:16. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01200-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilli R, Pettini E, Del Grosso M, Pozzi G, Pantosti A, Oggioni MR. Zinc metalloproteinase genes in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae: association of the full array with a clonal cluster comprising serotypes 8 and 11A. Microbiology. 2006;152:313–321. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28417-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro CR, Postol E, Nomizo R, Reis LF, Brentani RR. Identification of enolase as a laminin-binding protein on the surface of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:604–608. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiavolini D, Memmi G, Maggi T, Iannelli F, Pozzi G, Oggioni MR. The three extra-cellular zinc metalloproteinases of Streptococcus pneumoniae have a different impact on virulence in mice. BMC Microbiol. 2003;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmore SE, Rannels DE. Extracellular matrix biology in the lung. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:L3–27. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.1.L3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt S. Adherence molecules of pathogenic pneumococci. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilleringmann M, Giusti F, Baudner BC, Masignani V, Covacci A, Rappuoli R, et al. Pneumococcal pili are composed of protofilaments exposing adhesive clusters of Rrg A. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000026. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes AR, McNab R, Millsap KW, Rohde M, Hammerschmidt S, Mawdsley JL, et al. The pavA gene of Streptococcus pneumoniae encodes a fibronectin-binding protein that is essential for virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:1395–1408. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imtiaz MT, Schripsema JH, Sigar IM, Kasimos JN, Ramsey KH. Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases protects mice from ascending infection and chronic disease manifestations resulting from urogenital Chlamydia muridarum infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5513–5521. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00730-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensch I, Gamez G, Rothe M, Ebert S, Fulde M, Somplatzki D, et al. PavB is a surface-exposed adhesin of Streptococcus pneumoniae contributing to nasopharyngeal colonization adn airways infections. Mol Microbiol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostrzynska M, Wadstrom T. Binding of laminin, type IV collagen, and vitronectin by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Zentralbl Bakteriol. 1992;277:80–83. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80874-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuula H, Salo T, Pirila E, Tuomainen AM, Jauhiainen M, Uitto VJ, et al. Local and systemic responses in matrix metalloproteinase 8-deficient mice during Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced periodontitis. Infect Immun. 2009;77:850–859. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00873-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagartera L, Gonzalez A, Hermoso JA, Saiz JL, Garcia P, Garcia JL, et al. Pneumococcal phosphorylcholine esterase, Pce, contains a metal binuclear center that is essential for substrate binding and catalysis. Protein Sci. 2005;14:3013–3024. doi: 10.1110/ps.051575005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S-TT, Tancredi DJ. Empyema hospitalizations increased in US children despite pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Pediatrics. 2009;125:26–33. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann B, Orihuela C, Antikainen J, Gao G, Sublett J, Korhonen TK, et al. Multifunctional role of choline binding protein G in pneumococcal pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2006;74:821–829. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.821-829.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelin E, Snijders D, Conte S, Dalla Via P, Tagliaferro T, Da Dalt L, et al. Procoagulant activity in children with community acquired pneumonia, pleural effusion and empyema. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2008;43:472–475. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obert C, Sublett J, Kaushal D, Hinojosa E, Barton T, Tuomanen EI, et al. Identification of a Candidate Streptococcus pneumoniae core genome and regions of diversity correlated with invasive pneumococcal disease. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4766–4777. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00316-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oggioni MR, Memmi G, Maggi T, Chiavolini D, Iannelli F, Pozzi G. Pneumococcal zinc metalloproteinase ZmpC cleaves human matrix metalloproteinase 9 and is a virulence factor in experimental pneumonia. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:795–805. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orihuela CJ, Gao G, Francis KP, Yu J, Tuomanen EI. Tissue-specific contributions of pneumococcal virulence factors to pathogenesis. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1661–1669. doi: 10.1086/424596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orihuela CJ, Mahdavi J, Thornton J, Mann B, Wooldridge KG, Abouseada N, et al. Laminin receptor initiates bacterial contact with the blood brain barrier in experimental meningitis models. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1638–1646. doi: 10.1172/JCI36759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page-McCaw A, Ewald AJ, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:221–233. doi: 10.1038/nrm2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papasergi S, Garibaldi M, Tuscano G, Signorino G, Ricci S, Peppoloni S, et al. Plasminogen- and fibronectin-binding protein B is involved in the adherence of Streptococcus pneumoniae to human epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7517–7524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.062075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip-Joet F, Alessi MC, Philip-Joet C, Aillaud M, Barriere JR, Arnaud A, et al. Fibrinolytic and inflammatory processes in pleural effusions. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:1352–1356. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08081352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce DL, Nishiyama S, Liang S, Wang M, Triantafilou M, Triantafilou K, et al. Host adhesive activities and virulence of novel fimbrial proteins of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 2009;77:3294–3301. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00262-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose L, Shivshankar P, Hinojosa E, Rodriguez A, Sanchez CJ, Orihuela CJ. Antibodies against PsrP, a novel Streptococcus pneumoniae adhesin, block adhesion and protect mice against pneumococcal challenge. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:375–383. doi: 10.1086/589775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenow C, Ryan P, Weiser JN, Johnson S, Fontan P, Ortqvist A, et al. Contribution of novel choline-binding proteins to adherence, colonization and immunogenicity of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:819–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1997.mmi494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzberg AM. Streptococcal enzymes in the treatment of pleural empyema. South Med J. 1956;49:50–53. doi: 10.1097/00007611-195601000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivshankar P, Sanchez C, Rose LF, Orihuela CJ. The Streptococcus pneumoniae adhesin PsrP binds to Keratin 10 on lung cells. Mol Microbiol. 2009;73:663–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06796.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tettelin H, Masignani V, Cieslewicz MJ, Eisen JA, Peterson S, Wessels MR, et al. Complete genome sequence and comparative genomic analysis of an emerging human pathogen, serotype V Streptococcus agalactiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12391–12396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182380799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi M, Terao Y, Mori Y, Hamada S, Kawabata S. PfbA, a novel plasmin- and fibronectin-binding protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae, contributes to fibronectin-dependent adhesion and antiphagocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:36272–36279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807087200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]