Summary

Objective

To measure in vivo thicknesses of the facet joint subchondral bone across genders, age groups, with or without low back pain symptom groups and spinal levels.

Methods

Lumbar (L1–L2 to L5-S1) magnetic resonance (MR) imaging was performed in 81 subjects (41 males and 40 females, mean age 37.6 years). Thicknesses of the subchondral bone were measured in 1,620 facet joints using the MR images with custom-written image processing algorithms together with a multi-threshold segmentation technique using each facet joint’s middle axial-slice. This method was validated with 12 cadaver facet joints, scanned with both MR and micro-computed tomography images.

Results

An overall average thickness value for the 1,620 analyzed joints was measured as 1.56 ± 0.01 mm. The subchondral bone thickness values showed significant increases with successive lower spinal levels in the subjects without low back pain. The facet joint subchondral bone thickness in asymptomatic females was much smaller than in asymptomatic males. Mean subchondral bone thickness in the superior facet was greater than that in the inferior facet in both female and male asymptomatic subjects.

Conclusions

This study is the first to quantitatively show subchondral bone thickness using a validated MR-based technique. The subchondral bone thickness was greater in asymptomatic males and increased with each successive lower spinal level. These findings may suggest that the subchondral bone thickness increases with loading. Furthermore, the superior facet subchondral bone was thicker than the inferior facet in all cases regardless of gender, age or spinal level in the subjects without low back pain. More research is needed to link subchondral bone microstructure to facet joint kinematics and spinal loads.

Keywords: Subchondral Bone, Facet Joint, MRI, Image Processing

Introduction

Facet joints are synovial articulations and undergo degenerative changes similar to those of other weight-bearing joints. Osteoarthritis of the facet joint has been considered as a potential source of low back pain and disability. It is said that facet joints affect up to 15% of low back pain patients1. In recent years, the facet joint has garnered much attention because of the myriad new technologies being developed or marketed to preserve lumbar spinal motion, including artificial discs, facet joint arthroplasty, flexible rod with pedicle screw systems, etc. However, relatively little is known about the degenerative changes in the facet joint. The etiology of pain arising from the facet joint remains elusive. The capsule, subchondral bone, and synovium all could be a potential source. An up-to-date knowledge of this subject can be helpful in the development of diagnostic techniques and in the prevention of lumbar facet joint osteoarthritis and low pack pain and can assist in the determination of future research goals.

The subchondral bone provides a linkage of the hyaline cartilage and cancellous bone. It has been regarded as a morphological and mechanical unit and recognized to play an important role in attenuating the impact forces typically encountered during dynamic joint loading. subchondral bone is also a sensitive measurement used for evaluation of osteoarthritis2. Only a few studies have focused on the subchondral bone of lumbar facet joints and such information can be used to study the facetogenic low back pain. The purpose of this study was to accurately evaluate the thickness of subchondral bone in human using MR imaging. Our hypothesis was that subchondral bone thickness differs by gender, age and spinal levels.

Materials and methods

SUBJECTS

A total of 81 volunteers (40 males and 41 females, age range 22–59 years, mean 37.6 years), were studied. All subject signed an approved informed consent form (IRB Approval No. 00042801) were asked clinical questions about their symptoms. Subjects with chronic low back pain (n = 24) were categorized as “symptomatic” subjects. The remaining 57 subjects were categorized as “asymptomatic.” Each subject was screened by the authors for pre-existing lumbar spine pathology and pain episodes to assign each subject either to the asymptomatic group or the symptomatic group. Exclusion criteria for the asymptomatic group were low back pain, previous spinal surgery, history of low back pain, age over 60 years, obesity, claustrophobia or other contraindication to magnetic resonance (MR) imaging. Inclusion criteria for the symptomatic group were recurrent pain in the low back pain with at least two episodes of at least 6 weeks brought on by modest physical exertion. Exclusion criteria for the symptomatic group were prior surgery for back pain, age over 60 years, claustrophobia or other contraindication to MR imaging, severe osteoporosis, severe disc collapse at multiple levels, severe central or spinal stenosis, destructive process involving the spine, litigation or compensation proceedings, extreme obesity, congenital spine defect, previous spinal injury.

MR IMAGING

MR imaging was performed with proton density (PD)-weighted sequences (repeat time/echo time TR/TE: 2000/33 milliseconds, 18.0 cm field of view, 512 × 512 matrix, 0.352 mm pixel size) using a 1.5 T MR imaging scanner (Signa, General Electric, Milwaukee, WI). Scans were at 2.67-mm intervals, and at each intervertebral disc the scanner gantry was tilted to produce a scan through the plane of disc. The images were stored in DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine) format then transferred to personal computers for analysis.

SUBCHONDRAL BONE THICKENESS MEASUREMENT

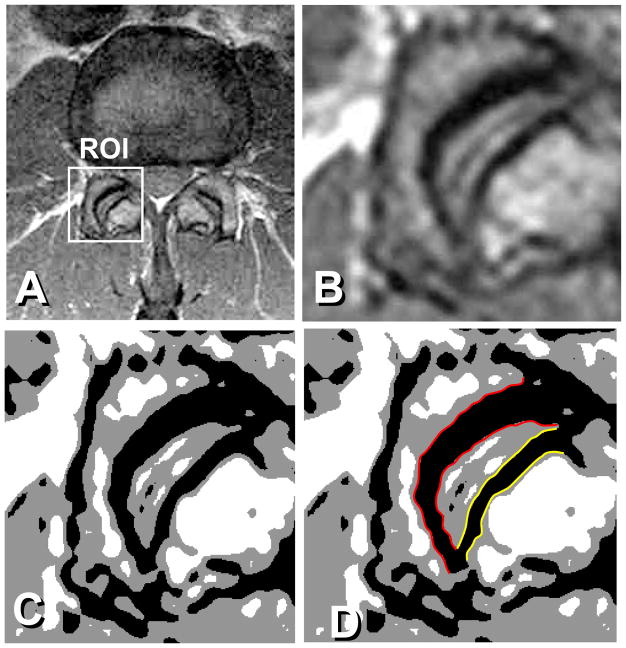

A total of 1,620 articular processes from L1–L2 to L5-S1 were examined. At each disc level, a slice just proximal to the appearance of the pedicle was selected for analyses. The MR images were analyzed by custom software written in Microsoft Visual C++ 2005 with Microsoft Foundation Class (MFC) programming environment (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA). In order to obtain precise and well-contrasted pictures, a Region of Interest (ROI) was set at each facet joint interactively on the computer screen and enlarged 800% using a bilinear-interpolation, size- conversion algorithm (Fig. 1, Fig. 2-A,-B)3. After the size conversion, the space resolution increased to 0.044 mm. Gray levels of subchondral bone region and cartilage and bone marrow regions nearby the subchondral bone were measured interactively by setting a ROI of 4 × 4 pixels at each region, and the subchondral bone region was defined by a multi-threshold technique (Fig. 2-C). The contour lines of the subchondral bone were traced by qualified orthopedic surgeons (Fig. 2-D) using a pen tablet (Wacom Intuos 3, Wacom, Saitama, Japan). Each line consisted of approximately 100 points. The thickness of the subchondral bone layer was defined as the least distance between the inferior and superior contour of subchondral bone. The subchondral bone thickness was measured at each point on the contour line throughout the subchondral bone area (Fig 3). Therefore, the subchondral bone thickness measurements were performed at approximately 100 points for each articular surface. The mean thickness of the subchondral bone was calculated from the least distances and used for the analysis.

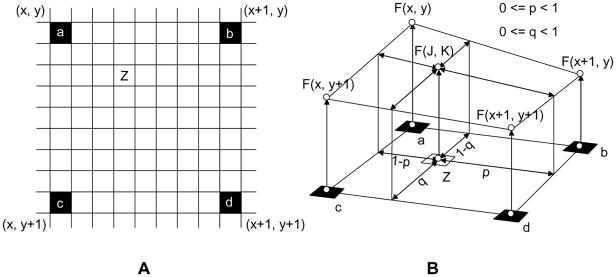

Figure 1.

800% size conversion using a bilinear-interpolation algorithm. A: black pixel (a, b, c, and d); original MR image pixel, white pixel; interpolated pixel. B: bilinear interpolation algorithm. F(x, y), F(x+1, y), F(x+1, y+1) and F(x, y+1) are MR signal intensities of the pixel a, b, c and d, respectively. The MR signal intensity of an arbitrary pixel (Z), F(J, K) is calculated the following equation; F(J, K) = F(x, y)(1−p)(1−q) + F(x+1)p(1−q) + F(x, y+1)(1−p)q + F(x+1, y+1)pq.

Figure 2.

A: Original MR image, ROI for a facet joint. B: Image enlarged 800% using the bilinear-interpolation size-conversion algorithm. Image size; 256 × 256. C: Segmentation of the subchondral bone by a multi-threshold technique. D: Red outline shows the superior facet joint subchondral bone contour, and the yellow outline depicts the inferior facet joint subchondral bone contour.

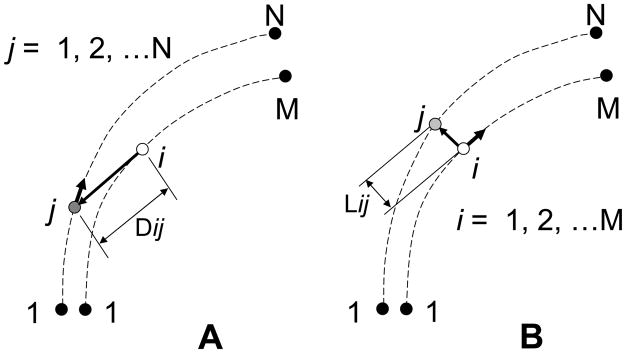

Figure 3.

Definition of the subchondral bone thickness by the linear distance algorithm. A: Distances, Dij, between a fixed point, i, on the line 1-M and a moving point, j, on the line 1-N were calculated through the point 1 to point N. B: The least distance at the point i, Lij, was determined from the minimum Dij. The procedure A was repeated until the point i reached to the point M.

VALIDATION OF SUBCHONDRAL BONE THICKENESS MEASUREMENT

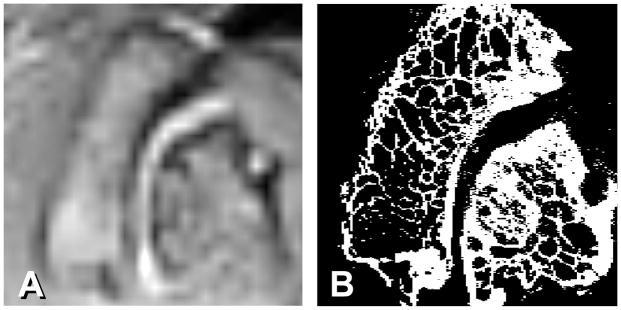

In order to confirm the accuracy of the subchondral bone thickness measurement in MR images, lumbar facet joints from a human cadaveric spines were used to undergo both MR imaging with the same PD sequence used for in vivo study and micro-CT scan with a resolution of 30 μm (Scanco μCT40, Scanco Medical, Brüttisellen, Switzerland) (Fig. 4). Both imaging methods to show the thickness of subchondral bone were validated by applying them to the same image slice using 12 pairs (4 motion segments at L2–L3 and 8 motion segments at L4–L5) of human cadaveric facet joints (mean age 77.6 ± 13.0 years).

Figure 4.

Comparison between A) MR PD image enlarged 800% and B) micro-CT image taken from a cadaveric human L2–L3 facet joint.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

SPSS for Windows (SPSS Version 16, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and StatsDirect (Version 2.7.8, StatsDirect Ltd., Altrincham, England) were used for data management and statistical analysis. Since histograms of the measurements were consistent with statistically normal or approximately normal distributions, parametric statistical methods were appropriate. A 0.05 significance level was used for all statistical tests. All tests were two-sided. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

The measurements for the 81 subjects were analyzed as follows. To avoid violations of the assumption of independence, the subject and not the facet joint was the unit of analysis. For each level, paired t tests found no statistically significant differences between the right and left superior measurements or between the right and left inferior measurements. The right and left measurements were, therefore, averaged and the averages were analyzed. A repeated-measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with the between-subjects factors gender and symptoms (symptomatic or asymptomatic), the within-subjects factors level (L1–L2 through L5/S1) and region (superior or inferior), and the covariate age was carried out. Because Mauchly’s test found violations of the sphericity assumption for the variance-covariance matrix, the multivariate approach (with Pillai’s trace) was used. When statistically significant interactions were found, further analyses were done using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), pooled-variance and separate-variance t tests, paired t tests, scatterplots, and Pearson correlation coefficients. Levene’s test was used to test the hypothesis of equal variances for the pooled-variance t test.

In the validation study, the cadaver facet joint measurements for each side and region combination were independent because only one joint was obtained from each cadaver. Scatterplots, Pearson correlation coefficients, bivariate regression, and paired t tests were obtained to compare the MR and micro-CT measurements.

Results

In the validation study of the subchondral bone measurements, the MR and micro-CT derived subchondral bone thickness means averaged over both sides and both regions were 1.92 ± 0.37 mm and 1.86 ± 0.36 mm, respectively. Only one statistically significant difference was found between the MR and micro-CT mean measurements when these were compared to each other for each side and region combination, a small difference between the right inferior MR and micro-CT means: 1.65 ± 0.21 mm and 1.58 ± 0.19 mm, respectively (p = 0.041).

The Pearson correlation coefficients between the MR and micro-CT subchondral bone thickness measurements were: right superior, r = 0.75 (p = 0.005); right inferior, r = 0.84 (p = 0.001); left superior, r = 0.76 (p = 0.004); and left inferior, r = 0.66 (p = 0.019). When bivariate regression analyses were done separately for each side and region combination, with the micro-CT subchondral bone thickness as the dependent variable and the MR subchondral bone thickness as the independent variable, all of the 95% confidence intervals for the slope included 1.

Repeated measures ANCOVA for the 81 subjects found a statistically significant five-way interaction between gender, symptoms, level, region, and age (p = 0.032). This result indicates that all of these factors and the age covariate affect the subchondral bone thickness measurements and do so interactively; that is, the effect of each factor or covariate depends on the others.

Table 1 shows the statistically significant Pearson correlations between age and subchondral bone thickness, considered separately for each of the different combinations of level, region, gender, and symptoms. All of the correlations were positive, and only one statistically significant correlation was found for females. The significant associations were found to be more frequent in the male superior facets (Pearson correlation coefficients in bold text, Table 1).

Table 1.

Pearson correlations (p-values) between age and subchondral bone thickness by level, region, gender, and symptoms. Coefficients for statistically significant differences shown in bold

| Level | Female |

Male |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatic (n = 14) | Asymptomatic (n = 27) | Symptomatic (n = 10) | Asymptomatic (n = 30) | |

| L1–L2 | ||||

| Superior | 0.40 (0.16) | 0.024 (0.91) | 0.81 (0.004) | 0.41 (0.023) |

| Inferior | 0.010 (0.97) | 0.38 (0.052) | 0.63 (0.049) | 0.014 (0.94) |

| L2–L3 | ||||

| Superior | 0.21 (0.47) | 0.017 (0.93) | 0.80 (0.006) | 0.37 (0.044) |

| Inferior | −0.0068 (0.98) | 0.33 (0.096) | 0.48 (0.16) | 0.013 (0.95) |

| L3–L4 | ||||

| Superior | −0.12 (0.68) | 0.25 (0.21) | 0.72 (0.019) | 0.26 (0.17) |

| Inferior | 0.27 (0.35) | 0.27 (0.17) | 0.37 (0.30) | −0.036 (0.85) |

| L4–L5 | ||||

| Superior | 0.28 (0.33) | −0.11 (0.60) | −0.11 (0.76) | 0.42 (0.023) |

| Inferior | −0.092 (0.76) | 0.42 (0.031) | −0.24 (0.51) | 0.16 (0.38) |

| L5-S1 | ||||

| Superior | 0.22 (0.45) | 0.27 (0.17) | 0.31 (0.38) | 0.29 (0.12) |

| Inferior | 0.041 (0.89) | 0.12 (0.55) | 0.018 (0.96) | −0.017 (0.93) |

When the levels were compared with respect to the superior region subchondral bone thickness separately for each of the different combinations of gender and symptoms, the level differences were statistically significant for all combinations. The mean superior subchondral bone thickness usually increased with each successive lower spinal level. When the levels were compared with respect to the inferior subchondral bone thickness separately for each of the different combinations of gender and symptoms, the level differences were statistically significant only for females and males without symptoms, and there was no clear pattern of increasing subchondral thickness with lower spinal levels (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean ± standard deviation and 95% confidence intervals of superior and inferior subchondral bone thickness by level, gender, and symptoms

| Level and Site | Female |

Male |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatic*, ** (n = 14) | Asymptomatic*,** (n = 27) | Symptomatic§, §§ (n = 10) | Asymptomatic§, §§ (n = 30) | |

| (Superior; p = 0.027)a | (Superior; p < 0.001)a | (Superior; p < 0.001)a | (Superior; p < 0.001)a | |

| (Inferior; p = 0.18)b | (Inferior; p < 0.001) b | (Inferior; p = 0.82)b | (Inferior: p = 0.039) b | |

| L1–L2 | ||||

| Superior | 1.45 ± 0.25 [1.32; 1.58] | 1.39 ± 0.16c, d [1.33,1.45] | 1.63 ± 0.31 [1.43; 1.82] | 1.59 ± 0.23d [1.51; 1.67] |

| Inferior | 1.38 ± 0.21 [1.27; 1.49] | 1.22 ± 0.19c, d [1.15; 1.29] | 1.56 ± 0.26 [1.40; 1.72] | 1.38 ± 0.29d [1.28; 1.49] |

| L2–L3 | ||||

| Superior | 1.46 ± 0.24c [1.34; 1.58] | 1.56 ± 0.26c, d [1.46; 1.66] | 1.82 ± 0.26d [1.66; 1.98] | 1.72 ± 0.31d [1.61; 1.83] |

| Inferior | 1.46 ± 0.25c [1.33; 1.59] | 1.33 ± 0.18c, d [1.26; 1.39] | 1.67 ± 0.21d [1.54; 1.80] | 1.49 ± 0.23d [1.41; 1.57] |

| L3–L4 | ||||

| Superior | 1.64 ± 0.29d [1.49; 1.79] | 1.69 ± 0.29d [1.59; 1.80] | 1.79 ± 0.46 [1.51; 2.08] | 1.83 ± 0.31d [1.72; 1.94] |

| Inferior | 1.39 ± 0.27c, d [1.25; 1.52] | 1.27 ± 0.19c, d [1.20; 1.35] | 1.66 ± 0.17 [1.55; 1.77] | 1.57 ± 0.26d [1.48; 1.67] |

| L4–L5 | ||||

| Superior | 1.72 ± 0.36d [1.53; 1.91] | 1.69 ± 0.33c, d [1.56; 1.81] | 1.97 ± 0.28d [1.80; 2.15] | 1.97 ± 0.37d [1.84; 2.11] |

| Inferior | 1.47 ± 0.18d [1.38; 1.57] | 1.35 ± 0.16c, d [1.29; 1.41] | 1.62 ± 0.16d [1.52; 1.71] | 1.51 ± 0.28d [1.41; 1.61] |

| L5-S1 | ||||

| Superior | 1.79 ± 0.40d [1.58; 2.00] | 1.63 ± 0.26c, d [1.53; 1.73] | 2.12 ± 0.46d [1.83; 2.41] | 1.95 ± 0.38d [1.81; 2.09] |

| Inferior | 1.25 ± 0.24c, d [1.13; 1.37] | 1.21 ± 0.20c, d [1.14; 1.29] | 1.64 ± 0.21d [1.51; 1.77] | 1.48 ± 0.26d [1.39; 1.58] |

p-values for asymptomatic vs. symptomatic comparisons in specific groups:

p = 0.67 Female, Superior;

p < 0.001 Female, Inferior;

p = 0.37 Male, Superior;

p < 0.001 Male, Inferior.

For all superior and inferior facets as a whole: p = 0.03 (F), and p = 0.02 (M), respectively.

For comparison between levels, superior.

For comparison between levels, inferior.

p<0.05 compared to males at the same level, site and symptoms.

p<0.05 compared to opposite site within the same facet joint.

In the asymptomatic group, the subchondral bone was thicker for the males in all but the L4–L5 levels for the superior facets, and in all the inferior facets. For asymptomatic females and males, the mean subchondral bone thickness was significantly lower in the inferior region than in the superior region for all levels. Significantly lower inferior subchondral bone thickness means compared to the corresponding superior means were also found at most levels for symptomatic females and males (Table 2).

Discussion

The subchondral bone has been recognized as a morphological unit which provides a linkage of the hyaline cartilage and cancellous bone and as a mechanical unit to play an important role in attenuating the axial impact forces typically encountered during dynamic joint loading4–6. Changes in structure and density of the subchondral bone have been considered to reflect loading history and progression of osteoarthritis7,8. It has been reported that thickening of subchondral bone occurs earlier than narrowing of the joint gap width in the osteoarthritic changes of the joint2. However, most previous investigations of the subchondral bone have dealt with large joints such as the hip or knee joints, and there have been relatively few reports about small joints such as the facet joint.

Detailed morphology of the subchondral bone in large synovial joints has been investigated in vivo using plain radiography, CT and MR imaging. While standard plain radiography has a spatial resolution of approximately 0.2 mm, magnification radiography or macroradiography has a spatial resolution of 25 to 50 μm 2. Despite the high spatial resolution these techniques provide, the orientation of an x-ray beam in reference to the joint surface is critical for accurate evaluation of the subchondral bone morphology in these techniques, as the beam needs to be tangential to the joint surface for the measurement of the subchondral bone thickness. Therefore, detailed evaluation of the subchondral bone morphology for the facet joint using these techniques would be difficult due to complex three-dimensional orientation of the facet joint. CT and MR imaging modalities, which provide cross sectional images, have been used for characterization of the geometry of the facet joint. Quantitative measurements of the subchondral bone thickness of the facet joint using CT or MR imaging, however, are limited in the literature. The CT osteoabsorptiometry method has been applied to the facet joint to evaluate bone density distribution in the subchondral bone of the facet joint8–10. Although this technique allows measuring bone density as a function of the distance from the curved joint surface, it does not provide the subchondral bone thickness due to gradient changes in bone density from the joint surface. Fujiwara et al. evaluated the subchondral bone of the lumbar spine using T2-weighted MR images, but they only used grading system for the evaluation and no information on the subchondral bone thickness was reported11.

In the current study, we used proton density (PD)-weighted images for the measurement of the subchondral bone thickness of the facet joint. The PD sequences have been often used for musculoskeletal examinations with small Field of View (FOV) since this sequence provides a good contrast-to-noise ratio12. In the PD sequence, MR signal intensities of the articular cartilage, subchondral bone, and bone marrow were intermediate, low, and intermediate ~ high, respectively. Therefore, the subchondral bone of the facet joint could be defined as the area sandwiched by articular cartilage of the facet joint and bone marrow in the articular process. Although a facet MR image enlarged 800% using the bilinear interpolation size conversion algorithm does not show individual trabeculae in the articular process, the MR image is clear enough to show the subchondral cortical bone plate as demonstrated by comparison with the micro-CT image (Fig. 4). The multi-threshold technique used in the current study provided clear border lines between the articular cartilage and the subchondral bone and between the subchondral bone and bone marrow. The mean subchondral bone thickness was calculated from the least distances between these border lines at approximately 100 data points throughout the facet joint surface, which allowed measurement of the subchondral bone thickness in a subpixel level. The current study only analyzed an averaged thickness through the entire subchondral area for each facet joint and did not show distribution of the thickness. Analyses of the thickness distribution would provide more detailed information on the relationship between the local load and thickness of the subchondral bone within each joint. Since the method used in the current study allows keeping the least thickness data at each measuring point, the subchondral bone density distribution could be analyzed in the future studies.

In the current study, the subchondral bone both in the superior and inferior articular processes in males was thicker than in females at all spinal levels but one level (superior articular process at L2–L3) in the asymptomatic subjects. This contrast was also found on patellar subchondral bone thickness4. The subchondral bone thickness also increased with each successive lower spinal level in the asymptomatic subjects. These findings suggest that the subchondral bone thickness of the facet joint corresponds to the load applied to the facet joint as seen in other joints5,8.

The subchondral bone thickness increased with age at some spinal levels in both symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects in male and only at one level in asymptomatic female subjects. A possible reason why the subchondral bone thickness correlates with age is increased facet load due to loss of an intervertebral disc height. Load applied to a spinal unit is transferred through an intervertebral disc anteriorly and facet joints posteriorly. Biomechanical studies of the spinal unit have demonstrated that a loss of disc height results in an increase in load transfer through the facet joints14,15. Clinical studies on the relationship between the disc degeneration and facet osteoarthritis suggested that the facet osteoarthritis is secondary to the disc degeneration16. Disc height loss occurs with disc degeneration. While aging has been considered a primary cause of the disc degeneration, various age-unrelated factors have also been thought to cause disc degeneration. Moreover, many asymptomatic individuals show apparent intervertebral disc disease on MR images. It has been reported that intervertebral degeneration or bulging was found with MR imaging in at least one lumbar level in 35% of asymptomatic subjects between 20 and 39 years old17. Therefore, disc degeneration could occur in any age group and even in asymptomatic subjects, which may explain significant correlations between the subchondral bone thickness and age were found only some of the subgroups in the current study. The relationship between the disc height loss and the thickness of the subchondral bone needs to be studied for further analyses of the age effect on the subchondral bone thickness of the facet joint. The difference between the female and male concerning the increase in the subchondral bone thickness with age may be related to endocrinological factors, but further studies will be also needed to explain this discrepancy.

Interestingly, the subchondral bone in the superior facet was thicker as compared with the inferior facet at all spinal levels in the non-symptomatic subjects of both genders. Furthermore, most significant Pearson correlations between age and thickness were found in the superior facets at most levels. As clear in the macroscopic morphology of the facet joint, the superior articular process has a concave surface and the inferior articular process has a convex surface. The literature shows studies which addressed the differences between concave and concave sides of joints in terms of the subchondral bone thickness. Simkin et al. studied the thickness of the subchondral bone in shoulder, elbow, wrist, hip, ankle, pretalar and first metatarsophalangeal joints using a fine contact radiograph of human cadaveric specimens sliced with a 4–6 mm thickness. They found that the subchondral bone thickness at the concave side of these joints was thicker than that in the convex side except the ankle joint. The authors implied that “opposing joint surfaces are subjected to different stresses under load: convex surface experience pure compression while concave surface undergo a measure of tension”18. The results of the current study show that the subchondral bone thickness in the concave side of the facet joint (superior articular process) was thicker than that in the convex side (inferior articular process) are consistent with the study done by Simkin et al. To test whether the principle regarding the different stresses in the subchondral bone of the joints depending on the convexity or concavity of the joint could be applied to the facet joint, further biomechanical study on the facet joint will be required.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH Program Grant P01 AR48152. Chun-Yue Duan was supported by the Chinese Scholarship Council State Scholarship Fund of Chinese Scholarship Council (CSC[2008]3019). The authors wish to thank the assistance of the Rush Micro-CT/Histology SubCore in the acquisition of the micro-CT images.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None of the authors have any conflict of interest relating to the submitted manuscript.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors declare the following contributions to the preparation of the manuscript: Study conception and design (Duan, Espinoza, An, Andersson, Hu, Lu and Inoue); collection and assembly of data (Duan and Espinoza); analysis and interpretation of data (Shott, Espinoza and Inoue); drafting of the manuscript (Duan, Espinoza and Inoue); critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (Espinoza, Inoue and Shott); final approval of the article (An and Inoue) obtaining of funding (Hu, Lu, An, Andersson and Inoue). All authors take responsibility for the integrity of the work

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cohen SP, Raja SN. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of lumbar zygapophysial (facet) joint pain. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:591–614. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200703000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buckland-Wright C. Subchondral bone changes in hand and knee osteoarthritis detected by radiography. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12:S10–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chao EYS, Inoue N, Elias JJ, Frassica FJ. Computational biomechanics using Image-based models. In: Frank J, Brody W, Zerhouni E, editors. Handbook of Medical Image Processing. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 285–98. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckstein F, Milz S, Anetzberger H, Putz R. Thickness of the subchondral mineralised tissue zone (SMZ) in normal male and female and pathological human patellae. J Anat. 1998;192:81–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1998.19210081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milz S, Putz R. Quantitative morphology of the subchondral plate of the tibial plateau. J Anat. 1994;185:103–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milz S, Eckstein F, Putz R. Thickness distribution of the subchondral mineralization zone of the trochlear notch and its correlation with the cartilage thickness: an expression of functional adaptation to mechanical stress acting on the humeroulnar joint? Anat Rec. 1997;248:189–97. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199706)248:2<189::AID-AR5>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Botter SM, van Osch GJ, Waarsing JH, van der Linden JC, Verhaar JA, Pols HA, et al. Cartilage damage pattern in relation to subchondral plate thickness in a collagenase-induced model of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2008;16:506–14. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Müller-Gerbl M. The subchondral bone plate. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 1998;141:1–134. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-72019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner S, Weckbach A, Müller-Gerbl M. The influence of posterior instrumentation on adjacent and transfixed facet joints in patients with thoracolumbar spinal injuries: a morphological in vivo study using computerized tomography osteoabsorptiometry. Spine. 2005;30:E169–E78. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000157431.73969.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takatori R, An HS, Ochia RS, Andersson GB, Inoue N. In vivo measurement of lumbar facet joint width and density distribution (Abstract). Trans. 52nd Annual Meeting of the Orthopaedic Research Society; Chicago. 2006. p. 1285. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujiwara A, Lim TH, An HS, Tanaka N, Jeon CH, Andersson GB, et al. The effect of disc degeneration and facet joint osteoarthritis on the segmental flexibility of the lumbar spine. Spine. 2000;25:3036–44. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wonneberger U, Schnackenburg B, Streitparth F, Walter T, Rump J, Teichgräber UK. Evaluation of magnetic resonance imaging-compatible needles and interactive sequences for musculoskeletal interventions using an open high-field magnetic resonance imaging scanner. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:346–51. doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9676-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otsuka Y, An HS, Ochia RS, Andersson GB, Espinoza Orías AA, Inoue N. In Vivo Measurement of Lumbar Facet Joint Area in Asymptomatic and Chronic Low Back Pain Subjects. Spine. 2010;35:924–8. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c9fc04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunlop RB, Adams MA, Hutton WC. Disc space narrowing and the lumbar facet joints. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984;66:706–10. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.66B5.6501365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang KH, King AI. Mechanism of facet load transmission as a hypothesis for low-back pain. Spine. 1984;9:557–65. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198409000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butler D, Trafimow JH, Andersson GB, McNeill TW, Huckman MS. Discs degenerate before facets. Spine. 1990;15:111–3. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199002000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, Patronas NJ, Wiesel SW. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone J Surg Am. 1990;72:403–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simkin PA, Graney DO, Fiechtner JJ. Roman arches, human joints, and disease: differences between convex and concave sides of joints. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:1308–11. doi: 10.1002/art.1780231114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]