Abstract

Background

The use of clinical registries and administrative datasets in pediatric cardiovascular research has become increasingly common. However, this approach is limited by relatively few existing datasets, each of which contain limited data, and do not communicate with one another. We describe the implementation and validation of methodology using indirect patient identifiers to link The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery (STS-CHS) Database to The Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) Database (a pediatric administrative database).

Methods and Results

Centers submitting data to STS-CHS and PHIS during 2004-2008 were included (n=30). Both datasets were limited to patients 0-18 years undergoing cardiac surgery. An exact match was defined as an exact match on each of the following: date of birth, date of admission, date of discharge, sex, and center. Likely matches were defined as an exact match for all variables except +/- 1 day for one of the date variables. Of 45,830 STS-CHS records, 87.4% matched to PHIS using exact match criteria and 90.3% using exact or likely match criteria. Validation in a subset of patients revealed that 100% of exact and likely matches were true matches.

Conclusions

This analysis demonstrates that indirect identifiers can be used to create high quality link between a clinical registry and administrative dataset in the congenital heart surgery population. This methodology, which can also be applied to other datasets, allows researchers to capitalize on the strengths of both types of data and expands the pool of data available to answer important clinical questions.

Introduction

Historically, evidence to guide optimal care in patients with congenital heart disease has been limited (1). Key barriers to conducting clinical research in this population include the relative rarity and heterogeneity of disease, and the cost and ethical issues surrounding the conduct of large prospective trials. Recently, the use of existing multi-institutional clinical and administrative databases to conduct research has become increasingly common (1-5). This approach leverages existing data sources to overcome many of these key barriers. However, there are also certain limitations. There are currently relatively few existing datasets in the field of pediatric cardiovascular medicine, each of which contain limited data, and do not freely communicate with one another. For example, clinical registries often contain detailed disease-specific information but may lack data concerning other diagnoses or procedures, may contain limited resource utilization data such as use of medications, laboratory and imaging studies, and hospital charges, and often do not contain longitudinal follow-up data. Administrative datasets contain more resource utilization and follow-up data, but often do not contain detailed disease-specific information, and rely on the use of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, (ICD-9) coding of diagnoses and procedures from the hospital bill, which may have limited accuracy and granularity in some cases (6,7). In addition, while some datasets may collect certain direct patient identifiers, these are not routinely distributed to researchers or made publicly available due to concerns related to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Recently, methodology has been developed to link adult cardiac registry and administrative data through the use of indirect patient identifiers (8,9). These include date of birth, date of admission, date of discharge, and sex. It has been shown that nearly all records (>99.9%) at a given center can be uniquely identified using combinations of these indirect identifiers. A crosswalk can then be created between two datasets linking patients based on the values of center where hospitalized and the indirect identifiers. This approach has been used to successfully link several adult clinical cardiology and cardiac surgery registries to Medicare claims data (10,11). This methodology allows researchers to capitalize on the strengths of both types of data sources and expands the pool of existing data available for analysis. To date, this approach has not yet been applied in pediatric cardiovascular medicine. We describe the implementation and validation of methodology utilizing indirect identifiers in the congenital heart surgery population through linking The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery (STS-CHS) Database with The Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) Database (a large pediatric administrative database).

Methods

Data Sources

The STS-CHS Database is the largest existing clinical congenital heart surgery data registry in the world. It currently contains data on more than 140,000 surgeries conducted since 1998 performed at 85 US centers in 37 states. This represents nearly three quarters of all US centers performing congenital heart surgery (12). The STS-CHS Database contains peri-operative and operative data on all patients undergoing congenital heart surgery at participating centers, including demographic information, anatomic diagnosis, associated non-cardiac abnormalities, preoperative factors, intra-operative details, surgical procedure, postoperative complications, and in-hospital mortality (Table 1). Of note, patient diagnoses and procedures are coded using the International Pediatric and Congenital Cardiac Code, which was developed through a collaborative effort of an international group of pediatric cardiologists and congenital heart surgeons (13). Data quality and reliability are assured through intrinsic verification of data as well as a formal process of site visits and data audits (14). While the STS-CHS Database contains a wealth of clinical information, it currently does not collect data on medication administration, other non-cardiac procedures performed, or resource utilization data.

Table 1.

Data contained in the STS-CHS and PHIS Databases

| Variable | STS-CHS | PHIS |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | x | x |

| Weight | x | |

| Non-cardiovascular abnormalities | x | x |

| Pre-operative factors | x | x |

| Cardiac diagnosis | x | x |

| Surgical Procedure | x | x |

| Operative Data | x | |

| Perfusion Data | x | |

| Post-operative complications | x | x |

| Total length of stay | x | x |

| ICU length of stay | x | |

| Mortality | x | x |

| Hospital Charges | x | |

| Medications | x | |

| Utilization of imaging/lab studies | x | |

| Other non-cardiac procedures | x |

STS-CHS = Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery, PHIS = Pediatric Health Information Systems, ICU = intensive care unit. Note that in the several areas of overlap, the databases provide complementary information which broadens the information available to investigators. For example, regarding pre-operative factors the STS-CHS Database contains a set of clinician coded variables, while the PHIS database contains information regarding pre-operative status coded as ICD-9 diagnosis and procedure codes, as well as pre-operative medication administration and other resource utilization (eg. lab and imaging studies).

The Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) is an administrative database containing inpatient data, from 41 not-for-profit tertiary care pediatric hospitals in the US affiliated with the Child Health Corporation of America (Shawnee Mission, Kansas), a business alliance of children's hospitals. The database currently contains information from more than 4.6 million inpatient discharges. Data quality and reliability are assured through a joint effort between the Child Health Corporation of America and participating hospitals. Data collected include demographics, diagnoses and procedures (using ICD-9 coding), and outcomes such as length of stay and in-hospital mortality. Importantly, resource utilization data such as pharmaceuticals, radiology imaging, laboratory studies, and hospital charges are also collected.

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at Duke University Medical Center and The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia with waiver of informed consent. The study was also reviewed and approved by the STS Work Force on National Databases, the STS Congenital Heart Surgery Database Task Force, and the STS Longitudinal Follow-up Task Force, as well as Child Health Corporation of America in compliance with their PHIS Database External Use Guidelines.

Data Subset/Patient Population

STS-CHS Database records were restricted to those from the 30 hospitals also submitting data to the PHIS Database, years 2004-2008, and patients 0-18 years of age. Since it is possible to have multiple records for a given admission if more than one surgery is performed during the admission, only the first cardiovascular operation of the admission was considered, narrowing the population to one record per admission. Both cardiovascular cases involving cardiopulmonary bypass and those not involving cardiopulmonary bypass were included. General thoracic procedures were excluded.

PHIS Database records were also restricted to those from the 30 hospitals who submit data to both PHIS and STS-CHS, years 2004-2008, and patients 0-18 years of age. Because the PHIS Database contains information on all inpatient admissions, PHIS data were further refined to focus on the cardiac population according to 3 different methods. The PHIS population inclusion criteria for Method 1 (which was the most restrictive) consisted of the service line for cardiac surgical care (service lines encompass any of the diagnosis or procedure related groups for a particular procedure or condition/disorder) or any of the following ICD-9 procedure codes: 35.xx – 39.xx, which encompass all the procedure codes for cardiac operations. PHIS population inclusion criteria for Method 2 consisted of all of those for Method 1, and in addition: the service line for cardiac medical care, the service line for neonatal medical care, or the service line for neonatal surgical care. PHIS population inclusion criteria for Method 3 (which was the least restrictive) consisted of any cardiac (medical or surgical) service line, and any of the cardiac diagnosis or procedure related group (these contain any cardiac related diagnosis and procedure codes including those not related to cardiac surgery).

Data Link

While the STS-CHS population inclusion criteria were held constant, the PHIS population inclusion criteria were varied from Method 1-3 as described above, and the proportion of matching records and duplicates evaluated. An exact match was defined as exact match on each of the following: date of birth, date of admission, date of discharge, sex, and center. Likely matches were defined as exact match for all variables except +/- 1 day for one of the date variables. Duplicates are those where an STS-CHS record matched to more than one PHIS record or vice versa. The total percent matched was calculated based on the number of matched records in a certain category minus the number of duplicates divided by the total number of STS-CHS records. For the three STS-CHS centers who did not submit date of birth for patients entered into the database, date of birth was imputed based on the date of surgery and age at surgery. An exact match on imputed date of birth was counted in the exact match category. The proportion matched when imputed date of birth was varied by +/- 1 day was also evaluated and included in the likely match category.

Validation

From the population identified using Method 1, a 10% sample of the exact matches from one institution and the entire sample of likely matches at this same institution were evaluated. Data were reviewed to evaluate whether the patients from each dataset matched via the method of indirect identifiers were indeed a match (based on medical record number).

Analysis

The proportion of exact and likely matches, as well as duplicates, was evaluated utilizing the various inclusion criteria (Methods 1-3) as described above. Variation between centers in the percent match was also evaluated, and patient demographics and the most common cardiac procedures in the matched and unmatched populations were described. The primary procedure coded in the STS-CHS Database was utilized for this analysis. Procedures were further characterized by their Society of Thoracic Surgeons-European Association of Cardiothoracic Surgery (STS-EACTS) risk category for mortality (category 1 = lowest mortality risk, category 5 = highest mortality risk) (15). Finally, results of the validation of the link in a subset of patients were described. Due to the descriptive nature of the analysis, formal statistical comparisons were not made.

Results

Data Link

Using Method 1, 45,830 STS-CHS records and 211,973 PHIS records were identified (Table 2). Broadening the initial inclusion criteria used to define the PHIS cardiac population (Methods 2 and 3) was not associated with a greater match but was associated with a greater number of duplicates (Table 2). Therefore Method 1 was deemed to be the best method with 87.4% exact matches and a total of 90.3% exact or likely matches.

Table 2.

Proportion of matched patients between datasets using varying methodology

| Method 1 | Method 2 | Method 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|||||||||

| PHIS | STS-CHS | Duplicates | PHIS | STS-CHS | Duplicates | PHIS | STS-CHS | Duplicates | |

| Number of Records | 211,973 | 45,830 | 258,082 | 45,830 | 435,641 | 45,830 | |||

| Exact Match | 40,191 | 140 | 40,248 | 166 | 40,291 | 174 | |||

| Total Percent Matched | 87.4% | 87.5% | 87.5% | ||||||

| Likely Match | |||||||||

| Admission Date +/-1d | 941 | 6 | 942 | 6 | 942 | 6 | |||

| Discharge Date +/- 1d | 389 | 0 | 392 | 2 | 392 | 2 | |||

| Total | 1,330 | 1,334 | 1,334 | ||||||

| Total Percent Matched | 90.3% | 90.4% | 90.4% | ||||||

| Imputed DOB +/- 1d | 12 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 0 | |||

| Total Percent Matched | 90.3% | 90.4% | 90.5% | ||||||

The PHIS population inclusion criteria were varied from Method 1 (most restrictive) to Method 3 (leave restrictive) as described in the text, while the STS-CHS population inclusion criteria remained constant over all 3 methods. An exact match was defined as an exact match on each of the following: date of birth, date of admission, date of discharge, gender, and center. Likely matches were defined as an exact match for all variables except +/- 1 day on the indicated item in table. Duplicates represent an STS-CHS record matching more than one PHIS record or vise-versa. The total percent matched was calculated based on the number of matched records in a certain category minus the number of duplicates divided by the total number of STS-CHS records. Note, for the three STS-CHS centers who did not submit date of birth, date of birth was imputed based on the date of surgery and age at surgery. The last 2 rows of data in the table indicate the proportion matched when imputed date of birth was varied by +/- 1 day. An exact match on imputed date of birth was counted in the exact match category.

Center Variation

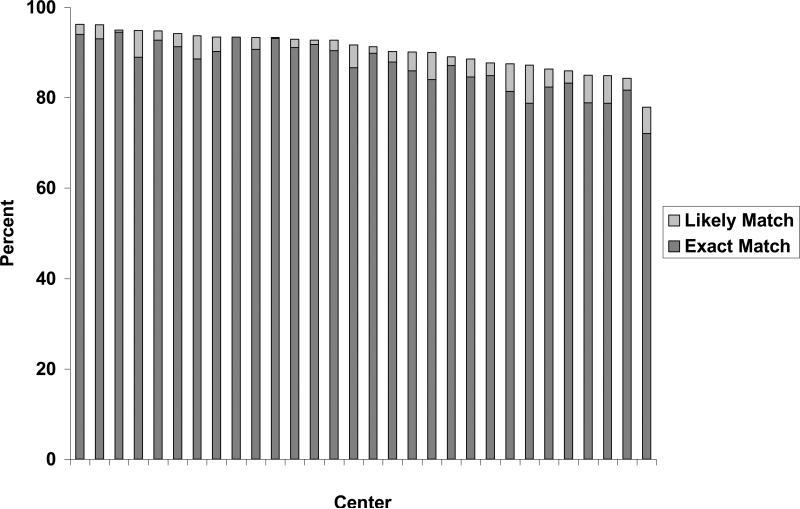

The proportion of exact and likely matches at each of the 30 centers is displayed in Figure 1. For exact matches, the median percent matched was 88.3% (interquartile range 83.6% - 91.3%). The proportion of exact matches was greater than 75% in all cases with the exception of one center with 72.1% exact matches. For likely matches, the median percent matched was 2.9% (interquartile range 2.2% - 5.1%).

Figure 1.

Proportion matched between datasets by center (n=30)

Characteristics of the Matched vs. Unmatched Population

Table 3 displays the characteristics of the matched and unmatched populations. In general, sex was similar across groups while the unmatched cohort tended to be younger than the matched cohort. In evaluating the proportion of patients in each STS-EACTS risk category, the unmatched cohort tended to include a greater proportion of patients in the lower risk categories (ie. category 2). Regarding specific procedures, the unmatched cohort contained a greater proportion of patients undergoing patent ductus arteriosus ligation, which may in part explain the lower age of the unmatched cohort (Table 4). The unmatched cohort also contained a greater proportion of patients undergoing a pacemaker procedure. Other common procedures performed were similar between the matched and unmatched cohorts.

Table 3.

Characteristics of matched vs. unmatched population

| Variable | Matched* (n = 40,051) | Unmatched (n = 5,779) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, male | 22,280 (55.6%) | 3,085 (53.4%) |

| Median age, days (IQR) | 183 (27-1191) | 113 (14 – 1100) |

| STS-EACTS risk category | ||

| 1 | 8,962 (22.4%) | 1,102 (19.1%) |

| 2 | 13,337 (34.1%) | 2, 370 (41.0%) |

| 3 | 5,679 (14.2%) | 575 (10.0%) |

| 4 | 8,603 (21.5%) | 1,083 (18.7%) |

| 5 | 1,850 (4.6%) | 252 (4.3%) |

| Not categorized | 1,290(3.2%) | 397 (6.9%) |

Exact matches only, excluding duplicates, IQR = interquartile range, STS-EACTS = Society of Thoracic Surgeons-European Association of Cardiothoracic Surgery

Table 4.

Most common procedures in matched vs. unmatched population

| Matched | Unmatched | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure | N | % | Procedure | N | % |

| VSD repair | 3395 | 8.5 | PDA ligation | 1222 | 21.2 |

| Arch/coarctation repair | 3090 | 7.7 | Pacemaker/ICD procedure | 545 | 9.4 |

| PDA ligation | 2991 | 7.5 | Arch/coarctation repair | 349 | 6.0 |

| Cavopulmonary anastomosis | 2179 | 5.4 | VSD repair | 320 | 5.5 |

| AV canal repair | 2107 | 5.3 | Cavopulmonary anastomosis | 270 | 4.7 |

| Tetralogy of Fallot repair | 2078 | 5.2 | Tetralogy of Fallot repair | 239 | 4.1 |

| ASD repair | 2054 | 5.1 | Norwood procedure | 223 | 3.9 |

| Fontan operation | 1980 | 4.9 | AV Canal repair | 208 | 3.6 |

| Norwood procedure | 1566 | 3.9 | Fontan operation | 206 | 3.6 |

| Systemic to pulmonary artery shunt | 1442 | 3.6 | Systemic to pulmonary artery shunt | 162 | 2.8 |

VSD = ventricular septal defect, PDA = patent ductus arteriosus, AV = atrioventricular, ASD = atrial septal defect, ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

Validation

In the validation subset of a 10% (n= 250) sample of the exact matches from one institution and the entire sample (n= 112) of likely matches at this same institution, 100% of the exact and likely matches were found to be true matches.

Discussion

These data demonstrate the feasibility of utilizing indirect identifiers to create a high quality link between clinical registry and administrative data for patients undergoing congenital heart surgery. This methodology allows researchers to capitalize on the strengths of both datasets and expands the pool of data available for analysis. Similar methodology can also be applied to link other existing data sources.

The use of indirect identifiers to link large datasets has been described previously in numerous adult populations (16,17). Hammill et. al first applied this methodology to the cardiac population to link 81% of more than 35,000 records in an adult heart failure registry to Medicare data (8). Subsequently this dataset was utilized to evaluate whether certain process of care measures collected in the heart failure registry impact patient outcomes as assessed by 60 day and 1 year mortality in Medicare data (10). Data from the American College of Cardiology-National Cardiovascular Data Registry (ACC-NCDR) has also been linked with Medicare data using this methodology to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of drug-eluting vs. bare-metal stents as measured by death or cardiovascular events throughout 30 months of follow-up (11). For this study, 76% of more than 250,000 patients in the ACC-NCDR registry were able to be linked to Medicare data. Thus, in adult cardiology, Medicare data are utilized to capture longitudinal follow-up of elderly individuals enrolled in various registries (which are most often limited to in-hospital or 30 day outcomes).

In pediatric cardiology/congenital heart surgery there is currently no data source which captures longitudinal follow-up on the overall cohort of patients. However, linked data in this population may be utilized in a variety of other ways. First, linked STS-CHS and PHIS data may be utilized to perform comparative effectiveness analyses of various medications not able to be performed in either dataset alone. For these analyses, the PHIS Database provides medication data and STS-CHS Database provides detailed information regarding the patient's diagnosis, procedure, and other operative data. The two datasets contain complementary outcomes data. Data from these analyses will provide useful information regarding current practice variation as well as data concerning the efficacy and safety of various medications. The linked data will also facilitate clinical trial planning by providing estimates of treatment effect that can inform sample size calculations (18). Linked STS-CHS and PHIS data may also be utilized to evaluate resource utilization in the congenital heart surgery population including utilization of various imaging modalities, lab testing, and total hospital charges/costs. Linked data could also be used to evaluate differences in case ascertainment of various congenital heart operations comparing the ICD-9 coding system to that used in the STS-CHS Database (The International Pediatric and Congenital Cardiac Code) (13).

Similar methodology to that used in this study could also be utilized to link other existing datasets, such as the Virtual Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Database System (VPS D atabase) of the Pediatric Cardiac Intensive Care Society, the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) Registry, the American College of Cardiology pediatric catheterization database [Improving Pediatric and Adult Congenital Treatment (IMPACT)], and the Pediatric Heart Transplant Study Group (PHTSG) Database (19). Linkage to administrative datasets such as state Medicaid databases or private insurance databases may also be possible and provide longitudinal follow-up in a subset of patients. In addition, in January 2010, the STS-CHS Database began collecting HIPAA-compliant unique patient, surgeon, and hospital identifier fields. These additional identifiers will allow linkage to the National Death Index and Social Security Death Master File, which will enable longitudinal survival analyses (19).

In our analysis, we were able to link a greater proportion of patients between datasets compared with linkage of adult cardiac registries to Medicare data (~ 90% vs. 75-80%) (8,10,11). This may in part be due to the fact that the adults who participate in a Medicare managed care plan or receive care through the VA system will not be found in a Medicare dataset (8). The datasets used in the present analysis were not dependent on insurance type, therefore a greater match would be expected. There may be other reasons why certain patients did not match in our analysis. We found a higher proportion of younger patients undergoing patent ductus arteriosus ligation in the unmatched cohort. These may be premature infants in the neonatal intensive care unit with multiple diagnosis and procedure codes such that they are not classified primarily by their cardiac procedure. Alternatively, it may be that the unmatched patients had surgeries performed at institutions affiliated with the main center which are captured in the registry but not by the administrative database, which only captures data at the main children's hospital. It is also possible that at some institutions, this procedure may be performed by general pediatric surgeons rather than congenital heart surgeons, and thus not captured in the registry. We also found a higher proportion of pacemaker procedures in the unmatched cohort. These procedures, often performed primarily by electrophysiologists, may not be entered into the surgical registry. Finally, lack of match in some cases may also be due to the fact that if some patients are transferred to long term care or rehabilitation units affiliated with the hospital, their discharge dates may not match if the registry captures their discharge date from the inpatient facility while the administrative data captures the entire length of stay.

In evaluating the methodology used in linking datasets, we were able to apply the same set of indirect identifiers as utilized in linkage of adult datasets to perform linkage of pediatric datasets (8). We also found that similar to adult analyses, it was important to be somewhat restrictive regarding inclusion criteria for the population of interest, as loosening these criteria did not result in a greater proportion of matches and only lead to a greater number of duplicate records (8). Similar to previous adult analyses linking datasets in the fields of emergency medicine and obstetrics, we were able to validate our matches in a subset of patients (16,17). Our analysis revealed that 100% of the exact and likely matches were true matches. Thus, it is reasonable to use both of these cohorts in subsequent studies using linked data to maximize the patient pool available for analysis.

Conclusions

This analysis demonstrates that indirect identifiers can be used to create a high quality link between a clinical registry and administrative dataset in the congenital heart surgery population. This will allow several analyses to be performed with linked data from this study, and similar methodology can also be applied to link other datasets. Leveraging these and other linked data will enable researchers to answer important questions regarding practice variation, and the efficacy and safety of many therapies used in this population which would otherwise not be possible.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant 1RC1HL099941-01, under the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

Dr. Pasquali receives grant support (KL2 RR024127-02) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, and from the American Heart Association (AHA) Mid-Atlantic Affiliate Clinical Research Program. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR, NIH, or AHA.

Dr. Shah receives support from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K01 AI73729) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation under its Physician Faculty Scholar program. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Dr. J Jacobs’ disclosures: Chair, Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Database Task Force; Medical advisor and shareholder, CardioAccess

References

- 1.Sanders SP. Conducting pediatric cardiovascular trials. Am Heart J. 2001;142:218–223. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.117064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson JN, Jaggers J, Li S, O'Brien SM, Li JS, Jacobs JP, Jacobs ML, Welke KF, Peterson ED, Pasquali SK. Center variation and outcomes associated with delayed sternal closure following stage 1 palliation for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. J Thorac and Cardiovasc Surg. 2010 Feb 16; doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.11.029. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karamlou T, Diggs BS, Person T, Ungerleider RM, Welke KF. National practice patterns for management of adult congenital heart disease: operation by pediatric heart surgeons decreases in-hospital death. Circulation. 2008;118:2345–2352. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.776963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirsch JC, Gurney JG, Donohue JE, Gebremariam A, Bove EL, Ohye RG. Hospital mortality for Norwood and arterial switch operations as a function of institutional volume. Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;29:713–717. doi: 10.1007/s00246-007-9171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curzon CL, Milford-Beland S, Li JS, O'Brien SM, Jacobs JP, Jacobs ML, Welke KF, Lodge AJ, Peterson ED, Jaggers J. Cardiac surgery in infants with low birth weight is associated with increased mortality: analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:546–551. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strickland MJ, Riehle-Colarusso TJ, Jacobs JP, Reller MD, Mahle WT, Borto LD, Tolbert PE, Jacobs ML, Lacour-Gayer FG, Tchervenkov CI, Mavroudis C, Correa A. The importance of nomenclature for congenital cardiac disease: implications for research and evaluation. Cardiol Young. 2008;18(Suppl 2):92–100. doi: 10.1017/S1047951108002515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cronk CE, Malloy ME, Pelech AN, Miller RE, Meyer SA, Cowell M, McCarver DG. Completeness of state administrative databases for surveillance of congenital heart disease. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2003;67:597–603. doi: 10.1002/bdra.10107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammill BG, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Fonarow GC, Schulman KA, Curtis LH. Linking inpatient clinical registry data to Medicare claims data using indirect identifiers. Am Heart J. 2009;157:995–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dokholyan RS, Muhlbaier LH, Falletta J, Jacobs JP, Shahian D, Haan CK, Peterson ED. Regulatory and Ethical Considerations for Linking Clinical and Administrative Databases. Am Heart J. 2009;157:971–982. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernandez AF, Hammill BG, Peterson ED, Yancy CW, Schulman KA, Curtis LH, Fonarow GC. Relationship between emerging measures of heart failure processes of care and clinical outcomes. Am Heart J. 2010;159:406–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douglas PS, Brennan JM, Anstrom KJ, Sedrakyan R, Eisenstein EL, Haque G, Dai D, Kong DF, Hammill B, Curtis L, Matchar D, Brindis R, Peterson ED. Clinical effectiveness of coronary stents in elderly persons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1629–1641. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs ML, Mavroudis C, Jacobs JP, Tchervenkov CI, Pelletier GJ. Report of the 2005 STS Congenital Heart Surgery Practice and Manpower Survey. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1152–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franklin RC, Jacobs JP, Krogmann ON, Béland MJ, Aiello VD, Colan SD, Elliott MJ, William Gaynor J, Kurosawa H, Maruszewski B, Stellin G, Tchervenkov CI, Walters Iii HL, Weinberg P, Anderson RH. Nomenclature for congenital and paediatric cardiac disease: historical perspectives and The International Pediatric and Congenital Cardiac Code. Cardiol Young. 2008;18(Suppl 2):70–80. doi: 10.1017/S1047951108002795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clarke DR, Breen LS, Jacobs ML, Franklin RCG, Tobota Z, Maruszewski B, Jacobs JP. Verification of data in congenital cardiac surgery. Cardiol Young. 2008;18(Suppl2):177–187. doi: 10.1017/S1047951108002862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Brien SM, Clarke DR, Jacobs JP, Jacobs ML, Lacour-Gayet FG, Pizarro C, Welke KF, Maruszewski B, Tobota Z, Miller WJ, Hamilton L, Peterson ED, Mavroudis C, Edwards FH. An empirically based tool for analyzing mortality associated with congenital heart surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:1139–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newgard CD. Validation of probabilistic linkage to match de-identified ambulance records to a state trauma registry. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:69–75. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meray N, Beitsma JB, Ravelli ACJ, Bonsel GJ. Probabilistic record linkage is a valid and transparent tool to combine databases without a patient identification number. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;883:891. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benjamin DK, Jr, Smith PB, Jadhav P, Gobburu JV, Murphy D, Hasselblad V, Baker-Smith C, Califf RM, Li JS. Pediatric antihypertensive trial failures: Analysis of end points and dose range. Hypertension. 2008;51:834–840. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.108886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobs JP, Haan CK, Edwards FH, Anderson RP, Grover FL, Mayer JF, Chitwood WR. The rationale for incorporation of HIPAA compliant unique patient, surgeon, and hospital identifier fields in the STS Database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:695–698. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.04.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]