Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Progressive fibrosis in the diabetic kidney is driven and sustained by a diverse range of profibrotic factors. This study examines the critical role of microRNAs (miRNAs) in the regulation of the key fibrotic mediators, TGF-β1 and TGF-β2.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Rat proximal-tubular epithelial cells (NRK52E) were treated with TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 for 3 days, and expression of markers of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and fibrogenesis were assessed by RT-PCR and Western blotting. The expression of miR-141 and miR-200a was also assessed, as was their role as translational repressors of TGF-β signaling. Finally, these pathways were explored in two different mouse models, representing early and advanced diabetic nephropathy.

RESULTS

Both TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 induced EMT and fibrogenesis in NRK52E cells. TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 also downregulated expression of miR-200a. The importance of these changes was demonstrated by the finding that ectopic expression miR-200a downregulated smad-3 activity and the expression of matrix proteins and prevented TGF-β–dependent EMT. miR-200a also downregulated the expression of TGF-β2, via direct interaction with the 3′ untranslated region of TGF-β2. The renal expression of miR-141 and miR-200a was also reduced in mouse models representing early and advanced kidney disease.

CONCLUSIONS

miR-200a and miR-141 significantly impact on the development and progression of TGF-β–dependent EMT and fibrosis in vitro and in vivo. These miRNAs appear to be intricately involved in fibrogenesis, both as downstream mediators of TGF-β signaling and as components of feedback regulation, and as such represent important new targets for the prevention of progressive kidney disease in the context of diabetes.

Diabetic nephropathy is characterized by the progressive accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) in basement membranes, the glomerular mesangium, and peritubular interstitium, which leads to scarring and ultimately nephron dropout. Recent data have suggested an important role for specific microRNAs in enhancing fibrogenic signaling and sustaining profibrotic phenotypes (1) that potentially contribute to the development and progression of a number of diseases (2). MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short, single-stranded RNA molecules that interact with the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of mRNAs to regulate gene expression. This usually occurs by repression of protein translation via a mechanism that involves incomplete base pairing with the 3′UTR of target mRNAs, or by causing target sequences to become unstable and degraded sooner (2,3), thereby causing protein expression to be downregulated.

In the kidney, renal fibrosis is initiated and sustained by a number of different prosclerotic factors. Among the most important of the prosclerotic factors appears to be TGF-β (4,5), which stimulates the expression of matrix proteins and triggers tubular epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (tubular EMT) in tubular cells. In the kidney, TGF-β is expressed in three different isoforms. Each isoform induces fibrogenesis in renal cells in vitro (6), possibly acting through the same receptors. However, differential effects on immune function and development have been reported (7,8). For example, deletion of TGF-β1 results in widespread distribution and immunomodulatory effects not seen with TGF-β2. In the streptozotocin model of diabetes, the expression of TGF-β2 is markedly increased in the kidney, paralleling renal ECM accumulation early in disease (8,9). By contrast, TGF-β1 protein levels remain unchanged during this period despite increased mRNA levels (9). Consequently, recent studies have focused on the antifibrotic potential of selectively targeting TGF-β2 for the prevention of progressive renal disease (10,11).

A number of different factors are thought to alter the expression of TGF-β2 in the kidney, including miRNAs. In particular, 3′UTR of TGF-β2 contains a target site for miR-141/200a. Moreover, TGF-β1 has been shown to regulate the miR-200 family in a renal cell line (12). In this study, we investigate the role of miR-200a and its closely related family member, miR-141, as regulators of TGF-β2 and fibrogenesis both in vitro and in vivo, using two animal models of renal fibrosis, representing earlier- and later-stage kidney disease.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

In vitro studies—cell culture.

The rat kidney tubular epithelial cell line (NRK52E) was obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection (Rockville, MD) and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium containing 10% serum and 25 mmol/l glucose as previously described. For experimental treatments, serum was reduced to 2%.

Drugs and antibodies.

Recombinant human TGF-β1, TGF-β2, normal goat IgG, and TGF-β2 neutralizing antibody were from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN) and used at specified concentrations. Typically, 24 h after cells were seeded, the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 2% serum with or without the treatment, and cells were incubated a further 3 days. For Western blotting, primary antibodies were collagen I and α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) (1:2,000; Dako), E-cadherin (1:2000; Becton Dickinson), and β-actin (1:10,000; Abcam) and secondary antibodies were goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit HRP conjugated (1:2,000; Dako).

RNA extraction and real-time PCR.

Gene expression was analyzed by real-time (RT)-PCR, using the TaqMan system based on real-time detection of accumulated fluorescence (ABI Prism 7500; Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA). Fluorescence for each cycle was quantitatively analyzed by an ABI Prism 7500 Sequence Detection System (Perkin-Elmer). To control for variation in the amount of DNA that was available for PCR in the different samples, gene expression of the target sequence was normalized in relation to the expression of an endogenous control, 18S rRNA (18S rRNA TaqMan Control Reagent kit, ABI Prism 7500; Perkin-Elmer). Details of primers and TaqMan probes for these genes have been previously reported (4). Each experiment was conducted in four or six replicates. Results were expressed relative to control (untreated) cells, which were arbitrarily assigned a value of 1.

miRNA assay.

For miRNA analysis, cDNA synthesis and RT-PCR assays were performed using TaqMan miRNA assays as per manufacturer's recommendations (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Experimental groups were in replicates of six and normalized to Sno135 or U87 for mouse and rat samples, respectively.

Transfection of miRNA precursors.

NRK52E cells were seeded at 3 × 104 cells per well in 12-well plates. The following day, medium was replaced with OptiMEM (Invitrogen), and cells were transfected with premiRNAs (Applied Biosystems) at 100 nmol/l final concentration using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen). In each case premiRNA negative controls were used at the same concentration. Cells were harvested three days posttransfection. Under these conditions, transfection efficiency was high, typically with 5–10,000-fold higher miRNA expression observed in transfected cells when compared with endogenous levels.

TGF-β2 3′UTR-luciferase reporter analyses.

For transfection, NRK52E cells were seeded 1 × 105 cells per well in 6-well plates the day before transfection (4). The TGB-β2 3′UTR was cloned into the pRL reporter vector (Promega) by PCR and represents the entire 352 nucleotides of the 3′UTR. The mutant TGF-β2 3′UTR, synthesized (GenScript), was identical to the wild-type sequence except for the seed region, where the complementary sequence was used.

pRL-reporter plasmids (0.5 μg/ml), CMV-galactosidase construct, and miRNAs were cotransfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in OptiMEM medium. Cells were harvested 48 h posttransfection using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega), and luciferase and galactosidase assays were performed as per manufacturer's recommendations. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and each experiment was repeated at least twice.

SMAD3 activity.

The CAGA12-luciferase reporter was used to assess SMAD3 activity. The construct contains the luciferase gene, the expression of which is driven by a promoter with CAGA boxes (CAGA12) to which activated SMAD3 binds (13). Transfection experiments and luciferase assays were performed as for the 3′UTR assays.

TGF-β2 ELISA.

The TGF-β2 ELISA (R&D Systems) was used to determine the total level of TGF-β2 in acid-activated cell culture supernatants as per the manufacturer's recommendations.

Western blot analysis.

Whole-cell lysates that contained 10–50 μg of protein were subjected to 10–12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes by semidry transfer. Membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk/Tris-buffered saline with Tween for 1 h at room temperature. All primary and secondary antibody incubations were for 1 h at room temperature. Detection was by chemiluminescence and images captured on the XRS Chemidoc system (BioRad) and analyzed by Quantity One software (BioRad).

In vivo studies.

To explore the relationship between miR-200a and the development and progression of fibrotic kidney disease, renal fibrogenesis was studied in two animal models of renal fibrosis, representing earlier and later renal stage kidney disease, respectively. Early renal changes were examined in apoE knockout mice rendered diabetic by five daily intraperitoneal injections of streptozotocin (55 mg/kg) as previously described (14) and compared with apoE KO mice that received vehicle (citrate buffer) alone (n = 8/group). We have previously described that 10 weeks of diabetes is associated with all of the early changes of diabetic nephropathy including microalbuminuria, renal hypertrophy, hyperfiltration, and basement membrane (14). In the second model, c57bl6 mice were randomized to receive oral gavage with adenine (1 mg/kg/day) or vehicle (0.5% methylcellulose) for four weeks (n = 4/group). This results in marked tubulointerstitial fibrosis and nephron dropout, consistent histologically with changes seen in more advanced chronic kidney disease (15).

Immunohistochemistry.

Four-micrometer paraffin kidney cortex sections were used for immunohistochemical analyses as previously described (16). Primary antibodies used were collagen IV, fibronectin, and αSMA (1:800; Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL). Secondary antibodies were used as previously described (16). Finally, sections were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted.

Statistical analysis.

Values are shown as means ± SEM unless otherwise specified. Statview (Brainpower, Calabasas, CA) was used to analyze data by unpaired Student t test or by ANOVA and compared using Fisher least significant differences post hoc test. Nonparametric data were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

TGF-β2 induces expression of EMT and fibrogenesis.

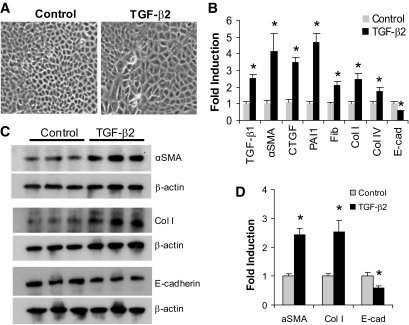

Exposure of NRK52E cells to TGF-β2 (10 ng/ml) for 3 days resulted in a morphological and phenotypic transition characteristic of EMT (Fig. 1A) associated with reduced expression of the epithelial marker, E-cadherin; increased expression of mesenchymal markers, vimentin and αSMA; and increased expression of ECM proteins, fibronectin, collagen I, and collagen IV (Fig. 1B). TGF-β2 also induced the expression of TGF-β1 and the expression of PAI-1, a classical marker of TGF-β1 signaling (Fig. 1B). These changes in expression were also observed at the protein level (Fig. 1C and D).

FIG. 1.

TGF-β2 induces EMT-like changes in proximal tubular epithelial cells. A: NRK52E cells were cultured in the presence of TGF-β2 (10 ng/ml, 3 days). Light microscopy images (×20) demonstrate that TGF-β2 causes a loss of the typical epithelial morphology to larger and more irregular shaped cells typical of the myofibroblast phenotype. B: After treatment with TGF-β2 (10 ng/ml, 3 days), gene expression levels were assessed by real-time QPCR. A significant increase was observed in the expression of profibrotic factors (TGF-β1, CTGF), fibrotic genes (αSMA, fibronectin [Fib], collagen [Col] I and IV), and PAI-1, but E-cadherin (E-cad) was significantly reduced (*P < 0.05 compared with control). C: Western analysis demonstrated that αSMA and Col I were both significantly elevated at the protein level after TGF-β2 treatment, while E-cadherin was decreased. D: The results from the Western analysis in C are shown as a graph (*P < 0.05 compared with control).

TGF-β1 induces TGF-β2 and fibrogenesis.

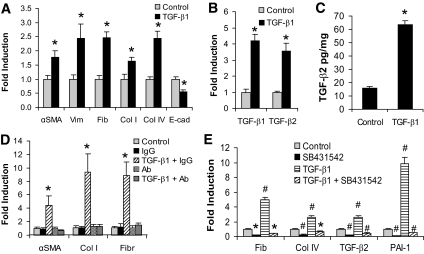

Treatment of the NRK52E cells with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml, 3 days) also resulted in EMT and associated changes in gene expression (Fig. 2A). TGF-β1 was also able to induce its own expression (Fig. 2B) and that of TGF-β2 at a gene (Fig. 2B) and protein level (Fig. 2C). To explore the functional role of TGF-β2 changes induced by TGF-β1, a neutralizing antibody specific for TGF-β2 was added to NRK52E cells followed by TGF-β1 treatment. This attenuated the induction of EMT and subsequent fibrogenesis associated with TGF-β1 treatment (Fig. 2D). EMT was also blocked by the TGF-β type 1 receptor antagonist SB431542 (Fig. 2E), as was the induction of TGF-β2.

FIG. 2.

TGF-β1-induced ECM gene and TGF-β2 expression changes in proximal tubular epithelial cells. A: NRK52E cells (Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium, 25 mmol/l glucose, 2% serum) were treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml, 3 days), and the expression of several genes was assessed by real-time QPCR. Significant changes are indicated (*P < 0.05 compared with control). B: The change in expression of TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 genes was assessed by real-time QPCR, and significant changes are indicated (*P < 0.0005 compared with control). C: TGF-β2 proteins levels were measured by ELISA and expressed as pg/mg (*P < 0.0005 compared with control). D: NRK52E cells were incubated with either control IgG (1 μg/ml) or TGF-β2-specific neutralizing antibody (1 μg/ml) for 1 h, and then TGF-β1 was added (10 ng/ml). Cells were harvested 3 days later and subjected to real-time QPCR analysis. The TGF-β2 antibody prevented the increased expression of αSMA, Collagen I, and fibronectin that is induced by TGF-β1, compared with the IgG control antibody (*P < 0.05 compared with control). E: Cells were then treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml, 3 days) in the presence or absence of SB432542, the TGF-β2 receptor inhibitor. Real-time QPCR analysis confirmed that the gene expression changes induced by TGF-β1 are attenuated by SB432542 (*P < 0.05 and #P < 0.001 compared with control).

TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 downregulate the expression of miR-200a.

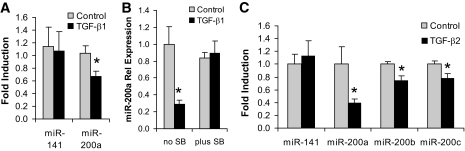

Treatment with TGF-β1 led to decreased expression of miR-200a (Fig. 3A) and miR-200b/c as previously reported (17). This downregulation of miR-200a by TGF-β1 was prevented by the TGF-β type 1 receptor antagonist SB431542 (Fig. 3B). NRK52E cells exposed to TGF-β2 (10 ng/ml) for 3 days also reduced the expression of miR-200a, miR-200b, and miR-200c (Fig. 3C), of which the decrease in miR-200a was the most pronounced. Neither TGF-β isoform resulted in a significant change in miR-141 expression, when compared with untreated cells.

FIG. 3.

TGF-β1-induced changes in miRNA expression. A: NRK52E cells were cultured in the presence of TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml, 3 days) before miRNA expression levels were assessed by real-time QPCR. A significant decrease was observed in miR-200a but not in miR-141 (*P < 0.03 compared with control). B: SB432542 also attenuated the TGF-β1-induced reduction of miR-200a (*P < 0.02 compared with control). C: Treatment of NRK52E cells with TGF-β2 (10 ng/ml, 3 days) also caused reduction in the expression of miR-200a, miR-200b, and miR-200c (*P < 0.05 compared with miR-control).

miR-200a downregulates the expression of ECM proteins.

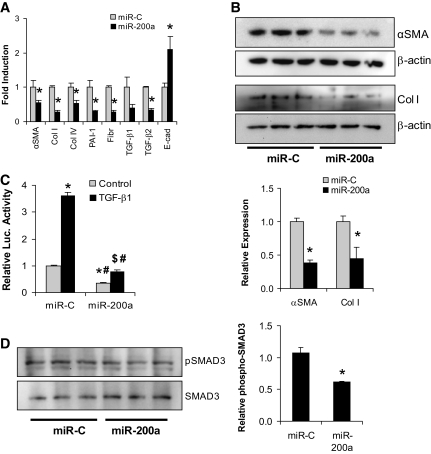

Ectopic expression of miR-200a after transfection with premiR-200a resulted in decreased expression of several ECM genes, including collagen I and IV and fibronectin, compared with premiRNA-control transfected NRK52E cells (Fig. 4A). Some of these changes in ECM protein expression were also observed at the protein level (Fig. 4B). miR-200a also caused reduced expression of the mesenchymal marker, αSMA, and increased expression of the epithelial marker, E-cadherin mRNA levels (Fig. 4A), consistent with previous reports that the miR-200 family targets the transcriptional repressors of E-cadherin, ZEB1, and ZEB2 (12,18–21). Finally the expression of PAI-1, a downstream target of TGF-β signaling, was also decreased (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

miR-200a represses the expression of ECM proteins. A: NRK52E cells were transfected with miR-200a (100 nmol/l), and RNA was harvested after 3 days for real-time QPCR analysis. miR-200a resulted in significantly decreased expression of several ECM proteins including αSMA, collagen (Col) I and IV, and fibronectin (Fibr) (*P < 0.05 compared with control transfected cells). Expression of TGF-β2 was also significantly decreased as was PAI-1, which is downstream of the TGF-β signaling pathway. The expression of E-cadherin (E-cad) was significantly elevated. B: Western analysis demonstrated a significant decrease in αSMA and collagen I by miR-200a, consistent with the RNA expression analysis (*P < 0.05 compared with control transfected cells). The Westerns were quantified and also shown in graph format below the Western blots (*P < 0.05 compared with control). C: NRK52E cells were cotransfected with the p(CAGA)12 SMAD3 activity reporter construct, a β-galactosidase construct, and miR-200a. Four h later, the cells were treated with TGF-β1, and cells were harvested after 3 days. TGF-β1 resulted in increased SMAD3 activity with miR-C, which was strongly inhibited by miR-200a (*P < 0.00005 compared with miR-C control; #P < 0.0005 compared with miR-C with TGF-β1; $P < 0.002 compared with miR-200a control). D: Western analysis of phospho-SMAD3 and total SMAD3 levels in miR-200a-transfected NRK52E demonstrating reduced SMAD3 phosphorylation relative to total SMAD3 protein (*P < 0.05 compared with miR-C control). The Westerns were quantified and shown in graph format (*P < 0.05 compared with miR-C).

Because the expression of many fibrotic genes is Smad3 dependent (22), we also investigated whether SMAD3 activity can be modulated by miR-200a. Interestingly, transfection with miR-200a was able to attenuate SMAD3 activity by 50% in the absence of exogenous TGF-β1 and totally abolished the activation of SMAD3 in the presence of TGF-β1 (Fig. 4C). This is also observed at the level of SMAD3 phosphorylation, which is reduced relative to total SMAD3 (Fig. 4D).

miR-141 downregulates the expression of ECM proteins.

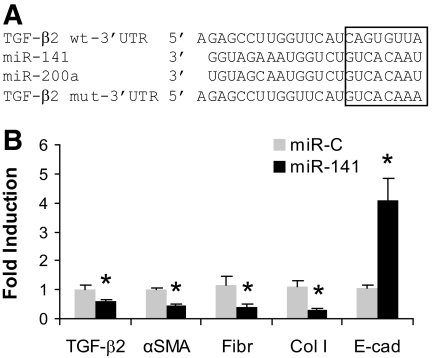

miR-141 shares the same seed sequence as miR-200a (Fig. 5A). To study the fibrogenic actions of miR-141, NRK52E cells were transfected with miR-141 and changes in gene expression were compared with premiRNA-control transfected NRK52E cells. As with miRNA-200a, miR-141 also reduced the expression of collagen I, fibronectin, αSMA, and TGF-β2 and increased the expression of E-cadherin (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

miR-141a shares the same seed sequence with miR-200a and represses the expression of ECM proteins. A: Alignment of the miR-141/200a sequences and the targeted area of the 3′UTR of TGF-β2 (http://www.targetscan.org). Also shown is the altered sequence of the mutant 3′UTR of TGF-β2. B: Proximal tubular cells were transfected with either miR-control or miR-141 (100 nmol/l), and the expression of certain genes was assessed by real-time QPCR. As with miR-200a, miR-141 was able to significantly reduce the expression of αSMA, fibronectin (Fibr), and collagen I (Col I) and resulted in increased expression of E-cadherin (E-cad) (*P < 0.05 compared with control). The expression of TGF-β2 was also significantly reduced.

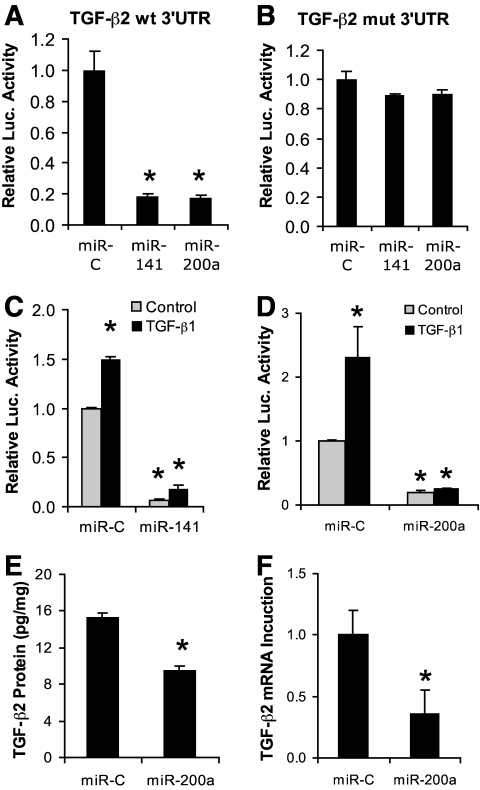

Both miR-141 and miR-200a repress the expression of TGF-β2.

The expression of TGFβ2 was also significantly decreased in miR-200a transfected cells (Fig. 4A). As miR-200a and TGF-β2 3′UTR share the same seed sequence as shown (Fig. 5A), we further investigated whether TGF-β2 is the direct target of miR-200a for translational repression. In these experiments we used luciferase reporter constructs incorporating a wild-type or mutant 3′UTR of TGF-β2 in which the sequence corresponding to the seed region was altered (Fig. 5A). Proximal tubular cells were cotransfected with the luciferase reporter constructs, a β-galactosidase construct, and either premiR-141, premiR-200a, or the premiR-control. This experiment demonstrated that both miR-141 and miR-200a directly repressed luciferase activity with the wild-type 3′UTR of TGF-β2 (Fig. 6A) but not with the mutant 3′UTR (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

The TGF-β2 3′UTR is regulated by miR-141/200a. A: NRK52E cells were transfected with TGF-β2 3′UTR luciferase reporter plasmid (1 μg), β-galactosidase plasmid (0.2 μg), and either miR-control (miR-C), miR-141, or miR-200a (100 nmol/l), and cells were analyzed for β-galactosidase and luciferase activity after 3 days. Both miR-141 and miR-200a were able to significantly repress luciferase activity from the TGF-β2 3′UTR (*P < 0.05 compared with control transfected cells). B: No activity of miR-141 and miR-200a against the mutant TGF-β2 3′UTR was observed. C: miR-141 and (D) miR-200a were able to prevent the increased luciferase activity induced by TGF-β1 on the TGF-β2 3′UTR. E: Total TGF-β2 was significantly decreased at the protein level as measured by ELISA and (F) at the mRNA level as measured by QPCR in NRK52E cells, 3 days after transfection with miR-200a (*P < 0.05, compared with control).

In separate experiments, cells were treated with TGF-β1 4 h after transfection. TGF-β1 significantly increased luciferase activity in cells transfected with the wild-type 3′UTR of TGF-β2 and miR-control (Fig. 6C and D). These data are consistent with our earlier observations demonstrating increased expression of TGF-β2 in response to TGF-β1 (Fig. 2B). When TGF-β1-treated cells were also transfected with either miR-141 (Fig. 6C) or miR-200a (Fig. 6D), the TGF-β1-induced increase in luciferase activity in cells with the wild-type 3′UTR of TGF-β2 was abolished. Consistent with these observations, transfection of cells with miR-200a reduced the expression of TGF-β2 gene and total TGF-β2 protein levels as demonstrated by ELISA and RT-PCR, respectively (Fig. 6E and F).

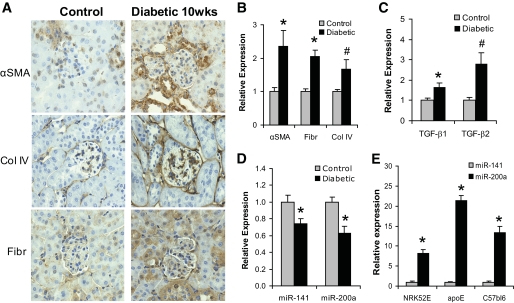

Decreased miR-141 and miR-200a in the kidneys from diabetic mice.

To further explore the relationship between miRNAs and diabetic kidney disease, we examined the expression of miR-141 and miR-200a in the cortex of kidneys from diabetic apoE KO mice. In this model, the combination of chronic hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia results in augmented renal fibrosis (14), similar to that seen in early diabetic renal disease in humans. As previously described, diabetes was associated with increased protein expression of αSMA, fibronectin, and Col IV when compared with nondiabetic controls (Fig. 7A). Real-time quantitative PCR (QPCR) confirmed changes in αSMA, Col IV, and fibronectin mRNA levels (Fig. 7B). In addition, a 1.6-fold increase in TGF-β1 and a 2.8-fold increase in TGF-β2 mRNA (Fig. 7C) were also observed in the cortex of kidneys from diabetic mice. Consistent with these changes, the gene expression levels of both miR-141 and miR-200a were also significantly reduced (Fig. 7D). Notably, the relative abundance of miR-200a was about 8–22-fold higher than that of miR-141 in tubular cells and kidney cortex (Fig. 7E).

FIG. 7.

Changes in gene and miR-200a expression in diabetic mouse kidney cortex. A: Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated increased expression for αSMA, collagen IV (Col IV), and fibronectin (Fibr) in the diabetic mouse kidney cortex compared with control. B: mRNA was extracted from the renal cortex of control and 10-week diabetic apoE mice (n = 8 per group). Gene expression was assessed by real-time QPCR for a number of genes, revealing significantly increased expression of αSMA, fibronectin, and collagen IV at the RNA level (*P < 0.01 and #P < 0.05 compared with control). C: Expressions of TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 were also elevated at the mRNA level in diabetic mouse kidney cortex (*P < 0.05 and #P < 0.01 compared with control). D: The increased expressions of TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 were associated with decreased expressions of miR-141 and miR-200a in diabetic kidney (*P < 0.05 compared with control). E: Relative expression levels of miR-141 and miR-200a in NRK52E cells and mouse kidney cortex. (*P < 0.005 compared with control). (A high-quality color representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

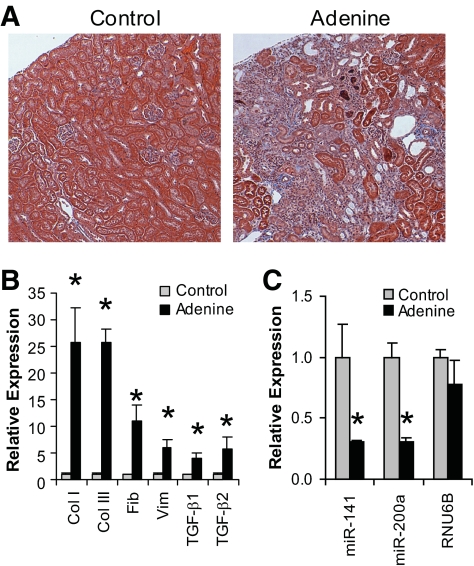

Decreased miR-141 and miR-200a in advanced kidney disease.

In further experiments we investigated the expression of ECM genes and miR-141/200a in the advanced renal disease associated with adenine-induced renal fibrosis. As previously described, exposure to adenine resulted in marked tubulointerstitial fibrosis (Fig. 8A, right panel) associated with a massive upregulation in the expression of ECM genes as well as the fibrogenic mediators TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 (Fig. 8B). Consistent with our earlier in vitro and in vivo observations, miR-200a was significantly decreased (Fig. 8C). miR-141 was also significantly reduced in this model.

FIG. 8.

Changes in miR-141/200a expression in the kidney in the adenine-induced renal fibrosis model. A: Trichrome staining of tissue sections from renal cortex from control and adenine-fed C57bl6 mice after 4 weeks of treatment. Blue staining indicates high levels of collagen in the adenine-fed mouse kidney compared with control. B: mRNA was extracted from the renal cortex of control and adenine-fed C57bl6 mice (n = 4 per group). Gene expression was assessed by real-time QPCR, revealing significantly increased expression of collagen I, collagen III, fibronectin, vimentin, TGF-β1, and TGF-β2. C: The increased expression of TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and collagen was associated with decreased expression of miR-141 and miR-200a but not the appropriate control, RNU6B, in kidney cortex (*P < 0.05 compared with control). (A high-quality color representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

DISCUSSION

MicroRNAs are now recognized to be key regulators of a number of important developmental, homeostatic, and pathogenic pathways. In this study, we demonstrate that miR-200a and miR-141 impact on the development and progression of TGF-β-dependent EMT and fibrosis in vitro. In particular, miR-200a and miR-141 are shown to be direct translational repressors of TGF-β2 by targeting the 3′UTR of this gene, as shown by experiments using a wild-type TGF-β2 3′UTR-luciferase construct. Furthermore, it was also demonstrated that miR-200a could prevent the TGF-β1-induced expression of TGF-β2 and other profibrotic changes, suggesting that it is an important downstream regulator of TGF-β1 signaling. Consistent with these findings in vitro, in early and more advanced models of kidney disease, the downregulation of both miR-200a and miR-141 were also associated with increased TGF-β expression and renal scarring.

Although a number of different factors contribute to renal scarring in the diabetic kidney, the best known and most studied prosclerotic mediator is TGF-β (6), which is increased in the diabetic kidney (9). Although all isoforms may have profibrotic actions in vitro, recent data points to the selective and predominant elevation of TGF-β2 as being particularly important in the diabetic kidney (8,11). In both our early and advanced models of renal fibrosis, the expression of TGF-β2 was markedly increased. Recent studies have demonstrated that specific targeting of TGF-β2 attenuates the development of renal fibrosis in diabetic models (6,10). Consistent with this hypothesis, we were able to reduce fibrogenesis in vitro, with a neutralizing antibody to TGF-β2 or alternatively by repressing TGF-β2 translation with miR-200a and miR-141.

EMT of mature tubular epithelial cells in the kidney (also known as type 2 EMT) (23) is now recognized as a contributor to the renal accumulation of matrix protein associated with diabetic nephropathy and is fundamentally linked to the progression of renal interstitial fibrosis. Recent evidence has demonstrated that a proportion of interstitial fibroblasts, the principal effector cells in this process, are derived from tubular epithelial cells in the diseased kidney via EMT (24). Furthermore, blockade of specific steps of EMT dramatically reduces fibrotic lesions in a number of models of kidney fibrosis, including diabetes, highlighting the important role of EMT in nephropathy. Although multiple signaling pathways and factors may play a role in different aspects of EMT, its most potent inducer is TGF-β1, which is able to initiate and complete the entire EMT process via SMAD recruitment as well as via non-SMAD pathways (4,25). In this study, we show that these actions require the induction of TGF-β2 after the downregulation of its translational repressors, miR-200a and miR-141. Although these studies have been performed in immortalized cells, in which expression of miRs and their targets may be different from primary cells lines, these findings are consistent with previous studies that have identified the miR-200 family of microRNAs as regulators of the epithelial cell phenotype and inhibitors of EMT in tumor models (12,19,20,26) and that point to miR-200a, in particular, as an important new target for the prevention of renal fibrogenesis. Given that reduced miR-200a levels are associated with increased ECM expression, and that restoring expression of miR-200a prevents many of the fibrotic changes in proximal tubular cells, miR-200a appears to play an important role in ECM accumulation and fibrosis. Indeed, the ability of miR-200a to attenuate SMAD3 activation has potential implications and could prove an attractive option for targeting fibrotic pathways at different levels.

Although we have shown that miR-200a and miR-141 specifically target the 3′UTR of TGF-β2, it is well known that some miRs are promiscuous and may bind the UTR regions of a number of different targets. Interaction with these other targets also has the potential to modify the responses to miRs observed in this study. For example, another important target of the miR-200 family are ZEB1 and ZEB2, themselves transcriptional repressors of E-cadherin in epithelial cells. By repressing the translation of ZEB1/2 in tumor models, the miR-200 family has been shown to protect epithelial cells against the action of pro-EMT factors such as TGF-β1 and promote mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (1,12). We have previously shown that another microRNA family, miR-192/215, which also acts as a translational repressor of ZEB2, does not modulate the expression of matrix proteins in response to TGF-β1 (17). Furthermore, mir-141 and miR-200a may not only work as translational repressors of target mRNAs, because they also caused a decrease in TGF-β2 mRNA levels. These findings confirm recent data demonstrating that some miRNAs can alter the mRNA levels of target genes (3). This ability is probably independent of the ability of these microRNAs to regulate the translation of target mRNAs.

At first glance, miRNA-200a would appear to be an attractive option for targeting renal fibrosis. Yet, while miR-200a exhibited significant antifibrotic effects in transfected cells, the therapeutic means of achieving this in vivo remain to be established, and the potential for off-target effects is considerable. Modulation of miRNAs using antisense inhibitors to block or mimics to enhance their activity may be one option, while other researchers are working on selective small-molecule inhibitors/activators of miRNA ligation. It is likely that better understanding of the role and activities of these antifibrotic miRNAs will provide novel means to inhibit renal fibrogenesis including in the context of diabetes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a Centre Grant from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC367620, NHMRC526663), as well as Kidney Health Australia (Bootle bequest). No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

B.W., P.Ko., A.M., A.W., K.J.-D., and W.C.B. researched data. C.W., M.C.T., and M.E.C. reviewed/edited the manuscript. M.T.C. researched data and reviewed/edited the manuscript. P.Ka. researched data and wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gregory PA, Bracken CP, Bert AG, Goodall GJ: MicroRNAs as regulators of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cell Cycle 2008;7:3112–3118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang X, Tsitsiou E, Herrick SE, Lindsay MA: MicroRNAs and the regulation of fibrosis. FEBS J 2010;277:2015–2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendrickson DG, Hogan DJ, McCullough HL, Myers JW, Herschlag D, Ferrell JE, Brown PO: Concordant regulation of translation and mRNA abundance for hundreds of targets of a human microRNA. PLoS Biol 2009;7:e1000238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns WC, Twigg SM, Forbes JM, Pete J, Tikellis C, Thallas-Bonke V, Thomas MC, Cooper ME, Kantharidis P: Connective tissue growth factor plays an important role in advanced glycation end product-induced tubular epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition: implications for diabetic renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006;17:2484–2494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan JM, Ng YY, Hill PA, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Mu W, Atkins RC, Lan HY: Transforming growth factor-beta regulates tubular epithelial-myofibroblast transdifferentiation in vitro. Kidney Int 1999;56:1455–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu L, Border WA, Huang Y, Noble NA: TGF-beta isoforms in renal fibrogenesis. Kidney Int 2003;64:844–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanford LP, Ormsby I, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Sariola H, Friedman R, Boivin GP, Cardell EL, Doetschman T: TGFbeta2 knockout mice have multiple developmental defects that are non-overlapping with other TGFbeta knockout phenotypes. Development 1997;124:2659–2670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sims-Lucas S, Caruana G, Dowling J, Kett MM, Bertram JF: Augmented and accelerated nephrogenesis in TGF-beta2 heterozygous mutant mice. Pediatr Res 2008;63:607–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill C, Flyvbjerg A, Grønbaek H, Petrik J, Hill DJ, Thomas CR, Sheppard MC, Logan A: The renal expression of transforming growth factor-beta isoforms and their receptors in acute and chronic experimental diabetes in rats. Endocrinology 2000;141:1196–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill C, Flyvbjerg A, Rasch R, Bak M, Logan A: Transforming growth factor-beta2 antibody attenuates fibrosis in the experimental diabetic rat kidney. J Endocrinol 2001;170:647–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ledbetter S, Kurtzberg L, Doyle S, Pratt BM: Renal fibrosis in mice treated with human recombinant transforming growth factor-beta2. Kidney Int 2000;58:2367–2376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gregory PA, Bert AG, Paterson EL, Barry SC, Tsykin A, Farshid G, Vadas MA, Khew-Goodall Y, Goodall GJ: The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat Cell Biol 2008;10:593–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennler S, Itoh S, Vivien D, ten Dijke P, Huet S, Gauthier JM: Direct binding of Smad3 and Smad4 to critical TGF beta-inducible elements in the promoter of human plasminogen activator inhibitor-type 1 gene. EMBO J 1998;17:3091–3100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lassila M, Jandeleit-Dahm K, Seah KK, Smith CM, Calkin AC, Allen TJ, Cooper ME: Imatinib attenuates diabetic nephropathy in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005;16:363–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terai K, Mizukami K, Okada M: Comparison of chronic renal failure rats and modification of the preparation protocol as a hyperphosphataemia model. Nephrology (Carlton) 2008;13:139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soro-Paavonen A, Watson AM, Li J, Paavonen K, Koitka A, Calkin AC, Barit D, Coughlan MT, Drew BG, Lancaster GI, Thomas M, Forbes JM, Nawroth PP, Bierhaus A, Cooper ME, Jandeleit-Dahm KA: Receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) deficiency attenuates the development of atherosclerosis in diabetes. Diabetes 2008;57:2461–2469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang B, Herman-Edelstein M, Koh P, Burns W, Jandeleit-Dahm K, Watson A, Saleem M, Goodall GJ, Twigg SM, Cooper ME, Kantharidis P: E-cadherin expression is regulated by miR-192/215 by a mechanism that is independent of the profibrotic effects of transforming growth factor-beta. Diabetes 2010;59:1794–1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christoffersen NR, Silahtaroglu A, Orom UA, Kauppinen S, Lund AH: miR-200b mediates post-transcriptional repression of ZFHX1B. Rna 2007;13:1172–1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korpal M, Lee ES, Hu G, Kang Y: The miR-200 family inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer cell migration by direct targeting of E-cadherin transcriptional repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. J Biol Chem 2008;283:14910–14914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paterson EL, Kolesnikoff N, Gregory PA, Bert AG, Khew-Goodall Y, Goodall GJ: The microRNA-200 family regulates epithelial to mesenchymal transition. ScientificWorldJournal 2008;8:901–904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burk U, Schubert J, Wellner U, Schmalhofer O, Vincan E, Spaderna S, Brabletz T: A reciprocal repression between ZEB1 and members of the miR-200 family promotes EMT and invasion in cancer cells. EMBO Rep 2008;9:582–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y: Renal fibrosis: new insights into the pathogenesis and therapeutics. Kidney Int 2006;69:213–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalluri R: EMT: when epithelial cells decide to become mesenchymal-like cells. J Clin Invest 2009;119:1417–1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwano M, Plieth D, Danoff TM, Xue C, Okada H, Neilson EG: Evidence that fibroblasts derive from epithelium during tissue fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2002;110:341–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oldfield MD, Bach LA, Forbes JM, Nikolic-Paterson D, McRobert A, Thallas V, Atkins RC, Osicka T, Jerums G, Cooper ME: Advanced glycation end products cause epithelial-myofibroblast transdifferentiation via the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE). J Clin Invest 2001;108:1853–1863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurteau GJ, Carlson JA, Spivack SD, Brock GJ: Overexpression of the microRNA hsa-miR-200c leads to reduced expression of transcription factor 8 and increased expression of E-cadherin. Cancer Res 2007;67:7972–7976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]