Abstract

Short non-lethal ischemic episodes administered to hearts prior to (ischemic preconditioning, IPC) or directly after (ischemic postconditioning, IPost) ischemic events facilitate myocardial protection. Transferring coronary effluent collected during IPC treatment to un-preconditioned recipient hearts protects from lethal ischemic insults. We propose that coronary IPC effluent contains hydrophobic cytoprotective mediators acting via PI3K/Akt-dependent pro-survival signaling at ischemic reperfusion. Ex vivo rat hearts were subjected to 30 min of regional ischemia and 120 min of reperfusion. IPC effluent administered for 10 min prior to index ischemia attenuated infarct size by ≥55% versus control hearts (P < 0.05). Effluent administration for 10 min at immediate reperfusion (reperfusion therapy) or as a mimetic of pharmacological postconditioning (remote postconditioning, RIPost) significantly reduced infarct size compared to control (P < 0.05). The IPC effluent significantly increased Akt phosphorylation in un-preconditioned hearts when administered before ischemia or at reperfusion, while pharmacological inhibition of PI3K/Akt-signaling at reperfusion completely abrogated the cardioprotection offered by effluent administration. Fractionation of coronary IPC effluent revealed that cytoprotective humoral mediator(s) released during the conditioning phase were of hydrophobic nature as all hydrophobic fractions with molecules under 30 kDa significantly reduced infarct size versus the control and hydrophilic fraction-treated hearts (P < 0.05). The total hydrophobic effluent fraction significantly reduced infarct size independently of temporal administration (before ischemia, at reperfusion or as remote postconditioning). In conclusion, the IPC effluent retains strong cardioprotective properties, containing hydrophobic mediator(s) < 30 kDa offering cytoprotection via PI3K/Akt-dependent signaling at ischemic reperfusion.

Keywords: Postconditioning, Preconditioning, Cardioprotection, Ischemia, Reperfusion, Akt

Introduction

Impaired coronary circulation caused by a myocardial ischemic episode will lead to compromised hemodynamic function and ultimately cell death. Rapid restoration of coronary blood flow to the infarct-related coronary artery by thrombolysis or primary coronary angioplasty is effective interventions for limiting myocardial infarct size and improving clinical outcomes [20, 39]. Although early reperfusion is essential to limit infarct size, it may paradoxically induce cell death (lethal reperfusion injury) [2]. Two ways of protecting the heart against reperfusion-induced injury are ischemic preconditioning (IPC) [22] and ischemic postconditioning (IPost) [40], applying transient non-lethal episodes of myocardial ischemia and reperfusion either before or after the index ischemic event, respectively. Another strategy for achieving cardioprotection is remote ischemic preconditioning (RIPC), whereby brief ischemia in one distant region or organ protects the heart from a sustained episode of ischemia [26]. Remote IPost (RIPost) is a more clinically relevant cardioprotective strategy, and has been shown to be effective in experimental studies when the remote ischemic conditioning was applied after the onset of myocardial ischemia [15].

There is strong evidence that one or more factors released in response to brief episodes of ischemia during IPC can interact with receptors, locally or at a distance, triggering a cytoprotective response. Dickson et al. [6] found that IPC-induced cardioprotection could be transferred between individuals by transfusion of whole blood from preconditioned to non-preconditioned rabbits and that effluent from preconditioned isolated ex vivo rabbit hearts offered protection to non-preconditioned hearts [5]. Furthermore, Serejo et al. [28] recently showed that cardioprotective factors released into coronary IPC effluent from ex vivo rat hearts are thermolabile hydrophobic substances with molecular weights higher than 3.5 kDa offering cytoprotection via PKC activation in the recipient heart. In addition, Lang et al. [17] suggested that mediator(s) released during IPC in rat hearts are smaller than 8 kDa.

IPC and IPost reduce infarct size when studied in a wide variety of experimental models including rat, rabbit, dog, pig and primates by sharing similar mechanisms and exerting most of their cytoprotection at reperfusion [9, 12, 26, 37]. IPC activates PI3-kinase which facilitates phosphorylation and activation of the protein kinase Akt through its mediator PDK-1 [1]. Akt is part of the reperfusion injury salvage kinases (RISK) that confer cardioprotection when activated at reperfusion [9]. IPost activates similar signaling pathways to IPC [9] and is thereby also dependent on RISK activation to exert its protection [35], although the involvement of RISK has lately been proven to be species dependent [27, 30]. The underlying mechanism of RIPC and RIPost remains unclear, but many of the signaling pathways underlying myocardial preconditioning and postconditioning have been implicated in RIPC [11].

Numerous studies have focused on characterizing the signaling mechanisms involved in IPC. However, the precise adaptive response triggered by agents released during the short reperfusion episodes of IPC remains unresolved. Identification of such mediators would be of great importance for the development of pharmacological therapies to enhance myocardial tolerance to ischemia–reperfusion-induced stress in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) [38]. The aims of this study were therefore to (1) investigate the protective capabilities of the IPC effluent when delivered at ischemic reperfusion and its potential to induce remote postconditioning (RIPost); (2) determine if coronary IPC effluent mediates its protection through a PI3K/Akt-dependent cytoprotective signaling pathway; (3) characterize the protective mediator(s) by fractionation of effluent based on different properties such as hydrophobicity and size.

Methods

Langendorff perfusion procedure

All experiments were approved by the Norwegian State Commission for Laboratory Animals, and carried out in accordance with the European Communities Council Directive of 1986 (86/609/EEC).

Male Wistar rats (250–350 g, n = 183) fed a standard diet were heparinized (200 IU) and anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) i.p. The hearts were excised, placed in ice-cold Krebs–Heinseleit buffer (KHB) and rapidly mounted onto a Langendorff perfusion system. KHB (pH 7.4, oxygenated with 95% O2/5% CO2) contained in mM: 118 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.2 KH2·PO4, 1.2 MgSO4, 25.2 NaHCO3, 11.0 glucose. Perfusion pressure was maintained at 100 cmH2O, and the myocardial temperature kept at 37.5°C. A water-filled latex balloon, connected to a hydrostatic pressure transducer (SP844, Memscap, Norway) and coupled to a high performance data acquisition system (PowerLab 8/30, Chart Pro software-MLS250, Australia), was inserted into the left ventricle and inflated to set an end-diastolic pressure of 5–10 mmHg. Coronary flow (CF) was measured by timed collection of effluent over 1 min. A 3-0 silk suture was passed around the main branch of the left coronary artery, and threaded through a small vinyl tube to form a snare. Regional ischemia (RI) was achieved by pulling the snare, and confirmed by a substantial fall in left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP) and CF.

Experimental protocols

The experimental protocols are shown in Fig. 1. Baseline values for functional parameters were obtained after 10 min of stabilization. All hearts were subjected to the ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) protocol consisting of 30 min of regional ischemia (RI = index ischemia) and 120 min of reperfusion. The IPC protocol consisted of 3× 5 min of global ischemia (GI) with 5 min intermittent reperfusions prior to RI. Coronary IPC effluent (~150 ml) was collected during the intermittent reperfusion periods. Fresh effluent was used for each experiment. Since studies show that coronary effluent from non-preconditioned hearts does not influence the infarct size when administered to recipient hearts [28], we did not repeat these experiments in this study.

Fig. 1.

Experimental protocols. All groups were subjected to 30 min of regional ischemia (RI) followed by 120 min of reperfusion. Hearts receiving no other treatments constitute the control group (Ctr). a The IPC group was exposed to 3× 5 min global ischemia (GI), with 5 min intermittent reperfusion periods prior to RI. To test the temporal cytoprotective efficacy of IPC effluent in recipient hearts, freshly collected effluent was administered for 10 min prior to RI (EffPre) or for 10 min at onset of ischemic reperfusion (EffRep). Furthermore, to mimic ischemic postconditioning, the IPC effluent was administered for 3× 30 s with 30 s intermittent KHB perfusion at immediate reperfusion (EffPost). Ischemic postconditioning (IPost) was achieved by 3× 30 s of global ischemia (GI) at early ischemic reperfusion. The PI3K-inhibitor WI (1 μM) and the Akt-inhibitor SH-6 (10 μM) were administered for 10 min at immediate onset of ischemic reperfusion in conjunction with 10 min of pre- or post-ischemic treatment with IPC effluent (EffPre + WI/SH-6, EffRep + WI/SH-6 or EffPost + WI). b The IPC effluent was fractionated in respect to charge and size. Effluent collected during IPC was first separated into a hydrophilic (HPhil) and a hydrophobic (HPhob) fraction. All total effluent fractions were administered for either 10 min prior to ischemia (HPhilPre and HPhobPre) or for 10 min at reperfusion (HPhobRep and HPhobPost). The hydrophobic fraction was further fractionated by a 10 or 30 kDa size filter resulting in four hydrophobic fractions with molecules below 10/30 kDa (HPhobPre < 10 and HPhobRep < 30) or above 10/30 kDa (HPhobPre > 10 and HPhobRep > 30). Arrows indicate time points for tissue sampling. Solid lines KH buffer perfusion

Initially, effects of coronary IPC effluent were studied during two temporal distinct administration periods, before and after index ischemia (Fig. 1a). IPC effluent was administered 10 min prior to index ischemia (EffPre) and for 10 min at reperfusion (EffRep). Subsequently, IPC effluent was administered to simulate ischemic postconditioning (RIPost) by perfusing the coronary effluent for 3× 30 s at early reperfusion (EffPost). The ischemic postconditioning (IPost) protocol consisted of 3× 30 s GI intermitted by 30 s reperfusion periods. Furthermore, to explore if the cardioprotective properties mediated by the coronary IPC effluent were dependent on PI3K/Akt-dependent signaling at reperfusion, the PI3K-inhibitor Wortmannin (WI; 1 μM) (Tocris Bioscience, UK) and the Akt-inhibitor SH-6 (10 μM) (Enzo Life Sciences, New York, USA) were administered for 10 min at ischemic reperfusion (EffPre + WI/SH-6 and EffRep + WI/SH-6 and EffPost + WI; Fig. 1a). Since WI attenuated the cytoprotective effect of the effluent administered as a RIPost stimulus, and further that SH-6 abolished the IPC effluent-induced cardioprotection at reperfusion, we did not include experiments with effluent RIPost and the SH-6 inhibitor.

To further delineate the properties of putative cytoprotective mediator(s) released into collected IPC effluent, another set of experiments was performed (Fig. 1b). Firstly, effluent was separated into hydrophilic and hydrophobic fractions and administered either prior to ischemia (HPhilPre and HPhobPre) or at reperfusion (HPhobRep and HPhobPost). The hydrophobic effluent was further fractionated using spin columns containing cut-off filters of either 10 or 30 kDa, resulting in four different fractions that were administered to recipient hearts either prior to ischemia (HPhobPre < 10 and HPhobPre > 10) or at reperfusion (HPhobRep < 30 and HPhobRep > 30).

Fractionation of IPC effluent

Coronary effluent from isolated ex vivo Langendorff perfused rat hearts exposed to IPC was collected during the intermittent reperfusion periods. The effluent was taken through a series of preparation steps in order to purify putative mediators of IPC-mediated cardioprotection. C18 solid phase extraction cartridges (Waters Corp., USA) were conditioned with 6 ml 100% acetonitrile (ACN) followed by equilibration with 6 ml of ddH2O. Thereafter, IPC effluent was applied to the cartridge at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Following this, the cartridge was washed with 10 ml water to elute unbound hydrophilic compounds (hydrophilic fraction). Hydrophobic proteins were eluted with 6 ml of 60% ACN. To remove the organic phase, eluted sample was evaporated under a stream of nitrogen. The hydrophobic eluted fraction was then either re-suspended in KHB for perfusion or re-suspended in ddH2O and subjected to spin columns with either 10 or 30 kDa cut-off filter (Sartorius Stedim Biotech, France) and thereafter diluted in KHB (total volume of 150 ml KHB) before perfusion. All fractions were perfused to untreated recipient hearts for 10 min either prior to index ischemia (HPhilPre or HPhobPre) or at reperfusion (HPhobRep or HPhobPost) (Fig. 1b).

Determination of infarct size

At the end of each experiment, the silk suture was securely tightened and a 0.2% (w/v) Evans Blue solution (Sigma Chemicals Co., USA) infused to visualize the risk zone. Hearts were thereafter frozen at −20°C before being cut into 2-mm thick slices parallel to the atrioventricular groove and stained with 1% triphenyl-tetrazolium-chloride (TTC, Sigma Chemicals Co, USA) in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 20 min at 37°C. The slices were then immersed in 4% (v/v) formalin to enhance contrast of the stain, before being placed between two glass plates and digitalized. Area at risk (AAR, i.e. area not stained by Evans Blue), live cells (TTC positive, i.e. red) and infarcted area (TTC negative) were determined in a blinded fashion using a computerized planimetry program (Planimetry+ v2.0; Erik Traasdahl, ENK, Norway). Infarct size is presented as the ratio between the infarcted area and AAR in percent. There were no significant differences between the different treatment groups in the relative size of the AAR (volume of area at risk/volume of left ventricle) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ratio of volume of area at risk (AAR) and left ventricle (LV) by Evans Blue staining

| Group | AAR/LV |

|---|---|

| Ctr | 0.43 ± 0.03 |

| Ctr + WI | 0.53 ± 0.06 |

| Ctr + SH-6 | 0.41 ± 0.04 |

| IPC | 0.46 ± 0.02 |

| EffPre | 0.50 ± 0.03 |

| EffPre + SH-6 | 0.48 ± 0.04 |

| EffPre + WI | 0.34 ± 0.03 |

| EffRep | 0.39 ± 0.03 |

| EffRep + SH-6 | 0.36 ± 0.03 |

| EffRep + WI | 0.47 ± 0.02 |

| IPost | 0.52 ± 0.03 |

| EffPost | 0.46 ± 0.03 |

| EffPost + WI | 0.43 ± 0.05 |

| HPhilPre | 0.42 ± 0.03 |

| HPhobPre | 0.43 ± 0.09 |

| HPhobRep | 0.39 ± 0.05 |

| HPhobPost | 0.36 ± 0.04 |

| HPhobPre < 10 | 0.43 ± 0.03 |

| HPhobPre > 10 | 0.45 ± 0.02 |

| HPhobRep < 30 | 0.45 ± 0.03 |

| HPhobRep > 30 | 0.46 ± 0.01 |

Values represent mean ± SEM

Ctr ischemia–reperfusion controls; IPC ischemic preconditioning, 3× 5 min; Eff Pre/HPhob Pre 10 min effluent administration prior to ischemia; Eff Rep/HPhob Rep 10 min effluent administration at reperfusion; IPost ischemic postconditioning, 3× 30 s; Eff Post/HPhob Post postconditioning mimetic, 3× 30 s; WI 10 min Wortmannin (1 μM); SH-6 10 min SH-6 (10 μM) at reperfusion; HPhil effluent not bound to C18 column; HPhob total effluent eluted from C18 column; < or >10 or 30 kDa total hydrophobic fraction further separated by size exclusion column

Immunoblot analysis

Levels of Akt (total-Akt, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, California, USA) and its phosphorylation at Ser473 (p-Akt, Cell Signal, Massachusetts, USA) were determined by western blotting. Heart tissue was harvested at stabilization (control baseline, C B), at the end of IPC protocol or at 15 min of reperfusion (time points indicated by arrow in Fig. 1a). Furthermore, in order to explore the potential of pre-ischemic effluent administrations ability to modulate Akt phosphorylation at reperfusion, a separate group for WB only were administered effluent for 10 min prior to index ischemia and the tissue harvested after these hearts had been reperfused for 15 min (EffPre+Rep). At the end of the experiment, AAR of the left ventricle was excised and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Homogenization of cardiac tissue, protein quantification, sample preparation (40 μg per lane) and electrophoresis were performed as previously described [14]. Densitometric analysis was performed using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) and phosphorylation of Akt was expressed as the ratio between p-Akt and total-Akt. Results normalized against baseline hearts, C B. GADPH was used as loading control (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, California, USA).

Statistical analysis

Values are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Infarct sizes and AAR were tested for group differences by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) combined with Fisher’s post hoc test. Comparisons of LVDP, HR and CF were performed with ANOVA combined with Bonferroni post hoc test. To test for immunoblot differences, Student’s t test for independent samples was used. For all tests, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

IPC effluent induces remote postconditioning by reducing infarct size when administered at reperfusion

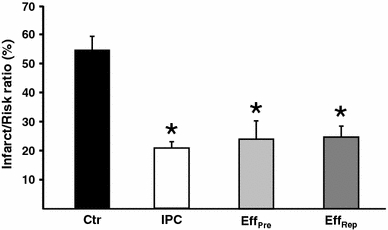

Administration of IPC effluent from the onset of reperfusion significantly reduced infarct size in un-preconditioned recipient hearts compared to controls (EffRep: 25 ± 4% vs. Ctr: 54 ± 5%, P < 0.05; Fig. 2). Furthermore, the infarct size reduction was comparable to that of hearts subjected to ischemic preconditioning (IPC) or treated with IPC effluent prior to index ischemia (EffPre) (IPC: 21 ± 2%, EffPre: 24 ± 6% vs. EffRep: 25 ± 4%, ns; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The temporal effect of treatment with IPC effluent on myocardial infarct size. Infarct size is expressed as percentage of the region at risk of infarction (area at risk). Effluent from preconditioned donor hearts (IPC) administered either 10 min prior to index ischemia (EffPre) or for 10 min at ischemic-reperfusion (EffRep) significantly reduced infarct size in non-preconditioned recipient hearts as compared to controls (Ctr). Bars represent mean ± SEM. N ≥ 7 in each group. *P < 0.05 versus Ctr group

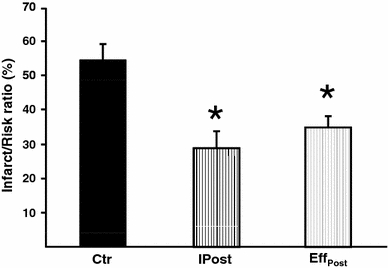

In addition, mimicking pharmacological postconditioning by administering IPC effluent to recipient hearts for 3× 30 s at onset of reperfusion (RIPost) significantly reduced infarct size as compared to control hearts (EffPost: 35 ± 3% vs. Ctr: 54 ± 5%, P < 0.05; Fig. 3). There was no statistical difference in infarct size comparing the IPost and EffPost groups (IPost: 30 ± 5% vs. EffPost: 35 ± 3%, ns; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The effect of administering IPC effluent as a mimetic of ischemic postconditioning (RIPost) on myocardial infarct size. Treatment of recipient hearts with IPC effluent for 3× 30 s at ischemic reperfusion (EffPost) reduced infarct size to the same extent as ischemic postconditioning (IPost), and both groups had significantly reduced infarct size as compared to the control group (Ctr). Bars represent mean ± SEM. N ≥ 7 in each group. *P < 0.05 versus Ctr

Lastly, comparing the infarct sizes in all IPC effluent-treated groups, it is apparent that the effluent confers similar degree of cytoprotection independent of whether treatment was administered before or after the index ischemic insult (EffPre: 24 ± 6%, EffRep: 25 ± 4% and EffPost: 35 ± 3%, ns; Figs. 2, 3). Furthermore, coronary IPC effluent conveys cardioprotection comparable to IPC hearts, revealing that the putative cytoprotective mediator(s) could lead to a very promising therapeutic strategy for patients being revascularized after AMI.

The cytoprotection offered by IPC effluent at reperfusion is mediated by PI3K/Akt-dependent cell-survival signaling in recipient heart

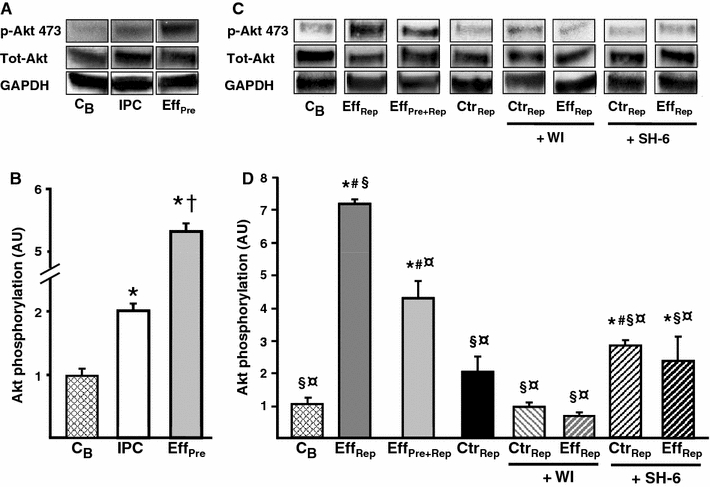

IPC is known to activate the pro-survival kinase Akt directly after the IPC protocol [34]. Interestingly, administration of IPC effluent prior to index ischemia caused a significant increase in Akt phosphorylation compared to hearts exposed to IPC treatment only (EffPre: 5.2 ± 0.2 AU vs. IPC: 2.0 ± 0.2 AU, P < 0.05; Fig. 4a, b), indicating an increased potential of the IPC effluent to activate the pro-survival Akt-signaling as compared to the IPC stimulus itself. Furthermore, administration of IPC effluent at reperfusion elevated the Akt-phosphorylation compared to I/R control hearts (EffRep: 7.2 ± 0.2 AU vs. CtrRep: 2.0 ± 0.5 AU, P < 0.05; Fig. 4c, d). Treatment with pre-ischemic IPC effluent and analysis of Akt phosphorylation at reperfusion (EffPre+Rep) also increased phosphorylation status of Akt as compared to the I/R control group (EffPre+Rep: 4.2 ± 0.6 AU vs. CtrRep: 2.0 ± 0.5 AU, P < 0.05; Fig. 4c, d).

Fig. 4.

Phosphorylation status of myocardial Akt in recipient hearts exposed to treatment with IPC effluent. a Representative immunoblots of Akt phosphorylation (Ser473) showing the effects of treatment with IPC effluent (EffPre) in recipient hearts (tissue harvested at end of treatment), as compared to hearts exposed to the standard IPC protocol (IPC) and baseline hearts (C B). c Representative immunoblots of Akt phosphorylation (Ser473) in pre-ischemic IPC effluent-treated hearts that was also reperfused for 15 min (EffPre+Rep) and reperfusion treatment with IPC effluent (EffRep) in recipient hearts as compared to ischemic reperfused control hearts (CtrRep) (tissues harvested at 15 min of reperfusion). Administering the PI3K-inhibitor WI (1 μM) and the Akt-inhibitor SH-6 (10 μM) for 10 min at reperfusion abrogated Akt phosphorylation in IPC effluent-treated hearts. Total Akt and GADPH indicates equal loading. b, d Densitometric analysis of total and phosphorylated Akt immunoblots expressed in arbitrary units (AU). p-Akt expressed as a ratio of total Akt with C B = 1. Bars represent mean ± SEM. N ≥ 3 in each group. *P < 0.05 versus C B, † P < 0.05 versus IPC, § P < 0.05 versus EffPre+Rep, ¤ P < 0.05 versus EffRep, # P < 0.05 versus CtrRep

Total Akt or GADPH did not alter during the experiments (Fig. 4a, c), implying that increased relative phosphorylation is a result of changes in Akt phosphorylation and not alterations in the total kinase level or unequal loading. Exploring the phosphorylation status of STAT-3, a member of the Survivor Activating Factor Enhancement (SAFE) pathway [18], we found no regulation (results not shown).

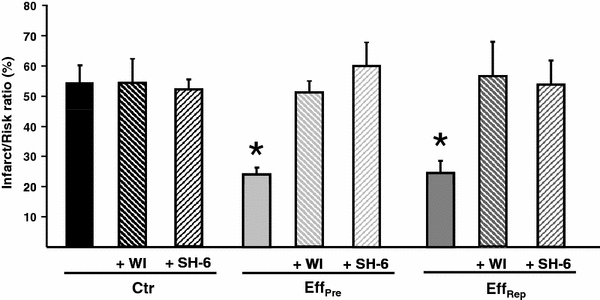

Hausenloy et al. [9] have previously shown that Akt phosphorylation at reperfusion is essential for IPC-induced protection, since inhibition of this kinase during early reperfusion abrogated the IPC-mediated reduction in infarct size. Therefore, to elucidate whether IPC effluent exerts its cardioprotective effect through an PI3K/Akt-dependent signaling pathway activated at reperfusion, hearts were administered fresh IPC effluent for 10 min either prior to index ischemia (EffPre) or at reperfusion (EffRep or EffPost), and co-administered the PI3K-inhibitor WI or the Akt-inhibitor SH-6 for 10 min at reperfusion (see experimental protocol Fig. 1). The protective effect of IPC effluent was completely abolished by co-administering WI or SH-6 at reperfusion compared to the EffPre group (EffPre + WI: 51 ± 7%, EffPre + SH-6: 60 ± 4% vs. EffPre: 24 ± 6%, P < 0.05; Fig. 5) and the EffRep group (EffRep + WI: 56 ± 12%, EffRep + SH-6: 54 ± 8% vs. EffRep: 25 ± 4%, P < 0.05; Fig. 5) and EffPost group (EffPost + WI: 50 ± 11% vs. EffPost; 35 ± 3%, P < 0.05) (data not shown). SH-6 is a phosphatidylinositol (PI) analog that inhibits Akt without affecting the activity of its upstream kinase PDK-1 [16], and has also been shown to prevent phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 [4, 32]. The inhibitors themselves had no effect on infarct size (WI: 54 ± 8%, SH-6: 52 ± 3% vs. Ctr: 54 ± 5%, ns). Furthermore, both WI and SH-6 significantly reduced Akt phosphorylation in IPC effluent-treated hearts (EffRep + WI: 0.7 ± 0.1 AU, EffRep + SH-6: 2.8 ± 0.2 AU vs. EffRep: 7.2 ± 0.2 AU, P < 0.05; Fig. 4c, d).

Fig. 5.

The effect of inhibiting PI3K and Akt upon reperfusion in IPC effluent-treated recipient hearts. When administering the PI3K-inhibitor WI and the Akt-inhibitor SH-6 at the onset of reperfusion in IPC effluent pre-ischemic (EffPre) or post-ischemic (EffRep and EffPost) treated hearts, the cardioprotective effect of the effluent was completely abolished. Ctr control; Eff Pre 10 min effluent administration prior to RI; Eff Rep 10 min effluent administration after RI; Eff Post effluent administration 3× 30 s at start of reperfusion; WI 10 min Wortmannin (1 μM) at reperfusion; SH-6 10 min SH-6 (10 μM) at reperfusion. Bars represent mean ± SEM. N ≥ 6 in each group. *P < 0.05 versus Ctr

Functional parameters are shown in Tables 2 and 3. There were no major group differences concerning baseline values, values at the start of RI or at reperfusion (Tables 2, 3).

Table 2.

Functional parameters recorded during the experimental protocol investigating the temporal effects of administering the IPC effluent to un-preconditioned recipient hearts

| Group | 10 min stab | 5 min RI | 30 min rep | 120 min rep |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVDP (mmHg) | ||||

| Ctr | 155 ± 22 | 87 ± 8# | 109 ± 12 | 78 ± 8# |

| Ctr + WI | 160 ± 12 | 73 ± 11# | 71 ± 9 | 67 ± 6# |

| Ctr + SH-6 | 149 ± 17 | 78 ± 13# | 112 ± 9# | 84 ± 10# |

| IPC | 160 ± 11 | 73 ± 7# | 98 ± 7# | 70 ± 5# |

| EffPre | 171 ± 21 | 73 ± 14# | 87 ± 2# | 67 ± 5# |

| EffPre + SH-6 | 177 ± 17 | 113 ± 11# | 68 ± 8# | 51 ± 3# |

| EffPre + WI | 148 ± 12 | 73 ± 9# | 81 ± 7# | 66 ± 6# |

| EffRep | 177 ± 9 | 84 ± 14# | 104 ± 10# | 77 ± 9# |

| EffRep + SH-6 | 156 ± 8 | 103 ± 9# | 93 ± 7# | 74 ± 6# |

| EffRep + WI | 162 ± 17 | 111 ± 18# | 97 ± 18# | 69 ± 13# |

| IPost | 150 ± 10 | 68 ± 11# | 78 ± 9# | 59 ± 7# |

| EffPost | 157 ± 19 | 80 ± 14# | 106 ± 9 | 61 ± 8# |

| EffPost + WI | 156 ± 11 | 99 ± 15# | 94 ± 15# | 85 ± 10# |

| CF (ml/min) | ||||

| Ctr | 13.4 ± 1.7 | 9.1 ± 1.3# | 9.1 ± 0.8# | 6.2 ± 0.7# |

| Ctr + WI | 12.9 ± 0.6 | 7.3 ± 0.6# | 10.5 ± 0.8 | 7.3 ± 0.6# |

| Ctr + SH-6 | 12.8 ± 0.4 | 7.9 ± 0.4# | 6.2 ± 1.6# | 6.1 ± 1.1# |

| IPC | 14.2 ± 0.9 | 8.0 ± 0.7# | 12.1 ± 1.1 | 7.3 ± 0.9# |

| EffPre | 13.3 ± 0.5 | 6.9 ± 0.8# | 8.0 ± 0.5# | 6.5 ± 0.6# |

| EffPre + SH-6 | 17.2 ± 3.2 | 8.7 ± 1.2# | 6.8 ± 0.8# | 6.2 ± 1.1# |

| EffPre + WI | 15.8 ± 1.5 | 7.8 ± 0.8# | 10.8 ± 1.0# | 7.1 ± 1.0# |

| EffPre | 13.6 ± 1.0 | 8.1 ± 1.0# | 10.2 ± 0.4# | 7.5 ± 0.4# |

| EffPre + SH-6 | 14.9 ± 0.9 | 8.9 ± 0.9# | 7.8 ± 0.6# | 6.5 ± 0.6# |

| EffRep + WI | 15.6 ± 0.6 | 7.6 ± 1.1# | 9.3 ± 1.5# | 7.1 ± 1.4# |

| IPost | 12.3 ± 0.8 | 7.2 ± 0.5# | 8.2 ± 0.9# | 5.9 ± 0.3# |

| EffPost | 13.8 ± 0.7 | 8.4 ± 0.6# | 10.4 ± 0.7# | 7.6 ± 0.6# |

| EffPost + WI | 14.1 ± 0.6 | 8.9 ± 0.8# | 11.4 ± 0.9 | 8.7 ± 0.4# |

| HR (beats/min) | ||||

| Ctr | 328 ± 21 | 294 ± 34 | 268 ± 31 | 254 ± 17 |

| Ctr + WI | 300 ± 12 | 288 ± 12 | 258 ± 43 | 293 ± 23 |

| Ctr + SH-6 | 318 ± 17 | 276 ± 16 | 299 ± 18 | 246 ± 15 |

| IPC | 295 ± 22 | 283 ± 17 | 270 ± 13 | 242 ± 9 |

| EffPre | 321 ± 12 | 278 ± 19 | 285 ± 15 | 270 ± 14 |

| EffPre + SH-6 | 294 ± 18 | 250 ± 11 | 236 ± 11 | 226 ± 29 |

| EffPre + WI | 297 ± 13 | 298 ± 25 | 339 ± 23 | 289 ± 23 |

| EffRep | 275 ± 23 | 273 ± 15 | 276 ± 19 | 268 ± 14 |

| EffRep + SH-6 | 256 ± 17 | 238 ± 17 | 224 ± 17 | 236 ± 12 |

| EffRep + WI | 277 ± 32 | 248 ± 30 | 261 ± 30 | 241 ± 28 |

| IPost | 298 ± 15 | 266 ± 13 | 261 ± 9 | 233 ± 6 |

| EffPost | 280 ± 7 | 230 ± 16 | 293 ± 15 | 239 ± 14 |

| EffPost + WI | 316 ± 16 | 304 ± 24 | 301 ± 23 | 278 ± 33 |

Values represent mean ± SEM

Ctr ischemia–reperfusion controls; IPC ischemic preconditioning, 3× 5 min; Eff Pre 10 min effluent administration prior to ischemia; Eff Rep 10 min effluent administration at reperfusion; IPost ischemic postconditioning, 3× 30 s; Eff Post effluent postconditioning, 3× 30 s; WI 10 min Wortmannin (1 μM); SH-6 10 min SH-6 (10 μM) at reperfusion

# P < 0.05 versus Stab

Table 3.

Functional parameters recorded during the experimental protocol investigating the effects of administering fractionated IPC effluent (charge and size) to un-preconditioned recipient hearts

| Group | 10 min stab | 5 min RI | 30 min rep | 120 min rep |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVDP (mmHg) | ||||

| Ctr | 155 ± 22 | 87 ± 8# | 109 ± 12 | 78 ± 8# |

| HPhilPre | 153 ± 9 | 87 ± 8# | 96 ± 9# | 69 ± 9# |

| HPhobPre | 151 ± 6 | 89 ± 18# | 100 ± 5# | 87 ± 5# |

| HPhobRep | 168 ± 20 | 89 ± 8# | 90 ± 16 | 71 ± 11# |

| HPhobPost | 143 ± 8 | 78 ± 8# | 90 ± 5# | 73 ± 5# |

| HPhobPre < 10 | 143 ± 15 | 62 ± 9# | 101 ± 8# | 74 ± 7# |

| HPhobPre > 10 | 149 ± 13 | 81 ± 13# | 111 ± 9 | 83 ± 7# |

| HPhobRep < 30 | 173 ± 9 | 83 ± 8# | 107 ± 5# | 82 ± 5# |

| HPhobRep > 30 | 160 ± 15 | 100 ± 13# | 83 ± 6# | 64 ± 7# |

| CF (ml/min) | ||||

| Ctr | 13.2 ± 1.4 | 8.8 ± 1.2# | 8.6 ± 0.8# | 5.8 ± 0.7# |

| HPhilPre | 13.6 ± 0.5 | 8.4 ± 0.8# | 10.2 ± 0.9 | 7.6 ± 0.8# |

| HPhobPre | 13.7 ± 0.5 | 8.2 ± 2.4# | 9.9 ± 2.7# | 7.9 ± 1.9# |

| HPhobRep | 16.4 ± 0.7 | 10.6 ± 0.5# | 12.2 ± 1.3 | 10.4 ± 1.5*,# |

| HPhobPost | 13.2 ± 1.1 | 7.6 ± 1.0# | 9.7 ± 1.3 | 7.9 ± 1.1# |

| HPhobPre < 10 | 14.6 ± 1.6 | 7.4 ± 1.2# | 11.9 ± 1.5# | 9.4 ± 1.3# |

| HPhobPre > 10 | 14.3 ± 0.9 | 7.3 ± 1.0# | 11.5 ± 1.1 | 8.6 ± 0.8# |

| HPhobRep < 30 | 17.1 ± 1.0 | 10.0 ± 2.1# | 11.8 ± 2.4# | 9.7 ± 2.2# |

| HPhobRep > 30 | 15.4 ± 1.1 | 9.1 ± 0.7# | 10.3 ± 0.9# | 8.0 ± 0.7# |

| HR (beats/min) | ||||

| Ctr | 320 ± 15 | 291 ± 24 | 249 ± 23 | 230 ± 24 |

| HPhilPre | 299 ± 13 | 265 ± 27 | 257 ± 16 | 266 ± 16 |

| HPhobPre | 306 ± 11 | 283 ± 15 | 299 ± 12 | 265 ± 7 |

| HPhobRep | 330 ± 13 | 312 ± 5 | 315 ± 11 | 304 ± 9 |

| HPhobPost | 329 ± 26 | 339 ± 18 | 334 ± 18 | 328 ± 17* |

| HPhobPre < 10 | 294 ± 10 | 264 ± 13 | 287 ± 15 | 269 ± 10 |

| HPhobPre > 10 | 298 ± 11 | 274 ± 6 | 274 ± 8 | 287 ± 10 |

| HPhobRep < 30 | 303 ± 10 | 272 ± 6 | 255 ± 28 | 253 ± 28 |

| HPhobRep > 30 | 290 ± 15 | 273 ± 14 | 241 ± 19 | 234 ± 18 |

Values represent mean ± SEM

Ctr ischemia–reperfusion controls; IPC ischemic preconditioning, 3× 5 min; Eff Pre/HPhob Pre 10 min effluent administration prior to ischemia; Eff Rep/HPhob Rep 10 min effluent administration at reperfusion; IPost ischemic postconditioning, 3× 30 s; Eff Post/HPhob Post postconditioning mimetic, 3× 30 s; WI 10 min Wortmannin (1 μM); SH-6 10 min SH-6 (10 μM) at reperfusion. HPhil effluent not bound to C18 column; HPhob total effluent eluted from C18 column; < or >10 or 30 kDa total hydrophobic fraction further separated by size exclusion column

* P < 0.05 versus Ctr, # P < 0.05 vs. Stab

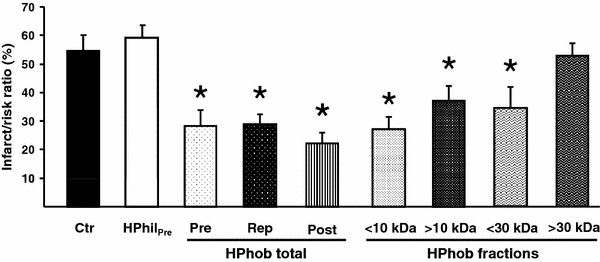

Cardioprotective potency of fractionated IPC effluent

To further characterize potential humoral factor(s), the coronary IPC effluent was separated into hydrophilic and hydrophobic fractions, and the hydrophobic fraction was further divided based on particulate size (> or <10 or 30 kDa). The total hydrophobic effluent fraction administered for 10 min before hearts were subjected to 30 min of regional ischemia (HPhobPre) resulted in a significantly reduced infarct size as compared to hydrophilic fraction-treated hearts and controls (HPhilPre: 59 ± 4%, Ctr: 54 ± 5% vs. HPhobPre: 28 ± 5%, P < 0.05; Fig. 6). Furthermore, administration of the total hydrophobic effluent fraction at ischemic reperfusion also resulted in significantly reduced infarct size as compared to controls (HPhobRep: 29 ± 3%, HPhobPost: 22 ± 4% vs. Ctr: 54 ± 5%, P < 0.05; Fig. 6). We further fractionated the hydrophobic IPC effluent into four fractions with particulate size > or <10 or 30 kDa. All fractions below 30 kDa afforded cardioprotection as compared to control hearts (HPhobPre < 10: 27 ± 4%, HPhobPre > 10: 37 ± 5%, HPhobRep < 30: 36 ± 6% vs. Ctr: 54 ± 5%, P < 0.05; Fig. 6). However, the cytoprotective mediator in the IPC effluent appears to be of a size less than 30 kDa as the group with particulate fraction above this size failed to offer any cardioprotection (HPhobRep > 30: 52 ± 4% vs. Ctr: 54 ± 5%, ns).

Fig. 6.

The effect of fractionating the IPC effluent based on charge and size with regard to myocardial infarct size. Pre- or post-ischemic administration of the total hydrophobic fraction (HPhobPre, HPhobRep and HPhobPost) and the fractions containing proteins < or >10 kDa (HPhobPre < 10 and HPhobPre > 10) and <30 kDa (HPhobRep < 30) significantly reduced infarct size in non-preconditioned recipient hearts as compared to hydrophilic effluent (HPhil) and control (Ctr) hearts. The hydrophobic fraction containing proteins >30 kDa (HPhobRep < 30) did not offer any cytoprotection. HPhil effluent not bound to C18 column; HPhob effluent eluted from C18 column; total entire hydrophobic fraction; < or >10/30 kDa total hydrophobic fraction further separated by a size exclusion column. Bars represent mean ± SEM. N ≥ 5 in each group. *P < 0.05 versus Ctr

Discussion

To summarize, our data demonstrate that collected coronary IPC effluent contains humoral factor(s) of a hydrophobic character < 30 kDa in size that offers strong cytoprotective properties, significantly reducing infarct size when administered at early ischemic reperfusion in recipient rat hearts, either given as a reperfusion therapy or as pharmacological mimetic of ischemic postconditioning (remote IPost). Moreover, these data suggest that this cardioprotection is partly mediated via PI3K/Akt-dependent cell-survival signaling at ischemic reperfusion.

Our results are in agreement with experiments performed by Serejo et al. [28] and Dickson et al. [5] in the ex vivo rat and rabbit heart, respectively. These studies demonstrate that coronary effluent from donor hearts subjected to IPC confers cardioprotection in isolated buffer-perfused ex vivo recipient hearts administered prior to index ischemia. However, coronary reperfusion is the only means of limiting infarct size, provided that it occurs early after coronary occlusion, but may paradoxically directly result in tissue injury (lethal reperfusion injury). In order to explore if collected IPC coronary effluent could reduce lethal reperfusion-induced injury, we administered IPC effluent for 10 min at immediate reperfusion. Our results confirm that IPC effluent limits reperfusion-induced injury by proving able to offer cytoprotection similar to pre-ischemic treatment even when administered as reperfusion therapy (Fig. 2). In order to further evaluate the temporal requirements of the IPC effluent, it was administered as a postconditioning stimulant at early reperfusion (experimental protocol, Fig. 1), drastically reducing the total treatment time and volume. Nevertheless, exposing the recipient hearts to ~85% less effluent over a shorter time period still offered substantial cardioprotection in un-preconditioned hearts, also validating the phenomena of remote postconditioning (RIPost).

The study by Serejo et al. [28] indicated that the protective effect afforded by IPC effluent disappeared when heated or left in RT for 24 h, while addition of protease inhibitors prevented this time-dependent break down and effluent purification by reverse phase chromatography suggested that the cardioprotective factor(s) could be of a hydrophobic “protein nature”. Our results confirm these findings as administration of total isolated hydrophobic fraction prior to index ischemia or at reperfusion, as reperfusion therapy or RIPost treatment, reduced infarct size by 35–40% compared to control and hydrophilic fraction-treated group. Further fractionation of the total hydrophobic effluent into low and high molecular weight fractions, with either a 10 or 30 kDa cut-off, revealed that both 10 kDa fractions, but only the low weight fractions of 30 kDa cut-off, retained the ability to offer cardioprotection comparable to the cytoprotection afforded by the total hydrophobic faction (Fig. 6). Thus, we propose that the factor(s) responsible for the protective capabilities have a size either under or close to 30 kDa (depending on the efficiency of the columns used). Since both 10 kDa fractions were protective, this suggests that the effluent either contains more than one factor with protective capabilities, with at least one of them being of a smaller and one of a larger size than the size of the filter used (10 kDa), or that the factor(s) is of a size close to the columns 10 kDa cut-off limit, causing it to be present in both fractions.

Adenosine, opioids and bradykinin are endogenously released triggers of IPC that work in parallel, binding to cell surface receptors initiating the IPC response (reviewed in [7]). Being released into the circulation, the triggers have also the potential to protect cells not directly subjected to IPC [26], which could at least in part explain the phenomenon of remote preconditioning (RIPC), in which preconditioning of non-cardiac tissue such as skeletal muscle [24] and kidney [33] will protect the heart from subsequent ischemic events. The mechanisms behind RIPC are believed to be shared with IPC and IPost [10], and include the release of cardioprotective autocoids such as adenosine [3], nitric oxide [29], activation of innate immunity [36], activation of RISK signaling [9], and the inhibition of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) [13]. Recently, RIPC was also shown to work via unidentified neurological or humoral pathways [19]. However, emerging evidences suggest that adenosine and other small molecules involved in IPC protection might not be responsible for the protective capabilities of the IPC effluent. Dickson et al. [5] compared adenosine levels in coronary effluent from preconditioned and control hearts, and found no difference in mean adenosine concentrations. They also failed to find a relationship between adenosine concentration and infarct size [5]. Using a 3.5 kDa dialysis membrane, Serejo et al. [28] excluded low molecular weight molecules (adenosine 267.24 Da, opioids 500–800 Da, and bradykinin 1,060.22 Da) without losing the protective effect. Our study confirms that the IPC effluent must contain cytoprotective substances larger than 3.5 kDa as the hydrophobic fraction > 10 kDa resulted in protection similar to the total hydrophobic and low molecular fractions. Furthermore, our results also suggest that smaller size molecules might not be necessary in evoking the cytoprotective response, since the hydrophobic fraction > 10 kDa offered a reduction in infarct size comparable to the total hydrophobic fraction.

Activation of RISK signaling during reperfusion unites IPC, IPost and other agents that facilitate cardioprotection when offered either prior to ischemia or at reperfusion [10], and prolonging RISK activation by phosphatase inhibition during reperfusion also offers cytoprotection [8]. Of note, studies have questioned the importance of RISK in cardioprotection by IPost [27, 30] and in gentle reperfusion [23]. However, Akt is an important mediator of RISK signaling, and inhibition of the up-stream PI3-kinase with either Wortmannin or LY 294002 reduced Akt phosphorylation and abolished IPC-mediated protection [21, 32]. We have previously demonstrated that pharmacologically induced phosphorylation of PI3K/Akt in the first few min of reperfusion after a sustained ischemic insult is cardioprotective [14]. In the present study, we demonstrate that activation of Akt-dependent pro-survival signaling at reperfusion is required for the pre-ischemic IPC effluent-induced protection. Inhibiting PI3K/Akt-signaling at the onset of reperfusion in hearts pretreated with IPC effluent completely abolished the protection (Fig. 5). This PI3K/Akt-dependent cytoprotection offered by pre-ischemic effluent treatment was paralleled by a significantly increase in Akt phosphorylation both pre- and post-ischemia (Fig. 4). Administration of the effluent as a reperfusion therapy also resulted in increased Akt-phosphorylation, and the protection was abolished by PI3K/Akt-signaling inhibition. Taken together, our data indicate that factor(s) retaining cytoprotective properties in IPC effluent are conveying cardioprotection via activation of Akt-dependent signaling that can be modulated at reperfusion after a lethal ischemic insult. We could not prove involvement of the SAFE pathway [18], which is thought to interact with RISK signaling at reperfusion, as the IPC effluent failed to modulate the status of STAT3 phosphorylation (results not shown). In addition to activation of Akt, the IPC effluent has previously been shown to lose its protective effect when co-administered with the PKC inhibitor chelerythrine [28]. PKC has been implicated as an early mediator of preconditioning [31], and may contribute to Akt phosphorylation at the time of reperfusion [25], and thereby inducing cardioprotection which may include inhibition of mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening [9].

In conclusion, effluent collected during ischemic preconditioning of ex vivo rat hearts protects untreated recipient hearts from reperfusion-induced injury via a PI3K/Akt-dependent pathway that can be modulated at ischemic reperfusion. The IPC effluent has the ability to offer cytoprotection when administered as a stimulus of remote postconditioning (RIPost) or as a reperfusion therapy. The molecules responsible for the effluents protective abilities are below or close to 30 kDa and at least one of them are larger than 10 kDa. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that the effluent or its mediator(s) has a strong cardioprotective action implying a great potential as adjunct reperfusion therapy for patients with AMI.

Acknowledgments

AKJ was supported with grants from the Norwegian Council on Cardiovascular Diseases, Bergen Medical Research Foundation, The Meltzer Foundation, Bergen Heart Foundation. LB is funded by the Norwegian Council on Cardiovascular Diseases. EH is funded by the Research Council of Norway.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Anderson KE, Coadwell J, Stephens LR, Hawkins PT. Translocation of PDK-1 to the plasma membrane is important in allowing PDK-1 to activate protein kinase B. Curr Biol. 1998;8(12):684–691. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70274-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braunwald E, Kloner RA. Myocardial reperfusion: a double-edged sword? J Clin Invest. 1985;76(5):1713–1719. doi: 10.1172/JCI112160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen MV, Downey JM. Adenosine: trigger and mediator of cardioprotection. Basic Res Cardiol. 2008;103(3):203–215. doi: 10.1007/s00395-007-0687-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson SM, Hausenloy D, Duchen, Yellon DM. Signalling via the reperfusion injury signalling kinase (risk) pathway links closure of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore to cardioprotection. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38(3):414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickson EW, Lorbar M, Porcaro WA, Fenton RA, Reinhardt CP, Gysembergh A, Przyklenk K. Rabbit heart can be “preconditioned” via transfer of coronary effluent. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(6 Pt 2):H2451–H2457. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.6.H2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickson EW, Reinhardt CP, Renzi FP, Becker RC, Porcaro WA, Heard SO. Ischemic preconditioning may be transferable via whole blood transfusion: preliminary evidence. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 1999;8(2):123–129. doi: 10.1023/A:1008911101951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Downey JM, Davis AM, Cohen MV. Signaling pathways in ischemic preconditioning. Heart Fail Rev. 2007;12(3–4):181–188. doi: 10.1007/s10741-007-9025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan WJ, van Vuuren D, Genade S, Lochner A. Kinases and phosphatases in ischaemic preconditioning: a re-evaluation. Basic Res Cardiol. 2010;105(4):495–511. doi: 10.1007/s00395-010-0086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hausenloy DJ, Tsang A, Yellon DM. The reperfusion injury salvage kinase pathway: a common target for both ischemic preconditioning and postconditioning. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15(2):69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. Preconditioning and postconditioning: united at reperfusion. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;116(2):173–191. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. Remote ischaemic preconditioning: underlying mechanisms and clinical application. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79(3):377–386. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heusch G, Boengler K, Schulz R. Cardioprotection: nitric oxide, protein kinases, and mitochondria. Circulation. 2008;118(19):1915–1919. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.805242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heusch G, Boengler K, Schulz R. Inhibition of mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening: the holy grail of cardioprotection. Basic Res Cardiol. 2010;105(2):151–154. doi: 10.1007/s00395-009-0080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonassen AK, Sack MN, Mjos OD, Yellon DM. Myocardial protection by insulin at reperfusion requires early administration and is mediated via Akt and p70s6 kinase cell-survival signaling. Circ Res. 2001;89(12):1191–1198. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.101385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerendi F, Kin H, Halkos ME, Jiang R, Zatta AJ, Zhao ZQ, Guyton RA, Vinten-Johansen J. Remote postconditioning. Brief renal ischemia and reperfusion applied before coronary artery reperfusion reduces myocardial infarct size via endogenous activation of adenosine receptors. Basic Res Cardiol. 2005;100(5):404–412. doi: 10.1007/s00395-005-0539-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozikowski AP, Sun H, Brognard J, Dennis PA. Novel PI analogues selectively block activation of the pro-survival serine/threonine kinase Akt. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(5):1144–1145. doi: 10.1021/ja0285159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang SC, Elsasser A, Scheler C, Vetter S, Tiefenbacher CP, Kubler W, Katus HA, Vogt AM. Myocardial preconditioning and remote renal preconditioning–identifying a protective factor using proteomic methods? Basic Res Cardiol. 2006;101(2):149–158. doi: 10.1007/s00395-005-0565-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lecour S, Suleman N, Deuchar GA, Somers S, Lacerda L, Huisamen B, Opie LH. Pharmacological preconditioning with tumor necrosis factor-alpha activates signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 at reperfusion without involving classic prosurvival kinases (Akt and extracellular signal-regulated kinase) Circulation. 2005;112(25):3911–3918. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.581058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim SY, Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ (2010) The neural and humoral pathways in remote limb ischemic preconditioning. Basic Res Cardiol. doi:10.1007/s00395-010-0099-y [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Miura T, Miki T. Limitation of myocardial infarct size in the clinical setting: current status and challenges in translating animal experiments into clinical therapy. Basic Res Cardiol. 2008;103(6):501–513. doi: 10.1007/s00395-008-0743-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mocanu MM, Bell RM, Yellon DM. PI3 kinase and not p42/p44 appears to be implicated in the protection conferred by ischemic preconditioning. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34(6):661–668. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74(5):1124–1136. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Musiolik J, van Caster P, Skyschally A, Boengler K, Gres P, Schulz R, Heusch G. Reduction of infarct size by gentle reperfusion without activation of reperfusion injury salvage kinases in pigs. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;85(1):110–117. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oxman T, Arad M, Klein R, Avazov N, Rabinowitz B. Limb ischemia preconditions the heart against reperfusion tachyarrhythmia. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(4 Pt 2):H1707–H1712. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.4.H1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ping P, Zhang J, Cao X, Li RC, Kong D, Tang XL, Qiu Y, Manchikalapudi S, Auchampach JA, Black RG, Bolli R. PKC-dependent activation of p44/p42 MAPKs during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion in conscious rabbits. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(5 Pt 2):H1468–H1481. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.5.H1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Przyklenk K, Bauer B, Ovize M, Kloner RA, Whittaker P. Regional ischemic ‘preconditioning’ protects remote virgin myocardium from subsequent sustained coronary occlusion. Circulation. 1993;87(3):893–899. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.3.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz LM, Lagranha CJ. Ischemic postconditioning during reperfusion activates Akt and Erk without protecting against lethal myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in pigs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290(3):H1011–H1018. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00864.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serejo FC, Rodrigues LF, Jr, da Silva Tavares KC, de Carvalho AC, Nascimento JH. Cardioprotective properties of humoral factors released from rat hearts subject to ischemic preconditioning. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;49(4):214–220. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3180325ad9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiva S, Gladwin MT. Nitrite mediates cytoprotection after ischemia/reperfusion by modulating mitochondrial function. Basic Res Cardiol. 2009;104(2):113–119. doi: 10.1007/s00395-009-0009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skyschally A, van Caster P, Boengler K, Gres P, Musiolik J, Schilawa D, Schulz R, Heusch G. Ischemic postconditioning in pigs: no causal role for risk activation. Circ Res. 2009;104(1):15–18. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.186429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Speechly-Dick ME, Mocanu MM, Yellon DM. Protein kinase C. Its role in ischemic preconditioning in the rat. Circ Res. 1994;75(3):586–590. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.3.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stojanovic A, Marjanovic JA, Brovkovych VM, Peng X, Hay N, Skidgel RA, Du X. A phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Akt-nitric oxide-cGMP signaling pathway in stimulating platelet secretion and aggregation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(24):16333–16339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512378200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takaoka A, Nakae I, Mitsunami K, Yabe T, Morikawa S, Inubushi T, Kinoshita M. Renal ischemia/reperfusion remotely improves myocardial energy metabolism during myocardial ischemia via adenosine receptors in rabbits: effects of remote preconditioning. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(2):556–564. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(98)00559-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tong H, Chen W, Steenbergen C, Murphy E. Ischemic preconditioning activates phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase upstream of protein kinase c. Circ Res. 2000;87(4):309–315. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.4.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsang A, Hausenloy DJ, Mocanu MM, Yellon DM. Postconditioning: a form of “modified reperfusion” protects the myocardium by activating the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt pathway. Circ Res. 2004;95(3):230–232. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000138303.76488.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valeur HS, Valen G. Innate immunity and myocardial adaptation to ischemia. Basic Res Cardiol. 2009;104(1):22–32. doi: 10.1007/s00395-008-0756-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang XM, Liu Y, Tandon N, Kambayashi J, Downey JM, Cohen MV. Attenuation of infarction in cynomolgus monkeys: preconditioning and postconditioning. Basic Res Cardiol. 2009;105(1):119–128. doi: 10.1007/s00395-009-0050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yellon DM, Downey JM. Preconditioning the myocardium: from cellular physiology to clinical cardiology. Physiol Rev. 2003;83(4):1113–1151. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00009.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Myocardial reperfusion injury. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(11):1121–1135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao ZQ, Corvera JS, Halkos ME, Kerendi F, Wang NP, Guyton RA, Vinten-Johansen J. Inhibition of myocardial injury by ischemic postconditioning during reperfusion: comparison with ischemic preconditioning. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285(2):H579–H588. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01064.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]