Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

KCNQ-encoded voltage-gated potassium channels (Kv7) have recently been identified as important anti-constrictor elements in rodent blood vessels but the role of these channels and the effects of their modulation in human arteries remain unknown. Here, we have assessed KCNQ gene expression and function in human arteries ex vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

Fifty arteries (41 from visceral adipose tissue, 9 mesenteric arteries) were obtained from subjects undergoing elective surgery. Quantitative RT-PCR experiments using primers specific for all known KCNQ genes and immunohistochemsitry were used to show Kv7 channel expression. Wire myography and single cell electrophysiology assessed the function of these channels.

KEY RESULTS

KCNQ4 was expressed in all arteries assessed, with variable contributions from KCNQ1, 3 and 5. KCNQ2 was not detected. Kv7 channel isoform-dependent staining was revealed in the smooth muscle layer. In functional studies, the Kv7 channel blockers, XE991 and linopirdine increased isometric tension and inhibited K+ currents. In contrast, the Kv7.1-specific blocker chromanol 293B did not affect vascular tone. Two Kv7 channel activators, retigabine and acrylamide S-1, relaxed preconstricted arteries, actions reversed by XE991. Kv7 channel activators also suppressed spontaneous contractile activity in seven arteries, reversible by XE991.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

This is the first study to demonstrate not only the presence of KCNQ gene products in human arteries but also their contribution to vascular tone ex vivo.

LINKED ARTICLE

This article is commented on by Mani and Byron, pp. 38–41 of this issue. To view this commentary visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01065.x

Keywords: KCNQ, Kv7, human, vascular smooth muscle, arterial tone

Introduction

The Kv7 channels (Kv7.1–Kv7.5) are a subfamily of voltage-gated potassium channels, encoded by KCNQ genes, and contribute to cell hyperpolarization. Each of the Kv7 channels has a particular distribution, with Kv7.1 expressed predominantly in cardiac myocytes (Sanguinetti et al., 1996) and Kv7.2–Kv7.5 predominantly in the nervous system (Jentsch, 2000) functioning as essential regulators of membrane excitability. Mutations in these genes leading to a reduction of Kv7 channel activity underlie a range of diseases characterized by membrane hyperexcitability such as cardiac arrhythmias, epilepsy and sensorineuronal deafness (Jentsch, 2000; Kharkovets et al., 2000; Wilde and Bezzina, 2005). Recently, KCNQ expression has been shown in various rodent blood vessels (Ohya et al., 2003; Yeung et al., 2007; Mackie and Byron, 2008; Mackie et al., 2008; Greenwood and Ohya, 2009; Joshi et al., 2009; Zhong et al., 2010). In each case KCNQ1 and KCNQ4 expression predominated, although a truncated variant of KCNQ5 was also present (Yeung et al., 2008a).

A functional role for Kv7 channels was inferred from the observation that the broad spectrum Kv7 blockers, XE991 and linopirdine, increased vascular tone in a number of blood vessels including portal vein and aorta as well as mesenteric, pulmonary and cerebral arteries (Yeung and Greenwood, 2005; Joshi et al., 2006; Yeung et al., 2007; Mackie et al., 2008; Zhong et al., 2010). These contractions were abolished by blocking voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCCs) either directly with the L-type voltage-gated calcium channel blocker, nicardipine, or indirectly by the ATP-sensitive K-channel opener, pinacidil, inducing membrane hyperpolarization. Furthermore, this constrictor response was not related to the depolarization of sympathetic nerves and subsequent release of noradrenaline, as XE991 evoked a robust contraction in the presence of prazosin, an α1-adrenoreceptor antagonist. This view was supported by experiments that revealed that retigabine and flupirtine, activators of K+ channels encoded by KCNQ2-5 but not KCNQ1 (Main et al., 2000; Schenzer et al., 2005; Wuttke et al., 2005), relaxed preconstricted arteries (Yeung et al., 2007; 2008b; Mackie et al., 2008; Brueggemann et al., 2009; Joshi et al., 2009).

Despite such accumulating evidence that KCNQ-encoded voltage-gated potassium channels have a significant role in the regulation of vascular reactivity in animal models, the presence and function of the former have hitherto not been described in human vasculature, an important question in light of the development of Kv7 activators as therapeutic targets (Dalby-Brown et al., 2006; Porter et al., 2007) and the possibility of targeting these channels as anti-hypertensive therapies. Therefore, this study has investigated KCNQ expression at RNA and protein levels in human arteries and assessed whether structurally different modulators of these channels affected vascular tone ex vivo.

Methods

For an expanded Materials and Methods section, please see the online Supporting Information. All channel nomenclature follows Alexander et al. (2009).

Study population

This investigation conforms to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee (08/H0803/84) for retrieval of human blood vessels. Informed written consent was obtained from all subjects in the study and there were no exclusion criteria applied. Patient demographics data (age, gender, ethnicity, co-morbidities, surgical procedure, medications and preoperative biochemical blood tests) were also collected. Fifty patients participated in the study, 48 during June 2008 to July 2009 with two further recruited in July 2010. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Visceral adipose tissue arteries n= 39 | Proximal branches of coeliac, superior mesenteric or inferior mesenteric arteries n= 9 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 51.2 ± 2.8 | 61.3 ± 5.9 | N.S. |

| Gender (% male) | 18% (7/39) | 66% (6/9) | 0.007 |

| Co-morbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 26% (10/39) | 78% (7/9) | 0.005 |

| Diabetes | 13% (5/39) | 22% (2/9) | N.S. |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 8% (3/39) | 56% (5/9) | 0.003 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 3% (1/39) | 11% (1/9) | N.S. |

| Obesity (undergoing bariatric surgery) | 44% (17/39) | 22% (2/9) | N.S. |

| Colorectal carcinoma | 0 | 67% (6/9) | <0.001 |

| Anti-hypertensive medications (as % of hypertensive patients) | |||

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 50% (5/10) | 57% (4/7) | N.S. |

| Calcium channel blockers | 50% (5/10) | 29% (2/7) | N.S. |

| Preoperative blood tests | |||

| Serum creatinine (µmol·L−1) | 73.5 ± 2.3 | 78.8 ± 9.4 | N.S. |

| Serum potassium (mmol·L−1) | 4.3 ± 0.04 | 4.5 ± 0.21 | N.S. |

| Average pressure-normalized vessel segment diameter (µm) | 478 ± 50 | 1587 ± 242 | <0.001 |

| Basal tension after normalization (mN) | 3.79 ± 0.13 (n= 111 segments) | 8.83 ± 0.62 (n= 45 segments) | <0.001 |

N.S., not significant.

Tissue collection

Two distinct vessel types were obtained – arteries from visceral adipose tissue from cholecystectomies and bariatric surgery, and proximal mesenteric arteries from gastric and colonic resections. Arteries used in the study were dissected free from any damaged or pathologically altered tissue by the operating surgeon and microdissected in the laboratory within 1 h. Arteries were identified as the muscular vessel running as a pair with thin walled veins (Mulvany and Halpern, 1977).

Endpoint and quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from arteries and reverse transcribed to cDNA. Human brain and heart RNA (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) was used as positive control for mRNA analysis studies. Endpoint PCR and quantitative PCR were performed using primers specific for human KCNQ genes (Table S1). Primers for neuronal and smooth muscle markers were adapted from Harhun et al. (2009). Quantitative analysis of mRNA expression was determined using Brilliant SYBR® Green QPCR Master Mix (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) with the Mx3005P system (Stratagene). All quantitative data were accrued from three different patients, with each reaction performed in duplicate. Relative abundance of each gene of interest was calculated, normalized to the geometric mean of the two housekeeper genes using an Efficiency-corrected Comparative Quantitation method (Pfaffl, 2001).

Immunohistochemistry

Fluorescence immunohistochemistry was performed on 10 µm thick slices of human artery from three different patients. The primary antibodies used were anti-smooth muscle actin (Alomone, Jerusalem, Israel), anti-Kv7.1 (1:50; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA; AB5932), anti-Kv7.3 (1:200; Millipore; AB5483), anti-Kv7.4 (1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, UK; ab65797) and anti-Kv7.5 (1:100; Millipore; AB9792). Secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor® 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and Alexa Fluor 546 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen). Sequential slices that had not been incubated in primary antibody but exposed to the secondary antibody were used as controls as the antibodies used did not have an antigenic peptide. All antibodies have been validated in either Western blot (Knollmann et al., 2007 and Yus-Nájera et al., 2003 for Kv7.1 and Kv7.3 antibodies) and/or non-antigenic serum controlled immunohistochemistry (Jepps et al., 2009 for Kv7.4 and Kv7.5 antibodies).

Isometric tension small wire myography

Artery segments of approximately 2 mm length were mounted on a myograph (Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus, Denmark) on 40 µm tungsten wires in baths containing standard Krebs solution (125 mmol·L−1 NaCl, 4.6 mmol·L−1 KCl, 2.5 mmol·L−1 CaCl2, 25.4 mmol·L−1 NaHCO3, 1 mmol·L−1 Na2HPO4, 0.6 mmol·L−1 MgSO4 and 10 mmol·L−1 glucose), maintained at 37°C and aerated with 95% O2/5% CO2. Arterial segments were normalized to a tension equivalent to that generated at 90% of the diameter of the vessel at 100 mmHg (Mulvany and Halpern, 1977) giving a mean diameter under these conditions of 478 ± 50 µm for the visceral adipose arteries (n= 39 patients) and 1587 ± 242 µm for the proximal mesenteric arteries (n= 9 patients). No attempt was made to check for endothelial integrity.

Single cell isolation and electrophysiology

Segments of human visceral adipose artery were cleaned of adherent connective tissue and were transferred to nominally Ca2+-free physiological salt solution supplemented with protease type X (0.5 mg·mL−1) and collagenase type IA (1.5 mg·mL−1) (both from Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, UK). Tissue was then incubated at 37°C for 30 min followed by a 5 min wash in Ca2+-free salt solution at room temperature (20°C–23°C). Single cells were obtained by gentle agitation with a wide-bore pipette and the suspension was transferred to experimental chambers and kept for 20 min at room temperature to allow adherence of the cells to the glass coverslip forming the bottom of the experimental chamber. Electrical recordings were made using the amphotericin B perforated patch tight-seal whole-cell recording technique in voltage clamp mode. The fire-polished patch pipettes had a free-tip resistance of 4–5 MOhm when filled with pipette solution of the following composition (mmol·L−1): KCl 115; NaCl 6, HEPES 10; pH adjusted to 7.3 with KOH. Before the experiment the pipette solution was supplemented with amphotericin B (200 mg·mL−1). Cells were held at −60 mV and stepped to voltages between −60 and +40 mV. External solution (nominally Ca2+-free physiological salt solution): in mmol·L−1: KCl 6, NaCl 120, MgCl2 1.2, d-glucose 10 and HEPES 10; pH was adjusted to 7.3 with NaOH.

Data analysis

Results were reported as mean ± SEM, unless stated otherwise. The allocation within pairs to Kv7 channel modulators was randomized to reduce the potential effect of intravessel variability. Significance of the difference between groups was assessed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired samples and Mann–Whitney U-test for unmatched samples. Significance of the difference between proportions was assessed using McNemar's test for paired samples and Fisher Exact test for unmatched samples. Significance of relationships between two continuous variables was assessed by Pearson's correlation. P-values <0.05 were considered to be significant. All analyses used spss version 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Materials

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma, UK except for: XE991 (Ascent Scientific, Bristol, UK), retigabine (gift from Dr Schwake, Kiel, Germany) and acrylamide S-1 (NeuroSearch A/S, Ballerup, Denmark).

Results

KCNQ mRNA detected in human arteries

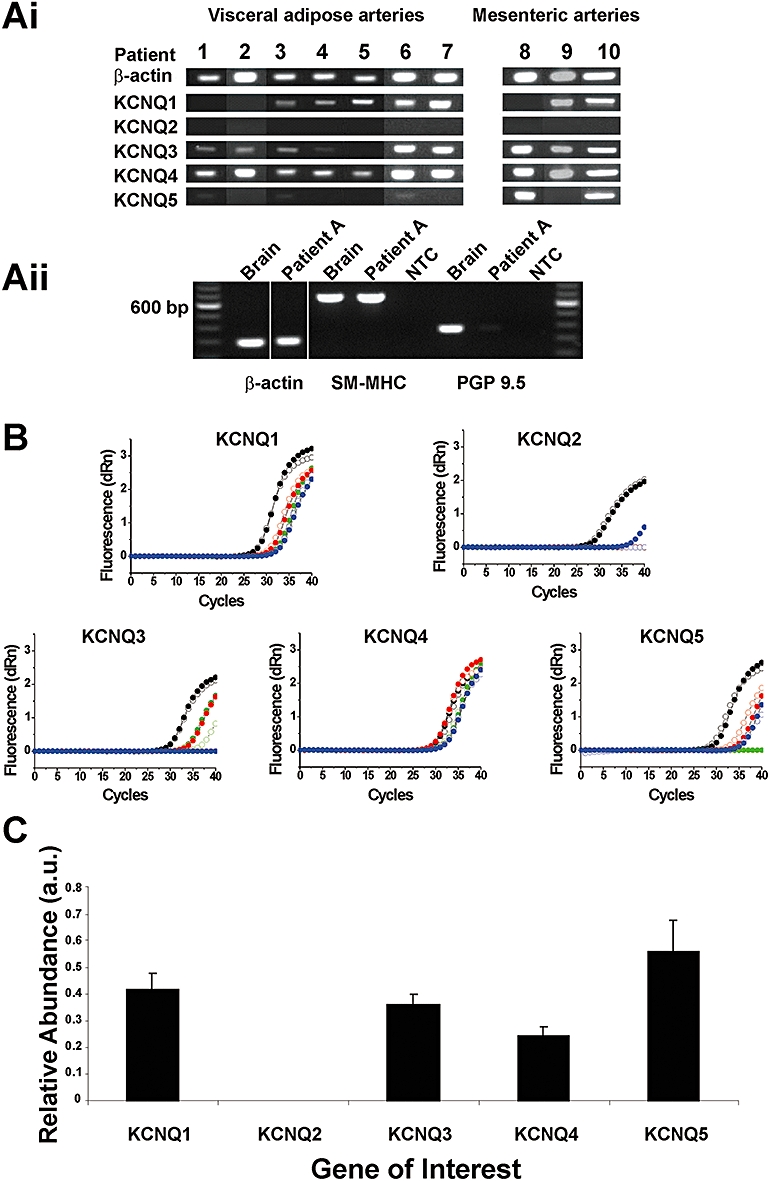

There is presently no information as to whether KCNQ genes are expressed in human arteries. Consequently, endpoint and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (QPCR) were undertaken using RNA isolated from arteries from 10 different patients. Amplicons corresponding to the KCNQ4 gene were amplified in all 10 (seven visceral adipose tissue, three mesenteric) samples (Figure 1A). In order of decreasing frequency, apparent message for KCNQ3, KCNQ1 and KCNQ5 was also detected, whereas KCNQ2 expression was not found in this cohort, under these experimental conditions (Figure 1A). All amplification products were sequenced and shown to be homologous with known human KCNQ sequences (data not shown). Sequence analysis of the KCNQ5 product amplified was shown to be homologous with the truncated splice variant previously identified in murine vasculature by our group (data not shown; Yeung et al., 2008a). Figure 1Aii shows that detection of the neuronal marker PGP-9.5 in mRNA from human arteries was negligible compared with the smooth muscle marker smooth muscle myosin heavy chain suggesting that, in these muscular arteries, nerves contribute little to the KCNQ expression data.

Figure 1.

Expression of KCNQ genes in human arteries. (Ai) Conventional endpoint RT-PCR experiments demonstrating variable expression of KCNQ genes in 10 human arteries, grouped by source of artery. (Aii) Endpoint RT-PCR comparing neuronal and smooth muscle markers in human brain and artery. (B) Amplification plots for KCNQ primers with cDNA from positive controls (heart for KCNQ1 and brain for KCNQ2–5, black open and closed symbols) and arteries from three patients, randomly chosen from samples 1–7 in Ai (red, green and blue open and closed symbols, respectively). (C) Quantitative PCR analysis of relative abundance of KCNQ genes, normalized to mean of β-actin and L19 housekeeper genes. Values were corrected for differences in primer efficiencies. Reactions were performed with three different patients (B–D), randomly chosen from samples 1–7, each in duplicate. Data represent the mean ± SEM.

Of the seven visceral adipose tissue arteries collected, a blinded study of three randomly chosen cDNA samples was used to determine relative abundance of KCNQ genes in human arteries. Quantitative PCR analysis showed that of the five members of the KCNQ gene family, only four were detectable under these assay conditions, namely KCNQ1, 3, 4 and 5. For KCNQ2 no detectable signal after 40 cycles was recorded (No Ct value given) in five of the six duplicates from three patients; of the six duplicates a high Ct value of 37.67 was seen (Figure 1B). Confirmation that this result is not an artefact of primers mis-priming was assessed by considering the amplification plots of each primer set with concentration matched cDNA from positive control samples (human heart for KCNQ1 and human brain for KCNQ2–5 genes) against each patient duplicate (Figure 1B). In each case, each KCNQ gene was amplified in the corresponding control tissue. In addition, no template controls and ‘No RT’ samples were also run alongside each corresponding ‘RT-positive’ sample to confirm all samples were free from contaminating template, primer dimers and DNA and, to ensure that expression levels were not artificially elevated. Normalization of results to the mean values of two housekeeping genes confirmed that under these experimental conditions (see Supporting information), KCNQ1, 3–5 genes were expressed in human arteries at approximately equal levels whereas KCNQ2 was absent (Figure 1C) suggesting that this gene is not expressed in these arteries or the copy number is considerably lower than detectable levels for this assay.

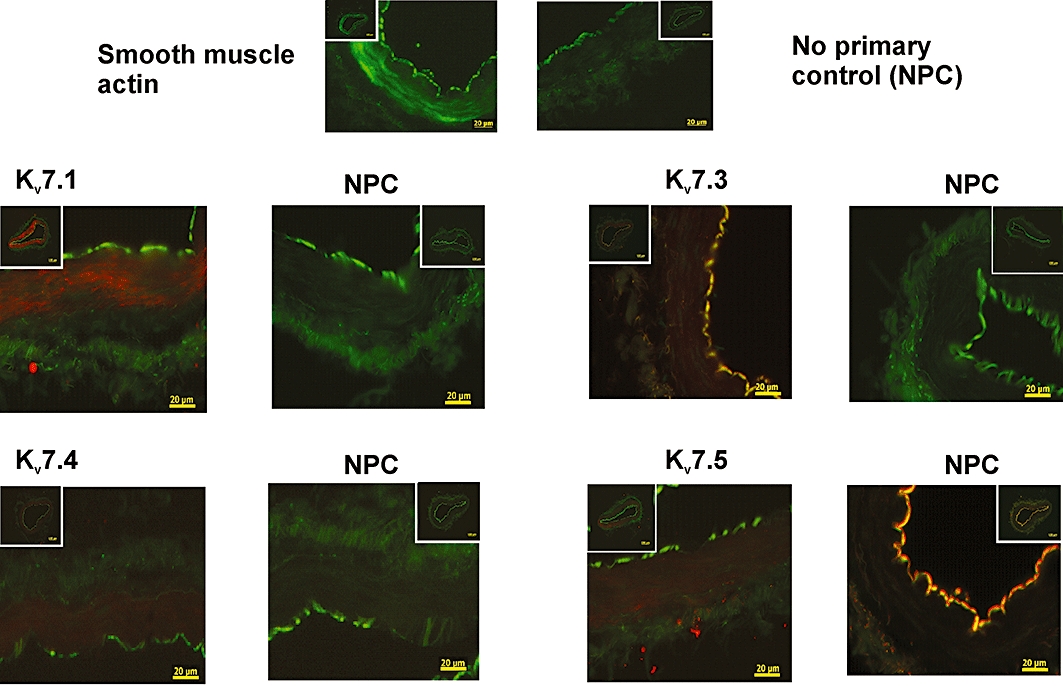

Kv7 channel protein identified in human arteries

As QPCR showed that message for KCNQ1, 3, 4 and 5 were present in human arteries, immunohistochemical experiments were undertaken to determine whether corresponding proteins were detectable in the smooth muscle layer. Figure 2A shows representative images from 10 µm transverse slices of human arteries showing staining for smooth muscle actin, defining the smooth muscle layer, which is demarcated on the luminal side by an auto-fluorescent elastic lamina. Antibodies against different Kv7 channel isoforms revealed that detectable staining for Kv7.1, Kv7.3, Kv7.4 and Kv7.5 proteins was localized to the smooth muscle layer in dissected arteries from visceral adipose tissue (Figure 2). At the ×40 magnification it is possible to distinguish individual myocytes delineated, although it is difficult at this magnification to ascertain cellular location. There is no evidence for any Kv7 channel localization within neuronal tracks in these studies. However, these images show that Kv7 proteins are detectable in the smooth muscle of these muscular arteries similar to previous immunohistochemical studies in mouse colon (Jepps et al., 2009). This is the first observation of Kv7 protein localization to vascular smooth muscle in human arteries.

Figure 2.

Identification of Kv7 channel proteins in human arteries. Representative fluorescence images from sections (10 µm) of visceral adipose arteries, using primary antibodies against smooth muscle actin, Kv7.1, Kv7.3, Kv7.4 and Kv7.5 taken at ×40 magnification. Inserts show same slice at ×10 magnification. Presence of protein identified by the intensity of the red colouring in the case of the Kv7 antibodies and green colouring for actin. NPC, no primary control.

Functional effects of Kv7 channel modulators

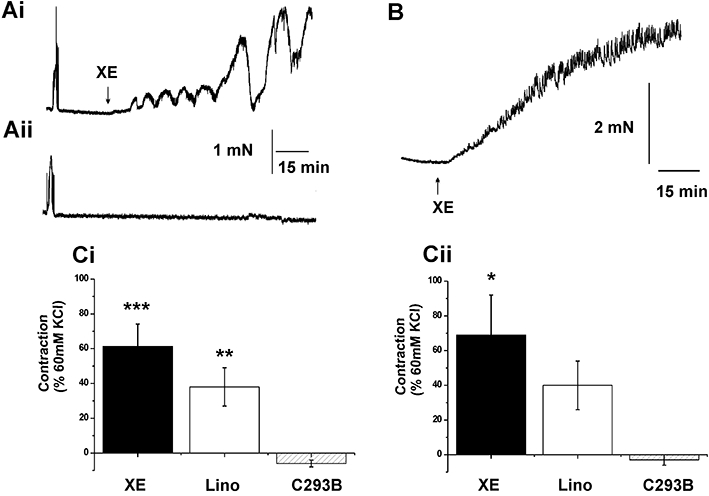

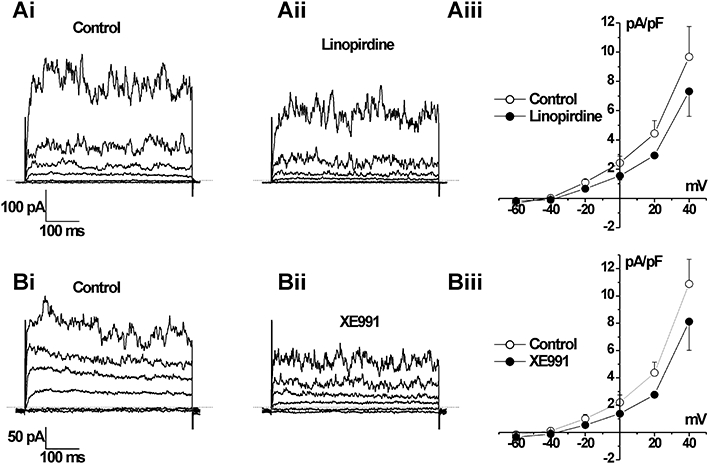

The previous data showed that human arteries expressed KCNQ gene family members. We postulated that Kv7 channels were instrumental in human vascular smooth muscle being able to maintain a negative resting membrane potential, so that calcium entry through VDCCs is lessened. Consequently, blockade of these channels will produce membrane depolarization and contraction – as described in rodent blood vessels (Yeung and Greenwood, 2005; Yeung et al., 2007; Mackie et al., 2008; Joshi et al., 2009), XE991 and linopirdine block all Kv7 channels with IC50 values ∼3 µmol·L−1 (Wang et al., 2000) and at concentrations <100 µmol·L−1 are not known to have effects on any other ion channel. Figure 3 shows that 10 µmol·L−1 XE991 and linopirdine, a concentration selective for KCNQ channels that increases tone in rodent arteries, also contracted human arteries. This contraction was manifested usually as a tonic increase in tension superimposed by phasic contractions although, in some arteries, large amplitude phasic contractions were observed (see Figure 3Ai). For the smaller visceral adipose arteries the mean response to 10 µmol·L−1 XE991 and linopirdine was 1.1 ± 0.24 mN (n= 31) and 0.83 ± 0.41 mN (n= 23) respectively. Application of 10 µmol·L−1 XE991 or 10 µmol·L−1 linopirdine also contracted the larger mesenteric arteries, reflecting their classification as conduit arteries, with mean amplitudes of 7.13 ± 2.20 mN (n= 9) and 10.35 ± 4.24 mN (n= 7) respectively. In line with previous studies on vascular myocytes from rodent blood vessels (e.g. Yeung and Greenwood, 2005; Mackie et al., 2008; Zhong et al., 2010), application of 10 µM linopirdine or 10 µM XE991 inhibited the voltage-dependent K+ current in all cells tested (Figure 4) with a mean inhibition of ∼40% at +20 mV (mean reduction for linopirdine and XE991 was 2.0 ± 0.9 and 2.1 ± 0.7 pA·pF−1, n= 3). In a post hoc analysis, there was no statistical difference in the mean contractile response to 10 µmol·L−1 XE991 or linopirdine when stratifying by internal vessel diameter (see Figure S1), gender, co-morbidities, smoking history or current anti-hypertensive medications. Nor was there a statistical correlation with age, serum K+ or creatinine (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effect of Kv7 channel blockers on arterial tone. (A) Representative traces from paired segments of visceral adipose artery where either 10 µmol·L−1 XE991 (XE; Ai) or equivalent vehicle (Aii) were applied. (B) Representative contraction produced by application of 10 µmol·L−1 XE991 in a human mesenteric artery. The mean data from similar experiments using also linopirdine (Lino) or chromanol 293B (C293B) in (Ci) visceral adipose tissue artery and (Cii) mesenteric artery are shown (visceral adipose tissue artery n= 31, 23 and 19, mesenteric artery n= 9, 7 and 5, respectively). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, significantly different from C293B.

Figure 4.

Effect of Kv7 channel blockers on K+ currents in human visceral artery myocytes. Representative whole cell K+ currents recorded using the perforated patch technique evoked by voltage steps between −80 and +40 mV from −50 mV in the absence (Ai or Bi) or presence of 10 µM linopirdine (Aii) and 10 µM XE991 (Bii). Aiii and Biii show mean current normalized to cell capacitance from three such experiments ± SEM.

In contrast to the effects of XE991 and linopirdine, which block all Kv7 channel isoforms, the selective blocker of Kv7.1 channels, chromanol 293B (10 µmol·L−1, Bett et al., 2006), did not produce a constrictor response in any of the visceral adipose arteries (mean effect was −0.05 ± 0.02 mN, n= 9) or mesenteric conduit arteries (−0.01 ± 0.7 mN, n= 5), similar to its lack of effect in mouse aorta (Yeung et al., 2007). These data suggest that Kv7 channels are functional in human mesenteric and visceral adipose arteries but, similar to murine blood vessels (Yeung et al., 2007), the Kv7.1 isoform, while present, is unlikely to be involved.

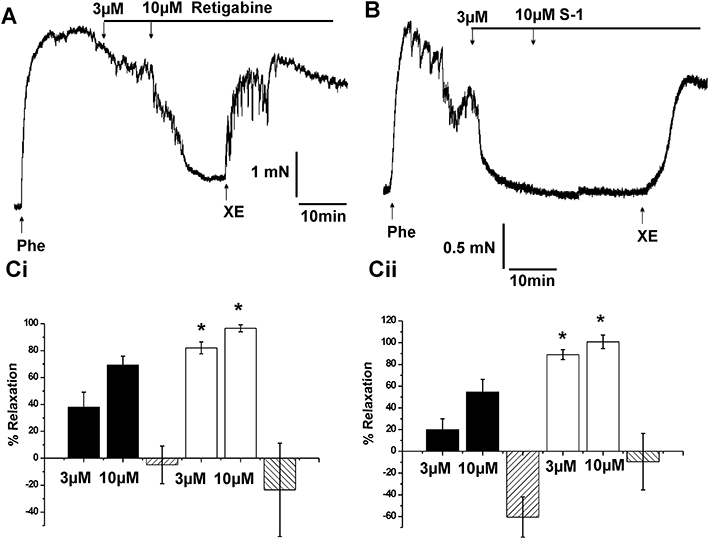

In line with the above hypothesis, augmenting functionally relevant Kv7 channels will drive the resting membrane potential away from the activation threshold for VDCCs so that calcium influx is lessened and the smooth muscle is relaxed. Consequently, Kv7 channel activators such as retigabine (Main et al., 2000; Schenzer et al., 2005; Wuttke et al., 2005) and the structurally dissimilar acrylamide S-1 (Bentzen et al., 2006) should relax pre-contracted human arteries as shown for various murine vessels. Retigabine and acrylamide S-1 (3–10 µmol·L−1) relaxed all pre-contracted visceral adipose and mesenteric arteries dose-dependently, with acrylamide S-1 being more effective than retigabine at both 3 µmol·L−1 and 10 µmol·L−1 (P= 0.02 and 0.03, respectively; Figure 5). In all arterial segments, the relaxation produced by retigabine or acrylamide S-1 was not affected by 1 mM 4-aminopyridine (n= 3) but was reversed completely by the subsequent application of 10 µmol·L−1 XE991 (see Figure 5) or was prevented by application of XE991 before the phenylephrine challenge (n= 3).

Figure 5.

Effect of Kv7 channel activators on vasoconstrictor tone. Representative traces showing the response of paired arterial segments from one visceral adipose tissue artery to (A) retigabine and (B) acrylamide S-1 respectively. 10 µmol·L−1 phenylephrine (Phe) was used to contract the vessels. C shows the summary data of the Kv7 channel activators in (Ci) visceral adipose tissue artery and (Cii) mesenteric arteries; retigabine (black columns, visceral adipose tissue artery, n= 13; mesenteric artery, n= 6), acrylamide S-1 (open columns, visceral adipose tissue artery, n= 15; mesenteric artery, n= 6). Relaxant effects of both channel activators were reversed by the application of 10 µmol·L−1 XE991. Each column represents mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 significantly different from corresponding doses of retigabine.

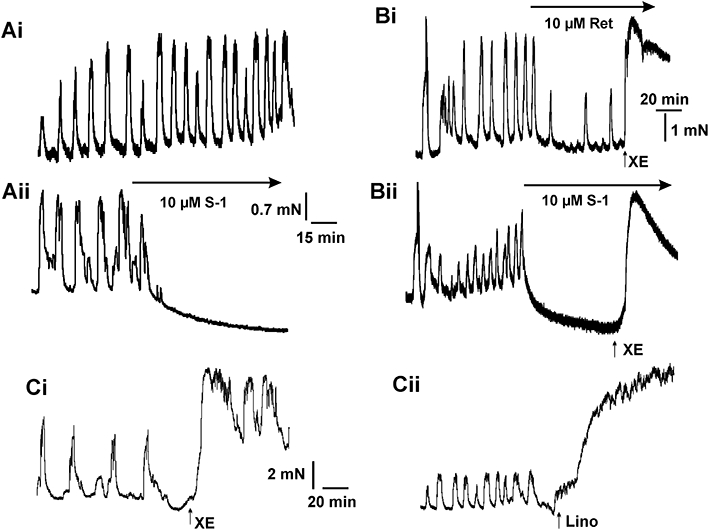

In seven arteries (three visceral adipose tissue arteries, four mesenteric arteries) we observed persistent spontaneous contractile activity in the segments at rest with a mean maximal amplitude equivalent to 154 ± 30% of 60 mmol·L−1 KCl response (see Figure 6), which also coincided with the development of a consistently raised baseline after normalization (myogenic response). In all seven vessels the spontaneous contractions in each segment were either abolished by 10 µmol·L−1 acrylamide S-1 (Figure 6Aii,Bii) or were markedly attenuated by 10 µmol·L−1 retigabine (Figure 6Bi). In each case the effects of the Kv7 channel activators were reversed by 10 µmol·L−1 XE991 to a contractile level higher than the preceding spontaneous contractile activity (increase by amplitude equivalent to 160 ± 20%). Figure 6C also shows that the Kv7 channel blockers XE991 or linopirdine produced a rapid increase in contractility in these segments exhibiting inherent tone. Overall these functional data show that Kv7 channel modulators at concentrations specific for these channels have considerable effects on the contractile state of human vascular smooth muscle in small bore visceral adipose arteries or larger diameter mesenteric arteries suggesting that activation of Kv7 channels represents an effective anti-constrictor mechanism.

Figure 6.

Effect of Kv7 channel activators on spontaneous contractions. A shows examples of contractile activity recorded in contiguous segments of human visceral adipose artery in the (Ai) absence and presence (Aii) of acrylamide S-1. B shows the effect of 10 µmol·L−1 retigabine (Ret; Bi) and 10 µmol·L−1 acrylamide S-1 (S1: Bii) on spontaneous contractions of a human mesenteric artery. Panels in C show the effect of 3 µmol·L−1 XE991 (XE; Ci) and 10 µmol·L−1 linopirdine (Lino; Cii) in segments of the same mesenteric artery shown in B that exhibited spontaneous contractions, representative of three such experiments.

Discussion

The aims of the present study were straightforward: to establish that KCNQ-encoded K+ channels, which we have shown to be functional regulators of rodent blood vessel contractility, were also functionally relevant in human arteries. To that end we demonstrated a range of expression profiles of KCNQ isoforms in human vasculature, with KCNQ4 expression detected in all vessels analysed, variable expression of KCNQ1, 3 and 5, but no KCNQ2 message detected. Quantitative PCR showed that each of the four detectable KCNQ genes (KCNQ1, 3, 4 & 5) had a similar abundance in the human visceral arteries. Similarly, using previously validated antibodies against Kv7.1, Kv7.3, Kv7.4 and Kv7.5 fluorescence immunohistochemistry showed that all four types of Kv7 protein were present in the smooth muscle layer of these arteries. We then established that KCNQ-encoded channels had a functional role, as two broad spectrum Kv7 channel blockers XE991 and linopirdine inhibited voltage-dependent K+ currents and contracted arteries with a range of calibres. Moreover, pre-contracted human arteries were relaxed dose-dependently by two structurally dissimilar compounds, retigabine and acrylamide S-1, which are activators of Kv7.2–7.5, but not Kv7.1 channels (Main et al., 2000; Schenzer et al., 2005; Wuttke et al., 2005; Bentzen et al., 2006). The finding that the relaxations induced by Kv7.2–7.5 activators was reversible by the Kv7 channel blocker, XE991, but not by non-specific K+ channel blockers such as 4-aminopyridine, provides further evidence that the vasoactive actions were due to modulations of Kv7 channels. Interestingly, acrylamide S-1 was a more effective relaxant than retigabine and this agent has a preferential effect on Kv7.4 channels (Bentzen et al., 2006), suggesting that KCNQ4-encoded channels may be more important regulators of vascular reactivity. In contrast, to the functional effects of the agents described above, chromanol 293B, which blocks Kv7.1-containing K+ channels had no effect on human arterial tone although the Kv7.1 protein was detected in the arteries. Kv7.1 proteins only form homotetramers unlike the other Kv7 isoforms, so these observations, which are consistent with previous studies in murine arteries (Yeung et al., 2007), suggest that Kv7.1 has no function in vascular myocytes. Future studies will attempt to address this issue.

The combined pharmacological data suggest that Kv7 channels are regulators of vascular reactivity in both human conduit and resistance arteries but those encoded by KCNQ1 are unlikely to have a simple role in defining membrane potential. These data therefore establish the Kv7.3, Kv7.4 or Kv7.5 channels as important regulators of vascular reactivity and therefore represent putative anti-hypertensive targets. A logical corollary to the findings of the present study is that vascular effects may be associated with Kv7 channel activators, which are under development for other disorders, such as neuropathic pain or epilepsy. Retigabine has progressed to clinical trials (Phase III) as a potential anti-epileptic medication (Blackburn-Munro et al., 2005; Dalby-Brown et al., 2006) and while there has been no formal report of blood pressure in these trials, a recent dose-ranging trial for partial-onset seizures reported significantly increased incidence of dizziness, compared with the placebo group (Porter et al., 2007). Accepting that there are multiple aetiologies of dizziness as an adverse drug event, this may be an indicator of a hypotensive effect of Kv7 activators in humans. In addition, flupirtine, which also activates Kv7 channels, lowers blood pressure in patients with chronic pain during long-term administration (Herrmann et al., 1987; Hummel et al., 1991) while the Kv7 blocker linopirdine has conversely been suggested to increase arterial pressure and vascular resistance in rat models (Mackie et al., 2008). Taken together, the present data provide the novel view that mutations to KCNQ genes or blockade of their expression products may result in vascular complications such as raised blood pressure or an inappropriate response to vasoconstrictors, while Kv7 channel activators may conversely act as vasorelaxants.

In summary, we have identified a specific family of ion channels in human arteries for which its presence and potential function were previously unknown. This represents the first step in translating the results from animal models into potential human therapies. Two key, clinically relevant, findings arise from this study. First, Kv7 blockers contracted both small diameter arteries within adipose tissue and larger proximal mesenteric arteries from patients, consistent with the observed effects on rodent conduit and resistance arteries. Second, the vasorelaxant properties of Kv7 activators were independent of vessel sizes as well as patient demographics, from young and without co-morbidities, to the elderly with multiple cardiovascular risk factors and co-morbidities, and regardless of ongoing pharmacological management. In vivo studies may provide further insight on the impact of pharmacological agents on these channels on both peripheral vascular resistance as well as heart rate.

In conclusion, this study supports further efforts in exploring the potential of Kv7 channels, and possibly Kv7.4 specifically, as key regulators of vascular tone (see Mackie and Byron, 2008). Moreover, the present study suggests that vascular side effects need to be considered in the therapeutic development of Kv7 modulators for diseases such as epilepsy, neuropathic pain or anxiety (see Blackburn-Munro et al., 2005; Dalby-Brown et al., 2006).

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof Robin Shattock for the use of Mx3005P machine purchased on an equipment grant from the Dormeaur Foundation, Dr Ken Laing for QPCR advice and Kinga Szewczyk and Ray F. Moss of the Image Resource Facility at SGUL for their support with the immunological experiments. This work was supported by British Heart Foundation grants to IAG [PG/06/057/20864 and PG/07/127/24235]. TAJ is a BBSRC funded student [BB/G016321/1] with support from NeuroSearch A/S. FLN was funded by a National Institute for Health Research Academic Clinical Fellowship. MIH is a British Heart Foundation Intermediate Basic Science Research Fellow (FS/06/077).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- QPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- retigabine

N-[2-amino-4-[(4-fluorophenyl)methylamino]phenyl]carbamate

- S-1

N-[(1S)-1-(3-morpholinophenyl)ethyl]-3-phenyl-prop-2-enamide

- VDCC

voltage-dependent calcium channel

- XE991, 10

10-bis(4-pyridinyl-methyl)-9(10H)-anthracenone

Conflicts of interest

None.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1 Relationship of functional response to vessel diameter. Scatterplot of pressure-normalized internal vessel diameter and response to 10 μmol·L−1 XE991 or linopirdine on a log scale. Visceral adipose arteries (n = 54) in closed circles; mesenteric arteries (n = 16) in open circles.

Table S1 PCR primer pairs. Primers used for QPCR were a kind gift from Dr S. Ohya, Nagoya City University

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to receptors and channels (GRAC), 4th edn. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(Suppl. 1):S1–S254. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentzen BH, Schmitt N, Calloe K, Dalby Brown W, Grunnet M, Olesen SP. The acrylamide (S)-1 differentially affects Kv7 (KCNQ) potassium channels. Neuropharmacology. 2006;51:1068–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bett GC, Morales MJ, Beahm DL, Duffey ME, Rasmusson RL. Ancillary subunits and stimulation frequency determine the potency of chromanol 293B block of the KCNQ1 potassium channel. J Physiol. 2006;576:755–767. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.116012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn-Munro G, Dalby-Brown W, Mirza NR, Mikkelsen JD, Blackburn-Munro RE. Retigabine: chemical synthesis to clinical application. CNS Drug Rev. 2005;11:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2005.tb00033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brueggemann LI, Mackie AR, Mani BK, Cribbs LL, Byron KL. Differential effects of selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors on vascular smooth muscle ion channels may account for differences in cardiovascular risk profiles. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76:1053–1061. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.057844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalby-Brown W, Hansen HH, Korsgaard MPG, Mirza N, Olesen SP. Kv7 channels: functions, pharmacology and channel modulators. Curr Top Med Chem. 2006;6:999–1023. doi: 10.2174/156802606777323728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood IA, Ohya S. New tricks for old dogs: KCNQ expression and function in smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:1196–1203. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harhun MI, Szewczyk K, Laux H, Prestwich SA, Gordienko DV, Moss RF, et al. Interstitial cells from rat middle cerebral artery belong to smooth muscle cell type. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:4532–4539. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00567.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann WM, Kern U, Aigner M. On the adverse reactions and efficacy of long-term treatment with flupirtine: preliminary results of an ongoing twelve-month study with 200 patients suffering from chronic pain states in arthrosis or arthritis. Postgrad Med J. 1987;63:87–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T, Friedmann T, Pauli E, Niebch G, Borbe HO, Kobal G. Dose-related analgesic effects of flupirtine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;32:69–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb05615.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch TJ. Neuronal KCNQ potassium channels: physiology and role in disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2000;1:21–30. doi: 10.1038/35036198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepps TA, Greenwood IA, Moffatt JD, Sanders KM, Ohya S. Molecular and functional characterization of Kv7 K+ channel in murine gastrointestinal smooth muscles. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G107–G115. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00057.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi S, Balan P, Gurney AM. Pulmonary vasoconstrictor action of KCNQ potassium channel blockers. Respir Res. 2006;7:31. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi S, Sedivy V, Hodyc D, Herget J, Gurney AM. KCNQ modulators reveal a key role for KCNQ potassium channels in regulating the tone of rat pulmonary artery smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:368–376. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharkovets T, Hardelin JP, Safieddine S, Schweizer M, El-Amraoui A, Petit C, et al. KCNQ4, a K+ channel mutated in a form of dominant deafness, is expressed in the inner ear and the central auditory pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4333–4338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knollmann BC, Sirenko S, Rong Q, Katchman AN, Casimiro M, Pfeifer K, et al. Kcnq1 contributes to an adrenergic-sensitive steady-state K+ current in mouse heart. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;360:212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie AR, Byron KL. Cardiovascular KCNQ (Kv7) potassium channels: physiological regulators and new targets for therapeutic intervention. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1171–1179. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.049825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie AR, Brueggemann LI, Henderson KK, Shiels AJ, Cribbs LL, Scrogin KE, et al. Vascular KCNQ potassium channels as novel targets for the control of mesenteric artery constriction by vasopressin, based on studies in single cells, pressurized arteries, and in vivo measurements of mesenteric vascular resistance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;325:475–483. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.135764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main MJ, Cryan JE, Dupere JR, Cox B, Clare JJ, Burbidge SA. Modulation of KCNQ2/3 potassium channels by the novel anticonvulsant retigabine. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:253–262. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvany MJ, Halpern W. Contractile properties of small arterial resistance vessels in spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive rats. Circ Res. 1977;41:19–26. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohya S, Sergeant G, Greenwood IA, Horowitz B. Molecular variants of KCNQ channels expressed in murine portal vein myocytes: a role in delayed rectifier current. Circ Res. 2003;92:1016–1023. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000070880.20955.F4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2002–2007. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter RJ, Partiot A, Sachdeo R, Nohria V, Alves WM. Randomized, multicenter, dose-ranging trial of retigabine for partial-onset seizures. Neurology. 2007;68:1197–1204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259034.45049.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Curran ME, Zou A, Shen J, Spector PS, Atkinson DL, et al. Coassembly of K(V)LQT1 and minK (IsK) proteins to form cardiac I(Ks) potassium channel. Nature. 1996;384:80–83. doi: 10.1038/384080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenzer A, Friedrich T, Pusch M, Saftig P, Jentsch TJ, Grotzinger J, et al. Molecular determinants of KCNQ (Kv7) K+ channel sensitivity to the anticonvulsant retigabine. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5051–5060. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0128-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HS, Brown BS, McKinnon D, Cohen IR. Molecular basis for differential sensitivity of KCNQ and IKs channels to the cognitive enhancer XE991. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:1218–1223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde AAM, Bezzina CR. Genetics of cardiac arrhythmias. Heart. 2005;91:1352–1358. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.046334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuttke TV, Seebohm G, Bail S, Maljevic S, Lerche H. The new anticonvulsant retigabine favors voltage-dependent opening of the Kv7.2 (KCNQ2) channel by binding to its activation gate. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:1009–1017. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.010793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung SY, Greenwood IA. Electrophysiological and functional effects of the KCNQ channel blocker XE991 on murine portal vein smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146:585–595. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung SYM, Pucovský V, Moffatt JD, Saldanha L, Schwake M, Ohya S, et al. Molecular expression and pharmacological identification of a role for Kv7 channels in murine vascular reactivity. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151:758–770. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung SYM, Lange W, Schwake M, Greenwood IA. Expression profile and characterization of a truncated KCNQ5 splice variant. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008a;371:741–746. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung SYM, Schwake M, Pucovský V, Greenwood IA. Bimodal effects of the Kv7 channel activator retigabine on vascular K+ currents. Br J Pharmacol. 2008b;155:62–72. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yus-Nájera E, Muñoz A, Salvador N, Jensen BS, Rasmussen HB, Defelipe J, et al. Localization of KCNQ5 in the normal and epileptic human temporal neocortex and hippocampal formation. Neuroscience. 2003;120:353–364. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong XZ, Harhun MI, Olesen SP, Ohya S, Moffatt JD, Cole WC, et al. Participation of KCNQ (Kv7) potassium channels in myogenic control of cerebral arterial diameter. J Physiol. 2010;588:3277–3293. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.192823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.