Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) and many other pathogens exploit the IL-10 pathway, as part of their infectious cycle, either through their own encoded IL-10 (hcmvIL-10 for HCMV) or manipulation of the cellular IL-10 signaling cascade. Based on the in vitro demonstrations of its pleiotropic and cell type-dependent modulatory nature, hcmvIL-10 could profoundly attenuate host immunity, facilitating the establishment and maintenance of a persistent infection in an immune-competent host. To investigate the impact of extrinsic IL-10 on the induction and maintenance of antiviral immune responses in vivo, rhesus macaques were inoculated with variants of rhesus cytomegalovirus (RhCMV) either expressing or lacking the RhCMV ortholog of hcmvIL-10 (rhcmvIL-10). The results show that rhcmvIL-10 alters the earliest host responses to viral antigens by dampening the magnitude and specificity of innate effector cells to primary RhCMV infection. In addition, there is a commensurate reduction in the quality and quantity of early and long-term, RhCMV-specific adaptive immune responses. These findings provide a mechanistic basis of how early interactions between a newly infected host and HCMV could shape the long-term virus–host balance, which may facilitate the development of new prevention and intervention strategies for HCMV.

Keywords: immune evasion, monkey model

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) establishes a lifelong persistence in immune-competent hosts in the presence of antiviral immune responses that effectively limit viral pathogenesis. The general absence of HCMV disease imposes an extraordinarily large immunological burden on its infected hosts because almost 10% of memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are specific to HCMV antigens (1). The ability to establish and maintain a persistent infection in the presence of such antiviral immunity requires a commensurate dedication of the HCMV coding capacity to immune evasive/modulating proteins that alter cellular activation, signaling, trafficking, and apoptosis.

Up to 60% of the HCMV ORFs can be deleted without affecting viral replication in cultured fibroblasts (2). A sizeable number of these HCMV proteins subvert the immune surveillance of the hosts (3), including those that (i) disrupt natural killer (NK) cell and antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell functions, (ii) are high affinity receptors for β-chemokines and the B and T lymphocyte attenuator, (iii) modulate the cell cycle, and (iv) stimulate innate effector cell trafficking and/or alter the functionality of multiple immune cell types. One example of this latter group is the viral interleukin-10 ortholog (vIL-10) of cellular IL-10 (cIL-10) encoded by the UL111A ORF in primate CMV, including HCMV, rhesus CMV (RhCMV), African green monkey CMV, and baboon CMV (4). The sequence of HCMV-encoded vIL-10 (hcmvIL-10) is highly divergent from cIL-10 (5), yet in vitro studies have demonstrated that hcmvIL-10 binds to the ligand-binding subunit of cellular IL-10 receptor (IL-10R1) with binding affinity comparable to that of cIL-10 (6). cIL-10 is a well-characterized cytokine that suppresses cell-mediated immune responses while enhancing humoral immune responses (7). Despite the considerable genetic drift between viral and host IL-10 proteins, the functionality of hcmvIL-10 is exceedingly conserved with cIL-10 in multiple immune effector cells (8–13). With pleiotropic and cell type-dependent modulatory properties in vitro, expression of hcmvIL-10 could influence virus–host interactions, and contribute to the establishment and/or maintenance of persistence in an immune-competent host.

RhCMV infection in rhesus macaques strongly recapitulates HCMV infection in both immune-competent individuals and those lacking a functional immune system (14). The combination of RhCMV encoding its own vIL-10 (rhcmvIL-10) and the availability of tools to engineer the RhCMV genome enabled direct comparison of the in vivo phenotype of a rhcmvIL-10-deleted RhCMV with its parental virus. The results of this study show that the absence of rhcmvIL-10 is associated with profound changes in both innate and adaptive immune responses after s.c. inoculation of RhCMV in naïve rhesus monkeys. These included changes in the (i) magnitude and constitution of innate immune cells at the site of experimental inoculation, (ii) influx of dendritic cells (DC) to the draining lymph nodes (LN) and induction of adaptive immune responses, (iii) kinetics of antibody maturation and magnitude of antiviral antibody titers, and (iv) quality and quantity of RhCMV-specific T-cell responses. Together with the recent study demonstrating the critical role of the viral inhibitors of MHC-I antigen presentation during primary and nonprimary RhCMV infection (15), the results of this study highlight the complexity of the multilayered mechanisms of HCMV immune evasion.

Results

Construction and In Vitro Properties of rhcmvIL-10–Deleted Mutant of RhCMV.

Both vIL-10 of HCMV and RhCMV share low sequence homology to their host cellular counterparts (27% and 25%, respectively) (4). The expression kinetics (Fig. S1) of the RhCMV UL111A ORF are very similar to those of its HCMV ortholog (9). This work took advantage of the full-length genome of the 68-1 strain of RhCMV (referred to as WT) engineered into a BAC (16) and the Red/ET mutagenesis system (17). Using homologous recombination, the first two coding exons of the UL111A gene were replaced with a zeocin expression cassette containing a terminal stop codon to yield pRhCMV/BAC-ΔUL111A (Fig. S2A). Deletion of the first two exons eliminated most of the region of rhcmvIL-10 necessary for binding to IL-10R1 (6). Mutated RhCMV BAC plasmids were screened by zeocin resistance and diagnostic PCR (Fig. S2B). PCR amplicons from mutant clones were cloned and sequenced to verify the fidelity of homologous recombination. Comprehensive restriction digestions were performed to confirm that no major alterations were introduced anywhere else within the genome during mutagenesis of the UL111A gene (Fig. S2C; EcoRI data shown).

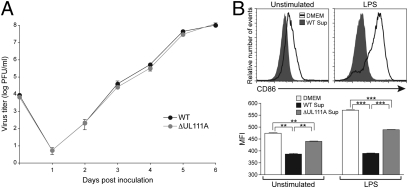

The in vitro growth parameters of RhCMV-ΔUL111A, derived by transfection of fibroblasts with pRhCMV/BAC-ΔUL111A plasmid DNA, were equivalent to those of RhCMV-WT (Fig. 1A) and similar to the lack of in vitro growth defects of HCMV-ΔUL111A compared with its parental HCMV strain AD169 (9). A bioassay was performed to confirm the loss of rhcmvIL-10 coding capacity in RhCMV-ΔUL111A. Rhesus monocyte-derived DC (MoDC) were treated for 24 h with conditioned medium from fibroblasts infected with either WT or ΔUL111A in the presence or absence of LPS. The maturation status of MoDC after incubation was assessed by FACS for surface expression of CD86. Whereas WT supernatant inhibited CD86 expression in unstimulated (i.e., no LPS) and especially LPS-activated MoDC (Fig. 1B Upper), cells incubated with ΔUL111A-conditioned medium expressed a significantly higher level of CD86 than those treated with WT-conditioned medium (Fig. 1B Lower, unstimulated). The difference between WT and ΔUL111A on modulation of CD86 expression was more substantial when cells were activated with LPS (Fig. 1B Lower, LPS). These data also suggested that there were factors in ΔUL111A-conditioned medium, other than rhcmvIL-10, suppressing the maturation of MoDC, because the level of CD86 expression in ΔUL111A-treated group did not reach that of the control group (cells incubated with DMEM). In sum, these results demonstrated that one of the RhCMV proteins inhibiting MoDC maturation, rhcmvIL-10, was deleted from the genome of RhCMV-ΔUL111A.

Fig. 1.

Phenotypic analysis of the rhcmvIL-10 knockout RhCMV in vitro. (A) Multiple-step growth curves of WT and ΔUL111A RhCMV. Telo-RF cultures were infected in triplicate with each virus (MOI = 0.01), and supernatant titers of RhCMV were determined by plaque assays. Data represent mean values ± SD. (B) Functional bioassay for rhcmvIL-10 using rhesus MoDC. Cells were treated with DMEM or conditioned medium in the presence or absence of 5 μg/mL LPS. Surface CD86 was assessed by FACS after 24 h. Data are presented as overlaid histograms (Upper) or mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) (Lower). Data represent mean values ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. Shown are representative data from one of four individual animals.

Viral Parameters of RhCMV-ΔUL111A Infection.

To maximize the potential for detecting possible subtle effects on host immune responses by viral IL-10, seronegative rhesus monkeys were challenged with a low, biologically relevant titer of RhCMV (400 plaque forming units). Like WT, ΔUL111A infection was subclinical. The absence of rhcmvIL-10 in monkeys inoculated with RhCMV-ΔUL111A did not elicit any changes in peripheral lymphoid subsets from those observed after inoculation with RhCMV-WT (Fig. S3). The virological parameters were similar between the WT and ΔUL111A groups. Low levels of viral DNA (<1,000 RhCMV genome equivalents/mL of plasma) were detected in plasma at one or two time points during the acute stage of infection. Sporadic shedding of low titers of RhCMV in saliva and urine samples was observed in both groups of animals during the acute phase of infection.

Peripheral Impact of rhcmvIL-10 on Innate Immune Responses.

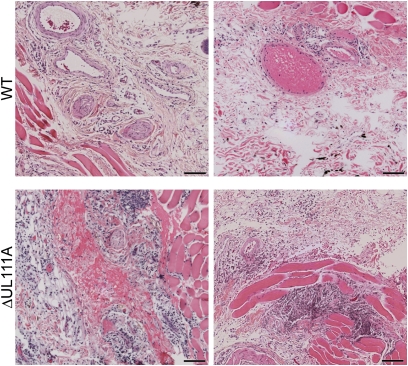

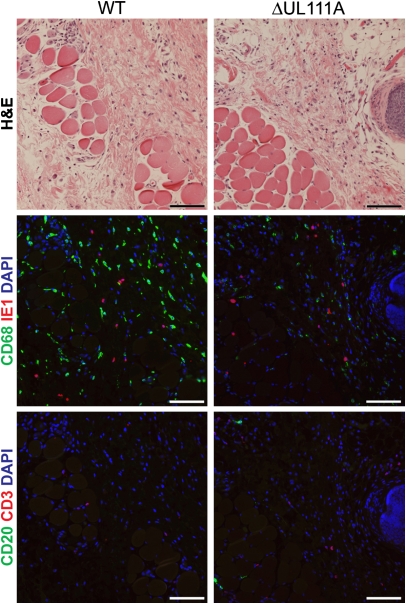

RhCMV-infected cells became detectable in biopsy samples on day 7 postinoculation (PI) in both WT and ΔUL111A groups. Skin biopsies from days 7 and 9 clearly demonstrated that infection with ΔUL111A stimulated increased inflammatory responses at the site of inoculation, compared with the parental RhCMV-WT (Fig. 2). The inflammation consisted of focal mononuclear infiltrates that extended into the subcutis and underlying muscle layer, particularly in ΔUL111A animals. Cytomegalic/IE1 antigen-positive cells were mainly contained within the connective tissue between subdermal area and muscle layer (Fig. 3 Middle), although IE1-positive cells were occasionally observed in the underlying muscle layer. To investigate the mechanism of the increased innate response stimulated by infection with ΔUL111A, immunofluorescence microscopy was used to characterize the phenotype of the mononuclear lymphocytes. Generally, there were very few T (CD3+) or B (CD20+) lymphocytes within the vicinity of IE1 antigen-positive cells (Fig. 3). The most prominent difference was observed when the antibody for CD68, a marker highly expressed by tissue macrophages, was used for immunostaining. Even though the overall cellularity was lower after WT infection, a substantially greater number of CD68+ cells was detected surrounding the WT-infected cells than were present with ΔUL111A (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Peripheral impacts of rhcmvIL-10 on innate immune responses. RhCMV-ΔUL111A infection triggers a higher level of cellularity at the site of RhCMV infection. Shown are H&E staining of skin biopsies collected on day 9 PI from two representative monkeys in each group (WT, Upper; ΔUL111A, Lower). (Bars, 100 μm.)

Fig. 3.

The presence of rhcmvIL-10 increases macrophage infiltration. A higher density of CD68+ cells was observed in situ in WT RhCMV-infected skin biopsies. Serial tissue sections were stained with H&E (Top) or immunofluorescence-labeled with antibodies for CD68 and RhCMV IE1 (Middle) or CD3 and CD20 (Bottom). DAPI was used for nuclear counterstaining. Shown are foci where similar levels of RhCMV IE1-positive cells were detected. The representative images are from biopsied collected on day 9 PI. (Bars, 100 μm.)

The increased macrophage infiltration associated with expression of rhcmvIL-10 upon RhCMV-WT infection was consistent with our in vitro findings with HCMV. Our data indicated that hcmvIL-10 has a similar effect on human CD14+ monocytes (Fig. S4 A and B). hcmvIL-10 secreted by HCMV AD169-infected cells converted the phenotype of monocytes to a mature macrophage-like phenotype within 24 h, characterized by higher levels of CD64 and CCR5 expression and reduced MHC-II expression. hcmvIL-10–treated cells also showed greater phagocytic capacity in vitro (Fig. S4C). These in vitro and in vivo findings suggested that the production of rhcmvIL-10 by RhCMV induced the differentiation of monocytes into tissue macrophages at the early stage of viral infection.

Effects of rhcmvIL-10 on Immune Activation in Draining Lymph Nodes.

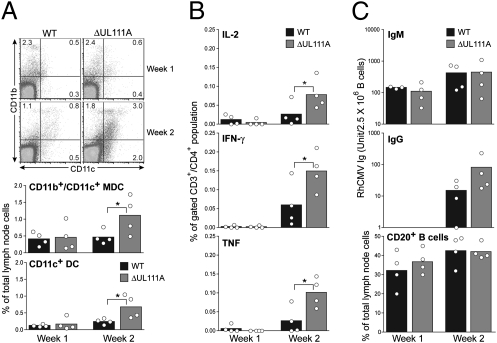

To evaluate the impact of rhcmvIL-10 on the induction of anti-RhCMV immune responses, axillary LN were biopsied at 1 and 2 wk PI. FACS analysis was used to identify the presence of various antigen-presenting cell (APC) subpopulations. Influxes of CD11b−/CD11c+/MHC-II+ DC and CD11b+/CD11c+/MHC-II+ myeloid DC (MDC) and a decrease of CD11b+/MHC-II+ cells were observed at week 2 in both WT and ΔUL111A groups (Fig. 4A). Statistical analyses indicated that there were significant increases of both CD11c+ DC and CD11b+/CD11c+ MDC in the LN of ΔUL111A-infected animals at week 2 (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the increased migration of DC subpopulations into the draining LN of ΔUL111A-infected monkeys, there were also contemporaneous increases in RhCMV-specific T cells within the LN at 2 wk PI. The frequencies of CD4+ T cells expressing either IL-2, IFN-γ, or TNF-α after stimulation with inactivated RhCMV virions ex vivo were significantly higher in animals inoculated with ΔUL111A (Fig. 4B). Only one or two monkeys in the WT group exhibited increased frequencies of antigen-specific T cells comparable to the increases observed in the four ΔUL111A monkeys. In sum, the results suggested that an absence of rhcmvIL-10 resulted in greater trafficking of MDC to the draining LN and increased priming of naïve CD4+ T cells.

Fig. 4.

Effects of rhcmvIL-10 on the induction of antiviral immunity. (A) Phenotypic analysis of LN DC populations. Shown are representative FACS plots for the expression of CD11b and CD11c after gating on live MHC-II+ cells. Numbers in each quadrant indicate the frequencies among gated live MHC-II+ cells. (Lower) The percentages of CD11b+/CD11c+ MDC and CD11c+ DC among total live LN cells. (B) Evaluation of viral-specific CD4+ T-cell responses in the draining LN after RhCMV challenge. Shown are the summaries of effector T-cell frequencies among total gated CD3+/CD4+ cells. (C) Assessment of viral-specific B-cell responses in the draining LN. Supernatants from LN cell cultures were analyzed by ELISA for secretion of virus-specific antibody. Shown are relative units of IgM (Top) and IgG (Middle) in log scale after normalization of B-cell input numbers calculated from the frequency of CD20+ cells determined by FACS (Bottom). The bars in each graph represent the averages, and the circles indicate the exact value for each monkey in that group. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t tests.

rhcmvIL-10 Reduces the Magnitude of Antiviral Humoral Immunity.

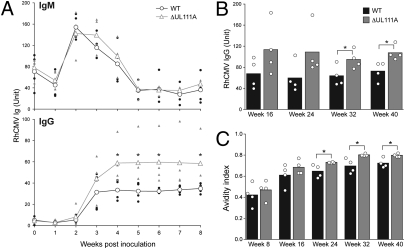

The impact of rhcmvIL-10 on cellular immunity led to the investigation of whether there was a comparable change in the induction of B-cell responses by quantifying the amounts of RhCMV-specific IgM and IgG secreted by B cells in LN cultures (Fig. 4C). Data are shown after normalization for equal number of input B cells based on the B-cell frequencies in total LN cells (Fig. 4C Bottom). IgM-secreting LN B cells were detected at week 1 PI, and their numbers increased substantially by week 2 PI (Fig. 4C Top). Both groups exhibited equivalent anti-RhCMV IgM titers at weeks 1 and 2. In contrast, RhCMV-specific IgG secreting B cells were not present in the draining LN at week 1 PI (Fig. 4C Middle). RhCMV IgG was detected at week 2 in both groups, but the titers of IgG in the WT group were notably lower than those from the ΔUL111A group (mean titers = 15 and 82, respectively). The patterns of the local B-cell responses in the draining LN at 2 wk after RhCMV infection reflected the patterns of circulating antibody responses during the 40 wk of observation. The kinetics and magnitude of systemic IgM responses between two groups of animals were indistinguishable during the first 8 wk of RhCMV infection (Fig. 5A). In contrast, WT-infected animals showed marked, and sometimes significant, reductions in circulating anti-RhCMV IgG titers from week 3 to week 8. Animals of the WT group also had lower IgG titers than those of the ΔUL111A group (average 30–45% less throughout the study) during long-term RhCMV infection (weeks 16–40) (Fig. 5B). These results supported the notion that rhcmvIL-10 compromised the initial induction of B-cell differentiation, resulting in a permanent deficit of circulating anti-RhCMV IgG in monkeys infected with WT RhCMV.

Fig. 5.

rhcmvIL-10 alters the dynamics of systemic antiviral antibody responses. (A) The kinetics of systemic antiviral IgM and IgG responses during the acute stage of RhCMV infection (plasma dilution = 1:400). The line graph represents the averages with the exact values of each monkey in that group shown as solid symbols. (B) Long-term monitoring of antiviral IgG titers during the chronic stage of RhCMV infection (plasma dilution = 1:800). (C) The progression of anti-RhCMV IgG AI values. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t tests.

rhcmvIL-10 Alters Kinetics of Antiviral Antibody Maturation.

To determine whether there were other impairments in the development of anti-RhCMV antibodies, the avidity index (AI) was quantified to measure temporal changes in the quality of mature multivalent IgG. Similar to primary HCMV infection in humans (18), the virus-specific IgG avidity in RhCMV-infected monkeys increased progressively for 32–40 wk in both groups of monkeys. The increase in AI was contemporaneous with relatively stable RhCMV-binding antibody titers (Fig. 5B). Overall, the average AI of the ΔUL111A group was higher than that of the WT group throughout the study, and statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) were observed at weeks 24, 32, and 40 (Fig. 5C). Our data indicated that rhcmvIL-10, expressed in the context of WT RhCMV infection, delayed antibody maturation and attenuated the magnitude of antiviral antibody titer.

Impacts of rhcmvIL-10 on Circulating T Cells.

The overall CD4+ T-cell responses in peripheral blood were very similar to those observed in the draining LN during the induction phase. In general, the ΔUL111A animals had a higher frequency of RhCMV-specific effector T helper cells secreting IFN-γ or IL-2 than the WT group (Fig. S5). Ex vivo proliferation assays were also performed as another metric of the quantity and quality of RhCMV-specific T-cell responses after stimulation with viral antigens. When heat-inactivated RhCMV virions were used to induce cell proliferation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), comparable CD4+ T-cell expansions were observed between WT and ΔUL111A groups (Fig. 6A). In ΔUL111A-infected animals, however, more CD4+ T cells proliferated than their WT-infected counterparts when induced by overlapping peptide pools for pp65 or IE1. Similar antigen-specific effects were also noted for CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6B). When the overlapping peptide pool for pp65 was used, CD8+ T-cell proliferation was significantly higher in PBMC from ΔUL111A-infected monkeys.

Fig. 6.

Long-term effects of rhcmvIL-10 on circulating T cells. FACS analyses of RhCMV-specific CD4+ (A) and CD8+ (B) T-cell proliferation after BrdU labeling. PBMC isolated at 40 wk PI were activated for 72 h with RhCMV viral particles, overlapping peptide pools for pp65 or IE1. (Upper) Representative FACS plots from one animal showing the gating strategy for BrdU+ cells. The percentage of proliferating cells, as indicated by boxes, among total gated live CD3+/CD4+ or CD3+/CD8+ subset is shown. Bar charts summarize the frequencies of proliferating T cells responding to different antigens, after subtracting the baseline (BrdU only). Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t tests.

Discussion

The large devotion of HCMV coding capacity to immune modulating ORF is commensurate to the magnitude of the infected host's antiviral responses to prevent immune-mediated clearance. Because the quality of the antiviral immune response is determined by the education of naïve T cells by APC early in primary infection, one potential mechanism by which HCMV could fundamentally shape the long-term virus–host balance would be to influence the earliest interactions between APC and T cells. In vitro characterization of hcmvIL-10 and our in vivo studies of RhCMV-ΔUL111A lead to a model whereby the quality and quantity of the immune response is initially determined in large part within the microenvironment of infected cells through the actions of the UL111A gene product on innate immune cells (Fig. S6). One implication of this early effect on innate immunity is that the virus can shape the long-term adaptive immune responses to viral antigens, potentially facilitating persistence in an immune-competent host.

According to this model, HCMV infection at a mucosal surface, the normal portal of HCMV entry, leads to localized replication within and underneath the epithelial barrier. Because HCMV is a slowly replicating β-herpesvirus, the temporal kinetics of hcmvIL-10 expression are such that progeny virions are released from infected cells subsequent to secretion of hcmvIL-10 into the extracellular microenvironment (9). Because of the exceedingly high affinity of hcmvIL-10 for IL-10R1 (6), which is expressed on most hematopoietic cells and those associated with innate immunity, such as monocytes and most DC subsets (7), the effects of hcmvIL-10 should be particularly prominent on the innate immune responses. Infection with RhCMV-ΔUL111A confirms this scenario. Biopsies of ΔUL111A inoculation sites demonstrate that there was greater innate recognition of viral antigens in the absence of rhcmvIL-10. This was measured by both the notable increase in the number of inflammatory cells in the vicinity of RhCMV-ΔUL111A antigen-expressing cells (Fig. 2) and their different lymphoid subset distribution (Fig. 3) compared with inoculation with RhCMV-WT. The increase in CD68+ macrophages in WT biopsies is consistent with the in vitro findings that cIL-10 (19) and hcmvIL-10 (Fig. S4) strongly induces the differentiation of CD14+ monocytes to macrophages. This may increase the number of cells permissive for productive HCMV infection as both in vitro and in vivo studies show that differentiated macrophages support productive HCMV infection (20, 21). HCMV may use hcmvIL-10 to increase the local number of permissive cells that can traffic to distal sites to facilitate dissemination and persistence while simultaneously blocking the generation of MDC.

The reduction in CD11c+ DC and CD11b+/CD11c+ MDC in the draining LN of WT animals at 2 wk (Fig. 4A) is consistent with alteration of innate immune responses by rhcmvIL-10. hcmvIL-10 significantly restricts the maturation of DC and decreases their longevity in vitro (9, 10, 12), which would provide a mechanistic basis for altered CD11b+/CD11c+ MDC trafficking from the inoculation site to the draining LN. Although MoDC exposed to hcmvIL-10 remain capable of phenotypical maturation in vitro when sufficient activation signals are provided, cytokine production is not re-established after feedback stimulation from T cells through CD40, even in the absence of hcmvIL-10 (9). Recruitment and differentiation of CD11c+ DC in the LN rely on interactions with MDC from the periphery. The lower number of CD11c+ DC in LN of WT RhCMV-infected animals may be a combination of reduced inflow of CD11b+/CD11c+ MDC, and the prolonged effects of rhcmvIL-10 on proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine expression.

HCMV is mostly transmitted across mucosal surfaces of the alimentary or urogenital tracks, where Langerhans cells within the epithelial layer and submucosal MDC in the lamina propria compose the DC network. Direct targeting of DC serves as a possible mechanism of CMV-associated immune dysfunctions. Both HCMV and mouse CMV (MCMV) have been shown to induce transient immune suppression by infecting DC and subsequently down-regulating their immunostimulatory capacity (22, 23). hcmvIL-10 should also play an important role in delaying the process of the DC network mounting a vigorous anti-HCMV defense for the following reasons: (i) most DC subsets respond to hcmvIL-10, but many of them are resistant to HCMV infection; (ii) HCMV is a slow-growing β-herpesvirus, and hcmvIL-10 is secreted before completion of the replication cycle; and (iii) as a soluble viral protein, hcmvIL-10 could rapidly bind to the high-affinity IL-10R1 on uninfected innate effector cells.

The observed alterations in adaptive immune responses with WT RhCMV infection, compared with ΔUL111A, are what would be predicted from hcmvIL-10–mediated disruption of innate immune responses. The effects on B and T cells were notable early in the axillary LN (2 wk) and generally persisted in the periphery during the course of observation. Because only IgG production in the LN and periphery differed between WT and ΔUL111A infection, and not IgM, the results suggest that rhcmvIL-10 inhibited isotype switching and/or differentiation of B cells. These results are potentially a function of the negative impact of rhcmvIL-10 on plasmacytoid DC, based on results of hcmvIL-10 (11), because type I IFNs are essential factors for the differentiation of B cells into antibody-producing plasma cells (24). The relative impairment of RhCMV-specific CD4+ T-cell responses, particularly in the LN at 2 wk, may have further attenuated antibody responses in WT RhCMV-infected animals.

The presence of rhcmvIL-10 resulted in a long-term deficit of circulating antiviral IgG in WT animals (Fig. 5B). Although antibody responses are not essential for the resolution of primary CMV infection, CMV-specific antibodies limit the severity of diseases and restrict the dissemination of virus (25, 26). A critical component of the B-cell response in limiting dissemination of virus is the development of high avidity antibodies. Attenuation of antibody maturation via rhcmvIL-10 could facilitate increased dissemination of progeny virions from the primary site of infection to distal sites in the body and seeding reservoirs of persistent virus. Our results also demonstrated that rhcmvIL-10 dampens the magnitude of antiviral T-cell immunity. This includes reductions in antiviral effector RhCMV-specific T helper cell responses and T-cell proliferation. The combined effects of viral proteins on T-cell immunity are likely to be phenotypically subtle because clinical outcomes in immune hosts are the exception. As a result, an orchestrated virus-host balance, in which normal T-cell responses are sufficient to limit pathogenesis but insufficient to prevent and/or clear a persistent infection, is established.

Another ubiquitous human herpesvirus, EBV, also encodes vIL-10 (ebvIL-10) that is highly homologous to cIL-10 (84% identity; ref. 27). Despite the high sequence conservation with cIL-10, ebvIL-10 exhibits a 1,000-fold lower binding affinity to IL-10R1 than its cellular counterpart (28). Because ebvIL-10 does not significantly alter DC functions (10), the induction of anti-EBV immunity may not be affected in a scale similar to that induced by RhCMV infection, unless a substantial amount of ebvIL-10 is secreted by infected cells. For long-term latency, it remains to be investigated whether the in vivo impact of ebvIL-10 is solely on B cells for their growth and transformation or is also on APC for attenuation of antiviral immunity.

The phenotype of rhcmvIL-10 on host immunity fits in with an emerging pattern on viral exploitation of the cIL-10 signaling pathway to augment viral persistence and, sometimes, pathogenesis. Support for this concept of cIL-10-mediated suppression of effector T-cell functions is bolstered by studies on the influence of cIL-10 on CD4+ T-cell activity and shedding in the MCMV model. MCMV does not encode its own vIL-10, but accumulating evidence indicates that viral modulation of cIL-10 activity is instrumental in MCMV natural history (29, 30). Additional evidence for direct or indirect viral manipulation of cIL-10 has been provided for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (31), hepatitis C virus (32), HIV (33), and Dengue virus (34). Together with many DNA viruses, such as RhCMV and HCMV, that have transduced cIL-10 genes into the viral genome (35), a unifying theme is that they manipulate signaling through the IL-10R as a critical component of their life cycle. The observation that HCMV strains isolated from healthy individuals retain intact UL111A ORF indicates that hcmvIL-10 is essential for the persistence of HCMV in the presence of functional immune surveillance. Conversely, two characterized HCMV strains with nonfunctional UL111A ORF due to mutations were isolated from an AIDS patient and a transplant recipient suffering from HCMV disease (36). These findings indicate that hcmvIL-10 is dispensable only under profound immune deficiency.

In summary, we provided evidence from the RhCMV model of HCMV to describe mechanisms of how HCMV utilizes hcmvIL-10 to subvert both innate and adaptive immune responses to viral challenge. The outcome of rhcmvIL-10 function is the development of inferior anti-RhCMV immune reactions with altered kinetics and/or compromised quantity and quality.

Materials and Methods

Cells, Viruses, and Virus Mutagenesis.

WT RhCMV (strain 68-1, ATCC VR-677) and BAC-derived RhCMV variants were propagated and titrated by plaque assay in telomerase-immortalized rhesus fibroblasts (Telo-RF) as described previously (16). The full-length RhCMV BAC plasmid (16) was mutated by ET recombination in Escherichia coli using the Red/ET Subcloning Kit (Gene Bridges, Germany). The procedures of mutagenesis and mutant confirmation are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Rhesus Macaques.

Eight 15- to 20-mo-old male rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) serologically negative for RhCMV were challenged s.c. with 400 PFU of WT (n = 4) or ΔUL111A (n = 4) RhCMV. Viruses were delivered in four 0.1-mL volumes in four separate sites on the back of the animal, and the inoculation sites were marked with indelible ink for skin biopsy. Two skin biopsies (day 5 or 7 and day 9) and two axillary LN biopsies (weeks 1 and 2) were obtained from each monkey. Peripheral blood samples, as well as oral and genital swabs, were collected longitudinally after challenge (weekly for week 0–12, biweekly for week 12–28, monthly for week 28–40). Blood samples were processed for PBMC and plasma. DNA was purified from plasma, oral and genital swabs as described (16). Animals were housed at the California National Primate Research Center in accordance with the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care standards. All animal protocols were approved in advance by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, Davis.

Primary Cell Isolation and Generation.

The procedures of rhesus monkey PBMC and LN cell isolation, and generation of MoDC from CD14+ monocytes are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Microscopy.

Serial sections (5 μm) of paraformaldehyde-fixed paraffin-embedded skin biopsies were processed for H&E staining or multiple immunofluorescence labeling (described in SI Materials and Methods).

Flow Cytometry.

Four-color flow cytometry was performed using a FACSCalibur cell sorter operated by CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed and illustrated with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Local And Systemic Immune Resposnes.

Freshly isolated PBMC and LN cells were used to evaluate RhCMV-specific T-cell responses, including cytokine secretion and proliferation. To evaluate the early B-cell activity, LN cells were cultured in 24-well plates (5 × 106 cells/mL) for 24 h. Supernatants were collected and stored at −80 °C until assayed. Longitudinally collected plasma samples were processed by heat-inactivation at 56 °C for 30 min, followed by centrifugation (2,400 × g, 10 min). The supernatants were collected and stored at 4 °C until assayed. The procedures of intracellular cytokine assay, T-cell proliferation assay, in-house RhCMV ELISA, and avidity assay are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Statistical Analysis.

Data were analyzed by the Student's t tests (unpaired, one-tailed) or by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison tests using Prism software (GraphPad) (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Y. Lee and K. W. Yang for excellent technical assistance. We also thank Leanne Gill and Phil Allan for coordinating in vivo experiments. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01AI049342 (to P.A.B.) and P51RR000169 (to California National Primate Research Center), and the Margaret M. Deterding Infectious Disease Research Support Fund (to P.A.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1013794108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sylwester AW, et al. Broadly targeted human cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells dominate the memory compartments of exposed subjects. J Exp Med. 2005;202:673–685. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunn W, et al. Functional profiling of a human cytomegalovirus genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14223–14228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2334032100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crough T, Khanna R. Immunobiology of human cytomegalovirus: from bench to bedside. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:76–98. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00034-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lockridge KM, et al. Primate cytomegaloviruses encode and express an IL-10-like protein. Virology. 2000;268:272–280. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotenko SV, Saccani S, Izotova LS, Mirochnitchenko OV, Pestka S. Human cytomegalovirus harbors its own unique IL-10 homolog (cmvIL-10) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1695–1700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones BC, et al. Crystal structure of human cytomegalovirus IL-10 bound to soluble human IL-10R1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9404–9409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152147499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O'Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spencer JV, et al. Potent immunosuppressive activities of cytomegalovirus-encoded interleukin-10. J Virol. 2002;76:1285–1292. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1285-1292.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang WL, Baumgarth N, Yu D, Barry PA. Human cytomegalovirus-encoded interleukin-10 homolog inhibits maturation of dendritic cells and alters their functionality. J Virol. 2004;78:8720–8731. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8720-8731.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raftery MJ, et al. Shaping phenotype, function, and survival of dendritic cells by cytomegalovirus-encoded IL-10. J Immunol. 2004;173:3383–3391. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang WL, Barry PA, Szubin R, Wang D, Baumgarth N. Human cytomegalovirus suppresses type I interferon secretion by plasmacytoid dendritic cells through its interleukin 10 homolog. Virology. 2009;390:330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang WL, et al. Exposure of myeloid dendritic cells to exogenous or endogenous IL-10 during maturation determines their longevity. J Immunol. 2007;178:7794–7804. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spencer JV, Cadaoas J, Castillo PR, Saini V, Slobedman B. Stimulation of B lymphocytes by cmvIL-10 but not LAcmvIL-10. Virology. 2008;374:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barry PA, Chang WL. In: Primate Betaherpesviruses. Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy and Immunoprophylaxis. Arvin A, et al., editors. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007. pp. 1051–1075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen SG, et al. Evasion of CD8+ T cells is critical for superinfection by cytomegalovirus. Science. 2010;328:102–106. doi: 10.1126/science.1185350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang WL, Barry PA. Cloning of the full-length rhesus cytomegalovirus genome as an infectious and self-excisable bacterial artificial chromosome for analysis of viral pathogenesis. J Virol. 2003;77:5073–5083. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5073-5083.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muyrers JP, Zhang Y, Testa G, Stewart AF. Rapid modification of bacterial artificial chromosomes by ET-recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1555–1557. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.6.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grangeot-Keros L, et al. Value of cytomegalovirus (CMV) IgG avidity index for the diagnosis of primary CMV infection in pregnant women. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:944–946. doi: 10.1086/513996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sozzani S, et al. Interleukin 10 increases CCR5 expression and HIV infection in human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:439–444. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.3.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibanez CE, Schrier R, Ghazal P, Wiley C, Nelson JA. Human cytomegalovirus productively infects primary differentiated macrophages. J Virol. 1991;65:6581–6588. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6581-6588.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinzger C, Plachter B, Grefte A, The TH, Jahn G. Tissue macrophages are infected by human cytomegalovirus in vivo. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:240–245. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.1.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andrews DM, Andoniou CE, Granucci F, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Degli-Esposti MA. Infection of dendritic cells by murine cytomegalovirus induces functional paralysis. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:1077–1084. doi: 10.1038/ni724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kvale EO, et al. CD11c+ dendritic cells and plasmacytoid DCs are activated by human cytomegalovirus and retain efficient T cell-stimulatory capability upon infection. Blood. 2006;107:2022–2029. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jego G, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce plasma cell differentiation through type I interferon and interleukin 6. Immunity. 2003;19:225–234. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boppana SB, Britt WJ. Antiviral antibody responses and intrauterine transmission after primary maternal cytomegalovirus infection. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1115–1121. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.5.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jonjić S, et al. Antibodies are not essential for the resolution of primary cytomegalovirus infection but limit dissemination of recurrent virus. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1713–1717. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu DH, et al. Expression of interleukin-10 activity by Epstein-Barr virus protein BCRF1. Science. 1990;250:830–832. doi: 10.1126/science.2173142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, et al. The EBV IL-10 homologue is a selective agonist with impaired binding to the IL-10 receptor. J Immunol. 1997;158:604–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cavanaugh VJ, Deng Y, Birkenbach MP, Slater JS, Campbell AE. Vigorous innate and virus-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses to murine cytomegalovirus in the submaxillary salivary gland. J Virol. 2003;77:1703–1717. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.3.1703-1717.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humphreys IR, et al. Cytomegalovirus exploits IL-10-mediated immune regulation in the salivary glands. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1217–1225. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brooks DG, et al. Interleukin-10 determines viral clearance or persistence in vivo. Nat Med. 2006;12:1301–1309. doi: 10.1038/nm1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaplan DE, et al. Peripheral virus-specific T-cell interleukin-10 responses develop early in acute hepatitis C infection and become dominant in chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2008;48:903–913. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alter G, et al. IL-10 induces aberrant deletion of dendritic cells by natural killer cells in the context of HIV infection. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1905–1913. doi: 10.1172/JCI40913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ubol S, Phuklia W, Kalayanarooj S, Modhiran N. Mechanisms of immune evasion induced by a complex of dengue virus and preexisting enhancing antibodies. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:923–935. doi: 10.1086/651018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slobedman B, Barry PA, Spencer JV, Avdic S, Abendroth A. Virus-encoded homologs of cellular interleukin-10 and their control of host immune function. J Virol. 2009;83:9618–9629. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01098-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cunningham C, et al. Sequences of complete human cytomegalovirus genomes from infected cell cultures and clinical specimens. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:605–615. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.015891-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.