Abstract

We showed previously that pulmonary function and arterial oxygen saturation in NY1DD mice with sickle cell disease (SCD) are improved by depletion of invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells or blockade of their activation. Here we demonstrate that SCD causes a 9- and 6-fold induction of adenosine A2A receptor (A2AR) mRNA in mouse pulmonary iNKT and natural killer (NK) cells, respectively. Treating SCD mice with the A2AR agonist ATL146e produced a dose-dependent reversal of pulmonary dysfunction with maximal efficacy at 10 ng/kg/minute that peaked within 3 days and persisted throughout 7 days of continuous infusion. Crossing NY1DD mice with Rag1−/− mice reduced pulmonary injury that was restored by adoptive transfer of 106 purified iNKT cells. Reconstituted injury was reversed by ATL146e unless the adoptively transferred iNKT cells were pretreated with the A2AR alkylating antagonist, FSPTP (5-amino-7-[2-(4-fluorosulfonyl)phenylethyl]-2-(2-furyl)-pryazolo[4,3-ϵ]-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidine), which completely prevented pro-tection. In NY1DD mice exposed to hypoxia-reoxygenation, treatment with ATL146e at the start of reoxygenation prevented further lung injury. Together, these data indicate that activation of induced A2ARs on iNKT and NK cells in SCD mice is sufficient to improve baseline pulmonary function and prevent hypoxia-reoxygenation–induced exacerbation of pulmonary injury. A2A agonists have promise for treating diseases associated with iNKT or NK cell activation.

Introduction

Individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD) express a mutated form of β-globin, which associates with α-globin to produce hemoglobin S (HbS). Polymerization of deoxygenated HbS is the precipitating event in the molecular pathogenesis of SCD and causes characteristic sickle erythrocyte morphology and reduced hemoglobin oxygen binding capacity. Patients with SCD have periodic episodes of painful vaso-occlusive episodes known as vaso-occlusive crisis and in some cases life-threatening pulmonary vaso-occlusion referred to as acute chest syndrome. Historically, microvascular occlusion was attributed to rigid sickled erythrocytes. Recently, ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI) with resultant white cell activation has been implicated as an additional contributor to the pathophysiology of SCD.1–3

Mechanisms of vasculopathy in sickle mice include global dysregulation of the NO axis due to impaired constitutive nitric oxide synthase activity, increased NO scavenging by plasma hemoglobin and superoxide, increased arginase activity, and depleted intravascular nitrite reserves.4 Other factors that contribute to oxidative injury in SCD include the release of xanthine oxidase from injured liver5 and superoxide anions from activated mononuclear cells and neutrophils.6,7 Vaso-occlusion in SCD appears to be mediated by interactions between activated endothelial cells, platelets, sickled red blood cells, and leukocytes, resulting in blood flow abnormalities and ischemic episodes.2,8,9 Because the pulmonary arterial circulation has low oxygen tension and low blood velocity and constricts in response to hypoxia, the lung micro-environment is particularly conducive to the polymerization of HbS and therefore is highly vulnerable to IRI.10 Pulmonary disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with SCD.10–12

A well characterized experimental model of moderate SCD is the NY1DD mouse (αHβS[βMDD]) that is homozygous for a spontaneous deletion of mouse βmajor-globin locus (βMDD) and carries a human α- and βS-globin fused transgene (αHβS).13,14 Like SCD patients at baseline, NY1DD mice exhibit a proinflammatory phenotype that is believed to contribute to morbidity and mortality.2,15,16 Baseline pulmonary inflammation and dysfunction is exacerbated by hypoxia-reoxygenation (H-R), analogous to human acute chest syndrome.3

A2AR agonists reduce inflammation in several models of lung injury,17–20 and reduce IRI in heart, liver, and kidney. A2AR activation reduces neutrophil accumulation, superoxide generation, endothelial adherence, and the expression of adhesion molecules.21–25 A2ARs are expressed on most inflammatory cells, including neutrophils, macrophages, eosinophils, T cells, NK cells, platelets, and some epithelial and endothelial cells.26 Due to coupling to Gs, A2A agonists signal primarily through cyclic AMP, which acts in part by inhibiting NF-κβ.19,27 Recently, we demonstrated that a minor lymphocyte subset, iNKT cells, plays a pivotal role in mediating protection of tissues from IRI by A2A agonists.28,29 Because SCD is characterized by ongoing microvascular IRI, we examined the role of iNKT cells in SCD. Deletion or blockade of iNKT cell activation was found to greatly attenuate pulmonary vaso-occlusive pathophysiology in NY1DD mice. In addition, SCD patients were found to have increased numbers of activated iNKT cells in their blood.1 These findings suggest that iNKT cells orchestrate a leukocyte inflammatory cascade that triggers vaso-occlusive episodes. Evidence of NKT cell activation in SCD provided the rational for the current study in which we investigated the effects of A2AR activation on pulmonary function in SCD. The results indicate that A2AR agonists produce substantial protection to lungs in SCD, primarily by targeting A2A receptors that are induced on iNKT cells.

Methods

Animals

NY1DD mice were a gift from R. Hebbel (University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN). Congenic 12- to 16-week-old wild-type C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. NY1DD x A2AR−/− mice were created by crossing NY1DD and A2AR−/− mice and identified by PCR for the human βS-globin transgene, mouse Βmajor deletion, and the A2AR−/− deletion. NY1DD x Rag1−/− mice were created by crossing NY1DD and Rag1−/− mice and identified by PCR for the Rag1−/− deletion. The Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Virginia approved all animal protocols.

Vascular permeability

Pulmonary vascular permeability was evaluated by measuring extravasation of Evans blue dye (EBD; 30 mg/kg body weight, 200 μL) injected intravenously in anesthetized mice and allowed to circulate for 30 minutes. The chest was opened, the inferior vena cava transected, and the pulmonary vasculature flushed with 10 mL of saline via the right ventricle to remove intravascular dye. The lung lobes were removed, weighed, homogenized, and incubated in 100% formamide at 37°C for 24 hours to extract EBD. The concentration of EBD extracted was analyzed by spectophotometry. Correction of optical densities (E) for contaminating heme pigments was performed as previously described, using the equation E620(corrected) = E620 − (1.426 × E740 + 0.03).30 Data are reported as micrograms of EBD per gram of lung.

Arterial oxygen saturation

Animals were anesthetized and the skin and musculature over the left chest were dissected. A left ventricular heart puncture was performed with a heparinized syringe, and 150 μL of arterial blood was collected for gas analysis (Osmetech OPTI CCA).

Pulmonary immunohistochemistry

Mice were killed, the chests were opened, the inferior vena cava were transected, and the pulmonary vasculatures were flushed with 10 mL of saline via the right ventricle. The lungs were inflation fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde-lysine-periodate at a height of 25 cm. Paraffin sections (5-μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Unrestrained whole body plethysmography and H-R

Frequency of breathing (FOB) and tidal volume (TV) were evaluated using unrestrained whole body plethysmography. Mice were placed into calibrated plexiglas chambers that were connected to a direct airflow sensor (Buxco Max II, Buxco Electronics Inc). Airflow through the chambers was maintained at 70 mL/minute. The flow signals were recorded using IOX software (EMKA Technologies). Respiratory function was averaged for 20 minutes after a 20-minute adjustment period. Some mice were subjected to 3 hours of hypoxia (8% O2) followed by 18 hours of reoxygenation in room air.

Immunostaining of cells for flow cytometry and determination of absolute numbers of leukocytes

Immunostaining and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) were performed as previously described.1 Briefly, saline perfused lungs were removed, minced, and incubated in digestion buffer. Cells were resuspended, treated with α-Fcγ receptor antibodies, stained with the αGalCer-analog (PBS57)–loaded CD1d tetramer, and stained with other cell surface markers. A fixable LIVE/DEAD stain was used for viability (Invitrogen). Cells were then fixed and permeabilized for intracellular staining with IFN-γ. Fluorescence intensity was measured with a CyAn ADP LX 9 Color analyzer (DakoCytomation) and data analyses were performed with FlowJo software Version 7.6.1 mac (TreeStar). Live and CD45+ leukocytes were identified by the following staining: Neutrophils: 7/4+, CD11b+, and Ly-6G+; NK cells: NKp46+ and CD3e−; iNKT cells: CD1d-tetramer+ and CD3e+; CD4 T cells: CD1d-tetramer−, CD3ϵ+, and CD4+; CD8 T cells: CD1d-tetramer−, CD3ϵ+, and CD8α+. The absolute number of pulmonary leukocytes was determined from analysis with counting beads (Invitrogen).

Cell sorting and quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for A2AR

Live (DAPI− [4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole] negative) leukocytes (CD45+) were sorted (FACSVantage SE Turbo Sorter) based upon cell surface antigens: iNKT cells (CD1d-tetramer+, CD3+), NK cells (NKp46+, CD3−), and T cells (CD1d-tetramer−, CD3+). Cells were resuspended in Tri-reagent (Ambion). RNA was extracted, and cDNA was reverse-transcribed using the manufacturer's instructions (iScript cDNA Synthesis kit; Bio-Rad). Quantitative PCR was performed using the Quantitect SYBR Green PCR kit (QIAGEN). Real-time PCR was performed using the iCycler iQ Real-Time PCR Detection System from Bio-Rad using the supplied software. The thermal cycler tracks fluorescence levels over 40 amplification cycles. A melt curve was performed at the end of each run to verify that there was a single amplification product and a lack of primer dimers. All samples were normalized to the amount of cyclophilin mRNA present in the sample. Data are represented as fold change compared with C57BL/6 mRNA expression. A2AR primers: Forward: 5′-TGGCTTGGTGACGGGTATG-3′; Reverse: 5′-CGCAGGTCTTTGTGGAGTTC-3′.

A2AR agonist treatment

Three-day or 7-day Alzet-minipumps containing ATL146e (1 ng/kg/minute, 10 ng/kg/minute, or 30 ng/kg/minute) or vehicle (saline, 0.2% dimethylsulfoxide [DMSO]) were implanted subcutaneously at the midscapular level into C57BL/6J, NY1DD, and NY1DD x A2AR−/− mice. Animals were killed at various time points and analyzed for pulmonary inflammation.

Antibody treatments

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with anti-CD1d mAb (1B1; 10 μg/g/day; 2 days) to inhibit CD1d-restricted NKT cell activation (controls were treated with rIgG2b). Antibodies were purified from hybridomas in the University of Virginia Lymphocyte Core. The hybridoma was a gift from Mitch Kronenberg (La Jolla Institute of Allergy and Immunity).

Isolation and adoptive transfer of iNKT cells and FSPTP treatment

GFP-C57BL/6 animals were injected with polyclonal anti–Asialo-GM1 for 2 days to deplete NK cells. Splenocytes were passed over a T-cell enrichment column (R&D Systems) and eluted cells were incubated with anti-NK1.1–phycoerythrin (PE). Cells were incubated with magnetic anti-PE beads (Miltenyi Biotec) and purified by magnetic isolation. By FACS analysis, 85% of the resulting cells were NKT cells and not activated (baseline CD69 expression). Some cells were incubated with 200nM FSPTP (5-amino-7-[2-(4-fluorosulfonyl)phenylethyl]-2-(2-furyl)-pryazolo[4,3-ϵ]-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidine) an A2AR alkylating agent31 or vehicle (saline, 2% DMSO) for 30 minutes. One million cells were injected retro-orbitally 1 day before experimentation.

Statistical analysis

Prism software (GraphPad) was used for all statistical analyses. Unpaired t tests and 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Neuman-Keuls posttesting were used to compare experimental groups. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttesting was used to compare experimental groups to each other over time. A P value of < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Pulmonary iNKT and NK cells from NY1DD mice have increased A2AR mRNA

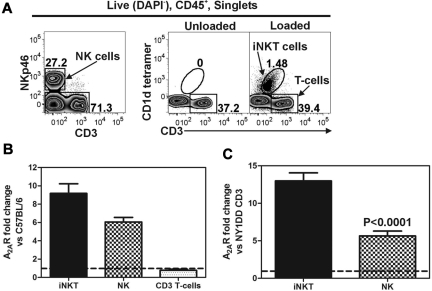

We used FACS to collect live (DAPI−) and CD45+ pulmonary iNKT (CD1d-tetramer+, CD3+), NK (NKp46+, CD3−), and CD3+ T cells (CD1d-tetramer−, CD3+) for analysis (Figure 1A). Quantitative RT-PCR was used to measure the transcript levels of the A2AR in sorted populations of pulmonary lymphocytes. Compared with C57BL/6 mice, NY1DD mice have increased transcript levels for A2AR in iNKT cells (9.2 ± 1.0-fold) and NK cells (6.1 ± 0.5-fold), whereas T cells have no change in A2AR mRNA (0.8 ± 0.1-fold; Figure 1B). Furthermore, when comparing the ratio of A2AR/cyclophylin transcripts in cells derived from NY1DD lungs, NKT and NK cells ratios are 13.0 ± 1.1- and 5.6 ± 0.6-fold higher, respectively, than T cells (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Lung lymphocytes from NY1DD mice have higher A2AR mRNA than congenic C57BL/6 controls. Live (DAPI−) CD45+ pulmonary cells were sorted based on surface antigen staining. (A) iNKT (CD1d-tetramer+, CD3+), NK (NKp46+, CD3−), and CD3+ T cells (CD1d-tetramer−, CD3+). Quantitative RT-PCR was used to measure A2AR transcript levels in sorted populations of pulmonary lymphocytes compared with a housekeeper transcript (cyclophilin). (B) NY1DD mice have increased levels of A2AR transcripts in iNKT cells and NK cells, but not in CD3+ tetramer− T cells compared with C57BL/6 mice. (C) NY1DD iNKT and NK cells have increased A2AR/cyclophilin mRNA ratios compared with NY1DD CD3+ tetramer− T cells.

ATL146e decreases pulmonary inflammation and dysfunction in NY1DD mice

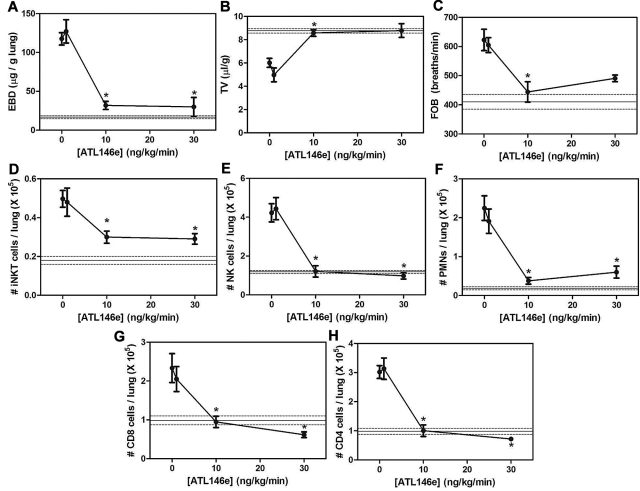

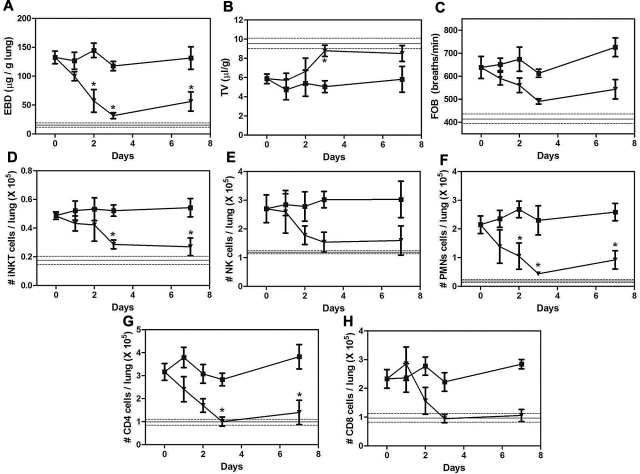

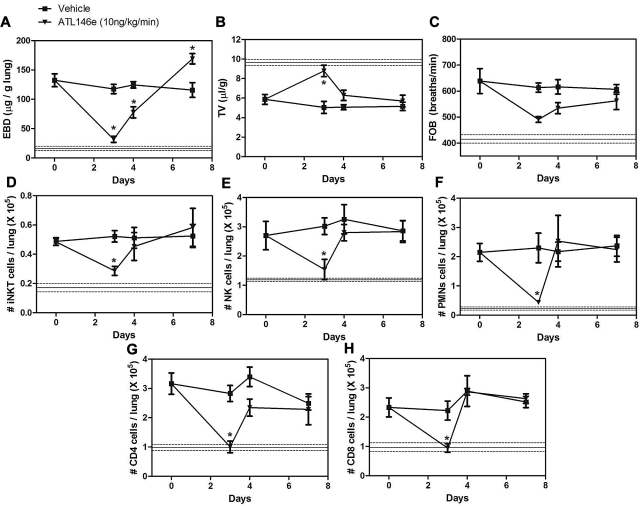

The increased A2AR mRNA in pulmonary lymphocytes from NY1DD mice led us to hypothesize that activation of the A2AR might potently ameliorate pulmonary dysfunction found in these animals. To determine the optimal dose and duration of ATL146e (a selective A2AR agonist), NY1DD mice were treated with infusions of ATL146e via subcutaneous osmotic pumps. Previous studies of IRI indicated that an infusion rate of 10 ng/kg/minute optimally decreased injury.32–34 Vascular permeability (Evans blue dye accumulation), leukocyte infiltration (FACS analysis of lung leukocyte number), and breathing parameters (TV and FOB) were used as indices of pulmonary inflammation and dysfunction. Optimal improvement in lung function over 3 days was observed at an infusion rate of 10 ng/kg/minute, and no additional improvement was seen with 30 ng/kg/minute (Figure 2A-C). The pulmonary accumulation of inflammatory cells, iNKT, NK, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, CD8+, and CD4+ were all significantly reduced during ATL146e infusion (Figure 2D-H). Many of the pulmonary functional and inflammatory parameters were improved to near normal values seen in C57BL/6 mice, indicated by the horizontal lines in Figure 2. We next examined the effects of the optimal dose of ATL146e during 7 days of continuous infusion (Figure 3). The improvement in pulmonary function remained stable between 3 and 7 days of compound infusion, indicative of little or no desensitization to the beneficial effects of the A2AR agonist over this time frame.

Figure 2.

Dose dependence of ATL146e to reduce lung injury and inflammation in NY1DD mice. NY1DD mice (N = 4) were treated for 3 days with a constant infusion of vehicle or ATL146e (1 ng/kg/minute, 10 ng/kg/minute, and 30 ng/kg/minute, osmotic pump). All parameters were found to be maximally improved by 10 ng/kg/minute. The solid and dashed lines represent the mean ± SEM of parameters from congenic C57BL/6 mice. Data were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA with Neuman-Keuls posttesting. *P < .05 vs day 0.

Figure 3.

Time course of ATL146e effects in NY1DD mice. NY1DD mice were treated with osmotic minipumps infusing vehicle (■) or ATL146e (10 ng/kg/minute, osmotic pump, ▾). Pulmonary parameters were measured in NY1DD mice treated for 0, 1, 2, 3, or 7 days after the start of infusion. All parameters were maximally improved by 3 days after the start of ATL146e treatment, because no further changes were noted on day 7. The solid and dashed lines represent the mean ± SEM of parameters from congenic C57BL/6 mice. Data were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA with Neuman-Keuls posttesting. *P < .05 vs day 0.

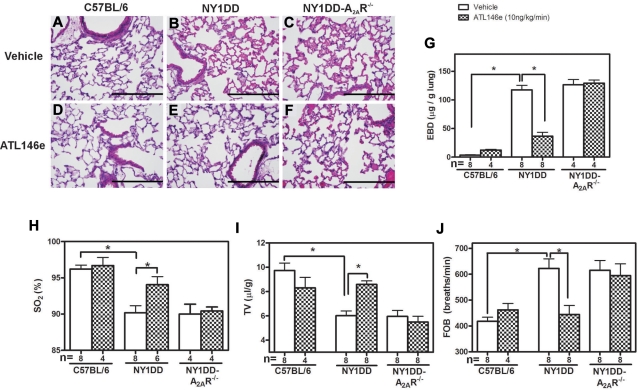

To ensure that the effects of ATL146e are mediated entirely by signaling through the A2AR, we next compared the effects of ATL-146e on pulmonary responses in NY1DD and NY1DD x A2AR−/− mice. Based on lung histology, ATL146e had no effect on C57BL/6 mice (Figure 4A,D), reversed pulmonary vaso-clusion in NY1DD mice (Figure 4B,E) and failed to reverse vaso-occlusion in NY1DD mice lacking the A2AR (Figure 4C,F). ATL146e-treated NY1DD mice had significantly decreased vascular permeability (3.2-fold decrease compared with vehicle NY1DD mice; P < .05) and increased arterial oxygen saturation (94% compared with 90% in vehicle-treated NY1DD mice; P < .05; Figure 4G-H). TV increased 1.4-fold (P < .05), and FOB decreased from 624 breaths per minute to 444 breaths per minute (P < .05; Figure 4I-J). All of the effects of ATL146e in NY1DD were absent in mice lacking A2ARs.

Figure 4.

ATL146e treatment decreases pulmonary dysfunction in NY1DD mice by activation of the A2AR. C57BL/6, NY1DD, or NY1DD x A2AR−/− mice were treated with ATL146e (10 ng/kg/minute, 3 days) or vehicle (saline, 0.2% DMSO). (A-F) Lung sections from NY1DD mice, but not NY1DD x A2AR−/− mice have reduced alveolar thickening and reduced vaso-occlusion after ATL146e treatment. (G-H) NY1DD mice, but not NY1DD x A2AR−/− mice, had decreased vascular permeability and increased oxygen saturation after ATL146e treatment. (I-J) NY1DD mice, but not NY1DD x A2AR−/− mice, displayed improved breathing parameters after ATL146e treatment. Data were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA with Neuman-Keuls posttesting; *P < .05. SO2: arterial oxygen saturation.

To determine whether ATL146e had any effect on intrapulmonary leukocytosis we used FACS analysis to define white blood cell populations in digested whole lung tissue. Compared with vehicle-treated NY1DD mice, ATL146e-treated NY1DD mice had significantly decreased numbers of pulmonary leukocytes (iNKT cells, 1.7-fold; NK cells, 3.5-fold; CD4 T cells, 3-fold; CD8 T cells, 2.5-fold; and polymorphonuclear leukocytes, 5.8-fold; Table 1).

Table 1.

ATL146e decreases pulmonary leukocytosis in NY1DD mice by activating adenosine A2ARs

| Cells (105) | (a) C57BL/6 vehicle (n = 8) | (b) C67BL/6 ATL146e (n = 4) | (c) NY1DD vehicle (n = 8) | (d) NY1DD ATL146e (n = 8) | (e) NY1DD- A2AR−/− vehicle (n = 6) | (f) NY1DD-A2AR−/− ATL146e (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iNKT | 0.19 (0.02) | 0.13 (0.02) | 0.5 (0.04)* | 0.29 (0.03)** | 0.58 (0.05) | 0.55 (0.09) |

| NK | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.3) | 4.2 (0.5)* | 1.2 (0.3)** | 4.0 (0.5) | 4.1 (0.4) |

| CD4 | 1.0 (0.09) | 1.3 (0.4) | 3.0 (0.2)* | 1.0 (0.2)** | 3.3 (0.8) | 3.2 (0.7) |

| CD8 | 1.1 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.2) | 2.3 (0.4)* | 0.9 (0.1)** | 2.8 (0.4) | 2.9 (0.3) |

| PMNs | 0.3 (0.07) | 0.3 (0.1) | 2.3 (0.3)* | 0.4 (0.1)** | 2.9 (0.7) | 3.1 (0.5) |

Treatment of C57BL/6 mice with ATL146e (10 ng/kg/minute) has no effect on pulmonary leukocyte numbers (b vs a). In NY1DD mice, pulmonary leukocytes are elevated (c vs a) and treatment with ATL146e counteracts this effect (d vs c). Deletion of the A2AR from NY1DD mice eliminates the effect of ATL146e to reduce leukocyte numbers (f vs e). Data represents means ± SEM and were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA with Neuman-Keuls posttesting.

P < .05 (a vs c).

P < .05 (c vs d).

ATL146e decreases hypoxia-reoxygenation induced pulmonary inflammation and dysfunction

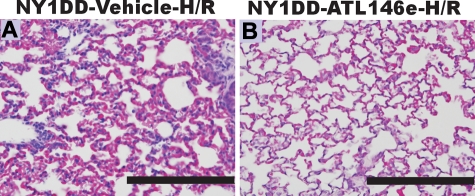

Because ATL146e elicited protective effects at baseline, we reasoned that treatment with ATL146e might attenuate exacerbated hypoxia-reoxygenation induced pulmonary injury in NY1DD mice. NY1DD mice were treated with hypoxia (8% O2) for 3 h and then reoxygenated (room air) for 18 hours. Three hours into the reoxygenation period, mice were infused with ATL146e via osmotic pump (10 ng/kg/minute) or vehicle (saline, 0.2% DMSO). This protocol was designed to model acute chest syndrome, a situation in which treatment would not be started until after symptoms of pulmonary distress appeared. The H-R treatment of NY1DD mice exacerbated pulmonary vaso-occlusion, vascular permeability and accumulation of neutrophils. NY1DD mice treated with ATL146e displayed decreased signs of H-R-induced pulmonary vaso-occlusion and inflammation (Figure 5; Table 2).

Figure 5.

ATL146e treatment decreases pulmonary injury during hypoxia-reoxygenation (H-R) of NY1DD mice. NY1DD mice were subjected to 3 hours of hypoxia (8% oxygen) and 18 hours of reoxygenation. Lungs were then removed, inflation-fixed, and stained with H&E or immunostained for neutrophils. Three hours after reoxygenation, mice were implanted with Alzet minipumps containing either vehicle (A) or ATL146e (10 ng/kg/minute; B). The sections shown are typical of 4 replicates. Bars, 200 μm.

Table 2.

ATL146e decreases H-R–induced pulmonary inflammation

| Cells (105) | Normoxia |

Hypoxia-reoxygenation |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) NY1DD vehicle (n = 8) | (b) NY1DD ATL146e (n = 8) | (c) NY1DD vehicle (n = 6) | (d) NY1DD ATL146e (n = 6) | |

| iNKT | 0.5 (0.04) | 0.29 (0.03)* | 1.1 (0.2)* | 0.26 (0.05)** |

| NK | 4.2 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.3)* | 3.0 (0.6) | 1.6 (0.2) |

| CD4 | 3.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2)* | 3.3 (1.0) | 0.5 (0.1)** |

| CD8 | 2.3 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.1)* | 3.1 (0.9) | 0.5 (0.1)** |

| PMNs | 2.3 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.1)* | 9.8 (4.1)* | 1.1 (0.5)** |

| EBD | 117.5 (7.9) | 36.7 (6.7)* | 191.9 (19.3)* | 53.1 (12.2)** |

NY1DD mice were subjected to 3 hours of hypoxia (8% O2) followed by 18 hours of reoxygenation (room air). NY1DD mice subjected to hypoxia-reoxygenation displayed significant increases in pulmonary iNKT cells and polymorphonuclear leukocytes compared to normoxic controls as well as increased vascular permeability (c vs a). Three hours into reoxygenation Alzet minipumps were implanted to infuse vehicle or ATL146e (10 ng/kg/minute). NY1DD mice treated with ATL146e during reoxygenation displayed significantly decreased pulmonary leukocytes and improved vascular permeability (d vs c). Data represents means ± SEM and were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA with Neuman-Keuls posttesting.

P < .05 (vs a).

P < .05 (vs c).

The protective effects of ATL146e on pulmonary inflammation and dysfunction in NY1DD mice are transient

The A2AR is a G-protein–coupled receptor that responds rapidly to the presence or absence of its ligand. To assess the reversibility of protection conferred by ATL146e on pulmonary function, we treated NY1DD mice with an infusion of ATL146e (10 ng/kg/minute) for 3 days and assessed pulmonary injury either 1 day or 4 days after the cessation of treatment. One day after stopping ATL146e treatment, pulmonary parameters began to return to baseline NY1DD levels, and by 4 days after treatment, pulmonary parameters had returned to baseline (Figure 6). These data suggest that it is unlikely that beneficial effects of A2AR agonist treatment will persist for long periods after the compound is withdrawn.

Figure 6.

Time course of reversal from pulmonary protection after cessation of ATL146e. NY1DD mice were treated with ATL146e (10 ng/kg/minute, 3 days osmotic pump). Pulmonary parameters were measured on days 3, 4, and 7 after the cessation of ATL146e infusion. All parameters measured (vascular permeability [EBD], breathing measurements [TV, FOB], and pulmonary cell infiltrates) returned toward NY1DD baseline levels on day 4, 1 day after the cessation of ATL146e treatment, and returned to baseline levels by day 7. The solid and dashed lines represent the mean ± SEM of breathing parameters in C57BL/6 mice. Data were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA with Neuman-Keuls posttesting. *P < .05.

A2ARs on iNKT cells are the principal targets of ATL146e in ameliorating pulmonary inflammation and injury in NY1DD mice

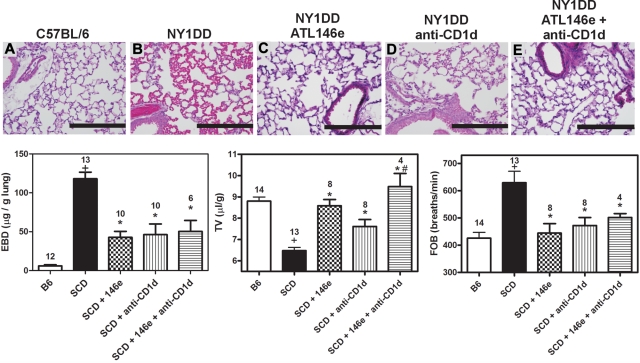

We have previously shown that inhibiting NKT cell activation with anti-CD1d treatment ameliorates pulmonary dysfunction in NY1DD mice.1 Based on this finding and the strong induction of A2AR mRNA in iNKT cells of NY1DD mice (Figure 1) we reasoned that iNKT cells might be the principal targets of ATL146e despite the expression of A2ARs on other leukocytes. NY1DD mice were treated with an infusion of ATL146e (10 ng/kg/minute, 3 days), anti-CD1d (10 μg/g/day, 2 days), or a combination of both. Treatment of NY1DD mice with either ATL146e or anti-CD1d significantly decreased pulmonary injury. However, treatment with both ATL146e and anti-CD1d did not confer any additional protection compared with either treatment alone (Figure 7; Table 3).

Figure 7.

Protective effects of ATL146e and anti-CD1d treatments to reduce pulmonary inflammation in NY1DD. NY1DD mice were treated with either ATL146e (10 ng/kg/minute, 3 days), anti-CD1d (10 μg/g/day, 2 days), or a combination of both. All treatments resulted in significantly improved pulmonary parameters. (A-E) Representative H&E staining from sections of lungs at baseline illustrating reduced alveolar thickening and vaso-acclusion as a result of ATL146e or anti-CD1d treatment. (F-H) ATL146e or anti-CD1d treatment improved parameters of pulmonary function in NY1DD mice. Data were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA with Neuman-Keuls posttesting. P < .05, +NY1DD vs C57BL/6; *Different from NY1DD controls; # > anti-CD1d alone.

Table 3.

The effects of ATL146e and anti-CD1d on pulmonary leukocyte numbers are not additive

| Cells (105) | (a) NY1DD (n = 17) | (b) NY1DD ATL146e (n = 8) | (c) NY1DD anti-CD1d (n = 10) | (d) NY1DD ATL146e anti-CD1d (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iNKT | 0.43 (0.03) | 0.30 (0.03)* | 0.20 (0.05)* | 0.16 (0.05)** |

| NK | 4.45 (0.77) | 1.21 (0.30)* | 1.51 (0.22)* | 0.90 (0.08)** |

| CD4 | 3.12 (0.37) | 1.00 (0.20)* | 1.04 (0.21)* | 1.20 (0.30)** |

| CD8 | 2.33 (0.32) | 1.00 (0.15)* | 0.66 (0.18)* | 0.73 (0.23)** |

| PMNs | 2.14 (0.31) | 0.38 (0.09)* | 0.84 (0.12)* | 0.52 (0.13)** |

NY1DD mice were treated with either ATL146e (10 ng/kg/minute, 3 days), anti-CD1d (10 μg/g/day, 2 days), or a combination of both. All treatments resulted in significantly decreased pulmonary leukocytes. Data represents the mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA with Neuman-Keuls posttesting.

P < .05 vs a.

P < .05 vs a, not significantly different from b or c.

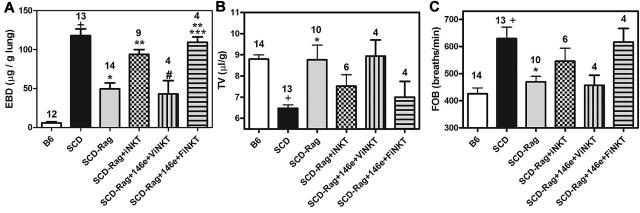

To further investigate the importance of A2ARs on iNKT cells in SCD, we crossed NY1DD with Rag1−/− mice lacking mature lymphocytes. This eliminated iNKT cells and reduced pulmonary injury. We were able to largely restore pulmonary injury within 24 hours after adoptive transfer of iNKT cells. Some of the iNKT cells slated for adoptive transfer were treated in vitro for 1 hour with the selective A2AR alkylating agent, FSPTP, and then washed before transfer. Treatment of recipient mice with ATL146e before adoptive transfer of vehicle-treated iNKT cells reduced pulmonary inflammation and injury (Figure 8; Table 4). However, adoptive transfer of FSPTP-treated iNKT cells caused pulmonary dysfunction that was not prevented by ATL146e. These findings are consistent with a predominant role for A2ARs on iNKT cells in lung protection.

Figure 8.

ATL146e targets A2ARs on iNKT cells to decrease pulmonary inflammation. NY1DD x Rag1−/− mice were pretreated with ATL146e (10 ng/kg/minute, 3 days). Two days later, 106 NKT cells pretreated in vitro with vehicle or 200nM concentrations of the A2AR alkylating agent, FSPTP, were adoptively transferred. Pulmonary parameters were analyzed on day 3 by 1-way ANOVA with Neuman-Keuls posttesting. P < .05: + vs B6; * vs SCD; ** vs SCD - Rag1; # vs SCD-Rag1 + NKT cells; *** vs ATL146e pretreated SCD x Rag1 + NKT cells. B6 = C57BL6; SCD = NY1DD; ViNKT = vehicle-treated iNKT cells; FiNKT = FSPTP-treated iNKT cells.

Table 4.

Pretreatment with ATL146e prevents pulmonary dysfunction in NY1DD-Rag1−/− mice after the adoptive transfer of vehicle-treated but not FSPTP-pretreated NKT cells

| Cells (105) | (a) NY1DD (n = 8) | (b) NY1DD-Rag1−/− (n = 8) | (c) NY1DD-Rag1−/− + NKT cells (n = 4) | (d) NY1DD-Rag1−/− + ATL146e + NKT cells (n = 4) | (e) NY1DD-Rag1−/− + ATL146e + SPTP NKT cells (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NK | 4.30 (0.85) | 6.71 (1.28)* | 12.32 (1.03)*,** | 2.80 (1.00)*** | 2.63 (0.77)*** |

| PMNs | 2.34 (0.40) | 1.63 (0.46) | 6.64 (1.90)*,** | 1.23 (0.58)*** | 6.85 (1.34)*,# |

| iNKT | 0.37 (0.06) | n/a | 0.46 (0.12) | 0.15 (0.04) | 0.63 (0.16)# |

NY1DD × Rag1−/− mice were pre-treated with ATL146e (10 ng/kg/minute, 3 days). On day 2, 106 NKT cells pretreated in vitro with vehicle or FSPTP were adoptively transferred. On day 3, pulmonary leukocytes were analyzed by FACS. Data are means ± SEM and were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA with Neuman-Keuls posttesting.

P < .05 vs a.

P < .05 vs b.

P < .05 vs c.

P < .05 vs d.

Discussion

Treatment strategies for sickle cell disease patients are currently limited to prophylactic use of antibiotics to prevent infections, transfusion therapy, pain management, and hydroxyurea, which stimulates the production of fetal Hb. The beneficial effects of hydroxyura are limited,35 and it inhibits ribonucleotide reductase that is required for DNA synthesis and repair. This has raised concerns that long-term treatment may be carcinogenic or leukemogenic. Such adverse effects have already been noted in patients treated with hydroxyurea for polycythemia vera.36 Although current treatments have increased the lifespan of patients with SCD, morbidity and mortality remain high, and most patients die prematurely. There is an urgent need for improved treatments. The results of this study provide the basis for a new approach for treating SCD. We have previously shown that iNKT cells are critically important for maintaining an inflammatory cascade in SCD mice and probably in patients, and that activation of A2ARs powerfully inhibits iNKT cell activation.28 Here we demonstrate that A2ARs are induced on iNKT and NK cells of NY1DD mice and that A2A agonsits dramatically reduce pulmonary injury in SCD at baseline and after H-R.

Several lines of evidence suggest that iNKT cells are the principal mediators of pulmonary protection in response to ATL146e. Treatment of NY1DD mice with an A2A agonist and anti-CD1d antibodies does not produce additive lung protection. Furthermore, the alkylation of A2ARs on iNKT cells before their adoptive transfer eliminates protection of the recipient mice by ATL146e. These findings indicate that, although they represent only a minor subset of the total lymphocyte population, iNKT cells play a pivotal role in evoking sustained pulmonary pathophysiology in a mouse model of SCD, and inhibition of iNKT cells via activation of the A2AR is beneficial for decreasing pulmonary dysfunction in SCD.

It is notable that A2AR deletion did not markedly worsen pulmonary function or inflammation in SCD mice. This suggests that iNKT cells are not exposed to high levels of endogenous adenosine in SCD. If they were, this adenosine would be expected to activate protective A2ARs, and injury would worsen upon receptor deletion. One explanation for these findings is that iNKT cells are located in a compartment where endogenous levels of adenosine are low due to its normal rapid metabolism, for example in blood.37 Tovocic et al38 have found that red cell hemolysis associated with pulmonary hypertension results in the release of adenosine deaminase that reduces adenosine in plasma. A similar process likely occurs in SCD. It is likely also that adenosine kinase, another cytosolic enzyme involved in adenosine metabolism, also is released from RBCs, liver cells and endothelial cells that lyse as a consequence of SCD. However, cell lysis can increase adenosine by releasing large quantities of adenine nucleotides that are rapidly converted to adensine in the extracellular space. Also, hypoxia due to vaso-occlusion is known to enhance tissue adenosine. Hence, adenosine levels may depend on the severity of disease in an individual person or animal and vary among tissues. Although A2AR activation is anti-inflammatory, the accumulation of high levels of adenosine is not always beneficial. High levels of adenosine contribute to priapism that is common in sickle cell disease, and enhance erythrocyte 2,3-diphosphoglycerate production that may exacerbate sickling. These effects are due to activation of adenosine A2B receptors.39,40 Thus, for reducing vasculopathies in SCD, selective A2AR agonsits may be preferable to adenosine per se, or agents that interfere with adenosine metabolism.

Several murine models of SCD have been developed. In this study we used the well-characterized NY1DD model that expresses 75% human βS-globin and 56% human α-globin.13 Although these mice have been previously described as having a relatively mild hematologic pathology (ie, they have a normal hematocrit), they have been shown to exhibit baseline organ damage to lung, liver, spleen, and kidney.13 In patients, baseline SCD also results in various degrees of baseline organ dysfunction that is often punctuated by periodic exacerbations referred to as sickle “crises.” Pulmonary involvement can lead to life-threatening acute chest syndrome. Baseline pulmonary disease that is apparent in the NY1DD mice is also seen is some patients who require oxygen at baseline. Disease exacerbation is produced in mice exposed to endotoxin or transient hypoxia.14,40 Some SCD patients have increased pulmonary artery pressures that are a risk factor for the development chronic lung disease.41–43 In the current study we chose to study A2AR activation in SCD at baseline and after H-R induced crisis. A2A agonist treatment improved pulmonary function in both cases.

At baseline NY1DD mice display substantial pulmonary inflammation and pathophysiology that is manifested by increased numbers of pulmonary leukocytes, impaired endothelial integrity (increased vascular permeability), and decreased TV. Treatment with ATL146e produced a remarkably rapid (3-day) reversal of baseline pulmonary injury. Histologic examination of lungs from NY1DD animals revealed alveolar thickening that was also rapidly reversed by ATL146e therapy. Pulmonary capillary congestion has also been noted in postmortem patient autopsies.44 We found that ATL14e treatment reversed the significant decrease in arterial oxygen saturation observed in NY1DD mice. Furthermore, in NY1DD mice exposed to hypoxia-reoxygenation as a model acute chest syndrome, ATL146e treatment given after the start reoxygenation decreased pulmonary injury, suggesting that A2A agonists may be useful for the treatment of acute chest syndrome.

Recent studies indicate that iNKT cells are activated by IRI.28,29 One possible route of iNKT cell activation is through self-lipid presentation to invariant TCRs on iNKT cells. The identification of putative endogenous lipid(s) that may be responsible for iNKT activation has been controversial. In 2000, Gumperz et al demonstrated that self-lipids could stimulate iNKT cells, and in 2004 Zhou et al suggested that isoglobotrihexosylceramide (iGb3) was a self-lipid that mediates iNKT activation.45,46 However, subsequent studies demonstrated that iGb3 is not an endogenous ligand and other endogenous ligand(s) have yet to be identified.47,48 In addition to lipid antigens, iNKT cell activation also is regulated by cytokine stimulation. In certain instances it has been shown that IL-12 in combination with IL-18 is sufficient to cause iNKT cell activation.49 These findings suggest either that there are endogenous CD1d-restricted ligands that activate iNKT cells in SCD, or that the TCR on iNKT cells exhibits constitutive activity that is amplified by cytokines generated as a consequence of RBC sickling. Regardless of the mechanisms of iNKT cell activation in SCD, the data are consistent with iNKT cells playing a critical role in propagating pulmonary injury.

Although our results suggest that A2A agonists may be useful to reduce inflammation in SCD, other approaches for reducing inflammation have recently been suggested. Abnormal nitric oxide-dependent regulation of vascular tone, adhesion, platelet activation, and inflammation are believed to contribute to the pathophysiology of vaso-occlusion.50 Furthermore, treatment of SCD patients with inhaled nitric oxide (NO) gas has been shown, via its vasodilatory effects, to improve pulmonary ventilation-perfusion mismatch and hemodynamics, thereby increasing arterial oxygen tension and decreasing inflammation.51,52 However, the clinical utility of increasing NO bioavaialbity has recently been called into question.53 It will be of interest in future studies to evaluate the effectiveness of combinations of anti-inflammatory interventions, including A2A agonsits, NO, and others.

In conclusion, our results suggest A2AR activation as a new strategy for the treatment of pulmonary inflammation and vaso-occlusion in SCD. Lung iNKT cells are activated in the NY1DD mice and trigger an inflammatory cascade with leukocyte recruitment, increased vascular permeability, decreased arterial oxygen saturation, and abnormal breathing parameters. SCD pulmonary iNKT and cells have increased expression of the A2AR, which renders these cells highly sensitive to A2A stimulation. By inhibiting the activation of iNKT cells and other leukocytes with A2AR agonists, it may be possible to reduce vaso-occlusion and tissue damage associated with baseline sickle cell disease and acute exacerbations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Robert Hebbel of the University of Minnesota for his gift of NY1DD mice, Mitch Kronenberg of the La Jolla Institute of Allergy and Immunity for providing an anti-CD1d hybridoma, and PGxHealth for providing ATL146e. We thank Vanessa Hejus for mouse breeding, Melissa A. Marshall and Heidi Figler for technical assistance, and Susan Ramos for Histology. We thank the University of Virginia Flow Cytometry Core for providing help with FACS analysis, the University of Virginia Lymphocyte Culture Core for antibody production and purification, and the National Institutes of Health Tetramer facility at Emory University for their gifts of loaded and unloaded CD1d tetramers.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants P01 HL073361 and R01HL095704.

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: K.L.W. performed and analyzed all experiments and prepared the manuscript, and J.L. provided experimental design and manuscript editing.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.L. is a paid consultant to PGxHealth, a subsidiary of Clinical Data Inc, the owner of ATL146e. The authors declare no other competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Joel Linden, La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology, 9420 Athena Cir, Rm 1200, La Jolla, CA, 92037; e-mail: jlinden@liai.org.

References

- 1.Wallace KL, Marshall MA, Ramos SI, et al. NKT cells mediate pulmonary inflammation and dysfunction in murine sickle cell disease through production of IFN-gamma and CXCR3 chemokines. Blood. 2009;114(3):667–676. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-205492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belcher JD, Bryant CJ, Nguyen J, et al. Transgenic sickle mice have vascular inflammation. Blood. 2003;101(10):3953–3959. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaul DK, Hebbel RP. Hypoxia/reoxygenation causes inflammatory response in transgenic sickle mice but not in normal mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(3):411–420. doi: 10.1172/JCI9225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsu LL, Champion HC, Campbell-Lee SA, et al. Hemolysis in sickle cell mice causes pulmonary hypertension due to global impairment in nitric oxide bioavailability. Blood. 2007;109(7):3088–3098. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-039438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osarogiagbon UR, Choong S, Belcher JD, Vercellotti GM, Paller MS, Hebbel RP. Reperfusion injury pathophysiology in sickle transgenic mice. Blood. 2000;96(1):314–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aslan M, Ryan TM, Adler B, et al. Oxygen radical inhibition of nitric oxide-dependent vascular function in sickle cell disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(26):15215–15220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221292098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dias-Da-Motta P, Arruda VR, Muscara MN, et al. The release of nitric oxide and superoxide anion by neutrophils and mononuclear cells from patients with sickle cell anaemia. Br J Haematol. 1996;93(2):333–340. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.4951036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hebbel RP, Eaton JW, Balasingam M, Steinberg MH. Spontaneous oxygen radical generation by sickle erythrocytes. J Clin Invest. 1982;70(6):1253–1259. doi: 10.1172/JCI110724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turhan A, Weiss LA, Mohandas N, Coller BS, Frenette PS. Primary role for adherent leukocytes in sickle cell vascular occlusion: a new paradigm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(5):3047–3051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052522799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF, et al. Mortality in sickle cell disease. Life expectancy and risk factors for early death. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(23):1639–1644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray A, Anionwu EN, Davies SC, Brozovic M. Patterns of mortality in sickle cell disease in the United Kingdom. J Clin Pathol. 1991;44(6):459–463. doi: 10.1136/jcp.44.6.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minter KR, Gladwin MT. Pulmonary complications of sickle cell anemia. A need for increased recognition, treatment, and research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(11):2016–2019. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.11.2104101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fabry ME, Costantini F, Pachnis A, et al. High expression of human beta S- and alpha-globins in transgenic mice: erythrocyte abnormalities, organ damage, and the effect of hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(24):12155–12159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fabry ME, Nagel RL, Pachnis A, Suzuka SM, Costantini F. High expression of human beta S- and alpha-globins in transgenic mice: hemoglobin composition and hematological consequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(24):12150–12154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofstra TC, Kalra VK, Meiselman HJ, Coates TD. Sickle erythrocytes adhere to polymorphonuclear neutrophils and activate the neutrophil respiratory burst. Blood. 1996;87(10):4440–4447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Platt OS. Sickle cell anemia as an inflammatory disease. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(3):337–338. doi: 10.1172/JCI10726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonneau O, Wyss D, Ferretti S, Blaydon C, Stevenson CS, Trifilieff A. Effect of adenosine A2A receptor activation in murine models of respiratory disorders. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290(5):L1036–1043. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00422.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fozard JR, Ellis KM, Villela Dantas MF, Tigani B, Mazzoni L. Effects of CGS 21680, a selective adenosine A2A receptor agonist, on allergic airways inflammation in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;438(3):183–188. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01305-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadeem A, Fan M, Ansari HR, Ledent C, Jamal Mustafa S. Enhanced airway reactivity and inflammation in A2A adenosine receptor-deficient allergic mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292(6):L1335–1344. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00416.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reutershan J, Cagnina RE, Chang D, Linden J, Ley K. Therapeutic anti-inflammatory effects of myeloid cell adenosine receptor A2a stimulation in lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury. J Immunol. 2007;179(2):1254–1263. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harada N, Okajima K, Murakami K, et al. Adenosine and selective A(2A) receptor agonists reduce ischemia/reperfusion injury of rat liver mainly by inhibiting leukocyte activation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294(3):1034–1042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jordan JE, Zhao ZQ, Sato H, Taft S, Vinten-Johansen J. Adenosine A2 receptor activation attenuates reperfusion injury by inhibiting neutrophil accumulation, superoxide generation and coronary endothelial adherence. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280(1):301–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okusa MD, Linden J, Huang L, Rieger JM, Macdonald TL, Huynh LP. A(2A) adenosine receptor-mediated inhibition of renal injury and neutrophil adhesion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;279(5):F809–818. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.279.5.F809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross SD, Tribble CG, Linden J, et al. Selective adenosine-A2A activation reduces lung reperfusion injury following transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1999;18(10):994–1002. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(99)00066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thiel M, Caldwell CC, Sitkovsky MV. The critical role of adenosine A2A receptors in downregulation of inflammation and immunity in the pathogenesis of infectious diseases. Microbes Infect. 2003;5(6):515–526. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gessi S, Varani K, Merighi S, Ongini E, Borea PA. A(2A) adenosine receptors in human peripheral blood cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129(1):2–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lukashev D, Ohta A, Sitkovsky M. Targeting hypoxia–A(2A) adenosine receptor-mediated mechanisms of tissue protection. Drug Discov Today. 2004;9(9):403–409. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lappas CM, Day YJ, Marshall MA, Engelhard VH, Linden J. Adenosine A2A receptor activation reduces hepatic ischemia reperfusion injury by inhibiting CD1d-dependent NKT cell activation. J Exp Med. 2006;203(12):2639–2648. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, Huang L, Sung SS, et al. NKT cell activation mediates neutrophil IFN-gamma production and renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Immunol. 2007;178(9):5899–5911. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang E, Ouellet N, Simard M, et al. Pulmonary and systemic host response to Streptococcus pneumoniae and Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia in normal and immunosuppressed mice. Infect Immun. 2001;69(9):5294–5304. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5294-5304.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shryock JC, Snowdy S, Baraldi PG, et al. A2A-adenosine receptor reserve for coronary vasodilation. Circulation. 1998;98(7):711–718. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.7.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Day YJ, Huang L, McDuffie MJ, et al. Renal protection from ischemia mediated by A2A adenosine receptors on bone marrow-derived cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(6):883–891. doi: 10.1172/JCI15483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Day YJ, Marshall MA, Huang L, McDuffie MJ, Okusa MD, Linden J. Protection from ischemic liver injury by activation of A2A adenosine receptors during reperfusion: inhibition of chemokine induction. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286(2):G285–293. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00348.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Z, Day YJ, Toufektsian MC, et al. Myocardial infarct-sparing effect of adenosine A2A receptor activation is due to its action on CD4+ T lymphocytes. Circulation. 2006;114(19):2056–2064. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.649244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Charache S, Terrin ML, Moore RD, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in sickle cell anemia. Investigators of the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(20):1317–1322. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dalton RN, Wiseman MJ, Turner C, Viberti G. Measurement of urinary para-aminohippuric acid in glycosuric diabetics. Kidney Int. 1988;34(1):117–120. doi: 10.1038/ki.1988.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moser GH, Schrader J, Deussen A. Turnover of adenosine in plasma of human and dog blood. Am J Physiol. 1989;256(4 Pt 1):C799–806. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.256.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tofovic SP, Jackson EK, Rafikova O. Adenosine deaminase-adenosine pathway in hemolysis-associated pulmonary hypertension. Med Hypotheses. 2009;72(6):713–719. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang YJ, Dai YB, Wen JM, et al. Detrimental role of excess adenosine-mediated 2,3-diphosphoglycerate induction in erythrocyte sickling and novel mechanism-based therapies. Blood. 2009;114(22):373–374. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holtzclaw JD, Jack D, Aguayo SM, Eckman JR, Roman J, Hsu LL. Enhanced pulmonary and systemic response to endotoxin in transgenic sickle mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(6):687–695. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200302-224OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gladwin MT, Sachdev V, Jison ML, et al. Pulmonary hypertension as a risk factor for death in patients with sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(9):886–895. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ataga KI, Moore CG, Jones S, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in patients with sickle cell disease: a longitudinal study. Br J Haematol. 2006;134(1):109–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Castro LM, Jonassaint JC, Graham FL, Ashley-Koch A, Telen MJ. Pulmonary hypertension associated with sickle cell disease: clinical and laboratory endpoints and disease outcomes. Am J Hematol. 2008;83(1):19–25. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haque AK, Gokhale S, Rampy BA, Adegboyega P, Duarte A, Saldana MJ. Pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell hemoglobinopathy: a clinicopathologic study of 20 cases. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(10):1037–1043. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.128059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gumperz JE, Roy C, Makowska A, et al. Murine CD1d-restricted T cell recognition of cellular lipids. Immunity. 2000;12(2):211–221. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou D, Mattner J, Cantu C, 3rd, et al. Lysosomal glycosphingolipid recognition by NKT cells. Science. 2004;306(5702):1786–1789. doi: 10.1126/science.1103440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Porubsky S, Speak AO, Luckow B, Cerundolo V, Platt FM, Grone HJ. Normal development and function of invariant natural killer T cells in mice with isoglobotrihexosylceramide (iGb3) deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(14):5977–5982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611139104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Christiansen D, Milland J, Mouhtouris E, et al. Humans lack iGb3 due to the absence of functional iGb3-synthase: implications for NKT cell development and transplantation. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(7):e172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nagarajan NA, Kronenberg M. Invariant NKT cells amplify the innate immune response to lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2007;178(5):2706–2713. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weiner DL, Hibberd PL, Betit P, Cooper AB, Botelho CA, Brugnara C. Preliminary assessment of inhaled nitric oxide for acute vaso-occlusive crisis in pediatric patients with sickle cell disease. JAMA. 2003;289(9):1136–1142. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Atz AM, Wessel DL. Inhaled nitric oxide in sickle cell disease with acute chest syndrome. Anesthesiology. 1997;87(4):988–990. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199710000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sullivan KJ, Goodwin SR, Evangelist J, Moore RD, Mehta P. Nitric oxide successfully used to treat acute chest syndrome of sickle cell disease in a young adolescent. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(11):2563–2568. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199911000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bunn HF, Nathan DG, Dover GJ, et al. Pulmonary hypertension and nitric oxide depletion in sickle cell disease. Blood. 2010;116(5):687–692. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-268193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]