Abstract

Because tuberculous (TB) involvement of mediastinal lymph nodes (LN) could cause false positive results in nodal staging of lung cancer, we examined the accuracy of nodal staging in lung cancer patients with radiographic sequelae of healed TB. A total of 54 lung cancer patients with radiographic TB sequelae in the lung parenchyma ipsilateral to the resected lung, who had undergone at least ipsilateral 4- and 7-lymph node dissection after both chest computed tomography (CT) and fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/CT were included for the analysis. The median age of 54 subjects was 66 yr and 48 were males. Calcified nodules and fibrotic changes were the most common forms of healed parenchymal pulmonary TB. Enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes (short diameter > 1 cm) were identified in 21 patients and positive mediastinal lymph nodes were identified using FDG-PET/CT in 19 patients. The overall sensitivity and specificity for mediastinal node metastasis were 60.0% and 69.2% with CT and 46.7% and 69.2% with FDG-PET/CT, respectively. In conclusion, the accuracy of nodal staging using CT or FDG-PET/CT might be low in lung cancer patients with parenchymal TB sequelae, because of inactive TB lymph nodes without viable TB bacilli.

Keywords: Latent Tuberculosis, Lung Neoplasms, Mediastinum, Tuberculosis, Lymph Node

INTRODUCTION

Accurate nodal staging of lung cancer is crucial for deciding the optimal treatment, because patients with mediastinal lymph node metastases are generally offered chemotherapy rather than surgery (1). If enlarged lymph nodes or hot uptake on fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) are observed in patients diagnosed with lung cancer, metastases to the lymph nodes should be suspected.

However, mediastinal lymph nodes are one of the main sites of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in latent tuberculosis (TB) infection (2). The involvement of lymph nodes in TB also causes increased lymph node size (3) because of the accumulation of stimulated phagocytes caused by surviving mycobacteria and the fusion of phagosomal compartments, with possible fibrotic changes (4). TB also causes hot uptake on FDG-PET because glucose metabolism is increased with the accumulation of FDG in the inflammatory phagocytes and macrophages in the granulation tissue (5). Thus, TB involvement of mediastinal lymph nodes could cause false-positive nodal staging, especially in patients with evidence of previous TB. In this study, we examined the accuracy of nodal staging in lung cancer patients with radiographic sequelae of healed TB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The subjects screened for this study were patients who had undergone surgical lung resection with lymph node dissection for the treatment of primary or metastatic lung cancer between January 2004 and December 2006 at the Seoul National University Hospital, a university-affiliated tertiary referral hospital. Among them, patients with radiographic TB sequelae ipsilateral to the resected lung were screened for the analysis. If fibrotic bands, small calcified nodules, or bronchiectasis in the upper lobes were observed on chest CT preoperatively, the patients were regarded as having healed TB (6, 7). Patients who underwent both chest CT and FDG-PET/CT before surgical resection and who underwent at least ipsilateral 4- and 7-lymph node dissection during the operation were finally included in the study.

Medical records were reviewed, including the pathology results and radiographic examinations. On CT, mediastinal lymph node enlargement was defined as the presence of lymph nodes larger than 1 cm in their smallest diameter (7, 8). On FDG-PET/CT, mediastinal nodes with increased glucose uptake satisfying both qualitative (greater than that of the surrounding tissue) and quantitative (a maximum standardized uptake value [SUV] adjusted for patient body weight of ≥ 3.0 with a distinct margin) criteria were considered positive (9, 10).

Diagnosis of mediastinal tuberculous lymphadenitis

The histology of the dissected lymph nodes stained with hematoxylin and eosin was reviewed. The presence of granulomas, with or without caseating necrosis, was confirmed. Additionally, the results of acid-fast staining or the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for M. tuberculosis DNA were also screened when available. If acid-fast bacilli were seen in the specimen or PCR for M. tuberculosis DNA was positive, a definite diagnosis of TB lymphadenitis was made. If only a caseating granuloma was identified, we classified the specimen as probable TB lymphadenitis. We also classified patients who had granulomas with non-specific necrosis as suspicious cases of TB lymphadenitis.

Diagnosis of mediastinal lymph node metastasis

During surgical resection, encountered lymph nodes were removed from American Thoracic Society (ATS) lymph-node stations 10R, 9, 8, 7, 4R, 3, and 2R in tumors of the right lung and from stations 10L, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, and 4L of the left lung (11). When necessary, station 1 (the highest mediastinal) or 2L (when tumors were located in the left lung) nodes were also evaluated during the procedure. An experienced lung pathologist described the location and number of lymph nodes according to the surgeons' labeling of the dissected lymph nodes. Then, the pathologist evaluated the nodes for the presence or absence of tumor as numbered in the surgical field and reported the presence or absence of tumor in the nodes. Specimens were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and then examined by light microscopy.

Ethics statement

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the Seoul National University Hospital (H-0710-003-221). Informed consent was waived in this study by the board.

RESULTS

During the study period, 796 patients with lung cancer underwent surgical resection. Of these, 84 patients had radiographic TB sequelae ipsilateral to the resected lung. Among this latter group, the analysis included 54 patients for whom chest CT and FDG-PET/CT were available and the lymph node dissection included at least 4- and 7-lymph node sites.

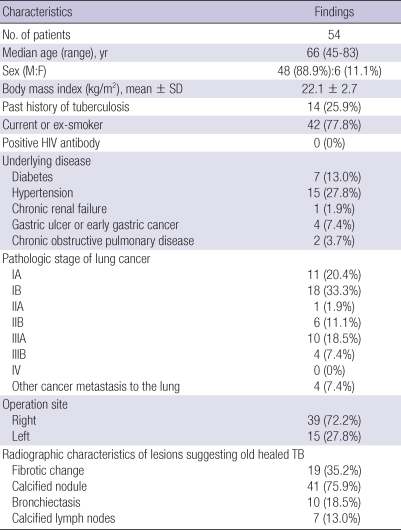

Of the 54 patients, 48 (88.9%) were males. Their median age was 66 (range 45-83) yr. Their mean body mass index was 22.1 ± 2.7 kg/m2. No patient was anti-HIV antibody seropositive. Fourteen patients (25.9%) had a history of pulmonary TB and 42 patients (77.8%) were current or ex-smokers (Table 1). The most common pathological stage of the lung cancer was IB (18 patients, 33.3%). Mediastinal lymph node enlargement, larger than 1 cm in the smallest diameter on CT, was observed in 21 patients (32.3%) and metastatic mediastinal lymph nodes were suggested by FDG PET/CT in 19 patients (29.2%).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of lung cancer patients with TB sequelae in the ipsilateral lung who underwent surgery with lymph node dissection

As seen in Table 1, calcified nodules (75.9%) and fibrotic changes (35.2%) were the most common forms of parenchymal lesions, and bronchiectatic changes in the upper lobes were found in ten patients (18.5%). Using the above-mentioned criteria, lymph node enlargement was found in 21 patients and calcified lymph nodes were seen in seven.

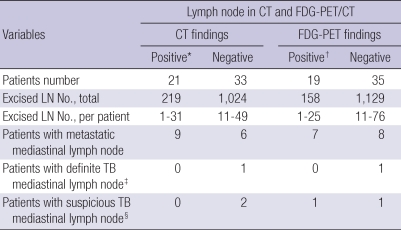

The median number of dissected lymph nodes per patient was 32 (range, 1-76). Of the 21 patients with enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes on CT, nine were confirmed to have mediastinal lymph node metastasis. In contrast, six of the 33 patients with negative CT findings were confirmed to have mediastinal lymph node metastasis; one of these patients was confirmed to have TB lymphadenitis, based on the presence of acid-fast bacilli. Of the 19 patients with positive mediastinal lymph nodes by FDG PET/CT, seven were confirmed to have mediastinal lymph node metastasis. Eight of the 35 patients with a negative FDG-PET/CT were confirmed to have mediastinal lymph node metastasis; one of these patients was confirmed to have TB lymphadenitis by the presence of acid-fast bacilli.

On a per-person basis, the overall sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value for mediastinal nodal metastasis were 60.0%, 69.2%, 66.7%, 42.9%, and 81.8% for CT and 46.7%, 69.2%, 63.0%, 36.8%, and 77.1% for FDG-PET/CT, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pathological diagnosis of the dissected lymph nodes with positive findings on CT and FDG-PET/CT among patients who had undergone both CT and FDG-PET/CT

*The presence of lymph nodes ≥ 1 cm in their smallest diameter was considered to be positive on CT; †The presence of lymph nodes with a maximum SUV ≥ 3.0 was considered to be positive on FDG-PET/CT; ‡Granulomas and acid-fast bacilli were observed on microscopic evaluation in one patient only; §Only granulomas were observed on microscopic evaluation in two patients. CT, computed tomography; FDG-PET, fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography; LN, lymph node; SUV, standardized uptake value; TB, tuberculosis.

DISCUSSION

Our study involving lung cancer patients with TB sequelae showed that the accuracy of mediastinal staging using CT and FDG-PET/CT was low (66.7% and 63.0%), compared with previous reports from Korea (83.0% and 90.0%) (12). Especially, the specificity of mediastinal nodal staging using CT and FDG-PET/CT for nodal metastasis was considerably lower in our study (69.2% for both tests), compared to 89% and 100% in a previous report for Korea (12), and 93% and 98% in a report for low TB burden country (13).

Although definite TB involvement was identified only in one patient and suspicious TB in two patients, the lower specificity for nodal metastasis in our study could be explained by TB involvement. In patients with previous TB, mediastinal lymph node enlargement might represent inflammation of previously normal nodes draining areas of active TB in the lungs to other sites. These lymph nodes were defined as inactive TB lymphadenopathy (7). In previous reports, live TB bacilli could not be cultivated from the majority of inactive TB lesions (15). In fact, according to a previous report, as many as 77% of 78 lung cancer patients with calcified mediastinal lymph nodes were confirmed not to have cancer metastasis or definite TB lymphadenitis (14). Therefore, we can consider preoperative surgical staging to mediastinal lymph nodes in lung cancer patients with parenchymal TB sequelae, even though they have positive mediastinal lymph nodes in the chest CT and/or FDG-PET/CT.

Because only one of the 54 patients with radiographic TB sequelae was diagnosed as having definite mediastinal TB lymphadenitis, it is possible that mediastinal lymph nodes are rarely a focus of latent TB infection, contrary to the general assumption. That is, this observation indicates that mediastinal lymph nodes are not likely a focus of TB reactivation in patients with healed TB who belong to the supposed high-risk group for reactivation of TB (16).

Our data differ from a report from Turkey, which showed a 5.1% prevalence of mediastinal TB among lung cancer patients regardless of previous TB sequelae shown on chest radiographs (17). Although the reason for the difference between the two studies is unclear, the fact that a considerable portion of our patients (26%) had been treated for pulmonary TB could result in the lower prevalence of the presence of TB bacilli in our study.

To appreciate our results correctly, we should consider several limitations of the study that might have underestimated the actual prevalence of mediastinal TB. First, not all mediastinal lymph nodes were resected and reviewed because this study was performed retrospectively. Additionally, acid-fast staining and PCR for M. tuberculosis DNA without mycobacterial culture for the diagnosis of TB might be insufficient for detecting the presence of mediastinal TB. Thus, the prevalence of mediastinal TB could have been underestimated. A well-designed prospective study is needed to determine the actual prevalence of mediastinal TB in patients with radiographic sequelae of healed TB.

In conclusion, the accuracy of nodal staging using CT or FDG-PET/CT is low in lung cancer patients with parenchymal TB sequelae, because of inactive TB lymph nodes without viable TB bacilli.

AUTHOR SUMMARY

Impact of Parenchymal Tuberculosis Sequelae on Mediastinal Lymph Node Staging in Patients with Lung Cancer

Seung Heon Lee, Joo-Won Min, Chang Hoon Lee, Chang Min Park, Jin Mo Goo, Doo Hyun Chung, Chang Hyun Kang, Young Tae Kim, Young Whan Kim, Sung Koo Han, Young-Soo Shim, and Jae-Joon Yim

Because tuberculous (TB) involvement of mediastinal lymph nodes (LN) could cause false positive results in nodal staging of lung cancer, we examined the accuracy of nodal staging in lung cancer patients with radiographic sequelae of healed TB. For the analysis, we included 54 lung cancer patients with radiographic TB sequelae in the lung parenchyma ipsilateral to the resected lung, who had undergone at least ipsilateral 4- and 7-lymph node dissection after both chest computed tomography (CT) and fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/CT. The overall sensitivity and specificity for mediastinal node metastasis were 60.0% and 69.2% with CT and 46.7% and 69.2% with FDG-PET/CT, respectively. The accuracy of nodal staging using CT or FDG-PET/CT might be low in lung cancer patients with parenchymal TB sequelae, because of inactive TB lymph nodes without viable TB bacilli.

References

- 1.Rena O, Massera F, Robustellini M, Papalia E, Delfanti R, Lisi E, Pirondini E, Turello D, Casadio C. Use of the proposals of the international association for the study of lung cancer in the forthcoming edition of lung cancer staging system to predict long-term prognosis of operated patients. Cancer J. 2010;16:176–181. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181ce474e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amorosa JK, Smith PR, Cohen JR, Ramsey C, Lyons HA. Tuberculous mediastinal lymphadenitis in the adult. Radiology. 1978;126:365–368. doi: 10.1148/126.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyons HA, Calvy GL, Sammons BP. The diagnosis and classification of mediastinal masses. 1. A study of 782 cases. Ann Intern Med. 1959;51:897–932. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-51-5-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moon WK, Im JG, Yu IK, Lee SK, Yeon KM, Han MC. Mediastinal tuberculous lymphadenitis: MR imaging appearance with clinicopathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:21–25. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.1.8571880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubota R, Yamada S, Kubota K, Ishiwata K, Tamahashi N, Ido T. Intratumoral distribution of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose in vivo: high accumulation in macrophages and granulation tissues studied by microautoradiography. J Nucl Med. 1992;33:1972–1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Im JG, Itoh H, Shim YS, Lee JH, Ahn J, Han MC, Noma S. Pulmonary tuberculosis: CT findings--early active disease and sequential change with antituberculous therapy. Radiology. 1993;186:653–660. doi: 10.1148/radiology.186.3.8430169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moon WK, Im JG, Yeon KM, Han MC. Mediastinal tuberculous lymphadenitis: CT findings of active and inactive disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:715–718. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.3.9490959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiyono K, Sone S, Sakai F, Imai Y, Watanabe T, Izuno I, Oguchi M, Kawai T, Shigematsu H, Watanabe M. The number and size of normal mediastinal lymph nodes: a postmortem study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;150:771–776. doi: 10.2214/ajr.150.4.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowe VJ, Duhaylongsod FG, Patz EF, Delong DM, Hoffman JM, Wolfe WG, Coleman RE. Pulmonary abnormalities and PET data analysis: a retrospective study. Radiology. 1997;202:435–439. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.2.9015070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yi CA, Lee KS, Kim BT, Choi JY, Kwon OJ, Kim H, Shim YM, Chung MJ. Tissue characterization of solitary pulmonary nodule: comparative study between helical dynamic CT and integrated PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:443–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mountain CF, Dresler CM. Regional lymph node classification for lung cancer staging. Chest. 1997;111:1718–1723. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.6.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yi CA, Lee KS, Kim BT, Shim SS, Chung MJ, Sung YM, Jeong SY. Efficacy of helical dynamic CT versus integrated PET/CT for detection of mediastinal nodal metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:318–325. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marom EM, McAdams HP, Erasmus JJ, Goodman PC, Culhane DK, Coleman RE, Herndon LE, Patz EF., Jr Staging non-small cell lung cancer with whole-body PET. Radiology. 1999;212:803–809. doi: 10.1148/radiology.212.3.r99se21803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim YK, Lee KS, Kim BT, Choi JY, Kim H, Kwon OJ, Shim YM, Yi CA, Kim HY, Chung MJ. Mediastinal nodal staging of nonsmall cell lung cancer using integrated 18F-FDG PET/CT in a tuberculosis-endemic country: diagnostic efficacy in 674 patients. Cancer. 2007;109:1068–1077. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canetti G, Sutherland I, Svandova E. Endogenous reactivation and exogenous reinfection: their relative importance with regard to the development of non-primary tuberculosis. Bull Int Union Tuberc. 1972;47:116–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horsburgh CR., Jr Priorities for the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2060–2067. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa031667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solak O, Sayar A, Metin M, Erdoğu V, Cuhadaroğlu S, Turna A, Gürses A. The coincidence of mediastinal tuberculosis lymphadenitis in lung cancer patients. Acta Chir Belg. 2005;105:180–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]