Abstract

To determine the importance of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species toxicity in aging and senescence, we analyzed changes in mitochondrial function with age in mice with partial or complete deficiencies in the mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD). Liver mitochondria from homozygous mutant mice, with a complete deficiency in MnSOD, exhibited substantial respiration inhibition and marked sensitization of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Mitochondria from heterozygous mice, with a partial deficiency in MnSOD, showed evidence of increased proton leak, inhibition of respiration, and early and rapid accumulation of mitochondrial oxidative damage. Furthermore, chronic oxidative stress in the heterozygous mice resulted in an increased sensitization of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and the premature induction of apoptosis, which presumably eliminates the cells with damaged mitochondria. Mice with normal MnSOD levels show the same age-related mitochondrial decline as the heterozygotes but occurring later in life. The premature decline in mitochondrial function in the heterozygote was associated with the compensatory up-regulation of oxidative phosphorylation enzyme activity. Thus mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production, oxidative stress, functional decline, and the initiation of apoptosis appear to be central components of the aging process.

A major component of aging in

mammals is the progressive senescence of postmitotic tissues. Although

many theories of aging have been elaborated over the past 30 yr (1),

one of the most promising is the free radical theory. This theory

contends that senescence is the result of the accumulation of cellular

and tissue damage caused by the reactive oxygen species (ROS):

superoxide anion (O ), hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2), and hydroxyl

radical (⋅OH) (2–7).

), hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2), and hydroxyl

radical (⋅OH) (2–7).

It is now clear that much of the ROS production in mammalian cells is a toxic by-product of the mitochondrial energy production pathway, oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) (2, 8). The mitochondrial production of ROS results in the oxidation of mitochondrial lipids, proteins, and DNA (mtDNA) (9). Because mtDNA diseases are associated with many of the same clinical manifestations that characterize old age (6, 7), there is a growing conviction that the age-related accumulation of mitochondrial damage plays an important role in the physiological decline associated with mammalian aging and senescence.

OXPHOS is composed of five enzyme complexes. Complexes I, II, III, and IV constitute the electron transport chain (ETC), which oxidizes the hydrogen atoms from carbohydrates and fats with atomic oxygen. Electrons are donated to complex I from NADH + H+ or to complex II via succinate and passed to coenzyme Q (CoQ) to give ubisemiquinone (CoQH⋅) and then ubiquinol (CoQH2). Ubiquinol donates its electrons to complex III, which transfers the electrons to cytochrome c. From cytochrome c, the electrons move to complex IV and finally to ½ O2 to give H2O. The energy released by the ETC is used to pump protons across the mitochondrial inner membrane, creating a transmembrane electrochemical gradient, ΔΨ. The potential energy stored in ΔΨ is used by complex V (ATP synthase) to condense ADP and Pi to make ATP. Matrix ATP is then exchanged for cytosolic ADP by the adenine nucleotide translocator. The reduction of oxygen to water is thus coupled to the phosphorylation of ADP via ΔΨ. When exogenous ADP levels are high, ATP is synthesized by complex V at the expense of ΔΨ, and oxygen is consumed by the ETC to restore ΔΨ (state III respiration). However, when ADP levels are limiting, ΔΨ is sustained, the ETC slows, and oxygen consumption is low (state IV respiration). The ratio of state III to state IV respiration is known as the respiratory control ratio (RCR).

Approximately 0.4–4% of the molecular oxygen

(O2) consumed by the mitochondria is reduced by a

single electron transfer from the initial steps of the ETC to form the

highly toxic superoxide anion (O ). The primary

source of electrons to generate O

). The primary

source of electrons to generate O is probably

ubisemiquinone (8, 10). Superoxide anion is converted to hydrogen

peroxide (H2O2) by the

mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD, Sod2). In liver,

mitochondrial H2O2 is then

reduced to water by glutathione peroxidase-1 (Gpx-1). In the presence

of reduced transition metals,

H2O2 can be converted to

the highly toxic hydroxyl radical (⋅OH) via Fenton chemistry

(11). The inhibition of mitochondrial OXPHOS increases the misdirection

of electrons from the ETC into ROS production. Thus, ROS production is

greater during state IV respiration than state III.

is probably

ubisemiquinone (8, 10). Superoxide anion is converted to hydrogen

peroxide (H2O2) by the

mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD, Sod2). In liver,

mitochondrial H2O2 is then

reduced to water by glutathione peroxidase-1 (Gpx-1). In the presence

of reduced transition metals,

H2O2 can be converted to

the highly toxic hydroxyl radical (⋅OH) via Fenton chemistry

(11). The inhibition of mitochondrial OXPHOS increases the misdirection

of electrons from the ETC into ROS production. Thus, ROS production is

greater during state IV respiration than state III.

When the level of ROS exceeds the capacity of the mitochondria and cell to detoxify them, the resulting chronic oxidative stress can activate the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mtPTP) (12). The mtPTP is thought to be composed of the inner membrane adenine nucleotide translocator, the outer membrane voltage-dependent anion channel or porin, Bax, Bcl2, and cyclophilin D. The activation of the mtPTP creates an open channel across the mitochondrial inner and outer membranes, which permits the free diffusion of molecules of less than 1,500 Da between the matrix and the cytosol (13). This results in the collapse of ΔΨ, the loss of matrix solutes, and the swelling of the mitochondria, causing the release of cytochrome c, procaspases 2, 3, and 9, apoptosis-initiating factor, and caspase-activated DNase. Cytochrome c and the cytosolic factor Apaf1 activate the caspases, which degrade cytosolic proteins, while apoptosis-initiating factor and caspase-activated DNase move to the nucleus and degrade the chromatin (14). Thus, the mtPTP regulates programmed cell death or apoptosis.

In addition to oxidative stress, the mtPTP can be activated by decreased mitochondrial ΔΨ, reduced levels of matrix ADP and ATP, and/or the uptake of excessive Ca2+ (15–17). Therefore, decreased mitochondrial energy production and/or increased mitochondrial oxidative stress can initiate apoptosis, resulting in tissue decline and senescence.

The acute toxicity of mitochondrial O has been

illustrated by the lethality of the Sod2 mutation in mice.

Mice deficient in MnSOD (Sod2tm1Cje

−/−) exhibit neonatal lethality in association with dilated

cardiomyopathy and a massive lipid accumulation in the liver (18).

These animals also have dramatic reductions in the activities of the

mitochondrial enzymes that contain iron–sulfur centers, including the

Krebs cycle enzyme aconitase and the ETC enzymes succinate

dehydrogenase (complex II) and NADH dehydrogenase (complex I). These

animals also exhibit a marked increase in DNA oxidation products and

develop a 3-methylglutaconic aciduria (19). The

Sod2tm1Cje (−/−) mouse proves the

importance of mitochondrial O

has been

illustrated by the lethality of the Sod2 mutation in mice.

Mice deficient in MnSOD (Sod2tm1Cje

−/−) exhibit neonatal lethality in association with dilated

cardiomyopathy and a massive lipid accumulation in the liver (18).

These animals also have dramatic reductions in the activities of the

mitochondrial enzymes that contain iron–sulfur centers, including the

Krebs cycle enzyme aconitase and the ETC enzymes succinate

dehydrogenase (complex II) and NADH dehydrogenase (complex I). These

animals also exhibit a marked increase in DNA oxidation products and

develop a 3-methylglutaconic aciduria (19). The

Sod2tm1Cje (−/−) mouse proves the

importance of mitochondrial O in cellular ROS

toxicity because inactivation of the cytosolic (Sod1) (20) or

extracellular (Sod3) (21) Cu/ZnSODs has little effect on animal

viability.

in cellular ROS

toxicity because inactivation of the cytosolic (Sod1) (20) or

extracellular (Sod3) (21) Cu/ZnSODs has little effect on animal

viability.

The effects of chronic superoxide anion exposure can be observed by using the Sod2tm1Cje heterozygote (+/−) animals. Initial studies of 3-mo-old Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mice revealed increased oxidative damage in the form of mtDNA oxidative adducts and reduced activity of the iron–sulfur protein aconitase. Mitochondria isolated from these animals also exhibited reduced RCRs and an increased propensity to undergo the permeability transition when challenged with the oxidant tert-butylhydroperoxide (22).

To better understand the age-related effects of superoxide anion

toxicity on mitochondrial function and tissue integrity, we have

studied the biochemical and molecular changes that occur in homozygous

and heterozygous Sod2tm1Cje-mutant mice.

Acute mitochondrial O toxicity was studied in

neonatal Sod2tm1Cje (−/−) mice and

found to result in the inhibition of respiration and the

hypersensitization of the mtPTP. Chronic mitochondrial

O

toxicity was studied in

neonatal Sod2tm1Cje (−/−) mice and

found to result in the inhibition of respiration and the

hypersensitization of the mtPTP. Chronic mitochondrial

O toxicity was examined in young (5-mo-old),

middle-aged (10- to 14-mo-old), and old (20- to 25-mo-old)

Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mice. The heterozygous

Sod2tm1Cje mice exhibited a decreased

mitochondrial ΔΨ, a decreased state III and increased state IV

respiration rate, and a compensatory up-regulation of OXPHOS enzymes.

Chronic mitochondrial O

toxicity was examined in young (5-mo-old),

middle-aged (10- to 14-mo-old), and old (20- to 25-mo-old)

Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mice. The heterozygous

Sod2tm1Cje mice exhibited a decreased

mitochondrial ΔΨ, a decreased state III and increased state IV

respiration rate, and a compensatory up-regulation of OXPHOS enzymes.

Chronic mitochondrial O toxicity also caused

increased mitochondrial oxidative damage, which led to an increased

predilection for mtPTP transition and a dramatic increase in

apoptosis late in life.

toxicity also caused

increased mitochondrial oxidative damage, which led to an increased

predilection for mtPTP transition and a dramatic increase in

apoptosis late in life.

Materials and Methods

Genotyping and Animal Maintenance.

All mice were on the CD1 background, fed Purina Labdiet 5021, and housed at 20°C with a 12-h light and dark cycle. For biochemical analyses, animals were killed by cervical dislocation in accordance with Emory University's ethical guidelines outlined in an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocol. Newborn pups were genotyped at 7–9 days of age as described.

Tissue Harvesting and Mitochondrial Isolation.

All manipulations were performed at 4°C or on ice. Whole liver was harvested, immersed in isotonic homogenization (H) buffer (225 mM mannitol/75 mM sucrose/10 mM Mops/1 mM EGTA/0.5% BSA, pH 7.2), minced with scissors, and then homogenized with a 15-ml Wheaton Scientific Teflon-to-glass homogenizer. Mitochondria were isolated by differential centrifugation; the mitochondrial pellets were resuspended in 300 μl of H buffer without EGTA, and protein concentration was determined by using the Coomassie stain kit (Pierce).

Western Blot Analysis.

Antibodies to Sod2 were raised against the near N-terminal residues 25–41 (acetyl-KHSLPDLPYDYGALEPH[C]-amide). The peptide was conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin via the C terminus and injected into rabbits at Quality Controlled Biochemicals (Hopkinton, MA). Antisera were collected and purified by affinity chromatography on a peptide-Sepharose column.

Mitochondria for Western blots were obtained from the same preparations used for the respiration assays and kept frozen at −80°C until used. Twenty micrograms of mitochondrial protein was electrophoresed, blotted onto nitrocellulose, and probed with Sod2 antiserum by using the Western Blot Kit (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories). The bands were visualized by using the Western Breeze chemiluminescence substrate with enhancer (NOVEX, San Diego). To assure approximately equal loading of total protein on SDS/PAGE gels, immunoblots were reversibly stained with Ponceau S dye at 2 g/liter in 1% (vol/vol) acetic acid solution and photographed. Ponceau S was removed by rinsing for 10 min in PBS (pH 7.2), plus 0.05% Tween 20 before incubation in primary antibody.

Mitochondrial Respiration and OXPHOS Enzymology.

Oxygen consumption was measured polarographically with a Clark electrode in 225 mM mannitol/75 mM sucrose/10 mM KCl/10 mM Tris⋅HCl/5 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.2, buffer containing 600 μg of mitochondrial protein and 5 mM succinate as substrate. State III respiration was initiated by adding 125 nmol of ADP, and uncoupled respiration was induced by adding carbonylcyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone to a final concentration of 1 μM. OXPHOS enzyme analysis was carried out as described (23).

Mitochondrial Membrane Electrochemical Potential (ΔΨ).

The mitochondrial ΔΨ was measured by the mitochondrial uptake of tetraphenylphosphonium cation. Changes in extramitochondrial concentration were measured by a tetraphenylphosphonium-cation-sensitive electrode, with ΔΨ calculated by using the Nernst equation.

Lipid Peroxidation Assay.

Levels of lipid peroxides in mitochondria and total cytosolic extracts were measured directly by using the Lipid Hydroperoxide Assay kit (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, catalog no. 705002). For each assay, total lipid was extracted from a suspension containing 1 mg of protein.

Induction of the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore.

The sensitivity of the mtPTP was assayed by the calcium induction of high amplitude swelling of the mitochondria. Six hundred micrograms of mitochondrial protein was suspended in 1.5 ml of 250 mM sucrose/10 mM Mops/2 mM K2HPO4, pH 7.2, containing 5 mM succinate. The mitochondria were treated with 16.5 nmol of CaCl2, and the absorbance at 546 nm was monitored for 25 min. The t1/2 was defined as the time in seconds until the mitochondria were half-maximally swollen. The swelling was inhibitable by 1 μM cyclosporin A.

Terminal Deoxynucleotidyltransferase-Mediated dUTP End Labeling (TUNEL) Analysis.

Apoptotic hepatocytes were identified in 10-μm-thick isopentane frozen liver sections by TUNEL staining using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Approximately, 3,000 nuclei in five 200× fields were counted.

Statistical Analysis.

Data analysis was carried out with graphpad prism software (GraphPad, San Diego) using Student's unpaired t test.

Results

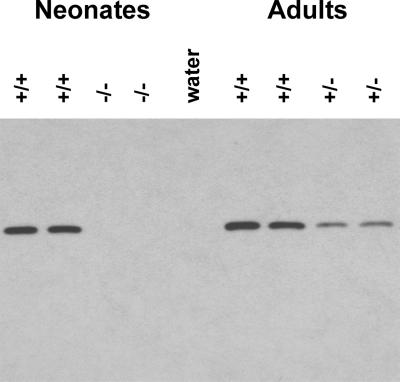

To establish that the Sod2 mutation resulted in a reduction of MnSOD protein in the mutant mice, antibodies recognizing the mitochondrial-specific MnSOD were prepared by using synthetic MnSOD peptides. Western blot analysis of mitochondrial MnSOD from wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygote animal livers revealed that MnSOD was eliminated in Sod2tm1Cje (−/−) animals and reduced ≈50% in the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) animals (Fig. 1). Furthermore, MnSOD levels in Sod2tm1Cje wild-type (+/+) and Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) liver mitochondria were unchanged in young, middle-aged, and old-aged animals (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Western blot analysis of MnSOD expression in Sod2tm1Cje mouse liver mitochondria. Neonate Sod2tm1Cje (−/−) and controls on the left (+/+). Adult Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) and controls (+/+) on the right. Expression was detected with antisera raised against MnSOD.

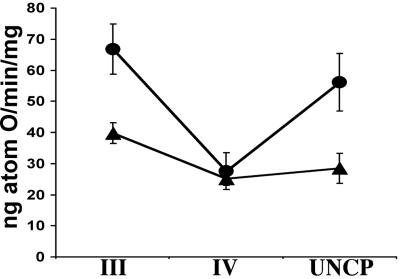

To determine the effects of acute O toxicity

on mitochondrial function, liver mitochondria were isolated from

neonatal Sod2tm1Cje (−/−) mutant mice

and mitochondrial respiration and mtPTP sensitivity assessed. This

revealed that the state III respiratory rates and the RCRs were reduced

40% in the mutant mitochondria, suggesting impaired electron flux

through the ETC (Fig. 2). Moreover,

although initial ADP exposure stimulated respiration ≈1.6-fold,

subsequent addition of uncoupler did not stimulate respiration above

the state IV rate.

toxicity

on mitochondrial function, liver mitochondria were isolated from

neonatal Sod2tm1Cje (−/−) mutant mice

and mitochondrial respiration and mtPTP sensitivity assessed. This

revealed that the state III respiratory rates and the RCRs were reduced

40% in the mutant mitochondria, suggesting impaired electron flux

through the ETC (Fig. 2). Moreover,

although initial ADP exposure stimulated respiration ≈1.6-fold,

subsequent addition of uncoupler did not stimulate respiration above

the state IV rate.

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial oxygen consumption in neonatal Sod2tm1Cje (−/−) and (+/+) livers. Liver mitochondrial respiration was measured on mitochondria from 8- to 10-day-old mice. State III (ADP-stimulated), state IV, and uncoupled respiration rates were determined for Sod2tm1Cje (−/−) (▴) and control (●) animals. The data shown are the means and standard errors for four independent experiments.

To further characterize these mitochondria, we analyzed the Ca2+ sensitivity of the mtPTP. The liver mitochondria of the Sod2tm1Cje (−/−) were found to be much more prone to the permeability transition then were the control mitochondria. After Ca2+ addition, it took the Sod2tm1Cje (−/−) mitochondria 240 sec to achieve half maximal swelling (t1/2), whereas control mitochondria required 375 sec. This increased propensity of the Sod2tm1Cje (−/−) mitochondria to undergo the permeability transition could explain the loss of uncoupler stimulation. When ADP was added to the Sod2tm1Cje (−/−) mitochondria, ΔΨ would be transiently depolarized. The fluctuation of ΔΨ could have been sufficient to activate the hypersensitized mtPTP, releasing the matrix solutes including NAD+ and NADH and the intermembrane protein cytochrome c. The absence of these cofactors would then block the Krebs cycle and the ETC, inhibiting respiration even in the presence of uncoupler. Alternatively, inactivation of one or more of the components of the ETC during state IV respiration might have caused the loss of uncoupler stimulated respiration.

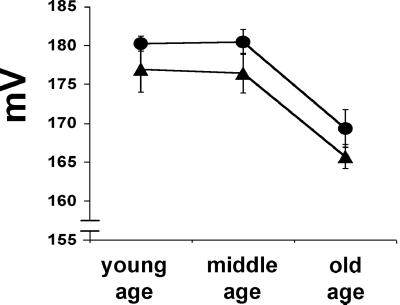

If complete MnSOD deficiency caused severe respiration defects in the newborn, then a partial MnSOD defect might be expected to cause chronic respiratory deficiency in adults. To determine if this was the case, we analyzed liver mitochondrial physiology from young, middle-aged, and old Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mice. The mitochondrial ΔΨ was found to be consistently lower in the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) animals than controls in young and middle-aged animals. Furthermore, ΔΨ declined in parallel for both genotypes in old animals (Fig. 3). Hence, the increased exposure of the mitochondrial inner membrane to ROS in the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mice appears to have caused an increased permeability to protons. Because ΔΨ declines in both strains with age it follows that aging is associated with an increase in mitochondrial inner membrane proton permeability due to the effects of chronic oxidative damage.

Figure 3.

Measurement of the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨ) in aging Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) and (+/+) mouse livers. ΔΨ was measured by the uptake of tetraphenylphosphonium cation (TPP+) in Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) (▴) and in control (●) animals. The data shown are the means and standard errors for four to six independent experiments.

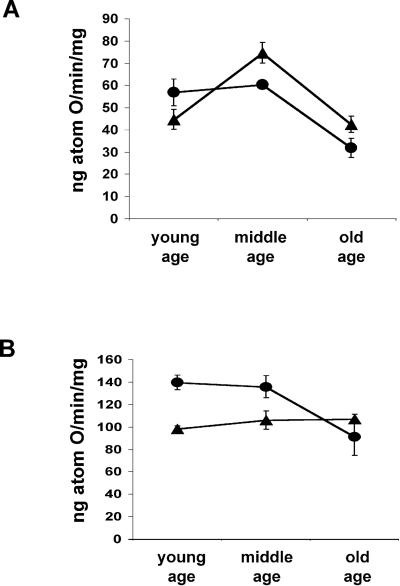

Analysis of the unstimulated (state IV) respiration rates revealed interesting differences between Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) and (+/+) mice. In mitochondria from young Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) and control mice, the state IV rates were at a similarly low level. However by middle age, the state IV respiration rates of the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mitochondria were significantly higher than controls (Fig. 4A). This remained true for the old animals, even though both the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) and control state IV values declined ≈45%. The increased state IV rates of the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) liver mitochondria would support the conclusion that the mitochondrial inner membrane develops an increased proton leak in response to chronic oxidative stress. The initially lower Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) state IV level and the decline in state IV rates with old age may reflect partial inhibition of the ETC due to chronic oxidative stress. This interpretation was supported by the state III respiration rates.

Figure 4.

Mitochondrial oxygen consumption in aging Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) and (+/+) mouse livers. (A) State IV rates of aging Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) (▴) and controls (●). (B) State III (ADP-stimulated) rates of aging Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) (▴) and controls (●). Data shown are the means and standard errors for four to six independent experiments.

Analysis of the ADP-stimulated (state III) respiration rates for the young and middle-aged Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mice revealed that they were substantially below those of age-matched controls. Moreover, in old control (+/+) mice the state III rates declined to those of the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mitochondria (Fig. 4B). The reduced state III rates in the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mitochondria suggest an impaired electron flux through the respiratory chain possibly due to oxidative damage to inner membrane lipids effecting respiratory complex interaction and/or the inactivation of iron–sulfur center containing enzymes. Although the maximum effect of this oxidative damage is already present in young Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mice, the same effect is not seen until old age in the normal Sod2tm1Cje (+/+) mice.

Because of the unusual effects of mitochondrial

O toxicity on respiration in

Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) animals, the RCR

decreased in middle-aged animals along with an increase in state IV

respiration rates. But the RCR was partially normalized in the old

Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mice because of the

marked decline in the state IV respiration without an appreciable

change in the state III respiration rate. The P/O ratio of the

Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) animals also declined

relative to the controls in the middle-aged animals, but normalized in

the older Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mice (data

not shown).

toxicity on respiration in

Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) animals, the RCR

decreased in middle-aged animals along with an increase in state IV

respiration rates. But the RCR was partially normalized in the old

Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mice because of the

marked decline in the state IV respiration without an appreciable

change in the state III respiration rate. The P/O ratio of the

Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) animals also declined

relative to the controls in the middle-aged animals, but normalized in

the older Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mice (data

not shown).

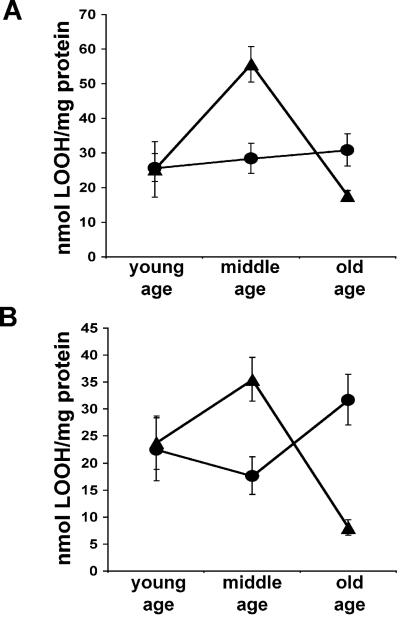

One possible source of the increased proton leak through the mitochondrial inner membrane might be chronic oxidative damage to mitochondrial lipid bilayers. This possibility was confirmed by measuring the lipid peroxidation levels in Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) and (+/+) mice. Although young Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) and control animals had the same levels of lipid peroxidation, the middle-aged Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mouse liver mitochondria contained twice the lipid hydroperoxides of the control mitochondria (Fig. 5A). A parallel increase was seen in the lipid peroxide levels of total liver extracts (Fig. 5B), suggesting that the mitochondria accumulate significant oxidative damage to their membranes. Surprisingly, the lipid peroxidation levels in the old Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) animals declined (Fig. 5 A and B), whereas those of the control cytosol increased. These observations imply that the mitochondrial lipids are an important target for ROS damage in the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mouse livers, and that some process selectively removes the peroxidized lipids from the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) liver when they surpass a certain critical level. This same process presumably occurs in Sod2tm1Cje (+/+) livers, but at a later time.

Figure 5.

Lipid peroxidation measurements in aging Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) and (+/+) mouse livers. (A) Levels of lipid peroxides in liver mitochondria from Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) (▴) and controls (●). (B) Total liver cytoplasmic lipid peroxide measurements from Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) (▴) and controls (●). Data shown are the means and standard errors from four independent experiments performed in triplicate.

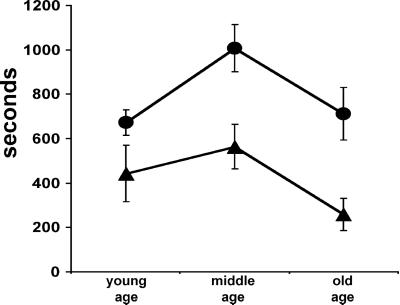

The increased oxidative stress in the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mouse livers might also affect the function of the mtPTPs, making them more prone to activation. To determine if this was the case, we measured the time to half maximal mitochondrial swelling (t1/2) after Ca2+ exposure. At all ages, the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mtPTPs responded much more rapidly to Ca2+ challenge than controls (Fig. 6). The t1/2 for swelling was 33% faster in the young Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mitochondria and 50% faster in the middle-aged Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mitochondria (+/− = 550 sec vs. +/+ = 1,000 sec). Furthermore, in the older mice, the t1/2 for both the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) and (+/+) mitochondria decreased and the difference between the two increased (+/− = ≈250 sec vs. +/+ = ≈700 sec) (Fig. 6). This result indicates that the chronic oxidative stress in the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mitochondria substantially increases the propensity for mtPTP transition and that the sensitization of the mtPTP increases from middle to old age.

Figure 6.

Calcium-induced high-amplitude swelling (t1/2) in aging Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) and (+/+) mouse livers. The opening of the mtPTP was measured by cyclosporin A-inhibitable high-amplitude swelling in Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) (▴) and controls (●). The t1/2 is defined as the time in seconds until the mitochondria are half maximally swollen. The data shown are the means and standard errors from six independent experiments.

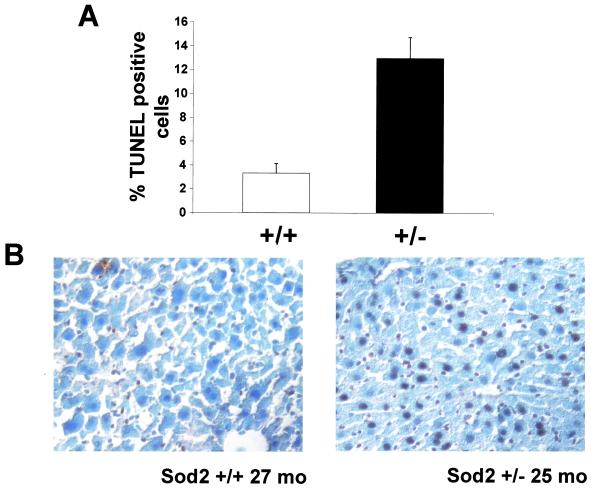

To determine the effect of the hypersensitized mtPTP on liver tissue integrity, we used TUNEL staining to determine if Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) hepatocytes had an increased propensity for apoptosis. Although Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) hepatocyte apoptosis rates were the same as controls for young and middle-aged animals, the difference in hepatocyte apoptosis rates of older animals was dramatic. Old Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mouse livers had three times more apoptotic hepatocytes than did the old control mouse livers (Fig. 7). Thus, the chronic oxidative stress caused by the partial MnSOD deficiency ultimately resulted in sufficient mitochondrial oxidative damage to initiate a wave of apoptosis in old Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) livers.

Figure 7.

TUNEL analysis of old Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) and (+/+) mouse livers. Livers were snap frozen, sectioned, and analyzed for apoptotic hepatocytes. (A) The percentages of TUNEL-positive hepatocytes were determined from six separate livers. The data and the means and standard errors are shown. (B) Liver images from an old Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) and control mouse.

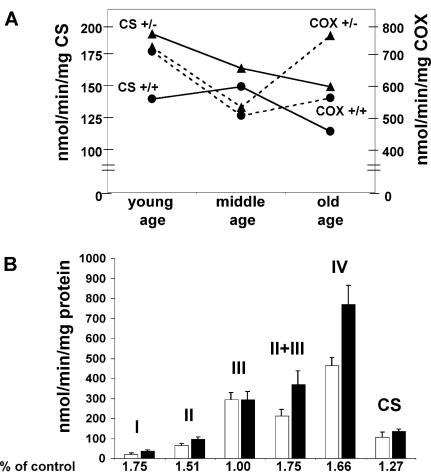

The age-related decline in mitochondrial function might be partially offset by the compensatory up-regulation of mitochondrial OXPHOS enzymes, a phenomena well-documented in patients with mitochondrial disease (24). To determine if this was the case, the mitochondrial enzymes in the older Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) animals were assayed. The liver mitochondria OXPHOS complexes I, II, II + III, and IV as well as citrate synthase were all elevated 25–75% in the old Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mice relative to the old controls (Fig. 8). Monitoring the enzyme activities over time revealed that citrate synthase was elevated in Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mice compared to controls throughout life but declined as the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mice aged. By contrast, complex IV (COX) declined in both the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) and Sod2tm1Cje (+/+) mice from young to middle age, but in the old Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mice it increased markedly while remaining low in controls. Thus, the activities of the mitochondrial enzymes were coordinately up-regulated in older Sod2 tm1Cje (+/−) mice. This result implies that the (+/−) animals are attempting to compensate for a cumulative energetic deficiency caused by chronic mitochondrial oxidative stress. Alternatively, the increase in the activities of the mitochondrial enzymes could result from the elimination of the oxidatively damaged mitochondria in the old Sod2tm1Cje (+/−).

Figure 8.

Mitochondrial OXPHOS enzymology measurements of Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) and (+/+) mice. (A) Measurements of the changes of cytochrome c oxidase (COX) and citrate synthase (CS) with age in Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) (▴) and controls (●). (B) Relative enzyme activities of liver submitochondrial particles in old Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) (■) and controls (□). The data shown are the means and standard errors of four independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Discussion

The current studies strongly support the importance of mitochondrial ROS toxicity in causing mitochondrial bioenergetic decline and the initiation of apoptosis in aging and senescent tissue. This is consistent with the three major cellular processes controlled by the mitochondria: energy metabolism, ROS production, and the regulation of apoptosis.

Mitochondria from the Sod2tm1Cje (−/−) animals, which are acutely exposed to high levels of mitochondrial ROS, experience severe mitochondrial dysfunction and a marked propensity to undergo the permeability transition. The precocious opening of the mtPTP probably explains the lack of uncoupler stimulation of respiration, subsequent to ADP stimulation of respiration. In state III respiration, ΔΨ transiently declines as protons are used to drive ADP phosphorylation by the ATP synthase. The drop in ΔΨ may be sufficient to activate the mtPTP, already hypersensitized by oxidative stress. The opening of the mtPTP would cause the loss of matrix NAD+/NADH, stalling the tricarboxylic acid cycle and ETC and blocking uncoupled respiration. This same pattern of respiratory dysfunction has been observed in the senescence-accelerated mouse (25), suggesting that the biochemical defect in this animal might also be related to mitochondrial energy deficiency, oxidative stress, and apoptosis.

Mitochondria from the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) animals, which were chronically exposed to sublethal levels of mitochondrial ROS and oxidative stress, took much longer to develop respiratory deficiency and an increased propensity for mtPTP transition. These deleterious effects on respiration were partially offset by the up-regulation of OXPHOS complex activity.

However, as the mitochondria of the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) cells accumulated oxidative damage, they ultimately crossed the mtPTP threshold and were destroyed by cellular apoptosis. This premature accumulation of mitochondrial damage followed by the destruction of the cells with the most damaged mitochondria by apoptosis provides an explanation for precipitous loss of increased mitochondrial and cytosolic lipid peroxidation from middle-aged to old Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) mice. However, this normalization of the average mitochondrial parameters presumably coincides with the massive loss of hepatocytes from the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) tissues, and thus leading to tissue atrophy, functional decline, and ultimately failure.

Although the Sod2tm1Cje (+/−) animal tissues accumulated mitochondrial oxidative damage much sooner than control (+/+) animals, the control animals ultimately also accumulate significant levels of mitochondrial damage with age. Thus, these data demonstrate that aging has a major mitochondrial ROS component, and that the rate of mitochondrial damage is related to the level of ROS production.

In conclusion, as mammals age mitochondrial ROS production and oxidative stress causes increased proton leak across the mitochondrial inner membrane, inhibition of the ETC, oxidation of mitochondrial lipids, sensitization of the mtPTP, and ultimately cellular death by apoptosis. In animals with increased mitochondrial ROS toxicity, in this case due to MnSOD deficiency, mitochondrial oxidative damage, impaired respiration and heightened mtPTP activation occur earlier in life than in animals with normal ROS production. Ultimately, however, sufficient damage accumulates in all strains to initiate apoptosis, resulting in tissue decline and senescence. Therefore, the age-related accumulation of mitochondrial oxidative damage leading to mtPTP activation and apoptosis appears to be a major factor in senescence and aging.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Barbara Cottrell for preparing the MnSOD antibody. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AG13154, NS21328, and HL64017 and an Ellison Medical Foundation Grant awarded to D.C.W.

Abbreviations

- OXPHOS

oxidative phosphorylation

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- MnSOD

manganese superoxide dismutase

- Sod2

superoxide dismutase 2

- mtPTP

mitochondrial permeability transition pore

- ETC

electron transport chain

- RCR

respiratory control ratio

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP end labeling

References

- 1.Kapahi P, Boulton M E, Kirkwood T B. Free Radical Biol Med. 1999;26:495–500. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandy B, Davison A J. Free Radical Biol Med. 1990;8:523–539. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harman D. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1972;20:145–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1972.tb00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linnane A W, Marzuki S, Ozawa T, Tanaka M. Lancet. 1989;i:642–645. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miquel J, Economos A C, Fleming J, Johnson J E., Jr Exp Gerontol. 1980;15:575–591. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(80)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallace D C. Science. 1992;256:628–632. doi: 10.1126/science.1533953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallace D C. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:1175–1212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.005523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chance B, Sies H, Boveris A. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:527–605. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richter C, Park J W, Ames B N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6465–6467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turrens J F, Alexandre A, Lehninger A L. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;237:408–414. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giulivi C, Boveris A, Cadenas E. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;316:909–916. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petronilli V, Costantini P, Scorrano L, Colonna R, Passamonti S, Bernardi P. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16638–16642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zoratti M, Szabo I. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1241:139–176. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(95)00003-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu X, Kim C N, Yang J, Jemmerson R, Wang X. Cell. 1996;86:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bernardi P. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:8834–8839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petronilli V, Cola C, Massari S, Colonna R, Bernardi P. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:21939–21945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lapidus R G, Sokolove P M. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18931–18936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Huang T T, Carlson E J, Melov S, Ursell P C, Olson J L, Noble L J, Yoshimura M P, Berger C, Chan P H, et al. Nat Genet. 1995;11:376–381. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melov S, Coskun P, Patel M, Tuinstra R, Cottrell B, Jun A S, Zastawny T H, Dizdaroglu M, Goodman S I, Huang T T, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:846–851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reaume A G, Elliott J L, Hoffman E K, Kowall N W, Ferrante R J, Siwek D F, Wilcox H M, Flood D G, Beal M F, Brown R H, Jr, et al. Nat Genet. 1996;13:43–47. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlsson L M, Jonsson J, Edlund T, Marklund S L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6264–6268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams M D, Van Remmen H, Conrad C C, Huang T T, Epstein C J, Richardson A. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28510–28515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trounce I A, Kim Y L, Jun A S, Wallace D C. Methods Enzymol. 1996;264:484–509. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)64044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heddi A, Stepien G, Benke P J, Wallace D C. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22968–22976. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.22968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakahara H, Kanno T, Inai Y, Utsumi K, Hiramatsu M, Mori A, Packer L. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;24:85–92. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00164-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]