Abstract

Diversities in human physiology have been partially shaped by adaptation to natural environments and changing cultures. Recent genomic analyses have revealed single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are associated with adaptations in immune responses, obvious changes in human body forms, or adaptations to extreme climates in select human populations. Here, we report that the human GIP locus was differentially selected among human populations based on the analysis of a nonsynonymous SNP (rs2291725). Comparative and functional analyses showed that the human GIP gene encodes a cryptic glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) isoform (GIP55S or GIP55G) that encompasses the SNP and is resistant to serum degradation relative to the known mature GIP peptide. Importantly, we found that GIP55G, which is encoded by the derived allele, exhibits a higher bioactivity compared with GIP55S, which is derived from the ancestral allele. Haplotype structure analysis suggests that the derived allele at rs2291725 arose to dominance in East Asians ∼8100 yr ago due to positive selection. The combined results suggested that rs2291725 represents a functional mutation and may contribute to the population genetics observation. Given that GIP signaling plays a critical role in homeostasis regulation at both the enteroinsular and enteroadipocyte axes, our study highlights the importance of understanding adaptations in energy-balance regulation in the face of the emerging diabetes and obesity epidemics.

Recent studies have revealed that genetic variation underlies a variety of diversities in human physiology and pathology (Sabeti et al. 2005; Voight et al. 2006, 2010; Sulem et al. 2007; Tishkoff et al. 2007; Genovese et al. 2010; Leslie 2010; Simonson et al. 2010; Yi et al. 2010). Among the sundry forms of genetic variation, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with high population differentiation are regarded as candidates of adaptation to recent changes in human environment and culture, and have been shown to play an important role in acquiring distinct physiological traits and susceptibility to different diseases among the populations (Barreiro and Quintana-Murci 2010; Chen et al. 2010; Gibbons 2010; Ingelsson et al. 2010; Laland et al. 2010; Luca et al. 2010; Richerson et al. 2010). Thus, the identification of causal SNPs with signatures of positive selection and underlying functional changes is crucial to a better understanding of the relationship between genomic variation and human health as well as gene–environmental interactions (Nielsen et al. 2007; Laland et al. 2010; Nei et al. 2010). To systematically analyze the contributions of genetic variation in intercellular signaling molecules to physiological diversities in humans, we studied SNPs in the coding region of 839 human polypeptide hormones and their cognate receptors for evidence of selection using the data from the International HapMap project phases I and II (International HapMap Project 2003; International HapMap Consortium 2007). We focused on these polypeptide ligands and receptors because they represent half of the targets of modern medicine (Drews 2000) and because the genes associated with intercellular communication or the responses to environmental factors (e.g., pathogens and food sources) have been implicated in the evolution of a variety of common traits and pathologies in humans and other vertebrates (Seminara et al. 2003; Sabeti et al. 2005; Hoekstra et al. 2006; Lalueza-Fox et al. 2007; Sulem et al. 2007; Chambers et al. 2008; Prokopenko et al. 2008; Shiao et al. 2008; Shimomura et al. 2008; Anderson et al. 2009; Topaloglu et al. 2009). Here, based on genomic and biochemical analyses, we show that variants in an incretin hormone gene, GIP, were differentially selected in human populations, and a nonsynonymous SNP, rs2291725, represents a functional mutation. Because changes in the food source represented one of the most important selection pressures during the transitions of human culture and because incretin hormones play critical roles in homeostasis maintenance at the enteroinsular and enteroadipocyte axes, future studies of potential genotype–phenotype relationships for the selected GIP variants could provide a better understanding of which and how these variants contribute to phenotypic variation in energy-balance regulation among individuals or human populations.

Results

A nonsynonymous SNP (rs2291725) in the human glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide gene exhibits high population differentiation

To investigate whether variation in the polypeptide intercellular signaling molecules contribute to physiological diversities in humans, we curated 457 human G-protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) and their cognate ligand genes as well as 382 human non-GPCR receptor and ligand genes (Supplemental Table 1; Ben-Shlomo et al. 2003; Semyonov et al. 2008). We started by using the population differentiation statistic FST to identify the leads for functional characterization (Lewontin and Krakauer 1973; Akey et al. 2002; Li et al. 2008).

We computed the FST for the coding SNPs of GPCR and ligand genes and compared the result with those for coding SNPs of all other human genes. FST was computed between all possible pairs of HapMap II populations (YRI [African, Yoruba from Ibadan], CEU [European, United States residents with northern and western European ancestry], and ASN [East Asian, pooled samples of Chinese from Beijing {CHB} and Japanese from Tokyo {JPT}]). Distributions of FST for either the synonymous or nonsynonymous SNPs between any two HapMap II populations showed no difference (all P > 0.01, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) (Supplemental Fig. 1). Likewise, studies of the FST of coding SNPs in 382 non-GPCR receptor and ligand genes have shown similar cumulative distribution function (CDF) plots, suggesting that there is no difference in FST distribution between the GPCR and the non-GPCR groups (P > 0.01, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) (Supplemental Fig. 2). These results suggest that, when analyzed as a whole set, the coding SNPs of human polypeptide receptor and ligand genes do not have a significantly elevated FST.

Nevertheless, at the individual-gene level, dozens of coding SNPs in these receptor and ligand genes have a high FST (>0.5) between select pairs of populations (Supplemental Tables 2, 3). Among GPCRs and their cognate ligands, DRD5, DARC, CELSR1, CCL23, GIP, MC1R, EMR1, GRM1, CALCR, CXCR6, GPR39, and DRD3 were found to have nonsynonymous SNPs with a high FST, which suggests that these SNPs are likely to be targets of selection. On the other hand, nonsynonymous SNPs in EDAR, which has been repeatedly shown to be under positive selection (Bryk et al. 2008; Fujimoto et al. 2008), and several immune response–related genes (e.g., IL4R, TNFRSF10A, TRAF3, IL29, IL20RA, IL1RL1, TNFRSF6B, and PTPRA) in the non-GPCR group were found to have high FST scores in select pair(s) of the populations.

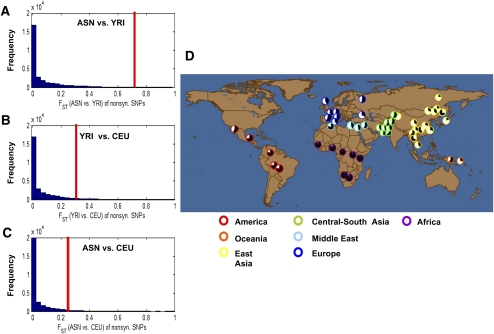

Importantly, we found that the nonsynonymous SNP (rs2291725) in exon 4 of the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide gene (or gastric inhibitory peptide, GIP; referred to as the GIP103T/C mutation in the following text) on chromosome 17 is highly linked with a cluster of neighboring SNPs within a 250-kb region (starting from rs8079874 to rs2291726) and has an FST value in the top 0.5% of all nonsynonymous SNPs in comparisons between the ASN and YRI populations (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Table 2). In contrast, FST estimates in comparisons between CEU and YRI or between CEU and ASN were not different from the genome average (Fig. 1B,C). Consistently, data from the HGDP-CEPH project (Center d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain-Human Genome Diversity Panel; 944 unrelated individuals from 52 populations) (Cann et al. 2002; Rosenberg 2006; Li et al. 2008) and the Human Genome Center at the University of Tokyo (752 Japanese individuals, GIP103C/GIP103T = 0.732/0.268) showed that the derived GIP103C allele frequency at rs2291725 is much higher (>60%) in the majority of East Asian populations and varies widely among other populations: ranging from 0.0%–9.5% in sub-Saharan Africans and increasing to >40.0% in European and Middle Eastern populations (Fig. 1D; Table 1; Supplemental Table 5).

Figure 1.

Differential distribution of alleles at rs2291725 in human populations. (A–C) The distribution of the FST for nonsynonymous SNPs across the human genome and the FST for rs2291725. FST estimations between ASN and YRI (A), YRI and CEU (B), and ASN and CEU (C) are shown in the x-axis. The red vertical bar indicates the corresponding values of FST for rs2291725. The y-axis represents the frequency of SNPs with a given FST estimate. Statistical significance for comparisons in A, B, and C is indicated with empirical P = 0.0039, 0.058, and 0.047, respectively. The number of coding SNPs that were analyzed in the A, B, and C histograms was 48,526, 48,674, and 48,075, respectively. Among these SNPs, the number of nonsynonymous SNPs in the A, B, and C histograms was 29,033, 29,026, and 28,774, respectively. (D) Distribution of rs2291725 in the HGDP–CEPH (944 unrelated samples) populations. Pie charts represent the proportion of each genotype by geographic region. The ancestral GIP103T allele (black pie) occurs at a higher frequency in African and American populations, whereas the majority of Eurasian populations have a higher frequency of the derived GIP103C allele (white pie).

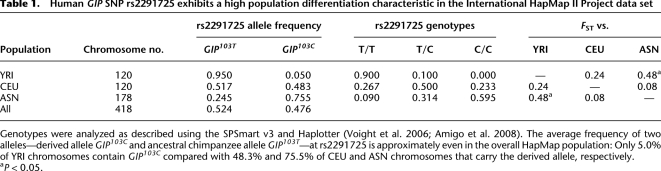

Table 1.

Human GIP SNP rs2291725 exhibits a high population differentiation characteristic in the International HapMap II Project data set

Genotypes were analyzed as described using the SPSmart v3 and Haplotter (Voight et al. 2006; Amigo et al. 2008). The average frequency of two alleles—derived allele GIP103C and ancestral chimpanzee allele GIP103T—at rs2291725 is approximately even in the overall HapMap population: Only 5.0% of YRI chromosomes contain GIP103C compared with 48.3% and 75.5% of CEU and ASN chromosomes that carry the derived allele, respectively.

aP < 0.05.

GIP encodes one of the two incretin hormones (glucagon-like peptide-1[GLP-1] and GIP) in humans and plays a critical role in normal carbohydrate and lipid metabolism (Kim and Egan 2008). After ingestion of nutrients, GIP secreted from duodenal and jejunal K cells acts on pancreatic β cells to stimulate the release of insulin, which thereby ensures the prompt uptake of glucose and lipids into the tissues. Abnormal regulation of GIP signaling leads to altered carbohydrate metabolism and lipid accumulation at the enteroinsular and enteroadipocyte axis, respectively (Miyawaki et al. 2002; Fulurija et al. 2008; Isken et al. 2008; Kim and Egan 2008). In mice, the deletion of the GIP receptor (Gipr) led to impaired first-phase glucose-stimulated insulin release (Miyawaki et al. 2002), whereas exogenous GIP was found to worsen post-prandial hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes (Chia et al. 2009). In addition to effects on glucose homeostasis, GIP has been shown to promote obesity in mice that were fed a high-fat diet (McClean et al. 2007; Gniuli et al. 2010). Because the incretin effect induced by the oral glucose intake leads to a higher insulin response compared with that from a matched intravenous glucose stimulation, the regulation of glucose levels by GIP represents a critical endocrine circuit to monitor exogenous energy intake and regulate subsequent storage (Kim and Egan 2008). In addition, the critical role of GIP signaling in energy-balance regulation has been highlighted by recent studies that showed that variants at the GIPR locus are associated with glucose levels 2 h after an oral glucose challenge test used in the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes (Ingelsson et al. 2010; Saxena et al. 2010). On the other hand, epidemiological studies have shown that the prevalence of different forms of diabetes and obesity as well as the regulation of glucose metabolism vary widely among ethnic groups (Buchanan and Xiang 2005; Kim and Egan 2008). Thus, the observed high population differentiation in GIP polymorphisms could be associated with the adaptations of incretin physiology to recent changes in diets and cultures in select human populations. To test this hypothesis, we fine mapped the GIP locus and tested the functions of GIP variants in vitro and in vivo.

Variants at the GIP locus were partially selected in Eurasian populations

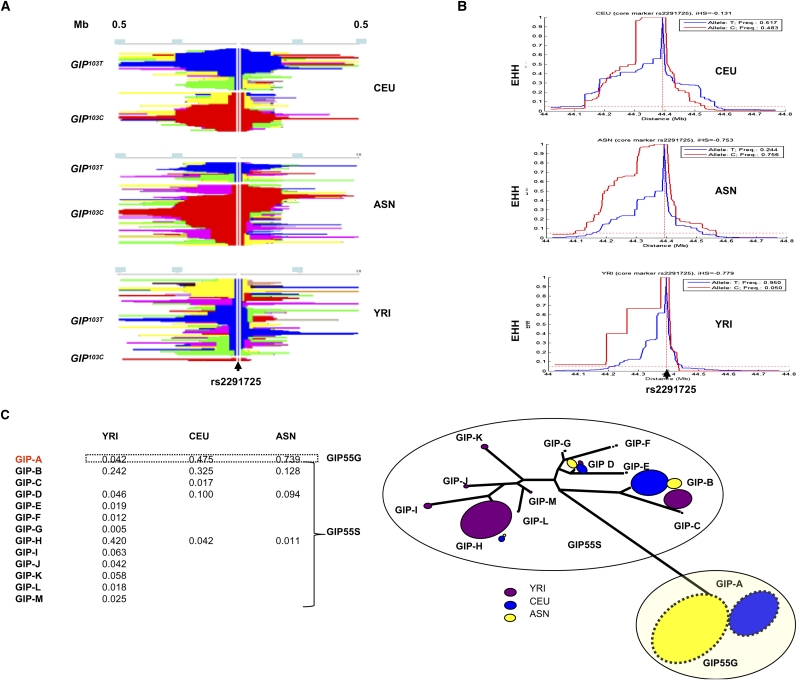

Analyses of linkage disequilibrium (LD) in the GIP region for the three HapMap II populations showed that extended LD blocks are present in the CEU and ASN chromosomes, and these blocks encompass GIP and the neighboring UBE2Z, SNF8, and ATP5G1 genes (Supplemental Fig. 3A,B, red square, D′ = 1, likelihood of odds [LOD] scores >2). In contrast, the majority of SNP pairs in the GIP region of the YRI chromosomes exhibited a low LOD and a low r2 (Supplemental Fig. 3C, blue square, D′ = 1, LOD scores <2). Consistent with the LD analysis, plots depicting the haplotype map showed that most of the chromosomes with the derived GIP103C allele in the ASN population have haplotypes extending >200 kb and are significantly longer compared with chromosomes with the ancestral GIP103T allele (Fig. 2A, middle panel, P < 0.001). In contrast, most chromosomes in YRI did not exhibit an extended haplotype surrounding the GIP103 allele (Fig. 2A, bottom panel). These results were reflected in the plots of extended haplotype homozygosity (EHH) decay curves (Fig. 2B). In ASN and CEU, the EHH curve for chromosomes carrying the derived GIP103C allele extends much further than that for the ancestral allele. To test whether the area under the EHH curve is greater for a selected allele than for a neutral allele, we calculated the integrated haplotype score (iHS) for rs2291725 as a core marker (Voight et al. 2006). By using a coalescent model that generated 10,000 data sets from the same length of genome region (750 kb) with the same sample size (180 chromosomes), we found that the observed iHS for the derived allele in ASN (iHS = −0.753)—but not CEU (iHS = −0.131)—deviated significantly from the neutral distribution (P < 1 × 10−4) (Supplemental Fig. 4A). We also performed coalescent simulations that took into account the effects of demography (e.g., population bottleneck) (Supplemental Fig. 4B) and recombination hotspot, respectively (Hellenthal and Stephens 2007; Gutenkunst et al. 2009; Supplemental Methods). Consistently, we found that no iHS for the simulated haplotype sets is more negative than the observed iHS for rs2291725 under the bottleneck scenario (empirical P < 1 × 10−4), and only a few are in the presence of a recombination hotspot (empirical P < 8 × 10−4) (Supplemental Fig. 4A). These results indicated that the observed iHS has deviated significantly from the neutral distribution even after adjusting for the bias that may have been introduced by a bottleneck in demography or heterogeneous recombination events. Thus, it is unlikely that neutral evolution alone explains the observed long haplotypes that carry the derived GIP103C allele in the ASN population.

Figure 2.

Evolution of haplotypes encompassing the GIP locus. (A) Plots of the extent of haplotype homozygosity in the 1.0-Mb region surrounding rs2291725 in CEU, ASN, and YRI as assessed by Haplotter (Voight et al. 2006). These plots are divided into two parts. The upper portion shows haplotypes with the ancestral GIP103T allele in blue, and the lower portion shows haplotypes with the derived GIP103C allele in red. Adjacent haplotypes with the same color carry identical genotypes spanning the region between a select SNP and rs2291725. (B) Plots of the breakdown of EHH over the distance between rs2291725 and neighboring SNPs at increasing distances. EHH decays much slower at the derived allele (red) compared with the ancestral allele (blue) in ASN and CEU. The position of rs2291725 at the center of the plots is indicated by a vertical dotted line. (C) Evolution of haplotypes within a 70-kb core haploblock in the three HapMap II populations. A total of 13 haplotypes was found in the core region from rs196241 to rs2291726 (37 SNPs at chr 17, 44325258–44394253). The frequencies of these haplotypes (GIP-A∼M) in YRI, CEU, and ASN are shown in the lower left panel. There are 12 haplotypes in YRI, whereas CEU and ASN are represented by five and four haplotypes, respectively. GIP-A is the only haplotype containing the derived GIP103C allele and is indicated by a dotted box. An unrooted tree analysis of these haplotypes showed that the GIP-A haplotype diverged from others early in human evolution (GeneBee). The frequency of each haplotype in a select population is indicated by the size of the pie at the tip of each branch.

Further examination of the extended haplotype blocks in ASN showed that rs2291725 is highly linked with another 43 SNPs within the adjacent 250-kb region, and in a 70-kb core region (rs1962412 to rs2291726; Genome build 36.3, chr 17, 44325258–44394253), the derived GIP103C allele is associated with a single haplotype (Fig. 2C, haplotype GIP-A; Supplemental Fig. 3D; Supplemental Table 4). In contrast, the ancestral GIP103T allele found in the majority of the YRI chromosomes is represented by 12 different haplotypes (Fig. 2C, haplotypes GIP-A, GIP-B, and GIP-D–M; Supplemental Fig. 3D). An unrooted tree analysis of these haplotypes confirmed that the evolutionary trajectory of the GIP103C-associated haplotype is distinct from other haplotypes (Fig. 2C). Given the presence of several characteristic patterns, including highly differentiated alleles, high frequency–derived alleles, and relatively long derived haplotypes, these data suggested that pre-existing polymorphisms at the GIP locus were partially selected in ASN and possibly in CEU at times post-dating the separation of the YRI and Eurasian populations (Smith and Haigh 1974).

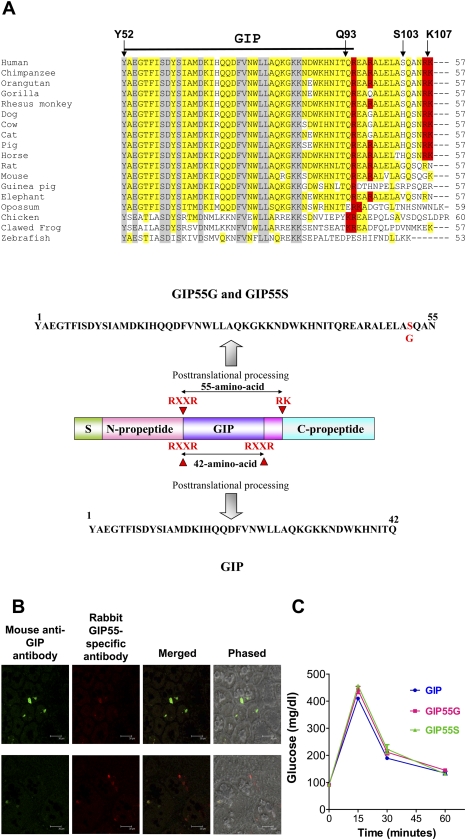

GIP encodes a GIP peptide containing the variable residue (Ser103 or Gly103) at rs2291725

Whereas the selection at the GIP locus could be attributed to a single variant or a combination of SNPs, the nonsynonymous rs2291725 provided a tangible target for functional analyses of the causal mutation. To explore whether rs2291725 represented a causal variant and provided a benefit to its carriers, we investigated the function of the GIP peptides containing the variable residue (Ser103 for GIP103T or Gly103 for GIP103C). GIP was originally characterized as a 42-amino-acid peptide derived from proteolytic processing at the monobasic cleavage sites at residues 51 and 94 of the GIP open reading frame (Moody et al. 1984; Takeda et al. 1987; Kim and Egan 2008). Although residue 103 is located outside the conventional mature GIP sequence (residues 52–93) (Fig. 3A, upper panel), we noticed that a conserved dibasic cleavage site (Arg-Lys, residues 106–107) is located 13 amino acids downstream from the conventional cleavage site in primates, dogs, cats, cows, pigs, and horses (Fig. 3A, upper panel). Thus, post-translational cleavage at this alternative processing site could generate an extended GIP isoform 13 amino acids longer (Fig. 3A, lower panel; the ancestral GIP55S and the derived GIP55G). To investigate this possibility, we analyzed whether the GIP55 peptide is expressed in gut cells of the proximal small intestine. In support of our hypothesis, the immunohistochemical analysis of human duodenum sections with a rabbit GIP55-specific antibody and a mouse anti-GIP antibody showed that immunoreactive GIP55 and GIP are colocalized in select duodenum cells, suggesting that GIP55 is present in gut cells that normally express GIP (Fig. 3B). To study whether GIP55 is secreted into general circulation, we then analyzed the presence of GIP55 in serums of individuals 30 min after a regular breakfast meal using a sandwich ELISA assay that detects the extended C-terminal sequences specific to GIP55. Consistently, we found that GIP55 is present in human serum and constitutes ∼1%–3% of the total GIP after a meal (GIP55, 2.91 ± 0.41 pmol/L; total GIP, 95.1 ± 9.41 pmol/L, N = 6). Thus, depending on the genotype, humans could contain two (GIP103T/T: GIP+GIP55S; GIP103C/C: GIP+GIP55G) or three GIP isoforms (GIP103T/C: GIP+GIP55S+GIP55G) (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

An extended GIP peptide is expressed in human gut cells. (A) Alignment of human GIP (residues Y52 to K107) with corresponding residues from 17 other vertebrates showed that the GIP open reading frame contains alternative basic cleavage sites for the generation of multiple GIP isoforms in primates, dogs, cats, cows, pigs, and horses (upper panel). The mature peptide region is indicated by a dark horizontal bar above the alignment. Residues that are conserved from teleosts to humans are indicated by a gray background. Putative basic cleavage sites are indicated by a red background. The position of the variable residue 103 is indicated by an arrow. Alternative post-translational processing of proGIP could lead to the generation of a 42-amino-acid mature GIP and an extended 55-amino-acid isoform (GIP55G or GIP55S) that differ at position 52 (lower panel). (B) GIP and GIP55 peptides are colocalized in the duodenum cells. Immunoreactive GIP and GIP55 were detected in select duodenum cells by immunofluorescent staining. The right panels showed the dark field and phased contrast images of merged immunofluorescent signals (800×). The white horizontal bar in each panel represents a distance of 30 μm. (C) GIP, GIP55G, and GIP55S suppressed exogenous glucose in fasting rats in vivo. Each of the three GIP peptides reduced glucose contents in the blood to basal levels at 1 h after injection of the peptide and glucose. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM of triplicate samples. Similar results were observed in five separate experiments.

Because the receptor-activation domain of GIP is located at the N terminus of the peptide, we reasoned that alternative processing at the C terminus of GIP55 peptides is unlikely to decimate their bioactivity. Indeed, functional testing of the synthetic GIP isoforms (GIP, GIP55G, and GIP55S) in vivo showed that similar to conventional GIP, the extended GIP55G and GIP55S suppress hyperglycemia to similar extents in a time-dependent manner in fasting rats (Fig. 3C).

The ancestral GIP55S and the derived GIP55G peptides exhibit distinct bioactivity profiles in vitro

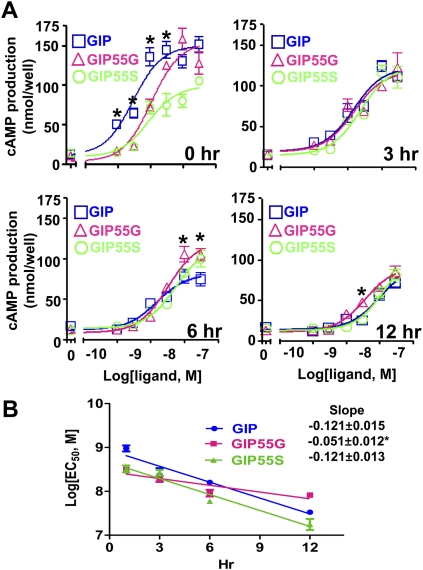

To compare the bioactivity of GIP isoforms and variants, we measured their receptor-activation activities in vitro using HEK293T cells expressing a recombinant human GIP receptor. As expected, treatments of GIP led to dose-dependent increases of cAMP production in transfected cells (Fig. 4A, top left panel). Unlike conventional GIP, which exhibits an EC50 of ∼0.9 ± 0.21 nM, the extended GIP isoforms have approximately threefold lower potencies (GIP55G, 3.2 ± 0.21 nM; GIP55S, 2.6 ± 0.23 nM) (Supplemental Table 6). Importantly, we found that the derived GIP55G consistently increases cAMP production to significantly higher levels compared with the ancestral GIP55S (Fig. 4A, top left panel). Because GIP is known to be susceptible to serum degradation in vivo, we also studied the stability of GIP isoforms in human serum in vitro. Surprisingly, we found that GIP55G and GIP55S are more resistant to degradation by either pooled normal human serum (Fig. 4A) or pooled complement-preserved human serum (Supplemental Fig. 5). The ranking of potency on receptor activation shifted from GIP > GIP55G > GIP55S at 0 h to GIP = GIP55G = GIP55S and GIP55G > GIP55S ≥ GIP, respectively, after a 6-h or a 12-h preincubation with either normal serum (Fig. 4A), or complement-preserved serum (Supplemental Fig. 5). Plots of EC50 data in relation to the length of incubation showed that the slope of changes in the bioactivity for GIP is significantly steeper than that of GIP55G (Fig. 4B, P = 0.0023). On the other hand, coincubation with a recombinant dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP IV) led to similar extents of degradation of these peptides (Supplemental Table 7). Thus, the resistance to serum degradation by GIP55G cannot be attributed to a resistance of DPP IV, which represents the major processing enzyme that degrades GIP and GLP-1 in vivo by cleaving these peptides at position 2 of the N terminus (Kim and Egan 2008). These data suggested that the rise in the frequency of GIP103C in Eurasian populations could be associated with the quantitative increase in the overall potency of GIP55G. Although the nature of the selective advantage conferred by the GIP55 peptides is not clear, we speculate that GIP103C could represent a risk allele in ancestors of YRI populations but provide a selective advantage in Eurasians.

Figure 4.

The variation at rs2291725 affects the bioactivity of translated products. (A) GIP55G peptide is resistant to serum degradation. Treatments of GIP receptor-expressing HEK293T cells with GIP, GIP55G or GIP55S led to dose-dependent increases of cAMP production (top left panel). Receptor-activation activities of peptides were also analyzed following incubation with pooled normal human serum for 3, 6, or 12 h. Cells were treated with synthetic peptides for 12 h; the signaling is reported as total cAMP contents in cell lysates. Error bars, SEM of triplicate samples. Significant differences in cAMP production between GIP and GIP55G treatments at a given peptide concentration are indicated by asterisks (P < 0.01). In the control group, cells were treated with an aliquot of human serum without a synthetic peptide. Similar results were observed in three separate experiments. (B) Comparison of the slopes of EC50 trend lines for GIP, GIP55G, and GIP55S after treatments with pooled human serum for the indicated time-spans. The slope of the GIP55G group is significantly different from that of the GIP group (*P = 0.0023).

The derived GIP103C allele arose to dominance in East Asians ∼8100 yr ago

Because energy-balance regulation–related loci are subject to selection pressures that fluctuate over time in response to environmental and culture changes, genetic responses to changes in the human diet are more likely associated with incomplete signatures of selection or even signatures of balancing selection (Charlesworth 2006; Pritchard et al. 2010). Based on this understanding, we speculated that the GIP103C and GIP103T alleles likely confer distinct advantages depending on the history of culture changes (Allison 1956; Turner et al. 1979) and that the selection of GIP103C could occur at a time when humans experienced major shifts in subsistence culture. To investigate this possibility, we estimated the age of the GIP103C-associated haplotype. Under the neutrality, the average age of a polymorphism with the frequency p is estimated to be −4Ne[p(logp)/(1 − p)] (Kimura and Ota 1973; Slatkin and Rannala 2000). With the assumption of Ne = 5000 for each population, this yielded 77,500, 350,000, and 425,000 yr for the derived allele to arise to its current frequencies in the YRI, CEU, and ASN populations, respectively. These estimates are obviously incompatible with the archaeological evidence showing that modern humans originated ∼195 kyr ago in Sub-Saharan Africa and that a first wave of migration to the Arabic peninsula occurred ∼60 to 55 kyr ago, which was followed by migration toward Northern Eurasia ∼40 kya (McDougall et al. 2005; Klein 2009). Consequently, we estimated the age of the GIP103C-associated haplotype on the basis of the decay of haplotypes (Reich 1998; Stephens et al. 1998). Based on a recombination rate derived from estimates of LD of the HapMap data set (McVean et al. 2004), the analysis showed that ASN contains a dominant ancestral haplotype and that the GIP103C-associated haplotypes arose to dominance ∼8100 yr ago in East Asians. Because this dating approach relies on the linkage map derived from estimates of LD, and because discrepancies between LD maps and the pedigree-based recombination maps are significant in many genomic regions (Clark et al. 2010), we also performed the analysis using alternative estimates of recombination rate, which range from 0.5–3.03 cM/Mb in three studies of pedigree-based recombination maps (i.e., deCODE, Marshfield, and Genethon) (Dib et al. 1996; Broman et al. 1998; Kong et al. 2002). Using these recombination rates, we obtained alternative estimates of the age to be between 11,800 and 2000 yr. On the other hand, dating is unattainable for CEU because the ancestral GIP103C haplotype in this population cannot be identified unambiguously, perhaps because that mutation in the region is effectively “saturated” (Supplemental Fig. 6). Given that GIP signaling plays a critical role in the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism, it is plausible that the increased prevalence of the GIP103C allele in Eurasians is a consequence of changes in foraging skills or in population dynamics associated with the emergence of agricultural societies in the Eurasian continent 12,000 to 7000 yr ago (Balter 2007; Fuller et al. 2009; Jones and Liu 2009; Richards and Trinkaus 2009; Gibbons 2010).

Discussion

Based on the gene age estimation and biochemical analyses, our study revealed a functional mutation that is associated with the selection of the GIP locus in East Asian populations ∼8100 yr ago and the presence of a cryptic GIP isoform. Specifically, we showed that the inventory of human GIP peptides has recently diverged and that individuals could express three different combinations of GIP isoforms (GIP, GIP55S, and GIP55G) with distinct bioactivity profiles. Future study of how this phenotypic variation affects glucose and lipid homeostasis in response to different diets and of which physiological variations in humans can be attributed to prior gene–environmental interactions at the GIP locus is crucial to a better understanding of human adaptations in energy-balance regulation.

Taking advantage of the availability of genome information from diverse human populations, recent studies have revealed a number of loci and variants that describe phenotypic variation in appearance, physiological parameters, and pathological responses to diseases (Sabeti et al. 2005; Voight et al. 2006, 2010; Sulem et al. 2007; Tishkoff et al. 2007; Genovese et al. 2010; Gibbons 2010; Leslie 2010; Ng et al. 2010; Simonson et al. 2010). In addition, it has been shown that human genomes contain hundreds of loci that exhibit varying degrees of positive selection (Kelley et al. 2006; Voight et al. 2006; Sabeti et al. 2007; Barreiro et al. 2008; Akey 2009; Cai et al. 2009; Pickrell et al. 2009). These recent in silico findings on gene selection, perhaps due to differential gene–environmental interactions among populations, have opened the doors to human history and a better understanding of the prevalence of adaptations among human populations. However, few causal variants have been confirmed or linked to a phenotype (Akey 2009; Gibbons 2010; Nei et al. 2010). Thus, our finding that the high-frequency GIP103C-associated haplotypes in Eurasian populations are functionally relevant has provided a rare opportunity to better understand the environmental impact on human physiology at the enteroinsular and enteroadipocyte axes. It is generally accepted that a food source represents a potent force that influences selection and adaptive radiation in nature (Darwin 1859; Freeman and Herron 2003). For example, the external differences in beak morphology and speciation of Darwin's finches are believed to be results of adaptations that exploit particular types of seeds, insects, and cactus flowers on the Galápagos Islands (Schluter 2000). Likewise, changes in food source represented one of the most important selection pressures during transitions of human culture and posed a wide spectrum of challenges to the digestive and endocrine systems of our ancestors (Piperno et al. 2004; Balter 2007; Fuller et al. 2009; Jones and Liu 2009; Richards and Trinkaus 2009; Gibbons 2010). For instance, the ability to digest lactose in milk (lactase persistence) and the adoption of a pastoral culture has been linked to the selection of a variety of variants at the lactase locus in multiple ethnic groups at various time points during the last 10 millenniums (Tishkoff et al. 2007; Itan et al. 2009). Similarly, individuals from populations with high-starch diets tend to have more copies of amylases than do those from populations with low-starch diets (Perry et al. 2007). It has long been hypothesized that our ancestors ate a low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet and that the adaptive response was manifested as insulin resistance, perhaps for coping with low dietary glucose (Miller and Colagiuri 1994). Because normal GIP signaling is crucial to normal glucose and lipid metabolism, we speculate that the selection of the GIP103C haplotypes could be pertinent to shifts in long-term energy-balance regulation after the emergence of agriculture, which provided a stable supply of high-starch staples and a reduced need for metabolic efficiency as opposed to the traditional hunter-gatherer societies (Miller and Colagiuri 1994; Wang et al. 2006; Balter 2007; Fuller et al. 2009; Jones and Liu 2009; Richards and Trinkaus 2009; Gibbons 2010; Luca et al. 2010; Richerson et al. 2010).

It was hypothesized by Neel almost 50 yr ago that mismatches between prior physiological adaptations and contemporary environments can lead to health risks because the ancestral variants that have been selected for the organism's fitness or reproductive success may not be optimal for the individual's health in the new environment (Neel 1962). In support of this thrifty genotype hypothesis, a number of genes in humans and house mice have been implied to have coevolved with the emergence of agricultural societies (Prentice et al. 2005; Vander Molen et al. 2005; Shiao et al. 2008), and a rapid shift in diets is associated with the detrimental effects on human survival in a number of human populations (Anonymous 1989). Conceptually, the serum-resistant GIP55G carried by the GIP103C haplotype may have been beneficial for individuals who have unconstrained access to the food supply in many agricultural societies by preventing severe hyperglycemia. As selection pressure changed in these societies, the ancient GIP103T haplotype could have become a liability and conferred a loss of fitness in the new environment. In addition, we speculate that the selection of GIP in East Asians may contribute to the heterogeneity in the risk of diabetes among major ethnic groups at the present time (Retnakaran et al. 2006; Nystrom et al. 2008; Ma and Chan 2009). Importantly, regardless of what the selection pressure might have been, our study indicated that the GIP locus was susceptible to recent changes in human environment and that the physiological variation stemming from this selection could bear important implications for understanding the phenotypic variation of metabolic syndromes such as diabetes and obesity. Nonetheless, it is important to note that the selection of the derived GIP103C haplotypes could be a consequence of the coordinated actions of multiple SNPs at the GIP locus. Future analysis of the functionality of rs2291725 and linked SNPs is needed to elucidate the exact nature of the selection of GIP103C haplotypes in the last 10 millenniums.

Taken together, our study has highlighted an unexpected complexity in the regulation of sugar and lipid metabolism among human populations; it has also illuminated the importance of understanding adaptations in genes associated with energy-balance regulation in the face of ongoing changes in our diets toward refined and high-energy convenience food as well as the emerging pandemics of diabetes and obesity in modern society.

Methods

Genotype analysis

FST estimation and LD plot

The selected loci that have rapidly increased in frequency due to local positive selection are likely to show high levels of genetic differentiation, which can be quantified with the FST statistic (Lewontin and Krakauer 1973; Weir 1996). The principle of a number of estimators of FST is FST = (HT − HS)/HT, where HT is the heterozygosity of the total population and HS is the average heterozygosity across subpopulations. The empirical distribution of FST or the average of FST over multilocus windows for the genome-wide polymorphism data has been used to detect the genomic regions under positive selection (Akey et al. 2002). We computed the FST for all nonsynonymous SNPs in the HapMap Project phases I and II, and the function snp_fst.m in PGEToolbox (Cai 2008) was used to calculate and present an unbiased estimate of FST.

LD plots for SNPs within the CALCOCO2, ATP5G1, UBE2Z, SNF8, GIP, and IGF2BP1 gene regions from rs1422645 to rs8069452, spanning 200 kb, were generated using HaploView 4.1 (Barrett et al. 2005). The LD blocks were determined using an r2 threshold of 0.8.

Analysis of EHH and iHS

The EHH plots were generated as described (Voight et al. 2006). We also computed the EHH statistic for the core SNP (rs2291725) as previously described (Sabeti et al. 2002). The EHH curve measures the decay of identity of haplotypes that carry the core SNP as a function of distance. When an allele rises rapidly in frequency due to strong selection, it tends to exhibit high levels of haplotype homozygosity, extending further than expected under a neutral model. For the analysis of EHH decay, haplotypes in the genomic region that encompasses a 750-kb region centered on the GIP gene and contains 388 phased SNPs were downloaded from the HapMap project website.

The iHS statistic detects whether the area under the EHH curve is greater for a selected allele than for a neutral allele (Voight et al. 2006). Large negative values indicate unusually long haplotypes carrying the derived allele. To test whether the observed iHS for rs2291725 is significantly deviated from the expected values derived from neutral evolution, we used a coalescent model and generated 10,000 replicated haplotype sets using the coalescent simulator ms (Hudson 2002). We adopted parameters that are compatible with the sample size (180 chromosomes) of the ASN population and the length of genomic region (750 kb) that was analyzed. The simulation was conditioned based on recombination rate = 9.7 × 10−7 cM/bp, N0 = 10,000, and number of segregating sites = 388. We also required that each replicate contain at least one segregating site in which the derived allele frequency reaches ∼0.75 and that the site is located in the center of the haplotype (that is, between a 370- and 380-kb area of the 750-kb region in total). With these conditions, we found no iHS value for a simulated data set to be more negative than the observed iHS (empirical P < 1 × 10−4) (Supplemental Fig. 4A).

Estimation of the age of GIP103C haplotype

Under positive selection, a derived, or novel, allele can quickly rise to a high frequency. As the allele ages, recombination causes the breakdown of the LD within the existing linked alleles, and mutation leads to the accumulation of new linked variations. The allele's age can be estimated by the decay of the haplotype carrying the allele (Stephens et al. 1998). The length of the haplotype retained between different copies of the allele shortens over time due to recombination and mutation, which is modeled using a Poisson process by Reich and Goldstein (1999). The probability that a haplotype remains ancestral (i.e., that the haplotype that carries the derived allele retains the status of high frequency right after being selected) is P = e−G(r+u), where G is generations, r is the recombination rate, and u is the mutation rate. For a given allele in the derived haplotype, the haplotype-decay approach estimates the number of generations G in terms of P (the probability that a given haplotype does not change from its ancestor) (Stephens et al. 1998; Reich and Goldstein 1999).

In ASN, the GIP LD block is 91 kb long and contains eight distinct haplotypes (1–8 from top to bottom in Supplemental Fig. 6). Haplotypes 1–4 are GIP103C associated and are derived. Among these derived haplotypes, haplotype 1 is apparently the ancestral haplotype from which haplotypes 2–4 were derived. The frequency of haplotype 1 in GIP103C-associated haplotypes is P′ = 0.803. We obtained the recombination rate derived from estimates of LD (McVean et al. 2004) from the website of the HapMap project (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Regression analysis with data points of different physical lengths versus genetic map lengths gave the regression function: y = 0.93x − 0.018, where x is the physical distance (Mb) and y is the genetic distance (cM). The genetic distance of the 91-kb region was estimated to be 0.0666 cM (i.e., 0.0666% chance of crossing over in a single generation), which gives a rate of recombination r = 6.66 × 10−4 per generation. We took the mutation rate of the region u = 1.0 × 10−5, based on an estimation of the haploid mutation rate of ∼1.1 × 10−8 per base per generation (Roach et al. 2010). We assumed that the most common haplotype is the ancestral haplotype and used P′ obtained above as an approximation of P. Using G = −ln(P′)/(r + u), we obtained G = 325 (or 8100 yr).

Phenotype tests

Reagents

Synthetic GIP peptides were obtained from Genescript and the American Peptide Company. The extended GIP55G and GIP55S isoforms were synthesized by the Stanford University PAN facility and GL Biochem. Pooled normal human serum, pooled complement-preserved human serum, and serum from individuals were obtained from Innovative Research and ProteoGenex. Stocks of different hormones were prepared in phosphate-buffered saline and diluted in a serum-free culture medium. In addition to routine chemistry and mass-spectrometry assessments, we verified the quantity of different GIP isoforms using a human GIP enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Linco Research).

Immunohistochemical analyses and ELISA

Total GIP levels in human serums were measured using a sandwich human GIP ELISA kit (Linco Research), and assays were performed with a programmable ELISA plate washer. The minimum detection limit of the assay was 8.1 pg/mL. For the measurement of GIP55, human serums were partially purified with C18 chromatography, and the secondary antibody of the human GIP ELISA kit was substituted with a rabbit polyclonal antibody specific for the last 13 amino acids of GIP55 (REARALELASQAN). The GIP55-specific antibodies were generated using a KLH-conjugated CREARALELASQAN peptide (Covance Research Products and Genescript).

For immunohistochemical analyses, human duodenum sections (BioChain Institute) were dewaxed with xylene and maintained for 10 min at 95°C–99°C in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0), followed by cooling on the bench top. Sections were immunostained with a mouse monoclonal anti-GIP antibody (Abbiotec) and a rabbit GIP55-specific antibody overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Signals for GIP and GIP55 were detected using an Alexa 488 donkey anti-mouse antibody (488 nm, 1:2500 dilution) and a Texas Red-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (594 nm, 1:500 dilution), respectively, with a Leica SP2 single- and multi-photon confocal microscope.

The in vivo glucose suppression assay

Eight-week-old Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Inc., Wilmington, MA) were fasted overnight for 20 h. To measure the GIP isoforms' ability to reduce blood glucose levels in vivo, fasting rats were injected with a select GIP peptide (100 nmol/kg) dissolved in 0.8 mL of PBS together with glucose (3.8 g/kg body weight). Blood samples were obtained via the tail vein at select time points after the intraperitoneal injection of glucose and the peptide. Glucose levels in the blood were measured with a OneTouch Ultra Blood Glucose Monitoring System and OneTouch Ultra Test Strips (Johnson and Johnson).

Receptor-activation assay

The expression vector for the human GIP receptor (Origene) was transfected into HEK293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Receptor-activation activities were assayed based on cAMP production in transfected cells and were performed as described (Park et al. 2008; Chang et al. 2010). To quantify resistance to serum degradation by GIP isoforms, aliquots of GIP peptides were incubated in microfuges at 37°C with human serum in a final concentration of 10 μM for indicated time spans. To analyze the mechanism underlying the serum-degradation–resistant property of GIP55, peptides (10 μM) were preincubated with a recombinant human DPP IV (1 mU/mL reaction in PBS; Enzo Life Science) for 3, 6, or 12 h and were frozen at −80°C before being tested for receptor-activation activity. The receptor-activation results were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 5 package (GraphPad Software).

Acknowledgments

We thank Yi Wei and Augustin Sanchez (Stanford University Pan Facility) for technical assistance. We thank Drs. Aaron J.W. Hsueh and Renee A. Reijo Pera (Department of OB/GYN, Stanford University) for the critical review of the manuscript, and C.L.C. further thanks Dr. Yung-Kuei Soong (Department of OB/GYN, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan). J.J.C. thanks Dr. Dmitri Petrov (Dept. of Biology, Stanford University) for his invaluable advice and long-lasting support. We acknowledge the support of NIH (DK70652, SYTH), Avon Foundation (02-2009-054, SYTH), and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CMRPG34002, CLC).

Author contributions: S.Y.T.H. conceived and supervised the study. C.L.C., J.P., and S.Y.T.H. were involved in functional testing and data analyses. J.J.C., C.L., and J.A. processed and performed genome data analyses. The paper was written primarily by C.L.C., J.J.C., and S.Y.T.H.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available online at http://www.genome.org.]

Article published online before print. Article and publication date are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.110593.110.

References

- Akey JM 2009. Constructing genomic maps of positive selection in humans: Where do we go from here? Genome Res 19: 711–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akey JM, Zhang G, Zhang K, Jin L, Shriver MD 2002. Interrogating a high-density SNP map for signatures of natural selection. Genome Res 12: 1805–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison AC 1956. The sickle-cell and haemoglobin C genes in some African populations. Ann Hum Genet 21: 67–89 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amigo J, Salas A, Phillips C, Carracedo A 2008. SPSmart: Adapting population based SNP genotype databases for fast and comprehensive web access. BMC Bioinformatics 9: 428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson TM, vonHoldt BM, Candille SI, Musiani M, Greco C, Stahler DR, Smith DW, Padhukasahasram B, Randi E, Leonard JA, et al. 2009. Molecular and evolutionary history of melanism in North American gray wolves. Science 323: 1339–1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous 1989. Thrifty genotype rendered detrimental by progress? Lancet 2: 839–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balter M 2007. Plant science. Seeking agriculture's ancient roots. Science 316: 1830–1835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro LB, Quintana-Murci L 2010. From evolutionary genetics to human immunology: How selection shapes host defence genes. Nat Rev Genet 11: 17–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro LB, Laval G, Quach H, Patin E, Quintana-Murci L 2008. Natural selection has driven population differentiation in modern humans. Nat Genet 40: 340–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ 2005. Haploview: Analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 21: 263–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo I, Yu Hsu S, Rauch R, Kowalski HW, Hsueh AJ 2003. Signaling receptome: A genomic and evolutionary perspective of plasma membrane receptors involved in signal transduction. Sci STKE 203: RE9 doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.187.re9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman KW, Murray JC, Sheffield VC, White RL, Weber JL 1998. Comprehensive human genetic maps: Individual and sex-specific variation in recombination. Am J Hum Genet 63: 861–869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk J, Hardouin E, Pugach I, Hughes D, Strotmann R, Stoneking M, Myles S 2008. Positive selection in East Asians for an EDAR allele that enhances NF-κB activation. PLoS ONE 3: e2209 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan TA, Xiang AH 2005. Gestational diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 115: 485–491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai JJ 2008. PGEToolbox: A Matlab toolbox for population genetics and evolution. J Hered 99: 438–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai JJ, Macpherson JM, Sella G, Petrov DA 2009. Pervasive hitchhiking at coding and regulatory sites in humans. PLoS Genet 5: e1000336 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cann HM, de Toma C, Cazes L, Legrand MF, Morel V, Piouffre L, Bodmer J, Bodmer WF, Bonne-Tamir B, Cambon-Thomsen A, et al. 2002. A human genome diversity cell line panel. Science 296: 261–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers JC, Elliott P, Zabaneh D, Zhang W, Li Y, Froguel P, Balding D, Scott J, Kooner JS 2008. Common genetic variation near MC4R is associated with waist circumference and insulin resistance. Nat Genet 40: 716–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CL, Park J-I, Hsu SYT 2010. Activation of calcitonin receptor and calcitonin receptor-like receptor by membrane-anchored ligands. J Biol Chem 285: 1075–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth D 2006. Balancing selection and its effects on sequences in nearby genome regions. PLoS Genet 2: e64 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Patterson N, Reich D 2010. Population differentiation as a test for selective sweeps. Genome Res 20: 393–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia CW, Carlson OD, Kim W, Shin YK, Charles CP, Kim HS, Melvin DL, Egan JM 2009. Exogenous glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide worsens post prandial hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 58: 1342–1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AG, Wang X, Matise T 2010. Contrasting methods of quantifying fine structure of human recombination. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 11: 45–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C 1859. On the origin of species by means of natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life. John Murray, London: [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dib C, Faure S, Fizames C, Samson D, Drouot N, Vignal A, Millasseau P, Marc S, Hazan J, Seboun E, et al. 1996. A comprehensive genetic map of the human genome based on 5,264 microsatellites. Nature 380: 152–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drews J 2000. Drug discovery: A historical perspective. Science 287: 1960–1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman S, Herron JC 2003. Evolutionary analysis, 3rd ed Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto A, Kimura R, Ohashi J, Omi K, Yuliwulandari R, Batubara L, Mustofa MS, Samakkarn U, Settheetham-Ishida W, Ishida T, et al. 2008. A scan for genetic determinants of human hair morphology: EDAR is associated with Asian hair thickness. Hum Mol Genet 17: 835–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DQ, Qin L, Zheng Y, Zhao Z, Chen X, Hosoya LA, Sun GP 2009. The domestication process and domestication rate in rice: Spikelet bases from the Lower Yangtze. Science 323: 1607–1610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulurija A, Lutz TA, Sladko K, Osto M, Wielinga PY, Bachmann MF, Saudan P 2008. Vaccination against GIP for the treatment of obesity. PLoS ONE 3: e3163 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, Lecordier L, Uzureau P, Freedman BI, Bowden DW, Langefeld CD, Oleksyk TK, Uscinski Knob AL, et al. 2010. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science 329: 841–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons A 2010. Human evolution. Tracing evolution's recent fingerprints. Science 329: 740–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gniuli D, Calcagno A, Dalla Libera L, Calvani R, Leccesi L, Caristo ME, Vettor R, Castagneto M, Ghirlanda G, Mingrone G 2010. High-fat feeding stimulates endocrine, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)-expressing cell hyperplasia in the duodenum of Wistar rats. Diabetologia 53: 2233–2240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutenkunst RN, Hernandez RD, Williamson SH, Bustamante CD 2009. Inferring the joint demographic history of multiple populations from multidimensional SNP frequency data. PLoS Genet 5: e1000695 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellenthal G, Stephens M 2007. msHOT: Modifying Hudson's ms simulator to incorporate crossover and gene conversion hotspots. Bioinformatics 23: 520–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra HE, Hirschmann RJ, Bundey RA, Insel PA, Crossland JP 2006. A single amino acid mutation contributes to adaptive beach mouse color pattern. Science 313: 101–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RR 2002. Generating samples under a Wright-Fisher neutral model of genetic variation. Bioinformatics 18: 337–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingelsson E, Langenberg C, Hivert MF, Prokopenko I, Lyssenko V, Dupuis J, Magi R, Sharp S, Jackson AU, Assimes TL, et al. 2010. Detailed physiologic characterization reveals diverse mechanisms for novel genetic Loci regulating glucose and insulin metabolism in humans. Diabetes 59: 1266–1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International HapMap Consortium 2007. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature 449: 851–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International HapMap Project 2003. The International HapMap Project. Nature 426: 789–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isken F, Pfeiffer AF, Nogueiras R, Osterhoff MA, Ristow M, Thorens B, Tschop MH, Weickert MO 2008. Deficiency of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor prevents ovariectomy-induced obesity in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E350–E355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itan Y, Powell A, Beaumont MA, Burger J, Thomas MG 2009. The origins of lactase persistence in Europe. PLoS Comput Biol 5: e1000491 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MK, Liu X 2009. Archaeology. Origins of agriculture in East Asia. Science 324: 730–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley JL, Madeoy J, Calhoun JC, Swanson W, Akey JM 2006. Genomic signatures of positive selection in humans and the limits of outlier approaches. Genome Res 16: 980–989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W, Egan JM 2008. The role of incretins in glucose homeostasis and diabetes treatment. Pharmacol Rev 60: 470–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M, Ota T 1973. The age of a neutral mutant persisting in a finite population. Genetics 75: 199–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RG 2009. Darwin and the recent African origin of modern humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 16007–16009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong A, Gudbjartsson DF, Sainz J, Jonsdottir GM, Gudjonsson SA, Richardsson B, Sigurdardottir S, Barnard J, Hallbeck B, Masson G, et al. 2002. A high-resolution recombination map of the human genome. Nat Genet 31: 241–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laland KN, Odling-Smee J, Myles S 2010. How culture shaped the human genome: Bringing genetics and the human sciences together. Nat Rev Genet 11: 137–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalueza-Fox C, Rompler H, Caramelli D, Staubert C, Catalano G, Hughes D, Rohland N, Pilli E, Longo L, Condemi S, et al. 2007. A melanocortin 1 receptor allele suggests varying pigmentation among Neanderthals. Science 318: 1453–1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie M 2010. Genetics. Kidney disease is parasite-slaying protein's downside. Science 329: 263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin RC, Krakauer J 1973. Distribution of gene frequency as a test of the theory of the selective neutrality of polymorphisms. Genetics 74: 175–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JZ, Absher DM, Tang H, Southwick AM, Casto AM, Ramachandran S, Cann HM, Barsh GS, Feldman M, Cavalli-Sforza LL, et al. 2008. Worldwide human relationships inferred from genome-wide patterns of variation. Science 319: 1100–1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luca F, Perry GH, di Rienzo A 2010. Evolutionary adaptations to dietary changes. Annu Rev Nutr 30: 291–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma RC, Chan JC 2009. Pregnancy and diabetes scenario around the world: China. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 104: S42–S45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClean PL, Irwin N, Cassidy RS, Holst JJ, Gault VA, Flatt PR 2007. GIP receptor antagonism reverses obesity, insulin resistance, and associated metabolic disturbances induced in mice by prolonged consumption of high-fat diet. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E1746–E1755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougall I, Brown FH, Fleagle JG 2005. Stratigraphic placement and age of modern humans from Kibish, Ethiopia. Nature 433: 733–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVean GA, Myers SR, Hunt S, Deloukas P, Bentley DR, Donnelly P 2004. The fine-scale structure of recombination rate variation in the human genome. Science 304: 581–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JC, Colagiuri S 1994. The carnivore connection: Dietary carbohydrate in the evolution of NIDDM. Diabetologia 37: 1280–1286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki K, Yamada Y, Ban N, Ihara Y, Tsukiyama K, Zhou H, Fujimoto S, Oku A, Tsuda K, Toyokuni S, et al. 2002. Inhibition of gastric inhibitory polypeptide signaling prevents obesity. Nat Med 8: 738–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody AJ, Thim L, Valverde I 1984. The isolation and sequencing of human gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP). FEBS Lett 172: 142–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neel JV 1962. Diabetes mellitus: A “thrifty” genotype rendered detrimental by “progress”? Am J Hum Genet 14: 353–362 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M, Suzuki Y, Nozawa M 2010. The neutral theory of molecular evolution in the genomic era. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 11: 265–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng SB, Bigham AW, Buckingham KJ, Hannibal MC, McMillin MJ, Gildersleeve HI, Beck AE, Tabor HK, Cooper GM, Mefford HC, et al. 2010. Exome sequencing identifies MLL2 mutations as a cause of Kabuki syndrome. Nat Genet 42: 790–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen R, Hellmann I, Hubisz M, Bustamante C, Clark AG 2007. Recent and ongoing selection in the human genome. Nat Rev Genet 8: 857–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystrom MJ, Caughey AB, Lyell DJ, Druzin ML, El-Sayed YY 2008. Perinatal outcomes among Asian-white interracial couples. Am J Obstet Gynecol 199: 385 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JI, Semyonov J, Chang CL, Yi W, Warren W, Hsu SY 2008. Origin of INSL3-mediated testicular descent in therian mammals. Genome Res 18: 974–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry GH, Dominy NJ, Claw KG, Lee AS, Fiegler H, Redon R, Werner J, Villanea FA, Mountain JL, Misra R, et al. 2007. Diet and the evolution of human amylase gene copy number variation. Nat Genet 39: 1256–1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickrell JK, Coop G, Novembre J, Kudaravalli S, Li JZ, Absher D, Srinivasan BS, Barsh GS, Myers RM, Feldman MW, et al. 2009. Signals of recent positive selection in a worldwide sample of human populations. Genome Res 19: 826–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piperno DR, Weiss E, Holst I, Nadel D 2004. Processing of wild cereal grains in the Upper Palaeolithic revealed by starch grain analysis. Nature 430: 670–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice AM, Rayco-Solon P, Moore SE 2005. Insights from the developing world: Thrifty genotypes and thrifty phenotypes. Proc Nutr Soc 64: 153–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard JK, Pickrell JK, Coop G 2010. The genetics of human adaptation: Hard sweeps, soft sweeps, and polygenic adaptation. Curr Biol 20: R208–R215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokopenko I, McCarthy MI, Lindgren CM 2008. Type 2 diabetes: New genes, new understanding. Trends Genet 24: 613–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich DE 1998. Estimating the age of mutations using variation at linked markers. In Microsatellites: Evolution and applications, pp. 129–138 Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- Reich DE, Goldstein DB 1999. Estimating the age of mutations using variation at linked markers. In Microsatellites: Evolution and applications, (ed. Goldstein DB and Schlotterer C), pp. 129–138 Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- Retnakaran R, Hanley AJ, Connelly PW, Sermer M, Zinman B 2006. Ethnicity modifies the effect of obesity on insulin resistance in pregnancy: A comparison of Asian, South Asian, and Caucasian women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91: 93–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards MP, Trinkaus E 2009. Out of Africa: Modern human origins special feature: Isotopic evidence for the diets of European Neanderthals and early modern humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 16034–16039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richerson PJ, Boyd R, Henrich J 2010. Colloquium paper: Gene-culture coevolution in the age of genomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 8985–8992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach JC, Glusman G, Smit AF, Huff CD, Hubley R, Shannon PT, Rowen L, Pant KP, Goodman N, Bamshad M, et al. 2010. Analysis of genetic inheritance in a family quartet by whole-genome sequencing. Science 328: 636–639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg NA 2006. Standardized subsets of the HGDP-CEPH Human Genome Diversity Cell Line Panel, accounting for atypical and duplicated samples and pairs of close relatives. Ann Hum Genet 70: 841–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeti PC, Reich DE, Higgins JM, Levine HZ, Richter DJ, Schaffner SF, Gabriel SB, Platko JV, Patterson NJ, McDonald GJ, et al. 2002. Detecting recent positive selection in the human genome from haplotype structure. Nature 419: 832–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeti PC, Walsh E, Schaffner SF, Varilly P, Fry B, Hutcheson HB, Cullen M, Mikkelsen TS, Roy J, Patterson N, et al. 2005. The case for selection at CCR5-Delta32. PLoS Biol 3: e378 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabeti PC, Varilly P, Fry B, Lohmueller J, Hostetter E, Cotsapas C, Xie X, Byrne EH, McCarroll SA, Gaudet R, et al. 2007. Genome-wide detection and characterization of positive selection in human populations. Nature 449: 913–918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena R, Hivert MF, Langenberg C, Tanaka T, Pankow JS, Vollenweider P, Lyssenko V, Bouatia-Naji N, Dupuis J, Jackson AU, et al. 2010. Genetic variation in GIPR influences the glucose and insulin responses to an oral glucose challenge. Nat Genet 42: 142–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluter D 2000. The ecology of adaptive radiation. Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- Seminara SB, Messager S, Chatzidaki EE, Thresher RR, Acierno JS Jr, Shagoury JK, Bo-Abbas Y, Kuohung W, Schwinof KM, Hendrick AG, et al. 2003. The GPR54 gene as a regulator of puberty. N Engl J Med 349: 1614–1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semyonov J, Park JI, Chang CL, Hsu SY 2008. GPCR genes are preferentially retained after whole genome duplication. PLoS ONE 3: e1903 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiao MS, Liao BY, Long M, Yu HT 2008. Adaptive evolution of the insulin two-gene system in mouse. Genetics 178: 1683–1691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura Y, Wajid M, Ishii Y, Shapiro L, Petukhova L, Gordon D, Christiano AM 2008. Disruption of P2RY5, an orphan G protein-coupled receptor, underlies autosomal recessive woolly hair. Nat Genet 40: 335–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonson TS, Yang Y, Huff CD, Yun H, Qin G, Witherspoon DJ, Bai Z, Lorenzo FR, Xing J, Jorde LB, et al. 2010. Genetic evidence for high-altitude adaptation in Tibet. Science 329: 72–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin M, Rannala B 2000. Estimating allele age. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 1: 225–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JM, Haigh J 1974. The hitch-hiking effect of a favourable gene. Genet Res 23: 23–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens JC, Reich DE, Goldstein DB, Shin HD, Smith MW, Carrington M, Winkler C, Huttley GA, Allikmets R, Schriml L, et al. 1998. Dating the origin of the CCR5-Delta32 AIDS-resistance allele by the coalescence of haplotypes. Am J Hum Genet 62: 1507–1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulem P, Gudbjartsson DF, Stacey SN, Helgason A, Rafnar T, Magnusson KP, Manolescu A, Karason A, Palsson A, Thorleifsson G, et al. 2007. Genetic determinants of hair, eye and skin pigmentation in Europeans. Nat Genet 39: 1443–1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda J, Seino Y, Tanaka K, Fukumoto H, Kayano T, Takahashi H, Mitani T, Kurono M, Suzuki T, Tobe T, et al. 1987. Sequence of an intestinal cDNA encoding human gastric inhibitory polypeptide precursor. Proc Natl Acad Sci 84: 7005–7008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tishkoff SA, Reed FA, Ranciaro A, Voight BF, Babbitt CC, Silverman JS, Powell K, Mortensen HM, Hirbo JB, Osman M, et al. 2007. Convergent adaptation of human lactase persistence in Africa and Europe. Nat Genet 39: 31–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topaloglu AK, Reimann F, Guclu M, Yalin AS, Kotan LD, Porter KM, Serin A, Mungan NO, Cook JR, Ozbek MN, et al. 2009. TAC3 and TACR3 mutations in familial hypogonadotropic hypogonadism reveal a key role for Neurokinin B in the central control of reproduction. Nat Genet 41: 354–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JR, Johnson MS, Eanes WF 1979. Contrasted modes of evolution in the same genome: Allozymes and adaptive change in Heliconius. Proc Natl Acad Sci 76: 1924–1928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Molen J, Frisse LM, Fullerton SM, Qian Y, Del Bosque-Plata L, Hudson RR, Di Rienzo A 2005. Population genetics of CAPN10 and GPR35: Implications for the evolution of type 2 diabetes variants. Am J Hum Genet 76: 548–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voight BF, Kudaravalli S, Wen X, Pritchard JK 2006. A map of recent positive selection in the human genome. PLoS Biol 4: e72 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voight BF, Scott LJ, Steinthorsdottir V, Morris AP, Dina C, Welch RP, Zeggini E, Huth C, Aulchenko YS, Thorleifsson G, et al. 2010. Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nat Genet 42: 579–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ET, Kodama G, Baldi P, Moyzis RK 2006. Global landscape of recent inferred Darwinian selection for Homo sapiens. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 135–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir BS 1996. Genetic data analysis II: Methods for discrete population genetic data. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland [Google Scholar]

- Yi X, Liang Y, Huerta-Sanchez E, Jin X, Cuo ZX, Pool JE, Xu X, Jiang H, Vinckenbosch N, Korneliussen TS, et al. 2010. Sequencing of 50 human exomes reveals adaptation to high altitude. Science 329: 75–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]