Abstract

Objective

Cancer and treatments for cancer affect specific aspects of sexual functioning and intimacy; however, limited qualitative work has been done in diverse cancer populations. As part of an effort to improve measurement of self-reported sexual functioning, we explored the scope and importance of sexual functioning and intimacy to patients across cancer sites and along the continuum of care.

Methods

We conducted 16 diagnosis- and sex-specific focus groups with patients recruited from the Duke University tumor registry and oncology/hematology clinics (N=109). A trained note taker produced field notes summarizing the discussions. An independent auditor verified field notes against written transcripts. The content of the discussions was analyzed for major themes by two independent coders.

Results

Across all cancers, the most commonly discussed cancer- or treatment-related effects on sexual functioning and intimacy were fatigue, treatment-related hair loss, weight gain, and organ loss or scarring. Additional barriers were unique to particular diagnoses, such as shortness of breath in lung cancer, gastrointestinal problems in colorectal cancers, and incontinence in prostate cancer. Sexual functioning and intimacy were considered important to quality of life. While most effects of cancer were considered negative, many participants identified improvements to intimacy after cancer.

Conclusion

Overall evaluations of satisfaction with sex life did not always correspond to specific aspects of functioning (e.g. erectile dysfunction), presenting a challenge to researchers aiming to measure sexual functioning as an outcome. Health care providers should not assume that level of sexual impairment determines sexual satisfaction and should explore cancer patients’ sexual concerns directly.

Keywords: Cancer; Focus Groups; Oncology; Qualitative Research; Quality of Life; Sexual Function, Intimacy

Introduction

Cancer and its treatments frequently affect sexual functioning and intimacy [1-5]. Across cancer types, estimates of sexual dysfunction after treatment range from 40% to 100% and involve many causes [6]. Common physical difficulties include achieving and sustaining intercourse (eg, erectile dysfunction in men [7], pain with intercourse in women [5]) and loss of sexual sensations [4]. Psychological effects can shape patients’ feelings of desirability [2,4], which is related to one of the most common sexual problems, loss of desire for sexual activity [6]. Patients’ sexual functioning and sexual identity can be affected even when no outward change in appearance is visible and when the cancer does not directly affect sexual physiology [5,7-12].

Cancer-related sexual dysfunction is a concern along the treatment trajectory. Sexual problems may develop at any point during the disease course, including at diagnosis, during treatment, and after active treatment during post-treatment follow-up [13]. Sexuality and body image are concerns for patients at all stages of disease progression [14]. Unlike many other side effects of cancer treatment, sexual problems commonly do not resolve in the first 2 years of disease-free survival but may remain constant and relatively severe [6].

Development of a comprehensive, self-reported measure of sexual functioning for use with cancer populations is important for several reasons. Measures developed and validated for use in non-cancer populations may not be valid for cancer patients because some aspects of sexual difficulties may be unique to cancer populations, such as effects of particular chemotherapeutic agents or surgeries. As a result, there is a need to better characterize the nature of sexual difficulties in cancer patients and to develop patient-reported tools that are validated in this population. A recent review of the literature on sexual function measures used in cancer populations found 257 articles that reported the administration of 31 psychometrically evaluated sexual function measures to individuals who were diagnosed with cancer, but most had not been tested widely in cancer populations [15]. This review supports the need for a flexible, psychometrically robust measure of sexual function for use in oncology settings.

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS™) Network (http://www.nihpromis.org/) is a collaborative effort of seven research universities and the National Institutes of Health to advance the measurement of patient-reported outcomes using state-of-the-art psychometric and computer-adaptive techniques. To enhance the relevance of the PROMIS measures for patients with cancer and support the development of a measure of sexual functioning, the National Cancer Institute formed a multi-site domain committee consisting of sexual function experts, oncologists, psychiatrists, psychologists, outcomes researchers, and qualitative and quantitative methodologists. As a first step, the domain group sought to understand the nature, scope, and importance of sexuality and intimacy from the perspectives of patients who varied in terms of cancer site, treatment type, treatment trajectory, and comorbid conditions. Following PROMIS procedures for measure development [16-18], we collected these patient perspectives using focus group methodology. The results were then used to inform the development of a conceptual model for the PROMIS Sexual Function measure for cancer patients.

Methods

Study design

We recruited focus group participants via mailed invitation to patients in the Duke tumor registry and in-person at the Duke Comprehensive Cancer Center. Eligible participants were aged 18 years or older, had been diagnosed with cancer, and were able to speak English. The purposive sampling strategy aimed for representation with regard to tumor site, treatment trajectory (i.e., newly diagnosed, undergoing treatment, or in post-treatment follow-up), sex, race, and education level. Approval from the treating oncologist was obtained prior to approaching patients for participation.

We organized a total of 16 focus groups, and each group had four to 12 scheduled participants. Eleven of the groups included patients who were newly diagnosed or currently undergoing treatment for breast, prostate, lung, colorectal, gynecological, or other cancers of any kind. Another five focus groups included participants who were in post-treatment follow-up for breast, prostate, and gynecological cancers. We were unable to recruit enough lung and colorectal patients in the post-treatment phase to conduct separate focus groups in these diseases. All groups were conducted separately by sex. Participants were compensated $75 and given a light dinner. The institutional review board of the Duke University Health System approved the study.

Focus group sessions lasted about 90 minutes. Professional focus group moderators (of the same sex as participants) led discussions by following a semistructured interview guide developed by the domain committee, which was based on our literature review and clinical experience.

After reviewing data from the first four groups (active and post treatment breast and prostate) we expanded the discussion guide to include more detailed probes of important issues that arose in the groups. With revisions in italics, the guides addressed: 1) the scope and importance of issues related to physical intimacy and sexuality to patients with cancer, 2) the physical impact of cancer on distinct stages of sexual function (e.g., desire, arousal, intercourse, orgasm), 3) the psychosocial impact of cancer on intimate relationships and body image, and 4) for focus groups with participants younger than 50 years old, effects on fertility. Sample questions from the discussion guide are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Focus Group Questions

|

Scope and Importance

| |

| 1 | What are some of the ways cancer and treatments for cancer affect physical intimacy or sexuality? |

| 2 | How important a topic is this? |

| 3 | How difficult is it for you to talk about this issue? |

| 4 | How much do changes in sexuality affect overall quality-of-life? |

|

| |

|

Physical Impact

| |

| 5 | Engaging in sexual activity requires a lot of different body parts to work and work together. In what ways does cancer or its treatments affect the way the body functions in sexual activity? |

| 6 | How does cancer or its treatments change the way in which people’s bodies prepare for sex? |

| 7 | What about any problems reaching orgasm? |

|

| |

|

Psychosocial Impact

| |

| 8 | What changes in an intimate relationship when someone is diagnosed with cancer? |

| 9 | Are there additional worries about being in a sexual relationship for people with cancer? |

| 10 | How does affectionate behavior change? |

| 11 | How about any changes in how you think about your own body? |

| 12 | Does having cancer change how you see yourself as a [woman/man]? |

|

| |

|

Fertility (for groups with participants < age 50

| |

| 13 | Do you worry about your ability to have children as a result of cancer or its treatments? |

| 14 | If yes, does this worry have anything to do with your sex life or is it separate? |

|

| |

|

Wrap-up

| |

| 15 | Is there anything else that you think would be helpful for the researchers to know about cancer or how someone with cancer feels about changes in physical intimacy or sexuality? |

| 16 | When you think about the issues we discussed, which ones are most important to you? |

| 17 | How significant are these changes compared to other issues or priorities in your life now? |

| 18 | How do you cope or manage the symptoms related to sexuality that we have discussed? |

All focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed. A member of the domain committee observed all groups and produced summaries of the themes covered as well as reported on non-verbal dynamics. An independent auditor verified a randomly selected 50% sample of the summaries against the transcripts. The domain committee reviewed these summaries to determine whether any focus group should be repeated to achieve data saturation. We found no new themes after 11 focus groups with patients in active treatment and 5 focus groups with patient in post-treatment follow-up, suggesting that we had achieved data saturation.

Analysis

The goal of the focus groups was to develop a qualitative summary of sexual functioning during and after the diagnosis and treatment of cancer and to examine the impact of sexual functioning on quality of life. The regular content review of focus group field notes by the domain committee allowed for continuous refinement of our conceptual measurement model, and this model was used to guide coding. Two trained assistants independently coded the field notes, meeting regularly with another member of the domain committee to resolve disagreements in coding and to inductively categorize themes that did not fit the preliminary coding structure. Thus, the preliminary coding scheme was iteratively revised based on participant contributions. Inter-rater agreement on themes covered was 91%. In addition to describing the themes found, we report on the occurrence of each theme at the focus group level. Quotations offered by participants are provided to illustrate the themes that emerged during the focus group discussions.

Results

Table 2 shows the demographic and disease characteristics of the focus group participants. There were more female than male participants (due to the composition of targeted groups by diagnosis). There was broad representation across treatment trajectory, cancer sites, and age. We did not ask participants about sexual orientation; however, two female participants shared that they were lesbian or bisexual. Participants had experienced a wide variety of treatments including surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, hormonal therapies, molecularly targeted agents, and multimodality treatments.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics (n = 67)

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Continuum of care | ||

|

| ||

| Active treatment early stage | 23 | 21 |

| Active treatment advanced stage | 39 | 36 |

| Active treatment unknown stage | 15 | 14 |

| Post treatment within 5 years diagnosis | 21 | 19 |

| Post treatment 5+ years diagnosis | 11 | 10 |

|

| ||

| Cancer site | ||

|

| ||

| Breast | 29 | 27 |

| Prostate | 24 | 22 |

| Lung | 11 | 10 |

| Colon or rectal | 7 | 6 |

| Hematologic | 8 | 7 |

| Gynecologic | 16 | 15 |

| Othera | 14 | 13 |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

|

| ||

| White | 79 | 72 |

| Black or African American | 29 | 27 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1 | 1 |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity | ||

|

| ||

| Non-Hispanic | 107 | 98 |

| Hispanic | 1 | 1 |

| Missing | 1 | 1 |

|

| ||

| Sex | ||

|

| ||

| Male | 44 | 40 |

| Female | 65 | 60 |

|

| ||

| Age | ||

|

| ||

| <40 | 12 | 11 |

| 41-50 | 23 | 21 |

| 51-64 | 48 | 44 |

| 65-79 | 23 | 21 |

| 80+ | 3 | 3 |

Other cancer sites included bladder, head and neck, mesothelioma, renal cell, thymoma, and thyroid.

Importance of the topic

Multiple factors affected how important sexual functioning and intimacy were to people. For both men and women in active treatment, sexual activity was described as less important than issues of mortality, but it was still a significant aspect of quality of life for many. As one woman described, “For me, I think part of going through the diagnosis and the treatment is you want to reaffirm everything that you can do. You’re acutely aware of what you can’t do or the compromises to your other functions because of the chemo. So, for me, it [sexual activity] was like an affirmation that I was still normal in other regards.” Feeling sexually attractive was considered more important than frequency of sexual activity for women. Men viewed decreased sexual frequency more negatively and discussed it more often than women did; descriptions of loss of sexual functioning among men ranged from “frustrating” to “disappointing” to “devastating.” However, not all men thought sexual functioning was essential to quality of life and reported positive effects of dysfunction on relationships and intimacy (described in greater detail below). A few men placed the greatest importance in sexual activity on pleasing their partners. For women with partners who wanted to be physically intimate, sexual function was considered important; however, when both partners had medical conditions that made sexual activity difficult, its importance diminished.

Table 3 shows the themes discussed by the participants overall, and by diagnosis- and sex-specific group.

Table 3.

Themes Discussed During Focus Groups, Overall and By Group (n = 109)

| Theme | Totala | During or Before Active Treatment for Cancer (11 Groups)b | Completed Treatment (5 Groups) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOMEN | MEN | WOMEN | MEN | ||||||||||||||

| Breast (n=4) |

Breast (n=7) |

GYN (n=6) |

Lung (n=7) |

CR (n=4) |

Other (n=10) |

Prostate (n=5) |

Prostate (n=7) |

Lung (n=4) |

CR (n=3) |

Other (n=10) |

Breast (n=9) |

Breast (n=9) |

GYN (n=10) |

Prostate (n=9) |

Other (n=5) |

||

| Interference from Cancer | 16 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Fatigue/lack of energy | 11 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||

| Loss of strength/endurance | 7 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||

| Shortness of breath | 1 | • | |||||||||||||||

| Pain/body tenderness | 3 | • | • | • | |||||||||||||

| Loss of feeling/sensitivity | 2 | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Organ loss/scarring | 8 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||

| GI problems | 1 | • | |||||||||||||||

| Hair loss (treatment-related) | 10 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||

| Weight gain | 9 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||

| Weight loss | 3 | • | • | • | |||||||||||||

| Early menopause | 5 | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||

| Incontinence | 2 | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Devices | |||||||||||||||||

| Ostomy | 2 | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Port | 1 | • | |||||||||||||||

| Other (e.g., wound vac,) | 2 | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Sexual Response | 16 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Desire | 16 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Erectile Function | 7 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||

| Vaginal Function | 7 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||

| Dryness/swelling | 7 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||

| Bleeding/tearing | 3 | • | • | • | |||||||||||||

| Burning/pain | 5 | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||||||

| Sores | 1 | • | |||||||||||||||

| Tightening/shrinking | 2 | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Anal Discomfort | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Orgasm | 16 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Dry ejaculation | 2 | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Burning during ejaculation | 1 | • | |||||||||||||||

| Use of Therapeutic Aids | 12 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||

| Personal lubricants | 4 | • | • | • | • | ||||||||||||

| Vaginal dilator | 3 | • | • | • | |||||||||||||

| Hormonal therapies | 2 | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Oral treatments for ED | 3 | • | • | • | |||||||||||||

| Penile injections | 2 | • | • | ||||||||||||||

| Penis pump | 3 | • | • | • | |||||||||||||

| Penile implant | 1 | • | |||||||||||||||

| Body Image | 16 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Perceived Sexual Attractiveness | 16 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Comfort with self | 11 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||

| Comfort with others | 12 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||

| Masculinity/femininity | 12 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||

| Satisfaction | 14 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Sexual Activities (Types and Freqs) | 15 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Fertility | 8 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||||||||

| Communication About Sex | 15 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |

| With Partners | 13 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| With Health Care Providers | 9 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||||||

Number of groups out of 16 that discussed the theme.

Interference from cancer

There was considerable discussion in all groups regarding how specific symptoms from cancer or side effects from its treatments affect sexual functioning and intimacy. The most common symptoms reported were fatigue or lack of energy (11/16 groups), treatment-related hair loss (10/16 groups), weight gain (9/16 groups), and organ loss or scarring (8/16 groups). Such symptoms affected both physical (sexual response, 16/16 groups) and psychological (body image, 16/16 groups) aspects of sexual functioning and intimacy. For example, radiation and surgical treatments on or near the genitals (mainly for prostate, colorectal, and gynecological cancers) often severely compromised sexual functioning. Radiation treatments also caused sexual problems for people with other cancers, such as for the participant in active treatment for breast cancer who stated, “The radiation burned so badly and my chest wall was damaged so it was like the left side of my body could have sex but the right side was off limits.” The main physical complaint attributed to chemotherapy was fatigue, which was most often blamed for decreased desire for sexual activity as well as decreased stamina. One participant undergoing chemotherapy said, “My brain was kind of going there, but then my body was just sort of slacking.” Some participants in post-treatment follow-up said sexual desire eventually returned, but this was not true for everyone, even years after treatments were over.

Sexual response

Disease- and treatment-related problems with genital function were common. For women, vaginal dryness was the chief complaint, again, primarily related to the treatments received (hormone, radiation, and chemotherapy were all mentioned). For most, using personal lubricants solved the problem, but a minority of women experienced such painful sex and/or tearing or bleeding from dryness that they avoided intercourse entirely. Participants with gynecological cancers said hormonal therapies (e.g., estrogen replacement, progesterone cream) helped with dryness, but two women in this group said dryness was so bad they experienced bleeding just from daily activities such as walking, let alone sex. Some women from post-treatment follow-up groups said eventually their natural lubrication came back.

For men, erectile dysfunction was the biggest concern, leading multiple participants to describe sexual activity after cancer as “work,” that is, it required extra efforts to get or maintain an erection. Men described numerous therapeutic treatments for erectile dysfunction and their varying successes with them, (e.g. “with drugs, it’s pretty successful now” and “the pump kills desire for me”).

For participants who could achieve orgasm, most thought it was unchanged. However a minority thought it became easier to achieve or became more intense because of uncertainty about mortality, e.g., “there’s a desperation now.” Both dry and retrograde ejaculation were major changes in orgasm for male participants who had had prostatectomy.

Body image

Participants expressed that organ loss or scarring, treatment-related hair loss, and weight gain were symptoms that adversely affected body image. These were the most commonly cited factors related to reduced feelings of sexual attractiveness and threats to masculinity or femininity. Women across cancer types and treatment trajectories described how feeling undesirable affected their motivation for sex. Women said they stopped spending time on their looks because of their cancer, e.g., “Sometimes I feel that I’m just not worth fixing up,” while others said they wore more make-up or jewelry to compensate for lack of hair and other physical changes. Women described avoiding sex, for example, one said, “I’ve got this cancer in me. Why would you want to sleep with me?” Men also frequently discussed how weight gain made them feel less sexually attractive. For those who lost erectile function (primarily prostate and colorectal cancers), embarrassment at not being able to perform could be isolating, limiting them in relationships with both women (e.g., “it affects my confidence in the relationship,”) and men (“I’ve gotten together just with a group of men at the weekend away playing golf or whatever, and.... I sit there and I listen, because I can’t contribute [to the conversations about sexual activity]. I [feel] very much inferior, withdrawn from the group.”) One man with a colostomy bag had significant issues with negative body image, “Now, I could stand naked, and women could come in here and look at me, and they’d run out the door. You have that body image.”

Relationships Among Sexual Function, Satisfaction, and Intimacy

While the majority of participants reported that cancer and its treatments affected sexual functioning, there was significant variation in how this affected their satisfaction with their sexuality and intimacy. Participants’ conceptualizations of emotional intimacy within the confines of sexual dysfunction tended to fall into one of four categories:

1) Intimacy declined without sexual activity

For some, loss of function and/or inability to have intercourse was purely negative. Multiple women described feeling guilty about not having sex and letting this interfere with their intimate relationships in other ways. A woman in active treatment for a gynecological cancer said she distanced herself from her husband emotionally because she “felt like a failure” for being unable to have intercourse. Likewise, many male participants talked about pushing partners away and their desire to be alone after they lost sexual function.

2) Intimacy became an alternative to sexual activity

Another subset of participants accepted intimacy as a substitute for sexual activity. For example, a man with lung cancer said, “We can enjoy each other without having sex, and a lot of times, it’s the closeness, the intimacy, more so than it is the actual act of intercourse,” and a woman with breast cancer said, “[Sex] was intended but both of us were so tired that we would lie in bed and hold hands and say, “Oh, is that good for you?”

3) Intimacy was sexual activity

A minority of patients seemed to have broadened their conceptualization of sexuality to include intimacy in the absence of any genital activity. For example, one participant with prostate cancer said, “We never felt that [surgical castration] really hurt our sex life. We didn’t have intercourse, but we hugged and you go down the street and you hold hands.... I think before, you have sex and then you go on about your business and so on. But this way, you’re having sex all the time.”

4) Increased intimacy led to an improvement to sexual activity

Perhaps the most satisfied patients were those who let physical changes provide an impetus to improve their sexual relationships. For example, a male participant with breast cancer described, “My wife and I do more now than ever… we walk, we talk, we go out.... Before, we’d go out to dinner, and I’m trying to get home and get in the sack. Now [with impotence], I’m not in a hurry to get home and get in the sack,” and a woman with lung cancer said, “Actually, it is better than ever. We hug a lot, yes, we kiss a lot. Before, we were so hurried; now we take the time.”

Fertility

Fertility was discussed in half of the groups overall, more often in groups of women (6/9 groups) than men (2/7 groups). Not surprisingly, it was more of a concern in groups with younger (< age 50) participants. Some participants described designing their treatment course around fertility concerns. The general consensus of participants was that fertility was a separate issue from sexuality.

Communication about sex

Participants indicated that communication with partners and health care providers was very important. Communication with partners was discussed in 13 of the 16 groups, and included sub-themes such as expressing fears of touching, expressing fears of hurting, expressions of desire or compliments, expressions of criticism about appearance, and mutual understanding of sexual changes. Communication with health care providers was discussed in 9 of the 16 groups and included sub-themes such as receiving (or not) information about sexual side effects and available therapeutic aids, asking providers about sexual problems, and including spouses in conversations about sexual issues. These qualitative data are being combined with quantitative data in a separate manuscript specifically about communication.

Diagnosis-specific problems

Some symptom-related effects on intimacy were unique to particular diagnoses, such as shortness of breath in lung cancer, gastrointestinal problems in colorectal cancers, and incontinence in prostate cancer. Sexual problems related to medical devices were not common across cancer types, but caused significant problems in colorectal cancers especially. One woman in active treatment for colorectal cancer said her husband was afraid of disrupting her ileostomy bag or Vacuum Assisted Closure system (wound VAC) and thus touches her infrequently even while having sex. Another woman in this group described how wearing an oxygen nasal cannula (mask) prevented her from kissing her husband. A woman in active treatment for gynecological cancer said her port gets in the way of sex, because it is sore, she is very protective of it, and is afraid sex will hurt it. Finally, a woman in active treatment for brain (pineal) cancer said having a shunt from the back of her head to her abdomen makes positioning (lying on her back) for sex especially difficult.

Discussion

This study is one of the most comprehensive qualitative studies to date on the unique ways sexual functioning and intimacy are disturbed by cancer and its treatments. No previous studies of focus groups investigating sexual function and intimacy after a cancer diagnosis have looked across a wide range of cancer diagnoses. Participants described a number of specific ways cancer and its treatments affect sexual response, sexual activities, and body image, as well as their use of therapeutic aids to help treat sexual problems. The related themes of fertility and communication with partners and health care providers were also discussed. From these discussions, it seems that sexual problems are both prevalent and persistent among individuals diagnosed with cancer and their partners, regardless of particular diagnosis or treatment trajectory (for the most part). However, we also heard about diagnosis-specific problems that adequate measures of sexual function for people with cancer should address.

The primary purpose for collecting these data was to inform the development of an improved measure of sexual function for cancer patients. The results from the PROMIS sexual function focus groups helped the domain group to identify the most salient issues to patients. Previous measures of sexual function used for cancer populations have commonly included sub-domains of sexual response such as sexual desire, sexual arousal, orgasm, sexual satisfaction, frequency of sexual activity, and problems affecting sexual function such as anorgasmia, pain, and vaginal tightness [15]. Less common domains from previous measures have included sexual fantasies, sexual self-esteem or self-image, sexual attitudes and beliefs, sexual role, and partner function or perceptions [15]. Results from the PROMIS sexual function focus groups suggest that for cancer populations, important additions would include nongenital interferences from cancer and use of therapeutic aids. It is also clear that overall evaluations of satisfaction with sex life may not necessarily correspond to specific aspects of functioning, and scoring of sexual function measures should account for this.

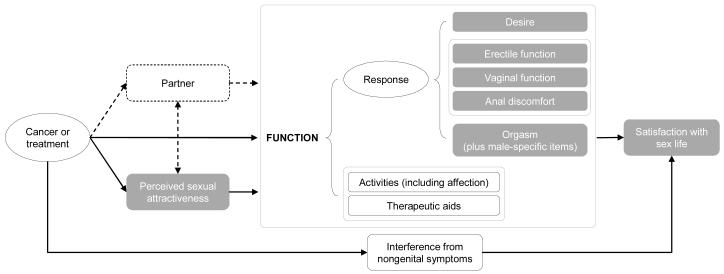

In what follows, we discuss our conceptual measurement model (Figure 1) and its rationale based on the focus group data. The model summarizes the measurement concepts in roughly causal terms: cancer or cancer treatments are thought to affect perceived sexual attractiveness, sexual function, and cause interference from nongenital symptoms; function and interference from nongenital symptoms in turn affect satisfaction with sex life.

Figure 1.

Conceptual measurement model

Perceived sexual attractiveness refers to that aspect of body image relevant to a person’s sexuality. Data from our study and others indicate that cancer or its treatment can significantly impact a person’s perceived sexual attractiveness.

Sexual function is described in terms of sexual response and two other categories necessary to contextualize the understanding of the person’s sexual response: activities and therapeutic aids. Sexual response includes desire, erectile function, vaginal function, and orgasm. Data from our focus groups and expert review highlighting the need to accommodate a broader range of sexual activities led us to add the concept of anal discomfort to response. Levels of functioning occur in the context of different activities. From our focus groups, it was clear that many patients viewed affectionate behavior (holding hands, hugging, kissing) on the same continuum as activities that involved sex organs. We include all such behaviors under activities. Levels of functioning also occur in the context of different therapeutic aids people use to improve their functioning. Participants in our study reported a variety of such aids. It seems important to capture this information in order to understand how certain levels of functioning are achieved by some people and to be able to document longitudinal changes in the use of such aids.

An important category that was added as a direct result of our focus group study was interference from nongenital symptoms. Patients in our focus groups described a variety of symptoms that resulted from their disease or its treatment that restricted their engagement in and enjoyment of sexual activities (e.g., fatigue, treatment-related hair loss, anxiety, etc). While not sexual outcomes per se, such symptoms would be useful to measure so that researchers could test mediational hypotheses concerning sexual outcomes.

One of the interesting findings from the focus groups was the complexity of relationships among functioning, intimacy, and overall satisfaction with the person’s sex life. Overall evaluations of satisfaction with sex life did not necessarily correspond to specific aspects of functioning, as many participants described satisfaction with sex life and intimacy despite decreased sexual function. Thus, it is critical to measure satisfaction with sex life as a separate concept from functioning.

One important domain for people who engage in partnered sex and/or are in committed relationships is the role of the partner. Our focus group study concentrated on the patient’s functioning and experience, but many issues arose spontaneously about communication with partners, attitudes of partners, and other related concepts. Due to the complexity and importance of partner issues, the PROMIS sexual domain group decided that these would be addressed at a later time in an effort befitting the significance and subtlety of partner-related issues.

Uses/Limitations of Focus Groups

Very few previous studies have used focus groups to investigate sexual function following cancer treatment; we found two focus group studies with prostate cancer patients [19,20] and one study of female cancer survivors [21]. The main advantage of focus groups for measure development is the ability to capture experiences and opinions from many people in a short amount of time (compared to individual interviews). Focus groups can also have a facilitating effect; that is, patients who have experienced problems or worries may be relieved to hear that others had the same issues and become more eager to discuss them, something that may not happen in an individual interview with an interviewer who has not had cancer. It is possible that the presence of others might also inhibit some people from discussing their sexuality. During our focus groups, participants generally seemed engaged in the discussions. We saw little evidence of discomfort or difficulty articulating among female participants. In comparison, some male participants (n≈6) needed prompting from the moderator to share their experiences, and some (n≈2) seemed reluctant to discuss specific details about their experiences even when prompted to do so directly. When discussing sensitive issues such as sexuality, no single method is likely to elicit frank discussion from all types of people. Future research could explore whether different data would be gleaned from individual interviews or open-ended self-report surveys.

The next steps in development of the PROMIS sexual function measure include revision of the measurement model based on focus group data and other information; writing items to address the concerns raised in the focus groups; cognitive interviews [22]; large-scale item testing and psychometric evaluation of candidate survey items; responsiveness testing; extending validation to non-cancer populations; and translation into Spanish and other world languages.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Cancer Institute supplement to grant U01AR052186 from the National Institutes of Health.

The authors thank Elizabeth A. Hahn of Northwestern University for participation in the PROMIS Sexual Function Domain Committee.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: None reported.

References

- 1.Wright JL, Lin DW, Cowan JE, Carroll PR, Litwin MS. Quality of life in young men after radical prostatectomy. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2008;11:67–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheppard LA, Ely S. Breast cancer and sexuality. Breast J. 2008;14:176–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2007.00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemieux L, Kaiser S, Pereira J, Meadows LM. Sexuality in palliative care: patient perspectives. Palliat Med. 2004;18:630–637. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm941oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilmoth MC. The aftermath of breast cancer: an altered sexual self. Cancer Nurs. 2001;24:278–286. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bukovic D, Silovski H, Silovski T, Hojsak I, Sakic K, Hrgovic Z. Sexual functioning and body image of patients treated for ovarian cancer. Sex Disabil. 2008:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Cancer Institute . Sexuality and Reproductive Issues (Physician Data Query): Health Professional Version. NCI; InBethesda, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruner DW, Calvano T. The sexual impact of cancer and cancer treatments in men. Nurs Clin North Am. 2007;42:555–580. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hordern AJ, Street AF. Communicating about patient sexuality and intimacy after cancer: mismatched expectations and unmet needs. Med J Aust. 2007;186:224–227. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shell JA, Carolan M, Zhang Y, Meneses KD. The longitudinal effects of cancer treatment on sexuality in individuals with lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:73–79. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.73-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babin E, Sigston E, Hitier M, Dehesdin D, Marie JP, Choussy O. Quality of life in head and neck cancers patients: Predictive factors, functional and psychosocial outcome. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;265:265–270. doi: 10.1007/s00405-007-0561-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herzog TJ, Wright JD. The impact of cervical cancer on quality of life: the components and means for management. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107:572–577. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ananth H, Jones L, King M, Tookman A. The impact of cancer on sexual function: a controlled study. Palliat Med. 2003;17:202–205. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm759oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKee AL, Jr., Schover LR. Sexuality rehabilitation. Cancer. 2001;92:1008–1012. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010815)92:4+<1008::aid-cncr1413>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright EP, Kiely MA, Lynch P, Cull A, Selby PJ. Social problems in oncology. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:1099–1104. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeffery DD, Tzeng JP, Keefe FJ, Porter LS, Hahn EA, Flynn KE, Reeve BB, Weinfurt KP. Initial report of the cancer Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) sexual function committee: review of sexual function measures and domains used in oncology. Cancer. 2009;115:1142–1153. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, Gershon R, Cook K, Reeve B, Ader D, Fries JF, Bruce B, Rose M. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45:S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Cook KF, Crane PK, Teresi JA, Thissen D, Revicki DA, Weiss DJ, Hambleton RK, Liu H, Gershon R, Reise SP, Lai JS, Cella D. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Med Care. 2007;45:S22–31. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeWalt DA, Rothrock N, Yount S, Stone AA. Evaluation of item candidates: the PROMIS qualitative item review. Med Care. 2007;45:S12–21. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254567.79743.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bokhour BG, Clark JA, Inui TS, Silliman RA, Talcott JA. Sexuality after treatment for early prostate cancer: exploring the meanings of “erectile dysfunction”. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:649–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark JA, Wray N, Brody B, Ashton C, Giesler B, Watkins H. Dimensions of quality of life expressed by men treated for metastatic prostate cancer. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:1299–1309. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bruner DW, Boyd CP. Assessing women’s sexuality after cancer therapy: checking assumptions with the focus group technique. Cancer Nurs. 1999;22:438–447. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199912000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fortune-Greeley AK, Flynn KE, Jeffery DD, Williams MS, Keefe FJ, Reeve BB, Willis GB, Weinfurt KP. Using cognitive interviews to evaluate items for measuring sexual functioning across cancer populations: improvements and remaining challenges. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:1085–1093. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9523-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]