Abstract

This paper discusses mathematical models of expressing severity of injury and probability of survival following trauma and their use in establishing clinical governance of a trauma system. There are five sections: (i) Historical overview of scoring systems—anatomical, physiological and combined systems and the advantages and disadvantages of each. (ii) Definitions used in official statistics—definitions of ‘killed in action’ and other categories and the importance of casualty reporting rates and comparison across conflicts and nationalities. (iii) Current scoring systems and clinical governance—clinical governance of the trauma system in the Defence Medical Services (DMS) by using trauma scoring models to analyse injury and clinical patterns. (iv) Unexpected outcomes—unexpected outcomes focus clinical governance tools. Unexpected survivors signify good practice to be promulgated. Unexpected deaths pick up areas of weakness to be addressed. Seventy-five clinically validated unexpected survivors were identified over 2 years during contemporary combat operations. (v) Future developments—can the trauma scoring methods be improved? Trauma scoring systems use linear approaches and have significant weaknesses. Trauma and its treatment is a complex system. Nonlinear methods need to be investigated to determine whether these will produce a better approach to the analysis of the survival from major trauma.

Keywords: trauma scoring, clinical governance, TRISS, a severity characterization of trauma, complex system, trauma

1. Introduction

Clinical governance (CG) is a core function of the Defence Medical Services (DMS) [1–5]. In relation to the UK's overseas operational commitments, CG provides the measures of performance for our deployed clinical services. It is the system by which the assessment, treatment and evacuation of Service personnel is continuously monitored. It is a quality assurance process with one aim: to maintain and improve clinical practice.

Trauma scoring has played a central part in the development of quality assurance for the seriously injured. The models and processes described in this paper not only have provided the proof of improving performance over time, but are part of a sophisticated and deep-rooted organizational governance culture that can identify weaknesses in trauma system performance, while having the flexibility to resolve weaknesses rapidly through changes in guidelines, training or equipment. This has evolved out of necessity through the imperative of a sustained high casualty load on contemporary operations. It is now clear that the early management of severe trauma in DMS has diverged and advanced beyond that available in the NHS [4,5]—and this is despite the complexity and volume of trauma being far higher in the military context.

In 2008, a report from the Healthcare Commission described the military trauma system as ‘exemplary’ [6]; in contrast, reports over the last 20 years sponsored by the Royal College of Surgeons of England [7,8] and the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Deaths (NCEPOD) [9] have been critical of trauma care in the NHS.

In this article, we focus on how trauma scoring is used to inform the CG process and assist the development of a trauma service. The article is divided into five sections:

— the rationale for and methods of trauma scoring;

— UK casualty statistics: definitions and rates;

— trauma clinical governance;

— unexpected outcomes; and

— future developments: can trauma scoring models improve?

2. The rationale for trauma scoring

To improve overall trauma care, clinicians must be able to show that the introduction of new concepts, clinical practices and organizational processes are beneficial to patient outcome. This requires reliable and reproducible metrics by which to measure trauma system performance: these must be internally consistent and facilitate direct comparison with external, parallel trauma systems. Trauma scoring models are the tools that support this internal performance analysis and external systems comparison.

(a). Trauma scoring systems

The overall utility and validity of trauma scoring is dependent on clinical personnel undertaking comprehensive and accurate data collection, in real time and near-real time. Models are based on anatomical or physiological descriptors, or combine both. Those models that exclusively use anatomical descriptors of injury have an advantage: the extent and severity of tissue damage is quantifiable by clinical examination and by radiological, operative and post-mortem findings. In addition, physical findings are usually constant after the initial injury, compared with physiological parameters that will change in response to treatment during the patient's journey. Despite this, physiological scoring systems give a reproducible assessment of the overall condition of the patient as they do not rely on the interpretation of the observer. Combined systems that use both physiological and anatomical descriptors are the most reliable, but are more complicated to apply. The search for the ‘perfect’ injury severity scoring system is incomplete within 40 years of systems development.

(b). Anatomical models

Anatomical trauma scoring models are based on either the abbreviated injury scale (AIS) or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD).

(i). Abbreviated injury scale

Since its introduction in 1971 by the Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine, the AIS [10] has provided a standardized system of injury description, which is the basis for several injury scoring systems and research into the design of safer vehicles. The AIS is derived by an expert consensus group to provide a single system for classifying the type and severity of injuries sustained during a motor vehicle collision (MVC). The maximum AIS—the highest single AIS of a patient with multiple injuries—has been used as a predictor of outcome and is a good discriminator for survival [11].

The AIS assigns a six-figure description code together with a severity score to individual injuries (penetrating and blunt). The code facilitates electronic entry and retrieval of data. The severity score ranges from 1 to 6 (table 1) and is nonlinear.

Table 1.

AIS injury ranking by severity and ISS body regions.

| AIS numerical descriptor | AIS severity descriptor | ISS body regions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | minor | head and neck |

| 2 | moderate | face |

| 3 | serious | chest |

| 4 | severe | abdomen |

| 5 | critical | extremities |

| 6 | maximum | external |

The AIS has undergone six revisions or updates since its introduction in 1971, to enhance and improve the system. Initially, only 73 injuries were described; in the 2005 edition [10], this has increased to over 2000 injuries and there is an independent military directory—the latter specifically takes account of the differing circumstances under which military injuries occur.

Trained and experienced staff are required to code data and to perform scoring; minimizing inter-observer variation is important and a quality control system is needed. Involving medical personnel in scoring improves accuracy [12].

(ii). Injury severity score

In 1974, Baker et al. [13,14] used the AIS to develop the injury severity score (ISS). All injuries are coded using the AIS injury descriptors and divided into six body regions (table 1). The highest severity score from each of the three most seriously injured regions is taken and squared. The sum of the three squares is the ISS, which has a range of 1–75. A score of 75 is incompatible with life, and therefore any patient with an AIS 6 injury in any one region is awarded a total score of 75. An ISS greater than 15 signifies major trauma, as a score of 16 is associated with a mortality rate of 10 per cent.

Since the ISS is based on the AIS, it is also a nonlinear measure. In addition, certain scores are common and others impossible. The non-linearity is a disadvantage as a patient with an isolated AIS 5 injury is more likely to die than a patient with both an AIS 4 injury and an AIS 3 injury [15]. However, both patients will have an ISS of 25.

(iii). New injury severity score

One of the main criticisms of ISS is that it fails to take into account multiple serious injuries in one body region [16], which may for example be significant in an isolated head injury (with a combination of subdural, subarachnoid and extradural haemorrhage) or a patient with multiple limb amputations (commonly seen in contemporary combat trauma). A second serious injury in the same body region would be ignored when calculating ISS, in favour of a less serious injury in a different body region, potentially underestimating mortality.

This led to the development of the new injury severity score (NISS) in 1997 [17]. NISS is calculated from the sum of the squares of the three highest AIS injury codes, irrespective of their body region. This ability to account for multiple serious injuries in one region reduces the underestimation of mortality seen in ISS [18–20], although Moore et al. suggest that NISS can lead to an overestimation of mortality [21], as it implies that a second serious injury in the same body region has a greater impact on outcome than a less severe injury in a different body region.

(iv). Organ injury scaling

Scaling systems for injuries to individual organs have been developed by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. The scales, like the AIS, run from 1 to 6, with 6 being a mortal injury. The mangled extremity severity score is used to identify patients for primary amputation with irretrievably injured limbs [22].

(v). Anatomic profile

This scoring system takes injuries with AIS scores of greater than 2 and groups them into three components: A, head, brain and spinal cord; B, thorax and the front of the neck; C, all remaining injuries [23]. The anatomic profile (AP) is the anatomical component of a severity characterization of trauma (ASCOT) (§2b). Although the AP discriminates survivors from non-survivors better and is more sensitive [19], ISS remains the most widely used system.

(vi). International classification of disease injury severity score

International classification of disease injury severity score (ICISS) has been developed since the early 1990s to avoid dependence on AIS codes and simplify data collection and coding [24–28]. Operative procedures are also coded. Although initially based on the International Classification of Disease 9th edition (ICD-9), ICISS has also been validated for ICD-10 codes [29]. The calculation of survival risk ratios (SRRs) is central to this method (the proportion of survivors for each ICD-9 injury code). ICISS is the product of the SRRs for each of the patient's 10 worst injuries.

ICISS is an empirical measure rather than consensus-derived and claims improvements in predictive accuracy over ISS and trauma score-injury severity score (TRISS), especially when combined with factors allowing for physiological state and age, but is data dependent and functions less effectively with missing datasets. Batchelor et al. [30] also report that some of the SRRs calculated for less commonly used ICD codes have been based on sample sizes of 30 cases or less. Additionally, as each SRR is calculated independently, the ICISS does not account for the cumulative effect of multiple injuries in survival prediction. These issues mean that ICISS has yet to be adopted on a widespread basis.

(vii). Wesson's criteria

This is a crude calculation for assessing the effectiveness of a trauma system [31]. Major trauma cases (ISS >15) are identified, but those with an ISS >60 or a head injury with AIS 5 are excluded as ‘unsalvageable’. The remainder are considered ‘salvageable’ and the performance of the trauma system is expressed as the percentage of these patients surviving. It is an easier calculation than the TRISS methodology, but does not take into account those unsalvageable casualties who survive (unexpected survivors).

(c). Physiological systems

(i). Revised trauma score

This is based on three parameters: respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure and Glasgow coma scale (GCS) [32]. Each parameter scores 0–4 points, and this figure is then multiplied by a weighting factor. The resulting values are added to give a score of 0 to 7.8408. The weighting factor allows the revised trauma score (RTS) to take account of severe head injuries without systemic injury, and be a more reliable indicator of outcome. The first recorded value for each parameter after arrival at hospital is used to ensure consistency in recording, although it has been shown that field values for GCS are predictive of arrival values and make little difference to the accuracy of the RTS [33].

(ii). Triage revised trauma score

This modification of the RTS allows rapid real-time physiological triage of multiple patients. It uses the sum of the raw RTS values (0–12) to allocate priorities. This system is currently used as a triage system by many ambulance services and is also recommended for triage in major incidents [34]. It has been suggested that the triage revised trauma score (TRTS) is as good a discriminator of outcome as the RTS [35].

(iii). Paediatric trauma score

The RTS has been shown to underestimate injury severity in children [36,37]. The paediatric trauma score (PTS) combines observations with simple interventions and a rough estimation of tissue damage. The PTS tends to overestimate injury severity, but is used as a paediatric pre-hospital triage tool in the USA.

(d). Combined systems

(i). Trauma score-injury severity score

This uses the RTS and ISS as well as the age of the patient [38]. Weighting coefficients are used for blunt and penetrating trauma, and a Naperian logarithm is applied. Different study groups may use their own coefficients to take account of the characteristics of the trauma seen in their populations. By convention, patients with a probability of survival (Ps) of less than 50 per cent who survive are ‘unexpected survivors’ and those with a Ps greater than 50 per cent that die are ‘unexpected deaths’. TRISS is not valid for children under the age of 12 years.

TRISS incorporates ISS and its limitations and, therefore, will overestimate Ps for patients with multiple injuries in the same isolated body region.

It must be stressed that the Ps is a mathematical expression of the probability of survival, and not an absolute statement of the patient's likely outcome. One in four patients with Ps 75 per cent will still be expected to die. While these cases may be highlighted for audit to identify lessons to be learned, conclusions about system performance should not be drawn from single patients. TRISS can usefully compare performance between trauma systems or against a national standard, where the limitations of the model apply consistently.

(ii). A severity characterization of trauma

This is a more recent system, first described in 1990 [39]. ASCOT has proved more reliable than TRISS in predicting outcome in both blunt and penetrating trauma—as by using AP it takes account of more than one injury in a single body region [40]. ASCOT also uses the individual components of the RTS and a more detailed age classification, but this makes it a more complicated calculation (also using a Naperian logarithm). ASCOT has not replaced TRISS because the improvement in performance is small and the increased difficulty in calculation outweighs it.

(e). Multicentre studies

The major trauma outcome study (MTOS) started in the United States during the early 1980s [41], and is now established internationally. MTOS expanded into the UK in 1988 following the report of the Royal College of Surgeons criticizing trauma care. Now called the Trauma Audit Research Network (TARN), it is based at the Northwest Injury Research Centre. Around 90 NHS hospitals contribute trauma data to TARN. In Scotland, all hospitals participate in the Scottish Trauma Audit Group.

The initial aim of MTOS was to develop and test coefficients and Ps values to increase the predictive accuracy of scoring systems, and to give feedback to contributing trauma units. The data collected have become more detailed. Pre-existing morbidity, mechanism of injury, operations, complications and the seniority of attending staff are all included as the patient is followed from the scene of injury through the Emergency Department and hospital to discharge. The feedback allows audit and comparison of performance over time and between units.

3. UK casualty statistics: definitions and rates

(a). Introduction

As well as collecting casualty statistics, the presentation of meaningful, accurate information on casualties sustained during military operations is important and likely to be closely scrutinized by the public, media, politicians and military allies.

This section presents measures that have been used to put casualty figures in context historically and internationally, and notes differences in data collection that affect the validity of these comparisons. UK military casualties sustained during conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan 2007–2008 are used as an illustration.

The Ministry of Defence (MOD) publishes fortnightly casualty and fatality tables [42,43], including counts of wounded in action (WIA), killed in action (KIA) and died of wounds (DOW). In a similar way, the US Department of Defense publishes numbers of operational casualties and fatalities that are updated regularly [44].

Without the relevant denominators, these numbers are hard to interpret on their own. In the previous literature on military conflicts, the casualty rates [45], WIA and KIA rates [46,47] have been presented as per 1000 troops at risk per day. More recently, fatality rates have been presented per 1000 personnel-years [48].

However, if the purpose is to describe the effectiveness of medical care in-theatre and after evacuation of casualties, then different denominators are used to calculate percentages [49,50]. There is scope for confusion since these percentages are also sometimes referred to erroneously as rates. A consistent approach to calculating percentages of KIA, DOW and case fatality was presented by Holcomb et al. [51]. This approach allows the statistics to be used to make comparisons between conflicts from the Crimean War to contemporary operations in Iraq and Afghanistan [51,52].

(b). UK definitions of casualties

KIA, DOW and WIA refer to different categories of death or injury as the direct result of hostile action. Injuries sustained on operation, but not directly resulting from hostile action, are similarly defined as killed non-enemy action (KNEA), died non-enemy action and wounded non-enemy action. The definitions are:

— KIA: personnel killed instantly or before reaching a UK or a coalition ally medical treatment facility.

— DOW: personnel who die as a result of their injuries after reaching a UK or coalition ally medical treatment facility (MTF).

— WIA: all wounded personnel who attend a UK Field Hospital emergency department (role 2E/role 3) for treatment of their injuries. The definition includes personnel admitted who survived to the date the information was extracted.

KIA includes personnel who arrive at the MTF with cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in progress and who do not have any return of spontaneous circulation at the MTF.

A further category returned to duty (RTD) is defined as the number of personnel who return to duty within 72 h of their attendance for treatment of their injuries. This is required for the consistent calculation of casualty statistics and is taken as those attending a UK Field Hospital emergency department, but not requiring admission. Note that RTD information on UK WIA survivors attending US or other coalition ally medical facilities is not available.

(c). UK compilation of casualty data

Defence Analytical Services and Advice (DASA) provides professional analytical, economic and statistical services and advice to the MOD, and defence-related statistics to parliament, other government departments and the public. DASA is responsible for centrally collating and validating casualty and deaths data and ensuring that all discrepancies between administrative and medical data are resolved.

Initial casualty notification (NOTICAS) is used to identify casualties owing to hostile action. WIA figures are compiled using the Operational Emergency Department Attendance Register (OpEDAR) and primary care in-theatre returns and validated against NOTICAS. KIA and DOW status are confirmed by the Academic Department of Military Emergency Medicine following post-mortem.

There are minor differences between the definitions used here and those used to compile the information provided on the MOD website [42,43]. This is to allow alignment with the definitions used by Holcomb et al. [51]. The WIA data presented in this paper comprise hospital attendances to as well as admissions at UK field hospital facilities. In contrast to the figures used here, the WIA figures on the website are for UK Service personnel and civilians admitted to coalition medical facilities.

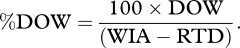

Using Holcomb's definitions, statistics on %KIA, %DOW and the case fatality rate (CFR) are calculated as follows:

This is KIA as a percentage of all killed or WIA minus those who are RTD (who are subtracted from the denominator as they are not thought to be at risk of dying).

- This is DOW as a percentage of all WIA, minus those who are RTD.

This is the number of fatalities (KIA or DOW) expressed as a percentage of all killed or WIA. In this instance, those RTD have not been excluded from the denominator. Note also that ‘rate’ in CFR is a misnomer as, like %KIA and %DOW, the calculation is a simple percentage. It is important to note that in the denominator, WIA includes DOW in its total.

(d). Differences between UK and US casualty data

There are several important differences between UK and US casualty data in terms of definitions and validation. Firstly, the US definition of hostile action is applied more widely to tie in with issues of pay and honours. Therefore, some deaths classed as KIA or DOW in the USA would be recorded as ‘killed non-enemy action’, ‘died on operations’ or ‘operational accidents’ in the UK. Secondly, US personnel are followed up for mortality outcomes up to 120 days after discharge from the Services for inclusion among the in-Service deaths. There is not yet a mechanism for follow-up of discharged personnel in the UK. Finally, US data validation is not carried out centrally and personnel administrative data are not validated against medically recorded data. In the UK, DASA is responsible for centrally collating and validating casualty and deaths data and all discrepancies between administrative and medical data are resolved.

(e). Results

%KIA, %DOW and CFR are presented for Op TELIC and Op HERRICK in tables 2 and 3 for 2007 and 2008. There is no statistical evidence of a difference in %KIA, %DOW or CFR between the two operations. Similarly, there is no evidence of a difference between 2007 and 2008. However, the change in tempo of operations for Op TELIC appears to be reflected in the %DOW figures, with no DOW deaths in 2008 and the CFR of 12.8 in 2007 was halved in 2008. Note that these statistics are based on small numbers of events and could therefore be due to random fluctuation.

Table 2.

Op TELIC casualty statistics: numbers and %KIA, %DOW and CFR with 95% CI, 2007 and 2008. These numbers exclude civilians and UK Service personnel admitted to coalition medical facilities, and therefore differ from those shown on the MOD website.

| KIA | DOW | WIA | RTD | %KI (95% CI) | %DOW (95% CI) | CFR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 26 | 10 | 256 | 51 | 11.3 (7.5–16.1) | 4.9 (2.4–8.8) | 12.8 (9.1–17.2) |

| 2008 | 2 | 0 | 34 | 20 | 12.5 (1.6–38.4) | 0 (–) | 5.6 (0.7–18.7) |

| overall | 28 | 10 | 290 | 71 | 11.3 (7.7–16.0) | 4.6 (2.2–8.2) | 12.0 (8.6–16.0) |

Table 3.

Op HERRICK casualty statistics: numbers and %KIA, %DOW and CFR with 95% CI, 2007 and 2008. These numbers exclude civilians and UK Service personnel admitted to coalition medical facilities, and therefore differ from those shown on the MOD website.

| KIA | DOW | WIA | RTD | %KIA (95% CI) | %DOW (95% CI) | CFR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 35 | 2 | 265 | 46 | 13.9 (9.8–18.6) | 0.9 (0.1–3.3) | 12.3 (8.8–16.6) |

| 2008 | 47 | 3 | 265 | 46 | 17.7 (13.3–22.8) | 1.4 (0.3–4.0) | 16.0 (12.1–20.6) |

| overall | 82 | 5 | 530 | 92 | 15.8 (12.7–19.2) | 1.1 (0.4–2.6) | 14.2 (11.6–17.2) |

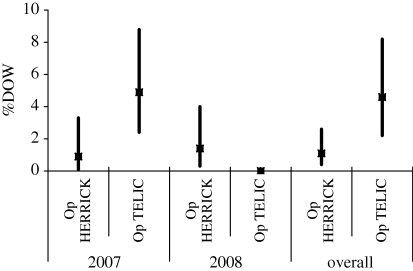

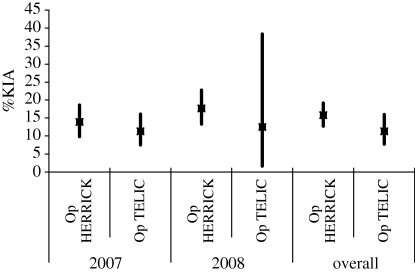

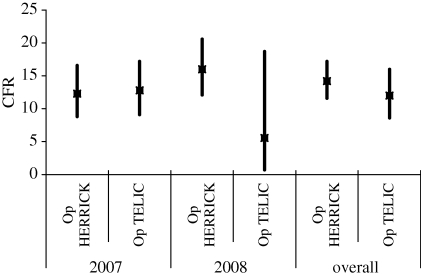

Figures 1–3 illustrate %KIA, %DOW and CFR with 95% confidence intervals (CI) shown by vertical lines. The precision of these statistics is quite consistent, with some wider confidence intervals demonstrating lack of precision where very small numbers of events are involved (e.g. two individuals KIA on Op TELIC in 2008).

Figure 2.

Per cent died of wounds by operation, 2007, 2008 and overall, with 95% CI shown by vertical lines.

Figure 1.

Per cent killed in action by operation, 2007, 2008 and overall, with 95% CI shown by vertical lines.

Figure 3.

Case fatality rate by operation, 2007, 2008 and overall, with 95% CI shown by vertical lines.

(f). Conclusions

We have presented UK military casualty statistics for contemporary operations according to the definitions of Holcomb et al. [51]. There is no evidence of a difference in %KIA, %DOW or CFR between Op TELIC and Op HERRICK or between 2007 and 2008. Some of these statistics are based on small numbers and are therefore imprecise. As more data are collected for ongoing or future operations, this will allow more precise overall estimates to be calculated, and comparisons of casualty statistics for the UK military over time and between operations. Direct statistical comparisons with published US data are unsound owing to important differences in definition, application in practice and data collection methods.

4. Trauma clinical governance

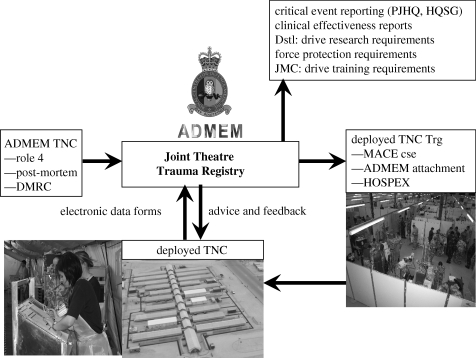

The scope of the military trauma CG system is represented in figure 4. The Joint Theatre Trauma Registry (JTTR) at the Royal Centre for Defence Medicine holds data on all casualties treated by a trauma team at one of the deployed hospitals and, since 2007, all injured patients repatriated for in-patient treatment in Birmingham.

Figure 4.

The military trauma CG process.

The critical success factor of any system that uses information, whether for monitoring or research, is the quality of the data collected. The DMS makes use of trauma nurse coordinators (TNCs), both in the ‘role 3’ field hospitals and in the ‘role 4’ tertiary receiving hospital in Birmingham. The functions of the TNC in the military environment are to facilitate quality data collection; identify governance concerns; and to manage the weekly clinical case conference. TNCs are regarded as an essential component of a major trauma centre's capability in the United States (where level 1 status will not be granted without TNC function in the hospital) [53], but have rarely been used in the NHS.

Three TNCs working at the Academic Department of Military Emergency Medicine (ADMEM) in Birmingham collect the role 4 clinical progress information from casualties on the intensive care unit or ward. This is combined with data sent from the deployed TNCs and sifted for governance concerns (clinical and force protection). The role 4 TNCs provide the pre-deployment training for their role 3 colleagues, and provide daily support to the deployed TNCs via secure telephone and e-mail.

(a). Post-mortems

Critical medical intelligence will be lost if only surviving casualties are studied [54,55]. ADMEM experience is that the effectiveness of individual techniques can be ascertained—and even when a failed or inadequate technique is not considered material to the outcome of the patient, the training message can be immediately reinforced through a responsive military system. A member of ADMEM attends all military post-mortems to identify both these clinical issues and to provide the necessary medical context when evaluating the performance of personnel and vehicle protective systems. There is close liaison with the attending scientific adviser that allows new patterns of wounding and the impact of changes in weaponry to be rapidly identified.

(b). Hospital exercise

Immediately prior to deployment, the entire field hospital undertakes a validation exercise in a replica field hospital in York. This exercise (called hospital exercise; HOSPEX) can assess an individual's performance (microsimulation techniques), a team's performance such as the trauma team or operating team (mesosimulation techniques) and the hospital's global performance in response to continued bursts of casualties (macrosimulation techniques; [56]). Anonymized casualty data from JTTR are used to construct the scenarios. The use of genuine and contemporary case scenarios, played out in real time with simulated live casualties (former soldiers who have suffered amputations) and in a realistic duplicate environment, generates the necessary face and content validity for the exercise. Importantly, this inspires confidence in those deploying for the first time and decreases the initial shock of encountering critical combat wounded in the field hospital.

(c). Joint Theatre Trauma Registry

The JTTR is derived from a composite of three independent databases:

— major trauma audit for clinical effectiveness (MACE);

— medical emergency response team (MERT); and

— operational emergency department attendance register (OpEDAR).

JTTR's principal purpose is a quality assurance system for the management of major trauma from point of wounding (POW) to rehabilitation. It is a tool to support continuous detailed clinical audit. Data from all three streams provide the full picture of all significantly injured casualties from time of injury, through pre-hospital treatment and evacuation, to the care administered at the field hospital. For UK military casualties, the continuing pathway of air evacuation to UK and definitive treatment in UK is also captured. The MERT database is an electronic record of patients treated by the UK's MERT (physician-led helicopter-borne pre-hospital team). As the MERT will deliver patients to treatment facilities other than the UK field hospital, their information will not appear in MACE unless they enter the UK system again later in their course—additionally, patients with illness rather than injury may be transported by MERT, but will not appear on MACE. OpEDAR captures all patients (injury and illness) attending the emergency department of a UK field hospital [57]: patients can be on MACE without appearing on OpEDAR if they receive their initial treatment in a non-UK field hospital, prior to evacuation to Birmingham.

An important part of the CG process is providing feedback: where outcome is unexpectedly positive (the unexpected survivor), then practice is praised and reinforced, but where practice is regarded as suboptimal, the area for improvement is highlighted, organizational change is instituted and compliance is monitored. Formal academic review of performance during a specified period of an operation is used to review and compare patterns of activity and clinical effectiveness [58–61]. JTTR has also been used to support academic evaluation of complex organizational challenges such as the effectiveness of tourniquets [62], the effectiveness of battlefield analgesia [63], the required competencies of the MERT [64] and the relationship of timelines to outcomes [65]. This in turn has shaped clinical doctrine, research priorities and changes to acute care training curricula.

(d). Joint Theatre Clinical Case Conference

The Joint Theatre Clinical Case Conference (JTCCC) accelerates and enhances this feedback process. This is a structured teleconference held weekly and coordinated by ADMEM in Birmingham, using a ‘star’ phone at each location. Participants are RCDM (military and civilian clinicians), the deployed field hospitals, the Defence Rehabilitation Centre (Headley Court), RAF Brize Norton (coordinates all aero-medical movements back to the UK), 2 Medical Brigade (the organization that trains the next deploying field hospital), Inspector General's department (oversees all DMS governance) and Permanent Joint Headquarters (the strategic headquarters for all overseas operations).

Near real-time feedback is provided on the progress of casualties admitted to Birmingham during the previous two weeks. Written case summaries are forwarded the previous day via a secure e-mail system. Any issues with the initial management are clarified, which enables immediate modification of practice where appropriate. Casualties awaiting evacuation to the UK are also presented by the deployed clinicians, giving the Birmingham medical teams advance warning and opportunity to plan the work ahead.

JTCCC has repeatedly highlighted clinical practice, equipment and training issues and is the catalyst for rapid policy change. Change is coordinated by the Head of Medical Policy in Surgeon General's department. Confidentiality is assured by referral to patients only by their admission numbers and distribution of two separate forms of minutes across the DMS: clinical addressees receive a full set of minutes; non-clinical addressees have clinical details removed. The commanding officers and deployed medical directors of medical units about to deploy receive copies of the minutes to familiarize themselves with recent developments. Institutional memory is thus developed and maintained so that each successive hospital unit and group of clinicians do not have to relearn previous lessons.

(e). Key performance indicators

Further CG assurance is maintained by exploiting key performance indicators (KPIs). The importance of establishing and monitoring KPIs was emphasized by the Royal College of Surgeons in 2000 [8]. The MACE database currently records 68 KPIs in nine domains spanning the whole patient journey (pre-hospital care; emergency department resuscitation; operative care; critical care; post-operative care; ward care; follow-up care; and burns). The KPIs were established by a multi-disciplinary panel using the best available evidence, tempered by operational experience—the recognized definition of an evidence-based approach [66].

(f). Mortality review

An important group of casualties that are commonly excluded from clinical review in other trauma systems are those that die before reaching hospital. This gap in evaluating system performance is closed within the regular mortality reviews. These are undertaken by a panel of senior clinicians from emergency medicine, anaesthetics and intensive care, general surgery and orthopaedic surgery, together with the Home Office forensic pathologist (who has undertaken the majority of the post-mortem examinations). Defence scientists and tactical experts are also present to offer advice on vehicle and personal protection, and the situation on the ground. All operational deaths are reviewed at these meetings whether the death occurred immediately on wounding, at the field hospital or following repatriation to the UK.

The mortality meeting first assesses whether a casualty was salvageable: that is, were the injuries treatable within the understanding of contemporary best practice. The patient is graded as definitely, probably or possibly salvageable or unsalvageable. A second judgement is then made as to whether the death was preventable. Weapons intelligence and other reports inform this decision: a death is classified as unpreventable if the tactics precluded access to the patient (for example, an ongoing fire-fight). Analysis of deaths in batches at periodic meetings presents a further opportunity to identify emerging patterns of severe injury and their potential causes.

(g). Benchmarking against NHS trauma care

The nature, complexity and quantity of trauma encountered on operations are of a higher level than that seen in the NHS.

The NCEPOD report in November 2007 [7] found that many NHS hospitals sampled treated less than one major trauma case per week, and some treated only one or two cases in the entire 12 week sampling period; only 12/183 (6.6%) hospitals treated more than one major trauma case per week. Experience in dealing with major trauma was directly related to performance as those with a higher caseload (more than 20 major trauma cases in 12 weeks) were judged to deliver a higher percentage of care assessed as good practice.

By comparison, over a comparable period in 2007, the DMS treated 314 major trauma cases in Iraq and Afghanistan, an average of 4.25 per week (51.0 over 12 weeks) [4]. Since that time, the frequency of major trauma in Afghanistan has substantially increased.

MVCs were responsible for 56.3 per cent of NHS major trauma patients. Blast or gunshots are not coded and are included in 10.3 per cent of ‘other’ mechanisms; in the matched DMS cohort, only 5.1 per cent of major trauma was from MVC, with 53.8 per cent from blast/fragmentation and 29.9 per cent from gunshot. Banding the ISS results demonstrated that the DMS cohort was significantly (χ2; p < 0.0001) more severely injured than the NHS cohort (ISS 16–24, NHS = 56.5%, DMS = 26.4%; ISS 25–35, NHS = 35.1%, DMS = 22.3%; ISS 36–75, NHS = 8.4%, DMS = 51.3%). However, the injury severity must be interpreted with caution as AIS 05 (military coding standard) has been adjusted from AIS 98 (UK civilian coding standard) to take account of injuries inflicted by military mechanisms and the expected outcomes in an austere military environment.

One advantage enjoyed by the DMS is the multidisciplinary ‘ownership’ of the trauma system, with all care providers feeling a deep responsibility towards the military casualties and the performance of the trauma system. In the deployed field hospital, there is a full consultant-based team [67] (consultants from each of the specialties of emergency medicine (team leader), anaesthesia, general surgery and orthopaedic surgery) resident in the hospital 24 h a day and immediately available for the reception of any seriously injured patient. In the NHS, the trauma patient is rarely received by a senior doctor: 118/183 (64.5%) hospitals did not have a consultant trauma team leader during a specific sample period (early hours of Sunday morning) and in only 6/183 (3.3%) hospitals was the consultant team leader resident. This contributes to incorrect clinical decision making and lack of appreciation of the severity of injury. In two other reports, the National Patient Safety Agency and NCEPOD expressed concern that trainees are less able than consultants to recognize seriously ill or deteriorating emergency patients and that this may have a detrimental effect on outcomes [68,69].

5. Unexpected outcomes

The trauma scoring methods described in §1 are relatively simple mathematical models to quantify the complex human response to injury. While useful when comparing trauma system performance over large groups of patients, when considering individual patients such models are imperfectly predictive [70] and need to be considered in the light of information regarding both the clinical and tactical situations.

The anatomical (AIS, ISS, NISS) and physiological (RTS) methods do not take account of each other. Young, fit casualties have compensatory physiological mechanisms that allow them to maintain near normal vital signs, despite severe anatomical injuries, until just prior to precipitous deterioration. This is of particular relevance to the study of military trauma. In contrast, many elderly trauma victims will have markedly disordered physiology prior to their injuries and may be taking medications that affect the body's response to trauma. For example, beta-blockers will reduce or prevent the tachycardia normally seen in response to blood loss.

The combined scoring systems give a percentage Ps (TRISS) or probability of death (ASCOT). The exact value in any single case should not be accorded overdue emphasis: a casualty found to have a Ps of 60 per cent would be expected to die four times out of 10 and neither method is able to identify why either outcome occurs.

However, the true value of these figures is their use as ‘flags’ to identify an unexpected outcome. Even with regular mortality and morbidity meetings, not every patient's case can or needs to be discussed in detail. Focusing on the unexpected outcomes offers an efficient mechanism for determining which cases offer the most potential lessons for the trauma system. An unexpected death is examined for system failures and areas where practice can be improved. Unexpected survivors help highlight points of excellent clinical practice that can be reinforced and extended across all patients' care.

For both TRISS and ASCOT, the dividing line between expected and unexpected outcomes is taken at 50 per cent. This convention was established in the initial methodology of both, but there is no clear evidence as to why this mark was chosen. Indeed, Kelly et al. [71] have argued that a better mark would be Ps 0.33 (ASCOT Pd 0.66). Table 4 shows the criterion to identify mathematical unexpected survivors for each of the scoring systems used to analyse UK JTTR.

Table 4.

Classification of group A: mathematical unexpected survivors.

| trauma scoring model (related reference given in brackets) | measure of unexpected outcome | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ISS [5] | 60–75 (near maximal or maximal injury) |

| 2 | NISS [6] | 60–75 (near maximal or maximal injury) |

| 3 | TRISS (probability of survival, Ps) [8] | less than 50% |

| 4 | ASCOT (probability of death, Pd) [9] | greater than or equal to 50% |

| 5 | traumatic cardiac arrest [12] | documented CPR |

The somewhat arbitrary nature of all of these criteria emphasizes the need for clinical review and validation alongside the current mathematical models when assessing trauma system performance. In order to further demonstrate this, a study was conducted to (i) identify the unexpected survivors from major trauma treated within the UK military trauma system in Afghanistan and Iraq, and (ii) assess the utility of mathematical models for this population.

(a). Methods

Cases were identified from UK JTTR. All cases between 02 April 2006 and 30 July 2008 were included (UK military, coalition military, civilian contractors, hostile forces, local civilians) from operations in Afghanistan (Operation HERRICK) and Iraq (Operation TELIC).

(i). Mathematical unexpected survivors

The Abbreviated Injury Scale 2005 (Military) (AIS 05 Mil; [10]) was used to codify injuries and their severity within ISS and NISS.

All cases identified by mathematical modelling as ‘mathematical unexpected survivors’ (group A) were subject to independent peer review by two consultants in emergency medicine (T.J.H. and R.J.R.) and one consultant in anaesthesia/critical care (P.M.).

The panel members determined individually and then collectively whether each casualty had been correctly identified as an unexpected survivor. These were allocated to either group B (mathematically unexpected survivor, clinically unexpected survivor) or group C (mathematically unexpected survivor, clinically expected survivor).

If consensus was not reached, the decision was recorded as the majority verdict. For each case, the mechanism of injury (MOI), primary injury sustained (injury with highest AIS 05 (Mil) score) and the life-saving medical interventions performed were recorded.

(ii). Clinical unexpected survivors

All survivors of major trauma (ISS and/or NISS 16–59) in the corresponding period were subject to the same peer review process. This identified cases where the mathematical prediction was expected survival, but the clinical opinion was that survival was unexpected.

The panel members recorded a judgement as to whether each case was an ‘unexpected survivor in the civilian health system but expected in the military system’ (group D) or ‘unexpected survivor in both the military and civilian health systems’ (group E).

The question each panel member addressed in making this judgement was ‘If this casualty arrived at your field hospital or NHS hospital would you expect them to survive?’ The decision was recorded as the majority verdict and the MOI, primary injury sustained and life-saving medical interventions performed were recorded.

(b). Results

The JTTR database contained a total of 1474 trauma cases in the period 02 April 2006 to 30 July 2008. A demographic breakdown is shown in table 5.

Table 5.

Demographics of total number of trauma cases from JTTR (02 Apr 2006–30 Jul 2008; n = 1474).

| Op TELIC | Op HERRICK | other | |

|---|---|---|---|

| military | |||

| UK | 275 | 421 | 7a |

| coalition | 41 | 274 | |

| civilian | |||

| UK contractors | 13 | 2 | |

| coalition | 28 | 116 | |

| hostile | 0 | 21 | |

| local | 40 | 236 | |

| total number of cases | 397 | 1070 | 7 |

aIndicates 2× cases on exercise, 4× cases from permanent joint operating base (PJOB) and 1× other.

(i). Group A: mathematical unexpected survivors

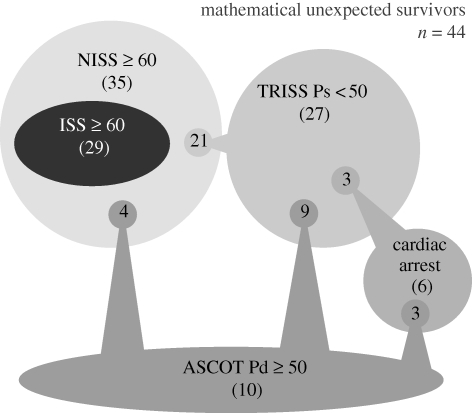

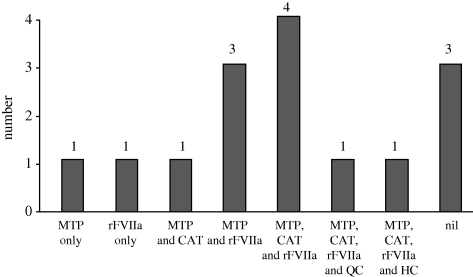

There were a total of 44 mathematical unexpected survivors. This number was derived from the five different models listed in table 4. Some patients were predicted as unexpected survivors by more than one model, but each patient was only counted once in the total. A breakdown of the mathematical unexpected survivors is shown in table 6 and figure 5.

Table 6.

Group A: mathematical unexpected survivors (n = 44).

| trauma model | no. of cases |

|---|---|

| ISS 05 (Mil) ≥60 and survived | 29a |

| NISS 05 (Mil) ≥60 and survivedb | 35 |

| TRISS <50 and survived | 27 |

| ASCOT ≥50 and survived | 10 |

| number of cases who were reported to have had a traumatic cardiac arrest and survived | 6 |

aExcluded 1× case having already received surgery from a coalition medical facility prior to their transfer into the UK military trauma system.

bIncorporates all 29 cases in this table calculated using ISS 05 (Mil).

Figure 5.

Relationships of group A mathematical unexpected survivors within the models listed in table 1. For example, 21/27 of the patients recognized by TRISS were also recognized by NISS.

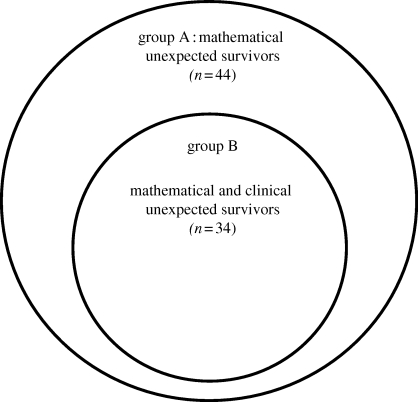

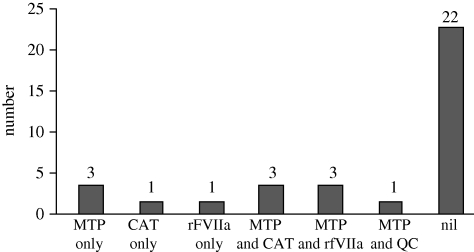

(ii). Group B: mathematical and clinical unexpected survivors

The peer review of Group A validated 34/44 to be ‘clinical unexpected survivors’: this is group B. Details of group B (demographics, injuries and interventions) are given in figure 6 and tables 7 and 8. Twelve cases within group B had their outcome attributed to the advanced resuscitation strategies used within the military to arrest and treat catastrophic haemorrhage following combat trauma, the use of which is shown in figure 7. Group C comprises the 10 cases that were not validated as clinical unexpected survivors as the clinical view was contrary to the mathematical prediction.

Figure 6.

Relationship of group B to group A.

Table 7.

Demographics of groups B (34/44) and C (10/44).

| UK military | coalition military | coalition civilian | local civilian | total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mathematical and clinical unexpected survivor (group B) | 17 | 3 | 2 | 12 | 34 |

| mathematical unexpected but clinical expected survivor (group C) | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 10 |

Table 8.

Mechanism of injury, primary injury sustained and life-saving interventions received by ‘mathematical and clinical unexpected survivors’ group B (n = 34). IED, improvised explosive device; GSW, gunshot wound; RPG, rocket-propelled grenade; MVC, motor vehicle collision; UXO, unexploded ordinance.

| mechanism of injury | number | primary injury sustained (body region) | number | life-saving interventiona | number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IED | 5 | lower extremities (3) | catastrophic bleeding (haemostatics) | ||

| mine | 4 | traumatic amputation–unilateral | 2 | Combat Application Tourniquet (CAT) | 4 |

| GSW | 11 | lower limb fracture | 1 | QuikClot | 1 |

| RPG | 3 | thorax (2) | airway | ||

| mortar | 3 | heart laceration perforation | 1 | pre-hospital rapid sequence induction (PH RSI) | 8 |

| MVC | 1 | avulsion chest wall | 1 | emergency department (ED RSI) | 16 |

| bomb | 3 | head (23) | intubation (no drugs) | 3 | |

| assault | 1 | blunt (4) | surgical airway | 2 | |

| grenade | 1 | base (basilar) of skull fracture | 2 | breathing | |

| UXO | 1 | cerebrum haematoma | 1 | intercostal drainage | 4 |

| unknown | 1 | vault fracture | 1 | Asherman chest seal | 1 |

| penetrating (19) | thoracostomy | 1 | |||

| vault fracture, complex, open | 7 | thoracotomy | 2 | ||

| penetrating injury to skull >2 cm | 6 | circulation | |||

| cerebrum haematoma | 3 | massive transfusion protocol | 10 | ||

| cerebrum contusion | 1 | recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa) | 4 | ||

| brain stem injury with haemorrhage | 1 | intraosseous access | 6 | ||

| base (basilar) of skull fracture | 1 | pericardiocentesis | 1 | ||

| external (1) | |||||

| burns–partial/full thickness 40–89% | 1 | ||||

| abdomen (4) | |||||

| jejunum–ileum laceration | 2 | ||||

| kidney laceration | 1 | ||||

| liver laceration | 1 | ||||

| spine (1) | |||||

| cord contusion | 1 | ||||

| total | 34 | total | 34 | ||

aTotal number of lifesaving interventions does not equal number of cases as some individuals received more than one.

Figure 7.

Members of group B ‘mathematical and clinical unexpected survivors’ (n = 12/34)—cases receiving advanced haemostatic resuscitation interventions. MTP, massive transfusion protocol; CAT, Combat Application Tourniquet; rFVIIa, recombinant factor VIIa; QC, Quikclot.

Clinical unexpected survivors: excluding group A (44/296) mathematical unexpected survivors, a further 252/296 survivors of ‘major trauma’ with an ISS and/or NISS 16–59 were identified from the JTTR within the same period.

Peer review then identified a group of 41/252 clinical unexpected survivors that the mathematical models had missed.

Group D: 26/41 were characterized as ‘civilian system unexpected and military system expected survivors’.

Group E: 15/41 were characterized as ‘civilian and military systems unexpected survivors’.

Five of 252 were categorized as ‘undecided’: insufficient data was available for two cases and the rapid onward transfer of three cases to a local facility resulted in an unknown long-term outcome.

(iii). Group D: civilian system unexpected and military system expected survivors

A demographic breakdown of ‘civilian system unexpected and military system expected survivors’ (n = 26) is shown in table 9. Their MOI, primary injury sustained and life-saving interventions received are shown in table 10.

Table 9.

Demographic breakdown of group D (n = 26).

| UK military | coalition military | coalition civilian | local civilian | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Op TELIC | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Op HERRICK | 7 | 6 | 2 | 3 |

Table 10.

Mechanism of injury, primary injury sustained and lifesaving interventions received by group D (n = 26).

| mechanism of injury | number | primary injury sustained (body region) | number | life-saving interventiona | number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IED | 8 | lower extremities (15) | catastrophic bleeding (haemostatics) | ||

| mine | 6 | traumatic amputation—unilateral | 8 | CAT | 17 |

| GSW | 5 | traumatic amputation—bilateral | 3 | HemCon | 2 |

| RPG | 3 | arterial lacerations | 1 | QuikClot | 2 |

| mortar | 2 | >20% volume loss | 1 | airway | |

| rocket | 1 | lower limb fracture | 2 | PH RSI | 1 |

| MVC | 1 | upper extremities (1) | ED RSI | 10 | |

| upper limb fracture | 1 | intubation (no drugs) | 1 | ||

| thorax (9) | breathing | ||||

| haemopneumothorax | 6 | intercostal drainage | 3 | ||

| tension pneumothorax | 1 | Asherman chest seal | 2 | ||

| blast lung | 1 | circulation | |||

| transected oesophagus | 1 | massive transfusion protocol | 23 | ||

| spine (1) | rFVIIa | 7 | |||

| cord laceration | 1 | intraosseous access | 3 | ||

| total | 26 | total | 26 | ||

aTotal number of life-saving interventions does not equal number of cases as some individuals received more than one.

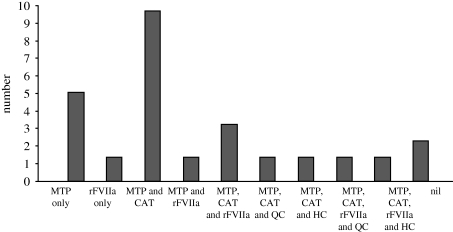

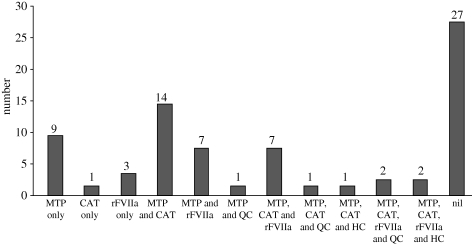

Twenty-four of 26 cases (92%) had their outcome attributed to the advanced resuscitation strategies used within the UK military to arrest and treat catastrophic haemorrhage following combat trauma. A breakdown is shown in figure 8.

Figure 8.

Number of group D: (n = 24/26) cases receiving advanced haemostatic resuscitation interventions. HC, HemCon.

(iv). Group E: civilian and military system unexpected survivors

The demographics of the ‘civilian and military systems unexpected survivors’ (n = 15) is shown in table 11. Their MOI, primary injury sustained and life-saving interventions received are shown in table 12.

Table 11.

Demographics of ‘unexpected survivors for both current civilian and military systems’ (n = 15).

| UK military | coalition military | local civilian | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Op TELIC | 1 | – | 2 |

| Op HERRICK | 6 | 3 | 3 |

Table 12.

Mechanism of injury, primary injury sustained and lifesaving interventions received by group E (n = 15).

| mechanism of injury | number | primary injury sustained (body region) | number | life-saving interventiona | number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IED | 2 | lower extremities (10) | catastrophic bleeding (haemostatics) | ||

| mine | 3 | traumatic amputations—unilateral | 3 | CAT | 7 |

| GSW | 1 | traumatic amputations—bilateral | 3 | HemCon | 1 |

| RPG | 2 | arterial lacerations | 1 | QuikClot | 1 |

| mortar | 1 | >20% volume loss | 1 | airway | |

| MVC | 2 | fractured pelvic ring | 2 | ED RSI | 9 |

| bomb | 3 | thorax (1) | breathing | ||

| aircraft incident | 1 | blast lung | 1 | intercostal drainage | 1 |

| head (1) | circulation | ||||

| cerebrum haematoma | 1 | massive transfusion protocol | 11 | ||

| external (1) | rFVIIa | 10 | |||

| burns—partial/full thickness 40–89% | 1 | intraosseous access | 4 | ||

| abdomen (2) | |||||

| superior mesenteric artery laceration | 1 | ||||

| retroperitoneum haematoma | 1 | ||||

| total | 15 | total | 15 | ||

aTotal number of life-saving interventions does not equal number of cases as some individuals received more than one.

Twelve of 15 cases (80%) had their outcome attributed to the advanced resuscitation strategies used within the UK military to arrest and treat catastrophic haemorrhage following combat trauma. A breakdown is shown in figure 9.

Figure 9.

Number of group E (n = 12/15) cases receiving advanced haemostatic resuscitation interventions.

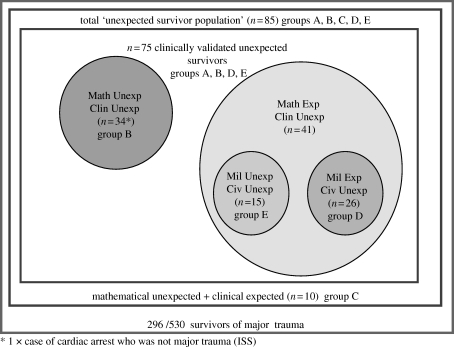

Total clinical unexpected survivors (groups B + D + E): 75 clinical unexpected survivors were identified by combining all categories used to characterize this cohort. The numbers and relationships of each category are shown in figure 10.

Figure 10.

‘Clinical unexpected survivors’ identified from ISS and/or NISS 16–59 group and/or traumatic cardiac arrest.

A demographic breakdown of all ‘validated clinical unexpected survivors’ identified from ISS and or NISS ≥ 16 group or cardiac arrest is shown in table 13.

Table 13.

Demographics of the 75 ‘validated clinical survivors’.

| UK military | coalition military | coalition civilian | local civilian | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Op TELIC | 7 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Op HERRICK | 26 | 12 | 4 | 16 |

The MOI, primary injury sustained and life-saving interventions received by the 75 combined validated clinical unexpected survivors are shown in table 14.

Table 14.

Mechanism of injury, primary injury sustained and lifesaving interventions received by ‘validated clinical unexpected survivors’ (n = 75).

| mechanism of injury | number | primary injury sustained (body region) | number | life-saving interventiona | number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSW | 17 | lower extremities (28) | catastrophic bleeding (haemostatics) | ||

| IED | 15 | traumatic amputation—unilateral | 13 | CAT | 28 |

| mine | 13 | traumatic amputation—bilateral | 6 | HemCon | 3 |

| RPG | 8 | arterial laceration | 2 | QuikClot | 4 |

| mortar | 6 | >20% volume loss | 2 | airway | |

| MVC | 4 | fractured pelvic ring | 2 | PH RSI | 9 |

| bomb | 6 | fractured lower limb | 3 | ED RSI | 35 |

| aircraft | 1 | upper extremities (1) | intubation without drugs | 4 | |

| rocket | 1 | fractured upper limb | 1 | surgical airway | 2 |

| assault | 1 | thorax (12) | breathing | ||

| grenade | 1 | haemopneumothorax | 6 | intercostal drainage | 8 |

| UXO | 1 | tension pneumothorax | 1 | Asherman chest seal | 3 |

| unknown | 1 | blast lung | 2 | thoracostomy | 1 |

| heart laceration perforation | 1 | thoracotomy | 1 | ||

| avulsion of chest wall | 1 | circulation | |||

| transected oesophagus | 1 | massive transfusion protocol | 44 | ||

| external (2) | rFVIIa | 21 | |||

| burns partial/full thickness 40–89% | 2 | intraosseous access | 13 | ||

| abdomen (6) | pericardiocentesis | 1 | |||

| superior mesenteric artery laceration | 1 | ||||

| retroperitoneum haematoma | 1 | ||||

| jejunum–ileum laceration | 2 | ||||

| kidney laceration | 1 | ||||

| liver laceration | 1 | ||||

| spine (2) | |||||

| cord laceration | 1 | ||||

| cord contusion | 1 | ||||

| head (24) | |||||

| blunt (4) | |||||

| base (basilar) fracture | 2 | ||||

| cerebrum haematoma | 1 | ||||

| vault fracture | 1 | ||||

| penetrating (20) | |||||

| vault fracture complex open | 7 | ||||

| penetrating injury to skull >2 cm | 6 | ||||

| cerebrum haematoma | 4 | ||||

| cerebrum contusion | 1 | ||||

| brain stem injury with haemorrhage | 1 | ||||

| base (basilar) fracture | 1 | ||||

| total | 75 | total | 75 | ||

aTotal number of life-saving interventions does not equal number of cases as some individuals received more than one.

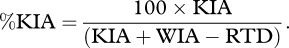

Forty-eight of seventy-five cases (64%) had their outcome attributed to the advanced resuscitation strategies used within the UK military to arrest and treat catastrophic haemorrhage following combat trauma. A breakdown is shown in figure 11.

Figure 11.

Number of validated unexpected survivors identified from ISS and/or NISS ≥16 group or cardiac arrest, 48/75 cases having received advanced haemostatic resuscitation interventions.

Of the 75 validated clinical unexpected survivors, gunshot wound (GSW) (23%) was the leading cause of major trauma, followed by improvised explosive device (IED) (20%) and mine (17%). Head injury was the most common primary injury (32%), followed by traumatic amputation (25%). A tourniquet (Combat Application Tourniquet) was used in 37 per cent, massive transfusion in 59 per cent and recombinant factor VIIa in 28 per cent cases. Emergency airway interventions were performed in 67 per cent of cases.

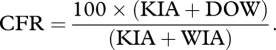

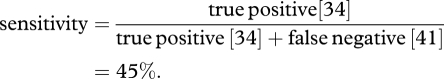

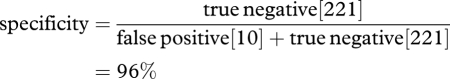

Sensitivity and specificity of mathematical models: sensitivity and specificity of the mathematical models were calculated using the classifications shown in table 15.

Table 15.

Classification of true positive/negative and false positive/negative.

| true positive | false positive |

|---|---|

| clinical and mathematical unexpected survivor (n = 34) | mathematical unexpected and clinical expected survivor (n = 10) |

| false negative | true negative |

| mathematical expected and clinical unexpected survivor (n = 41) | clinical and mathematical expected survivor (n = 221) |

The combined sensitivity of the mathematical models (the ability to identify unexpected survivors) was calculated as follows:

|

The combined specificity of the mathematical models (the ability to identify expected survivors) was calculated as follows:

|

Case examples: case examples of validated clinical unexpected survivors are given in boxes 1 and 2.

Box 1. Validated clinical unexpected survivor—case 1.

demographics

age: 24 sex: male type: IED

injuries:

left through-knee traumatic amputation

right above-knee traumatic amputation

left incomplete below-elbow traumatic amputation

testes laceration and avulsion

pre-hospital

medical response team: radial pulse and alert then

radial pulse and responded to voice then

femoral pulse and unresponsive

interventions: 2× Combat Application Tourniquets (CAT) applied to both legs

1× CAT applied to L arm

rapid sequence induction performed

CPR performed (adrenaline given)

650 ml crystalloid given

hospital

emergency department: 4 units of packed red cells

2 units of fresh frozen plasma (FFP)

CPR 10 min (pulseless electrical activity and ventricular fibrillation) prior to return of spontaneous circulation

theatre: 24 units of blood

27 units of FFP

4 units platelets

2 cryoprecipitate

operations: right above-knee amputation

left through-knee amputation

left below-elbow amputation

right orchidectomy

debridement of scrotum and perineal wound

debridement of facial wounds

Box 2. Validated clinical unexpected survivor—case 2.

demographics

age: 22 sex: male type: RPG

injuries: 70% burns (50% full thickness, 20% partial thickness)

fracture of right femur

pre-hospital

medical response team: Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) 3/15

systolic blood pressure (SBP) 70 mmHg

pulse rate 120 min−1

respiratory rate 8 min−1

interventions: rapid sequence induction of anaesthesia

1000 ml crystalloid (femoral vein cut down)

hospital

emergency department: 19 units packed red cells

11 units FFP

6 l of crystalloid

intraosseous access

CPR performed

operations: escharotomies: bilateral arms and digits, neck and right thigh

external fixation of R femur

scrub-down of torso and facial burns

(c). Survival after traumatic cardiac arrest

Civilian published experience is that survival to hospital discharge after traumatic cardiac arrest is extremely poor [72–79], with rates of between 0 and 7.5 per cent. Even in the higher performing trauma systems, survival from hypovolaemic arrest following trauma remains extremely poor [76].

Contemporary experience suggested that military casualties are surviving traumatic cardiac arrest in greater numbers than expected, including hypovolaemic arrest. A search of JTTR between 01 August 2008 and 30 November 2009 revealed 78 casualties who received CPR of which 18 survived. This is a 24 per cent survival rate.

This group represents the incremental and step-change systemic advances in processes, equipment and clinical guidelines that are pushing the boundaries of current trauma practice. It also represents all components of the trauma system functioning above expectation, from immediate life-saving first aid, through primary retrieval (by a physician-led advanced resuscitation team) to immediate surgical and transfusion resuscitation on arrival at the field hospital.

The mechanisms of injury in this group were predominantly blast IEDs and gunshot.

The greatest percentage of fatalities occurred at scene (39%) and these were noted to have sustained unsalvageable injuries. However, a significant percentage of CPR commenced at scene resulted in survival to discharge from the role 3 field hospital (33%). Equally, CPR commenced during primary retrieval (physician-led helicopter team) resulted in a 21 per cent success rate. This suggests that the advanced care provided during evacuation is highly successful compared with civilian norms.

(d). Discussion

These results underscore the dangers of over-reliance on mathematical models of survival in trauma, especially when applied to an individual patient. Some patients identified as mathematically unexpected survivors were reclassified after clinical review; other casualties that clinicians judged to be exceptional ‘saves’ were not identified by mathematical modelling. Trauma scoring tools are a useful method of assessing the efficacy of a trauma service and help highlight individual cases for scrutiny. However, clinical peer review is an essential complementary element.

Trauma cases were analysed from April 2006 as this coincides with the start of UK combat operations in Southern Afghanistan. This particular period was also chosen for study as it coincided approximately with the introduction of new military medical technologies and systems (box 3).

Box 3. New military medical technologies.

— Change of treatment paradigm from ABC to <C > ABC [80] to reflect the importance of rapidly controlling external catastrophic bleeding.

- — Equipment to control external bleeding:

- an elastic field dressing (individual issue from 2005),

- the Combat Application Tourniquet (CAT) [62] (individual issue from April 2006),

- QuikClot (introduced 2005),

- HemCon (introduced April 2006), and

- Celox Gauze (introduced 2010).

— Recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa) [81] (introduced 2003; used as part of massive transfusion protocol from 2007).

— Intraosseous access (EZ-IO; FAST-1) [82] which has aided rapid circulatory access when intravenous access is difficult.

The philosophy behind these advances has been to project far forward to POW skills and equipment that can be used to save life, focused on (but not confined to) arresting external bleeding. This has underpinned advances in individual first aid and the Army Team Medic programme (one in four combat soldiers with additional equipment and training) [67,83].

In parallel to the introduction of this series of new interventions has been the pre-hospital projection of skilled medical expertise forward to the POW. The concept of a MERT to include a specialist doctor was used successfully by UK military in the Balkans conflict, but was further developed during Op HERRICK 4 (2006) in response to a substantial increase in operational tempo. MERT capability includes in-flight rapid sequence induction of anaesthesia, venous access techniques, open and tube thoracostomy, surgical airway and the administration of blood products (red cells and plasma) [84].

The tables and graphs set out within each patient subgroup illustrate where these interventions may have had an effect. The evaluation of clinical effectiveness from August 2008 is the subject of ongoing research.

In contrast to NHS hospitals [9], deployed military field hospitals have consultant-based acute trauma care. Trauma teams live adjacent to the hospital and are immediately available for the reception of any seriously injured patient. Assessment and critical decision making are rapid especially with regard to crucial blood transfusions [85–87], and there is opportunity to move directly into the adjacent operating theatre for consultant-delivered surgical resuscitation. Continuing with this level of care, the rapid strategic movement of the seriously injured from the field hospital to RCDM uses a consultant in intensive care as part of a dedicated Critical Care Air Support Team (CCAST) [4].

6. Future developments: can trauma scoring models improve?

Trauma as a ‘disease’ is multi-faceted—as is the response to injury, both in terms of the casualty's physiological response and the organizational response of the emergency services. Patient outcome will be influenced by decisions and procedures at multiple stages during the care pathway.

The military trauma system faces challenges and complexities that civilian systems do not: a long evacuation chain with acute physical threats to the rescuers, and a long and fragile logistical re-supply chain. Additionally, while coalition combat casualties are usually young and have low co-morbidity, civilian casualties of conflict span all ages and have a very different scope of co-morbidity to civilian casualties in the UK.

The current trauma scoring methods were developed prior to the emergence of Complexity as a field of study in the late 1990s. As a result, they rely on linear statistical methods, which have not proved to be effective analytical tools for complex systems.

A complex system is a network of heterogeneous components that interact non-linearly, to give rise to emergent behaviour [88]. Emergent behaviour appears when a number of simple agents operate to form more complex behaviours as a collective. Complex systems are highly structured, but show variations [89] because there are a large number of independent, interacting components and multiple pathways that the system can follow [90,91]. There is a process of constant evolution and learning that can be very sensitive both to initial conditions and to small disturbances [92]. Complex systems are nonlinear in that behaviour cannot be expressed as a sum or multiple of the parts.

Trauma as a disease coupled with a treatment process is a complex system. Therefore, using a nonlinear statistical approach may give a better mathematical model for use in analysing system performance.

The ideal trauma scoring methodology needs to take account of the following factors:

— Age. TRISS only divides casualties into those younger or older than 55. ASCOT has further age bands for every 10 years above 55, but neither system has been validated for children.

— Pre-injury health. Two individuals of the same age may have vastly different physiological reserves as a result of pre-existing disease. Some eighty-year-olds remain very active; others are all but chair-bound. Older people are becoming an increasingly large proportion of the population and are maintaining behaviours that put them at risk of trauma (e.g. driving) for longer.

— Blast. The current scoring models distinguish between penetrating and blunt trauma. With greater experience both on contemporary military operations and in terrorist incidents, it is becoming apparent that blast injury, while sharing features in common with both blunt and penetrating injury, has characteristics that establish it as a separate mechanism in its own right.

— Pre-hospital physiological data. The existing scoring models were created at a time when pre-hospital care was undeveloped and as a result few physiological readings were available from the scene of an incident, and few interventions were undertaken that could significantly alter outcome. As pre-hospital care has become more sophisticated, it is appropriate to take into account the physiology at scene before any intervention and to specifically evaluate the impact of pre-hospital interventions.

— Quality of outcome. Outcome measures are generally expressed crudely as death or survival. While unequivocal, this does not reflect the quality of care received. A patient with critical injuries given poor treatment will die; given moderate treatment be permanently disabled; and receiving good treatment may attain independent living. Excellent treatment may return them to full functional recovery. Linking trauma registries to long-term outcome measures will identify otherwise unknown implications of specific approaches to the early management of severe trauma.

Nonlinear analysis has been used to produce process models in the life sciences and energy research, as well as other fields. Two potential approaches to a nonlinear trauma model are Bayesian and artificial neural networks. These are currently under assessment as a UK military research initiative.

(a). Bayesian networks

In probability theory, Bayes' theorem demonstrates the relationship between a conditional probability and its inverse. It expresses the posterior probability after evidence (E) is observed of a hypothesis (H) in terms of the known prior probabilities of H and E, and the probability of E given H. This implies that evidence has a stronger confirming effect if it were more unlikely before being observed.

For example, the probability of A (having a disease) given B (having a positive test) depends not only on the relationship between A and B (the accuracy of the test), but also on the probability of A not concerning B (the incidence of the disease in general), and the probability of B not concerning A (the probability of a positive test). If the test is known to be 95 per cent accurate, this could be due to 5 per cent false positives, 5 per cent false negatives or a mix of both. Bayes' theorem allows the calculation of the exact probability of having the disease given a positive test for any of these three cases. If the probability of the disease is around 1 and 5 per cent of tests produce a positive result, then the probability that an individual with a positive result actually has the illness is small since the probability of a positive result is five times more likely than the probability of the disease itself.

A Bayesian network uses conditional probability to predict the outcome of an event and allows the introduction of prior knowledge to influence the outcome of the analysis.

(b). Artificial neural networks

A neural network is a mathematical or computational model that tries to simulate the structure and/or functional aspects of biological neural networks. In a neural network model, simple nodes or processing elements are connected together to form the network with algorithms designed to alter the weight given to each node or connection to produce a desired signal flow. Neural networks are most often used to model complex relationships between inputs and outputs or to find patterns in data. They can also be used for solving problems for which no rules are known as they can adapt and change structure based on the information they receive.

Pre-existing data held on casualties in JTTR will be randomly split into training and validation cases. After the selection of the network algorithms and training parameters, the network will use the training set to teach itself by calculating the difference between its results and the known ones. This error is then reduced by changing the weights of input/output nodes and connections as the network continually learns from new information. The predictive accuracy of the network can then be tested against the validation set of data.

(c). Conclusion

The military trauma system and its CG have been informed and developed by the use of trauma scoring to the point where care in the field hospital is in advance of that available in an NHS hospital. Future developments in trauma scoring will continue to enhance performance.

Acknowledgements

All work was carried out at the Academic Department of Military Emergency Medicine.

Footnotes

One contribution of 20 to a Theme Issue ‘Military medicine in the 21st century: pushing the boundaries of combat casualty care’.

References

- 1.SGPL 09/00 2000. Clinical governance in the Defence Medical Services. London, UK: Ministry of Defence [Google Scholar]

- 2.SGPL 01/03 2003. Clinical governance in the Defence Medical Services. London, UK: Ministry of Defence [Google Scholar]

- 3.SGPL 18/04 2004. Quality assurance of clinical governance on deployed operations. London, UK: Ministry of Defence [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodgetts T. J., Davies S., Russell R. J., McLeod J. 2007. Benchmarking the UK military deployed trauma system. J. R. Army Med. Corps 153, 237–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith J., Hodgetts T. J., Mahoney P. F., Russell R. J., Davies S., McLeod J. 2007. Trauma governance in the UK Defence Medical Services. J. R. Army Med. Corps 153, 239–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Healthcare Commission. Defence Medical Services: a review of the clinical governance of the Defence Medical Services in the UK and overseas. London, UK: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Royal College of Surgeons of England. Report of the working party on the management of patients with major injury. London, UK: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Royal College of Surgeons of England and the British Orthopaedic Association. Better care for the severely injured. London, UK: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith N., Weyman D., Findlay G., Martin I., Carter S., Utley M., Treasure T. 2009. The management of trauma victims in England and Wales: a study by the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 36, 340–343 (doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.03.048) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine. Abbreviated Injury Scale 2005. Barrington, IL: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kilgo P. D., Osler T. M., Meredith W. 2004. The worst injury predicts mortality outcome the best: rethinking the role of multiple injuries in trauma outcome scoring. J. Trauma 55, 599–606 (doi:10.1097/01.TA.0000085721.47738.BD) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikhail J. N., Harris Y. D., Sorensen V. J. 2003. Injury severity scoring; influence of trauma surgeon involvement on accuracy. J. Trauma Nurs. 10, 43–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker S. P., O'Neill B., Haddon W., Long W. 1974. The injury severity score: a method of describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J. Traum 14, 187–1966 (doi:10.1097/00005373-197403000-00001) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker S. P., O'Neill B. 1976. The injury severity score: an update. J. Trauma 16, 882–885 (doi:10.1097/00005373-197611000-00006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell R. J., Halcomb E., Caldwell E., Sugrue M. 2004. Mortality prediction between injury severity score triplets—a significant flaw. J. Trauma 56, 1321–1324 (doi:10.1097/01.TA.0000062763.21379.D9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baue A. E. 2008. What's the score? J. Trauma 65, 1174–1179 (doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e318188e89b) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]